Abstract

Objectives

To develop and implement a health fair and educational sessions for elementary school children led by health professions students.

Design

The structure and process were developed with elementary school administration to determine the health topics to be covered. Students and faculty members created a “hands-on,” youth-oriented health fair and interactive health educational sessions. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected on learning outcomes from the underserved child population and health professions students.

Assessment

The health fair and educational sessions increased awareness of underserved youth in the areas of critical health behaviors, purposeful education on health issues facing their community, and exposure to careers in various health professions. The activities provided meaningful learning experiences for the health professions students.

Conclusion

The health education program model is an excellent way to teach health education, communication and critical thinking skills, and service learning to health professions students.

Keywords: health fair, youth education, service learning, health disparities, community service

INTRODUCTION

Realizing the importance of a healthy lifestyle and consciously making the decision to adopt one is a necessary first step towards improved health and well-being. Dedicating resources to empower youth to take an active role in their health and modify their lifestyles is necessary as today's youth face many health-related challenges including obesity, diabetes, youth violence, and substance use and abuse. Family, schools, health care professions, and community organizations realize that health goes beyond the absence of disease and entails the complete physical, mental, and social well-being of our children. Addressing the concerns of today's children requires adopting an approach to young people that goes beyond the health sector and facilitates active participation of youth as future agents of change in health and wellness. Childhood and adolescence are optimal times to establish life-long health behaviors, learn about risk reduction and disease prevention, connect with positive adult role models, and initiate long-term relationships with health care providers.

Across the United States, minority health professions are underrepresented (with African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans constituting one-fourth of the population, but only 10% of the nation's health workforce).1 Physicians, nurses, dentists, and other health care professionals have little likeness to the diverse populations they serve, leaving many Americans feeling excluded by a system that seems cold, distant, and uncaring. It is known that minority health care professionals provide more care for the poor and uninsured and for patients in their own racial/ethnic groups than non-minority providers. Minority representation within the health professions directly relates to access to health care services in underserved communities.

In 2007, Creighton University School of Pharmacy and Health Professions partnered with a local parish that has a highly underserved minority population to provide a successful senior health fair. The success of this partnership highlighted neighborhood residents’ unmet health needs, which led to further discussions with parish school staff members about expanding this type of program to area youth. There was interest among health professions faculty members and students to develop a health-awareness program for the parish elementary school children. The elementary school's population was 99% African-American and more than half of the students were at or below the poverty level.

In order to promote wellness in this underserved population, representatives from 4 of Creighton University's Health Professions Programs (pharmacy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and nursing) created and implemented interactive youth-oriented health education programs and a participatory, hands-on health fair. The health fair was intended to be an engaging strategy to meet a community's needs related to health promotion, education, and disease prevention. The goals of this program were threefold: (1) to heighten awareness among elementary school students of health profession career options; (2) to improve the well-being and encourage healthy lifestyles in lower-middle school student participants; and (3) to provide a learning experience/learning environment for health professions students.

DESIGN

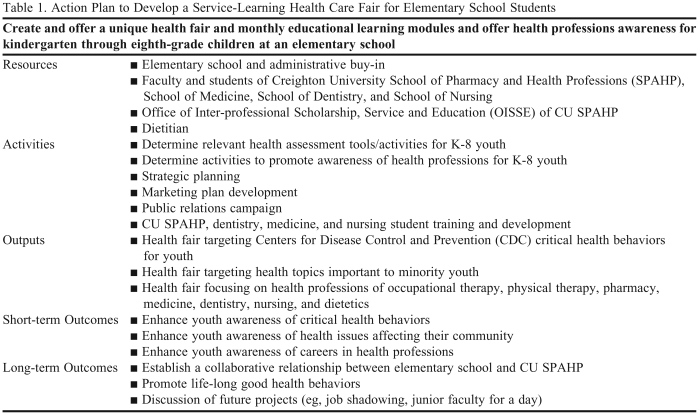

Previous collaboration with the parish health ministry had established a successful partnership with the parish school. Creighton University had 20 faculty members and students involved in the planning of, and subsequent implementation of, the educational sessions and health fair. The project plan (Table 1) lists the tasks resources, actions, and outcomes related to the planning and implementation of the project. Our hope was to have the faculty members and student teams from Creighton motivate and assist elementary school students to become increasingly knowledgeable about their health status and begin to take command of their personal well-being.

Table 1.

Action Plan to Develop a Service-Learning Health Care Fair for Elementary School Students

Faculty members from the School of Pharmacy and Health Professions at Creighton University, in collaboration with the teachers at the elementary school, identified health topics to be covered based upon their needs. The elementary school faculty named nutrition, physical activity, and stress management as pressing issue facing the children. Health professions students who were interested in promoting positive health behaviors to these elementary students were identified and asked to participate. This project was considered exempt by the university's Internal Review Board because teaching outcomes were being measured.

Under the supervision of each profession's faculty member (n = 6), pharmacy students (n = 3), physical therapy students (n = 3), and occupational therapy students (n = 8) presented monthly educational sessions (January through March) to the elementary school students. These sessions focused on health education, risk, prevention, and wellness. The presentations were to be given to kindergarten through eighth-grade children (n = 125 students and 13 teachers). The elementary students would be brought out in groups (kindergarten through second grades, third through fifth grades, and sixth through eighth grades) and the health professions student would give 3 separate presentations to best accommodate the learning styles and cognitive abilities of the students. This allowed the Creighton students to modify their presentation content so that it was age appropriate for each group. Additionally, at the beginning of each educational session, each group of health care professions students discussed the types of activities that they did in their profession and why they chose their profession. After each of the educational sessions, third through eighth-grade students were given posttest questions to determine the effectiveness of the presentations and to determine whether they had any impact on student knowledge of health promotion concepts and practices.

A poster contest with the topic “What It Means to Be Healthy” was held for the elementary school students. The winners of the contest received donated prizes. The 6 winning posters were then used as flyers to promote the health fair and also served as passports that were stamped as the children attended each health fair booth. The winning flyers were posted around the school and sent home to encourage parents to attend. Principals from other underserved schools also received an invitation to attend the event, in hopes of establishing future collaborative projects.

Creighton University supported and promoted the health fair because it was congruent with its mission of service to others, the inalienable worth of each individual, and appreciation of ethnic and cultural diversity. Creighton University professional programs (pharmacy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, dentistry, medicine, and nursing) provided faculty members and students for their health-related booths and actively demonstrated how one can identify and prevent youth-related health issues, as well as career options in several health professions and what students do in their field. We anticipated that this project would foster interest among these students in the health care field.

In April 2008, a youth health fair targeted at the needs of these students took place. The health fair was presented to approximately 125 elementary school children, 13 teachers, and numerous parents from the elementary school. Creighton University had 52 student volunteers helping with the fair and 10 faculty members present.

Health professions students served in 2 capacities. The professions students either created and staffed a booth, or served as a “navigator” for the elementary school students. At the 13 individual health fair booths, the Creighton University students worked together in small groups. All of the booths had an interactive “hands-on” learning activity.

Three-fourths of the booths additionally had poster presentations and specific take-home information for parents and children. The health professions students carefully chose children's themes for all of the posters and made them age appropriate.

As “navigators,” the health professions students were randomly assigned 2 to 3 elementary school students and escorted the children from booth to booth. Each elementary school student had a passport and as they attended each booth and completed the activity, they received a stamp. The passports were intended to engage the children and to ensure that they visited each booth. In addition to serving as an escort for the children, the professions students served as role models, encouraging the children to consider a career in health care.

Other interactive activities took place at the exhibits, such as pharmacy students filling mock prescriptions and using a mortar and pestle to show the children how to triturate their “prescription”; physical therapy students demonstrating how they use exercise balls for rehabilitation and fitness; occupational therapy students showing how they use different devices to help patients overcome physical disabilities; dental students demonstrating proper tooth brushing and flossing techniques with oral mouth models; and nursing students emphasizing the importance of safety, with children spinning a Safety Wheel (Successful Events, Hagaman, New York) and answering age-appropriate questions. Additionally, medical students used anatomical models to explain how to take care of their eyes, ears, and heart. Nursing students used the Glo-Germ (DMA International, Castle Valley, Utah) ultraviolet light kit to simulate germs and show the effectiveness of proper hand washing. Pharmacy students presented a video and engaged the children in interactive games about the dangers of smoking. Pharmacy students with a display of childproof see-through containers, one containing a medication and one containing candy, illustrated the dangers of unlabeled medication and patient safety practices. Children also had the opportunity to use Fatal Vision (Innocorp, Ltd., Verona, Wisconsin) goggles, which simulate the effects of someone who is impaired.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Elementary Student

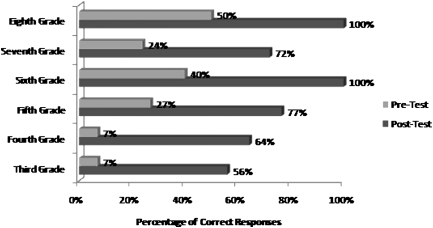

To assess whether Creighton health professions students had contributed to the awareness of elementary students about health care career choices, identical pre- and post-survey instruments were completed by 90 of the third- through eighth-grade elementary students. Thirty-five elementary students were in kindergarten through second-grade and were not given the pre-intervention and post-intervention survey instruments because of the additional time they would take teachers to process. The surveys were administered to the students in January and May. The 6-question multiple-choice survey instrument was designed to assess elementary students’ knowledge of the roles and responsibilities of each health care professional (pharmacy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, dentistry, nursing, and medicine).

The Creighton health professions students gave monthly educational sessions to the elementary school students. After each session, a post-intervention survey instrument with 5 questions was administered to 90 of the third through eighth grade students. As explained above, the 35 kindergarten through second-grade students did not participate in the surveys. The surveys were administered in January, February, and March. The 5-question survey was designed to determine whether the presentations had any impact on student's knowledge of health promotion and healthy lifestyles.

Based on a comparison of the percentage of questions answered correctly in the pretests and posttests, the children's knowledge of pharmacy increased an average of 52.3%; knowledge of physical therapy increased an average of 35.5%; knowledge of occupational therapy increased an average of 16.2%; knowledge of dentistry increased an average of 16.2%; knowledge of nursing increased an average of 13.5%; and knowledge of medicine increased an average of 5.2% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Results of a survey regarding elementary school students’ perceptions of/beliefs about pharmacists before and after participation in a health fair and interaction with pharmacy students.

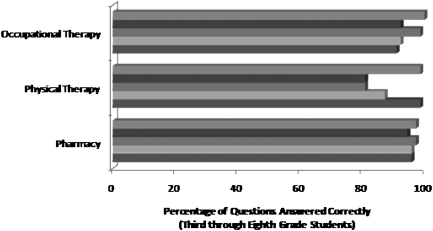

The results of the post-intervention surveys are shown in Figure 2. After the pharmacy presentation, elementary students answered 96% of the questions correctly; after the physical therapy presentation; 90%; and after the occupational therapy presentation; 96%.

Figure 2.

Elementary school students’ perceptions of/beliefs about health careers after participation in educational sessions with health profession students.

Health Professions Student

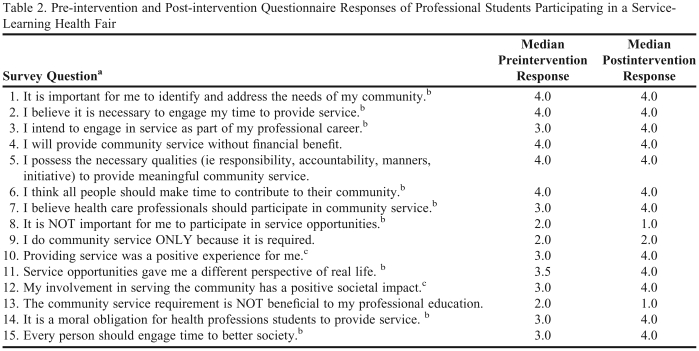

Creighton health professions students were administered a voluntary 15-question service-learning survey before and after their educational session and/or health fair participation. The survey instrument was developed by an interprofessional group from Creighton University and had been used extensively with Creighton health professions students involved in community engagement and health promotion. 2 The online survey instrument used a 5-point Likert scale (5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = undecided, 2 = disagree, 1 = strongly disagree). The purpose of the survey was to measure any change in attitudes toward service-learning in the professional curriculum. Forty-five students completed the pre-intervention survey and 37 students completed the post-intervention survey.

After the health fair, the 52 students gathered with faculty members and a Creighton University chaplain to have a group reflection focusing on the event. Topics addressed were what went well, what could be improved, and any stories that impacted the students. Post activity feedback from students conveyed that they enjoyed working with elementary school children; they were surprised how knowledgeable and appreciative the elementary school children were; and how many of the elementary school children freely discussed that already knew someone with substance abuse problems. Things that they thought could be improved were logistical in nature and could be easily remedied by the next offering.

Additionally, 13 pharmacy students who were concurrently taking a pediatric elective were asked to complete a reflective survey instrument. The 4-item survey instrument asked: (1) What feeling/emotions did you experience while participating in this service activity? (2) Describe 1 experience that touched you personally during this service activity and how it touched you. (3) What skills did you develop in the service activity that you may use in your future practice? (4) How will you implement what you learned about yourself from this service activity in your future role as a pharmacist? The purpose of this survey was a guided post-experience reflection designed to capture the depth of the service experience.

The objectives for the health professions students were assessed using a mixed method approach, collecting both quantitative and qualitative data for analysis. Quantitative results were collected from the online service-learning survey. Median responses are presented in Table 2. The Wilcoxon signed rank test, employing a Bonferroni adjustment to reduce the probability of Type I error, was used to assess for response differences from pretest to posttest. A number of significant differences were indicated (Table 2). In addition, response categories were collapsed into either agree (ie, strongly agree and agree) or disagree (ie, strongly disagree and disagree). The chi-square test, employing a Bonferroni adjustment, was used to test for significant differences in responses. Although the quantitative data indicated no significant differences between pretest and posttest, all of the health professions students expressed a positive impact on their attitudes toward service-learning as evidenced by verbal reflection, written reflection, and the Likert survey. The instructors found value in knowing there was a change in attitudes toward service-learning because of our school's mission of community service and care of the whole person.

Table 2.

Pre-intervention and Post-intervention Questionnaire Responses of Professional Students Participating in a Service-Learning Health Fair

a1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; 4 = strongly agree

bp < 0.01

cp < 0.001

Response from the Participants

Elementary school teachers and parents who attended the health fair were asked to complete a 9-question evaluation intended to provide feedback that would assist educators in making any future modifications needed to make the health fair more successful.

Theme Analysis of Reflective Commentary

Qualitative data were collected from Creighton student reflections and theme analysis was conducted by a group of pharmacy faculty members with expertise in pediatrics, community outreach, and service-learning. The most prominent theme was one of increased communication skills. Pharmacy students reported increased knowledge, skills, and attitudes toward communication after participating in the health fair. Students stated their confidence in speaking with pediatric patients greatly increased and they reflected on how they had to change their communication level with different age groups. Ninety-four percent of students expressed that the health fair helped them to educate a large group of students and increased their self-assurance by having to “think on their feet.” One student wrote:

“As a pharmacist, I will need to be able to communicate with children in a way that they understand. School-age children want to feel grown-up and they want to be involved in taking care of themselves, which includes taking their medicine. At the health fair, I talked to children about what medicine is, so it was good practice for the future. I know now that I can include them in their own care.”

Pharmacy students also stated they developed new social skills that they could use in their future pharmacy careers. Most articulated they had developed patience and an understanding of the need for adaptability and flexibility. They also felt they were more culturally sensitive and empathetic as a result of learning about the underserved children's life experiences.

When asked to describe an experience that touched them personally, 95% of respondents talked about service to others and giving back to the community. This type of student feedback directly supports the university and school's mission of service to others.

The final recurring theme was the students’ sense of self-awareness and self-assessment. Students reported entering these events feeling anxious or unsure but emerged with a new sense of accomplishment.

Through our theme analysis, the instructors recognized that students could self-identify and articulate their role of “pharmacist as an educator.” They possessed the emotional intelligence skills of self-awareness and self-assessment, which are valued qualities in a pharmacy graduate. The instructors felt that this learning experience contributed to a more emotionally mature pharmacy student and caring person. All of the qualitative data obtained from health professions students supported the third project goal to provide a learning experience/learning environment for health professions students.

Feedback received from elementary teachers and parents had themes of appreciation for Creighton service and time, the creation of an active-learning environment, and active engagement for the elementary school students. The parents and teachers spoke appreciatively of the Creighton students’ hard work and commended the students for the professional quality of their work, their knowledge of topics, and their attention to detail.

DISCUSSION

Health fairs and educational sessions are one approach to educating our youth and emphasize health promotion and disease prevention. In searching the professional literature, there is little specifically written about the effectiveness of health fairs and their impact on underserved children's knowledge and behavior. Our evaluation of this project demonstrated that we were effective in terms of dissemination of health information to elementary school students. The results from our surveys support the achievement of project goal 1, heightening career awareness, and goal 2, improving well-being and encouraging healthy lifestyles among elementary school students. As health professions educators, we must face the task of educating students to become competent in the sciences while preparing them to become engaged citizens willing to tackle disparities in our heath care system.3 We consider our program multifaceted, allowing professional students to learn with and from each other about their roles and responsibilities in community health promotion and prevention.

The late Professor Robert Chalmers of the Purdue University School of Pharmacy wrote: “Traditionally, a pharmacist's primary role has been dispensing medications and providing counseling. We have not been engaged in a caring relationship with patients, nor have we felt the same responsibility for outcomes as other health professionals. The field of pharmacy now plans to make a more meaningful contribution in our changing health profession; our pharmacists must be trained to get more involved with patients. Service-learning gives students greater insights into patients and patient care.”

Other benefits of service-learning include building critical-thinking capacities, becoming lifelong learners and participants in the world, reducing stereotyping and allowing for better cultural understanding, and developing interpersonal skills, citizenship, and social responsibility.4 We were also able to give credit to students who applied this experience toward the service-learning component for introductory pharmacy practice experience.

The first offering of this project was successful and there are plans to repeat the project in future years based on the positive feedback from both the elementary school and health professions students. The university as a whole strives for diversity in its student body population and by virtue of this diversity focus, minority students who participated complemented the diverse elementary school population. The project's success has led to further discussions of collaboration with other underserved schools in developing similar programs. Engaging students in service-learning has effectively combined the principles of experiential learning with goals such as personal, moral, and career development; academic achievement; and “reflective civic participation.”5

SUMMARY

As instructors who facilitated and directed health professions students in this project, we witnessed leadership, personal growth, increases in cognitive skills, and application of critical thinking skills. We became more aware of the role that reflection plays in connecting life experiences to learning. Service-learning should be in every professional curriculum to promote the development of a well-rounded, reflective professional who is prepared to take on his or her role as a productive pharmacist as well as a contributing member of society. This service project is reproducible and can be adapted to other school's curricula. This type of program further supports the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) and the Pharmaceutical Services Support Center's (PSSC) caring for the Underserved Curriculum Task Force recommendation of a professional mandate to proactively provide the highest quality care for all.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was funded through the Omaha Urban Area Health Education Center (AHEC).

REFERENCES

- 1.Missing Persons: Minorities in the Health Professions. A Report of the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. 2004:1–201. Accessed October 23, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Diaz-Gallegos D, Furco A, Yamada H. The higher education service-learning surveys. University of California-Berkeley; 1999. Available at: http://servicelearning.org/filemanager/download/HEdSurveyRel.pdf Accessed May 6, 2009.

- 3.Redman RW, Clark L. Service-learning as a model for integrating social justice in the nursing curriculum. J Nurs Educ. 2002;41(10):446–8. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20021001-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eyler J, Giles DE. Where's the Learning in Service Learning? San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamb C, Swinth R, Vinton K, Lee J. Integrating service learning into a business school curriculum. J Manage Educ. 1998;22(5):637–54. [Google Scholar]