Abstract

Hypodermic needles are in widespread use, but patients are unhappy with the pain, anxiety, and difficulty of using them. To increase patient acceptance, smaller needle diameters and lower insertion forces have been shown to reduce the frequency of painful injections. Guided by these observations, fine needles and microneedles have been developed to minimize pain and have found the greatest utility for delivery of vaccines and biopharmaceuticals such as insulin. However, pain reduction must be balanced against limitations of injection depth, volume, and formulations introduced by reduced needle dimensions. In some cases, needle-free delivery methods provide useful alternatives.

Keywords: drug delivery, hypodermic needle, insulin delivery methods, microneedle injection, needle gauge, needle length, pain from needle insertion

Hypodermic Needles

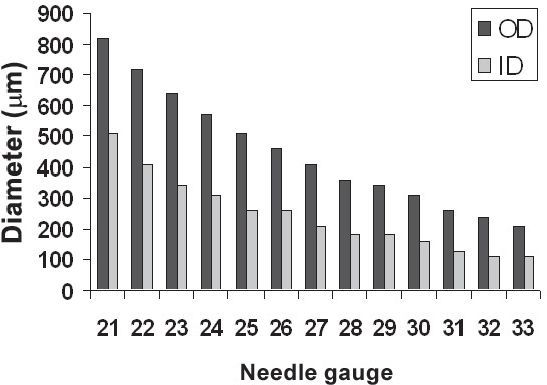

The hypodermic needle was invented independently by Charles Gabriel Pravaz in France and by Alexander Wood in England in 1853.1 Since then, needles have become the most widely used medical device, with an estimated 16 billion injections administered worldwide.2 Currently, needles are available in a wide range of lengths and gauges (i.e., diameters) either to enable delivery of drugs, vaccines, and other substances into the body or for extraction of fluids and tissue (Figures 1 and 2). The appropriate needle gauge and length are determined by a number of factors, including the target tissue, injection formulation, and patient population. For example, venipuncture requires the use of needles typically as large as 22–21 gauge inserted to depths of 25–38 mm to withdraw milliliters of blood.3 In contrast, vaccines usually require injection of less than 1 ml of fluid and, therefore, 25- to 22-gauge needles with a length of 16–38 mm are adequate.4 Insulin delivery, which involves even smaller volumes and is typically carried out by patients in diverse everyday settings, benefits from still smaller needles, usually of 31–29 gauge inserted to a depth of 6–13 mm.5

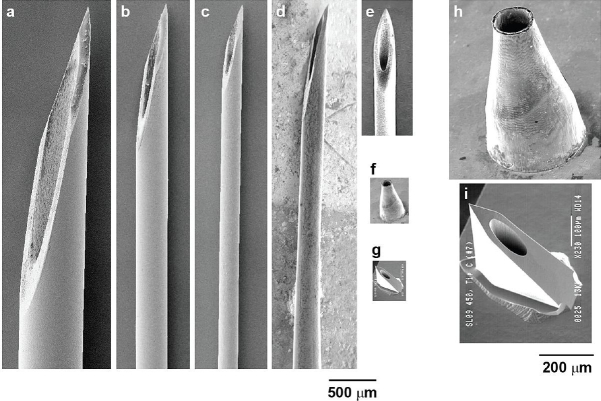

Figure 1.

Size comparison among hypodermic needles and microneedles. Scanning electron micrographs of (a) 21-gauge, (b) 27-gauge, and (c) 31-gauge hypodermic needles (BD Technologies) and (d) tapered 33-gauge Terumo NanoPass hypodermic needle (image courtesy of Kyuzi Kamoi). Scanning electron micrographs of microneedles at the same magnification as hypodermic needles: (e) stainless steel microneedle with a total length of 1.5 mm (image courtesy of John Mikszta, BD Technologies), (f) nickel microneedle with a length of 500 μm, and (g) silicon microneedle with a length of 450 μm (image courtesy of NanoPass Technologies). Higher magnification scanning electron micrographs of (h) nickel microneedle and (i) silicon microneedle for the needles shown in f and g, respectively. (Note that although they have the same name, the NanoPass 33-gauge hypodermic needle by Terumo and the company NanoPass Technologies are unrelated.)

Figure 2.

Outer and inner diameters of conventional hypodermic needles as a function of needle gauge.

Although hypodermic needles are effective, the pain, anxiety, needle phobia, and difficulty of use have made them widely unpopular with children and adults alike.6,7 Consequently, there is poor compliance in initiating and adhering to needle-dependent therapies, such as insulin administration.8 Therefore, less painful needles and more convenient delivery systems are being developed.

Factors Affecting Pain from Needle Insertion

To mitigate pain from hypodermic injections, the effect of needle geometry on pain has been investigated. Needle gauge has been shown to significantly affect the frequency of pain during needle insertion into the skin of human subjects.9 For example, insertion of a 27- or 28-gauge needle (Figure 1b) had an approximately 50% chance of being reported as painful, which was significantly greater than insertion of a 31-gauge needle (Figure 1c), which had a 39% chance of causing pain. The likelihood of bleeding was also observed to decrease with decreasing needle diameter. Increasing needle length is also expected to increase pain, although to our knowledge the literature does not contain formal studies specifically demonstrating this effect.

In addition, the mechanics of needle insertion has been found to significantly affect pain. Both the force and the mechanical workload (i.e., area under the force-displacement curve) of hypodermic needle insertion have been found to positively correlate with the frequency of pain.10,11 Thus, needle tip sharpness and other factors, such as lubrication, which can reduce the force of insertion and mechanical workload,12 are important parameters that can be optimized to reduce pain from needle insertions.

Development of Less Painful Needles

Motivated to make less painful needles, there has been growing interest in fabricating smaller needles that should be less painful. Progress in this field has been limited by the need for small needles to reliably insert into the skin, to have sufficient mechanical strength, and to be manufactured in a cost-effective manner.

Fine Needles

By scaling down conventional manufacturing processes, a number of companies have developed fine needles smaller than 30 gauge that are used largely for insulin delivery. Examples include 31-gauge Micro Fine Plus® needles (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and 33-gauge NanoPass® needles (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan), both of which measure 5 mm in length (Figures 1c and 1d). A significant reduction in pain and bleeding from use of a 33-gauge needle compared to a 31-gauge needle has been demonstrated.13 However, patient satisfaction was improved only after application of a suitable lubricant to the 33-gauge needle, which presumably reduced insertion force and workload.

Microneedles

To further minimize pain during injection, 31-gauge needles have been manufactured to be just 1–3 mm long (Figure 1e). These needles are further designed to remain within the skin and thereby facilitate intradermal vaccination, which may be facilitated by targeting antigen delivery to the skin's Langerhans and dermal dendritic cells. A number of vaccines have been delivered in this way to animal models and human clinical trials are well under way.14,15 These short needles also have potential for delivery of other therapeutics into the dermis, which is well vascularized16 and can thereby enable rapid uptake of drugs into systemic circulation with improved pharmacokinetics.

Even submillimeter needles can be effective, because the primary barrier to delivery of drugs into the skin is its topmost layer called the stratum corneum, which is just 10–20 μm thick.17 Recognizing this fact, micrometer-scale needles have been developed to deliver drugs into the skin (Figures 1f–1i).18–21 These microneedles are sufficiently long to penetrate through the stratum corneum, yet small enough to cause little or no pain. Delivery of insulin using microneedles has been demonstrated in diabetic animal models19–21 and, more recently, in diabetic human subjects.22 Because of their very small size, novel microfabrication methods have been adapted from the microelectronics industry to produce these microneedles using methods suitable for inexpensive mass production.

Confirming the hypothesis that microneedles can avoid pain, a study in human volunteers found that 150-μm-long microneedles were reported as painless.23 More recent results from our laboratory examined the effect of microneedle geometry on pain in greater detail and concluded that microneedle length and the number of microneedles are the most important geometric parameters affecting pain and that 500- to 750-μm-long needles can cause 10 to 20 times less pain than a 26-gauge hypodermic needle (data not shown).

How Small Is Small Enough?

Reducing needle size reduces pain and generally increases patient acceptance. The increasing popularity of the short, 31-gauge pen needle is a notable example.24 However, smaller needles are not suitable for all applications. For example, rapid delivery of large volumes and administration of formulations with large particulates require larger needles. Furthermore, scaling down needle length also prevents injection into deeper tissues. Microneedles are just long enough to deliver into the skin, which may be an advantage in some scenarios, but is a drawback in others. Moreover, as needle size approaches the dimensions of skin surface topography and mechanical deformation, microneedle insertion into the skin becomes more difficult and may, in some cases, require specialized insertion devices.25,26 Thus, there is a trade-off between pain and other delivery considerations when smaller needles are used. The correct balance must be obtained for each application. Based on current literature and applications, delivery of vaccines and protein biotherapeutics appears to be most suitable to benefit from the use of smaller needles.

Needle-Free Delivery Methods

In some cases, the limitations of hypodermic needles can be addressed by eliminating the needle altogether. However, these needle-free alternatives each have limitations of their own. For example, jet injectors accelerate liquid droplets across the skin at high velocity and are used clinically to administer insulin, vaccines, and other drugs, but have had limited impact because of their size, cost, and inability to reduce pain and injury.27 Transdermal patches have also been developed to passively deliver drugs across the skin, but this approach has been limited to hydrophobic and small molecules.17 Skin pretreatment methods such as ultrasound, electric fields, solid microneedles, and thermal ablation are being investigated to increase the permeability of skin for protein and vaccine patches.17,28 New approaches, such as pulmonary, oral, and nasal delivery routes, are increasingly being studied for the systemic delivery of compounds that currently require injections.29 Notably, pulmonary delivery of insulin (Exubera®, Pfizer, Groton, CT) is already approved by the Food and Drug Administration.30

Conclusion

In conclusion, smaller needles can reduce pain and provide other advantages that can increase patient compliance. Fine needles of 33–31 gauge have already gained clinical acceptance and still smaller microneedles are under development. However, smaller needles are not suitable for all applications and, in some cases, needle-free delivery systems provide useful alternatives.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr. Young Bin Choy and Jeong Woo Lee at Georgia Tech, Dr. Kyuzi Kamoi at Nagaoka Red Cross Hospital, and Dr. John Mikszta at BD Technologies for providing images of the needles shown in Figure 1. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health. Mark Prausnitz is the Emerson-Lewis Faculty Fellow at Georgia Tech.

References

- 1.Kravetz RE. Hypodermic syringe. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Dec;100(12):2614–2615. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauri A, Armstrong G, Hutin Y. The global burden of disease attributable to contaminated injections given in health care settings. Int J STD AIDS. 2004 Jan;15(1):7–16. doi: 10.1258/095646204322637182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindh WQ. Delmar's comprehensive medical assisting: administrative and clinical competencies. Albany (NY): Delmar Health Care Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroger A, Atkinson W, Marcuse E, Pickering L. MMWR Recomm Rep. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) 55(RR-15) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz S, Hassman D, Shelmet J, Sievers R, Weinstein R, Liang J, Lyness W. A multicenter, open-label, randomized, two-period crossover trial comparing glycemic control, satisfaction, and preference achieved with a 31 gauge × 6 mm needle versus a 29 gauge × 12.7 mm needle in obese patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2004 Oct;26(10):1663–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deacon B, Abramowitz J. Fear of needles and vasovagal reactions among phlebotomy patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20(7):946–960. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanas R. Reducing injection pain in children and adolescents with diabetes: a review of indwelling catheters. Pediatr Diabetes. 2004 Jun;5(2):102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2004.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berlin I, Bisserbe JC, Eiber R, Balssa N, Sachon C, Bosquet F, Grimaldi A. Phobic symptoms, particularly the fear of blood and injury, are associated with poor glycemic control in type I diabetic adults. Diabetes Care. 1997 Feb;20(2):176–178. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arendt-Nielsen L, Egekvist H, Bjerring P. Pain following controlled cutaneous insertion of needles with different diameters. Somatosens Mot Res. 2006 Mar–Jun;23(1–2):37–43. doi: 10.1080/08990220600700925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egekvist H, Bjerring P, Arendt-Nielsen L. Pain and mechanical injury of human skin following needle insertions. Eur J Pain. 1999 Mar;3(1):41–49. doi: 10.1053/eujp.1998.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egekvist H, Bjerring P, Arendt-Nielsen L. Regional variations in pain to controlled mechanical skin traumas from automatic needle insertions and relations to ultrasonography. Skin Res Technol. 1999:247–254. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider LW, Peck LS, Melvin JW. Phase I (Appendices B-E) Ann Arbor, MI: Highway Safety Research Institute; 1978. Penetration characteristics of hypodermic needles in skin and muscle tissue. Final report. Persistent URL http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/614. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyakoshi M, Kamoi K, Iwanaga M, Hoshiyama A, Yamada A. Comparison of patient's preference, pain perception, and usability between Micro Fine Plus® 31-gauge needle and microtapered NanoPass® 33-gauge needle for insulin therapy. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1(5):718–724. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alarcon JB, Hartley AW, Harvey NG, Mikszta JA. Preclinical evaluation of microneedle technology for intradermal delivery of influenza vaccines. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007 Apr;14(4):375–381. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00387-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikszta JA, Sullivan VJ, Dean C, Waterston AM, Alarcon JB, Dekker JP, 3rd, Brittingham JM, Huang J, Hwang CR, Ferriter M, Jiang G, Mar K, Saikh KU, Stiles BG, Roy CJ, Ulrich RG, Harvey NG. Protective immunization against inhalational anthrax: a comparison of minimally invasive delivery platforms. J Infect Dis. 2005 Jan 15;191(2):278–288. doi: 10.1086/426865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braverman IM. The cutaneous microcirculation. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 2000;5:3–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2000.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prausnitz MR, Mitragotri S, Langer R. Current status and future potential of transdermal drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004 Feb;3(2):115–124. doi: 10.1038/nrd1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prausnitz M, Mikszta J, Microneedles Raeder-Devens J. In: Percutaneous penetration enhancers. Smith EW, Maibach HI, editors. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2005. pp. 239–255. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis SP, Martanto W, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR. Hollow metal microneedles for insulin delivery to diabetic rats. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2005 May;52(5):909–915. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.845240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardeniers HJGE, Luttge R, Berenschot EJW, De Boer MJ, Yeshurun SY, Hefetz M, Van't Oever R, Van Den Berg A. Silicon micromachined hollow microneedles for transdermal liquid transport. J MEMS. 2003;12:855–862. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordquist L, Roxhed N, Griss P, Stemme G. Novel microneedle patches for active insulin delivery are efficient in maintaining glycaemic control: an initial comparison with subcutaneous administration. Pharm Res. 2007 Jul;24(7):1381–1388. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta J, Felner E, Prausnitz MR. Microneedles for minimally invasive transdermal insulin delivery: an in vivo study in human diabetic subjects. Proceedings of the 6th Annual Diabetes Technology Meeting.2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaushik S, Hord AH, Denson DD, McAllister DV, Smitra S, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR. Lack of pain associated with microfabricated microneedles. Anesth Analg. 2001 Feb;92(2):502–504. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200102000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohannon NJ. Insulin delivery using pen devices. Simple-to-use tools may help young and old alike. 1999 Oct 15;106(5):57–64. doi: 10.3810/pgm.1999.10.15.751. Postgrad Med. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis SP, Landis BJ, Adams ZH, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR. Insertion of microneedles into skmeasurement and prediction of insertion force and needle fracture force. J Biomech. 2004 Aug;37(8):1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang M, Zahn JD. Microneedle insertion force reduction using vibratory actuation. Biomed Microdevices. 2004 Sep;6(3):177–182. doi: 10.1023/B:BMMD.0000042046.07678.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitragotri S. Current status and future prospects of needle-free liquid jet injectors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006 Jul;5(7):543–548. doi: 10.1038/nrd2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cross SE, Roberts MS. Physical enhancement of transdermal drug application: is delivery technology keeping up with pharmaceutical development? Curr Drug Deliv. 2004 Jan;1(1):81–92. doi: 10.2174/1567201043480045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Touitou E, Barry BW, editors. Enhancement in drug delivery. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jani R, Triplitt C, Reasner C, Defronzo RA. First approved inhaled insulin therapy for diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2007 Jan;4(1):63–76. doi: 10.1517/17425247.4.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]