Abstract

The goal of this paper was to determine if trunk antagonist activation is associated with impaired neuromuscular performance. To test this theory, we used two methods to impair neuromuscular control: strenuous exertions and fatigue. Force variability (standard deviation of force signal) was assessed for graded isometric trunk exertions (10, 20, 40, 60, 80 % of max) in flexion and extension, and at the start and end of a trunk extensor fatiguing trial. Normalized EMG signals for five trunk muscle pairs (RA – rectus abdominis, EO – external oblique, IO – internal oblique, TE – thoracic erector spinae, and LE – lumbar erector spinae) were collected for each graded exertion, and at the start and end of a trunk extensor fatiguing trial. Force variability increased for more strenuous exertions in both flexion (p<.001) and extension (p<.001), and after extensor fatigue (p<.012). In the flexion direction, both antagonist muscles (TE & LE) increased activation for more strenuous exertions (p<.001). In the extension direction, all antagonist muscles except RA increased activation for more strenuous exertions (p<.05) and following fatigue (p<.01). These data demonstrate a strong relationship between force variability and antagonistic muscle activation, irrespective of where this variability comes from. Such antagonistic co-activation increases trunk stiffness with the possible objective of limiting kinematic disturbances due to greater force variability.

Keywords: Isometric trunk exertion, Trunk muscle recruitment, Force variability, Fatigue, Spine stability

Introduction

Trunk antagonist muscle activation is a commonly observed phenomenon (Andersson, Ortengren et al., 1977;Schultz, Cromwell et al., 1987;Seroussi and Pope, 1987;Lavender, Tsuang et al., 1992b;Lavender, Tsuang et al., 1992a;Marras and Mirka, 1992;Marras and Granata, 1997). It has been shown that some of this antagonist activity is required to equilibrate unequally distributed moments at various spinal levels (Thelen, Schultz et al., 1995;Stokes and Gardner-Morse, 1995). It has also been shown that some level of antagonist activation is necessary to maintain spine stability (Cholewicki, Panjabi et al., 1997), and it appears that this level of activation may be adjusted based on changing demands for stability. For instance, increasing destabilizing forces, such as adding a mass to the trunk, results in greater levels of trunk muscle antagonist activation (Cholewicki, Panjabi, and Khachatryan, 1997). This phenomenon is not isolated to the human spine, which by its inverted pendulum characteristics is inherently instable.

Franklin et al. investigated the ability to stabilize reaching movements in environments with unstable dynamics (Franklin, So et al., 2004). They used a robotic manipulator to generate unstable force fields of varying strength perpendicular to the movement direction. They found that the central nervous system (CNS) selectively recruited shoulder-arm muscles to increase stiffness perpendicular to the movement (in the unstable plane) without changing the net force or torque acting at each joint. As the destabilizing force increased, stiffness only in the unstable direction increased to ensure stability was maintained. They suggested that the CNS adapts to maintain stability while minimizing metabolic costs. Considering that the spine has considerable redundancy in force generation, we suspect that it will have similar adaptive capabilities.

There are a number of studies that have shown the CNS adapts to destabilizing factors that are external, such as unstable force fields (De Serres and Milner, 1991). Therefore, it is also possible that internal factors, such as force variability (neuromuscular noise), could produce compensatory muscle recruitment to maintain stability (Osu, Kamimura et al., 2004). For the spine, this most likely would be reflected in terms of antagonist activation. To test this theory, we used two methods believed to increase force variability: more strenuous exertions and fatigue. Consequently, the first two hypotheses of this study examined if force variability increases (1) with more strenuous exertions, and (2) with fatigue. The third hypothesis examined if antagonist activation also increases with more strenuous exertions and fatigue, suggesting that the CNS is utilizing antagonist activation to maintain spine stability.

Methods

Subjects

Twelve subjects volunteered for this study and signed the consent form approved by Yale University Human Investigation Committee. Anthropometric data are provided in Table 1. No subjects reported having neurological or musculoskeletal problems.

Table 1.

Number, mean (standard deviation) age, height, and weight of subjects.

| Females | Males | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 6 | 6 |

| Age (years) | 21.3 (.9) | 21.2 (.9) |

| Height (m) | 1.69 (.06) | 1.83 (.05) |

| Weight (kg) | 61.4 (3.5) | 84.1 (7.2) |

Data Collection

After appropriate skin preparation, Ag-AgCl, disposable surface EMG electrodes were placed with a center-to-center spacing of 5 cm over the following muscles on each side of the body: rectus abdominis (RA, 3 cm lateral to the umbilicus), internal oblique (approximately midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and symphysis pubis, above the inguinal ligament), external oblique (EO, medial to the mid auxiliary line at the level of the umbilicus), thoracic erector spinae (TE, 5 cm lateral to T9 spinous process), and lumbar erector spinae (LE, 3 cm lateral to L4 spinous process). A reference electrode was placed laterally over the 10th rib on the right side of the subject. All EMG signals were band-pass filtered between 20 and 450 Hz, differentially amplified (input impedance = 100 GΩ, CMRR > 140 dB) and A/D converted at a sample rate of 1600 Hz.

After verifying the quality of EMG signals on an oscilloscope, subjects were then placed in a specially built apparatus in the semi-seated position, which was designed to permit isometric contraction in trunk flexion, and extension (Figure 1A–B). A cable attached to a chest harness at approximately T9 was connected to a rigid bar, which served as a resisting force for isometric exertions. Force was registered by strain gauges mounted on the rigid bar and was displayed on an oscilloscope as a horizontal line. Force signals were also collected at a sampling rate of 1600 Hz.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A–D. Testing apparatus used for exerting isometric force in trunk (A) Flexion, and (B) Extension.

To establish the target force and maximum EMG, subjects were instructed to produce their maximum isometric exertion in trunk flexion, extension, and lateral bending to the left and right. EMG signals collected during these maximum trials were later used to normalize EMG data. Following a short rest period, subjects performed three isometric exertion trials in trunk flexion and extension at a constant force level corresponding to 10, 20, 40, 60 or 80 % of their respective maximal isometric trunk exertions. The target force was displayed as a horizontal line on the oscilloscope, and subjects were instructed to minimize the error between the target and measured force. The gain on the oscilloscope was maintained for all effort levels to ensure that visual resolution would not introduce a bias into the measured variability. Once subjects reached a steady state, EMG and force data were collected for three seconds. Testing was semi-randomized, so that half of the subjects started with the lowest force level and progressed to the highest, and the other half performed the highest force level and progressed to lowest exertion levels. The order of the exertion direction was also randomized. Subjects were given a period of approximately 30 seconds rest between trials.

At the end of these trials, subjects were asked to perform a fatiguing contraction in trunk extension. Subjects were asked to maintain a constant force of 40 % of maximum and asked to inform the tester when they felt fatigued. Data were collected for the first three seconds and the last three seconds of the fatigue trial before the target force could no longer be maintained.

Data Analysis

Dependent variables included force variability and average normalized muscle activity (% MVC). Force variability was measured as the standard deviation in the force signal, and not the standard deviation about some set point, such as the target line. Regression analyses (2 directions: flexion and extension) were used to determine if force variability increased with effort level. A paired t-test was used to compare force variability measured at the beginning versus the end of the extension fatiguing trial. Next, regression analyses (2 directions: flexion and extension × 5 muscle groups: RA, EO, IO, TE, LE) were used to determine if individual muscle activation increased with effort level. We expected that both agonist and antagonist groups during flexion and extension would have higher activation levels as effort level increased. And finally, 5 (1 direction: extension × 5 muscle groups: RA, EO, IO, TE, LE), paired t-tests were used to determine if muscle activation was significantly higher in the post-fatigue than the pre-fatigue state. To verify that erector spinae muscles were fatigued, spectral analysis was performed on extensor muscle EMG to determine the average median frequency of these four muscles. A paired t-test was used to determine if post-fatigue median frequencies were significantly lower than pre-fatigue, indicating erector spinae fatigue (Roy, De Luca et al., 1989;Roy, De Luca et al., 1990;Peach and McGill, 1998). A critical value of p=.05 was used for all analyses. Only main effects were considered without performing pairwise comparisons.

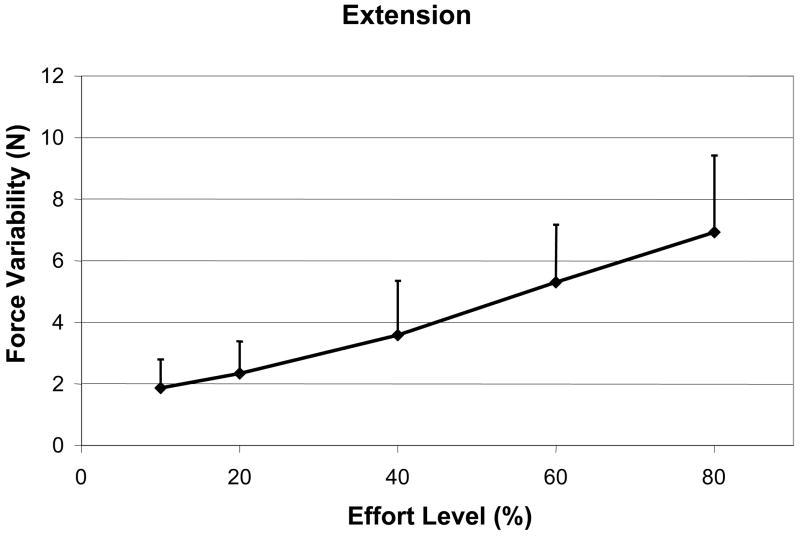

Results

The mean maximum trunk moment for each direction grouped by male, female and combined is shown in Table 2. In general, subjects were stronger in extension than in flexion, and males were able to generate more moment than females in both directions. Regression analysis for force variability showed that the effect of effort level was significant for flexion, and extension, i.e. slopes were significantly greater than zero (both p<.001), indicating more strenuous exertions produce more force variability. Force variability following post-fatigue during an extension effort was also significantly higher than pre-fatigue (p=.012). Regression analysis for muscle activation also showed that activation increased for all muscle groups as flexion effort increased (Figure 3A–B, Table 3). Interestingly, for the extension direction, EO and IO increased activation as effort increased but not RA (Figure 3C, Table 3). Following fatigue, a similar trend was observed with EO and IO increasing activation during extensor muscle fatigue, but not RA. Surprisingly, the two agonist muscle groups (TE, LE) did not change activation levels significantly with fatigue (Table 3); however, spectral analysis of the four erector spinae muscle groups showed a significant shift in the median frequency of the EMG signals to a lower frequency (p<.001), which is indicative of extensor muscular fatigue.

Table 2.

Mean maximum isometric trunk moments (standard deviation) computed about the L4–L5 level.

| Males | Females | Combined | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion (Nm) | 109 (34) | 64 (15) | 86 (34) |

| Extension (Nm) | 159 (53) | 131 (16) | 145 (41) |

Figure 3.

Figure 3A–D. Agonist trunk muscle activation in trunk flexion (A) and extension (D) exertions, and antagonist trunk muscle activation in trunk flexion (B) and extension (C) exertions.

Table 3.

Regression statistics for effort and fatigue effects. Bold typeface indicates a significant positive slope for muscle activation as a function of effort level or that muscle activation is significantly higher following a fatiguing trial.

| Effort Effect | Fatigue Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle | Flexion | Extension | Extension |

| RA | T=10.84

p<.001 |

T=−0.86

p=.395 |

T=0.39

p=.702 |

| EO | T=12.75

p<.001 |

T=3.27

p=.002 |

T=3.39

p=.006 |

| IO | T=11.24

p<.001 |

T=2.66

p=.01 |

T=3.55

p=.005 |

| TE | T=4.60

p<.001 |

T=7.59

p<.001 |

T=0.83

p=.427 |

| LE | T=3.85

p<.001 |

T=11.22

p<.001 |

T=1.39

p=.221 |

Discussion

There were three main hypotheses being tested with this study: 1) force variability increases with more strenuous trunk exertions, 2) force variability increases with extensor fatigue, and finally, 3) antagonist activation increases with effort level and fatigue. Results clearly support the first two hypotheses: force variability increased with more strenuous exertions and following fatigue. The third hypothesis is partially supported by the findings from this study. All antagonists except RA had higher levels of activation during more strenuous exertions and following fatigue. There appears to be an association between force variability and antagonist activation which we believe is related to the quality of neuromuscular control and possibly the requirement for maintaining spine stability. We will discuss this in more detail shortly.

One issue of concern was the fact that average muscle activation did not match effort level. Figure 3A and 3D clearly show that muscle activation in the agonists was below expected levels, especially for the higher levels of exertion. Maximum force levels were estimated by visually inspecting the oscilloscope and represented steady state during a maximum exertion trial. Inspection of the recorded force signals showed that peak force was approximately 17 % higher across subjects than their steady state values. Maximum EMG levels were obtained from peak values obtained during maximum exertion trials. This likely explains why EMG signals, expressed as %MVC, may have been underestimated. Regardless, we doubt that this would affect the trends in force variability (more variability with more strenuous effort and fatigue) and muscle activation patterns (higher antagonist activation with more strenuous effort and fatigue) found in the study.

Results, for the most part, match findings in the literature. A number of studies using other body segments found force variability increased with effort level (Sherwood, Schmidt et al., 1988; Slifkin and Newell, 2000; Hamilton, Jones et al., 2004) and Sparto et al. (Sparto, Parnianpour et al., 1997) also documented increased force variability following trunk extensor fatigue. Sparto et al. reported that extensor fatigue had a significant effect on IO activation (EO activation was not reported), but not on erector spinae muscle groups, which is consistent with our findings. They suggested that secondary muscles, such as latissimus dorsi, which had a significant increase in activation following fatigue, compensated for a decline in force-generating capability of primary extensor muscles (van Dieen, Oude Vrielink et al., 1993;Herrmann, Madigan et al., 2006). In terms of antagonist activation, a number of studies have documented increased activation associated with higher activation levels of agonists (Yang and Winter, 1983;Hebert, De Serres et al., 1991;Clancy and Hogan, 1997), and following trunk muscle fatigue (O’Brien and Potvin, 1997;Potvin and O’Brien, 1998;Granata, Slota et al., 2004).

Some of the antagonist activation is most likely needed to equilibrate the moment produced by the trunk agonist (Thelen, Schultz, and Ashton-Miller, 1995;Stokes and Gardner-Morse, 1995), but this would not explain the significant increase in antagonist activation with fatigue since moments about the spine are held constant. Therefore, we believe that a large component of the increased antagonist activation with fatigue was related to impaired neuromuscular control and an attempt to minimize kinematic variability. To show how force variability is related to antagonist activation, we predicted the antagonist activation at the end of the fatiguing contraction. Using the Force variability-Effort level graph, the force variability at the end of the fatiguing trial is equivalent to ~ 74 % of Effort level (Figure 4). At the 74 % of Effort level on the % MVC-Effort level graph for extension (Figure 3C), IO and EO activity would be equivalent to 13.5 and 10.5 % MVC respectively. EMG data collected at the end of the fatiguing trial showed that IO and EO had 12.5 and 9.25 % MVC, which is just slightly below predicted values.

Figure 4.

Force variability in trunk extension exertion with pre and post fatigue variability. Post fatigue force variability is equivalent to force variability at the 74% effort level.

One of the more interesting findings in the study was that this antagonist activation was selective. It is possible that the CNS recruits muscles that help maintain spine stability and avoids the recruitment of muscles that may be detrimental. Most likely, there is a physiological range for all the state variables, in which the each of the spine’s intervertebral joints can operate without injury. To keep the spine system within this bounded region requires that the CNS have adequate control over each intervertebral joint. If control is impaired, such as the case with effort-related and fatigue-induced force variability, then the likelihood of one or several of the joints crossing the safe boundaries increases. Parnianpour et al. showed that during flexion extension movements against extension resistance, fatigue increased trunk motion in both the coronal and transverse planes (Parnianpour, Nordin et al., 1988). Perhaps with fatigue, and possibly also strenuous exertions, the spine is operating closer to its injury boundaries. And perhaps, to ensure it remains safely within these boundaries when faced with impairment in neuromuscular control, the CNS selectively recruits muscles that can resist these out-of-plane internal disturbances, much like the selective recruitment of the shoulder muscles to stabilize movement in the plane of the unstable force fields mentioned in the introduction (Franklin, So, Kawato, and Milner, 2004). If this is true, to minimize out-of-plane trunk motion, the CNS may recruit obliquely oriented muscles, such as EO and IO. RA with its longitudinal orientation would not have the proper mechanical advantage to control for these out-of-plane motions, and may in fact exacerbate the problem, by requiring more strenuous exertions from the trunk extensors.

Although there appears to be a direct connection between antagonist activation and force variability, there are always other possible explanations for increased antagonist activation during more forceful exertion and during fatigue. There is some evidence that a “common drive” to agonist-antagonist pairs exists, meaning increased excitation to the agonist also excites the antagonist (De Luca and Mambrito, 1987). With fatigue, it is possible that stronger descending commands to the agonist (Ethier, Brizzi et al., 2007) also produce this spill-over effect. What is intriguing, if this is true, is the fact that synaptic inputs to motor neurons activating trunk muscles are not symmetric, as indicated by a lack of increase in RA in extension. Perhaps, the system is hardwired to activate the appropriate musculature in the trunk to maintain stability. Regardless, this explanation does not invalidate our hypothesis that increased antagonist activation with more strenuous exertions and fatigue serves to maintain spine stability in the face of higher force variability.

In summary, this study clearly documented a strong relationship between force variability and antagonistic muscle activation, irrespective of where this variability comes from. Both, effort-related and fatigue-induced force variability were associated with a similar increase in antagonistic muscle activation. One plausible purpose for such an antagonistic co-activation could be the increase in trunk stiffness with the objective of limiting kinematic disturbances due to greater force variability. Furthermore, an exciting possibility exists that this phenomenon is relatively simply controlled by a common drive to agonist-antagonist muscle pairs, as discussed above (De Luca and Mambrito, 1987; Ethier, Brizzi et al., 2007). In this way, the motor control system would automatically tune joint stiffness to counteract increased force variability without the need to consider the source of this variability. As the result, the rapid degradation in absolute precision of joint motion due to increased muscular effort or fatigue could be diminished.

Figure 2.

Figure 2A–D. Force variability in trunk (A) Flexion, and (B) Extension exertions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Grant Number R01 AR051497 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease.

References

- Andersson GB, Ortengren R, Nachemson A. Intradiskal pressure, intra-abdominal pressure and myoelectric back muscle activity related to posture and loading. Clin Orthop. 1977:156–64. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197711000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholewicki J, Panjabi MM, Khachatryan A. Stabilizing function of trunk flexor-extensor muscles around a neutral spine posture. Spine. 1997;22:2207–12. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199710010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy EA, Hogan N. Relating agonist-antagonist electromyograms to joint torque during isometric, quasi-isotonic, nonfatiguing contractions. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1997;44:1024–8. doi: 10.1109/10.634654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca CJ, Mambrito B. Voluntary control of motor units in human antagonist muscles: coactivation and reciprocal activation. J Neurophysiol. 1987;58:525–42. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.58.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Serres SJ, Milner TE. Wrist muscle activation patterns and stiffness associated with stable and unstable mechanical loads. Exp Brain Res. 1991;86:451–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00228972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier C, Brizzi L, Giguere D, Capaday C. Corticospinal control of antagonistic muscles in the cat. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1632–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin DW, So U, Kawato M, Milner TE. Impedance control balances stability with metabolically costly muscle activation. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:3097–105. doi: 10.1152/jn.00364.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granata KP, Slota GP, Wilson SE. Influence of fatigue in neuromuscular control of spinal stability. Hum Factors. 2004;46:81–91. doi: 10.1518/hfes.46.1.81.30391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AF, Jones KE, Wolpert DM. The scaling of motor noise with muscle strength and motor unit number in humans. Exp Brain Res. 2004;157:417–30. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-1856-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert LJ, De Serres SJ, Arsenault AB. Cocontraction of the elbow muscles during combined tasks of pronation-flexion and supination-flexion. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1991;31:483–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann CM, Madigan ML, Davidson BS, Granata KP. Effect of lumbar extensor fatigue on paraspinal muscle reflexes. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2006;16:637–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender SA, Tsuang YH, Andersson GB, Hafezi A, Shin CC. Trunk muscle cocontraction: the effects of moment direction and moment magnitude. J Orthop Res. 1992a;10:691–700. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender SA, Tsuang YH, Hafezi A, Andersson GB, Chaffin DB, Hughes RE. Coactivation of the trunk muscles during asymmetric loading of the torso. Hum Factors. 1992b;34:239–47. doi: 10.1177/001872089203400209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marras WS, Granata KP. Spine loading during trunk lateral bending motions. J Biomech. 1997;30:697–703. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marras WS, Mirka GA. A comprehensive evaluation of trunk response to asymmetric trunk motion. Spine. 1992;17:318–26. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien PR, Potvin JR. Fatigue-related EMG responses of trunk muscles to a prolonged, isometric twist exertion. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1997;12:306–313. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(97)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osu R, Kamimura N, Iwasaki H, Nakano E, Harris CM, Wada Y, Kawato M. Optimal impedance control for task achievement in the presence of signal-dependent noise. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1199–215. doi: 10.1152/jn.00519.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnianpour M, Nordin M, Kahanovitz N, Frankel V. 1988 Volvo award in biomechanics. The triaxial coupling of torque generation of trunk muscles during isometric exertions and the effect of fatiguing isoinertial movements on the motor output and movement patterns. Spine. 1988;13:982–92. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198809000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peach JP, McGill SM. Classification of low back pain with the use of spectral electromyogram parameters. Spine. 1998;23:1117–23. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199805150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin JR, O’Brien PR. Trunk muscle co-contraction increases during fatiguing, isometric, lateral bend exertions. Possible implications for spine stability. Spine. 1998;23:774–80. 781. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199804010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SH, De Luca CJ, Casavant DA. Lumbar muscle fatigue and chronic lower back pain. Spine. 1989;14:992–1001. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198909000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SH, De Luca CJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Emley MS, Crenshaw RL, Lyons JP. Fatigue, recovery, and low back pain in varsity rowers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22:463–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz A, Cromwell R, Warwick D, Andersson G. Lumbar trunk muscle use in standing isometric heavy exertions. J Orthop Res. 1987;5:320–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100050303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seroussi RE, Pope MH. The relationship between trunk muscle electromyography and lifting moments in the sagittal and frontal planes. J Biomech. 1987;20:135–46. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood DE, Schmidt RA, Walter CB. The force/force-variability relationship under controlled temporal conditions. J Mot Behav. 1988;20:106–16. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1988.10735436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifkin AB, Newell KM. Variability and noise in continuous force production. J Mot Behav. 2000;32:141–50. doi: 10.1080/00222890009601366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparto PJ, Parnianpour M, Marras WS, Granata KP, Reinsel TE, Simon S. Neuromuscular trunk performance and spinal loading during a fatiguing isometric trunk extension with varying torque requirements. J Spinal Disord. 1997;10:145–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes IA, Gardner-Morse M. Lumbar spine maximum efforts and muscle recruitment patterns predicted by a model with multijoint muscles and joints with stiffness. J Biomech. 1995;28:173–86. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)e0040-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen DG, Schultz AB, Ashton-Miller JA. Co-contraction of lumbar muscles during the development of time-varying triaxial moments. J Orthop Res. 1995;13:390–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100130313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dieen JH, Oude Vrielink HH, Toussaint HM. An investigation into the relevance of the pattern of temporal activation with respect to erector spinae muscle endurance. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1993;66:70–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00863403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JF, Winter DA. Electromyography reliability in maximal and submaximal isometric contractions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983;64:417–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]