Abstract

Childhood-onset mitochondrial encephalomyopathies are usually severe, relentlessly progressive conditions that have a fatal outcome. However, a puzzling infantile disorder, long known as ‘benign cytochrome c oxidase deficiency myopathy’ is an exception because it shows spontaneous recovery if infants survive the first months of life. Current investigations cannot distinguish those with a good prognosis from those with terminal disease, making it very difficult to decide when to continue intensive supportive care. Here we define the principal molecular basis of the disorder by identifying a maternally inherited, homoplasmic m.14674T>C mt-tRNAGlu mutation in 17 patients from 12 families. Our results provide functional evidence for the pathogenicity of the mutation and show that tissue-specific mechanisms downstream of tRNAGlu may explain the spontaneous recovery. This study provides the rationale for a simple genetic test to identify infants with mitochondrial myopathy and good prognosis.

Keywords: mitochondrial myopathy, reversible COX deficiency, homoplasmic tRNA mutation

Introduction

Mitochondrial diseases are a large and clinically heterogeneous group of disorders that result from deficiencies in cellular energy production and have an estimated birth incidence of 1 : 5000, making them among the most common inherited metabolic diseases (Schaefer et al., 2008). More than 200 mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) point mutations have been identified as primary causes of mitochondrial disease, predominantly in mitochondrial transfer RNA (mt-tRNA) genes (DiMauro and Hirano, 2005; Taylor and Turnbull, 2005; Pereira et al., 2009). In addition, mutations in nuclear genes may also affect single or multiple respiratory chain (RC) enzymes, causing diseases inherited as Mendelian traits (DiMauro and Hirano, 2005). Affected children often suffer from multisystem disorders and die in childhood. The underlying genetic defect in many patients remains unknown and there are no effective treatments (Shoubridge, 2001; Debray et al., 2007). However, a puzzling clinical syndrome, initially termed ‘benign infantile mitochondrial myopathy due to reversible cytochrome c oxidase (COX) deficiency’ stands out by showing complete (or almost complete) spontaneous recovery (DiMauro et al., 1981). Affected children uniformly present with severe muscle weakness and hypotonia in the first days or weeks of life and often require assisted ventilation. However, they improve spontaneously between 5 and 20 months of age and are usually normal by 2 or 3 years of age (DiMauro et al., 1981, 1983; Roodhooft et al., 1986; Zeviani et al., 1987; Nonaka et al., 1988; Tritschler et al., 1991; Salo et al., 1992; Wada et al., 1996). Although potentially benign, this myopathy is life-threatening in the first months of life and patients require vigorous life-sustaining measures. Muscle biopsies taken in the neonatal period are essentially identical to those of children with irreversible and fatal COX deficiency. There are numerous ragged-red fibres (RRF) indicative of mitochondrial accumulation and the histochemical reaction for COX activity is absent in virtually all fibres, although present in spindles and intramuscular blood vessels, emphasizing that skeletal muscle is the only affected tissue (Tritschler et al., 1991). However, biopsies taken at later times show no RRF and increasing numbers of COX-positive fibres, in parallel with the clinical and biochemical recovery (Salo et al., 1992; Wada et al., 1996).

Despite thorough investigations, until now no specific test was available to distinguish children with the reversible disease from those with the lethal COX-deficiency. It was speculated that the defect might involve a nuclear-encoded COX subunit that is not only tissue specific, but also developmentally regulated (Tritschler et al., 1991). Mutations of a foetal or neonatal muscle isoform would be overcome on expression of the mature isoform, as seen for example, in the rare congenital myasthenic Escobar syndrome (Hoffmann et al., 2006). However, sequencing of the genes encoding the obvious candidates, COXVIa and COXVIIa, did not reveal any mutations (Tritschler et al., 1991). Early differential diagnosis between fatal and benign mitochondrial myopathies is of critical importance for prognosis and management of these infants, because the benign form is initially life threatening but ultimately reversible. Here, we define a simple molecular test that will identify children with reversible COX deficiency. Supportive care should not be withdrawn from these children early in life.

Materials and methods

Patients

The study included 17 patients with the clinical phenotype of reversible COX deficiency (Table 1). All patients were white Caucasians, but from different ethnic groups (American, Swedish, German, Brazilian and Italian).

Table 1.

Summary of the clinical presentation of reversible COX deficiency in 17 patients

| Patient | Affected relatives | Onset | Clinical presentation |

Improved | Last control | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle | Ventilation | Tube feeding | Liver | ||||||

| P1/M | – | 36 h | + | + | + | – | 5–16 months | 33 months mild myopathy | DiMauro, 1983 |

| P2/M | – | 6 weeks | + | + | + | – | 6–15 months | 20 months mild myopathy | Zeviani, 1987 |

| P3/M | Sibling (P4) | 3 weeks | + | + | + | + | 5–20 months | 4 years healthy | Salo, 1992 |

| P4/F | Sibling (P3) | 12 weeks | + | – | + | – | From 6 months | 13 months mild myopathy | Salo, 1992 |

| P5/F | Sibling | 24 days | + | + | + | – | None | Died at 39 days | This article |

| P6/F | – | 4 weeks | + | + | + | – | 7–12 months | 7.5 years myopathy, epilepsy | This article |

| P7/M | a | 15 days | + | + | + | – | 5 months | 22 months stands with support | This article |

| P8/M | – | Birth | + | – | – | – | 4 months | 5 years normal | This article |

| P9/M | Maternal uncle (P10) | 1 month | + | – | + | + | 10–22 months | 22 years mild prox. myopathy | Houshmand, 1994 |

| P10/M | Maternal nephew (P9) | 1 month | + | + | + | – | 7–18 months | 7 years healthy | This article |

| P11/F | – | Birth | + | – | + | – | 9–36 months | 17 years mild myopathy | Houshmand, 1994 |

| P12/M | – | 2 months | + | – | + | – | 5–19 months | 7 years healthy | This article |

| P13/F | – | 1 month | + | – | + | – | 11–17 months | 11 years healthy | This article |

| P14/M | Sibling (P15), maternal sibs (P17, P16) | Birth | + | + | + | + | 6–30 months | 11 years mild myopathy | This article |

| P15/M | Sibling (P14), maternal sibs (P17, P16) | 2.5 months | + | + | + | – | 5–20 months | 9 years healthy | This article |

| P16/F | Sibling (P17), maternal nephews (P14,15) | 1 month | + | – | + | – | 6–24 months | 26 years healthy | This article |

| P17/M | Sibling (P16), maternal nephews (P14, 15) | 1 month | + | – | + | – | 5–18 months | 26 years healthy | This article |

a Mild motor developmental delay in the mother, disturbed weight gain and anaemia in one sibling.

Muscle histology and biochemistry

Muscle histology was performed by standard methods. Activities of RC complexes I–IV were determined in skeletal muscle and cultured cells (myoblasts and fibroblasts) as described (Fischer et al., 1986; Tulinius et al., 1991).

Molecular genetic studies

Sequencing of the mtDNA, Southern blot and long-range PCR for mtDNA rearrangements and real-time PCR for assessment of mtDNA copy numbers were carried out using standard methods.

Levels of m.14674T>C mutant mtDNA were assessed by last hot cycle PCR/RFLP. DNA samples were processed as described by Taylor et al. (2003) with the following modifications. PCR amplifications were performed using the forward mismatch primer L14651 (nt positions 14651–14673) 5′-AACAGAAACAAAGCATACACCAT-3′ (mismatch base shown in bold) and the M13-tagged reverse primer M13-H14810 (nt positions 14810–14791) 5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCGGAGGTCGATGAATGAGTGG-3′ with an annealing temperature of 60°C, generating a 182-bp fragment that encompasses the m.14674T>C mutation site. Equal amounts of (alpha-32P)-deoxycytidinetriphosphate-labelled PCR products were then digested with 10 U BccI (New England Biolabs, Hitchin, UK). Wild-type amplicons contain a single BccI recognition site and on digestion, two fragments of 108 and 74 bp are generated. In PCR products harbouring the m.14674T>C mutation, the mismatch primer creates an additional BccI site, producing three fragments of 108, 46 and 28 bp.

High-resolution northern blot analysis

Total RNA from skeletal muscle and from 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cultured primary fibroblasts, myoblast and differentiated myoblast (myotubes) lines was extracted using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. High-resolution northern blot analysis of total RNA (1 µg) was performed as previously described (Tuppen et al., 2008). The human mt-tRNALeu(UUR) probe was generated using the forward primer L3200 (positions 3200–3219) 5′-TATACCCACACCCACCCAAG-3′ and reverse primer H3353 (positions 3353–3334) 5′-GCGATTAGAATGGGTACAAT-3′. The human mt-tRNAGlu probe was generated using the forward primer L14635 (positions 14 810–14 791) 5′-TACTAAACCCACACTCAACAG-3′ and reverse primer H14810 (positions 14 810–14 791) 5′-GGAGGTCGATGAATGAGTGG-3′. The radioactive signal for the mt-tRNAGlu probe was normalized to that of the tRNALeu(UUR) probe for each sample.

Immunoblotting

Aliquots of 10–20 μg protein from skeletal muscle or cell homogenates were loaded on 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gels and tested with antibodies recognizing COXII, CI-20/NDUFB8, CII-70 kDa (Mitosciences, Eugene, Oregon, USA), COXI and Porin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA) according to the supplier's recommendations.

Cell culture experiments

Human primary fibroblasts and myoblasts were obtained from Patients 7 and 14. Control cells were requested from the Muscle Tissue Culture Collection (Friedrich-Baur Institute Munich). Muscle cells were grown in skeletal muscle growth medium (SGM; PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany), supplemented with 4 mM l-glutamine and 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS). Differentiation and fusion into multinucleated myotubes was induced at 70% confluence by replacing skeletal muscle growth medium with serum-reduced fusion medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 2% horse serum and 2 mM glutamine) for 6 days. All cells were analysed by in vivo 35S-metabolic labelling studies (Chomyn et al., 1996), high-resolution northern blot analysis (Tuppen et al., 2008) and immunoblotting as described.

In vivo labelling and analysis of mitochondrial protein synthesis

In vivo 35S-metabolic labelling studies were performed as described previously (Chomyn et al., 1996) with the following modifications. Cells, cultured to 60–70% confluency in T25 mm flasks, were pretreated with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma, Poole, UK) containing 10% (v/v) FBS, 50 μg/ml uridine and 50 μg/ml chloramphenicol for 15 h at 37°C/5% CO2. Cells were subsequently washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma, Poole, UK) and incubated for 15 min at 37°C/5% CO2 in methionine/cysteine and FBS-free DMEM, supplemented with 5% (v/v) dialysed FBS, 0.1 mg/ml anisomycin (Sigma, Poole, UK). Following addition of 200 mCi/ml 35S-methionine/cysteine (35S EasyTag EXPRESS; Perkin Elmer, Beaconsfield, UK), cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C/5% CO2, then washed with PBS and a cell pellet was prepared. Total protein yield was calculated by Bradford assay and equal quantities of total protein (50 μg) were pretreated with 1 U Benzonase Endonuclease (Merck & Co., Inc, New Jersey, USA) for 1 h. Pretreated samples were then separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS/PAGE). Radiolabelled proteins were visualized by PhosphorImager analysis (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK) and equal protein loading was confirmed by Coomassie blue staining.

Results

Clinical presentation

The disease affects skeletal muscle selectively and in a strictly age-specific manner, since all patients had profound hypotonia, respiratory and feeding difficulties in the first days or weeks of life, together with highly increased serum lactate. One patient died of pneumonia at 39 days as a consequence of the severe muscular hypotonia and respiratory insufficiency, but all others improved spontaneously between 4 and 20 months of age (Table 1). However, a mild residual myopathy frequently persisted later in life (Fig. 1). Some children showed mild, reversible involvement of other organs (liver, heart), but only during the most severe metabolic crises, when increased CK and low carnitine levels were also found occasionally (Table 2). Brain, peripheral nerves and cognitive development were unaffected in all patients in the initial phase of the disease, although Patient 6 developed neurological symptoms at a later stage. Family history suggested maternal inheritance in three families (Fig. 1) and siblings were affected in three families without parental consanguinity.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of three families suggested a maternal inheritance. RFLP analysis for m.14674T>C in the family of Patient 14 revealed that the mutation is homoplasmic in all maternal individuals and absent in the fathers. The two brothers, at ages 8 and 10 years, showed signs of a mild residual myopathy. P14 (III:1) has a myopathic face and both patients (III:1, III:2) show scapular winging.

Table 2.

Laboratory investigations and muscle biopsy findings of 17 patients with reversible COX deficiency

| Patient | Laboratory results |

Muscle histology |

EM | RC |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate | CK | Carn | RRF/COX– | Lipid | Glycogen | Other findings | COX | Other RC | ||

| P1 | ↑↑↑ | Norm | 1 month: +++ | + | – | Normal | 6% | Norm | ||

| 7 months: ++ | ++ | + | Few atrophic fibres | Giant mt, crista path | 50% | Norm | ||||

| 36 months: – | – | – | Fibrosis, atrophy | ↑ | Norm | |||||

| P2 | ↑↑↑ | ↑ 662 | ↓ | 2 months: +++ | + | – | Normal | n.d. | n.d. | |

| 4 months: +++ | + | + | Normal | 11% | Norm | |||||

| 11 month: – | – | – | Fibrosis, atrophy | 57% | Norm | |||||

| P3 | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑ 1402 | ↓↓ | 3 months: +++ | + | + | Necrotic/split fibres | Giant mt, crista path | 25% | Norm |

| 16 months: – | – | – | Normal | n.d. | n.d. | |||||

| P4 | ↑↑↑ | ↑ 798 | ↓ | 3 months: +++ | + | + | Necrotic/split fibres | 25% | Norm | |

| 13 months: + | – | – | Mild myopathy | n.d. | n.d. | |||||

| P5 | ↑↑↑ | n.d. | 1 month: +++ | + | – | Normal | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| P6 | ↑↑↑ | 119 | ↓ | 1 month: ++ | + | – | Vacuolar myopathy | 29% | Norm | |

| P7 | ↑↑↑ | Mild↑ | 3 months: +++ | + | + | Normal | 29% | Norm | ||

| 13 months: normal | – | – | Normal | 121% | Norm | |||||

| P8 | ↑↑↑ | n.d. | 5 months: +++ | + | – | Normal | 52% | Norm | ||

| P9 | ↑↑↑ | ↑ | 2 months: +++ | + | – | Abnormal mt | ↓↓↓ | CI ↓↓↓ | ||

| 5 years 4 months: + | – | – | Mild myopathy | Norm | CI ↓ | |||||

| 14 years 5 months: + | – | – | Necrotic/mild myopathy | ↓ | CI ↓ | |||||

| P10 | ↑↑↑ | Norm | 1 month: +++ | – | – | Normal | ↓↓↓ | CI ↓↓↓ | ||

| P11 | ↑↑↑ | ↑ | 1 month: +++ | + | – | Abnormal mt | ↓↓↓ | CI ↓↓↓ | ||

| 8 years 9 months: + | – | – | Mild myopathy | Norm | Norm | |||||

| P12 | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↓ | 3 months: +++ | – | – | Normal | ↓↓↓ | CI ↓↓ | |

| P13 | ↑↑↑ | ↑ | 1 month: +++ | – | – | Normal | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| P14 | ↑↑↑ | Norm | ↓ | 1 month: +++ | + | + | Abnormal mt | Giant mt, crista path | 5% | CI 25% |

| 10 years: + | – | – | Normal | 110% | Norm | |||||

| P15 | ↑↑↑ | Norm | 1 month: +++ | + | + | Abnormal mt | Giant mt, crista path | 3% | CI 15% | |

| P16 | ↑↑↑ | Norm | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| P17 | ↑↑↑ | Norm | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

+++ = severe (>25%); ++ = moderate (5%–25%); += mild (<5%); ↑↑↑ = severely increased; ↑↑ = moderately increased; ↑ = mildly increased; CI = complex I; mt = mitochondria; n.d = no data.

Muscle histology and biochemistry

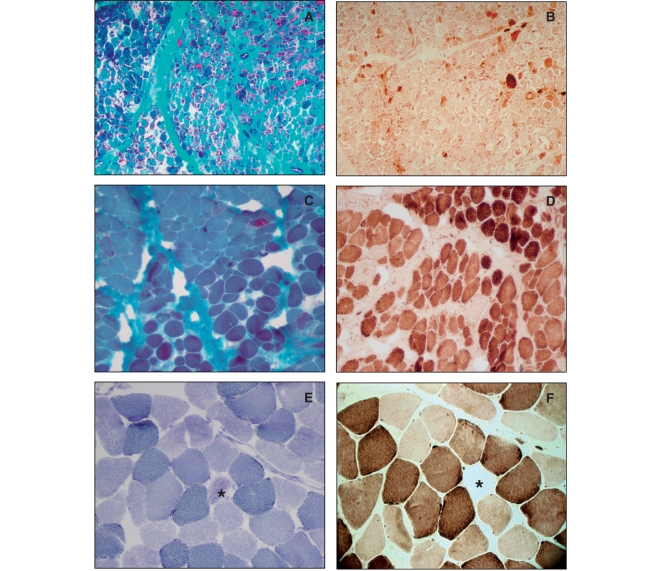

The first muscle biopsy was performed in all children in the acute phase of the disease (1–5 months of age). In seven patients, follow-up biopsies were also obtained (Table 2). In summary, early biopsies confirmed severe mitochondrial myopathy with RRF and even more numerous COX-negative fibres and ultrastructurally abnormal mitochondria in all patients. These changes significantly improved, but usually did not completely disappear on later biopsies (Fig. 2). On routine morphology, many muscle fibres appeared normal but vacuolar changes and mild structural abnormalities with lipid and/or glycogen accumulation were detected in most cases. Electron microscopy was performed in four patients and showed giant mitochondria with very characteristic multilamellar paracrystalline inclusions.

Figure 2.

Histochemical staining of the muscle biopsy from Patient 7 at 3 months of age (A and B) and 9 years (C and D) and of the muscle from his asymptomatic mother (E and F). The early biopsy confirmed severe mitochondrial myopathy with RRF (A) and even more COX-negative fibres (B). These changes significantly improved but did not completely disappear at 9 years of age (C and D). The muscle biopsy from the mother revealed a few COX-negative (F), SDH hyper-reactive (E) fibres (stars). A, C: Gomori trichrome; B, D, F: COX; E: SDH stain. Magnification: A, B 100×, C, D, E, F 200×.

Biochemical analysis of RC enzymes in muscle revealed combined RC deficiencies, most severely affecting COX in early biopsies (Table 2). This was accompanied by a defect of complex I and, less commonly, of other complexes containing mtDNA-encoded subunits. In the recovery phase, all RC activities returned to normal or supernormal levels, indicating the involvement of compensatory mechanisms.

Molecular genetic analysis

Molecular genetic analysis revealed no mtDNA deletions and normal mtDNA copy number in muscle from all patients tested and there were no significant differences between follow-up biopsies. Sequencing of the entire mitochondrial genome revealed several nucleotide variations from the revised Cambridge reference sequence, represented on publicly available databases (http://www.mitomap.org/; http://www.genpat.uu.se/mtDB/). A single homoplasmic variant, m.14674T>C (Fig. 4A), was detected in all 17 patients and in all maternal family members (Fig. 1). The mutation analysis in the relatives of the probands was performed in DNA extracted from blood leukocytes. This mutation affects a poorly conserved nucleotide, but we could not detect it in 200 German control individuals. It is reported in 3 out of 2704 samples in both the mtDB and the MITOMAP databases as a neutral polymorphism labelled haplogroup M27b, although retrospective analysis of the subjects listed in MITOMAP revealed that these individuals did in fact present with a clinical phenotype similar to that reported here (Patients 9 and 11 in this study) (Houshmand et al., 1994). The patients belong to different major mtDNA haplogroups (H, U, V).

Figure 4.

(A) Schematic representation of m.14674T>C in mt-tRNAGlu, F: forward sequence, R: reverse sequence. (B) 35S methionine pulse-labelling in myoblasts of Patients 7 and 14 revealed normal mitochondrial translation.

High-resolution northern blot analysis

Northern blotting of skeletal muscle of Patients 7, 11 and 14 and primary cell cultures of Patients 7 and 14 indicated that the steady-state level of mt-tRNAGlu was significantly decreased compared to controls (Fig. 3A). The decrease was most severe (16–30% of age-matched controls) in skeletal muscle taken at 1–3 months of age. The steady-state level of the mt-tRNAGlu in the second muscle biopsy after recovery and also in clinically healthy mothers of Patients 7 and 11 was less severely decreased (30–60%) and similar to that detected in myoblasts.

Figure 3.

(A) Northern blot for mt-tRNAGlu showed severely decreased steady-state levels in skeletal muscle of Patient 11 at 1 month of age and slightly higher, but still significantly decreased levels, after clinical recovery at 9 years of age, as well as in muscle biopsies of her asymptomatic mother (M). Data from skeletal muscle are not shown for Patients 7 and 14. Myoblasts of Patient 14 showed steady-state levels similar to late biopsies and to biopsies of a healthy mother. Patient mt-tRNAGlu steady-state levels normalized to mt-tRNALeu(UUR) levels are expressed relative to normalized control levels. (B) Immunoblotting showed decreased levels of the mitochondrial COXI, COXII and complex I (NDUFB8) subunits in the biopsy of Patient 11 at 1 month of age, which returned to normal at 9 years of age, and was also normal in her asymptomatic mother. The same subunits were slightly increased in myoblasts of Patient 14.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies against mitochondrial-encoded COX and complex I subunits showed markedly decreased levels in early biopsies, when the children showed severe symptoms, but were normal in biopsies after recovery and in healthy mothers (Fig. 3B).

In vivo labelling and analysis of mitochondrial protein synthesis

Pulse labelling experiments with 35S methionine in myoblasts of Patients 14 and 7 showed normal intensity for most mitochondrial proteins (Fig. 4B). Immunoblotting with antibodies against mitochondrial proteins confirmed the normal (or increased) levels of COX and complex I subunits in the patient's cells (Fig. 3B). Further evidence for the rescue in vitro is provided by the normal RC activities on direct enzyme measurement. These findings were unexpected because the steady-state level of mt-tRNAGlu was still low (50% of controls).

Discussion

The homoplasmic m.14674T>C mutation was detected in 17 affected individuals from 12 independent families of different ethnic origins. The different mtDNA haplogroup backgrounds indicate that the same mt-tRNAGlu mutation has arisen independently, on multiple occasions, causing the same disease. Seven out of 22 maternal family members from three families (Fig. 1) developed severe, mostly isolated muscle hypotonia and weakness requiring intensive care, but most homoplasmic carriers never experienced muscle weakness. The penetrance of the disease is variable, as seen in other mtDNA mutations, but the strong association with the phenotype and the reduced levels of mt-tRNAGlu transcript observed in the biopsies are highly suggestive of a pathogenic link.

This is also the case for other homoplasmic mtDNA mutations, as in Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) (Yu-Wai-Man et al., 2009). In LHON, the variable penetrance was attributed to the modifying role of nuclear factors, to mtDNA background, and to environmental influences (Yu-Wai-Man et al., 2009). Similar mechanisms are likely to underlie the manifestation of reversible COX deficiency myopathy. To identify other potential modifiers, a better understanding of the disease pathogenesis is required, although we were not able to define any epistatic, epigenetic or environmental modifying factors in the 17 cases studied here.

What is the pathological mechanism of the disease?

To date, six pathogenic mutations have been described in mt-tRNAGlu (http://www.mitomap.org/), all of which tend to reach either a very high level of heteroplasmy or homoplasmy in the skeletal muscle of affected individuals. Although the clinical phenotype is variable, there is constant and predominant involvement of skeletal muscle. However, none of these patients had a truly reversible phenotype, implying that reversible COX deficiency myopathy is not a generic consequence of mutations in mt-tRNAGlu, but specifically of m.14674T>C.

This mutation affects the discriminator base of mt-tRNAGlu. This is the last base at the 3′-end of the molecule, where the amino acid is attached to the molecule via the terminal CCA. No pathogenic mutation has previously been described in this crucial position in any of the other 21 mitochondrial transfer RNAs.

The m.14674T>C mutation in mt-tRNAGlu is thought to impair mitochondrial translation, as reflected by the RRF/COX-negative fibres and the multiple RC defects in skeletal muscle. The predominant involvement of the mitochondrial COX subunits (Tritschler et al., 1991) may be explained by their high glutamic acid content or by the locations of the glutamic acid residues. The expression of stable mt-tRNAs relies on a number of post-transcriptional modification steps including: (i) 5′ and 3′ processing from the large polycistronic transcript by mitochondrial RNaseP (and presumably by tRNase Z); (ii) addition of the CCA trinucleotide to the 3′-end of the mt-tRNA transcript by [CCA] nucleotidyltransferase; base modification by a variety of mt-tRNA modifying enzymes; and (iii) aminoacylation of mt-tRNA by the cognate aminoacyl mt-tRNA synthetase (Levinger et al., 2004). It had been shown that mutations in the proximity of a discriminator base affect RNA processing (Levinger et al., 2004), but we are not aware of any functional data on mutations affecting the discriminator base itself, and northern blot analysis gave no indication of unprocessed intermediates in our patients’ samples. As a consequence of the mutation, the steady-state level of mt-tRNAGlu was decreased in skeletal muscle from three patients (Fig. 3A). Counter intuitively, the steady-state level of mt-tRNAGlu showed only a slight increase in the follow-up muscle biopsy, when the children were almost asymptomatic, and remained low (30–60%) in cells from patients and in muscle from clinically healthy mothers. The slight recovery of the steady-state level of mt-tRNAGlu in the face of dramatic clinical improvement indicates that either this mild increase of mt-tRNAGlu steady-state level is sufficient to regain normal mitochondrial translation, or that other mechanisms downstream of mt-tRNAGlu explain the clinical and biochemical improvement in vivo. Concerning the apparent surplus of mt-tRNA, it is interesting to note that normal levels of mitochondrial translation can be maintained by surprisingly low steady-state levels (∼10%) of the homoplasmic mt-tRNAVal, m.1624C>T at least in cultured myoblasts, fibroblasts and transmitochondrial cybrids (Rorbach et al., 2008).

In vitro pulse-labelling experiments in two patients (7 and 14) showed normal mitochondrial translation in myoblasts compared to normal controls (Fig. 4B). This result was bolstered by immunoblotting that showed normal or even hyperintense bands for mtDNA-encoded proteins (Fig. 3B) and by the normal RC enzyme activities. Experiments on cybrid cells would not have been informative, since cells homoplasmic for the mt-tRNA mutation do not display a clear biochemical defect. It is worth noting again that the same cells showed 40–50% decreased mt-tRNAGlu steady-state levels.

Why do symptoms start in early neonatal life and what is the mechanism of the spontaneous recovery?

Although our data provide strong evidence for a pathogenic role of m.14674T>C, they do not explain why all patients develop severe isolated myopathy in the neonatal period and, most importantly, what triggers the timed spontaneous recovery. We suggest that tissue-specific, developmentally timed processes play a role both in the age-dependent expression and in the reversibility. One hypothesis is that an increase in mtDNA copy number and the consequent increase in the number of tRNAGlu molecules would compensate for the defect and may overcome the functional consequences of the homoplasmic tRNA mutation in skeletal muscle. Morten et al. (2007) showed that the mtDNA content of liver increases rapidly over the perinatal period up to 1 year of age. In muscle, a similar progressive increase in mtDNA copy number, RC activity, and muscle power was also detected. Comparative studies of muscle mtDNA from 54 patients showed that patients 7–12 months of age had slightly higher mtDNA copy number than patients <6 months of age (Macmillan et al., 1996), but the increase was not statistically significant. Another study on 300 muscle DNA samples showed that mtDNA content in muscle increases steadily from birth to about 5 years of age (Bai et al., 2004). We measured mtDNA copy numbers in muscle DNA extracted from consecutive biopsies but did not get any significant changes compared to normal controls, indicating that the recovery in benign COX deficiency cannot be explained by a change in mtDNA copy number.

Another explanation would relate the recovery to the modifying effects of muscle-specific genes that are developmentally regulated and display isoform switching. Many of these genes encode contractile proteins or enzymes involved in energy metabolism. It was shown that the nuclear-encoded COXVIa and COXVIIa subunits also undergo complex changes during development (Tritschler et al., 1991) and switch from foetal or ubiquitous isoforms to the corresponding muscle isoforms as development progresses. However, the exact timing of such changes needs to be further evaluated. These data may also support a developmental switch in the control strength of mitochondrial transfer RNAs and, in particular, mt-tRNAGlu in mitochondrial translation, suggesting that 16–30% steady-state levels of mt-tRNAGlu may have a profound effect on translation in muscle of neonates but may become less critical at later stages of development.

In summary, we provide evidence that reversible COX deficiency myopathy is caused by a homoplasmic mt-tRNAGlu mutation m.14674T>C. This is critically important because severe mitochondrial myopathy in early life is usually irreversible, prompting clinicians and parents to face end-of-life decisions for a young child. We suggest that floppy infants with suspected mitochondrial myopathy should be screened for this mutation. This simple genetic test is of critical importance for prognosis and management of these infants because the benign form is initially life threatening but ultimately reversible.

Funding

Part of this work was supported by Swedish research grant number 7122 (to M.T.); Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft HO 2505/2-1 and the Academy of Medical Sciences (to R.H.); RVI/NGH and Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Charity (RES0211/7262) (to R.H. and J.P.K.); Wellcome Trust (074454/Z/04/Z) and the BBSRC (BB/F011520/1) (to R.W.T., Z.M.A.C.-L. and R.N.L.). PFC is a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow in Clinical Science, who also receives funding from the United Mitochondrial Diseases Foundation, the Medical Research Council (UK), the UK Parkinson's Disease Society, and the UK NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ageing and Age-related disease award to the Newcastle upon Tyne Foundation Hospitals NHS Trust. The Muscle Tissue Culture Collection is part of the German network on muscular dystrophies (MD-NET, service structure S1, 01GM0601) funded by the German ministry of education and research (BMBF, Bonn, Germany). The Muscle Tissue Culture Collection is a partner of EuroBioBank (www.eurobiobank.org) and TREAT-NMD (EC, 6th FP, proposal # 036825). Researchers at Columbia University Medical Center were supported by NIH grant HD32062 and by the Marriott Mitochondrial Disorders Clinical Research Fund (MMDCRF).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Inger Nennesmo MD, PhD for sharing morphologic findings in one of the patients. The family members gave consent to the publication of their photographs.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- COX

cytochrome c oxidase

- LHON

Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy

- mt-tRNA

mitochondrial transfer RNA

- RC

respiratory chain

- RRF

ragged-red fibres

References

- Bai RK, Perng CL, Hsu CH, Wong LJ. Quantitative PCR analysis of mitochondrial DNA content in patients with mitochondrial disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1011:304–309. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-41088-2_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomyn A. In vivo labeling and analysis of human mitochondrial translation product. Methods Enzymol. 1996;264:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)64020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debray FG, Lambert M, Chevalier I, Robitaille Y, Decarie JC, Shoubridge EA, et al. Long-term outcome and clinical spectrum of 73 pediatric patients with mitochondrial diseases. Pediatrics. 2007;119:722–733. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMauro S, Nicholson JF, Hays AP, Eastwood AB, Koenigsberger R, DeVivo DC. Benign infantile mitochondrial myopathy due to reversible cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1981;106:205–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMauro S, Nicholson JF, Hays AP, Eastwood AB, Papadimitriou A, Koenigsberger R, et al. Benign infantile mitochondrial myopathy due to reversible cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Ann Neurol. 1983;14:226–234. doi: 10.1002/ana.410140209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMauro S, Hirano M. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies: an update. Neuromusc Disord. 2005;15:276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JC, Ruitenbeek W, Gabreels FJ, Janssen AJ, Renier WO, Sengers RC, et al. A mitochondrial encephalomyopathy: the first case with an established defect at the level of coenzyme Q. Eur J Pediatr. 1986;144:441–444. doi: 10.1007/BF00441735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houshmand M, Larsson NG, Holme E, Oldfors A, Tulinius MH, Andersen O. Automatic sequencing of mitochondrial tRNA genes in patients with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1226:49–55. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann K, Muller JS, Stricker S, Megarbane A, Rajab A, Lindner TH, et al. Escobar syndrome is a prenatal myasthenia caused by disruption of the acetylcholine receptor fetal gamma subunit. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:303–312. doi: 10.1086/506257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinger L, Oestreich I, Florentz C, Mörl M. A pathogenesis-associated mutation in human mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) leads to reduced 3'-end processing and CCA addition. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morten KJ, Ashley N, Wijburg F, Hadzic N, Parr J, Jayawant S, et al. Liver mtDNA content increases during development: a comparison of methods and the importance of age- and tissue-specific controls for the diagnosis of mtDNA depletion. Mitochondrion. 2007;7:386–395. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan CJ, Shoubridge EA. Mitochondrial DNA depletion: prevalence in a pediatric population referred for neurologic evaluation. Pediatr Neurol. 1996;14:203–210. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka I, Koga Y, Shikura K, Kobayashi M, Sugiyama N, Okino E, et al. Muscle pathology in cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Acta Neuropathol. 1988;77:152–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00687425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira L, Freitas F, Fernandes V, Pereira JB, Costa MD, Costa S, et al. The diversity present in 5140 human mitochondrial genomes. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:628–640. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodhooft AM, Van Acker KJ, Martin JJ, Ceuterick C, Scholte HR, Luyt-Houwen IE. Benign mitochondrial myopathy with deficiency of NADH-CoQ reductase and cytochrome c oxidase. Neuropediatrics. 1986;17:221–226. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1052534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorbach J, Yusoff AA, Tuppen H, Abg-Kamaludin DP, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM, Taylor RW, et al. Overexpression of human mitochondrial valyl tRNA synthase can partially restore levels of cognate mt-tRNAVal carrying the pathogenic C25U mutation. Nucleic Acid Res. 2008;36:3065–3074. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo MK, Rapola J, Somer H, Pihko H, Koivikko M, Tritschler HJ, et al. Reversible mitochondrial myopathy with cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:1033–1035. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.8.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer AM, McFarland R, Blakely EL, He L, Whittaker RG, Taylor RW, et al. Prevalence of mitochondrial DNA disease in adults. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:35–39. doi: 10.1002/ana.21217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoubridge EA. Cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Am J Med Genet. 2001;106:46–52. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RW, Giordano C, Davidson MM, d'Amati G, Bain H, Hayes CM, et al. A homoplasmic mitochondrial transfer ribonucleic acid mutation as a cause of maternally inherited hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1786–1796. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human disease. Nature Rev Genet. 2005;6:389–402. doi: 10.1038/nrg1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritschler HJ, Bonilla E, Lombes A, Andreetta F, Servidei S, Schneyder B, et al. Differential diagnosis of fatal and benign cytochrome c oxidase-deficient myopathies of infancy: an immunohistochemical approach. Neurology. 1991;41:300–305. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.2_part_1.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulinius MH, Holme E, Kristiansson B, Larsson NG, Oldfors A. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies in children. I. Biochemical and morphologic investigations. J Pediatr. 1991;119:242–250. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuppen HA, Fattori F, Carrozzo R, Zeviani M, DiMauro S, Seneca S, et al. Further pitfalls in the diagnosis of mtDNA mutations: homoplasmic mt-tRNA mutations. J Med Genet. 2008;45:55–61. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.051185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Woo M, Nishio H, Nagaki S, Yanagawa H, Imamura A, et al. Vascular involvement in benign infantile mitochondrial myopathy caused by reversible cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Brain Dev. 1996;18:263–268. doi: 10.1016/0387-7604(96)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu-Wai-Man P, Griffiths PG, Hudson G, Chinnery PF. Inherited mitochondrial optic neuropathies. J Med Genet. 2009;46:145–158. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.054270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeviani M, Peterson P, Servidei S, Bonilla E, DiMauro S. Benign reversible muscle cytochrome c oxidase deficiency: a second case. Neurology. 1987;37:64–67. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]