Abstract

This study tests whether pro-alcohol peer influences and prosocial involvement account for increases in drinking during the transition into emerging adulthood and whether these mechanisms differ depending on college attendance and/or moving away from home. We use structural equation modeling of prospective data from 825 young men and women. For four groups defined by college and residential status, more drinking in the spring of 12th grade predicts more pro-alcohol peer influences the following fall, and more pro-alcohol peer influences in the fall predict increases in drinking the following spring. Going to college while living at home is a protective factor for increases in drinking and selection of pro-alcohol peer involvements. Prosocial involvement (measured by involvement in religious activities and volunteer work) is not significantly related to post-high school drinking except among college students living away from home. Prevention efforts should focus on reducing opportunities for heavy drinking for college and noncollege emerging adults as they leave home and increasing prosocial involvement among college students not living at home.

Keywords: Drinking, alcohol, emerging adulthood, college students, non-college youth, transition to adulthood, peer influence

Arnett (2000) coined the term “emerging adulthood” to define a new stage in the life cycle between adolescence and young adulthood that is distinct from both. This stage, which occurs predominantly in industrialized countries, begins following high school (at approximately age 18) and ends with the adoption of adult roles, including marriage, parenthood, and career (at approximately age 25, although it lasts longer for many youth) (Arnett, 2000). Many researchers (e.g., Cohen, Kasen, Chen, Hartmark, & Gordon, 2003; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002; Schulenberg, Sameroff, & Cicchetti, 2004; Shanahan, 2000) have identified this stage as a key developmental time period characterized by rapid transitions in social context and marked individual variation in development. Changing social contexts in emerging adulthood afford greater freedom and less social control than experienced during adolescence, and increased opportunity for involvement in risk behaviors such as substance use, risky driving, and unprotected sex (Arnett, 2000). The present study focuses on continuity and discontinuity in alcohol use during the transition to emerging adulthood. Specifically, this study tests whether pro-alcohol peer influences and prosocial involvement (as measured by religious participation and volunteer work) account for increases in drinking during the transition into emerging adulthood and whether these mechanisms differ depending on college attendance and/or moving away from home.

A number of factors have been identified that may contribute to increases in alcohol use during emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2005; Schulenberg et al., 2005). Yet, there is a need to more concretely identify the circumstances that bring about change in drinking and the mechanisms involved in the process (Rutter, 1996). Residential status and school status changes have been identified as two critical circumstances that bring about change during emerging adulthood. Several researchers have attributed increases in heavy drinking during emerging adulthood to the college experience (e.g., Barry & Nelson, 2005; Dowdall & Wechsler, 2002; Presley, Meilman, & Leichliter, 2002), but the data have been equivocal as to whether there are real differences between college students and nonstudents in various patterns of drinking (for a review, see Slutske et al., 2004). Furthermore, studies find that increases in heavy drinking occur for both college students and their noncollege peers after high school (Bachman, Wadsworth, O'Malley, Johnston, & Schulenberg, 1997; White, Labouvie, & Papadaratsakis, 2005).

Others have argued that it is living situation (i.e., away from parents) that accounts for the college effect (Baer, 1994; White et al., 2006). Studies consistently find that college students living with their parents drink less than those who live on or off campus (Harford, Wechsler, & Muthén, 2002; White et al., 2006). White and colleagues (2006) found that leaving home, compared to going to college, was a stronger predictor of increases in the frequency of drinking and heavy episodic drinking from the end of high school to the following fall (see also Bachman et al., 1997; Crowley, 1991; Gfroerer, Greenblatt, & Wright, 1997). When studies have controlled for background characteristics and living situation, the effects of college often disappear (Slutske et al., 2004).

Because changes in drinking from adolescence to emerging adulthood vary depending on whether youths go to college or move away from home, the processes that affect transitions in drinking may also differ depending on social circumstances as defined by college and residential status. Few studies, however, have identified the mechanisms that account for these transitions under varying social circumstances (Dowdall & Wechsler, 2002). In this study, we focus on two mechanisms (pro-alcohol peer influences and prosocial involvement) that may account for increased alcohol use in emerging adulthood for both college students and their noncollege peers. We base our selection of these mechanisms on the Social Development Model (SDM, Catalano & Hawkins, 1996, 2002).

The Social Development Model (SDM)

The SDM is an integrated theory that explains the development of prosocial and antisocial behavior over the life course (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996, 2002). The theory hypothesizes that socialization follows the same processes of social learning whether it produces positive or problem behaviors. The SDM hypothesizes that an individual's behavior will be shaped by the amount of association with prosocial and antisocial individuals and the amount of involvement in prosocial and antisocial activities. Two mechanisms that can produce changes in alcohol use suggested by the SDM are the amount of involvement with and reinforcement from pro-alcohol peers, an influence for increased alcohol use, and the amount of prosocial involvement (e.g., religious participation and volunteer work), an influence for decreased alcohol use. The SDM emphasizes lasting effects of earlier socialization, with bonds and behaviors formed during the prior developmental period having lasting influences, even as social environments change (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996).

Pro-alcohol Peer Influences and Prosocial Involvement

Pro-alcohol peer influences

Changes in peer group context are important social processes that occur during the transition out of high school and into emerging adulthood (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). Studies of college students have consistently found that peer use is among the strongest, if not the strongest, predictor of alcohol use (Baer, 2002; Borsari & Carey, 2001; Jackson, Sher, & Park, 2006; Perkins, 2002). The college environment provides strong social influences for heavy drinking, which include modeling/socialization (peer use), alcohol-related opportunities, and reinforcement (encouragement or pressure to use) (Read, Wood, & Capone, 2005).

Several studies have demonstrated that peer influences on substance use result from both selection and socialization effects (see Kandel, 1996; Pandina, Johnson, & White, in press). For example, Leibsohn (1994) found that entering freshman sought out new friends with whom to drink and use drugs and whose use patterns were similar to their old high school friends’. Read and colleagues (2005) found a reciprocal relationship between social influence variables (including peer alcohol use, related attitudes and alcohol offers) and alcohol use over three periods in time from summer prematriculation to the spring of the sophomore year. Overall, their study demonstrates the importance of socioenvironmental factors, including alcohol availability and drinking patterns of peers.

Although prevalence rates for drinking among male and female emerging adults do not differ significantly, studies consistently find that male college students drink more frequently and greater quantities than female students (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002; Wechsler, Dowdall, Maenner, Fledhill-Hoyt, & Lee, 1998). Nevertheless, evidence is inconsistent as to whether increases in drinking differ as a function of gender, especially during the first few years of college (Jackson, Sher, Gotham, & Wood, 2001; Windle, Mun, & Windle, 2005). In addition, risk and protective factors for drinking differ for young men and women (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002; Windle et al., 2005). Further, some studies suggest that selection and socialization effects may also vary for young men and women (Harford, Wechsler, & Muthén, 2002; Lo & Globetti, 1995; McCabe et al., 2005; Slutske et al., 2004). Because of gender differences in prevalence of, risk factors for, and contextual influences on heavy drinking, this study includes an examination of gender differences in the analyses.

All of the research summarized above on peer influences has been conducted on college students. Little research has been carried out on “the forgotten half” (William T. Grant Foundation Commission on Work, Family, and Citizenship, 1988) of emerging adults whose life course does not include going to college. However, socializing with peers is a frequent activity for emerging adults regardless of college status, and many social activities involve the use of alcohol (Arnett, 2000; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the same social factors (i.e., peer modeling and reinforcement and opportunities to drink) also influence drinking among noncollege-attending emerging adults. This study will examine whether peers have similar influences on alcohol use for male and female college students and their noncollege peers.

Prosocial involvement

Less research has focused on the protective effects of prosocial involvement hypothesized by the SDM. Prosocial involvement is hypothesized to increase contact with those who hold prosocial norms and proscriptions against illegal activities. Because alcohol use is an illegal activity until age 21 and heavy drinking is a health risk, it is hypothesized that prosocial involvement will protect against alcohol use. We examine two forms of prosocial involvement: participation in organized religion and volunteer work.

Many studies have found that religiosity, as measured by importance of religion, commitment to religion, and attendance at religious services, has a protective effect on alcohol use and related problems among adolescents and college students (Bahr, Maughan, Marcos, & Li, 1998; Engs, Diebold, & Hansen, 1996; Galen & Rogers, 2004; Mason & Windle, 2002; Nonnemaker, McNeely, & Blum, 2003; Patock-Peckham, Hutchinson, Cheong, & Nagoshi, 1998; Wechsler, Dowdall, Davenport, & Castillo, 1995). One possible explanation for the relationship between religiosity and alcohol use is that certain religions (e.g., conservative Protestant sects) proscribe drinking or heavy drinking and influence beliefs about drinking (Barry & Nelson, 2005; Burkett, 1980; White, 1982). Also, religious participation may lead to interactions with peers and/or adults who disapprove of drinking (Chawla, Neighbors, Lewis, Lee, & Larimer, 2007).

Participation in volunteer work is hypothesized to influence alcohol use through similar mechanisms. Individuals who are engaged in organized volunteer work are likely to be exposed to prosocial norms and to individuals who disapprove of behaviors that are illegal or unhealthy, such as heavy underage drinking. Further, both religious participation and volunteer involvement may serve as proxies for more conventional behavior, which has consistently been linked to less drinking (Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Windle et al. 2005). Such involvements will not only reinforce norms against drinking or heavy drinking, but will also take time away from participating in other types of social activities, which are likely to be more pro-alcohol (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002; Thorlindsson & Bernburg, 2006). Therefore, we expect that involvement in religious and volunteer activities will serve to deter alcohol use (Schulenberg, Bachman, O’Malley, & Johnston, 1994). Whereas studies have focused on specific organizations on college campuses (e.g., fraternities and sororities) that foster heavy drinking (e.g., McCabe et al., 2005; Wechsler et al., 1995), few have focused on other types of organizational involvement that may serve as protective influences against heavy drinking. This study will fill this gap.

Clearly individuals who are more prosocial to begin with, and thus prone to drink less, will be more likely to participate in prosocial activities. Therefore, selection processes are also expected. As hypothesized in the SDM, individuals will seek out fewer opportunities for prosocial activities during periods of transition if they have been engaging in more antisocial behavior in the prior developmental period (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996).

Current Study

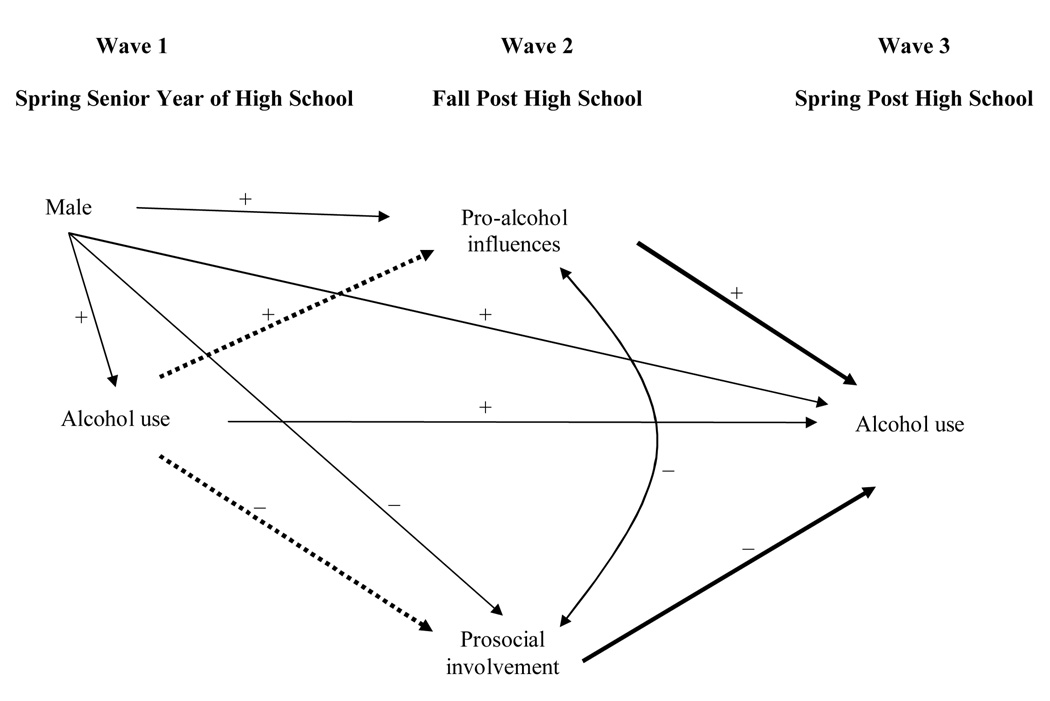

The fact that increases in drinking occur during the developmental period of emerging adulthood for both college-attending and non-attending youth suggests that similar processes or mechanisms may account for these increases. The purpose of this study is to examine whether pro-alcohol influences and prosocial involvements affect changes in alcohol use and whether their effects differ depending on college and residential status. In this study, we use longitudinal data collected in the spring of the senior year of high school (Wave 1; W1), the following fall (Wave 2; W2), and the following spring (Wave 3; W3) from a cohort of both college-attending and non-attending young men and women. The conceptual model is presented in Figure 1. The bolded lines from W2 pro-alcohol peer influences and prosocial involvement to W3 alcohol use test the socialization process, that is, the effects of earlier pro-alcohol influences and prosocial involvement on later alcohol use. In contrast, the dotted lines from W1 alcohol use to W2 pro-alcohol peer influences and prosocial involvement test a selection process, that is, the effects of early drinking behavior on selecting pro-alcohol peers and selecting to participate in religious activities and volunteer work.1

Figure 1. Conceptual model using three waves of longitudinal data.

Note: Dotted arrows represent selection effects and bolded arrows represent socialization effects.

Our hypotheses focus primarily on the socialization paths (with controls for the selection paths) because we are trying to explain why youth experience increases in alcohol use during emerging adulthood. We hypothesize that increases in alcohol use will be due to association with alcohol-using peers and greater opportunities and reinforcement for alcohol use. We also hypothesize that less of an increase in alcohol use will occur for those involved in prosocial activities (i.e., religious activities and volunteer work). As stated earlier, involvement in prosocial activities may reinforce norms against drinking as well as take time away from pro-alcohol activities and vice versa (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). Therefore, we would expect them to be negatively correlated.

Because most of the research has focused on college students, we also explore whether the effects of prosocial involvements and pro-alcohol peer influences operate similarly across four social contexts: 1) going to college and living away from parents, 2) going to college and living with parents, 3) not going to college and living away from parents, and 4) not going to college and living with parents. We hypothesize that prosocial involvement and pro-alcohol peer influence will be invariant for individuals regardless of current social circumstances. We also explore the role of gender across residential and college status. Based on prior research, we expect to see level differences in alcohol use and the factors influencing alcohol use, but we expect the role of gender to be invariant across the four groups.

Method

Design and Sample

The data used for the current analyses were collected as part of the Raising Healthy Children (RHC) project, a longitudinal study of the etiology of problem behavior with an experimental evaluation of an intervention to reduce drug use and other problem behaviors nested within it. Analyses presented below justify combining the experimental and control groups. Details of the larger study are available elsewhere (Catalano et al., 2003; Haggerty, Catalano, Harachi, & Abbott, 1998). The study panel consisted of students from 10 suburban public elementary schools in a Pacific Northwest school district. In the first 2 years of the project (1993 and 1994), 1040 students and their parents (76% of those eligible) consented to participate in the study. Students were drawn from two grade cohorts; 52% of the sample were first-grade students and 48% were second-grade students. Data collection for the project consisted of annual in-person surveys with students, telephone interviews with their parents (through age 18), and survey questionnaires with their teachers (through eighth grade). All procedures were approved by a University of Washington Humans Subjects Review Committee.

The current study organizes data by grade level, utilizing data from when participants, if they were progressing in school according to schedule, were in their last year of high school and their first year post high school. For the older grade cohort, data are from the spring and fall of 2004 and the spring of 2005; for the younger grade cohort, data are from the spring and fall of 2005 and the spring of 2006. Incentives ranged from $15 to $40 depending on the year. The annual spring surveys (W1 and W3) were administered one-on-one by interviewers using laptop computers to record answers and took an average of 50 minutes to complete. For sensitive questions, including questions about substance use, participants completed questions in a self-administered mode. For the survey administered in the fall post high school (W2), about half of the sample completed the survey over the Internet and half were interviewed in person using similar procedures as were used in the spring survey. Analyses of those randomly assigned to administration mode indicated virtually no differences in responses to sensitive questions between modes of administration (Petrie et al., in press) perhaps due, in part, to sensitive questions being self-administered in both modes.2 The fall survey averaged about 36 minutes to complete.

In order to be included in the analysis sample, an RHC participant had to have completed the W2 survey, at which point college and residential status were determined, and had to have made the transition out of high school by that time point.3 Using these criteria, 171 (16%) participants from the original RHC sample were excluded due to not completing the W2 survey (2 of the 171 had died) and 42 (4%) were excluded because they were still in high school at the time of the W2 survey. Two additional cases were excluded because they gave inconsistent answers with regard to living situation, saying they were living with their parents, but also reporting that they were living in a college dormitory. The final analysis sample was 825. Of the analysis sample, 53% were in the experimental condition and 53% were male. The ethnic composition was 82% White, 5% Hispanic, 7% Asian or Pacific Islander, 3 % Black, and 3% Native American. During the spring of high school (W1), the average age was 18.14 (s.d. = 0.33, range = 17.3–19.2). Twenty-nine percent of participants were from households that were low-income at the beginning of the RHC study, defined by whether the youth was enrolled in the free/reduced price lunch program in the first 2 years of the project. When participants were towards the end of the high school period, 54% lived with parents who reported a household income of above $50,000. Comparing the analysis sample and those excluded from the analyses (n = 215) indicated no significant differences on key demographic factors, including age, sex, race/ethnicity (i.e., White vs. nonwhite), and parental household income measured at baseline of the RHC study.

Among the analysis sample, 98% completed the W1 survey and 95% completed the W3 survey. For analyses of differences between residential and college status groups on measured variables, listwise deletion of cases was used. For estimation of structural equation models, missing data were handled using maximum likelihood estimation under the assumption of missing at random, which provides less bias than listwise deletion (Little & Rubin, 2002). The maximum likelihood estimation was implemented using the Mplus procedure MISSING with H1 method (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2004).

Measures

Most variables in the study were based on items from the youth participant surveys, except for household income, which came from the parent interview, and race/ethnicity, which came from school records. Indicators of the alcohol use constructs were measured in the spring surveys (W1 and W3), while indicators of pro-alcohol and prosocial involvements were based on data from the fall survey (W2). As noted above, college and residential status groups were defined by data from the W2 survey.

Alcohol use was a latent variable based on three indicators that were assessed in the spring of the 12th grade (W1) and the following spring (W3). The first indicator was the participant’s report of the frequency of drinking in the prior 30 days. The second indicator was the frequency of “binge drinking” defined as having “4 or more alcoholic drinks in a row” for females and “5 or more” for males in the prior 30 days (Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, 2000). Both frequency items offered a seven-point response. Due to sparse frequencies for some response categories, responses were collapsed into four categories: “none,” “1 or 2 times,” “3 to 5 times,” and “6 or more times.” These measures were treated as continuous in preliminary analyses of group differences on measured variables. In the latent variable analyses, they were treated as ordered categorical (Beauducel & Herzberg, 2006; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1994; Muthén & Asparouhov, 2002; Olsson, 1979). The third indicator, which assessed quantity of drinking, was based on the item, “When you drink alcohol, how many drinks do you usually have?” In order to apply a similar weighting by gender as was used for the binge drinking measure, the response to this question was multiplied by .8 for males. This measure was log transformed to reduce the influence of a few participants who gave high responses and was treated as continuous.

Pro-alcohol influences was a latent construct based on three indicators that reflect peer drinking, peer encouragement to drink, and social opportunities to drink with peers. They were all treated as continuous measures with an approximate normal distribution. The peer drinking indicator was created by taking the mean of two items asking how often in the past month the people “you have been hanging out with the most”: 1) drank alcohol, and 2) got drunk. The five response options for these items ranged from “never” to “very often” and the correlation between the component items was r = .92. Peer encouragement to drink was based on the item, “How often do the people you spend the most time with encourage you to drink alcohol to get drunk?” The five response options for this item ranged from “never” to “very often.” The indicator of social opportunities to drink with peers was measured using the mean of responses to three items asking how often during the past month the respondent had gone to parties or gatherings: 1) “where alcohol was available,” 2) “where there were drinking games,” and 3) “where people were getting drunk.” For each of these items, there were five response options ranging from “never” to “more than 10 times.” The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for this measure was α = .95.

Prosocial involvement was based on participants’ response to questions concerning time spent attending “organized religious activities” and “doing volunteer work not for pay” during the prior 30 days. The measure was coded as 0 for participants who reported doing neither (59%), 1 if they did one or the other (28%; 15% for religious attendance and 13% for volunteer work), and 2 if they did both (13%). The measure was treated as continuous for preliminary analyses of group differences and ordered categorical in the structural equation model analyses. It is important to note that this measure does not reflect prosocial involvements in school (i.e., time spent studying or in class) or paid employment; it reflects prosocial involvement beyond school or work so that it would not be confounded by college status.

Designation of college and residential status captured heterogeneity in status at the beginning of the post-high school period and was based on information from the W2 interview, concurrent with measures of pro-alcohol influences and prosocial involvement. Four categories of college and residential status were created based on whether, at the time of the W2 interview, youth reported that they were: 1) living with their mother or father and 2) attending a 2- or 4-year college.4 Participants who were enrolled in trade or vocational schools (n = 24) or were in military training (n = 8) were assigned to the noncollege groups to differentiate their context from the college environment. The four groups were: 1) attending college and living away from home (e.g., in a dormitory, apartment, etc.) (n = 173; 21%), 2) attending college and living at home (n = 206; 25%), 3) not attending college and living away (n = 170; 21%), and 4) not attending college and living at home (n = 276; 33%). Of those attending college and living away from home, 71% reported that they were living in a college dormitory and 6% said they were living at a sorority or fraternity residence, while the remaining 23% reported living in an apartment, condominium, or house. Of those not attending college and living away from home, 87% reported living in an apartment, condominium, or house; the rest reported a variety of living situations, including military barracks (3%), or having no regular housing situation (10%). Seventy-five percent of the total sample, and over 73% in each of the four groups, reported the same residential and college status at the W3 time point.5

Gender was coded 1 for males and 0 for females. Given that race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES) potentially influence college attendance and living situation, we also control for them in some of the analyses. Race/ethnicity, taken from the school district records, was used as a dummy variable of 1 = White (82%), 2 = Asian (7%), and 3 = other (11%, which included 3% black, 5% Hispanic, and 3% Native American), with other as the reference category. As an indicator of the SES, household income was obtained from parent interviews in the spring of the 11th grade because more parents completed the 11th than the 12th grade interview. However, if the 11th grade variable was missing and the 12th grade variable was available, then the latter was used. Income was dichotomized by whether household income was more than (coded 1; 56%) or less than (coded 0; 44%) $50,000.

Analysis

First, contingency tables examined differences among the four groups by gender, race/ethnicity, and SES composition. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) tested for group differences in alcohol use, pro-alcohol influences, and prosocial involvement, followed by post hoc contrasts. These latter analyses were re-run controlling for race/ethnicity and SES to adjust for selection effects of college entry and residential status (see footnote 1). Although race/ethnicity and SES were significantly related to college attendance and residential status (see Table 1 below), they did not change the association of college status and residential status with alcohol use, pro-alcohol influences, and prosocial involvement. Therefore, we present only the results from the unadjusted analyses in the text.

Table 1.

Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and SES Composition of College and Residential Status Groups

| College away (n=173) | College at home (n=206) | Noncollege away (n=170) | Noncollege at home (n=276) | Group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | χ2 | |

| Male | 41.1a,b | 54.4a | 46.5c | 62.7b,c | 23.34* |

| Race/Ethnic group | 46.56* | ||||

| Asian | 7.5a,b,c | 16.0a,d | 1.8b,d | 2.5c,e | |

| White | 85.5a | 71.8a,b,c | 85.9b | 86.2c | |

| Other+ | 7.0a | 12.2 | 12.3 | 11.3a | |

| Parent’s household | |||||

| income >$50,000 in 11th grade | 65.2a,b | 67.8c,d | 46.4a,c | 48.6b,d | 28.88* |

p < .05

Black, Hispanic or Native American.

Note: Within each row, frequencies with the same superscript are significantly different from one another (p < .05).

For tests of hypothesized relationships among constructs and the test of equivalence of these relationships among the college and residential status groups, four-group multiple-group latent variable models were estimated using Mplus version 3.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2004). In these models, alcohol use at both time points and pro-alcohol influences were treated as latent variables.6 In order to accommodate the modeling of ordered categorical variables of drinking frequency and prosocial involvement, the Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance (WLSMV) adjusted estimator was used. Model fit for the latent variable models was assessed using the mean- and variance-adjusted chi-square statistic (Muthén, du Toit, & Spisic, 2007),7 Root Mean Square Error of Approximation index (RMSEA: Browne & Cudeck, 1993), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI: Bentler, 1990).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models were estimated to assess the fit of the measurement model, measurement invariance across the college and residential status groups, group differences on the means of the latent variables, and the overall associations among model constructs for each group.8 Structural models were used to test hypothesized relationships among model constructs and invariance of hypothesized relationships across college and residential status groups.9 Tests of mediation hypotheses were based on estimates of indirect effects generated with the Mplus Model Indirect command, which computes the product of component paths and Delta method standard errors (Sobel, 1982; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2004).

Based on some prior studies (e.g., Harford, Wechsler, & Muthén, 2002; Harford, Wechsler, & Seibring, 2002; Lo & Globetti, 1995), there was concern that some hypothesized paths may not be invariant across gender. Therefore, we examined the invariance of the measurement and structural models across young men and women. While noting that there might be slight differences in measurement by gender, tests of invariance in the structural models demonstrated evidence of invariance in relationships among model constructs.10 In order to assess level differences in model constructs, gender was included as a covariate in the latent variable analysis and treated as an exogenous variable with specified paths to each model construct in the structural model.

Another concern was pooling study participants who had received the experimental intervention (which was partly designed to teach youth to resist peer influence to drinking alcohol) and those in the control conditions. However, there was evidence of invariance by condition in both the measurement and structural models.11 On the basis of these findings, participants in both the intervention and control conditions of RHC were combined in the analysis.

Results

Group Differences in Means or Frequencies of Measured Variables

Descriptive information on demographic characteristics of the four college and residential status groups is shown in Table 1. There were significant differences by gender among the four groups. For both college attenders and nonattenders, females were more likely to live away from home than males. There were also significant differences in the racial/ethnic and SES composition of the groups. Those who went to college and lived at home were less likely to be White than the other three groups. A relatively higher proportion of both college groups were Asian, particularly the college living at home group. The participants who went to college, compared to those who did not, were more likely to come from higher income families.

As shown in Table 2, there were significant differences among groups in means of all measured study variables. (These differences were also significant after adjusting for the gender, race/ethnicity and SES composition differences reported above; not shown but available from the second author upon request.) At the end of high school (W1), the two groups about to go to college reported less drinking than the noncollege-bound individuals. One year later (W3), college students living away from home had caught up to their noncollege peers in frequency and quantity of drinking, while college students living at home were drinking significantly lower quantities than their peers in the other groups, drinking less frequently than noncollege youths living at home, and binge drinking less frequently than noncollege youth living at home and college students living away from home.

Table 2.

Measured Variables by College and Residential Status Groups

| College away (n=173) |

College at home (n=206) |

Noncollege away (n=170) |

Noncollege at home (n=276) |

Group differences |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (sd)+ | mean (sd) | mean (sd) | mean (sd) | F from ANOVA | |

| Alcohol use W1 | |||||

| Alcohol frequency | 0.60 (0.94)ab | 0.59 (0.96)cd | 1.22 (1.20)ac | 1.03 (1.17)bd | 15.87* |

| Binge drinking | 0.41 (0.81)a | 0.38 (0.80)bc | 0.83 (1.14)ab | 0.61 (0.97)c | 8.79* |

| Alcohol quantity | 2.15 (2.64)ab | 2.07 (2.80)cd | 3.86 (3.68)ac | 3.54 (3.82)bd | 15.01* |

| Pro-alcohol influences W2 | |||||

| Peer drinking | 3.15 (1.22)a | 2.74 (1.15)a | 2.95 (1.21) | 2.89 (1.27) | 3.60* |

| Peer encouragement | 2.25 (1.18)ab | 1.70 (0.90)a | 1.96 (1.16) | 1.88 (1.08)b | 8.41* |

| Opportunities | 2.40 (1.24)a | 2.02 (1.09)a | 2.19 (1.25) | 2.18 (1.16) | 3.30* |

| Prosocial involvement W2 | 0.62 (0.75)a | 0.62 (0.68)b | 0.38 (0.63)ab | 0.51 (0.73) | 4.82* |

| Alcohol use W3 | |||||

| Alcohol frequency | 1.26 (1.13) | 0.97 (1.12)a | 1.22 (1.19) | 1.33 (1.23)a | 3.65* |

| Binge drinking | 0.95 (1.09)a | 0.59 (0.99)ab | 0.85 (1.13) | 0.88 (1.13)b | 3.97* |

| Alcohol quantity | 3.39 (3.03)a | 2.48 (2.82)abc | 3.74 (3.69)b | 3.48 (3.79)c | 4.93* |

p < .05

sd = standard deviation. W1 = Spring during senior year of high school, W2 = Fall post high school, W3 = Spring post high school.

Note: Within each row, frequencies and means with the same superscript are significantly different from one another (p < .05). These analyses were repeated controlling for race/ethnicity and SES. The mean differences on the measured variables across the four groups did not differ from those presented above when these controls were included.

W2 pro-alcohol peer influences were highest for the college students living away and lowest for college students living at home. College students living away from home also reported significantly more peers drinking, greater peer encouragement to drink, and more opportunities to drink than their college peers living at home. Non-college youth who lived at home reported significantly less peer encouragement to drink than college students living away, but significantly more encouragement than college students living at home. In contrast, noncollege youth living away did not differ significantly from any of the other groups in pro-alcohol peer influences, although they reported the second highest scores on all three indicators. The two college groups reported higher levels of W2 prosocial involvement than the noncollege away from home group.

CFA Model

The unconstrained CFA model had good model fit (χ2(61) = 139.86, p < .05, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .08), indicating that latent variables of alcohol use and pro-alcohol influences adequately captured variance in their measured indicators. All factor loadings on latent variables were positive, statistically significant, and of similar magnitude across all groups. For both the W1 and W3 latent alcohol use variables, standardized factor loadings for indicators were above .77 for all groups, and above .65 for the W2 pro-alcohol influences. The constrained CFA model also fit the data well (χ2 (51) = 84.92, p < .05, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06), and there was a nonsignificant difference in fit between the constrained and unconstrained CFA models (Δχ2 (Δ df) = 34.17 (26), p > .05). Thus, the measurement model was invariant across all four groups.

Table 3 presents means for the latent constructs and correlations among model constructs from the constrained CFA model. As was seen for the measured variables, the estimates for the latent variables indicate that the college students living at home had lower W2 pro-alcohol peer influences and lower W3 drinking than the college students living away. Both of the noncollege groups reported more W1 drinking than the college students living away, but were not higher at W3. Pro-alcohol peer influences were also lower among noncollege youth living at home than college students living away.

Table 3.

Factor Correlations for College and Residential Status Groups from the Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model with Factor Loadings Constrained to Equality across Groups

| Alcohol use | Pro-alcohol influences | Prosocial involvement | Alcohol use | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor correlations | Male | W1 | W2 | W2 | W3 |

| College away group | |||||

| Alcohol use W1 | .13 | ||||

| Pro-alcohol influences W2 | .20 | .72* | |||

| Prosocial involvement W2 | −.02 | −.01 | −.09 | ||

| Alcohol use W3 | .20* | .70* | .74* | −.22* | |

| Means of the latent constructs | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| College at home group | |||||

| Alcohol use W1 | .05 | ||||

| Pro-alcohol influences W2 | .10 | .70* | |||

| Prosocial involvement W2 | −.13 | −.27* | −.17* | ||

| Alcohol use W3 | .06 | .76* | .74* | −.26* | |

| Means of the latent constructs | −.13 | −.59* | −.42* | ||

| Noncollege away group | |||||

| Alcohol use W1 | .26* | ||||

| Pro-alcohol influences W2 | .35* | .65* | |||

| Prosocial involvement W2 | .05 | −.31* | −.11 | ||

| Alcohol use W3 | .34* | .55* | .57* | −.23* | |

| Means of the latent constructs | .62* | −.25 | −.08 | ||

| Noncollege at home group | |||||

| Alcohol use W1 | −.03 | ||||

| Pro-alcohol influences W2 | .01 | .76* | |||

| Prosocial involvement W2 | .12 | −.28* | −.30* | ||

| Alcohol use W3 | .03 | .67* | .72* | −.15 | |

| Means of the latent constructs | .42* | −.32* | −.04 | ||

p < . 05. W1 = Spring during senior year of high school, W2 = Fall post high school, W3 = Spring post high school.

Note: significant latent variable means indicate that they are significantly different from the mean level of the college away from home group.

For all groups, there were strong overall correlations between W1 drinking and W3 drinking and between drinking at both time points and pro-alcohol peer influences. Prosocial involvement showed less consistent correlations with other constructs. For college students living away, prosocial involvement was significantly negatively associated with W3 drinking, but not with W1 drinking. For college students living at home and noncollege emerging adults living away, prosocial involvement was significantly negatively associated with both W1 and W3 drinking. For individuals not in college and living away it was significantly negatively associated with W1 drinking, but not W3 drinking. As predicted, prosocial involvement was negatively associated with pro-alcohol peer influences, but significant only for those youth who lived at home. For the two groups living at home, gender was not significantly associated with any other model variables. For college students living away from home, being male was associated with more W3 drinking and, for non-college individuals living, being male was associated with more drinking at both time points and more pro-alcohol peer influences.

Structural Model

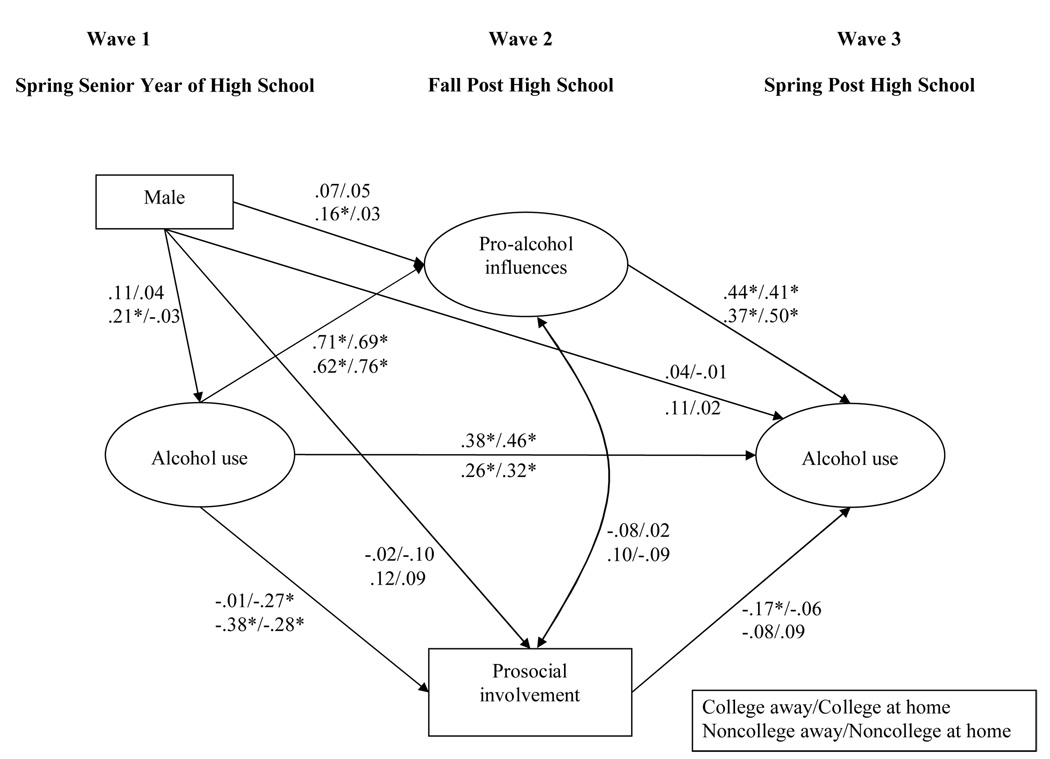

Figure 2 shows the standardized path coefficients for each of the structural paths from the final model in which the structural paths were freely estimated for each group. Table 4 provides estimates for the unstandardized paths and the variances explained in endogenous variables for each group, and the results of tests of invariance on each path. For each group, much of the explained variance in W3 drinking (ranging from 40% for the noncollege away from home group to 66% for the college at home group) was accounted for by the stability path from earlier drinking behavior (W1) and the path from pro-alcohol peer influences (W2). Paths from W1 alcohol use to W2 pro-alcohol peer influences and from W2 pro-alcohol influences to W3 drinking were statistically significant for all four groups. For all groups, the combination of these paths partially mediated the relationship between W1 and W3 drinking as seen in the reduction between the overall association between W1 and W3 drinking found in the CFA model (range in correlations: .55–.76) and the unique paths found in the structural model that is adjusted for pro-alcohol peer influences (range in standardized paths: .26–.46). Also, the indirect effect of W1 drinking through W2 pro-alcohol peer influences on W3 drinking was statistically significant for all groups (range in standardized indirect paths: .23–.38).

Figure 2. Standardized path coefficients for college and residential status groups from the final unconstrained structural model.

Note: * p < .05. Ovals are latent variables while rectangles are measured variables.

Table 4.

Unstandardized Coefficients and Explained Variance in Endogenous Variables for College and Residential Status Groups from the Unconstrained Structural Model and Tests of Difference in Model Fit for the Models in Which Paths Were Constrained and Unconstrained

| College away |

College at home |

Noncollege away |

Noncollege at home |

Constrained vs. unconstrained |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paths | Coefficient (Standard Error) |

Coefficient (Standard Error) |

Coefficient (Standard Error) |

Coefficient (Standard Error) |

Δχ2 |

| Alcohol use W1 | |||||

| → Pro-alcohol influences W2 | .62*(.09) | .41*(.07) | .54*(.11) | .57*(.09) | 8.53* |

| → Prosocial involvement W2 | −.01(.10) | −.25*(.09) | −.41*(.11) | −.29*(.08) | 3.98 |

| → Alcohol use W3 | .37*(.10) | .50*(.12) | .30*(.15) | .35*(.11) | 8.38* |

| Pro-alcohol influences W2 | |||||

| → Alcohol use W3 | .50*(.11) | .75*(.21) | .48*(.16) | .72*(.16) | 8.18* |

| Prosocial involvement W2 | |||||

| → Alcohol use W3 | −.16*(.06) | −.07 (.08) | −.08 (.09) | .10 (.06) | 2.34 |

| Male | |||||

| → Alcohol use W1 | .22 (.16) | .08 (.17) | .39*(.16) | −.06 (.14) | 7.74 |

| → Pro-alcohol influences W2 | .12 (.11) | .06 (.08) | .25*(.12) | .05 (.08) | 8.69* |

| → Prosocial involvement W2 | −.03 (.19) | −.20 (.16) | .23 (.20) | .18 (.15) | 3.47 |

| → Alcohol use W3 | .08 (.11) | −.02 (.13) | .24 (.15) | .04 (.11) | 6.27 |

| Explained variance | R2 | R2 | R2 | R2 | |

| Alcohol use W1 | .01 | .00 | .04 | .00 | |

| Pro-alcohol influences W2 | .52 | .48 | .45 | .58 | |

| Prosocial involvement W2 | .00 | .08 | .13 | .09 | |

| Alcohol use W3 | .63 | .66 | .40 | .56 |

p < .05, W1 = Spring during senior year of high school, W2 = Fall post high school, W3 = Spring post high school.

Note: For each path, there were three degrees of freedom for the chi-square difference test in model fit. The structural model was reanalyzed including race/ethnicity and SES as exogeneous covariates. The results did not change substantially and are not shown, but are available from the second author upon request.

W2 prosocial involvement was negatively predicted by W1 drinking for three of the groups, but only for college students living away from home was there a significant, negative, unique association between W2 prosocial involvement and W3 drinking. The indirect effect of W1 drinking through W2 prosocial involvement on W3 drinking was not statistically significant at the p < .05 level for any group. Thus, there was no evidence that prosocial involvement accounted for a portion of the relationship between high school and post-high school drinking.

Most paths from gender to other model constructs were nonsignificant. However, as shown in the CFA model, being male was associated with more W1 drinking and had a unique, positive association with pro-alcohol peer influences for non-college youth who moved away. Models were also estimated that included race/ethnicity and family income as exogeneous variables. Including these variables as covariates did not change the direction or significance level of any path found for any group in the unconstrained structural model (not shown but available from the second author upon request).

We conducted a set of analyses to test which specific paths differed across the four groups. The structural model in which all paths were constrained to equality across groups (χ2 (57) = 103.88, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06) and the model in which the paths were freely estimated (χ2 (57) = 100.04, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06) both fit the data well. However, the chi-square difference test between the constrained and unconstrained models was statistically significant (Δχ2 (Δ df) = 36.24 (19), p < .05). Constraining and then releasing equality constraints on specific paths indicated that there were significant between-group differences on four paths (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Chi-Square Difference Tests for Contrasts within Pairs of Groups

| Within-group differences |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural paths | College away vs. College at home | College away vs. Noncollege away | College away vs. Noncollege at home | College at home vs. Noncollege away | College at home vs. noncollege at home | Noncollege away vs. noncollege at home |

| Alcohol use W1 | 7.44* | 0.86 | 0.90 | 2.18 | 4.55* | 0.04 |

| → Pro-alcohol influences W2 | ||||||

| Alcohol use W1 | 5.83* | 0.35 | 0.15 | 6.16* | 4.43* | 0.80 |

| → Alcohol use W3 | ||||||

| Pro-alcohol influences W2 | 5.69* | 0.40 | 0.21 | 6.31* | 4.00* | 0.96 |

| → Alcohol use W3 | ||||||

| Male | 0.99 | 1.31 | 2.07 | 5.48* | 0.26 | 8.04* |

| → Pro-alcohol influences W2 | ||||||

p < .05; W1 = Spring during senior year of high school, W2 = Fall post high school, W3 = Spring post high school.

Note: There was one degree of freedom for each chi-square difference test.

For the path from W1 alcohol use to W2 pro-alcohol peer influences, there were significant differences in the magnitude of this association for college students living away compared to college students living at home and between college students living at home and noncollege youth living at home. In both cases the magnitude of this association was smaller for college students living at home (see also Table 4). For the paths from W1 to W3 alcohol use and from W2 pro-alcohol influences to W3 drinking, there were differences between the two college groups and between the college students living at home and the two noncollege groups; the unique association was stronger for the college students living at home. For the path from being male to pro-alcohol influences, there were significant differences between the noncollege youth living away and the two groups living at home, reflecting the stronger association between being male and having pro-alcohol peer influences among noncollege emerging adults who live away from home.

Discussion

The results of this study support prior research and indicate that there are both socialization and selection processes that influence the continuity and discontinuity in drinking during the transition into emerging adulthood (Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1995; Harford & Muthén, 2001; McCabe et al., 2005; Read et al., 2005). These processes are consistent with SDM hypotheses (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996). Higher drinking in high school predicted involvement six months later with peers who drank heavily and reinforced heavy drinking. With our data, we cannot determine whether individuals selected new friends as they left high school or continued to associate with their same high school peers. Nevertheless, the fact that this selection effect was stronger for college youths who moved away, compared to those who stayed home, suggests that there may be some switching of friends, which clearly supports a selection hypothesis.

In addition, we found that peers influence changes in drinking over time, supporting a socialization model. Emerging adults with heavier drinking friends were more likely to increase their drinking from high school (W1) to a year later (W3). Furthermore, the effect of high school drinking on drinking a year later was partially accounted for by pro-alcohol peer influences. Overall, our results confirm those of Read and colleagues (2005) and demonstrate the importance of proximal pro-alcohol peer influences on drinking in emerging adulthood for college students. Our findings extend this prior research by showing that these processes are also important for emerging adults who do not attend college.

In contrast, the effects of prosocial involvement were weaker. In the bivariate associations, there was a significant, albeit modest, negative overall association between prosocial involvement in the fall (W2) and drinking the following spring (W3) for three out of the four groups. However, results from the structural models indicated that the effects of prosocial involvement after high school were not as strong as those for pro-alcohol peer influences. For most individuals, heavy drinking in high school negatively impacted involvement in prosocial activities in emerging adulthood. Nevertheless, only for those who went to college and moved away from home did we see a protective, unique effect on W3 drinking after adjusting for W1 drinking behavior.

That we did not find a protective effect of prosocial involvement in other contexts may be due to our measure not capturing the full range of prosocial opportunities. Including prosocial opportunities at school or work may be important additions to the measurement of this construct and might also better capture the situational control of prosocial involvement on heavy drinking found in tests of routine activities theory (Osgood, Wilson, O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 1996). Also, the dichotomous indicators of religious and volunteer work involvement may not finely differentiate various levels of involvement. In addition, taking into account religious denomination and its norms about drinking when measuring religious participation may be important for delineating the social control aspect of religiosity. Alternatively, it may be that, during emerging adulthood, the influence of pro-alcohol peers is much stronger than the influence of prosocial involvements on drinking behavior (Dowdall & Wechsler, 2002). Our findings are consistent with those of Chawla and colleagues (2007), who found that the effects of religiosity on drinking were no longer significant once perceived approval of peers and personal attitudes were taken into account. However, for college students living away from home, religious attendance and volunteer work were significantly related to later drinking even when peer influences were included in the model.

We had predicted that the association between pro-alcohol influences and prosocial involvement would be negative. Although it was significantly negative for the two groups living at home in the bivariate analyses, it was not significant for any of the groups in the structural model. Again, measurement of the prosocial construct may account for the absence of a stronger relationship.

In accord with prior research (e.g., Harford, Wechsler, & Muthén, 2002; White et al., 2006), our findings suggest that those emerging adults who go to college but remain living with their parents are protected from associating with heavy drinking peers and also from increasing their drinking in emerging adulthood. These youth maintained the lowest levels of drinking, reported the highest stability in alcohol use from high school (W1) to the following year (W3), and displayed the weakest selection effects compared to their peers who moved away and peers who stayed home but did not go to college. One explanation may be that those individuals who went to college and stayed home experienced less discontinuity as they entered emerging adulthood than their peers because their living situation remained the same and they continued to attend school (Schulenberg, Maggs, & O’Malley, 2003). In other words, upon high school graduation, they did not experience a significant developmental transition that included new roles and contexts (Schulenberg et al., 2004). Therefore, compared to their peers, they may have experienced less self exploration, identity confusion, and stress, all of which can increase the risk for heavier drinking (Arnett, 2005). In addition, sources of social control (e.g., parental monitoring), which generally decrease during emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2005), may not have decreased as much as those for other emerging adults following high school. Yet, the noncollege emerging adults who lived with their parents did not experience a protective effect from living at home. Furthermore, our prior research indicates that parental monitoring continues to exert an effect on individuals even after they leave home (White et al., 2006; see also Wood, Read, Mitchell, & Brand, 2004). In these analyses, we did not examine whether preexisting intra-individual or family environment factors influenced the decision to stay home. Yet, we know from prior research that preexisting differences among students account for differences in the types of residences that college students select (Baer, 1994; Harford & Muthén, 2001; Harford, Wechsler, & Muthén, 2002). Pre-existing differences also affect alcohol use. Therefore, social background differences, which may continue to operate as concurrent influences on opportunities and behaviors after high school, represent a rival hypothesis for the college/residential status differences found here.

As stated earlier, emerging adulthood is a stage in the life cycle in which there is the most diversity of social roles and choices (Arnett, 2005). Individuals move more during emerging adulthood than any other time in their lives (Arnett, 2000). Harford and Muthén (2001) found a significant effect of moving away regardless of when it happened and suggested that it is exposure to high-risk environments rather than the short-term liberalization from parental control, which affects drinking behavior. Therefore, what will happen to these college students living at home when they leave home is open to question and will probably depend on the reasons that they move and the timing of the move. Those who wait until they are older will have less access to pro-alcohol drinking influences than those who move in their early 20s. In addition, those who move to get married will mostly likely reduce their drinking (Bachman et al., 1997). Interestingly, a large proportion of youth move back with their parents at some point during emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000). Whether the move back engenders reductions in drinking is an empirical question to be addressed by future research.

Overall, we found few gender differences in the mechanisms affecting drinking behavior. However, among youth who did not go to college but moved away from their parents, young men reported greater pro-alcohol peer involvement in emerging adulthood than young women. Other research indicates that noncollege young men are at high risk for heavy drinking and drinking problems as they enter young adulthood (White et al., 2005). Whether the noncollege men who stayed home in our sample will increase their drinking when they move away remains a question for future research. Nevertheless, the recent literature suggests that it is important to target prevention efforts on noncollege emerging adults, especially young men (Harford, Yi, & Hilton, 2006; White et al., 2005). Studies have found that those emerging adults who do not attend college and live away from home often live with spouses, which tends to reduce heavy drinking, especially for women (Bachman et al., 1997). However, the gender difference we found among those who moved away but did not attend college cannot be explained by marital status because very few of our participants were married a year after high school (N = 12).

This study extended the literature on social circumstances and drinking behavior in emerging adulthood and had several strengths. It was based on prospective data, collected over a short follow-up window. The study included youth who went to college and those who did not. The college sample came from several colleges rather than only one school and included a large proportion of students who were not from research-oriented universities, where much of the research on college students typically takes place (Dowdall & Wechsler, 2002). In addition, this study examined two mechanisms that account for changes in alcohol use during emerging adulthood and whether they are similar or different depending on social circumstances. Finally, this is one of a few studies to examine whether prosocial activities play a role in influencing drinking behavior in emerging adulthood.

Some limitations should be noted. Although one of few studies to compare emerging adults across educational and residential contexts, this study only partially captures the full range of heterogeneity and instability in social contexts during this time period. First, we did not account for what may be important variations in living situation (e.g., with roommates or an intimate partner, on or off campus) due to the considerable heterogeneity in these situations and sample size restrictions (Harford, Wechsler, & Muthén, 2002). Second, there was variation in living situation and educational status from the fall to the spring for about one fourth of the sample, which is consistent with the literature on emerging adults (Arnett, 2000). However, when we reanalyzed the data excluding those who changed their residential or college status during this period, the results remained consistent in terms of the direction and statistical significance of the associations. Third, we blurred group differences by combining 2-year and 4-year college students and full-time and part-time students, and by combining full-time and part-time workers with those not employed in the noncollege group, again due to sample size restrictions. We also included vocational school students with non-students rather than college students because we were specifically interested in effects of the college environment. Therefore, our findings regarding similarity of processes across groups should be interpreted cautiously due to the heterogeneity within groups. Given sample size limitations, we also did not take into account differences among colleges. However, studies have found that colleges campuses have differential effects on drinking behavior and alcohol-related opportunities depending on location, size, student demographics (e.g., race, sex, age), type of school (2-year or 4-year), presence of fraternities and sororities, religious orientation, presence of athletics, types of housing, and alcohol availability on campus and in the surrounding community (Barry & Nelson, 2005; Dowdall & Wechsler, 2002; Jackson et al., 2006; Presley et al., 2002; Timberlake et al., 2007). In addition, individuals select certain schools because of these characteristics (Baer, 1994; Barry & Nelson, 2005; Harford & Muthén, 2001; Harford, Wechsler, & Muthén, 2002) and we did not control for these selection factors. Further research with larger samples is needed to address the full range of variation in contextual factors.

The sample came from one suburban community and was predominantly White. Although we controlled for race/ethnicity, which was related to college attendance, we did not have sufficient numbers of minority groups to test models separately by race/ethnicity. Thus, our findings need to be replicated in more diverse samples. Further, although in supplementary analyses we controlled for SES and race, which also affected college attendance and living arrangements, we did not control for other factors, such as family, neighborhood, and high school characteristics that could directly and indirectly affect educational opportunities and residential choices. For example, there are characteristics of families, neighborhoods, and high schools that affect whether youth are encouraged to go to college, how well prepared they are to get into college, and how well they know about their options (e.g., scholarships and loans). Finally, we focused on contextual factors and did not control for intra-individual factors that might affect the selection and socialization processes, such as peer and parental relationships, family background, academic motivation, and other problem behaviors. Therefore, future studies should examine the interactions of individual and environmental factors.

The results of this study have important implications for prevention. They suggest that interventions need to focus on emerging adults as they move away from home. These efforts should target peer influences and reduce opportunities for heavy drinking. One promising approach with college students has been the use of brief personalized feedback interventions that reduce perceptions of pro-alcohol peer norms (for reviews see Walters & Neighbors, 2005; White, 2006). Few studies have tested the effects of such interventions on noncollege youths (see Barnett, Monti, & Wood, 2001 for an exception). Therefore, more research is needed to test the efficacy of interventions with noncollege emerging adults and to determine the most appropriate venues for targeting them. Finally, increasing prosocial involvements of college students living away from home may be a promising direction for preventive intervention.

In conclusion, we found that two mechanisms influencing changes in drinking operate the same for college students as their noncollege peers during the first year after high school. Nevertheless, developmental processes may differ over time. Schulenberg, Maggs, and O’Malley (2003) suggested that divergence in life paths will increase as emerging adulthoods enter young adulthood and experience a wide range of diverse situations and roles. With time, greater differences in drinking between college attenders and non-attenders are expected to emerge (Muthén & Muthén, 2000; White et al., 2005). Therefore, future research requires a longer follow-up window in order to understand developmental changes in drinking and differentiate those who mature out of heavy drinking from those who do not.

Acknowledgments

The writing of this paper was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA08093; DA17552). The authors want to thank Eun Young Mun and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Footnotes

There are also selection and socialization effects that determine which individuals go to college and whether youth live at home following high school, as well as whether youth use alcohol during high school. Further, preexisting differences among students may account for differences in the types of residences college students select, as well as in the types of schools that they choose to attend (Baer, 1994; Harford & Muthén, 2001; Harford, Wechsler, & Muthén, 2002), which, in part, may determine exposure to pro-alcohol influences in college. However, instead of attempting to predict an individual’s college or residential status or initial drinking level, in this study we focus on whether the processes that influence changes in drinking during the transition from high school into emerging adulthood are similar or different for youths depending on their college and residential status during this transitional period.

In fall of 2004, we compared responses on 29 measures of substance use, risky sexual behavior, drug and alcohol use expectancies, and peer and family substance-use-related behavior by both assigned mode and completed mode. We used a sample of 357 participants who were assigned to either the web-first or in-person first condition and completed a web or in-person survey. Three-fourths (75%) of those assigned to web completed by web and 88% of those assigned to in-person completed in-person. Only 1 out of 29 measures (reported marijuana use in the prior 30 days) showed a statistically significant difference (p < .05) between those assigned to the in-person mode versus those assigned to the web mode. Two of the 29 measures compared by completed mode showed a significant difference (alcohol problems and report of a family member having a drinking problem) (Petrie et al., in press).

It is important to recognize that some study participants made the transition out of high school earlier. Seventeen percent had dropped out of high school and 5% had either graduated early or received a General Equivalency Diploma (GED). Given that high school dropouts drink more than their peers who graduate (Eggert, & Herting, 1993), we examined differences between high school dropouts and other youth who did not go to college in terms of drinking in both spring assessments (W1 and W3). There were no significant differences in drinking at either point in time. Therefore, there is justification for combining the dropouts with the high school graduates who did not go to college. Because those still in high school at the fall post high school (W2) were eliminated from the analysis, those off grade at the time of the 12th grade assessment were not included in the analysis.

Most (81%) of the college students were full-time students (89% of those living away from home and 74% of those living at home). Three-fourths (73%) of those going to school part-time were employed (36% worked more than 30 hours a week in the past month); 50% of those going to school full-time were employed (10% worked more than 30 hours in a week in the past month). Therefore, a small percentage of those classified as college students were part-time students, who also held full-time jobs.

We also tested the analysis models eliminating those individuals who changed college and/or resident status from the fall to the following spring and the results remained unchanged. We, therefore, present the results from the full sample in the manuscript.

Because some prior studies (e.g., Slutske et al., 2004) suggest that the relationship between college status and drinking may differ by how drinking is measured (e.g., frequency, quantity, binge drinking), we re-ran the SEM models separately for each alcohol measure as a single indicator. The major findings were the same across the different measures in terms of the direction and statistical significance of associations, suggesting that, for the variables examined in this study, the same processes influence changes in several aspects of drinking behavior across the four groups. The results from these analyses are available from the second author upon request.

Both model chi-square and degrees of freedom for the model fit chi-square test are mean- and variance-adjusted when using the WLSMV estimator. Thus, the degrees of freedom used for the significance test do not correspond in a straightforward way with the numbers of measured variables and estimated parameters. This leads to some values that may appear counter-intuitive (e.g., nested models where the estimated degrees of freedom for the constrained model are the same or fewer than for the unconstrained model). Differences in model fit of nested models were based on the derivatives difference test (Satorra, 2000; Satorra & Bentler, 1999). The derivatives difference test does not correspond directly with the differences in estimated chi-square and degrees of freedom between the constrained and unconstrained models.

In these models, the metric of the factor loadings for the alcohol use constructs was set by fixing the loadings of the alcohol frequency indicators to one, while the loading of the peer drinking indicator was set to one and used as a reference indicator for the pro-alcohol influences construct. To assess measurement invariance, the fit of an unconstrained model, in which factor loadings, thresholds of ordinal variables, and intercepts of continuous variables were allowed to vary across groups, was compared to the fit of a constrained model in which cross-group equality constraints were placed on these parameters. In the constrained model, the means of the latent variables were set to 0 for the college living away from home group and freely estimated for the other three groups.

To test the structural model, first, an unconstrained structural model, in which specified structural paths were allowed to vary across the four groups, was estimated to test the significance of hypothesized relationships for each of the four groups. A test of overall invariance of the structural model was based on comparison between the fit of the unconstrained model and a constrained model in which cross-group equality constraints were placed on all specified paths. Next, invariance of individual paths across the four groups was tested and then, for those paths that varied significantly across the four groups, contrasts between pairs of groups were assessed.

CFA models showed a significant difference in fit across the constrained and unconstrained models (Δχ2 (Δ df) = 31.64 (9), p < .05) with the loadings of the number of drinks per occasion indicators on the alcohol use constructs slightly higher for males than females. However, factor loadings from the unconstrained model showed configural invariance: all factor loadings were significant and positive for both groups, and the fit of the constrained CFA model was good (χ2 (21) = 62.83, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .07). While noting that there might be slight differences in measurement by gender, tests of invariance in structural models showed nonsignificant change in fit between the constrained and unconstrained structural models (Δχ2 (Δ df) = 4.67 (4), p > .05), demonstrating evidence of invariance in relationships among model constructs. Due to the evidence of measurement noninvariance by gender, additional paths from gender to specific indicators of alcohol use were tested. While specific paths from gender to alcohol use quantity did slightly improve model fit, adding these paths did not change substantive findings of the study and the more parsimonious models, which were well within the standards of good model fit, are shown here.

There was evidence of invariance by condition in both the CFA model (Δχ2 (Δ df) = 7.22 (7), p > .05) and structural model (Δχ2 (Δ df) = 4.93 (4), p > .05).

The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/dev/

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Student factors: Understanding individual variation in college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002 Suppl. 14:40–53. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. High risk drinking across the transition from high school to college. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr SJ, Maughan SL, Marcos AC, Li B. Family, religiosity, and the risk of adolescent drug use. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1998;60:979–992. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Monti PM, Wood MD. Motivational interviewing for alcohol-involved adolescents in the emergency room. In: Wagner EF, Waldron HB, editors. Innovations in adolescent substance abuse interventions. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Pergamon/Elsevier Science; 2001. pp. 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Barry CM, Nelson LJ. The role of religion in the transition to adulthood for young emerging adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Beauducel A, Herzberg PY. On the performance of Maximum Likelihood estimation versus means and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Structural Equation Modelingq. 2006;13(2):186–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fix indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Burkett SR. Religiosity, beliefs, normative standards, and adolescent drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1980;41:662–671. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1980.41.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. Response from authors to comments on "Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs.". Prevention and Treatment. 2002:5. Article 20. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Mazza JJ, Harachi TW, Abbott RD, Haggerty KP, Fleming CB. Raising healthy children through enhancing social development in elementary school: Results after 1.5 years. Journal of School Psychology. 2003;41:143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla N, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Attitudes and perceived approval of drinking as mediators of the relationship between the importance of religion and alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:410–418. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Kasen S, Chen H, Hartmark C, Gordon K. Variations in patterns of developmental transmissions in the emerging adulthood period. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:657–669. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley JE. Educational status and drinking patterns: How representative are college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:10–16. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdall GW, Wechsler H. Studying college alcohol use: Widening the lens, sharpening the focus. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002 Suppl 14:14–22. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggert LL, Herting JR. Drug involvement among potential dropouts and "typical" youth. Journal of Drug Education. 1993;23:31–55. doi: 10.2190/9RCJ-DTYE-KL5L-HDRA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engs RC, Diebold BA, Hansen DJ. The drinking patterns and problems of a national sample of college students, 1994. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;41:13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Galen LW, Rogers WM. Religiosity, alcohol expectancies, drinking motives and their interaction in the prediction of drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:469–476. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfroerer JC, Greenblatt JC, Wright DA. Substance use in the US college-age population: Differences according to educational status and living arrangement. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:62–65. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty KP, Catalano RF, Harachi TW, Abbott RD. Description de l'implementation d'un programme de prévention des problemes de comportement á l'adolescence. (Preventing adolescent problem behaviors: A comprehensive intervention description) Criminologie. 1998;31:25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Muthén BO. Alcohol use among college students: The effects of prior problem behaviors and change of residence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:306–312. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Wechsler H, Muthen BO. The impact of current residence and high school drinking on alcohol problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:271–279. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Wechsler H, Seibring M. Attendance and alcohol use at parties and bars in college: A national survey of current drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:726–733. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]