Abstract

The relations of cumulative demographic risk and children’s temperament to mothers’ parenting behaviors were examined when children were 18 (T1, n = 247) and 30 (T2, n = 216) months of age. Mothers, nonparental caregivers (e.g., child care providers), and observers reported on children’s temperament to create a temperament composite, and mothers reported on demographic risk variables. Maternal responsivity and control were observed during 2 mother–child interactions at both time points. Cumulative demographic risk was related to low maternal responsivity concurrently and longitudinally, even after controlling for earlier temperament and responsivity, and demographic risk was positively related to maternal control at T1 and T2. Regulated temperament (i.e., low frustration and high regulation) was linked with high maternal responsivity at T1 and T2 and low maternal control at T2. Moreover, the positive relation between cumulative risk and maternal control at T1 was stronger when children were viewed as less regulated.

There has been a plethora of research on the links between maternal socialization attempts and children’s outcomes (Bugental & Grusec, 2006; Parke & Buriel, 2006). For example, mothers’ responsivity and low levels of assertive control have been linked to greater levels of social competence and healthy psychosocial adjustment in young children (e.g., Beckwith & Rodning, 1996; Campbell, Pierce, Moore, Marakovitz, & Newby, 1996; Gilliom & Shaw, 2004; Harnish, Dodge, Valente, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1995; Linver, Brooks-Gunn, & Kohen, 2002). Because less optimal maternal parenting behaviors have been linked with children’s maladaptive socioemotional outcomes, it is important to understand the factors that may be related to variations in mothers’ parenting behaviors. To this end, researchers have identified several such factors. For example, sociodemographic conditions can serve as sources of stress for families, and researchers have demonstrated that risk factors such as low levels of income, education, or both are linked to less optimal parenting and interactive behaviors (Liaw & Brooks-Gunn, 1994; McLoyd, 1990). Moreover, some authors have suggested that toddlers’ temperamental dispositions, such as “difficulty,” may be associated with maternal insensitivity, and these child characteristics also may ameliorate relations between demographic risks and parenting (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003; Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Rutter, 1990). To better understand the factors associated with maternal behavior, we examined the role of cumulative demographic risk, toddlers’ temperament, and their interaction in predicting maternal responsiveness and control strategies during early and late toddlerhood.

CUMULATIVE DEMOGRAPHIC RISK AS A DETERMINANT OF PARENTING

The term risk refers to a process that serves to increase the chances of experiencing a negative outcome in one or several domains of functioning by increasing the severity of problems or contributing to a longer duration of maladaptive functioning (Coie et al., 1993). Researchers have demonstrated that early risks such as low levels of education and income and living in a single-parent household are associated with decreased maternal responsiveness and increased negativity and control (e.g., Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, & Duncan, 1994; McLoyd, 1990). However, children and families rarely experience one risk factor in isolation; more often, multiple risks are experienced at once (e.g., Sameroff, Seifer, Baldwin, & Baldwin, 1993). Research on sociodemographic and familial risk factors has indicated that, as the number of risk factors increases, so does the likelihood of less responsive parenting behaviors and poor child socioemotional outcomes; this concept is identified in the literature as cumulative risk (Gutman, Sameroff, & Cole, 2003; Sameroff et al., 1993). Sameroff and colleagues (Gutman, Sameroff, & Eccles, 2002; Sameroff, Seifer, Barocas, Zax, & Greenspan, 1987) found that the accumulation of risk factors explained more variance in child outcomes related to behavior and academic achievement than did individual risk factors. Moreover, researchers have found cumulative risk to be associated with increased child physical abuse and maltreatment (Woodward & Fergusson, 2002) and relatively low parental positive affect and appropriate teaching strategies (Barocas et al., 1991). In a recent study, Kochanska, Aksan, Penney, and Boldt (2007) examined the relation of cumulative demographic risk to parenting behavior. Although their sample was relatively low risk, findings confirmed that greater demographic risk was associated with less affectively positive parenting behavior and more power assertion. Despite some demonstrated associations between risk and parenting behaviors, there is still a relative lack of evidence indicating why some high-risk parents are able to interact more responsively with their children, whereas others are less able to do so. Thus, a key question involves whether potential moderators, such as children’s temperamental traits, help to explain variation in parenting behavior.

TODDLERS’ TEMPERAMENT AS A DETERMINANT OF PARENTING

There is increasing recognition that toddlers’ temperament is related to parenting behaviors (e.g., Calkins, Hungerford, & Dedmon, 2004; Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003; Leve, Scaramella, & Fagot, 2001; Owens, Shaw, & Vondra, 1998; Putnam, Sanson, & Rothbart, 2002). Negative relations between difficult temperament (i.e., irritability, negative emotionality) in toddlers and mothers’ warmth and responsiveness have been found (Crockenberg & Smith, 1982; Hinde, 1989; Owens et al., 1998; Seifer, Schiller, Sameroff, Resnick, & Riordan, 1996; Van den Boom & Hoeksma, 1994). Further, researchers have demonstrated that mothers may overstimulate or respond intrusively to infants who are rated as irritable or high in negative emotionality (Calkins et al., 2004; C. L. Lee & Bates, 1985).

In this investigation, we examined the role of toddlers’ temperament in understanding maternal parenting behaviors. Two core dimensions of temperament that may be particularly important for parenting are children’s dispositional reactivity and regulation (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Reactivity includes negative emotionality, which refers to individuals’ tendencies toward irritability, negative mood, and high-intensity negative reactions as well as distress proneness and frustration (Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Sanson, Hemphill, & Smart, 2004). Self-regulation serves to modulate emotional reactivity. One aspect of self-regulation, effortful control, includes the abilities to voluntarily maintain or shift attention as needed and to inhibit or activate behavior, including emotion-related behavior, as appropriate (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Children who are high in effortful control are thought to be optimally regulated and are expected to be socially competent and well adjusted (Spinrad et al., 2007). Toddlers who demonstrate higher levels of negative emotionality and who lack the regulation skills necessary to deal with their negative emotions may be particularly challenging for parents. In support of this notion, Calkins and Johnson (1998) found that mothers of easily frustrated toddlers tended to expend more effort with their difficult children to circumvent possible frustration than did mothers with children less prone to frustration.

Although many investigators have examined children’s temperament solely using maternal reports, the use of multiple informants is optimal because different contexts may evoke different responses from children (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Multiple reporters offer a glimpse into the differences and consistency in children’s behaviors across the array of contexts they encounter in their daily lives. In addition, examining temperament ratings across contexts and observers partially eliminates the problem of reporter bias. Moreover, combined reports provide a more global evaluation of temperament; thus, researchers suggest assessing temperament at the same time point, using different assessment procedures, and then aggregating the measures across temperament dimensions to maximize the validity of temperament ratings (Henderson & Wachs, 2007; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Thus, our measures of toddlers’ temperament integrated information from mothers, nonparental caregivers, and laboratory observers.

As some authors (e.g., Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Rutter, 1990) have speculated, children’s temperament may serve as either a risk or protective factor under situations of sociodemographic adversity, yet this hypothesis has seldom been explored, particularly when risk is conceptualized as cumulative. Crockenberg and Leerkes (2003) suggested that, “creating a composite of risk factors expected to have the same impact on maternal behavior when they occur in conjunction with high negative emotionality would allow researchers to test interactive effects more effectively” (p. 65). Thus, in addition to testing the direct relations of cumulative risk and toddlers’ temperament to maternal responsivity and control, we also were interested in understanding whether toddlers’ temperament modified the relation of cumulative demographic risk to maternal parenting behavior. Testing this interactive effect will contribute to our understanding of the factors that explain the variation in the parenting behaviors of mothers under stress. It was expected that children’s low levels of regulated temperament would exacerbate the relation between risk and mothers’ parenting behaviors. Specifically, we expected that as cumulative demographic risk increased, mothers would be lower in responsivity and higher in control, particularly when children were seen as less regulated and more negative.

THIS STUDY

We examined the relation of cumulative demographic risk and temperament to mothers’ parenting behaviors at two time points (18 and 30 months of age). Across the second and third years of life, toddlers show increases in language skills, cognitive development, and self-regulation, as well as increases in noncompliance, attention seeking, and the ability to express emotions (Kopp, 1991). These developmental changes, particularly toddlers’ ability to verbally express negative emotion and need to demonstrate their individuality, may lead to parent–child conflict. As a result of this, mothers may feel it necessary to utilize control strategies more often. Additionally, mothers may begin to change their control strategies in favor of those that utilize more verbal commands and are more restrictive. Responsivity also is important at this age, as it fosters children’s rapidly developing language skills and cognitive development (Olson, Bates, & Bayles, 1990; Tamis-LeMonda, Bornstein, & Baumwell, 2001).

In addition to concurrent analyses, the relations were examined longitudinally. We expected that cumulative risk and temperament would predict mothers’ parenting behaviors even after controlling for earlier parenting and temperament. It is important to note, however, that temperament (Pedlow, Sanson, Prior, & Oberklaid, 1993; Slabach, Morrow, & Wachs, 1991) and parenting (Bradley, 1989; Masur & Turner, 2001) are generally stable over time, particularly over a 1-year period. Thus, our goal was to examine whether temperament and cumulative risk predicted maternal behaviors concurrently and over time, controlling for earlier parenting.

The sample used was relatively low risk overall. Similar to Kochanska et al., (2007), we were interested in whether we could replicate the already known relations between cumulative risk and less responsive and more controlling styles of parenting in a lower risk sample. If risk in this sample was found to predict less responsive and more controlling parenting behaviors, we would expect that relations might be even stronger in a sample with more variability in risk and parenting scores. Thus, this sample allows us to examine whether relatively low levels of risk are associated with the quality of mothers’ parenting behaviors.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were part of a longitudinal study of toddlers’ emotions, regulation, and social functioning and were recruited at birth through three local hospitals in a large metropolitan area. Families were approached for participation if the parents were adults (18 years or older), could read English fluently, and had infants who were born full-term and without birth complications. Of 352 families approached to participate in the study, the initial sample consisted of 276 families who agreed to participate and who could be located by phone or mail by the time the infant was approximately 6 months of age (more detail on selection and recruitment procedures can be obtained from the second author). The first laboratory visit occurred when toddlers were approximately 18 months old (T1) and a similar laboratory visit was completed a year later (T2).

At T1, 247 families participated in a laboratory visit. Two of these families were excluded from this investigation because their free play interaction was not codeable or complete (i.e., maternal language could not be translated, audio problems). Thus, the final sample at T1 was 245 toddlers (135 boys, 110 girls). The final sample at T2 included 216 families (119 boys, 97 girls). Of these 216 families, 212 also had T1 data (4 families who participated in the laboratory visit at T2 had not participated in the T1 visit). Toddlers ranged in age from 17 to 20 months (M = 17.8, SD = .52) at T1 and 27 to 32 months (M = 29.8, SD = .65) at T2. The sample was 73.9% White, 2.4% African American, 2.4% Native American, 0.8% Asian, 13.1% Hispanic, and 7.3% of other ethnicity.

Approximately 93.8% of couples were married. Family income ranged from less than $15,000 to over $100,000 per year, and the median income was between $45,000 and $65,000 per year. Mean years of education for mothers were 4.4 (SD = 1.0; 1 = grade school, 2 = some high school, 3 = high school graduate, 4 = some college, 5 = college graduate, 6 = master’s degree, 7 = PhD or MD). Forty-two percent of children had no siblings and 58% had one or more siblings. Mothers’ mean age at the child’s birth was 28.3 (SD = 5.8).

Procedures

At T1 and T2, mothers were mailed questionnaires prior to the laboratory visit, including measures of temperament, social competence, and family demographic information.

As part of a series of tasks during the laboratory assessment, toddlers were observed in situations involving negative emotions (e.g., toy removal, arm restraint, maternal separation). In addition, mothers were observed interacting with their toddlers during a free play and clean-up task. During the free play, mothers were given a standardized set of toys and told to interact as they normally would at home. After 3 min of play, mothers were told through headphones to have their children pick up the toys as if they were at home. The interaction was videotaped until the clean-up was finished or 3 min had passed (whichever came first). Videotaped interactions were subsequently coded for parent behavior. Upon completion of the visit, four research assistants, who observed the visit for behaviors including negative emotionality and emotion regulation, globally coded the children’s global laboratory behaviors. The families were paid for their participation, and toward the end of the laboratory visit, mothers were asked for permission to contact a nonparental caregiver (e.g., relative, day care provider, in-home babysitter) to complete questionnaires. Caregiver questionnaires were sent and returned through the mail (163 caregivers returned questionnaires at T1 and 140 at T2).

Measures

Demographic risk

Mothers completed a demographic questionnaire at T1 and T2. Questions included annual family income, mothers’ ethnicity, parent education, number of children in the home, marital status, parents’ age at birth of child participant, parental work status, occupation, and description of their job role. Based on work by Sameroff and colleagues (e.g., Sameroff et al., 1993), a cumulative risk index was created using demographic variables. Because risk could potentially change over time, we calculated a demographic risk index separately at each time point.

We based our cumulative risk index on seven demographic risk variables that were coded as either a 0 (no risk) or 1 (risk present). The variables included in the risk index were: (a) income (i.e., annual family income of less than $30,000 considered risk; McLeod & Shanahan, 1993; McLoyd, 1990); (b), marital status (i.e, single-parent status by divorce or separation or single parenthood considered risk; Bronstein, Clauson, Stoll, & Abrams, 1993; Klebanov et al., 1994; Pinderhughes, Nix, Foster, Jones, & The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2001); (c), ethnicity or race (i.e., non-White considered risk; Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1994; Hashima & Amato, 1994; McLoyd, 1990); (d) family size (i.e., three or more children in the home considered risk; Evans, Maxwell, & Hart, 1999; Jenkins, Rabash, & O’Connor, 2003); (e) maternal education (i.e., less than high school considered risk; Gutman et al., 2001; Hooper et al., 1998; Liaw & Brooks-Gunn, 1994); (f) mother’s age at birth of child participant (i.e., less than 20 years of age considered risk; Berlin, Brady-Smith, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002; B. J. Lee & Goerge, 1999; Pinderhughes et al., 2001); and (g) mothers’ occupational status (i.e., menial or unskilled laborer considered risk; McLoyd, 1990, 1998). If mothers were homemakers, the occupational status of their partner (if applicable) was used to represent occupational status. Risks were then averaged at each time point to create the cumulative risk indexes (to account for missing data). A summed risk index also was calculated and analyses were conducted using that score as well. Results came out similarly, thus we used the averaged risk index to account for missing data. At T1, 49% of mothers had zero risks, 31% had one, 13% had two, 6% had three, 2% had four, and less than 1% had five. At T2, 47% had zero risks, 35% had one, 10% had two, 5% had three, and 4% had four.

Children’s temperament

The investigation included multiple reports of temperament (mothers, caregivers, and four laboratory observers). Mothers and caregivers completed the Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire (ECBQ; Rothbart, 2000) to assess perceptions of temperamental negative emotionality and regulation at T1 and T2. Items were rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). The frustration scale assessed a toddler’s tendency to react negatively in various situations (12 items; e.g., “While having trouble completing a task, how often did your child get easily irritated?,” αs = .77 for mothers and .81 for caregivers at T1, .86 and .84 at T2). Toddlers’ regulation was assessed with the attentional focusing, attentional shifting, and inhibitory control subscales. Attentional focusing refers to the toddler’s ability to focus on an activity or task (12 items; e.g., “When engaged in play with a favorite toy, how often did your child move quickly to another activity?”; αs = .76 and .81 at T1, .79 and .85 at T2, for mothers and caregivers, respectively). Attentional shifting refers to the toddler’s capacity to shift attention appropriately (12 items; e.g., “During everyday activities, how often did your child seem able to easily shift attention from one activity to another?”; αs = .69 and .73 at T1, .76 and .71 at T2, for mothers and caregivers, respectively). Inhibitory control refers to the toddler’s ability to discontinue an activity when asked or to wait for a desired item or activity (12 items; e.g., “When asked to do so, how often was your child able to be careful with something breakable?” αs = .81 and .88 at T1, .90 and .88 at T2, for mothers and caregivers, respectively). A composite of regulation was created by standardizing and averaging the three subscales, as has been used in earlier research (Eisenberg et al., 2005; Eisenberg et al., 2004; Putnam, Gartstein, & Rothbart, 2006; Spinrad et al., 2007). Correlations were examined between the regulation composite and frustration. Due to moderately high negative correlations, rs (241, 208) = −.41 and −.45, ps < .01, for mother reports, and rs (170, 148) = −.59 and −.68, ps < .01, for caregiver reports, the two scales were combined to form one composite. Thus, frustration was reverse scored and then averaged with the regulation composite. The resulting composite was labeled regulated temperament; a high score indicated that a child had lower frustration and higher levels of regulation, whereas a low score reflected less regulated temperament (αs = .62. and .77 at T1, .64 and .79 at T2, for mothers and caregivers, respectively).

In addition to mother and caregiver report, four research assistants who observed the child throughout the laboratory assessment (which included several episodes designed to elicit negative emotion and regulation) completed a modifie version of the Infant Behavior Report (IBR; Bayley, 1969) after the laboratory assessment was completed. Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (absence of the behavior) to 5 (the behavior occurred most of the time). One item measured negativity (e.g., “The degree to which the child displays negative affect in response to either test materials or to the examiner or caregiver”; average agreement intraclass correlations [ICCs] = .84 and .88 for T1 and T2, respectively), and three items were used to measure regulation (e.g., “The degree to which the child remains focused on the tasks presented by the examiner”; average agreement ICCs = .81 and .85 for T1 and T2, respectively). The scores from the four raters were averaged to create an observed negativity scale and regulation scale. The correlations between regulation and negativity were examined and revealed moderately high negative correlations at T1 and T2, rs (123, 110) = −.41 and −.49, ps < .01, for T1 and T2, respectively. As with mother and caregiver reports, a composite was subsequently formed by reverse scoring negativity and averaging the two scales. This composite was again labeled regulated temperament, with a lower score indicating a child who was low in regulation and higher in negativity (αs = .84 and .85 for T1 and T2, respectively).

To maintain parsimony in analyses, and to create a less biased measure of child temperament, all three temperament composites were combined, as suggested in recent work (Henderson & Wachs, 2007). Correlations between mothers’ and care-givers’ ratings of regulated temperament were rs = .26 and .19, ps < .01 and .05 at T1 and T2, respectively. As expected, relations between adults’ reports and observer reports were relatively weak, rs = −.02 to .16 (Seifer, Sameroff, Barrett, & Krafchuk, 1994); however, we combined the reports to obtain a temperament score that reflected the toddlers’ temperament across contexts (Henderson & Wachs, 2007).

Maternal responsivity and control

Two undergraduate or graduate students who were not present during data collection coded mothers’ behavior in free play and clean-up from the videotaped interactions. Separate pairs of coders coded the free play and clean-up situations. The 3-min free play interaction was coded in 15-sec intervals, and codes were assigned for each interval on sensitivity and intrusiveness. All measures were coded on a scale ranging from 1 (none present) to 4 (high). Sensitivity was characterized by the presence of toddler-centered play in which the mothers were tuned in to the needs of their children and allowed this awareness to guide the interaction. Sensitive mothers were responsive to their children’s needs and acknowledged the children’s interests through vocalizations and actions. Intrusiveness was scored when the mothers interfered with the children’s activity, or took toys away while the children were still interested. Interrater reliability was calculated on 20% of the sample. Reliability scores for sensitivity were rs = .81 and .86, ps < .01 at T1 and T2. Reliability scores for intrusiveness were rs = .82 and .81, ps < .01, at T1 and T2. A composite measure of responsiveness was created by subtracting intrusiveness from sensitivity (Fish, 2001; Kochanska, Forman, & Coy, 1999), rs (243, 210) = −.42 and −.51, ps < .01, for T1 and T2.

During the clean-up segment, several forms of verbal control were coded in 15-sec epochs as 0 (did not occur) and 1 (occurred). The control strategies coded were: does nothing (mother does not use verbal control), gentle verbal control (using a relaxed and pleasant tone of voice, presenting clean-up as a fun game, singing, and using other positive strategies to motivate the child to clean up), assertive verbal control (mother used a firm, but not negative, tone of voice; parents were very matter-of-fact in their instructions), and off task (mother and child are not participating in clean-up). Forceful verbal control (strong control accompanied by negative affect) also was coded, but was rarely used. Mothers’ level of frustration or anger (affective measure consisting of voice quality, tone, and content) was coded on a scale ranging from 1 (none present) to 4 (high). Interrater reliability was calculated on 20% of the sample. Reliability scores ranged from – κ = .60 to .70, ps < .01 at T1 and from .80 to .87 at T2. Reliability scores for frustration or anger were rs = .81 and .94, ps < .01, at T1 and T2.

Principal axis factoring using promax rotation was applied to the maternal control and anger or frustration variables. Two factors were extracted at each time point with eigenvalues greater than 1. The first factor included anger or frustration, assertive verbal control, and gentle verbal control (with loadings of .85, .89, −.87 and .84, .88, −.73 at T1 and T2, respectively). The second factor included doing nothing and off task (with loadings of .68, .76 and .67, .73 at T1 and T2, respectively). The first factor was used for this investigation. To form the composite, gentle verbal control was reverse scored and the three items were averaged to create a composite score called control. Alphas indicated that the factor was reliable (αs = .90 and .82 at T1 and T2, respectively).

RESULTS

Attrition Analyses

T tests were conducted to determine whether families who dropped out from T1 to T2 (n = 33) were different on demographic and study variables than those who remained in the study. Mothers who did not participate at T2 were younger (M = 26.45) and less educated (M = 3.91) than those who remained in the study (Ms = 29.55 and 4.34), ts(246, 231) = 3.01 and 2.16, ds = .38 and .28, ps < .05, for age and education, respectively). No other significant differences emerged on any other demographic or study variables.

Descriptive Analyses

Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 2. Cumulative risk at T1 and T2 showed substantial nonnormalities (skew > 2.0). These variables were transformed using a square root transformation.

TABLE 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables at T1 and T2 by Child Sex

| Overall |

Boys |

Girls |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | M | SD | F | d | |

| T1 variables | |||||||||

| Regulated temperamenta | 3.78 | .51 | 1.50–5.19 | 3.74 | .49 | 3.83 | .53 | 0.23 | −0.18 |

| Observed responsivityb | 1.19 | .77 | −1.00–2.83 | 1.12 | .81 | 1.25 | .79 | 1.76 | −0.16 |

| Observed controlc | 0.61 | .31 | 0.33–1.42 | 0.62 | .32 | 0.58 | .29 | 1.02 | 0.13 |

| Cumulative risk | 0.14 | .48 | 0–1 | 0.17 | .20 | 0.11 | .15 | 6.50** | 0.34 |

| T2 variables | |||||||||

| Regulated temperament | 4.09 | .55 | 2.48–5.52 | 4.07 | .54 | 4.12 | .55 | 0.57 | −0.09 |

| Observed responsivity | 1.56 | .85 | −0.58–3.00 | 1.49 | .72 | 1.69 | .59 | 4.99* | −0.30 |

| Observed control | 0.49 | .20 | 0.33–1.33 | 0.52 | .23 | 0.45 | .16 | 5.14* | 0.35 |

| Cumulative risk | 0.15 | .19 | 0–1 | 0.13 | .17 | 0.17 | .21 | 1.08 | −0.21 |

Regulated temperament scores are reported prior to standardization for ease of interpretation.

Because intrusiveness was subtracted from sensitivity to form the responsivity composite, the range for responsivity includes negative values.

Observed control scores are reported prior to standardization for ease of interpretation.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Because there has been evidence that both parenting behaviors and temperament may sometimes differ for boys and girls (e.g., Jenkins et al., 2003; Owens et al., 1998), we examined sex differences in our study constructs. Two multivariate analyses of variance were conducted in total, one for each time point. Both analyses included maternal responsivity and control, cumulative risk, and regulated temperament. A multivariate sex difference was found using the T1 variables, F(4, 240) = 3.39, p = .01. Univariate tests revealed that mothers of girls had higher cumulative demographic risk scores than mothers of boys (Ms = .17 and .11, for girls and boys, respectively), F(1) = 6.50, d = −.32, p < .01. There were no univariate differences in parenting or temperament at T1.

A multivariate sex difference was found at T2 as well, F(4, 206) = 2.69, p < .05. Univariate tests revealed that during free play, mothers were observed to be more responsive to girls than to boys (Ms = 1.69 and 1.49, for girls and boys, respectively), F(1) = 4.99, d = −.30, p < .05. During the clean-up situation, mothers were observed to use more control strategies with boys than girls (Ms = −.15 and .12, for boys and girls, respectively), F(1) = 5.14, d = .31, p < .05. There were no univariate differences in demographic risk or temperament at T2. Because sex differences were found in the study variables, child sex was used as a control variable in all regression analyses. We also explored whether child sex served as a moderator of the relations among risk, regulated temperament, and maternal responsivity and control. None of the interactions were significant.

Correlations Among Study Variables

Correlations are presented in Table 3. Zero-order correlations among cumulative risk, temperament, and parenting behaviors revealed that cumulative risk was negatively related to responsivity and regulated temperament and positively related to maternal control at both time points. At T1 and T2, regulated temperament was positively related to observed maternal responsiveness and negatively related to control strategies. Additionally, correlations revealed that all study variables were moderately to highly stable over time.

TABLE 3.

Correlations Among Study Variables at T1 and T2

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 variables | ||||||||

| 1. Regulated temperament | — | |||||||

| 2. Cumulative risk | −.14* | — | ||||||

| 3. Responsivity | .19** | −.21** | — | |||||

| 4. Control | −.18** | .39** | −.29** | — | ||||

| T2 variables | ||||||||

| 5. Regulated temperament | .35** | −.16* | .24** | −.18** | — | |||

| 6. Cumulative risk | −.09 | .81** | −.23** | .36** | −.17* | — | ||

| 7. Responsivity | .17* | −.24** | .42** | −.38** | .27** | −.24** | — | |

| 8. Control | −.12 | .17* | −.28** | .35** | −.24** | .15* | −.34** | — |

p < .05.

p < .01.

The Relation of Risk and Temperament to Mothers’ Parenting Behaviors

Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to test the contributions of cumulative risk and children’s regulated temperament in predicting mothers’ responsivity and control. A separate regression was conducted at each time point (T1, T2, and longitudinal analyses from T1 to T2) for each maternal behavior. To test the hypothesis that children’s temperament may exacerbate the relation between risk and parenting behavior, we entered risk and temperament in the first step (along with child sex as a control variable) and entered Cumulative Risk × Regulated Temperament in the second step of the regression. Because we were interested in studying change in maternal behavior, in longitudinal analyses, we controlled for T1 parenting behaviors. Moreover, to predict parenting while accounting for concurrent temperament, we also controlled for T2 regulated temperament in longitudinal analyses. However, because cumulative demographic risk was highly stable over time (r = .81, p < .01), we did not control for concurrent demographic risk in the longitudinal analyses. Analyses were conducted without controlling for T2 temperament, and results did not change. All independent variables were centered prior to analyses.

The Relation of Risk and Temperament to Maternal Responsivity

Concurrent relations

Regression results predicting maternal responsivity can be found in Table 4. Findings indicated that maternal responsivity was predicted by concurrent T1 and T2 data, Fs(4, 234; 4, 211) = 5.75 and 7.79, ps < .001, for T1 and T2, respectively. Specifically, at both T1 and T2 there were main effects of cumulative demographic risk and regulated temperament. At both time points, risk was negatively related to maternal responsiveness, and regulated temperament was positively related to maternal responsivity (see Table 4). Neither of the interaction terms was significant.

TABLE 4.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Maternal Responsivity

| β | R2 | ΔR2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable, T1 maternal responsivity | |||

| Step 1 | .09 | ||

| Child sex | .11+ | ||

| T1 total risk | −.22*** | ||

| T1 regulated temperament | .16** | ||

| Step 2 | .09 | .00 | |

| Risk × Regulated Temperament | .01 | ||

| Dependent variable, T2 maternal responsivity | |||

| Step 1 | .13 | ||

| Child sex | .16* | ||

| T2 total risk | −.19** | ||

| T2 regulated temperament | .22*** | ||

| Step 2 | .13 | .00 | |

| Risk × Regulated Temperament | .05 | ||

| Dependent variable, T2 maternal responsivity | |||

| Step 1 | .24 | ||

| Child sex | .12* | ||

| T1 maternal responsivity | .33*** | ||

| T2 regulated temperament | .17** | ||

| T1 total risk | −.17** | ||

| T1 regulated temperament | .01 | ||

| Step 2 | .24 | .00 | |

| Risk × Regulated Temperament | −.06 |

Note. Standardized β weights are shown for the last step in the equation. βs from the final step are reported. ΔR2 represents the increment to R 2 associated with each block of variables when they are entered into the equation.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Longitudinal relations

To examine change in maternal responsivity, maternal parenting behavior at T1 and regulated temperament at T2 were entered into the regression as control variables in all longitudinal analyses. Child sex was entered into the first step of the regression. Regulated temperament at T1 and cumulative risk at T1 were used to predict T2 responsivity. Findings revealed that maternal responsivity could be predicted after controlling for T1 responsivity and concurrent temperament. Cumulative risk at T1 was a significant predictor of later responsiveness, F(6, 211) = 10.94, p < .001 (see Table 4). Risk was negatively related to responsivity. The interaction was not significant.

In sum, cumulative risk was negatively related to maternal responsivity in both concurrent and longitudinal analyses. Regulated temperament was positively related to maternal responsivity at T1 and T2 but not in longitudinal analyses after controlling for stability in responsivity and concurrent temperament.

The Relation of Risk and Temperament to Maternal Control

Concurrent relations

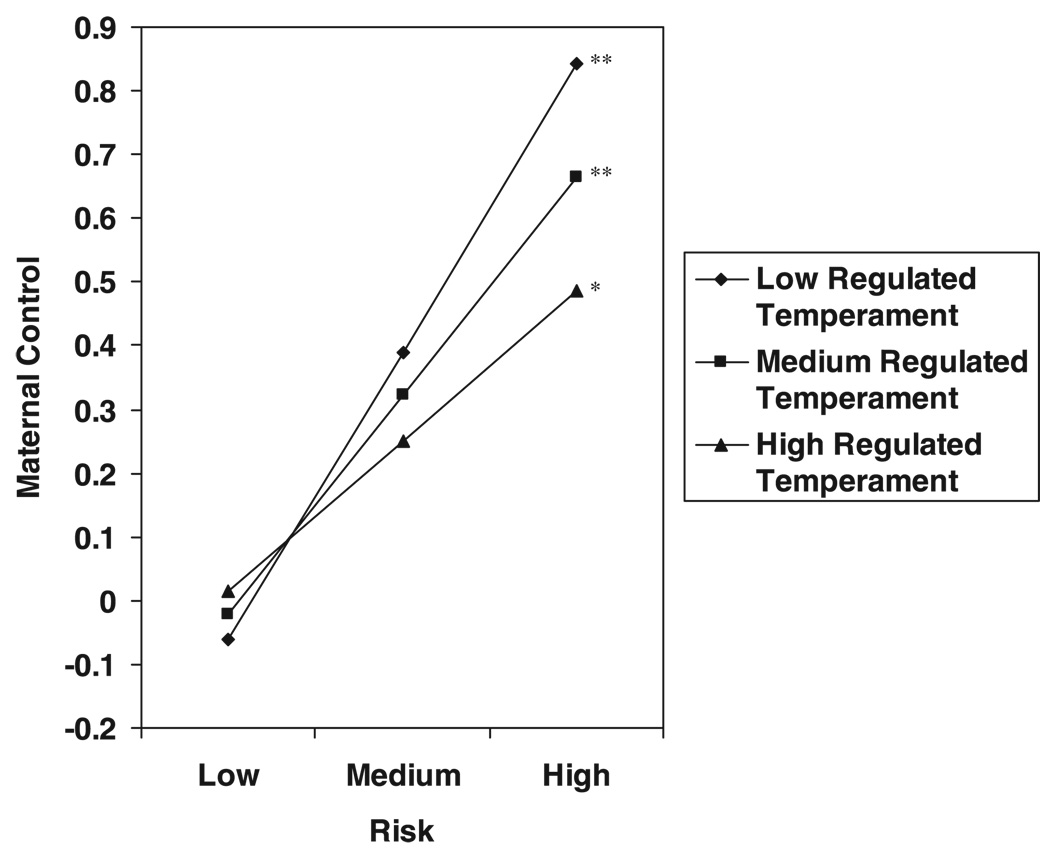

Findings indicated that maternal control could be predicted by concurrent T1 and T2 data, Fs(4, 244; 4, 210) = 13.74 and 7.44, ps < .001, for T1 and T2 data, respectively. Specifically, there was a significant effect of cumulative risk and regulated temperament at T1, such that risk was positively related to maternal control and regulated temperament was negatively associated with control (albeit marginally). At T2, regulated temperament was negatively related to observed control. There also was a significant two-way interaction between risk and regulated temperament at T1 (see Table 5). The interaction was probed using the simple slopes method as detailed in Aiken and West (1991). There was a significant positive relation between cumulative demographic risk and maternal control at all levels of toddlers’ regulated temperament. However, the relation was strongest for toddlers with low and moderate regulated temperament (slopes = 1.68 and 1.28, ts = 6.45 and 6.34, ps < .01), and was relatively weak for toddlers who were well regulated (slope = .88, t = 3.10, p < .05). See Figure 1.

TABLE 5.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Maternal Control

| β | R2 | ΔR2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable, T1 maternal control | |||

| Step 1 | .17 | ||

| Child sex | −.13* | ||

| T1 total risk | .38*** | ||

| T1 regulated temperament | −.08 | ||

| Step 2 | .19 | .02* | |

| Risk × Regulated Temperament | −.13* | ||

| Dependent variable, T2 maternal control | |||

| Step 1 | .12 | ||

| Child sex | −.14* | ||

| T2 total risk | .13* | ||

| T2 regulated temperament | −.24*** | ||

| Step 2 | .13 | .01 | |

| Risk × Regulated Temperament | −.11 | ||

| Dependent variable, T2 maternal control | |||

| Step 1 | .26 | ||

| Child sex | −.13* | ||

| T1 maternal control | .34*** | ||

| T2 regulated temperament | −.17* | ||

| T1 total risk | .09 | ||

| T1 regulated temperament | −.07 | ||

| Step 2 | .26 | .00 | |

| Risk × Regulated Temperament | −.06 |

Note. Standardized β weights are shown for the last step in the equation. βs from the final step are reported. ΔR2 represents the increment to R2 associated with each block of variables when they are entered into the equation.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

FIGURE 1.

Interaction between regulated temperament and cumulative risk, predicting maternal control at T1. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Longitudinal relations

To examine change in maternal control, we used maternal control at T1 as a control variable in predicting T2 maternal control. Moreover, we used concurrent (T2) regulated temperament as a control variable (in addition to child sex) to determine if earlier temperament would predict maternal control after statistically controlling for concurrent temperament. Temperament and demographic risk at T1 were used to predict T2 control. Maternal control could not be predicted after accounting for earlier parenting and concurrent temperament (see Table 5).

Thus, cumulative risk was positively related to maternal control at T1 and regulated temperament was negatively associated with maternal control at both T1 and T2. There was a significant interaction between risk and regulated temperament at T1.

DISCUSSION

Our findings revealed that cumulative demographic risk was directly related to mothers’ responsivity and control strategies. Cumulative demographic risk was associated with higher levels of control and lower levels of responsivity, concurrently at T1 and T2. Additionally, there was a longitudinal relation between risk and maternal responsivity, suggesting that risk may account for decreases in mothers’ responsivity over time. However, longitudinal relations were not found when predicting maternal control.

The direct relations between cumulative demographic risk and mothers’ responsivity and control further support and expand on literature suggesting that cumulative demographic risk is related to parenting behavior (Barocas et al., 1991; Kochanska et al., 2007; Woodward & Fergusson, 2002). A significant feature of this work, however, is that the association between cumulative demographic risk and maternal responsivity and control was present, even in a relatively low-risk sample. These findings are in contrast to previous work suggesting that families need to experience a moderate level of risk for cumulative risk to be linked with functioning (e.g., Sameroff et al., 1987). Kochanska et al., (2007) measured cumulative risk using a graded strategy (adding risk points for levels of risk rather than a simple presence or absence of each risk factor) and found that this more varied risk dimension was related to higher maternal control in a relatively low-risk sample. We used a more traditional approach to studying cumulative risk (i.e., dichotomous score for risk or no risk) and also found that risk was linked in expected ways to the quality of mothers’ interactive behaviors. Thus, together with the findings of Kochanska and colleagues, it appears that researchers should consider the impact of demographic risk factors, even in light of a relatively restricted range of demographic risk.

An additional finding that warrants comment is the longitudinal relation between cumulative risk and maternal responsivity. It is possible that the accumulation of risk, or chronic risk, may erode parents’ abilities to interact responsively with their toddlers over time, thus contributing to the decreases in responsivity we found from 18 to 30 months. Research on the effects of chronic versus transitory poverty mirrors this finding. For example, researchers have found that chronically poor families provided poorer quality childrearing environments (as measured by the HOME) than did families in transitory poverty (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Childcare Research Network, 2005).

In addition to cumulative risk, we also found that children’s temperament was directly associated with maternal parenting behavior. Lower levels of regulated temperament were associated with lower maternal responsivity at both time points and higher maternal control at 30 months. To date, evidence linking children’s temperament to parenting behaviors has been equivocal. Our findings add support to other research suggesting that less responsive parenting covaries with children’s negative temperamental characteristics (e.g., Hinde, 1989; Owens et al., 1998). These findings are strengthened by the fact that we aggregated our temperament measure across three contexts (Henderson & Wachs, 2007). Despite these concurrent relations, early temperament was not associated with changes in maternal responsivity or control over the second and third years of life. These findings are in contrast to previous work that has uncovered longitudinal relations between maternal unresponsiveness and children’s difficult temperament (e.g., Campbell, 1979; van den Boom & Hoeksma, 1994). Although we expected that a history of negative temperamental characteristics would wear on a mother’s ability to remain responsive, we found children’s current temperamental traits across contexts, as opposed to prior characteristics, to predict mothers’ behaviors. This finding also may point to a relative lack of stability in toddlers’ temperament in the second and third years of life. Indeed, past work examining the stability of temperament implies a considerable amount of change is still occurring in children’s temperament in the early years, with correlations generally ranging from .20 to .40 (e.g., Slabach et al., 1991). Across-time correlations obtained using our temperament construct (.35) are in line with previous work and further suggest the potential mutability of temperament during this time.

In regard to the lack of relation between regulated temperament and maternal control at T1, changes in temperament may prompt changes in the type of strategy mothers employ when dealing with their toddlers. Toddlers are more verbal at 30 months of age, and mothers may find that responding with matter-of-fact instructions and firmer tones of voice in response to lower levels of regulated temperament elicits greater cooperation than other methods of control at this age. Had we examined other methods of control (e.g., more nonverbal methods), we may have stronger relations at this young age (i.e., 18 months).

Many researchers have suggested that environmental factors and child characteristics may interact to predict parenting behavior (e.g., Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003; Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Rutter, 1990). This investigation adds credence to this hypothesis by demonstrating that toddlers’ lower levels of regulated temperament exacerbate the relation between cumulative demographic risk and maternal control. Mothers who have higher risk levels may experience greater stress and in turn have fewer resources to respond to their toddlers’ challenging behaviors with more gentle control strategies. This result is in line with Scarr and McCartney’s (1983) idea of evocative interactions; toddlers’ temperamental dispositions may evoke certain responses from the environment. Under conditions of greater risk, a more difficult (unregulated) temperament would be expected to relate to lower quality parenting, and some researchers have found that temperamentally difficult children are more likely to be exposed to negative maternal parenting behaviors (e.g., Jenkins et al., 2003; Rutter & Quinton, 1984). Moreover, when mothers’ negative behaviors are accompanied by demographic stress, difficult children have been found to be even more susceptible to negative parenting behaviors (e.g., Jenkins et al., 2003; Rutter & Quinton, 1984).

There were a number of limitations in this study that should be taken into account. In all regression analyses, the proportion of variance explained was small, most often accounting for between 4% and 8% of the variance; thus, these findings should be viewed with caution. Although we observed parenting during two tasks of varying structure, our observation of parenting behavior was brief and limited to a laboratory setting and may not have completely captured the possible range of parenting behaviors. Some of the hypotheses were supported using these parenting measures; however, the lack of relations longitudinally and the inconsistency across ages may have been due to the limitations of the parenting measures. Because the parent–child interactions were viewed in a laboratory setting, our ability to generalize these findings across contexts is limited. The sample was mainly White, which does not allow us to extend these findings to other racial and ethnic groups. Moreover, because parents were required to be adults and to read English fluently, our recruitment procedures biased our sample to be at a lower risk. Additionally, this investigation only examined maternal responsivity and control; it remains possible that other parenting behaviors also may be important to consider. Finally, given the correlational nature of this study, there is still much to learn about the potential bidirectional relations between children’s temperament and mothers’ parenting behaviors.

In conclusion, findings of this study suggest that cumulative demographic risk is an important factor in predicting maternal parenting behavior. Temperament also was found to predict maternal parenting behaviors. In addition, our findings suggest that toddlers’ regulated temperament may be related to variation in parenting behavior in families with more cumulative demographic risk. Future work calling for a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the relations between risk and parenting is needed, such as maternal mental health and stress. In addition, researchers should pay attention to the chronicity of risk, timing of risk exposure, or trajectories of risk in future work. Moreover, other child-related risk factors, such as low birth weight, prematurity, or specific developmental delays should be taken into account to understand the relations of family risk to parenting.

TABLE 1.

Percentages of Risk Factors at T1 and T2

| Variables | Category | T1 (N = 245) | T2 (N = 216) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | White/Non-Hispanic | 74% | 74% |

| Other | 26% | 26% | |

| Household status | One-parent | 7.8% | 10.5% |

| Two-parent | 92.2% | 89.5% | |

| Income | Less than $30,000 | 21% | 21.4% |

| More than $30,000 | 79% | 78.6% | |

| Mother education | Less than high school | 5% | 4.3% |

| High school or more | 95% | 96.7% | |

| Number of siblings | Two or fewer | 95% | 96.4% |

| Three or more | 3% | 3.6% | |

| Mother occupation | Unskilled/manual | 6.4% | 8.8% |

| Skilled/professional | 93.6% | 91.2% | |

| Mother age at child birth | 19 or younger | 7% | 7% |

| 20 or older | 93% | 93% |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Cynthia L. Smith is now at the Department of Human Development, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH060838) awarded to Nancy Eisenberg and Tracy L. Spinrad. We express our appreciation to the parents and toddlers who participated in the study and to the many research assistants who contributed to this project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contributor Information

Tierney K. Popp, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University

Tracy L. Spinrad, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University

Cynthia L. Smith, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University

REFERENCES

- Aiken LS, West SG. Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barocas R, Seifer R, Sameroff AJ, Andrews TA, Croft RT, Ostrow E. Social and interpersonal determinants of developmental risk. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:479–488. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Manual for the Bayley Scales of Infant Development. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Hsieh K, Crnic K. Mothering, fathering, and infant negativity as antecedents of boys’ externalizing problems and inhibition at age 3 years: Differential susceptibility to rearing experience? Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:301–319. doi: 10.1017/s095457949800162x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Brady-Smith C, Brooks-Gunn J. Links between childbearing age and observed maternal behaviors with 14-month-olds in the early head start research project. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2002;23:104–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH. HOME measurement of maternal responsiveness. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Maternal responsiveness: Characteristics and consequences. New directions for child development. No. 43. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1989. pp. 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein P, Clauson J, Stoll MF, Abrams CL. Fathering after separation or divorce: Factors predicting children’s adjustment. Family Relations. 1993;42:268–276. [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Grusec JE. Socialization processes. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, personality development. 6th ed. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Hungerford A, Dedmon SE. Mothers’ interactions with temperamentally frustrated infants. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2004;25:219–239. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Johnson MC. Toddler regulation of distress to frustrating events: Temperamental and maternal correlates. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21:379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Mother–infant interaction as a function of maternal ratings of temperament. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 1979;10:67–76. doi: 10.1007/BF01433498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Pierce EW, Moore G, Marakovitz S, Newby K. Boys’ externalizing problems at elementary school age: Pathways from early behavior problems, maternal control, and family stress. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:701–719. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Watt NF, West SG, Hawkins D, Asarnow JR, Markman HJ, et al. The science of prevention. American Psychologist. 1993;48:1013–1022. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, Leerkes E. Infant negative emotionality, caregiving, and family relationships. In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2003. pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SB, Smith P. Antecedents of mother–infant interaction and infant irritability in the first three months of life. Infant Behavior and Development. 1982;5:105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Development. 1994;65:649–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Losoya SH, Valiente C, et al. The relations of problem behavior status to children’s negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: Concurrent relations and prediction of change. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:193–211. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Cumberland A, Shepard SA, et al. The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency and adjustment. Child Development. 2004;75:25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Maxwell LE, Hart B. Parental language and verbal responsiveness to children in crowded homes. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1020–1023. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.4.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish M. Attachment in low-SES rural Appalachian infants: Contextual, infant, and maternal interaction risk and protective factors. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:641–664. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS. Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:313–333. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Sameroff AJ, Cole R. Academic growth curve trajectories from 1st grade to 12th grade: Effects of multiple social risk factors and preschool child factors. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:777–790. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Sameroff AJ, Eccles JS. The academic achievement of African American students during early adolescence: An examination of multiple risk, promotive, and protective factors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:367–399. doi: 10.1023/A:1015389103911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Sameroff AJ, Eccles JS. The academic achievement of African American students during early adolescence: An examination of multiple risk, promotive, and protective factors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:367–400. doi: 10.1023/A:1015389103911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnish JD, Dodge KA, Valente E, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Mother–child interaction quality as a partial mediator of the roles of maternal depressive symptomatology and socioeconomic status in the development of child behavior problems. Child Development. 1995;66:739–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashima PY, Amato PR. Poverty, social support, and parental behavior. Child Development. 1994;65:394–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson HA, Wachs TD. Temperament theory and the study of cognition–emotion interactions across development. Developmental Review. 2007;27:396–427. [Google Scholar]

- Hinde RA. Temperament as an intervening variable. In: Kohnstamm GA, Bates JE, Rothbart MK, editors. Temperament in childhood. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1989. pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SR, Burchinal MR, Roberts JE, Zeisel S, Neebe EC. Social and family risk factors for infant development at one year: An application of the cumulative risk model. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1998;19:85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JM, Rabash J, O’Connor TG. The role of shared family context in differential parenting. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:99–113. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov PK, Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. Does neighborhood and family poverty affect mothers’ parenting, mental health, and social support? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:441–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N, Penney SJ, Boldt LJ. Parental personality as an inner resource that moderates the impact of ecological adversity on parenting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:136–150. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Forman DR, Coy KC. Implications of the mother–child relationship in infancy socialization in the second year of life. Infant Behavior and Development. 1999;22:249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Young children’s progression to self-regulation. In: Bullock M, editor. The development of intentional action: Cognitive, motivational, and interactive processes. Contributions to human development. Vol. 22. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 1991. pp. 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lee BJ, Goerge RM. Poverty, early childbearing, and child maltreatment: A multinomial analysis. Children and Youth Services Review. 1999;21:755–780. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CL, Bates JE. Mother–child interaction at age two years and perceived difficult temperament. Child Development. 1985;56:1314–1325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1985.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Scaramella LV, Fagot BI. Infant temperament, pleasure in parenting, and marital happiness in adoptive families. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:545–558. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw F, Brooks-Gunn J. Cumulative familial risks and low-birthweight children’s cognitive and behavioral development. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:360–372. [Google Scholar]

- Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J, Kohen DE. Family processes as pathways from income to young children’s development. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:719–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masur EF, Turner M. Stability and consistency in mothers’ and infants’ interactive styles. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2001;47:100–120. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, Shanahan MJ. Poverty, parenting, and children’s mental health. American Sociological Review. 1993;58:351–366. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network Duration and developmental timing of poverty and children’s cognitive and social development from birth through third grade. Child Development. 2005;76:795–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Bates JE, Bayles K. Early antecedents of child impulsivity: The role of parent–child interaction, cognitive competence, and temperament. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:317–334. doi: 10.1007/BF00916568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens EB, Shaw DS, Vondra JI. Relations between infant irritability and maternal responsiveness in low-income families. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21:761–778. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Buriel R. Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, personality development. 6th ed. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 429–504. [Google Scholar]

- Pedlow R, Sanson A, Prior M, Oberklaid F. Stability of maternally reported temperament from infancy to 8 years. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:998–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster EM, Jones D, The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Parenting in context: Impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and danger on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:941–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK. Measurement of fine-grained aspects of toddler temperament: The Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development. 2006;29:386–401. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Sanson AV, Rothbart MK. Child temperament and parenting. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2002. pp. 255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. The Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire. 2000 Retrieved January 27, 2002, from University of Oregon, Mary Rothbart’s Temperament Laboratory Web site, http://www. uoregon.edu/~maryroth. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, personality development. 5th ed. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 619–700. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. In: Rolf J, Masten AS, Cichetti D, Nuechterlein KH, Weintraub S, editors. Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 181–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Quinton D. Parental psychiatric disorder: Effects on children. Psychological Medicine. 1984;14:853–880. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700019838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Baldwin A, Baldwin C. Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: The influence of social and family risk factors. Child Development. 1993;64:80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Barocas R, Zax M, Greenspan S. Intelligence quotient scores of 4-year-old children: Social-environmental risk factors. Pediatrics. 1987;79:343–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Hemphill SA, Smart D. Connections between temperament and social development: A review. Social Development. 2004;13:142–170. [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, McCartney K. How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype–environment effects. Child Development. 1983;54:424–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1983.tb03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifer R, Sameroff AJ, Barrett LC, Krafchuk E. Infant temperament measured by multiple observations and mother report. Child Development. 1994;65:1478–1490. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifer R, Schiller M, Sameroff AJ, Resnick S, Riordan K. Attachment, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament during the first year of life. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Slabach EH, Morrow J, Wachs TD. Questionnaire measurement of infant and child temperament: Current status and future directions. In: Strelau J, Angleitner A, editors. Explorations in temperament: International perspectives on theory and measurement. New York: Plenum; 1991. pp. 205–234. [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Gaertner B, Popp T, Smith CL, Kupfer A, et al. Relations of maternal socialization and toddlers’ effortful control to children’s adjustment and social competence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1170–1186. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL, McMahon RJ, Lengua LJ, The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Parenting practices and child disruptive behavior problems in early elementary school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:17–29. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bornstein MH, Baumwell L. Maternal responsiveness and children’s achievement of language milestones. Child Development. 2001;72:748–767. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Boom DC, Hoeksma JB. The effect of infant irritability on mother–infant interaction: A growth-curve analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:581–590. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM. Parent, child, and contextual predictors of childhood physical punishment. Infant and Child Development. 2002;11:213–236. [Google Scholar]