Abstract

Objective

To design, develop, and evaluate an evidence-based decision aid (DA) for patients with an asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) to inform them about the pros and cons of their treatment options (ie, surgery or watchful observation) and to help them make a shared decision.

Methods

A multidisciplinary team defined criteria for the desired DA as to design, medical content and functionality, particularly for elderly users. Development was according to the international standard (IPDAS). Fifteen patients with an AAA, who were either treated or not yet treated, evaluated the tool.

Results

A DA was developed to offer information about the disease, the risks and benefits of surgical treatment and watchful observation, and the individual possibilities and threats based on the patient’s aneurysm diameter and risk profile. The DA was improved and judged favorably by physicians and patients.

Conclusion

This evidence-based DA for AAA patients, developed according to IPDAS criteria, is likely to be a simple, user-friendly tool to offer patients evidence-based information about the pros and cons of treatment options for AAA, to improve patients’ understanding of the disease and treatment options, and may support decision making based on individual values.

Keywords: decision support techniques, research design, program development, abdominal aortic aneurysm, decision making

Introduction

A decision aid (DA) is a tool to outline treatment options, to explore patient preferences and values, and to help patients in shared decision making. Such DAs have been developed over the years for a wide range of (mainly malignant) conditions as an adjunct to physicians’ counseling. Its ultimate goal is to facilitate shared decision making and to increase quality of patient care (Molenaar et al 2001; Ruland 2004; Whelan et al 2004; Holmes-Rover et al 2005). DAs comprise visual, graphic, or video-assisted illustrations of the risks and benefits involved. DAs were found to perform better in terms of decreasing decisional conflict related to feeling informed, increasing knowledge and realistic expectations, increasing active participation in preference-sensitive decision making, and reducing the proportion of patients who remained undecided post intervention (O’Connor et al 2003; Timmermans et al 2004).

An aneurysm of the abdominal aorta (AAA) is a local dilatation of the main abdominal artery which can be relatively small or huge. Approximately 75% of these AAAs are asymptomatic and are found coincidentally during physical examination or by ultrasonography or CT scanning (Lin and Lumsden 2003). The prevalence is estimated to range between 1.7% and 6% in the elderly, primarily male, population (Drury et al 2005). Patients with an AAA may never suffer from it, yet only 20% of them will survive an unexpected rupture of their aneurysm.

Surgery of an AAA should prevent rupture of the aneurysm, but may also induce complications and premature death due to the very procedure. Key issues in decision-making are the size of the aneurysm, which is related to risk of aneurysm rupture, and the risk of surgical complications as a result of advanced age or serious (cardiovascular) comorbidity (Lovegrove et al 2008). Hence, patients with small aneurysms (<5.5 cm in diameter) are considered not to require surgery, but are usually managed by means of watchful observation with regular ultrasonography (UKSAT 2002). For larger aneurysms, surgery is commonly advised and applied if the risk of complications is considered acceptable.

As the disorder per se does not necessarily lead to disease, the treating vascular surgeon and the patient face the dilemma of weighing the risk of rupture of the AAA during watchful observation against the risk of complications of surgery. As there is no single preferred treatment for these patients, their treatment preference plays a crucial role in the final decision to arrive at ‘shared decision-making’ (Charles et al 1999). Whenever such preference-sensitive decisions are to be made, decision-supportive interventions appear to be useful to help patients make an informed choice and to standardize the information given.

The aim of this project was to design and develop a DA for patients with an asymptomatic AAA to supply patients with information as to the pros and cons of the various treatment options, presented in a structured and easily accessible manner, eventually to facilitate well-informed and satisfactory decision making.

Methods

The DA was designed at the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Because this study focused on the development of a DA, and no intervention was performed that might influence the treatment of patients with an AAA, approval of the Hospital Ethics Advisory Board was waived. No commercial sponsoring was obtained.

The development of the DA was planned in five stages: 1) composing a multidisciplinary development and advisory team, 2) defining the requirements of the desired DA, 3) obtaining the available evidence on the natural history, treatment, and complications of AAA, 4) designing and creating the DA, and finally 5) testing, adjusting, and evaluating the DA.

Stage 1: Multidisciplinary development team

A multidisciplinary team was assembled, consisting of physicians, vascular surgeons, clinical psychologists, patient education and computer experts, and former and actual AAA patients, who contributed to the development and pilot-evaluation of the DA.

Stage 2: Content and functional requirements

The development was commenced by formulating minimal requirements (by DTU, AG, SM). The desired DA should match the following criteria:

It should be simple to use, read, and understand by elderly patients

It should be readily available in a format usable both at home and the (outpatient) clinic

It should contain essential information about the disorder itself.

It should explain the surgical (open and endovascular) and watchful waiting treatment options, their possible benefits and disadvantages, and address the known as well as unknown aspects as to the prognosis after the different treatment options.

It should inform patients about their risk level and its consequences, ie, mortality and (major) morbidity in relation to the anticipated (non) surgical procedure.

This information should be presented in an interactive mode to guide the patient primarily along the information and options relevant to his or her particular condition and risk level.

Its content should be in accordance with legal standards and in agreement with the quality criteria for patient decision support technologies as developed by the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration (IPDAS) (Elwyn et al 2006).

It should provide (references to) the best available, up-to-date evidence from the medical literature to underpin the information given about all treatment options.

Stage 3: Included evidence

Data on rupture risk and beneficial or harmful treatment effects were based on evidence from the literature searched from major medical databases (by AMK), such as PubMed and the Cochrane Library up to March 1, 2008. Accuracy of data extraction was checked by our group of vascular surgeons. From these data, overall estimates of survival, risks, and complications for the various treatment options were derived to be incorporated in the DA (Greenhalgh et al 2004; UKSAT 1998; DREAM 2005; Baas et al 2008).

The indication for and prognosis after the various treatment options is known to be influenced by the comorbidity of the patient (Hirsch et al 2006). A history of renal insufficiency and vascular comorbidity increases the risk of postoperative complications in AAA patients. To quantify this risk, the Glasgow Aneurysm Score (GAS) has been developed, which is a risk score calculated from the patient’s age, kidney function, and history of cerebrovascular disease (Biancari et al 2003, 2008). This GAS is now a commonly used and validated prediction rule to help surgeons in decision making in AAA patients (Hirzalla et al 2006).

Stage 4: Format, design, and creation of the DA

Considering the high age and possible ignorance regarding the use of computers of the DA’s target patients, we contemplated whether the optimum DA should be in a written or digital form. We initially aimed at producing a DA that would provide information tailored to the patient’s condition and that would also allow us to record the parts of information that would be accessed and appreciated most by the patients. We therefore opted for a digital format for the DA, in which these data could be automatically recorded into log files. Moreover, several graphical images could be included to depict the risks and benefits involved in the different treatment options. Although it has been shown that graphical presentation of numerical data helps understanding such risks (Stiggelbout et al 1997), a wide range of graphical presentation forms is available, but it is still unclear which one is most effective to convey the information and which of these patients prefer most.

The choice for a digital DA entailed designing a user-friendly, mouse-driven application, in which the patient would be guided through simple clicks along a preferential information route tailored to the patient’s clinical situation. This situation would be determined by the patient’s GAS and aneurysm diameter, to be entered at the beginning of the DA. If desired, however, the patient should be able to access the information regarding any of the other treatment options.

Stage 5: DA testing and evaluation

The pilot version of the DA was tested by four vascular surgeons, mainly for its medical content, and by four elderly subjects, for its usefulness and user-friendliness.

Based on their suggestions, the pilot version of the DA was improved and presented to a group of 15 former and actual AAA patients to evaluate comprehensibility and user-friendliness more formally. These patients were invited via the Dutch Society of Vascular Patients. A patient sample was composed varying in age, gender, computer proficiency, education level, place of residence, and previous AAA treatment. They received the DA via email or were visited personally by the investigator (AMK), and were asked to fill in a short questionnaire about the DA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient questionnaire about their appreciation of the decision aid. The first three questions are based on visual analogue scales

| 1. How much time did you spend examining the decision aid? | |

| … hrs … mins | |

| 2. Did you find the decision aid user friendly? | |

| ____________________ | |

| User friendly | Not user friendly |

| 3. Did you find the information in the decision aid understandable? | |

| ____________________ | |

| Understandable | Not understandable |

| 4. Would you have felt better informed if you had seen this decision aid before a decision about your treatment was made? | |

| ____________________ | |

| Yes | No |

| 5. When choosing which information you want to see, do you prefer a digital decision aid over a paper-based one? | |

| ____________________ | |

| Yes | No |

| 6. Do you think the decision aid can help patients (who visit their surgeon for the first time for their aneurysm) choose between the treatment options? | |

| □Yes | |

| □No | |

| 7. Did you the find the figures about surgical risks frightening or clarifying? | |

| □Frightening | |

| □Clarifying | |

Results

Starting April 2007, the pilot version was designed as a Powerpoint presentation (Microsoft Office 2003; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). This comprised a total of 170 pages (‘slides’) and offers general information as to the disorder, the possible treatment options, and the opportunity to balance the risks involved.

Users can thumb through the DA and choose information tailored to their individual physical condition. For this purpose, action buttons on ‘crossroads’ pages enable to skip the next pages on topics the users consider less relevant. In addition, the user can be directed to information pertinent to the patient by choosing their aneurysm diameter (less than or above 5.5 cm), possible treatment options (open or endovascular aneurysm repair or watchful observation) as suggested by their surgeon or the patient’s personal GAS score. To prevent from ‘getting lost’ in the program, a ‘breadcrumb trail’ was added to indicate the progress of, and position in, the program. To further comply with the IPDAS criteria, we added the following items: date of last update, a statement the developers of the DA would not benefit from whichever choice the patient would make based on the DA, and references to the (level of) evidence for the various bits of information given in the DA. In addition we elaborated the section in which patients can consider their own situation as to treatment options, risks and anxiety. The final pilot version of the DA, developed during a period of three months, complied with 33 out of 40 IPDAS criteria.

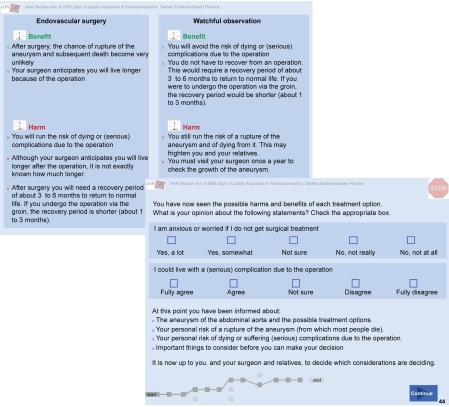

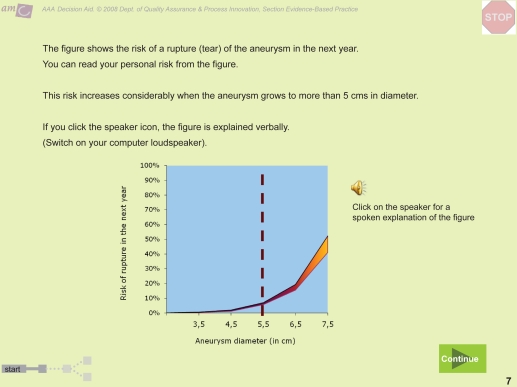

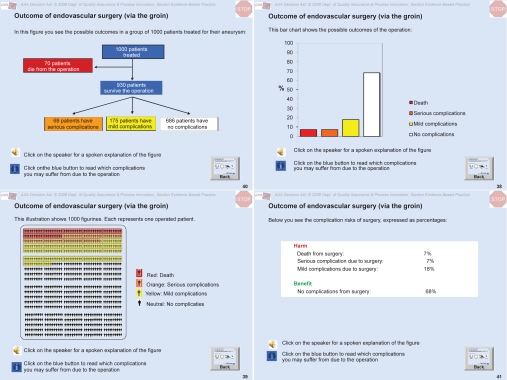

Some of the pages in the DA are presented in Figures 1–4. They illustrate the information supplied on the disease itself (Figure 1), the risk of rupture presented as a Figure (the user can choose to get verbal explanations as well; Figure 2), the various graphical representations of the benefits and risks of the endovascular therapy (Figure 3), and a summarizing comparison of the pros and cons of surgery versus watchful waiting, including an interactive part where patients can fill in their personal anxiety or reluctance regarding a certain treatment option (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Sample page from the decision aid illustrating the pathologic anatomy of the abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Figure 4.

Sample page from the decision aid concerning the comparison of surgery versus watchful observation and assessment of the patients’ individual opinion about their anxiety and considerations.

Figure 2.

Sample page in the decision aid depicting the risk of rupture in relation to the aneurysm diameter. Additional spoken information is provided by clicking the speaker button.

Figure 3.

Various graphical presentations provided of the probabilities of benefit and harm involved in surgical AAA treatment to suit patient preferences, in clockwise order: natural frequency trees, bars, percentages, and visual aids.

Fifteen patients evaluated the pilot version of the DA. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. They examined the DA for a mean of 80 minutes (range 20–300 min.). On a scale from zero to 100, ‘user-friendliness’ scored a median of 75 (interquartile range [IQR] 53–86), ’understandability’ 86 (IQR 80–90), and ‘feeling better informed’ 68 (IQR 50–90). The vast majority of patients stated the DA offered additional value in their decision making, and all but one patient found the figures on possible risks clarifying rather than frightening. Every type of graphical representation was valued most by at least some of the patients. No clear differences were observed between patients who had and those who had not yet undergone surgical treatment for their AAA.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 15 patients who tested the pilot version of the decision aid

| Male gender | 12 out of 15 (80%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean; range) | 71 (62–78 yrs) |

| AAA since (years; range) | 6 (2–13 yrs) |

| AAA diameter (cm; range) | 4.8 (3.3–7.5 cm) |

| Operated? (open or endovascular) | 40% (Half of them open surgery) |

| Computer (+ internet) user | 73% |

Abbreviation: AAA, abdominal aorta aneurysm.

Finally, a linguistic check was performed (SM) to ensure the use of plain language and easy interpretation of the DA. The program, now available on CDROM, was also equipped with the possibility to print concise information in the form of a brochure the patient can take home. The DA has been registered in the Cochrane Decision Aid Library Inventory (DALI) of the Ottawa Health Decision Centre (see https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/DALI).

Discussion

In this paper the development of the first DA regarding treatment options for patients with an asymptomatic AAA is described. This computer-based DA is evidence-based, is developed according to the IPDAS criteria, and is approved by the Dutch Society of Vascular Patients.

The development of this DA was similar to those in other medical realms, eg, cancer of the breast, prostate, or lungs (Molenaar et al 2001; Feldman-Stewart and Brundage 2004; Holmes-Rovner 2005; Chiew et al 2007), in which patients may be overwhelmed by a potentially life-threatening diagnosis and at the same time are invited to participate in treatment decision making. On the other hand, this DA differs in that it focuses on an asymptomatic disorder that will remain without consequences until either rupture or surgical treatment occurs. In addition, this DA may offer surgeons a tool to share necessary information in an evidence-based, standardized format.

In only one RCT the benefits of a comprehensive, highly individualized, evidence-based brochure for asymptomatic AAA patients based on information by way of Markov analysis have been studied. The highly individualized information was found to be dissatisfying and impractical (Molewijk 2006). Therefore, the information offered in this DA was mainly on headlines rather than focusing only on the individual situation of each patient (Feldman-Stewart and Brundage 2004). However, as risk of rupture strongly correlates to the size of the aneurysm, and surgical risk considerably increases with the presence of comorbidity, it was thought to be necessary to tailor information in the DA to these two factors in order for the DA to be a useful adjuvant in the communication between patient and surgeon. In addition, the IPDAS criteria also describe “the possibility to view probabilities based on the patient’s own situation” as one of the quality criteria.

This DA was made in accordance with the vast majority of IPDAS criteria. Although these criteria are not yet commonly applied, they should improve the value of DAs to let patients better understand their own condition, to reduce decisional conflict, and to help them make an informed choice (O’Connor et al 2007). The debate is ongoing about the value of DAs to improve clinical decision making (Holmes-Rovner et al 2007). DAs did not appear to outperform comparative strategies in affecting patient satisfaction with decision making, anxiety, and health outcomes (O’Connor et al 2003). Furthermore, DAs can only be developed if evidence is available in sufficient amounts to underpin the information supplied for the various treatment alternatives.

The initial version of this decision support had limitations as to the complexity of the individual risk information, which was dissatisfying for the patient. After adjustments, appraisal by AAA patients showed that this DA was considered user-friendly, of additional value, and improved understanding. As intended, the DA was found to be not simply an informative ‘digital brochure’ containing basic information about treatment options, but rather seemed to be a possibly useful tool to actually help patients decide upon their optimum treatment choice.

We actually do not yet know whether the DA really offers more (useful) information than what the vascular surgeons already explain to the patient and whether it is also capable of increasing patients’ knowledge and subsequently reducing patients’ decisional conflict regarding their treatment choice. Ultimately, it might also improve satisfaction, quality of life, and prevent a relevant increase in anxiety of asymptomatic AAA patients. Moreover, it might possibly affect the number of AAA interventions eventually performed. This is being studied in an ongoing trial on the usefulness of this DA in a randomized setting.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the departments of Vascular Surgery, Medical Informatics, and Medical Psychology, as well as the Dutch Society of Vascular Patients for their substantial contribution to the development and evaluation of this DA. We declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Baas AF, Janssen KJ, Prinssen M, et al. The Glasgow Aneurysm Score as a tool to predict 30-day and 2-year mortality in the patients from the Dutch Randomized Endovascular Aneurysm Management trial. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:277–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancari F, Hobo R, Juvonen T. Glasgow Aneurysm Score predicts survival after endovascular stenting of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients from the EUROSTAR registry. Br J Surg. 2006;93:191–4. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancari F, Leo E, Ylönen K, et al. Value of the Glasgow Aneurysm Score in predicting the immediate and long-term outcome after elective open repair of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. 2993;90:838–44. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankensteijn JD, de Jong SE, Prinssen M, et al. Two-year outcomes after conventional or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2398–405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–61. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiew KS, Shepherd H, Vardy J, et al. Development and evaluation of a decision aid for patients considering first-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Health Expect. 2007;11:35–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury D, Michaels L, Jones L, et al. Systematic review of recent evidence for the safety and efficacy of elective endovascular repair in the management of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. 2005;92:937–46. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh RM, Brown LC, Kwong GP, et al. EVAR trial participants. Comparison of endovascular aneurysm repair with open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1), 30-day operative mortality results: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:843–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16979-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic) Circulation. 2006;113:e463–654. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirzalla O, Emous M, Ubbink DT, et al. External validation of the Glasgow Aneurysm Score to predict outcome in elective open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 44:712–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes-Rovner M, Nelson WL, Pignone M, et al. Are patient decision aids the best way to improve clinical decision making? Report of the IPDAS Symposium. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:599–608. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07307272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes-Rovner M, Stableford S, Fagerlin A, et al. Evidence-based patient choice: a prostate cancer decision aid in plain language. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2005;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PH, Lumsden AB. Images in clinical medicine. Abdominal aortic aneurysm as an incidental finding. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1445–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm020634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovegrove RE, Javid M, Magee TR, et al. A meta-analysis of 21,178 patients undergoing open or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. 2008;95:677–84. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar S, Sprangers MA, Rutgers EJ, et al. Decision support for patients with early-stage breast cancer: effects of an interactive breast cancer CDROM on treatment decision, satisfaction, and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1676–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molewijk AC. Thesis. University of Leiden; 2006. Risky Business: individualized evidence-based decision support and the ideal of patient autonomy. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor AM, Bennett C, Stacey D, et al. Do patient decision aids meet effectiveness criteria of the international patient decision aid standards collaboration? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:554–74. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07307319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruland M. Improving patient safety through informatics tools for shared decision making and risk communication. Int J Med Inform. 73(7–8):551–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiggelbout AM, Kiebert GM. A role for the sick role. Patient preferences regarding information and participation in clinical decision making. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;157:383–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans D, Molewijk B, Stiggelbout A, et al. Different formats for communicating surgical risks to patients and the effect on choice of treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;54:255–63. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [UKSAT] United Kingdom Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Mortality results for randomised controlled trial of early elective surgery or ultrasonographic surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Lancet. 1998;352:1649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [UKSAT] United Kingdom Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Long-term outcomes of immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1445–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, et al. Effect of a decision aid on knowledge and treatment decision making for breast cancer surgery. JAMA. 2004;292:435–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]