Abstract

Objective

One in four emerging adults will experience a depressive episode between the ages of 18-25. We examined the lived experience of emerging adults with a focus on their treatment seeking, development, and the social context of their illness.

Method

In-depth interviews were conducted with 15 participants with major or minor depression. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using established qualitative methods.

Results

Emerging adults reported dynamic and complex interactions within and between thematic areas including identification as an individual with depression, interactions with the healthcare system, relationships with friends and family, and role transitions from childhood to adulthood. Depressed mood, concerns about self-identifying ones self as being depressed, the complexity of seeking care often without insurance or financial support, alienation from peers and family and a sense failure to achieve expected developmental milestones appeared to interact and exacerbate functional impairment.

Conclusions

Further research is needed to better understand and intervene upon pathways that lead to poor outcomes such as delayed milestones among emerging adults with depression. Health care providers should be conscious of the unique vulnerabilities posed by depressive disorders in this age group.

Keywords: emerging adulthood, depression, development

Introduction

Emerging adulthood presents a paradox of, on the one hand, robust physical health and relative optimism, and on the other hand, a high risk for depressive and behavioral disorders and developmental and social vulnerability [1, 18]. Emerging adults, defined herein as individuals 18-25 years of age, have the highest incidence and cumulative prevalence of depression of any age group (25% of emerging adults) [2-4]. Some evidence suggests the risk of depression in this age group has increased significantly in the last half century, while the age at first onset for many emerging adults has decreased [2]. Emerging adults with depression are more likely to experience marital and parenting problems, sexual dysfunction, nicotine dependence and substance abuse, work absenteeism, lower career satisfaction, and lower levels of educational attainment later in life than their non-depressed peers [2, 5-12]. A depressive episode during emerging adulthood can cause significant “secondary damage” to subsequent development and can cause substantial social morbidity [13-15].

Emerging adulthood represents a new, critical, and potentially problematic nexus of the normative developmental process and risk for depressive disorders [16, 17]. During emerging adulthood many of the culminating tasks of adolescence are finally attained, such as identity formation and role transitions, the formation of intimate romantic attachments, and independence from one's parents [18]. With increased mobility, more prolonged educational pathways, and rising median ages of marriage and parenthood, emerging adulthood is less well-defined and more unstable than in the past [10, 18]. While adolescence has historically been viewed as a time of transition and emotional turmoil, emerging adulthood has traditionally been seen as a time to ‘settle down and conform to productive adult life’. However, recent research suggests that this period of life marks a major transition of considerable change and significance. It is during this developmental period that the foundations of future adult life are established [19]. Some theories of emerging adulthood posit that this life event overload may exacerbate depressive symptoms or precipitate episodes [19].

Emerging adults experiencing depressive disorders must navigate both developmental processes and treatment regimens within a changing postmodern social context. In developed economies, emerging adults experience unparalleled freedom of choice in what some have described as prolonged adolescence [13]. Traditional interpretations of depressive disorders such as those offered by religion and family and an increase in media influence (e.g. advertising for anti-depressant medications) impact decision-making processes concerning mental health [20-23]. Similarly, emerging adults receive substantially less structural support than prior birth cohorts (e.g. declining employment-related security (European Union) or lack of health insurance coverage (United States)) [24, 25]. This is important because emerging adults with depression have one of the lowest rates of care-seeking (37%) and of receiving high quality treatment (20%) when compared to other adult age groups in the United States [2, 26, 27].

Though the incidence, adverse impacts, and social and behavioral vulnerabilities associated with depressive disorders in emerging adulthood have been studied [2, 8, 10, 13, 15], we have little understanding of how today's emerging adults with depressive disorders navigate treatment seeking, developmental tasks (such as identity formation and role transitions in the context of social fluidity) and the vulnerabilities that characterize contemporary developed societies. A better understanding of this complex process could be used to both generate causal hypotheses for treatment and functional outcomes as well as to facilitate intervention design. To examine this systematically, we performed in-depth, semi-structured interviews that explored the lived experience of a diverse group of emerging adults with depressive disorders. The intent of this investigation was to obtain a relatively unconstrained description of the ways in which depression is construed and experienced among a sample of emerging adults. We reasoned that these qualitative methods would be best suited to gain an understanding of the complex interactions between depressive disorders, treatment seeking, developmental processes, and social context. A qualitative approach was chosen for its potential to preserve the complexity of human behavior and to allow for a detailed exploration of the issue. Importantly, qualitative approaches allow for an exploration into the lived experience of depression among emerging adults that alternative approaches are unable to address.

Methods

Study Design

Physicians, social science researchers, and psychologists developed the interview guide through an iterative process based on a review of the current literature. Initially developed by two of the authors, the interview guide was then circulated to a range of professionals including a social science researcher, a clinical psychologist, and a college counseling center director. A final guide was agreed on by all authors. Five main topics were explored: (1) how individuals define and make sense of depression, (2) how individuals cope with and manage feelings of depression, (3) how individuals come to identify depression and their thoughts on the stigma associated with depression, (4) how individual beliefs and attitudes relate to treatment options and treatment seeking behaviors, and (5) how individuals view the developmental and social context within which they experienced the depressive disorder.

Questions focused on examining the dimensions of personal experience with depressive symptoms, such as how depression has affected one's life, how others react to the diagnosis, and thoughts about treatment. Although the goal was to obtain information on each of these topics, participants dictated the time given to each topic and were free to expand their answers and explore related areas. An initial version of the interview was piloted with two participants and refined for maximum clarity and depth. Each interview was conducted by one of the authors (SK), lasted approximately 75 minutes, and was audio taped and then transcribed verbatim.

Study Sample

We recruited participants from a large city in the Midwestern United States using advertisements posted in newspapers, other local print media, the Internet, and on university campuses. These postings asked for volunteers for a study of individuals “who had either been diagnosed with, sought treatment for, or who felt they had experienced feelings of depression.” In an effort to capture a range of potentially relevant perspectives, the language in the advertisement was purposely written to be as broad and all-inclusive as possible. Sample size was determined based on the saturation criterion proposed in grounded theory [28]. Saturation, meaning that no additional data are being found, was reached by the time 12 interviews had been conducted, at which point no additional information about emerging themes was derived from the interviews. All subjects provided written informed consent to participate, as approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Inclusion criteria were that the participant be between the ages of 18-25 and were currently experiencing either major or minor depression. We excluded individuals with suicidal intent or severe depression because of concern that the interview process might have an adverse effect on their illness. Physician interviewers determined inclusion criteria based the presence of at least one core symptom of depression (depressed mood, anhedonia, or irritability) that lasted for at least two weeks (determined using questions from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Outpatient Version (SCID)) [1]. Severity of depressed mood was determined by administering the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) [29]. Those with CES-D scores > 40 (one standard deviation above the mean for samples of individuals with major depression) were categorized as having severe major depression and were excluded. The Beck Depression Inventory-Second Version II (BDI-II) suicide question was used to screen for suicidality [30].

Analysis

A method of thematic analysis, which draws on principles of grounded theory, was used to identify themes in individuals' accounts of their experiences of depression [28]. Several methods were used to enhance the rigor of our analyses, including extensive probing of informants, a method of constant comparison, accrual of subjects beyond theme saturation, and the principle of reflexivity to understand our frame of reference and preconceptions [28, 31-32]. The latter was vital to our research as it decreased the likelihood of biased questions, analyses, or interpretations of the results. In addition, a team of investigators were involved in the analysis of the raw data, thereby decreasing the likelihood that possible disciplinary biases from a single researcher would excessively influence the results. The team of investigators involved in the analysis of the raw data included a social science master's student (SK), a physician-scientist trained in medicine and pediatrics who specializes in research on adolescent depression (BVV), a general internist and health services researcher who researches the doctor-patient relationship (GCA), and a clinical psychologist with expertise in stress and depression in youth depression.(JG).

A constant comparison of responses was used to organize major themes that emerged from the interviews. Specifically, data were collected, coded, and analyzed simultaneously for common themes and patterns of meaning. After two to three interviews had been completed and transcribed, the investigative team met as a group to discuss the data. During this first phase, investigators highlighted emergent themes and particularly noteworthy quotes. These group discussions in turn gave direction to future data collection. A list of themes was developed and expanded for subsequent interviews until further observations yielded minimal to no new information. It was then that the investigative team agreed that saturation had been reached. Eighty-two discrete categories of responses were initially identified. During the second phase, grounded theory was used to combine these categories and revise them to incorporate new themes. These themes were then grouped into categories and subcategories according to common properties. The third phase involved further integration and development of categories through comparison across interviews until a broad conceptual framework of themes was established. The main topics covered by the interview guide served as a starting point for organizing the data. This framework was then elaborated and modified as new themes and sub-themes emerged. These themes as well as sub-themes and illustrative quotes are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Themes, Sub-Themes and Exemplifying Quotes.

| THEME | SUB-THEMES | EXEMPLIFYING QUOTES |

|---|---|---|

| Identity | Interruption to identity | “Its kept me from growing as a person” |

| “It's a time when you don't feel like yourself” | ||

| “I think of it as certainly connected intimately to my being”-+ | ||

| “I do think it was important in sort of shaping how I respond to things today” | ||

| Cultural cues and biological models | “Personally I think its chemical, like in the brain” | |

| “It's your balance of chemicals trying to be balanced out” | ||

| “It seems to undercut the possibility that there are much more complicating factors as to why one is feeling depressed than just drugs can solve” | ||

| Ambiguity over medical definitions | “For some reason I am resistant to calling it an illness but I don't really know why” | |

| “Its talked about so much, its bounced around so much and yet nobody can really break it down and say what it is” | ||

| Sadness versus depression | “That's what I grapple with still…I just feel like everyone I know in my life is going through something all the time so I guess that's why its weird, then are we all depressed?” | |

| Healthcare | Access to care | “Insurance is kind of limited” |

| “The rising cost of insurance is a major barrier to treatment” | ||

| Stigma | “You always feel like you're getting judged when you're filling prescriptions” | |

| “It's shameful because you feel like you should be able to pull yourself together.” | ||

| “You're announcing both to yourself and to someone else that you need help, that you are no longer capable of doing something yourself and that can be really scary” | ||

| Lack of effective treatments | “And pills I don't know…it's weird just some of the stuff going into your body, not knowing” | |

| Uncertainty and fear | “it was just uncertainty about what the medication would do and how it would make me feel.” | |

| “I would trust someone to operate on my heart more so than I would trust someone to treat me for depression” | ||

| Relationships | Concern with meeting parents' expectations | “I was really worried about letting my parents down” |

| “I want to show my mom that I can take care of myself” … “The last thing I want to do is disappoint [my mom] and I didn't want her thinking that she had a crazy daughter, that wouldn't have been fair ‘cause she did a perfectly fine job of raising me; it wasn't her fault” | ||

| “By saying that I actually wasn't fine I was letting her, and this idea of me down” (#001) | ||

| Inability to be understood | “Unless you've actually been through a depression no one can really know how you feel” | |

| “It feels like no one would ever possibly understand how awful it is that you feel” | ||

| Social withdrawal or isolation | “I worry I don't want to be the downer friend” | |

| “I would much rather just be missing than be a basket case publicly” | ||

| Exhaustion of performing normalcy | “Secretly you look like you have it all together but inside you're a house of cards” | |

| “Everyday was like a theatre for me” | ||

| Role Transition | Overwhelmed by expectations | “Its just like all there and its so overwhelming, that's a huge part of it you're just completely overwhelmed” |

| “Being 22 you want to help the world, maybe save it on a good day but the issues that you have are overwhelming enough” | ||

| Concern about future | “I'm always worrying where my rent money is gonna' come from, I'd like to get a job, I'd like to get married, I worry about finding things to do and making friends” | |

| “its like you're falling out of the framework of what you wanted for your life and when you realize you can't have the exact life that you planned, that's such a major thing” | ||

| Feeling time lost or wasted | “Having dealt with depression makes me feel like I missed out on things” | |

| “I'm kind of a step behind because now I've got all this stuff to work on.” | ||

| “One minute everything is going fine and then you start to slip a little bit but you're so used to everything being fine you're like oh, I'm slipping a little bit but I'll find my ground, its okay. But you don't. And you slip and fall and you can't get up. You're just there and everybody who had been walking with you just left and you're alone” | ||

| Searching for contentment | “I'm really young, well I'm 24, I feel I'm really young, I know I want to go to law school but I don't’ know if that's what really grabs me” | |

| Feeling in-between | “No I don't feel like an adult. I'm still very scared, I'm not self-assured about the future.” | |

| “I'm more like a mini adult” | ||

| “This age is weird. Kind of free yet not” | ||

| Optimism | “I feel like I actually have a future as soon as I can shake this depression off” | |

| “Right now I'm in this kind of in-between spot I try not to let that get me down too much because you know I'm not going to be at this job the rest of my life” | ||

Results

Sample

Our final subject population consisted of 10 women and 5 men ranging in age from 18-25 years (mean age 23 years) and reflecting a range of depression severity. CES-D scores ranged from 13 (mild) to 39 (severe). The average CES-D score among participants was 24 (9.29 SD), reflecting a moderately to severely depressed sample. Of the 15 participants, two reported suicidal ideation, while 13 reported having no suicidal thoughts or wishes. In addition, subjects represented a range of ethnicities, socioeconomic backgrounds and social functioning. Seven of the participants were Caucasian, four were African American, and three were Asian. Although the sample ranged in age from 18-25, participants tended to be older and well educated. Four participants indicated that they had some college (2 reported having dropped out due to illness and 2 were currently in school at the time of the interview); five participants indicated they had a college degree; two reported having a graduate level degree and two did not mention their educational status. Participants' family histories were varied. Four of the participants grew up in a single parent home, eight grew up in a two-parent home and the other three did not mention their parents' marital status. In addition, three reported parent or family history of mental illness and three reported parent or family history of substance abuse.

Themes Identified

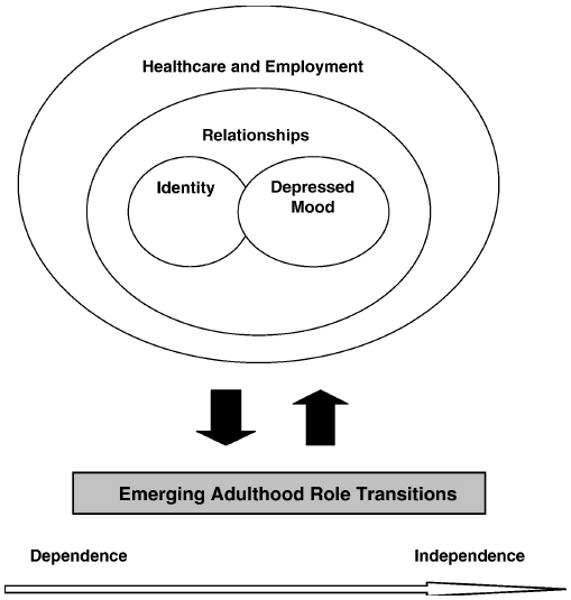

The themes identified in our analysis captured both the individual's experience and their reflected efforts to reconcile symptoms of depression with their previous identities, as well as the themes of navigating treatment, ascertaining their relationships with others, and adjusting to the role transitions inherent in the development from adolescence to adulthood (Table 1). Figure 1 describes a hypothesized relationship between these themes. In Figure 1, depressed mood, identity concerns, adverse relationship interactions and problematic transactions with the health care system adversely impact acquisition of developmental milestones. Similarly, impairment of developmental progress through young adulthood exacerbates concerns about identity and worsens depressed mood.

Fig. 1.

Interrelationships between themes.

Identification as an individual with depression

With regard to identity, sub-themes included “interruption of identity,” “cultural cues and biological models,” “ambiguity over medical definitions,” and “sadness versus depression.” For many individuals, depressive disorders seemed to both interrupt the development of a sense of identity as a young adult (by making them feel “other than themselves”), and simultaneously became a part of their identities that they mourned or felt they had learned from. While most accepted a biomedical model to explain their depressive disorder, others were concerned that this approach limited alternative frameworks (e.g. psychosocial) that might be helpful to redress their current situation. For example, as one individual said, “It's your balance of chemicals trying to be balanced out” (#002). However, when asked whether she considered depression to be a medical illness another participant said, “… it seems to undercut the possibility that there are much more complicating factors as to why one is feeling depressed than just drugs can solve” (#009). Lack of clarity about the medical definition of the disorder and the boundary between ordinary sadness and depression seemed to make several participants reluctant to fully embrace the perception that they had a disorder which might require clinical treatment. Though few participants mentioned religious experience or coursework in high school or college as an important part of how they understood their experiences with depression, several specifically mentioned advertisements as affecting how they thought about their experiences with depression. Participants did not clearly separate between self-assessment of a possible depressive disorder, their own process of identity development, cultural cues and models, and ideas about what constitutes a reasonable level of ordinary sadness. For example, one participant summarized, “It could be just sadness or it could just be an amalgamation of other sorts of emotions and this is sort of the current cultural construct that we've created to place on top of those feelings. I don't know if depression exists or not really, I just know that I feel really sad” (#007).

Healthcare experiences related to diagnosis and treatment

Several healthcare concerns emerged as topics of concern to study participants, including concerns about access to care (e.g. costs of insurance), a lack of effective treatments, and the stigma of mental illness. Lack of ability to either maintain employment or good standing as student because of depression symptoms often resulted in loss of health insurance. Individuals also lacked families willing and capable of supporting them with either insurance coverage (parent plan) or direct financial assistance for treatment found obtaining mental heath services particularly challenging. Other problems encountered included: long waiting periods, difficulties working with providers, and even problems with transportation. Stigma was both perceived by the depressed individual (“shame”) and from others, in terms of being judged by authority figures and announcing a sense of failure to friends and family. Many participants remained concerned that treatments were not effective or that they could not trust health care providers to care for such critical personal problems. Those who finally turned to community mental health centers or charitable agencies often found waiting lists, transportation challenges, and administrative complexities. Continued concerns about stigma tended to override the motivation and energy need for treatment-seeking endeavors.

Relationships and social support

A central concern seen in the data involved subjects' relationships and methods of social support. Sub-themes included “concerns about meeting parents expectations,” “inability to be understood,” “social withdrawal and isolation,” and “exhaustion of performing normalcy.” Most participants expressed some level of desire not to disappoint their parents with the “failure” of depressive disorders. Several individuals reported that their families were unable to assist or support them because of some combination of conflicts, poverty, or divorce, while others noted the importance of supportive, economically secure parents in facilitating their recovery. Despite the fact that all the individuals in this sample acknowledged social support as an important part of their daily lives, the belief that others cannot understand their experiences often caused individuals to feel alone. Many appeared to react to these concerns by withdrawing or feeling a sense of exhaustion at having to behave as though nothing was wrong. One participant explained, “You just feel so self defeated. It's like you have run a marathon and someone tells you, you have to run another one an you're just like, hands up, like I really can't do this like just physically you can't or mentally or emotionally, you're just drained” (#002). Consequently, many individuals reported that they lacked a peer support system sufficient to provide meaningful assistance.

Role transitions from adolescence into adulthood and general functioning

When asked about the transition from adolescence into adulthood, the emerging adults in our sample spoke of their search for a sense of personal contentment in love, work, and life. Sub-themes included “being overwhelmed with expectations,” “concern about the future,” “feeling time is lost or wasted,” “searching for contentment,” “feeling in-between,” and “optimism.” Many felt their depressive disorder and social circumstances left them barely able to cope with the present and left them overwhelmed in the face of the expectations of emerging adulthood or gaining traction in the quest for a more fruitful future. Several individuals reported a related concern that so much of their time had been “wasted,” leaving them far behind their peers in terms of major life milestones. Other participants reported as much interest in finding current contentment as future direction. Many expressed a feeling of being neither a full adult nor an adolescent. However, many remained optimistic about the future. Individuals in our sample reported on how the clash between current depressed mood, past “failures,” and future expectations could coalesce into profound discouragement, with an adverse impact on their abilities pursue the very goals they sought. One individual described it as, “The collision between anticipation, disappointment and just kind of, if nothing else the seeming unveil lance of the fact that the rest of your life dot, dot, dot, is actually really ambiguous” (#009). Another said, “its like you're falling out of the framework of what you wanted for your life and when you realize you can't have the exact life that you planned, that's such a major thing” (#005).

Discussion

In this qualitative study of emerging adults with depression, we identified four major themes: (1) identification of self as experiencing depression, (2) health care and health care seeking, (3) relationships and related impairment, and (4) role transitions in emerging adulthood. Just as with prior qualitative studies among depressed adults [33, 34], our use of qualitative methods with emerging adults allowed for valuable insights into participants' views, including the unique burdens and challenges posed by depression during this developmental period. As our results demonstrate, these challenges are exacerbated by the developmental tasks of emerging adulthood, such as identity formation, increased mobility, the instability of exploring numerous possibilities in love and work, and the frustration of failing to meet the expectations of oneself and others. Characterized by fluctuation, discontinuity, and uncertainty, this period of life marks a major transition of considerable change and significance in and of itself [18]. This study revealed further complex interactions between depressive disorders, developmental processes, and social context. These complex interactions may coalesce to exacerbate depressive symptoms or precipitate episodes.

Labeling one's experience and identity formation

The process of identifying and labeling one's experience with depression was found to be a complex process affecting both the experience of distress and treatment seeking [35, 36]. Previous research has demonstrated that emerging adults incorporate negative attitudes toward depression treatment into their self-assessment of their need for treatment [36, 37]. The degree to which “depression” represented a “negative” identity for emerging adults was surprising in light of rising rates of treatment for depression as well as higher levels of mental health literacy in more recent birth cohorts [21, 23, 38, 39]. The deep ambivalence regarding identification as a person with a depressive disorder and the disruption of normal developmental milestones both were important findings.

The critical role of identity formation in emerging adulthood may explain why “identity” concerns with regard to depression were so important to these emerging adults. Depressive experiences may be highly contextualized within the prominent issues during each life stage. Adolescent girls with depression have been noted to be predominantly preoccupied with a sense of disconnection from others [34]. Women and men in middle years report themes focused on present time coping, restoration of health, resumption of current roles, and finding meaning [40, 41]. Elderly women report depressive experiences merged with past events to create “unbearable summation” of the whole life experience [42]. Previous qualitative research has suggested that an individual's decision that a problem, warranting a formal remedy, exists represents a fundamental transformation in perception and identity [43].

Life stage: role transitions

Depressive symptoms demonstrate a complex interaction with the emerging adult's developmental process regarding role transitions. As noted, depressive disorders in adolescence and emerging adulthood are associated with less favorable relationship, educational, and work outcomes and may also be associated with other adverse events [2, 5-12]. However, these correlations have left open the question of whether the poor outcomes are caused by actual depressive symptoms or rather a factor common to both depressive illness and functional impairment. Emerging adults in this study consistently identified current depressive symptoms as important impediments to achieving valued life goals closely related to past and present disappointments. Moreover, an unfortunate cycle existed for many subjects whereby depressed mood included depressive symptoms leading to relational and work-related disappointments, which were then amplified in meaning as they were thought to connote “failure” in the adult life process.

Social context

The study revealed complex interactions between emerging adults, depressive disorders, and social context including social support, health insurance, employment, and actual health care services. Separate literatures have documented the adverse impact of depressive symptoms on relationships and substantial barriers posed to those attempting to obtain mental health services in an increasing fragmented and under-funded mental health care system in the United States [1, 2, 15, 44, 45]. The emerging adults described a pernicious coalescing of depressed mood, alienation and/or estrangement from family, loss of university- or employment-based insurance, and withdrawal or loss/attenuation of peer support networks. In contrast to children and older adults, many of the emerging adults in this study at times found few social supports – family, peer, employer- and/or state-related – to facilitate access to mental health specialty services. Cooper and colleagues have previously reported concerns about provider “trust” in a focus group conducted in 1997 [46]. Emerging adults in this study seem to express an even deeper level of distrust or reservation ranging from validity of disease models to competence of individual providers.

Complex interactions

This adverse relationship between depressive disorder, life stage, and social context may help explain the very low levels of treatment-seeking and high-quality treatment found in emerging adults with depressive disorders as well as developmental impairments as described in Figure 1 [2, 26, 27]. Employment, higher levels of social support and marriage have been shown to be associated with improved outcome for emerging adults with depressive disorders [47]. Onset and maintenance of depressive disorders in youth may result in a failure to develop one of several interlocking competencies the emerging adult must employ to successful navigate treatment, relationships, and role transitions [17, 48].

We succeeded in recruiting a diverse sample of emerging adults with regard to ethnicity, gender, socio-economic status, symptom severity, and functional impairment. In terms of internal validity, both the intimacy and intensity of the experiences shared in the interviews and that we achieved theme saturation suggests that we captured the breadth of experience available from this sample. Though researcher bias is a concern, we used reflexivity, triangulation of responses with multiple researchers, and continuation of subject recruitment until theme saturation was achieved to minimize bias. In terms of external validity, this was a small, but diverse sample in terms of education, income, and ethnicity. We cannot exclude the possibility that the participants in this study represented a particularly disgruntled or unsuccessfully-treated, unrepresentative subgroup, and we did not collect detailed data regarding participants' medical history that would allow for us to examine the associations between specific types of levels of comorbid illness and outcomes of interest. While the level of impairment was substantial in several of the participants, others reported success in gaining remission and improvements in work and relationship function.

Conclusion

For many emerging adults, depressive disorders are characterized by fluctuation, discontinuity, and uncertainty in mood, identity, developmental processes, and social relationships. The findings of this study highlight that there are numerous incumbent challenges for those whose depression emerges during adolescence and emerging adulthood. For researchers, this exploratory study suggests that further work is needed on the interactions between depressive symptoms, health care system factors, and developmental pathways to understand the full impact of depressive disorders during this important developmental period. For clinicians working with emerging adults experiencing depressive disorders, our findings reinforce the need to consider how emerging adults comprehend their illnesses in order to help them recover functional status and avoid delayed developmental milestones. For policy-makers, our findings suggest that the lack of motivation that accompanies depressive disorders and the limited access to and fragmentation of mental health care may significantly limit the ability of these emerging adults to obtain consistent, high-quality care. Preventive and treatment interventions may be adapted to address the specific needs to today's emerging adults with depression.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Dr. Alexander is a Robert Wood Johnson Faculty Scholar and is also supported by a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1 K08 HS15699-01A1). Dr. Van Voorhees is supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Depression in Primary Care Value Grant and a career development award from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH K-08 MH 072918-01A2)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.First Michael B, G M, Spitzer Robert L, Williams Janet B W, Benjamin Lorna. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Personality Disorders (SCID-I) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7(1):3–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<3::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klerman GL, Weissman MM. Increasing rates of depression. JAMA. 1989 Apr 21;261(15):2229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klerman GL. The current age of youthful melancholia. Evidence for increase in depression among adolescents and young adults. Br J Psychiatry. 1988 Jan;152:4–14. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binder J, Angst J. Social consequences of psychic disturbances in the population: a field study on young adults (author's transl) Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr. 1981;229(4):355–70. doi: 10.1007/BF01833163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breslau N, Kilbey M, Andreski P. Nicotine dependence, major depression, and anxiety in young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991 Dec;48(12):1069–74. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. DSM-III-R nicotine dependence in young adults: prevalence, correlates and associated psychiatric disorders. Addiction. 1994 Jun;89(6):743–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christie KA, Burke JD, Regier DA, et al. Epidemiologic evidence for early onset of mental disorders and higher risk of drug abuse in young adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(8):971–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.8.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst C, Foldenyi M, Angst J. The Zurich Study: XXI. Sexual dysfunctions and disturbances in young adults. Data of a longitudinal epidemiological study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;243(34):179–88. doi: 10.1007/BF02190725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horwitz AV, White HR. Becoming married, depression, and alcohol problems among young adults. J Health Soc Behav. 1991;32(3):221–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Runeson B. Mental disorder in youth suicide. DSM-III-R Axes I and II. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989 May;79(5):490–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb10292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skodol AE, Schwartz S, Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE. Minor depression in a cohort of young adults in Israel. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994 Jul;51(7):542–51. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070034008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hallowell EM, Bemporad J, Ratey JJ. Depression in the transition to adult life. Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989:175–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Ries Merikangas K. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: an epidemiologic perspective. Biol Psychiatry. 2001 Jun 15;49(12):1002–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Hauf AMC, Wasserman MS, Silverman AB. Major depression in the transition to adulthood: risks and impairments. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108(3):500–10. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berry D. The relationship between depression and emerging adulthood: theory generation. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2004 Jan-Mar;27(1):53–69. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The development of depression in children and adolescents. Am Psychol. 1998 Feb;53(2):221–41. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagestad GO, Neugarten BL. Age and the life course. In: Bienstock R, Shamus E, editors. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown JD, Cantor J. An agenda for research on youth and the media. J Adolesc Health. 2000 Aug;27(2 Suppl):2–7. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freudenheim M. Psychiatric drugs are now promoted directly to patients. NY Times (Print) 1998 Feb 17;:D1–D3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montgomery K. Youth and digital media: a policy research agenda. J Adolesc Health. 2000 Aug;27(2 Suppl):61–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veroff J, Kulka RA, Douvan E. Mental health in America: patterns of help-seeking from 1957 to 1976. New York: Basic Books; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berth H, Forster P, Brahler E. Unemployment, job insecurity and their consequences for health in a sample of young adults. Gesundheitswesen. 2003 Oct;65(10):555–60. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-43026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins SR, Schoen C, Kriss JL, Doty MM, Mahato B. Rite of passage? Why young adults become uninsured and how new policies can help. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2006 May;20:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Druss BG, Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA. Underuse of antidepressants in major depression: prevalence and correlates in a national sample of young adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000 Mar;61(3):234–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001 Jan;58(1):55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users' guide to the medical literature. XXIII. Qualitative research in health care: Are the results of the study valid? JAMA. 2000;284(3):357–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper LA, Brown C, Vu HT, et al. Primary care patients' opinions regarding the importance of various aspects of care for depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000 May-Jun;22(3):163–73. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hetherington JA, Stoppard JM. The theme of disconnection in adolescent girls' understanding of depression. J Adolesc. 2002 Dec;25(6):619–29. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Philby M. Making sense of the struggle. Recovering from depression. J Christ Nurs. 1991 Spring;8(2):4–8. doi: 10.1097/00005217-199108020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Houston TK, et al. Attitudes and illness factors associated with low perceived need for depression treatment among young adults. Soc Psychiatry and Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006 Sep;41(9):746–54. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Houston TK, Cooper LA, Wang NY, Ford DE. Beliefs and attitudes associated with the intention to not accept the diagnosis of depression among young adults. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(1):38–46. doi: 10.1370/afm.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barbui C, Percudani M. Epidemiological impact of antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs on the general population. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006 Jul;19(4):405–10. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000228762.40979.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jorm AF. Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000 Nov;177:396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skarsater I, Dencker K, Bergbom I, Haggstrom L, Fridlund B. Women's conceptions of coping with major depression in daily life: a qualitative, salutogenic approach. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2003 Jun;24(4):419–39. doi: 10.1080/01612840305313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skarsater I, Dencker K, Haggstrom L, Fridlund B. A salutogenetic perspective on how men cope with major depression in daily life, with the help of professional and lay support. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003 Feb;40(2):153–62. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedelin B, Strandmark M. The meaning of depression from the life-world perspective of elderly women. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2001 Jun;22(4):401–20. doi: 10.1080/01612840151136939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karp D. Speaking of sadness. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geraty R, Bartlett J, Hill E, Lee F, Shusterman A, Waxman A. The impact of managed behavorial healthcare on the costs of psychiatric and chemical dependency treatment. Behav Healthc Tomorrow. 1994 Mar-Apr;3(2):18–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stroul BA, Pires SA, Armstrong MI, Meyers JC. The impact of managed care on mental health services for children and their families. Future Child. 1998 Summer–Fall;8(2):119–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, et al. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1997 Jul;12(7):431–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galambos NL, Barker ET, Krahn HJ. Depression, self-esteem, and anger in emerging adulthood: seven-year trajectories. Dev Psychol. 2006 Mar;42(2):350–65. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cicchetti D, Toth S. An organizational approach to childhood depression. In: Rutter M, Izzard CE, Read PB, editors. Depression in Young People: Developmental and Clinical Perspectives. New York: Guilford Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]