Abstract

Maternal depression has been consistently linked to the development of child problem behavior, particularly in early childhood, but few studies have examined whether reductions in maternal depression serve as a mediator in relation to changes associated with a family-based intervention. The current study addressed this issue with a sample of 731 families receiving services from a national food supplement and nutrition program. Families with toddlers between ages 2 and 3 were sereened and then randomized to a brief family intervention, the Family Check-Up, which included linked interventions that were tailored and adapted to the families needs. Follow-up intervention services were provided at age 3 and follow-up of child outcomes oecurred at ages 3 and 4. Latent growth models revealed intervention effects for early externalizing and internalizing problems from 2 to 4, and reductions in maternal depression from ages 2 to 3. In addition, reductions in maternal depression mediated improvements in both child externalizing and internalizing problem behavior after accounting for the potential mediating effects of improvements in positive parenting. The results are discussed with respect to targeting maternal depression in future intervention studies aimed at improving early child problem behavior.

Several types of parental psychopathology have been associated with increased risk of child psychopathology (Connell & Goodman, 2002; DelBello & Geller, 2001; Goodman & Brumley, 1990; Lapalme, Hodgins, & LaRoche, 1997). The link between maternal depression and child adjustment is perhaps the most carefully examined. This is not surprising, as women more often serve as primary caregivers compared to men, and the incidence of depression is quite high among females beginning during adolescence. Findings in the extant literature provide substantial evidence for a relation between maternal depression and negative child outcomes across developmental stages of childhood and adolescence, including both externalizing and internalizing child problem behaviors (for reviews of this literature, see Beardslee, Versage, & Gladstone, 1998; Cummings & Davies, 1994; Gelfand & Teti, 1990). These associations have been found to be particularly robust during early childhood when mothers and children spend more time together than at later ages (Marchand, Hock, & Widaman, 2002; Shaw, Vondra, Dowdell Hommerding, Keenan, & Dunn 1994, Shaw, Winslow, Owens, & Hood, 1998). Despite the consistency of associations between maternal depression and child adjustment during early childhood, most intervention programs aimed at reducing child problem behavior explicitly focus on changing parenting practices rather than maternal depression per se. More recent versions of parenting programs for young children have included components dedicated to parental well being and social support (Baydar, Reid, & Webster-Stratton, 2003; Olds, 2002); however, the vast majority continue to focus on modifying caregiving practices (Brinkmeyer & Eyberg, 2003; Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2003). A focus on parenting practices has substantial face and empirical validity, especially during early childhood when children undergo dramatic changes in cognitive and emotional development from infancy to the preschool period (Shaw & Bell, 1993) and elicit many challenges to caregivers (Fagot & Kavanaugh, 1993). Related to parenting models, several theorists have noted how maternal depression might compromise a parent's ability to be consistently and actively engaged with children and be attentive and responsive to their socioemotional needs (Belsky, 1984; Conger, Patterson, & Ge, 1995; Patterson, 1980), yet relatively few studies have directly examined whether child behavior might be improved by reducing maternal depressive symptoms (DeGarmo, Patterson, & Forgatch, 2004; Patterson, DeGarmo, & Forgatch, 2004). The present study sought to address this issue by examining whether a brief family-centered intervention designed to prevent the emergence of early conduct problems (CPs) had effects on maternal depressive symptoms, and if so, whether reductions in maternal depression mediated improvements in subsequent levels of both externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. In addition, we examined whether the mediating effects of changes in maternal depression were redundant or independent from mediating effects associated with changes in positive parenting.

Maternal Depression and Child Adjustment

The association between maternal depression and poor child outcomes is one of the most robust findings in psychological research (Gross, Shaw, & Moilanen, 2009). Both maternal clinical depression and subclinical, elevated levels of depressive symptoms have been found to be related to child maladjustment (Cummings, Keller, & Davies, 2005; Farmer, McGuffin, & Williams, 2002); as a result, the term maternal depression will be used throughout this paper to describe both criteria. Studies of children of depressed mothers across both narrowly defined developmental periods and broad age spans (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999) have yielded consistent findings linking maternal depression to disruptions in both socioemotional and instrumental functioning (Elgar, McGrath, Waschbusch, Stewart, & Curtis, 2004; Gelfand & Teti, 1990; Hay, Pawlby, Angold, Harold, & Sharp, 2003; Leve, Kim, & Pears, 2005; Sinclair & Murray, 1998). These associations have been corroborated most consistently during early childhood, when maternal depression has been linked to fussiness and difficult child temperament (Cutrona & Trouman, 1986; Whiffen & Gotlib, 1989), insecure attachment (Campbell et al., 2004; Field et al., 1988), behavior problems (Marchand et al., 2002; Shaw, Keenan, & Vondra, 1994), and reduced mental and motor development (Murray, Fiori-Cowley, Hooper, & Cooper, 1996; Sharp et al., 1995). There are also some data to suggest that elevated rates of maternal depression during the toddler years may be more predictive of later child adjustment problems than when assessed in the preschool period. For example, Shaw, Bell, and Gilliom (2000) found a direct link between maternal depressive symptoms when children were 1.5 and 2 years of age and clinically elevated reports of school-based CPs when children were age 8 (d = .73 at age 1.5), associations that were appreciably stronger than parent reports of CPs at ages 1.5 and 2. In addition, the magnitude of effects of maternal depression on age 8 CPs decreased with the child's increasing age (d = .27 when maternal depression was measured at age 5.5). As evidence links maternal depression during early childhood to subsequent child problem behavior, it follows that targeting changes in maternal depression during the toddler period might lead to reductions in later child problem behavior.

The Toddler Years as a Transition

In the past 2 decades many prevention efforts have been targeted at developmentally salient transitions to address the challenges associated with these periods for children and caregivers (Shaw, Dishion, Supplee, Gardner, & Arnds, 2006). Examples of successful preventive interventions of this type include Olds' (2002) Nurse–Family Partnership for first-time parents with newborns, Webster–Stratton's Incredible Years Program (Baydar et al., 2003) for children approaching formal school entry, and Dishion's Family Check-Up (FCU; Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003), previously applied to adolescent populations. The toddler years represent a time of marked change for children in terms of cognitive, emotional, and physical maturation. Despite growth in all of these areas, children's developing cognitive abilities are not well matched to the challenges afforded by their newfound physical mobility. Their new mobility permits children to ambulate quickly but without the cognitive appreciation to anticipate the consequences of violating other's personal space, understanding the principles of electricity or gravity, or considering the potential hazards of straying too far from caregivers in novel settings (e.g., shopping malls). Thus, toddlers require proactive involvement and monitoring to literally keep them out of harm's way (Gardner, Sonuga-Barke & Sayal, 1999). For parents dealing with this transformation (Shaw et al., 2000), the nature of the parent–child relationship changes from a focus on responsivity and sensitivity to the immobile infant's emotional and physical needs to monitoring a mobile and naive toddler. As a result, parental pleasure in childrearing has been shown to decrease from the first to second years (Fagot & Kavanagh, 1993). Previous research suggests that how caregivers respond to these changes and how involved they are during this period has been shown to have important repercussions for early CPs (Gardner et al., 1999; Shaw et al., 2000; Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003), as the course of CPs has been shown to be moderated by controlling, uninvolved, and rejecting parenting (Aguilar et al., 2000; Campbell, Pierce, Moore, Marakovitz, & Newby, 1996). As noted above, similar associations have been found between maternal depression and subsequent child CPs, and several studies have explicitly attempted to address postpartum maternal depression during infancy in the hopes of improving the quality of the parent–child relationship (see review by Barlow, Coren, & Stewart-Brown, 2003). However, few interventions initiated in early childhood have specifically examined whether reductions in maternal depressive symptoms are a potential mechanism underlying improvements in early child problem behavior. Where such changes substantially account for the intervention effect, then maternal depression would qualify as a mediating mechanism (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002; Rutter, 2005). To fill this void, the purpose of the current study was to examine the efficacy of a family-centered intervention in improving maternal depression and test whether such changes if found, accounted for reductions in both child externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors. Although the study was designed to specifically target child CPs, we also tested the same issues with children's emotional distress as measured on scales of “internalizing symptoms.” Finally, we examine the link between maternal depression and observations of positive parenting practices, and the extent these two dimensions of the caregiver environment were redundant, or uniquely accounted for longitudinal change in children's adjustment.

These questions were addressed in a sample of 731 families participating in Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) service systems in urban (Pittsburgh, PA), suburban (Eugene, OR), and rural (Charlottesville, VA) locations with a sample of children deemed as at risk for showing early-starting pathways of CPs, half of whom were randomly assigned to the intervention condition. Follow-up results on maternal depression and child CP and internalizing problems were available 1 and 2 years after initial contact.

The FCU

The FCU was developed by Dishion and Kavanagh (2003) as a preventive intervention to address the needs of youth at high-risk for problem behavior. It differs from traditional family-centered approaches by emphasizing methods to promote family's motivation to change. Based on the work of Miller and Roll-nick's (2002) Drinker's Check-Up, motivational interviewing techniques are used in conjunction with assessment data to elicit interactions between the client and therapist that promote change. After feedback of assessment data are provided in a manner that emphasizes the chasm between current level of functioning and the client's aspired level of adjustment, a flexible menu of change strategies is presented to achieve improvements in functioning. In contrast to the standard clinical model, the ecological approach is seen as a health maintenance model, which explicitly promotes periodic contact with families (at a minimum yearly) over the course of key developmental transitions. The current study focuses primarily on the FCU for families and toddlers at risk for early CPs engaged in the WIC service system.

Previous research with the FCU involved random assignment of young adolescents in public middle schools to a family resource room in contrast to a ‘middle school as usual’ control condition. The family resource rooms were staffed by trained personnel focused on engaging families in the FCU and a variety of other linked family interventions (see Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003). Using an intention to treat design, the authors found that proactive parent engagement reduced substance use among high-risk adolescents, and prevented substance use among typically developing youth (Dishion, Kavanagh, Schneiger, Nelson, & Kaufman, 2002). Significant reductions in these problem behaviors resulted from, on average, six direct contact meetings with parents over the course of 3 years. Complier average causal effect models support the notion that the FCU was the key intervention strategy, and that receipt of the FCU and linked services as needed lead to significant long-term reductions in substance use and antisocial behavior, including decreased substance use diagnoses and fewer arrests by the end of high school (Connell et al., 2008).

We have previously applied the FCU to a high-risk sample of families of toddler-age boys involved in a national program for nutrition supplements and support, referred to as the WIC Nutritional Supplement Program. Randomly assigning 120 families of toddlers to WIC as usual, versus WIC with one FCU at age 2 was found to result in reductions in subsequent problem behavior and improvement in parent involvement at ages 3 and 4, respectively (Shaw et al., 2006). In addition, intervention effects were evident for those families with a risk profile for early-starting CPs, including above-average levels of maternal depressive symptoms and child fearlessness. Those families assigned to the intervention group with this risk profile showed a sharp decline on child CPs between ages 2 and 4 compared to families in the control group with the same risk profile at age 2.

This previous study of the FCU with families of toddlers was limited by a small sample size, the use of only male children recruited from an urban community, and the extent of intervention services offered to the families. The current study, which we refer to as the Early Steps Multisite Study (ESMS), and includes no families that were involved in the earlier study on the FCU, remedies these three limitations and provides a broader perspective on possible mediating mechanisms of change. The sample size includes 731 at-risk families, half of whom were randomly assigned to the FCU versus WIC as usual. The families were recruited from three geographically and culturally unique regions, including metropolitan Pittsburgh, PA, suburban Eugene, OR, and rural Charlottesville, VA. The sample also reflects cultural diversity including African American (AA), European American (EA), and Latino families.

In addition, previous work on mediating mechanisms of the FCU has been focused on parenting practices to account for intervention effects (Dishion et al., 2008; Gardner, Shaw, Dishion, Burton, & Supplee, 2007). Although improving parenting is a primary focus of the FCU, the breadth of the initial assessment and follow-up intervention covers a broad array of factors that have been empirically linked to child problem behavior, including child behavior and parenting, but also several factors that might compromise parenting and parent–child relationship quality. These latter factors include parental economic and employment issues, neighborhood risk, parent conflict and relationship quality, and parental depression. Thus, there is reason to believe that assisting parents navigate and cope with the multiple challenges of raising children during the “terrible twos” might also be associated with improvements in maternal depression, which in turn, might promote reductions in child problem behavior. Following up on an earlier report on the ESMS that demonstrated the FCU to be associated with improvements in child CPs and positive parenting (Dishion et al., 2008), the current study includes three goals that extend the scope of the intervention's efficacy to two other collateral outcomes. Specifically, we examined whether the intervention was also successful in reducing levels of maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing problems. Further, we explored whether reductions in maternal depression-mediated improvements in child externalizing and internalizing symptoms. In addition, because the report by Dishion and colleagues (2008) also examined the mediating influence of positive parenting practices with respect to child CPs, we also examined whether mediating effects of maternal depression would remain significant after accounting for variance attributable to positive parenting in relation to both externalizing and internalizing problem behavior.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 731 mother–child dyads recruited between 2002 and 2003 from WIC programs in the metropolitan areas of Pittsburgh, PA, and Eugene, OR, and within and outside the town of Charlottesville, VA (Dishion et al., 2008). Families were approached at WIC sites and invited to participate if they had a son or daughter between 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months of age, following a screen to ensure that they met the study criteria by having socioeconomic, family, and/or child risk factors for future behavior problems. Risk criteria for recruitment were defined at or above one standard deviation above normative averages on several screening measures within the following three domains: (a) child behavior (CPs, high-conflict relationships with adults), (b) family problems (maternal depression, daily parenting challenges, substance use problems, teen parent status), and (c) sociodemographic risk (low education achievement and low family income using WIC criterion). Two or more of the three risk factors were required for inclusion in the sample.

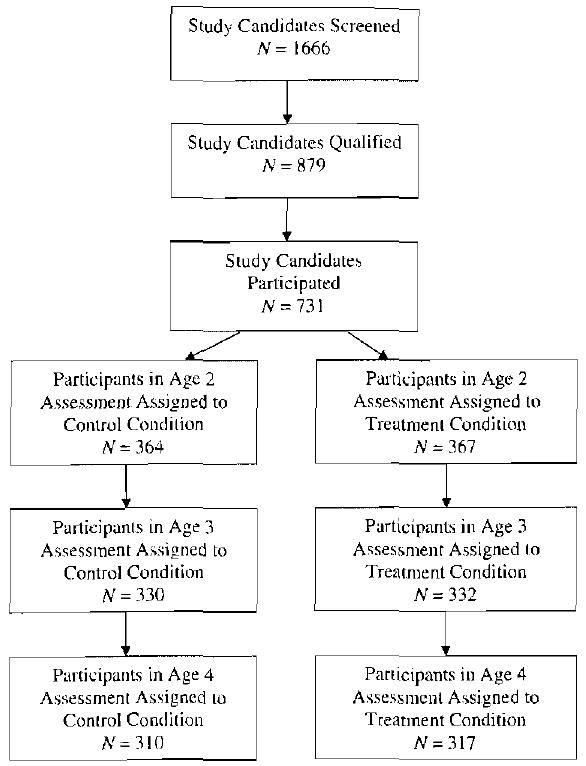

As can be seen in Figure 1 and partitioned by site in Table 1, of the 1,666 parents who were approached at WIC sites across the three study sites and had children in the appropriate age range, 879 families met the eligibility requirements (52% in Pittsburgh, 57% in Eugene, 49% in Charlottesville) and 731 (83.2%) agreed to participate (88% in Pittsburgh, 84% in Eugene, 76% in Charlottesville). The children in the sample had a mean age of 29.9 months (SD = 3.2) at the time of the age 2 assessment.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart.

Table 1. Recruitment descriptives by project site.

| Project Site | Total Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pittsburgh | Eugene | Charlottesville | ||

| Recruitment | ||||

| Screened | n = 596 | n = 565 | n = 505 | N = 1666 |

| Qualified | n = 309 | n = 323 | n = 247 | N = 879 |

| Participated | n = 272 | n = 271 | n = 188 | N = 731 |

| Participant demographics | ||||

| Race | ||||

| African American | 50.4% | 1.5% | 33.5% | 27.9% |

| European American | 38.1% | 70.0% | 39.4% | 50.1% |

| Biracial | 10.0% | 23.5% | 15.4% | 13.0% |

| Other race | 1.5% | 5.0% | 11.7% | 8.9% |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.8% | 20.0% | 20.7% | 13.4% |

| Target child age | M = 28.3 | M = 28.5 | M = 27.7 | M = 28.2 |

| (SD = 3.49) | (SD = 2.91) | (SD = 3.43) | (SD = 3.28) | |

| Target child gender | 49.6% female | 49.8% female | 48.9% female | 49.5% female |

| Annual family income | ||||

| <$20,000 | 70.5% | 62.4% | 66.0% | 66.3% |

| Family members per household | M = 4.4 | M = 4.5 | M = 4.6 | M = 4.5 |

| (SD = 1.55) | (SD = 1.67) | (SD = 1.66) | (SD = 1.63) | |

| Education | ||||

| High school diploma | 42.5% | 39.5% | 40.0% | 41.0% |

| 1–2 years post high school | 35.7% | 34.7% | 25.5% | 32.7% |

| Treatment participation | ||||

| Age 2 feedback received | 76.5% | 78.7% | 78.9% | 77.9% |

| Age 3 feedback received | 66.6% | 70.4% | 56.3% | 65.4% |

Of the 731 families (49% female), 272 (37%) were recruited in Pittsburgh, 271 (37%) in Eugene, and 188 (26%) in Charlottesville. More participants were recruited in Pittsburgh and Eugene because of the larger population of eligible families in these regions relative to Charlottesville. Across sites, the children were reported to belong to the following racial groups: 27.9% AA, 50.1% EA, 13.0% biracial, and 8.9% other races (e.g., American Indian, native Hawaiian). In terms of ethnicity, 13.4% of the sample reported being Hispanic American (HA). During the period of screening from 2002 to 2003, more than two-thirds of those families enrolled in the project had an annual income of less than $20,000, and the average number of family members per household was 4.5 (SD = 1.63). Forty-one percent of the population had a high school diploma or GED equivalency, and an additional 32% had 1 to 2 years of post high school training.

Retention

Of the 731 families who initially participated, 659 (89.9%) were available at the 1-year follow-up and 619 (84.7%) participated at the 2-year follow-up when children were between 4 and 4 years 11 months old. At ages 3 and 4, selective attrition analyses revealed no significant differences in project site, children's race, ethnicity, or gender, levels of maternal depression or children's externalizing behaviors (parent reports). Furthermore, no differences were found in the number of participants who were not retained in the control versus the intervention groups at both ages 3 (n = 40 and 32, respectively) and 4 (n = 58 and 53, respectively.

Measures

Demographics questionnaire

A demographics questionnaire was administered to the mothers during the age 2, 3, and 4 visits. This measure included questions about family structure, parental education and income, parental criminal history, and areas of familial stress.

Center for Epidemiological Studies on Depression Scale (CES-D)

The CES-D (Radloff, 1977) is a well-established and widely used 20-item measure of depressive symptomatology that was administered to mothers at the age 2 and 3 home assessments. Participants report how frequently they have experienced a list of depressive symptoms during the past week on a scale ranging from 0 (less than a day) to 3 (5–7 days). Items are summed to create an overall depressive symptoms score. For the current sample, internal consistencies were .76 and .75 at the respective age 2 and 3 assessments.

Positive parenting

Four observational measures of parenting in the home were used to create a supportive parenting composite at age 2 (for more detail, see Dishion et al., 2008). These four measures included the involvement subscale of the Infant/Toddler HOME Inventory (Caldwell & Bradley, 1978), observed duration proportions of parental positive behavior support and engagement in the parent–child interaction from the Relationship Process Code (Jabson, Dishion, Gardner, & Burton, 2004), and the proactive parenting index from the Coder Impressions Inventory. Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that these four indices form a single latent factor (Lukenheimer et al., 2007). Consequently, these scores were standardized and summed to form the positive behavior support composite used in the current study (Cronbach α = .61).

Primary outcome measure: Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

The CBCL (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) for ages 1.5 to 5 is a 99-item questionnaire that assesses behavioral problems in young children. Mothers completed the CBCL at the ages 2, 3, and 4 visits. The CBCL has two broad-band factors, internalizing and externalizing that were used to evaluate the frequency of problem behavior during the study period. Internal consistencies for externalizing were .86, .89, and .86 at ages 2, 3, and 4, respectively. For internalizing, internal consistencies were .82, .86, and .91 at ages 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Secondary outcome measure: Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory

This 36-item behavior checklist also was administered at the ages 2, 3, and 4 assessments (Robinson, Eyberg, & Ross, 1980). The Eyberg includes two factors that focus on the perceived intensity and degree the behavior is a problem for caregivers. As the intensity factor is similar in content and structure to the CBCL externalizing factor, for the current study we focused on the problem factor, which asks caregivers to report on the extent the behavior is a problem for the parent using a 7-point scale. The inventory has been demonstrated to be highly correlated with independent observations of children's behavior, to differentiate clinic-referred and nonclinic populations (Robinson et al., 1980), and show high test–retest reliability (.86) and internal consistency (.98; Webster-Stratton, 1985). In the current study, internal consistencies for the problem factor were .84, .90, and .94 at ages 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Assessment protocol

Parents (i.e., mothers and, if available, alternative caregivers such as fathers or grandmothers) who agreed to participate in the study were then scheduled for a 2.5-hr home visit. Each assessment began by introducing children to an assortment of age-appropriate toys and having them play for 15 min while the mothers completed questionnaires. After the free play (15 min), which began with the child being approached by an adult stranger (i.e., undergraduate filmer), each primary caregiver and child participated in a clean-up task (5 min), followed by a delay of gratification task (5 min), four teaching tasks (3 min each with the last task being completed by alternate caregiver and child), a second free play (4 min), a second clean-up task (4 min), the presentation of two inhibition-inducing toys (2 min each), and a meal preparation and lunch task (20 min).

The exact home visit and observation protocol was repeated at age 3 and 4 for both the control and intervention group. Families received $100 for participating in this age 2 home visit. Families were reimbursed $120 at the age 3 assessment and $140 at the age 4 assessment for their time.

Random assignment to control and intervention conditions was carried out once families were found to meet criteria for participation; however, participants were not informed of their group status until the end of the initial age 2 home assessment. Randomization sequence was computer generated by a member of staff who was not involved with recruitment. Randomization was balanced by gender to ensure an equal number of males and females in the control and intervention subsample. To ensure blindness, the examiner opened a sealed envelope, revealing the family's group assignment only after the assessment was completed, and shared this information with the family. Examiners carrying out follow-up assessments were not informed of the family's randomly assigned condition.

For purposes of the present study, only maternal reports of child problem behavior were used from the age 3 and 4 assessments, with maternal reports of depression being used from the age 3 assessment.

Intervention protocol: The FCU

Families who were informed of their random assignment to the intervention condition at the end of age 2 home assessment were then asked if they would like to participate in the FCU, initially involving an initial interview and a feedback session with parent consultants. These initial two meetings were based on the family's preferences, as were any follow-up meetings with parent consultants. Thus, for purposes of the current research study, the sequence of contacts was an assessment (baseline), randomization, an initial interview, a feedback session, and possibly follow-up sessions. Families were given a gift certificate for $25 for completing the FCU at the end of the feedback session, which could be used at local supermarkets or video stores.

Thus, the initial meeting for all participants in both control and intervention conditions was an assessment conducted with research staff, as described above, where the family engaged in a variety of in-home videotaped tasks of parent–child interaction and caregivers completed several questionnaires about their own, their child's, and their family's functioning. During this home assessment, staff also completed ratings of parent involvement and supervision. For participants in the control condition, the next contact was a similar assessment conducted with research staff at age 3. For families assigned to the intervention condition, the second session was a “get to know you” (GTKY) meeting with the parent consultant, during which time she explored parent concerns, focusing on family issues that were currently the most critical to the child's well being. The third meeting involved a feedback session, where the parent consultant summarized the results of the assessment using motivational interviewing strategies. An essential objective of the feedback session is to explore the parents' willingness to change problematic parenting practices, to support existing parenting strengths, and to identify services appropriate to the family needs. At the feedback, the parent was offered follow-up sessions that were focused on parenting practices, other family management issues (e.g., coparenting), and contextual issues (e.g., child care resources, marital adjustment, housing, vocational training).

Parent consultants who completed the FCU and follow-up parenting sessions were a combination of PhD- and Master's-level service workers, all with previous experience in carrying out family-based interventions but at the study's outset, modest experience in using the FCU. Parent consultants were initially trained for 2.5 to 3 months using a combination of strategies, including didactic instruction, and role playing, followed up by ongoing videotaped supervision of intervention activity. Despite the relatively modest number of sessions for most families, this length of time was required to ensure parent consultants were competent in interpreting data from questionnaire and observational data from the assessment, provide feedback to families about the various domains of child, parent, and extrafamilial factors relevant to the child's adjustment, and use parent training skills in working with families who desired follow-up sessions on parenting and child problem behavior. Before working with study families, parent consultants were initially certified by lead parent consultants at each site, who in turn, were certified by Dr. Dishion. Certification was established by reviewing videotapes of feedback and follow-up intervention sessions to evaluate whether parent consultants were competent in all critical components of the intervention as described below. This process is repeated yearly to reduce drift from the intervention model following the methods of Forgatch, Patterson, and DeGarmo (2005), in which it was found that direct observations of therapist fidelity to parent management training predicted change in parenting practices and child behavior. In addition, cross-site case conferences were convened on a weekly basis using videoconferencing to further enhance fidelity. Finally, annual parent consultant meetings were held to update training, discuss possible changes in the intervention model, and to address special intervention issues reflected by the needs of families across sites.

Of the families assigned to the intervention condition, 77.9% participated in the GTKY and feedback sessions at age 2 and 65.4% at age 3 (see Table 1 for site-specific data). Of the 367 families randomly assigned to the intervention group, 35.4% (n = 130) engaged in at least one follow-up intervention session above and beyond the initial GTKY and feedback sessions at age 2; 23.7% (n = 87) received follow-up intervention at age 3. Furthermore, group comparisons of participants in the intervention group who did not participate in the intervention with participants who did participate in the intervention at ages 2 and 3 (i.e., at least GTKY and feedback sessions) revealed no significant differences in terms of family income, maternal education, maternal depression, and children's behavior problems at age 2. Of those families who met with a parent consultant, the average number of sessions per family was 3.32 (SD = 2.84) at age 2 and 2.83 (SD = 2.70) at age 3, including the GTKY and feedback as two of those sessions. We also tested whether the number of sessions parents had with parent consultants was related to CBCL externalizing and internalizing or Eyberg problem factor scores at ages 3 or 4, examining correlations between number of sessions at age 2 in reference to maternal reports of problem behavior at age 3, and number of sessions at age 3 in relation to reports of problem behaviors at age 4. In previous research using the FCU with toddlers, no associations between intervention sessions and later problem behavior were found (Shaw et al., 2006). In the current analyses, initial correlations revealed a pattern of modest positive associations between number of sessions and later problem behavior. At age 3, correlations with all three child outcomes were nonsignificant trends (rs = .10, p < .10). In relation to the number of sessions at age 3, correlations with age 4 child behavior also were positive, ranging from r = .086 (ns) for CBCL externalizing, r = .093 (p < .10) for the Eyberg problem, to r = .126 (p < .05) for CBCL internalizing. However, when initial levels of child problem behavior were accounted for using partial correlations, none of the six correlations remained statistically reliable (i.e., ps > .10, except for age 4 internalizing, for which p < .10), consistent with the notion that number of sessions was related to levels of initial parent concern about child behavior. For all analyses below comparing intervention and control families on parent and child outcomes at ages 3 and 4, we use an intention to treat design, including the 22.1% of families assigned to the intervention group who did not take part in the FCU.

Analytic strategy

The central analyses in this paper examined three major issues. The first goal involved corroborating that intervention effects were evident in the growth of externalizing and internalizing symptoms, as well as perceptions of predominantly externalizing problems being a problem for mothers. These hypotheses were examined using latent growth models (LGMs), with analyses conducted in three steps. First, preliminary analyses examined unconditional LGMs to examine the extent to which a model including intercept and slope parameters, could adequately describe the pattern of change over time in the three child behavior variables, as well as to examine the significance of the variance in these parameters to examine whether significant variation existed that could potentially be predicted by the addition of covariates to subsequent models. It should be noted that with three time points, models with quadratic slope parameters could not be examined. Second, intervention status was added to each model, with the linear slope parameter regressed on intervention status. Third, each was recomputed to see whether model fit was improved by adding child gender or ethnicity.

A second goal of this paper was to examine whether random assignment to the FCU was associated with reductions in maternal depressive symptoms from ages 2 to 3. Because we only examined two waves of data in the current paper, latent growth modeling was not possible. Instead, we examined change in maternal symptoms from age 2 to 3 using an autoregressive model, with age 3 symptoms regressed on age 2 symptoms. Intervention effects were examined by regressing age 3 symptoms on intervention status. As such, this model tests whether intervention predicts age 3 maternal symptoms, controlling for baseline symptoms at age 2 (an equivalent phrasing is that this model examines intervention effects on the change in symptoms from age 2 to 3, as this model first controls for the stability of symptoms from age 2 to 3).

A third goal of this paper was to explore whether reductions in different factors of child problem behavior from ages 2 to 4 were mediated by reductions in maternal depressive symptoms from ages 2 to 3. In all models, the slope of problem behaviors was regressed on age 3 maternal depressive symptoms and intervention status, whereas maternal symptoms at age 3 were regressed on intervention status and maternal symptoms at age 2. Thus, this model tests whether intervention is related to the change in maternal symptoms from age 2 to 3, and whether this change in maternal symptoms, in turn, predicts the rate of change in child behavior problems from age 2 to 4, controlling for the direct effect of intervention. A statistical test of the significance of the indirect effect from intervention to the change in maternal symptoms to the rate of change in problem behavior was examined. Standard errors for indirect effects were calculated using the delta method described by MacKinnon and colleagues (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004).

A final set of analyses examined adding positive behavior support to the meditational models. In light of findings reported by Dishion et al. (2008), these analyses were conducted to examine whether the relations between intervention and changes in child externalizing and internalizing problems were mediated by changes in maternal depressive symptoms, positive behavior support, or both. The logic of these analyses follows the same logic described for the mediation models on maternal depressive symptoms.

All of the hypothesis-testing analyses were conducted in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2004), using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML; Muthén & Muthén, 2004), which provides a method for accommodating missing data by estimating each parameter using all available data for that specific parameter. FIML has been recommended as a state of the art technique for analyzing datasets that include missing-data (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Simulation studies indicate that FIML techniques yield relatively unbiased parameter estimates and good confidence interval coverage in samples as large as that found in ESMS (i.e., N > 500), with missing data rates even higher than the approximately 15% rate of missingness in the current sample (i.e., 25% missingness; e.g., Collins, Schafer, & Kam, 2001; Enders, 2001; Schafer & Graham, 2002). These studies have also demonstrated the clear superiority of FIML techniques versus other approaches for dealing with missing data such as listwise deletion or mean imputation (Enders, 2001).

Results

Descriptive statistics for all variables are shown in Table 2. For ease of interpretation, we present T scores on the Eyeberg and CBCL measure, although raw scores were used for models to avoid potential age and gender corrections. The percentage of the respondents in the clinical range on these measures at each age is also presented in this table. In terms of validating children's problem behavior status, for both the CBCL Externalizing and Eyberg problem factors, mean scores were approximately 2 SD above normative scores at age 2, with CBCL internalizing scores approximately 0.6 SD above the normative average. Using the borderline clinical cutoff of the 90th percentile for the CBCL, 48.6% and 38.6% of children were reported to have clinically elevated scores on the externalizing and internalizing factors at age 2. In both cases, this percentage was reduced over time to 23–24% at age 4. At age 2, 41.5% of mothers reported clinically meaningful levels of depressive symptoms using the cutoff score of 16.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

| Control | lntervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | Clinical Range N(%) | N | M | SD | Clinical Range N (%) | |

| Maternal depressive symptoms | ||||||||

| Age 2 | 363 | 16.56 | 11.02 | 148 (40.8) | 366 | 16.94 | 10.30 | 155 (42.3) |

| Age 3 | 320 | 16.26 | 10.84 | 134 (41.9) | 331 | 14.62 | 11.06 | 123 (37.2) |

| Eyeberg problem behavior (T score) | ||||||||

| Age 2 | 364 | 59.22 | 8.49 | 169 (46.4) | 365 | 59.14 | 8.45 | 154 (42.2) |

| Age 3 | 315 | 60.06 | 10.51 | 163 (51.7) | 327 | 59.18 | 10.22 | 158 (48.3) |

| Age 4 | 305 | 60.63 | 10.80 | 163 (53.4) | 311 | 58.64 | 11.15 | 139 (44.7) |

| Extemalizing behavior (T score) | ||||||||

| Age 2 | 363 | 59.32 | 7.83 | 179 (49.3) | 367 | 59.65 | 8.57 | 176 (48.0) |

| Age 3 | 320 | 56.11 | 9.56 | 117 (32.1) | 331 | 55.83 | 9.23 | 107 (29.7) |

| Age 4 | 306 | 54.67 | 9.97 | 93 (30.4) | 313 | 52.68 | 10.87 | 82 (26.2) |

| Intemalizing behavior (T score) | ||||||||

| Age 2 | 363 | 56.05 | 8.56 | 139 (38.2) | 367 | 56.60 | 8.50 | 143 (39.0) |

| Age 3 | 320 | 54.42 | 9.42 | 101 (31.6) | 331 | 54.19 | 9.79 | 102 (30.8) |

| Age 4 | 306 | 54.09 | 9.72 | 93 (30.4) | 313 | 52.43 | 10.39 | 77 (24.6) |

Correlations for all variables from age 2 to 4 are shown in Table 3. Of importance, no significant associations were found between intervention group and child gender or ethnicity, or levels of maternal depressive symptoms or any type of child problem behavior at age 2, suggesting that randomization was successful. Modest to moderate associations were consistently found between maternal depression and factors of child problem behavior concurrently and over time, and among different factors of child problem behavior.

Table 3. Correlations among study variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Treatment group | — | ||||||||||||

| 2. Child gender | −.01 | — | |||||||||||

| 3. Child ethnicity | .01 | −.05 | — | ||||||||||

| 4. Maternal CES-D, age 2 | .02 | .04 | .01 | — | |||||||||

| 5. Maternal CES-D, age 3 | −.08 | −.06 | −.01 | .42* | — | ||||||||

| 6. Eyeberg problem, age 2 | −.01 | .00 | .03 | .13* | .12* | — | |||||||

| 7. Eyeberg problem, age 3 | −.04 | .07 | −.04 | .20* | .37* | .43* | — | ||||||

| 8. Eyeberg problem, age 4 | −.09* | .05 | −.04 | .17* | .28* | .35* | .65* | — | |||||

| 9. Externalizing age 2 | .02 | .06 | −.03 | .16* | .23* | .37* | .43* | .37* | — | ||||

| 10. Extemalizing age 3 | −.02 | .08* | −.03 | .26* | .40* | .29* | .66* | .53* | .59* | — | |||

| 11. Extemalizing age 4 | −.10* | .09* | −.02 | .20* | .33* | .24* | .51* | .69* | .49* | .69* | — | ||

| 12. Internalizing age 2 | .03 | −.04 | .12* | .25* | .24* | .18* | .22* | .18* | .52* | .37* | .29* | — | |

| 13. lnternalizing age 3 | −.01 | −.06 | .08 | .29* | .40* | .14* | .39* | .34* | .34* | .59* | .47* | .63* | — |

| 14. lnternalizing age 4 | −.08* | −.02 | .06 | .21* | .33* | .10* | .30* | .47* | .29* | .44* | .65* | .50* | .67* |

p < .05.

Intervention effects on child problem behavior

Unconditional LGMs

Preliminary unconditional models examined whether LGMs including intercept and slope parameters adequately described the pattern of change in child symptoms. The unconditional model for CBCL externalizing provided reasonable fit to the data, χ2 (1) = 4.71, p = .03; comparative fit index [CFI] = .99; root mean square error analysis [RMSEA] = .07; standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = .02. The model yielded significant intercept (estimate = 20.62, SE = 0.27) and slope values (estimate = −2.41, SE = 0.16), as well as significant residual variance in the intercept (estimate = 41.59, SE = 3.82) and slope parameters (estimate = 11.40, SE = 1.80), indicating the presence of substantial variance in growth parameters that could be predicted in subsequent models.

The unconditional model for CBCL Internalizing provided excellent fit to the data, χ2 (1) = 0.66, p = .41; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00; SRMR = .01. The model yielded significant intercept (estimate = 12.45, SE = 0.24) and slope values (estimate = −0.86, SE = 0.13), as well as significant residual variance in the intercept (estimate = 35.26, SE = 3.14) and slope parameters (estimate = 7.21, SE = 1.35), indicating the presence of substantial variance in growth parameters that could be predicted in subsequent models.

The unconditional model for Eyberg problem also provided an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (1) = 0.60, p = .44; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00; SRMR = .01. The model yielded significant intercept (estimate = 14.22, SE = 0.24) and slope values (estimate = 0.12, SE = 0.17), as well as significant residual variance in the intercept (estimate = 23.82, SE = 3.31) and slope parameters (estimate = 13.11, SE = 1.91), indicating the presence of substantial variance in growth parameters that could be predicted in subsequent models.

Conditional LGMs

In a second step, intervention status was added to the LGMs. The conditional model for the CBCL Externalizing provided excellent fit to the data, χ2 (3) = 6.01, p = .11; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .02. The model yielded significant intercept (estimate = 20.63, SE = 0.27) and slope values (estimate = −2.00, SE = .22), as well as significant residual variance in the intercept (estimate = 41.57, SE = 3.82) and slope parameters (estimate = 11.24, SE = 1.79). The effect of intervention on the rate of change in problem behavior was significant (estimate = −0.82, SE = 0.29; β = −.12). The results indicated that although both children in the control and intervention groups showed reductions in externalizing scores over time, children in the intervention group showed a significantly sharper decrease than controls from ages 2 to 4 (d = .23).

The conditional model for CBCL Internalizing also provided an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (3) = 1.42, p = .70; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00; SRMR = .01. The model yielded significant intercept (estimate = 12.45, SE = 0.24) and slope values (estimate = −0.57, SE = 0.18), as well as significant residual variance in the intercept (estimate = 35.28, SE = 2.14) and slope parameters (estimate = 7.10, SE = 1.35). The effect of intervention on the rate of change in problem behavior was significant (estimate = −0.58, SE = 0.24; β = −.11). Similar to the pattern found for externalizing, although both groups of children showed declines in problem behavior over time, children in the intervention group were reported to demonstrate a significantly higher rate of decline than control children from ages 2 to 4 (d = .21).

The conditional model for the Eyberg problem also provided an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (3) = 0.52, p = .91; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00; SRMR = .001. The model yielded significant intercept (estimate = 14.22, SE = 0.24) and slope values (estimate = 0.49, SE = 0.24), as well as significant residual variance in the intercept (estimate = 23.70, SE = 3.33) and slope parameters (estimate = 12.75, SE = 1.93). The effect of intervention on the rate of change in problem behavior was significant (estimate = −0.71, SE = 0.32; β = −.10). The results mirrored those found for the two CBCL factors, with perceptions of problem behavior remaining stable for those in the intervention group, but problem behavior increasing for mothers in the control group (d = .23).

In a third step, all models were recomputed including child gender (0 = female, 1 = male) and ethnicity (0 = Caucasian, 1 = ethnic minority) as control variables. The intervention effect remained significant in all analyses, and excellent model fit was retained in all cases.

Intervention effects on maternal depression

Our second goal was to test whether the intervention was associated with a reduction in levels of maternal depressive symptoms for mothers in the intervention group relative to controls between ages 2 and 3, controlling for age 2 depressive symptoms. A two-wave autoregressive model was run to examine the effect of intervention on age 3 maternal depressive symptoms, controlling for age 2 symptoms. This model provided excellent fit to the data, χ2 (1) = 0.23, p = .63; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00; SRMR = .01. Age 3 maternal depressive symptoms were significantly predicted by intervention (estimate = −1.95, SE = 0.78; β = −.09), and by age 2 maternal symptoms (estimate = 0.44, SE = 0.04; β = .42). Mothers in the intervention group reported a significantly greater decrease in depressive symptoms than control mothers (d = .18). Results were unchanged adding child gender and ethnicity as covariates.

Mediation effects of maternal depression

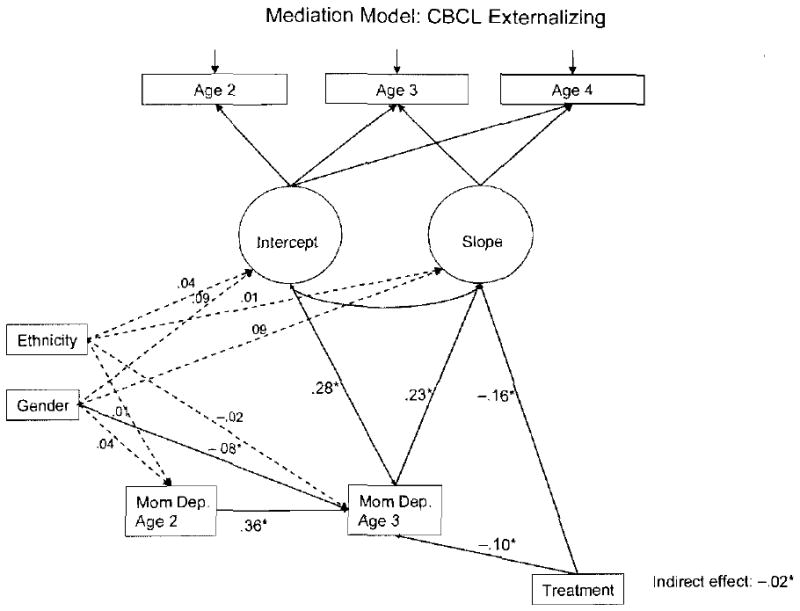

Mediator analyses examined the indirect effect of intervention on the rate of change in problem behaviors through the effect of intervention on maternal symptoms at age 3. For ease of interpretation, these results are shown in Figures 2, 3, and 4. As shown in Figure 2, the model for CBCL externalizing provided reasonable fit to the data by most indices of model fit, χ2 (10) = 39.48, p < .05; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .04, and the nonsignificant χ2 may be related to the large sample size. In this model, the direct effect of intervention on the problem behavior slope was not significant with maternal symptoms included in the model. Intervention significantly predicted reductions in maternal symptoms from age 2 to 3. Higher maternal depressive symptoms predicted greater growth in problem behavior (conversely, lower symptoms were related to less growth in problem behavior). The indirect effect from intervention to reduced maternal symptoms to lower growth in problem behavior was statistically significant, although small in magnitude.

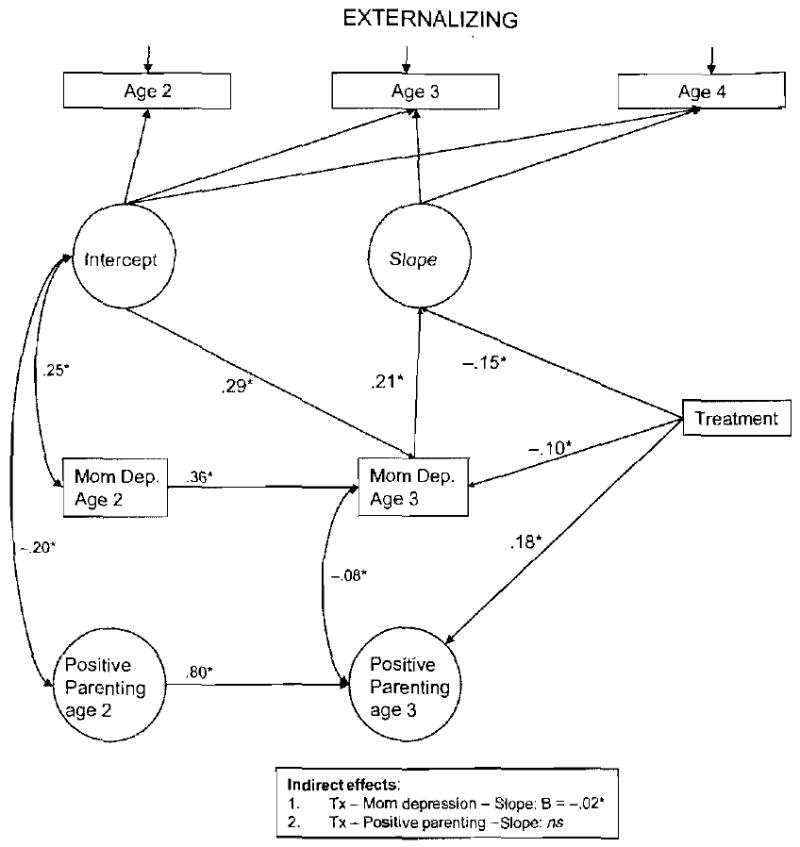

Figure 2.

Mediation model for externalizing.

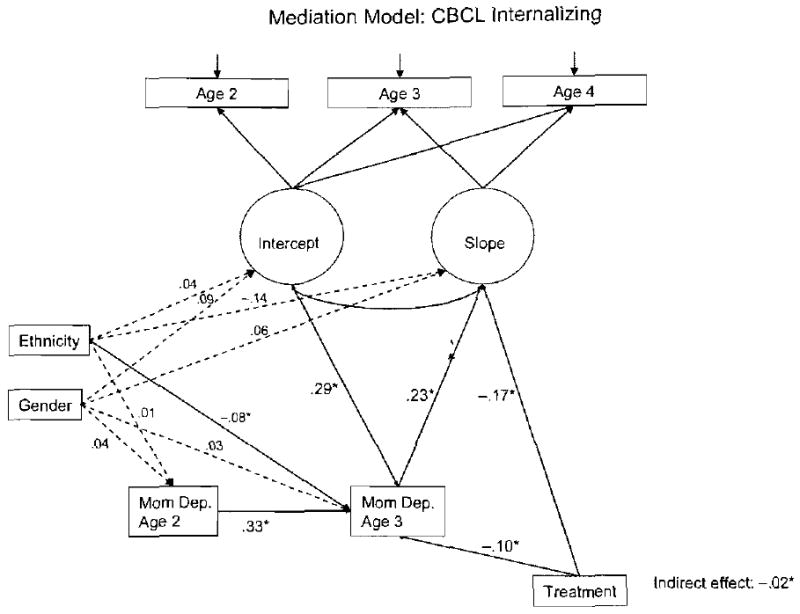

Figure 3.

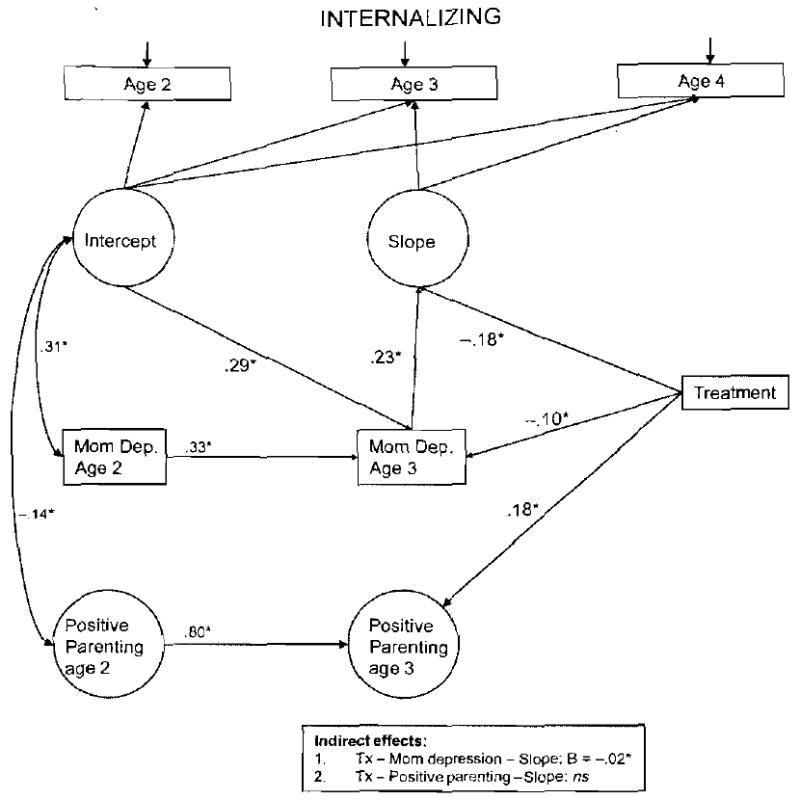

Mediation model for internalizing.

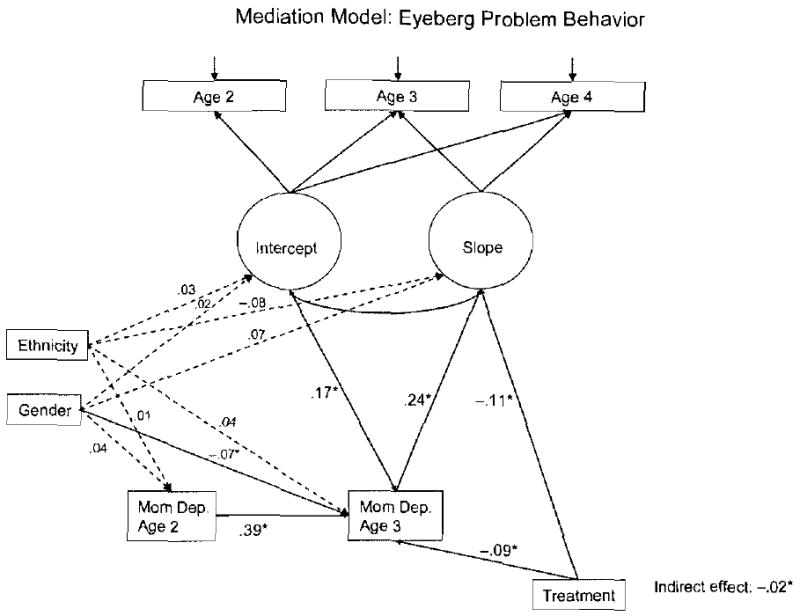

Figure 4.

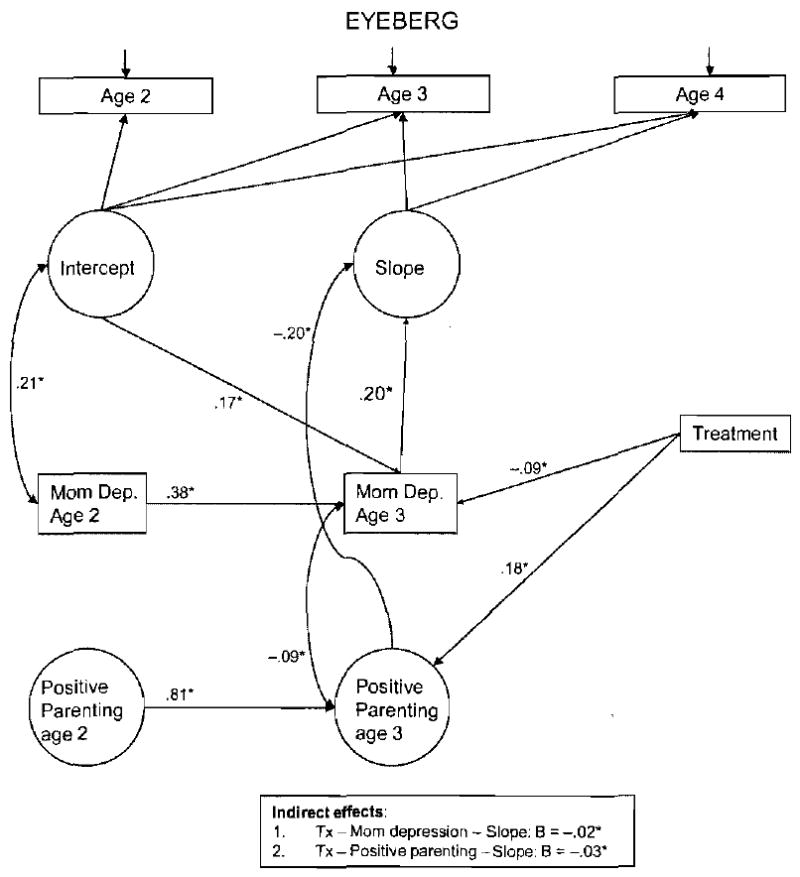

Mediation model for Eyeberg problem behavior.

Similar results were obtained for the CBCL Internalizing (see Fig. 3). The model for Internalizing provided reasonable fit to the data by most indices of model fit, χ2 (10) = 39.13, p < .05; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .03. In this model, the direct effect of intervention on the internalizing slope was not significant with maternal symptoms included in the model. Intervention significantly predicted reductions in maternal symptoms from age 2 to 3. Higher maternal depressive symptoms predicted greater growth in internalizing problems (and lower symptoms were related to less growth in internalizing problems). The indirect effect from intervention to reduced maternal symptoms to lower growth in internalizing problems was statistically significant, although small in magnitude.

The model for the Eyberg problem scale (see Fig. 4) provided reasonable fit to the data by most indices of model fit, χ2 (10) = 43.26, p < .05; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .07; SRMR = .03. The nonsignificant chi square may be related to the large sample size, because chi square is sensitive to sample size. In this model, the direct effect of intervention on the problem behavior slope was not significant with maternal symptoms included in the model. Intervention did significantly predict greater reductions in maternal symptoms from age 2 to 3. Higher maternal depressive symptoms predicted greater growth in problem behavior (conversely, lower symptoms were related to less growth in problem behavior). The indirect effect from intervention to reduced maternal symptoms to lower growth in problem behavior was statistically significant, although small in magnitude.

Mediation effects of maternal depression and positive parenting

A final set of mediator analyses examined the indirect effect of intervention on the rate of change in problem behaviors through the effects of intervention on both maternal symptoms at age 3, and positive behavior support at age 3. For ease of interpretation, these results are shown in Figures 5, 6, and 7. For clarity of presentation, only significant effects are shown in these models.

Figure 5.

Maternal depression and positive parenting for Eyberg problem behavior score.

Figure 6.

Maternal depression and positive parenting for CBCL externalizing problems score.

Figure 7.

Maternal depression and positive parenting for CBCL internalizing problems score.

The model for the Eyberg Problem Behavior Scale provided good fit to the data by most indices of model fit, although the nonsignificant chi square is likely due to the large sample size, χ2 (82) = 151.75, p < .05; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .03; SRMR = .04. As shown in Figure 5, results of this model indicated that both maternal depressive symptoms and positive behavior support independently mediated the link between the receipt of intervention and the rate of change in CPs from ages 2 to 4, although both mediated pathways were small in magnitude.

The model for CBCL externalizing provided reasonable fit to the data by most indices of model fit, χ2 (82) = 132.78, p < .05; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .03; SRMR = .04, as did the model for CBCL Internalizing provided reasonable fit to the data by most indices of model fit, χ2 (82) = 133.15, p < .05; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .03; SRMR = .04, although the nonsignificant chi square is likely due to the large sample size. As shown in Figures 6 and 7, however, results of models for both CBCL scales indicated that only maternal depressive symptoms mediated the relation between intervention and the rate of change in conduct or internalizing problems from age 2 to age 4. Controlling for the effect of maternal depressive symptoms, the positive behavior support no longer served as a significant mediator of intervention effects in these analyses.

Discussion

Three major issues were addressed here. The first goal involved building on and extending the initial findings from Dishion and colleagues (2008) by showing that in addition to the FCU being associated with reductions in child externalizing problems, it was also related to reductions in child internalizing symptoms. A second goal was to examine whether random assignment to the FCU was associated with reductions in maternal depressive symptoms from ages 2 to 3. In line with predictions, mothers who received intervention reported reductions in depression across ages 2 to 3, relative to mothers in the control group. A third goal was to examine whether reductions in child behavior and emotional problems from ages 2 to 4 were mediated by reductions in maternal depressive symptoms from ages 2 to 3. In fact, for all three child problem behaviors, including externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as perceptions of externalizing symptoms being a problem, direct effects between intervention status and child problem behavior from ages 2 to 4 were mediated by changes in maternal depression from ages 2 to 3. Finally, maternal depression continued to be a significant mediator of intervention effects for all three factors of child problem behavior when positive parenting was included as a dual mediator of intervention effects, with positive behavior support continuing to serve as a significant mediator in the case of the Eyberg Problem Behavior Scale.

The current findings corroborate and expand upon results from the broader literature on the effectiveness of preventive interventions aimed at reducing child CPs in early childhood (Baydar et al., 2003, Olds, 2002), demonstrating that the intervention is also effective in reducing maternal perceptions of internalizing symptoms. The findings also provide additional support for the effectiveness of the FCU in general (Connell et al., 2008; Connell, Dishion, & Deater-Deckard, 2006) and its application to high-risk families during the toddler period. Previously, we had found that that one dose of the FCU was successful in reducing subsequent child CPs and improving positive parenting and parental involvement with a smaller sample of toddler-age boys from an urban community (Gardner et al., 2007; Shaw et al., 2006). However, no between-group differences were found with respect to maternal depressive symptoms in the earlier study, suggesting that repeated contact with families at age 3 might have facilitated this new change. In addition, the previous application of the FCU found no intervention effects for child internalizing symptoms, also suggesting the potential benefit of repeated, albeit relatively brief, contact with families.

Accounting for change in maternal depression

One of the most interesting findings of the study was that the FCU was associated with improvements in maternal depressive symptoms even though for most families maternal depression was not listed as a primary goal by parents or a topic that was explicitly addressed by parent consultants. An analysis of the first 235 of 360 intervention families revealed that the broad category of “parent self-care” was the sixth most endorsed goal (24.3%), falling behind others such as child problem behavior (50.2%), discipline strategies (31.9), and family self-sufficiency (30.2%; Schlatter et al., 2005). In addition to including maternal depression, parent self-care also included issues such as “finding time for me to relax” and “doing more things as my own”; thus, it is likely that those interested in working on improving depressive symptoms was considerably less than 24% of mothers. Despite the fact that relatively few mothers' depressive symptoms were treated directly, there are a couple possible explanations to account for how reductions in symptoms of maternal depression occurred. One explanation might be that changes in depression should be attributable to changes parents made in caregiving practices, specifically positive parenting. In fact, DeGarmo and colleagues (2004) found results consistent with the notion that improvements in parenting skills preceded improvements in child antisocial behavior, which in turn, preceded later reductions in maternal depressive symptoms. Using the current sample, we found that improvements in child CPs from 2 to 4 were accounted for by improvements in positive parenting in the intervention group (Dishion et al., 2008). However, follow-up analyses revealed that positive behavior support and maternal depression were only modestly correlated at ages 2 and 3, although intervention predicted changes in each domain from age 2 to 3. Further, as demonstrated in our final analyses when both positive behavior support and maternal depression were included as potential mediators of intervention effects, it appears that the mediating effects of maternal depression were more consistent across problem behavior scales. However, these results need to be interpreted with caution because both maternal depression and child problem behavior scales were reported on by mothers and the measure of positive behavior support was based on observational data, likely attenuating the magnitude of the effect of positive behavior support and overestimating the contribution of maternal depression.

Another possibility is that changes in maternal depression were related to more generic aspects of the establishment of the parent–parent consultant relationship, including such factors as trust, having a confidant to talk to (even if this contact does not occur often), and access to an expert to discuss the challenges of raising a toddler. Cumulatively these may have resulted in improving maternal depressed mood. In addition, parent consultants were available to provide assistance to mothers who suffered short-term crises (e.g., a fire burning down their residence, lack of food, no money to pay for electricity), or long-term challenges in living (e.g., recent immigrants' familiarity with English and American culture, moving out of project neighborhoods, isolation for rural families, spousal abuse). As families were screened on the basis of multiple socioeconomic, family, and child risk during a development period known to be challenging even for parents with greater economic and family resources, it seems probable that having repeated contact with someone in the community to help navigate these challenges may have lessened initial levels of depression, which at baseline averaged above the clinical cutoff on the CES-D for both control and intervention families. We believe that cumulatively, despite the relatively few number of in vivo contacts parents had with parent consultants that the intervention likely increased mother's sense of control about their lives. As intervention was specifically tailored to the most pressing concerns expressed by mothers, including parenting and relationship skills, life stressors, and in a minority cases, depressed mood, perhaps it should not be surprising that improvements in maternal depressive symptoms occurred.

That change in maternal depression, although modest in magnitude, mediated changes in multiple types of child problem behavior was less surprising. Although few intervention studies have documented that modifying maternal depressive symptoms accounts for intervention effects on child problem behavior (Patterson et al., 2004), there is large body of evidence demonstrating associations between maternal depression and multiple forms of child problem behavior (Cummings et al., 2005; Farmer et al., 2002; Gelfand & Teti, 2002; Leve et al., 2005). The current results suggest that developers of early intervention programs may want to explicitly focus on maternal depression as a target of change, particularly procedures with a proven track record of success in reducing depressive symptomatology (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy).

Although we provide evidence to suggest that the FCU is associated with improvements in child problem behavior and maternal depressive symptoms, effect sizes were relatively modest (ds = .18–.23). The magnitude of effect sizes should not be surprising given the relatively modest intensity of the intervention (M = 3.3 to 2.8 sessions from ages 2 to 4, respectively). However, one could still reasonably wonder whether the intervention effects found for maternal depression and child problem behavior are clinically meaningful. Only continued follow-up of the current sample will shed light on this question, but there is good reason to believe that modifying several risk factors associated with later antisocial behavior, even modestly, will result in a fewer percentage of children following an early-starting course (Aguilar et al., 2000; Moffitt Caspi, Dickson, Silva, & Stanton, 1996). A recent follow-up of low-income boys followed from infancy to age 15 found that such factors as parenting and maternal depression assessed at age 2 and child externalizing problem behavior and co-occurring externalizing and internalizing problems assessed at age 3 were associated with early-starting trajectories of antisocial behavior from age 2 to 15 (Shaw & Gross, 2008). By modifying several of these risk factors in early childhood, all of which have been done in the current application of the FCU (Dishion et al., 2008), it increases the probability clinically meaningful reductions in early-starting pathways will be reduced. Again, only continued follow-up of the current sample will validate or invalidate this hypothesis.

Limitations

The study has one significant limitation that deserves consideration: the issue of potential reporter bias. There is consistent evidence in the literature that mothers with elevated levels of depressive symptoms show a tendency to report higher levels of children's problem behavior (Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1993). As mothers reported on both depressive symptoms and children's externalizing and internalizing problem behavior, reductions in maternal depressive symptoms that appeared to be a function of randomization to the intervention group may have also amplified group differences in problem behavior and maternal perceptions of the severity of externalizing symptoms (i.e., Eyberg problem factor). On the one hand, it is possible that group differences are partially responsible for perceived changes in child problem behavior. However, Dishion and colleagues (2008) recently found that observed parenting behaviors predicted improvements in mother-rated behavior problems in this sample, supporting the notion that mother reported problems relate to independently observed parenting behavior in the predicted manner in this study. It should also be noted that as elevated levels of depressive symptoms during the toddler period have been related to teacher reports of low-income children's CPs, it is still possible that modifying maternal depression during the toddler period will be associated with reduced problem behavior during the school-age period. Future planned assessments that include teacher and aftercare provider reports will shed light on whether improvements in problem behavior are limited to maternal perceptions and the home environment, as well as time.

Implications and Future Directions

The current findings corroborate previous evidence that longitudinal changes in child disruptive behavior can be achieved with a brief family-based intervention for toddlers, and that such change appeared to be mediated by improving positive parenting practices. This was achieved using an existing, nationally available, service delivery setting with low-income children who are at risk for early-starting pathways of externalizing problem behavior and whose families do not typically use mental health services (Haines, McMunn, Nazroo, & Kelly, 2002). Future follow-up of the present cohort should clarify issues regarding the intervention's endurance and generalizability to other contexts.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar B, Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson E. Distinguishing the life-course-persistent and adolescent-limited antisocial behavior types: From birth to 16 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:109–132. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N, Reid MJ, Webster-Stratton C. The role of mental health factors and program engagement in the effectiveness of a preventive parenting program for Head Start mothers. Child Development. 2003;74:1433–1453. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Coren E, Stewart-Brown SSB. Parent-training programmes for improving maternal psychosocial health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;4:CD002020. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TG. Children of affectively ill parents: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1134–1141. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmeyer MY, Eyberg SM. Parent–child interaction therapy for oppositional children. In: Kazdin A, Weisz J, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 204–223. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. Manual for the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. Little Rock, AR: University of Arkansas; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Brownell CA, Hungerford A, Spieker S, Mohan R, Blessing JS. The course of maternal depressive symptoms and maternal sensitivity as predictors of attachment security at 36 months. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:231–252. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Pierce EW, Moore G, Marakovitz S, Newby K. Boys' externalizing problems at elementary school: Pathways from early behavior problems, maternal control, and family stress. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:701–720. [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Schafer J, Kam CM. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:330–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Patterson GR, Ge X. It takes two to replicate: A mediational model for the impact of parents' stress on adolescent adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Dishion T, Deater-Deckard K. Variable- and person-centered approaches to the analysis of early adolescent substance use: Linking peer, family, and intervention effects with developmental trajectories. Merrill–Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52:421–448. [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Bullock BM, Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Wilson M, Gardner F. Family intervention effects on co-occurring behavior and emotional problems in early childhood: A latent transition analysis approach. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1211–1225. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9244-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Goodman S. The association between child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems and psychopathology in mothers versus fathers: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:746–773. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:73–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Keller PS, Davies PT. Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: Exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:479–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Trouman BR. Social support, infant temperament, and parenting self-efficacy: A mediational model of postpartum depression. Child Development. 1986;57:1507–1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. Why do parent training intervention outcomes maintain or wane over time? Prevention Science. 2004;5:73–89. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000023078.30191.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, Geller B. Review of studies of child and adolescent offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disorders. 2001;3:325–334. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.30607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K, Schneiger A, Nelson SE, Kaufman N. Preventing early adolescent substance use: A family-centered strategy for the public middle-school ecology. Prevention Science. 2002;3:191–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1019994500301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell A, Wilson M, Gardner F, Weaver C. The Family Check Up with high-risk families with toddlers: Outcomes on positive parenting and early problem behavior. Child Development. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgar FJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH, Curtis LJ. Mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:441–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:352–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot B, Kavanaugh K. Parenting during the second year: Effects of children's age, sex, and attachment classification. Child Development. 1993;64:258–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer A, McGuffin P, Williams J. Measuring psychopathology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. The effect of maternal depression on maternal ratings of child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:245–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00917534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Healy B, Goldstein S, Perry S, Bendell D, Shanberg S, et al. Infants of depressed mothers show “depressed” behaviour even with non-depressed adults. Child Development. 1988;59:1569–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS. Evaluating fidelity: Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon Model of Parent Management Training. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Shaw D, Dishion T, Burton J, Supplee L. Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to preventing conduct problems: Linking changes in proactive parenting to boys' disruptive behavior in early childhood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:398–406. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Sonuga-Barke E, Sayal K. Parents anticipating misbehavior: An observational study of strategies parents use to prevent conflict with behavior problem children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:1185–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand DM, Teti DM. The effects of maternal depression on children. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10:320–354. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Brumley HE. Schizophrenic and depressed mothers: Relational deficits in parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SJ, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross HE, Shaw DS, Moilanen K. Reciprocal associations between boys' externalizing problems and mothers' depressive symptoms. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9224-x. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines MM, McMunn A, Nazroo JY, Kelly YJ. Social and demographic predictors of parental consultation for child psychological difficulties. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 2002;24:276–284. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/24.4.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF, Pawlby S, Angold A, Harold GT, Sharp D. Pathways to violence in the children of mothers who were depressed postpartum. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:1083–1094. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabson JM, Dishion TJ, Gardner FEM, Burton J. Relationship Process Code V-2.0 training manual: A system for coding relationship interactions. University of Oregon, Child and Family Center; 2004. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Lapalme M, Hodgins S, LaRoche C. Children of parents with bipolar disorder: A metaanalysis of risk for mental disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;42:623–631. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Kim HK, Pears KC. Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:505–520. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6734-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Skuban EM, Dishion TJ, Connell AM, Shaw DS, Gardner F, et al. Collateral benefits of the Family Check-lip on early childhood school readiness: Indirect effects of parents' positive behavior support. University of Oregon; 2007. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Wilson T, Fairburn C, Agras W. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand JF, Hock E, Widaman K. Mutual relations between mothers' depressive symptoms and hostile-controlling behavior and young children's externalizing and internalizing behavior problems. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:335–353. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Silva P, Stanton W. Childhood-onset versus adolescent-onset antisocial conduct problems in males: Natural history from ages 3 to 18 years. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:399–424. [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Fiori-Cowley A, Hooper R, Cooper PJ. The impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother infant interactions and later infant outcome. Child Development. 1996;67:2512–2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user's guide. 3rd. Los Angeles: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Olds D. Prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses: From randomized trials to community replication. Prevention Science. 2002;3:153–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1019990432161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Mothers: The unacknowledged victims. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1980;45(5 Serial No 186) [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS, Forgatch MS. Systematic changes in families following prevention trials. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:621–633. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047211.11826.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EA, Eyberg SM, Ross AW. The standardization of an inventory of child conduct problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1980;9:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Environmentally mediated risks for psychopathology: Research strategies and findings. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145374.45992.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Graham J. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]