Abstract

The authors analyzed the association between downward social mobility in subjective social status among 3,056 immigrants to the United States and the odds of a major depressive episode. Using data from the National Latino and Asian American Study (2002–2003), the authors examined downward mobility by comparing immigrants’ subjective social status in their country of origin with their subjective social status in the United States. The dependent variable was the occurrence of a past-year episode of major depression defined according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, criteria. Logistic regression models were used to control for a variety of sociodemographic and immigration-related characteristics. Analyses suggested that a loss of at least 3 steps in subjective social status is associated with increased risk of a depressive episode (odds ratio = 3.0, 95% confidence interval: 1.3, 6.6). Other factors independently associated with greater odds of depression included Latino ethnicity, female sex, having resided for a longer time in the United States, and being a US citizen. The findings suggest that immigrants who experience downward social mobility are at elevated risk of major depression. Policies or interventions focused only on immigrants of low social status may miss another group at risk: those who experience downward mobility from a higher social status.

Keywords: Asian Americans, depression, emigration and immigration, Hispanic Americans, mental disorders, mental health, social class, social mobility

Research on the mental health of immigrants to the United States has burgeoned recently. Recent studies comparing immigrants with persons born in the United States have shown lower risks of some mental health disorders among female Asian immigrants (1), male Caribbean immigrants (2), and female and male Latino immigrants (3) in comparison with their US-born counterparts of Latino or Asian descent. However, relatively few studies have examined variation in mental health outcomes among immigrants, despite the considerable heterogeneity in their characteristics. Some people experience little change or an improvement in their social and economic circumstances upon immigrating to the United States; however, others experience downward social mobility and may be at risk for depression or other mental health disorders as a result. Previous studies have suggested that downwardly mobile immigrants are at heightened risk of psychiatric disorders but have focused on specific groups, such as black Caribbean immigrants (2), Korean entrepreneurs (4), or Vietnamese refugees (5).

Recent studies drawing from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys have suggested that the risk of depression or other mental health problems may differ by immigrant group or by the circumstances related to migration. For example, studies conducted by Williams et al. (2) and Alegría et al. (3) found that third-generation immigrants have the highest risk for mental health problems, while recent immigrants are at relatively lower risk. However, another study also drawing from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys found that being native-born and having higher English language proficiency were negatively associated with mental health problems (1). These mixed results suggest that the immigration process may influence the mental health of specific groups of immigrants differently (6–13). Other factors that may differentiate mental health outcomes across immigrants are perceived incongruence between expectations before immigration and outcomes after immigration (14) or experiences of unemployment after arrival in the United States (15). These prior studies point to the potentially detrimental consequences of a loss of perceived social standing; however, to our knowledge, no studies have explicitly examined whether downward mobility in subjective social status (SSS) predicts depression among immigrants.

A long tradition in sociology has recognized that status inconsistency, or having different status rankings on different dimensions of social position, produces conflicting expectations and experiences that lead to frustration and uncertainty for the individual, increasing psychological stress (16, 17). Downward mobility represents the emergence of status inconsistency and could be linked to mental illness (18). More recent prospective studies have shown that downward mobility—indicated by such events as job demotion, job loss, or inter- or intragenerational loss of occupational prestige—can lead to negative mental health outcomes (including depression) in the population overall (19–21). Further, drastic life changes, such as losing one form of employment and then gaining another, potentially pose challenges to mental health and have been associated with a higher prevalence of depression and other mental health problems (22, 23).

In contrast to the extant studies of downward mobility and mental health that use samples including native-born persons and immigrants, in this study we focus on social mobility that occurred specifically as a result of immigration to the United States. We compare immigrants’ reports of what their social standing had been in their countries of origin with their perceived current standing in the United States. A decline in SSS, or “the individual's perception of his own position in the social hierarchy” (24, p. 569), may put immigrants at risk of depression. In prior studies, SSS has been linked to psychological outcomes (25) and self-rated health measures (26–28), even after controlling for more objective measures of socioeconomic position. Researchers have explained these findings by arguing that one's perception of low status relative to the status of others leads to stress and feelings of shame and mistrust. Stress and negative emotions could affect health directly through neuroendocrine pathways and indirectly via their influence on health outcomes and behaviors (29, 30). Recent research has begun to address the associations between changes in people's SSS and their health outcomes, but such research is still in its infancy (31).

In this study, we examined whether downward mobility in SSS among immigrants to the United States was associated with episodes of major depression. We used recently collected data on US immigrants from a nationally representative household sample of Latino and Asian Americans that captured a broader sample than the samples used in the few prior studies that have examined the consequences of downward mobility among immigrants. We also investigated whether persons who immigrated to find work had a greater risk of depression if they were downwardly mobile, compared with those for whom work was a less important reason for immigration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data

We used data from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), a nationally representative household survey of 2,554 Latinos (Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, Cubans, and other Latinos) and 2,095 Asian Americans (Chinese, Vietnamese, Filipinos, and other Asians) conducted between 2002 and 2003 in the coterminous United States. Three elements comprised the sampling design: 1) primary sampling units (Metropolitan Statistical Areas and counties) were selected using probability proportional to size, from which housing units and household members were selected for interviews; 2) a supplemental sample was drawn from census block groups with greater than 5% density of targeted ethnic groups; and 3) second respondents were sampled from households in which a primary respondent had already been interviewed. NLAAS interviews were conducted in English, Spanish, Chinese (Mandarin), Tagalog, or Vietnamese, according to the respondent's preference. Most interviews were conducted in person, while approximately 1,000 were conducted by telephone. Weighted response rates were 75.5% for the Latino sample and 65.6% for the Asian sample (32). We omitted 1,378 respondents from the analysis because they were not first-generation immigrants and omitted 215 respondents because of missing information on key variables; this resulted in a final analytic sample of 3,056 respondents.

Measures

The occurrence of an episode of major depression in the 12 months prior to interview was measured using the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview, following Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Major Depressive Episode criterion 296.2 (33). Although cultural differences in diagnosing and classifying depression have been reported (34), prior studies have suggested that cultural equivalence was reached on the standardized instruments used to assess depression for the NLAAS (35). We measured downward social mobility by comparing respondents’ reports of what their social standing would be in their country of origin with their current social standing in the United States, using 2 survey items based on the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (the “MacArthur ladder”) (36), denoting response choices ranging from 10 (best off) to 1 (worst off) (25). Respondents were instructed: “Think of this ladder as representing where people stand in our society. At the top of the ladder are the people who are the best off—those who have the most money, the most education, and the best jobs. At the bottom are the people who are the worst off—who have the least money, the least education, and the worst jobs or no jobs. The higher up you are on this ladder, the closer you are to the people at the very top, and the lower you are, the closer you are to the people at the very bottom. Please mark a cross on the rung of the ladder where you would place yourself.”

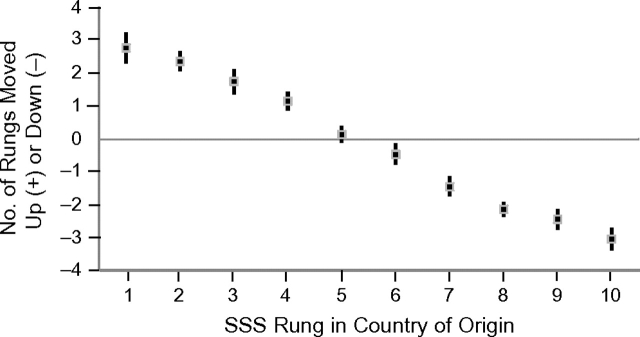

We subtracted respondents’ reported SSS rank in the United States from their reported country-of-origin SSS rank and created a categorical indicator of distance downwardly or upwardly mobile: 3 or more steps downward, 2 steps downward, 1 step downward, no change, 1 step upward, 2 steps upward, or 3 or more steps upward. We also included a categorical measure of SSS in the respondent's country of origin (rungs 1–3, rung 4, rung 5, rung 6, rung 7, or rungs 8–10). It was not possible for respondents who rated themselves lowest in their country of origin (rungs 1–2) to be downwardly mobile by 3 or more steps, just as it was not possible for respondents rating themselves highest in their country of origin (rungs 9–10) to be upwardly mobile by 3 or more steps. To account for these floor and ceiling effects, we collapsed the ends of the distribution of origin SSS as described above. Figure 1 displays the interrelation between origin SSS and the average amount of mobility (upward or downward) between origin SSS and current SSS in the United States.

Figure 1.

Difference (in rungs on the MacArthur ladder (36)) between mean subjective social status (SSS) in the United States and SSS in the respondent's country of origin among Latino and Asian immigrants, National Latino and Asian American Study, 2002–2003. Bars, 95% confidence interval.

To adjust for objective social status, we also included an indicator estimating educational attainment (0 = ≥13 years, 1 = ≤12 years). To assess the importance of extended exposure to conditions in the United States, we included a measure of residence duration (0 = ≥5 years, 1 = <5 years). Citizenship status at the time of interview was dichotomized (0 = US citizen, 1 = not a citizen), as was self-reported fluency in spoken English (0 = good or excellent, 1 = poor or fair). We also adjusted for whether employment was the designated motivation for immigration, suspecting that downward mobility might be a particularly salient experience for such persons. Respondents were asked about a series of possible reasons for immigrating and were asked to rate the importance of those reasons for themselves or their families. The importance of finding employment in the United States was coded so that 0 meant “somewhat important, not at all important, or don't know” and 1 meant “very important.” Multivariate analyses also controlled for sex (0 = female, 1 = male) and age (in years, as a continuous variable).

Analyses

Survey weights were used in all analyses to account for the complex sampling design of the NLAAS and to make the estimates nationally representative (32). Stata software (version 10.0SE; Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) was used for all analyses. We used adjusted Wald tests to assess the prevalence of past-year major depression across categories of predictor variables (Table 1). We fitted logistic regression models that adjusted for the complex sampling design (Table 2). Unless otherwise stated, we used P < 0.05 as the level denoting statistical significance. There was a low level of missing values for the variables used here; 218 cases with missing values were not included in these analyses.

Table 1.

Distribution of Sociodemographic and Immigration-related Factors Among Latino and Asian Immigrants to the United States, According to the Occurrence of an Episode of Major Depression in the Past 12 Months, National Latino and Asian American Study, 2002–2003

| Sample Distribution |

MDE in Past 12 Months |

Adjusted Wald Test for Difference |

||||

| Unweighted No. of Subjects | Weighted Proportion With MDE/Mean | Unweighted No. of Subjects | Weighted Proportion With MDE | F | P Value | |

| Total | 3,056 | 0.064 | 192 | |||

| Social mobilitya (US SSSb vs. country-of-origin SSS) | 0.67 | 0.676 | ||||

| Stable (no change) | 549 | 0.171 | 30 | 0.042 | ||

| 1 step down | 464 | 0.146 | 23 | 0.059 | ||

| 2 steps down | 420 | 0.135 | 24 | 0.058 | ||

| 3 or more steps down | 749 | 0.230 | 53 | 0.079 | ||

| 1 step up | 261 | 0.102 | 19 | 0.067 | ||

| 2 steps up | 267 | 0.113 | 22 | 0.063 | ||

| 3 or more steps up | 346 | 0.103 | 21 | 0.081 | ||

| SSS in country of origin | 2.61 | 0.013 | ||||

| Rungs 1–3 | 567 | 0.184 | 52 | 0.075 | ||

| Rung 4 | 202 | 0.083 | 16 | 0.070 | ||

| Rung 5 | 410 | 0.148 | 24 | 0.071 | ||

| Rung 6 | 265 | 0.094 | 16 | 0.056 | ||

| Rung 7 | 416 | 0.123 | 22 | 0.076 | ||

| Rungs 8–10 | 1,196 | 0.368 | 30 | 0.052 | ||

| Sex | 10.94 | 0.002 | ||||

| Male | 1,411 | 0.506 | 68 | 0.048 | ||

| Female | 1,645 | 0.494 | 124 | 0.080 | ||

| Ethnicity | 9.46 | 0.003 | ||||

| Latino | 1,518 | 0.676 | 130 | 0.073 | ||

| Asian | 1,538 | 0.324 | 62 | 0.044 | ||

| Age, years | 3,056 | 39.84c | ||||

| Educational attainment, years | 2.20 | 0.142 | ||||

| ≤12 | 1,547 | 0.619 | 117 | 0.070 | ||

| >12 | 1,509 | 0.381 | 75 | 0.053 | ||

| Duration of residence in the United States, years | 11.51 | 0.001 | ||||

| ≤5 | 533 | 0.176 | 20 | 0.031 | ||

| >5 | 2,523 | 0.824 | 172 | 0.071 | ||

| Citizenship status | 8.10 | 0.006 | ||||

| Not a US citizen | 1,437 | 0.584 | 80 | 0.053 | ||

| US citizen | 1,619 | 0.416 | 112 | 0.079 | ||

| Spoken English ability | 1.56 | 0.215 | ||||

| Poor/fair | 1,781 | 0.359 | 63 | 0.053 | ||

| Good/excellent | 1,275 | 0.641 | 129 | 0.070 | ||

| Importance of finding a job in the United States | 1.14 | 0.289 | ||||

| Very important | 1,868 | 0.665 | 121 | 0.059 | ||

| Somewhat important/not at all important/don't know | 1,188 | 0.335 | 71 | 0.074 | ||

Table 2.

Odds of Having Experienced an Episode of Major Depression in the Last 12 Months (Logistic Regression Models) Among Latino and Asian Immigrants to the United States, National Latino and Asian American Study (n = 3,056), 2002–2003

| Model 1a (F = 5.92***) |

Model 2b (F = 7.20***) |

|||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Social mobilityc (US SSSd vs. country-of-origin SSS) | ||||

| Stable (no change) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 step down | 1.79 | 0.84, 3.80 | 1.79 | 0.83, 3.86 |

| 2 steps down | 1.88 | 0.94, 3.76† | 1.94 | 0.95, 3.94† |

| 3 or more steps down | 2.81 | 1.34, 5.85** | 2.97 | 1.33, 6.61** |

| 1 step up | 1.47 | 0.51, 4.20 | 1.51 | 0.53, 4.26 |

| 2 steps up | 1.26 | 0.36, 4.41 | 1.10 | 0.33, 3.73 |

| 3 or more steps up | 1.59 | 0.56, 4.52 | 1.50 | 0.49, 4.61 |

| SSS in country of origin | ||||

| Rungs 1–3 | 2.03 | 0.86, 4.81 | 2.23 | 0.75, 6.68 |

| Rung 4 | 2.04 | 1.10, 3.79* | 2.26 | 1.07, 4.76* |

| Rung 5 | 1.86 | 0.89, 3.89† | 1.96 | 0.82, 4.71 |

| Rung 6 | 1.40 | 0.57, 3.41 | 1.44 | 0.53, 3.90 |

| Rung 7 | 1.78 | 0.96, 3.32† | 1.81 | 0.95, 3.45† |

| Rungs 8–10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Latino | 1.70 | 1.11, 2.59* | 1.79 | 1.15, 2.75** |

| Asian | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.54 | 0.40, 0.73*** | 0.56 | 0.41, 0.78** |

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age, years | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.97, 1.01 |

| Educational attainment, years | ||||

| ≤12 | 1.09 | 0.65, 1.81 | ||

| >12 | 1.00 | |||

| Duration of residence in the United States, years | ||||

| ≤5 | 0.45 | 0.24, 0.85* | ||

| >5 | 1.00 | |||

| Citizenship status | ||||

| Not a US citizen | 0.53 | 0.34, 0.84** | ||

| US citizen | 1.00 | |||

| Spoken English ability | ||||

| Poor/fair | 0.74 | 0.34, 1.60 | ||

| Good/excellent | 1.00 | |||

| Importance of finding employment in the United States | ||||

| Very important | 0.72 | 0.43, 1.21 | ||

| Somewhat important/not at all important/don't know | 1.00 | |||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SSS, subjective social status.

* P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; †P < 0.10.

Results were adjusted for mobility, country-of-origin SSS, ethnic group, sex, and age.

Results were adjusted for all of the variables in model 1 as well as educational attainment, duration of residence in the United States, citizenship, spoken English proficiency, and whether employment was an important reason for immigration.

Change in rung on the MacArthur ladder (36).

Rung on the MacArthur ladder (36).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the weighted descriptive characteristics of the NLAAS immigrant respondents and the prevalence of a major depressive episode in the past year, overall and stratified by predictor variables. Overall, 6.4% of the respondents had experienced a major depressive episode, with females (8.0%) being more likely than males (4.8%), Latinos (7.3%) being more likely than Asians (4.4%), persons who had been in the United States for more than 5 years (7.1%) being more likely than those residing in the United States for 5 years or less (3.1%), and US citizens (7.9%) being more likely than noncitizens (5.3%) to have experienced a major depressive episode. In these bivariate comparisons, variation in depressive episode prevalence by country-of-origin SSS was statistically significant; however, differences between persons assigned to different mobility categories were not significant without adjustment for origin SSS.

Table 2 shows the adjusted odds ratios from logistic regression models for experiencing a major depressive episode in the past 12 months after controlling for other predictors. Model 1 adjusted only for mobility, origin SSS, ethnic group, sex, and age, while model 2 added controls for educational attainment, duration of residence in the United States, citizenship, spoken English proficiency, and whether employment was an important reason for immigration. Results from model 2 show that immigrants who dropped 3 or more steps in SSS had higher odds of a past-year major depressive episode (odds ratio = 3.0, 95% confidence interval: 1.3, 6.6), after results were controlled for other predictors. Those whose SSS dropped by 2 steps were also marginally more likely to report past-year depression (odds ratio = 1.9, 95% confidence interval: 0.9, 3.9). Other predictors showed that lower origin SSS was associated with higher odds of depression and that Latinos were significantly more likely than Asians and males were significantly less likely than females to report a major depressive episode. Respondents who had lived in the United States for 5 years or less and those who were not US citizens had lower odds of a recent depressive episode. We also tested for interactions between downward mobility and all other independent variables (data not shown) and found no support for stratifying models on the basis of any of the respondent characteristics included in our models.

DISCUSSION

Findings

Measuring social mobility using respondents’ self-reports of SSS avoids some of the problems that arise with international comparisons of objective measures of socioeconomic status, is more sensitive to subtle aspects of social standing, and incorporates an individual's perceptions of both current circumstances and future opportunities (27, 37). Measuring objective downward mobility among transnational migrants is challenging, because hierarchies of social position and associated rewards (such as financial security or community respect) can vary between sending and receiving countries. For example, a skilled medical professional may have to take a lower-status job in the United States because of differences in required professional credentials, but she may earn a similar amount in real dollars as she did in her country of origin. Comparisons of pre- and postmigration income would suggest no social mobility, but such an individual might consider her status relatively worsened and could experience mental health consequences. Further, it can be difficult to capture an individual's own sense of his career trajectory when using objective measures of socioeconomic position. Even if an immigrant does experience objectively downward mobility upon arrival, as many migrants do (38), he may view it as a temporary situation because of private knowledge about skills and plans that will improve his situation in the future. When asked to rate his social position, he may thus report a higher SSS than his objective situation would warrant and also may not experience any negative mental health consequences of a temporary dip in objective status.

In this large, diverse sample of first-generation Latino and Asian immigrants residing in the United States, we found a positive association between downward social mobility and reports of a major depressive episode in the past 12 months. This association was evident in a large sample of immigrant groups stratified with the intent to represent the variety of Latino and Asian immigrants in the United States. Further, the model was robust to controls for racial/ethnic group, sex, age, educational attainment, duration of residence in the United States, citizenship status, and spoken English ability. Our findings are also consistent with those of the few studies that have examined the consequences of occupational mobility among immigrants (19, 33). Other investigators have suggested or shown that downward mobility following migration can increase vulnerability to depression or other mental health problems, but past studies have focused on very specific immigrant groups and have not used SSS to measure social mobility (2, 4, 5).

Limitations

While the NLAAS sample is large and diverse, our analytic sample was limited to first-generation immigrants from Asian and Latin American countries. Although it was beyond the scope of this analysis and these data, investigators conducting additional studies should consider extending the study population to include people of different immigrant generations and ethnic groups. Samples including multiple immigrant generations would allow exploration of how intergenerational mobility operates to moderate depressive symptoms within families as they become more integrated into their local labor markets and communities and how this may vary for different ethnic groups. However, in additional models (data not shown), we did not find significant interactions between SSS or downward mobility and broadly defined ethnic group (Latino vs. Asian-American). Additionally, the conditions under which people migrate—as refugees or as immigrants in search of improved economic opportunities, for example—are probably important for both subsequent social mobility and the likelihood of developing adverse mental health outcomes. In future studies, investigators should examine reasons for immigration in more detail.

Additionally, the NLAAS data are cross-sectional; therefore, it was not possible to assess whether the association between downward mobility and major depression was causal. We focused on major depressive episodes in the past 12 months to ensure that for the vast majority of our respondents, immigration clearly preceded the episode. Although our results remain robust if we exclude respondents who arrived within the 5 years preceding the survey or those who immigrated prior to age 18 years, these strategies do not eliminate the possibility that a recent depressive episode could influence reports of one's current or prior SSS. However, models that excluded respondents with first onset of major depression 2 or 3 years before the interview produced results unchanged from those presented here (data not shown). Some studies have shown that for specific mental disorders (particularly schizophrenia), the direction of causation leads from early-life mental health problems to downward social mobility over the life course (39, 40). However, our use of migrants helped to reduce concerns about such reverse causality, since migrants tend to be healthier than nonmigrants, with the exception of some refugee groups (41). Moreover, results from models that eliminated respondents for whom depression onset probably occurred before migration—or before age 18 years—were very similar to those presented here (data not shown). While immigrant health advantages may wane with acculturation (42–44), acculturation is a construct that remains difficult to capture in surveys and secondary data analyses (45, 46).

Another limitation is that we could not distinguish between sojourners (persons intending to migrate back to their country of origin) and those who intended to settle in the United States permanently. The NLAAS cannot capture data on sojourners from previous cohorts, as they have returned to their countries of origin. This sampling error could have biased our results toward or against the null hypothesis, depending whether immigrants experiencing higher levels of success stayed in the United States or returned to their countries of origin. We controlled for duration of residence in the United States, but future studies would benefit from the collection of data at multiple time points to enable examination of trajectories of migration experiences, SSS, and mental health over the life course.

Potentially omitted variables could confound the results presented here. The individual circumstances leading to the decision to immigrate might have resulted in negative selection. For example, if downwardly mobile immigrants were more likely to have immigrated because of difficult personal and/or societal circumstances in their country of origin, this could have biased our estimates toward a greater likelihood of finding the hypothesized relation. As another example, people's unmeasured adaptability and resiliency might affect their likelihood of immigrating, their risk of downward mobility, and their mental health—confounding the relations explored here. We also explored whether marital status was a confounder, but while married or cohabiting respondents had a lower risk of depression, inclusion of this measure did not change our results (data not shown).

There are also limitations of the indicators of social position that we used here. First, the accuracy of reports about origin SSS is likely to vary by time since immigration and by the frequency with which people return to their countries of origin. Further empirical clarification would be useful, as would an assessment of whether higher- and lower-status persons consider different contexts when they report on their “community.” Some researchers have debated whether or not SSS adds to our understanding of the relation between objective social position and health (47, 48). We included educational attainment to mark objective social status, but our indicators of SSS may still have captured elements of objective status not reflected in educational attainment. In models not shown here, we also controlled for household income and employment status or experience with unemployment in the past year, but results were substantively unchanged. Moreover, a study of SSS in an elderly English sample showed that while objective and subjective measures were related, correlations between SSS and education, income, and wealth were never greater than 0.45, and SSS provided additional important information in models predicting physical and mental health (31).

Implications

While previous research found that immigrants tend to be healthier than native-born US residents (at least shortly after arrival), these findings suggest that immigrants experiencing downward mobility may be in need of mental health services. Some studies have shown that immigrants (49, 50) and persons of lower socioeconomic position (51–53) are at risk for underutilization of mental health services. The downwardly mobile immigrant respondents in our sample may be particularly unlikely to obtain these services if they experience a decline in socioeconomic resources. Moreover, policies focused only on immigrants of low objective or subjective social status may miss an important risk group: persons who are downwardly mobile from a higher-origin status, whether or not they have fallen into poverty. Notably, the current global economic crisis makes the likelihood of job loss and perceived status decline quite high for many immigrants. Subsequent research focusing on risk and protective factors for depression among immigrants is needed to further identify populations in need of mental health services, as well as which preventive efforts and interventions are most effective for these groups.

Acknowledgments

Author affiliations: Department of Health Management and Policy, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Emily Joy Nicklett); and Department of Sociology, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Emily Joy Nicklett, Sarah A. Burgard).

The authors were supported by grants from the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, as well as by center grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute on Aging to the Population Studies Center of the University of Michigan.

The authors thank Drs. Mary Haan, Daniel Eisenberg, and Katherine Hoggatt for reviewing the manuscript and Drs. Silvia Pedraza and Cleopatra Abdou for providing helpful feedback.

A version of this paper was presented at the 103rd Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, Boston, Massachusetts, August 1–4, 2008.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- NLAAS

National Latino and Asian American Study

- SSS

subjective social status

References

- 1.Takeuchi DT, Zane N, Hong S, et al. Immigration-related factors and mental disorders among Asian Americans. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):84–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DR, Haile R, González HM, et al. The mental health of black Caribbean immigrants: results from the National Survey of American Life. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):52–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):68–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Min PG. Problems of Korean immigrant entrepreneurs. Int Migr Rev. 1990;24(3):436–455. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein BN. Occupational adjustment of refugees: the Vietnamese in the United States. Int Migr Rev. 1979;13(1):25–45. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghaffarian S. The acculturation of Iranian immigrants in the United States and the implications for mental health. J Soc Psychol. 1998;138(5):645–654. doi: 10.1080/00224549809600419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulvaney-Day NE, Alegría M, Sribney W. Social cohesion, social support, and health among Latinos in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(2):477–495. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen BJ, Takeuchi DT. A structural model of acculturation and mental health status among Chinese Americans. Am J Community Psychol. 2001;29(3):387–418. doi: 10.1023/A:1010338413293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gee GC, Ryan A, Laflamme DJ, et al. Self-reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 initiative: the added dimension of immigration. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1821–1828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hovey JD. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2000;6(2):134–151. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):232–238. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riolo SA, Nguyen TA, Greden JF, et al. Prevalence of depression by race/ethnicity: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(6):998–1000. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, et al. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: a study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(3):193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy EJ, Mahalingam R. Perceived congruence between expectations and outcomes: implications for mental health among Caribbean immigrants. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(1):120–127. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy S, McDonald JT. Immigrant mental health and unemployment. Econ Rec. 2006;82(259):445–459. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenski GE. Status crystallization: a non-vertical dimension of social status. Am Sociol Rev. 1954;19(4):405–413. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson EF. Status consistency and symptoms of stress. Am Sociol Rev. 1962;27(4):469–480. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dressler WW. Social consistency and psychological distress. J Health Soc Behav. 1988;29(1):79–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatterji P, Alegría M, Takeuchi D. Psychiatric Disorders and Employment: New Evidence From the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES). (NBER Working Paper no. 14404) Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy JM, Olivier DC, Monson RR, et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to social status. A prospective epidemiologic study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(3):223–229. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiffin PA, Pearce MS, Parker L. Social mobility over the lifecourse and self reported mental health at age 50: prospective cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(10):870–872. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.035246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu Rev Psychol. 1997;48(1):191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(6):837–841. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackman MR, Jackman RW. An interpretation of relation between objective and subjective social status. Am Sociol Rev. 1973;38(5):569–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, et al. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychol. 2000;19(6):586–592. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostrove JM, Adler NE, Kuppermann M, et al. Objective and subjective assessments of socioeconomic status and their relationship to self-rated health in an ethnically diverse sample of pregnant women. Health Psychol. 2000;19(6):613–618. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG. Subjective social status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(6):1321–1333. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franzini L, Fernandez-Esquer ME. The association of subjective social status and health in low-income Mexican-origin individuals in Texas. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(3):788–804. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowd JB, Haan MN, Blythe L, et al. Socioeconomic gradients in immune responses to latent infection. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(1):112–120. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkinson RG. Health, hierarchy, and social anxiety. In: Adler NE, Marmot M, McEwen BS, et al., editors. Socioeconomic Status and Health in Industrial Nations: Social, Psychological, and Biological Pathways. (Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol 896). New York, NY: New York Academy of Sciences; 1999:48–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demakakos P, Nazroo J, Breeze E, et al. Socioeconomic status and health: the role of subjective social status. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(2):330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, et al. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karasz A. Cultural differences in conceptual models of depression. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1625–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alegría M, Vila D, Woo M, et al. Cultural relevance and equivalence in the NLAAS instrument: integrating etic and emic in the development of cross-cultural measures for a psychiatric epidemiology and services study of Latinos. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):270–288. doi: 10.1002/mpr.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kilpatrick FP, Cantril H. Self-anchoring scaling: a measure of individuals’ unique reality worlds. J Indiv Psychol. 1960;16:158–173. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Operario D, Adler N, Williams DR. Subjective social status: reliability and predictive utility for global health. Psychol Health. 2004;19(2):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akresh IR. Occupational mobility among legal immigrants to the United States. Int Migr Rev. 2006;40(4):854–884. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Timms D. Gender, social mobility and psychiatric diagnoses. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(9):1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)10052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE, et al. Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue. Science. 1992;255(5047):946–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1546291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jasso G, Massey DS, Rosenzweig MR, et al. Immigrant health: selectivity and acculturation. In: Anderson NB, Butalo RA, Cohen B, editors. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. pp. 227–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.González HM, Haan MN, Hinton L. Acculturation and the prevalence of depression in older Mexican Americans: baseline results of the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(7):948–953. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, et al. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26(1):367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cochrane R, Bal SS. Mental hospital admission rates of immigrants to England: a comparison of 1971 and 1981. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1989;24(1):2–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01788193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should ‘acculturation’ be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(5):973–986. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Escobar JI, Hoyos Nervi C, Gara MA. Immigration and mental health: Mexican American immigrants in the United States. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2000;8(2):64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macleod J, Davey Smith G, Metcalfe C, et al. Is subjective social status a more important determinant of health than objective social status? Evidence from a prospective observational study of Scottish men. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(9):1916–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lynch JW, Smith GD, Kaplan GA, et al. Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ. 2000;320(7243):1200–1204. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7243.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, et al. Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):91–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lucas JW, Barr-Anderson DJ, Kington RS. Health status, health insurance, and health care utilization patterns of immigrant black men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1740–1747. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ng CH. The stigma of mental illness in Asian cultures. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(3):382–390. doi: 10.3109/00048679709073848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Golberstein E, Eisenberg D, Gollust SE. Perceived stigma and mental health care seeking. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):392–399. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alvidrez J. Ethnic variations in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Ment Health J. 1999;35(6):515–530. doi: 10.1023/a:1018759201290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]