Abstract

Mental-content verbs such as think, believe, imagine and hope seem to pose special problems for the young language learner. One possible explanation for these difficulties is that the concepts that these verbs express are hard to grasp and therefore their acquisition must await relevant conceptual development. According to a different, perhaps complementary, proposal, a major contributor to the difficulty of these items lies with the informational requirements for identifying them from the contexts in which they appear. The experiments reported here explore the implications of these proposals by investigating the contribution of observational and linguistic cues to the acquisition of mental predicate vocabulary. We first demonstrate that particular observed situations can be helpful in prompting reference to mental contents, specifically, contexts that include a salient and/or unusual mental state such as a false belief. We then compare the potency of such observational support to the reliability of alternate or concomitant syntactic information (e.g., sentential complementation) in tasks where both children and adults are asked to hypothesize the meaning of novel verbs. The findings support the efficacy of false belief situations for increasing the saliency of mental state descriptions, but also show that syntactic information is a more reliable indicator of mentalistic interpretations than even the most cooperative contextual cues. Moreover, when syntactic and observational information sources converge, both children and simulated adult learners are vastly more likely to build conjectures involving mental verbs. This is consistent with a multiple-cue constraint satisfaction view of vocabulary acquisition. Taken together, our findings support the position that the informational demands of mapping, rather than age-related cognitive deficiency, can bear much of the explanatory burden for the learning problems posed by abstract words.

Keywords: theory of mind, mental verbs, verb learning, syntactic bootstrapping, language acquisition

-- many of our complex ideas never had impressions that corresponded to them, and ...many of our complex impressions never are exactly copied in ideas.

David Hume (1739-40, 1.1.1. p. 3)

1. Introduction

Among the more awesome feats of learning in the human repertoire is the acquisition of the vocabulary of a first language. Analysis from Carey (1982) informs us that the average rate of word acquisition is something like 8 to 10 words a day though there are some hills and valleys along the way (P. Bloom, 2002). Furthermore, the consensus across individuals as to the interpretation of novel words is quite remarkable given the variability of input conditions, individual and population differences among learners and among languages learned (for reviews, see Gleitman & Newport, 1996; Waxman & Lidz, 2006). In the present article, we examine the acquisition of a particularly interesting class of words, the belief predicates, including such items as think, believe, remember and know. As we will discuss further, these items differ in their semantic-conceptual properties and in their typical learning signatures from most other words in several ways: They don't refer to perceptually transparent properties of the reference world; they are quite insalient as interpretations of the gist of scenes; they appear frequently in maternal speech to babies and yet occur in the child's own speech comparatively late; the concepts that they encode are evidently quite complex or abstract; and they are hard to identify from context even by adults who understand their meanings. It is immediately clear that the several particulars just mentioned are not independent of each other but are causally related in some ways that we will be trying to sharpen in the experimental work that is presented here. Our posit is that some fundamental aspects of the word-learning task can be uncovered by focusing attention on these unusual terms.

1.1 The learning trajectory for mental verbs

Belief verbs are notoriously hard to acquire. Children often produce verbs describing actions or physical motion such as throw or run before the second birthday (L. Bloom, Lightblown & Hood, 1975), and appear to understand them well (Huttenlocher, Smiley & Charney, 1983; Gentner, 1978). Think and know don't usually appear until the end of the third year of life (Bretherton & Beeghly, 1982; Shatz, Wellman & Silber, 1983) and are not well distinguished from one another in comprehension until around age four (Johnson & Maratsos, 1977; Moore, Bryant & Furrow, 1989; Moore & Furrow, 1991; Naigles, 2000).

Part of the explanation for these differences in onset doubtless has to do with characteristics of the input speech to very young children. For example, owing to the greater freedom of nominal ellipsis in, say, Mandarin and Korean as opposed to English, verbs as a class account for a larger percentage of words uttered to children in those languages than they do in English (Tardiff, Shatz, & Naigles, 1997), and are more likely to occur in the perceptually prominent final position (Au, Dapretto, & Song, 1994). Moreover, Mandarin-speaking caretakers utter proportionally fewer abstract verbs to their infant offspring than do middle-class English caretakers (Snedeker & Li, 2000) and the transparency of contextual support accompanying use of such items also differs cross-linguistically (Snedeker, Li & Yuan, 2003). All these factors influence both the overall emergence of verbs as a class in child speech, and the appearance of belief verbs.

However, these input differences are very far from providing the full explanation for the late appearance of belief verbs. Two major approaches, discussed in turn below, have been offered in the recent literature as providing fundamental explanations for these timing effects. The first, the conceptual-growth hypothesis, puts the spotlight squarely on the abstractness of the concepts that the belief terms express. The second, the information-growth hypothesis, does the same but asserts that the influence of abstractness is indirect: According to this second approach, it is not so much the conceptual difficulty of the concepts encoded that makes the trouble for lexical acquisition, but the difficulty for learners in discovering the conditions for these wordsutterance during the flow of events. It is their insalience in the stream of events more than their (punct!) utter unavailability to thought that makes the trouble. 1

1.1.1 The conceptual growth hypothesis

Plausibly, children's difficulties in acquiring the belief verbs are attributable to deficiencies with the underlying mental-state concepts (Bartsch & Wellman, 1995; Gopnik & Meltzoff, 1997; Perner, 1991). There may be a time during infancy (how early is a matter of controversy) when children can neither represent the ideas that these words express nor reason about them. Lacking the concepts, their verbal expressions cannot be acquired. Gopnik and Meltzoff (1997) present this view as follows:

...the emergence of belief words like “know” and “think” during the fourth year of life, after “see,” is well established. In this case...changes in the children's spontaneous extensions of these terms parallel changes in their predictions and explanations. The developing theory of mind is apparent both in semantic change and in conceptual change. (p. 121)

This proposal about mental verbs is consistent with a broader view of word learning, according to which vocabulary development is an index of conceptual development (e.g., Dromi, 1987; Huttenlocher et al., 1983). The changing character of early vocabularies more or less directly reflects the growing typology of concepts in the mind of the learner. As Smiley and Huttenlocher (1995) put this:

...Even a very few uses may enable the child to learn words if a particular concept is accessible. Conversely, even highly frequent and salient words may not be learned if the child is not yet capable of forming the concepts they encode...cases in which effects of input frequency and salience are weak suggest that conceptual development exerts strong enabling or limiting effects, respectively, on which words are acquired (p. 20).

In the specific case of mental terms, the conceptual growth account seems to receive support from a very large body of experimental evidence showing that young children have difficulty with mental state reasoning (or theory of mind, cf. Premack & Woodruff, 1978). They appear to lack knowledge that others may be in a state of false belief and they fail to make inferences based on such an understanding (Wimmer & Perner, 1983; Carruthers & Smith, 1996; but see Leslie, 1994 for evidence against the conceptual deficit account and in support of the view that that the concept of belief is present in preschool children). Because the relevant thoughts are hard to come by early in life, words expressing them are accordingly hard to acquire.

1.1.2 The information growth hypothesis

An alternative, or additional, perspective on how mental verbs make their way into vocabularies has to do with the kind of evidence required for matching linguistic labels with mentalistic meanings (the mapping problem; cf. Locke, 1690). According to this view, the difficulty posed by the mental-content items is not solely or even primarily due to conceptual limitations in the learner; rather, the critical issue concerns the informational conditions inherent in the circumstances of early word learning and the learning tools that novices have at their disposal (Gleitman, 1990).

The idea here is that words that refer to mental states and events lack obvious and stable observational correlates: As a general rule it is easier to observe that jumpers are jumping than that thinkers are thinking. Assuming that word learning – especially in its initial stages -- relies heavily on establishing relations between what is said and what is (observably) happening in the extralinguistic environment, it follows that there will be barriers to acquiring mentalistic terms even where the concepts themselves fall within the learner's repertoire. In essence this is because, even though the relevance conditions for uttering think surely include thinking situations, this thinking takes place invisibly, inside nontransparent heads. These limitations would apply for any novice (even, say, a learned French-speaking professor visiting the USA on sabbatical) as long as he or she is acquiring vocabulary solely by observing how words line up with ambient objects, properties, relations, states, and events. This learning procedure, which we have dubbed word-to-world pairing, has a venerable theoretical history and lies at the heart of associationist approaches to language acquisition (from Hume, 1739-40 to his many descendents in present day cognitive science, e.g. Barsalou, 1999, L. Smith, 2000).

As we will discuss further, the information growth hypothesis is that these barriers are breached by bringing new kinds of evidence to bear on the mapping problem. These additional sources of evidence are primarily linguistic, enabling a new kind of pattern search, structure-to-world pairing (sometimes called “syntactic bootstrapping”).

1.2 A proposal for how mental verbs are acquired

In our view, both the approaches just sketched have something to say about why belief verbs are acquired relatively late. After all, these hypotheses are much alike in assigning the special difficulty of acquiring belief verbs (and, in fact, abstract words in general) to their unobservability and insalience during ordinary conversational exchange.2 But while these approaches share this central insight, they differ in their implications for how these difficulties are to be redressed such that novices eventually acquire these harder lexical items. In the remainder of this introduction we will discuss linguistic and situational factors that plausibly relate to these issues, and experimental procedures by which they can be separately and jointly investigated.

1.2.1. Structural contributions to belief verb learning

A key to acquiring abstract words is the construction of language-internal evidentiary sources during the first few years of life (for a fuller description of such machinery, see Gleitman, 2003; Gleitman, Cassidy, Nappa, Papafragou, & Trueswell, 2005; Trueswell & Gleitman, in press). One such source is a growing database of linguistic co-occurrence information by means of which the learner can narrow the referential domain of new items (for instance, the co-occurrence of eat with edibles and drink with potables; Harris, 1951; Resnick, 1996; and see Altmann & Kamide, 1999 for recent experimental evidence). Even more central in the context of understanding belief verb acquisition is the verb's required and preferred structural environments. We know that a verb's syntactic privileges (namely, argument type, in conjunction with argument number and position) can predict the semantic profile of the verb (Baker, 2002; Croft, 1991; Fillmore, 1968; Goldberg, 1995; Gruber, 1967; Jackendoff, 1990; Levin, 1985; McCawley, 1968; among others). There is by now considerable evidence that such syntactic signatures provide a source of information that systematically cross-classifies the set of verbs within and across languages along lines of broad semantic similarity (Fisher, Gleitman & Gleitman, 1991; and for cross-linguistic evidence, Geyer, 1994; Lederer, Gleitman & Gleitman, 1995; Li, 1994). Furthermore, children are richly sensitive to these regularities in syntax-to-semantics mappings (Brown, 1957; Fisher, Hall, Rakowitz & Gleitman, 1994; Gropen, Pinker, Hollander, Goldberg & Wilson, 1989; Landau & Gleitman, 1985; Lidz, Gleitman, & Gleitman, 2003; Mintz & Gleitman, 2002; Naigles, 1990; Naigles, Gleitman & Gleitman, 1992; Naigles & Kako, 1993; Pinker, 1991; Snedeker, Thorpe & Trueswell, 2001; Waxman, 1994).

One might wonder how novices, especially small children, could break into these systematic correlations between form and meaning. Indeed if the correlations were arbitrary, as some have argued (e.g., Brown, 1957; Goldberg, 2004), they could play only a negligible and late role in learning. But on the contrary this interface is often remarkably straightforward, and the same form-to-meaning pairings manifest themselves again and again in the languages of the world, no matter how disparate they may be in other regards. For instance, thematic roles tend to line up one-to-one with argument positions in syntactic structures (roughly, the “theta criterion,” Chomsky, 1981; see also Fisher, 1996; Fisher et al., 1994; Fisher & Gleitman, 2002; Lidz & Gleitman, 2004) and, in most languages, occupy distinctive structural positions. These features are reproduced, as well, in the self-invented languages of the isolated deaf (Gleitman & Newport, 1996; Goldin-Meadow, 2003; Senghas, Coppola, Newport & Supalla, 1997).

Particularly pertinent in the present context, the lexical and phrasal composition of the arguments of mental verbs is quite transparently related to the logic of mental predicates. Sentential complementation (“He thinks that it's red”) has semantic correlates: it implies a thematic relation between an animate entity and a proposition. This relation holds in every known language of the world and is a crucial feature of language design. Because of this restriction, the class of items licensing sentence complements includes verbs of communication (say, tell, announce; Zwicky, 1971), perception (see, hear, perceive; Gruber, 1965) and mental act or state (believe, think, know; Vendler, 1972). This syntactic behavior, to the extent that children can identify it, is a useful (and principled) cue to a novel verb's meaning. Strikingly, this structure-semantics correlation is implicated in blind as well as sighted children's discovery that look and see are terms of perceptual exploration whereas touch is not.3

Even though available for all kinds of lexical learning, syntactic information should be particularly helpful for the acquisition of mental verbs. This is for two main reasons. The first is the one we have emphasized most so far: To the extent that mental contents are not open to direct inspection (one may smile and smile and be a villain), the burden of learning falls the more heavily on internal linguistic-evidentiary sources. And second, mental verbs often take clausal complements that are semantically restrictive and hence quite informative about the kind of verb that can appear with them. The same two factors, but turned on their heads, apply to concrete action terms: They are more amenable to learning by situational observation, and their syntactic-constructional correlates are weak and undifferentiated within and across the class. They occur primarily in transitive or simple intransitive frames, which are themselves associated with a broad range of verb meanings; consequently, these frames provide little constraint on the kind of verb that can appear in them. For these kinds of verb, extra-linguistic information is the more useful in breaking into their meanings (Snedeker & Gleitman, 2004; Gleitman et al, 2005). Our first experimental prediction follows from these considerations:

(i) The appearance of a novel verb in a sentence complement construction should narrow the search space for its meaning to a set including mental predicates – no matter what else is happening in the observable reference world.

1.2.2 Situational supports for belief verb learning

Acknowledging the usefulness of syntactic cues, the fact is that children do not learn the words think and know by inspecting incoming structures while being locked away from the world of objects and events. Despite the indeterminacy of ordinary cross-situational observation, we must believe that as a practical matter certain extralinguistic circumstances and conversational settings facilitate thinking about thinking itself.

Consider in this regard one of the challenges facing the learner - the task of inferring that an observed discourse situation concerns wanting or thinking. This task is far from trivial: Although children show an early sensitivity to cues about other people's mental states (including eye gaze, gestures, etc.; Bruner, 1974; Baldwin, 1993; Tomasello & Kruger, 1986), it is not clear how they become able to use that ability with the precision necessary to conjecture the meaning of a specific lexical item. After all, while there may well be jumping in view when one hears talk of jumping, there is usually no Rodin statue around when the child hears talk of thinking. Worse, there is generally some physical act occurring in the world or readily implied when one first hears a mental term uttered (for instance the act of cupping one's chin in one's hand), and it is all too easy to infer, falsely, that this action is what the verb expresses. These “inferences to the concrete act” are often the rule in laboratory situations, where even adults are mulishly disinclined to suppose that the mental state of speaker or listener is under discussion. As one example, they reliably guess that a mother is uttering the verb eat when they see a (silenced) videotape of her handing a cookie to her young child. Actually, the mother is much more often alluding to the child's mental state, saying “Do you want a cookie?” (Gillette Gleitman, Gleitman & Lederer, 1999). Evidently to learn that the sound /wônt/ encodes an abstract mental predicate, one must construct a quite global and abstract representation of the discourse gist. Under what circumstances is this likely to happen? When do we think about thinking?

For a mental state to emerge as a candidate for the meaning of a novel word, it must acquire some special conversational relevance. Otherwise, as in the example just given, the fact that there is a mental state (of desire) playing a causal role in the offering and consuming of cookies runs along under the attentional radar as a background supposition, while concentration falls on the actual (or even potential) physical act. In short, eating is “salient.” That it is a desire-to-eat that gets you to eat is taken for granted. The hypothesis that we will be pursuing is the following:

(ii) Mental states rise to special relevance in contexts where an incorrect mental state – a false belief -- is easily inferable, and is at stake in the action observed.

This is likely to happen where a lie, trick or mistake is happening (Little Red Riding Hood thinks that this toothy hairy creature is her grandmother), or where there is uncertainty, contrast or change in the underlying mental contents (“What do you think?”, “I used to think...”). The idea is that, much more than in the ordinary circumstances of true beliefs, circumstances involving false beliefs highlight the salience of the mental state itself. And only once the state of mind comes into focus can it support the relevant inference about the meaning of a novel word then uttered.4

Symmetrically, we predict no or little enhancement of the salience of mental predication during the vastly more common situations in which the speaker reports on a true belief or state of mind (“I think we should pick up the toys now”). These uses have been called conversational and have been broadly recognized to be uninformative for the language learner trying to figure out the meanings of mental verbs (Naigles, 2000; Shatz, Wellman & Silber, 1983; Urmson, 1960). After all, what usually happens after or during such an utterance from caregiver to child is that the former (less likely, the latter too) begins picking up toys. It's the picking-up that relates transparently to the passing scene whereas the information value added by “I think ...” in these true belief contexts is close to zero; if anything it is a politeness marker rather than a report of present mental contents, as Shatz et al. (1983) have pointed out. On the other hand, contrastive (or flatly false) uses of belief terms are potentially more informative. Studies tracing children's spontaneous uses of mental state verbs (Shatz et al., 1983) have treated contrastive uses of mental verbs as the first genuine indication of understanding their meaning (“Before I thought this was a crocodile; now I know it's an alligator”). Our claim here is that such uses highlight the contextual conditions that promote discovery of the meaning of mental verbs. In short, from a learning perspective, we posit that it's not the truth that sets you free. 5

1.3 A procedure for investigating word learning: The Human Simulation Paradigm

We have sketched two hypotheses about the learnability challenges posed by mental-content verbs. We take them as cooperative and complementary rather than competing. Both arise from the observational opacity of these words as they relate to the events, states, and scenes that accompany the linguistic input. So as to understand the machinery that supports lexical learning, it is nevertheless crucial to distinguish the effects of these situational and linguistic factors, and to examine their interactions. The procedure we will adapt in the experiments of Section 2 is a laboratory method known as the Human Simulation Paradigm (henceforth HSP; Gillette et al., 1999; Snedeker & Gleitman, 2004). This method investigates the potency of different kinds of cue (situational and linguistic) for solving the mapping problem for vocabulary growth. In the original HSP studies (Gillette et al., 1999), adults were shown silenced videos (each about ¾ sec in length) of naturally-occurring scenes in which mothers were interacting and speaking with their infants aged between 18 to 24 months of age. These videos were selected to contain instances of the use of words that were highly frequent in maternal speech, as culled from a larger sample of naturalistic mother-infant interactions. At the exact point in the otherwise silenced video where the mother had actually uttered the target word, the participants heard a beep or a nonsense word. Subjects saw six such (randomly selected) videos for each target, and then guessed at its meaning. For example, one of these frequently-used verbs was call. Not surprisingly, in the random selection of six scenes in which a mother was uttering this word to her infant, several of them showed either the mother or the infant herself playing with a toy telephone (and one or two did not, as even talk to babies often diverges from the here and now, or is opaque with respect to the context). Other participants were given linguistic information instead of or in addition to the videotaped situational information. This was in the form of the syntactic frame of the mother's actual utterance, with all the content words replaced by nonsense items. Consider again the verb call. One of the mother's utterances to her child had been “Why don't you call Daddy?”. For this item in the syntax-information condition the adult participant was shown the nonsense-replaced version “Why don't ver GORP telfa?”. Another of the maternal utterances was “I'm gonna call Markie” and for this the participant was shown “Mek gonna GORP litch”; etc. Finally, a third set of participants watched the videotapes while also being shown their matching nonsense-containing syntactic frames, that is, a scene plus syntax combination.

Two results from such prior experimentation are particularly relevant for our present purposes. The first has to do with the varying usefulness of observational versus syntactic cues, depending on the verb type. Situational evidence taken alone led to some success when the targets were concrete action terms such as push and catch (35-50% accuracy) but was an especially poor cue for mental expressions such as want, know, like and think (0% accuracy). The findings in the syntactic condition of this experiment were strikingly reversed. Syntactic frames provided particularly strong support for the acquisition of mental verbs (90% accuracy) but were far less helpful in the case of concrete verbs (40% accuracy). In short, if observation isn't informative then the information has to come from elsewhere; here, from syntactic context.

It remains to be noted, however, that the videotaped scenes of mother-child interaction that subjects in these experiments observed were not well designed to elicit conjectures about belief verb use; that is, they were not discourse settings of trickery, oddity, or false belief. In the present experiments we will try to put the world back into the learning equation for these hard words by introducing them in the kind of situational context that we conjecture to be especially useful in amplifying their salience: the false belief situation. In a related regard, one further result of interest emerged from the original HSP findings. This has to do with the power of converging cues. Experimental participants who received both situational (the videotaped scenes) and syntactic (the nonsense-containing frames) information about the mystery words were close to ceiling in identifying both action and mental-content verbs (approximately 80% success rate overall; see particularly Snedeker & Gleitman, 2004 for a replication that systematically varied and combined several cue types).

1.4 Summary, and an experimental prospectus

Our group of investigators has claimed that the kinds of finding just summarized for adults are suggestive as well for why the very young child's vocabulary has the character that it does. The child is predicted to be delayed in the acquisition of mental-content terms owing primarily to the lack of linguistic resources that are the best cues to the identification of such items. As the child builds up distributional and syntactic knowledge of the exposure language, these linguistic cues contribute to the learning of abstract vocabulary items, the belief verbs in particular. Of course, it is never denied that conceptual changes may exert collateral influences in the same directions, though not measured in these prior experiments.

In the studies now to be presented, we set out to identify the contribution of syntactic cues (e.g., sentential complementation) and potentially helpful cues from observation (the presence of a false belief) to the identification of belief predicates.

2. Structural and situational cues to the belief vocabulary: experimental approaches

In this section, we present three experiments. The first two, adapting HSP methods, are designed to understand conditions under which adults are likely to utter terms that express mental acts and states, particularly beliefs. This probe into the conditions of adult utterance has prima facie relevance to the learning conditions for young children in this same regard: You can't acquire the word if your mother doesn't utter it. A subsidiary aim of these adult-participant experiments is to establish a baseline for the mapping of these words when the simulated learners are cognitively mature; this bears on the cognitive growth versus information growth accounts of vocabulary learning, as described in Section 1 (Introduction). Experiment 3 turns at last to preschool children who are in the first major verb-learning period of life, also testing adults for control and comparison purposes. This last experiment is designed to examine the extent to which the conditions under which adults speak are also the ideal ones under which children can acquire the belief terms.

2.1 Experiment 1: Eliciting mental verb utterance in false belief contexts

This experiment was designed to inquire how a linguistically competent and cognitively mature population interprets situations of action, desire, and belief as cues to describe these in mentalistic terms. At their strongest, such results could point to the input conditions for belief verb use by caregivers. Of course, creating conditions that increase salience and thus usage probability for the adult caregivers may not, ipso facto, have a like effect on their watching-listening offspring. Nevertheless, a first step in finding out how the mentalistic verbs are acquired is discovering the conditions under which they are uttered by the adult community.

Participants

Participants were 96 undergraduate students from the University of Pennsylvania and Bryn Mawr College. Students were enrolled in introductory psychology classes and received course credit for participation.

Materials

Brief silent scenarios showing actors engaged in simple activities were prepared and videotaped. These scenarios were designed to fall into three broad event/state classes: belief scenes (the critical items), action scenes, and desire scenes. In detail:

Belief scenarios (B): These depicted either an agent who was tricked or mistaken (false belief scenes, henceforth FB), or almost tricked or mistaken (true belief scenes, TB).6 For each of four belief scenarios, we actually constructed three variants: one TB version and two FB versions which varied in how far removed from reality or the particulars of the depicted event the false belief was. Thus there were 4 sets of belief scenes, all 3 variants within a given set showing the same event but with a different denouement (thus, 12 belief videos altogether). The following is an example of one such set:

A woman is sitting at her kitchen table drinking tea and reading the paper. On the table there is a flower vase, a teapot and the woman's teacup. Another woman walks in and begins wiping up the table and moves things around a bit. The first woman doesn't see or notice the changed position of the three pertinent objects. Rather, she simply reaches for her coffee cup while still reading. The objects are now positioned close enough to each other that such an absent-minded reach may result in the right or wrong item being selected. Each variant videotape now depicts a different outcome:

True Belief (TB) scene – In this variant the woman is lucky. Her hand fortuitously lands on the teacup, which she picks up and brings to her mouth.

Plain Vanilla False Belief (PFB) scene – The woman accidentally picks up the teapot and doesn't notice her mistake until the teapot is close to her mouth.

Zany False Belief (ZFB) scene – The woman accidentally picks up the flower vase and doesn't notice her mistake until the vase is close to her mouth.

The difference between PFB and ZFB scenes has to do with whether the false choice is one that has some appropriateness to the woman's implicit goal (after all, there is tea in the teapot) or is risible (there's only water in your prototypical flower pot).

Action scenarios (A) showed an agent performing some common action (e.g., a girl drawing a picture). There were 4 such scenarios.

Desire scenarios (D) showed an agent trying to do something or looking for something (e.g., a girl was trying to reach a box on a high shelf). There were 4 such scenarios.

Procedure

Participants watched a series of 12 of these video clips (all 4 A, all 4 D, and one variant of the 4 B scenarios) in individual sessions. To control for effects of order and item choice, two basic lists of 12 videos were created, with the order of variants of the B scenarios counterbalanced in order; the result was 6 stimulus orders. Participants were randomly assigned to these order lists. They were told that the clips had been designed to be shown to mothers and their young children and that they should guess what the mothers might say to their children when watching these videos together. Participants were asked also to provide a second response in each case (“What else do you think the mother might have said in this situation?”). After each clip the video was stopped to allow participants time to write down their answers. Each session lasted about 20 minutes.

Predictions

Based on previous studies using similar paradigms (Gillette et al., 1999), we expected participants to conjecture action verbs (A) more often than other categories across all scene types. Crucially, however, we expected the distribution of verb types to differ systematically as a function of scene types. A critical prediction was that the proportion of belief (B) verbs would increase in FB scenes to the extent that these violations of expectation really increase the observer's attention to actor's state-of-mind. For related reasons, we predicted that this effect would be amplified by the striking oddities in the ZFB variants. Finally, we predicted that if participants were given a second chance to describe the scene, their responses would show more B responses than their first guess, as the latter could have satisfied their need to describe the scene in terms of its concrete action content.

Coding

Verbs in participantsresponses were classified individually as A (Action: read, move), B (Belief: e.g., decide or notice), D (Desire: e.g., wish or try), or O (Other: e.g., let or have). (See Appendix 1 for the full list). Participantstotal responses per guess typically included more than one clause and hence more than one verb. Sample responses in the (first) guess for the PFB teacup scene were (verbs italicized):

The girl almost drank from the pot because she didn't realize her mug was moved.

She doesn't know her cup has been moved, so she thinks it's in the same place as before.

The coding in the first instance would include a (single) entry in 2 categories because the response contained at least one member of the A category (drink, move), and of the B category (realize). Similarly, the second sentence would be coded as A (move), B (know, think) and O (be).7

Results

The results were submitted to preliminary analyses to determine if presentation order and guess type had influenced the response styles. Each participant was assigned two scores based on the proportion of B responses he or she offered as a first and second guess for the belief (TB, PFB, and ZFB) scenes. Those scores were entered into an ANOVA with Order (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) as a between-subjects factor and Guess (1st, 2nd) as a within-subjects factor. The analysis returned no significant main effect of Order and no interaction between Order and Guess; for all subsequent analyses, we ignore Order as a factor. The analysis also revealed no significant main effect of Guess: participants produced B verbs on average 27% of the time in both their first and second guesses. Since, despite our predictions, this “second chance guess” yielded results so eerily identical to the first chance guesses, further analyses collapse across the two guesses (thus doubling the number of codable responses).

Verb type and mental state

Table 1 shows the pertinent results (the proportion of Other verbs was just 4% of all verbs offered so we will not discuss them further). As is obvious by inspecting the Table, participants overwhelmingly often (over 90% of the time) included an A verb in their response, no matter the scene type. D and B scenes were also clearly effective in increasing the proportion of responses of their respective categories in the descriptions of the corresponding scenes: The scenarios that we intended as demonstrating attempts to accomplish something increased D responses to 37.79% of all answers, while in other scene types the number of D responses hovered around 10%. The scenes that were meant to depict mental state as a relevant part of interpretation increased B responses (from around or below 10% in the A and D scenes to approximately 40% of responses in the FB scenes combined). In particular, the increase in report of a B response increases threefold (17% to 40%) as between the TB and FB categories. All the same the absolute proportion of B verbs is lower than might have been expected, a finding we retraverse in discussion below.

Table 1.

Proportion of responses (averaged over the 2 guesses) that include the three main different types of verbs (Exp. 1). Note that because responses usually contained more than one verb item, the proportions add up to more than 100%.

| Verb Category | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scene | Belief (B) | Desire (D) | Action (A) |

| Action (A) | 6.44 | 9.86 | 92.88 |

| Desire (D) | 9.31 | 37.79 | 90.42 |

| True Belief (TB) | 16.96 | 10.43 | 93.04 |

| False Belief (FB) total | 41 | 9.54 | 90.46 |

| Plain False Belief (PFB) | 39.06 | 8.58 | 91.42 |

| Zany False Belief (ZFB) | 42.98 | 10.53 | 89.47 |

We now turn to the statistical analysis of the results. As is clear from the Table, contrary to expectation, subjectsresponses did not differ in the kinds of verbs they contained between “zany” and plain vanilla FB scenes (this was confirmed by pairwise comparisons). In all further analyses we thus combine the results for ZFB and PFB scenes.

An ANOVA using the proportion of B responses elicited for each item as the dependent variable with Scene (A, D, TB, FB) as a between-items factor revealed a significant main effect of Scene (F(3, 16) = 48.64, p<.0001). The efficacy of FB scenes over A and D scenes in eliciting B responses was confirmed through pairwise comparisons (FB vs. A: 41% vs. 6%, t(10)=9.203, p<.0001; FB vs. D: 41% vs. 9%, t(10)=8.603, p<.0001 respectively). TB scenes seem to have an intermediate status, as they elicited reliably more B responses (18%) than did either A scenes (t(6)=3.552, p=.01) or D scenes (t(6)=2.85, p=.02), but reliably fewer such responses compared to FB scenes (t(10)= 5.66, p=.0002).

A similar ANOVA using the proportion of A responses as the dependent variable and Scene as a between-items factor returned no main effect of Scene. The same type of analysis over the proportion of D responses also did not yield a significant main effect of Scene. Nevertheless, pairwise comparisons revealed a statistically significant difference in proportion of D responses when D scenes were compared to A scenes (37% vs. 9%, t(6) = −6.67, p=.0005) and TB scenes (37% vs. 13%, t(6) = −3.72, p=.0098), but not FB scenes (37% vs. 16%, t(10)=.5, p=.62).

Discussion

This study was our preliminary attempt to examine the role of visual-situational input in eliciting the utterance of mental-content verbs in a scene description task. As predicted, participantsresponses overwhelmingly often (over 90% of the time) included action verbs, those that describe the unfolding event. Responses containing mental (belief or desire) predicates are comparatively less frequent, occurring in less than 20 percent of participant responses overall. Even in scenes specifically designed so that desire is highly relevant, desire states are reported only about 40% of the time. Similarly, in scenes designed so that belief contents are highly relevant, belief states are reported only about 20% of the time. Thus acts trump motives according to our adult respondents, at least under these constrained laboratory conditions. All the same, the false belief situations did raise the proportion of mental state reporting by a significant proportion, not only over their proportion in all scenarios (from 18% to 41%) but in their proportion compared to true belief situations (from 17% to 41%). If such conditions (in the real world) turn out to be those that elicit thoughts of state of mind in the adult speaker, perhaps they do so in the word-learning novice as well. To the extent so, false belief situations would in this way have created an environment specially tuned to the acquisition of mental predicates.

2.2 Experiment 2: A more stringent test - limiting the cues

Experiment 1 used silent videos, withholding all internal linguistic evidence as to the semantics of the nonsense items. In the present study, adult participants were asked to conjecture verb meanings under varying informational conditions, in an adaptation of the HSP. The question is how situational (action versus belief) and syntactic (transitivity vs S-complementation) evidentiary sources are used, singly and jointly, to solve the mapping task for belief verbs, by a cognitively competent adult population.

Participants

Participants were 56 undergraduate students from Bryn Mawr College enrolled in introductory psychology classes; they received course credit for participation.

Materials and Procedure

Given that there were no effects of stimulus list in Experiment 1, one list was randomly selected for use in this experiment. The list included 3 false belief (FB) scenes, 1 true belief (TB) scene, 4 action (A) scenes and 4 (D) desire scenes, as described previously.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three information conditions. For all conditions, participants were told that they were going to try to guess what particular verb mothers would say to their young children, as cued by the information given:

Scene Only Condition

Participants watched the video with no sound (as in Experiment 1). For example, one of the FB scenes was the one described in the Materials section of Experiment 1 as “the teacup scene.”

Syntax Only Condition

Participants were presented with a (written) list of 12 sentences that referred to the actions and states of mind depicted in each of the scenes (though these participants never saw the scenes themselves). Following the HSP procedure (e.g., Snedeker and Gleitman, 2004), the sentences had been doctored, Jabberwocky style, by replacing each of its content lexical items with a nonsense word. The verb itself, also a nonce word, was capitalized to show that this was the item that participants had to identify. The list contained 4 transitive frames with a direct object (e.g., Vamissa VAMS the torp), 4 frames with clausal complements introduced by that (e.g., Vamissa LODS that she ziptorks the siltap) and 4 intransitive filler frames (e.g., Vamissa TROMS).

Scene + Syntax Condition

This group of participants watched the same videos as in the Scene Only Condition, and received the written list of syntactic frames used in the Syntax Only Condition. The syntax and the scenes were paired such that the syntactic frames “matched” the scenes. Thus, the 4 B scenes were paired with clausal complement frames and the 4 A scenes were paired with transitive frames (the remaining filler D scenes were paired with intransitive frames). Participants looked at the syntactic frame, watched the scene and were asked to guess the verb using both pieces of information.

Predictions

In light of the results of Experiment 1, we expected that in the Scene Only Condition, action verbs would be the predominant response, but that A-bias would be greatly reduced for FB scenes. Similarly, we expected that sentence complement (S-comp) structures in the Syntax Only condition would enhance mental verb responses. Finally, we expected an overadditive proportion of mental verb responses in the Scene + Syntax Condition when the stimulus was a FB scene paired with an S-comp structure.

Coding

The proportion of B verbs guessed for each critical Scene type (A, FB) and Syntactic type (Transitive, S-comp) was computed.

Results

The results for test items are summarized in Table 2. Inspection of the Table shows that for A scenes, B guesses were very low across information conditions (from 4 to 7%). For these A scenes it is important to keep in mind that the syntax given was the transitive construction. In contrast, for FB scenes, the proportion of B verb responses increased (from 5% to 60% overall). This increase in B-verb proportion was even larger (up to 78 %) in the Scene + Syntax condition when S-comp syntax was paired with the FB scene. Thus, for the FB Items, information condition seemed to have an effect.

Table 2.

Mean percentage of belief verb guesses per item type (Exp. 2)

| Action (A) Items | |

| Scene Only Condition | 4.17 (9.6) |

| Syntax (transitive) Only Condition | 6.58 (14.05) |

| Scene + Syntax Condition | 3.95 (9.37) |

| Total | 4.91 (11.10) |

| False Belief (FB) Items | |

| Scene Only Condition | 44.44 (32.46) |

| Syntax (S-comp) Only Condition | 59.68 (36.22) |

| Scene + Syntax Condition | 77.26 (34.95) |

| Total | 60.75 (34.95) |

The statistical analyses corroborated this pattern. Using the number of B verb conjectures as the dependent variable, we conducted a mixed model ANOVA with Scene Type (A, FB) as a between items variable and Information Condition (Scene Only, Syntax Only, Scene + Syntax) as a within item variable. The analysis resulted in a significant main effect of Scene Type (F(1,5)=1,082.41, p<0.001), and a significant main effect of Condition (F(2, 5)=10.63, p<0.005). However, these main effects were qualified by a significant interaction between Item Type and Condition (F(2,5) = 14.65, p<.005). As described above, for the A scenes, there were few cognitive state verb guesses and the number of guesses did not change as a function of condition (pairwise comparisons (Bonferroni), all p's >.6). In contrast, for the FB items, more B guesses were made in the Scene + Syntax Condition than in the Scene Only Condition (pairwise comparison (Bonferroni), p<.05). In the Syntax Only Condition B guesses were at an intermediate level for the FB items (S-comp frames). They did not differ significantly from either of the other conditions (pairwise comparisons (Bonferroni), all p's >.4). Thus, while overall more B guesses occurred for the FB items, information condition affected the number of B guesses for these items.

Table 3 shows the results presented by participants. From the Table it is evident that subjects in every condition made many more B guesses for the FB items than for the A items; however, this difference was greatest in the Scene + Syntax Condition because of the higher level of B guesses for the FB items in this Condition. Consistent with this pattern, a mixed-model ANOVA with Item type as the within subject variable and Condition as the between subject variable revealed a main effect of Item type (F(1, 53) = 176.01, p <.001. There was also a main effect of Condition (F(2, 53) = 3.43, p <.05. These main effects were qualified by a significant Item type by Condition interaction (F(2, 53) = 5.25, p <.01. As can be seen in Table 3, for the A scenes, participants across all conditions were equally unlikely to guess cognitive state terms (pairwise comparisons (Bonferroni), all p's >.5). In contrast, for the FB items, participants made more B guesses in the Scene + Syntax Condition than in the Scene Only Condition (pairwise comparison (Bonferroni), p<.05). Participants in the Syntax Only Condition were in between participants in the Scene Only Condition and the Scene + Syntax Condition in their proportion of cognitive term guesses. They did not differ significantly from either of the other conditions for the FB items (pairwise comparisons (Bonferroni), all p's >.3).

Table 3.

Mean percentage of belief verb guesses by participants per condition (Exp. 2)

| Scene Only Condition | |

| Action Scenes | 6.5 (3.70) |

| False Belief Scenes | 40.33 (3.79) |

| Total | 21 (18.40) |

| Syntax Only Condition | |

| Transitive Frames | 8 (1.4) |

| S-comp Frames | 55 (12.53) |

| Total | 28.14 (26.16) |

| Scene + Syntax Condition | |

| Action Scenes + Transitive Frames | 3.75 (4.79) |

| False Belief Scenes + S-comp Frames | 79.67 (8.62) |

| Total | 36.29 (41.02) |

Discussion

Once again when faced with the task of matching a scene with a potential verbal response (Scene Only Condition), participants overwhelmingly often (79% percent of the time) came up with action verb responses: Their bias was to describe the unfolding event with its motives presupposed and unmentioned. However, in those cases where a character's behavior was odd owing (presumably) to a false belief, mental verb conjectures increased significantly (to 45%) In Scene + Syntax trials where observational (FB) and syntactic (S-comp) cues converged on a false belief state, the formerly insalient B interpretations increased to almost 80% of responses. As always, it is a long distance from simulations to the real world, but we believe the results link plausibly to the conditions that inspire cognitively mature individuals to think about scenarios in terms of their motives, and thus to utter belief verbs. But do these inspirations exist in much the same way for the child listeners as well? If so, then they too will be most likely to interpret novel verbs as belief verbs under the same linguistic and extralinguistic conditions. The next experiment attempts to investigate this question.

2.3 Experiment 3: What makes you think you are hearing a mental verb? Situational and linguistic contexts

Now we ask when children (and adult controls) think that a novel verb that they are hearing is describing a mental event or state. Overall, the experiment is designed to see how the syntactic and situational cues uncovered in Experiments 1 and 2 conspire to predict preschoolersverb conjectures.

Participants

Participants included 34 children enrolled in Philadelphia daycares/preschools, ranging in age from 3;7 to 5;9 years (mean 4;5). Data from 3 more children were excluded from all analyses due to a failure to meet a pre-test threshold. An equal number of adults also participated. Most of these latter were undergraduate students enrolled in introductory psychology classes at the University of Pennsylvania who received course credit for their participation.

Procedure

Children were tested individually by a single experimenter. At the start of the experiment, children were invited to “watch some stories on the computer” with the experimenter. They were told that some of the people in the stories used funny words, words that the experimenter didn't know. The experimenter then explained that children's help was needed to understand what the characters were trying to say. We know from prior work that children are very willing to offer their assistance in this sort of setting, as they consider themselves the true intermediaries between fictional characters and the adult world (e.g., Fisher et al., 1994, Waxman & Gelman, 1986).

Children went on to watch a series of videotaped stories. All stories followed a fairytale format with a pre-recorded narrative that described the observed events. This format was chosen to ensure that children would maintain their interest. At the end of each clip, the participants received a prompt from one of the scene's characters describing what happened in the scene; the prompt was always a sentence in which the verb was replaced by a nonsense word. The experimenter repeated the sentence and asked the child what the nonsense word meant. (Adult participants were also individually tested in the same way but were given a mercifully shorter introduction to the word-guessing game.)

Stories were administered in 4 pseudo-random orders. Each subject saw a total of 12 stories (scene-type/syntax combinations). These included 4 desire scenes plus 8 belief scenes (2 of each of the 4 possible belief type-frame combinations without repetition within a single belief set).

Participants completed this task in two sessions interrupted by a short break. This scheduling was to ensure that even the youngest children would be able to complete the task. Overall, participants were successful in coming up with a verbal response: missing responses accounted only for 2.2% of the child data and 0.7% of the adult data. No child who had passed the pretest failed to complete the full sequence.

Materials

The critical test items consisted of a set of 8 belief scenes ranging in length from 33.07 sec to 69.21 sec (M=53.25). Each belief scene had four variants which were created by fully crossing two factors: type of belief (true vs. false) and type of syntactic frame within which the novel verb was uttered (transitive frame with a direct object vs. clausal complement introduced by that). The following is an example of what participants heard and saw during a belief scene (and its variants):

Once upon a time there was a little boy named Matt who had a sick grandmother. One day his father says to him, “Take this basket of food to your sick grandmother; it will make her feel better.”

False Belief (FB) scene:

So the little boy, Matt, says, “Okay.” And so Matt walks to his grandmother's house through the spooky forest where he meets a big, bad cat.

“Where are you going with that basket of food?” asks the cat.

“To my sick grandmother,” says Matt.

The cat says to himself, “I will trick the boy so I can steal his food!” The cat runs to the grandmother's house before the little boy gets there. He locks her grandmother into the closet and hides under his grandmother's blankets.

Matt knocks on the door and goes over to his grandmother's bed. “Hi, grandmother. Here is a basket of food to make you feel better.”

[S-comp Frame] Cat: “Did you see that? Matt GORPS that his grandmother is under the covers!”

[Transitive Frame] Cat: “Did you see that? Matt GORPS a basket of food!”

True Belief (TB) scene:

So the little boy, Matt, says, “Okay.” And so Matt walks to his grandmother's house through the spooky forest where he meets a big cat.

“Where are you going with that basket of food?” asks the cat.

“To my sick grandmother,” says Matt.

The cat says, “I am sorry your grandmother is sick. Please let me help you carry the basket of food to your grandmother.” [Matt hands the basket to the cat and they continue to his grandmother's house].

Matt knocks on the door and goes over to his grandmother's bed. “Hi, grandmother. Here is a basket of food to make you feel better.”

[S-comp Frame] Cat: “Did you see that? Matt GORPS that his grandmother is under the covers!”

[Transitive Frame] Cat: “Did you see that? Matt GORPS a basket of food!”

The participantstask was to identify the meaning of GORP on the basis of the combination of observational and syntactic cues present within a single variant.

A total of 4 desire (D) scenes were used as fillers. These scenes were shorter than test stimuli, ranging in length from 9.14 sec to 31.07 sec (M=19.61). In D scenes, a person was either trying to do something (e.g., reach a teddy bear), or expressing strong emotion over not being able to do something (e.g., getting out of a locked room). In such scenes, the target verb always appeared with an infinitival complement:

Desire (D) scene:

Once upon a time there was a boy who liked to hug his teddy bear. But his teddy bear was way up high so the boy couldn't reach it. [The boy tries to reach the toy]

[Infinitival Frame] Boy: “I PLEEB to get my teddy bear.”

In addition to the test items, 3 pretest video clips were constructed. These pretests were short (6 sec) clips of simple actions without narration, designed to identify children who did not grasp the general nature of the word-guessing task. For instance, in one of these clips, a boy was shown throwing a large ball in the air a number of times. At the end of the clip, the boy said: “I'm DOLTING”. At this point, the experimenter repeated the sentence and asked the child what it meant. If the child responded nonsensically or provided no answer, the experimenter then showed the clip again and prompted for a response. Only children who passed at least two of the three pretests were allowed to complete the main phase of the experiment.

Predictions

On the basis of Experiments 1 and 2, we expected that the FB scenarios would render the actorsinferred states of mind more salient and thus would be significantly more likely than the TB scenarios to yield mentalistic interpretations. Additionally, based on previous studies (e.g., Gillette et al., 1999), we hypothesized that S-comp frames would promote belief verb conjectures. Our main hypothesis was that the two cues together (FB scenarios/S-comp verbal descriptions) would be especially supportive of mentalistic conjectures; that is, that the identification procedure for vocabulary is a probabilistic multi-cue constraint satisfaction system (Gleitman et al., 2004). An important sub-hypothesis was that syntactic cues would largely overwhelm observational biases when these cues were in conflict (the FB scene/T frame and TB scene/S-comp frame conditions). This hypothesis was based on the almost categorical tendency for nonsense sentence-complement sentences to elicit cognitive verb conjectures in prior work (Snedeker & Gleitman, 2004) and in general the statistical though not categorical priority of linguistic cues for both children and adults (e.g., Fisher et al., 1994). A related prediction was that the patterning of child and adult responses would be approximately the same, consistent with the information change hypothesis rather than the developmental change hypothesis (as described in the Introduction to this paper).

Coding

Responses were coded for two properties:

Verb type: Individual verbs in participantsresponses were coded under the categories action (A), belief (B), desire (D) and Other (O). For a complete list of verbs offered by the child and adult participants, see Appendix 2.

Strict frame compliance: The verbs in participantsresponses were also coded for whether they were legitimate (“grammatical” or “acceptable”) in the syntactic frame of the query that was posed. So for example the response “He ate all” to the frame “Matt DAXES that the cookies are all gone” was coded as non-frame compliant because the verb eat does not accept complement clauses. This analysis is meant to capture even more fine-grained differences among verb syntactic privileges than our coding into 4 types reveals. Not all belief verbs occur in the kind of S-comp structure that we used as stimuli, namely cases in which the embedded sentence is introduced with that and contains a finite verb (“I think that he is dancing”). For instance, verbs of questioning such as wonder do not (or “hardly do”) occur with that complementizers; rather, with if or whether (“I wonder if/whether grandma found the basket”). Strictly frame compliant responses, then, were coded when the participant offered a verb which fit this more restrictive criterion. Notice also that a one word response such as “think” but also a multiple word response such as “He thinks the cookies are all gone” both can meet the criterion of frame compliance and were so coded.

Results

The effect of stimulus order was nonsignificant for both child and adult participants, so all further analyses collapse across order groups.

Actions speak louder as words

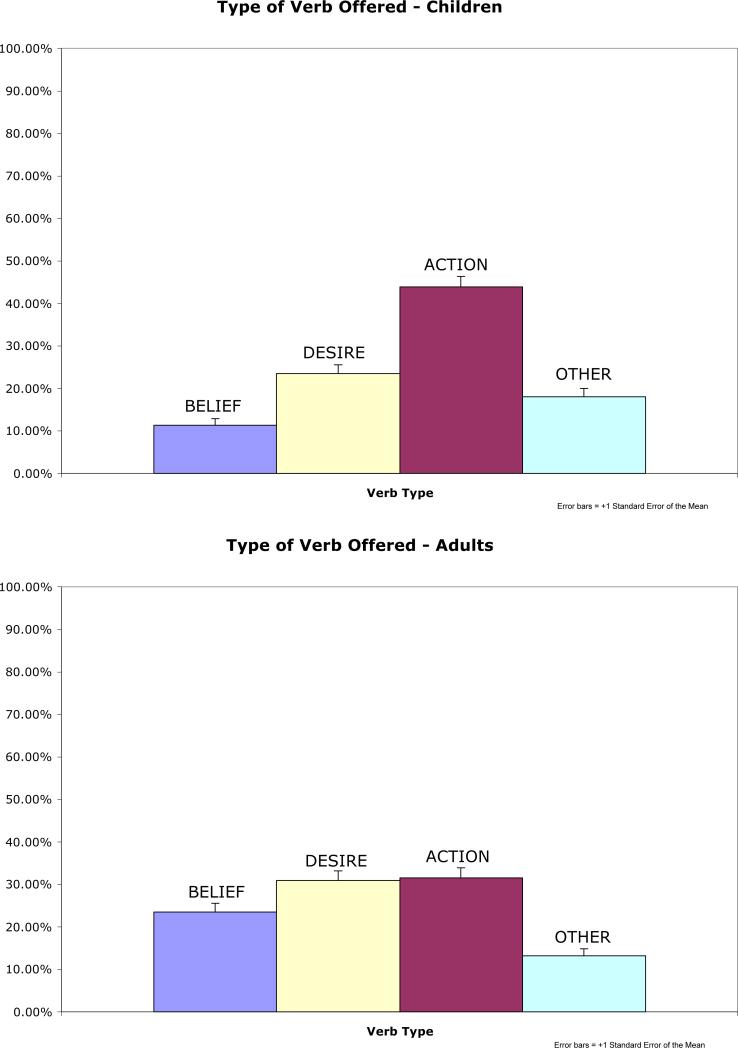

Figures 1a and 1b show the verb response types for adults and children respectively. What jumps out at the eye immediately is the high incidence of A verbs in both populations (31.60% and 43.90% of responses for adults and children respectively). For the children, even if we add together both types of mentalistic response (D and B types), they are still outnumbered by A responses for the children (35% versus 44% respectively) though not for the adults. Moreover, the belief verbs are especially dispreferred by both age groups (23.5% and 11.3% of all adult and child responses respectively). There were 4 D scenes and 8 B scenes, so in a fair world we ought to see twice as many B verb responses as D verb responses, but that is not what happened: D responses are more than double the B responses for children (23.5% versus 11.3%) and a difference in the same direction is nearly as dramatic for adults (30.9% versus 23.5%).8 These findings underline the point that the actions rather than the states of mind of the character are assumed under standard circumstances to be the topic of the conversation – that which is probably being spoken about, whether or not it's also what's being thought about. 9

Figures 1a and 1b.

Overall Percent of Verbs Offered in Exp. 3

Going mental

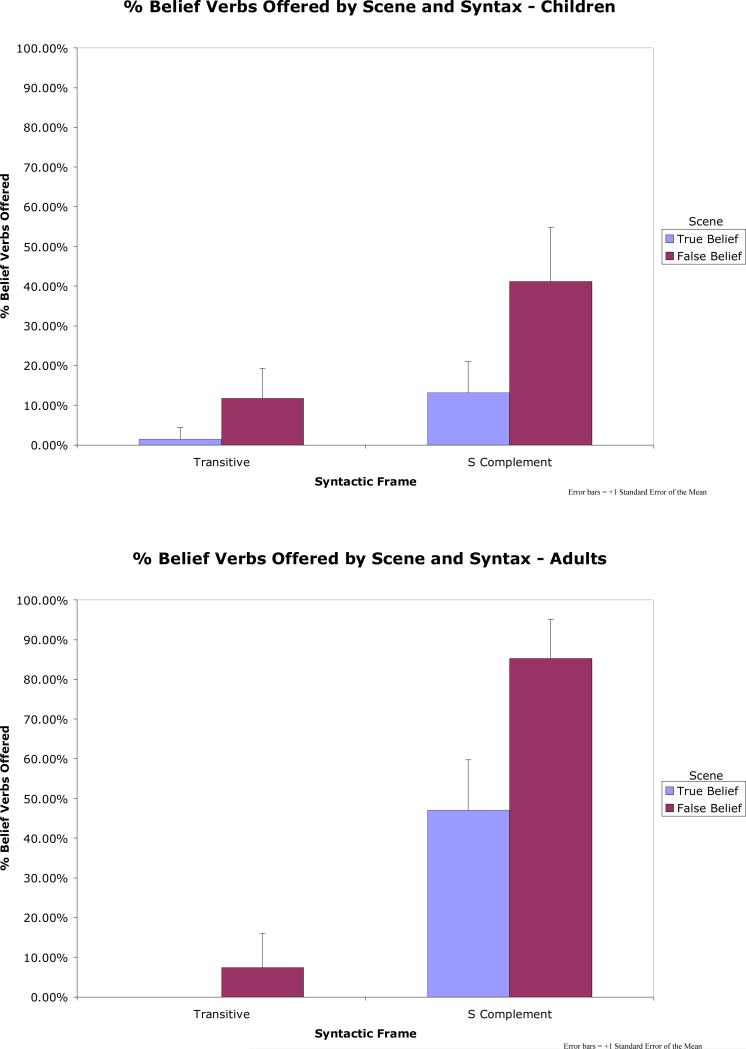

Using the number of B verbs offered by children and adults as the dependent variable, we conducted two separate 2×2 repeated measures ANOVAs with Scene (TB, FB) and Syntax (S-comp, T) as within-subject variables. Results are presented in Figure 2a and 2b (see also Table 4a and 4b for a detailed breakdown of all verb responses). In both cases, the analyses revealed a significant main effect of Scene (children: F(1, 33)=21.78, p<.0001; adults: (F(1, 33)=22.89, p<.001). Despite the strong bias toward action verb expression, attention to knowledge state (that is, the proportion of B responses) emerges from the background when the scene is one of false belief. For the adult subjects, these proportions almost double, rising from 23.5% in the TB situation to 46.3% in the FB situation. For the child subjects, the results are even more dramatic not only because the base rate of B verb response is so low for the TB situation (7.4%) but because it more than triples in the FB scenarios (26.5%). No wonder that mistaken states of knowledge and belief are the essence of theatre, both in farce and tragedy.

Figures 2a and 2b.

Percent of Belief Verbs, by Scene and Syntax (Exp.3)

Table 4a.

Percent verb type by Scene and Syntax (Exp. 3) - Children

| Verb Type Offered - Children | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Belief | Action | Desire | |

| Scene | |||

| True Belief | 7.4 | 58.8 | 3.7 |

| False Belief | 26.5 | 39.7 | 8.1 |

| Desire | 0 | 59 | 33.1 |

| Syntax | |||

| S Comp | 27.2 | 29.4 | 6 |

| Transitive | 6.60 | 69 | 6 |

| Infinitival | |||

| Scene and Syntax | 0 | 33 | 58.8 |

| FB + S Comp | 41.2 | 20.6 | 8.8 |

| TB + S Comp | 13.2 | 38.2 | 2.9 |

| FB + Transitive | 11.8 | 58.8 | 7.4 |

| TB + Transitive | 1.5 | 79.4 | 4.4 |

| Desire + Infinitive | 0 | 33.1 | 58.8 |

Table 4b.

Percent verb type by Scene and Syntax (Exp.3) – Adults

| Verb Type Offered - Adults | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Belief | Action | Desire | |

| Scene | |||

| True Belief | 23.5 | 49.3 | 1.5 |

| False Belief | 46.3 | 33.8 | 4.4 |

| Desire | 0.7 | 11.8 | 86.8 |

| Syntax | |||

| S Comp | 66.2 | 16.9 | 2.9 |

| Transitive | 3.7 | 66.2 | 2.9 |

| Infinitival | 0.7 | 11.8 | 86.8 |

| Scene and Syntax | |||

| FB + S Comp | 85.3 | 5.9 | 5.9 |

| TB + S Comp | 47.1 | 27.9 | 0.0 |

| FB + Transitive | 7.4 | 61.8 | 2.9 |

| TB + Transitive | 0.0 | 70.6 | 2.9 |

| Desire + Infinitive | 0.7 | 11.8 | 86.6 |

The ANOVAs also resulted in a significant main effect of Syntax (adults: F(1, 33)=157.58, p<.001; children: F(1, 33)=24.59, p<.0001). In scenes with a transitive prompt, B verbs occurred in only 3.7% of adult responses and 6.6% of the child responses. When presented with complement clause syntax, however, the number of B verbs increased in both adults and children (to 66.2% and 27.2% of all responses respectively).

Finally, the analyses revealed an interaction between Scene and Syntax (adults: F(1,33)=15.27, p<.001; children: F(1,33)=5.42, p=.026). As Figure 2 shows, the effects of cue combination lead differentially toward mental predicate conjectures. In detail, a transitive verb presented in the TB scene context never elicits a B verb by either adult or child subjects (0% and 1.5% respectively). When the syntactic probe is S-comp, even in the TB situation, the rate of B verb responding rises very dramatically for adults (to 47.1%) but only slightly for children (to 13.2%). But when the listener receives both kinds of cue, the success in conjecturing a B verb interpretation is remarkably enhanced. For adults the effect is almost categorical when the situation is FB and the probe sentence is S-comp (85.5%). For the children the result is by no means as powerful absolutely, but the incidence of B verb conjectures triples compared to the TB situation (from 13.2% to 41%). Paired sample t-tests confirmed that the difference in number of B verbs between the most helpful (FB scenes/S-comp) and least helpful (TB scenes/T frame) syntax-scene combinations is significant for both age groups (adults: t(33)=−17.18, p<.001; children: t(33)=−3.95, p<.001). Thus the combination of syntactic and situational evidence is compelling enough to support the identification of belief verbs, even in our young preschool participants. A comparison of B verbs in the two ‘mixedcue combinations (TB scenes with S-comp syntax vs. FB scenes with T syntax) yielded a significant difference for adults (t(33)=4.73, p<.001) but not for children.10

An omnibus repeated-measures ANOVA on the number of B responses was conducted with Scene (TB, FB) and Syntax (S-comp, T) as within-subject factors and Age as a between-subject factor. Scene (F(1,66)=44.5, p<.001), Syntax (F(1,66)=164.28, p<.001), Scene*Syntax (F(1,66)=19.64, p<.001), and Syntax*Age (F(1,66)=41.8, p<.001) were all found to be significant. No other significant interactions were found. The Syntax*Age interaction was due to the higher impact of syntactic frame on adultsthan on children's choices: as we saw earlier, B choices increased much more dramatically between the T and S-comp conditions in adults (from 3.7% to 66.2%) than in children (from 6.6% to 27.2%).11

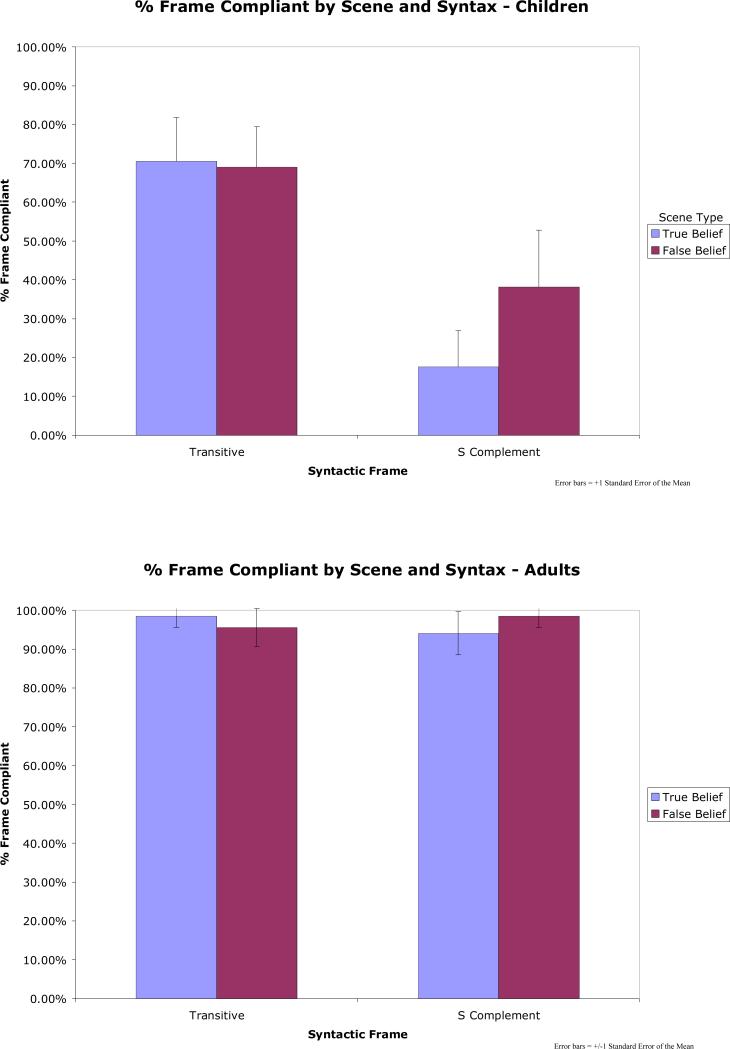

Saying it right

The percentage of strictly frame compliant responses offered by adults and children is given in Figure 3a and 3b. An omnibus analysis using the number of such responses as the dependent variable and Scene, Syntax and Age as factors resulted in significant main effects of Scene (F(1,66)=4.64, p=.035) and Syntax (F(1,66)=70.35, p<.001), as well as interaction effects of Scene*Syntax (F(1,66)=8.32, p=.005) and Syntax*Age (F(1,66)=65.58, p<.001). A Scene*Age interaction just missed significance (F(1,66)=3.4, p=.069).

Figures 3a and 3b.

Percent of strict Frame Compliance, by Scene and Syntax (Exp. 3)

We conducted two separate repeated measures ANOVAs over the number of strictly frame compliant responses offered by adults and children with Scene and Syntax as factors. Strict frame compliance in adults was nearly at ceiling, so the analysis resulted in no significant main or interaction effects. For children, the analysis yielded significant main effects of Scene (F(1,33)=4.55, p=.04) and Syntax (F(1,33)=84.22, p<.001), as well as a significant interaction of Scene and Syntax (F(1,33)=5.69, p=.023). The effect of Scene was due to a greater level of strict frame compliance for FB than for TB scenes (53.7% vs. 44.1% respectively). As for the effect of Syntax, S-comp frames met with strict frame compliance only 27.9% of the time, while T frames had a strict frame compliance level of 69.9%. The Scene*Syntax interaction arose because children were likely to be strictly frame-compliant for T frames regardless of the scene properties (70.6% for TB vs. 69.1% for FB scenes); however, for S-comp frames, there was a significant difference between TB and FB scenes (17.6% vs. 38.2%; t(33)=3.23, p=.003).

Discussion

Results of this experiment reveal the importance of both observational and syntactic cues for the identification of mental-state predicates. As in Experiment 1, FB scenes enhance the salience of the actorsinferred states of mind, as measured by a significantly higher proportions of mental-state interpretations of novel verbs than for TB scenes (26.5% vs. 7.4% in children's responses and 46.3% vs. 23.5% in adultsresponses). Syntactic information places even more striking constraints on the preferred construal of a scene: put differently, syntax acts as an attentional zoom lens (Gleitman, 1990) by bringing different interpretations into the listener's mental focus. While transitive frames with direct object-NPs almost never occurred with belief verbs, that-complements strongly encouraged belief verb construals (27.2% and 66.2% of all responses in children and adults respectively). In trials where observational and syntactic cues converged, nearly half (41.2%) of children's responses and the overwhelming majority (85.5%) of adultsresponses were belief verbs.

This experiment allows us to compare the use of extra-linguistic and linguistic-structural cues in adults and children in ways that we think are suggestive about the mapping problem as solved in vivo. A possible outcome was for adult responses to be more heavily influenced by the linguistic input and for children's responses to be determined more by the nature of the scenarios themselves. Such a finding would tend to support the position that mental state verbs are learned relatively late because the maturation (or construction) of the relevant concept space stretches over a long period and is not available for this task in younger verb learners. However the finding is that adults and children were sensitive to the same variables in the same approximate difference-magnitudes, lending some prima facie support to the information-structure interpretation of verb learning. Participants in both age groups converge on similar interpretations when given the same combination of extra-linguistic and linguistic cues (Figures 2a-b). This is not surprising in light of our analysis of the mapping problem. Old or young, our subjects are all novices in respect to gleaning the meaning of gorp and glick. If the procedures for solving these mapping problems for the vocabulary implicate the recruitment of both syntactic and situational cues, the findings in our experimental model are much as would be expected.

At the same time there are detailed differences in the adult and child response styles that are worth noting. First, child subjects provide a more variable picture than adults. To be sure, the rate of word learning in the real world is somewhat higher for older children and adults than it is for the preschool population we tested (P. Bloom, 2000) but it is likely that the rather large difference we see in our data is more indicative of adultsbetter understanding of laboratory task demands than a difference related to real word-learning rates. More likely to reflect the real facts of the matter is the greater potency of sentence complementation for eliciting mental-content responses from adults than for children (Table 4). Though all the participants are sensitive to this kind of language-internal cue, its relative weight is greater for the adults than for the children. Because the syntactic privileges of mental verbs are an important source of evidence for their meaning, such difficulties with complementation structures can explain the delay in the acquisition of mental verbs.

3. General Discussion

Ryan (age 3 years) returns from the pizza counter carrying a soda cup.

Mom: Put that down. You are not allowed to have soda. Put that down.

Ryan: Why?

Mom: You are not allowed to have soda. Put it down.

Ryan: It's not soda. The pizza man gave me water.

Mom: Oh...I'm sorry. I thought it was Coke. See.... there is a Coke sign outside, so I thought it was Coke.

Ryan: Oh that was funny. You were mad. Let's do that again.

3.1 Summary and discussion of the findings

This article posed the problem of why some words are harder for young children to acquire than others, even when they are frequent in the speech of caregivers. We chose the mental-content verbs to investigate this problem, just because they are iconic instances of such “hard” words. Two approaches were considered as accounts of the special difficulty of these words. The first was that preschoolers lack the conceptual wherewithal to think very well about thinking itself, with the consequence that they can't acquire words that refer to such predicates. The second posited that even if young children are adequate in this regard, they – and in fact, all the word learners, young and old – should find mentalistic terms difficult as a consequence of the initial procedure for solving the mapping problem for vocabulary; namely, by inspecting the extralinguistic contexts for a word's utterance (word-to-world pairing). Mental content words are not efficiently identified using this procedure because the situational contexts for talking about states and acts of mind are variable and subtle, when available to inspection at all.

Of course both linguistic and conceptual issues must play roles in understanding just when and how different aspects of the lexical stock of a language are acquired, so it is not our explanatory aim to choose between them; rather, our goal is to see how solutions to the word learning problem are apportioned between these two factors. As a first means of disentangling their contributions (and interactions), we employed adaptations of the so-called Human Simulation Paradigm. This kind of manipulation is designed to unconfound the conceptual versus informational factors by studying adults (so as to remove conceptual inadequacy from the learning equation) while varying their informational circumstances (so as to study the influence of increasing linguistic expertise on the procedures for vocabulary acquisition). Our first task was to discover extralinguistic circumstances that would naturally elicit the use of mental-content terms, especially from caregivers to their young offspring. We found our inspiration in that regard in an interchange between one of us (KC) and her 3-year old son, which appears as the epigram to this Discussion (“I thought it was Coke. See?...”). Situations of false belief seem to be quintessential triggers for talk of mental content.12

Experiment 1 investigated this hypothesis by asking adults “What might you say?” when confronted with videotapes depicting characters in both true belief and false belief states, compared with scenarios that are evidently most easily interpreted as depicting simple actions (e.g., drinking) or states of attempted desire-satisfaction (e.g., trying). As we showed (see Table 1), this conjectured talk overwhelmingly centers on the event – the action: Almost no matter the content of that event, our participants uttered verbs expressing concrete actions over 90% of the time, and for all scenario types. All the same, scenarios that emphasized the character's state of belief (true or false) also or alternatively elicited mental predicates about 30% of the time overall, and 42% of the time in the scenarios of false belief. Interestingly enough, exaggerated situations of pratfalls and risible confusions were neither required nor even especially useful in this regard, and so the “zaniness” factor that we probed as a way of upping the salience of false belief situations had no added effect. That there is a discernible false belief, even a quite prosaic one, seems to be sufficient.

Insofar as this first simulation is suggestive of relevance conditions for mental verb usage, we conclude:

(i) Actions trump beliefs in the interpretation of the extralinguistic world.

(ii) Observations that suggest the presence of a false belief can mitigate this bias and thus trigger talk of belief from adults.

Experiment 2 investigated the conditions triggering likely (adult) utterances of mental predicates in further ways. The experimental question now concerned the informational conditions that give rise to mental predicate conjectures for novel words. So the second innovation here was to offer subjects either (a) extralinguistic information of a kind suited to belief predicates (false belief) or not so suited (action scenarios); or (b) linguistic information of a kind suited to belief predicates (S-comp constructions) or not so suited (transitive constructions), or (c) both (a) and (b) together.

More precisely, we fully crossed situation (Action by FB) and syntax (S-comp by T) to see the effects of these information variables when they were present singly or jointly (either pitted against each other, or conspiring). So as not to contaminate the results with concordant distributional information, in the linguistic conditions we substituted nonce words for nouns as well as for the “mystery verb.”

The findings from this study strongly support the view that mental-predicate conjectures are insalient as interpretations of the passing scene. Any excuse for an action interpretation was seized upon by our participants. This excuse could be either (or both) an action scene or a transitive or intransitive construction. When any of these informational components were available, the proportion of belief verb conjectures was very low and about the same whatever the accompanying information (between 3% and 9%). A moment's reflection makes clear why this should be so. Every situation depicting a human (well, at least most humans, and if not comatose) implicates some state or states of mind, lots of them probably quite irrelevant to the present action. So it takes some special feature or property of that situation to suggest that these invisible mental states are somehow, in some special case, central to the ongoing discourse. The false belief situation seems to fit this bill. In the experimental false belief scenes, the proportion of belief verb responses increased (from 6.5% to 40.33% overall).