Abstract

Objective To examine trends in long term survival in patients alive 28 days after myocardial infarction and the impact of evidence based medical treatments and coronary revascularisation during or near the event.

Design Population based cohort with 12 year follow-up.

Setting Perth, Australia.

Participants 4451 consecutive patients with a definite acute myocardial infarction according to the World Health Organization MONICA (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease) criteria admitted to hospital during 1984-7, 1988-90, and 1991-3.

Main outcome measures All cause mortality identified from official mortality records and the hospital morbidity data, with death from cardiovascular disease as a secondary end point.

Results In the 1991-3 cohort, 28 day survivors of acute myocardial infarction had a 7.6% absolute event reduction (95% confidence interval 4% to 11%) or a 28% lower relative risk reduction (16% to 38%), unadjusted for risk of death, over 12 years after the incident admission compared with the 1984-7 cohort, similar to the survival of the 1988-90 cohort. The improved survival for the 1991-3 cohort persisted after adjustment for demographic factors, coronary risk factors, severity of disease, and event complications with an adjusted relative risk reduction of 26% (14% to 37%), but this was not apparent after further adjustment for medical treatments in hospital and coronary revascularisation procedures within 12 months of the incident myocardial infarction.

Conclusion The improving trends in 12 year survival after a definite acute myocardial infarction are associated with progressive use of evidence based treatments during the initial admission to hospital and in the 12 months after the event. These changes in the management of acute myocardial infarction are probably contributing to the continuing decline in mortality from coronary heart disease in Australia.

Introduction

The continuing long term decline in mortality from coronary heart disease in Australia and elsewhere has been widely attributed to both declining incidence and advances in medical treatment.1 2 Previous studies in Perth, including the World Health Organization MONICA project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease), have shown rapid and progressive uptake in aspects of medical care shown in randomised clinical trials to reduce both acute and medium term mortality after acute myocardial infarction.3 4 5 Such treatment included antiplatelet therapy, thrombolysis, β blockers, lipid lowering drugs, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, and coronary artery revascularisation (percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass graft).6 7 8 9 10 There are, however, few studies documenting the long term impact at the population level on survival after acute myocardial infarction or on death rates from coronary heart disease. Such data could be used to support policies promoting the systematic application of evidence based medicine in coronary heart disease such as the national service framework benchmark of “improving the use of effective medicines after heart attack (especially use of aspirin, beta-blockers and statins) so that 80-90% of people discharged from hospital following a heart attack will be prescribed these drugs.”11

We examined trends in long term survival in people registered as having an acute myocardial infarction over a 10 year period in Australia.

Methods

Study population

The study population comprised all residents of the Perth Statistical Division (population size 1.19 million in 1991) aged 35-64 who were admitted to hospital with a first non-fatal definite acute myocardial infarction and registered by the Perth MONICA project during 1984-93.12 Full details of the project are described elsewhere.3 Briefly, acute myocardial infarction was diagnosed with MONICA criteria based on symptoms, cardiac enzyme activity, and Minnesota coding of serial electrocardiograms. Only individuals who survived 28 days after an incident acute myocardial infarction were included. Incident events were defined as the absence of a previous acute myocardial infarction recorded in the hospital record of the index event and the absence of an admission to hospital for ischaemic heart disease (ICD-9 (international classification of diseases, ninth revision) codes 410-414 and related conditions such as cardiac dysrhythmias and heart failure, codes 427-429) in the previous four years (the Western Australian data linkage system includes all admissions to hospitals in Western Australia since 1980). We have previously shown that a negligible proportion of patients with recognised acute myocardial infarction in Perth are managed solely at home.13

Data sources and record linkage

We linked the records of all people included in the Perth MONICA register to a file of all hospital admissions for cardiovascular disease and related deaths in Western Australia from 1980-2005 using standard linkage procedures developed by the data linkage unit in the Department of Health of Western Australia. From this we selected the subset of records for the cases described above together with records of all hospital admissions for cardiovascular disease since 1980 or death records (from any cause) to the end of 2005. From this we identified “incident” cases (no admissions for ischaemic heart disease in the four years before the index admission); cases in which the patient underwent coronary artery revascularisation procedure within one year of the index event; and all deaths (including date and coded cause of death) in the study cohort up to the end of 2005, representing a minimum follow-up period of 12 years. Cases of acute myocardial infarction, coronary artery revascularisation, and cardiovascular death were identified and coded according to the ICD-9 for 1984-7, ICD-9 clinical modification from 1988 to 30 June 1999 (with the Australian version being used from 1 July 1995 to 30 June 1999), and ICD-10 (Australian modified) for 1 July 1999 to 2005. These included acute myocardial infarction (ICD-9 code 410 or ICD-10 code I21, I22); percutaneous coronary intervention (codes 5-363, 36.01, 36.02, 36.05, or blocks 670, 35304-00, 35305-00), percutaneous coronary intervention with stents (codes 36.06, 36.07, or blocks 35310-00, 35310-01, 35310-02), coronary artery bypass graft (codes 5-361, 36.10-36.19, or blocks 672-679), or cardiovascular death (codes 390-459 or I00-199). Several previous studies have confirmed the validity of the Western Australian data linkage system,14 15 16 including the official mortality records for Western Australia.17

Follow-up and end points

Our principal end point was all cause mortality identified from the death registry and the hospital morbidity data collection, with death from cardiovascular disease as a secondary end point. In addition we examined the incidence of coronary artery revascularisation within a year of an index event as a covariate relating to survival after one year.

Possible factors influencing long survival after acute myocardial infarction

To assess the relation between calendar period and survival after infarct we divided the cohort into three subcohorts (1984-7, 1988-90, and 1991-3) that allowed sufficient numbers in each group for comparison. Other factors selected for analysis included age and sex, smoking status (within the 12 months before the admission), medical history as recorded in hospital records (diabetes, history of hypertension), and measures of disease severity. These included creatine kinase ratio (defined as the ratio of maximum creatine kinase value for the event to the relevant upper limit of normal for each hospital), abnormal ST segment deviation (≥0.5 mV elevation or depression, or both), electrocardiogram score with the predicting risk of death in cardiac disease tool (score 0-3 based on ischaemic electrocardiogram progression18), and event complications (heart failure, cardiogenic shock, tachycardia >100 beats/minute, systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg). Measures of treatment were identified from randomised control trials for their efficacy in managing acute myocardial infarction and from the final MONICA treatment score.1 These included selected drugs used during the acute event or prescribed at discharge or coronary artery revascularisation within 12 months.

Analysis of data

We examined differences in the distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics of those surviving 28 days after the incident acute myocardial infarction for the three subcohorts (1984-7, 1988-90, 1991-3) using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Where data for baseline variables were missing we imputed null values. We plotted Kaplan Meier curves of time to death for each of the three subcohorts and used the log rank test to determine if there were any statistical differences in survival. We used Cox regression to examine the hazard ratio for death over 12 months and 12 years, with a stepwise adjustment for possible factors influencing survival. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 15.0 and SAS version 9.1.

Results

Baseline characteristics

From 1984 to 1993, 5340 people aged 35-64 years who were living in the Perth statistical division were admitted to hospital with first ever definite acute myocardial infarction and survived at least 28 days. Some 889 (16%) were excluded for having been admitted to hospital with other manifestations of ischaemic heart disease within four years of the index event. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 4451 people, stratified according to the three subcohorts. There was no significant difference in the proportion of people in each 10 year age group for the three subcohorts, with a combined mean age of 54.4 (SD 7.3) years. Overall, 18% were women, 10% had a history of diabetes, 51% were current smokers, and 40% had a history of hypertension. The prevalence of diabetes increased with each successive subcohort, smoking decreased, and hypertension (treated and untreated) was unchanged. While the median creatine kinase ratio was unchanged over time, the prognostic markers of Q wave acute myocardial infarction and ST deviation successively fell with each subcohort. This was associated with complementary changes in the electrocardiogram score with the predicting risk of death in cardiac disease tool, with the most noticeable difference occurring in 1984-7 and between subsequent subcohorts. Likewise, the proportion with changes on anterior electrocardiogram increased after the first subcohort with a parallel reduction in the proportion of cases who had evidence of heart failure within 28 days of the acute myocardial infarction. Temporal changes in the remaining clinical characteristics were not significant. There were, however, significant changes in treatment with each successive subcohort: a marked increase in the use of β blockers, antiplatelets, and thrombolytic treatment during the acute episode, and significant uptake of antiplatelets, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, β blockers, and lipid lowering drugs at the time of discharge from hospital (table 1). As changes in drugs at discharge ran parallel to changes in drugs in hospital it is therefore not easy to distinguish between the effects of acute treatment or subsequent long term treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (percentages of patients unless specified) in 28 day survivors of an acute myocardial infarction (AMI): Perth MONICA cohort 1984-93

| Characteristics | 1984-7 (n=1745 ) | 1988-90 (n=1395 ) | 1991-3 (n=1311) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 54 (7) | 54 (7) | 54 (7) | |

| 35-44 | 11 (192) | 11 (160) | 13 (177) | 0.21 |

| 45-54 | 31 (537) | 32 (451) | 31 (412) | |

| 55-64 | 58 (1016) | 56 (784) | 55 (722) | |

| Male | 83 (1447) | 81 (1130) | 83 (1089) | 0.28 |

| Medical history: | ||||

| Diabetes | 8 (141) | 9 (132) | 11 (148) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 40 (700) | 40 (566) | 38 (503) | 0.49 |

| Smoker past 12 months | 55 (963) | 49 (686) | 49 (638) | <0.003 |

| AMI features: | ||||

| Q wave AMI | 56 (977) | 51 (717) | 47 (621) | <0.001 |

| Anterior AMI | 43 (750) | 47 (661) | 47 (623) | 0.03 |

| ≥0.5 mV ST deviation | 63 (1092) | 57 (792) | 56 (729) | <0.001 |

| Electrocardiogram PREDICT score*: | ||||

| 0 | 24 (426) | 33 (468) | 31 (414) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 68 (1189) | 61 (855) | 63 (824) | |

| 2 | 4 (70) | 3 (46) | 3 (45) | |

| 3 | 3 (60) | 2 (26) | 2 (28) | |

| Acute markers: | ||||

| Median of CK ratio† (IQR) | 7 (4-11) | 6 (3-12) | 6 (3-13) | 0.20 |

| Systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg | 4 (71) | 4 (58) | 5 (69) | 0.28 |

| Tachycardia >100 beats per min | 27 (475) | 27 (375) | 28 (367) | 0.60 |

| Length of stay >10 days | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.10 |

| Mean (SD) total days in hospital | 3.5 (2.0) | 2.6 (1.7) | 3.0 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure within 28 days of AMI | 30 (523) | 25 (353) | 25 (330) | 0.002 |

| Cardiogenic shock within 28 days of AMI | 3 (57) | 2 (33) | 3 (35) | 0.29 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention: | ||||

| 0-28 days after incident AMI | 0 (0) | 8 (114) | 11 (145) | <0.001 |

| 29-365 days | 1 (12) | 7 (93) | 9 (123) | |

| >1-12 years | 6 (113) | 7 (96) | 9 (119) | |

| Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery: | ||||

| ≤1 year after incident AMI | 1 (23) | 16 (219) | 17 (227) | <0.001 |

| >1-12 years | 17 (304) | 14 (201) | 12 (162) | |

| Any coronary revascularisation: | ||||

| ≤1 year after incident AMI | 2 (35) | 31 (426) | 38 (495) | 0.001 |

| >1-12 years | 24 (417) | 21 (297) | 21 (281) | |

| Medical treatment in hospital: | ||||

| Thrombolytic treatment | 12 (218) | 37 (519) | 49 (644) | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelets | 45 (785) | 91 (1271) | 97 (1273) | <0.001 |

| β blockers | 66 (1148) | 82 (1148) | 88 (1150) | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors | 9 (160) | 15 (211) | 29 (383) | <0.001 |

| Medical treatment at discharge: | ||||

| Antiplatelets | 32 (565) | 81 (1130) | 85 (1114) | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors | 5 (91) | 10 (146) | 26 (339) | <0.001 |

| β blockers | 55 (963) | 70 (978) | 77 (1015) | <0.001 |

| Lipid lowering drugs | 2 (30) | 3 (38) | 5 (71) | <0.001 |

Note: numbers might not add up exactly because of rounding. IQR=interquartile range; AMI=definite acute myocardial infarction (MONICA criteria)12; ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme; CK=creatine kinase.

* Predicting risk of death in cardiac disease tool score (score 0-3 based on ischaemic ECG progression).14

†Defined as ratio of maximum CK value for event to relevant upper limit of normal.

Trends in revascularisation

With each successive subcohort, more survivors of acute myocardial infarction underwent coronary artery revascularisation, particularly within 12 months. The proportion of revascularisation within 12 months was 2% in 1984-7, 31% in 1988-90, and 38% in 1991-3 (P<0.001 for trend). Surgical revascularisation in the 12 years of follow-up was highest in the 1984-7 subcohort, whereas percutaneous coronary intervention was highest during the first 12 months (and 28 days) in the 1991-3 subcohort. While the frequency of coronary artery bypass graft was more than twice that of percutaneous coronary intervention in the 1984-7 subcohort, by 1991-3 equal proportions of coronary artery bypass graft and percutaneous coronary intervention procedures (29% each) were performed. In 1984-7, 1988-90, and 1991-3 the proportions of each subcohort undergoing coronary artery revascularisation were 26%, 52%, and 59%, respectively.

Factors increasing risk of death

We used Cox regression models to compare the risk of death for three subcohorts over 12 months and 12 years with stepwise adjustment for possible factors influencing survival. Table 2 shows adjusted hazard ratios for death, adjusted for age, sex, and subcohort, associated with individual factors thought to influence survival in people alive a year after an incident acute myocardial infarction and followed up for 12 years. Having a history of diabetes or hypertension, being a current smoker, and having a higher electrocardiogram score with predicting risk of death in cardiac disease tool were all associated with a significantly increased risk of death. Survival was also lower in patients with evidence of heart failure or cardiogenic shock within 28 days of the acute myocardial infarction or tachycardia, whereas a systolic blood pressure of <100 mm Hg on presentation had no apparent effect on the risk of death. Similarly, interventions associated with a significantly lower risk of death over 12 years included at least two of the drug treatments in hospital (except possibly angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors), one or two of the drugs prescribed at discharge (except angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or lipid lowering treatment when used alone), and coronary revascularisation within 12 months of the incident acute myocardial infarction. Note, the low prescription rates of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and lipid lowering drugs at discharge were associated with an increased risk of death after 12 years, suggesting confounding by the indication for which the drugs were prescribed.

Table 2.

Adjusted* hazard ratios for death for individual factors at 12 years in one year survivors of acute myocardial infarction (AMI): Perth MONICA cohort 1984-93

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| History of diabetes | 2.49 (2.12 to 2.93) | <0.001 |

| History of hypertension | 1.40 (1.24 to 1.58) | <0.001 |

| Current or recent smoker | 1.31 (1.15 to 1.48) | <0.001 |

| ECG PREDICT score† | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 1.43 (1.23 to 1.67) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 2.71 (2.06 to 3.58) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 2.48 (1.78 to 3.44) | |

| Heart failure within 28 days of AMI | 1.93 (1.70 to 2.18) | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock within 28 days of AMI | 1.90 (1.42 to 2.55) | <0.001 |

| Tachycardia >100 beats/minute | 1.66 (1.46 to 1.89) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg | 1.08 (0.84 to 1.40) | 0.526 |

| In hospital medical treatment for AMI: | ||

| Thrombolysis | 0.74 (0.64 to 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelet | 0.77 (0.65 to 0.90) | <0.001 |

| β blocker | 0.55 (0.48 to 0.63) | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitor | 1.91 (1.64 to 2.22) | <0.001 |

| Composite treatment score‡: | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0.84 (0.68 to 1.04) | 0.118 |

| 2 | 0.70 (0.56 to 0.87) | 0.001 |

| 3 | 0.56 (0.44 to 0.72) | <0.001 |

| 4 | 0.69 (0.49 to 0.99) | 0.043 |

| Medical treatment on discharge after AMI: | ||

| β blockers | 0.56 (0.50 to 0.64) | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelets | 0.74 (0.64 to 0.85) | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors | 2.23 (1.89 to 2.62) | <0.001 |

| Lipid lowering | 1.40 (1.01 to 1.94) | 0.041 |

| Composite treatment score: | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0.69 (0.58 to 0.82) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.58 (0.48 to 0.69) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 0.84 (0.64 to 1.11) | 0.224 |

| 4 | 0.97 (0.36 to 2.62) | 0.950 |

| Coronary artery revascularisation within 12 months of AMI | 0.53 (0.44 to 0.64) | <0.001 |

ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme; AMI=definite acute myocardial infarction (MONICA criteria).12

*Adjusted for age, sex, and subcohort.

†Predicting risk of death in cardiac disease tool score (score 0-3 based on ischaemic ECG progression).14

‡Composite treatment score (score 0-4 based on number of drug treatments used in each patient as listed in table).

Trends in one year survival

In the 1991-3 subcohort, people surviving at least 28 days after an incident acute myocardial infarction had a lower unadjusted all cause mortality at one year compared with patients from the 1984-7 subcohort, with a relative risk reduction of 40% (95% confidence interval 10% to 60%) (table 3). The wide confidence interval is the result of a smaller number of deaths observed during one year follow-up. This survival benefit persisted after adjustment for demographic characteristics and coronary risk factors but was reduced to 34% (0% to 56%) after further adjustment for severity of disease and clinical complications, and to 0 (−65% to 39%) after further adjustment for medical treatment during admission to hospital. There was non-significant improvement in survival over one year between 1984-7 and 1988-90 subcohorts.

Table 3.

Hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for death in survivors of an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) after stepwise addition of risk markers: Perth MONICA cohort 1984-93

| 1988-90 v 1984-7 | 1991-3 v 1984-7 | |

|---|---|---|

| Death at one year in 28 day survivors | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.77 (0.53 to 1.11) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.90) |

| Adjusted for: | ||

| Demographic factors (age and sex) | 0.76 (0.53 to 1.11) | 0.61 (0.40 to 0.91) |

| Above plus coronary risk factors* | 0.76 (0.53 to 1.11) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.91) |

| Above plus disease severity† | 0.82 (0.56 to 1.19) | 0.64 (0.42 to 0.96) |

| Above plus clinical complications during admission‡ | 0.83 (0.57 to 1.20) | 0.66 (0.44 to 1.01) |

| Above plus medical treatment in hospital§ | 1.10 (0.72 to 1.69) | 1.00 (0.61 to 1.65) |

| Death at 12 years in one year survivors | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.88 (0.76 to 1.02) | 0.72 (0.62 to 0.84) |

| Adjusted for: | ||

| Demographic factors (age and sex) | 0.88 (0.76 to 1.01) | 0.72 (0.62 to 0.84) |

| Above plus coronary risk factors* | 0.88 (0.76 to 1.01) | 0.71 (0.61 to 0.82) |

| Above plus disease severity† | 0.93 (0.80 to 1.07) | 0.73 (0.63 to 0.85) |

| Above plus clinical complications during admission‡ | 0.94 (0.82 to 1.09) | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.86) |

| Above plus medical treatment in hospital§ | 1.19 (1.00 to 1.40) | 0.96 (0.79 to 1.16) |

| Above plus CAR within 12 months | 1.38 (1.16 to 1.63) | 1.15 (0.94 to 1.40) |

CAR=coronary artery revascularisation.

*History of diabetes, history of hypertension, and current or recent smoker.

†Predicting risk of death in cardiac disease tool score (score 0-3 based on ischaemic ECG progression).14

‡Heart failure, cardiogenic shock, tachycardia>100 beats/minute, systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg within 28 days of admission to hospital.

§Thrombolysis, antiplatelet, β blocker, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, and lipid lowering drugs.

Trends in 12 year survival

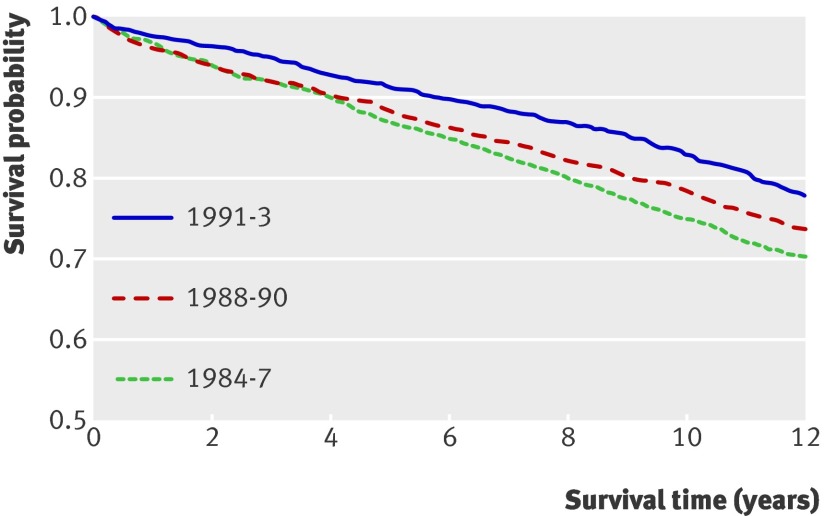

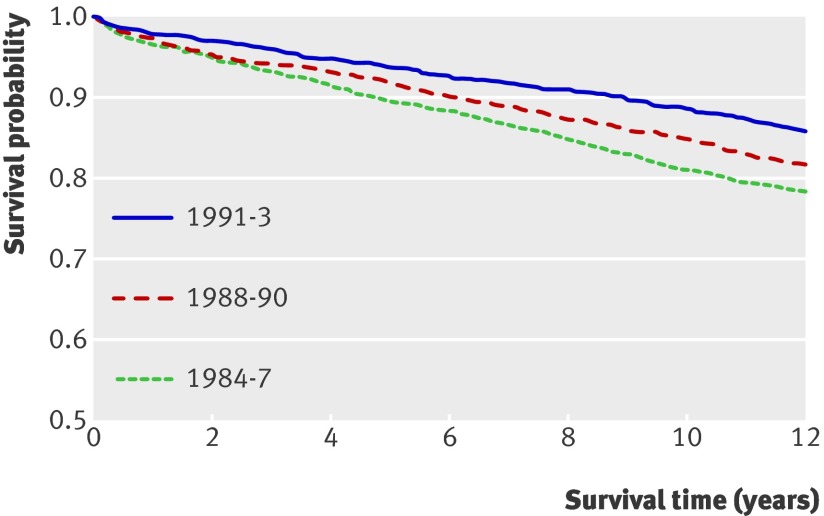

Figures 1 and 2 and table 4 show survival analyses for 12 year all cause and cardiovascular mortality, respectively. People in the 1991-3 subcohort alive at one year after the incident event experienced a lower unadjusted 12 year all cause mortality compared with patients in the 1984-7 subcohort, with a relative risk reduction of 28% (16% to 38%) (table 3), equivalent to an absolute event reduction of 7.6% (4% to 11%) (table 4). This difference in survival persisted after adjustment for demographic variables, coronary risk factors, severity of disease, and clinical complications, with a relative risk reduction of 26% (14% to 37%), but was no longer apparent after further adjustment for medical treatment during admission and coronary artery revascularisation within 12 months of the incident acute myocardial infarction. The improvement in survival over 12 years between the 1984-7 and 1988-90 subcohorts was borderline (P=0.055). The improvement in long term survival across the three subcohorts persisted when we separately analysed data for the 3554 men and after an analysis including 28 day survivors of acute myocardial infarction with a history of ischaemic heart disease (12 year cumulative survival of 67.9%, 69.9%, and 74.1% for successive subcohorts, respectively).

Fig 1 Kaplan-Meier all cause mortality in 28 day survivors of acute myocardial infarction: Perth MONICA cohort 1984-93

Fig 2 Kaplan-Meier cardiovascular mortality in 28 day survivors of acute myocardial infarction: Perth MONICA cohort 1984-93

Table 4.

Cumulative mortality (percentage and 95% confidence intervals) in 28 day survivors of acute myocardial infarction: Perth MONICA cohort 1984-93

| Aggregate year of diagnosis | No of patients | 1 year | 5 year | 10 years | 12 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative all cause mortality | |||||

| 1984-7 | 1745 | 4.2 (3.2 to 5.1) | 13.1 (11.5 to 14.7) | 25.1 (23.1 to 27.2) | 29.9 (27.7 to 32.1) |

| 1988-90 | 1395 | 3.2 (2.2 to 4.1) | 11.9 (10.2 to 13.6) | 21.6 (19.4 to 23.8) | 26.4 (24.1 to 28.8) |

| 1991-3 | 1311 | 2.5 (1.6 to 3.4) | 8.9 (7.3 to 10.5) | 17.1 (15.5 to 19.2) | 22.3 (20.0 to 24.6) |

| Cumulative cardiovascular mortality | |||||

| 1984-7 | 1745 | 3.4 (2.6 to 4.3) | 10.3 (8.8 to 11.7) | 18.4 (16.6 to 20.2) | 20.8 (18.9 to 22.8) |

| 1988-90 | 1395 | 2.6 (1.8 to 3.5) | 8.1 (6.6 to 9.5) | 14.5 (12.7 to 16.4) | 17.6 (15.6 to 19.5) |

| 1991-3 | 1311 | 2.0 (1.3 to 2.8) | 6.2 (4.9 to 7.6) | 11.1 (9.4 to 12.7) | 13.6 (11.8 to 15.5) |

Twelve year survival trends for cardiovascular death by subcohort were comparable with findings for all cause mortality (fig 2). The proportion of total deaths after 12 years caused by cardiovascular disease in first, second, and third subcohorts was 70%, 66%, and 61%, respectively.

Discussion

This population based study of the metropolitan area of Perth, Western Australia, shows improving trends in one and 12 year survival in those alive at least 28 days after a definite acute myocardial infarction. Previously, 28 day case fatality did not differ for the entire cohort.3 Improved survival in the early 1990s over the early 1980s corresponds with the introduction of new treatments rather than changes in risk factors before the infarction or severity of infarction. The improvement in the 1991-3 subcohort compared with the 1984-7 and 1988-90 subcohorts was significant. The differences in survival across the three subcohorts persisted after adjustment for age, sex, and coronary risk factors and were marginally different after further adjustment for severity of disease and event complications. Once we adjusted for medical treatment, however, the survival difference for the 1991-3 subcohort was even less apparent after one year, and adjustment for both medical treatment and coronary revascularisation within 12 months in those alive at one year resulted in the differences between subcohorts in survival to 12 years becoming non-significant.

Strengths and weaknesses of study

Our study documents changes in one and 12 year survival in a population based cohort of people admitted to hospital for acute myocardial infarction, with stringent diagnostic criteria, over a 10 year period during which medical and surgical treatment for coronary heart disease was changing rapidly in response to published results of large randomised controlled trial and meta-analyses. We applied unchanging criteria for definite acute myocardial infarction based on electrocardiography, cardiac biomarkers, and symptoms as defined in the MONICA project,12 which would overcome any diagnostic drift over time. Local research has shown that robust evidence from clinical trials for the treatment and management of acute myocardial infarction was adopted quickly in Perth.3 4 5 19 Near complete follow-up (estimated at 99%) was ensured through the well established procedures of the Western Australian data linkage system. Our analysis also reconfirmed the main predictors of survival after acute myocardial infarction, similar to previous studies20 21 but over a longer term.

The use of proved medical treatment, as exemplified by antiplatelets, thrombolysis, and β blockers during admission to hospital, and performance of coronary artery revascularisation within 12 months after an incident acute myocardial infarction accounted for the greatest improvement in survival over 12 years. In practical terms, proportionately 9% fewer cardiovascular deaths occurred over 12 years in the 1991-3 subcohort than in the 1984-7 subcohort.

This study also has some limitations. Severity of disease as measured by electrocardiography, peak creatine kinase activity, and haemodynamic indices did not account for differences in survival between the subcohorts. More sophisticated measures such as ejection fraction and indices of infarct size, as well as information on delay between onset of symptoms and arrival at hospital, which are not routinely available in hospital records, might indicate a contribution of altered severity to the change in longer term survival. These data were not available for analysis.

We ascertained the history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and smoking from the medical record using clinical diagnoses, which could be subject to reporting bias. Prospectively collected cross sectional data from population based samples of Australians, however, indicated trends in prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and smoking from 1980-99 that are consistent with our data.22

Although our findings involve a relatively younger population (age 35-64) they are consistent with findings from an unrestricted cohort of adults in Scotland.23 Also a recent study from Boston in elderly patients found similar long term survival benefit.24

Our study was observational and the results should be interpreted with caution. Observational studies that attempt to evaluate the efficacy of different treatment regimens might introduce treatment selection bias and competing recognition and management of comorbidity.25 26 This type of bias is of less concern in our study because we compared periods rather than treatment groups. Despite having adjusted for confounding when we had relevant data, if there was a bias involving, say, physician preference, that changed over the three periods, it would remain.

Relevance of our findings

Other studies have reported improvements in short and long term survival after acute myocardial infarction during similar historical periods.23 27 In a study of 117 718 patients admitted to hospital with a principal diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in Scotland between 1986 and 1995, the crude case fatality at one year fell from 35.3% to 27.8% and at five years from 52.3% in 1986 to 49.3% in 1991.23 The improvement in short term survival was attributed to thrombolysis, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, and aspirin, with the long term survival advantage linked to diet, smoking cessation, and continuing treatment with aspirin and β blockers.27 Similar conclusions were drawn from the population based Minnesota Heart Survey, which showed ongoing declines in three year case fatality after admission to hospital for acute myocardial infarction in men and women aged <75 discharged from greater Minneapolis and St Paul hospitals from 1985 to 199527 but not from 1980 to 1985.28 29 Furthermore, the Minnesota group concluded that coronary artery revascularisation was probably a significant contributor in improved survival.27 Goldberg et al showed a significant improvement in one year survival, adjusted for age, acute prognostic markers, and thrombolysis, among patients with acute myocardial infarction discharged from hospital during the early to mid-1990s compared with those discharged in the previous decade.30 Finally, a registry study of residents with acute myocardial infarction from Gerona, Spain, showed no significant differences in the three year mortality after discharge of 8.3% in 28 day survivors between periods 1978-85 and 1986-8,31 although the observational period in this study and the earlier reports from the Minnesota Heart Survey28 29 were before the widespread uptake of thrombolytic treatment, antiplatelets, and coronary artery revascularisation.

In addition to variables in patients, improvements in long term survival are probably attributable to a combination of various treatments rather than any single treatment. Over the study period there was an increasing use of relevant medical treatment and coronary artery revascularisation at the onset of acute myocardial infarction, all of which have been shown to reduce cardiac mortality and morbidity in Western Australia.3 4 5 19 While we have no record of ongoing cardioprotective treatment beyond that given at discharge, Czarn et al showed relatively high levels of compliance with such treatment in MONICA patients with acute myocardial infarction during 1984-8 and followed up for one to six years.5 Furthermore, almost half continued to see a specialist, while 65% saw a general practitioner.5

Subsidised statin treatment during MONICA enrolment was available to those with a qualifying serum cholesterol concentration ≥6.5 mmol/l, falling to 5.5 mmol/l in the 1990s. National data show that prescriptions for lipid lowering drugs and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors have increased nearly 20-fold from 1991 to 2004. This suggests that patients in the 1991-3 subcohort were probably exposed to greater use of such drugs than those in the earlier subcohorts, especially in the years of follow-up before 1993 when almost certainly much lower prescription rates existed.

Changes in lifestyle characteristics and dietary practices might also have contributed to trends in survival.22 32 We found a 3% increase in diabetes, and corresponding population data show a mean upward trend in body mass index of about an 0.8% annual rise in the prevalence of overweight.22 This is counterbalanced by more modest reductions in physical inactivity, mean total cholesterol concentration, and smoking in the same population.22 In our analysis we have controlled for hypertension and diabetes mellitus that are partly consequences of overweight and lifestyle. Data on body mass index, physical inactivity, and smoking, however, were not available and so cannot directly be adjusted for.

Changes in severity of disease could also improve long term survival after acute myocardial infarction, though we found no change in creatine kinase ratios associated with proportionally fewer ischaemic changes on electrocardiography and a lower incidence of heart failure from the 1984-7 to the 1991-3 subcohort. Adjustment for these markers of disease severity did not alter the one and 12 year survival differences seen between the 1991-3 and 1984-7 subcohorts. Furthermore, we used stringent and unchanged diagnostic criteria throughout the study period. MONICA data from the two Australian centres have previously reported little difference in 28 day case fatality.3 Our finding of unchanged severity of disease accords with haemodynamic, cardiac enzyme, and electrocardiographic findings in cases of validated acute myocardial infarction registered by the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study from 1987 to 1994.33 Continued community surveillance in Finland of adults experiencing an acute myocardial infarction from 1980 to 2000 has also shown a falling a prevalence of large Q waves and other ischaemic findings on electrocardiography.34

Conclusion

One and 12 year survival increased in patients aged 35-64 from Perth who were alive 28 days after an incident acute myocardial infarction from 1984 to 1993. The improvement is associated with changes in treatment during and within 12 months of the event, exemplified by antiplatelets, thrombolysis, β blockers, and coronary artery revascularisation. These changes are consistent with better treatment of acute myocardial infarction having an important impact on the continuing decline in mortality from coronary heart disease in Australia. The magnitude of the contribution of evidence based treatment to the decline in mortality from coronary heart disease remains unanswered as does the contribution of chronic cardioproctective pharmacotherapy.

What is already known on this topic

Medical care and control of coronary risk factors both contribute to the decline in mortality from coronary heart disease

Little is known about the impact of adopting robust evidence from clinical trials on long term survival after acute myocardial infarction

What this study adds

Patients with acute myocardial infarction who receive drug treatments of proved value during presentation to hospital and undergo coronary revascularisation within 12 months are more likely to survive over 12 years

Evidence based treatment of acute myocardial infarction is associated with improved long term survival and probably contributes to the continuing decline in mortality from coronary heart disease in Australia

We thank Steve Ridout for his programming skills in linking the large datasets used in this analysis.

Contributors: TB conceived the study and is guarantor. SH conceived the study, was senior analyst, and co-lead with manuscript. MK was lead biostatistician and guided the analysis and its interpretation and prepared the manuscript. MH mentored and advised the research fellows throughout the entire study and prepared the manuscript. JH advised on clincial cardiological issues, data interpretation, and prepared the manuscript. FMS was the expert analyst on cardiovascular linked data and prepared the manuscript. KJ involved with data interpretation and prepared the manuscript. PLT provided clincial advice on cardiovascular disease, interpreted data, and prepared the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by the University of Western Australia and the WHO MONICA project.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The protocol for the study was approved by the human research ethics committees of the University of Western Australia and independent State Department of Health.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b36

References

- 1.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Vanuzzo D, Hobbs M, Mahonen M, Cepaitis Z, Kuulasmaa K, et al. Estimation of contribution of changes in coronary care to improving survival, event rates, and coronary heart disease mortality across the WHO MONICA project populations. Lancet 2000;355:688-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaglehole R, Stewart AW, Jackson R, Dobson AJ, McElduff P, D’Este K, et al. Declining rates of coronary heart disease in New Zealand and Australia, 1983-1993. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:707-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElduff P, Dobson A, Jamrozik K, Hobbs M. The WHO MONICA study in Australia, 1984-93: a summary of the Newcastle and Perth MONICA projects. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2000. (Report No AIHW, Cat No 11.)

- 4.Thompson PL, Nidorf SM, Parsons RW, Jamrozik KD, Hobbs MS. The benefits of beta-blockade at the time of myocardial infarction. J Hypertens Suppl 1991;9:S35-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czarn AO, Jamrozik K, Hobbs MS, Thompson PL. Follow-up care after acute myocardial infarction. Med J Aust 1992;157:302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ISIS-2. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. ISIS-2 (second international study of infarct survival) collaborative group. Lancet 1988;2:349-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yusuf S, Wittes J, Friedman L. Overview of results of randomized clinical trials in heart disease. I. Treatments following myocardial infarction. JAMA 1988;260:2088-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Secondary prevention of vascular disease by prolonged antiplatelet treatment. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. BMJ 1988;296:320-31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagerqvist B, Husted S, Kontny F, Naslund U, Stahle E, Swahn E, et al. A long-term perspective on the protective effects of an early invasive strategy in unstable coronary artery disease: two-year follow-up of the FRISC-II invasive study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:1902-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox KA, Poole-Wilson PA, Henderson RA, Clayton TC, Chamberlain DA, Shaw TR, et al. Interventional versus conservative treatment for patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomised trial. Randomized intervention trial of unstable angina. Lancet 2002;360:743-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health. National service framework (NSF) for coronary heart disease. London: DH, 2000.

- 12.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, Arveiler D, Rajakangas AM, Pajak A. Myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA Project. Registration procedures, event rates, and case-fatality rates in 38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation 1994;90:583-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin CA, Chung KC, Lim W, Wong KK. The problem of home management in the estimation of the incidence of acute myocardial infarction from hospital records. J Chronic Dis 1986;39:683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin CA, Hobbs MS, Armstrong BK. Estimation of myocardial infarction mortality from routinely collected data in Western Australia. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:661-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin CA, Hobbs MS, Armstrong BK, de Klerk NH. Trends in the incidence of myocardial infarction in Western Australia between 1971 and 1982. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129:655-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamrozik K, Dobson AJ, Hobbs MS, McElduff P, Ring I, D’Este K, et al. Monitoring the incidence of cardiovascular disease in Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2001. (Cardiovascular Disease Series No 17; AIHW Cat No CVD 16.)

- 17.Norman PE, Semmens JB, Lawrence-Brown MMD, Holman CDJ. Long term relative survival after surgery for population based study abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia. BMJ 1998;317:852-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs DR Jr, Kroenke C, Crow R, Deshpande M, Gu DF, Gatewood L, et al. PREDICT: a simple risk score for clinical severity and long-term prognosis after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina: the Minnesota Heart Survey. Circulation 1999;100:599-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobbs MST, McCaul KA, Knuiman MW, Rankin JM, Gilfillan I. Trends in coronary artery revascularisation procedures in Western Australia, 1980-2001. Heart 2004;90:1036-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herlitz J, Bang A, Sjolin M, Karlson BW. Five-year mortality after acute myocardial infarction in relation to previous history, level of care, complications in hospital, and medication at discharge. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1996;10:485-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Botkin NF, Spencer FA, Goldberg RJ, Lessard D, Yarzebski J, Gore JM. Changing trends in the long-term prognosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Am Heart J 2006;151:199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobbs MS, Knuiman MW, Briffa TG, Ngo H, Jamrozik K. Plasma cholesterol levels continue to decline despite the rising prevalence of obesity: population trends in Perth, Western Australia, 1980-1999. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2008;15:319-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capewell S, Livingston BM, MacIntyre K, Chalmers JWT, Boyd J, Finlayson A, et al. Trends in case-fatality in 117 718 patients admitted with acute myocardial infarction in Scotland. Eur Heart J 2000;21:1833-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Mittleman MA, Levin R, Winkelmayer WC. Improvements in long-term mortality after myocardial infarction and increased use of cardiovascular drugs after discharge: a 10-year trend analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1247-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glesby MJ, Hoover DR. Survivor treatment selection bias in observational studies: examples from the AIDS literature. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:999-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1516-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGovern PG, Jacobs DR Jr, Shahar E, Arnett DK, Folsom AR, Blackburn H, et al. Trends in acute coronary heart disease mortality, morbidity, and medical care from 1985 through 1997: the Minnesota heart survey. Circulation 2001;104:19-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGovern PG, Folsom AR, Sprafka JM, Burke GL, Doliszny KM, Demirovic J, et al. Trends in survival of hospitalized myocardial infarction patients between 1970 and 1985. The Minnesota Heart Survey. Circulation 1992;85:172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGovern PG, Pankow JS, Shahar E, Doliszny KM, Folsom AR, Blackburn H, et al. Recent trends in acute coronary heart disease—mortality, morbidity, medical care, and risk factors. The Minnesota Heart Survey Investigators. N Engl J Med 1996;334:884-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM. A two-decades (1975 to 1995) long experience in the incidence, in-hospital and long-term case-fatality rates of acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sala J, Marrugat J, Masia R, Porta M, The Regicor I. Improvement in survival after myocardial infarction between 1978-85 and 1986-88 in the REGICOR Study. Eur Heart J 1995;16:779-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor R, Dobson A, Mirzaei M. Contribution of changes in risk factors to the decline of coronary heart disease mortality in Australia over three decades. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2006;13:760-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Cooper LS, Conwill DE, Clegg L, et al. Trends in the incidence of myocardial infarction and in mortality due to coronary heart disease, 1987 to 1994. N Engl J Med 1998;339:861-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kattainen A, Salomaa V, Harkanen T, Jula A, Kaaja R, Kesaniemi YA, et al. Coronary heart disease: from a disease of middle-aged men in the late 1970s to a disease of elderly women in the 2000s. Eur Heart J 2006;27:296-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]