Abstract

Hypoxic heart disease is a predominant cause of disability and death worldwide. Since adult mammalian hearts are incapable of regeneration after hypoxia, attempts to modify this deficiency are critical. As demonstrated in zebrafish, recall of the embryonic developmental program may be the key to success. Because thymosin β4 (TB4) is beneficial for myocardial cell survival and essential for coronary development in embryos, we hypothesized that it reactivates the embryonic developmental program and initiates epicardial progenitor mobilization in adult mammals. We found that TB4 stimulates capillary-like tube formation of adult coronary endothelial cells and increases embryonic endothelial cell migration and proliferation in vitro. The increase of blood vessel/epicardial substance (Bves) expressing cells accompanied by elevated VEGF, Flk-1, TGF-β, FGFR-2, FGFR-4, FGF-17 and β-Catenin expression and increase of Tbx-18 and Wt-1 positive myocardial progenitors suggested organ-wide recall of the embryonic program in the adult epicardium. TB4 also positively regulated the expression and phosphorylation of myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (Marcks), a direct substrate and indicator of protein kinase C (PKC) activity in vitro and in vivo. PKC inhibition significantly reduced TB4 initiated epicardial thickening, capillary growth and the number of myocardial progenitors. Our results demonstrate that TB4 is the first known molecule capable of organ-wide activation of the embryonic coronary developmental program in the adult mammalian heart after systemic administration and that PKC plays a significant role in the process.

Keywords: Thymosin β4, cardiac regeneration, coronary development, progenitor cells, PKC

1. Introduction

Defects in the coronary vascular system have significant impact on heart function and disease. Ischemic myocardial infarctions cause irreversible cell loss and scarring and are major source of morbidity and mortality in humans. A proper angiogenic response after infarction is critical for healing and repair.

A variety of stimuli can initiate the formation of new blood vessels in the heart, presumably through common downstream signaling cascades that trigger quiescent endothelial or other progenitor cells to form nascent tubular structures [1]. Although many of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of embryonic coronary development are well investigated, the molecular basis of angiogenesis in the embryo seems to differ from the pathological vessel regeneration in adults [2]. Blood vessels in the embryo form primarily through vasculogenesis, a differentiation of precursor cells (angioblasts) to endothelial cells that assemble into a vascular network. The critical cellular events include the formation of the primordium, the proepicardial organ and the epicardium, generation of the subepicardial space and mesenchymal cells and development and remodeling of the vascular plexus [3, 4]. New vessels in adults arise mainly through angiogenic sprouting, although vasculogenesis may also occur [2]. Many studies have attempted to reveal the molecular and cellular mechanisms that support cardiac regeneration in adult hearts and to identify progenitor cells capable of cardiac repair [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. In zebrafish, epicardial cells invade the myocardium and create a vascular network likely to encourage cardiac regeneration in adults [12]. Thus, the injured adult zebrafish heart can recall signaling pathways essential during embryonic coronary development, and the ability to mobilize epicardial cells may be the primary reason they effectively regenerate myocardium. Since adult mammalian hearts typically show insufficient neovascularization after myocardial infarction, experimental attempts to modify this deficiency by directly utilizing epicardial cells or their progenitors could prove favorable for cardiac regeneration.

We previously demonstrated that thymosin β4 (TB4), a 43-amino-acid G-actin-sequestering peptide is expressed in the embryonic heart, stimulates cardiomyocyte migration in vitro and increases cardiac function while promoting the survival of cardiomyocytes in adult mice in vivo [13]. More recently, analysis of heart-specific TB4 knockdown mouse embryos revealed a critical role for the peptide in epicardial development and coronary artery formation [14]. However, the effects of TB4 on the adult epicardium and coronary growth in vivo have not been discussed.

Here we show that TB4 initiates capillary-like tube formation of adult coronary endothelial cells, induces endothelial cell migration and proliferation in embryonic cardiac explants in vitro and supports revascularization in vivo. Importantly, it induces an organ-wide epicardial thickening and progenitor cell activation in adults similar to the changes in developing embryos and in regenerating adult zebrafish, while initiating the expression of numerous pro-angiogenic developmental genes. TB4 initiated protein kinase C (PKC) activity revealed to be essential for the epicardial activation.

Thus, TB4 supports cardiac regeneration not only by inhibiting myocardial cell death after infarction, but also through induction of vessel growth, myocardial progenitor mobilization and by reactivating the embryonic developmental program in adult epicardium in vivo.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

TB4 was synthesized by the Department of Biochemistry and by the Protein Chemistry Technology Center at UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX). Human coronary endothelial cells (HCEC) were purchased from PromoCell GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany). Rat tail collagen was purchased from Roche Diagnostics Corporation (Indianapolis, IN). Tissue culture reagents were purchased from Gibco/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and Promo Cell GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany). Primary antibodies for Western blot and immunohistochemistry were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Danvers, MA) and Abnova Corporation (Taipei, Taiwan). TB4 primary antibody was a gift of H. Yin at UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX) [15].

2.2. Animals and surgical procedures

Myocardial infarctions were produced in C57BL/6J male mice at 16 weeks of age (25–30 g) by ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery as described [13, 16]. All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School Institutional Animal Care Advisory Committee and were in compliance with the rules governing animal use as published by the NIH. Mice were sedated in an isoflurane chamber (5%) for 60 seconds until self-designed coaxial mask could be safely applied. The mask supplied continuous isoflurane (2.0%) and oxygen (98.0%) under positive pressure from a Harvard small animal respirator throughout the procedures. Immediately after ligation, half of the mice were injected intraperitoneally with 150μg of TB4 in 300 μl PBS and half with 300 μl PBS, as described [13]. The effective dose of synthesized TB4 was determined by in vitro cell migration assays (Supplemental Figure 2 k) and in vivo biodistribution of TB4 [13, 17]. For in vivo inhibition of PKC activity mice were treated systemically with 10μg of Bisindolylmaleinimide-I hydrochloride in 100 μl PBS (Chalbiochem, San Diego, CA) and with 150μg of TB4 in 300 μl PBS or 300 μl PBS in two boluses after myocardial infarction. We administered buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) for post-operative pain control. Hearts were removed 1, 3, or 14 days after ligation and processed for further investigations. Exposure time for immunohistological analysis was 3 sec.

2.3. cDNA Microarray

RNA from the core and remote areas of four TB4 treated, and four PBS treated hearts were isolated 24 h after treatment using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) reagent following the manufacturer's protocol. The quality and quantity of RNA were determined and processed with Mouse Affymetrix Genome 430 2.0 arrays at the Microarray Core Facility at UT Southwestern Medical Center. Four independent experimental and four control arrays were analyzed with GeneChip operating software (GCOS, Affymetrix), GeneSpring 7.0 (Silicon Genetics), significance analysis of microarrays (SAM, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, USA), and Spotfire Decision Site 8.2 (Spotfire). Computational hierarchical cluster analysis was performed with Spotfire and CLUSFAVOR 6.0 (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA). Analysis of variance was performed with Spotfire. The data were normalized by mean values (for Spotfire pair-wise comparisons and SAM two-class comparisons) or percentile values (for GeneSpring analyses). Gene expression changes were considered significant if the p value was less than 0.05, the fold change at least 1.5, and gene expression was altered in all replicate comparisons. Genes expressed at different levels in untreated controls were excluded from analysis, as they most likely represent experimental variation between samples.

2.4. Epicardial progenitor cell isolation

Adult epicardial cells were isolated (Supplemental Methods) and directly cultured on Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) or immunostained and separated by FACS sorting (Supplemental Methods). Sorted cells were cultured on gelatin coated culture dishes for 0, 7 and 14 days in endothelial cell growth medium MW (PromoCell, Germany). Cultured cells were analyzed by immunocytochemistry.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Statistical calculations were performed using a standard t-test of variables with 95% confidence intervals.

3. Results

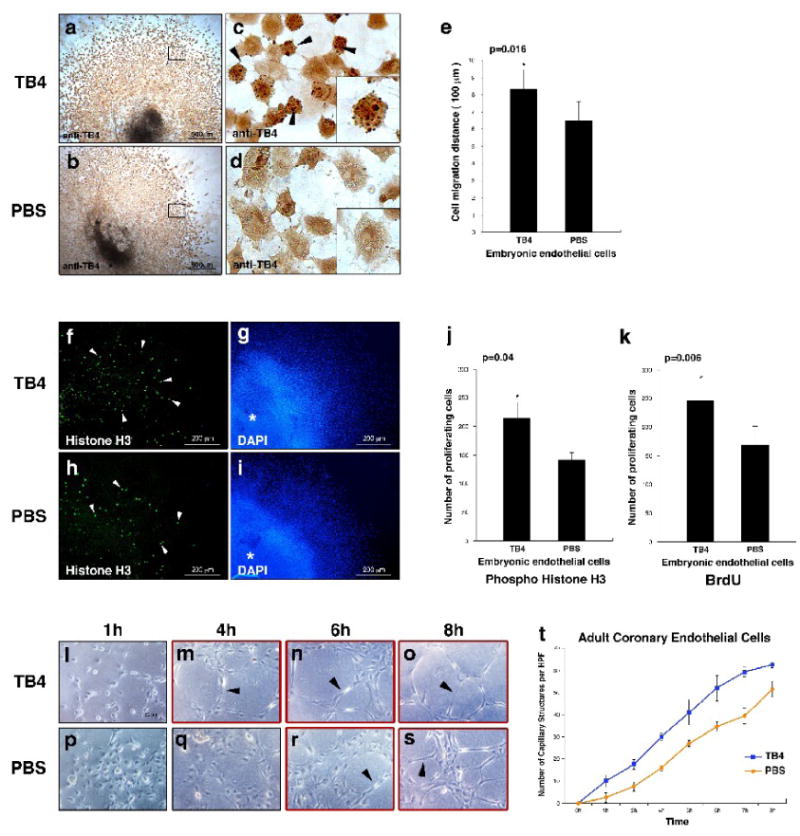

3.1. TB4 induces embryonic endothelial cell migration and proliferation and initiates capillary structure formation of adult coronary endothelial cells in vitro

We tested the effects of TB4 on cardiac endothelial cell migration by embryonic heart explant assays on rat tail collagen [18]. Since TB4 is expressed in endothelial and myocardial cells and is absent in cardiac mesenchyme (Supplemental Figure 1 and [13]) we used TB4 primary antibody to identify endothelial cells. Exogenously administered TB4 significantly increased embryonic endothelial cell migration (Figure 1 a, e) by facilitating the number of round actively moving cells in vitro (Figure 1 c arrowheads) (Supplemental Figure 1B). We did not detect increase in cellular death (data not shown). Phospho-histone H3 staining and immunocytochemistry after BrdU administration indicated that TB4 significantly affects endothelial cell proliferation. (Figure 1 f-k). An explanation for increased proliferation could be the activation or up-regulation of β-Catenin expression [19, 20] by TB4 in vitro (Supplemental Figure 1C).

Figure 1. TB4 induces embryonic endothelial cell migration and proliferation and initiates capillary-like structure formation of HCECs in vitro.

a–d, Mouse E11.5 cardiac outflow tract endothelial cells stained with anti-TB4/peroxidase after TB4 (a,c) or PBS (b,d) treatment. In c, black arrowheads and high magnification of a representative cell in the corner boxed area indicate increase in actively migrating cells with rounded morphology after TB4 treatment. (c) and (d) are high-magnification images of the boxed areas in (a) and (b). e, Distance of embryonic endothelial cell migration in E11.5 cardiac outflow tract explants with or without TB4 treatment. Bars indicate standard deviation at 95% confidence limits (n=6), *p < 0.05. f-k, Staining of mouse E11.5 cardiac outflow tract explants with phospho-histone H3 antibody (f,h) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (g,i) shows increased endothelial cell proliferation (white arrowheads) after TB4 (f) treatment compared to PBS (h). Asterix indicates center of the explant. j-k, Number of proliferating embryonic endothelial cells with or without TB4 treatment. Bars indicate standard deviation at 95% confidence limits (n=6), *p < 0.05. l-s, Adult HCECs form capillary structures in advance when treated with TB4 (m-o black arrowheads) compared to PBS (r-s, black arrowheads) on matrigel. t, TB4 increases the number of HCEC capillary like structures on matrigel. Bars indicate standard deviation at 95% confidence limits (n=6).

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) form capillary structures when plated on matrigel [21, 22]. To analyze the effect of TB4 on cardiac vessel formation we checked whether adult human coronary endothelial cells (HCEC) behave similarly to HUVECs and if TB4 may alter the process in vitro. Our results indicated that HCECs are capable of capillary structure formation when cultured on matrigel and that TB4 expedites this process when compared to PBS treated controls (Figure 1 l-t).

3.2. TB4 stimulates vascular growth and initiates organ-wide thickening of the adult epicardium in vivo

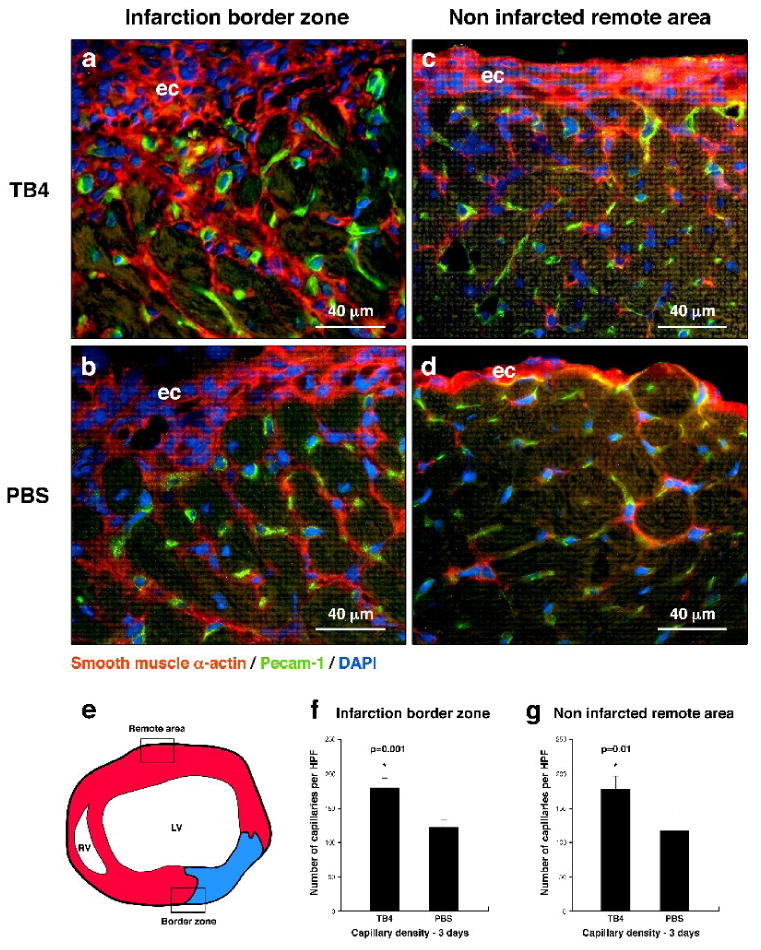

Because of our in vitro observations on cardiac and vessel endothelial cells, we assessed the effect of TB4 on coronary vascular growth in adult mice after hypoxia. We created cardiac infarctions by ligating the LAD coronary artery in adult mice followed by immediate systemic TB4 or PBS administration. Simultaneous staining with platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (Pecam-1) and smooth muscle α-actin (sm α-actin) specific primary antibodies revealed significant increase in capillary density three days after TB4 injection at the infarction border zone and non infarcted remote areas of the hearts (Figure 2).

Figure 2. TB4 initiates cardiac vessel formation in vivo.

a-d, Immunohistochemistry using smooth muscle α-actin (red) and Pecam-1 (green) specific antibodies with DAPI staining (blue) revealed increase in capillary structures at the margin of the scar (a,b) and in the remote areas (c,d) three days after TB4 treatment (a,c) when compared to PBS (b,d). e, Schematic of adult mouse heart transverse sections used for histological analysis. Boxes indicate the areas investigated in (a-d). f-g, Number of capillaries increases significantly after TB4 treatment compared to PBS control. Bars indicate standard deviation at 95% confidence limits (n=6), *p < 0.05. LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; ec, epicardium

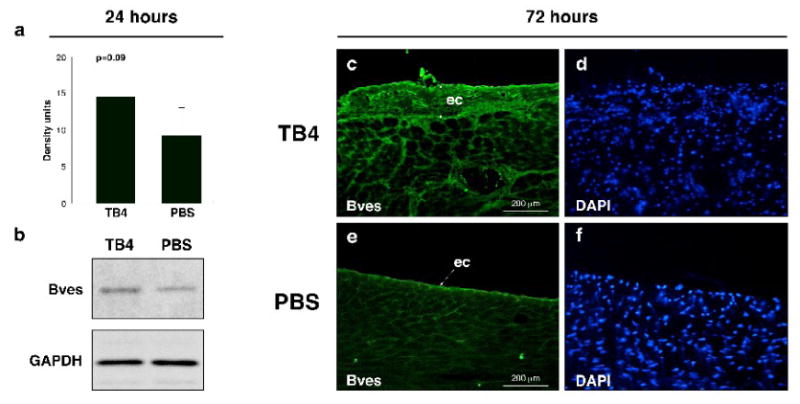

Coronary vessels are believed to originate from the epicardium during development. Recent work from Lepilina et al. [12] demonstrated that an elaborate sequence of organ-wide and local responses by epicardial cells increases cardiac regeneration and revascularization in adult zebrafish. The changes of the epicardium in adult fish are similar to the alterations in developing embryos. Mammalian hearts however are incapable of such neovascularization or general regeneration after cardiac injury. Thus, experimental attempts to activate the embryonic coronary developmental program in mammals could enhance cardiac regeneration. To determine if TB4 may stimulate an epicardial response, we analyzed the changes in blood vessel/epicardial substance (Bves) expression 24 and 72 hours after systemic TB4 administration. Bves is widely expressed in the developing coronary vascular system [23, 24] and is also used as one of the markers of epicardial cells or cells of epicardial origin in adult and embryonic tissues. In our experiments, we observed elevated Bves expression 24 hours after TB4 treatment, and an increase in Bves positive cells with general organ-wide thickening of the adult epicardium 72 hours after peptide administration in the non-infarcted remote regions of the hearts (Figure 3). We found that most of the adult epicardial cells also express sm α-actin (Figure 2 c, d) (Supplemental Figure 2 a-h) and that the number of sm α-actin positive cells significantly increases proximal to the thickened epicardium after TB4 treatment (Supplemental Figure 2 i, j), indicating direct connection between the thickened epicardium and new capillary outgrowths.

Figure 3. Increase of Bves expression after TB4 treatment at the non infarcted remote areas of the adult mouse heart in vivo.

a, Western blot analysis using Bves and GAPDH primary antibodies shows increase in Bves expression after TB4 treatment in the non infarcted cardiac tissue 24 h after ligation. b, Densitometric analysis of Western blot results (a) normalized to GAPDH loading control. Bars indicate standard deviation at 95% confidence limits (n=6). c-f, Immunohistochemical analysis with anti-Bves antibody shows increase in Bves-positive cells and organ-wide thickening of the remote epicardium 3 days after systemic TB4 treatment (c) compared to PBS (e). (d,f) are DAPI stain of (c,e). ec, epicardium

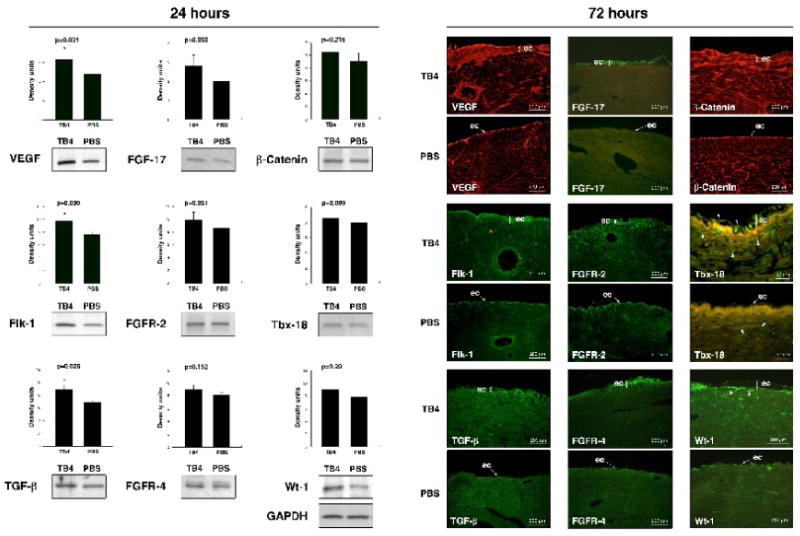

3.3. TB4 initiates the expression of embryonic developmental genes in adult mouse epicardium

Our in vivo results suggested that TB4 might activate the adult epicardium and initiate vessel growth. To support this hypothesis we investigated the expression of proteins essential during coronary development in embryos by Western blot and by immunohistochemistry 24 and 72 hours after systemic TB4 injection (Figure 4, Supplemental Figure 3). Our data indicate that TB4 affects developmental gene expression as early as 24 hours after systemic injection (Figure 4 A) while alterations in epicardial morphology were first observed three days after the initial peptide treatment (Figure 4 B). We detected significant increase in VEGF, VEGF receptor-2 (Flk-1) and TGF-β expressions and moderate elevation in FGF-17, FGF receptor-2 (FGFR-2) and FGFR-4 levels by Western blot after 24 hours of treatment. Immunohistochemistry after 3 days of TB4 injection indicated that these changes are primarily manifested in the thickened epicardium (Figure 4B). The alterations in gene expression were consistent with the findings in regenerating adult zebrafish hearts [12]. Since FGF and WNT signaling pathways can function jointly to sustain mesenchymal growth or to coordinate epithelial morphogenesis during development [25, 26], and epicardium-derived progenitor cells also require β-Catenin for coronary artery formation [27], we asked whether TB4 may also alter β-Catenin expression in vivo. Our findings revealed an increase in β-Catenin expression in the thickened epicardium and in developing vasculature of the adult mouse hearts, which may indicate a role for β-Catenin and a regulatory convergence for FGF and WNT signaling in the epicardial initiation process.

Figure 4. Systemic TB4 injection beneficially alters the expression of proteins essential for embryonic coronary development and myocardial progenitor activation in mammals and during cardiac regeneration in adult zebrafish.

A. Densitometric analyses of Western blot results of adult cardiac tissue indicate significant changes in VEGF, Flk-1 and TGF-β expressions and moderate increase in FGF-17, FGFR-2, FGFR-4, β-Catenin, Tbx-18 and Wt-1 expressions 24 h after systemic TB4 injection when compared to PBS treatment in vivo. Heart tissue was harvested from the healthy, non infarcted areas of the hearts. Density units were normalized to GAPDH loading control. Bars indicate standard deviation at 95% confidence limits (n=6), *p < 0.05. B. Immunohistochemical analysis shows increase in VEGF, Flk-1, TGF-β, FGF-17, FGFR-2, FGFR-4, β-Catenin, Tbx-18 and Wt-1 expressions notably in the thickened epicardium at the intact areas of ligated adult mouse hearts 3 days after TB4 treatment when compared to PBS. White arrowheads in Tbx-18 sections indicate increase of Tbx-18 positive cells in TB4 treated epicardium and myocardium. White arrowheads in Wt-1 sections point at subepicardial localization of Wt-1 positive progenitors. ec, epicardium

In our previous work, we showed that TB4 significantly reduces scar volume by inhibiting myocardial cell death 24 hours after infarction [13]. Because of recent studies suggesting that the epicardium serves as a source of cardiomyocytes in the embryo [9, 10] we asked whether TB4 could also initiate long term post ischemic muscle regeneration by myocardial progenitor activation in adult mouse hearts. We found that TB4 raises the expression of Tbx-18 and Wt-1 in the non infarcted remote areas after 24 hours (Figure 4 A) and significantly increases the number of Tbx-18 and Wt-1 positive cells after three days (Figure 4 B), (Supplemental Figure 3 B). Tbx-18 positive cells were distributed equally in the epicardium and myocardium, while Wt-1 positive cells were primarily located in the subepicardial space (Figure 4 B white arrowheads), suggesting that Wt-1 and Tbx-18 may mark different progenitor populations in the activated epicardium. Finally, the analysis of additional known regenerative proteins revealed that TB4 significantly increases Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) expression while p38 expression and p38 and JNK activation were significantly reduced. We detected minor alterations in extracellular signal regulated kinase1/2 (Erk1/2) activation, inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), endothelial NOS (eNOS) and neuronal NOS (nNOS) levels in the non infarcted cardiac tissue in the first 24 hours of treatment (Supplemental Figure 3 A). These observations strongly suggest an early molecular support for new vessel formation and myocardial regeneration by initiation of the embryonic epicardial developmental program and by activation of myocardial progenitors in adult mouse hearts after TB4 injection in vivo.

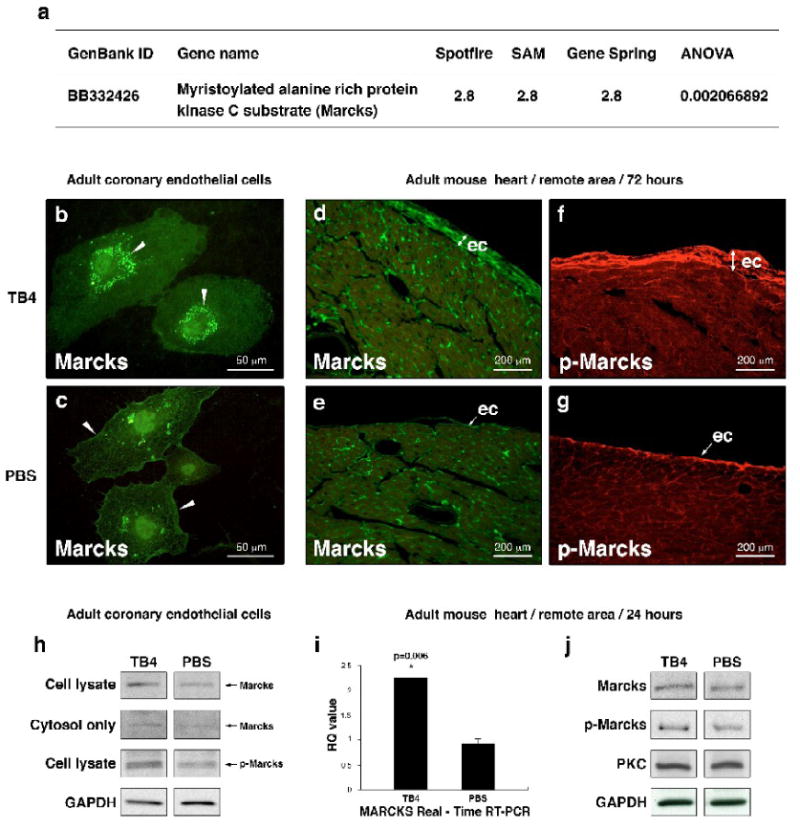

3.4. TB4 increases the number of Marcks positive cells and activates PKC in the adult epicardium

To further identify molecules that respond to TB4 and are expressed in the adult epicardium, we analyzed adult mouse hearts with Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Affymetrix cDNA microarrays 24 h after cardiac infarction (Supplemental Figure 4). While focusing on genes significant in angiogenesis, myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (Marcks) was up-regulated 2.8-fold after TB4 administration (Figure 5 a). These results were confirmed by real-time RT-PCR (Figure 5 i). Marcks is a prominent intracellular substrate for PKC, a regulator of angiogenesis [28], and is distributed in numerous cell types, including vascular endothelial cells [29]. It mediates PKC signaling through its phosphorylation [30], resulting in a release of Marcks from the cell membrane to the cytosol. These responses are commonly used to indicate PKC activity in vitro [31].

Figure 5. TB4 alters Marcks expression in vitro and activates PKC in adult epicardium in vivo.

a, cDNA microarray on adult mouse hearts reveals 2.8-fold increase in Marcks expression 24 h after TB4 treatment compared to PBS. i, Real-time RT-PCR of mouse heart RNA confirms the in vitro cDNA microarray results. Bars indicate standard deviation at 95% confidence limits (n=6), *p < 0.05. RQ, relative quantitation assay. b-c, Immunocytochemical analysis of HCECs with Marcks-specific antibody (green) shows increased Marcks expression and translocation from the cell membrane (c white arrowheads) to the cytosol (b white arrowheads) after TB4 treatment (b) suggesting a change in PKC activity by TB4 in vitro. h, Western blot of complete cell lysates and cytosol fractions from adult coronary endothelial cells 24 hours after TB4 or PBS treatment support translocation of Marcks protein into the cytosol and indicate increase in Marcks activation (p-Marcks) by PKC after TB4 treatment in vitro. d-g, Immunohistochemical analysis shows significant increase in Marcks (d,e) and phospho-Marcks (f,g) expressions in thickened epicardium at the intact areas of ligated adult mouse hearts 3 days after TB4 treatment (d,f)). j, Western blot analyses of adult cardiac tissue from the remote areas by Marcks, p-Marcks, PKC, and GAPDH antibodies 24 h after treatment show increase in Marcks expression and phosphorylation without significant change in PKC levels 24 hours after TB4 treatment in vivo (n=6).

To determine if TB4 affects PKC activation in cell culture, we investigated Marcks phosphorylation and localization in adult HCECs by Western blot and immunocytochemistry after TB4 treatment. Our results indicate that external administration of TB4 increases Marcks expression, phosphorylation and translocation from the cell membrane to the cytosol suggesting that TB4 modulates PKC activity (Figure 5 b, c, h). PKC lies on the signal transduction pathways by which VEGF augments development and angiogenesis during initial and later stages of vessel development [1]. Since VEGF expression was significantly increased after TB4 treatment (Figure 4) and PKC is known to activate Akt by Ser473 phosphorylation [1, 32], we speculate that VEGF mediated PKC activation represents an ILK-independent means of Akt activation by TB4 in cardiac cells.

To confirm our in vitro results, we examined the effect of TB4 on Marcks expression and phosphorylation after cardiac ligation in adult mice. As shown by Western blot (Figure 5 j) and immunohistochemistry, the expression (Figure 5 d, e, j) and phosphorylation (Figure 5 f, g, j) of Marcks increased, especially in the thickened epicardium, indicating a role for PKC in epicardial activation and coronary re-growth in adults after TB4 treatment in vivo. Additionally, analysis of Bves, TB4, VEGF and p-Marcks expression showed an increase and co-localization of Bves, TB4 and VEGF in the upper layer of the thickened epicardium (Supplemental Figure 5 A a, e, white arrowheads) after TB4 treatment, while p-Marcks-positive cells were mainly found in the subepicardium (Supplemental Figure 5 A c, g, white arrowheads). This is consistent with an indirect activation of PKC by TB4, possibly through increasing VEGF expression in the primary epicardial cells.

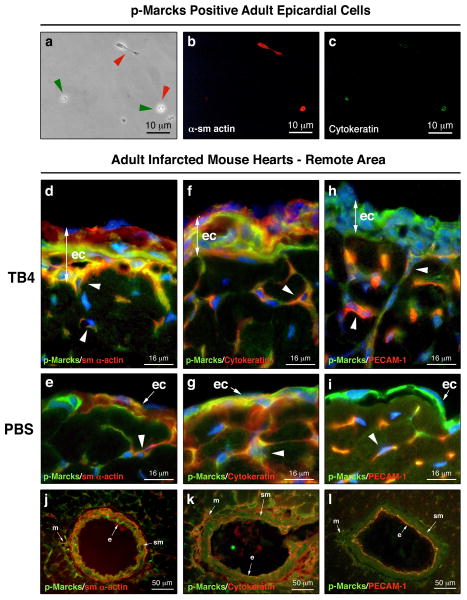

3.5. p-Marcks positive adult epicardial cells show endothelial and smooth muscle fate

Recent results suggest that the epicardium is highly heterogenous and serves as a source of various progenitors in the embryonic heart [9, 10]. Consistent with these observations, immunohistochemistry on adult hearts showed several p-Marcks positive cells lacking VEGF while expressing Bves in wild type or in TB4 activated adult epicardium (Supplemental Figure 5 A g, l white arrowheads, c, j). Because of these findings, we asked whether p-Marcks positive cells might represent a distinct epicardial cell population of the adult heart. First, we cultured non-separated or FACS sorted p-Marcks positive and p-Marcks negative adult mouse epicardial cells (Supplemental Figure 5 C) on matrigel or gelatin coated dishes. Our data revealed that purified p-Marcks positive epicardial cells are small, have narrow cytoplasm and express both smooth muscle and/or endothelial markers in cell culture (Figure 6 a-c), while p-Marcks negative epicardial cells differentiate into large sm α-actin positive and Cytokeratin negative lineages (Supplemental Figure 5 C b, c). Consistent with our in vitro results, co-immunostaining with p-Marcks, sm α-actin, Cytokeratin and Pecam-1 antibodies indicated an overlap of smooth muscle and early and late endothelial markers in the newly developing capillaries (Figure 6 d-i white arrowheads) and in the endothelial and smooth muscle layers of the mature vessel wall (Figure 6 j-l). Similar to p-Marcks and VEGF expression, the adult epicardium contained a mixed population of p-Marcks, sm α-actin and Cytokeratin positive cells but did not stain for the late endothelial marker Pecam-1 (Figure 6 h, i). Also, external administration of TB4 to non-separated adult epicardial cultures resulted in a large number of p-Marcks and Cytokeratin specific endothelial colonies when compared to PBS treated controls (Supplemental Figure 5 B white arrowheads). Thus, our in vitro and in vivo results suggest that p-Marcks positive epicardial cells may be a source for smooth muscle and endothelial cells of the newly developing vessels in the injured adult heart.

Figure 6. p-Marcks labels future endothelial and smooth muscle cells in the adult epicardium.

a-c, Immunocytochemical analysis of p-Marcks positive epicardial cells with sm α-actin (b) and p-Cytokeratin (c) primary antibodies indicate endothelial and/or smooth muscle cell fate seven days after culturing. (a) endothelial marker positive cells highlighted by green arrowheads, smooth muscle marker positive cells highlighted by red arrowheads. d-i, sm α-actin, Cytokeratin, Pecam-1 (red) and p-Marcks (green) co-immunostaining with DAPI (blue) reveals cellular heterogeneity in the TB4 activated (d,f,h) or in the single layered epicardium (e,g,i) of adult control hearts. White arrowheads in d-i indicate p-Marcks positive cells with endothelial or smooth muscle cell fate in the developing capillaries. j-l, Immunohistochemical analysis of the mature coronary vessels suggest smooth muscle and endothelial cell fate for p-Marcks positive cells. ec, epicardium; e, endothel; sm, smooth muscle; m, mesenchyme

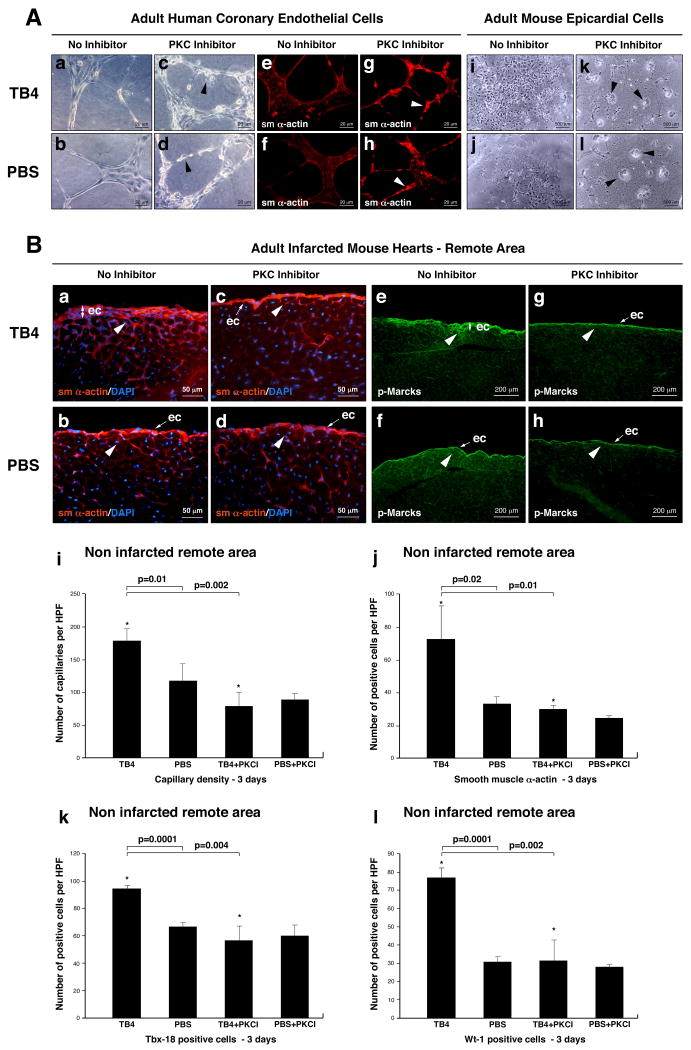

3.6. Inhibition of PKC activity suppresses TB4 initiated epicardial activation in adult mice

To define whether PKC activity may be regulatory for TB4 induced epicardial progenitor activation, we tested the effect of Bisindolylmaleimide-I (PKC inhibitor) on HCECs and adult epicardial cells in vitro, and injected 10μg of PKC inhibitor intraperitoneally with or without TB4 into infarcted adult mice. Animals were harvested and hearts were processed for further analysis three days after injection. Our in vitro experiments indicated that PKC inhibition alters HCEC capillary structure formation (Figure 7 A a-d; Supplemental Figure 6 k) and inhibits epicardial cell differentiation (Figure 7 A i-l) on matrigel. The newly formed structures contained irregular sm α-actin positive cells and showed disordered morphology (Figure 7 A e-h). In live animals immunohistochemistry with Bves (Supplemental Figure 6 a-d), VEGF (Supplemental Figure 6 e-h) or p-Marcks (Figure 7 e-h) specific primary antibodies showed reduction of epicardial thickening. We also observed a significant decrease in capillaries and sm α-actin positive cells at the non infarcted remote areas (Figure 7 B a-d, i, j) or borders of the infarction (Supplemental Figure 6 i, j) after Bisindolylmaleimide-I injection. This suggests reduction of coronary outgrowths from the epicardium in the TB4+PKC inhibitor treated infarcted hearts. In addition, Bisindolylmaleimide-I significantly suppressed the number of TB4 activated Tbx-18 and Wt-1 positive progenitor cells in the non infarcted remote areas of the hearts (Figure 7 k, l). Our results suggest that TB4 mediated direct or indirect PKC activation is essential for epicardial cell transformation and migration in the adult mouse heart in vivo (Supplemental Figure 6 l, m).

Figure 7. PKC activity is essential for TB4 induced epicardial activation in adult mice in vivo.

A, Bisindolylmaleinimide-I alters capillary formation of HCECs and inhibits adult epicardial cell transformation on matrigel. a-h, HCECs transform to irregular, rounded (c,d black arrowheads) sm α- actin positive cells (g,h white arrowheads) when treated with PKC inhibitor. i-l, Bisindolylmaleinimide-I inhibits adult epicardial cell transformation on matrigel (k,l black arrowheads point at non-transformed cell groups). B. Immunohistochemical analyses with anti-sm α-actin (a-d) and anti-p-Marcks (e-h) antibodies show reduced epicardial thickening and inhibition of capillary outgrowths (c,g white arrowheads) in TB4+PKC inhibitor treated adult hearts (c,g) when compared to TB4 and no inhibitor treated controls (d,h). Decrease in p-Marcks expression indicated sufficient reduction of PKC activity in the inhibited control hearts (h). Administration of Bisindolylmaleinimide-I itself does not alter the adult mouse epicardium in vivo (d,h). i-j, Bisindolylmaleinimide-I significantly suppresses the number of capillaries (i) and sm 28-actin positive cells (j) in the non infarcted remote areas of TB4 treated hearts (n=6). k-l, Inhibition of PKC activity significantly suppresses the number of TB4 activated Tbx-18 and Wt-1 positive myocardial progenitor cells in the non infarcted remote areas (n=6). Bars indicate standard deviation at 95% confidence limits. *p < 0.05. ec, epicardium

4. Discussion

This study shows that TB4 increases or activates proteins and epicardial progenitors important for myocardial regeneration or vascular growth and initiates organ-wide activation of the adult epicardium reminiscent of embryonic coronary development by re-stimulation of signaling pathways essential during embryogenesis. It reveals a novel role for PKC in this process. Additionally, it presents some evidence that p-Marcks positive epicardial cells may serve as endothelial and smooth muscle progenitors for future capillaries in the adult mammalian heart.

Despite the high specificity of the signaling systems triggering angiogenic responses in epicardial endothelial cells, there are no specific signaling pathways or transcription factors known that regulate the entire process [1]. Given the roles of Pecam-1, VEGF, MAP kinases, ILK, Akt, FGFs, NOSes, β-Catenin, and PKC in vessel formation, our findings suggest that TB4 may initiate broad angiogenic events that promote cardiac regeneration after cardiac injury in adults. This is consistent with the recent observations that TB4 regulates epicardial development in embryonic mice [14].

Our findings also suggest that TB4 augments cardiac regeneration and increases cardiac function in the adult hypoxic heart through at least two steps. First, it inhibits myocardial cell death 24 h after cardiac ligation as previously described [13]. Second, TB4 can initiate signaling pathways responsible for late-phase or chronic regeneration, such as vascular re-growth or progenitor cell activation. This process may be initiated by organ-wide epicardial thickening and activation of endothelial-mesenchymal transformation of adult epicardial cells, is most likely regulated by PKC, and is first visible 3 days after TB4 administration. Since TB4 is well conserved during evolution, it might be one of the factors responsible for epicardial activation during cardiac regeneration in zebrafish [12].

Coronary vessel growth is independent of cells outside the heart once the epicardium is formed [33]. Thus the potential for TB4 to activate dormant cardiac stem cells that exist in the adult mammalian heart is critical for cardiac regeneration. Furthermore, since TB4 also inhibits inflammation [11, 34, 35], this property may be also supportive during cardiac regeneration in adults.

The concept of developing novel therapies that recapitulate embryonic events to achieve coupled myocardial and vascular regeneration is expanding [36]. Recall of the embryonic developmental program in the adult heart may be the key to success. Our findings reveal the cellular and molecular changes initiated by TB4 during adult coronary remodeling in vivo. TB4 is the first molecule capable of initiating the embryonic coronary developmental program in adult mammalian hearts by systemic administration while protecting the myocardium after infarction. Since the discovery of innovative ways to enhance cardiac regeneration will be important for future therapies, the continued investigation of molecular signals initiated by TB4 could be critical.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to thank H. Ball and LJ. Burdine for providing TB4 peptide, HR. Garner for financial support to perform microarrays, A. Mobely for FACS separation of progenitor cells and C. Nolen for animal work. We are grateful to JE. Marquette for helping with visual graphics and manuscript review.

Abbreviations

- Akt

Protein kinase B

- BrdU

Bromodeoxyuridine

- Bves

Blood vessel/epicardial substance

- DAPI

4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- eNOS

Endothelial NOS

- Erk1/2

Extracellular signal regulated kinase1/2

- FACS

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FGF-17

Fibroblast growth factor-17

- FGFR-2,-4

Fibroblast growth factor receptor-2, -4

- Flk-1

VEGF receptor-2

- HCEC

Human coronary endothelial cell

- HUVEC

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- ILK

Integrin linked kinase

- iNOS

Nitric oxide synthase

- JNK

Jun N-terminal kinase

- LAD

Left anterior descending

- MAP kinase

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- Marcks

Myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate

- nNOS

Neuronal NOS

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- Pecam-1

Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- sm α-actin

Smooth muscle α-actin

- TB4

Thymosin β4

- Tbx-18

T-box-18

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-beta

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- Wt-1

Wilms tumor-1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Muñoz-Chápuli R, Quesada AR, Ángel Medina M. Angiogenesis and signal transduction in endothelial cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2224–2243. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4070-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:389–395. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomanek RJ. Formation of the coronary vasculature during development. Angiogenesis. 2005;8:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s10456-005-9014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mu H, Ohashi R, Lin P, Yao Q, Chen C. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of coronary vessel development. Vasc Med. 2005;10:37–44. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm584ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai CL, Liang X, Shi Y, Chu PH, Pfaff SL, Chen J, et al. Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev Cell. 2003;5:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh H, Bradfute SB, Gallardo TD, Nakamura T, Gaussin V, Mishina Y, et al. Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12313–12318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132126100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laugwitz KL, Moretti A, Lam J, Gruber P, Chen Y, Woodard S, et al. Postnatal isl1+ cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature. 2005;433:647–653. doi: 10.1038/nature03215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou B, Ma Q, Rajagopal S, Wu SM, Domian I, Rivera-Feliciano J, et al. Epicardial progenitors contribute to the cardiomyocyte lineage in the developing heart. Nature. 2008;454:109–13. doi: 10.1038/nature07060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai CL, Martin JC, Sun Y, Cui L, Wang L, Ouyang K, et al. A myocardial lineage derives from Tbx18 epicardial cells. Nature. 2008;454:104–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinkel R, El-Aouni C, Olson T, Horstkotte J, Mayer S, Müller S, et al. Thymosin beta4 is an essential paracrine factor of embryonic endothelial progenitor cell-mediated cardioprotection. Circulation. 2008;117:2232–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.758904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lepilina A, Coon AN, Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Roberts RW, Burns CG, et al. A dynamic epicardial injury response supports progenitor cell activity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Cell. 2006;127:607–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bock-Marquette I, Saxena A, White MD, DiMaio JM, Srivastava D. Thymosin β4 activates integrin-linked kinase and promotes cardiac cell migration, survival and cardiac repair. Nature. 2004;432:466–72. doi: 10.1038/nature03000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smart N, Risebro CA, Melville AA, Moses K, Schwartz RJ, Chien KR, et al. Thymosin beta4 induces adult epicardial progenitor mobilization and neovascularization. Nature. 2007;445:177–82. doi: 10.1038/nature05383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu FX, Lin SC, Morrison-Bogorad M, Atkinson MA, Yin HL. Thymosin beta 10 and thymosin beta 4 are both actin monomer sequestering proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:502–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garner LB, Willis MS, Carlson DL, DiMaio JM, White MD, White DJ, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is a cardiac-derived myocardial depressant factor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:500–509. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00432.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mora CA, Baumann CA, Paino JE, Goldstein AL, Badamchian M. Biodistribution of synthetic thymosin b4 in the serum, urine, and major organs of mice. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1997;19:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0192-0561(97)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Runyan RB, Markwald RR. Invasion of mesenchyme into three-dimensional collagen gels: a regional and temporal analysis of interaction in embryonic heart tissue. Dev Biol. 1983;95:108–114. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blankesteijn WM, van Gijn ME, Essers-Janssen YP, Daemen MJ, Smits JF. Beta-catenin, an inducer of uncontrolled cell proliferation and migration in malignancies, is localized in the cytoplasm of vascular endothelium during neovascularization after myocardial infarction. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:877–883. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64601-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim KI, Cho HJ, Hahn JY, Kim TY, Park KW, Koo BK, et al. Beta-catenin overexpression augments angiogenesis and skeletal muscle regeneration through dual mechanism of vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated endothelial cell proliferation and progenitor cell mobilization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:91–98. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000193569.12490.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubota V, Kleinman HK, Martin GR, Lawley TJ. Role of laminin and basement membrane in the morphological differentiation of human endothelial cells into capillary-like structures. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1589–1598. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant DS, Kinsella JL, Fridman R, Auerbach R, Piasecki BA, Yamada V, et al. Interaction of endothelial cells with a laminin A chain peptide (SIKVAV) in vitro and induction of angiogenic behavior in vivo. J Cell Physiol. 1992;153:614–625. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041530324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wada AM, Reese DE, Bader DM. Bves: prototype of a new class of cell adhesion molecules expressed during coronary artery development. Development. 2001;128:2085–2093. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith TK, Bader DM. Characterization of Bves expression during mouse development using newly generated immunoreagents. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1701–1708. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu W, Guttentag S, Wang Z, Andl T, Ballard P, Lu MM, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling acts upstream of N-myc, BMP4, and FGF signaling to regulate proximal-distal patterning in the lung. Dev Biol. 2005;283:226–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin Y, White AC, Huh SH, Hilton MJ, Kanazawa H, Long F, et al. An FGF-WNT gene regulatory network controls lung mesenchyme development. Dev Biol. 2008;319:426–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamora M, Männer J, Ruiz-Lozano P. Epicardium-derived progenitor cells require beta-catenin for coronary artery formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18109–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702415104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blackshear PJ. The MARCKS family of cellular protein kinase C substrates. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1501–1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y, Davis HW. Thrombin-induced phosphorylation of the myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) protein in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1996;169:350–357. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199611)169:2<350::AID-JCP14>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartwig JH, Thelen M, Rosen A, Janmey PA, Nairn AC, Aderem A. MARCKS is an actin filament crosslinking protein regulated by protein kinase C and calcium-calmodulin. Nature. 1992;356:618–622. doi: 10.1038/356618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thelen M, Rosen A, Nairn AC, Aderem A. Regulation by phosphorylation of reversible association of a myristoylated protein kinase C substrate with the plasma membrane. Nature. 1991;351:320–322. doi: 10.1038/351320a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gliki G, Wheeler-Jones C, Zachary I. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent Akt/PKB activation and phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase-mediates PKC delta phosphorylation: role of PKC in angiogenesis. Cell Biol Int. 2002;26:751–759. doi: 10.1016/s1065-6995(02)90926-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rongish BJ, Torry RJ, Tucker DC, Tomanek RJ. Neovascularization of embryonic rat hearts cultured in oculo closely mimics in utero coronary vessel development. J Vas Res. 1994;31:205–215. doi: 10.1159/000159045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sosne G, Szliter EA, Barrett R, Kernacki KA, Kleinman H, Hazlett LD. Thymosin beta 4 promotes corneal wound healing and decreases inflammation in vivo following alkali injury. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:293–299. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sosne G, Qiu P, Christopherson PL, Wheater MK. Thymosin beta 4 suppression of corneal NFkappaB: A potential anti-inflammatory pathway. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:663–669. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhattacharya S, Macdonald ST, Farthing CR. Molecular mechanisms controlling the coupled development of myocardium and coronary vasculature. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;111:35–46. doi: 10.1042/CS20060003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.