Abstract

The wound repair process is a highly ordered sequence of events that encompasses haemostasis, inflammatory cell infiltration, tissue regrowth and remodelling. Wound healing follows tissue destruction so we hypothesized that antibodies might bind to wounded tissues, which would facilitate the engulfment of damaged tissues by macrophages. Here, we show that B cells, which produce antibodies to damaged tissues, are engaged in the process of wound healing. Splenectomy delayed wound healing, and transfer of spleen cells into splenectomized mice recovered the delay in wound healing. Furthermore, wound healing in splenectomized nude mice was also delayed. Transfer of enriched B220+ cells by magnetic beads accelerated wound healing in splenectomized mice. We detected immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) binding to wounded tissues by using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled anti-IgG1 6–24 hr after wounding. Splenectomy reduced the amount of IgG1 binding to wounded tissues. Immunoblotting studies revealed several bands, which were reduced by splenectomy. Using immunoprecipitation with anti-IgG bound to protein G we found that the intensity of several bands was lower in the serum from splenectomized mice than in that from sham-operated mice. These bands were matched to myosin IIA, carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, argininosuccinate synthase, actin and α-actinin-4 by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry analysis.

Keywords: wound healing, autoantibodies, rodent, B cells, skin

Introduction

The wound repair process is a highly ordered sequence of events that encompasses haemostasis, inflammatory cell infiltration, and tissue regrowth and remodelling. First, platelets generate a clot, which stops the bleeding, and serves as a temporary barrier and a source of chemotactic factors. Subsequently, attracted leucocytes initiate an inflammatory response before fibroblasts and endothelial cells migrate to the wound to generate tissue that contracts the wound margins. Finally, epithelial cells complete the repair process by covering the denuded wound surface.1

The function of granulocytes and macrophages in wound healing has been extensively studied. These cells produce cytokines, chemokines, matrix proteins, matrix metalloproteinases and growth factors.2–8 In contrast, there are few reports that describe the effects of T or B cells in wound healing except γδ T cells.9,10 In aseptic wound healing, very few T or B cells migrate to the wound site. However, immunoglobulin secreted by B cells can reach wound sites. In the case of bacterial infections, immunoglobulin specific for the bacteria bind to the surface and induce bacterial killing by phagocytosis mediated by Fc receptors. In addition to antibodies specific for micro-organisms, antibodies to tissue antigens also reach wound sites. However, until now it has not been studied whether antibodies to damaged tissues work to repair wounds. To explore the role of acquired immunity in wound repair, we splenectomized experimentally wounded mice. Interestingly, splenectomy greatly delayed wound healing. Transfer of B cells into splenectomized mice restored the wound repair ability. Further studies indicated the importance of immunoglobulin specific for injured dermal tissues.

Materials and methods

Mice and splenectomy

Two-month-old C57BL/6 (C57BL/6J) female mice and KSN nude mice were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc., Hamamatsu, Japan. Green mice [C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-EGFP) C14-Y01-FM131Osb] were kindly supplied from Riken (Tsukuba, Japan) with the permission of Dr Okabe.11 These mice were maintained in the Animal Research Facility at the Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine under specific pathogen-free conditions and used according to institutional guidelines. Anaesthetized mice were subjected to either a sham operation or splenectomy.

Punch biopsy wounding and macroscopic examination

After shaving and extensive cleaning with 70% ethanol, the dorsal skin was picked up at the midline and two layers of skin were punched through with a sterile disposable biopsy punch (diameter 3 mm; Kai Industries, Tokyo, Japan). This is an aseptic wound model, which is completely different from pressure ulcers. This procedure generated two excision full-thickness wounds with one on each side of the midline. The same procedure was repeated four times, generating eight wounds on each animal. Each wound site was digitally photographed at the indicated time intervals, and wound areas were determined on photographs using photoshop (version 7·0; Adobe Systems) and calculated using the ‘area calculated’ software on Excel. Changes in the area of wound sites are expressed as the proportion of the initial wound areas. In some experiments, wounds and their surrounding areas (including the scab and epithelial margins) were cut for further analyses with a sterile disposable biopsy punch with a diameter of 6 mm (Kai Industries) at the indicated time-points.

Histopathological analyses of wound sites

Wound specimens were fixed in 2% formaldehyde buffered with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7·2), and then embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetechnical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Frozen 5-mm sections were stained. The sections were further processed for immunohistochemical analyses to the antigen at the wound area. Fixed slides were treated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled anti-mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), FITC-labelled anti-mouse CD4 and phycoerythrin-labelled anti-mouse B220 (BD).

Western blotting

Tissues were homogenized in buffer [50 mm Tris–HCl pH 6·8, 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 2 mm sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)], and then lysed in sample buffer (50 mm Tris–HCl pH 6·8, 2% SDS, 2·5% glycerol, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and 0·05% bromophenol blue). One milligram per millilitre of total protein was resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Tokyo, Japan). Blotted membranes were reacted with 1/100 diluted serum. Bound antibodies were detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence system12 (GE Healthcare UK Ltd., Buckinghamshire, UK).

Isolation of B cells

Isolation of highly pure B cells from spleen is achieved by depletion of magnetically labelled cells. Contaminating non-B cells, i.e. T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, granulocytes and erythroid cells were depleted by the suspension of spleen cells with the B Cell Isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Tokyo, Japan) using a cocktail of biotin-conjugated antibodies against CD43 (Ly-48), CD4 (L3T4) and Ter-119, and Anti-Biotin MicroBeads. The magnetically labelled non-B cells were depleted by retaining them on a MACS® Column (LS column) in the magnetic field of a MACS Separator, while the unlabelled B cells pass through the column.

Phagocytosis by macrophages

Peritoneal macrophages were collected from groups of three mice 3 days after injection of 1 ml of 3% thioglycollate medium and were isolated by adherence of the cells to tissue plates overnight at 37° in 5% CO2. Peritoneal neutrophils of Green mice were collected as described previously by injecting 0·5 mg Zymosan intraperitoneally.13 They were damaged by heat treatment at 100° for 10 seconds. Macrophages (5 × 105) and target damaged neutrophils were plated at a ratio of one macrophage to one target cell. The mixture was incubated at 37° in 5% CO2 for 1 hr and washed with PBS to remove unincorporated target cells. They were detached by trypsin/EDTA. Cells were assessed on a flow cytometer (FACS Calibur, BD, Tokyo, Japan), and analysed using flowjo software (Tomy Digital Biology, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunoprecipitation

For typical preparations, 50 μl mouse serum was added to 100 μl protein G beads (GE Healthcare UK Ltd) in RIPA buffer (25 mm Tris–HCl pH 8·0, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mm EDTA, 5 mm MgCl2, 0·3% nonidet-P40, 1 mm phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride). After 1 hr incubation with rotation at room temperature, unbound serum was washed out using 1 ml 0·15 m sodium borate twice. Twenty millimoles dimethylphosphate (DMP) was added to serum-bound protein G beads. After 30 min of rotation at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 400 g at 4°. Supernatant was discarded and 500 μl of 0·2 m ethanolamine was added. It was rotated for 2 hr at room temperature and washed once with centrifugation. The precipitate was added to 100 μl PBS with 0·05% azide. The tissue sample was taken and homogenized using a Potter homogenizer in RIPA buffer. Non-specific binding of serum to protein G was obtained by the following procedure. Two hundred millilitres of sample was mixed with 50 μl protein G beads in RIPA buffer. After 2 hr incubation with rotation at room temperature for 2 hr, the supernatant was taken by centrifugation. The 200 μl of sample (supernatant) was mixed with 50 μl of protein G beads, which gives bound serum. Immunoprecipitation was carried out at 4° for 16 hr, and beads were washed five times in the immunoprecipitation buffer. Beads were then washed with 50 mm Tris–HCl (pH 6·8) at 4°, then treated with sample buffer (62·5 mm Tris–HCl, pH 6·8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and 5% bromophenol blue). A fraction of the elute was monitored by SDS–PAGE and was silver stained.

Identification of proteins

For liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) ion search analysis, protein spots were excised from the gel. The gel pieces were destained and dried by vacuum centrifugation. For carbamidomethyl modification, the dried gel pieces were rehydrated in 100 mm ammonium bicarbonate containing 10 mm dithiothreitol. After removal of the solution, the gel pieces were alkylated and then rehydrated in a trypsin digest solution [Trypsin Gold, Mass Spectrometry Grade (Promega Co., Madison, WI)]. The LC–MS/MS ion search analysis was performed using an LCQ Advantage nanospray ionization ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA) combined with a MAGIC2002™ HPLC System (Michrom BioResources, Inc., Auburn, CA) that was equipped with a MonoCap® column of 0·1-mm diameter and 50-mm length (AMR Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The MS/MS spectrum data collected repeatedly were submitted to the program mascot (Matrix Science Inc., Boston, MA).

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Japan K.K., Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Residual genomic DNA was digested and removed using DNase I (Roche Diagnostics K.K., Tokyo, Japan) treatment. First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) for reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and oligo-dT(12–18) primers. The cDNA was diluted with DNase free water at a concentration of 10 ng/μl. The RT-PCR was performed using the Ex-Taq PCR kit (TAKARA BIO INC., Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following primers were used: β-actin(f) 5′-AGTGTGACGTTGACATCCGT-3′, β-actin(r) 5′-GCAGCTCAGTAACAGTCCGC-3′, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1)(f) 5′-TGAATGTGAAGTT GACCCGT-3′, MCP-1 (r) 5′-AAGGCATCACAGTCCGAGTC-3′, CCL3(f) 5′-CCTC TGTCACCTGCTCAACA-3′, CCL3 (r) 5′-GATGAATTGGCGTGGAATCT-3′, CXCL3(f) 5′-CAACGGTGTCTGGATGTGTC-3′, CXCL3 (r) 5′-AGCCAAGGAATA CTGCCTCA-3′. The result was evaluated on a Lumi Vision Analyzer (AISINSEIKI Co., Ltd, Aichi, Japan).

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparison was performed by analysis of variance followed by Fisher’s post hoc test. Values of P < 0·05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

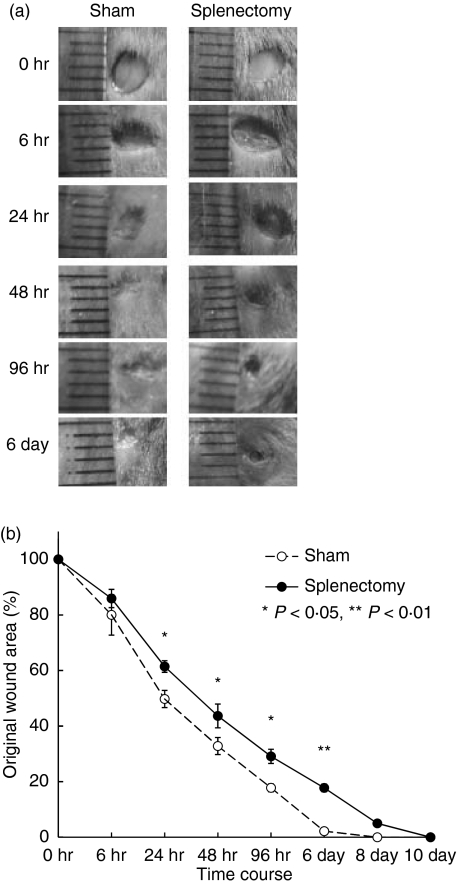

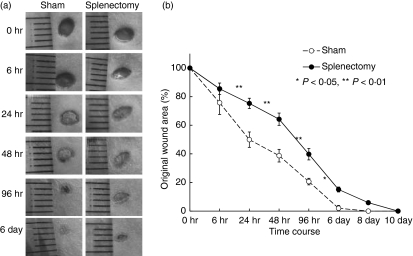

Delayed wound repair in splenectomized mice

Two-month-old C57BL/6 mice were splenectomized or given sham operations. At one week post-operation, we performed punch biopsies on the backs of these mice. The duration of wound healing was extended in splenectomized mice (Fig. 1). No infection occurred and no difference in body weight was observed (data not shown). The numbers of neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes in blood of splenectomized mice were almost identical to those of sham-operated mice (data not shown). To confirm that the spleen is needed for the wound healing process, we injected spleen cells intravenously into the splenectomized mice. Both intravenous injection and direct injection (data not shown) restored normal wound healing kinetics (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Delayed wound healing in splenectomized C57BL/6 mice. Two-month-old C57BL/6 mice were splenectomized or sham-operated. One week later, punch biopsies were performed on the backs of these mice. (a) Macroscopic changes in wound healing in splenectomized mice. (b) Changes in percentages of wound areas at each time-point in comparison to the original wound area in splenectomized (closed circles) or sham-operated mice (open circles). Data shown are the mean ratio ± SEM of five mice (*P < 0·05, **P < 0·01).

Figure 2.

Transfer of spleen cells into splenectomized mice rescued the delay in wound healing. Spleen cells were prepared from 2-month-old C57BL/6 mice. Cells (1 × 107/mouse) were injected into splenectomized C57BL/6 mice intravenously 1 week after splenectomy. Punch biopsies were performed immediately after cell injection. Data shown are the mean ratio ± SEM of four separate experiments (*P < 0·05, **P < 0·01).

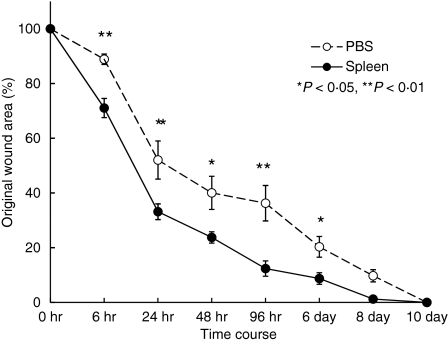

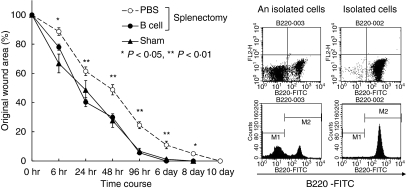

Acceleration of wound healing by splenic B cells

We next performed splenectomies in KSN nude mice. Wound healing in splenectomized nude mice was also delayed (Fig. 3). These results suggest a role for B cells in wound healing. We enriched B cells from spleens using magnetic beads. Intravenous injection of purified B cells restored the kinetics of wound healing to that observed in sham-operated B6 mice (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Delayed wound healing in splenectomized KSN mice. Two-month-old KSN nude mice were splenectomized or sham-operated. One week later, punch biopsies were performed on the backs of these mice. (a) Macroscopic changes in wound healing in splenectomized (closed circles) or sham-operated mice (open circles). (b) Changes in percentages of wound areas at each time point in comparison to the original wound area. Data shown are the mean ratio ± SEM of five mice (*P < 0·05, **P < 0·01).

Figure 4.

Transfer of purified B cells into splenectomized mice rescued the delay in wound healing. One week after splenectomy, punch biopsies were performed on the backs of these mice. B cells were purified by magnetic antibody cell sorting from C57BL/6 spleens (see Materials and methods). Purified B cells (1 × 107/mouse) were injected into C57BL/6 mice intravenously. Punch biopsies were made immediately after cell injection. (a) Changes in percentages of wound areas at each time point in B-cell transfer (closed circles), phosphate-buffered saline transfer (open circles) or sham-operated (closed triangle) mice. Data shown are the mean ratio ± SEM of four separate experiments. (b) Purity of B cells was assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting by staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled B220.

Reduced binding of IgG1 antibodies to the wounded sites in splenectomized mice

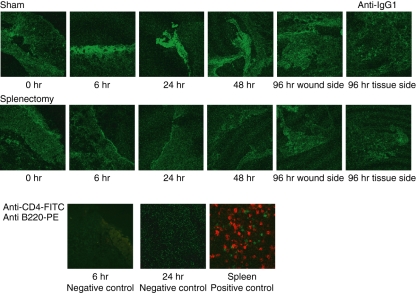

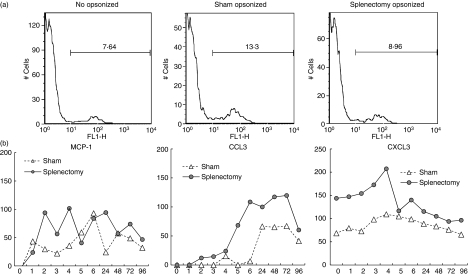

We detected IgG1 binding to wounded tissues using FITC-labelled anti-IgG1. There was clear evidence of IgG1 binding at 6–24 hr. Splenectomy reduced the amount of IgG1 binding to wounded tissues (Fig. 5). One possibility is that these antibodies are secreted from B cells, which might migrate to the wounded site. However, we could not detect either B cells or T cells at wounded tissues at any time (lower part of Fig. 5 shows the results of the absence of CD4 T cells and B220 B cells at 6 and 24 hr). Antibodies to the damaged tissues might facilitate the phagocytosis by opsonization to the damaged tissues. We examined whether antibodies included in serum might up-regulate phagocytosis induced by macrophages. For technical reasons we only used neutrophils as damaged cells in this experiment. We found that the addition of serum to the heat-damaged neutrophils facilitated phagocytosis by macrophages. Serum taken from sham-operated mice induced phagocytosis of damaged neutrophils by macrophages more effectively than serum taken from splenectomized mice (Fig. 6a). In splenectomized mice, the clearance of neutrophils by macrophages was delayed. Macrophages might stay in the wounded site for a long time. We examined the migration of neutrophils and macrophages to the wounded site at each time-point of wound healing by immunohistochemistry and found that in splenectomized mice neutrophils and macrophages stayed for 24 hours longer than those in sham operated mice (data not shown). The delayed existence of neutrophils and macrophages might cause the delayed appearance of myofibroblasts (anti-SMA) and endothelial cells (anti-CD31). We found that both appeared later in splenectomized mice (data not shown). Because we could detect neutrophils and macrophages in wounded tissues, we examined the expression of chemokines and cytokines in the wounded tissues. Several chemokines and cytokines were expressed in wounded tissues (data not shown.). The expression of macrophage chemokines, CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL3 and CXCL3, was higher in splenectomized mice than in sham-operated mice (Fig. 6b).

Figure 5.

The deposition of antibodies to damaged tissues in wound healing. Two-month-old C57BL/6 mice were splenectomized or sham-operated. One week later, 3-mm punch biopsies were performed on the backs of these mice. Tissue samples were obtained by taking 6-mm punch biopsies around 3-mm holes. Frozen samples were analysed with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled antibodies and observed by confocal microscopy. The deposition of antibodies to damaged tissues was analysed by FITC-labelled anti-mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1). Wounded tissues were stained by FITC-labelled anti-mouse CD4 (T cells) and PE-labelled anti-mouse B220 (B cells). Neither T nor B cells were observed, which became negative controls to FITC-labelled anti-mouse IgG1. As a positive control, spleens were stained with anti-mouse CD4 (T cells) and PE-labelled anti-mouse B220 (B cells).

Figure 6.

Function of leucocytes in wounded tissues. (a) Phagocytosis of damaged neutrophils by macrophages. Thioglycollate-induced peritoneal macrophages were collected from the peritoneal cavity of C57BL/6 mice as phagocytes. Zymosan-induced neutrophils were collected from the peritoneal cavity of Green mice. Neutrophils were heat-treated (100° for 10 seconds). They were opsonized (37° for 15 min) using serum from sham-operated or splenectomized mice. Then macrophages and neutrophils were mixed and analysed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Left panel, non-opsonized; middle panel, opsonized by the serum from sham-operated mice; right panel, opsonized by the serum from splenectomized mice. Representative results are shown from three independent experiments. (b) Expression of chemokines and cytokines in wounded tissues. RNAs were extracted from wounded tissues at each time-point. The expression of macrophage chemokines CCL2, CCL3, CXCL3 was analysed by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. Results were shown as relative band intensity. Representative results are shown from three independent experiments.

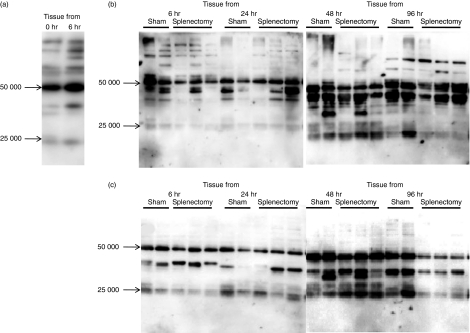

We performed immunoblotting studies to confirm the binding of antibodies to wounded sites. Sera were taken from sham-operated mice before punch biopsy. These bands were increased when target tissues were taken after 6 hr of wound healing (Fig. 7a). When we used target tissues at various times after the punch biopsy, the band pattern was changed. The lower bands were increased at the later times (Fig. 7b). As expected, the number of these bands was reduced by splenectomy at 6 and 24 hr. However, at later times (48 and 96 hr) these bands were not so decreased in the splenectomized mice (Fig. 7c).

Figure 7.

Splenectomy reduced the antibody production to damaged tissue. Wounded tissues were taken from sham-operated or splenectomized 11-week-old C57BL/6 mice at 6–96 hr after punch biopsy. Tissue lysates/homogenates were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Sera (diluted 1 : 100) taken after 1 week from sham-operated or splenectomized mice (10 weeks old) were reacted with membranes as a primary antibody and then membranes were reacted with anti-mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) secondary antibodies. Bound antibodies were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence system. (a) Sera were taken from sham-operated mice. Tissues were taken at 0 hr (before punch biopsy) and 6 hr after punch biopsy. (b) Sera were taken from sham-operated mice. Tissues were taken at 6, 24, 48 or 96 hr after punch biopsy from sham-operated or splenectomized mice, (c) Sera were taken from splenectomized mice. Tissues were taken at 6, 24, 48 or 96 hr after punch biopsy from sham-operated or splenectomized mice.

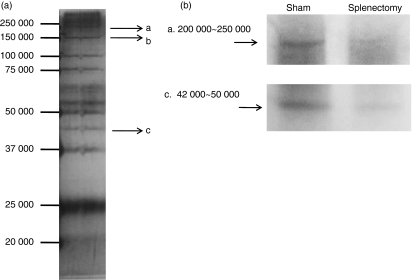

Autoantigen detection by LC–MS/MS

These experiments have shown that IgG1 antibodies bind to damaged tissues, which may facilitate clearance by macrophages. We tried to determine the tissue antigens that were bound to the IgG1 antibodies. First, the sera taken from C57BL/6 mice were covalently bound to protein G beads. We tried to remove non-specific bands to protein G by preliminary incubation of the tissue samples for protein G. The unbound tissue sample was incubated with serum-bound protein G. They were immunoprecipitated and run the SDS–PAGE. There were several bands in the stained membrane (silver staining; Fig. 8a). Each spot was taken and run on the LC–MS/MS. Among them, three spots were successfully determined (a, b, c). Spots a and b correlated with a single protein. Spot a was correlated with myosin, heavy polypeptide 9, (non-muscle isoform; myosin IIA, 226 000 molecular weight (MW). Spot b was correlated with carbamoyl-phosphate synthase (164 000 MW). However, spot c correlated with three proteins. argininosuccinate synthase (46 000 MW). Actin (42 000 MW) and α-actinin-4 (104 000 MW) (Table 1).

Figure 8.

Antigens were detected by antibodies during wound healing. (a) Skin samples of 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice were taken by punch biopsy (6 mm) 6 hr after wounding (3 mm). Control serum and splenectomized serum were bound to beads. Bead-bound sera were mixed with removed tissue. These were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°. Washed materials were run on sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and stained with silver. Each band was cut and analysed using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Arrow (a, b, c) indicates the decided bands. (b) Autoantibodies were bound to damaged tissues during wound healing. The skins of 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice were punch biopsied, Wounded tissues were taken from sham-operated or splenectomized mice. Tissue lysates/homogenates were subjected to SDS–PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Sera (diluted 1 : 100) from sham-operated or splenectomized mice were reacted with membranes as a primary antibody and then membranes were reacted with anti-mouse immunoglobulin G. The bands correlated to a, c in (a) are shown.

Table 1.

Immunoprecipitated bands (Fig. 8) were cut and analysed by LC/MS/MS

| (a) < myosin, heavy polypeptide 9, non-muscle isoform 1 –Mus musculus; 226 000 > | |

| 1 | MAQQAADKYL YVDKNFINNP LAQADWAAKK LVWVPSSKNG FEPASLKEEV |

| 51 | GEEAIVELVE NGKKVKVNKD DIQKMNPPKF SKVEDMAELT CLNEASVLHN |

| 101 | LKERYYSGLI YTYSGLFCVV INPYKNLPIY SEEIVEMYKG KKRHEMPPHI |

| 151 | YAITDTAYRS MMQDREDQSI LCTGESGAGK TENTKKVIQY LAHVASSHKS |

| 201 | KKDQGELERQ LLQANPILEA FGNAKTVKND NSSRFGKFIR INFDVNGYIV |

| 251 | GANIETYLLE KSRAIRQAKE ERTFHIFYYL LSGAGEHLKT DLLLEPYNKY |

| 301 | RFLSNGHVTI PGQQDKDMFQ ETMEAMRIMG IPEDEQMGLL RVISGVLQLG |

| 351 | NIAFKKERNT DQASMPDNTA AQKVSHLLGI NVTDFTRGIL TPRIKVGRDY |

| 401 | VQKAQTKEQA DFAIEALAKA TYERMFRWLV LRINKALDKT KRQGASFIGI |

| 451 | LDIAGFEIFD LNSFEQLCIN YTNEKLQQLF NHTMFILEQE EYQREGIEWN |

| 501 | FIDFGLDLQP CIDLIEKPAG PPGILALLDE ECWFPKATDK SFVEKVVQEQ |

| 551 | GTHPKFQKPK QLKDKADFCI IHYAGKVDYK ADEWLMKNMD PLNDNIATLL |

| 601 | HQSSDKFVSE LWKDVDRIIG LDQVAGMSET ALPGAFKTRK GMFRTVGQLY |

| 651 | KEQLAKLMAT LRNTNPNFVR CIIPNHEKKA GKLDPHLVLD QLRCNGVLEG |

| 701 | IRICRQGFPN RVVFQEFRQR YEILTPNSIP KGFMDGKQAC VLMIKALELD |

| 751 | SNLYRIGQSK VFFRAGVLAH LEEERDLKIT DVIIGFQACC RGYLARKAFA |

| 801 | KRQQQLTAMK VLQRNCAAYL RLRNWQWWRL FTKVKPLLNS IRHEDELLAK |

| 851 | EAELTKVREK HLAAENRLTE METMQSQLMA EKLQLQEQLQ AETELCAEAE |

| 901 | ELRARLTAKK QELEEICHDL EARVEEEEER CQYLQAEKKK MQQNIQELEE |

| 951 | QLEEEESARQ KLQLEKVTTE AKLKKLEEDQ IIMEDQNCKL AKEKKLLEDR |

| 1001 | VAEFTTNLME EEEKSKSLAK LKNKHEAMIT DLEERLRREE KQRQELEKTR |

| 1051 | RKLEGDSTDL SDQIAELQAQ IAELKMQLAK KEEELQAALA RVEEEAAQKN |

| 1101 | MALKKIRELE TQISELQEDL ESERASRNKA EKQKRDLGEE LEALKTELED |

| 1151 | TLDSTAAQQE LRSKREQEVS ILKKTLEDEA KTHEAQIQEM RQKHSQAVEE |

| 1201 | LADQLEQTKR VKATLEKAKQ TLENERGELA NEVKALLQGK GDSEHKRKKV |

| 1251 | EAQLQELQVK FSEGERVRTE LADKVTKLQV ELDSVTGLLS QSDSKSSKLT |

| 1301 | KDFSALESQL QDTQELLQEE NRQKLSLSTK LKQMEDEKNS FREQLEEEEE |

| 1351 | AKRNLEKQIA TLHAQVTDMK KKMEDGVGCL ETAEEAKRRL QKDLEGLSQR |

| 1401 | LEEKVAAYDK LEKTKTRLQQ ELDDLLVDLD HQRQSVSNLE KKQKKFDQLL |

| 1451 | AEEKTISAKY AEERDRAEAE AREKETKALS LARALEEAME QKAELERLNK |

| 1501 | QFRTEMEDLM SSKDDVGKSV HELEKSKRAL EQQVEEMKTQ LEELEDELQA |

| 1551 | TEDAKLRLEV NLQAMKAQFE RDLQGRDEQS EEKKKQLVRQ VREMEAELED |

| 1601 | ERKQRSMAMA ARKKLEMDLK DLEAHIDTAN KNREEAIKQL RKLQAQMKDC |

| 1651 | MRELDDTRAS REEILAQAKE NEKKLKSMEA EMIQLQEELA AAERAKRQAQ |

| 1701 | QERDELADEI ANSSGKGALA LEEKRRLEAR IAQLEEELEE EQGNTELIND |

| 1751 | RLKKANLQID QINTDLNLER SHAQKNENAR QQLERQNKEL KAKLQEMESA |

| 1801 | VKSKYKASIA ALEAKIAQLE EQLDNETKER QAASKQVRRT EKKLKDVLLQ |

| 1851 | VEDERRNAEQ FKDQADKAST RLKQLKRQLE EAEEEAQRAN ASRRKLQREL |

| 1901 | EDATETADAM NREVSSLKNK LRRGDLPFVV TRRIVRKGTG DCSDEEVDGK |

| 1951 | ADGADAKAAE |

| (b) < Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase [ammonia], mitochondrial precursor –Mus musculus 164 000 > | |

| 1 | MTRILTACKV VKTLKSGFGF ANVTTKRQWD FSRPGIRLLS VKAKTAHIVL |

| 51 | EDGTKMKGYS FGHPSSVAGE VVFNTGLGGY PEALTDPAYK GQILTMANPI |

| 101 | IGNGGAPDTT ARDELGLNKY MESDGIKVAG LLVLNYSNDY NHWLATKSLG |

| 151 | QWLQEEKVPA IYGVDTRMLT KIIRDKGTML GKIEFEGQSV DFVDPNKQNL |

| 201 | IAEVSTKDVK VFGKGNPTKV VAVDCGIKNN VIRLLVKRGA EVHLVPWNHD |

| 251 | FTQMEYDGLL IAGGPGNPAL AQPLIQNVKK ILESDRKEPL FGISTGNIIT |

| 301 | GLAAGAKSYK MSMANRGQNQ PVLNITNRQA FITAQNHGYA LDNTLPAGWK |

| 351 | PLFVNVNDQT NEGIMHESKP FFAVQFHPEV SPGPTDTEYL FDSFFSLIKK |

| 401 | GKGTTITSVL PKPALVASRV EVSKVLILGS GGLSIGQAGE FDYSGSQAVK |

| 451 | AMKEENVKTV LMNPNIASVQ TNEVGLKQAD AVYFLPITPQ FVTEVIKAER |

| 501 | PDGLILGMGG QTALNCGVEL FKRGVLKEYG VKVLGTSVES IMATEDRQLF |

| 551 | SDKLNEINEK IAPSFAVESM EDALKAADTI GYPVMIRSAY ALGGLGSGIC |

| 601 | PNKETLIDLG TKAFAMTNQI LVERSVTGWK EIEYEVVRDA DDNCVTVCNM |

| 651 | ENVDAMGVHT GDSVVVAPAQ TLSNAEFQML RRTSVNVVRH LGIVGECNIQ |

| 701 | FALHPTSMEY CIIEVNARLS RSSALASKAT GYPLAFIAAK IALGIPLPEI |

| 751 | KNVVSGKTSA CFEPSLDYMV TKIPRWDLDR FHGTSSRIGS SMKSVGEVMA |

| 801 | IGRTFEESFQ KALRMCHPSV DGFTPRLPMN KEWPANLDLK KELSEPSSTR |

| 851 | IYAIAKALEN NMSLDEIVRL TSIDKWFLYK MRDILNMDKT LKGLNSDSVT |

| 901 | EETLRKAKEI GFSDKQISKC LGLTEAQTRE LRLKKNIHPW VKQIDTLAAE |

| 951 | YPSVTNYLYV TYNGQEHDIK FDEHGIMVLG CGPYHIGSSV EFDWCAVSSI |

| 1001 | RTLRQLGKKT VVVNCNPETV STDFDECDKL YFEELSLERI LDIYHQEACN |

| 1051 | GCIISVGGQI PNNLAVPLYK NGVKIMGTSP LQIDRAEDRS IFSAVLDELK |

| 1101 | VAQAPWKAVN TLNEALEFAN SVGYPCLLRP SYVLSGSAMN VVFSEDEMKR |

| 1151 | FLEEATRVSQ EHPVVLTKFV EGAREVEMDA VGKEGRVISH AISEHVEDAG |

| 1201 | VHSGDATLML PTQTISQGAI EKVKDATRKI AKAFAISGPF NVQFLVKGND |

| 1251 | VLVIECNLRA SRSFPFVSKT LGVDFIDVAT KVMIGESIDE KRLPTLEQPI |

| 1301 | IPSDYVAIKA PMFSWPRLRD ADPILRCEMA STGEVACFGE GIHTAFLKAM |

| 1351 | LSTGFKIPQK GILIGIQQSF RPRFLGVAEQ LHNEGFKLFA TEATSDWLNA |

| 1401 | NNVPATPVAW PSQEGQNPSL SSIRKLIRDG SIDLVINLPN NNTKFVHDNY |

| 1451 | VIRRTAVDSG IALLTNFQVT KLFAEAVQKS RTVDSKSLFH YRQYSAGKAA |

| (c) < Actin –Mus musculus 42 000 > | |

| 1 | MCDDEETTAL VCDNGSGLVK AGFAGDDAPR AVFPSIVGRP RHQGVMVGMG |

| 51 | QKDSYVGDEA QSKRGILTLK YPIEHGIITN WDDMEKIWHH TFYNELRVAP |

| 101 | EEHPTLLTEA PLNPKANREK MTQIMFETFN VPAMYVAIQA VLSLYASGRT |

| 151 | TGIVLDSGDG VTHNVPIYEG YALPHAIMRL DLAGRDLTDY LMKILTERGY |

| 201 | SFVTTAEREI VRDIKEKLCY VALDFENEMA TAASSSSLEK SYELPDGQVI |

| 251 | TIGNERFRCP ETLFQPSFIG MESAGIHETT YNSIMKCDID IRKDLYANNV |

| 301 | LSGGTTMYPG IADRMQKEIT ALAPSTMKIK IIAPPERKYS VWIGGSILAS |

| 351 | LSTFQQMWIS KQEYDEAGPS IVHRKCF |

| (c) < Argininosuccinate synthase –Mus musculus 46 000 > | |

| 1 | MKWVTFLLLL FVSGSAFSRG VFRREAHKSE IAHRYNDLGE QHFKGLVLIA |

| 51 | FSQYLQKCSY DEHAKLVQEV TDFAKTCVAD ESAANCDKSL HTLFGDKLCA |

| 101 | IPNLRENYGE LADCCTKQEP ERNECFLQHK DDNPSLPPFE RPEAEAMCTS |

| 151 | FKENPTTFMG HYLHEVARRH PYFYAPELLY YAEQYNEILT QCCAEADKES |

| 201 | CLTPKLDGVK EKALVSSVRQ RMKCSSMQKF GERAFKAWAV ARLSQTFPNA |

| 251 | DFAEITKLAT DLTKVNKECC HGDLLECADD RAELAKYMCE NQATISSKLQ |

| 301 | TCCDKPLLKK AHCLSEVEHD TMPADLPAIA ADFVEDQEVC KNYAEAKDVF |

| 351 | LGTFLYEYSR RHPDYSVSLL LRLAKKYEAT LEKCCAEANP PACYGTVLAE |

| 401 | FQPLVEEPKN LVKTNCDLYE KLGEYGFQNA ILVRYTQKAP QVSTPTLVEA |

| 451 | ARNLGRVGTK CCTLPEDQRL PCVEDYLSAI LNRVCLLHEK TPVSEHVTKC |

| 501 | CSGSLVERRP CFSALTVDET YVPKEFKAET FTFHSDICTL PEKEKQIKKQ |

| 551 | TALAELVKHK PKATAEQLKT VMDDFAQFLD TCCKAADKDT CFSTEGPNLV |

| 601 | TRCKDALA |

| (c) < α-actinin-4 –Mus musculus 104 000 > | |

| 1 | MVDYHAANQA YQYGPNSGGG NGAGGGGSMG DYMAQEDDWD RDLLLDPAWE |

| 51 | KQQRKTFTAW CNSHLRKAGT QIENIDEDFR DGLKLMLLLE VISGERLPKP |

| 101 | ERGKMRVHKI NNVNKALDFI ASKGVKLVSI GAEEIVDGNA KMTLGMIWTI |

| 151 | ILRFAIQDIS VEETSAKEGL LLWCQRKTAP YKNVNVQNFH ISWKDGLAFN |

| 201 | ALIHRHRPEL IEYDKLRKDD PVTNLNNAFE VAEKYLDIPK MLDAEDIVNT |

| 251 | ARPDEKAIMT YVSSFYHAFS GAQKAETAAN RICKVLAVNQ ENEHLMEDYE |

| 301 | RLASDLLEWI RRTIPWLEDR VPQKTIQEMQ QKLEDFRDYR RVHKPPKVQE |

| 351 | KCQLEINFNT LQTKLRLSNR PAFMPSEGRM VSDINNGWQH LEQAEKGYEE |

| 401 | WLLNEIRRLE RLDHLAEKFR QKASIHEAWT DGKEAMLKQR DYETATLSDI |

| 451 | KALIRKHEAF ESDLAAHQDR VEQIAAIAQE LNELDYYDSH NVNTRCQKIC |

| 501 | DQWDNLGSLT HSRREALEKT EKQLETIDQL HLEYAKRAAP FNNWMESAME |

| 551 | DLQDMFIVHT IEEIEGLISA HDQFKSTLPD ADREREAILA IHKEAQRIAE |

| 601 | SNHIKLSGSN PYTTVTPQII NSKWEKVQQL VPKRDHALLE EQSKQQSNEH |

| 651 | LRRQFASQAN MVGPWIQTKM EEIGRISIEM NGTLEDQLSH LKQYERSIVD |

| 701 | YKPSLDLLEQ QHQLIQEALI FDNKHTNYTM EHIRVGWEQL LTTIARTINE |

| 751 | VENQILTRDA KGISQEQMQE FRASFNHFDK DHGGALGPEE FKACLISLGY |

| 801 | DVENDRQGDA EFNRIMSVVD PNHSGLVTFQ AFIDFMSRET TDTDTADQVI |

| 851 | ASFKVLAGDK NFITAEELRR ELPPDQAEYC IARMAPYQGP DAAPGALDYK |

| 901 | SFSTALYGES DL |

Upper band (220 000∼250 000) was matched with myosin, heavy polypeptide 9, non-muscle isoform 1 (226 000). Lower band (42 000∼50 000) was matched with actin, α-cardiac muscle, 42 000 actin, cytoplasmic 1 –Mus musculus 42 000 argininosuccinate synthase; α-actinin-4 –Mus musculus 104 000, argininosuccinate synthase –Mus musculus (Mouse) 46 000. Bold letters indicate the fit regions of LS/MS analysis

Discussion

We have shown in this paper that splenectomy prolongs wound healing. Adoptive transfer of spleen cells significantly restored the normal kinetics of wound healing in splenectomized mice. Similar experiments have been performed in hypercholesterolaemic mice. Splenectomy dramatically aggravated atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolaemic apolipoprotein E knockout (apoE–) mice. Transfer of spleen cells from atherosclerotic apoE– mice significantly reduced disease development in young apoE– mice.14 Our experiments and the experiments described by Caligiuri et al.14 suggest that immune responses are not universally detrimental during the development of atherosclerosis nor are they necessarily destructive to tissue in the context of wound healing.

The role of B lymphocytes in wound healing has not been examined in detail.15–17 These works suggested that B lymphocytes are unlikely to play a significant role in the regulation of wound healing. Throughout the course of our studies, we never observed significant numbers of B cells in wounded areas (Fig. 5). However, we did observe antibodies, which were secreted by B cells residing in secondary lymphoid organs, such as spleen or lymph node, bound to damaged tissues. Experiments using nude mice (Fig. 3) and enriched spleen-derived B cells (Fig. 4) revealed that the wound repairing capacity was conferred by B cells. The B-cell protective effects have also been examined in atherosclerosis. Caligiuri et al. showed that in apoE− mice the transfer of B cells enriched by immunomagnetic beads reduced atherosclerotic disease in splenectomized apoE mice to one-quarter of that in splenectomized apoE control mice. We have shown that autoreactive IgG1 antibodies are bound to wounded tissues (Fig. 5). How are these antibodies engaged in wound healing? Again, the experimental results from atherosclerosis mouse models provide hints as to the role of autoantibodies. T15 anti-phosphorylcholine (anti-PC) antibodies bind to apoptotic cells, which display oxidized phospholipid epitopes such as OxLDL, and work to protect from atherosclerosis. However, some antibodies to OxLDL have been shown to block the scavenging effects of macrophages and work to exacerbate atherosclerosis. T15 is secreted from the spleen.19 The antibodies bound to damaged tissues might induce phagocytosis by Fcγ receptors present on neutrophils and macrophages (opsonization).18 It is technically difficult to directly examine whether opsonized damaged tissues were effectively phagocytosed and removed macrophages. As a consequence we used 3% thioglycollate-induced peritoneal macrophages as phagocytes. Zymosan-induced neutrophils from the peritoneum of Green mice were used as target cells. We found that neutrophils damaged by heating were effectively engulfed by macrophages. When damaged neutrophils were opsonized by the serum from sham-operated mice, these were phagocytosed by macrophages more effectively than those opsonized by splenectomized mice (Fig. 6a). Hence, in splenectomized mice neutrophils and macrophages resided longer in wounded tissues (data not shown). The longer residence of macrophages in wounded tissues might enhance some chemokines. We found that the expression of macrophage-recruiting chemokines CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL3 and CXCL3 was up-regulated in wounded tissues of splenectomized mice (Fig. 6b). The delay of neutrophils and macrophages caused the delay of myofibroblasts and endothelial cells, which correlate with angiogenesis (data not shown). However, when we examined the contents of collagen using a hydroxyproline assay in wounded tissues, they were not significantly different between sham-operated and splenectomized mice (data not shown).

Here, we have shown that punch biopsy can enhance antibodies that bind damaged tissues (Fig. 7b). Natural antibodies are antibodies detected in the absence of known immunization.20,21 Repertoires of naturally occurring self-reactive antibodies of different isotypes have been intensively studied during the last three decades.22–25 There are autoreactive IgM that are mainly produced by B1a lymphocytes.26,27 Because autoreactive IgM are mainly produced in the peritoneal cavity,28 splenectomy may have less effect on the production of autoreactive antibodies. When we examined IgM antibodies in this wound system, a large amount of antibodies was bound to damaged tissues. However, the bands detected by IgM between the antibodies in sham-operated mice and splenectomized mice detected by anti-IgM were not different (data not shown). The IgG1 antibodies, which bind to damaged tissues, are therefore different from natural IgM autoantibodies.

Spleen contains various kinds of immune cells including a variety of T cells, the roles of which have been intensively studied by several laboratories.29 Although several reports examined the role of T cells in wound healing,30–32 the results were contradictory, and there are no papers which examined the T-cell helper function to produce autoantibodies. We did not examine further the effects of T cells in this paper but we found that splenectomy in nude mice also delayed the wound healing (Fig. 3). Recently, resident γδ T cells in murine skin have been shown to play unique roles in wound healing by secreting growth factors including keratinocyte growth factor and insulin-like growth factor-1.33 These T cells, so-called dendritic epidermal γδ T cells (DETC), are derived from fetal thymic precursor cells and are present only in skin. Hence splenectomy does not affect DETC.

Our proteins detected by LC–MS/MS include cytoskeletal proteins such as actin, α-actinin-4 and myosin (Table 1). Dighiero 34 examined 36 human monoclonal immunoglobulins and found that 32 were mainly directed against actin. Others include myosin and thyroglobulin. These antibodies were IgM, IgG and IgA subtypes. These results correlate with the results of this study.

There are two types of inflammation: sterile and septic. Inflammation is ‘a process which begins following a sub-lethal injury and ends with complete healing.’ Inflammation is involved in processes as diverse as angiogenesis, wound healing, tissue remodelling and regeneration, and connective tissue formation.35 In septic inflammation, microbial molecules can form complexes with self- or foreign heat-shock proteins (hsp) to facilitate the induction of an effective immune response. Mammalian hsp can bind a broad array of peptides, including short-lived peptides that result from cellular metabolism. These hsp–peptide complexes induce autoantigen-specific immunity.36 Our work in wound healing presented here may be related to hsp–self-antigen complexes. The determination of autoantigens, which are present in wounded tissues, will reveal whether hsp play a role in the process of wound healing. Recent works using computational analyses have suggested that normal humans already have autoantibodies in utero, and it is likely that these autoantibodies have some role in human homeostasis and autoimmunity.37 Further studies will help to understand the roles played by autoantibodies found in healthy individuals, not only in the process of wound healing but also in body defence systems and autoimmune development.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Amano and A. Okamoto for advice for proteomic analysis. We thank Y. Yamakawa for technical assistance with LC–MS/MS and M. Tanaka for technical assistance with confocal imaging. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Martin P. Wound healing—aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Sci Rev. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner S, Grose R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:835–70. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2003.83.3.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillitzer R, Goebeler M. Chemokines in cutaneous wound healing. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:513–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin P, Leibovich SJ. Inflammatory cells during wound repair: the good, the bad and the ugly. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mori R, Kondo T, Ohshima T, Ishida T, Mukaida N. Accelerated wound healing in tumor necrosis factor receptor p55-deficient mice with reduced leukocyte infiltration. FASEB J. 2002;16:963–74. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0776com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin ZQ, Kondo T, Ishida Y, Takayasu T, Mukaida N. Essential involvement of IL-6 in the skin wound-healing process as evidenced by delayed wound healing in IL-6-deficient mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:713–21. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0802397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low QE, Drugea IA, Duffner LA, Quinn DG, Cook DN, Rollins BJ, Kovacs EJ, DiPietro LA. Wound healing in MIP-1alpha(−/−) and MCP-1(−/−) mice. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:457–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61717-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelhardt E, Toksoy A, Goebeler M, Debus S, Brocker EB, Gillitzer R. Chemokines IL-8, GRO, MCP-1, IP-10, and Mig are sequentially and differentially expressed during phase-specific infiltration of leukocyte subsets in human wound healing. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1849–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65699-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jameson J, Ugarte K, Chen N, Yachi P, Fuchs E, Boismenu R, Havran WL. A role for skin T cells in wound repair. Science. 2002;296:747–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1069639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girardi M, Lewis J, Glusac E, Filler RB, Geng L, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE. Resident skin-specific T cells provide local, nonredundant regulation of cutaneous inflammation. J Exp Med. 2002;195:855–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishimune Y. ‘Green mice’ as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:313–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito S, Sawada M, Haneda M, Fujii S, Oh-Hashi K, Kiuchi K, Takahashi M, Isobe K. Amyloid-beta peptides induce cell proliferation and macrophage colony-stimulating factor expression via the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway in cultured Ra2 microglial cells. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1995–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishio N, Okawa Y, Sakurai H, Isobe K. Neutrophil depletion delays wound repair in aged mice. AGE. 2008;30:11–9. doi: 10.1007/s11357-007-9043-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caligiuri J, Nicoletti A, Poirier B, Hansson GK. Protective immunity against atherosclerosis carried by B cells of hypercholesterolemic mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:745–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI07272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JE, Barbul A. Understanding the role of immune regulation in wound healing. Am J Surg. 2004;187:11S–6S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(03)00296-4. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin CW, Muir IF. The role of lymphocytes in wound healing. Br J Plast Surg. 1990;43:655–62. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(90)90185-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyce DE, Jones WD, Ruge F, Harding KG, Moore K. The role of lymphocytes in human dermal wound healing. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:59–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witztum JL. Splenic immunity and atherosclerosis: a glimpse into a novel paradigm? J Clin Invest. 2002;109:721–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI15310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen IR, Norins LC. Natural human antibodies to gram-negative bacteria: immunoglobulins G, A, and M. Science. 1966;152:1257–9. doi: 10.1126/science.152.3726.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD, Avrameas S. Natural autoantibodies. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:812–8. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura M, Burastero SE, Ueki Y, Larrick JW, Notkins AL, Casali P. Probing the normal and autoimmune B cell repertoire with Epstein–Barr virus: frequency of B cells producing monoreactive high affinity autoantibodies in patients with Hashimoto’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 1988;141:4165–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mouthon L, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Nobrega A, Barreau C, Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD. The self reactive antibody repertoire of normal human serum IgM is acquired in early childhood and remains conserved throughout life. Scand J Immunol. 1996;4:243–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1996.d01-306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dighiero G, Guilbert B, Fermand JP, Lymberi P, Danon F, Avrameas S. Thirty-six human monoclonal immunoglobulins with antibody activity against cytoskeleton proteins, thyroglobulin, and native DNA: immunologic studies and clinical correlations. Blood. 1983;62:264–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steele EJ, Cunningham AJ. High proportion of Ig producing cells making autoantibody in normal mice. Nature. 1978;274:483–6. doi: 10.1038/274483a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herzenberg LA. B-1 cells: the lineage question revisited. Immunol Rev. 2000;175:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayakawa K, Hardy RR, Honda M, Herzenberg LA, Steinberg AD. Ly-1 B cells: functionally distinct lymphocytes that secrete IgM autoantibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2494–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.8.2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lalor PA, Morahan G. The peritoneal Ly-1 (CD5) B cell repertoire is unique among murine B cell repertoires. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:485–92. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baum CL, Arpey CJ. Normal cutaneous wound healing: clinical correlation with cellular and molecular events. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:674–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31612. Discussion 686. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barbul A, Breslin RJ, Woodyard JP, Wasserkrug HL, Efron G. The effect of in vivo T helper and T suppressor lymphocyte depletion on wound healing. Ann Surg. 1989;209:479–83. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198904000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Efron JE, Frankel HL, Lazarou SA, Wasserkrug HL, Barbul A. Wound healing and T-lymphocytes. J Surg Res. 1990;48:460–3. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(90)90013-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis PA, Corless DJ, Aspinall R, Wastell C. Effect of CD4(+) and CD8(+) cell depletion on wound healing. Br J Surg. 2001;88:298–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharp LL, Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Havran WL. Dendritic epidermal T cells regulate skin homeostasis through local production of insulin-like growth factor 1. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:73–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dighiero G. Monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis – a frequent premalignant condition. N Engl J Med. 2008;7:359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0804663. 638–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen IR. Discrimination and dialogue in the immune system. Semin Immunol. 2000;12:215–9. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quintana FJ, Cohen IR. Heat shock proteins as endogenous adjuvants in sterile and septic inflammation. J Immunol. 2005;175:2777–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen IR. Real and artificial immune systems: computing the state of the body. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:569–74. doi: 10.1038/nri2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]