Abstract

Vitamin E supplementation has been suggested to improve immune response in the aged in part by altering cytokine production. However, there is not a consensus regarding the effect of supplemental vitamin E on cytokine production in humans. There is evidence that baseline immune health can affect immune response to supplemental vitamin E in the elderly. Thus, the effect of vitamin E on cytokines may depend on their pre-supplementation cytokine response. Using data from a vitamin E intervention in elderly nursing home residents, we examined if the effect of vitamin E on ex vivo cytokine production of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ depended on baseline cytokine production. . We observed that the effect of vitamin E supplementation on cytokine production depended on pre-supplementation production of the respective cytokines. The interactions between vitamin E and baseline cytokine production were not explained covariates known to impact cytokine production. Our results offer evidence that baseline cytokine production should be considered in studies that examine the effect of supplemental vitamin E on immune and inflammatory responses. Our results could have implications in designing clinical trials to determine the impact of vitamin E on conditions in which cytokines are implicated such as infections and atherosclerotic disease.

Keywords: Vitamin E, elderly, cytokine production

1. Introduction

Cytokines are critical regulators of immune response and inflammation. Cytokine production, particularly in response to exogenous stimuli, is altered in the aged [2, 4, 6, 15, 17, 23, 28]. Studies have shown that supplemental vitamin E can improve immune response in the aged and this effect is in part mediated via its impact on cytokine production [1, 7, 8, 12, 18]. Animal studies have shown that supplemental vitamin E improves production following infection with influenza viruses [11] and LP-BM5 [30, 31]. However, previous studies of the effect of vitamin E on cytokine production in humans have yielded discrepant results [5, 7, 8, 22, 24, 29, 34], and our recent analysis of data from a one-year vitamin E supplementation trial in the elderly suggested that vitamin E did not have an overall effect on IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 or IFN-γ production (Belisle et al unpublished data).

Further, previous studies with vitamin E in humans have noted variability in immune improvement among individuals [18]. There is some evidence that baseline immune health can affect immune response to supplemental vitamin E in the elderly [24]. Thus, it is possible that the effect of vitamin E on cytokine production may depend on their pre-supplementation levels. Here, as part of exploratory analysis, we tested if the effect of supplemental vitamin E on ex vivo production of these cytokines was contingent on baseline cytokine production response.

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Study population

Between 1998 and 2001, elderly volunteers living in long-term care facilities were recruited to participate in a year-long randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled vitamin E intervention trial [21]. The Tufts Medical Center institutional review board approved the study protocol and informed consent form. Volunteers were recruited from 33 long-term care facilities in the Boston metropolitan area. Selection criterion for this study has been previously reported [21]. Participants were randomized to receive either vitamin E (200 IU DL-α-tocopherol/day) or placebo. In addition, all subjects received a daily multivitamin and mineral capsule containing one half the RDA of essential vitamins and minerals, including 4 IU of vitamin E.

Of the 617 volunteers enrolled in the study, 451 completed the study. Ex vivo production of cytokines was measured in 110 subjects who were enrolled during the second year of the parent study.

2.2. Nutrient status and blood count differentials

Fasting blood samples collected from participants at enrollment and completion of the study was used to measure clinical chemistries, blood cell differentials, and plasma nutrient status for select nutrients including vitamin E [3, 19, 20]. Complete blood count was obtained using a hematological analyzer (model Baker 9000; Serono-Baker Instrument, Inc., Allentown, PA), and the white cell differential was assessed using microscopic examination of blood smears following Wright-Giemsa staining.

2.3. Ex vivo cytokine production

Secreted ex vivo cytokine production was assessed from heparinized whole blood collected from subjects following an overnight fast. To account for day to day variation, cytokine production was measured in blood samples collected on two separate days each at enrollment and at completion of the intervention. The mean of the two days at each phase was used in data analysis.

Whole blood was diluted in complete RPMI at a ¼ ratio and aliquoted to 24 well flat-bottom plates. Concavalin A (ConA; 40 µg/mL)- or phytohemagluttinan (PHA; 20 µg/mL)-stimulated IFN-γ was determined following 48 hours of incubation. IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α production in response to lipopolysacchride (LPS) (1.0 µg/mL) was determined following 24 hours of incubation. Following incubation, plates were centrifuged and supernatants were collected and stored (−70°C) for analysis. Secreted cytokine protein levels were measures by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). IFN-γ and TNF-α proteins were detected using mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies (MAb) and biotinylated mouse anti-human antibodies (Ab) specific for IFN-γ, and TNF-α, respectively (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). IL-6 was detected using rat anti-human IL-6 MAb and biotinylated rat anti-human IL-6 (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). IL-1β was detected using mouse anti-human IL-1β MAb and biotinylated anti-human IL-1β Ab (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

The number of monocytes and lymphocytes in whole blood can impact the amount of cytokines produced. All results reported here are for cytokine production per monocytes and lymphocytes, which were calculated by dividing cytokine levels by the sum of the number of monocytes and lymphocytes in blood samples taken concurrently for each individual and are expressed as pg/ monocyte and lymphocyte × 106.

2.4. DNA isolation and genotyping

Among those participants selected for ex vivo immunological measures, 100 participants consented to DNA analysis. DNA was isolated from blood samples using spin-prep kits according to manufacturer’s instructions (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, QIAGEN Inc, Valencia, CA). The following locations are investigated this article: IFN-γ 874A>T (rs2430561), IL-1β -1473G>C rs1143623), IL-1β -511G>A (rs16944), IL-1β 3954C>T (rs1143634), IL-1β 6054G>A (rs1143643), IL-6 -174C>G (rs1800795), and TNF-α -308G>A (rs1800629). These SNPs were selected from among numerous other SNPs based on previous reports that they were associated with altered cytokine production in younger populations or in vitro [10, 13, 14, 16, 25–27, 32, 33]. Genotyping was performed with Taqman 5’ nuclease allelic discrimination (Assay by Design/Demand, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). SNPs were determined using Validated ABI Assays with the exception of IFN-γ 874A>T which was determined using primer and probe sequences described by Yu et al [35]. The primers and probes used for genotyping are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of SNPs, primers and probes

| Gene | SNP | dsSNP ID | Gene position | Primers and Probes or ABI Assay by Demand ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | 874 A>T | rs2430561 | Intron 2 | Forward: ACATTCCACAATTGATTTTATTCTTACAACA |

| Reverse: ACGAGCTTTAAAAGATAGTTCCAAACA | ||||

| Probe: AAATCAAATC[A/T]CACACACACAC | ||||

| IL-1β | −511 G>A | rs16944 | 5’-flanking | Forward: GAGGCTCCTGCAATTGACAGA |

| Reverse : AGGGTGTGGGTCTCTACCTT | ||||

| Probe: CTGTTCTCTGCCTC[G/A]GGA | ||||

| IL-1β | 3954 C>T | rs1143634 | Exon 5 | Forward: ACCTAAACAACATGTGCTCCACA |

| Reverse: ATCGTGCACATAAGCCTCGTTA | ||||

| Probe: CATGTGTC[G/A]AAGAAGA | ||||

| IL-1β | −1473 G>C | rs1143623 | 5’-flanking | ABI Assay by Demand ID: C_1839941 |

| IL-1β | 6054 G>A | rs1143643 | Intron 6 | Forward: GAGCCAGACTCCTGAGTTGTAACTG |

| Reverse: CCTCAGCATTTGGCACTAAGTTTTA | ||||

| Probe: CACAC[G/A]GAAAGTT | ||||

| IL-6 | −174 C>G | rs1800795 | 5’-flanking | Forward: GACGACCTA AGCTGCACTTTTC |

| Reverse: GGGCTGATTGG AAACCTTATTA AGATTG | ||||

| Probe: CTTTAGCAT[G/C]GCAAGAC | ||||

| TNF-α | −308 G>A | rs1800629 | 5’-flanking | ABI Assay by Demand ID: C__7514879_10 |

2.5. Statistical analysis

SNPs were tested for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using Utility Programs for Analysis of Genetic Linkage (J Ott, 1988–2007). The remaining analysis was performing using SAS statistical software (SAS v9.1.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The distribution of continuous variables was examined and transformed using a logarithmic or square-root transformation as needed. Descriptive statistics are reported as non-transformed data. Baseline characteristics of each treatment group were compared by using Student’s t-test for independent samples for continuous variables or Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact Test for categorical variables.

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to evaluate the interaction between baseline cytokine production and vitamin E treatment. ANCOVA was also used to adjust for potential confounding variables. Models were adjusted for the following factors: 1) baseline participant characteristics that have been linked to altered cytokine production (current smoking, diabetes mellitus, dementia, albumin level, hemoglobin level, obstructive lung diseases, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, history of malignancy and age); 2) c-reactive protein levels (CRP) levels which can be indicative of acute inflammatory response and these cytokines are increased with acute infections; 3) circulating levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, vitamin E, and zinc as these nutrients can alter immune function.

Common SNPs at the genes coding for these cytokines have been associated with cytokine production. Therefore, appropriate SNPs were added to the interaction models as follows: 1) Models that included the interaction between vitamin E and baseline IFN-γ production were adjusted for IFN-γ 874A>T. 2) Models that included the interaction between vitamin E and baseline TNF-α production were adjusted for TNF-α -308G>A. 3) Models that included the interaction between vitamin E and baseline IL-6 were adjusted for IL-6 -174G>C. 4) Models that included the interaction between vitamin E and baseline IL-1β were adjusted for IL-1β-1473G>C, IL-1β -511G>A , IL-1β 3954C>T , and IL-1β 6054G>A. Subjects missing cytokine production data at either baseline or follow up were excluded from the analysis of that particular cytokine. Statistical significance was determined at P values less than 0.05 using two-sided significance tests. Because these analyses were considered hypothesis-generating, we did not adjust P values for the number of comparisons performed.

3. Results

3.1. Population characteristics

The study population characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The participants were largely non-Hispanic Whites (95%), age ranged from 66 to 100 years old, and there were slightly more women (56%) than men. The frequency of participants with a history of malignancy was statistically significantly higher in the placebo group compared to the vitamin E treatment group (P=0.04) but there was no statistically significant differences in cytokine production between those with and without a history of malignancy. There were no other statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics between the treatment groups. Genotype frequencies of the SNPs examined did not deviate from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) within treatment groups (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics by treatment group

| Treatment group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin E (n=47) | Placebo (n=63) | |

| Age, years, mean (range) | 83 (68 – 100) | 83.3 (66 – 97) |

| Women, No. (%) | 28 (60) | 34 (54) |

| White, No. (%) | 45 (96) | 60 (95) |

| Body mass index (BMI), mean (SD) | 25.92 (5.21) | 25.83 (5.83) |

| Serum albumin, g/dL, mean (SD) | 3.77 (0.30) | 3.79 (0.34) |

| Hemoglobulin, g/dL, mean (SD) | 12.67 (1.42) | 12.48 (1.38) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L, mean (SD) | 8.73 (8.83) | 7.44 (13.77) |

| Plasma vitamin E, µg/dL, mean (SD) | 1283 (398) | 1203 (517) |

| Total no. medications, mean (SD) | 7.49 (3.39) | 7.73 (3.50) |

| Participants using NSAIDS, No. (%) | 23 (49) | 28 (44) |

| Medical History | ||

| Coronary artery disease, No. (%) | 15 (32) | 12 (19) |

| Congestive heart failure, No. (%) | 8 (17) | 9 (14) |

| Diabetes mellitus, No. (%) | 8 (17) | 13 (21) |

| Dementia | ||

| Alzheimer’s Disease (A), No. (%) | 5 (11) | 2 (3) |

| Non-Alzheimers Dementia (NA), No. (%) | 19 (40) | 17 (27) |

| COPD, No. (%) | 13 (28) | 15 (24) |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 26 (55) | 35 (56) |

| Current smoker, No. (%) | 4 (9) | 6 (10) |

| Malignancy, No. (%)* | 1 (2) | 9 (14) |

Significant difference in frequency between treatment groups by Fisher's exact test (p<0.05).

No., number; NSAIDS, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 3.

Genotype frequencies

| Major allele | Minor allele | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Treatment | homozygotes | Heterozygotes | homozyogtes | HWE (P) |

| IL-6 -174C>G | Vitamin E | 20 | 18 | 4 | 0 (0.98) |

| Placebo | 23 | 24 | 11 | 1.06 (0.30) | |

| TNF-α -308G>A | Vitamin E | 25 | 13 | 4 | 1.28 (0.25) |

| Placebo | 48 | 8 | 2 | 3.81 (0.051) | |

| IL-1β -1473G>C | Vitamin E | 24 | 15 | 2 | 0.03 (0.86) |

| Placebo | 35 | 23 | 3.55 (0.06) | ||

| IL-1β -511G>A | Vitamin E | 17 | 22 | 2 | 2.34 (0.125) |

| Placebo | 28 | 26 | 4 | 0.38 (0.53) | |

| IL-1β 3954C>T | Vitamin E | 25 | 14 | 2 | 0 (0.98) |

| Placebo | 38 | 19 | 1 | 0.64 (0.42) | |

| IL-1β 6054G>A | Vitamin E | 15 | 21 | 5 | 0.33 (0.56) |

| Placebo | 22 | 23 | 13 | 2.04 (0.15) | |

| IFN-γ 874A>T | Vitamin E | 9 | 18 | 15 | 0.66 (0.42) |

| Placebo | 15 | 22 | 19 | 2.47(0.11) | |

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium=HWE.

3.2. Effect of vitamin E treatment on cytokine production

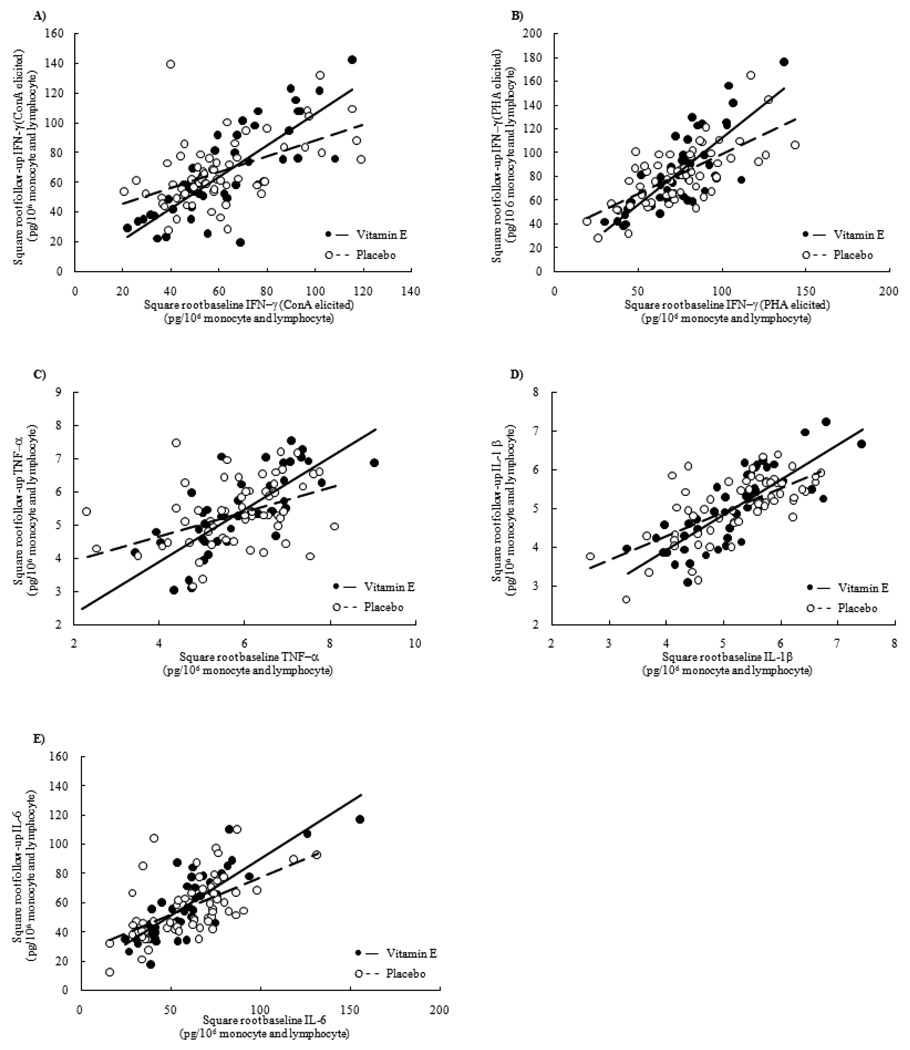

We tested for a statistical interaction between baseline cytokine production and vitamin E treatment on follow-up cytokine production. We observed a statistically significant interaction between vitamin E treatment and baseline cytokine production for follow-up production of IFN-γ (P=0.002 for ConA elicitation; P=0.005 for PHA elicitation), TNF-α (P=0.009), IL-1β (P=0.053) and IL-6 (P=0.031) (Figure 1). The nature of the interaction was similar for each cytokine. The regression lines crossed with the intersection occurring mid-way. The data were plotted to identify potential influential outliers. When graphs were compared, it was observed that the interactions were not driven by outliers.

Figure 1.

The effect of vitamin E supplementation on cytokine production depends on baseline cytokine production. Cytokine production was measured from whole blood at the beginning and end of a one year vitamin E supplementation in the elderly. TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 was measured from whole blood elicited for 24 hours with lipopolysacchride (LPS; 1.0 µg/mL). IFN-γ was measured from whole blood elicited for 48 hours with phytohemagluttinin (PHA; 20 µg/mL) or concalavinA (ConA; 40 µg/mL). Cytokines production was corrected for the number of monocytes and lymphocytes in the blood (pg/ 106 lymphocyte and monocyte). P values (P) for the interaction are unadjusted.

A) The interaction between vitamin E treatment and baseline IFN-γ production elicited with ConA (P=0.002).

B) The interaction between vitamin E treatment and baseline IFN-γ production elicited with PHA (P=0.005).

C) The interaction between vitamin E treatment and baseline TNF-α (P=0.009.

D) The interaction between vitamin E treatment and baseline IL-1β (P=0.053).

E) The interaction between vitamin E treatment and baseline and IL-6 production (P=0.031).

We then examined if these interactions were independent of confounding factors known to affect immune function. Separate models included: 1) baseline participant characteristics linked to altered cytokine production, 2) circulating CRP levels, 3) circulating levels of vitamin E, zinc, cholesterol and triglycerides, and 4) common SNPs at the genes coding for these cytokines. We observed that including these covariates in models of follow-up cytokine production did not change the statistical significance of the interactions for IFN-γ or TNF-α. However, the interactions for IL-1β and IL-6 were no longer statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have suggested that vitamin E can modulate cytokine production in the elderly; however, studies examining IFN-γ [24] in particular, are sparse, and the results reported for others are discrepant [5, 7, 8, 22, 29, 34]. While investigating the effect of vitamin E treatment on cytokine production, we uncovered an interaction between vitamin E treatment and baseline production for follow-up IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 production that, to our knowledge, has not been reported previously. We observed that the effect of vitamin E treatment on IFN-γ, TNF-α , IL-1β and IL-6 production was contingent on the baseline production of each of these cytokines, although this interaction was most robust for IFN-γ and TNF-α.

Analyses were performed with adjustment for potential confounding variables, including genetic factors, to test if the interactions were independent of other factors that might affect cytokine production. Our observations suggest that these interactions were not due to differences in baseline cytokine production between the treatment groups, nutrient status, common SNPs, gender or other covariates. Although the statistical significance of the interaction become borderline significant for IL-1β and IL-6 when adjusting for some of these covariates, it is possible this was due to the analysis being slightly statistically underpowered with the inclusion of the covariates.

It is plausible that these interactions reflect an inherent difference between individuals who produce lower amounts of cytokines at baseline and those who produce more. Treatment with vitamin E may accentuate this inherent difference. Although the interaction remained statistically significant when adjusted for factors known to affect cytokine production, it is possible that other unmeasured factors could account for these interactions.

The interaction between baseline cytokine production and vitamin E treatment may indicate that vitamin E maintains the relationship between baseline and follow-up IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α cytokine response in the elderly. When follow-up production was regressed on baseline production by treatment group, the slope of the regression line for the vitamin E treatment group was stronger than the placebo treated group in each case. For each cytokine, the regression lines for placebo and vitamin E treated groups intersected at approximately the mean production level.

The public health implications of our observations need to be determined. Cytokines play important roles in protecting the body against infections, and age-related alterations in cytokines have been implicated in impaired response to influenza infection and vaccination [2, 6, 15, 23]. For example, underlying infections are common in the aged and may not be readily apparent in most instances. Recent studies have indicated that persistent sub-clinical viral infections may render immune cells less able to produce IFN-γ [9]. The nature of the interaction we observed suggests a stronger relationship between baseline and follow-up within the vitamin E group. This could indicate a stabilization of cytokine production within the vitamin E treated group. A stabilization of IFN-γ response with vitamin E treatment could benefit those with persistent sub-clinical infection.

However, our data also suggest that vitamin E supplementation does not have the same effect on cytokine production in all elderly people. In the context of vaccination and infection, it could be argued that elevated cytokine production is considered beneficial. Therefore, supplemental vitamin E might be beneficial to those with higher initial cytokine levels, while adversely effecting those with low initial production of these cytokines. If supplemental vitamin E suppresses IFN-γ or TNF-α production in response to vaccination or pathogens of the respiratory tract among those with low baseline production, it could render that population more susceptible to infection. Conversely, those with higher baseline IFN-γ or TNF-α production treated with vitamin E could have a higher vaccine response and lower infection susceptibility compared to individuals who did not receive 200 IU of vitamin E daily. Future studies powered to detect differences in vaccine response and infection risk between vitamin E versus placebo treatment in ranges of baseline cytokine production found in our study population are necessary to determine the public health implications of our observations.

The interaction between vitamin E treatment and baseline cytokine production explains why we previously (Belisle et al unpublished data) observed no overall difference in average cytokine production between treatment groups at follow-up. Further, it may partly explain discrepant results reported in the literature for the effect of vitamin E on these cytokines [5, 7, 8, 22, 24, 29, 34], as these studies did not examine the interaction between baseline cytokine production and vitamin E treatment.

There are several limitations to this report that merit comment. First, this analysis was not planned and accounted for in the sample size calculations that preceded the collection of data. The P values reported were not adjusted for the number of statistical tests performed. Therefore, the observations should be considered hypothesis generating. The observation that a similar interaction is present for different cytokines within this population suggests that the interaction observed here is not merely due to chance. Second, our study examined a limited, and by no means exhaustive, number of loci and SNPs. The SNPs selected for this study were chosen from among many genetic variants based on published literature showing association with cytokine production, and their potential to impact respiratory infection susceptibility. It is possible that alternate intrinsic factors, including SNPs at other locations, could account for this interaction. However, we did not take a more comprehensive approach given the limitations of our sample size to address more multiple comparisons and complex interactions. Third, the mechanism driving the observed interaction is not known. The observation that the relationship between baseline and vitamin E treatment was similar for each of these cytokines may reflect an underlying biological effect of vitamin E that common to each of these cytokines. For example, the effect of vitamin E might be mediated through a particular subset of immune cells or a common signaling pathway.

In conclusion, we observed that cytokine response to vitamin E supplementation may depend on individual’s immune response at the onset of supplementation. Although similar patterns were observed for multiple cytokines, we observed that this relationship was particularly strong for IFN-γ and TNF-α. These interactions may partly explain variation in individual response to vitamin E supplementation and could have significant public health implications. Future studies should focus on validating these observations in larger populations, investigating the biological mechanisms underlying these interactions, and determining the public health implications of the findings. If these observations can be verified, they suggest that baseline immune response should be considered in human studies that examine the effect of vitamin E on immune response in the aged, and have potential consequences for determining who may benefit the most from the consumption of supplemental vitamin E.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the staff of the Metabolic Research Unit and Nutritional Evaluation Laboratory of Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University and the participating nursing homes for help in recruitment of subjects and analysis of blood micronutrients. This research was funded by a National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institutes of Health grant 5R01-AG013975, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) agreement 51000-058-00D, a grant for the preparation of study capsules from Hoffman LaRoche Inc., and a DSM Nutritional Products, Inc. scholarship. The study was also supported by HRCA/Harvard Research Nursing Home PO1 AG004390 to Dr. Lipsitz, which facilitated recruitment of subjects and conduct of the study at Hebrew Rehabilitation Center. CIBER Fisiopatologia de la Obesidad y Nutricion is an initiative of ISCIII, government of Spain.

Abbreviations

- LPS

lipopolysacchride

- Conc

concentration

- SD

standard deviation

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- Abs

antibodies

- MAb

monoclonal antibodies

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: S.N.M. has funding in this area of study from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute on Aging (NIA), and Roche (for provision of the supplements for the study). There are no other known conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Adolfsson O, Huber BT, Meydani SN. Vitamin E-enhanced IL-2 production in old mice: naive but not memory T cells show increased cell division cycling and IL-2-producing capacity. J Immunol. 2001;167:3809–3817. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein ED, Gardner EM, Abrutyn E, Gross P, Murasko DM. Cytokine production after influenza vaccination in a healthy elderly population. Vaccine. 1998;16:1722–1731. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bieri JG, Tolliver TJ, Catignani GL. Simultaneous determination of alpha-tocopherol and retinol in plasma or red cells by high pressure liquid chromatography. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32:2143–2149. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.10.2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Born J, Uthgenannt D, Dodt C, Nunninghoff D, Ringvolt E, Wagner T, Fehm HL. Cytokine production and lymphocyte subpopulations in aged humans. An assessment during nocturnal sleep. Mech Ageing Dev. 1995;84:113–126. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(95)01638-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon JG, Orencole SF, Fielding RA, Meydani M, Meydani SN, Fiatarone MA, Blumberg JB, Evans WJ. Acute phase response in exercise: interaction of age and vitamin E on neutrophils and muscle enzyme release. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:R1214–R1219. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.6.R1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng Y, Jing Y, Campbell AE, Gravenstein S. Age-related impaired type 1 T cell responses to influenza: reduced activation ex vivo, decreased expansion in CTL culture in vitro, and blunted response to influenza vaccination in vivo in the elderly. J Immunol. 2004;172:3437–3446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devaraj S, Li D, Jialal I. The effects of alpha tocopherol supplementation on monocyte function. Decreased lipid oxidation, interleukin 1 beta secretion, and monocyte adhesion to endothelium. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:756–763. doi: 10.1172/JCI118848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devaraj S, Jialal I. Alpha-tocopherol decreases tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA and protein from activated human monocytes by inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1212–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadrup SR, Strindhall J, Kollgaard T, Seremet T, Johansson B, Pawelec G, thor Straten P, Wikby A. Longitudinal studies of clonally expanded CD8 T cells reveal a repertoire shrinkage predicting mortality and an increased number of dysfunctional cytomegalovirus-specific T cells in the very elderly. J Immunol. 2006;176:2645–2653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall SK, Perregaux DG, Gabel CA, Woodworth T, Durham LK, Huizinga TW, Breedveld FC, Seymour AB. Correlation of polymorphic variation in the promoter region of the interleukin-1 beta gene with secretion of interleukin-1 beta protein. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1976–1983. doi: 10.1002/art.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han SN, Wu D, Ha WK, Beharka A, Smith DE, Bender BS, Meydani SN. Vitamin E supplementation increases T helper 1 cytokine production in old mice infected with influenza virus. Immunology. 2000;100:487–493. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han SN, Adolfsson O, Lee CK, Prolla TA, Ordovas J, Meydani SN. Age and vitamin E-induced changes in gene expression profiles of T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:6052–6061. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez-Guerrero C, Monzon-Bordonaba F, Jimenez-Zamudio L, Ahued-Ahued R, Arechavaleta-Velasco F, Strauss JF, 3rd, Vadillo-Ortega F. In-vitro secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by human amniochorion carrying hyper-responsive gene polymorphisms of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:625–629. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann SC, Stanley EM, Darrin Cox E, Craighead N, DiMercurio BS, Koziol DE, Harlan DM, Kirk AD, Blair PJ. Association of cytokine polymorphic inheritance and in vitro cytokine production in anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes. Transplantation. 2001;72:1444–1450. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200110270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Looney RJ, Falsey AR, Walsh E, Campbell D. Effect of aging on cytokine production in response to respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:682–685. doi: 10.1086/339008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louis E, Franchimont D, Piron A, Gevaert Y, Schaaf-Lafontaine N, Roland S, Mahieu P, Malaise M, De Groote D, Louis R, Belaiche J. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) gene polymorphism influences TNF-alpha production in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated whole blood cell culture in healthy humans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:401–406. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNerlan SE, Rea IM, Alexander HD. A whole blood method for measurement of intracellular TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma and IL-2 expression in stimulated CD3+ lymphocytes: differences between young and elderly subjects. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:227–234. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meydani SN, Barklund MP, Liu S, Meydani M, Miller RA, Cannon JG, Morrow FD, Rocklin R, Blumberg JB. Vitamin E supplementation enhances cell-mediated immunity in healthy elderly subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:557–563. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meydani SN, Meydani M, Rall LC, Morrow F, Blumberg JB. Assessment of the safety of high-dose, short-term supplementation with vitamin E in healthy older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:704–709. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.5.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meydani SN, Meydani M, Blumberg JB, Leka LS, Pedrosa M, Diamond R, Schaefer EJ. Assessment of the safety of supplementation with different amounts of vitamin E in healthy older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:311–318. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meydani SN, Leka LS, Fine BC, Dallal GE, Keusch GT, Singh MF, Hamer DH. Vitamin E and respiratory tract infections in elderly nursing home residents: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004;292:828–836. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mol MJ, de Rijke YB, Demacker PN, Stalenhoef AF. Plasma levels of lipid and cholesterol oxidation products and cytokines in diabetes mellitus and cigarette smoking: effects of vitamin E treatment. Atherosclerosis. 1997;129:169–176. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(96)06022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouyang Q, Cicek G, Westendorp RG, Cools HJ, van der Klis RJ, Remarque EJ. Reduced IFN-gamma production in elderly people following in vitro stimulation with influenza vaccine and endotoxin. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;121:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pallast EG, Schouten EG, de Waart FG, Fonk HC, Doekes G, von Blomberg BM, Kok FJ. Effect of 50-and 100-mg vitamin E supplements on cellular immune function in noninstitutionalized elderly persons. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:1273–1281. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pociot F, Molvig J, Wogensen L, Worsaae H, Nerup J. A TaqI polymorphism in the human interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta) gene correlates with IL-1 beta secretion in vitro. Eur J Clin Invest. 1992;22:396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1992.tb01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pravica V, Asderakis A, Perrey C, Hajeer A, Sinnott PJ, Hutchinson IV. In vitro production of IFN-gamma correlates with CA repeat polymorphism in the human IFN-gamma gene. Eur J Immunogenet. 1999;26:1–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2370.1999.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivera-Chavez FA, Peters-Hybki DL, Barber RC, O'Keefe GE. Interleukin-6 promoter haplotypes and interleukin-6 cytokine responses. Shock. 2003;20:218–223. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000079425.52617.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandmand M, Bruunsgaard H, Kemp K, Andersen-Ranberg K, Pedersen AN, Skinhoj P, Pedersen BK. Is ageing associated with a shift in the balance between Type 1 and Type 2 cytokines in humans? Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;127:107–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Tits LJ, Demacker PN, de Graaf J, Hak-Lemmers HL, Stalenhoef AF. alpha-tocopherol supplementation decreases production of superoxide and cytokines by leukocytes ex vivo in both normolipidemic and hypertriglyceridemic individuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:458–464. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.2.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Watson RR. Vitamin E supplementation at various levels alters cytokine production by thymocytes during retrovirus infection causing murine AIDS. Thymus. 1994;22:153–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Huang DS, Wood S, Watson RR. Modulation of immune function and cytokine production by various levels of vitamin E supplementation during murine AIDS. Immunopharmacology. 1995;29:225–233. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00061-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wen AQ, Wang J, Feng K, Zhu PF, Wang ZG, Jiang JX. Effects of haplotypes in the interleukin 1beta promoter on lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin 1beta expression. Shock. 2006;26:25–30. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000223125.56888.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson AG, Symons JA, McDowell TL, McDevitt HO, Duff GW. Effects of a polymorphism in the human tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter on transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3195–3199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu JH, Ward NC, Indrawan AP, Almeida CA, Hodgson JM, Proudfoot JM, Puddey IB, Croft KD. Effects of alpha-tocopherol and mixed tocopherol supplementation on markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in type 2 diabetes. Clin Chem. 2007;53:511–519. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.076992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu H, Zhu QR, Gu SQ, Fei LE. Relationship between IFN-gamma gene polymorphism and susceptibility to intrauterine HBV infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2928–2931. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i18.2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]