Abstract

Prison nursery programs allow departments of correction to positively intervene in the lives of both incarcerated mothers and their infant children. The number of prison nurseries in the United States has risen dramatically in the past decade, yet there remains a significant gap between predominant correctional policy in this area and what is known about parenting and infant development. Using Kingdon’s streams metaphor, this article examines the recent convergence of problem, policy, and political events related to incarcerated women with infant children and argues that this has created a window of opportunity for development of prison nursery programs. Aday’s policy analysis criteria are also used to analyze available evidence regarding the effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of prison nursery programs as policy alternatives for incarcerated women with infant children.

Keywords: attachment, children of prisoners, criminal justice policy, female inmates, incarcerated mothers, infants, parenting, prison nursery

Prison nursery programs allow incarcerated women to care for their infant children within a correctional facility, providing a unique, bi-generational intervention opportunity for departments of correction (DOC). A prison nursery is a living arrangement located within a correctional facility in which an imprisoned woman and her infant can consistently co-reside with the mother as primary caregiver during some or all of the mother’s sentence. Prison nurseries have the potential to promote rehabilitation of incarcerated mothers, while also providing the physical closeness and supportive environment necessary for the development of secure attachment between mothers and their infants. Secure attachment establishes a foundation for positive child development and may confer long-term resilience to this vulnerable population of children (Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005).

This article explores historically shifting policy issues related to US prison nurseries and suggests reasons for the current upsurge of interest in these programs. Kingdon’s streams metaphor (Kingdon, 1995; Birkland, 2007) is used to argue that the convergence of problem, policy, and political events related to incarcerated women with infant children has placed prison nurseries on the agenda, creating a window of opportunity for renewed development of these programs in the US. Aday’s (2005) criteria are used to analyze available evidence regarding the effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of prison nursery programs as policy alternatives for incarcerated women with infant children. Gaps are described between the established evidence bases for parenting and infant development and current policy regarding parenting programs for this population of women and infants and recommendations are made for future research and practice.

BACKGROUND

The number of women incarcerated in state prisons in the United States (US) has dramatically increased in the past 20 years, and 70% of these women are the mothers of minor children, as of the last Bureau of Justice estimates (Mumola, 2000; Sabol, Minton, & Harrison, 2007). Incarcerated women who are pregnant or have recently given birth present a particular challenge to the correctional system. Should these women be treated any differently than other incarcerated women? Who should provide for their infants? Should the system separate an incarcerated mother from her infant, allow her to care for her infant within a correctional institution, or release her into the community to care for her infant there? Allowing women to parent their children within correctional facilities in the US may be “one of the most controversial debates surrounding the imprisonment of women” (Belknap, 2007, p. 203). Yet policies allowing the incarcerated mother to live with her infant persist as the norm internationally and were a common way of dealing with this group of prisoners in the US from the beginning to the middle of the 20th Century (Shepard & Zemans, 1950; Kauffman, 2006). The early history of US prison nurseries and accepted international perspectives are often forgotten in recent publications and media coverage, where co-residence is portrayed as a new and radical phenomenon (Ghose, 2002; Porterfield, 2007; Willing, 1999; Zachariah, 2006).

A national survey in 1948 indicated that state correctional facilities in the US often opted to return pregnant inmates to local jails or transfer them to a community co-residence alternative site for the duration of their pregnancy and a portion of time postpartum rather than incarcerate newly delivered women without their infants (Shepard & Zemans, 1950). Thirteen states at the time of this survey had statutory provisions allowing incarcerated mothers to keep their children in prison with them. By the 1970s, many states had repealed legislation supportive of prison nurseries (Radosh, 1988). Concerns related to security, nursery program management, liability, the potential adverse effects of the prison on child health and development, and the difficulty of eventual separation of mother and child in women with long sentences was cited as the primary reasons for program closure (Brodie, 1982; Radosh, 1988). By the 1980s prison nurseries were lauded as the best theoretical solution to the problem of incarcerating women with infants but were deemed unrealistically cumbersome for already overburdened US prison systems (Baunach, 1986). In the last multi-national survey published, the Alliance of Non-Governmental Organizations on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice queried 70 nations in 1987 and found that only Suriname, Liberia, the Bahamas, and the US routinely separated imprisoned mothers from their infants (Kauffman, 2006).

Incarceration rates for women are predicted to remain at a stable high, if not continue to increase (Public Safety Performance Project, 2007). At the same time federal and state lawmakers are providing bipartisan support for services to incarcerated and recently released populations, particularly those programs designed to decrease recidivism (Eckholm, 2008; Suellentrop, 2006). State correctional systems are increasingly searching for gender-responsive programs for female inmates. In this milieu, nursery programs in particular are on the rise. In a 1998 survey of parenting programs in 40 women’s prisons in the US, three states—New York, Nebraska, and South Dakota—reported a currently functioning prison nursery program (Pollock, 2002). By 2001, a survey by the National Institute of Corrections (NIC) revealed seven states with nursery programs, with the addition of Massachusetts, Montana, Ohio, and Washington. As of August 2008, eight states provide prison nursery programs in at least one of their women’s facilities: California, Indiana, Illinois, Nebraska, New York, Ohio, South Dakota, and Washington State (Carlson, 2001; de Sa, 2006; Kauffman, 2006; Rowland, & Watts, 2007; South Dakota Department of Corrections, n.d.; Stern, 2004), and West Virginia has approved legislation to implement a future program (Porterfield, 2007) It is part of the US historical pattern for increases in the total numbers of prison nurseries to not be cumulative in a linear way but achieved by closure of some facilities while new programs are added elsewhere. Only New York State has a long history of maintaining a prison nursery in one location, established in 1901, although the structure of the nursery and of the prison facility itself have changed over time.

MERGING OF PROBLEM, POLICY, AND POLITICS

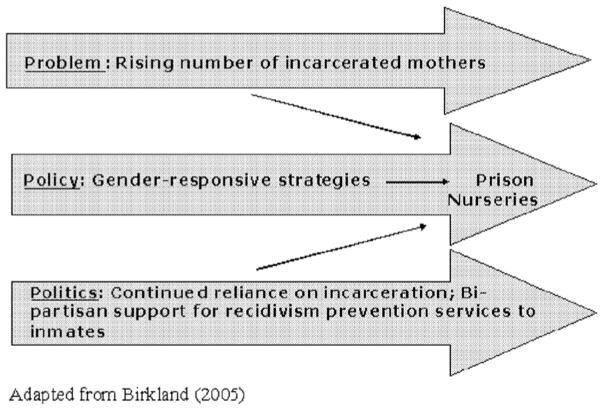

Kingdon’s three streams metaphor describes the process of how issues become part of the policy-making agenda (Kingdon, 1995). Kingdon argues that issues reach agenda status when problem, policy, and political streams converge at the same point in time, creating a window of opportunity for policy change. The problem stream contains the attributes of the problem, and the process of persuading decision makers to perceive a certain problem as serious, to pay attention to it over others, and to believe that the problem can be solved or lessened by alternatives available in the policy stream at the time. Focusing events often bring certain problems to the public consciousness. The policy stream involves all the potential solutions for the problem that are available to decision makers. Finally, the politics stream encompasses the political climate and public opinion regarding the problem and the potential policy solutions at any given time. Figure 1 provides an illustration of Kingdom’s three steams metaphor adapted to explain policy changes supportive of prison nurseries.

FIGURE 1.

Kingdon’s three streams metaphor and the window of opportunity for prison nursery programs.

The Problem of Maternal Incarceration

Advocacy groups for vulnerable children, such as the Child Welfare League of America and the National Council on Crime and Delinquency, were the first to widely discuss the myriad problems related to incarcerating mothers (McGowan & Blumenthal, 1978). Exploration of these problems in lay or professional literature was minimal outside of advocacy circles until incarceration rates for women rose sharply in the 1980s and 1990s as the result of mandated prison sentences for drug crimes and the increased willingness to incarcerate women for non-violent crimes. Rising maternal incarceration rates, while not providing an acute focusing event, brought media attention to this problem. Articles in local and national papers, television specials, and documentaries have predominately portrayed this group sympathetically, describing the mothers as victims of violence during their own childhoods, and the separated children as sharing the punishment for their mother’s crimes (de Sa, 2006; Drummond, 2000; Dobbs, 2007; Ghose, 2002; Lombardi, 2004; Beaudry, 2008; Wertheimer, 2005). Additionally, the cited media reports highlight the rehabilitative potential of parenting programs given in women’s correctional institutions.

Prison Nursery Programs as Viable Policy

Feminist criminologists have led the call for increased gender-responsiveness in correctional facilities, and after years of focusing on men, the NIC published a report in 2003 on gender-responsive interventions for incarcerated women (Bloom, Owen, & Covington, 2003). The report highlighted the unique effects of poverty, trauma, and substance abuse on this group of women, and acknowledged that the majority of incarcerated women are mothers, that these mothers overwhelmingly desire to maintain ties with their children, and that they face distinct challenges with successful parenting. Parenting programs aimed at helping women overcome these barriers are now considered a critical gender-responsive strategy in correctional institutions housing female inmates. Prison nursery programs and community-based co-residence facilities are the primary intervention strategies currently implemented specifically for women under criminal justice supervision and their infant children. Openings announced since 2006 for the four most recent prison nurseries have been presented positively in local news media and on DOC public information sites, suggesting an upsurge of both public and internal criminal justice system support (Bach, 2006; Drummond, 2000; Ghose, 2002; Haddock, 2006; Illinois Department of Corrections, 2008; Indiana Department of Corrections, 2008). This is consistent with new bipartisan legislative support for general population rehabilitation and reentry programs (Suellentrop, 2006).

The Current Politics of Services to Incarcerated Populations

Incarceration continues to be the preferred method of punishment in the US, even for non-violent offenders (Public Safety Performance Project, 2007). This has prevented community-based approaches from proliferating. In fact, multiple federally funded community-based co-residence alternatives were closed a decade ago because of “truth in sentencing” laws enacted by state lawmakers to force incarcerated persons to serve their full sentences (Barkauskas, Low, & Pimlott, 2002). Additionally, California, whose extensive community program was lauded by advocates, opened its first prison nursery program in 2006 (Bach, 2006).

Despite the continued reliance on incarceration, there is evidence that the guiding paradigm in correctional policy is again turning toward rehabilitation, and unprecedented bi-partisan support currently exists for rehabilitative services for inmates, especially those, like prison nursery programs, that decrease recidivism (Cullen, 2007; Eckholm, 2008; Suellentrop, 2006). The increased focus on rehabilitation through service provision to offenders brings the politics stream in alignment with the problem and policy streams, opening the window of opportunity for prison nursery programs.

DO POLICIES SUPPORTING PRISON NURSERIES RESULT IN EFFECTIVENESS, EFFICIENCY AND EQUITY?

Effectiveness, efficiency, and equity have been widely used policy criteria that can be applied to analyze available evidence related to US prison nurseries (Aday, 2005). The effectiveness criterion determines the magnitude of evidence supporting positive outcomes related to a policy. The efficiency criterion provides a guide for the assessment of the cost of a policy in relation to purported benefits and available resources. Finally, the equity criterion allows for the examination of whether a policy provides just access to a service.

Effectiveness

Decreased recidivism after release from a nursery program is currently the positive outcome with the most empirical support. One-third of women who delivered while incarcerated in the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women in the four years before the inauguration of their nursery returned to the facility for a new crime within three years of release, whereas only 9% of nursery participants in the first five years of their program were recidivate (Carlson, 2001). New York and Washington State reported approximately 50% lower three-year recidivism rates (13% vs. 26% in New York and 15% vs. 38% in Washington) in women who had participated in the nursery when compared to women released from the general prison population (Division of Program Planning, Research, & Evaluation, 2002; Rowland & Watts, 2007). Women participating in prison nurseries are screened prior to acceptance by type of crime, prior parenting outcomes, and current prison discipline record, making direct comparison to women in the general population somewhat specious; however, the magnitude of these results is promising.

Decreased maternal recidivism is an undoubtedly positive outcome for children as well as their mothers. Data regarding child-specific outcomes after participation in a nursery program are also critical endpoints but have rarely been collected. The UK Home Office, the equivalent of the US Department of Justice, commissioned a study in the mid-1980s to evaluate the development of infants cared for by their mothers in a prison nursery program (Catan, 1992). Recruitment and data collection took place between 1986 and 1988. Seventy-four children raised in two nurseries for a mean length of 13 weeks were compared with 33 control children, two-thirds of whom were cared for by family members and the remaining in foster care. The author reported the two groups had comparable development at baseline; however, progressive developmental decline in motor and cognitive scores was found for all nursery infants after admission to the unit, with the difference in Griffith Mental Development Scale scores reaching statistical significance after four months on the unit. Poor unit design, staffing and protocols were blamed by Catan for on-unit developmental delays. Writing in the British Medical Journal, Dillner (1992) corroborated Catan’s description of an environment where children’s movement was severely restricted, and infants were left strapped in prams or chairs for hours. Catan concluded that her findings confirmed the need to give mothers the option to parent their infants while incarcerated, and she advised greater attention to creating a child-friendly and stimulating environment. There is evidence that these recommendations have been implemented in the UK, but no further evaluation research has been reported (Black, Payne, Lansdown, & Gregoire, 2004; Her Majesty’s Prison Service, 2007).

Current US nursery programs differ greatly from the description provided by Catan (1992) in her landmark UK study. Most US nurseries are segregated away from other prison housing and are renovated specifically to house children. Programs are staffed by civilians in addition to correction officers and focus on developing the relationship between incarcerated mothers and their infants, promoting child development, and providing the mother with parenting and life skills education (Carlson, 2001, Fearn & Parker, 2004; Kauffman, 2006). In fact, the Nebraska, Ohio, and Washington nurseries grew from existing parenting education programs within the facilities (Kauffman, 2006). Public-private partnerships are used by the majority of nurseries to defray cost but also provide the advantage that external specialists and volunteers can help ensure that services meet community standards. Additionally, mothers participating in nursery programs in California, Indiana, New York, Ohio, South Dakota, and Washington State are mandated to participate in parenting education in order to remain in the program (Bach, 2006; Fearn & Parker, 2004; Indiana Department of Corrections, 2008; Prison nursery program, 2001; South Dakota Department of Corrections, n.d.).

Research assessing US outcomes other than recidivism is nascent. Subjective responses from small groups of imprisoned women accepted into prison nurseries in two states and an anecdotal summary of an unpublished national survey were all that was available until the current completion of a longitudinal, multi-measure, prospective study of prison nursery co-residents in New York during confinement and the first reentry year by an independent NIH-funded investigator not affiliated with the DOC system (Byrne, 2005; Byrne, 2008).

Descriptive reports of limited interviews in two states suggest that mothers participating in nursery programs in the US feel positively about them while corrections personnel are ambivalent. Gabel and Girard (1995) assessed the perceptions of a small convenience sample of mothers and staff in the two prison nurseries in New York. Mothers (n = 26) reported that the advantages to the cohabitation program included: improved bonding with their infants, development of parenting skills, infant services and supplies, opportunities for education, better conditions of confinement, drug education and treatment, help from other inmates, and self-respect. Reported disadvantages included: crowded conditions andnegative interaction with corrections officers and nursery staff. Mothers expressed strain related to parenting in a demanding environment in which they felt basic care giving, like feeding their infant, was tightly controlled. Staff perceptions varied, with the superintendent, psychologist, and nursery manager reporting positive perceptions, and a nurse and correction officers reporting mixed perceptions. Staff provided informal observations of maternal and child interaction behavior which they thought “suggested that strong, healthy attachment patterns were operating between mothers and infants” (Gabel & Girard, p. 253), but attachment was not formally measured.

Carlson (2001) surveyed 43 women in Nebraska’s nursery and 95% stated that they had a stronger bond with their child as a result of the program, 95% stated that if given the same choice they would enter the program again, and all participants stated that other states should have a similar program. However of this sample, only 57% retained custody of their children post release, suggesting that objective indicators such as child development, maternal-child relationship, maternal mental health, parenting competence, and recidivism may be more sensitive evaluation criteria than maternal perception of a nursery program.

Johnston (2003) reported completing a national study of prison nursery programs that revealed “no negative effects of the locked correctional environment on infants” (p. 142). The methodology, including sampling, enrollment, data collection, measures, and statistical analyses, used to reach these conclusions was not described, nor were results provided. Additionally the author did not report on follow-up after release.

Byrne completed her longitudinal study in 2008 following 100 continuously enrolled mother-baby dyads throughout their New York nursery stay and retaining 76 pairs throughout the first reentry year (Byrne, Goshin, & Joestl, in press). Multiple and repeated measures of maternal characteristics and child outcomes were made using established psychometrically validated instruments. Mothers’ internal representation of attachment to their own parent figures, measured by the Adult Attachment Interview and compared to normative samples, identified disproportionately large numbers of women who were themselves insecurely attached, lacked autonomy and had unresolved trauma, characteristics that would make it unlikely they could transmit secure attachment to their infants (Hesse, 1999). Nevertheless, following intervention of the prison nursery’s required parenting education programs enhanced by the research team’s weekly Nurse Practitioner visits the proportion of infants coded as securely attached by the classic Strange Situation Procedure (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978) vastly exceeded theoretical expectations. Infants co-residing 12 months in the nursery comprised a larger proportion of secure attachment than reported for low-risk community samples and infants released early in infancy and tested following the first birthday in the community approached the normative proportions for secure attachment (Byrne, Goshin, & Joestl, in press). Infants also reached developmental goals as measured by the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley, 1993) every three months during the prison stay and continued to do so post release as measured directly by the Bayley Scales or through care-giver report on the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (Bricker & Squires, 1999).

Efficiency

Limited published information is available regarding what state DOCs spend to operate prison nurseries. A report by the Idaho Office for Performance Evaluations (2003) states that the New York and Ohio DOCs both spent approximately $90,000 per year in 2002 to operate nursery programs caring for approximately 20 children (Office of Performance Evaluations, 2003). A more recent article in an Ohio newspaper reported that each child in the Ohio program costs the state $4.65 per day (Zachariah, 2006). In contrast, the prison nursery in Washington State has not increased cost to the institution, instead using social service money received for each child to pay for baby supplies, staffing, developmental support, and health care services through partnerships with community organizations, such as the local children’s hospital and Early Head Start provider (Rowland & Watts, 2007). The reduction in recidivism described above could also greatly defray the prison’s cost of nursery programs.

Public funding provides the bulk of the economic support for this population of children of incarcerated parents whether inside or outside of prison nursery programs. However, the funding for children cared for in the community does not come from the state DOC budget. Children of incarcerated mothers are most often cared for by their maternal grandmothers, who predominately live in poverty and receive public assistance in order to provide for them (Hanlon, Carswell, & Rose, 2006; Mumola, 2001; Poehlmann, 2005a). Additionally, approximately 10% of the children of incarcerated mothers are in the custody of the child welfare system, as of the last federal estimates (Mumola, 2001). Maternal incarceration is associated with increased time in child welfare custody and decreased likelihood of reunification, thereby increasing cost to already over burdened state child welfare systems (Ehrensaft, Khashu, Ross, & Wamsley, 2003).

Why should state DOCs accept financial responsibility for the infants of female inmates when the facilities under their purview were designed to care for the inmates alone? To answer this question it is necessary to assess the maternal and child effects of participation in a prison nursery program and to assign a monetary value to the prevention of future adverse events. Answering this question is no small feat given the paucity of research in this area.

History of parental incarceration is strongly associated with adolescent delinquency, adult criminality, and mental health disorders (Farrington, Jolliffe, Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Kalb, 2001; Huebner & Gustafson, 2007; Murray, & Farrington, 2005). Byrne’s newly completed research cited above demonstrates that children raised in a prison nursery program exhibit measurable rates of secure attachment consistent with or exceeding population norms. This is in stark contrast to children raised in the community during maternal incarceration (Poehlmann, 2005b). Secure attachment to a primary caregiver in infancy is hypothesized by child developmentalists to be the mysterious mediator known as resilience because it predicts positive mental health outcomes through early adulthood in high risk samples of children (Sroufe et al., 2005). Improving rates of secure attachment in infants with incarcerated mothers has the great potential to promote healthy development in the child’s life and prevent the negative sequelae linked to maternal incarceration, thereby decreasing the systemic burden of providing services to this population.

Equity

How does the approximately 135 children that current US nurseries can potentially serve at any one point in time compare to the total number of children in need? The last federal estimates are now a decade old and provide child age breakdowns only for both mothers and fathers together, but they continue to provide the best information regarding the total number of US children affected by parental incarceration as well as their age spectrum (Mumola, 2000). At the time of the 1997 Surveys of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 65% of female state prison inmates reported a total of 126,100 minor children, with 2.1% of the children below one year of age (Mumola, 2000). In addition, 20.4% were between one and four years of age, so it can be grossly estimated that one-third of these or 6.8% were between one and two years old. This leaves approximately 9% of the children of incarcerated mothers below two years of age, or 11,349 total children in 1997. These estimates, even given the fact that they are rough and based on old data, highlight the stark contrast between the number of infants and toddlers in the US affected by maternal incarceration and those served by prison nurseries. Additionally, rates of incarceration for women have grown since 1997, so this number is now likely to be much higher. Finally, Mumola (2000) did not report the number of women who were pregnant at the time of the survey or the number of children born during their mother’s period of incarceration. Maruschak (2008) estimated that 4% of state prisoners were pregnant upon admission in 2004, though older estimates were considerably higher at 6–10% (Greenfeld & Snell, 1999; Pollock, 2002).

Access to nursery programs in the US is limited by the small number of states offering this intervention. The nine currently functioning nurseries only provide services to women in eight states. This does not include inmates in Texas, Florida, or Georgia, three of the states with the top five largest prisoner censuses (Sabol et al., 2007).

Strict eligibility criteria, which are set by each state, also limit access (Boudoris, 1996; Johnston, 1995). See Table 1 for eligibility criteria in each of the currently functioning US nurseries. The oldest statute to regulate a prison nursery in the US, New York State Corrections Statute §611 (Births to Inmates, 2006), has been used as a template in other programs, so eligibility criteria appear similar across states (Carlson, 2001). In practice some variability exists as exceptions can be made by wardens for any circumstances not specified in the law. Participation is generally limited to women who enter prison pregnant, were convicted of a non-violent crime, and were sentenced to a term of less than 18 to 24 months after the birth of their infant. Criteria for nature of crime and sentence length can be subject to corrections review on a case by case basis. Infants in states without eligibility stipulations related to sentence length are generally discharged at 18 to 24 months regardless of their mother’s anticipated length of stay. Additionally, women with histories of child maltreatment, which is common in this group, are specifically barred from applying for the nurseries in California, Nebraska, New York, and Ohio.

TABLE 1.

Overview of US Prison Nursery Programs

| State, facility | Inaugural year | Program name | Capacity | Maximum length of stay | Eligibility criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| California, California Institution for Women (Bach, 2006) | 2007 | Bonding Mothers and Babies Program | 20 dyads | 15 months | Child born during the mother’s incarceration. Expected release date no more than 18 months after birth of child. No prior convictions for child abuse. Good disciplinary record with no history of escape attempts. Mothers are mandated to participate in prenatal and parenting courses. |

| Indiana, Indiana Women’s Prison (Indiana DOC, 2008) | 2008 | Wee Ones Nursery | 10 dyads | Unknown | Child born during the mother’s incarceration. Expected release date no more than 18 months after birth of child. Mother incarcerated for non-violent offense. Mothers are mandated to participate in prenatal and parenting courses. |

| Illinois, Decatur Correctional Center (Illinois DOC, 2008) | Originally proposed as pilot from March 2007–February 2008. Continues to function as a pilot as of May 2008. | Moms and Babies Program | 5 dyads during pilot phase, goal of 20 children if program is continued | 24 months | State publications reference screening of mothers but do not currently provide specific eligibility criteria for this program. Expected release date no more than 24 months after birth of child. |

| Nebraska, Nebraska Correctional Center for Women (Carlson, 2001) | 1994 | Mother Offspring Life Development Program (MOLD) | 15 children | 12 months | Child born during the mother’s incarceration. Expected release date of no more than 18 months after the birth of the child. No “extensive history of violence” (Carlson, 2001, p. 84). No prior convictions for child abuse. Mother cannot be on segregated status. Mother must sign an agreement that she will be the child’s primary caregiver after release. |

| New York, Bedford Hills Correctional Facility (Births to inmates, 2006) | 1901 | Children’s Center Nursery Program | 25 children | 12 months. Children may stay up to the age of 18 months if their mother is going to be paroled by that date. | Determined on a case-by-case basis. Mothers with nursing infants below the age of 12 month who were born before their period of confinement can apply for the program. No prior convictions for child abuse. Unspecified medical screening for mother and child; mental health screening for mother. |

| New York, Taconic Correctional Facility (Births to inmates, 2006) | 1990 | Nursery Program | 5–15 children | 12 months. Children may stay up to the age of 18 months if their mother is going to be paroled by that date. | Determined on a case-by-case basis. Mothers with nursing infants below the age of 12 month who were born before their period of confinement can apply for the program. Mothers sentenced for a violent crime can apply for the program and are evaluated individually. No prior convictions for child abuse. Unspecified medical screening for mother and child; mental health screening for mother. |

| Ohio, Ohio Reformatory for Women (Prison nursery program, 2001) | 2001 | Achieving Baby Care Success | 20 dyads | 18 months | Child born during the mother’s incarceration. Expected incarceration of no more than 18 months. Never been convicted of a violent offense. No prior convictions for child abuse. Unspecified medical screening for mother and child; mental health screening for mother. Mothers are mandated to participate in prenatal and parenting courses. |

| South Dakota, South Dakota Women’s Prison (South Dakota DOC, n.d.) | Not reported | Mother-Infant Program | Not reported | 30 days | Child born during the mother’s incarceration. Mother incarcerated for non-violent offense. Mothers must complete a parenting course before being allowed to participate. |

| Washington, Washington Correctional Center for Women (Fearn, & Parker, 2004) | 1999 | Residential Parenting Program | 20 dyads | 24 months | Child born during the mother’s incarceration. Mothers must have a sentence of less than three years and be eligible for pre-release before the child is 18 months of age. Mothers must have minimum-security designation. Mothers must receive clearance from the Washington State Division of Child and Family Services. All mothers with a history of abuse or neglect receive additional screening. Mothers with a history of a sexual offense against a child are prohibited. Mother must be eligible for Early Head Start. Unspecified medical and mental health screening for mother. Mothers are mandated to participate in prenatal and parenting courses. |

Johnston (1995) argued that the use of child abuse history discriminates against minority mothers because child protective laws are disproportionately enforced, and that crime type should not be used as it often does not reflect a person’s actual crime. She further advocates that nurseries should accept any mother who intends to parent her child after release, regardless of her expected length of incarceration. Eligibility criteria for the Washington State program most closely resemble those advocated by Johnston, with the important exception that access is limited to incarcerated women with a minimum security classification. Beyond that limit, any inmate who plans to be the primary caregiver of her child after release can apply, even with a history of a violent offense and/or child maltreatment (Kauffman, 2006).

POLICY ALTERNATIVES TO PRISON NURSERIES

Over 80% of state DOCs do not offer a prison nursery program. While the recent upsurge of policy support could lead to the development of prison nurseries in these states, it is also important to acknowledge community-based alternative programs as a substitute for prison nurseries and to consider other policy possibilities for this population of predominately non-violent offenders. The number of such programs currently exceeds the availability of prison nurseries which suggests comparatively greater policy support. Advocates for community based programs as the preferred choice see prison nurseries as the beginning of a life of contact with the criminal justice system for the children of incarcerated parents. Acoca and Raeder (1999) argued that “a key question for policy makers in the twenty-first century will be whether or not to replicate the existing mother-baby program model in women’s correctional facilities across the nation or to provide higher quality, lower cost, community-based alternatives” (p. 139). They also describe community options as safer, less expensive, and in the best interest of the children (Acoca & Raeder, 1999).

To some, the concepts of correctional environment and positive child development are antithetical (de Sa, 2006; Jaffé, Pons, & Wicky, 1997). Others have expressed concerns that the children who spend early years in prison will grow to accept this as the normative setting (Drummond, 2000). Available evidence fails to endorse either of these viewpoints. Positive outcomes for prison nursery programs are beginning to be documented. Yet the advantages of community-based alternative sentencing programs should not be overlooked especially if our society moves away from incarceration as the preferred option for offending women with dependent children.

The relatively small number of infants who can be accepted into existing prison nurseries nationwide stands out in stark contrast to the mothering needs of the large numbers of older children left behind in the community in states with nursery programs and both infants and older children who experience maternal separation in states without such programs. There is new evidence that the separation of these children from their mothers precedes the arrest of their mothers by one to three years (LaLonde, 2006; Moses, 2006), but that fact only underscores the needs of both the children and their mothers. Community resources and links between community and prison programs will continue to be needed regardless of the direction of policy support trends for prison nurseries. Mobilization of community resources is crucial to early intervention and could alter the path to prison for adult women and the developmental trajectory for their community-residing children. Collaborations with prison programs would also bolster the effectiveness of prison nursery programs during and following incarceration.

Contact between incarcerated parents and their children is important, but strategies to tailor contact methods to the developmental level of children, including infants, have not been fully explored (Hairston, 2003). Extended contact is needed in order to enhance secure attachment, and maintaining contact with children during incarceration is challenging, even for the most committed mothers and alternate caregivers. A majority of parents in state prisons (62%) reported being held over 100 miles from their last place of residence, so telephone calls and mail are used most commonly by prison inmates to maintain contact with children (Mumola, 2000). Even when families are able to visit it may not be on a consistent basis, visiting hours are short, and mothers may be unable to touch their children (Hairston, 2003). Telephone service for incarcerated persons is notoriously expensive and the financial burden often falls to families (Urbina, 2004). If the significant barriers cited above are overcome, brief visitation, letters, and phone calls could hypothetically maintain an already existing attachment between a mother and child from the toddler period through adolescence. The effect of intermittent, limited contact on the creation of the initial secure attachment relationship with an infant child is questionable, however, and there is no theoretical or empirical evidence to support it.

Didactic educational programs are the most commonly offered parenting promotion intervention in state prisons whether they offer a prison nursery program, an enhanced visiting and contact program, or neither (Loper, & Tuerk, 2006). Upon analyzing the differences in content and length of parent education programs among the states, Pollock (2002) described the range as “extreme” (p. 142), from a few hours of discussion on general parenting issues to lengthy programs incorporating life skills and visitation components. Additionally, most programs do not adequately account for different parenting strategies needed at different developmental stages. Parenting an infant is much different than parenting an adolescent, and brief, generic parenting education programs are likely not sensitive to the mothers’ varying educational needs.

Short-term, proximal outcome measures, such as parenting knowledge and attitudes, have been used to evaluate prison-based educational programs. Evaluations have consistently shown positive effects in these areas immediately after the intervention (Moore & Clement, 1998; Showers, 1993; Surratt, 2003; Thompson & Harm, 2000). There is no evidence, however, that improvements are sustained into the reentry period, are directly related to parenting competence when the mother is reunited with her children, or that that they have any direct effects on the incarcerated mother’s children either before or after her release (Loper & Tuerk, 2006), that is, that there is a connection between improvement in knowledge and parenting attitudes and consequent changes in parenting behaviors. Parenting education programs may be important but inadequate by themselves to create changes in parenting practices and child development outcomes. Didactic programs fulfill the utilitarian goal of providing something to the widest group of mothers, but the complexity of this population necessitates more tailored interventions. Nowhere is this need more critical than in mothers with infants.

THE PRISON NURSERY ADVANTAGE AND ITS CHALLENGES

Measuring current correctional programming for parents and their children against the extensive cross-disciplinary theoretical and empirical knowledge base regarding the developmental needs of mothers and infants provides support for a prison nursery approach to the problem of incarcerated women with infant children. It is well established that the central aspects of human behavior are created in infancy through early primary care giving relationships (Bowlby, 1982). Within these relationships children develop models for how the larger world operates and learn how to react in relation to these models. As children grow, they continue to filter their experience through the models created during infancy. For this reason, the effects of positive or negative experiences occurring during infancy are powerful and long lasting, even in the face of drastic changes later in life. High-risk children with a history of secure attachment during infancy exhibit significantly fewer behavior problems during preschool, school age, and adolescence than their counterparts with insecure attachment (Solomon & George, 1999; Sroufe et al., 2005). Evidence that secure attachment actually does occur in US prison nursery settings provides a strong argument for their effectiveness.

Because attachment is directly linked to child development, attention to creating environments that support age appropriate development is an important part of prison nursery implementation versus simply housing the infants while their mothers serve their sentences. The oldest US nursery has a day care center and emphasizes developmentally stimulating materials in the infant sleeping and recreation areas. Three newer US nurseries grew from existing parenting education programs, and the majority mandate pre-natal and infant care education for women participating in them. Corrections officials overseeing these programs have sometimes contracted with community providers specializing in infant and toddler care and development. This civilian professional expertise may help to ensure that children are raised in accord with the highest community standards possible within correctional mandates.

When US state prison nursery programs are measured against widely used policy criteria there is evidence that these programs are effective for the women and child participants and are reasonably efficient, but provide access to a small number of those in need. Limited access is a constraint to the potential widespread effectiveness of this policy solution. Eligibility criteria for acceptance additionally limit access to existing prison nurseries and remain a major concern for prison officials, as they become responsible for outcomes of the convicted women charged to their custody and for the civilian infants who they permit to co-reside within their facilities. Once arrest and sentencing have taken place, the challenge of establishing and implementing criteria for acceptance of incarcerated women into existing prison nursery programs is a serious and unresolved issue for which corrections systems have little direction. Statutes provide minimal guidelines. With current public and policy interest in more access to prison nursery programs, it is critical to recognize that expansion would require adequate resources to ensure success. New statutes should include authorization for supportive resources and existing statutes may have to be amended to incorporate this prerequisite

The current conservative approach of admitting only low risk mothers may be unrealistic if departments wish to reach more women and children. A more extreme proposal that has not yet been considered is to create prison nurseries with a therapeutic nursery philosophy. This approach would require resources to supervise and guide even higher-risk mothers to more positive parenting practices in a non-punitive environment. The clash of such an approach with current criminal justice demands is obvious. There have not been even pilot programs in the US to test the feasibility of the therapeutic nursery approach within correctional facilities. The closest approximation may be a UK pilot to determine the feasibility of a psychoanalytically oriented intervention addressing early attachment relationships which was evaluated with 27 incarcerated women and their infants in one Mother and Baby Unit of Her Majesty’s Prison Service (Baradon, Fonagy, Bland, Lenard, & Sleed, 2008). The preliminary report indicates that if such pilot work is to produce a successful intervention within a criminal justice environment there needs to be buy-in and orientation by all involved, investment in the professional providers needed to conduct the intervention and to support mothering by high-risk populations while protecting the children involved, and attention to determining the factors that will permit mothers to safely engage in reflective modalities.

CONCLUSION

Timely convergence of problem awareness, policy evidence, and political acceptability appear to explain the current renewed development of prison nursery programs. Prison nursery programs are a creative, gender-responsive strategy with the potential to positively affect both incarcerated women and their infant children. The evidence linking prison nursery participation to large reductions in recidivism makes them politically viable. Lawmakers increasingly recognize the unique problems related to the growing numbers and cumulative needs of incarcerated mothers and their children and perceive this group as deserving of attention. Positive developmental outcomes for infants who co-resided with their mothers in a US prison nursery have only recently been documented and provide renewed incentive for co-residence while ameliorating one of the most common concerns. Until our society and its lawmakers reconsider the widespread use of incarceration, prison nurseries are a preferred intervention for policy makers wishing to provide a cohabitation intervention for the incarcerated mothers with infant children under their jurisdiction.

For this to be an effective strategy and not just another wave in the up and down historical trending for prison nurseries in the US, it is critical that prison nurseries be established and maintained with the resources that empirical evidence show are necessary to create positive intergenerational outcomes. Continued research is needed to document these outcomes, to test effective components of prison nursery programs, and to identify collaborative prison and community resources that result in desired results not only during prison co-residence but for the critical re-entry years.

Acknowledgments

Support is acknowledged from the National Institutes of Health award to Mary Woods Byrne, “Maternal and Child Outcomes of a Prison Nursery Program” (R01 NR007782, M. Byrne, P. I.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

References

- Acoca L, Raeder MS. Severing family ties: The plight of nonviolent female offenders and their children. Stanford Law Review. 1999;11:133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Aday LA. Analytic framework. In: Aday LA, editor. Reinventing public health: Policies and practices for a healthy nation. San Francisco: John Wiley & Son, Inc; 2005. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bach M. CDCR, legislators, advocates partner to benefit “Bonding Mothers with Babies” prison nursery program. California Department of Corrections Staff News. 2006 December 15; Retrieved May 28, 2008, from http://www.cdcr.ca.gov/About_CDCR/Staff_News/sn20061215.pdf.

- Baradon T, Fonagy P, Bland K, Lenard K, Sleed M. New beginnings – An experience-based programme addressing the attachment relationship between mothers and their babies in prisons. Journal of Child Psychotherapy. 2008;34:240–258. [Google Scholar]

- Barkauskas VH, Low LK, Pimlott S. Health outcomes of incarcerated pregnant women and their infants in a community-based program. Journal of Mid-wifery & Women’s Health. 2002;47:371–379. doi: 10.1016/S1526–9523(02)00279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baunach PJ. Mothers in prison. New Brunswick, NJ: Transition, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley scales of infant development manual. 2. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace and Co; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudry C. Daughters left behind [Television broadcast] Washington, DC: National Geographic Television; 2008. (Producer) [Google Scholar]

- Belknap J. The invisible woman: Gender, crime, & justice. 3. Belmont, CA: Thompson-Wadworth; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Birkland T. An introduction to the policy process. 2. Armonk, NY: Sharp, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Births to Inmates of Correctional Institutions and Care of Children of Inmates of Correctional Institutions. (2006) 22 N.Y.S. Corrections Code §611.

- Black D, Payne H, Lansdown R, Gregoire A. Archives of the Disabled Child. Vol. 89. 2004. Babies behind bars revisited; pp. 896–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B, Owen B, Covington S. Gender responsive strategies: Research, practice, and guiding principles for women offenders (NIC Publication No. 018017) Washington, DC: National Institute of Corrections; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Boudouris J. Parents in prison: Addressing the needs of families. Lanham, MD: American Correctional Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker D, Squires J. Ages and stages questionnaires manual. 2. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Co; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie DL. Babies behind bars: Should incarcerated mothers be allowed to keep their newborns with them in prison? University of Richmond Law Review. 1982;16:677–692. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne MW. Conducting research as a visiting scientist in a women’s prison. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2005;21:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M, Goshin L, Joestl S. Intergenerational attachment for infants raised in a prison nursery. Attachment and Human Development. doi: 10.1080/14616730903417011. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J. Prison nursery 2000: A five-year review of the prison nursery at the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2001;33:75–97. doi: 10.1300/J076v33n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catan L. Infants with mothers in prison. In: Shaw R, editor. Prisoner’s children: What are the issues? London: Routledge; 1992. pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen FT. Make rehabilitation corrections’ guiding paradigm. Criminology & Public Policy. 2007;6:717–728. [Google Scholar]

- de Sa K. Event to highlight first prison nursery in California. Oakland Tribune. 2006 November 18; Retrieved June 18, 2007, from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4176/is_20061118/ai_n16861580.

- Dillner L. Keeping babies in prison. British Medical Journal. 1992;304:932–933. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6832.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Division of Program Planning, Research, and Evaluation. Profile and three year follow-up of Bedford Hills and Taconic nursery participants: 1997 and 1998. Albany, NY: State of New York Department of Correctional Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs G. Behind bars: A family affair [Television broadcast] Dallas, TX: HDNET World Report; 2007. Retrieved October 25, 2007, from http://www.hd.net/transcript.html?air_master_id=A4584. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond T. Mothers in prison. Time Magazine. 2000 November 6; Retrieved June 18, 2007, from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,998404,00.html.

- Eckholm E. U.S. shifting prison focus to re-entry in society. The New York Times. 2008 April 8; Retrieved May 15, 2008, from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/08/washington/08reentry.html.

- Ehrensaft M, Khashu A, Ross T, Wamsley M. Patterns of criminal conviction and incarceration among mothers of children in foster care in New York City. New York: Vera Institute of Justice and New York City Administration for Children’s Services; 2003. Retrieved March 15, 2007, from http://www.vera.org/publication_pdf/210_408.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Jolliffe D, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Kalb LM. The concentration of offenders in families, and family criminality in the prediction of boys’ delinquency. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:579–596. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearn NE, Parker K. Washington State’s residential parenting program: An integrated public health, education, and social service resource for pregnant inmates and prison mothers. California Journal of Health Promotion. 2004;2(4):34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel K, Girard K. Long-term care nurseries in prisons: A descriptive study. In: Gabel K, Johnston D, editors. Children of incarcerated parents. New York: Lexington Books; 1995. pp. 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Ghose D. Nursery program aids jailed moms in four states. Stateline. 2002 Retrieved November 17, 2006, from http://www.stateline.org/live/ViewPage.action?siteNodeId=136&languageId=1&contentId=14972.

- Greenfeld LA, Snell TL. Women offenders (No. NCJ 175688). US Bureau of Justice Statistics. Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Haddock V. Babies behind bars. San Francisco Chronicle. 2006 May 14;:E1. Retrieved August 11, 2008 from http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2006/05/14/INGORIPSMN37.DTL.

- Hairston CF. Prisoners and their families: Parenting issues during incarceration. In: Travis J, Waul M, editors. Prisoners Once Removed. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2003. pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon TE, Carswell SB, Rose M. Research on the caretaking of children of incarcerated parents: Findings and their service delivery implications. Children and Youth Service Review. 2007;29:348–362. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Her Majesty’s Prison Service. The management of mother and baby units. 3. London: Author; 2007. Order No. 4801. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse E. The adult attachment interview: Historical and current perspectives. In: Cassidy J, Shaver P, editors. The handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications. London/New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 395–433. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner BM, Gustafson R. The effect of maternal incarceration on adult offspring involvement in the criminal justice system. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2007;35:283–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2007.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Department of Corrections. IDOC Celebrates the first anniversary of the Moms and Babies Program at Decatur Correctional Center. Springfield, IL: Author; 2008. May 19, Retrieved May 27, 2008, from http://www.idoc.state.il.us/subsections/news/default.shtml@#2008May19Decatur. [Google Scholar]

- Indiana Department of Corrections. Indiana Department of Correction announces opening of nursery program at Indiana Women’s Prison. Indianapolis, IN: Author; 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2008, from http://www.in.gov/idoc/files/WON_Media_Advisory.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffé PD, Pons F, Wicky HR. Children imprisoned with their mothers: Psychological implications. In: Redondo S, Carrido V, Perez J, Barberet R, editors. Advances in psychology and law: International contributions. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter; 1997. pp. 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D. Intervention. In: Gabel K, Johnston D, editors. Children of incarcerated parents. New York: Lexington Books; 1995. pp. 206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D. What works: Children of incarcerated offenders. In: Gadsden VL, editor. Heading home: Offender reintegration into the family. Lanham, MD: American Correctional Association; 2003. pp. 123–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman K. Prison nurseries: New beginnings and second chances. In: Immarigeon R, editor. Women and girls in the criminal justice system. Policy issues and practice strategies. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives and public policies. 2. New York: Harper Collins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- LaLonde RJ. Incarcerated mothers, their children, and the nexus with foster care. Paper presented at The National Institutes of Justice Conference 2006; Washington, DC. 2006. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi KS. Parenting behind bars. The New York Times. 2004 April 11; Retrieved October 15, 2007, from http://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/11/nyregion/parenting-behind-bars.html.

- Loper AB, Tuerk EH. Parenting programs for incarcerated parents: Current research and future directions. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2006;17:407–427. doi: 10.1177/0887403406292692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM. Medical problems of prisoners. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2008. Retrieved July 1, 2008, from http://www.ojp.gov/bjs/pub/html/mpp/mpp.htm#related. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan BG, Blumenthal KL. Why punish the children? Hackensack, NJ: National Council on Crime and Delinquency; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Moore AR, Clement MJ. Effects of parenting training for incarcerated mothers. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 1998;27:57–72. doi: 10.1300/J076v27n01_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moses M. Does parental incarceration increase a child’s risk for foster care placement? National Institutes of Justice Journal. 2006 November;255 Retrieved August 12, 2008, from http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij/journals/255/parental_incarceration.html.

- Mumola CJ. Incarcerated parents and their children (NCJ Publication No. 182335) Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Farrington DP. Parental imprisonment: Effect on boys’ antisocial behavior and delinquency throughout the life-course. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:1269–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469– 7610.2005.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Performance Evaluations. Programs for incarcerated mothers (Report 03–01) Boise, ID: Idaho State Legislature; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J. Children’s family environments and intellectual outcomes during maternal incarceration. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005a;67:1275–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1741–3737.2005.00216.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J. Representations of attachment relationships in children of incarcerated mothers. Child Development. 2005b;76:679–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1467–8624.2005.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock JM. Parenting programs in women’s prisons. Women & Criminal Justice. 2002;14(1):131–154. doi: 10.1300/J012v14n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porterfield M. W.Va.’s prison nursery program receives worldwide attention. Beckley Register-Herald. 2007 March 16; Retrieved January 28, 2008, from http://www.register-herald.com/local/local-story-075203408.html.

- Prison nursery program and infants born during confinement. (2001) Ohio Administrative Code §5120–9–57.

- Public Safety Performance Project. Pubic safety, public spending: Forecasting America’s prison population 2007–2011. Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trust; 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2008, from http://www.pewcenteronthestates.org/uploaded-Files/Public%20Safety%20Public%20SpendingFiles/Public%20Safety%20Public%20Spending.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Radosh P. Inmate mothers: Legislative solutions to a difficult problem. Crime and Justice. 1988;11:61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland M, Watts A. Washington State’s effort to the generational impact on crime. Corrections Today. 2007 Retrieved September 12, 2007, from http://www.aca.org/publications/pdf/Rowland_Watts_Aug07.pdf.

- Sabol WJ, Minton TD, Harrison PM. Prison and jail inmates at mid-year 2006 (NCJ Publication No. 217675) Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard D, Zemans ES. Prison babies: A study of some aspects of the care and treatment of pregnant inmates and their infants in training schools, reformatories, and prisons. Chicago: John Howard Association; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Showers J. Assessing and remedying parenting knowledge among women inmates. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 1993;20:35–46. doi: 10.1300/J076v20n01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J, George C, editors. Attachment disorganization. London: The Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- South Dakota Department of Corrections. Mother-infant programs. Pierre, SD: Author; nd. [Accessed May 22, 2008]. from http://doc.sd.gov/adult/facilities/wp/mip.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA, Collins WA. The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stern AH. Babies born to incarcerated mothers. New York: National Resource Center for Foster Care and Permanency Planning; 2004. Retrieved March 15, 2008, from http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/socwork/nrcfcpp/downloads/information_packets/babies_born_to_incarcerated_mothers.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Suellentrop C. The right has a jailhouse conversion. The New York Times. 2006 December 24; Retrieved January 10, 2007, from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/24/magazine/24GOP.t.html.

- Surratt HL. Parenting attitudes of drug-involved women inmates. The Prison Journal. 2003;83:206–220. doi: 10.1177/0032885503254482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PJ, Harm NJ. Parenting from prison: Helping children and mothers. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2000;23:61–81. doi: 10.1080/01460860050121402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina I. A phone venture: Calling all prisoners. The New York Times. 2004 September 5;:1. Section 10. [Google Scholar]

- Wertheimer L. Prenatal care behind bars [Radio broadcast] Washington, DC: National Public Radio; 2005. November 5, [Google Scholar]

- Willing R. Babies behind bars: Coddling cons or aiding them? USA Today. 1999 April 21;:15A. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah H. Nurseries’ success hard to measure. The Columbus Dispatch. 2006 October 16; [Electronic version]. Retrieved October 25, 2007, from http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-152813503.html.