SUMMARY

Large oligomeric portal assemblies play a central role in the life cycles of bacteriophages and herpesviruses. The stoichiometry of in vitro assembled portal proteins has been a subject of debate for several years. The intrinsic polymorphic oligomerization of ectopically expressed portal proteins makes it possible to form in solution rings of diverse stoichiometry (e.g. 11-mer, 12-mer, 13-mer, etc.) in solution. In this paper, we have investigated the stoichiometry of the in vitro-assembled portal protein of bacteriophage P22 and characterized its association with the tail factor gp4. Using native mass spectrometry, we show for the first time that the reconstituted portal protein assembled in vitro using a modified purification and assembly protocol, is exclusively dodecameric. Twelve copies of tail factor gp4 bind to the portal ring, in a co-operative fashion, to form a 12:12 complex of 1.050 MDa. We applied tandem mass spectrometry to the complete assembly and found an unusual dimeric dissociation pattern of gp4, suggesting a dimeric sub-organization of gp4 when assembled to the portal ring. Furthermore, native and ion mobility mass spectrometry reveal a major conformational change in the portal upon binding of gp4. We propose, that the gp4 induced conformational change in the portal ring initiates a cascade of events assisting in the stabilization of newly filled P22 particles, which marks the end of phage morphogenesis.

Keywords: bacteriophage P22, portal protein, viral assembly, gp4, mass spectrometry

Introduction

P22 is a short - tailed, double - stranded DNA bacteriophage of the Podoviridae family. The mature phage infects the gram-negative Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium 1, a common human pathogen that lives in the gut. The single particle asymmetric reconstruction of the phage P22 mature virion was recently reported 2; 3. The virus capsid, ~65 nm in diameter, shows an icosahedral organization, and it is built up by 415 copies of coat protein gp5. A unique pentameric vertex of the icosahedral capsid is replaced by the dodecameric portal protein (also called gp1), which provides a surface for attachment to the tail apparatus. Overall, the P22 tail, also referred to as the portal vertex structure, contains six molecules of the trimeric tailspike protein: gp9 4, and several copies of each of the three tail accessory proteins (also called “head completion proteins”): gp4, gp10 and gp26 5; 6; 7; 8. The portal ring facilitates packaging of DNA into the capsid by use of ATP hydrolysis 9. The P22 chromosome is introduced into the virion through the portal protein ring in an enzymatic reaction that requires the terminase subunits gp2 and gp3 10. During DNA packaging, the DNA is encapsulated inside the phage in a quasi-crystalline state at concentrations about 500 mg/ml 11; 12. The outer minor structural proteins, gp4, gp10, and gp26 are required for sealing the capsid as well as may play an important role in penetrating the host cell envelope 13; 14; 15.

Deletions in the genes encoding these factors do not affect assembly or packaging, but result in particles that leak their DNA into the surrounding media 16. Therefore, these proteins are not required for DNA packaging, but rather to seal the portal channel. The last protein to add to the nascent tail, the tailspike gp9, assembles as six trimers 17, which bind to the lipopolysaccharide protruding out from the outer lipid bilayer of the Salmonella cell envelope.

The exact mechanism of assembly of phage P22 tail is still not completely understood and it remains difficult to study this molecular machine in virtue of the large mass (~2.8MDa) and chemical complexity. To gain better insight, it is important to characterize the stoichiometry, oligomerization, and binding interactions between individual tail proteins. Mass spectrometry is an emerging tool for such an analysis. It has become a valuable addition to methods commonly used in structural biology. The coupling of gentle electrospray ionization with a time-of-flight detector (ToF) allows the analysis of non-covalent protein complexes in an environment where the proteins are likely to retain their quaternary conformation 18. In the nanoflow electrospray process the molecule of interest is gently transferred from an aqueous solution to the gas phase via protonation at atmospheric pressure 19. Desolvation of the protein assemblies in the ion source interface generates multiply charged ions of the intact complexes prior to analysis by the mass spectrometer. Recently, combinations of quadrupole and ToF analyzers (QToF) have been modified in such a way that the detectable mass range in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry exceeds several million Da, allowing the analysis of species as big as ribosomes and viruses 20; 21; 22; 23. Mass spectrometric detection of the assemblies has made it possible to obtain accurate information about protein complex stoichiometry, stability and dynamics 24; 25; 26, through which, for instance, the folding cycle of the GroEL-gp31 machinery could be monitored while folding the bacteriophage T4 capsid protein gp23 27. Macromolecular mass spectrometry lends itself as an excellent tool to study protein complex assembly; in particular virus assembly where major questions focus on the early multi-protein intermediates or the stoichiometries of subcomplexes, such as the portal protein.

In this paper, we have used mass spectrometry and other biochemical methods to examine the oligomerization of phage P22 portal complex and its interaction with the tail accessory factor gp4, which is known to have a role in portal protein closure. We show that the portal protein assembles uniquely into a dodecamer and that twelve gp4 bind to the portal ring, whereby the gp4 exhibits a dimeric sub-organization. Additionally, we showed with native mass spectrometry and ion mobility separation mass spectrometry that the binding of gp4 to the portal ring induces a major conformational change in the assembly, likely preparing the portal for further assembly with the tail accessory proteins.

Results

Oligomeric state of in vitro reassembled gp1 portal ring

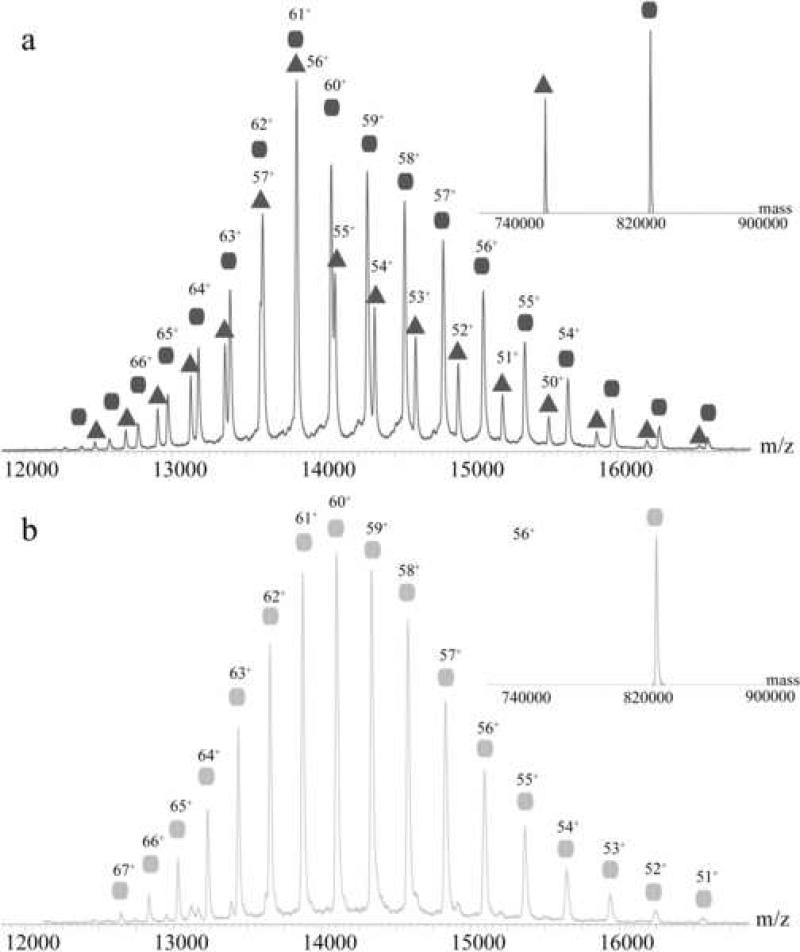

Ectopically expressed and reassembled portal proteins display significant structural polymorphisms in vitro. In the case of the phage P22 portal protein it was reported that the recombinant rings form undecamers and dodecamers in a ratio of approximately of 70:30 % 3; 28. It is plausible that those different quaternary states of assembly are due to the oligomerization procedure used during the purification. Therefore, the oligomeric state of the portal protein in vitro reflects likely both the intrinsic plasticity of the protein as well as the specific purification conditions used during reconstitution. To ensure complete, proper oligomerization of P22 portal protein we devised a novel strategy where portal protein monomers were concentrated to >200 mg/ml (2.2 mM) in 60 mM EDTA and subjected to heat shock at 37 C° followed by ultracentrifugation to remove precipitation products. This procedure led to a single, distinct oligomeric state of the portal complex as evidenced by native mass spectrometry. In native mass spectrometry the transfer of the protein into the gas phase via electrospray ionization of the mass spectrometer involves protonation and leads to the presence of the protein in different charge states. From the consecutive ion signals, the charge state can be determined, which makes it possible to determine exact masses of the sample of interest. Figure 1 shows native mass spectra of the portal ring (the charge state is indicated above the corresponding ion signal). We measured samples derived from the old strategy as reported 3; 28 (figure 1a) and purifications treated as described above (figure 1b). The samples prepared by the original method showed still undecameric portal ring with a mass of 761.2 ± 0.2 kDa. The ratio between the undecamer and the dodecamer in the sample was 40:60 %. The portal protein, assembled as described here, was unambiguously shown to be dodecameric (figure 1b). The total mass measured for the latter complex was 830.2 ± 0.2 kDa in agreement with twelve copies of 69.2 kDa (predicted from the sequence).

Figure 1. Mass spectrometric analysis of oligomeric P22 portal protein.

Figure (a) shows the portal purified and assembled according to previous literature 3; 28. The triangles indicate the distribution originating from the undecameric portal ring and the circles indicate the distribution originating from the dodecameric portal ring. The charge state is indicated above the corresponding peaks. Figure (b) shows the portal purified as described in this article. The homogeneous distribution originates from dodecameric portal ring. The charge state is indicated above the corresponding peak. The insets show convoluted mass spectra, representing the abundance of the different species/distributions.

Twelve copies of full-length gp4 oligomerize onto the portal ring

Gp4, an 18.3 kDa P22 - encoded protein, is the first tail factor binding to the nascent tail during virus morphogenesis 16. Olia et al. reported that gp4 exists as a monomer in solution 29, which is highly sensitive to temperature denaturation. As detected by mass spectrometry, purified gp4 at a final concentration of 10 μM in 100 mM ammonium acetate is mainly monomeric. About 8 % was detected as a dimer of gp4, possibly a high concentration artifact, but no higher oligomerization states were observed (data not shown).

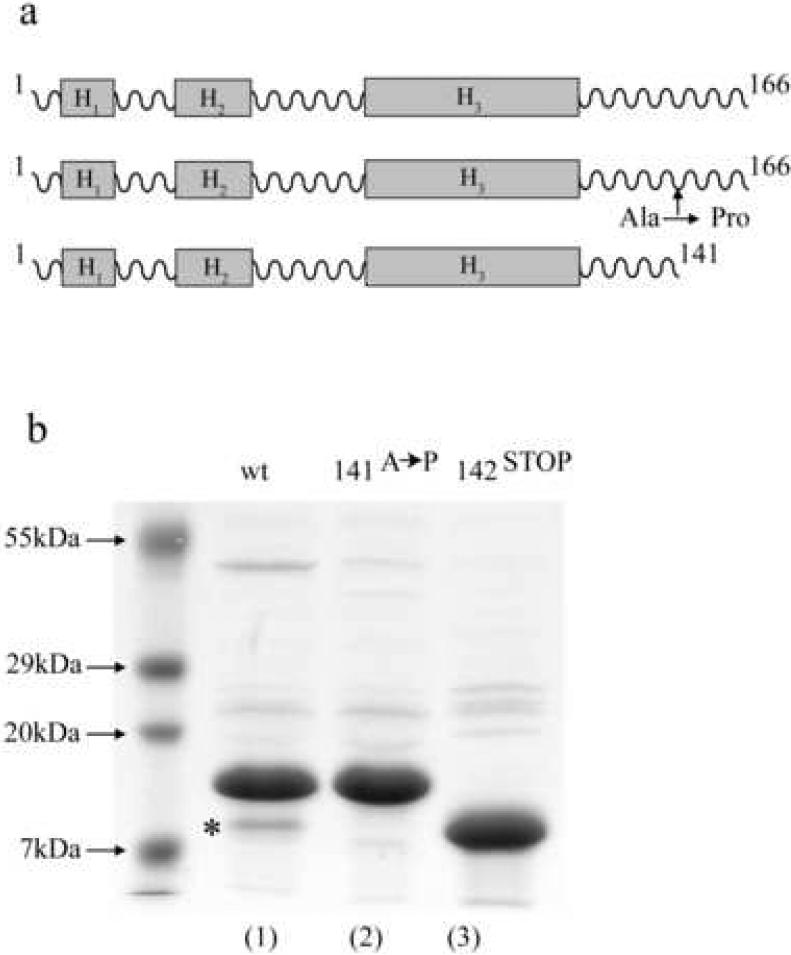

To further characterize the assembly of recombinant gp4 to dodecameric portal protein, a portal:gp4 complex was formed in the presence of a 3-fold excess of gp4. The excess gp4 was separated from the portal:gp4 complex using gel filtration chromatography. The sample was stored at 4 °C prior to analysis. Homogeneously reassembled portal:gp4 complex was buffer exchanged against 100 mM ammonium acetate buffer pH 6.8 and the sample was directly introduced into the mass spectrometer at a concentration of 0.8 μM. The assembly appeared to be very heterogeneous with mass differences among the different species of 2.8 kDa. Since the portal assembly showed a homogeneous dodecamer when analyzed individually (Figure 1b), we concluded that the heterogeneity seen in the portal:gp4 complex originated from degradation products of gp4, which retain the ability to bind to the portal ring, or possibly get degraded after the assembly. To test this hypothesis we first determined the exact mass of the putative gp4 degradation products. This was done by dissolving the portal:gp4 complex in 50% acetonitrile, 0.2% acetic acid. Under these conditions the complex falls apart, the proteins unfold and are able to gain more charges during the electrospray process, which results in more and narrower peaks, allowing a more precise determination of the monomeric mass. The measurements under denaturing conditions showed that there were two forms of gp4 present in the complex: the expected complete protein with a mass of 18,383 ± 1 Da and a truncated form with a lower mass of 15,570 ± 1 Da. The difference in mass of 2,813 Da fitted to the difference detected in the assemblies of the portal with the wt gp4 (data not shown). With such accurate masses of the monomeric protein, we were able to determine that a unique cleavage event takes place in gp4 between Ala141 and Asp142 (figure 2a).

Figure 2. Design of gp4 constructs with altered C-terminal region.

(a) Schematic diagram of gp4 predicted structural topology and the two constructs designed in this study. (b) SDS-PAGE of purified wild type gp4 and the two constructs gp4-142STOP and gp4-141A→P. The asterisk in lane 1 indicates the degradation product at position 142, which yields a product of identical size as the construct gp4-142STOP.

The C-terminal moiety (res. 141-166) of gp4 is dispensable for binding to the portal ring

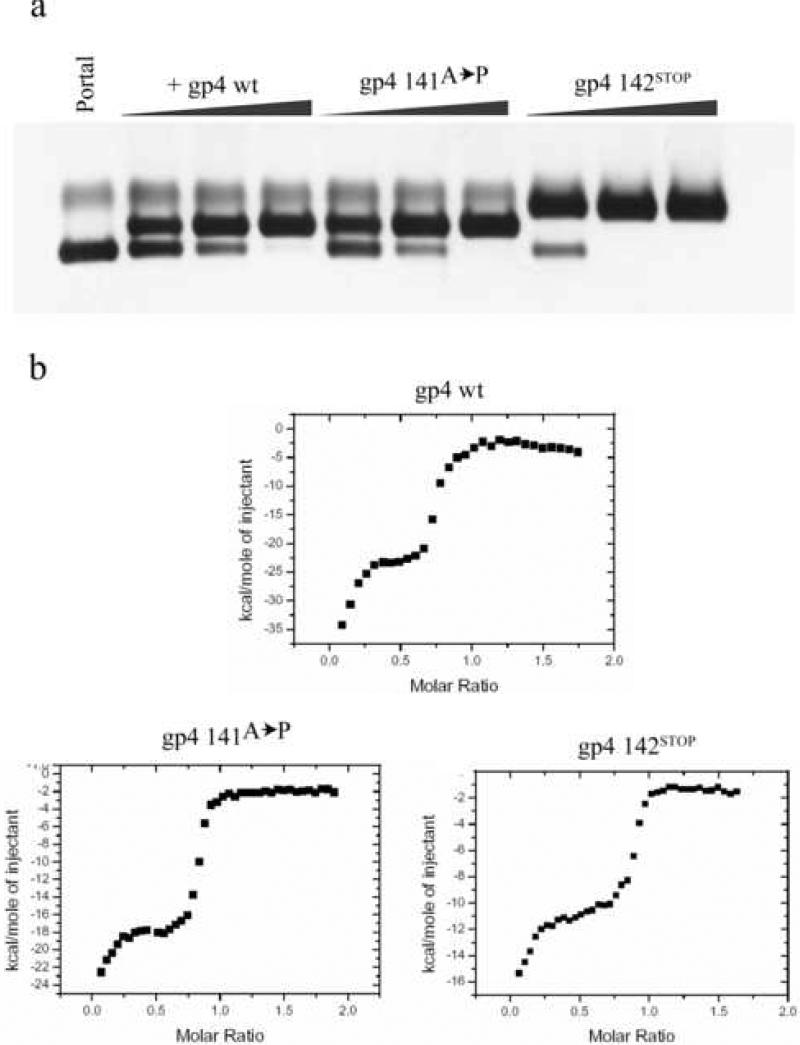

The idea that the C-terminal tail of gp4 is dispensable for binding to the portal ring was further investigated by engineering two new constructs of gp4. In the first mutant, we sought to reduce the flexibility at position 142 of gp4, which likely causes the protein to be degraded. Alanine 141 was therefore mutated to proline, which is a less flexible amino acid 30 (gp4-141A→P). In the second mutant, we deleted the entire C-terminus of the protein ending with amino acid 141 (gp4-142STOP). Both gp4 constructs were expressed and purified to homogeneity (figure 2b). To test whether the two mutants exhibit similar binding behavior as the wild type gp4 we titrated the two gp4 mutants into the dodecameric portal ring and analyzed the formation of a portal:gp4 complex by native electrophoresis on agarose gels. Similar to wild type gp4, the two gp4 variants showed uniform and saturable binding to the dodecameric portal ring when 12 equivalents of gp4 were added to a dodecameric portal protein ring (figure 3A). Interestingly, the shorter deletion construct gp4-142STOP shifted the portal ring to a greater degree than the wt or the gp4-141A→P mutant. This increased shift could be indicative of either simply a difference in exposed charges (due to the truncated residues), or possibly, the formation of a different final product. To determine the binding behavior more precisely as well as to confirm that the behavior of gp4-142STOP was not due to any differences in binding, we carried out isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments, where either purified gp4 or gp4-mutants were titrated into a cell containing homogeneous dodecameric portal rings at an oligomer concentration of 6.6 μM (figure 3B-D). The results showed that there are no significant differences in the binding. Both mutants and wild-type gp4 show the same bi-modal binding characterized by a first weak interaction followed by a second stronger interaction as reported previously 29. This indicated that the increased retardation by gp4-142STOP on the native agarose gel is likely due to the removal of charged residues in the truncated C-terminal.

Figure 3. Biochemical analysis of gp4 and gp4 mutants binding to the portal ring.

(a) Native agarose gel of different gp4 mutants binding to the portal ring. The portal ring is on the first lane, followed by titrations of the different gp4 constructs as indicated above the lanes. There is a uniform binding for all different gp4 to the portal ring as confirmed by ITC. The slower migration of the portal ring:gp4-142STOP is likely due to fewer charges on the surface of the assembly. (b) Integrated peak heights from ITC isotherms obtained by injecting gp4-wt, gp4-141A→P, or gp4-142STOP into a solution of dodecameric portal protein. All three binding isotherms clearly demonstrate similar binding reactions, which strengthen the idea the C-terminus of gp4 is dispensable for assembly to portal protein.

Stoichiometry of portal protein bound to gp4-141A→P and gp4-142STOP

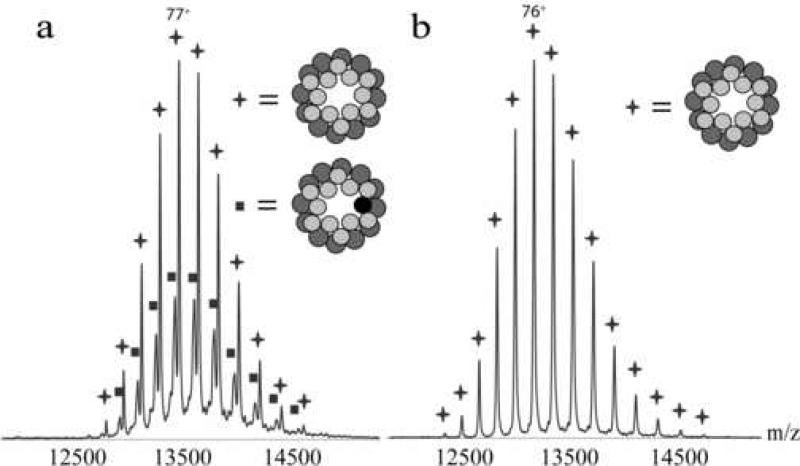

We next investigated the portal:gp4-141A→P and the portal:gp4-142STOP assemblies by mass spectrometry. The complexes were stored at 4 °C after formation until the measurement. Directly before introducing the samples into the mass spectrometer they were buffer exchanged in ultrafiltration units against 100 mM ammonium acetate pH 6.8. The results of the measurements are shown in figure 4. The portal:gp4-141A→P assembly showed clear binding of twelve gp4-141A→P to the dodecameric portal ring. There are two major species visible in the spectrum. One originates from twelve complete gp4-141A→P proteins (18,336 ± 3 kDa) binding to the dodecameric portal and the second is eleven complete gp4-141A→P and one truncated gp4-141A→P binding to the dodecameric portal, which is 2.8 kDa smaller. This becomes evident from the two distributions visible in the spectrum. The larger complex has a mass of 1,050.7 ± 0.3 kDa, which coincides with the mass of twelve times portal protein (69.2 kDa) and twelve times gp4-141A→P. The minor distribution has a mass 1,047.9 ± 0.2 kDa, which is about 2.8 kDa smaller. This mass difference was already encountered when the measurements on the portal assembled with gp4 wt were done. Additional mass spectrometric experiments confirmed that the mass difference was again due to degradation of gp4. However, this sample was less heterogeneous compared to the portal protein bound to wt gp4, which showed up to six truncated wt gp4 binding to the dodecameric portal. Here only one truncated gp4-141A→P was detected. In the mutant, the distribution with the degraded gp4 bound is less than 30 % of the total distribution, indicating that the mutation 141A→P had effectively reduced the flexibility of gp4, and consequentially, its degree of proteolysis. Next the stoichiometry of the portal:gp4-142STOP complex was determined. The spectrum showed a single distribution with a mass of 1,016.5 ± 0.3 kDa, which is in good agreement with the predicted mass of a dodecamer of portal protein bound to twelve gp4-142STOP (15,498 ± 3 kDa).

Figure 4. Mass spectra of the portal ring bound to gp4 C-terminal mutants.

(a) Distributions of the gp4-141A→P bound to the portal ring. Marked with squares are the charge states of the assembly where eleven complete and one truncated gp4-141A→P are bound to the dodecameric portal ring. The stars show the distribution of twelve complete gp4-141A→P bound to the portal ring. (b) In the assembly of the gp4-142STOP with the portal ring are no truncation products of the gp4-142STOP present. The stars indicate the charge states of the complex with twelve gp4-142STOP bound to the dodecameric portal ring. The blue circles in the schematic figures indicate the portal protein and the green circles indicate gp4, an orange circle indicates the truncated form of gp4. The charge state of the most intense peak is indicated above each distribution. The dark grey circles in the schematic figures indicate the portal protein and the light grey circles indicate the gp4 mutants. The black circle indicates the truncated gp4-141A→P.

Mass spectrometry reveals no intermediate state in the assembly of gp4 to the portal

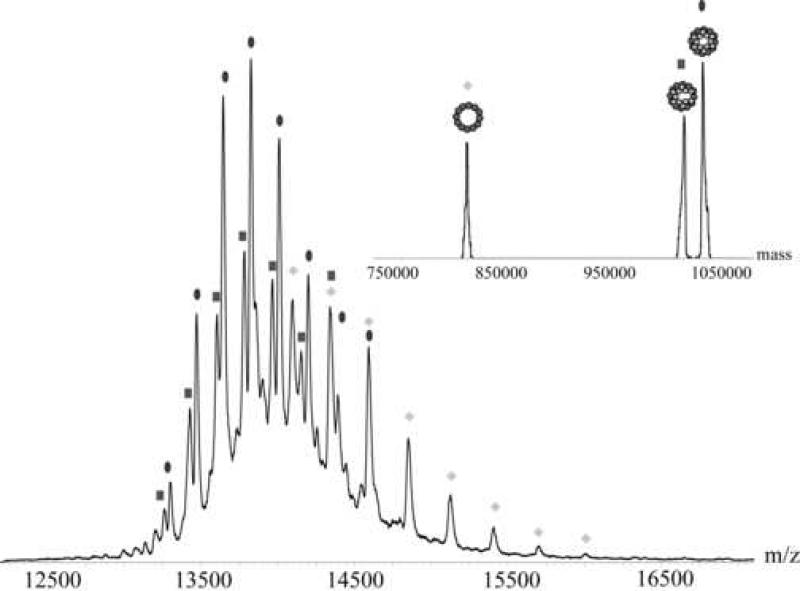

It has been reported before that the binding of gp4 to the portal ring may proceed through formation of an assembly intermediate, which contains 4-6 copies of gp4 bound to the dodecameric portal ring 29. This putative (portal protein)12:(gp4)4-6 assembly intermediate was identified on agarose gel based on its altered migration and was found to be strongly temperature dependent. We assembled the portal ring with wt gp4 directly before the mass spectrometric measurement in different ratios, starting at a ratio of 1:2 and up to an excess of 5 equivalents of portal protein per copy of gp4. When stoichiometric amounts of gp4 were added to the portal, the favored stoichiometry detected by mass spectrometry was twelve copies of gp4 binding to a dodecamer of portal protein. There were minor distributions visible showing eleven copies of gp4 binding to the portal ring. When sub-stoichiometric amounts of gp4 were added to the dodecameric portal ring the main distribution was still the 12:12 (portal protein:gp4) assembly with minor distributions of 12:11. At those concentrations, there was also free portal ring present, however no intermediate with a 12:6 or 12:4 (portal protein:gp4) stoichiometry (figure 5). These data suggest that under the experimental conditions used here the putative assembly intermediate is not detected. This may reflect the instability of the intermediate. Alternatively, the putative band seen by Olia et al. on agarose gels and thought to be a portal:gp4 intermediate represents some different oligomeric species than the expected intermediate.

Figure 5. Addition of gp4 to the portal ring in a ratio of 1:3 (gp4:gp1).

The mass spectrum shows mainly three distributions belonging to the free portal ring (diamonds), the complex where twelve gp4 are bound to the portal ring (ellipse) and the distribution originating from the assembly where eleven gp4 are bound to the portal ring (squares). The dark grey circles in the schematic figures indicate portal protein and the light grey circles indicate gp4. The inset shows a convoluted mass spectrum.

Dissociation of the portal:gp4 complex reveals a dimeric structural organization of gp4

We applied tandem mass spectrometry to the portal ring and the complex of the portal ring with twelve gp4 bound to it. As mentioned above and labeled in figure 1, the transfer of proteins into the mass spectrometer and the protonation lead to the presence of the protein in different charge states. Tandem mass spectrometry allows selection of one charge state, which can be collisionally activated in the mass spectrometer, resulting in mass-selected dissociation of precursor ions. In these experiments, the precursor ions generally eliminate a single subunit, which is thought to unfold and thus to become highly charged, combined with the formation of the relatively low charged complex lacking the eliminated subunit 31. Evidently, the summed mass and charge of the two formed fragment ions should add up to the mass and charge of the precursor. When we selected one of the charge states of the dodecameric portal ring as the precursor, we saw the sequential dissociation of up to two monomeric subunits, resulting in the formation of undecameric and decameric portal assemblies, as expected. However, when we applied these measurements to the different assemblies of the portal ring with the gp4, both wt and mutants, they all showed an uncommon dissociation behavior next to the usual elimination of a single subunit. The known behavior resulted in the elimination of a monomeric subunit (labeled with a circle in figure figure 6) and formation of a complex of 12:11 portal:gp4-142STOP (labeled with triangles in figure 6). Additionally, an uncommon dissociation behavior was detected, the elimination of a dimer (labeled with double circles in figure 6) from the portal:gp4-142STOP complex and concomitant formation of 12:10 portal:gp4-142STOP (labeled as squares in figure 6). This finding is very interesting as it gives additional information about the interactions between the involved proteins.

Figure 6. Tandem mass spectrum of the gp4-142STOP bound to dodecameric portal ring (charge state 76+).

On the left side of the spectrum the eliminated gp4-142STOP monomer (circles) and dimer (double circles) are visible; in the middle the precursor is indicated; the right side of the spectrum shows the distributions of the concomitant high mass fragments where either the monomer (triangles) or the dimer (squares) was eliminated. The high and low m/z area are magnified fifty fold as indicated. The dark grey circles in the schematic figures indicate portal protein and the light grey circles indicate gp4-142ST0P.

Gp4 binding induces a major conformational change in the dodecameric portal

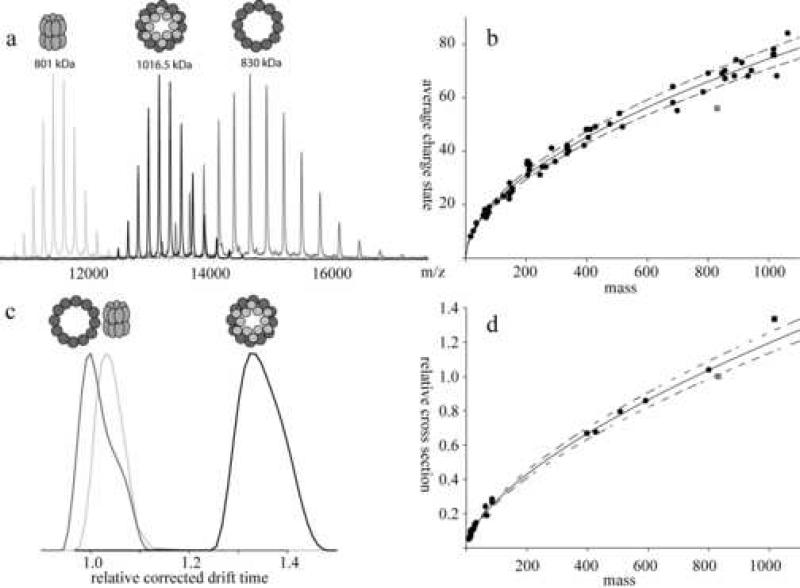

The amount of charges a protein gathers during the electrospray process, used in native mass spectrometry, is dependent on the buffer conditions, the hydrophobicity and the general conformation of the protein. The amount of charges depends highly on the presence of charged amino acids (basic and acidic) at the surface of the protein/protein complex. It has been reported that the average amount of charges a globular protein or protein complex obtains during the electrospray process under native conditions can be estimated by the formula: z = 0.078 × (m)1/2 [eq. 1] 32, where z is the charge of the complex and m is the mass. In figure 7b a plot is made of the experimentally measured average charge state of a whole range of proteins and protein complexes measured under similar conditions versus the molecular mass of globular proteins/protein complexes. Using eq. 1 the calculated average charge state of the portal is expected to be 71. The measured charge distribution of the portal is quite broad, but has a most abundant charge state of 60, an unusual large difference of about 11 charges. The average charge state for the three measured portal:gp4 assemblies, is 76 – 77, in fair agreement with the predicted average of 79 – 80. The measured deviation in charge observed for the portal is quite pronounced, as can be seen in figure 7b, where it deviates strongly from all other data points. To illustrate this deviation more clearly we overlaid in figure 7a the experimental spectra of GroEL, the portal ring and the portal:gp4-142STOP assembly. GroEL, which is similar in mass to the portal ring, the measured charge states matches the predicted value. As expected, and predicted by eq. 1, the portal:gp4-142STOP assembly attains more charges than GroEL, just by the fact that it is larger. The outlier is the free portal, which attains relatively few charges in the electrospray process, shifting its appearance in the mass spectra to m/z values not only higher than those of GroEL, but even higher than the portal:gp4-142STOP assembly (see figure 7a). From this data we speculate that the free portal has a more compact structure, whereby likely several potentially charged residues, are buried inside the structure. Upon binding of gp4, the portal undergoes a major conformational change, whereby such charged residues become exposed, and thus charged in the electrospray process. So next to direct changes in the portal:gp4 interface region we predict conformational changes in other regions of the portal ring, possibly preparing the portal for further assembly or DNA binding.

Figure 7. Comparison between the portal ring and the portal:gp4-142STOP assembly.

(a) An overlay of mass spectra from GroEL (light gray), dodecameric portal ring (gray) and the assembly of the dodecameric portal ring to gp4-142STOP (black). Even though the mass of the assembly is 186 kDa higher than the portal ring alone, the distribution shifts to a lower m/z indicating a major conformational change. GroEL has a similar mass as the portal ring and represents a typical charge distribution for a protein of that mass. (b) Curve fit representing the predicted average charge state of a protein complex. The circles are proteins used to generate the fit, the light gray square represents the portal ring and the black square the portal:gp4-141A→P. The solid line represents the fit through the standard proteins, the dashed line indicated the 5 % deviation interval from the expected result. (c) Mass and charge corrected drift times for GroEL (light gray), the dodecameric portal ring (dark gray) and the portal:gp4-141A→P assembly (black). (d) Calculated relative cross sections of proteins and protein complexes (circles), the cross section of portal:gp4-141A→P (black square) and the dodecameric portal ring (gray square). All these relative cross-sections were scaled to the portal ring. The solid line represents the fit through the set of standard proteins and protein complexes, the dashed line indicates the 5 % deviation interval.

We further investigated this conformational change using ion mobility separation mass spectrometry (IMS). In IMS the ions are separated by their mass to charge ratio like in conventional mass spectrometers, but IMS additionally allows separation of the ions dependent on their drift time. Molecules with compact surfaces have a shorter drift time than molecules with a large cross section, assuming they have the same mass. Thus, with the drift time of a certain complex, predictions can be made about their relative cross sections, if the measurements are corrected for mass and charge state (see material and methods). In figure 7c the mass and charge corrected drift times are depicted for GroEL, the portal and the portal:gp4-142STOP assembly. It is interesting to note that the free portal has a lower cross-section than GroEL, even while it is “bigger” in mass, validating a rather compact structure for the free portal. From such data relative cross sections can be derived 33. We determined cross-sections for a range of proteins and protein complexes. In figure 7d the determined relative cross-section of all these proteins and protein complexes are plotted versus their mass. It can be seen, in agreement with previously reported data 34, that there is a correlation between the mass and the determined cross-section. However, the portal ring and the portal:gp4 assemblies do not fit in the calculated correlation. Whereas the determined cross-section for the portal ring lies below the trend-line, the determined cross-section for the portal:gp4-142STOP assembly is found above the trend-line (see figure 7d). Both, the unusual behavior during the electrospray process and the deviations in cross sections, hint at a major conformational change occurring in the portal ring upon gp4 binding.

Discussion

Characterizing the assembly of bi-dodecameric portal protein:gp4 complex

Portal proteins are oligomeric molecular machines that have been shown to reassemble into polymorphic rings of diverse stoichiometry in vitro. For instance, phage SPP1 portal is dodecameric in the mature phage 35, but forms tridecamers when reassembled in vitro. Likewise phage P22 portal appears as dodecameric both in the asymmetric reconstruction of the mature virion 3, and in the crystal of the isolated portal connector 36, but was found to form undecamer and dodecamer when reassembled in vitro 28.

Using mass spectrometry, we show that the discrepancy between the in vitro versus the in vivo assembled portal rings is due to the assembly process utilized during purification. Consequently, optimization of the protocol leads to homogeneous dodecameric portal rings.

We have used the physiologically significant dodecamer to study the assembly of gp4, the tail factor known to initiate portal protein closure 16. Gp4 is mainly monomeric in solution and binds the portal ring in a 1:1 (or 12:12) stoichiometry. Gp4 displays identical binding affinity for full length and the C-terminally deleted portal protein Δ602, which the C-terminus of portal protein is not required for binding to gp4. This agrees well with the observation that in vivo, the carboxyl terminal end of portal protein is dispensable both for assembly into the virion as well as virus infectivity 37. Gp4 also assembles to portal protein in its degraded form. A C-terminal deletion construct of gp4 lacking residue 142-166 displays wild type binding to portal protein, suggesting out a dispensable role of this region of the gp4 in binding to portal protein. When we assembled wt gp4 directly with the portal ring, we could not see any degradation products of the gp4 (see also figure 5). In contrast to this the sample of portal:gp4 wt which was preassembled and stored at 4 °C until measurement in the mass spectrometer showed heavy degradation. This is suggesting that the cleavage of gp4, which we have seen before, happens after the assembly is finished.

Tandem mass spectrometry revealed the dissociation of a gp4 dimer from the portal:gp4 complex. Elimination of protein dimers is rarely observed in tandem mass spectrometry of protein complexes, since subunits often unfold upon dissociation. To our knowledge there are only two examples in literature where a dimer elimination from a macromolecular complex has been described 21; 38. The observation of gp4 dimers dissociating from the assembly strongly hints at a non-uniform binding of gp4 to the portal ring and indicates a dimeric structural organization of gp4 when bound to the portal. The idea of a dimeric gp4:gp4 interface agrees well with the symmetry mismatches observed in P22 tail, where a dodecamer of gp4 attaches a hexamer of gp10 39.

It has been suggested that the association of gp4 to dodecameric portal protein proceeds via formation of an assembly intermediate formed by portal ring occupied by 4-6 gp4 equivalents 40. In this study, we added gp4 to the assembled portal ring just prior to measurement to determine the stoichiometry of the precomplex. In our experiments, however, we did not see an intermediate binding state. When gp4 was added to the portal ring in substoichiometric amounts only assemblies of 12:11 or 12:12 of portal protein to gp4 and free portal ring was present. We could show that this 1:2 (gp4:gp1) stoichiometry is not a stable intermediate state that occurs when substoichiometric amounts of gp4 are titrated to the portal, but that rather a complete assembly takes place leaving free portal ring behind. The fact that the assembly is complete within a minute even at low concentrations of gp4 supports a cooperative form of binding of the tail accessory factor gp4 to the portal ring. We cannot completely exclude that an intermediate binding state exists, since it has been shown that this intermediate is very temperature sensitive and the conditions for the mass spectrometric measurements do not allow to keep the temperature stable at 30 °C, temperature at which the intermediate is populated .

Is the gp4-induced conformational change of the portal the missing link in head closure?

There have been ongoing discussions on how the DNA enters the phage head, how the phage closes off and the structure of the tail complex. It is as important to question how the DNA will leave the capsid and to understand how this process is regulated. The work presented here provides new insights in the functioning and interaction of the portal ring with tail accessory factor gp4. Upon packaging of the DNA into the head, the pressure exerted by the DNA highly condensed into the capsid increases accordingly. Gp4 is the first tail factor to initiate portal protein closure, which also requires tail accessory factors gp10 and gp26 16. Our data suggests that gp4 induces a conformational change in portal protein upon assembly, which likely stabilizes a closed conformation of portal protein, competent for assembly to the other tail factors. Further structural investigation by cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography will be critical to delve into the nature of the gp4-induced conformational change in portal protein and its functional role in the stabilization of newly filled phage P22 heads.

Material and Methods

Expression, purification of recombinant proteins

Recombinant proteins were expressed in E. coli (strain BL21) cells in LB broth supplemented with 2.5 g/l glucose. After growth at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6, gp4 or gp1 (portal protein) expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG and the culture was incubated, shaking at 22 °C for 16 h. For gp4, the cells were collected and lysed by sonication in Lysis Buffer (250 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME)) plus various protease inhibitors. Gp4, fused to an N-terminal-6xHis tag, was purified by metal chelating affinity chromatography using Qiagen Nickel-NTA beads. Typically, one liter of E. coli yielded about 5 mg of pure gp4, which was concentrated to approximately 50 mg/ml using a Millipore-Amicon concentrator (MW cutoff 10 kDa). Freshly eluted and concentrated protein was further purified by gel filtration on a Superdex S-200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in Gel Filtration Buffer (200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 3 mM β-ME, 0.1 mM PMSF). Calibration of the S-200 column was carried out using high molecular weight globular protein standards (BioRad). Gp4 C-terminal mutants, gp4-142STOP and gp4-141A→P, were made by introduction of a nonsense mutation at position 142 in the case of gp4-142STOP and an alanine to proline mutation at position 142 in the case of gp4-141A→P using the Qiagen Quikchange Mutagenesis Kit. All plasmids were sequenced to confirm the fidelity of the gene. Mutated proteins were expressed and purified according to the same protocol as wild-type gp4.

Recombinant untagged portal protein was expressed and purified using a protocol modified from 29. After induction, cells containing recombinant portal protein were lysed in 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM β-ME. The lysed cells were centrifuged at 20,000 × g and the supernatant was recovered. Solid ammonium sulfate was added to 30 % saturation, and after 1 h incubation, the solution was centrifuged at 18,000 × g. The resulting pellet contained relatively pure portal protein, which was then resuspended and immediately desalted using a Bio-Rad Desalting Column into 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM β-ME, 60 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. The desalted protein was then concentrated to >200 mg/ml and incubated at room temperature for 48 h. This resulted in a dramatic enrichment of higher-order oligomers of the portal protein. The protein was then incubated at 37 °C for 3 h, during which massive precipitation occurs. The protein was clarified by a single round of ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 35 min. This procedure results in the prodution of homogenous dodecameric portal protein, as confirmed by native agarose gel as well as mass spectrometry.

Native Agarose Gel Electrophoresis and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Native agarose gel electrophoresis was carried out as described in 29. Protein samples and mixtures were allowed to incubate for 1 h at room temperature before analysis on agarose gel. For ITC (Isothermal Titration Calorimetry) experiments, all samples were dialyzed extensively against 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 2 mM β-ME buffer prior to each experiment. ITC experiments were carried out at 30 °C using a 300 μL syringe with a rotation speed of 295 rpm in the VP-ITC (Microcal, Northampton, MA). Gp4 (wild-type, gp4-141A→P or gp4-142STOP) was injected in 5 μL increments at a concentration of 245 μM into 1.8 ml of portal protein at an oligomer concentration of 6.6 nM with a spacing of 360 seconds between consecutive injections. Titration data were analyzed using the Origin 7.0 data analysis software (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA).

Mass spectrometry measurements

The sample buffer was exchanged five times to 100 mM ammonium acetate pH 6.8 using centrifugal filter units with a cut-off of 5 kDa (Millipore, UK). The concentration used for the mass spectrometry measurements was ~10 μM (based on monomeric masses). The samples were measured on a LCT for the denaturing conditions and on a modified Q-ToF (Quadrupole - Time of Flight) for native mass spectrometry and tandem mass spectrometry 21

(Waters, UK). Nanospray glass capillaries were used to introduce the samples into the Z-spray source. The source pressure was increased to 10 mbar to create increased collisional cooling 41; 42. Source temperature was set to 80 °C and sample cone voltage varied from 125 to 175 V. Needle voltage was around 1300 V in case of the LCT and around 1600 V for the Q-ToF. For the tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) measurements, precursor ions of specific m/z were selected in the quadrupole. Subsequently, they were accelerated through the collision cell applying voltages from 0 to 200 V over this cell. Xenon was used as collision gas in the MS/MS experiments to increase ion transmission and energy transfer efficiency during the process 38. Pressure conditions were 1.5 × 10−2 mbar in the collision cell and 2.3 × 10−6 mbar in the ToF.

Ion mobility separation (IMS) measurements were carried out on a Synapt HDMS (Waters, UK)33. The source pressure was set to 6.9 mbar, the pressure in the trap was 2.9 × 10−2 mbar, 0.5 mbar in the IMS cell and 2.7 × 10−6 mbar in the ToF. The wave ramp in the IMS cell was set from 7 to 30 V and the wave velocity to 250 m/s. The gas used in the trap was xenon 43 and nitrogen in the IMS cell. Needle voltage was 1.3 kV and cone voltage 175 V. The comparison of the cross sections was based on the following formula: where Ω is the relative cross section, tD is the drift time, z is the charge state, mion is the mass of the ion and mgas is the mass of the target gas in the IMS cell. TD was corrected before for the retention time of the ions in the transfer cell and the field free region between the transfer cell and the pusher.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Netherlands Proteomics centre for funding.

References

- 1.Israel JV, Anderson TF, Levine M. in vitro MORPHOGENESIS OF PHAGE P22 FROM HEADS AND BASE-PLATE PARTS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967;57:284–291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.57.2.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang J, Weigele P, King J, Chiu W, Jiang W. Cryo-EM asymmetric reconstruction of bacteriophage P22 reveals organization of its DNA packaging and infecting machinery. Structure. 2006;14:1073–82. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lander GC, Tang L, Casjens SR, Gilcrease EB, Prevelige P, Poliakov A, Potter CS, Carragher B, Johnson JE. The structure of an infectious P22 virion shows the signal for headful DNA packaging. Science. 2006;312:1791–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1127981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldenberg D, King J. Trimeric intermediate in the in vivo folding and subunit assembly of the tail spike endorhamnosidase of bacteriophage P22. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:3403–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.11.3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casjens S, King J. P22 morphogenesis. I: Catalytic scaffolding protein in capsid assembly. J Supramol Struct. 1982;2:202–24. doi: 10.1002/jss.400020215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartweig E, Bazinet C, King J. DNA injection apparatus of phage P22. Biophys. J. 1986;49:24–26. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(86)83579-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lander GC, Tang L, Casjens SR, Gilcrease EB, Prevelige P, Poliakov A, Potter CS, Carragher B, Johnson JE. The Structure of an Infectious p22 Virion Shows the Signal for Headful DNA Packaging. Science. 2006 doi: 10.1126/science.1127981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang L, Marion WR, Cingolani G, Prevelige PE, Johnson JE. Three-dimensional structure of the bacteriophage P22 tail machine. Embo J. 2005;24:2087–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DE, Tans SJ, Smith SB, Grimes S, Anderson DL, Bustamante C. The bacteriophage phi 29 portal motor can package DNA against a large internal force. Nature. 2001;413:748–752. doi: 10.1038/35099581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casjens S, Weigele P. In: Headful DNA packaging by bacteriophage P22. in Viral Genome Packaging. Catalano C, editor. Landes Publishing; 2004. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith DE, Tans SJ, Smith SB, Grimes S, Anderson DL, Bustamante C. The bacteriophage straight phi29 portal motor can package DNA against a large internal force. Nature. 2001;413:748–52. doi: 10.1038/35099581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earnshaw WC, Casjens SR. DNA packaging by the double-stranded DNA bacteriophages. Cell. 1980;21:319–31. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moak M, Molineux IJ. Peptidoglycan hydrolytic activities associated with bacteriophage virions. Molecular Microbiology. 2004;51:1169–1183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrews D, Butler JS, Al-Bassam J, Joss L, Winn-Stapley DA, Casjens S, Cingolani G. Bacteriophage P22 tail accessory factor gp26 is a long triple-stranded coiled-coil. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:5929–5933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400513200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhardwaj A, Olia AS, Walker-Kopp N, Cingolani G. Domain Organization and Polarity of Tail Needle GP26 in the Portal Vertex Structure of Bacteriophage P22. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;371:374–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strauss H, King J. Steps in the stabilization of newly packaged DNA during phage P22 morphogenesis. J Mol Biol. 1984;172:523–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(84)80021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinbacher S, Miller S, Baxa U, Budisa N, Weintraub A, Seckler R, Huber R. Phage P22 tailspike protein: Crystal structure of the head-binding domain at 2.3 angstrom, fully refined structure of the endorhamnosidase at 1.56 angstrom resolution, and the molecular basis of O-antigen recognition and cleavage. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1997;267:865–880. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benesch JL, Aquilina JA, Ruotolo BT, Sobott F, Robinson CV. Tandem mass spectrometry reveals the quaternary organization of macromolecular assemblies. Chem Biol. 2006;13:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fenn JB, Mann M, Meng CK, Wong SF, Whitehouse CM. Electrospray ionization for mass spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science. 1989;246:64–71. doi: 10.1126/science.2675315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobott F, Hernandez H, McCammon MG, Tito MA, Robinson CV. A tandem mass spectrometer for improved transmission and analysis of large macromolecular assemblies. Anal Chem. 2002;74:1402–7. doi: 10.1021/ac0110552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Heuvel RH, van Duijn E, Mazon H, Synowsky SA, Lorenzen K, Versluis C, Brouns SJ, Langridge D, van der Oost J, Hoyes J, Heck AJ. Improving the performance of a quadrupole time-of-flight instrument for macromolecular mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2006;78:7473–83. doi: 10.1021/ac061039a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bothner B, Siuzdak G. Electrospray ionization of a whole virus: Analyzing mass, structure, and viability. Chembiochem. 2004;5:258–260. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benjamin DR, Robinson CV, Hendrick JP, Hartl FU, Dobson CM. Mass spectrometry of ribosomes and ribosomal subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7391–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heck AJR, van den Heuvel RHH. Investigation of intact protein complexes by mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 2004;23:368–389. doi: 10.1002/mas.10081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loo JA. Studying noncovalent protein complexes by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 1997;16:1–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2787(1997)16:1<1::AID-MAS1>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Heuvel RH, Heck AJR. Native protein mass spectrometry: from intact oligomers to functional machineries. Current Opinion In Chemical Biology. 2004;8:519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Duijn E, Bakkes PJ, Heeren RMA, van den Heuvell RHH, van Heerikhuizen H, van der Vies SM, Heck AJR. Monitoring macromolecular complexes involved in the chaperonin-assisted protein folding cycle by mass spectrometry. Nature Methods. 2005;2:371–376. doi: 10.1038/nmeth753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poliakov A, Duijn E. v., Lander G, Fu C.-y., Johnson JE, Prevelige JPE, Heck AJR. Macromolecular mass spectrometry and electron microscopy as complementary tools for investigation of the heterogeneity of bacteriophage portal assemblies. Journal of Structural Biology. 2007;157:371. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olia AS, Al-Bassam J, Winn-Stapley DA, Joss L, Casjens SR, Cingolani G. Binding-induced stabilization and assembly of the phage P22 tail accessory factor gp4. J Mol Biol. 2006;363:558–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang F, Nau WM. A conformational flexibility scale for amino acids in peptides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:2269–72. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heck AJ, Van Den Heuvel RH. Investigation of intact protein complexes by mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2004;23:368–89. doi: 10.1002/mas.10081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isabel Catalina M, R. H. H. v. d. H. E. v. D. A. J. R. H. Decharging of Globular Proteins and Protein Complexes in Electrospray. Chemistry - A European Journal. 2005;11:960–968. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pringle SD, Giles K, Wildgoose JL, Williams JP, Slade SE, Thalassinos K, Bateman RH, Bowers MT, Scrivens JH. An investigation of the mobility separation of some peptide and protein ions using a new hybrid quadrupole/travelling wave IMS/oa-ToF instrument. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2007;261:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruotolo BT, Giles K, Campuzano I, Sandercock AM, Bateman RH, Robinson CV. Evidence for Macromolecular Protein Rings in the Absence of Bulk Water. Science. 2005;310:1658–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.1120177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lurz R, Orlova EV, Gunther D, Dube P, Droge A, Weise F, van Heel M, Tavares P. Structural organisation of the head-to-tail interface of a bacterial virus. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;310:1027–1037. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cingolani G, Moore SD, Prevelige PE, Johnson JE. Preliminary crystallographic analysis of the bacteriophage P22 portal protein. Journal of Structural Biology. 2002;139:46. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bazinet C, Villafane R, King J. Novel second-site suppression of a cold-sensitive defect in phage P22 procapsid assembly. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;216:701–716. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90393-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lorenzen K, Vannini A, Cramer P, Heck AJR. Structural biology of RNA polymerase III: mass spectrometry elucidates subcomplex architecture. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Olia AS, Bhardwaj A, Joss L, Casjens S, Cingolani G. Role of Gene 10 Protein in the Hierarchical Assembly of the Bacteriophage P22 Portal Vertex Structure. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8776–8784. doi: 10.1021/bi700186e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olia AS, Al-Bassam J, Winn-Stapley DA, Joss L, Casjens SR, Cingolani G. Binding-induced stabilization and assembly of the phage P22 tail accessory factor gp4. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006;363:558–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krutchinsky AN, Chernushevich IV, Spicer VL, Ens W, Standing KG. Collisional damping interface for an electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Journal Of The American Society For Mass Spectrometry. 1998;9:569–579. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tahallah N, Pinkse M, Maier CS, Heck AJR. The effect of the source pressure on the abundance of ions of noncovalent protein assemblies in an electrospray ionization orthogonal time-of-flight instrument. Rapid Communications In Mass Spectrometry. 2001;15:596–601. doi: 10.1002/rcm.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lorenzen K, Versluis C, van Duijn E, van den Heuvel RHH, Heck AJR. Optimizing macromolecular tandem mass spectrometry of large non covalent complexes using heavy collision gases. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. In Press, Accepted Manuscript. [Google Scholar]