Abstract

Complement cascade plasma proteins have a complex role in the etiopathogenesis of SLE. Hereditary C1q deficiency has been strongly related to SLE; however, there are very few published SLE studies that evaluate the polymorphisms of the genes encoding for C1q (A, B, and C). In this study, we evaluated 17 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across 37 kb of C1QA, B and C in a lupus cohort of peoples of African-American and Hispanic origin. In a case only analysis, significant association at multiple SNPs in the C1QA gene was detected in African-Americans with kidney nephritis (best p=4.91 × 10−6). In addition, C1QA was associated with SLE in African-Americans with a lack of nephritis and accompanying photosensitivity when compared to normal controls (p=6.80 × 10−6). A similar trend was observed in the Hispanic subjects (p=0.003). Quantitative analysis demonstrates that some SNPs in the C1q genes might be correlated with C3 complement levels in an additive model among African-Americans (best p=0.0001). The CIQA gene is associated with subphenotypes of lupus in African-American and Hispanic subjects. Further studies with higher SNP densities in this region and other complement components are necessary to elucidate the complex genetics and phenotypic interactions between complement components and SLE.

Introduction

Complement cascade plasma proteins, the key components of the innate immune system, have a complex role in SLE etiopathogenesis. It has been known for decades that activation of the complement system is necessary for subsequent tissue inflammation and damage after immune complex deposition. However, and paradoxically, deficiencies of different components of the complement classical pathway (e.g. C1, C2 and C4) have also been associated with the development of SLE (1–3). Complement proteins not only have important roles in host resistance to bacterial infection, but also in the clearance of immune complexes and, therefore, prevention of autoimmunity. In addition, complements have important roles in lymph node organization, B cell maturation, differentiation and tolerance and IgG isotype switching (4,5).

C2, C4A, C4B and factor B are complement components with genetic locations within the MHC class III region. Different alleles of these three components are linked to particular HLA haplotypes and are inherited as extended MHC haplotypes, or complotypes. Considerable differences in complotype frequencies have been observed among various SLE racial groups (6–8).

C1q is the first component of the classical pathway of complement activation and, together with the enzymatically active components C1r and C1s, forms the C1 complex. Binding of C1 to immunoglobulins in the form of immune complexes leads to the activation of proteases C1r and C1s and a further activation of the classical pathway of complement. Complete C1q deficiency, though rare, is highly predictive of the risk for lupus (>90%) and is associated with severe disease and glomerulonephritis. About 20 families with C1 (C1q, C1r, C1s) deficiencies have been described in the literature and heterozygous deficiencies are difficult to identify (9,10).

C1q is composed of three different species of chains, called A, B, and C. The genes for the A, B, and C chains of C1q are tandemly arranged 5-prime to 3-prime in the order A-C-B on a 24-kb stretch of DNA and closely linked together on chromosome 1p36 (12). C1q deficiency is caused either by a failure to synthesize C1q or by synthesis of low molecular weight (LMW) C1q (10). Different coding mutations have been identified that lead to a premature termination codon at different amino acid residues (9–10). In addition to coding mutations in patients with complete deficiency of C1q which are very rare, a common silent SNP (GGG→GGA) (rs172378) of the C1qA gene has been found to be associated with decreased levels of C1q in patients with subacute cutaneous lupus (SCLE) (11). The cause of such reduced levels of C1q is not known.

In this report, we describe the results of a fine mapping study in which we evaluated 17 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) spanning the C1Q genes on chromosome 1 in a large collection of 2214 African-American and Hispanic lupus cases and controls. This study is the largest published study of these genes in SLE and the first to investigate the associations in African Americans and Hispanics.

Results

Lack of Association of SLE with C1q

To determine if C1q associates with SLE, we genotyped 16 SNPs in C1q that span the C1A, C and B genes in our subjects. SNPs were selected from the tag-SNPs genotyped by the International HapMap Project to capture common variations in this region (r2 >0.8) plus additional rare coding SNPs. After removing monomorphic SNPs and SNPs that were out of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, 11 and 12 SNPs were subsequently used for analyses in the African-Americans and Hispanics, respectively. Furthermore, one additional SNP (rs172378) that had been previously genotyped in part of these samples was merged into this dataset. This SNP, also called C1qA-Gly70 has been associated with SCLE as mentioned previously (11). We did not observe significant association with any of the selected SNPs in our populations using the presence of SLE as a phenotype (Data not shown).

Subset analyses

We then evaluated these SNPs and cases selected for the presence of each of the 11 ACR criteria, presence of autoantibodies (anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-RNP, anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm), gender and age of onset for association with SLE. In addition, to verify that we had sufficient power to detect a moderate effect given the reduced sample sizes found in the subset analyses, we calculated power for each subgroup presented below (see methods). Power for each of the subset samples, assuming type I error of 0.05 reported in the result section are as follows: 293 cases/770 controls = 0.95 (Table 2), 125 cases/770 controls = 0.66 (Table 3a), 50 cases/209 controls = 0.32 (Table 3b), 128 cases/770 controls = 0.67 (Table 4), 141 cases/128 controls = 0.71(Table 5a), 249 cases/293 controls = 0.92 (Table 5b).

Table 2.

Comparison of 293 independent African-American cases with lack of nephritis with 770 African-American healthy controls.

| CHR | SNP | BP | Minor Allele | Case | Control | Major Allele | CHISQ | P | FDR-qb | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs665691 | 22832941 | G | 0.2791 | 0.2104 | C | 11.32 | 0.000769 | 0.006 | 1.453 |

| 1 | rs2935542 | 22836058 | G | 0.0839 | 0.1065 | A | 2.395 | 0.1217 | 0.207 | 0.7685 |

| 1 | rs172378a | 22838025 | A | 0.3704 | 0.2625 | G | 12.66 | 0.000374 | 0.006 | 1.653 |

| 1 | rs12033074 | 22839196 | C | 0.3627 | 0.4094 | G | 3.403 | 0.06509 | 0.123 | 0.8211 |

| 1 | rs4655085 | 22841012 | A | 0.2842 | 0.3151 | G | 1.895 | 0.1686 | 0.260 | 0.8632 |

| 1 | rs12404537 | 22841955 | A | 0.03938 | 0.04091 | G | 0.02536 | 0.8735 | 0.902 | 0.9612 |

| 1 | rs672693 | 22844033 | G | 0.4966 | 0.4494 | A | 3.799 | 0.05129 | 0.109 | 1.209 |

| 1 | rs294185 | 22844479 | A | 0.2483 | 0.1955 | G | 7.125 | 0.007602 | 0.025 | 1.36 |

| 1 | rs294183 | 22844685 | G | 0.25 | 0.1968 | A | 7.201 | 0.007285 | 0.025 | 1.361 |

| 1 | rs12756603 | 22854463 | G | 0.3202 | 0.3344 | A | 0.3864 | 0.5342 | 0.648 | 0.9375 |

| 1 | rs629409 | 22859325 | A | 0.3579 | 0.4338 | G | 10.06 | 0.001515 | 0.008 | 0.7275 |

| 1 | rs7549747 | 22869158 | A | 0.3031 | 0.276 | G | 1.532 | 0.2158 | 0.305 | 1.141 |

The snp rs172378 has been merged from previous study and for this snp data available for 135 AA cases with this subphenotype and 600 AA controls.

FDR=False Discovery Rate

Table 3.

| Table 3a: comparison of 125 independent African-American cases with photosensitivity and lack of nephritis and 770 African-American healthy controls. | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHR | SNP | BP | Minor Allele | Case | Control | Major Allele | CHISQ | P | FDR-q | OR |

| 1 | rs665691 | 22832941 | G | 0.284 | 0.2104 | C | 6.777 | 0.009235 | 0.039 | 1.489 |

| 1 | rs2935542 | 22836058 | G | 0.048 | 0.1065 | A | 8.301 | 0.003963 | 0.033 | 0.423 |

| 1 | rs172378 | 22838025 | A | 0.4636 | 0.2625 | G | 20.25 | 6.80E–06 | 0.0001 | 2.429 |

| 1 | rs12033074 | 22839196 | C | 0.3839 | 0.4094 | G | 0.5203 | 0.4707 | 0.534 | 0.899 |

| 1 | rs4655085 | 22841012 | A | 0.248 | 0.3151 | G | 4.561 | 0.0327 | 0.061 | 0.7168 |

| 1 | rs12404537 | 22841955 | A | 0.032 | 0.04091 | G | 0.4482 | 0.5032 | 0.534 | 0.775 |

| 1 | rs672693 | 22844033 | G | 0.54 | 0.4494 | A | 7.111 | 0.007663 | 0.039 | 1.439 |

| 1 | rs294185 | 22844479 | A | 0.26 | 0.1955 | G | 5.509 | 0.01892 | 0.046 | 1.446 |

| 1 | rs294183 | 22844685 | G | 0.26 | 0.1968 | A | 5.268 | 0.02172 | 0.046 | 1.434 |

| 1 | rs12756603 | 22854463 | G | 0.376 | 0.3344 | A | 1.657 | 0.198 | 0.306 | 1.199 |

| 1 | rs629409 | 22859325 | A | 0.356 | 0.4338 | G | 5.33 | 0.02097 | 0.046 | 0.7216 |

| 1 | rs7549747 | 22869158 | A | 0.276 | 0.276 | G | 7.26E–07 | 0.9993 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Table 3b: comparison of Hispanic cases with photosensitivity and lack of nephritis with controls (50 cases, 209 controls) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHR | SNP | BP | Minor Allele | Case | Control | Major Allele | CHISQ | P | FDR-q | OR |

| 1 | rs665691 | 22832941 | G | 0.55 | 0.39 | C | 8.481 | 0.003589 | 0.016 | 1.912 |

| 1 | rs2935542 | 22836058 | G | 0.02 | 0.1077 | A | 7.515 | 0.006118 | 0.017 | 0.1692 |

| 1 | rs172378 | 22838025 | A | 0.6111 | 0.4135 | G | 8.401 | 0.003751 | 0.016 | 2.229 |

| 1 | rs12033074 | 22839196 | C | 0.2955 | 0.4619 | G | 8.127 | 0.004362 | 0.016 | 0.4885 |

| 1 | rs4655085 | 22841012 | A | 0.04 | 0.1196 | G | 5.478 | 0.01926 | 0.044 | 0.3067 |

| 1 | rs12404537 | 22841955 | A | 0.19 | 0.2201 | G | 0.4341 | 0.51 | 0.649 | 0.8312 |

| 1 | rs672693 | 22844033 | A | 0.38 | 0.4522 | G | 1.706 | 0.1914 | 0.268 | 0.7426 |

| 1 | rs294185 | 22844479 | G | 0.4 | 0.4784 | A | 1.991 | 0.1582 | 0.268 | 0.727 |

| 1 | rs294183 | 22844685 | A | 0.4 | 0.4785 | G | 1.998 | 0.1575 | 0.268 | 0.7267 |

| 1 | rs9434 | 22846884 | A | 0.4 | 0.4728 | C | 1.71 | 0.191 | 0.268 | 0.7435 |

| 1 | rs12756603 | 22854463 | G | 0.11 | 0.1053 | A | 0.01908 | 0.8901 | 0.890 | 1.051 |

| 1 | rs629409 | 22859325 | A | 0.11 | 0.2392 | G | 8.005 | 0.004666 | 0.016 | 0.393 |

| 1 | rs7549747 | 22869158 | G | 0.43 | 0.4545 | A | 0.1964 | 0.6576 | 0.767 | 0.9053 |

Table 4.

Results in 128 African-American cases with normal C3 titer and 770 African-American controls.

| CHR | SNP | BP | Minor Allele | Case | Control | Major Allele | CHISQ | P | FDR-q | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs665691 | 22832941 | G | 0.2813 | 0.2104 | C | 6.413 | 0.01133 | 0.050 | 1.469 |

| 1 | rs2935542 | 22836058 | G | 0.1094 | 0.1065 | A | 0.01909 | 0.8901 | 0.954 | 1.03 |

| 1 | rs172378 | 22838025 | A | 0.3883 | 0.2625 | G | 12.77 | 0.000352 | 0.006 | 1.783 |

| 1 | rs12033074 | 22839196 | C | 0.2864 | 0.4094 | G | 11.39 | 0.00074 | 0.006 | 0.579 |

| 1 | rs4655085 | 22841012 | A | 0.3203 | 0.3151 | G | 0.02755 | 0.8682 | 0.954 | 1.024 |

| 1 | rs12404537 | 22841955 | A | 0.02734 | 0.04091 | G | 1.078 | 0.2991 | 0.489 | 0.6591 |

| 1 | rs672693 | 22844033 | G | 0.4805 | 0.4494 | A | 0.8576 | 0.3544 | 0.531 | 1.133 |

| 1 | rs294185 | 22844479 | A | 0.2383 | 0.1955 | G | 2.502 | 0.1137 | 0.237 | 1.288 |

| 1 | rs294183 | 22844685 | G | 0.2422 | 0.1968 | A | 2.798 | 0.09436 | 0.237 | 1.305 |

| 1 | rs12756603 | 22854463 | G | 0.3203 | 0.3344 | A | 0.1967 | 0.6574 | 0.910 | 0.938 |

| 1 | rs629409 | 22859325 | A | 0.3867 | 0.4338 | G | 1.986 | 0.1588 | 0.285 | 0.8231 |

| 1 | rs7549747 | 22869158 | A | 0.332 | 0.276 | G | 3.392 | 0.06549 | 0.196 | 1.304 |

Table 5.

| Table 5a: African-American patients with low C3 (case) compared with African-American patients with normal C3 (control) (141 case and 128 controls) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHR | SNP | BP | Allele1 | Case | Control | Allele2 | CHISQ | P | Permute P* | OR |

| 1 | rs665691 | 22832941 | C | 0.8369 | 0.7188 | G | 10.94 | 0.000943 | 0.013 | 2.008 |

| 1 | rs172378 | 22838025 | G | 0.7708 | 0.6117 | A | 11.29 | 0.00078 | 0.011 | 2.135 |

| 1 | rs12033074 | 22839196 | C | 0.4298 | 0.2864 | G | 9.878 | 0.001672 | 0.022 | 1.878 |

| Table 5b: African-American patients with nephritis (case) compared with African-American patients without nephritis (control) (249 cases and 293 controls) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHR | SNP | BP | Minor Allele | Case | Control | Major Allele | CHISQ | P | Permute P* | OR |

| 1 | rs665691 | 22832941 | G | 0.1627 | 0.2791 | C | 20.87 | 4.91E–06 | 4.91E–06 | 0.5017 |

| 1 | rs172378 | 22838025 | A | 0.2333 | 0.3704 | G | 12.75 | 0.0003 | 0.004 | 0.5174 |

P value after 10000 permutations.

Apart from photosensitivity in African-Americans that showed suggestive associations in multiple SNPs (0.05<p<0.005), there was no significant association in any of the selected SNPs with the ACR criteria. Because photosensitivity tends to be negatively correlated with anti-dsDNA antibodies and, therefore, a milder spectrum of disease, according to our data and other reports (13,14), we chose to then evaluate another possible mild phenotype by selecting a group of patients (293 independent African-American cases) who did not have any evidence of nephritis and compared them to 770 African-American healthy controls. Surprisingly, we detected evidence of multiple associations in C1q SNPs in African-Americans with no nephritis (Table 2). More significant results were obtained in patients with photosensitivity and without nephritis in both African-American (125 cases and 770 Controls) and Hispanic populations (50 cases and 209 controls) (Table 3a and 3b respectively). The best observed result in African-Americans was with rs172378 (p=6.80 × 10−6, FDR-q=0.0001, OR=2.43 (95%CI=1.63–3.60)) and a similar trend was observed at this same SNP in the Hispanic population with the same subphenotype (p=0.003, FDR-q=0.01, OR= 2.23 (95% CI= 1.29–3.86)) (Table 3b).

A lack of nephritis has been correlated with a normal level of complement. When 128 African-American cases with a normal C3 complement level were selected and compared with 770 controls, again, similar associations were found in the same SNPs (Table 4). C1q titers, were not available in our cases. When we only considered C4 or CH50, the association results were less significant or only suggestive (Data not shown).

Haplotype analyses

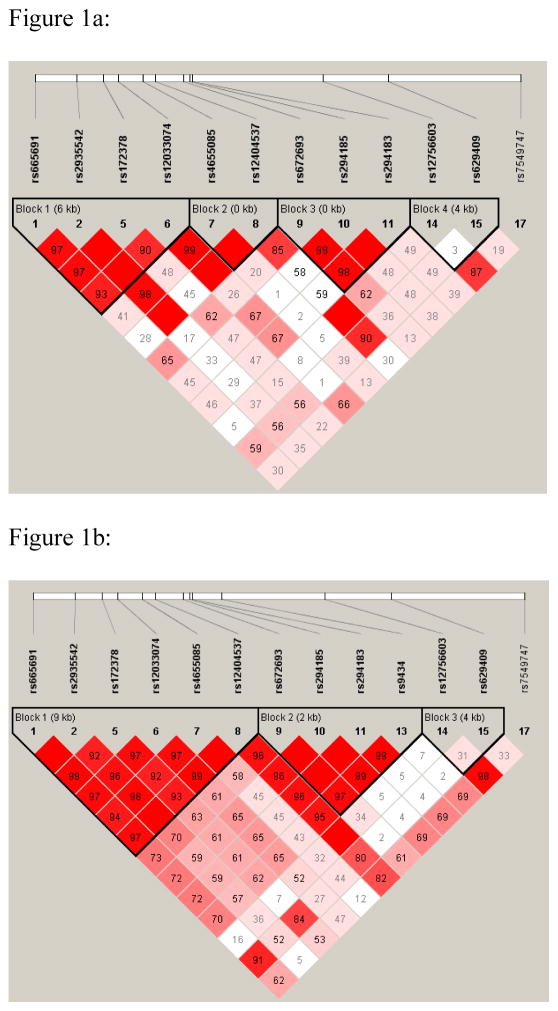

In haplotype analyses, the three significantly associated SNPs mentioned above (rs665691, rs172378, rs12033074) resided in one haplotype block, which spans 6kb in African-Americans (Figure 1a) (GAAG). In the Hispanics, this haplotype block spans 9 Kb and also contains additional SNPs (GAAGGG) (Figure 1b). Two SNPs, rs665691 and rs172378, were highly correlated both in the African-Americans (D′=0.97, r2=0.7) and in Hispanics (D′=0.99, r2=0.88). In patients with no history of nephritis, the GAAG haplotype was significantly increased in African-American cases compared to controls (28% cases vs 20% controls, p=0.0009, OR=1.52 95% CI=1.19–1.93) and in Hispanic cases compared to controls (55% cases vs 38% controls, p =0.002, OR=1.93, 95%CI=1.25–3.00). In addition to this haplotype, other haplotypic blocks were also suggestively significant. Indeed, an expanded haplotype in the African-Americans consists of the first 9 SNPs in Table 3 (block 1, 2 and 3), (GAAGGGGAG), produces a p =5.56 × 10−5 with a frequency of 17% in cases and 9% in controls (OR=2.12 95%CI=1.46–3.07). Conditional analyses in this haplotype suggest that either rs665691 or rs172378 is able to explain the entire observed global association.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a,b: schematic representation of haplotype blocks in African- American (a) and Hispanic (b) population.

Case only analyses

Case only analyses further revealed that there is indeed a significant allelic distribution in SLE patients when kidney nephritis or C3 complement level were considered as phenotypes. We first divided the African-American SLE patients into two groups based on the minimum reported C3 titer: those with low C3 and those who never had lower than a normal range of C3 in their records. We consider patients with low C3 as cases and patients with normal C3 as control (141 case and 128 controls). Indeed, the three alleles, G, A and G for the SNPs rs665691, rs172378 and rs12033074, respectively, were protective against low level of C3 complement and alleles CGC were risk (Best OR=2.13, 95%CI= 1.37–3.38) (Table 5a). In addition, when normalized C3 titers were considered as a quantitative phenotype in a case only analysis, these three SNPs in African-Americans showed significant associations in an additive model (rs665691: p=0.004 for minor allele G, rs172378: p=0.0001 for minor allele A, rs12033074: p=0.001, for major allele G). Similarly, in African-American, when we consider cases with nephritis as case and cases without nephritis as controls (249 cases and 293 controls) we found that the two alleles G, A for SNPs rs665691 and rs172378 were protective against nephritis as well (permute p=4.91 × 10−6, OR= 0.50, (0.37–0.68) (Table 5b). For the Hispanics, the number of cases for these variables were limited, however, the data was supportive (data not shown).

Discussion

In our large genotyping data for SLE patients and controls, none of the selected SNPs in C1q gene were associated when evaluating the presence or absence of SLE as the phenotype. However, in subset analyses, we detected few associations, especially in our African-American population and the results were supportive in our Hispanic population. These subphenotype associations should be interpreted with caution given the smaller sample sizes. On the other hand, since SLE is an extremely heterogeneous disease, with multiple correlated subphenotypes, stratifying by clinical findings can improve genetic homogeneity and thereby more easily reveal genetic effects through improved statistical power.

Apart from multiple case reports of lupus with hereditary C1q deficiency, there are very limited studies that evaluate the polymorphisms of the genes encoding for C1q (A,B,C) in lupus. In one recent study, similarly, a lack of association with SLE has been reported in Malaysian samples (15). In another study, Marthens et al (16) reported the suggestive association of multiple SNPs, especially in the C1QB gene, with low C3, CH50 and more severe SLE in Caucasian trio families; however, none of their results were significant in case control analyses and their sample sizes also were small. They also have not genotyped the snp rs172378 in C1QA gene.

As mentioned above, in addition to various coding mutations in patients with complete deficiency of C1q, which are very rare, a common silent SNP (rs172378) of the C1QA gene has been found to be associated with subacute cutaneous lupus (SCLE) (11). There is no report of association of this SNP with SLE. The major findings in SCLE patients were mostly limited to skin involvement, photosensitivity and no evidence of systemic involvement such as renal disease. Interestingly, in our lupus cases with photosensitivity or those without ACR criterion renal disorder, we have detected similar allelic association to this SNP and the neighborhood SNPs that were in linkage disequilibrium. Petri et al. (17) has reported that almost in all cases with rare coding mutations, this silent SNP mutation can also be observed. Based on the minor allele frequency of this SNP (20%–40%), this mutation is much more frequent in the general population than rare coding variants and we expect that many only posses this single mutation and as reported (11), it has been associated with lower than normal C1q level and SCLE. In addition, both in our data and in reference NCBI there are significant differences in allele frequency for this SNP as well as SNP rs665691 between African-American and Caucasian normal controls. Indeed the minor allele A in African-Americans for SNP rs172378 was the major allele in Europeans. In Hispanics it was somewhere in the middle (41%). Similarly, in SNP rs665691, the major allele G in Europeans was the minor allele in African-Americans. This SNP is located on promoter of C1Q A gene and in LD (D′=1) and is less than 2 kb from the SNP rs587585 that Marthens et al. (16) reported to be suggestively associated with Low CH50 and C1q in Caucasians. Both of these two SNPs are located in the promoter/regulatory region of C1QA gene. In animal studies, a polymorphism in this regulatory region has also been associated with low C1q levels and the development of nephritis in New Zealand Black (NZB) mice and, therefore, the region upstream of C1qA could be potentially important (18). It is not clear whether these polymorphisms may have some triggering role to initiate antibodies against C1q which are thought to play a pathogenic role in lupus nephritis (19).

For SNP rs172378, the allele A (major allele in Caucasians and minor in African-Americans) is also reported to be related with lower than normal levels of C1q in Caucasian SCLE patients (11) Although we do not have C1q titers in our samples, we did detect the significant difference in levels of C3 in African-Americans but with the opposite direction. The mean normalized titer of C3 in African-Americans for AA homozygotes was 0.33 (SD=1.06) in comparison to GG homozygotes: −0.17 (SD=0.94), and the p value obtained by t-test was p=0.007. For heterozygotes, a p=0.01 was observed (Mean=−0.09, SD=1.06). This observed effect with C3 complement could be very likely secondary to kidney nephritis in which we detected a similar difference in a case only analysis. In other clinical reports, it has been reported that the G allele of this SNP (rs172378) is associated with shorter remissions to rituximab therapy in patients with folicular lymphoma and is also associated with systemic metastasis in patients with breast cancer (20,21). This might be consistent biologically with our results in case only analyses in which the G allele of this SNP (rs172378) was associated with more severe disease and kidney nephritis in African-Americans and Hispanics. Furthermore, the co-occurrence of the European major allele A with rare coding mutations in C1q (17) could be due to linkage disequilibrium and other unknown factors. In overall, our data as well as others suggest that the both alleles (A and G) of SNP rs172378 have important roles in different aspects of immune mediated diseases such as SLE.

In summary, while we were not able to find association between SNPs evaluated in the C1q gene and SLE, there was evidence of association in particular subsets of lupus patients. Further studies with higher SNP densities in this region and other complement components are necessary to elucidate the complex genetics and phenotypic interactions.

Materials and Methods

Recruitment and Biological Sample Collection

The present study included 2214 participants (1235 SLE cases and 979 controls) enrolled in the Lupus Genetics Studies at the OMRF as described previously (22) and from additional collaborators (23,24). The demographics, numbers of samples and frequency of 11 ACR criteria are provided in Table 1a and 1b. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each respective institution. All patients met four of the 11 the revised 1997 ACR criteria for the classification of SLE (25). Ethnicity was self-reported and verified by principal component analysis. Blood samples were collected from each participant, and genomic DNA was isolated and stored using standard methods. The complement C3 or C4 titers that have been used were based on the minimum available titer, reported in medical records from 905 subjects. These titers subsequently have been transformed to standard normal variates using the mean and variances of all labs with shared normal ranges. CH50 titers were available on 1198 subjects and were based on the single measurement at the time of patients’ participation into the Lupus Family Registry and Repository.

Table 1.

| Table 1a: Demographic distribution of independent lupus cases and controls. | ||

|---|---|---|

| African-American N=1448 | Hispanic N=766 | |

| Case/Control | 678/770 | 557/209 |

| Gender F/M | 623♀-55♂/520♀-250♂ | 494♀-63♂/167♀-42♂ |

| Mean age of SLE Onset | 35.7 (95% CI 34.77–36.72) | 31.6 (95% CI 30.15–33.06) |

| Multiplex/Simplex families* | 189/489 | 133/424 |

| Median number of ACR Criteria | 5 | 5 |

| Table 1b: The frequency of 11 ACR criteria in African-American and Hispanic population. | ||

|---|---|---|

| ACR Criteria | African-American(Frequency%)* | Hispanic (Frequency%)* |

| Malar Rash | 45 | 62 |

| Discoid | 20 | 7 |

| Photosensitivity | 43 | 64 |

| Oral Ulcer | 32 | 46 |

| Arthritis | 88 | 92 |

| Serositis | 57 | 45 |

| Nephritis | 46 | 56 |

| Neurologic | 16 | 14 |

| Hematologic | 82 | 72 |

| Immunologic | 89 | 87 |

| ANA | 99 | 98 |

From each family only one SLE cases has been selected.

The frequency of ACR Criteria in available samples of 678 African-American and 263 Hispanic cases.

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed using Illumina iSelect™ Infinium II Assays on the BeadStation™ 500GX system (Illumina, San Diego, CA) at the Lupus Genetics Studies unit of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation and at the University of Texas Southwestern DNA Microarray Core facility. Genotype data were only used from samples with a call rate greater than 90% of the SNPs screened (98.05% of the samples). The average call rate for all samples was 97.18%. For analysis, only genotype data from SNPs with a call frequency greater than 90% in the samples tested and an Illumina GenTrain score greater than 0.6 were used. GenTrain scores measure the reliability of SNP detection based on the distribution of genotypic classes. In order to minimize sample misidentification, data from 91 SNPs that had been previously genotyped on 42.12% of the samples were used to verify sample identity. In addition, at least one sample previously genotyped was randomly placed on each Illumina Infinium BeadChip and used to track samples throughout the genotyping process.

Statistical Analyses

Testing for association was completed using PLINK (26). For each SNP, missing data proportions for cases and controls, minor allele frequency and exact tests for departures from Hardy-Weinberg expectations were calculated. Haploview version 4.0 (27) was used to estimate the linkage disequilibrium (LD) between markers and haplotype structures in the different racial groups and haplotype analysis. Conditional haplotype analyses were conducted using WHAP program version 2.09. To correct for multiple testing, false discovery rate (FDR) methods were used and Q values were calculated using PLINK (26). Q values correspond to the proportion of false positives among the results. Thus, Q values less than 0.05 signify less than 5% of false positives and is taken as a measure of significance. In the case only analyses, permutation p values are also reported after 10000 random permutations using Haploview program (27). To estimate the power of study for the subgroups, we used the genetic power calculator (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/gpc/). We assumed that the high-risk allele frequency is equal to that of the marker allele and both were defined to be 0.5. At this allele frequency the additive, dominant and recessive mode of inheritance have equal power and it is therefore a conservative estimate. We assumed a disease prevalence of 1 in 10,000, an odds ratio for heterozygotes of 1.5 and an odds ratio for individuals homozygous for the risk allele of 2.0. We also assumed a D′ of 0.9 (~ r2=0.8). Finally, we assumed a type I error rate of 0.05 (reasonable given results from previous studies and the biologically motivated hypotheses) and that we would conduct a 1 degree of freedom test for allelic association.

Stratification Analyses

To account for potential confounding due to population substructure or admixture in these samples, principal component analyses (PCA) were performed (28) using all SNPs (numbering 20,506 genotyped on these subjects as part of a large effort to determine the genetic susceptibility in SLE), exception were those SNPs within the HLA region and other known associations identified via genome scan (29). The eigenvalues and eigenvectors were computed and the scree plot and the Tracy-Widom statistic were used to determine the number of principal components (PC) to adjust for during the analysis. Four principal components were identified that explained a total of ~60% of the observed genetic variation. The PCA scores were used to identify individuals that were genetically distant from the other samples and prone to introducing admixture bias. One-hundred thirty-seven African-American samples and 92 Hispanic samples were consequently removed from the analysis. After removing these genetic outliers, duplicates and related individuals, genomic control analysis was performed to calculate the inflation factor λ (Lambda) using all SNPs minus HLA region and previously identified genes (18,446 SNPs, 92% of original SNPs), which produced a λ=1.03 in Hispanics and λ=1.08 in African-Americans. Inflation factor is a measure that quantifies the degree to which population stratification increases the χ2 test statistic. Only the Hispanic sample required PCA as covariates in the logistic regression model to remove the final source of confounding via admixture to obtain the above inflation factor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (AR42460, RR015577, AI31584, AR12253, AR48940, DE015223, AR053483, RR020143, AI062629, AI24717, AR62277 and AI50026, the Mary Kirkland Scholarship, the Alliance for Lupus Research and the US Department of Veterans Affairs. We thank the participants, who agreed to take part in this study by donating samples to the various collections, in particular the Lupus Family Registry and Repository (LFRR: http://lupus.omrf.org).

References

- 1.Hauptmann G, Grosshans E, Heid E. Lupus erythematosus syndrome and complete deficiency of the fourth component of complement. Boll Ist Sieroter Milan. 1974;53(1):228. suppl. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickering MC, Botto M, Taylor PR, Lachmann PJ, Walport MJ. Systemic lupus erythematosus, complement deficiency, and apoptosis. Adv Immunol. 2000;76:227–324. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)76021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannema AJ, Kluin-Nelemans JC, Hack CE, Eerenberg-Belmer AJ, Mallee C, van Helden HP. SLE like syndrome and functional deficiency of C1q in members of a large family. Clin Exp Immunol. 1984 Jan;55(1):106–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll MC. The complement system in B cell regulation. Mol Immunol. 2004 Jun;41(2–3):141–6. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bird P, Lachmann PJ. The regulation of IgG subclass production in man: low serum IgG4 in inherited deficiencies of the classical pathway of C3 activation. Eur J Immunol. 1988 Aug;18(8):1217–22. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glass D, Raum D, Gibson D, Stillman JS, Schur PH. Inherited deficiency of the second component of complement. Rheumatic disease associations. J Clin Invest. 1976 Oct;58(4):853–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI108538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lachmann PJ. Genetic deficiencies of the complement system. Boll Ist Sieroter Milan. 1974;53(1):195–207. suppl. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brai M, Accardo P, Bellavia D. Polymorphism of the complement components in human pathology. Ann Ital Med Int. 1994;3:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walport MJ, Davies KA, Botto M. C1q and systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunobiology. 1998 Aug;199(2):265–85. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(98)80032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petry F, Hauptmann G, Goetz J, Grosshans E, Loos M. Molecular basis of a new type of C1q-deficiency associated with a non-functional low molecular weight (LMW) C1q: parallels and differences to other known genetic C1q-defects. Immunopharmacology. 1997 Dec;38(1–2):189–201. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(97)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Racila DM, Sontheimer CJ, Sheffield A, Wisnieski JJ, Racila E, Sontheimer RD. Homozygous single nucleotide polymorphism of the complement C1QA gene is associated with decreased levels of C1q in patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2003;12(2):124–32. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu329oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sellar GC, Blake DJ, Reid KB. Characterization and organization of the genes encoding the A-, B-, and C-chains of human complement subcomponent C1q: the complete derived amino acid sequence of human C1q. Biochem J. 1991;274:481–490. doi: 10.1042/bj2740481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vila LM, Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Bastian HM, Fessler BJ, Reveille JD, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US cohort, XXXVII: association of lymphopenia with clinical manifestations, serologic abnormalities, disease activity, and damage accrual. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;5:799–806. doi: 10.1002/art.22224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman IE, Peene I, Meheus L, Huizinga TW, Cebecauer L, Isenberg D, et al. Specific antinuclear antibodies are associated with clinical features in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;9:1155–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.013417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chew CH, Chua KH, Lian LH, Puah SM, Tan SY. PCR-RFLP genotyping of C1q mutations and single nucleotide polymorphisms in Malaysian patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Biol. 2008 Feb;80(1):83–93. doi: 10.3378/1534-6617(2008)80[83:PGOCMA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martens HA, Zuurman MW, de Lange AH, Nolte IM, van der Steege G, et al. Analysis of C1q polymorphisms suggests association with SLE, serum C1q and CH50 levels and disease severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 May 26; doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.085688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petry F, Loos M. Common silent mutations in all types of hereditary complement C1q deficiencies. Immunogenetics. 2005 Sep;57(8):566–71. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0023-z. Epub 2005 Sep 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miura-Shimura Y, Nakamura K, Ohtsuji M, Tomita H, Jiang Y, Abe M, et al. C1q regulatory region polymorphism down-regulating murine c1q protein levels with linkage to lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 2002;169(3):1334–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marto N, Bertolaccini ML, Calabuig E, Hughes GR, Khamashta MA. Anti-C1q antibodies in nephritis: correlation between titers and renal disease activity and positive predictive value in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005 Mar;64(3):444–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.024943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Racila E, Link BK, Weng WK, Witzig TE, Ansell S, Maurer MJ, et al. A polymorphism in the complement component C1qA correlates with prolonged response following rituximab therapy of follicular lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Oct 15;14(20):6697–703. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Racila E, Racila DM, Ritchie JM, Taylor C, Dahle C, Weiner GJ. The pattern of clinical breast cancer metastasis correlates with a single nucleotide polymorphism in the C1qA component of complement. Immunogenetics. 2006 Feb;1:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0077-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman KM, Kelly JA, Herring BJ, Adler AJ, Glenn SB, Namjou B, et al. Evaluation of the genetic association of the PTPN22 R620W polymorphism in familial and sporadic systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2533–2540. doi: 10.1002/art.21963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacob CO, Reiff A, Armstrong DL, Myones BL, Silverman E, Klein-Gitelman M, et al. Identification of novel susceptibility genes in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus using a uniquely designed candidate gene pathway platform. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:4164–73. doi: 10.1002/art.23060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper GS, Parks CG, Treadwell EL, St Clair EW, Gilkeson GS, Cohen PL, et al. Differences by race, sex and age in the clinical and immunologic features of recently diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus patients in the southeastern United States. Lupus. 2002;3:161–7. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu161oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harley JB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, Jacob CO, Kimberly RP, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet. 2008;2:204–10. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]