Abstract

Objective To evaluate the association between migraine and cardiovascular disease, including stroke, myocardial infarction, and death due to cardiovascular disease.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources Electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library) and reference lists of included studies and reviews published until January 2009.

Selection criteria Case-control and cohort studies investigating the association between any migraine or specific migraine subtypes and cardiovascular disease.

Review methods Two investigators independently assessed eligibility of identified studies in a two step approach. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Studies were grouped according to a priori categories on migraine and cardiovascular disease.

Data extraction Two investigators extracted data. Pooled relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

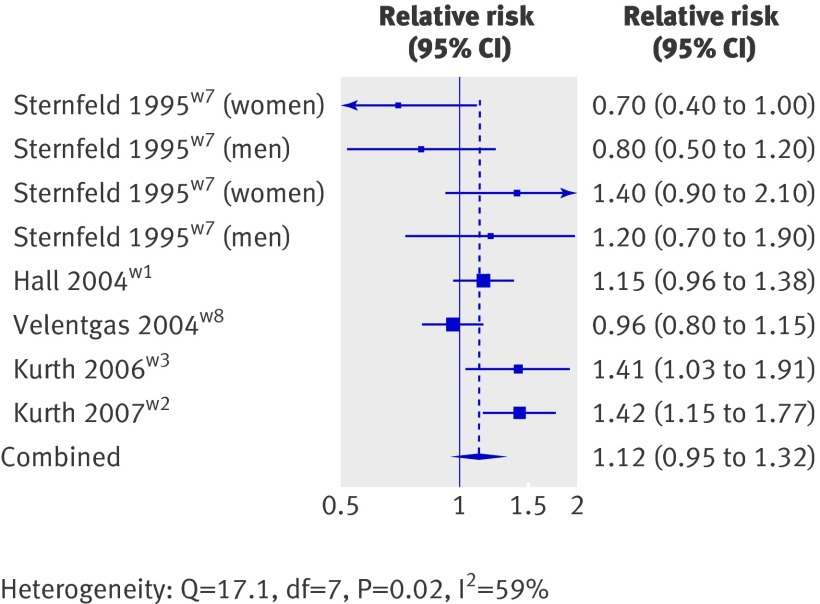

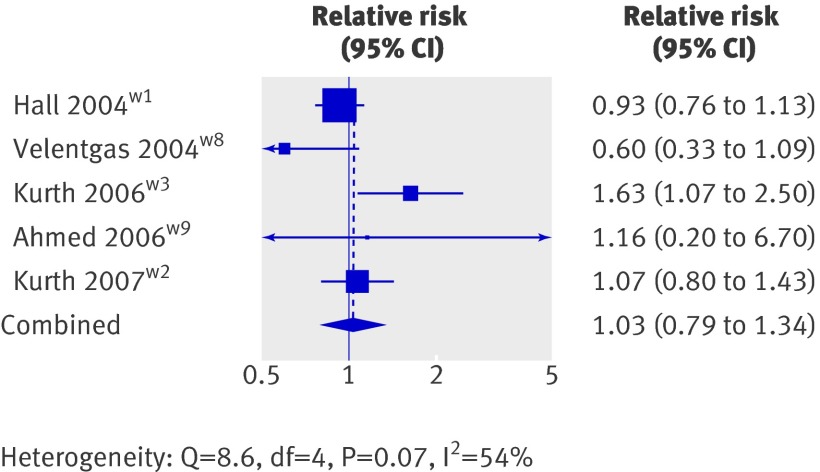

Results Studies were heterogeneous for participant characteristics and definition of cardiovascular disease. Nine studies investigated the association between any migraine and ischaemic stroke (pooled relative risk 1.73, 95% confidence interval 1.31 to 2.29). Additional analyses indicated a significantly higher risk among people who had migraine with aura (2.16, 1.53 to 3.03) compared with people who had migraine without aura (1.23, 0.90 to 1.69; meta-regression for aura status P=0.02). Furthermore, results suggested a greater risk among women (2.08, 1.13 to 3.84) compared with men (1.37, 0.89 to 2.11). Age less than 45 years, smoking, and oral contraceptive use further increased the risk. Eight studies investigated the association between migraine and myocardial infarction (1.12, 0.95 to 1.32) and five between migraine and death due to cardiovascular disease (1.03, 0.79 to 1.34). Only one study investigated the association between women who had migraine with aura and myocardial infarction and death due to cardiovascular disease, showing a twofold increased risk.

Conclusion Migraine is associated with a twofold increased risk of ischaemic stroke, which is only apparent among people who have migraine with aura. Our results also suggest a higher risk among women and risk was further magnified for people with migraine who were aged less than 45, smokers, and women who used oral contraceptives. We did not find an overall association between any migraine and myocardial infarction or death due to cardiovascular disease. Too few studies are available to reliably evaluate the impact of modifying factors, such as migraine aura, on these associations.

Introduction

Migraine is a common, chronic disorder with episodic attacks.1 It affects 10-20% of the population during the most productive periods of their working lives; women are affected up to four times more often than men.2 Clinically, migraine is characterised by recurrent attacks of headache and various combinations of symptoms related to the gastrointestinal and autonomic nervous system.3 Up to one third of patients with migraine experience an aura before or during the migraine headache characterised by neurological symptoms most often involving the visual field.

Migraine physiology is incompletely understood. The condition is viewed as an inherited disorder of the brain, but vascular mechanisms are clearly implicated. For example, endothelial dysfunction and hypercoagulability4 as well as a pathological vascular reactivity5 are among the important findings in patients with migraine. In addition, several population based and clinic based studies have established a link between migraine and ischaemic stroke. This evidence was summarised in a meta-analysis of data published until 2004,6 which found a significant association between migraine both with and without aura and ischaemic stroke. Subsequently, three large cohort studies,w1-w3 two case-control studies,w4 w5 and one cross sectional studyw6 were published on the association between migraine and ischaemic stroke, increasing the available sample from just over 7800 to more than 210 000. Results of these new studies suggest that the association between migraine and ischaemic stroke is limited to those who have migraine with aura. In addition, increasing evidence suggests that migraine is also associated with other ischaemic vascular events, including myocardial infarction or death due to cardiovascular disease.w1-w3 w7-w9 Because of the high prevalence of both migraine and cardiovascular disease as well as the consequences of cardiovascular disease on morbidity and mortality in the general population, a potential association would have a substantial impact on public health.

We assessed the current evidence on the association between migraine and cardiovascular disease, including stroke subtypes, myocardial infarction, angina, and death due to cardiovascular disease by systematically reviewing the literature and carrying out a meta-analysis. We also investigated potential modifying factors of the association between migraine and cardiovascular disease, including migraine aura, sex, age, smoking, and use of oral contraceptives.

Methods

We followed the guidelines for the design, performance, and reporting for meta-analyses of observational studies published by the MOOSE group.7

Two investigators (MS, PMR) independently searched Medline (from inception to January 2009), Embase (from inception to January 2009), and the Cochrane Library (issue 1, 2009) using the terms “headache” or “migraine” or “migraine disorders” in combination with “cardiovascular diseases” or “stroke” or “myocardial infarction” or “coronary revascularization” or “angina pectoris” or “mortality”. We combined the search terms with the “explode” feature where applicable and applied no language restrictions. In addition, we manually searched the reference lists of all primary articles and review articles.

A priori we defined strict criteria for inclusion of studies. We chose this approach over a weighting approach to reduce heterogeneity and to reflect more accurately the medical reality seen in clinical practice. Criteria were, firstly, that the studies must have a case-control or cohort design (we also considered cross sectional studies that restricted the analyses of the association between migraine and cardiovascular disease to events occurring after the onset of migraine); secondly, that the authors must investigate migraine or “probable migraine”; thirdly, that the authors must clearly define the criteria for the cardiovascular events; fourthly, that the authors must use a multivariable model or matching procedure that controls for potential confounding (if results from more than one multivariable model were presented, we used the data from the model with the maximum control of covariates); fifthly, that the authors must provide information on relative risk estimates—that is, odds ratios or hazard ratios, with 95% confidence intervals; and, finally, if multiple studies were published from the same study population we only included data from the report with the longest follow-up, or if similar with the larger number of participants, if all studies had a cohort design, or we included data from the cohort study instead of the case-control study, if different designs were used, and we included subgroup analyses of competing studies if these data were only provided in one of the studies.

We used two step selection processes to identify eligible studies. In the first step two investigators (MS, TK) screened the title and abstracts and by consensus identified all studies that did not meet any of the prespecified criteria. We excluded these studies. In the second step, the same investigators evaluated the full text versions of the remaining studies. Studies were excluded if they did not meet all criteria.

Data extraction

Two investigators (MS, PMR) independently extracted data and entered them in a customised database. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The extracted data included authors and title of study, year of publication, study design, study size, age range and sex of the participants, smoking status, use of oral contraceptives, migraine status (any migraine, migraine with aura, migraine without aura), investigated outcome (for example, total stroke, ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction, angina), and relative risks with 95% confidence intervals for each of the associations investigated. All data were extracted from the published studies and we did not contact the authors for further information.

Statistical analysis

For our analyses we grouped the studies according to the number available. We used the outcome categories as presented in the original articles (box). For the category of any migraine and ischaemic stroke, we included only studies that looked at any migraine (we did not pool results from migraine with and without aura) and that used strict criteria for ischaemic stroke (studies showing only combined results for ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attacks were excluded). We included studies irrespective of sex and age distribution. In addition to the overall analysis, we carried out stratified analyses according to study type (case-control v cohort), sex, age (<45 years v ≥45 years), use of oral contraceptives (current v none), and smoking status (current v not current). For the category of migraine with aura and ischaemic stroke we also looked at the subgroups of smokers, women currently using oral contraceptives, and women currently using oral contraceptives and smoking. For the analyses including any migraine and either myocardial infarction, angina, or death due to cardiovascular disease we looked at results for overall migraine among all studies as well as analyses stratified by sex, and results for migraine with and without aura separately.

Categories of studies included in systematic review and meta-analysis

Any migraine and ischaemic stroke

Migraine with aura and ischaemic stroke

Migraine without aura and ischaemic stroke

Any migraine and transient ischaemic attack

Any migraine and haemorrhagic stroke

Any migraine and any stroke

Any migraine and myocardial infarction

Any migraine and angina

Any migraine and death due to cardiovascular disease

We made the assumption that the odds ratios from case-control studies approximate the hazard ratios from cohort studies. To obtain pooled relative risk estimates we weighted the log of the odds ratios or hazard ratios by the inverse of their variance. We ran random effects models, which include assumptions on potential variability across studies. We used the DerSimonian and Laird Q test for heterogeneity. Since this test statistic has low power with studies of small sample size and excessive power if there are many studies (especially if they are large), we also calculated the I2 statistic for each analysis.8 This statistic describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance (25% low heterogeneity, 50% medium, 75% high). We used Galbraith plots9 to visually examine the impact of individual studies on the overall homogeneity test statistic, and we used meta-regression to evaluate the amount of heterogeneity of study type, sex, and migraine aura status on some of the cardiovascular events. We evaluated potential publication bias by visually examining for possible skewness in funnel plots10 and statistically with the methods described by Begg and Mazumdar10 and Egger.11 Egger’s method uses a weighted regression approach to investigate the association between outcome effects (log odds ratio or log hazard ratio) and its standard error in each study. Analyses were carried out with Stata 8.2.

Results

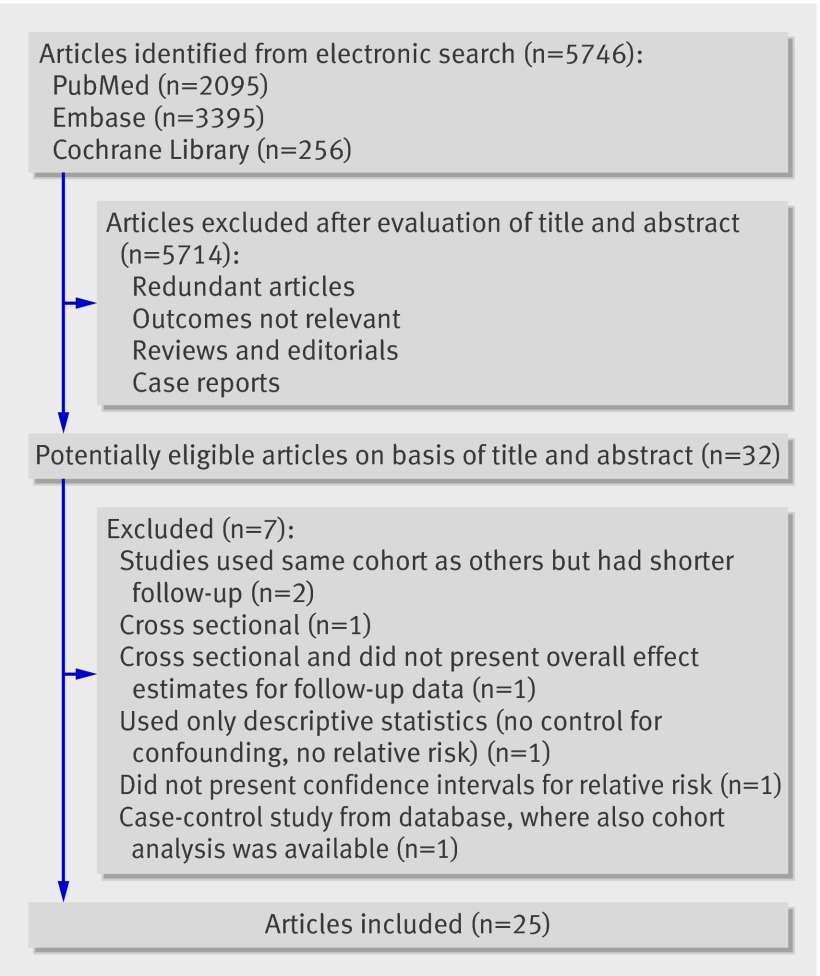

Figure 1 summarises the selection of studies. Of 5746 potentially eligible articles identified through the electronic search, 5714 were excluded after an evaluation of the title and abstract. A further seven were excluded: two used the same cohorts as other studies but had shorter follow-up,12 13 one did not present confidence intervals for the relative risks,14 one was cross sectional and did not present overall estimates for the follow-up data,15 one was cross sectional and the temporal association between migraine and cardiovascular events was not clear,16 one used only descriptive statistics,17 and one was a case-control study from a database that also contained a cohort analysis.18 Overall, 25 studies were suitable for inclusion in the analysis (table 1).

Fig 1 Process of study selection

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study design, reference (country) | Study size | Population (age at study entry) | Migraine type | Cardiovascular disease events investigated | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-control: | |||||

| Collaborative Group 1975 (USA)w10 | 430 cases, 429 hospital controls or 451 neighbour controls | Women (15-44) | Any | Ischaemic stroke+transient ischaemic attack, haemorrhagic stroke | Only stratified analysis according to oral contraceptive use |

| Henrich 1989 (USA)w16 | 89 cases, 178 controls | Both sexes (15-65) | Any, migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke | |

| Marini 1993 (Italy)w20 | 308 cases, 616 controls | Both sexes (15-44) | Migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke+transient ischaemic attack | |

| Tzourio 1993 (France)w24 | 212 cases, 212 controls | Both sexes, women, men (18-80) | Any, migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke | |

| Tzourio 1995 (France)w25 | 72 cases, 173 controls | Women (18-44) | Any, migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke | |

| Carolei 1996 (Italy)w12 | 308 cases, 591 controls | Both sexes, women, men (15-44) | Any, migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, ischaemic stroke+transient ischaemic attack | |

| Haapaniemi 1997 (Finland)w15 | 506 cases, 345 controls | Women, men (16-60) | Any | Ischaemic stroke | |

| Schwartz 1998 (USA)w23 | 373 cases, 1191 controls | Women (18-44) | Any | Ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke | |

| Chang 1999 (Europe)w13 | 291 cases, 736 controls | Women (20-44) | Any, migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, total stroke | |

| Donaghy 2002 (Europe)w14 | 86 cases, 214 controls | Women (20-44) | Migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke | Subcohort from Chang 1999w13; with focus on interaction of frequency and recency of association between migraine and ischaemic stroke |

| Schwaag 2003 (Germany)w22 | 160 cases, 160 controls | Both sexes (<46) | Any | Ischaemic stroke+transient ischaemic attack | |

| MacClellan 2007 (USA)w4 | 386 cases, 614 controls | Women (15-49) | Migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke | “Probable migraine” investigated |

| Pezzini 2007 (Italy)w5 | 333 cases, 187 controls | Both sexes (<45) | Migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke | Only stratified analysis according to cervical artery dissection |

| Cohort: | |||||

| Sternfeld 1995 (USA)w7 | 79 588 participants | Women, men (any) | Any | Myocardial infarction | Two cohorts distinguished because ascertainment of migraine changed during study period |

| Hall 2004 (UK)w1 | 140 814 patients | Both sexes (any) | Any | Ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, total stroke, myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, death due to cardiovascular disease | Same database as in Nightingale 200418 and Becker 2007w11 |

| Velentgas 2004 (USA)w8 | 260 822 participants | Both sexes (any) | Any | Transient ischaemic attack, total stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, death due to cardiovascular disease | |

| Kurth 2005 (USA)w18 | 39 717 participants | Women (≥45) | Any, migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, total stroke | Same cohort, but shorter follow-up as in Kurth 2006w3 |

| Kurth 2006 (USA)w3 | 27 840 participants | Women (≥45) | Any, migraine with and without aura | Major cardiovascular disease,* ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, coronary revascularisation procedure, death due to cardiovascular disease | |

| Ahmed 2006 (USA)w9 | 873 participants | Women (any) | Any | Admission to hospital for angina, coronary revascularisation procedure, death due to cardiovascular disease | “Admission to hospital for angina” investigated |

| Becker 2007 (UK)w11 | 103 376 participants | Both sexes, women, men (≤80) | Any, migraine with and without aura | Transient ischaemic attack, total stroke | Same database as in Hall 2004w1 and Nightingale 200418 |

| Kurth 2007 (USA)w2 | 20 084 participants | Men (40-84) | Any | Major cardiovascular disease,* ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, coronary revascularisation procedure, death due to cardiovascular disease | |

| Liew 2007 (Australia)w19 | 1732 participants | Women, men (≥49) | Any, migraine with and without aura | Death due to coronary heart disease | |

| Kurth 2008 (USA)w17 | 27 519 participants | Women (≥45) | Migraine with and without aura | Major cardiovascular disease,* ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction | Same cohort and follow-up as in Kurth 2006w3; focus on interaction of vascular risk on association between migraine and cardiovascular disease |

| Cross sectional: | |||||

| Rose 2004 (USA)w21 | 12 409 participants | Women, men (45-64) | Migraine with and without aura | Coronary heart disease, angina | Cross sectional study, that presents “verified coronary heart disease events after headache onset,” heterogeneous coronary heart disease outcome (myocardial infarction, silent myocardial infarction, CABG, PTCA, fatal coronary heart disease) |

| Stang 2005 (USA)w6 | 12 750 participants | Both sexes (45-64) | Migraine with and without aura | Ischaemic stroke | Cross sectional study, but presents results for “incident ischaemic stroke” (verified stroke events restricted to first stroke and strokes occurring after onset of headaches) |

CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting; PTCA=percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

*Combined end point—first of any of ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death due to cardiovascular disease.

Study characteristics

Thirteen of the 25 studies were case-control studies,w4 w5 w10 w12-w16 w20 w22-w25 10 cohort studies,w1-w3 w7-w9 w11 w17-w19 and two cross sectional studies.w6 w21 Both cross sectional studies presented results for cardiovascular events after the diagnosis of migraine.

Eighteen studies presented results for any migrainew1-w3 w7-w13 w15 w16 w18 w19 w22-w25 and 16 for migraine with and without aura separately.w3-w6 w11-w14 w16-w21 w24 w25

The cardiovascular events investigated were heterogeneous. Three studies looked at the association of migraine with major cardiovascular disease,w2 w3 w17 16 with ischaemic stroke,w1-w6 w12-w18 w23-w25 three with transient ischaemic attacks,w8 w11 w12 three with combined ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attacks,w10 w20 w22 five with haemorrhagic stroke,w1 w10 w13 w18 w23 five with any stroke,w1 w8 w11 w13 w18 six with myocardial infarction,w1-w3 w7 w8 w17 five with angina,w2 w3 w8 w9 w21 three with coronary revascularisation procedures,w2 w3 w9 one with death due to coronary heart disease,w19 and five with death due to cardiovascular disease.w1-w3 w8 w9

Ten studies presented results for women only,w3 w4 w9 w10 w13 w14 w17 w18 w23 w25 one for men only,w2 seven for overall mixed cohorts of men and women without stratification by sex,w1 w5 w6 w8 w16 w20 w22 three for overall cohorts plus stratification by sex,w11 w12 w24 and four only for women and men separately.w7 w15 w19 w21

The age in the studies ranged from 15 to 80 years. Eleven presented results for participants aged less than 45w5 w7 w10-w14 w20 w23-w25 and eight for those aged 45 or more.w3 w6 w7 w11 w17-w19 w21 Five studies presented results stratified by smoking,w4 w13 w17 w24 w25 four stratified results for women according to oral contraceptive use,w4 w10 w13 w25 and one only included women using oral contraceptives.w23

Table 2 summarises the association between migraine and stroke in the included studies. Table 3 summarises the association between migraine and myocardial infarction, angina, and death due to cardiovascular disease. Table 4 shows the results from the pooled analyses, including measures of heterogeneity and publication bias.

Table 2.

Studies included for analyses investigating association between migraine and stroke*

| Study design, reference, and age range | Population | Oral contraceptive users | Smoking | Migraine type | Relative risk (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any stroke | Ischaemic stroke | Transient ischaemic attack | Haemorrhagic stroke | |||||

| Case-control | ||||||||

| Henrich 1989w16: | ||||||||

| 15-65 | Both sexes | — | — | Any | — | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.6) | — | — |

| 15-65 | Both sexes | — | — | Migraine with aura | — | 2.6 (1.1 to 6.6) | — | — |

| 15-65 | Both sexes | — | — | Migraine without aura | — | 1.3 (0.5 to 3.6) | — | — |

| Tzourio 1993w24: | ||||||||

| 18-80 | Both sexes | — | — | Any | — | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.3) | — | — |

| 18-80 | Women | — | — | Any | — | 1.6 (0.7 to 3.5) | — | — |

| 18-80 | Men | — | — | Any | — | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.2) | — | — |

| 18-80 | Both sexes | — | — | Migraine with aura | — | 1.3 (0.5 to 3.8) | — | — |

| 18-80 | Both sexes | — | — | Migraine without aura | — | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.5) | — | — |

| <45 | Women | — | — | Any | — | 4.9 (1.1 to 21.4) | — | — |

| <45 | Women | — | Yes | Any | — | 10.2 (1.1 to 93.3) | — | — |

| Tzourio 1995w25: | ||||||||

| 18-44 | Women | — | — | Any | — | 3.5 (1.8 to 6.4) | — | — |

| 18-44 | Women | — | — | Migraine with aura | — | 6.2 (2.1 to 18.0) | — | — |

| 18-44 | Women | — | — | Migraine without aura | — | 3.0 (1.5 to 5.8) | — | — |

| 18-44 | Women | Current | — | Any | — | 13.9 (5.5 to 35.1) | — | — |

| 18-44 | Women | — | Yes | Any | — | 10.2 (3.5 to 29.9) | — | — |

| Carolei 1996w12: | ||||||||

| 15-44 | Both sexes | — | — | Any | — | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.4) | 2.5 (1.2 to 4.9) | — |

| 15-44 | Both sexes | — | — | Migraine with aura | — | 8.6 (1.0 to 75) | 3.3 (0.6 to 20) | — |

| 15-44 | Both sexes | — | — | Migraine without aura | — | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.0) | 2.3 (1.1 to 4.9) | — |

| Haapaniemi 1997w15: | ||||||||

| 16-60 | Men | — | — | Any | — | 2.12 (1.05 to 2.95) | — | — |

| Schwartz 1998w23: | ||||||||

| 18-44 | Women | Current | — | Any | — | 2.08 (1.19 to 3.65) | — | 2.15 (0.85 to 5.45) |

| Chang 1999w13: | ||||||||

| 20-44 | Women | — | — | Any | 1.78 (1.14 to 2.77) | 3.54 (1.30 to 9.61) | — | 1.10 (0.63 to 1.94) |

| 20-44 | Women | — | — | Migraine with aura | 1.62 (0.98 to 2.67) | 3.81 (1.26 to 11.5) | — | 0.86 (0.44 to 1.67) |

| 20-44 | Women | — | — | Migraine without aura | 2.25 (1.10 to 4.63) | 2.97 (0.66 to 13.5) | — | 1.84 (0.77 to 4.39) |

| 20-44 | Women | Not current | — | Any | — | 2.27 (0.69 to 7.47) | — | 1.13 (0.60 to 2.12) |

| 20-44 | Women | Current | — | Any | — | 16.9 (2.72 to 106) | — | 1.10 (0.40 to 2.97) |

| 20-44 | Women | — | No | Any | — | 1.56 (0.41 to 5.85) | — | 0.75 (0.31 to 1.79) |

| 20-44 | Women | — | Yes | Any | — | 7.39 (2.14 to 25.5) | — | 2.66 (1.29 to 5.49) |

| MacClellan 2007w4: | ||||||||

| 15-49 | Women | — | — | Migraine with aura | — | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | — | — |

| 15-49 | Women | — | — | Migraine without aura | — | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.5) | — | — |

| 15-49 | Women | — | Yes | Migraine with aura | — | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.3) | — | — |

| 15-49 | Women | Current | Yes | Migraine with aura | — | 10.0 (1.4 to 73.7) | — | — |

| Cohort | ||||||||

| Hall 2004w1: | ||||||||

| Any | Both sexes | — | — | Any | 1.52 (1.29 to 1.78) | 2.49 (1.62 to 3.83) | — | 1.34 (0.90 to 1.99) |

| Velentgas 2004w8: | ||||||||

| Any | Both sexes | — | — | Any | 1.67 (1.31 to 2.13) | — | 2.24 (1.63 to 3.09) | — |

| Kurth 2005w18: | ||||||||

| ≥45 | Women | — | — | Any | 1.23 (0.90 to 1.69) | 1.36 (0.97 to 1.92)† | — | 0.78 (0.33 to 1.82) |

| Kurth 2006w3: | ||||||||

| ≥45 | Women | — | — | Any | — | 1.22 (0.88 to 1.68) | — | — |

| ≥45 | Women | — | — | Migraine with aura | — | 1.91 (1.17 to 3.10) | — | — |

| ≥45 | Women | — | — | Migraine without aura | — | 1.27 (0.77 to 2.09) | — | — |

| Becker 2007w11: | ||||||||

| ≤80 | Both sexes | — | — | Any | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.9)† | — | 2.4 (1.8 to 3.3) | — |

| Kurth 2007w2: | ||||||||

| 40-84 | Men | — | — | Any | — | 1.12 (0.84 to 1.50) | — | — |

| Cross sectional | ||||||||

| Stang 2005w6: | ||||||||

| 45-64 | Both sexes | — | — | Migraine with aura | — | 2.07 (0.96 to 4.44) | — | — |

| 45-64 | Both sexes | — | — | Migraine without aura | — | 0.86 (0.37 to 2.00) | — | — |

*Only effect estimates pertaining to our a priori defined categories for analyses are listed.

†Effect estimates not used for our analyses as competing studies were available.

Table 3.

Cohort studies included for analyses investigating association between migraine and myocardial infarction, angina, and death due to cardiovascular disease*

| Study and age range | Population | Migraine type | Relative risk (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction | Angina | Death due to cardiovascular disease | |||

| Sternfeld 1995w7: | |||||

| Any | Women | Any | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.0) | — | — |

| Any | Men | Any | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | — | — |

| Any | Women | Any | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.1) | — | — |

| Any | Men | Any | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.9) | — | — |

| Hall 2004w1: | |||||

| Any | Both sexes | Any | 1.15 (0.96 to 1.38) | — | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.13) |

| Velentgas 2004w8: | |||||

| Any | Both sexes | Any | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.15) | 1.33 (1.13 to 1.56) | 0.60 (0.33 to 1.09) |

| Kurth 2006w3: | |||||

| ≥45 | Women | Any | 1.41 (1.03 to 1.91) | 1.47 (1.17 to 1.86) | 1.63 (1.07 to 2.50) |

| ≥45 | Women | Migraine with aura | 2.08 (1.30 to 3.31) | 1.71 (1.16 to 2.53) | 2.33 (1.21 to 4.51) |

| ≥45 | Women | Migraine without aura | 1.22 (0.73 to 2.05) | 1.12 (0.75 to 1.66) | 1.06 (0.46 to 2.45) |

| Ahmed 2006w9: | |||||

| Any | Women | Any | — | 1.27 (0.93 to 1.75)† | 1.16 (0.20 to 6.7) |

| Kurth 2007w2: | |||||

| 40-84 | Men | Any | 1.42 (1.15 to 1.77) | 1.15 (0.99 to 1.33) | 1.07 (0.80 to 1.43) |

*Only effect estimates pertaining to our a priori defined categories for analyses are listed.

†Effect estimates not used for our analyses, as they failed to meet our a priori defined criteria for outcomes.

Table 4.

Association between migraine and cardiovascular events, heterogeneity, and publication bias

| Migraine type and cardiovascular disease event | No of studies | Relative risk (95% CI)* | Heterogeneity | Publication bias (P value) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | Degrees of freedom | P value | I2 (%) | Begg’s test | Egger’s test | ||||

| Any migraine type and ischaemic stroke: | |||||||||

| All studies (case-control and cohort)w1-w3 w12 w13 w15 w16 w24 w25 | 9 | 1.73 (1.31 to 2.29) | 22.9 | 8 | 0.004 | 65 | 0.095 | 0.045 | |

| Case-control studiesw12 w13 w15 w16 w24 w25 | 6 | 1.96 (1.39 to 2.76) | 8.7 | 5 | 0.12 | 42 | 0.35 | 0.34 | |

| Cohort studiesw1-w3 | 3 | 1.47 (0.95 to 2.27) | 9.7 | 2 | 0.008 | 79 | 0.12 | 0.10 | |

| Womenw3 w13 w24 w25 | 4 | 2.08 (1.13 to 3.84) | 11.0 | 3 | 0.01 | 73 | 0.50 | 0.22 | |

| Menw2 w15 w24 | 3 | 1.37 (0.89 to 2.11) | 4.6 | 2 | 0.1 | 57 | 0.6 | 0.72 | |

| Women and men <45 yearsw12 w13 w24 w25 | 4 | 2.65 (1.41 to 4.97) | 6.6 | 3 | 0.09 | 55 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Women <45 yearsw13 w24 w25 | 3 | 3.65 (2.21 to 6.04) | 0.17 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.34 | |

| Women ≥45 yearsw3 | 1 | 1.22 (0.88 to 1.68) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Women currently using oral contraceptivesw13 w23 w25 | 3 | 7.02 (1.51 to 32.68) | 14.5 | 2 | 0.001 | 86 | 0.6 | 0.4 | |

| Women currently not using oral contraceptivesw13 | 1 | 2.27 (0.69 to 7.47) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Smokersw13 w24 w25 | 3 | 9.03 (4.22 to 19.34) | 0.2 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.96 | |

| Non-smokersw13 | 1 | 1.56 (0.41 to 5.85) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Migraine with aura and ischaemic stroke: | |||||||||

| All studiesw3 w4 w6 w12 w13 w16 w24 w25 | 8 | 2.16 (1.53 to 3.03) | 11.5 | 7 | 0.12 | 39 | 0.026 | 0.02 | |

| Smokersw4 | 1 | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.3) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Women currently using oral contraceptivesw4 | 1 | Not given | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Women currently using oral contraceptives and smokingw4 | 1 | 10.0 (1.4 to 73.7) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Migraine without aura and ischaemic strokew3 w4 w6 w12 w13 w16 w24 w25 | 8 | 1.23 (0.90 to 1.69) | 11.4 | 7 | 0.12 | 39 | 0.32 | 0.48 | |

| Any migraine type and transient ischaemic attackw8 w11 w12 | 3 | 2.34 (1.90 to 2.88) | 0.13 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.68 | |

| Any migraine type and haemorrhagic strokew1 w13 w18 | 3 | 1.18 (0.87 to 1.60) | 1.4 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.002 | |

| Any migraine type and any strokew1 w8 w13 w18 | 4 | 1.53 (1.36 to 1.72) | 2.8 | 3 | 0.43 | 0 | 1.0 | 0.98 | |

| Any migraine type and myocardial infarction: | |||||||||

| All studiesw1-w3 w7 w8† | 8 | 1.12 (0.95 to 1.32) | 17.1 | 7 | 0.02 | 59 | 0.62 | 0.77 | |

| Womenw3 w7‡ | 3 | 1.14 (0.75 to 1.73) | 6.87 | 2 | 0.03 | 71 | 0.12 | 0.51 | |

| Menw2 w7‡ | 3 | 1.15 (0.81 to 1.64) | 5.36 | 2 | 0.07 | 63 | 0.60 | 0.44 | |

| Migraine with aura and myocardial infarctionw3 | 1 | 2.08 (1.30 to 3.31) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Migraine without aura and myocardial infarctionw3 | 1 | 1.22 (0.73 to 2.05) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Any migraine type and angina: | |||||||||

| All studiesw2 w3 w8 | 3 | 1.29 (1.12 to 1.47) | 3.58 | 2 | 0.17 | 44 | 0.12 | 0.36 | |

| Womenw3 | 1 | 1.47 (1.17 to 1.86) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Menw2 | 1 | 1.15 (0.99 to 1.33) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Migraine with aura and anginaw3 | 1 | 1.71 (1.16 to 2.53) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Migraine without aura and anginaw3 | 1 | 1.12 (0.75 to 1.66) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Any migraine type and death due to cardiovascular disease: | |||||||||

| All studiesw1-w3 w8 w9 | 5 | 1.03 (0.79 to 1.34) | 8.6 | 4 | 0.07 | 54 | 1.0 | 0.9 | |

| Womenw3 w9 | 2 | 1.60 (1.06 to 2.42) | 0.14 | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.32 | — | |

| Menw2 | 1 | 1.07 (0.80 to 1.43) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Migraine with aura and death due to cardiovascular diseasew3 | 1 | 2.33 (1.21 to 4.51) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Migraine without aura and death due to cardiovascular diseasew3 | 1 | 1.06 (0.46 to 2.45) | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

*From random effects model.

†Four study cohorts from one paper.

‡Two study cohorts from one paper.

Association between migraine and stroke

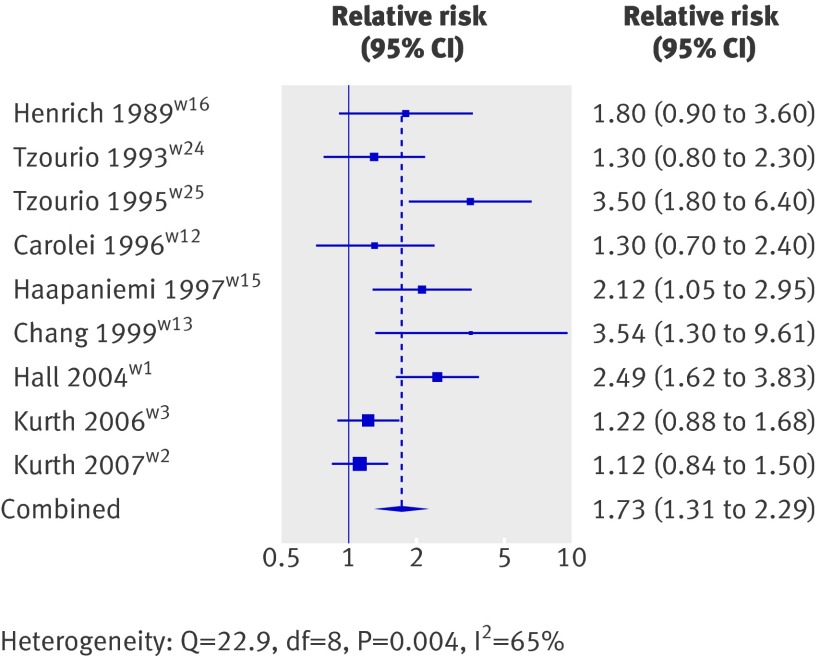

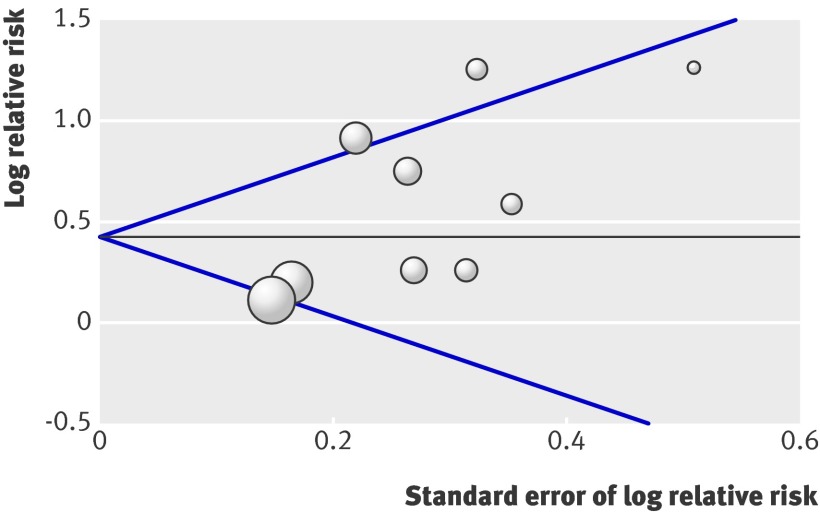

Nine studies investigated the association between any migraine and ischaemic stroke, which fulfilled the inclusion criteria.w1-w3 w12 w13 w15 w16 w24 w25 The pooled relative risks were 1.73 (95% confidence interval 1.31 to 2.29) for all studies (fig 2), 1.96 (1.39 to 2.76) for the six case-control studies,w12 w13 w15 w16 w24 w25 and 1.47 (0.95 to 2.27) for the three cohort studies.w1-w3 Heterogeneity was moderate across all studies (I2=65%); less for case-control studies (I2=42%) than cohort studies (I2=79%). Meta-regression showed that study type (case-control v cohort) was not a significant source of heterogeneity (P=0.3), and accounted for only 6.8% of the variance across all studies. Further analysis suggested an increased risk of ischaemic stroke among women (pooled relative risk 2.08, 95% confidence interval 1.13 to 3.84) but not among men (1.37, 0.89 to 2.11). Meta-regression did not, however, indicate that sex accounts for significant heterogeneity across the studies (P=0.31). The risk for people with migraine aged less than 45 (2.65, 1.41 to 4.97) was higher than for the overall group, which was more pronounced among women (3.65, 2.21 to 6.04). The risk of ischaemic stroke seemed to be further increased among smokers (9.03, 4.22 to 19.34) and women currently using oral contraceptives (7.02, 1.51 to 32.68). Formal investigation using Begg’s test indicated no publication bias (P=0.095), whereas Egger’s test suggested some publication bias (P=0.045). The funnel plot is presented in fig 3.

Fig 2 Association between any migraine and ischaemic stroke (all studies)

Fig 3 Funnel plot for studies investigating association between any migraine and ischaemic stroke

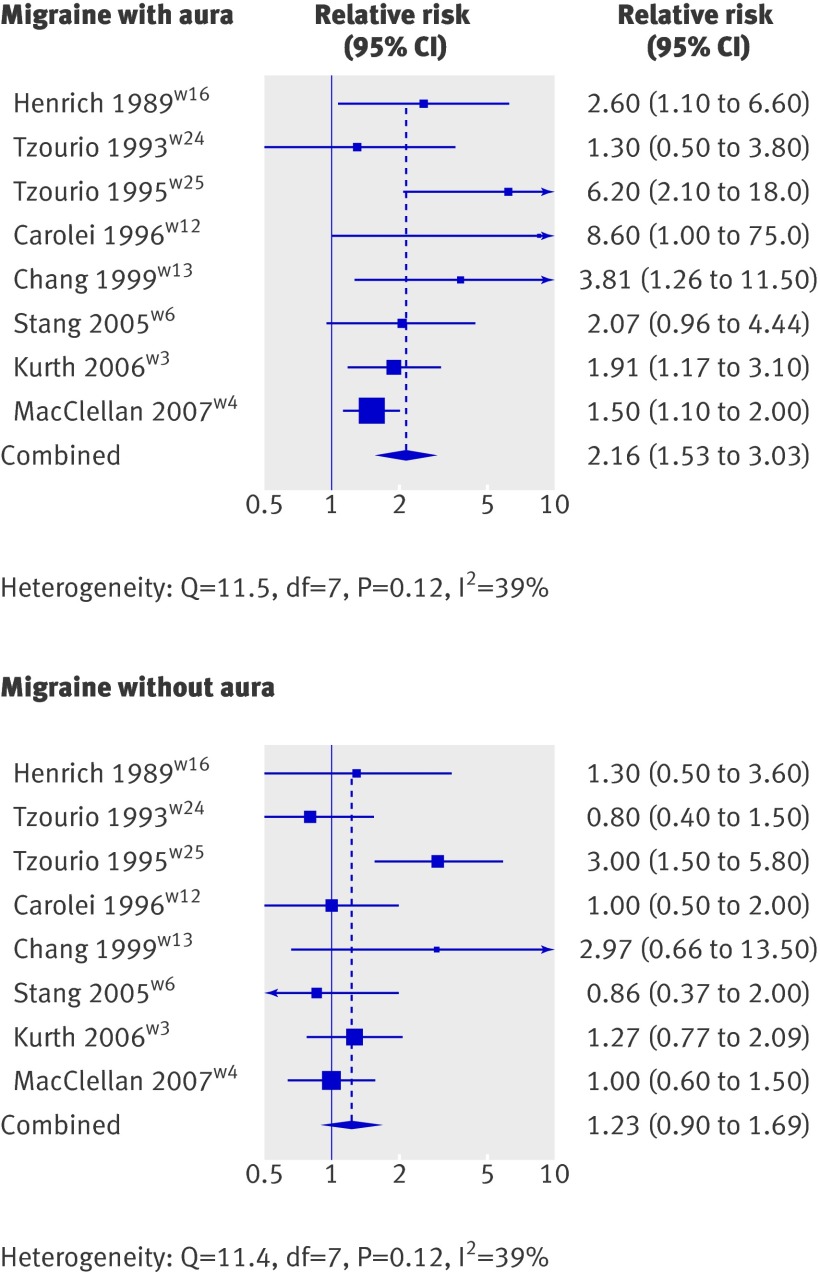

Eight studies investigated the association between migraine and ischaemic stroke stratified by migraine aura status.w3 w4 w6 w12 w13 w16 w24 w25 Pooled analyses suggested a significantly increased risk of ischaemic stroke among people who had migraine with aura (2.16, 1.53 to 3.03) but not those who had migraine without aura (1.23, 0.90 to 1.69; fig 4). This agrees with results from meta-regression, which indicate that migraine aura status is a significant source of heterogeneity across studies (P=0.02) and that 42% of the variance between studies is explained by this variable.

Fig 4 Association between migraine with and without aura and ischaemic stroke

Three studies each investigated the association between any migraine and transient ischaemic attacksw8 w11 w12 and haemorrhagic stroke.w1 w13 w18 The risk of transient ischaemic attacks seemed to be increased more than twofold (2.34, 1.90 to 2.88), but there was no association with haemorrhagic stroke (1.18, 0.87 to 1.60).

Association between migraine and myocardial ischaemia

Eight studies (four cohorts from one paperw7) investigated the association between any migraine and myocardial infarction.w1-w3 w7 w8 Overall analyses (fig 5) and analyses stratified by sex did not suggest an increased risk. Although heterogeneity was moderate across the studies (I2=59%), it did not seem to be accounted for by sex (meta-regression P=1.00). Publication bias was not indicated (Begg’s test P=0.62; Egger’s test P=0.77). Only one study presented results stratified by migraine aura status.w3 Migraine with aura (relative risk 2.08, 95% confidence interval 1.30 to 3.31) but not migraine without aura seemed to be associated with a twofold increased risk of myocardial infarction.

Fig 5 Association between any migraine and myocardial infarction

Three studies investigated the association between migraine and angina.w2 w3 w8 Among participants with any migraine the risk of angina seemed to be slightly but significantly increased (pooled relative risk 1.29, 95% confidence interval 1.12 to 1.47). Results from single studies suggest that the risk is higher in women than in men. The overall heterogeneity was low (I2=44%) and publication bias was not indicated (Begg’s test P=0.12; Egger’s test P=0.36). Only one study presented analyses stratified by migraine aura status,w3 which suggested a significantly increased risk in people who had migraine with aura (relative risk 1.71, 95% confidence interval 1.16 to 2.53) but not migraine without aura.

Association between migraine and death due to cardiovascular disease

Five studies investigated the association between any migraine and death due to cardiovascular disease.w1-w3 w8 w9 The analysis did not suggest an overall association (pooled relative risk 1.03, 95% confidence interval 0.79 to 1.34; fig 6). The two studies investigating the association among women found an increased risk (1.60, 1.06 to 2.42), which was not the case in another study among men. Heterogeneity was moderate across all studies (I2=54%) and publication bias was not indicated (Begg’s test P=1.0; Egger’s test P=0.9). The one study that investigated aura specific associations found an increased risk only among people who had migraine with aura (relative risk 2.33, 95% confidence interval 1.21 to 4.51) not migraine without aura.

Fig 6 Association between any migraine and death due to cardiovascular disease

Sensitivity analyses

The Galbraith plots for some analyses identified individual studies as important sources of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were carried out after excluding studies that did not fall within two standard deviations of the z score. For most of the analyses evaluating links between migraine and stroke, the associations did not change, albeit the effect estimates were lower. For example, after excluding three studies,w1 w2 w25 the pooled relative risk for the association between ischaemic stroke and any migraine was 1.54 (95% confidence interval 1.18 to 2.00), for migraine with aura (one study excludedw25) it was 1.80 (1.41 to 2.30), and for migraine without aura (one study excludedw25) it was 1.06 (0.83 to 1.37). However, after excluding one studyw25 the overall association between migraine and ischaemic stroke among women did not reach statistical significance (pooled relative risk 1.64, 0.94 to 2.86).

Although no significant overall association was shown between any migraine and myocardial infarction in the sensitivity analysis (1.12, 0.96 to 1.30; two studies excludedw2 w7), the analyses stratified by sex did: the pooled relative risk among women was 1.41 (95% confidence interval 1.10 to 1.81) and among men was 1.38 (1.14 to 1.69, one cohort from one study excluded in each casew7). In a further sensitivity analysis the results between any migraine and death due to cardiovascular disease were virtually unchanged (0.93, 0.81 to 1.10; one study excludedw3).

Discussion

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that people with migraine are at an increased risk of ischaemic stroke. This increased risk is only apparent in those who have migraine with aura and not in those with migraine without aura, the relative risk being double. In addition, the results suggest an approximately twofold higher risk among women compared with men. Factors that further increased the risk of ischaemic stroke were age less than 45 years, smoking, and use of oral contraceptives. Among people with migraine, the risk of transient ischaemic attacks seemed to be higher than that for ischaemic stroke. In contrast, we did not find an association with haemorrhagic stroke. We also did not find an association between any migraine type and myocardial infarction or death due to cardiovascular disease. Only one study investigated the association between migraine with aura and these events, which showed a twofold increased risk of myocardial infarction and death due to cardiovascular disease. The risk for angina was increased by about 30% in the pooled analysis.

Limitations of the study

The following limitations need to be considered. Firstly, migraine is biologically heterogeneous,19 and migraine with or without aura are extremes of a disease continuum.20 21 Although the International Classification of Headache Disorders has established criteria for migraine and migraine aura status,22 the clinical spectrum among patients is still wide and the classification of migraine or migraine aura may not capture this heterogeneity. Secondly, methods to obtain a diagnosis of migraine differed between studies. Some studies used the criteria of the International Classification of Headache Disorders,w5 w12 w13 w22 w24 w25 some used self administered questionnaires,w2-w4 w6 w19 w21 and others used databases from health insurance data.w1 w7 w8 w11 w23 Although the clinical diagnosis constitutes the gold standard, the other methods are also valid. Large scale population based studies using data from questionnaires have proved to be successful in reaching a valid diagnosis for migraine,23 24 25 w3 and information in health insurance databases is often based on medical records or claims. Thirdly, some of the included studies did not differentiate between migraine aura status,w1 w2 w15 w23 which is an important source of heterogeneity for the overall results. This is reflected by the results of the analyses between migraine and ischaemic stroke, indicating that migraine aura status accounts for 42% of the heterogeneity across the studies. Fourthly, in some studies the distinction between migraine with aura and migraine without aura relied on a single question, potentially leading to misclassification.w3 w17 Fifthly, there is a suggestion that publication bias may act in the pooled analyses for some of the associations investigated—for example, the P value from Egger’s test for the overall analysis between migraine and ischaemic stroke was marginally significant (P=0.045). In the funnel plot (fig 3) this may translate into the “gap” seen in the lower right hand corner, a potential indication that the results from smaller studies showing no association might not have been published. However, asymmetrical funnel plots are no proof of publication bias as they may arise from other underlying study characteristics. Unknown heterogeneity among the studies may account for that in part, which remained low to moderate even within the various subgroups investigated (table 4). Sixthly, cardiovascular disease is a collective term including different vascular events. Some of the studies provided results only for combined outcomes such as ischaemic stroke plus transient ischaemic attacksw10 w20 w22 and coronary heart disease (consisting of myocardial infarction, silent myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, fatal coronary heart disease)w21 or used specific outcomes such as “angina leading to hospitalization”w9 that could not be grouped with other studies investigating any angina. We applied stringent criteria for grouping the studies according to cardiovascular events, but even stroke subtypes, myocardial infarction, or death due to cardiovascular disease may involve diverse biological mechanisms. Thus, despite identifying 25 studies, we were left with no more than nine for our a priori defined categories; some of the 25 studies could not be grouped with the other studies.w5 w10 w14 w17 w19-w22 We chose this approach over one using weighting to reduce heterogeneity and to reflect more accurately the medical reality in clinical practice. Seventhly, for our overall analyses we a priori grouped studies irrespective of study type (case-control and cohort) and sex of participants. Indeed meta-regression supported these assumptions and did not identify study type or sex as significant sources of variability across studies between migraine and ischaemic stroke. Eighthly, we pooled odds ratios from case-control studies and hazard ratios from cohort studies to obtain pooled relative risk estimates. Given the lack of information on incidence rates from case-control studies, however, we could not determine the absolute risks or risk differences for the pooled data. From individual cohort studies it is suggested that the absolute risks for cardiovascular disease among people with migraine are considerably low.w3 w7 w8 Finally, we used only extractable data from the identified papers and did not contact authors to obtain additional information. Only one study, however, had insufficient data,14 and the outcome investigated was “overall stroke,” thus the results of our major outcomes would not have been altered.

Our results must be interpreted in view of the characteristics of the individual studies and the diseases investigated. Based on the vascular phenomena described in migraine,26 the association between migraine and cardiovascular disease has been the focus of attention for decades. While on the basis of current evidence the consensus seems to be that neural mechanisms are the main cause of migraine and that vascular findings only constitute epiphenomena,27 reports linking migraine with cardiovascular disease have accumulated. Most studies have investigated the association of migraine with ischaemic stroke and support a link between the two conditions, which is substantiated by a meta-analysis of data published until 2004.6 This previous meta-analysis reported a twofold increased risk of ischaemic stroke among people with migraine, which was similar between migraine with and migraine without aura, somewhat higher among people with migraine aged less than 45 years, and clearly increased among women using oral contraceptives. Our overall results agree in part with this meta-analysis, showing a 73% increased risk of ischaemic stroke for people with migraine, which was increased for smokers, women using oral contraceptives, and younger people. In contrast with the previous meta-analysis, however, our results suggest that an increased risk of ischaemic stroke is only apparent among people who have migraine with but not without aura. Several reasons may account for the discrepant finding. Firstly, three large population based studies have been published since the first meta-analysis.w1-w3 Secondly, the previous meta-analysis6 included competing studies utilising data from the same underlying study cohort.w13 w14 Thirdly, the previous meta-analysis considered studies investigating both “ischaemic stroke” and “ischaemic stroke plus transient ischaemic attacks” as a combined end point.w10 w20 w22 However, migraine aura, epileptic conditions, and presyncopal conditions may be misdiagnosed as transient ischaemic attacks, falsely increasing the effect estimate.28 This notion is also supported by our data, showing a higher risk for transient ischaemic attacks (pooled relative risk 2.34, 95% confidence interval 1.90 to 2.88) than for ischaemic stroke (1.73, 1.31 to 2.29). We excluded studies that only reported results for a combined outcome of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attacks.

Publications over the past years have focused not only on the association of migraine with ischaemic stroke but also on the association of migraine with other vascular events, including haemorrhagic stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, and death due to cardiovascular disease. Our pooled results do not suggest an association between overall migraine and haemorrhagic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death due to cardiovascular disease, whereas the risk of angina seems to be increased by 30%. Individual studies have reported a twofold increased risk of myocardial infarction, angina, and death due to cardiovascular disease for people who have migraine with aura,w3 but not for haemorrhagic stroke.w18

Pooled analyses further indicate that the risk of ischaemic stroke is significantly higher among women than among men. In contrast, the lack of an association between migraine and myocardial infarction did not differ between women and men. This may indicate a differential pathophysiology between migraine and ischaemic stroke and between migraine and myocardial infarction, as well as sex specific effects. Although the associations between migraine and angina and between migraine and death due to cardiovascular disease suggest a higher risk among women than among men, studies were too few to allow a reliable assessment. Certain conditions among women, especially young women, seem to be important determinants in increasing the risk of cardiovascular events, even in the absence of overt atherosclerotic disease. Sex hormones may be such candidates; they have been associated with risk of both migraine and cardiovascular events.29 In addition, their “magnitude of impact” may be much greater on the cervical-cranial circulation than on the coronary circulation. This needs further investigation.

Implications for clinical practice

The most consistent evidence was the increased risk of ischaemic stroke among people with migraine, which seems to be driven by migraine with aura. In addition, the risk seemed to be further magnified by being younger (<45 years), being female, smoking, and using oral contraceptives. Thus, in particular, young women who have migraine with aura should be strongly advised to stop smoking, and methods of birth control other than oral contraceptives may be considered. Some evidence shows that among women who have migraine with aura the combination of smoking and use of oral contraceptives leads to the highest risk estimates for ischaemic stroke.w4 Firm evidence on the association of migraine and other ischaemic vascular events is lacking. Therefore patients with migraine should be treated the same as any other patient without migraine: they should be screened for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, adverse lipid profile, and increased risk of coronary heart disease and, if appropriate, these risk factors should be modified.

Directions for future research

Additional research is needed to delineate in more detail the association between migraine and cardiovascular disease. Future studies need to be adequately powered, should use a strict diagnosis of migraine, should include aura status, should present results for clearly defined cardiovascular events such as ischaemic stroke and myocardial infarction (not just combined end points), and should present results stratified by important and biologically meaningful modifying factors in addition to overall analyses. Furthermore, studies need to control for risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease. Finally, markers of migraine severity, including frequency of attacks and frequency of aura should be considered in the association between migraine and cardiovascular disease.

What is already known on this topic

Migraine has been associated with an increased risk of ischaemic stroke

A meta-analysis reported a twofold increased risk of ischaemic stroke among people who had migraine both with and without aura

Subsequent large case-control and cohort studies investigated the association between migraine and various vascular events, including stroke subtypes, myocardial infarction, and death due to cardiovascular disease

What this study adds

In this meta-analysis the risk of ischaemic stroke was approximately doubled among people with migraine, which was apparent for migraine with aura but not migraine without aura

The risk was further increased by being female, age less than 45 years, smoking, and oral contraceptive use

There was no association between migraine and myocardial infarction or death due to cardiovascular disease

Contributors: MS and TK conceived and designed the study, analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript. MS, PMR, and TK acquired the data. All authors had full access to the data, take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, interpreted the data, critically revised the draft for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be published. MS and TK reserved the final decision in writing and in the decision to submit the article for publication. MS and TK are guarantors.

Funding: This study was funded by an investigator initiated (TK) research grant from Merck (IISP-35437). The sponsor played no role in the study design or in the collection and analysis of the data.

Competing interests: MS has received an investigator initiated research grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and honorariums from LEK Consulting for telephone surveys. MEB is a full time employee of Merck Research Laboratories; he has carried out research, been on the advisory board, or has been in the speaker’s bureau of several pharmaceutical companies that market drugs for migraine. JEB has received investigator initiated research funding and support from the National Institutes of Health and Dow Corning; research support for pills or packaging from Bayer Heath Care and the Natural Source Vitamin E Association; and an honorarium from Bayer for speaking engagements. RBL has consulted for, carried out studies funded by, or received lecture honorariums from Merck and other companies including Allergan, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson and Johnson, Minster, and Neuralieve. He has stock options in Minster and Neuralieve. TK has received investigator initiated research funding from the National Institutes of Health, McNeil Consumer & Specialty Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and Wyeth Consumer Healthcare; he is a consultant to i3 Drug Safety and World Health Information Science Consultants, LLC, and he has received honorariums from Genzyme, Merck, and Pfizer for educational lectures.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3914

References

- 1.Haut SR, Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Chronic disorders with episodic manifestations: focus on epilepsy and migraine. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:148-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipton RB, Bigal ME. The epidemiology of migraine. Am J Med 2005;118:S3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silberstein SD. Migraine. Lancet 2004;363:381-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tietjen GE. Migraine as a systemic disorder. Neurology 2007;68:1555-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanmolkot FH, Van Bortel LM, de Hoon JN. Altered arterial function in migraine of recent onset. Neurology 2007;68:1563-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etminan M, Takkouche B, Isorna FC, Samii A. Risk of ischaemic stroke in people with migraine: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ 2005;330:63. 10.1136/bmj.38302.504063.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galbraith RF. A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Stat Med 1988;7:889-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088-101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buring JE, Hebert P, Romero J, Kittross A, Cook N, Manson J, et al. Migraine and subsequent risk of stroke in the physicians’ health study. Arch Neurol 1995;52:129-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook NR, Bensenor IM, Lotufo PA, Lee IM, Skerrett PJ, Chown MJ, et al. Migraine and coronary heart disease in women and men. Headache 2002;42:715-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lidegaard O. Oral contraceptives, pregnancy and the risk of cerebral thromboembolism: the influence of diabetes, hypertension, migraine and previous thrombotic disease. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;102:153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merikangas KR, Fenton BT, Cheng SH, Stolar MJ, Risch N. Association between migraine and stroke in a large-scale epidemiological study of the United States. Arch Neurol 1997;54:362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell P, Wang JJ, Currie J, Cumming RG, Smith W. Prevalence and vascular associations with migraine in older Australians. Aust NZ J Med 1998;28:627-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosek A, Marom R, Korczyn AD, Bornstein N. A history of migraine is not a risk factor to develop an ischemic stroke in the elderly. Headache 2001;41:399-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nightingale AL, Farmer RD. Ischemic stroke in young women: a nested case-control study using the UK General Practice Research Database. Stroke 2004;35:1574-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulder EJ, Van Baal C, Gaist D, Kallela M, Kaprio J, Svensson DA, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on migraine: a twin study across six countries. Twin Res 2003;6:422-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ligthart L, Boomsma DI, Martin NG, Stubbe JH, Nyholt DR. Migraine with aura and migraine without aura are not distinct entities: further evidence from a large Dutch population study. Twin Res Hum Genet 2006;9:54-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyholt DR, Gillespie NG, Heath AC, Merikangas KR, Duffy DL, Martin NG. Latent class and genetic analysis does not support migraine with aura and migraine without aura as separate entities. Genet Epidemiol 2004;26:231-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders. 2nd ed. Cephalalgia 2004;24:S9-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Launer LJ, Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD. The prevalence and characteristics of migraine in a population-based cohort: the GEM study. Neurology 1999;53:537-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 2001;41:646-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schürks M, Buring JE, Kurth T. Agreement of self-reported migraine with ICHD-II criteria in the women’s health study. Cephalalgia 2009;29:1086-90. Epub 2009 Mar 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boes CJ, Dalessio DJ. The history of migraine from Hippocrates to Harold Wolff. In: Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, eds. Wolff’s Headache and other head pain. 8th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- 27.Pietrobon D, Striessnig J. Neurobiology of migraine. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003;4:386-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diener HC, Kurth T. Is migraine a risk factor for stroke? Neurology 2005;64:1496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bousser MG. Estrogens, migraine, and stroke. Stroke 2004;35:S2652-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]