Closing the gap between patients’ expectations that harmful errors will be disclosed to them and current practice requires understanding the unique challenges that individual specialties, such as radiology, face related to disclosure, and using this information to help physicians communicate with patients more effectively following errors.

Abstract

Purpose:

To assess radiologists’ attitudes about disclosing errors to patients by using a survey with a vignette involving an error interpreting a patient's mammogram, leading to a delayed cancer diagnosis.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted an institutional review board–approved survey of 364 radiologists at seven geographically distinct Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium sites that interpreted mammograms from 2005 to 2006. Radiologists received a vignette in which comparison screening mammograms were placed in the wrong order, leading a radiologist to conclude calcifications were decreasing in number when they were actually increasing, delaying a cancer diagnosis. Radiologists were asked (a) how likely they would be to disclose this error, (b) what information they would share, and (c) their malpractice attitudes and experiences.

Results:

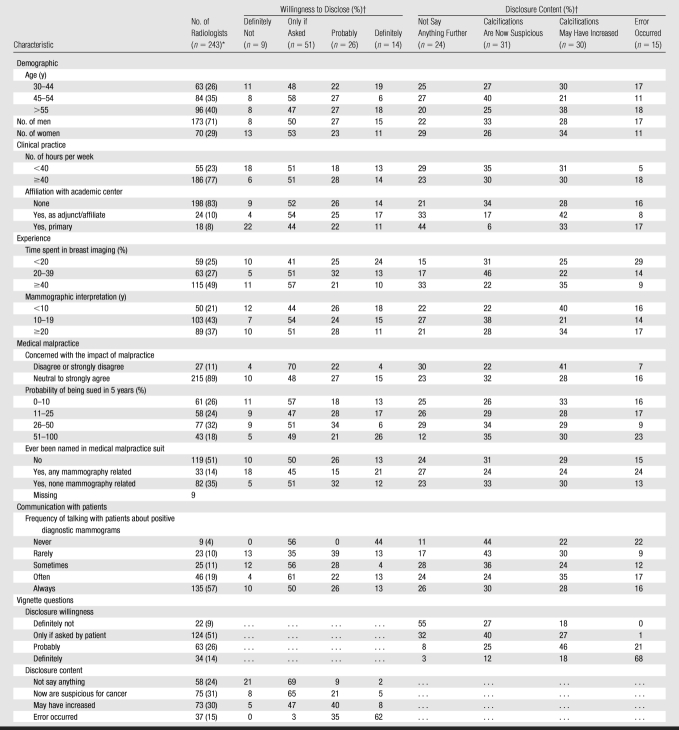

Two hundred forty-three (67%) of 364 radiologists responded to the disclosure vignette questions. Radiologists’ responses to whether they would disclose the error included “definitely not” (9%), “only if asked by the patient” (51%), “probably” (26%), and “definitely” (14%). Regarding information they would disclose, 24% would “not say anything further to the patient,” 31% would tell the patient that “the calcifications are larger and are now suspicious for cancer,” 30% would state “the calcifications may have increased on your last mammogram, but their appearance was not as worrisome as it is now,” and 15% would tell the patient “an error occurred during the interpretation of your last mammogram, and the calcifications had actually increased in number, not decreased.” Radiologists’ malpractice experiences were not consistently associated with their disclosure responses.

Conclusion:

Many radiologists report reluctance to disclose a hypothetical mammography error that delayed a cancer diagnosis. Strategies should be developed to increase radiologists’ comfort communicating with patients.

© RSNA, 2009

Introduction

Greater openness with patients about harmful errors is recommended. Many ethicists and professional organizations endorse disclosure of harmful errors to patients (1–4). The Joint Commission's accreditation standards now require that patients be informed about unanticipated outcomes (5). In response, many hospitals are developing disclosure programs. Yet, recent studies suggest that disclosure of harmful medical errors to patients is the exception rather than the rule (6–12).

While disclosing errors is difficult for any physician, radiologists face unique disclosure challenges, especially those who interpret mammograms (13). Many women have undergone prior mammography examinations, establishing an archive that can be scrutinized when cancer is diagnosed (14). While mammograms classified as having false-negative or false-positive results on the basis of standard definitions may not represent errors in interpretation, patients may still worry that there has been a delay in diagnosis or that an unnecessary biopsy was performed (15). Furthermore, some adverse events in mammography are a result of interpretive errors (16). Talking with patients about such errors is difficult in the current medical-legal environment. Failure to accurately diagnose or a delayed diagnosis of breast cancer are the most common causes of malpractice litigation and radiologists are the most commonly named defendants (17). As a result, fear of litigation is high among breast imagers, which may be exacerbating a shortage of qualified mammographers (18–20). This fear of litigation may also inhibit physicians from communicating more openly with patients about adverse events and errors in radiology (21). Finally, many radiologists do not have the longitudinal patient-provider relationships or prior communication skills training that can help with these difficult conversations (22).

Communicating effectively with patients following errors could enhance patient satisfaction and trust in future health care encounters (23,24). While it may seem counterintuitive, effective disclosure may also reduce the likelihood of malpractice claims (25,26). Creating programs to promote communication with patients about errors in mammography requires understanding radiologists’ attitudes toward disclosure. Yet, to our knowledge, no prior studies have explored radiologists’ willingness to disclose errors to patients, nor has this information been linked to radiologists’ personal experience with previous malpractice lawsuits. We sought to assess radiologists’ attitudes about disclosing errors to patients by using a survey with a vignette involving an error interpreting a patient's mammogram, leading to a delayed cancer diagnosis.

Materials and Methods

Overview

All radiologists who interpreted screening or diagnostic mammographic examinations between 2005 and 2006 at seven geographically distinct Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) sites were invited to participate in a self-administered survey through the mail. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all seven BCSC registry sites and the BCSC Statistical Coordinating Center. All procedures were Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant, and all registries and the Statistical Coordinating Center received a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality and other protection for the identities of physicians and facilities who are subjects of this research (27). Radiologists were informed that their survey responses would remain confidential.

Survey Content and Validation

The survey included items on demographics, practice characteristics, and experience in general radiology and breast imaging. The survey was 10 pages long and required 10–15 minutes to complete. A copy of the survey is available online (http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/collaborations/favor_ii_mammography_practice_survey.pdf).

To assess radiologists’ attitudes about disclosing errors to patients, the survey contained a vignette involving an error interpreting a patient's mammogram, leading to a delayed cancer diagnosis:

“A diagnostic mammogram for a new palpable lump shows an obvious malignant lesion. You realize a mistake was made in your prior interpretation of this woman's last screening mammogram. Prior films had apparently been put up in reverse order, and you mistakenly concluded that the calcifications were decreasing in number when they were actually increasing. Your prior incorrect interpretation has resulted in a delayed diagnosis.”

This vignette was chosen on the basis of our prior validated work (9,28,29), which studied how over 3000 physicians in internal medicine, surgery, and pediatrics would disclose harmful error to patients, and sought to portray a clear-cut mammography error. To address content- and criterion-related validity, the survey was developed by an expert panel of radiologists, epidemiologists, biostatisticians, health services researchers, educational psychologists, and experts in patient-provider communication, ethics, and health law. The survey was then pilot-tested to address construct validity among radiologists working in breast imaging who were not associated with the BCSC.

The vignette was followed by questions addressing two distinct constructs of physician disclosure attitudes found in our prior work (9,28):

First, general willingness to disclose the hypothetical error to the patient (disclosure willingness) was assessed. The vignette was followed by the question, “How likely would you be to disclose this error to the patient?” Four closed-ended response options were provided: (a) “Definitely not disclose,” (b) “Disclose only if asked by the patient,” (c) “Probably disclose,” or (d) “Definitely disclose.”

Second, the specific information that respondents would disclose to the patient about the event (disclosure content) was assessed by using a theory-driven approach derived from our prior work. After the disclosure willingness question above, the survey continues with the following: “You tell the patient that today's diagnostic work-up shows calcifications that are suspicious for cancer. Which of the following statements most closely resembles what you would say to the patient regarding the error in interpreting their prior examinations?” Four closed-ended response options were provided, reflecting increasing disclosure content: (a) “I would not say anything further to the patient regarding the error,” (b) “The calcifications are larger and are now suspicious for cancer,” (c) “The calcifications may have increased on your last mammogram, but their appearance was not as worrisome as they are now,” or (d) “An error occurred during the interpretation of your last screening mammogram, and the calcifications had actually increased, not decreased in number.”

The survey included three questions exploring radiologists’ experiences with and attitudes about medical malpractice: “I am concerned about the effect medical malpractice is having on how I practice mammography” (a five-point scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree), whether they had been named in a malpractice suit (yes or no), and “If you were to interpret mammograms on a regular basis, what do you think is the probability of a new medical malpractice suit being filed against you in the next 5 years?” Other relevant survey questions include practice environment, experience with interpreting mammograms, how often they personally talk with patients about positive and negative diagnostic mammographic results, administrative time, and sociodemographics (age and sex).

Radiologist Survey Data Collection

Survey mailing and collection was handled by individual BCSC sites to maintain confidentiality. Surveys were mailed to radiologists between January 2006 and September 2007, depending on each site's funding mechanism and institutional review board status. Surveys were distributed in four sites (Colorado, North Carolina, New Hampshire, and Washington) beginning in 2006, and in the remaining three sites (California, New Mexico, and Vermont) in 2007. Study managers and principal investigators at each site made a minimum of three attempts to contact radiologists through the mail and/or personal calls to maximize local study participation. Incentives to complete the survey varied among the sites, and included gift cards worth $25–$50 and American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System manuals (30).

Survey data were double-entered at each site and discrepancies were corrected. Anonymized data were then sent to the BCSC Statistical Coordinating Center for pooled analyses.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated frequencies of radiologists’ sociodemographics, practice type, practice experience, medical malpractice perceptions or experience, and frequency of talking with patients about positive or negative diagnostic mammographic results, stratified by the response to the disclosure questions.

To simplify analyses, we dichotomized the disclosure willingness and disclosure content questions. Lower disclosure willingness included the response options “definitely not disclose” and “disclose only if asked by the patient,” and higher disclosure willingness included “probably disclose” and “definitely disclose.” Lower disclosure content included “would not say anything further” and “the calcifications are larger and now suspicious for cancer,” whereas higher disclosure content included “the calcifications may have increased” and “an error happened.” We calculated χ2 tests and tests for trends for bivariate relationships between higher and lower disclosure willingness and disclosure content and radiologist characteristics.

To evaluate the adjusted relationship between higher disclosure content and/or disclosure willingness and radiologists’ characteristics, we fit multivariable log-binomial generalized linear regression models (31). Radiologist characteristics that were significant at P = .1 in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariable models. Owing to missing covariate data (percentage of time spent in breast imaging [n = 6], talk with patient about positive diagnostic examinations [n = 5], and probability of being sued [n = 3]), this analysis was restricted to 229 radiologists. Frequency of talking with patients about positive diagnostic mammographic results was included in the model, even though it was not significant in the bivariate analysis because it was an a priori hypothesis of interest. Since radiologists’ age and years of experience interpreting mammographic examinations are highly correlated, the model included radiologists’ years of experience because it was considered to be more scientifically meaningful. Adjusted relative risks and Wald 95% confidence intervals from these analyses are reported.

All analyses were performed by using software (SAS for Windows, version 9; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All reported P values are two-sided, with P < .05 being used to assess the significance of associations.

Results

Characteristics of Participating Radiologists

Two hundred forty-three (67%) of 364 radiologists returned the survey and responded to the disclosure vignette question. The characteristics of these 243 survey respondents are provided in Table 1. Most were men (71%), practiced radiology full time (77%), and did not have a primary affiliation with an academic medical center (83%). The respondents had considerable experience in mammography: approximately one-half spent 40% or more of their time working in breast imaging, and 79% had 10 or more years of experience interpreting mammograms.

Table 1.

Radiologists’ Demographics and Clinical Practice Characteristics According to Response to Disclosure Questions

Note.—Missing values <10% for all questions.

* Numbers in parentheses are percentages of raw data.

† Questions fully expanded in text.

Malpractice Attitudes and Experiences

Concern regarding malpractice was high among respondents. Seventy-four percent were concerned with the effect that medical malpractice is having on how they practice mammography. Radiologists’ perception of their risk was high for a malpractice lawsuit being filed against them in the next 5 years if they were to continue interpreting mammograms on a regular basis, with 50% estimating the risk as being higher than 25%. Forty-nine percent had been previously sued for malpractice; 14% had been named in a malpractice suit that was specifically related to mammography (32).

Regarding their communication with patients about diagnostic mammographic examinations, 76% reported they “often” or “always” talked with patients about positive diagnostic mammographic results, and 46% often or always talked with patients about negative diagnostic mammographic results.

Response to the Disclosure Vignette

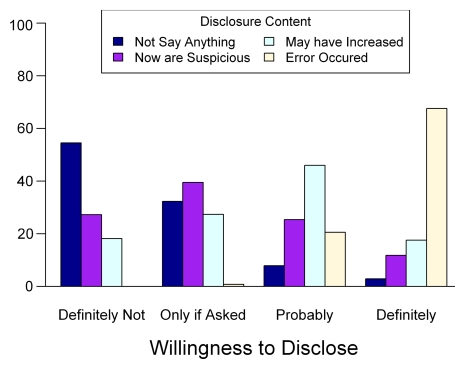

When asked how likely they would be to disclose this hypothetical mammography error to the patient (disclosure willingness), 9% reported they would “definitely not disclose this error,” 51% would disclose this error “only if asked by the patient,” 26% would “probably” disclose this error, and 14% would “definitely” disclose this error. When asked what language most closely resembles what they would say to the patient regarding the error once they have alerted the patient that that day's diagnostic workup is suspicious for cancer (disclosure content), 24% would “not say anything further to the patient,” 31% would tell the patient “the calcifications are larger and now are suspicious for cancer,” 30% would state “the calcifications may have increased on your last mammogram, but their appearance was not as worrisome as they are now,” and 15% would tell the patient “an error occurred during the interpretation of your last mammogram, and the calcifications had actually increased in number, not decreased.” The Figure shows the concordance between respondents’ disclosure willingness and the disclosure content.

Relationship between disclosure willingness and disclosure content. Disclosure vignette is in text.

Predictors of Higher Disclosure Willingness and Disclosure Content

In bivariate analyses, higher disclosure willingness was strongly associated with higher disclosure content. For example, 85.3% of respondents with the highest disclosure willingness (“would definitely disclose”) chose a disclosure statement with higher disclosure content (“may have increased” or “error occurred”) compared with 18.2% of respondents with the lowest disclosure willingness (“would definitely not disclose”) (Table 2, Figure).

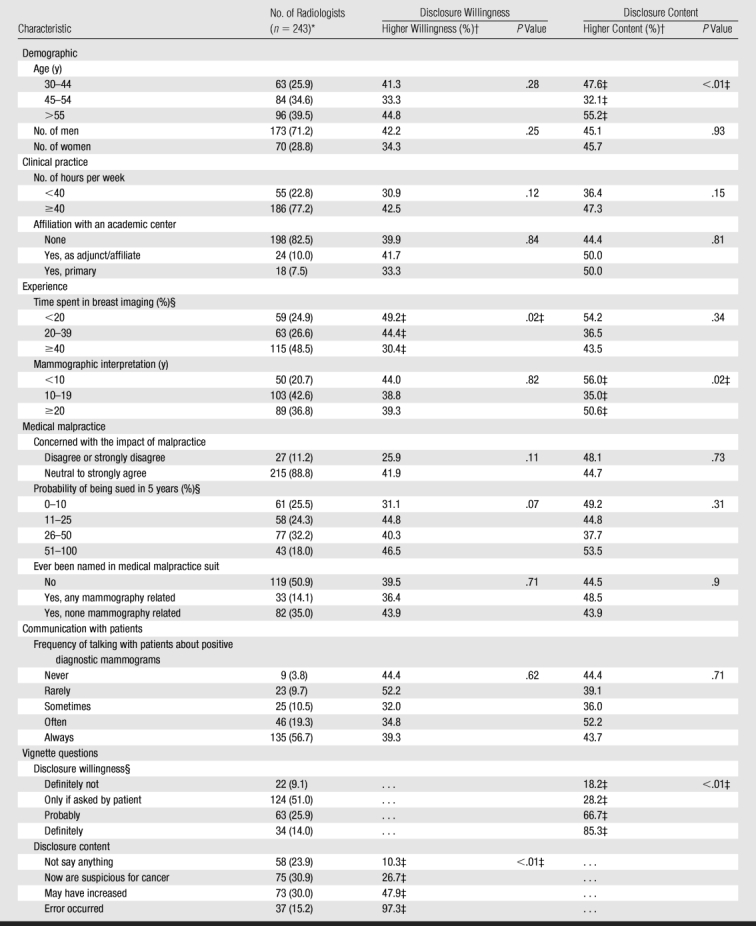

Table 2.

Evaluation of Relationship between Radiologist Characteristics and Positive Response to Disclosure Questions

* Numbers in parentheses are percentages of raw data.

† Higher disclosure willingness included response options “I would probably disclose this error” and “I would definitely disclose this error.” Higher disclosure content included “The calcifications have increased on your last mammogram, but their appearance was not as worrisome as they are now,” and “An error occurred during the interpretation of your last mammogram, and the calcifications had actually increased, not decreased in number.”

‡ Significant difference between groups at P = .05.

§ P value for these variables assumes linear test for trend; all other P values are calculated by using the χ2 test.

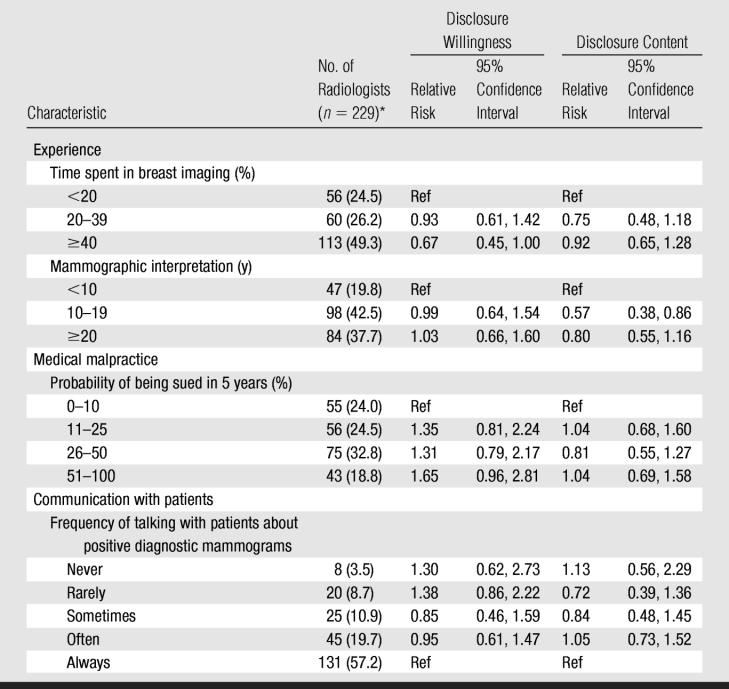

No consistent relationship was found between malpractice attitudes or experiences and either disclosure willingness or disclosure content. Neither the level of concern about the effect that malpractice is having on the practice of mammography nor having been sued previously were associated with disclosure willingness or disclosure content. Respondents who thought the likelihood of being sued for malpractice in the next 5 years was greater than 50% were more likely to have higher disclosure willingness in both bivariate (P = .07) and multivariate analysis (relative risk, 1.65; 95% confidence interval: 0.96, 2.81) compared with those who thought the probability of being sued was less than 10% (Table 3). However, no relationship was present between respondents’ estimates of the likelihood of being sued and disclosure content in either bivariate or multivariate analysis.

Table 3.

Analysis of Multivariate Log-Binomial Regression Models Exploring Relationship among Study Variables

Note.—Owing to missing covariate data (percent breast imaging [n = 6], talk with patient about positive diagnostic exams [n = 5], and probability of being sued [n = 3]), this analysis was restricted to 229 radiologists. Ref = reference group.

* Numbers in parentheses are percentages of raw data.

A U-shaped relationship was found between respondents’ age and years of mammography experience and their self-reported disclosure content. Those who reported 10–19 years of mammographic interpretation had lower disclosure content in the bivariate analysis (P = .02), compared with those with less than 10 and more than 20 years of mammographic interpretation. In the multivariate analysis, those who reported 10–19 years of mammographic interpretation still had low disclosure content (relative risk, 0.57; 95% confidence interval: 0.38, 0.86), compared with those with less than 10 years of mammographic interpretation.

Discussion

Physicians worldwide are being encouraged to disclose unanticipated outcomes to patients (1). Research suggests that physicians endorse the general concept of disclosure but are unsure how to turn this principle to practice and worry about litigation (23,28). Our study of a large sample of community radiologists in seven states explores radiologists’ attitudes about disclosing harmful errors in mammography to the patient. We found relatively few radiologists would disclose a hypothetical mammography error that led to a delayed diagnosis of cancer. Surprisingly, radiologists’ malpractice attitudes and level of clinical experience were not consistently associated with their reported willingness to disclose or the information they would disclose, suggesting other factors may be more influential in radiologists’ disclosure decisions.

Only 14% of radiologists reported they would “definitely disclose” this hypothetical mammography error to a patient, and 15% would tell the patient explicitly that an error had occurred during the interpretation of prior films. Prior research has suggested that physicians from other specialties may also hesitate to discuss errors with patients (9–12,23,33). This low willingness to disclose errors to patients contrasts with national calls for disclosure of the “facts regarding the unanticipated outcome, including its preventability” (34).

Physicians’ reluctance to disclose harmful medical errors may reflect more than simple self-protection. In prior research, physicians expressed concern that in some circumstances disclosure could cause patient distress that outweighed any benefit the information might have to the patient (23). Physicians’ concern about whether disclosure is in the patient's best interests may be especially high in cases of delayed cancer diagnosis. Cancer is treated at the stage in which it is diagnosed, and the effect of any delayed cancer diagnosis is irreversible. Thus, physicians may question whether informing this patient about the error would be helpful.

However, patients report wanting to be told about all harmful errors in their care, and consider disclosure an important part of a trusting relationship with their physicians (23). Many ethicists stress that disclosure not only enhances patients’ decision-making but is also a form of truth telling. Understanding the rationale and positive consequences for disclosure in cases like these may help physicians feel more comfortable when sharing this information with patients. In addition, disclosing errors can educate patients that no one, including their physician, is perfect and that errors happen in all professions, including medicine (35).

Interestingly, radiologists’ willingness to disclose this error and the information they would disclose was not consistently associated with their attitudes or experiences with medical malpractice. While fear of litigation is a frequently cited barrier to disclosure of errors to patients, other studies have found that physicians’ malpractice attitudes, as well as differences in the malpractice climate, do not predict their willingness to disclose errors (28). While some studies (26,36) have suggested that disclosure of errors might actually reduce the chance that patients will sue, the actual effect of disclosure on litigation remains hotly contested. Many states have adopted “apology laws” to encourage disclosure, but the legal protections provided by most of these laws are minimal (21,37). Definitive research clarifying the relationship between disclosure and litigation would allow disclosure guidelines to be more firmly evidence based.

One barrier to disclosure is physicians’ lack of confidence in their communication skills (23). Increasingly, radiologists are interacting directly with patients. Most (76%) respondents reported they often or always talk with patients about positive diagnostic mammographic results, but positive diagnostic mammographic results are still uncommon events. However, those physicians who communicated more frequently with patients about their diagnostic mammograms were not more likely to disclose this hypothetical error. This suggests physicians’ comfort levels in communicating with patients in general may not lead directly to comfort with disclosure, highlighting the importance of communication skills training for radiologists regarding disclosure.

Radiologists who reported 10–19 years of experience interpreting mammograms were less likely to explicitly disclose this hypothetical error to the patient than were radiologists with less and with more interpretive experience. Younger physicians may be more likely to have undergone formal disclosure training. The greater comfort of senior radiologists with disclosure may reflect their accumulated personal experience with disclosures. In other work, most physicians who reported actually disclosing medical errors to patients were satisfied with how the disclosure had gone, and these positive prior disclosure experiences were associated with a higher willingness to disclose future errors (9). Thus, senior radiologists may want to consider sharing their prior disclosure experiences with their more junior colleagues.

Limitations of our study included the use of a single, hypothetical vignette to measure respondents’ disclosure attitudes, which cannot capture all of radiologists’ disclosure attitudes. Also, radiologists might respond differently if faced with this dilemma in real life. However, physicians’ responses to clinical vignettes have been shown to correlate with actual behaviors (38).

Other potential weaknesses related to determining what constitutes “error” and whether an error caused harm. While the vignette asks radiologists to assume that this error delayed a cancer diagnosis, some radiologists may have been unwilling to make this assumption without having images to review, or may have been unsure whether the increasing calcifications on the previous film warranted a biopsy. Our prior work with physicians in different specialties by using a variety of error vignettes revealed a similar range in physicians’ willingness to disclose errors, suggesting that our results reflect radiologists’ disclosure attitudes rather than uncertainty about clinical nuances of the case (9,28,29,39,40).

In conclusion, the movement toward greater openness with patients following errors is gaining momentum, yet effective disclosure remains the exception, not the rule. Closing the gap between patients’ expectations that harmful errors will be disclosed to them and current practice requires understanding the unique challenges that each specialty, such as radiology, faces related to disclosure, and using this information to help physicians communicate with patients more effectively following errors.

Advance in Knowledge.

Many radiologists report reluctance to disclose a hypothetical mammography error to a patient that would have delayed a cancer diagnosis; radiologists’ malpractice attitudes and experiences were not associated with their approach to disclosure.

Implications for Patient Care.

This research may help guide more appropriate discussions between radiologists and their patients in situations where errors have occurred.

Improved understanding of physician's attitudes toward disclosure has the potential to improve physician-patient relationships in breast imaging with implications across other subspecialties in radiology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carolyn Prouty, DVM, and Odawni Palmer, BA, for assistance with manuscript preparation, and the BCSC investigators, participating mammography facilities, and radiologists for the data they have provided for this study (http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/).

Received December 29, 2008; revision requested January 27, 2009; revision received April 6; accepted April 30; final version accepted May 14.

Supported by an American Cancer Society AIM grant (SIRSG-07-271-01, SIRSG-07-272-01, SIRSG-07 273-01, SIRSG-07-274-01, SIRSG-07-275-01, SIRGS-06-281-01, ACS A1-07-362). T.H.G. supported by grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Investigator Award in Health Policy Research Program and the Greenwall Faculty Scholars in Bioethics Program.

See also the editorial by Berlin in this issue.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 HS-010591) from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, and National Cancer Institute grants R01 CA-107623 and K05 CA-104699 (J.G.E). Data collection for this work was supported by a National Cancer Institute–funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium cooperative agreement (U01CA63740, U01CA86076, U01CA86082, U01CA63736, U01CA70013, U01CA69976, U01CA63731, U01CA70040).

Authors stated no financial relationship to disclose.

Abbreviation:

- BCSC

- Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium

References

- 1.Gallagher TH, Studdert D, Levinson W. Disclosing harmful medical errors to patients. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2713–2719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo B. Resolving ethical dilemmas: a guide for clinicians. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Society for Health Care Risk Management Disclosure: what works now and what can work even better. Chicago, Ill: American Society for Health Care Risk Management, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs Code of medical ethics, annotated current opinions 2004–2005. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Joint Commission Hospital accreditation standards, 2007. Oakbrook Terrace, Ill: Joint Commission Resources, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Brodie M, et al. Views of practicing physicians and the public on medical errors. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1933–1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Brennan TA. Medical malpractice. N Engl J Med 2004;350:283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Kaiser Family Foundation/Agency for Health care Research & Quality/Harvard School of Public Health. National survey on consumers’ experiences with patient safety and quality information. [Accessed March 16, 2009]. http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/National-Survey-on-Consumers-Experiences-With-Patient-Safety-and-Quality-Information-Survey-Summary-and-Chartpack.pdf.

- 9.Gallagher TH, Garbutt JM, Waterman AD, et al. Choosing your words carefully: how physicians would disclose harmful medical errors to patients. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1585–1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobgood C, Xie J, Weiner B, Hooker J. Error identification, disclosure, and reporting: practice patterns of three emergency medicine provider types. Acad Emerg Med 2004;11:196–199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Wu BJ, Forman-Hoffman VL, Levi BH, Rosenthal GE. Disclosing medical errors to patients: attitudes and practices of physicians and trainees. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:988–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu AW, Folkman S, McPhee SJ, Lo B. Do house officers learn from their mistakes? JAMA 1991;265:2089–2094 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berlin L. Breast cancer, mammography, and malpractice litigation: the controversies continue. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;180:1229–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopans DB. Mammography screening is saving thousands of lives, but will it survive medical malpractice? Radiology 2004;230:20–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda DM, Birdwell RL, O'Shaughnessy KF, Brenner RJ, Sickles EA. Analysis of 172 subtle findings on prior normal mammograms in women with breast cancer detected at follow-up screening. Radiology 2003;226:494–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barton MB, Morley DS, Moore S, et al. Decreasing women's anxieties after abnormal mammograms: a controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:529–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Physician Insurers Association of America Breast cancer study 3rd ed.Washington, DC: Physician Insurers Association of America, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elmore JG, Carney PA. Does practice make perfect when interpreting mammography? J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:321–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berlin L. The Trojan horse once destroyed a nation, could it destroy the specialty of radiology? Radiology 2008;248:8–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Orsi C, Tu SP, Nakano C, et al. Current realities of delivering mammography services in the community: do challenges with staffing and scheduling exist? Radiology 2005;235:391–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker S, Lauro C, Sintim-Damoa A. Malpractice allegations and apology laws: benefits and risks for radiologists. J Am Coll Radiol 2008;5:1186–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasson JP, Zand T, Lown BA. Communication in the diagnostic mammography suite: implications for practice and training. Acad Radiol 2008;15:417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA 2003;289:1001–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazor KM, Simon SR, Yood RA, et al. Health plan members’ views about disclosure of medical errors. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:409–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berlin L. Will saying “I'm sorry” prevent a malpractice lawsuit? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187:10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kachalia A, Shojania KG, Hofer TP, Piotrowski M, Saint S. Does full disclosure of medical errors affect malpractice liability? the jury is still out. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2003;29:503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carney PA, Geller BM, Moffett H, et al. Current medicolegal and confidentiality issues in large, multicenter research programs. Am J Epidemiol 2000;152:371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Garbutt JM, et al. US and Canadian physicians’ attitudes and experiences regarding disclosing errors to patients. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1605–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garbutt J, Brownstein DR, Klein EJ, et al. Reporting and disclosing medical errors: pediatricians’ attitudes and behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American College of Radiology Breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) Reston, Va: American College of Radiology, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robbins AS, Chao SY, Fonseca VP. What's the relative risk? a method to directly estimate risk ratios in cohort studies of common outcomes. Ann Epidemiol 2002;12:452–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dick JF, 3rd, Gallagher TH, Brenner RJ, et al. Predictors of radiologists’ perceived risk of malpractice lawsuits in breast imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;192:327–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loren DJ, Klein EJ, Garbutt J, et al. Medical error disclosure among pediatricians: choosing carefully what we might say to parents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:922–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallagher TH, Denham C, Leape L, Amori G, Levinson W. Disclosing unanticipated outcomes to patients: the art and the practice. J Patient Saf 2007;3:158–165 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berlin L. Malpractice and breast cancer: perceptions versus reality. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;192:334–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, Brennan TA, Wang YC. Disclosure of medical injury to patients: an improbable risk management strategy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonnell WM, Guenther E. Narrative review: do state laws make it easier to say “I'm sorry?”. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:811–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA 2000;283:1715–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan DK, Gallagher TH, Reznick R, Levinson W. How surgeons disclose medical errors to patients: a study using standardized patients. Surgery 2005;138:851–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White AA, Gallagher TH, Krauss MJ, et al. The attitudes and experiences of trainees regarding disclosing medical errors to patients. Acad Med 2008;83:250–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]