Abstract

Objective

To document teaching evaluation practices in colleges and schools of pharmacy.

Methods

A 51-item questionnaire was developed based on the instrument used in a previous study with modifications made to address changes in pharmacy education. An online survey service was used to distribute the electronic questionnaire to the deans of 98 colleges and schools of pharmacy in the United States.

Results

Completed surveys were received from 89 colleges and schools of pharmacy. All colleges/schools administered student evaluations of classroom and experiential teaching. Faculty peer evaluation of classroom teaching was used by 66% of colleges/schools. Use of other evaluation methods had increased over the previous decade, including use of formalized self-appraisal of teaching, review of teaching portfolios, interviews with samples of students, and review by teaching experts. While the majority (55%) of colleges/schools administered classroom teaching evaluations at or near the conclusion of a course, 38% administered them at the midpoint and/or conclusion of a faculty member's teaching within a team-taught course. Completion of an online evaluation form was the most common method used for evaluation of classroom (54%) and experiential teaching (72%).

Conclusion

Teaching evaluation methods used in colleges and schools of pharmacy expanded from 1996 to 2007 to include more evaluation of experiential teaching, review by peers, formalized self-appraisal of teaching, review of teaching portfolios, interviews with samples of students, review by teaching experts, and evaluation by alumni. Procedures for conducting student evaluations of teaching have adapted to address changes in curriculum delivery and technology.

Keywords: teaching, evaluation, assessment, survey

INTRODUCTION

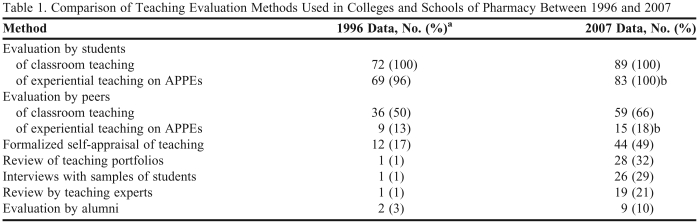

In 1998 an investigation of practices used to evaluate teaching in schools of pharmacy was conducted,1 and the results were compared to a similar study conducted 20 years previously.2 At 100% of the responding colleges and schools, students evaluated classroom teaching, and at 96% of the colleges and schools, students evaluated experiential teaching.1 At 50% of the colleges and schools, faculty peers evaluated classroom teaching, and at 13% faculty peers evaluated experiential teaching. Other evaluation methods, including self-appraisal, evaluation by alumni, portfolio review, interviewing samples of students, and review by teaching experts were rarely used.1

Since the 1998 report, 9 studies addressing various aspects of teaching evaluation have appeared in the pharmacy education literature. One study measured pharmacy student opinions at 1 school of pharmacy regarding the usefulness of the classroom teaching evaluation instrument employed. Students reported they completed the instrument in an honest fashion but were cynical about whether the instrument was associated with faculty accountability or changes.3

Three studies examined Web-based online evaluations and compared them to traditional paper evaluations. The online methodology was associated with favorable response rates4-6 more student open-ended comments than the traditional method4,6 favorable student attitudes4,5 and favorable faculty attitudes.4,6

Students at 1 college of pharmacy scored teaching performance lower in courses where lectures were delivered by interactive videoconferencing compared to scores in courses where live presentations were given.7 The authors recommended this finding be considered when assessing teaching effectiveness.

Another study documented a correlation between students' grade expectations for a course and mean evaluation scores for the course. Because of this finding, the authors questioned use of student evaluations as the main criterion used in performance reviews, teaching awards, and promotion and tenure decisions.8

Several subsequent articles provided support for the use of supplemental methods to evaluate teaching.9-11 A study compared the results of traditional student evaluations of classroom teaching with those of faculty self-evaluation and with the results of evaluations by smaller representative subsets of students at a school of pharmacy. The similarities in ratings supported continued use of these evaluation methods.9 Two other studies found instructors and assessors had positive attitudes toward and perceptions of the peer review systems at their respective schools.10,11

This article provides an update on contemporary practices used to evaluate teaching in colleges and schools of pharmacy. With regard to teaching, information was collected about (1) evaluation methods including student evaluations, peer evaluations and other methods; (2) use of evaluation results; (3) procedures used for conducting or administering evaluations; and (4) evaluation instruments.

METHODS

A 51-item questionnaire was modeled after one used in a similar study conducted 10 years previously. Updates were made to reflect changes in pharmacy education, including distance learning and other uses of technology.1 Content domain was addressed by a review of the literature to ensure the questionnaire items covered areas identified as important to teaching evaluation practices. Content validity was judged by several pharmacy educators who reviewed the survey instrument to determine whether the items adequately represented the content universe. Based upon their recommendations, some items were edited. The project was reviewed and approved by the University's Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research.

Using Survey Monkey (Surveymonkey.com Corporation, Portland, OR), a Web-based survey software program, the questionnaire was distributed electronically in 2007 to deans of 98 colleges and schools of pharmacy, regular and affiliate AACP institutional members that had a doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) class enrolled in fall 2006. Four subsequent electronic mailings were made to nonrespondents. Analyses were conducted using the same online survey software and included simple descriptive statistics. New pharmacy schools that had not yet offered advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) were excluded from analyses of items related to experiential teaching on APPEs.

RESULTS

Of the 89 (91%) responses received, 53 were from public colleges/schools and 36 from private colleges/schools. The colleges/schools that responded had been in existence a mean of 70.1 ± 50.3 years, with a median of 78.5 years and a range of 2 to 187 years. The majority of the questionnaires were completed by either an assistant or associate dean (52%) or a dean (34%). The remaining responders included chairs of assessment committees (7%), department chairs (2%), curriculum committee chairs (2%), and regular faculty members (2%).

Evaluation Methods

All of the responding schools employed student evaluation of classroom teaching. At the 83 colleges/schools offering APPEs, students also evaluated the experiential teaching provided by APPE preceptors (Table 1). Faculty peer evaluation of classroom teaching took place at 59 (66%) of the responding schools, representing a 16% increase from the 50% reported 10 years earlier. Fifteen (18%) schools employed faculty peer review for evaluation of experiential teaching on APPEs, a 6% increase from the 13% reported a decade earlier (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Teaching Evaluation Methods Used in Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy Between 1996 and 2007

Abbreviations: APPE = advanced pharmacy practice experiences

aData collected in a previous study1 and reported here for comparison purposes.

bOf the respondents, 6 had not yet offered advanced practice experiences and were excluded from the analysis of this item, which was based on an n of 83.

Use of evaluation methods other than evaluation by students has undergone a marked increase over the last decade. Formalized self-appraisal of teaching was used by 44 (49%) of the responding colleges/schools, a 32% increase in use since the prior study. Review of teaching portfolios was used by 28 (32%) of the colleges/schools, a 31% increase. Interviews with samples of students occurred at 26 (29%) of the colleges/schools, a 28% increase. Reviews by teaching experts were conducted at 19 (21%) of the colleges/schools, a 20% increase. Alumni evaluated teaching at 9 (10%) of the schools, a 7% increase (Table 1).

The percentages of the 89 colleges/schools that evaluated the following groups of faculty members were: tenure track, 91%; non-tenure track, 93%; basic/pharmaceutical sciences, 98%; social and administrative sciences, 96%; pharmacy practice, 98%; paid part-time faculty members, 81%; volunteer faculty members, 55%; and adjunct faculty members, 63%.

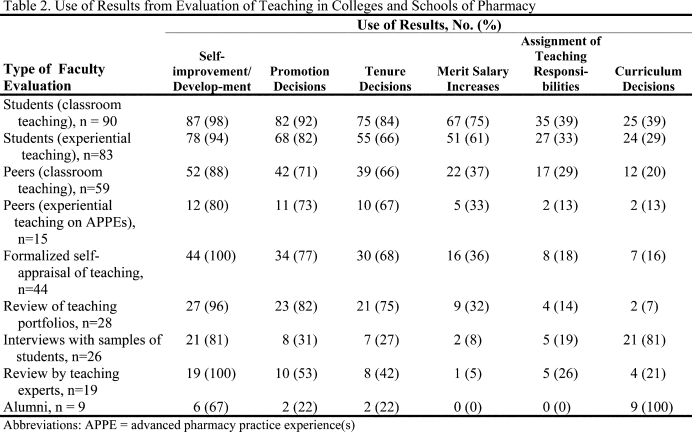

Use of Evaluation Results

Self-improvement/development was the most frequently reported use of evaluation results from each method of teaching evaluation, with the exception of evaluation by alumni (Table 2). Other primary uses (uses reported by greater than 50% of respondents) of student evaluations of teaching included promotion, tenure, and merit salary increases. Promotion and tenure decisions were primary uses of the results from peer evaluation of classroom teaching, peer evaluation of experiential teaching on APPEs, formalized self-appraisal of teaching, and review of teaching portfolios. Interviews with samples of students and evaluations by alumni were primarily used for curriculum decisions. Promotion was a primary use of reviews by teaching experts.

Procedures for Evaluation by Students

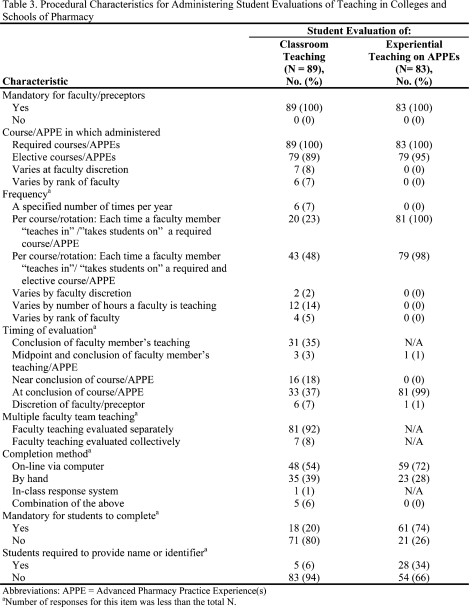

Classroom teaching.

A detailed description of the procedures used for administering student evaluations of classroom teaching is given in Table 3. At all colleges and schools, student evaluation of classroom teaching was mandatory for faculty members. Furthermore, these evaluations were administered in all required classroom courses and the vast majority (89%) of elective courses. At 48% of the colleges/schools, students evaluated a faculty member's classroom teaching yearly within each required and elective course the faculty member taught. At the remaining colleges/schools, the frequency with which student evaluations of classroom teaching were conducted varied depending on 1 or more of the following factors: a specified number of evaluations that could be conducted per year, whether the course was required, at the faculty's discretion, hours taught by the faculty member teaching the course, and rank of the faculty member teaching the course.

The majority (55%) of colleges/schools conducted student evaluations of classroom teaching at or near the conclusion of the course. Another 35% conducted them at the conclusion of a faculty member's teaching within a team-taught course. A few (3%) colleges/schools conducted an evaluation at both the midpoint and conclusion of a faculty member's teaching within a team taught course, while 7% left the timing to the discretion of the faculty member. In team taught courses, when the teaching of more than 1 faculty member was to be evaluated, separate forms for each faculty member were used at the vast majority (92.0%) of schools.

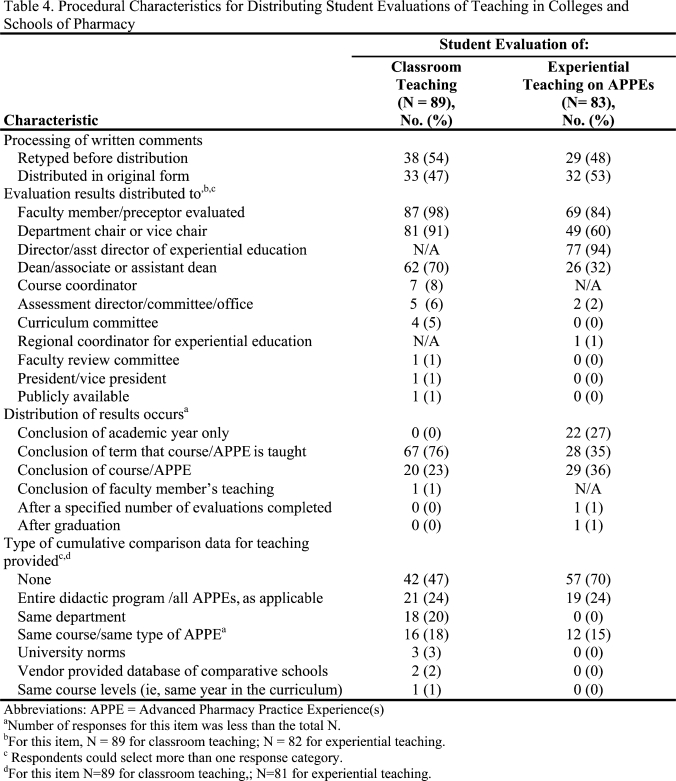

At the majority of colleges/schools, students completed the classroom evaluations online via computer (54%) or by hand (39%), but participation was not mandatory at 80% of colleges/schools. Students at 94% of colleges/schools were not required to provide their name or an identifying number on the evaluation/survey instrument.

Table 4 provides a description of the procedures used for distributing the results of student evaluations of classroom teaching. More colleges/schools retyped students' written comments (54%) than distributed them in their original form (47%). At most colleges/schools, classroom teaching evaluation results were distributed to the faculty member evaluated, department chairs, and deans (including associate and assistant deans). Distribution occurred at the conclusion of the academic term (ie, semester or quarter in which the course was taught) in 76% of schools. Cumulative comparison data were not provided by 47% of colleges/schools. The remaining colleges/schools provided some comparison data, most commonly aggregate data for the entire didactic program (24%) and aggregate data for faculty members in the same department (20%).

Experiential teaching.

Procedures for the administration and distribution of results of student evaluations of experiential teaching are given in Tables 3 and 4. Student evaluation of experiential teaching on APPEs was mandatory for preceptors at all schools. At all schools, these evaluations were administered in all required APPEs and the vast majority (95%) of elective APPEs. At 98% of the schools, students evaluated experiential teaching within each required and elective APPE each time they were offered. At the majority of schools, students completed the evaluations at the conclusion of the APPE (99%) using an online format (72%) and completing the evaluation was mandatory (74%). While the majority (66%) of colleges/schools did not require the students to provide a name or identifier, 34% did require this information. Slightly more schools distributed written comments in their original form (53%) rather than retyping them (48%). Evaluation results were distributed primarily to the director of experiential education, the preceptor who was evaluated, and the department chair. Distribution of results occurred at the conclusion of the APPE (36%), conclusion of the academic term (35%), or conclusion of the academic year (27%). The majority (70%) of schools did not distribute cumulative comparison data.

Distance education.

Additional data collected but not shown in Tables 3 and 4 pertained to distance education. Twenty-four (27%) of the responding schools offered a portion of their didactic program via distance learning. Of these 24 schools, 20 (83%) utilized the same forms and procedures for evaluating teaching that were utilized in the on-site program.

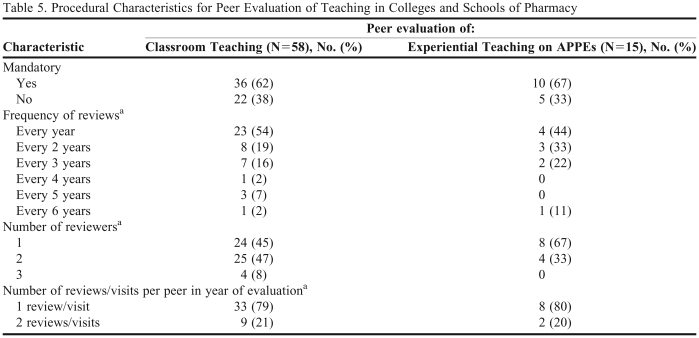

Procedures for Evaluation by Peers

A detailed description of the procedures used for peer evaluation of teaching is given in Table 5. At the majority (62%) of colleges/schools that used faculty peer evaluation of classroom teaching, evaluation was mandatory and occurred yearly (54%). The colleges/schools utilized 1 (45%), 2 (47%), or 3 (8%) faculty reviewers, each of whom conducted either 1 (79%) or 2 (21%) reviews of the faculty peer being evaluated.

Table 5.

Procedural Characteristics for Peer Evaluation of Teaching in Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy

Abbreviations: APPE = advanced pharmacy practice experiences

aNumber of responses for this item was less than the total N.

Peer review of experiential teaching on APPEs was mandatory at a majority (67%) of the colleges/schools that used this form of evaluation. The reviews were conducted yearly at 44% of these colleges/schools. The remaining colleges and schools peer reviewed faculty members every 2 years (33%), 3 years (22%), or 6 years (11%). Either 1 (67%) or 2 reviewers (33%) performed the reviews. Each reviewer made either 1 (80%) or 2 (20%) visits.

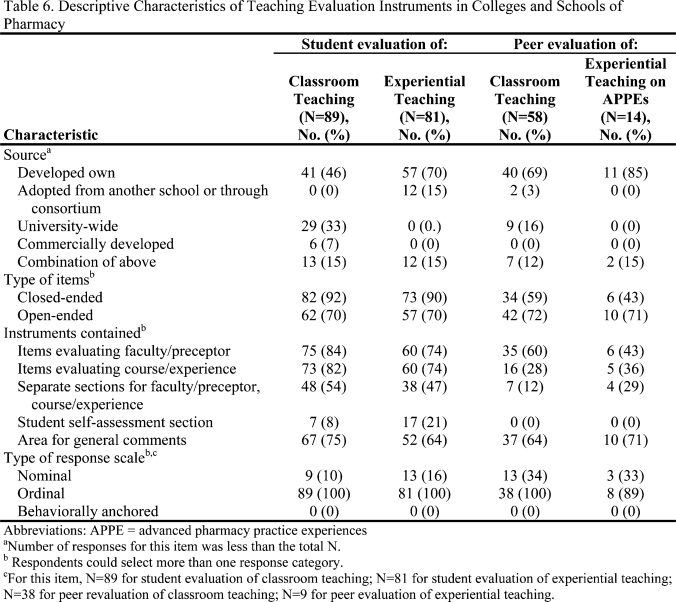

Evaluation Instruments

Table 6 contains descriptive characteristics of the instruments used for teaching evaluations. For student evaluation of classroom teaching, most (46%) colleges/schools developed their own instruments or used one that was employed university-wide (33%). The instruments contain closed-ended items (92%) and open-ended items (70%) for evaluation of the faculty member and course, which were divided into separate sections (54%), with an area for general comments (75%). An ordinal response rating scale was used by all colleges/schools.

The majority (70%) of colleges/schools had developed their own instruments for student evaluation of experiential teaching on APPEs. Some (15%) had adopted instruments from another college/school or acquired instruments through participation in a consortium. The instruments contain closed-ended items (90%) and open-ended items (70%) for evaluation of both the preceptor and the experience; however, less than half (47%) split them into separate sections. The majority of colleges/schools provided an area for general comments (64%). An ordinal response scale was used by all the schools.

The majority (69%) of colleges/schools that used peer evaluation of classroom teaching had developed their own evaluation instruments. The instruments contained both closed-ended items (59% of respondents) and open-ended items (72% of respondents) for evaluation of the faculty member, and an area for general comments (64%). All utilized an ordinal response scale.

Of colleges/schools that used peer evaluation of experiential teaching on APPEs, the majority (85%) had developed their own instruments. For 71% of colleges/schools, the instruments contained open-ended items and an area for general comments. Closed-ended items were used by 43% and varied, with some focusing on the preceptor (43%) and others on the APPE experience (36%). An ordinal response scale was used by the majority (89%) of colleges/schools.

DISCUSSION

Recognition by colleges and schools of pharmacy of the importance of assessment of faculty teaching performance is evidenced by their full participation in student evaluation of classroom and APPE teaching. The use of methods that supplement student evaluations of teaching may be viewed by those being evaluated as more valid than using just one method. This may explain the dramatic increase in the last decade in the use of faculty peer evaluation of classroom teaching, formalized self-appraisal of teaching, review of teaching portfolios, interviews with samples of students, and review by teaching experts. Use of peer review of experiential teaching has not grown as significantly. This may be due to the additional time and permission required for faculty reviewers to visit experiential sites.

The increase in integrated courses taught by multiple faculty members in pharmacy curricula explains the shift in timing of classroom teaching evaluations from a focus on conclusion of a course to a focus on each faculty member's teaching within a course. While completion of student evaluations by hand remains a common practice, the use of computer technology for online completion is widespread and the number of colleges and schools using this method outnumbers those still using the handwritten method.

Limitations

The questionnaire was lengthy (51 items), and not all respondents answered all questions. The data collection method prevented collection and content analysis of actual teaching evaluation instruments. Methods used to evaluate experiential teaching on introductory pharmacy practice experiences were not assessed due to variability in content and delivery of introductory pharmacy practice experiences among colleges and schools, but warrants future examination.

CONCLUSION

Methods for evaluating faculty teaching have broadened in the last 10 years to include other approaches in addition to traditional evaluations by students. Procedures for administering student evaluations have been adapted to address changes in curriculum delivery and technology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express special thanks to Dr. George E. MacKinnon for his advice regarding data collection and critique of the survey instrument.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett CW, Matthews HW. Current procedures used to evaluate teaching in schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 1998;62(4):388–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson ML, Speedie S, Zanowaik P. Final report of the ad hoc committee on teacher/teaching evaluation of the council of faculties. Am J Pharm Educ. 1980;44:285–92. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surratt CK, Desselle SP. Pharmacy students' perceptions of a teaching evaluation process. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(1) doi: 10.5688/aj710106. Article 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson HM, Cain J, Bird E. Online student course evaluations: review of literature and a pilot study. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(1) Article 5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCollum M, Cyr T, Criner TM, et al. Implementation of a Web-based system for obtaining curricular assessment data. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3) Article 80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasiar JB, Schroeder SL, Holstad SG. Comparison of traditional and Web-based course evaluation processes in a required, team-taught pharmacotherapy course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66(3):268–70. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chisholm MA, Miller AW, Spruill WJ, et al. Influence of interactive videoconferencing on the performance of pharmacy students and instructors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64(2):152–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kidd RS, Latif DA. Student evaluations: are they valid measures of course effectiveness? Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3) Article 61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnett CW, Matthews HW, Jackson RA. A comparison between student ratings and faculty self-ratings of instructional effectiveness. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(4) Article 117. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen LB, McCollum M, Paulsen SM, et al. Evaluation of an evidence-based peer teaching assessment program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(3) doi: 10.5688/aj710345. Article 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schultz KK, Latif D. The planning and implementation of a faculty peer review teaching project. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(2) doi: 10.5688/aj700232. Article 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]