Abstract

Background

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is becoming more common, particularly among cancer patients. We sought to define the frequency of CAM use among general surgery, hepatobiliary and surgical oncology patients and to define some of the determinants of CAM use in patients with benign and malignant disease.

Methods

We asked all patients attending the clinics of 3 hepatobiliary/surgical oncology surgeons from 2002 to 2005 to voluntarily respond on first and subsequent visits to a questionnaire related to the use of CAM. We randomly selected patients for review.

Results

We reviewed a total of 490 surveys from 357 patients. Overall CAM use was 27%. There was significantly more CAM use among cancer (34%) versus noncancer patients (21%; p = 0.008), and the use of CAM was more common in patients with unresectable cancer (51%) than resectable cancer (22%; p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in use between men and women. There did not appear to be a change in CAM use with progression of cancer. The most common CAM was herbs or supplements (58% of all users), which were most frequently used by patients with malignant disease. Among the 27 herbs reported to be ingested, 10 are associated with bleeding and hepatotoxicity, as described in the literature.

Conclusion

Prospective studies evaluating surgical outcomes related to CAM use are needed.

Abstract

Contexte

Le recours aux médecines complémentaires et parallèles (MCP) devient plus courant, particulièrement chez les patients atteints de cancer. Nous avons cherché à cerner la fréquence du recours aux MCP chez les patients en chirurgie générale, chirurgie hépatobiliaire et oncologie chirurgicale, et à définir certains des déterminants du recours aux MCP chez les patients atteints de maladie bénigne et maligne.

Méthodes

Nous avons demandé à tous les patients qui se sont présentés aux cliniques de 3 chirurgiens en oncologie chirurgicale et chirurgie hépatobiliaire de 2002 à 2005 de répondre volontairement, au cours de leur première consultation et des visites subséquentes, à un questionnaire portant sur le recours aux MCP. Nous avons choisi les patients au hasard pour l’étude.

Résultats

Nous avons étudié au total 490 questionnaires remplis par 357 patients. Dans l’ensemble, le recours aux MCP s’établissait à 27 %. Il était beaucoup plus important chez les patients atteints de cancer (34 %) que chez les autres (21 %; p = 0,008) et le recours aux MCP était plus courant chez les patients atteints d’un cancer irrésécable (51 %) que chez ceux qui étaient atteints d’un cancer résécable (22 %; p < 0,001). Il n’y avait pas de différence importante de recours aux MCP entre les hommes et les femmes. Le recours aux MCP ne semblait pas changer avec l’évolution du cancer. Les MCP les plus courantes étaient les plantes médicinales ou les suppléments (58 % de tous les utilisateurs), que les patients atteints d’une maladie maligne utilisaient le plus souvent. Parmi les 27 plantes médicinales que l’on a déclaré prendre, 10 sont associées à des saignements et à une hépatotoxicité décrites dans les publications.

Conclusion

Des études prospectives évaluant les résultats chirurgicaux reliés au recours aux MCP s’imposent.

The use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) has gained enormous public enthusiasm over the last 2 decades in North America.1 The use of CAM is common in the general population, and even more so among cancer patients.2–7 In presurgical patients specifically, usage rates have been reported to range from 22% to 32%.3,4 For the purposes of this study, we defined CAM as a group of medical practices that are not in conformity with the standards of the medical community. These practices are not taught at medical schools and are not generally available in hospital-based practices.8

There is growing evidence that the use of CAM impacts conventional medical therapy. For example, there are many well-described adverse events related to bleeding and hepatotoxicity in patients using CAM.4,9–15 Unfortunately, most published papers relating to CAM use are case reports and appeared in non–peer reviewed sources. To our knowledge, the use of CAM in general surgery, hepatobiliary and surgical oncology patients has not been investigated. This population is unique in that patient comorbidities are common and surgical morbidity and mortality are substantial.16 Complications related to general surgery, cancer surgery and hepatobiliary surgery are frequent, and they are often directly related to bleeding, infection and impairment in liver function. Given that CAM use may affect surgical outcomes in hepatobiliary and surgical oncology patients, it would be useful to establish a basic understanding of patterns of CAM use in this patient population. Our objectives were to define the frequency of CAM use in this patient population, to define patient characteristics associated with CAM use and to determine the types of CAM being employed.

Methods

We asked all patients attending the outpatient clinics of 3 participating subspecialist hepatobiliary/surgical oncologists and general surgeons (O.F.B., E.D., F.S.) from 2002 to 2005 to voluntarily respond to a written questionnaire related to the use of CAM. The questionnaire was administered on the initial clinic visit and repeated on all subsequent clinic visits. We randomly selected patient charts from the 3 participating surgeons for review. Random selection involved reviewing every 3–4 clinic charts, which were arranged in a filing cabinet in alphabetical order. We therefore considered the demographic and clinical characteristics of the selected study cohort to reflect the patient population served by the participating surgeons. We extracted related clinical data from surgeons’ clinic charts and supporting charts from the local cancer clinic. The Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the Faculties of Medicine, Nursing and Kinesiology, University of Calgary, granted ethical approval for the study.

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe the study cohort. Means and standard deviations described continuous variables. To evaluate demographic and clinical factors that typify each group, we performed univariate analysis to examine the difference between CAM and non-CAM users. We used a 2-tailed Student t test to compare continuous variables and a 2-tailed Fisher exact test to compare proportions. We considered p ≤ 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

We randomly selected and reviewed a total of 490 surveys from 357 patients. Of these, 81 patients repeated the surveys. Patient characteristics, including age, sex and cancer status are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 53.5 (range 14–89) years. Overall, slightly more respondents were women than men, and there were more patients with benign disease than cancer. There was a wide range of benign and malignant diseases represented in the study population, with biliary disease being the most common benign condition.

Table 1.

Characteristics of surveyed patients of a hepatobbiliary/surgical oncology practice

| Characteristic | No. (%)* |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 357 |

| No. of surveys | 490 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 168 (47) |

| Female | 189 (53) |

| Disease status | |

| Benign | 205 (57) |

| Malignant | 152 (43) |

| Resectablility of cancers† | |

| Resectable | 85 (56) |

| Unresectable | 65 (43) |

| N/A (e.g. lymphoma) | 2 (1) |

N/A = not applicable.

Unless otherwise indicated.

Patients with potentially resectable cancer are those who had tumours that were potentially resectable for cure at the time of the initial questionnaire.

We defined patients as cancer patients if they had any history of malignancy, even if the malignancy did not directly relate to their surgical problems. Of the 152 cancer patients, most had periampullary and pancreatic cancers (29%) or primary hepatobiliary cancers (28%), 11% had breast cancer, 8% had genitourinary cancers, 7% had gastric cancer and 5% had colorectal cancer. The remaining 12% had other miscellaneous malignancies. We considered patients to have “resectable cancer” if they had undergone a resection in the recent past or if they presented with a potentially resectable new cancer at the time of the initial visit/survey. This group represented a rough surrogate for potential curability.

Complementary and alternative medicine use

Overall, 27% of patients used CAM. Table 2 demonstrates CAM use as a function of various clinical and demographic factors. There was significantly more CAM use among cancer than noncancer patients (34% v. 21%, p = 0.008). Likewise, there was significantly more CAM use among patients with unresectable cancer than those with potentially resectable disease (51% v. 22%, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Complementary and alternative medicine use as a function of patient characteristics

| Characteristic | CAM use; no. (%) of patients* | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Age, mean (SD) yr | 54 (15) | 56 (16) | 0.62 |

| Sex | 0.10 | ||

| Male | 37 (22) | 131 (78) | |

| Female | 59 (31) | 130 (69) | |

| Disease status | 0.008 | ||

| Benign | 44 (21) | 161 (79) | |

| Malignant | 52 (34) | 100 (66) | |

| Respectability of cancers† | < 0.001 | ||

| Potentially resectable | 19 (22) | 66 (78) | |

| Unresectable | 33 (51) | 32 (49) | |

CAM = complementary and alternative medicine; SD = standard deviation.

Unless otherwise indicated.

Patients with potentially resectable cancer are those who had tumours that were potentially resectable for cure at the time of the initial questionnaire.

Changes in CAM use over time in cancer patients

Eighty-one patients completed multiple surveys. Of these, 16 (20%) reported a change in CAM use over time; 15 of them were cancer patients. Of these 15 cancer patients, 11 had progressive cancer during the period of observation, and 4 had stable/cured disease. Of the 11 with progressive cancer, 7 started using CAM with advancing disease, whereas 4 stopped using CAM with advancing disease. There was no clear relation between advancing disease and a corresponding change in CAM use.

Types of and reasons for CAM use

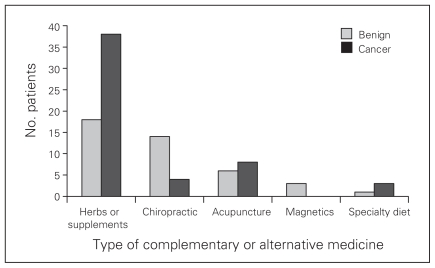

Overall, the most commonly used form of CAM was herbs or supplements (Fig. 1); 58% of all patients used these CAMs. Of CAM users, a larger proportion of patients with malignant than benign disease used herbs and supplements (73% v. 41%, p = 0.002). Other forms of CAM reportedly used included chiropractic services and massage, acupuncture, magnetics and specialty diets. There was no difference in the proportion of patients with benign and malignant disease using these forms of CAM.

Fig. 1.

Types of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) used by surveyed patients of a hepatobiliary/surgical oncology practice. Individuals may have reported using more than 1 type of CAM.

There were various reasons reported for using CAMs. Overall, the 3 most commonly cited reasons for CAM use were to “boost immunity” (n = 39, 41%), “enhance energy” (n = 32, 33%) and “fight cancer” (n = 18, 19%). There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients with benign or malignant disease who cited these reasons for using CAMs. Patients with malignant disease were more likely to report that they used CAM to fight cancer (27% v. 9%, p = 0.035) or to not specify any reason for using CAM (44% v. 5%, p < 0.001).

Potential risks associated with specific CAMs

Table 3 lists all of the specific herbs and supplements reportedly used by respondents, including any potential surgical risks as described in the literature. Among the 56 patients who reported using one or more herbs or supplements, there were 27 specific herbal ingredients reported. Of these, 10 were associated with excessive bleeding and or hepatotoxicity in the medical literature. Also of importance, many individuals reportedly used herbal and vitamin supplements for which the exact constituents were unknown.

Table 3.

Herbs and supplements reportedly used by patients surveyed, including potential adverse effects described in the literature

| Type of herb or supplement | No. of patients reporting use | Potential adverse effect described in the literature |

|---|---|---|

| Herbs not specified | 36 | |

| Vitamins not specified | 23 | |

| Chinese herbs | 5 | Interstitial nephropathy17 |

| Garlic | 3 | Inhibits platelet aggregation9 |

| Glucosamine | 2 | Bleeding, hypoglycemia4 |

| Selenium | 2 | None |

| Echinacea | 2 | Hepatotoxicity15 |

| Molasses | 1 | None |

| Turmeric | 1 | None |

| Ginseng | 1 | Bleeding/inhibition of platelet aggregation10,11 |

| Milk thistle | 1 | Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting18 |

| St. Johns wort | 1 | Altered hepatic metabolism of prescription medications19 |

| Cod liver oil | 1 | Bleeding12 |

| Oncolyn | 1 | None |

| Acidophilus | 1 | Liver abscess20 |

| Saw palmetto | 1 | Bleeding13 |

| Grape seed | 1 | None |

| Licorice | 1 | Rhabdomyolysis21 |

| Dandelion | 1 | Cardiac arrhythmia22 |

| Evening primrose oil | 1 | Decreased seizure threshold15 |

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study represents the first description of CAM use in patients encountered in a subspecialist hepatobiliary, surgical oncology and general surgery practice. There are a few important observations noted from this study. First, overall 27% of patients surveyed reported some form of CAM use, which is consistent with generally reported rates of usage in the literature.3,4 Second, cancer patients in this study reported a significantly greater CAM use (34%) than patients with benign disease (21%). This is also consistent with published data23,24 and satisfies our initial hypothesis. Third, about 20% of patients who completed multiple surveys reported a change in CAM use over time. However, contrary to our initial hypothesis, there did not appear to be a consistent relation between CAM use and progression of cancer. Finally, the 3 most commonly reported reasons for use of CAM among cancer patients were to “fight cancer,” “boost immunity” and “enhance energy.”

Of particular interest in our study are the types of CAM used. The most common form of CAM use was herbs and supplements. Given that there are well-described potential surgical risks, including bleeding and acute hepatotoxicity,4,9–15 associated with some herbs and supplements, this is an important observation in the context of a hepatobiliary and surgical oncology practice. This observation has led us to routinely provide instructions in our preoperative orders to stop using all herbs and supplements 1 week before any surgery. This is particularly important in instances where the exact constituents of CAMs and their associated effects are unknown.

This exploratory study was not designed to define outcomes as a function of CAM use. Therefore, we cannot comment definitively on whether any of the toxicities ascribable to CAMs listed in Table 3 occurred in our study cohort. To make a more accurate assessment of the effects of CAMs on surgical outcomes, the outcomes of a specific population will have to be measured in relation to CAM use. For example, perioperative or long-term outcomes in patients undergoing liver resection or pancreaticoduodenectomy can be studied as a function of CAM use. Unfortunately, even in those studies, because of the wide variations in types of CAM used by patients, it will be difficult to identify less common adverse effects related to any particular CAM.

We have attempted to elucidate the reasons and motivations behind patients’ decisions to use CAMs. Using survey methodology, we have made some observations on the frequency of CAM use that we consider generalizable to the patient population we serve. However, survey methodology has some inherent weaknesses. Our surveys provide only verbal descriptions of CAM use and categorical descriptions of why CAMs are used. It is possible that responses do not accurately describe whether respondents actually use CAMs, nor are they likely to comprehensively describe the motivations underlying the decision to use a particular CAM. This is especially true in the context of a surgeon’s clinic, as patients may be reluctant to admit that they use CAMs. It is likely that the reasons and motivations behind patients’ choices would be better elucidated using focus group methodology (where patients are not isolated and less intimidated) and other more sophisticated qualitative methods.

Our findings demonstrate that CAM use is frequently encountered in clinical practice. The implications of CAM use on one’s clinical practice depend on the types of diseases typically managed. It is therefore important to at least be aware of the toxicities and drug interactions that may adversely impact on relevant outcomes. Eisenberg and colleagues7 define CAM as “medical interventions not taught widely in US medical schools or generally available in US hospitals.” In a survey done in 1998 of 16 Canadian medical schools, 13 stated that they provided education on CAMs.25 At about the same time, in a national survey done in the United States, 75 (64%) of 117 medical schools that responded reported offering elective courses in CAM or included these topics in required courses.26 Whereas these studies demonstrated awareness of CAM and acceptance by faculty of the importance of a conceptual overview of CAM, both studies demonstrated considerable variability in the content and format of courses offered. There is certainly a need for medical educators to recognize the wide use of nonorthodox treatments, but it is unlikely that any medical school will convey a detailed knowledge of various CAMs. Therefore, it is incumbent on the practitioner to gain some awareness of the impact of CAMs on his or her practice.

Conclusion

Patients with hepatobiliary disease or advanced cancers who undergo major abdominal surgeries such as partial liver resection or pancreas resection have among the highest complication rates of all surgeries. This study demonstrates that a significant proportion of hepatobiliary/surgical oncology patients use CAM. It is possible that CAM use represents an important and currently underappreciated contributor to surgical complications and it will be important to elucidate its contribution to adverse outcomes. This information is of immediate benefit to currently practising hepatobiliary surgeons and surgical oncologists and should provide motivation to openly discuss and understand patients’ CAM use as part of surgical planning. Descriptive studies like this one lend further support to research on the impact of CAM on surgical outcomes.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared for Drs. Schieman, Rudmik, Sutherland and Bathe. Dr. Dixon has received speaker fees and travel assistance from Bayer and Novartis.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. Drs. Schieman, Rudmik and Sutherland acquired the data, which Drs. Schieman and Rudmik analyzed. Drs. Schieman and Bathe wrote the article, which all authors reviewed and approved for publication.

References

- 1.Pan CX, Morrison RS, Ness J, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in the management of pain, dyspnea, and nausea and vomiting near the end of life. A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:374–87. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286:208–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsen LC, Segal S, Pothier M, et al. Alternative medicine use in presurgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:148–51. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200007000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaye AD, Clarke RC, Sabar R, et al. Herbal medicines: current trends in anesthesiology practice — a hospital survey. J Clin Anesth. 2000;12:468–71. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(00)00195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerner IJ, Kennedy BJ. The prevalence of questionable methods of cancer treatment in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 1992;42:181–91. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.42.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiger WA, Smith M, Boon H, et al. Advising patients who seek complementary and alternative medical therapies for cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:889–903. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teranishi K, Apitz-Castro R, Robson SC, et al. Inhibition of baboon platelet aggregation in vitro and in vivo by the garlic derivative, ajoene. Xenotransplantation. 2003;10:374–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2003.02068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura Y, Okuda H, Arichi S. Effects of various ginseng saponins on 5-hydroxytryptamine release and aggregation in human platelets. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1988;40:838–43. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1988.tb06285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo SC, Teng CM, Lee JC, et al. Antiplatelet components in Panax ginseng. Planta Med. 1990;56:164–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim DN, Eastman A, Baker JE, et al. Fish oil, atherogenesis, and thrombogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;748:474–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb17343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheema P, El-Mefty O, Jazieh AR. Intraoperative haemorrhage associated with the use of extract of Saw Palmetto herb: a case report and review of literature. J Intern Med. 2001;250:167–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pittler MH, Ernst E. Systematic review: hepatotoxic events associated with herbal medicinal products. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:451–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller LG. Herbal medicinals: selected clinical considerations focusing on known or potential drug-herb interactions. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2200–11. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.20.2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spanknebel K, Conlon KC. Advances in the surgical management of pancreatic cancer. Cancer J. 2001;7:312–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reginster F, Jadoul M, van Ypersele de Strihou C. Chinese herbs nephropathy presentation, natural history and fate after transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:81–6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuber R, Modriansky M, Dvorak Z, et al. Effect of silybin and its congeners on human liver microsomal cytochrome P450 activities. Phytother Res. 2002;16:632–8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obach RS. Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 enzymes by constituents of St. John’s Wort, an herbal preparation used in the treatment of depression. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:88–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cukovic-Cavka S, Likic R, Francetic I, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus as a cause of liver abscess in a NOD2/CARD15-positive patient with Crohn’s disease. Digestion. 2006;73:107–10. doi: 10.1159/000094041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Firenzuoli F, Gori L. [Rhabdomyolysis due to licorice ingestion] [Article in Italian] Recenti Prog Med. 2002;93:482–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal SC, Crook JR, Pepper CB. Herbal remedies-how safe are they? A case report of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia/ ventricular fibrillation induced by herbal medication used for obesity. Int J Cardiol. 2006;106:260–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saydah SH, Eberhardt MS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among adults with chronic diseases: United States 2002. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:805–12. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansky PJ, Wallerstedt DB. Complementary medicine in palliative care and cancer symptom management. Cancer J. 2006;12:425–31. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruedy J, Kaufman DM, MacLeod H. Alternative and complementary medicine in Canadian medical schools: a survey. CMAJ. 1999;160:816–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wetzel MS, Eisenberg DM, Kaptchuk TJ. Courses involving complementary and alternative medicine at US medical schools. JAMA. 1998;280:784–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.9.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]