Abstract

TrkB is an important receptor for brain-derived neurotrophic factor and NT4, members of the neurotrophin family. TrkB signaling is crucial in many activity-dependent and activity-independent processes of neural development. Here, we investigate the role of trkB signaling in the development of two distinct, organizational features of retinal projections—the segregation of crossed and uncrossed retinal inputs along the “lines of projection” that represent a single point in the visual field and the “retinotopic” mapping of retinofugal axons within their cerebral targets. Using anterograde tracing, we obtained quantitative measures of the distribution of retinal projections in the dorsal nucleus of the lateral geniculate body (LGd) and superior colliculus (SC) of wild-type mice and mice homozygous for constitutive null mutation (knock-out) of the full-length trkB receptor . In mice, uncrossed retinal projections cluster normally but there is a topographic expansion in the distribution of these clusters across the SC. By contrast, the absence of trkB signaling has no significant effect on the segregation of crossed and uncrossed retinal projections along the lines of projection in LGd or SC. We conclude that the normal topographic organization of uncrossed retinal projections depends upon trkB signaling, whereas the segregation of crossed and uncrossed retinal projections is trkB-independent. We also found that in mice, neuronal number was reduced in the LGd and SC and in the caudate-putamen. Previous studies by ourselves and others have shown that the number of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) is unchanged in mice. Together, these results demonstrate that there is no matching of the numbers of RGCs with neuronal numbers in the LGd or SC.

Keywords: Lateral geniculate nucleus, Superior colliculus, Neurotrophin, Visual system

Introduction

Elucidation of the cellular mechanisms that contribute to the ontogeny of orderly neural connections is a major theme of developmental neurobiology. Retinal projections have been a widely used experimental system for studies of this issue. In mammals, the dorsal nucleus of the lateral geniculate body (LGd) and the superior colliculus (SC) are, respectively, the principal thalamic and midbrain targets of the retina. The representation of the two-dimensional visual field is described in three dimensions of both these structures by a “point-to-line” transformation (Kaas et al. 1972; Frost et al. 1979; Frost and Caviness 1980): a point in the visual field is represented along a cylinder of tissue [termed a “line of projection” by neurophysiologists (Bishop et al. 1962)] that extends into the LGd or SC from its surface. Neighboring points in the visual field are represented within adjacent cylinders of tissue. This arrangement produces retinotopic maps of the visual field on the surface of each structure. In mature animals, within the representation of the binocular region of the visual field, inputs from the two eyes are segregated in non-overlapping zones along the lines of projection (Rakic 1977; Frost et al. 1979; Godement et al. 1984; Shatz and Kirkwood 1984; Reese 1986).

Ontogenetically, the mature mammalian pattern of retinal projections arises from a less distinct one. In both the LGd (Hubel et al. 1977; Rakic 1977; Frost et al. 1979; Bunt et al. 1983; Shatz 1983; Godement et al. 1984) and the SC (Frost et al. 1979; Land and Lund 1979; Godement et al. 1984), axons originating in the contralateral and the ipsilateral eyes, though biased toward their appropriate termination zones at the one or the other end of the lines of projection, initially overlap and progressively segregate. The retinotopic organization of both crossed (O’Leary et al. 1986; Simon and O’Leary 1990; Jhaveri et al. 1991; Hindges et al. 2002) and uncrossed (Frost et al. 1979; Land and Lund 1979; Cowan et al. 1984; Frost 1984; Godement et al. 1984; Insausti et al. 1985; Woo et al. 1985) retinocollicular axons is also progressively refined from an initially less focused pattern. The progressive topographic focusing of retinal projections occurs by a combination of axonal pruning and directed axonal growth (Sretavan and Shatz 1986; Simon and O’Leary 1990; Bhide and Frost 1991; Jhaveri et al. 1991). Elimination of inappropriately projecting retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) can also contribute to the topographic focusing of crossed (O’Leary et al. 1986) and uncrossed (Cowan et al. 1984; Insausti et al. 1984) retinal projections.

The emergence of eye-specific segregation is activity-dependent in both the LGd and SC (Shatz and Stryker 1988; Sretavan et al. 1988; Rossi et al. 2001; Muir-Robinson et al. 2002). At least in the SC, the topographic focusing of crossed (Simon et al. 1992; McLaughlin et al. 2003) and uncrossed (Cowan et al. 1984; Thompson and Holt 1989) retinal projections is also activity-dependent. The sets of cellular mechanisms by which electrical activity contributes to ocular segregation and retinotopic organization could be different but overlapping. For example, NMDA receptor signaling appears to contribute to the emergence of retinotopic order (Simon et al. 1992) but not to ocular segregation (Smetters et al. 1994). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)/trkB signaling is an important mediator of many activity-dependent processes (Poo 2001; Ernfors and Bramham 2003). In order to assess the contribution of trkB signaling to retinotopic order and ocular segregation, we examined these two features in mice that are homozygous for null mutation (knockout) of the full-length trkB receptor . We found that in the absence of trkB signaling, the topographic distribution of uncrossed retino-SC projections is altered but ocular segregation is normal in LGd and SC. Thus, the topographic organization of uncrossed retinal projections appears to be determined by mechanisms that depend on trkB receptor signaling, whereas the segregation of crossed and uncrossed retinal projections is trkB independent.

Methods

Experimental subjects

The constitutive null mutation of trkB used in this study affects full length, but not truncated, trkB (Klein et al. 1993). WT mice and mice heterozygous for trkBFL null mutation , both on a hybrid C57Bl6/129 background, were purchased for use as breeders from Jackson Laboratories (catalog numbers JR101045 and 002544, respectively). The and WT mice used in this study of retinal projections were obtained by mating of breeding pairs. Although most homozygous mice of the original trkB null mutant line, on a C57Bl/6 background, died by the end of the first postnatal week (Klein et al. 1993), a significant fraction of the hybrid line that we used survive to postnatal days 12–13 (see the Jackson Laboratories specification sheet at http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/002544.html), allowing us to study their retinal projections at this relatively advanced stage of development (see “Discussion”). All procedures were performed blind to genotype.

Tracing of retinal projections

On postnatal day 10 or 11 (P10 or P11; P0 = day of birth), the mice were anesthetized by inhalation of Fluothane (ca. 2% in oxygen) and given bilateral intraocular injections of fluorescent-labeled cholera toxin B (CTB; Molecular Probes; 1% in a solution of 2% DMSO in distilled water; 1 µl/eye). Green fluorescent (Alexa 488 labeled) CTB was injected into one eye and red fluorescent (Alexa 546 labeled) CTB was injected into the opposite eye, using a transcorneal approach. Two days later, the mice were deeply anesthetized with Nembutal (60 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with 0.9% NaCl in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in the same buffer. The brains were then cryoprotected by immersion in 30% sucrose buffer at 4°C.

Histology

The brains were frozen in dry ice and cut frozen in the coronal plane on a cryostat at 40 µm. Sections were mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Thermofisher). A one in four series of sections was cover slipped using Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech) and reserved for confocal analyses, providing a 25% sample at a spacing of 160 µm. A second one in four series was stained with cresyl violet and used for the analysis of neuronal numbers and neuronal size.

Confocal microscopy

For each section, using a 10X (NA = 0.3) objective, Z-stacks of 5 µm optical slices were obtained using a Biorad confocal microscope on slow scan with kalman filtering.

Quantitative analysis

Retinal projections

Only cases in which the retinal projections of both eyes were completely labeled were used for quantitative analysis. The completeness of labeling was confirmed by examining the crossed retinal projections to the stratum griseum superficiale (SGS) of the SC, which normally contains a topographic representation of the entire contralateral retina. Any gap in the labeling of the crossed retinal input indicates damage to the contralateral retina or failure of tracer to spread into the corresponding region of the contralateral retina. 6 WT and 6 mice were analyzed quantitatively. Quantitative analysis of the collapsed Z-stack from each section was performed using Image J software (National Institutes of Health).

We performed our quantitative analysis of the segregation of crossed and uncrossed retinal inputs along the lines of projection only in the LGd because the distribution of uncrossed retino-SC projections makes them unsuitable: Uncrossed retino-SC axons project densely to the deep ends of lines of projection in the stratum opticum (SO), but diffusely to the superficial regions in the SGS where crossed retino-SC projections are most dense. Thus, at the resolution of our analysis, even in normal animals, the crossed and uncrossed retino-SC projections largely overlap in their distribution along the lines of projection. At higher levels of resolution the projections do not overlap (Lyckman et al. 2005)—a trivial consequence of the fact that two different axons cannot occupy the same space exactly.

We determined the volume of crossed (VC) and uncrossed (VU) retinogeniculate projections (C and U, respectively, in Fig. 1a) and the total volume of the LGd (VLGd) by measuring the cross-sectional area of the projections and of the LGd as seen in the collapsed Z-stack of each section, adding the measures obtained from all the sections through the LGd and multiplying by the section spacing. We quantified the segregation of crossed and uncrossed retinogeniculate projections by dividing the sum of VC and VU by VLGd[(VC + VU)/VLGd] to derive a segregation index (SI). SI = 1 indicates perfect segregation; SI > 1 indicates overlap; SI < 1 indicates the existence of LGd regions with no retinal projection.

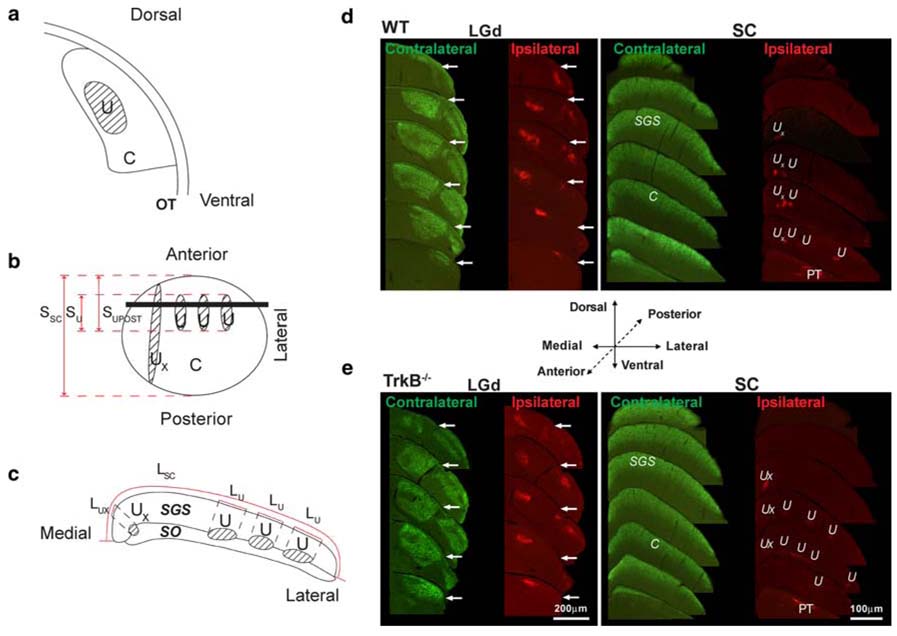

Fig. 1.

Crossed and uncrossed projections in the LGd and SC. a Schematic outline of the LGd as seen in a coronal section, showing the termination regions of the crossed (C: unshaded) and uncrossed (U: shaded) retinal inputs. OT is the optic tract. b Schematic dorsal view of the surface of the entire SC. Terminating crossed retinal inputs (C) are distributed across the entire extent of the SC, principally in the SGS, but also in the stratum opticum (SO). Individually variable, uncrossed retinal inputs (U) terminate in longitudinally oriented patches, principally in the SO but also in the SGS. The medial-most patch (UX) is excluded from our quantitative analysis (see text). SSC, SU and SUPOST indicate, respectively, the anterior–posterior span of the SC, the anterior–posterior span of the quantitatively analyzed, uncrossed retino-SC projections and the span from the anterior tip of the SC to the posterior tip of the uncrossed retino-SC projections. The horizontal line represents the level of a coronal cut through the SC, which is illustrated in frame c. c Schematic outline of the SC as seen in coronal section (perpendicular to the surface view in b). LC and LU are as explained in “Methods”. U and UX are as in b. d Montages of coronal sections (as schematized in a and c) spanning the rostro-caudal extent of the LGd and SC in WT mice. For each panel, crossed projections are labeled in green and uncrossed projections in red. For the LGd, sections are separated by 240 µm, and for the SC, by 360 µm. Arrows in LGd micrographs indicate the border of the LGd with the ventral nucleus of the lateral geniculate body, which also receives retinal input. PT pretectum; other abbreviations are as defined above and in the text. Scale as in e. e Montages of coronal sections spanning the rostro-caudal extent of the LGd and SC in mice. All conventions and abbreviations are as in d. Scale bars LGd 200 µm; SC 100 µm

We performed our quantitative analysis of retinotopic mapping only in the SC because the regionally varying orientation of lines of projection in the LGd and the distance of the uncrossed projections from the surface of the LGd render such an analysis impractical in that structure (Frost and Schneider 1979). Because the rodent SC contains a representation of the entire contralateral retina on its dorsal surface (Drager and Hubel 1976; Frost and Schneider 1979; Godement et al. 1984), the crossed retinal projection was used to define the surface extent of the SC. In the rodent SC, unlike in the LGd, the lines of projection representing a single point in the visual field are in a plane close to the plane of sectioning (Frost and Schneider 1979). This permitted us to perform one-, two- and three-dimensional analyses of the distribution of uncrossed retinal projections within the SC. Our analysis includes the uncrossed retinal projections to the SGS and stratum opticum (SO) that are biased toward the rostrolateral quadrant of the SC [and that lie within the representation of the binocular visual field in normal animals (U in Fig. 1b–e)], but excludes a longitudinally oriented cylinder of projections at the medial edge of the SO that lies outside the representation of the binocular visual field [(UX in Fig. 1b–e); see (Drager 1974; Drager and Hubel 1976; Frost and Schneider 1979; Godement et al. 1984)].

For the one-dimensional analysis, we calculated the anterior–posterior span of the SC (SSC, Fig. 1b) as the number of sections containing the SC multiplied by the section spacing. We calculated the anterior–posterior span of the uncrossed retinal projection (SU, Fig. 1b) as the number of sections containing the uncrossed retino-SC projection multiplied by the section spacing. Similarly, we calculated the span from the anterior tip of the SC to the posterior limit of the uncrossed retinal projection (SUPOST, Fig. 1b).

For the two-dimensional analysis, we measured the surface area of the SC (ASC) by summing, for all sections through the SC, the length of the surface of the SGS as seen in each section (LSC in Fig. 1c) and multiplying by the section spacing. The area of the SC surface that represents the ipsilateral eye (AU) was determined by projecting the borders of the regions containing uncrossed retino-SC projections onto the surface of the SGS, adding, for all sections, the lengths of the segments of the SGS surface onto which the uncrossed projection was projected (sum of the segments labeled LU in Fig. 1c) and multiplying by section spacing.

For the three-dimensional analysis, we measured the volume of the SGS (VSGS) by summing the cross sectional area of the SGS as seen in all sections through the SC and multiplying by section spacing. Similarly, we determined the volume of the uncrossed retino-SC projection (VU) by adding, for all sections, the areas of regions containing uncrossed retino-SC projections (sum of the areas labeled U in Fig. 1c) and multiplying by section spacing. For analysis of SGS thickness, in each section, we measured the thickness of the SGS at the mid point of the medial–lateral extent of the SC and, using ImageJ, averaged across all the sections from each animal to obtain a measure for that animal.

The primary quantitative measurements for each case were average measures for the right and left sides of the brain. We confirmed that data were normally distributed using an equality of variance F-test (Statview) and for each of the measures in LGd and SC, the statistical significance of differences between WT and trkB−/− mice was determined using a two-tailed t-test.

Neuronal number

Using the optical disector method (Coggeshall and Lekan 1996) we estimated the number of neurons in the LGd (n = 4/genotype), SC (n = 5/genotype) and (as a non-visual control structure that also expresses trkB (Merlio et al. 1992; Altar et al. 1994) the caudate-putamen (n = 5/genotype). For every section through each of these structures, we determined neuronal density in three 100 × 100 µm sampling regions and then multiplied the average density within each structure by the total volume of that structure to estimate neuronal number. The samples spanned the dorso-ventral extent of the LGd and caudate-putamen, and the medio-lateral extent of the SC. Neurons were identified using morphological criteria: Nissl stained neurons have round, densely stained profiles that are distinct from astrocytes and oligodendroglia (which have little cytoplasm and lighter nissl staining) and blood vessels (Oorschot 1996).

To ensure that the optical disector method could be accurately employed, we confirmed that neuronal soma size was not significantly different between genotypes by measuring the cross sectional area of neuronal cell bodies in each brain region (LGd, SC and caudate-putamen). Four sections that were randomly distributed through the rostro-caudal extent of each region were photographed at 1000× magnification. The cell body area of 10–20 randomly selected cells was measured from each photograph, using ImageJ image analysis. Areas were averaged for each animal and then for each genotype and values compared using a two-tailed t-test.

Results

Qualitative analysis

The overall pattern of retinal projections is similar in WT and mice (Fig. 1d, e). In the LGd of both genotypes, crossed retinal input fills all of the LGd except for a small region adjoining the medial surface of the LGd (at the deep ends of the lines of projection), which receives uncrossed retinal input. In the SC of both genotypes, the crossed retinal projection terminates densely within all of the SGS except for sectors in the deep 1/3 of the SGS rostrolaterally, where the projection is sparser (Fig. 1d, e). There are also terminating crossed retinal inputs within the SO. As seen in coronal sections, the uncrossed retino-SC projection consists principally of clusters of label that span the interface of the SO and SGS. Occasional, generally sparse patches of label may extend more superficially into the SGS. At most levels of the SC, there is also a dense patch of uncrossed retinal input at the medial extremity of the SO that is not included in our quantitative analysis because it is not included within the representation of the binocular part of the visual field (Drager and Hubel 1976). These findings are consistent with previous reports in rodents (Drager and Hubel 1976; Frost et al. 1979; Land and Lund 1979; Cowan et al. 1984; Frost 1984; Godement et al. 1984; Insausti et al. 1985; Woo et al. 1985).

Quantitative analysis

Topographic analysis in the SC

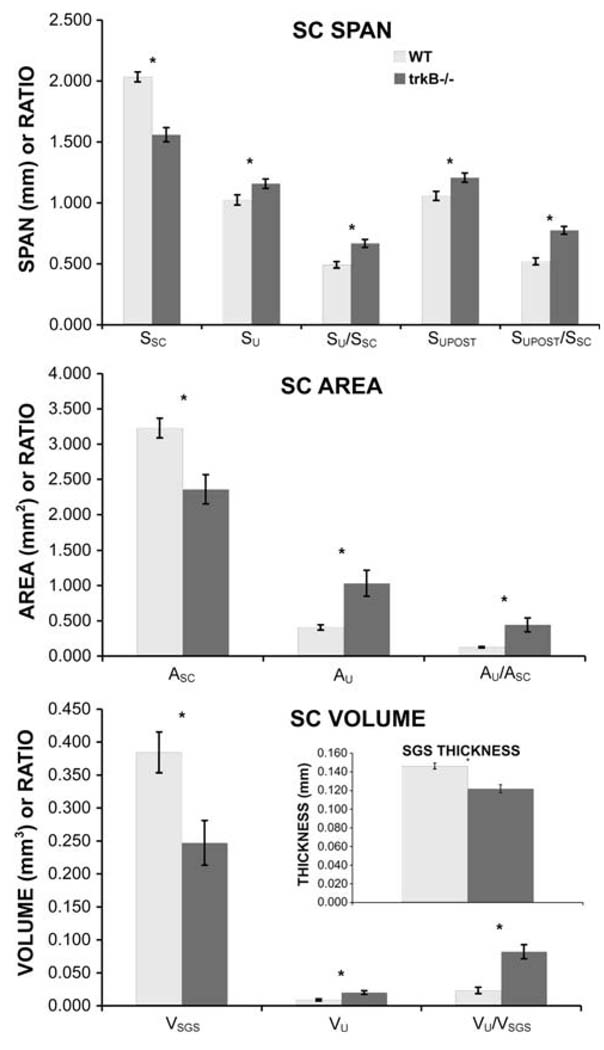

In mice, the anterior–posterior span of the SC (SSC, Fig. 1b) is reduced to 77% of that in WT mice (Fig. 2). Despite this shrinkage, the anterior–posterior span of the uncrossed retino-SC projection (SU, Fig. 1b) increases absolutely by about 13% (Fig. 2). As a consequence of the shrinkage of the SC and the expansion of the uncrossed retino-SC projection, the anterior–posterior span of the uncrossed retino-SC projection as a fraction of the anterior– posterior span of the SC (SU/SSC, Fig. 2) increases from about 49% in WT mice to about 67% in mice, i.e., about 1.4 times the normal value. Similarly, the posterior limit of the uncrossed retinal projection (SUPOST, Fig. 1b) shifts from about 52% of the distance from the anterior to the posterior limit of the SC (SUPOST/SSC, Fig. 2) in WT mice to about 78% of that distance in mice, i.e., 1.5 times the normal value.

Fig. 2.

Anterior–posterior (A–P) spans, surface area and volume of the SC and its crossed and uncrossed retinal inputs. Histograms are group means, error bars are standard deviations. Note that the numerical scale on the Y axes applies both to raw measurements and to ratios (shown on the far right of each histogram), but the dimension does not apply to the ratios. Asterisks indicate that for all measures, the differences between WT and trkB−/− mice are statistically significant (P < 0.0001 for all measures except for SU, for which P = 0.0002). The techniques used to determine all measures are described in the “Methods”. SSC, SU and SUPOST are, respectively, the A–P spans of the SC and the uncrossed retino-SC projection and the distance from the anterior limit of the SC to the posterior limit of the uncrossed retino-SC projection. ASC and AU are, respectively, the surface area of the SC and the area of the uncrossed retinal input as projected onto the surface of the SC. VSGS and VU are, respectively, the volumes of the SGS and the uncrossed retino-SC projection. The inset shows the average thickness of the SGS

The surface area of the SC (ASC) in mice is reduced to 73% of that in WT mice (Fig. 2). Despite this, in mice the absolute area of the representation of the ipsilateral eye on the surface of the SC (AU) is about 2.5-fold that in WT mice (Fig. 2). As a result of these two changes, in mice the percentage of the surface of the SC that receives uncrossed (and crossed) retinal input (AU/ASC, Fig. 2) is about 3.5-fold the percentage in WT mice (44.3 and 12.6%, respectively, Fig. 2). Thus, the percentage of the visual field representation that receives binocular retinal input is enlarged in mice. Because, in mice, the relative surface area of the uncrossed retino-SC projection increases 3.5-fold and the anterior–posterior extent of the projection increases only 1.5-fold, one can calculate that the relative medial–lateral extent of the uncrossed projection is increased (on average, by about 2.3-fold). Taken together, the increased anterior–posterior span and increased surface area of the uncrossed retinal projection in trkB−/− mice suggest a spread of uncrossed retinal inputs into parts of the contralateral visual field representation that normally receive only crossed retinal input.

In mice, the volume of the SGS (VSGS) is reduced to about 64% of the WT value, due to reductions in both its area and the thickness (Fig. 2). Despite this, the volume of the uncrossed retino-SC projection (VU) expands to about 2.2 times the volume in WT mice and the volume of the uncrossed retinal projection as a fraction of the volume of the SGS (VU/VSG) increases from about 2 to 8% (Fig. 2).

Ocular segregation analysis in the LGd

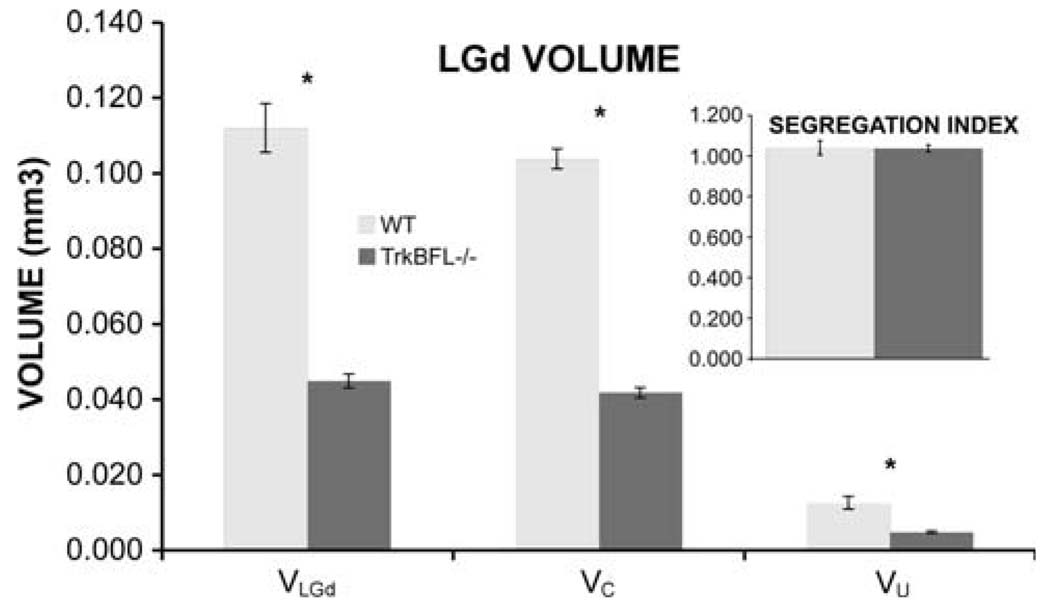

In mice, the volumes of the LGd and of the crossed and uncrossed retinal projections (VLGd, VC and VU, respectively, Fig. 3) are significantly reduced to approximately 40% of the corresponding measures in WT mice. Despite this reduction, there is no significant difference between the two genotypes in the relative sizes of the crossed and uncrossed projections (93 and 11% of total LGd volume, respectively, Fig. 3) or in the mean “segregation index”. Thus, although the absolute sizes of the LGd and the crossed and uncrossed retinal projections are significantly reduced in mice, the proportion of the nucleus in which retinal projections overlap (about 4%), is not significantly different across genotypes (SI = 1.041 ± 0.036 for WT and 1.038 ± 0.017 for mice, respectively, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Volume of the LGd, its crossed and uncrossed retinal inputs (VLGd, VC and VU, respectively) in WT and mice. The techniques used to determine all measures are described in “Methods”. The segregation index (SI; inset) is a measure of the extent of segregation of the crossed and uncrossed retino-SC projections. SI = 1 indicates perfect segregation; SI > 1 indicates overlap; SI < 1 indicates the existence of LGd regions with no retinal projection. Asterisks indicate significant differences between WT and mice for the volume measures but not for the segregation index

Neuronal numbers

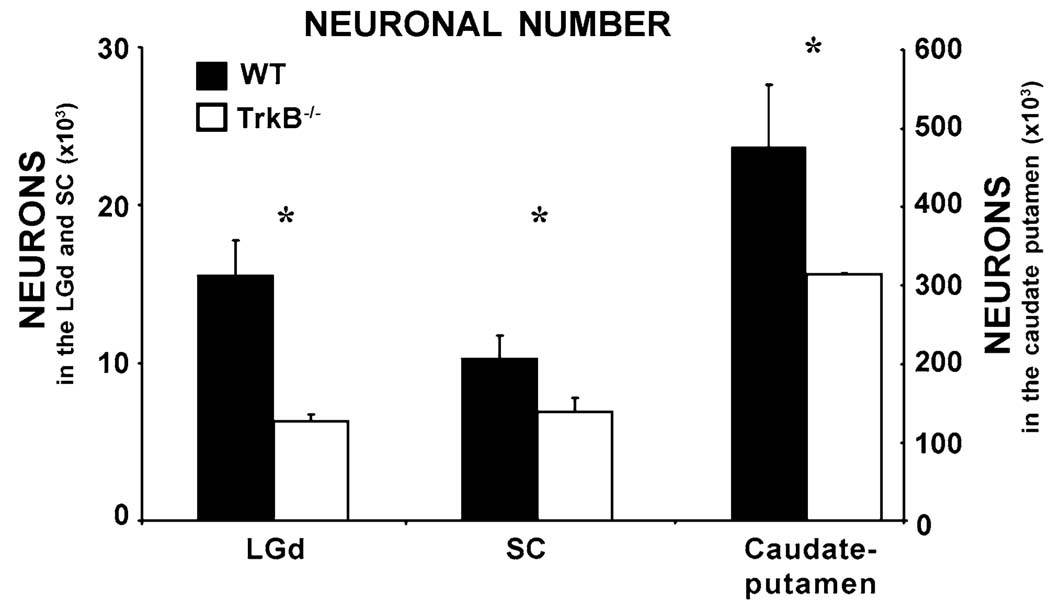

In mice, the total number of neurons (Fig. 4) is reduced to 41, 68 and 66% of WT values in LGd (P = 0.0002), SC (P = 0.003) and caudate-putamen (P = 0.005), respectively. This loss of neurons is accompanied by shrinkage of all three structures (LGd: Fig. 3; SC: Fig. 2; caudate putamen: WT: 3.64 ± 0.38 mm3; : 2.60 ± 0.35 mm3). However, there is no significant difference between WT and mice with respect to the density of neurons in the LGd (WT: 135,829 ± 11,403 cells/mm3; : 138,461 ± 12,493 cells/mm3; P = 0.76), SC (WT: 26,819 ± 4,393 cells/mm3; : 28,527 ± 4452 cells/mm3; P = 0.56) or caudate-putamen (WT: 130,427 ± 12,354 cells/mm3; : 121,096 ± 13,311 cells/mm3; P = 0.37). The cross sectional area of neuronal somata was not significantly different in mice (LGd: 106.10 ± 32.76 µm2; SC: 85.20 ± 27.70 µm2; caudate putamen: 81.65 ± 23.97 µm2) compared to WT mice (LGd: 128.64 ± 40.96 µm2; SC: 80.85 ± 19.81 µm2; caudate putamen: 87.99 ± 27.54 µm2). Because there are no significant changes in neuronal density or soma size, the shrinkage of the LGd, SC and caudate putamen in mice must be due principally to the loss of neurons in those structures.

Fig. 4.

Number of neurons in the SC, LGd and caudate putamen of TrkB−/− mice compared to WT. Asterisks indicate that in all three regions, the differences between WT and trkB−/− mice are statistically significant (P < 0.05). Error bars are standard deviations

Discussion

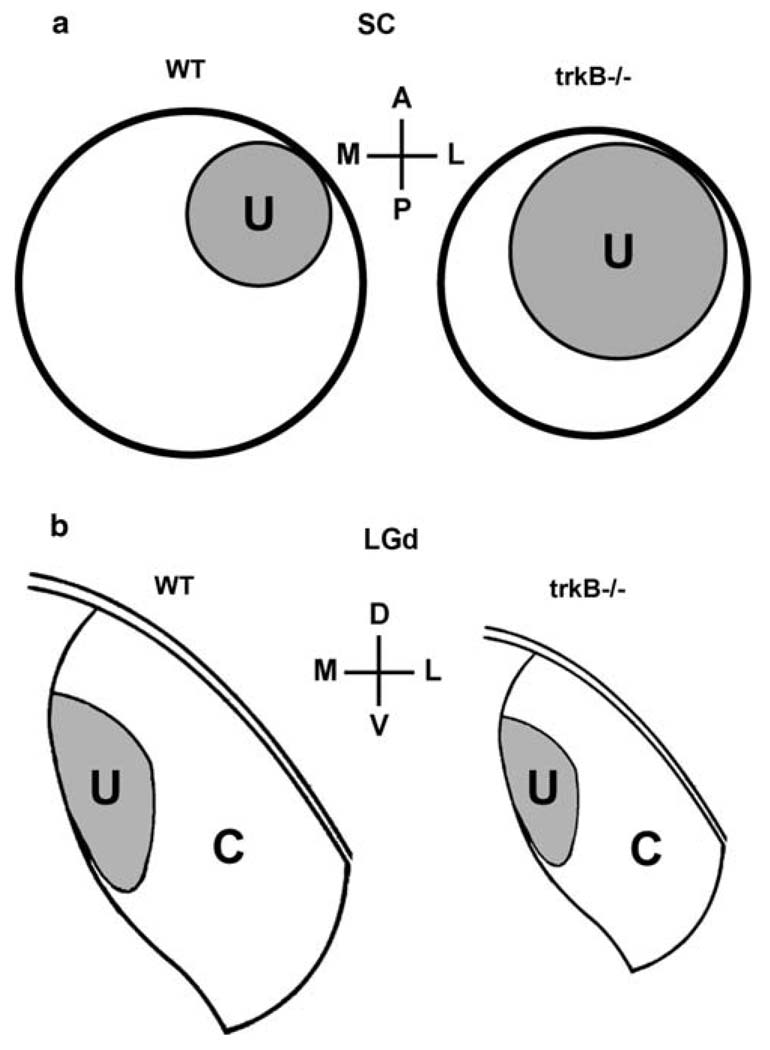

The normal, mature ocular segregation and topographic organization of retinal projections are both activity-dependent. This raises the question of whether activity exerts its effects on these two organizational features using similar cellular mechanisms. A vast literature has demonstrated the role of BDNF/trkB signaling in mediating the effects of electrical activity on the development and plasticity of neural connections (Poo 2001; Ernfors and Bramham 2003), although the specific role of activity is incompletely understood (Huberman et al. 2003). Thus, we investigated the role of trkB signaling on the topography and ocular segregation of retinal projections. Our principal findings are that in mice, (1) the number of neurons in the LGd and SC is reduced and contributes to a reduction in the size of these structures; (2) uncrossed retinal projections to the SC cluster normally; (3) the uncrossed retino-SC projection expands absolutely across the surface of the SC despite an absolute shrinkage in SC surface area (Fig. 5a); (4) segregation of uncrossed and crossed projections along lines of projection is qualitatively normal in both the SC and LGd, an observation that is confirmed by quantitative analysis in LGd (Fig. 5b). These data indicate that the normal topographic organization of uncrossed retinal projections depends upon trkB signaling, whereas eye-specific segregation of retinal projections is trkB-independent. The respective roles of the two trkB ligands, BDNF and NT4, in topographic organization are incompletely understood, although cross-phylum comparison suggests that NT-4 may have become dispensable in some vertebrate classes (Hallböök et al. 2006).

Fig. 5.

Summary of our findings of the effects of trkB null mutation on the distribution of crossed (C) and uncrossed (U) retinal projections. a Surface view of the SC. The crossed retinal input (not labeled) is distributed across the entire surface of the SC and forms a retinotopic map of the visual field (see text). In mice, there is an absolute increase in the areal spread of the uncrossed retinal input across the surface of the SC and the surface area of the SC is diminished, so that the topographic organization of the uncrossed projection is altered. Thus, the topographic organization of the uncrossed retino-SC projection depends upon trkB signaling. b Coronal sections through the LGd show that the segregation of retinal inputs from the two eyes is unaffected by trkB null mutation, although the LGd is reduced in size. Thus, the segregation of crossed and uncrossed retinal projections is trkB-independent. D dorsal, V ventral, M medial, L lateral, A anterior, P posterior

Our data show a significant loss of neurons in both the LGd and SC of mice. Although the number of neurons in the LGd, SC and caudate putamen is reduced compared to WT, the density of neurons is not significantly altered. The data from WT mice are in line with those of previous studies in juvenile or adult rats and mice when differences in brain size due to age, species and/or inbred mouse lines are taken into account LGd: (Seecharan et al. 2003; Ito et al. 2008; SC: Smith and Bedi 1997; caudateputamen:Oorschot 1996; Rosen and Williams 2001; McCarthy et al. 2007). Our data are also consistent with the reduction in neuronal number in the visual cortex of mice with forebrain-specific conditional null mutation of trkB (Xu et al. 2000) and the number of neurons in the corpus striatum of mice with a Dlx5/6 conditional null mutation of trkB (Baydyuk et al. 2008). The induced loss of neurons in the caudate-putamen demonstrates that similar alterations can occur in central neurons that express trkB both within and outside the visual system. TrkB knockout does not alter the survival of retinal ganglion cells (Rohrer et al. 2001; Pollock et al. 2003), thus illustrating that neuronal survival is not similarly affected by the mutation in all visual (or central nervous system) structures. In mice, the lack of effect on RGC number, in combination with the reduced number of LGd neurons, demonstrates that there is no numerical matching between these two neuronal populations. This conclusion is supported by comparisons across mouse lines of the numbers of RGCs and LGd neurons (Seecharan et al. 2003). Thus, during normal development, anterograde transport of endogenous BDNF and/or NT4 may not have a major role in determining the survival of immature LGd neurons. However, higher levels of exogenous BDNF transported anterogradely from the eye or exogenous NT4 transported retrogradely from the cortex can protect LGd neurons from dysfunction or degeneration due to visual cortex lesions (Caleo et al. 2003) or monocular deprivation (Riddle et al. 1995), respectively.

Our finding that null mutation does not affect ocular segregation is consistent with previous data demonstrating that null mutation of the BDNF gene does not alter the segregation of crossed and uncrossed retinal projections (Lyckman et al. 2005). Serotonin (Upton et al. 1999), nitric oxide (Vercelli et al. 2000; Wu et al. 2000), calcium influx (Cork et al. 2001) and adenylate cyclase (Ravary et al. 2003) have all been implicated in ocular segregation and may mediate the effects of electrical activity on this organizational feature of retinal projections.

The combination of absolute increases in the anterior–posterior span, posterior limit and surface area of the uncrossed retino-SC projection, despite absolute decreases in all three dimensions of the SC, assures that there is a real increase in the topographic extent of the projection, not simply a relative increase due to the shrinkage of the SC. Previous studies show that following neonatal partial retinal lesions, the projections of intact retinal regions can spread into zones normally innervated by the ablated parts of the retina; the increased spread appears to be due to reduced competition among retino-SC axons (Frost and Schneider 1979). In the present study, the trkB knockout-induced expansion of the uncrossed retinal projection may also be due to reduced competition among retino-SC axons in the plane of the retinotopic map. TrkB-dependent axonal competition occurs in the visual cortex, where trkB signaling regulates the focusing of thalamocortical projections into ocular dominance columns (Cabelli et al. 1995; Cabelli et al. 1997).

Our data demonstrate that trkB signaling is required in order to attain the normal topographic distribution of uncrossed retino-SC projections. This result is consistent with observations that focal over-expression of BDNF in the SC, prior to and during the period when the topography of uncrossed retinal projections is normally refined, results in corresponding, topographically inappropriate foci of uncrossed retinal projections (Isenmann et al. 1999). TrkB signaling could be part of a phylogenetically conserved mechanism to focus uncrossed retinal input to the representation of the binocular visual field, despite variations across species in the laterality of the eyes and, consequently, in the size of the binocular field. Although this process may be activity-dependent, it is not vision-dependent, as it is virtually complete before the photoreceptor layer becomes synaptically connected to the rest of the retina (Weidman and Kuwabara 1968; Cowan et al. 1984). As we have found for trkB signaling, NMDA receptor signaling is not required for ocular segregation (Smetters et al. 1994), although it is necessary for the normal topographic organization of retinal projections (Simon et al. 1992). By contrast, serotonin (Upton et al. 1999) contributes to both processes. Thus, different but overlapping sets of cellular mechanisms mediate the ocular segregation and topographic organization of uncrossed retinal projections.

An interesting feature of our data is that although null mutation of trkB disrupts the overall topographic distribution of uncrossed retino-SC projections, it does not disrupt their clustering in discrete regions within the overall zone of termination, even though clustering and retinotopia are both represented in the plane parallel to the surface of the SC. This may be due to the fact that crossed retinal projections extend into the SO, where uncrossed retinal projections are concentrated (Frost 1984; Godement et al. 1984). Clustering in the SO, although it occurs in the same plane as retinotopia, is likely to reflect ocular segregation, as it does in the visual cortex of carnivores and primates (Hubel and Wiesel 1962; Hubel and Wiesel 1977), where both features are also represented in the same plane. Thus, trkB signaling does not appear to contribute to ocular segregation along lines of projection or in the plane of topographic representation, even though it does regulate the topographic distribution of the uncrossed retinal projection.

It might be argued that the abnormally widespread topographic distribution of uncrossed retino-SC projections in mice is simply due to a retardation of the normal refinement process. This cannot be studied directly in mice with constitutive null mutation of trkBFL, owing to their limited life span. However, several observations argue against this possibility: (1) The rate of developmental elimination of RGCs in mice is accelerated compared to WT mice, rather than retarded (Pollock et al. 2003). Indeed, by P14 the total number of RGCs in trkB−/− mice is normal (Rohrer et al. 2001). (2) The clusters of uncrossed projections in the SC (“U” in Fig. 1b, c) are initially continuous and develop into discrete patches (Frost et al. 1979; Godement et al. 1984). Normal clustering of the uncrossed retino-SC projection in mice (Fig. 1d, e), despite a topographically expanded distribution, also argues that the topographic effects of trkB null mutation are not due to developmental retardation.

Conclusions

In mice, (1) uncrossed retinal projections to the SC cluster normally but have an enlarged topographic distribution; (2) segregation of uncrossed and crossed projections is qualitatively normal in both the SC and LGd, an observation that is confirmed by quantitative analysis in LGd. These data indicate that the normal topographic organization of uncrossed retinal projections depends upon trkB signaling, whereas eye-specific segregation of retinal projections is trkB-independent.

Acknowledgments

Grants R01-EY03465 and R21-DA13628 from the National Institutes of Health to DOF. We thank Kristina Boyd, Sherralee Lukehurst, Carole Bartlett, Anne Kramer, Ki Luo, Samantha Woo and Kai Fan Yoon for technical assistance and Bruce Krueger, Margaret Fahnestock, Lyn Beazley and Lindy Fitzgerald for critical readings of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Rodger, Experimental and Regenerative Neurosciences, School of Animal Biology M317, University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia jrodger@cyllene.uwa.edu.au.

Douglas O. Frost, Program in Neuroscience, Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 655 West Baltimore St., Baltimore, MD 21201, USA dfrost@umaryland.edu

References

- Altar CA, Siuciak J, Wright P, Ip N, Lindsay R, Wiegand S. In situ hybridization of trkB and trkC receptor mRNA in rat forebrain and association with high-affinity binding of [125I]NT-4/5 and [125I]NT-3. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:1389–1405. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydyuk M, Russell T, Liao G, An J, Reichard LF, Xu B. Society for Neuroscience. Washington, DC: CD-ROM; 2008. Role of TrkB signaling in striatal development. Abstract viewer/itinerary planner. [Google Scholar]

- Bhide PG, Frost DO. Stages of growth of hamster retinofugal axons: Implications for developing axonal pathways with multiple targets. J Neurosci. 1991;11:485–504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00485.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop PO, Kozak W, Levick WR, Vakkur GJ. The determination of the projection of the visual field on to the lateral geniculate nucleus in the cat. J Physiol (Lond) 1962;163:503–539. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp006991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunt SM, Lund RD, Land PW. Prenatal development of the optic projection in albino and hooded rats. Dev Brain Res. 1983;6:149–168. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(83)90093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabelli RJ, Hohn A, Shatz CJ. Inhibition of ocular dominance column formation by infusion of NT-4/5 or BDNF. Science. 1995;267:1662–1666. doi: 10.1126/science.7886458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabelli RJ, Shelton DL, Segal RA, Shatz CJ. Blockade of endogenous ligands of trkB inhibits formation of ocular dominance columns. Neuron. 1997;19:63–76. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80348-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caleo M, Medini P, von Bartheld CS, Maffei L. Provision of brain-derived neurotrophic factor via anterograde transport from the eye preserves the physiological responses of axotomized geniculate neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:287–296. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00287.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggeshall RE, Lekan HA. Methods for determining numbers of cells and synapses: a case for more uniform standards of review. J Comp Neurol. 1996;364:6–15. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960101)364:1<6::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cork RJ, Namkung Y, Shin HS, Mize RR. Development of the visual pathway is disrupted in mice with a targeted disruption of the calcium channel beta(3)-subunit gene. J Comp Neurol. 2001;440:177–191. doi: 10.1002/cne.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan WM, Fawcett JW, O’Leary DDM, Stanfield BB. Regressive events in neurogenesis. Science. 1984;225:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.6474175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drager UC. Autoradiography of tritiated proline and fucose transported transneuronally from the eye to the visual cortex in pigmented and albino mice. Brain Res. 1974;82:284–292. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90607-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drager UC, Hubel DH. Topography of visual and somatosensory projections to mouse superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:91–101. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernfors P, Bramham CR. The coupling of a trkB tyrosine residue to LTP. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:171–173. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00064-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DO. Axonal growth and target selection during development: retinal projections to the ventrobasal complex and other “nonvisual” structures in neonatal Syrian hamsters. J Comp Neurol. 1984;230:576–592. doi: 10.1002/cne.902300407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DO, Caviness VS., Jr Radial organization of thalamic projections to the neocortex in the mouse. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:369–393. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DO, Schneider GE. Plasticity of retinofugal projections after partial lesions of the retina in newborn Syrian hamsters. J Comp Neurol. 1979;185:517–568. doi: 10.1002/cne.901850306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DO, So K-F, Schneider GE. Postnatal development of retinal projections in Syrian hamsters: a study using autoradio-graphic and anterograde degeneration techniques. Neurosci. 1979;4:1649–1677. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(79)90026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godement P, Salaün J, Imbert M. Prenatal and postnatal development of retinogeniculate and retinocollicular projections in the mouse. J Comp Neurol. 1984;230:552–575. doi: 10.1002/cne.902300406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallbö ök F, Wilson K, Thorndyke M, Olinski RP. Formation and evolution of the chordate neurotrophin and Trk receptor genes. Brain Behav Evol. 2006;68:133–144. doi: 10.1159/000094083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindges R, McLaughlin T, Genoud N, Henkemeyer M, O’Leary DD. EphB forward signaling controls directional branch extension and arborization required for dorsal-ventral retinotopic mapping. Neuron. 2002;35:475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00799-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat’s visual cortex. J Physiol (Lond) 1962;160:106–154. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp006837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Functional architecture of macaque monkey and visual cortex. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1977;198:1–59. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1977.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN, LeVay S. Plasticity of ocular dominance columns in monkey striate cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 1977;278:377–409. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1977.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman AD, Wang GY, Liets LC, Collins OA, Chapman B, Chalupa LM. Eye-specific retinogeniculate segregation independent of normal neuronal activity. Science. 2003;300:994–998. doi: 10.1126/science.1080694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insausti R, Blakemore C, Cowan WM. Ganglion cell death during development of ipsilateral retino-collicular projection in golden hamster. Nature. 1984;308:362–365. doi: 10.1038/308362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insausti R, Blakemore C, Cowan WM. Postnatal development of the ipsilateral retinocollicular projection and the effects of unilateral enucleation in the golden hamster. J Comp Neurol. 1985;234:393–409. doi: 10.1002/cne.902340309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenmann S, Cellerino A, Gravel C, Baehr M. Excess target-derived brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) preserves the transient uncrossed retinal projection in the superior colliculus. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;14:52–65. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Shimazawa M, Inokuchi Y, Fukumitsu H, Furukawa S, Araie M, Hara H. Degenerative alterations in the visual pathway after NMDA-induced retinal damage in mice. Brain Res. 2008;1212:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhaveri S, Edwards MA, Schneider GE. Initial stages of retinofugal axon development in the hamster: evidence for two distinct modes of growth. Exp Brain Res. 1991;87:371–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00231854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Guillery RW, Allman JM. Some principles of organization in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Brain Behav Evol. 1972;6:253–299. doi: 10.1159/000123713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R, Smeyne R, Wurst W, Long LK, Auerbach BA, Joyner AL, Barbacid M. Targeted disruption of the trkB neurotrophin receptor gene results in nervous system lesions and neonatal death. Cell. 1993;75:113–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land PW, Lund RD. Development of the rat’s uncrossed retinotectal pathway and its relation to plasticity studies. Science. 1979;205:698–700. doi: 10.1126/science.462177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyckman AW, Fan G, Rios M, Jaenisch R, Sur M. Normal eye-specific patterning of retinal inputs to murine subcortical visual nuclei in the absence of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Vis Neurosci. 2005;22:27–36. doi: 10.1017/S095252380522103X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy D, Lueras P, Bhide PG. Elevated dopamine levels during gestation produce region-specific decreases in neurogenesis and subtle deficits in neuronal numbers. Brain Res. 2007;1182:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin T, Torborg CL, Feller MB, O’Leary DD. Retinotopic map refinement requires spontaneous retinal waves during a brief critical period of development. Neuron. 2003;40:1147–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00790-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlio J-P, Jaber EM, Persson H. Molecular cloning of rat trk C and distribution of cells expressing messenger RNAs for members of the trk familiy in the rat central nervous system. Neurosci. 1992;51(3):513–532. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90292-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir-Robinson G, Hwang BJ, Feller MB. Retinogeniculate axons undergo eye-specific segregation in the absence of eye-specific layers. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5259–5264. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05259.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary DDM, Fawcett JW, Cowan WM. Topographic targeting errors in the retinocollicular projection and their elimination by selective ganglion cell death. J Neurosci. 1986;6:3692–3705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-12-03692.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oorschot DE. Total number of neurons in the neostriatal, pallidal, subthalamic, and substantia nigral nuclei of the rat basal ganglia: a stereological study using the cavalieri and optical disector methods. J Comp Neurol. 1996;366:580–599. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960318)366:4<580::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock GS, Robichon R, Boyd KA, Kerkel KA, Kramer M, Lyles J, Ambalavanar R, Kaplan DR, Williams RW, Frost DO. TrkB receptor signaling regulates developmental death dynamics, but not final number, of retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10137–10145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-10137.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poo M-M. Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:24–32. doi: 10.1038/35049004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Prenatal development of the visual system in rhesus monkey. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 1977;278:245–260. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1977.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravary A, Muzerelle A, Herve D, Pascoli V, Ba-Charvet KN, Girault JA, Welker E, Gaspar P. Adenylate cyclase 1 as a key actor in the refinement of retinal projection maps. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2228–2238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02228.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese BE. The topography of expanded uncrossed retinal projections following neonatal enucleation of one eye: differing effects in dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus and superior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 1986;250:8–32. doi: 10.1002/cne.902500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle DR, Lo DC, Katz L. NT-4-mediated rescue of lateral geniculate neurons from effects of monocular deprivation. Nature. 1995;378:189–191. doi: 10.1038/378189a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer B, LaVail MM, Jones KR, Reichardt LF. Neurotrophin receptor trkB activation is not required for the postnatal survival of retinal ganglion cells in vivo. Exp Neurol. 2001;172:81–91. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen GD, Williams RW. Complex trait analysis of the mouse striatum: independent QTLs modulate volume and neuron number. BMC Neurosci. 2001;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi FM, Pizzorusso T, Porciatti V, Marubio LM, Maffei L, Changeux JP. Requirement of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor beta 2 subunit for the anatomical and functional development of the visual system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6453–6458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101120998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seecharan DJ, Kulkarni AL, Lu L, Rosen GD, Williams RW. Genetic control of interconnected neuronal populations in the mouse primary visual system. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11178–11188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11178.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatz CJ. The prenatal development of the cat’s retinogeniculate pathway. J Neurosci. 1983;3:482–499. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-03-00482.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatz CJ, Kirkwood PA. Prenatal development of functional connections in the cat’s retinogeniculate pathway. J Neurosci. 1984;4:1378–1397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-05-01378.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatz CJ, Stryker MP. Prenatal tetrodotoxin infusion blocks segregation of retinogeniculate afferents. Science. 1988;242:87–89. doi: 10.1126/science.3175636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DK, O’Leary DDM. Limited topographic specififcity in the targeting and branching of mammalian retinal axons. Dev Biol. 1990;137:125–134. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DK, Prusky GT, O’Leary DDM, Constantine-Paton M. N-methyl d-aspartate receptor antagonists disrupt the formation of a mammalian neural map. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10593–10597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetters DK, Hahm J, Sur M. An N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist does not prevent eye-specific segregation in the ferret retinogeniculate pathway. Brain Res. 1994;658:168–178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(09)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SA, Bedi KS. Unilateral eye enucleation in adult rats causes neuronal loss in the contralateral superior colliculus. J Anat. 1997;190(Pt 4):481–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1997.19040481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sretavan DW, Shatz CJ. Prenatal development of retinal ganglion cell axons: segregation into eye-specific layers within the cat’s lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci. 1986;6:234–251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-01-00234.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sretavan DW, Shatz CJ, Stryker MP. Modification of retinal ganglion cell axon morphology by prenatal infusion of tetrodotoxin. Nature. 1988;336:468–471. doi: 10.1038/336468a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson ID, Holt CE. Effects of introcular tetrodotoxin on the development of the retinocollicular pathway in the Syrian hamster. J Comp Neurol. 1989;282:371–388. doi: 10.1002/cne.902820305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton AL, Salichon N, Lebrand C, Ravary A, Blakely R, Seif I, Gaspar P. Excess of serotonin (5-HT) alters the segregation of ipsilateral and contralateral retinal projections in monoamine oxidase A knockout mice: possible role of 5-HT uptake in retinal ganglion cells during development. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7007–7024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-07007.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercelli A, Garbossa D, Biasiol S, Repici M, Jhaveri S. NOS inhibition during postnatal development leads to increased ipsilateral retinocollicular and retinogeniculate projections in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:473–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidman TA, Kuwabara T. Postnatal development of the rat retina. Arch Ophthalmol. 1968;79:470–484. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1968.03850040472015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo HH, Jen LS, So K-F. The postnatal development of retinocollicular projections in normal hamsters and in hamsters following neonatal monocular enucleation: a horseradish peroxidase tracing study. Dev Brain Res. 1985;20:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HH, Cork RJ, Mize RR. Normal development of the ipsilateral retinocollicular pathway and its disruption in double endothelial and neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene knockout mice. J Comp Neurol. 2000;426:651–665. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001030)426:4<651::aid-cne11>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Zang K, Ruff N, Zhang YA, McConnell S, Stryker M, Reichardt L. Cortical degeneration in the absence of neutrophin signaling: dendritic retraction and neuronal loss after removal of the receptor trkB. Neuron. 2000;26:233–245. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]