Abstract

Objectives:

Changes in health following retirement are poorly understood. We used serial measurements to assess the effect of retirement on sleep disturbances.

Design:

Prospective cohort study.

Setting:

The French national gas and electricity company.

Participants:

Fourteen thousand seven hundred fourteen retired employees (79% men).

Measurements and Results:

Annual survey measurements of sleep disturbances ranging from 7 years before to 7 years after retirement (a mean of 12 measurements). Before retirement 22.2% to 24.6% of participants reported having disturbed sleep. According to repeated-measures logistic-regression analysis with generalized estimating equations estimation, the odds ratio (OR) for having a sleep disturbance in the postretirement period was 0.74 (95% confidence interval 0.71-0.77), compared with having a sleep disturbance in the preretirement period. The postretirement improvement in sleep was more pronounced in men (OR 0.66 [0.63-0.69]) than in women (OR 0.89 [0.84-0.95]) and in higher-grade workers than lower-grade workers. Postretirement sleep improvement was explained by the combination of preretirement risk factors suggesting removal of work-related exposures as a mechanism. The only exception to the general improvement in sleep after retirement was related to retirement on health grounds. In this group of participants, there was an increase in sleep disturbances following retirement.

Conclusions:

Repeated measurements provide strong evidence for a substantial and sustained decrease in sleep disturbances following retirement. The possibility that the health and well-being of individuals are significantly worse when in employment than following retirement presents a great challenge to improve the quality of work life in Western societies in which the cost of the aging population can only be met through an increase in average retirement age.

Citation:

Vahtera J; Westerlund H; Hall M; Sjösten N; Kivimäki M; Salo P; Ferrie JE; Jokela M; Pentti J; Singh-Manoux A; Goldberg M; Zins M. Effect of retirement on sleep disturbances: the GAZEL prospective cohort study. SLEEP 2009;32(11):1459-1466.

Keywords: Retirement, sleep disturbances, trajectory, longitudinal, cohort study

IN INDUSTRIAL SOCIETIES WORLDWIDE, LARGE POSTWAR BABY-BOOMER GENERATIONS ARE ENTERING THE FINAL PHASE OF THEIR WORKING LIVES, Moving out of the active labor force into retirement and the postretirement “third age.”1,2 Considering the substantial societal and economic impact of these sociodemographic changes, relatively little is known about the consequences of the retirement transition for health trajectories. Previous research on the health consequences of retirement, based on relatively short follow-up periods and a severely restricted number of outcome measurements, has produced conflicting results. Some studies have shown that retirement is associated with both improved3–5 and deteriorating mental health,6–8 whereas other studies have found retirement to be unrelated to either mental or physical health.9–11 These mixed findings suggest that the impact of retirement on health is complex and includes a host of risk factors (e.g., poor health at retirement and loss of social networks) and protective factors (e.g., loss of job stress and more time to focus on health and social relationships).

Sleep disturbances have seldom been used as outcomes in retirement studies, even though disturbed sleep is common in older adults and increases with age. Studies of the prevalence of insomnia in the general population demonstrate a median prevalence for all insomnia of about 35%, with a range of 10% to 15% being assessed as moderate to severe disorders.12 Sleep disturbances have been shown to be associated with a range of adverse outcomes, including impaired cognitive functioning,13 decreased quality of life,14 reduced immune functioning,15 and the metabolic syndrome,16,17 as well as increased risk of mood and anxiety disorders,18 absenteeism and early retirement,19,20 occupational accidents,21 and greater health care costs.22 There is also strong evidence that, during the working years, work schedules and work stress adversely affect sleep. For instance, shift work is a significant correlate of insomnia in industrialized nations,23 and heightened levels of stress are associated with cognitive and physiologic arousal, which interfere with sleep.24–26 Moreover, several epidemiologic studies have shown a strong link between work stress and disturbed sleep.27–30

Findings from the few existing studies on associations between retirement from work and sleep outcomes, mostly cross-sectional, have produced mixed findings. One study observed a higher prevalence of sleep disturbances after retirement,31 whereas others have reported better sleep quality, such as longer sleep time and fewer problems with early awakenings and difficulties in getting back to sleep.32,33 To our knowledge, no published evidence exists on trajectories of changes in sleep before and after retirement over an extended time window. Because retirement has been characterized as either an additional stressor or a relief, depending on the findings referred to in the literature,3–8 we did not specify directional a-priori hypotheses regarding the prevalence of sleep disturbance during the retirement transition. Due to the impact of sleep on health and functioning, longitudinal information on retirement-related sleep changes would help to answer questions on the long-term consequences of retirement on health. Thus, the aim of this study was to explore the effect of retirement on sleep disturbances using a longitudinal design with annual self-reported measures of sleep disturbances from up to 7 years before and 7 years after retirement. The study is based on a French occupational cohort with 2 key characteristics: stable employment, similar to public-sector employment, and a statutory age of retirement between 55 and 60 years.

METHODS

Study Population

The GAZEL cohort was established in 1989 and comprises employees from the French national gas and electricity company: Electricite de France-Gaz de France (EDF-GDF).34 At baseline, 20,625 employees (73% men), aged 35 to 50 years, gave consent to participate. EDF-GDF employees hold a civil servant–like status that guarantees job stability and opportunities for occupational mobility. Typically, employees are hired when they are in their 20s and stay with the company until retirement (usually around 55 years of age). Retirees' pensions are paid by the company. Because of these characteristics, study follow-up is very thorough, and losses to follow-up are small.35 GAZEL participants are followed with an annual postal questionnaire mailed to participants' homes requesting data on health, lifestyle, individual, familial, social and occupational factors. Additionally, self-report data are linked to validated occupational and health data collected by the company, including data on retirement, long-standing work disability due to serious diseases, and sickness absence.

In this study, we analyzed data from the GAZEL participants who retired between 1990 and 2006. Of all 18,884 retirees, we included in the study only those who provided information on sleep disturbances at least once before and once after the year of retirement. Thus, the cohort consisted of 14,714 employees (11,581 men and 3133 women) whose mean age at retirement was 55 years (range 37-63).

Data on Retirement

Because all pensions are paid by EDF-GDF, company data on retirement are comprehensive and accurate. The statutory age of retirement is between 55 and 60 years depending on the type of job. Although partial retirement is rare, retirement can, in some cases, occur before the age of 55. For example, women who have at least 3 children can retire after 15 years of service, their pension being proportionate to the years served. Retirement on health grounds can be granted in the event of long-standing illness or disability. Illness or disability claims are validated by the social security department of EDF-GDF. From the company records, we obtained data on official retirement, long-standing illness or disability, and sickness absence. We defined the year and type of retirement according to the first of the following events: receipt of an official retirement pension (statutory retirement), or long-standing illness or disability, or having more than 650 days of sickness absence in 2 subsequent years (retirement on health grounds). In the last case, the first year is considered as a year of retirement.

Sleep Disturbances

Data on sleep were obtained from questionnaires for the years 1989 through 2007. An affirmative response (yes) to a question on the occurrence of sleep disturbances (troubles du sommeil) from a systematic checklist of more 50 medical conditions experienced during the past 12 months was used as an indicator of sleep disturbances in the survey year.36 This was coded as a binary variable with the response category 1 for those who gave an affirmative response and the category 0 for those who did not endorse an affirmative response. We took into account all annual sleep measurements over a 15-year time window, which ranged from 7 years prior to retirement to 7 years after retirement, using the year of retirement as year 0.

Preretirement Covariates

Demographic Factors

Demographic factors included sex, age at retirement, and marital status, the latter derived from the survey immediately prior to retirement (married or cohabiting vs single, divorced, or widowed).

Work-related Factors

Derived from the EDF-GDF records, employment grade immediately prior to retirement was classified into 3 groups: high grade (managers), intermediate grade (technical staff, line managers, and administrative associate professionals), and lower grade (clerical and manual workers), based on categorizations from the French National Statistics Institute. Night work, never versus occasionally or regularly, was derived from the baseline survey. For psychological and physical job demands and job satisfaction, measured on an 8-point scale,37 we used means of the average over the preretirement period measurements of each individual and categorized these into tertiles.

Health-related Behaviors

Questionnaire data on the maximum amount of beer, wine, and spirits consumed daily were transformed into units of alcohol per day. The average number of units over the preretirement period was classified as 0 to 3 units or more than 3 units.38 In a similar way, survey reports on height and weight were used to calculate the average body mass index (BMI) over the preretirement period to identify normal-weight (BMI ≤ 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0-29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥ 30.0 kg/m2) participants.39

Health-related Factors

Self-rated health was assessed on an 8-point scale (1 = very good.…8 = very poor). The mean rating over the preretirement time window was dichotomized by categorizing response scores 1 to 4 as good health and scores 5 to 8 as suboptimal health.40 The mean of preretirement responses to 2 items on mental and physical fatigue, responses on an 8-point scale, were used to identify participants experiencing fatigue (highest tertile vs other tertiles). Affirmative responses (yes) to a checklist of more than 50 chronic conditions were used to identify chronic diseases (cancer, diabetes, chronic bronchitis, asthma, angina, myocardial infarction, stroke, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis) (0 = no disease, 1 = at least 1 disease) and presence of depression (1989-1999 only) over the preretirement period.40

STATISTICAL METHODS

Associations between the preretirement covariates and sleep disturbances prior to retirement (0 = no disturbances in any of the 7 years before retirement, 1 = disturbances in any year before retirement) were analyzed using logistic regression adjusted for sex and age at retirement. Next we studied changes in sleep for up to 7 years before and 7 years after retirement in relation to the year of retirement. We applied a repeated-measures logistic regression analysis with the generalized estimating equations (GEE) method.41 This method takes into account the correlation between sleep measurements within persons, and it is not sensitive to missing cases at repeated measurements.

We first calculated the odds and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for sleep disturbances for every year before and after the year of retirement, adjusted for the relevant time of data collection (1989-99 or 2000-07). These odds were transformed to prevalence estimates, which were then used to characterize the sleep trajectory in relationship to retirement. To examine the effect of missing values in repeated measurements, we replicated these analyses in a subgroup of participants who had sleep data to year 7 after retirement.

In further analyses, we explored the extent to which preretirement covariates explained the shape of the trajectory for sleep disturbances in relation to retirement. First, we tested whether the shape of the sleep trajectory depended on the variable of interest by entering the interaction term “year × explanatory variable” into the repeated-measures logistic-regression models. If the interaction term was significant, we then calculated from these models the overall odds ratio (OR) and their 95% CI for postretirement sleep disturbances by contrasting the mean sleep disturbances after retirement with the mean sleep disturbances before retirement for each level of the potential explanatory factor. The models were adjusted for sex, age at retirement, year, and time of data collection.

Finally, to provide an illustration of the extent to which the trajectory for sleep disturbances in relationship to retirement could be accounted for by the preretirement covariates, we calculated predicted annual prevalence estimates for sleep disturbances over the 15-year time window for 2 hypothetical cases: 2 upper-grade men retired at the statutory age of 55, one with a low-risk profile (i.e., no health or health behavior–related risk factors) and the other with a high-risk profile (i.e., all independent health or health behavior–related risk factors associated with the shape of the sleep trajectory). We derived these estimates from a single repeated-measures logistic-regression analysis that included the interaction term “year × explanatory variable” for each risk factor in the model. The analyses were conducted using the SAS 9.1 program (SAS, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Of the 14,714 respondents included in the study cohort, 10,564 (72%) had retired by the age of 55 and 14,635 (99%) by the age of 60. The proportion of people who retired based on health reasons was only 4% (Table 1). Before retiring, 35% of the study cohort had occasionally or consistently worked night shifts, 54% were overweight or obese, 34% consumed more than 3 units of alcohol daily, 24% rated their health status as suboptimal, 49% reported having 1 or more chronic diseases, 32% reported having fatigue, and 17% reported having depression. The mean number of sleep measurements within the 15-year time window was 12.0 (range 2-15), with a mean of 5.7 measurements in the years before retirement and a mean of 5.5 measurements in the years after retirement. Table 1 also shows that sleep disturbances prior to retirement were strongly associated with work-related factors (e.g., high psychological and physical job demands and low job satisfaction), health problems (retirement on health grounds, suboptimal self-rated health, chronic disease, or depression), as well as both mental and physical fatigue. Other factors associated with disturbed sleep were female sex and living alone. Sleep disturbances were not associated with age at retirement, grade, previous nightshift work, or health-related behaviors.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and their association with sleep disturbances over the 7 years before retirement

| Covariate | No. (%) | Sleep disturbances before retirement |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95% CI | ||

| Sex | |||

| Men | 11581 (79) | 1 | |

| Women | 3133 (21) | 2.20 | 2.02-2.39 |

| Age at retirement, y | |||

| ≤ 53 | 4386 (30) | 0.94 | 0.87-1.02 |

| 54-56 | 7501 (51) | 1 | |

| ≥ 57 | 2827 (19) | 0.94 | 0.86-1.02 |

| Grade | |||

| Higher | 4864 (33) | 1 | |

| Intermediate | 8020 (55) | 1.06 | 0.98-1.14 |

| Lower | 1815 (12) | 1.04 | 0.93-1.17 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 13066 (89) | 1 | |

| Single, divorced or widowed | 1643 (11) | 1.52 | 1.37-1.69 |

| Type of retirement | |||

| Statutory | 14104 (96) | 1 | |

| Early | 610 (4) | 1.54 | 1.29-1.84 |

| Night work | |||

| No | 9569 (65) | 1 | |

| Yes | 5125 (35) | 1.02 | 0.95-1.10 |

| Job demands | |||

| Psychological | |||

| Low | 5097 (35) | 1 | |

| Moderate | 5254 (36) | 1.77 | 1.63-1.92 |

| High | 4320 (29) | 3.10 | 2.84-3.38 |

| Physical | |||

| Low | 5310 (36) | 1 | |

| Moderate | 4860 (33) | 1.25 | 1.16-1.35 |

| High | 4491 (31) | 1.58 | 1.46-1.72 |

| Job satisfaction | |||

| High | 3905 (28) | 1 | |

| Moderate | 5013 (36) | 1.46 | 1.34-1.59 |

| Low | 5009 (36) | 2.05 | 1.88-2.24 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||

| ≤ 24.9 | 13118 (92) | 1 | |

| 25.0- 29.9 | 13118 (92) | 1.03 | 0.96-1.11 |

| ≥ 30.0 | 1206 (8) | 1.10 | 0.97-1.24 |

| Alcohol consumption, unit/d | |||

| 0-3 | 8800 (66) | 1 | |

| > 3 | 4452 (34) | 1.02 | 0.95-1.10 |

| Suboptimal self-rated health | |||

| No | 11163 (76) | 1 | |

| Yes | 3534 (24) | 2.93 | 2.70-3.18 |

| Mental fatigue | |||

| No | 9970 (68) | 1 | |

| Yes | 4728 (32) | 4.59 | 4.26-4.96 |

| Physical fatigue | |||

| No | 9987 (68) | 1 | |

| Yes | 4715 (32) | 3.09 | 2.87-3.33 |

| Chronic disease | |||

| No | 7438 (51) | 1 | |

| Yes | 7276 (49) | 1.75 | 1.63-1.87 |

| Depression | |||

| No | 12156 (83) | 1 | |

| Yes | 2452 (17) | 7.28 | 6.47-8.18 |

Adjusted for sex and age at retirement

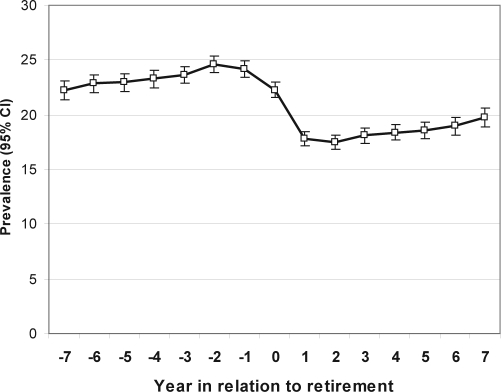

Figure 1 shows the annual prevalence of sleep disturbances in relation to retirement. The trajectory is characterized by 2 superimposed trends. There is a slowly increasing prevalence of sleep disturbances with increasing age, which can be observed both before and following retirement. However, the overall levels of reported sleep disturbances are markedly reduced in the years following retirement, compared with overall levels before retirement. During the years before retirement, 22.2% to 24.6% (95% CI 21.4%-25.4%) of participants reported disturbed sleep in any year. Sleep disturbance prevalence rates fell from 24.2% (23.4%-24.9%) in the last year before retirement to 17.8% (17.1%-18.4%) in the first year following retirement. From the first to the seventh year after retirement, this prevalence rate increased to 19.7% (18.8%-20.6%) but remained significantly lower than at any time point prior to retirement. Compared with the years before retirement, the OR of sleep disturbances in the years after retirement was 0.74 (0.71-0.77). When the analysis was restricted to the 8383 participants (57% of the total) for whom data were available for the seventh year after retirement, the findings were almost identical, with an OR of 0.72 (0.68-0.75) for sleep disturbances in the years before, compared with the years after, retirement. Thus, the reductions in sleep disturbances associated with retirement could not be attributed to losses to follow-up prior to the seventh year after retirement.

Figure 1.

Sleep disturbances in relationship to retirement. Annual prevalence (95% confidence interval [CI]) within ± 7 years to retirement derived from repeated-measures logistic-regression analyses with generalized estimating equations adjusted for time of data collection (1989-99 or 2000-07).

Table 2 shows the preretirement role played by the potential explanatory factors in influencing the shape of the trajectory for sleep disturbances related to retirement and the extent to which postretirement reductions in sleep disturbances were related to these variables. Of the demographic and work-related factors studied, sex, employment grade, nightshift work, and psychological job demands had a significant effect on sleep-disturbance profiles. Compared with the years before retirement, improvement in sleep in years 1 to 7 after retirement was more pronounced in men (P < 0.001), older age-groups (P = 0.008), those with higher employment grades (P < 0.001), nightshift workers (P = 0.002), and those exposed to high job demands (P < 0.001). A significant interaction effect was also observed between several health-related variables and the sleep-disturbance profiles. These included mental (P < 0.001) or physical fatigue (P = 0.007), self-rated health status (P = 0.02), and depression (P < 0.001). The most pronounced reduction in sleep disturbances was reported by participants with depression or mental fatigue prior to retirement. Among them, the OR for sleep disturbances in years 1 to 7 after retirement, compared with the 7 years before retirement, was 0.55 to 0.56 (0.52-0.60), whereas the corresponding OR was 0.76 to 0.86 (0.73-0.90) among those with no such problems. In all other groups studied, there was also a significant, although less-pronounced, improvement in sleep following retirement. The only exception was related to retirement on health grounds, after which there was a 1.46 times higher odds (95% CI 1.27-1.69) of sleep disturbances compared with the years before retirement (test of interaction between type of retirement and time P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Changes in Sleep Disturbances Following Retirementa

| Covariate | Interaction with time | Sleep disturbancesb |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | ||

| Sex | P < 0.0001 | ||

| Men | 0.66 | 0.63-0.69 | |

| Women | 0.89 | 0.84-0.95 | |

| Age at retirement, y | P = 0.008 | ||

| ≤ 53 | 0.77 | 0.72-0.81 | |

| 54-56 | 0.71 | 0.67-0.75 | |

| ≥ 57 | 0.72 | 0.67-0.78 | |

| Grade | P < 0.0001 | ||

| Higher | 0.63 | 0.59-0.67 | |

| Intermediate | 0.74 | 0.70-0.77 | |

| Lower | 0.85 | 0.78-0.92 | |

| Marital status | P = 0.823 | ||

| Type of retirement | P < 0.0001 | ||

| Statutory | 0.69 | 0.66-0.72 | |

| Early | 1.46 | 1.27-1.69 | |

| Night work | P = 0.002 | ||

| No | 0.75 | 0.72-0.78 | |

| Yes | 0.66 | 0.62-0.70 | |

| Job demands | |||

| Psychological | P < 0.0001 | ||

| Low | 0.91 | 0.86-0.97 | |

| Moderate | 0.72 | 0.68-0.76 | |

| High | 0.59 | 0.56-0.63 | |

| Physical | P = 0.784 | ||

| Job satisfaction | P = 0.952 | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | P = 0.006 | ||

| ≤ 24.9 | 0.77 | 0.73-0.81 | |

| 25.0- 29.9 | 0.66 | 0.62-0.70 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 0.74 | 0.67-0.82 | |

| Alcohol consumption, units/d | P = 0.140 | ||

| Suboptimal self-rated health | P = 0.019 | ||

| No | 0.74 | 0.71-0.78 | |

| Yes | 0.68 | 0.64-0.72 | |

| Mental fatigue | P <0.0001 | ||

| No | 0.86 | 0.82-0.90 | |

| Yes | 0.56 | 0.53-0.60 | |

| Physical fatigue | P = 0.007 | ||

| No | 0.74 | 0.70-0.78 | |

| Yes | 0.68 | 0.64-0.72 | |

| Physical illness | P = 0.378 | ||

| Depression | P <0.0001 | ||

| No | 0.76 | 0.73-0.80 | |

| Yes | 0.55 | 0.52-0.59 | |

Overall odds ratio (OR) for sleep disturbances and their 95% confidence interval (CI) in the 7 years after retirement, compared with the 7 years prior to retirement, are derived from repeated-measures logistic regression generalized estimating equations analyses adjusted for sex, age at retirement, year and time of data collection (1989-99 or 2000-07).

In year +1 to +7 compared with the years −1 to −7.

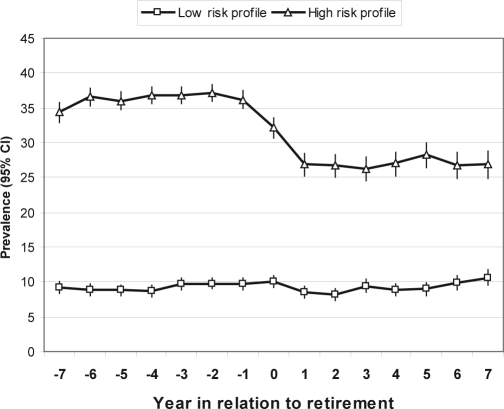

Figure 2 shows the annual prevalence of sleep disturbances in relation to retirement for the 2 hypothetical cases, one with a low-risk profile (no modifiable preretirement risk factors) and the other with a high-risk profile (all modifiable, independent, preretirement risk factors that shape the retirement-related sleep-disturbances trajectory). Initial analyses showed that the mutually adjusted interactions with time were significant for the following health or health behavior–related risk factors: BMI (P = 0.033), psychological job demands (P = 0.006), physical fatigue (P < 0.0001), mental fatigue (P < 0.0001), and depression (P < 0.0001) but not suboptimal self-rated health. For the high-risk–profile man, the mean percentage of annual sleep disturbances was 36.3% in the 7 preretirement years but 26% lower in the 7 postretirement years. For the low-risk–profile man, the mean percentage of annual sleep disturbances within the 7 preretirement years was 9.2%, identical to the 7 postretirement years. Thus, the effect of retirement on the trajectory of sleep disturbances was explained mostly by the preretirement risk factors in these data.

Figure 2.

Sleep disturbances in relation to retirement for participants with a low- and high-risk profile (high-profile: high job demands, overweight, mental and physical fatigue, and depression). Annual predicted prevalence (95% confidence interval [CI]) derived from repeated-measures logistic-regression analyses with generalized estimating equations.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine trajectories in sleep disturbances before and after retirement over an extended time window. In a large occupational cohort from France, we found that statutory retirement at age 55, on average, was followed by a sharp decrease in the prevalence of sleep disturbances. The odds of having disturbed sleep after retirement were 26% lower than during the preretirement period. The reduction in sleep disturbances after retirement was largely explained by preretirement risk factors, including high psychological demands at work, physical and mental fatigue, depression, and being overweight. The main strengths of our study were the usage of accurate data on retirement and annual sleep measurements collected prospectively over a 15-year time window.

Three limitations to this study must be noted. First, our measure of disturbed sleep was a 1-item, albeit annual, survey question concerning the occurrence of sleep disturbances during the past 12 months. In this study, the annual prevalence of sleep disturbances was 25% to 26% before retirement and 17% to 18% after it. These figures are in line with those reported for other measures of sleep disturbances elsewhere.12 For example, in the 2002 “Sleep in America” poll, 27% of the respondents categorized their sleep quality as fair or poor.13,42 Moreover, the stability of the sleep trajectory within the preretirement and postretirement time periods is consistent with the chronicity of long-term insomnia.43 Our findings of female sex, chronic diseases, and depression as risk factors for sleep disturbances are also consistent with previous results.23 However, we have no information on the type of sleep disorder reported by the participants, as our survey did not inquire about specific sleep symptoms and disorders.

Second, cohorts such as ours that are followed by surveys or examinations over an extended time period are subject to a healthy-survivor effect because participants are likely to permanently drop out due to severe illnesses as a function of time. Because sleep disturbances correlate with many severe illnesses, those subjects who were completely lost to follow-up probably did worse in terms of sleep than did their remaining counterparts. This implies that the trajectory observed may overestimate the long-term benefits of retirement. However, we were able to follow 8383 participants (57%) until the seventh year after retirement. Because the findings were almost identical, loss to follow-up is an unlikely source of bias in this study.

Third, the serial data for this study came from the French national gas and electricity company, in which the workers employed by the company operate throughout France, in both rural and urban areas, in a wide range of occupations. In comparison with most employees in the Western world, the personnel obviously enjoy benefits rarely seen elsewhere. Typically, employees have civil-servant status that guarantees job stability and opportunities for occupational mobility, they stay within the company their whole career until their retirement between 55 and 60 years of age, and their pensions (80% of their salary) are paid by the company. We do not know the extent to which the results seen in this cohort would hold for other working populations and conditions of employment.

Our results are consistent with those of some earlier studies, which found retirement from work to be associated with better sleep quality32,33 and improved mental health.3–5 However, contradictory results have also been reported.6–8 Retirement is nowadays seen as a life transition, which can be anticipated and even controlled to some extent.44 Whether retirement is experienced as a stressful or satisfying transition depends on organizational, financial, and family contexts and their interaction with psychological factors. Our findings suggest that positive outcomes in retirement transition, especially when encountering problems with health prior to retirement, are likely to be the result of removal from work-related harmful exposures rather than from actual health benefits from retirement.

Although improvement in sleep after retirement was observed in all demographic groups, there was significant variation in the extent to which sleep improved. The finding that women benefited from retirement less than men did is interesting because women not only report sleep disturbances more often than do men,21,45 but also retire earlier.7 Due to the accumulation of domestic responsibilities, women are generally exposed to long working hours at home.46 Following retirement, men may experience a notable decrease in their total working hours with no concomitant increase in domestic responsibilities, whereas, for retired women, more time may be needed for caregiving activities and domestic work. In addition, sleep disturbances are common in postmenopausal women,47 and, in our data, almost all women were likely to be postmenopausal after retirement, as they retired at the age of 53.9 years, on average (range 37 to 62). Thus, sex differences in social roles and expectations outside work, as well as postmenopausal symptoms affecting sleep, may explain why sleep improved substantially less in retired women than in retired men. Consistent with previous research showing the importance of socioeconomic circumstances in adjusting to retirement,3 we observed that retirement was more beneficial for employees in high employment grades than for those in lower grades. Unsurprisingly, nightshift workers benefited from retirement more than did day workers. Shift work is known to disrupt circadian rhythms and increases the risk of having insomnia.21

The influence of retirement on sleep disturbances did not depend on physical illnesses, but, instead, the most pronounced improvement in sleep was found among those participants who reported psychological problems, such as depression or mental fatigue, prior to retirement. The most common comorbidity of insomnia is psychiatric disorder, especially depression. The prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses is about 40% to 50% in patients with chronic insomnia.43 In our study, the prevalence of depression among those reporting sleep disturbances prior to retirement was 34% to 37%. The relationship between insomnia and depression has recently received significant research attention, as it has been found that insomnia represents a risk factor for the development of a subsequent depressive disorder.43,48,49 It has been suggested that insomnia and depression have a common pathology that makes the individual vulnerable to both conditions.43 Given the bidirectional relationship between chronic insomnia and depression, our finding of the lowering odds of having sustained sleep disturbances in depressed individuals by up to 45% in the years following retirement, compared with the years preceding retirement, is important. It is possible that the postretirement decrease in sleep disturbances helped this cohort recover from depression. However, more research is needed to examine this possibility.

The only exception to the general improvement in sleep after retirement was related to retirement on health grounds. In this group of participants, there was an increase in sleep disturbances following retirement. The retirement was granted on the grounds of physical illness, and poor physical health has been shown to predict early retirement50 and involuntary retirement to have adverse effects on health and well-being.44 It is possible that, in the cohort studied by us, the health problems leading to retirement on health grounds were so severe that they continued to disturb sleep in the postretirement years.43

Further research is needed to investigate underlying mechanisms, i.e., whether improvements in sleep after retirement are explained by the removal of exposure to adverse work characteristics, by positive changes in lifestyle, by changes in the way individuals rate their sleep, or by lower demands on health after work life. Further research is also needed to examine whether our findings are generalizable to other labor-market sectors and cultures.

In conclusion, intraindividual repeated measurements in the GAZEL cohort provide strong evidence for a substantial and sustained decrease of sleep disturbances following retirement. This retirement-related sleep trajectory was fully explained by the preretirement risk factors, suggesting that positive outcomes in retirement transition are likely to result from removal of work-related stress rather than to actual health benefits from retirement. The possibility that the health and well-being of individuals is significantly worse during employment, compared with after retirement, presents a great challenge to improve the quality of work life. Due to the increasing numbers of individuals living years beyond retirement age, governments in most Western countries seek to increase the economically active proportion of the population by pushing retirement age upward. At a time when people are expected to survive several decades beyond retirement and years spent in disability are costly, consideration should be given to the restructuring of work to enable older workers to remain economically active without compromising their future health.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ms. Alice Guéguen and Mr. Hans Helenius for their statistical comments.

The authors express their thanks to EDF-GDF, especially to the Service Général de Médecine de Contrôle and to the “Caisse centrale d'action sociale du personnel des industries électrique et gazière.” We also wish to acknowledge the Risques Postprofessionnels – Cohortes de l'Unité mixte 687 Inserm – CNAMTS team responsible for the GAZEL database management. The GAZEL Cohort Study was funded by EDF-GDF and INSERM and received grants from the “Cohortes Santé TGIR Program.”

Financial disclosure: JV, NS, MK and PS are supported by the Academy of Finland (grants #117604, #124271, #124322 and #129262) and MK is additionally supported by the BUPA Specialist research grant; HW is supported by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS, grants #2004-2021, #2007-1143); JEF is supported by the MRC (Grant number G8802774); AS-M is supported by a EUYRI award from the European Science Foundation.

Contributors: JV together with HW posed the question and designed and conducted the study. JV made all the analyses and carried the main responsibility of writing the paper. JV will act as guarantor of the paper. All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design or analysis and interpretation of data and (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and (3) gave final approval of the version to be published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oeppen J, Vaupel JW. Demography. Broken limits to life expectancy. Science. 2002;296:1029–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1069675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mein G, Martikainen P, Hemingway H, Stansfeld S, Marmot M. Is retirement good or bad for mental and physical health functioning? Whitehall II longitudinal study of civil servants. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:46–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drentea P. Retirement and mental health. J Aging Health. 2002;14:167–94. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buxton JW, Singleton N, Melzer D. The mental health of early retireesnational interview survey in Britain. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0866-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosse R, Aldwin CM, Levenson MR, Ekerdt DJ. Mental health differences among retirees and workers: findings from the Normative Aging Study. Psychol Aging. 1987;2:383–9. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.2.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alavinia SM, Burdorf A. Unemployment and retirement and ill-health: a cross-sectional analysis across European countries. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;82:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s00420-008-0304-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mojon-Azzi S, Sousa-Poza A, Widmer R. The effect of retirement on health: a panel analysis using data from the Swiss Household Panel. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137:581–5. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villamil E, Huppert FA, Melzer D. Low prevalence of depression and anxiety is linked to statutory retirement ages rather than personal work exit: a national survey. Psychol Med. 2006;36:999–1009. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butterworth P, Gill SC, Rodgers B, Anstey KJ, Villamil E, Melzer D. Retirement and mental health: analysis of the Australian national survey of mental health and well-being. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1179–91. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekerdt DJ, Bosse R, Goldie C. The effect of retirement on somatic complaints. J Psychosom Res. 1983;27:61–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(83)90110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sateia MJ, Doghramji K, Hauri PJ, Morin CM. Evaluation of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep. 2000;23:243–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altena E, Van Der Werf YD, Strijers RL, Van Someren EJ. Sleep loss affects vigilance: effects of chronic insomnia and sleep therapy. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:335–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zammit GK, Weiner J, Damato N, Sillup GP, McMillan CA. Quality of life in people with insomnia. Sleep. 1999;22:S379–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savard J, Laroche L, Simard S, Ivers H, Morin CM. Chronic insomnia and immune functioning. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:211–21. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000033126.22740.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jennings JR, Muldoon MF, Hall M, Buysse DJ, Manuck SB. Self-reported sleep quality is associated with the metabolic syndrome. Sleep. 2007;30:219–23. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall MH, Muldoon MF, Jennings JR, Buysse DJ, Flory JD, Manuck SB. Self-reported sleep duration is associated with the metabolic syndrome in midlife adults. Sleep. 2008;31:635–43. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neckelmann D, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Chronic insomnia as a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression. Sleep. 2007;30:873–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vahtera J, Pentti J, Helenius H, Kivimaki M. Sleep disturbances as a predictor of long-term increase in sickness absence among employees after family death or illness. Sleep. 2006;29:673–82. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.5.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivertsen B, Overland S, Neckelmann D, et al. The long-term effect of insomnia on work disability. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1018–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth T. Prevalence, associated risks, and treatment patterns of insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(10-3):42–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S, Walsh JK. The direct and indirect costs of untreated insomnia in adults in the United States. Sleep. 2007;30:263–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sateia MJ, Nowell PD. Insomnia. The Lancet. 2004;364:1959–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17480-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morin CM, Rodrigue S, Ivers H. Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:259–67. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000030391.09558.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall M, Thayer JF, Germain A, et al. Psychological stress is associated with heightened physiological arousal during NREM sleep in primary insomnia. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5:178–93. doi: 10.1080/15402000701263221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall M, Vasko R, Buysse D, et al. Acute stress affects heart rate variability during sleep. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:56–62. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106884.58744.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linton SJ. Does work stress predict insomnia? A prospective study. Br J Health Psychol. 2004;9:127–36. doi: 10.1348/135910704773891005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akerstedt T, Fredlund P, Gillberg M, Jansson B. Work load and work hours in relation to disturbed sleep and fatigue in a large representative sample. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:585–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ota A, Masue T, Yasuda N, Tsutsumi A, Mino Y, Ohara H. Association between psychosocial job characteristics and insomnia: an investigation using two relevant job stress models--the demand-control-support (DCS) model and the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) model. Sleep Med. 2005;6:353–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribet C, Derriennic F. Age, working conditions, and sleep disorders: a longitudinal analysis in the French cohort E.S.T.E.V. Sleep. 1999;22:491–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito Y, Tamakoshi A, Yamaki K, et al. Sleep disturbance and its correlates among elderly Japanese. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2000;30:85–100. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(99)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kronholm E, Hyyppa MT. Age-related sleep habits and retirement. Annals of clinical research. 1985;17:257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marquie JC, Foret J. Sleep, age, and shiftwork experience. J Sleep Res. 1999;8:297–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1999.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg M, Leclerc A, Bonenfant S, et al. Cohort profile: the GAZEL Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:32–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melchior M, Krieger N, Kawachi I, Berkman LF, Niedhammer I, Goldberg M. Work factors and occupational class disparities in sickness absence: findings from the GAZEL cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1206–12. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moneta GB, Leclerc A, Chastang JF, Tran PD, Goldberg M. Time-trend of sleep disorder in relation to night work: a study of sequential 1-year prevalences within the GAZEL cohort. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1133–41. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiron M, Bernard M, Lafont S, Lagarde E. Tiring job and work related injury road crashes in the GAZEL cohort. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40:1096–104. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nabi H, Consoli SM, Chastang JF, Chiron M, Lafont S, Lagarde E. Type A behavior pattern, risky driving behaviors, and serious road traffic accidents: a prospective study of the GAZEL cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:864–70. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO Consultation on Obesity. WHO Technical Report Series. Vol. 894. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic; pp. 8–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldberg P, Gueguen A, Schmaus A, Nakache JP, Goldberg M. Longitudinal study of associations between perceived health status and self reported diseases in the French GAZEL cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:233–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.4.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipsitz SR, Kim K, Zhao L. Analysis of repeated categorical data using generalized estimating equations. Stat Med. 1994;13:1149–63. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Dongen HP, Vitellaro KM, Dinges DF. Individual differences in adult human sleep and wakefulness: Leitmotif for a research agenda. Sleep. 2005;28:479–96. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roth T, Roehrs T. Insomnia: epidemiology, characteristics, and consequences. Clin Cornerstone. 2003;5:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(03)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Solinge H, Henkens K. Adjustment to and satisfaction with retirement: two of a kind? Psychol Aging. 2008;23:422–34. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leger D, Guilleminault C, Dreyfus JP, Delahaye C, Paillard M. Prevalence of insomnia in a survey of 12,778 adults in France. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ala-Mursula L, Vahtera J, Kouvonen A, et al. Long hours in paid and domestic work and subsequent sickness absence: does control over daily working hours matter? Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:608–16. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.023937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nelson HD. Menopause. Lancet. 2008;371:760–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60346-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harvey AG. Insomnia: symptom or diagnosis? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:1037–59. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep. 2008;31:473–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mein G, Martikainen P, Stansfeld SA, Brunner EJ, Fuhrer R, Marmot MG. Predictors of early retirement in British civil servants. Age Ageing. 2000;29:529–36. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]