Abstract

Objective

To assess pharmacy students' Facebook activity and opinions regarding accountability and e-professionalism and determine effects of an e-professionalism education session on pharmacy students' posting behavior.

Methods

A 21-item questionnaire was developed, pilot-tested, revised, and administered to 299 pharmacy students at 3 colleges of pharmacy. Following a presentation regarding potential e-professionalism issues with Facebook, pharmacy students with existing profiles answered an additional question concerning changes in online posting behavior.

Results

Incoming first-year pharmacy students' Facebook usage is consistent with that of the general college student population. Male students are opposed to authority figures' use of Facebook for character and professionalism judgments and are more likely to present information they would not want faculty members, future employers, or patients to see. More than half of the pharmacy students planned to make changes to their online posting behavior as a result of the e-professionalism presentation.

Conclusions

There is high social media usage among pharmacy students and many do not fully comprehend the issues that arise from being overly transparent in online settings. Attitudes toward accountability for information supplied via social networking emphasize the need for e-professionalism training of incoming pharmacy students.

Keywords: online social networking, e-professionalism, Facebook, technology, professionalism

INTRODUCTION

The nature of social communications has been changing at a moderately rapid pace, precipitated in part by widespread use of online social networking sites such as Facebook and MySpace. Web sites that allow people to project their identity, articulate their social networks, and maintain connections with others are popular, particularly among younger generations.1 Sharing digital photographs, revealing demographic information, displaying interests, and conducting online conversations are just a few of the features utilized. While online social networking services offer several advantages to students (eg, maintaining relationships), they can also raise serious professional issues.2 Because the “conversations” take place in an online setting, these traditionally private interactions become public, which creates a myriad of issues for students and higher education institutions.

The blurring of public and private lives has presented new concerns for society in general, and professional schools in particular. By displaying information in these mediated public sites, students potentially expose private information to an unknown public.3 Safety, privacy, and professional image can be compromised by publishing personal details such as phone numbers, addresses, birth dates, and/or photographs; posting comments and opinions; and/or joining controversial online groups. The lay press is replete with stories of individuals who have experienced legal, academic, and reputation problems due to ill-advised online information sharing.2

In this new digital age, professionals are also becoming more concerned about the image that some are presenting online to the wider public. Sites such as Facebook and YouTube represent a social communication change, exposing individual values that certain professionals may not want the public to see.4 For students and practitioners in professional fields, a new e-professionalism construct has emerged with regard to professional attitudes and behaviors displayed as part of one's online persona.2

Understanding how professional students present themselves in an online environment is becoming an increasingly important topic for a variety of reasons. Although participation in social media activities such as Facebook, blogs, and YouTube, is primarily for personal and entertainment reasons, others (such as employers or patients) may use that information to make judgments of a professional nature. Currently, a disconnect exists between how Facebook was intended to be used (for fun and social activities) and how it may actually be used by some for insight into the member's character, judgment, and professionalism. Because these issues are relatively new and society is still struggling to adapt to the changing paradigm, educating pharmacy students, particularly first-year students, about e-professionalism issues may be warranted.5,6 Comprehending how pharmacy students view the use of their online personas for judgments on professionalism and character is necessary for preparing them for their future role in society. Two of the questions that must be answered in order to design effective education in this area are “Do pharmacy students breach principles of professionalism in online settings, and if so, are those transgressions due to lack of awareness, a defiant attitude, or both?” It is our responsibility as educators to provide training and skills for our students to be successful in the future workplace and we must understand pharmacy students' attitudes and behavior before we can do so effectively.7

This study's 3 primary objectives were to: (1) document pharmacy students' activity on Facebook; (2) determine pharmacy students' opinions regarding online personas, accountability, and authorities' use of online information; and (3) determine the effects of an e-professionalism education session on future online information-posting behavior. This study focused solely on Facebook because of its predominance on US college campuses; however, the concepts discussed within this manuscript also pertain to other online social network sites.

METHODS

A 13-item questionnaire was originally developed and administered to 128 pharmacy students as a pilot test for the study. The questionnaire was slightly revised based on the results of the pilot test, results of follow-up interviews with students concerning the clarity and purpose of the questionnaire, and reviews of the instrument by 3 pharmacy faculty members at different institutions. The final revised questionnaire consisted of 21 questions and was administered to 299 incoming pharmacy students during orientation activities preceding the start of classes. Pharmacy students were surveyed at a Midwest public research university (n = 108), a southern public research university (n = 126), and a southern private, faith-based university (n = 65).

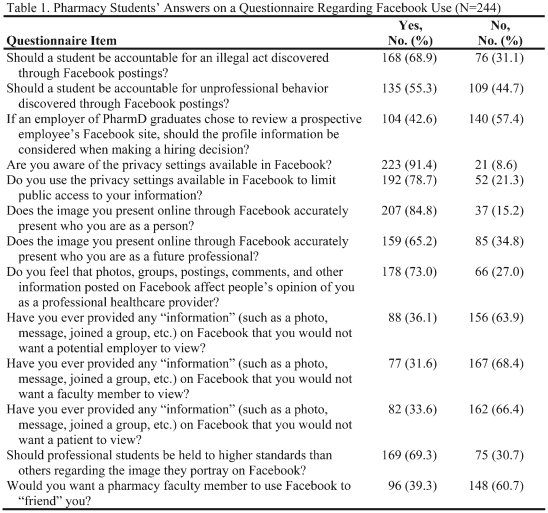

The paper-based questionnaire was anonymous and started with a question concerning whether the pharmacy student had an existing Facebook account. Those who did not have an existing Facebook profile were directed to leave the remaining questions unanswered. Those remaining questions addressed issues related to Facebook usage, accountability, privacy settings, online image, information provided, e-professionalism standards, faculty “friends,” and demographics. Table 1 contains a list of questions and responses to the 13 dichotomous items.

After completing the questionnaire, the pharmacy students received a 10-minute e-professionalism presentation at each respective institution. The researchers at the respective institutions used the same PowerPoint slideshow along with a set of presenter notes, to ensure that all students received equivalent instruction. The purpose of this educational session was to alert pharmacy students to potential professionalism issues and academic and career implications because of indiscreet online personas. Information on and examples of potential problems (eg, safety, privacy, and professional image) with Facebook as identified in academic and lay press were presented.2 The presentation emphasized how imprudent behavior in one's personal life has the potential to affect professional reputation, and that students should carefully consider the types of information they reveal through online and social network settings. Additionally, students were informed that neither their schools nor the universities monitor Facebook for legal or school policy violations, but that university officials can review individual Facebook profiles in matters of discipline.

Following the presentation, those with existing Facebook profiles were administered an additional question concerning potential changes they would make in their Facebook behavior based upon what they learned from the presentation. Response choices included: not applicable; no change because it is not important; no change because online identity is already protected; utilization of privacy features; using more caution with future posts; removal of certain information in existing profile; and other. The study was approved and designated exempt by the Institutional Review Boards at all 3 participating schools. Questionnaire answers were transferred to SPSS, version 16 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago) for data analysis.

RESULTS

Two hundred ninety-nine pharmacy students (100%) returned the questionnaire. Two hundred seventy-seven completed all items on the questionnaire for a 92% usable response rate. Eighty-eight percent (n = 244) had an existing Facebook profile. The age range of students with existing profiles was 21 to 28 years. Sixty-eight percent (n = 167) were over the age of 21 years, and 66% (n = 161) were female. Fifty-three percent (n = 129) logged into Facebook at least once per day and the average time per day spent on Facebook by all users was 22 minutes. There was no significant difference on usage among gender, schools, or age.

Accountability, Image, and Standards

A logistic regression model revealed significant differences in how male and female students responded to the accountability questions. Female students indicated that individuals should be held accountable for illegal actions (p = 0.003) and unprofessional behaviors/attitudes (p = 0.03) displayed on Facebook. Female students also were less likely to provide information on Facebook that they would not want faculty members (p = 0.02), potential employers (p = 0.002), or patients (p = 0.001) to see. There were no significant differences (p > 0.05) among the schools or by age pertaining to the accountability, image, and standards questions (Table 1). Sixty-five percent (n = 159) of pharmacy students indicated that their online persona on Facebook accurately presented who they were as a future healthcare professional. Logistic regression with parameter estimates revealed 3 variables that predicted whether a pharmacy student's Facebook profile reflected who they were as a future professional. Those who indicated that their online persona did not reflect who they were as a future professional were more likely to be opposed to the use of Facebook information for hiring decisions (p = 0.01), think Facebook information does not affect others opinions of them (p = 0.02), and have provided information they would not want a patient to see (p = 0.001).

The majority (69.3%) of pharmacy students indicated that professional students should be held to higher standards regarding the image that their online personas present. However, those who opposed accountability for the display of unprofessional behaviors or attitudes (p < 0.001) or the display of illegal acts (p < 0.001) rejected the notion that professional students should be held to higher standards.

Faculty Facebook Friends

The majority of pharmacy students (60.7%) in general did not want faculty members to “friend” them on Facebook. However, a chi-square test of independence with standardized residuals revealed that pharmacy students in the private school setting (p < 0.001) were more likely to want faculty Facebook friends.

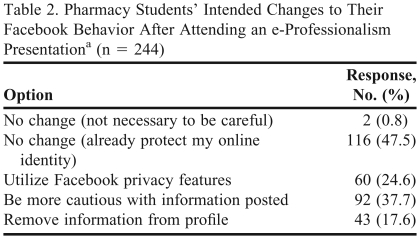

Effects of E-Professionalism Presentation

In response to the question regarding their future online information posting behavior after the e-professionalism presentation, 47.5% (n = 116) indicated that they already took the necessary precautions with their profile and therefore, did not plan to change their posting behavior. Of the remaining 128 students, 98.4% indicated they would make some change in their future posting/profile information. Less than 1% of respondents (n = 2) indicated no change, citing it as unnecessary to be careful with online information. Detailed information on responses to the behavior change question is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pharmacy Students' Intended Changes to Their Facebook Behavior After Attending an e-Professionalism Presentationa (n = 244)

Multiple answers allowed.

DISCUSSION

This study documents the use of Facebook by incoming pharmacy students at 3 schools and their attitudes/opinions toward use of Facebook profile information for character and professionalism judgments. The percentage of pharmacy students with Facebook profiles is consistent with those reported for college students in general.8 The large percentage of users and subsequent time spent using Facebook suggests that it plays at least a nominal role in their everyday lives. Discussants of this topic often mention generational differences with regard to usage and attitudes. Our study did not find any significant differences in students' attitudes or opinions with age. However, participants' ages only ranged from 21 to 28 years, and a broader population including older students would have been necessary to detect generational differences.

One of the most troubling aspects of college students and Facebook is the apparent disconnect on their opinions of fair use' of Facebook profiles by others and the reality of their open access nature. With regard to employers, Facebook provides information that resumes, transcripts, and interviews may not provide. While a literature review revealed no research on if/how employers of doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) graduates use online social networking information in hiring decisions, general population studies suggest that 11% of all employers access interviewees' Facebook profiles during the hiring process.9 Over half (57%) of the pharmacy students in this study with Facebook profiles indicated that it was unfair for employers to use this information, and 36% have posted some type of information that they would not want potential employers to see. These results suggest that many pharmacy students do not have a full understanding of what constitutes private versus public information and/or of the possible ramifications of making private information public. One might not want behaviors and attitudes from private settings to be used in judging professional or career-related abilities; however, once private actions become public, the distinct private life (as has been traditionally defined) ceases to exist. Because of the rapid onset of technologies that have created and popularized online personas, society has yet to adjust to this new paradigm. Philosophically, many of us are now struggling with how to delineate between public and private with regard to personal information freely provided in online settings. Until society is able to grasp the new paradigm, further discussion on online identity protection is warranted.

Additionally, a large percentage of pharmacy students (45%, n = 109) believed that academic institutions should not use information on Facebook as evidence of unprofessional behavior. While the merits and harms of Facebook scanning by colleges and schools can be philosophically debated, this opinion is indicative of the attitude that Facebook is intended only for students and what is posted there should only be used by students. The fact that the majority of students do not want faculty Facebook “friends” further supports that attitude. Although 90% of pharmacy students stated it was important or very important to be cautious with Facebook profile information, approximately a third indicated they have posted information they would not want faculty members, potential employers, or patients to see. This suggests that privacy concerns do not necessarily coincide with Facebook posting behavior, which is consistent with prior research involving college students. 10 The awareness of privacy settings does not necessarily mean that they are used. The results may also underscore the need to consider “e-professionalism” issues as a part of pharmacy student professionalism. As public and private information boundaries become less apparent, the criteria for judging one's professional image becomes more ambiguous, especially with regard to attitudes and behaviors displayed to patients.

One interesting finding of this study is the rather stark contrast between male and female students concerning attitudes and behavior in online social settings. Male students were significantly more likely to present online personas containing information they would not want faculty members, employers, and patients to see. Consequently, male students were also more likely than female students to oppose accountability to authority figures for information presented in online social network settings. It is unclear whether this simply reveals a more rebellious nature among male students, but is significant information in terms of specifically reinforcing e-professionalism (and possibly professionalism) to male students within education settings.

Approximately a third (n = 75) of the pharmacy students felt that professional students should not be held to a higher standard with regard to online personas. These same respondents did not think students should be held accountable for information posted in an online setting. This is further evidence that a substantial number of pharmacy students reject the notion that information displayed publicly can be considered “fair game” for others to interpret. This may also indicate a general lack of understanding of the professionalism construct in general.

Almost 85% (n = 207) of the pharmacy students indicated that their online personas accurately portrayed who they were as a person. However, only 65% (n = 159) indicated that their profiles reflected who they would be as a future healthcare provider. This difference could mean one of several things. First, it might reveal that some of these incoming pharmacy students recognized that professional growth and maturity was needed before entering the profession. For others, it could mean that online personas were something they had not previously considered and therefore, simply had not attempted to maintain a professional image online. Third, it could reflect the attitude that online social networking profile information should be off limits to judgments on character or professionalism. Because 2 of the 3 variables predicting whether a student's profile reflected a professional persona were attitudinal, this suggests that the third explanation may be the most correct.

While the overall results concerning usage, accountability, and professionalism may be alarming to some, they are not particularly surprising. There appears to be somewhat of a generation gap on attitudes toward online social activities, with the younger generations defining “appropriate” use differently than older generations. As evidenced by the slight majority (50%, n = 123) who indicated a change in their future online social networking behavior, educational sessions may be necessary to inform pharmacy students about the potential problems that may result from being overly transparent in online social networking settings. Understanding how cues in an online environment aid in impression formation is becoming a necessity in the 21st century, especially for those who work in professional fields.11 The opinions of many students toward accountability and standards in the online environment may be alarming to some. Many pharmacy students simply may be naïve about potential negative consequences associated with the public display of their private lives and the signals that it sends to others.12 Others may have deep-rooted attitudes that may be difficult to change, except through continued exposure to professionalism ideals. We do not expect pharmacy students to learn appropriate professional behavior without significant instruction, mentoring, and enculturation into the profession. Likewise, alongside traditional professionalism instruction, e-professionalism training and reinforcement may be required in this new digital age to address areas of concern with regard to online personas.

Limitations of this study include use of a census sample at only 3 institutions; however, the authors do not suspect significant differences among students at other schools. Research on other types of online behavior (e-mail, online discussion boards, and other social networking sites) would also be valuable. This study contained a self-report of student posting activities. Analysis of actual online personas may reveal different information in terms of types of information displayed. Further research is also needed with pharmacy students throughout all years of a pharmacy program. As students become acclimated to the professional school climate, their attitudes and online personas might change. Exposure to general professionalism tenets may alter students' views of accountability and professional image. However, without e-professionalism training, pharmacy students might also be influenced by the “informal curriculum” of other college students and project online personas that are contradictory to health professions ideals. Online personas that reveal disrespect to others, racist remarks, drug/alcohol abuse, or other unsavory personality characteristics may reflect poorly on an individual as a professional healthcare provider and negatively affect career opportunities.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provided insight into incoming pharmacy students' Facebook activity, as well as their attitudes toward online personas and accountability for information displayed on online social networking sites. Facebook plays at least a nominal role in the daily lives of incoming first-year pharmacy students, which is consistent with social networking usage statistics among other college students. A large percentage of pharmacy students in this study felt that individuals should not be held accountable to authority figures for information posted on Facebook. In particular, male students were significantly more likely than female students to oppose accountability for information posted on Facebook. Approximately a third of pharmacy students have posted information that they would not want faculty members, potential employers, and patients to see. A combination of lack of awareness and inappropriate attitudes may contribute to student e-professionalism transgressions. Society is in a state of flux with regard to privacy in online settings and there is no consensus on what is fair and acceptable use of information gleaned from online media. Professional students need an awareness of online personas and the impressions generated from them in order to adapt to changing social communication paradigms. A presentation that raises the awareness of threats to privacy, security, and professional image resulting from online social networking activity may be effective at changing students' posting behavior on Facebook. Faculty members and administrators need to be aware of these new “e-professionalism” issues in order to educate and train pharmacy students for their future as health care professionals.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ellison N, Steinfeld C, Lampe C. Spatially bounded online social networks and social capital: The role of Facebook. Paper presented at: Annual Conference of the International Communication Association; June 19-23, 2006; Dresden Germany. Available at: https://www.msu.edu/∼nellison/Facebook_ICA_2006.pdf.

- 2.Cain J. Online social networking issues within academia and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1) doi: 10.5688/aj720110. Article 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd D. Social network sites: public, private, or what? Knowledge Tree. 2007:13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farnan JA, Paro JA, Higa J, Edelson J, Arora VM. The YouTube generation: Implications for medical professionalism. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):517–24. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson LA, Dawson K, Ferdig R, et al. The intersection of online social networking with medical professionalism. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):954–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorrindo T, Gorrindo PC, Groves JE. Intersection of online social networking with medical professionalism: Can medicine police the Facebook boom? J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):2155. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0810-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner S. Preparing for the Nexters. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4) doi: 10.5688/aj700487. Article 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Statistics. Facebook. http://www.facebook.com/press/info.php?statistics. Accessed May 12, 2009.

- 9. One in 10 employers will use social networking sites to review job candidate information [press release]. Bethlehem, PA: National Association of Colleges and Employers; September 22, 2006. http://www.naceweb.org/press/display.asp?year=&prid=244. Accessed May 12, 2009.

- 10. Acquisti A, Gross R. Imagined communities: awareness, information sharing, and privacy on the Facebook. Seattle, WA: Privacy Enhancing Technologies Workshop (PET); 2009. http://petworkshop.org/2006/preproc/preproc_03.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2009.

- 11.Switzer JS. Handbook of Research on Virtual Workplaces and the New Nature of Business Practices. Hershey PA: 2008. Impression formation in computer-mediated communication and making a good (virtual) impression; pp. 98–109. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peluchette J, Karl K. Social networking profiles: An examination of student attitudes regarding use and appropriateness of content. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11(1):95–7. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]