Abstract

Background

Advancements in subcutaneous continuous glucose monitoring and subcutaneous insulin delivery are stimulating the development of a minimally invasive artificial pancreas that facilitates optimal glycemic regulation in diabetes. The key component of such a system is the blood glucose controller for which different design strategies have been investigated in the literature. In order to evaluate and compare the efficacy of the various algorithms, several performance indices have been proposed.

Methods

A new tool—control-variability grid analysis (CVGA)—for measuring the quality of closed-loop glucose control on a group of subjects is introduced. It is a method for visualization of the extreme glucose excursions caused by a control algorithm in a group of subjects, with each subject presented by one data point for any given observation period. A numeric assessment of the overall level of glucose regulation in the population is given by the summary outcome of the CVGA.

Results

It has been shown that CVGA has multiple uses: comparison of different patients over a given time period, of the same patient over different time periods, of different control laws, and of different tuning of the same controller on the same population.

Conclusions

Control-variability grid analysis provides a summary of the quality of glycemic regulation for a population of subjects and is complementary to measures such as area under the curve or low/high blood glucose indices, which characterize a single glucose trajectory for a single subject.

Keywords: artificial pancreas, control-variability grid analysis, diabetes, model predictive control, simulation, virtual patients

Introduction

Closed-loop glucose regulation for maintaining normoglycemia in type 1 diabetes mellitus has been investigated and discussed since the 1970s.1–3 Recent technological advancements in subcutaneous continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) allowed the observation of temporal glucose fluctuations in real time and the use of these data for feedback control of blood glucose (BG) fluctuations via subcutaneous insulin delivery systems.4–8 However, the availability of innovative sensors and actuators, although essential, does not guarantee the achievement of optimal glycemic regulation under all conditions—closed-loop control of blood glucose levels poses significant technological challenges to the automatic control expert.

Several outcome measures have been proposed to judge the effectiveness of closed-loop control in a single patient.9–12 However, there are no instruments able to assess the overall performance in a group of patients, e.g., to compare the performances of different closed-loop controllers and/or different tuning choices for a given controller.

The necessity of a population index stems from the increase of the number of closed-loop clinical experiments along with the availability of large-scale simulation models (see, e.g., Dalla Man and colleagues13,14) that allow the generation of hundreds of virtual patients. In fact, in silico trials are perhaps the best way to address the robustness of the artificial pancreas against interindividual variability prior to conducting in vivo clinical trials. The availability of realistic individual models is the basis for conducting an in silico trial: the control can be individually tuned and then tested on each virtual patient, possibly injecting disturbances and uncertainties in order to assess the robustness of closed-loop control.

In this article, a new tool for measuring the quality of closed-loop glucose control on a group of subjects is proposed: the control-variability grid analysis (CVGA). It is a method for visualization of the extreme glucose excursions caused by a control algorithm in a group of subjects, with each subject presented by one data point for any given observation period. This differentiates the analysis from any other standard statistics, such as mean and standard deviation, which do not provide population-based visualization of data. Following the ideas of traditional Clarke error-grid analysis used for evaluation of the accuracy of self-monitoring15 or CGM devices,16 nine rectangular zones are introduced in order to classify subjects into categories. The use of CVGA is illustrated by comparing the performances of the model predictive control (MPC) scheme and the proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller described in Magni et al.

Control-Variability Grid Analysis

Control variability grid analysis is a graphical representation of minimum/maximum glucose values in a population of patients either real or virtual. CVGA provides a simultaneous visual and numerical assessment of the overall quality of glycemic regulation in the entire population of (simulated or real) patients. As such, it may play an important role in the tuning of closed-loop glucose control algorithms and also in the comparison of their performance.

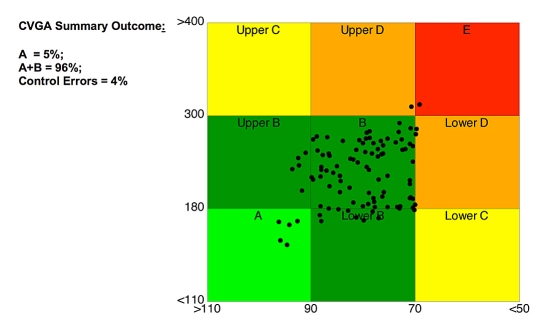

Assuming that for each subject a time series of measured BG values over a specified time period (e.g., 1 day) is available, CVGA is obtained as follows: For each subject a point is plotted with an X coordinate—minimum BG—and a Y coordinate—maximum BG—within the considered time period (see Figure 1). Note that the X axis is reversed as it goes from 110 mg/dl (left) to 50 mg/dl (right) so that optimal regulation is located in the lower left corner. The appearance of the overall plot is a cloud of points located in different regions of the X-Y plane that can be associated with different qualities of glycemic regulation. In order to classify subjects into categories, nine rectangular zones are defined as follows:

Figure 1.

Control variability grid analysis: each point represents the extreme value of a patient over the considered time period.

| A | Accurate control: X range 110–90 mg/dl and Y range 110–180 mg/dl |

| Lower B | Benign deviations into hypoglycemia: X = 90–70 mg/dl, Y = 110–180 mg/dl |

| B | Benign control deviations: X = 90–70 mg/dl and Y = 180–300 mg/dl |

| Upper B | Benign deviations into hyperglycemia: X = 110–90 mg/dl, Y = 180–300 mg/dl |

| Lower C | Over-Correction of hyperglycemia: X < 70 mg/dl, Y = 110–180 mg/dl |

| Upper C | Over-Correction of hypoglycemia: X = 110–90 mg/dl, Y > 300 mg/dl |

| Lower D | Failure to Deal with hypoglycemia: X < 70 mg/dl, Y = 180–300 mg/dl |

| Upper D | Failure to Deal with hyperglycemia: X = 90–70 mg/dl, Y > 300 mg/dl |

| E | Erroneous control: X < 70 mg/dl and Y > 300 mg/dl. |

The boundaries of the zones were chosen as follows: 70–180 mg/dl are the commonly accepted limits of a target range, with readings below 70 mg/dl identified as hypoglycemia and readings above 180 mg/dl defined as hyperglycemia. The lower value of 90 mg/dl for zone A is selected as a minimal safe value that a controller can maintain to avoid risking induced hypoglycemia; 300 mg/dl is the upper value of permissible hyperglycemic excursions derived from discussions with physicians. As indicated by established methods for risk analysis of glucose data, zone A is the safest region of CVGA. Various aspects of this notion are discussed elsewhere.9–12

A numeric assessment of the overall level of glucose regulation in the population is given by the summary outcome of CVGA (see Figure 1), which provides the percentage of points falling in the three macrozones: (1) A-one, (2) A+B zones, and (3) C+D+E zones. The percentage of points falling in a particular zone can be provided in order to distinguish between overcorrection of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. Note that if a linear scale was used for both X and Y axes, the zones would be rectangular. In order to obtain square zones of equal size, a simple nonlinear transformation is used.

Being based on the minimum and the maximum among noisy samples, CVGA may be sensitive to noise and statistical outliers. Thus, if sensor noise (observed or computer simulated) is present in data submitted to CVGA, it is recommended that the lower bound of CVGA be at 2.5% of the distribution of data and the upper bound be at 97.5%. This way, the difference Y-X coordinates of each data point would be the 95% confidence interval of a patient's data. Having lower/ upper bounds fixed at distribution percentiles instead at the absolute minimum/maximum of data reduces the vulnerability of the analysis to outliers.

Three main uses of CVGA are possible. First, one could plot points corresponding to different patients over a given time period, typically 24 hours (see Figure 1). In this way, a visually effective global characterization of the population is obtained. A second use of CVGA is to plot points but under different conditions. For instance, in a several day study, each point could correspond to a single day, allowing the tracking of a subject over time. Another example is comparison of the performances of different closed-loop controllers and/or different tuning choices for a given controller. Finally, it is also possible to consider CVGA plots with several points for each patient; see, e.g., Figures 3 and 4, where different tuning choices (Figure 3) and different controllers (Figure 4) are compared on the same population.

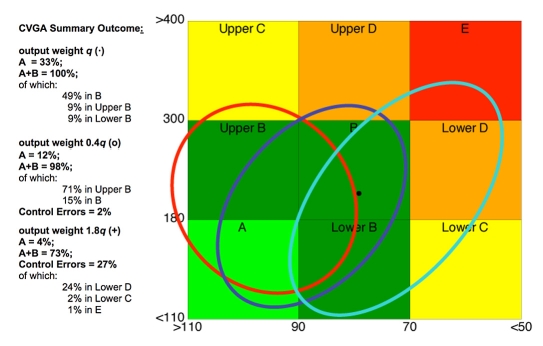

Figure 3.

CVGA for MPC control with output weight q (dots), output weight 0.4q (open circles), and output weight 1.8q (pluses).

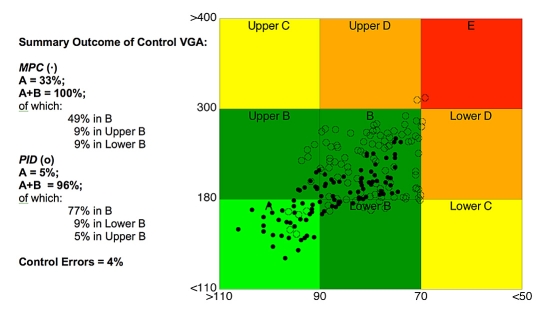

Figure 4.

CVGA for patients controlled by means of MPC (dots) and PID control (open circles); see Magni et al.17 for details.

In Silico Trial Evaluated by CVGA

Simulator and Virtual Patient Generation

A major problem for the artificial pancreas is guaranteeing satisfactory performance under conditions of metabolic disturbance and inter- and intraindividual variability. In that regard, in silico testing via large-scale computer simulation models is very useful. The drawback of such models is the difficulty of identifying all relevant parameters from plasma concentration measurements. A triple tracer meal protocol18 on 204 nondiabetic individuals and several other experiments in different age groups allowed the development of a new generation in silico model of the glucose-insulin system.13,14 Using data from these experiments it was possible not only to identify the mean values but also the joint distribution of the model parameters. As a result, individual models of virtual patients have been extracted and implemented in a comprehensive simulation environment.

Virtual Protocol

The performance of closed-loop glucose control is tested on a 4-day virtual protocol:

the simulation starts at basal value and the first meal is dinner at 7:30 p.m. of day 1; the patient has breakfast at 9:30 a.m. with 45 grams of carbohydrate, lunch at 1:30 p.m. with 75 grams of glucose, and dinner at 7:30 p.m. with 85 grams of carbohydrate;

in the first part of the simulation, the virtual “patient ” receives a subcutaneous bolus based on an open-loop strategy. At 9:30 p.m. of day 2 the controller is initiated. Thereafter, the piecewise constant insulin delivery is governed by the closed-loop controller and no further bolus is administrated.

The virtual protocol has been designed to approximate a realistic clinical trial conducted on real patients. In particular, the first open-loop phase serves as an observation window during which individual patient information may be collected. The insulin delivery during closed-loop control is piecewise constant and is updated every 30 minutes. Shorter sampling intervals are technologically feasible, but would require overly intensive medical supervision in the first clinical trials.

In order not to consider the transition from open- to closed-loop regulation, the indices are computed after 8:00 a.m. of day 3.

Control Laws

Closed-loop control has been designed accordingly to the linear model predictive control law described in Magni et al.17 The MPC control law is based on the solution of a finite horizon optimal control problem, where a cost function is minimized with respect to the external insulin rate depending on the state dynamics of a model of the system.

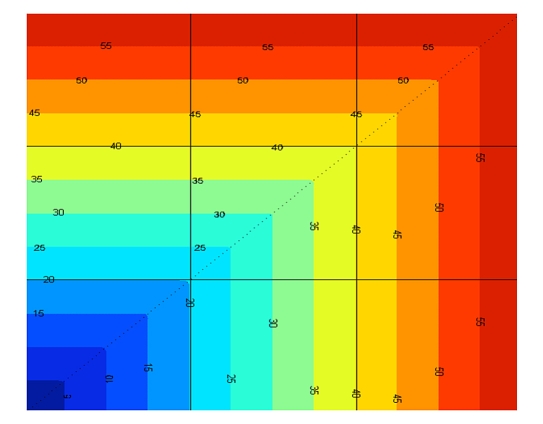

The MPC, in general, has several independent tuning parameters: control and prediction horizon, output and input weights, and terminal penalty. However, as discussed elsewhere,17 the main advantage of the proposed algorithm is the possibility of achieving satisfactory results by tuning only one parameter (the output weight q) in a quite straightforward and intuitive way. In order to obtain an automatic tuning procedure, we introduce cost on the CVGA grid (see Figure 2). With a trial-and-error procedure, the CVGA costs corresponding to different values of the parameter q are compared and the value associated with the lowest cost is chosen. Herein, the MPC control law is compared with a PID control law with a feed-forward action as described in Magni et al.17 In this case, most of the parameters have been chosen in a standard way based on the mean linearized model and only the gain has been adapted to each virtual patient. The value of the gain has been obtained using a trial-and-error procedure similar to the optimization of the parameter q of the MPC.

Figure 2.

Cost associated with each point of CVGA. The level lines are squared following the shape of the CVGA zones.

In Silico Trial Results

The trial was conducted on 100 virtual subjects.

Optimal tuning. An MPC control law was synthesized with an individually tuned q. CVGA is reported in Figure 3 (dots). The CVGA summary outcome is A = 33%, A+B = 100%, of which 9% is in upper B, 49% is in B, and 9% is in lower B.

Overcorrection of hypoglycemia. In order to show the utility of CVGA to compare different choices of the parameter q, the trial was repeated with q′ = 0.4q. CVGA is reported in Figure 3 (open circles). The CVGA summary outcome is A = 12%, A+B = 98%, of which 71% is in upper B, 15% is in B, and C+D+E = 2%. This shows a general overcorrection of hypoglycemia that is due to a less aggressive control law using a lower insulin infusion rate.

Overcorrection of hyperglycemia. The CVGA obtained with a more aggressive controller with q″= 1.8q is reported in Figure 3 (pluses). The CVGA summary outcome is A = 4%, A+B = 73%, C+D+E = 27%, of which 23% is in lower D, 2% is in lower C, and 1% is in E. This shows a general overcorrection of hyperglycemia due to a more aggressive control law that uses higher insulin infusion rates.

Comparison of different control strategies. In Figure 4, CVGA is used to compare the performances of MPC vs PID control described in Magni et al.17 The CVGA summary outcome for MPC is A = 33%, A+B = 100%, of which 9% is in upper B, 49% is in B, and 9% is in lower B. The CVGA summary outcome for PID is A = 5%, A+B = 96%, of which 5% is in upper B, 77% is in B, 9% is in lower B, and C+D+E = 4%. In this example, CVGA provides an easy and immediate visual comparison of the effectiveness of two control strategies applied on a population.

Conclusions

In silico and clinical trials produce a wealth of data, whose analysis and interpretation pose nontrivial challenges. CVGA provides a summary of the quality of glycemic regulation for a population of subjects and is complementary to measures such as area under the curve or low/high BG indices, which characterize a single glucose trajectory for a single subject. An advantage of the proposed tool is that, in addition to being visually effective, it also gives appropriate numerical indices. As a result, CVGA could be extremely useful in the development of tuning procedures for the parameters of closed-loop controllers.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Artificial Pancreas Project at the University of Virginia.

Abbreviations

- BG

blood glucose

- CGM

continuous glucose monitoring

- CVGA

control-variability grid analysis

- MPC

model predictive control

- PID

proportional-integral-derivative

Appendix

Herein, the MATLAB19 commands to generate control variability grid analysis are given. Suppose that G is a matrix containing glucose profile data of a different patient in each row.

Percentile calculation and polynomial transformation for each patient

for i=1: size(G,1) Min_gli(i) = prctile(G(i,:),2.5); Max_gli(i) = prctile(G(i,:),97.5); end p=polyfit([110 180 300 400],[0 20 40 60],3); Max_gli = polyval(p,Max_gli);

CVGAplot

figure

hold on

%fill zone C-

X_pcmeno = [40 60 60 40]; Y_pcmeno = [0 0 20 20]; fill(X_pcmeno,Y_pcmeno,[l 1 0]);

fofill zone D-

X_pdmeno = [40 60 60 40]; Y_pdmeno = [20 20 40 40]; fill(X_pdmeno,Y_pdmeno,[l 0.6 0]);

fofill zone E

X_pe = [40 60 60 40]; Y_pe = [40 40 60 60]; fill(X_pe,Y_pe,[l 0 0]);

fofill zone B-

X_pbmeno = [20 40 40 20]; Y_pbmeno = [0 0 20 20]; fill(X_pbmeno,Y_pbmeno,[7/255 135/255 0/255]);

%fill zone C

X_pc = [20 40 40 20]; Y_pc = [20 20 40 40]; fill(X_pc,Y_pc,[7/255 135/255 0/255]);

fofill zone D+

X_pdpiu = [20 40 40 20]; Y_pdpiu = [40 40 60 60]; fill(X_pdpiu,Y_pdpiu,[l 0.6 0]);

%fill zone A

X_pa = [0 20 20 0]; Y_pa = [0 0 20 20]; fill(X_pa,Y_pa,[0 1 0]);

fofill zone B+

X_pbpiu = [0 20 20 0]; Y_pbpiu = [20 20 40 40]; fill(X_pbpiu,Y_pbpiu,[7/255 135/255 0/255]);

fofill zone C+

X_pcpiu = [0 20 20 0]; Y_pcpiu = [40 40 60 60]; fill(X_pcpiu,Y_pcpiu,[l 1 0]);

text(10,10,’\textbf﹛A﹜’,’HorizontalAlignment’,’center','Interpreter’,’Latex’,’Fontsize',15);

text(10,30,’\textbf﹛Upper B﹜’,’HorizontalAlignment’,’center’,’Interpreter’,’Latex’ ,’Fontsize',15);

text(10,50,’\textbf﹛Upper C﹜’,’HorizontalAlignment’,’center’,’Interpreter’,’Latex’ ,’Fontsize',15);

text(30,10,’\textbf﹛Lower B﹜','HorizontalAlignment','center','Interpreter','Latex’ ,’Fontsize',15);

text(30,30,'\textbf﹛B﹜','HorizontalAlignment','center','Interpreter','Latex’ ,’Fontsize',15);

text(30,50,’\textbf﹛Upper D﹜','HorizontalAlignment','center','Interpreter','Latex’ ,’Fontsize',15);

text(50,10,’\textbf﹛Lower C﹜','HorizontalAlignment','center','Interpreter','Latex’ ,’Fontsize',15);

text(50,30,’\textbf﹛Lower D﹜','HorizontalAlignment','center','Interpreter','Latex’ ,’Fontsize',15);

text(50,50,'\textbf﹛E﹜','HorizontalAlignment','center','Interpreter','Latex’ ,’Fontsize',15);

set(gca,’YTick',[0 20 40 60])

set(gca,’XTick',[0 20 40 60])

set(gca,’XTickLabel',﹛'>110’ ‘90’ ‘70’ ‘<50'﹜)

set(gca,’YTickLabel',﹛'<110’ ‘180’ ‘300’ ‘>400'﹜)

scatter(min(max(110 - Min_gli,0),60),min(max(Max_gli,0),60)/ow','filled');

xlabel('Minimum BG'),ylabel('Maximum BG')

grid on

box on

References

- 1.Albisser AM, Leibel BS, Ewart TG, Davidovac Z, Botz CK, Zingg W. An artificial endocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 1974;23(5):389–396. doi: 10.2337/diab.23.5.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clemens AH, Chang PH, Myers RW. The development of Biostator, a Glucose Controlled Insulin Infusion System (GCIIS) Horm Metab Res. 1977;(Suppl 7):23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bequette BW. A critical assessment of algorithms and challenges in the development of a closed-loop artificial pancreas. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2005;7(1):28–47. doi: 10.1089/dia.2005.7.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hovorka R. Continuous glucose monitoring and closed-loop systems. Diabet Med. 2005;23(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klonoff DC. The artificial pancreas: how sweet engineering will solve bitter problems. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1(1):72–81. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hovorka R, Chassin LJ, Wilinska ME, Canonico V, Akwi JA, Federici MO, Massi-Benedetti M, Hutzli I, Zaugg C, Kaufmann H, Both M, Vering T, Schaller HC, Schaupp L, Bodenlenz M, Pieber TR. Closing the loop: the Adicol experience. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2004;6(3):307–318. doi: 10.1089/152091504774197990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steil GM, Rebrin K, Darwin C, Hariri F, Saad MF. Feasibility of automating insulin delivery for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55(12):3344–3350. doi: 10.2337/db06-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinzimer S. Closed-loop artificial pancreas: feasibility studies in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes. Proc. 6th Diabetes Technology Meeting; 2006. p. S55. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovatchev BP, Straume M, Cox DJ, Farhi LS. Risk analysis of blood glucose data: a quantitative approach to optimizing the control of insulin dependent diabetes. J Theor Med. 2001;3:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovatchev BP, Cox DJ, Gonder-Frederick L, Clarke WL. Methods for quantifying self-monitoring blood glucose profiles exemplified by an examination of blood glucose patterns in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2002;4(3):295–303. doi: 10.1089/152091502760098438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovatchev BP, Cox DJ, Kumar A, Gonder-Frederick L, Clarke WL. Algorithmic evaluation of metabolic control and risk of severe hypoglycemia in type 1 and type 2 diabetes using self-monitoring blood glucose data. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2003;5(5):817–828. doi: 10.1089/152091503322527021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovatchev BP, Clarke WL, Breton M, Brayman K, McCall A. Quantifying temporal glucose variability in diabetes via continuous glucose monitoring: mathematical methods and clinical application. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2005;7(6):849–862. doi: 10.1089/dia.2005.7.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalla Man C, Rizza RA, Cobelli C. Meal simulation model of the glucose-insulin system. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54(10):1740–1749. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.893506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalla Man C, Raimondo DM, Rizza RA, Cobelli C. GIM. simulation software of meal glucose-insulin model. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1(3):323–330. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke WL, Cox DJ, Gonder-Frederick LA, Carter WR, Pohl SL. Evaluating clinical accuracy of systems for self-monitoring of blood glucose. Diabetes Care. 1987;10(5):622–628. doi: 10.2337/diacare.10.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovatchev BP, Gonder-Frederick LA, Cox DJ, Clarke WL. Evaluating the accuracy of continuous glucose-monitoring sensors: continuous glucose-error grid analysis illustrated by TheraSense Freestyle Navigator data. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(8):1922–1928. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.8.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magni L, Raimondo DM, Bossi L, Dalla Man C, De Nicolao G, Kovatchev BP, Cobelli C. Model predictive control of type 1 diabetes: an in silico trial. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1(6):804–812. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basu R, Dalla Man C, Campioni M, Basu A, Klee G, Jenkins G, Toffolo G, Cobelli C, Rizza RA. Mechanisms of postprandial hyperglycemia in elderly men and women: gender specific differences in insulin secretion and action. Diabetes. 2006;55:2001–2014. doi: 10.2337/db05-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The MathWorks. MATLAB user's guide. Natick, MA: The MathWorks Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]