Abstract

Mutations in the electrogenic Na+/nHCO3− cotransporter (NBCe1, SLC4A4) cause severe proximal renal tubular acidosis, glaucoma, and cataracts in humans, indicating NBCe1 has a critical role in acid-base homeostasis and ocular fluid transport. To better understand the homeostatic roles and protein ontogeny of NBCe1, we have cloned, localized, and downregulated NBCe1 expression in zebrafish, and examined its transport characteristics when expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Zebrafish NBCe1 (zNBCe1) is 80% identical to published mammalian NBCe1 cDNAs. Like other fish NBCe1 clones, zebrafish NBCe1 is most similar to the pancreatic form of mammalian NBC (Slc4a4-B) but appears to be the dominant isoform found in zebrafish. In situ hybridization of embryos demonstrated mRNA expression in kidney pronephros and eye by 24 h postfertilization (hpf) and gill and brain by 120 hpf. Immunohistochemical labeling demonstrated expression in adult zebrafish eye and gill. Morpholino knockdown studies demonstrated roles in eye and brain development and caused edema, indicating altered fluid and electrolyte balance. With the use of microelectrodes to measure membrane potential (Vm), voltage clamp (VC), intracellular pH (pHi), or intracellular Na+ activity (aNai), we examined the function of zNBCe1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Zebrafish NBCe1 shared transport properties with mammalian NBCe1s, demonstrating electrogenic Na+ and HCO3− transport as well as similar drug sensitivity, including inhibition by 4,4′-diiso-thiocyano-2,2′-disulfonic acid stilbene and tenidap. These data indicate that NBCe1 in zebrafish shares many characteristics with mammalian NBCe1, including tissue distribution, importance in systemic water and electrolyte balance, and electrogenic transport of Na+ and HCO3−. Thus zebrafish promise to be useful model system for studies of NBCe1 physiology.

Keywords: intracellular pH, acid base, membrane current, bicarbonate transport, Xenopus oocyte, teleost, Danio rerio, cellular buffering, immunohistochemistry, in situ, electrophysiology

in humans and terrestrial vertebrates, the kidney controls systemic acid-base homeostasis in part by reabsorbing filtered bicarbonate in the proximal tubule. The majority of renal bicarbonate reabsorption occurs in the form of electrogenic Na+/nHCO3− cotransport. This activity was originally described in 1983 in the salamander kidney (Ambystoma tigrinum) (5). The transporter responsible was finally cloned in 1997 from the same organism and tissue and named for its activity NBCe1 (38). NBCe1 is the product of the slc4a4 gene. The importance of NBCe1 to acid-base homeostasis has been shown in patients with autosomal recessive SLC4A4 mutations manifesting pathophysiologies such as proximal renal tubular acidosis (pRTA), glaucoma, cataracts, and band-keratopathy (11, 12, 22, 23).

The slc4a4 gene is highly conserved. It has been described in mammals including the human, mouse, and rat (4, 11, 12, 22, 23, 37), in amphibians such as salamander (5, 38), and in both freshwater and saltwater fish such as rainbow trout, dace, and benthic eelpout (10, 21, 31).

Several studies have demonstrated the molecular and systemic functions of NBCe1. At the molecular level, the major transport characteristics of NBCe1 are cotransport of Na+ and HCO3−, sensitivity to the stilbene inhibitor 4,4′-diiso-thiocyano-2,2′-disulfonic acid stilbene (DIDS), and electrogenicity (38). Systemic functions in pH homeostasis and in eye development and/or maintenance are demonstrated in humans by patients bearing mutations in SLC4A4 as described above. In the freshwater fish Osorezan dace and rainbow trout, NBCe1 is involved in adaptation to acidic conditions (21, 32). In the euryhaline pufferfish megafugu, NBCe1 seems to mediate adaptation to increased water osmolarity (26).

Zebrafish provide a highly tractable vertebrate model system for studying integrated, tissue-level function and pathology (13, 19). This is especially true in the case of a highly conserved gene such as slc4a4. To assess the utility of the zebrafish model system for studies of NBCe1, we cloned an NBC-like cDNA from zebrafish. In situ hybridization demonstrated NBCe1 expression in the pronephros by 18 h postfertilization (hpf), in the eyes by 24 hpf, and in the brain by 48 hpf. Knockdown of NBCe1 by morpholino (MO) injection produced marked hydrocephalus by 54 h postfertilization. Expression of the zebrafish NBCe1 clone in Xenopus oocytes demonstrated that the cDNA encodes an electrogenic Na+/nHCO3− cotransporter with transport properties similar to its mammalian ortholog.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Zebrafish.

Zebrafish were maintained and raised as described (48). All procedures were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Adult zebrafish for RNA isolation, zNBCe1 cloning, and immunohistochemistry were AB wild type. Embryos for in situ hybridization, morpholino injection, and immunohistochemistry were Tü/AB.

RNA isolation.

Kidneys were dissected from adult zebrafish and collected in 4°C RNA-Later (Ambion, Austin, TX) during the dissection. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), precipitated with isopropanol and glycogen, and resuspended in DNase, RNAse-free water. Total RNA (1 μg) was used as template for reverse transcription (SuperScript II, Life Technologies).

zNBCe1 cloning.

A 5′ expressed sequence tag (EST) (accession no. AL918909, provided by J. Peng, Lab of Functional Genomics, Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore) and a 3′ EST (accession no. BG985720, provided by I. B. Dawid, Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD) corresponding to human and dace-NBCe1 were identified using a tblastn search of the zebrafish EST database. These plasmids were bidirectionally sequenced (W. M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory, New Haven, CT), and the resulting sequences were used to design forward (zNBCe1_f; 5′-CTTCCCAAAATGAGC) and reverse (zNBCe1_r; 5′-CAGCGCCTTCCTCACA) PCR primers. One microliter of first strand synthesis was used as template in a 25-μl PCR reaction of 30 cycles using ExTaq (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA): 30 s 95°C, 30 s 58°C, and 4 min 70°C. PCR product was subcloned into pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen). Positive clones from three different RTs were sequenced to determine the consensus zebrafish NBCe1 sequence (GenBank accession no. AY727858).

zNBCe1 genomic structure.

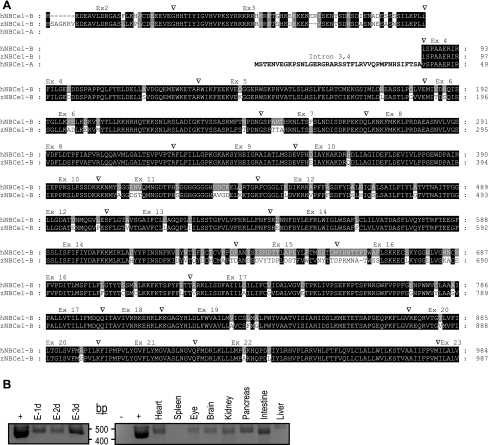

A blast search of zNBCe1 cDNA sequence against the NIH Danio rerio genomic database (Zv7) revealed one gene (zebrafish chromosome 5) containing the full-length sequence. The zNBCe1 cDNA sequence was compared with the genomic sequence to determine the intron-exon boundaries (see Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Na/nHCO3− (zNBCe1) sequence and gene structure. A: zNBCe1 was cloned and sequenced from adult zebrafish kidneys by RT-PCR using gene-specific primers based on 5′ and 3′ expressed sequence tag (EST) sequences. The zNBCe1 amino terminus corresponds to human NBCe1-B not NBCe1-A (the isoform specific sequence in bold text), the alternatively spliced human kidney form. Inverted triangles indicate intron/exon boundaries. Since the NBCe1 gene structure is identical for the zebrafish NBCe1 gene and the human SLC4A4 (NBCe1) gene, “Ex#” indicate the exon number in both genes. Zebrafish NBCe1 is found on zebrafish chromosome 5, whereas human NBCe1 is located at human chromosome 14q21. The black shading indicates amino acid residues that are identical in zNBCe1 and human NBCe1, whereas grey shading indicates similar functional groups. B: RT-PCR indicating zNBCe1-B mRNA distribution (“+” is the excised zNBCe1-B cDNA; “−” is no DNA template). Left, zNBCe1-B mRNA is found 1 dpf, 2 dpf, and 3 dpf (E-1d, E-2d, E-3d, respectively) zebrafish embryos.

zNBCe1 mRNA distribution.

Total RNA was isolated from wild-type zebrafish embryos and adult zebrafish tissues using RNAeasy (Qiagen). Total RNA (1 μg) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with an oligo-dT primer and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) according to manufacture instructions in a 20-μl; reaction. We used zNBCe1-B specific primers [forward primer: MFR-146 (zNBCe1-f4) 5′-ATGAGCGCCGGCAAGAGG-3′ (bp 10–27; protein seq “MSAGKR”) and reverse primer: MFR-662 (zNBC-LRTCrev) 5′-CCCTTCTCTATACACGTCCTAAGCT-3′ (bp 500–524; protein seq “LRTCIEK”)] with 1 μl RT in a 25-μl reaction. The PCR protocol was 31 cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 15 s at 60°C, 60 s at 72°C, followed by a final extension of 5 min. The PCR products were resolved under UV (260 nm) of an ethidium bromide stained 2% agarose gel. PCR products from the brain, eye, and kidney were sequence (Mayo Clinic DNA core center) and verified to be identical to the target zNBCe1-B target sequence.

In situ hybridization.

Whole mount in situ hybridization was performed as previously described (47). Embryos were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes to zNBCe1 and detected using anti-DIG-AP (1:5,000) and NBT/BCIP substrate (Roche Diagnostics). After the color reaction was stopped, embryos were washed with methanol and equilibrated in clearing solution (1/3 benzoyl-alcohol and 2/3 benzoyl-benzoate) and photographed using a Leica MZ12 dissecting microscope (Germany). Embryos sectioned after in situ hybridization were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde then dehydrated through a series of methanol/PBST washes of 25%/75%, 50%/50%, 75%/25%, and 100% methanol (10 min each) followed by embedding in JB-4 glycolmethacrylate (Polysciences). A Riechert-Jung Supercut 2065 (Leica) microtome was used to generate 10-μm sections. A Nikon E800 microscope equipped with a Spot Image digital camera was used for photography.

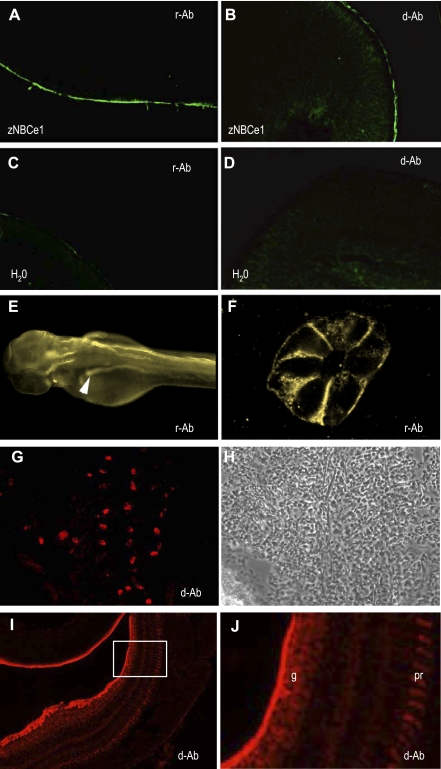

NBCe1 immunolocalization.

To localize zNBCe1 in zebrafish embryos, we used a rabbit anti-NBCe1 primary antibody against the 108 COOH-terminal amino acids of rkNBCe1 (r-Ab in Fig. 3) (43). Whole mount immunostaining was carried out as previously described (14) using a Cy3-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody. After being embedded in JB-4 (Polysciences), stained embryos were sectioned at 5 μm and imaged on a Bio-Rad Radiance2000 confocal microscope.

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescent detection of NBCe1 in zebrafish embryos and adults. Immunohistochemistry showing specific labeling of zebrafish NBCe1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes by ant-rat (r-Ab) (A) or anti-Dace NBCe1 (d-Ab) (B) but no specific labeling by either r-Ab or d-Ab in water-injected oocytes (C, D). Immunohistochemistry using r-Ab labeled the anterior tubules and ducts of the pronephros at 56 hpf (E). Sections of embryos following immunohistochemistry showed labeling at basolateral epithelial cell membranes in the pronephros (F). Cryosections of adult zebrafish gill labeled with d-Ab (G) and corresponding phase-contrast image (H). Cryosections of adult zebrafish retina labeled with d-Ab (I). Enlargement of the boxed area in I shows distinct labeling in the ganglion cell layer (g) and photoreceptor layer (pr) (J).

To localize the zNBCe1 protein in adult zebrafish, we used a rabbit anti-DaceNBCe1 (d-Ab in Fig. 3) primary antibody against a histidine-tag, 42-residue, COOH-terminal fragment [SDFPAIENVPSIKISMETMEQDPVLGEKPSDRNKPMSFLTPY] (provided by S. Hirose, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo, Japan) (21). To verify that these NBCe1 antibodies recognized recombinant zNBCe1, we first tested them on fixed, cryosectioned oocytes expressing zNBCe1 as previously described for other transporters (43, 45). Both antibodies showed plasma membrane staining in zNBCe1 oocytes but not water-injected controls (see Fig. 3, A–D).

Adult zebrafish were immersion fixed in PLP (10 mM NaIO4, 75 mM l-lysine, 2% PFA in PBS pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C followed by incubation in 30% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4°C. Fish were embedded in Tissue Tek (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and cut in 20-μm sections on a cryotome (Leica). Sections were rehydrated in PBS and blocked in blocking buffer (10% normal donkey serum, 1% BSA, 0.1% Triton-X in PBS, pH 7.2). Sections were incubated with the anti-Dace NBCe1 antibody overnight at 4°C followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG for 1 h at room temperature. Epifluorescent images were captured using a Zeiss AxioVert 25 microscope and acquired with an AxioCam digital camera and AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss).

Morpholino studies.

A morpholino antisense oligonucleotide (MO) (Gene Tools, Philomath, OR) targeting the start codon of zNBCe1 was used. The ATG start site blocking morpholino sequence was 5′-GGCGCTCATTTTGGGAAGTTGAATC-3′ and the control 5-mismatch morpholino seqence was 5′- GGCCCTCTTTTAGGGTAGTTCAATC-3′. Morphant oligonucleotides were diluted in 100 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 0.1% phenol red (Sigma) (pH 7.2). A 250 μM MO solution (4.6 nl) was injected per embryo using a nanoliter 2000 microinjector (World Precision Instruments). The estimated final cytoplasmic amount of MO per embryo was ∼9 ng. A 5-base mismatch MO was used as a negative control and did not cause toxicity or induce morphant phenotypes.

Oocyte isolation and injection.

Female Xenopus laevis were purchased from Xenopus Express (Beverly Hills, FL). Oocytes were removed and dissociated with collagenase as previously described (37). The procedure was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). To optimize zNBCe1 functional expression in Xenopus oocytes, we subcloned the zNBCe1 orf into an oocyte expression vector pGEMHE (50). Capped zNBCe1 cRNA was synthesized using a linearized cDNA template and the T7 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). Oocytes were injected with 50 nl of zNBCe1 cRNA (0.5 mg/ml) or water and incubated at 18°C in OR3 media (37). Oocytes were studied 3–10 days after injection.

Electrophysiology.

Experimental solutions were identical to those used previously (44). All solutions were either ND96 (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) or iso-osmotic ion replacements as described (44). We used both 1.5% CO2-10 mM HCO3− (pH 7.5) and 5% CO2-33 mM HCO3− (pH 7.5) solutions. The data reported here uses the 5% CO2 solutions to facilitate the comparison to the human NBCe1 studies we have published (7, 12).

Two electrodes voltage clamp.

Oocyte membrane currents were recorded using an OC-725C voltage clamp (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT), filtered at 2–5 kHz, digitized at 10 kHz, and recorded with Pulse software, and data were analyzed using the PulseFit program (HEKA) as previously (44). For periods when current-voltage (I-V) protocols were not being run, oocytes were clamped at a holding potential (Vh) of −60 mV; and the current was constantly monitored and recorded at 1 Hz. I-V protocols consisted of 100-ms steps from −160 mV to +60 mV in 20-mV steps as previously described (44). Voltage dependence of zNBCe1 transport was determined by plotting the mean steady-state current against voltage as previously reported for rat kidney NBCe1 and hkNBCe1 (12, 44).

Ion-selective microelectrodes.

Ion-selective microelectrodes were used to monitor intracellular pH (pHi) and intracellular Na+ activity (aNai) of zNBCe1 and water-injected oocytes as previously described (37, 39, 44). pHi and Na+ microelectrodes had slopes of at least −54 mV/pH unit or decade, respectively.

Calculations.

Oocytes were perfused with ND96 for 5 min at which time initial pHi or initial aNai was measured (Tables 1 and 2). The solution was switched to CO2/HCO3− for 8–10 min (i.e., pHi and Vm or I plateau) and the final pHi or final aNai was measured. [HCO3−]i was calculated from the Henderson-Hasselbach equation and buffering power (βT) as βT = Δ[HCO3−]i/ΔpHi (40). βT is an apparent β in the case of NBCe1 oocytes because the acid-base transporter zNBCe1 or hkNBCe1 is functionally “added” to the “true” buffering power of the H2O-injected oocytes. Thus ΔβNBCe1 can be represented as the difference of βT (NBCe1 oocytes) and βT (H2O oocytes). “ND96” values refer to responses elicited by removal of CO2/HCO3− Oocytes came from at least four separate donor animals.

Table 1.

Nonvoltage clamped versus clamped pHi measurements

| Condition | Units | zNBCe1 (Unclamped) | zNBCe1 (Clamped at −60 mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial pHi | 7.53±0.09 (8) | 7.57±0.06 (7) | |

| Final pHi | 7.14±0.08 (8) | 7.25±0.06 (7) | |

| pHi | −0.39±0.04 (8) | −0.32±0.01 (7) | |

| ΔpHi (0 Na+-CO2) | −0.04±0.02 (11) | −0.06±0.01 (7) | |

| [HCO3−]i | mM | 13.4±2.1 (8) | 16.2±2.4 (7) |

| Apparent βT | mM/pH unit | 37.6±8.8 (8) | 50.8±8.0 (7) |

| ΔβNBCe1 | mM/pH unit | 20 | 28 |

| dpHi/dt | (×10−5 pH units·s−1) | ||

| CO2/HCO3− | dpHi/dt | −357.6±59.9 (8) | −285±26.6 (7) |

| 0 Na+-CO2 | dpHi/dt | −40.1±21.3 (12) | −67.1±13.2 (7) |

| ND96 wash | dpHi/dt | 247.1±36.8 (8) | 149.0±14.7 (7) |

| Initial Vm | ΔVm (mV) | −39.0±2.9 (26) | |

| CO2/HCO3− | mV | −39.9±4.1 (22) | |

| 0 Na+-CO2 | mV | 40.1±4.9 (14) | |

| Final Vm | mV | −20.4±2.2 (8) | |

| Im | (nA) @ 60 mV | ||

| Basal | nA | −63.8±12.4 (7) | |

| CO2/HCO3− | nA | 282.6±15.9 (7) | |

| 0 Na+-CO2 | nA | −236.0±13.3 (7) |

Calculations are as indicated in materials and methods and results. pHi, intracellular pH; Vm, membrane potential. ΔβNBCe1 is βT(zNBCe1) − βT(water). Water experimental data are from Ref. 12. Voltage-clamped data were collected using 3 electrodes to allow clamping with simultaneous pHi measurement (see materials and methods). For pHi and ΔpHi, there are actually four significant figures though three are shown for readability. Data shown are means ± SE. Experimental numbers are indicated in parentheses. All zNBCe1 values are significantly different from water control (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Nonvoltage clamped intracellular Na+ activity measurements

| Condition | Units | zNBCe1 | Water |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial aNai | mM | 3.53±0.14 (22) | 2.95±0.20 (6) |

| CO2/HCO3−aNai | mM | 4.49±0.17 (22) | 3.07±0.23 (6) |

| CO2/HCO3− (ΔaNai) | mM | 0.97±0.07 (22) | 0.12±0.10 (6) |

| 0 Na+ CO2/HCO3−aNai | mM | 3.52±0.16 (12) | 2.78±0.30 (3) |

| 0 Na+ CO2/HCO3− (ΔaNai) | mM | −0.77±0.13 (12) | −0.32±0.09 (3) |

| Final aNai | mM | 4.5±0.18 (10) | 3.04±0.45 (3) |

| Initial Vm | mV | −26.4±1.4 (21) | −26.0±4.6 (3) |

| CO2/HCO3− (ΔVm) | mV | −50.3±2.6 (21) | 1.2±1.1 (6) |

| 0 Na+ CO2/HCO3− (ΔVm) | mV | 41.6±3.4 (12) | −2.7±1.1 (3) |

| Final Vm | mV | −23.8±2.6 (10) | −34.3±2.3 (3) |

Calculations are as indicated in materials and methods and results. aNai, intracellular Na+ activity. Data were collected under nonvoltage-clamped conditions. Data shown are means ± SE. Experimental numbers are indicated in parentheses. All zNBCe1 values are significantly different from water control (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

Zebrafish NBC sequence and gene structure.

The zebrafish NBC gene (slc4a4) (accession no. AY727858) is located on chromosome 5 (genome Zv7_scaffold461) mapping to element NW_001879015.1 spanning bases 34,365K-34,519K bp. Zebrafish NBC cDNA is more similar to NBCe1-B (pancreatic NBCe1, pNBCe1; 82% identity) than the alternatively spliced isoform, NBCe1-A (kidney NBCe1, kNBCe1) (Fig. 1A). Similarly, the zNBCe1 protein shares 79% identity with NBCe1 in Dace, trout, and fugu. Comparison of gene with transcript shows zebrafish slc4a4 has at least 25 exons. The intron-exon boundaries for zebrafish slc4a4 (Fig. 1A) are essentially identical to that reported for the human NBCe1 gene (1).

mRNA localization in zebrafish.

To determine the developmental profile and tissue distribution of zNBCe1-B, we used RT-PCR with primers specific to isoform B (see materials and methods) (Fig. 1B). The expected product (514 bp) is found in 1 dpf, 2 dpf, and 3 dpf embryos (Fig. 1B, left). In adult tissue, this fragment (verified by sequencing) was amplified in the heart, eye, brain, pancreas, kidney, intestine, and liver but not spleen (Fig. 1B, right).

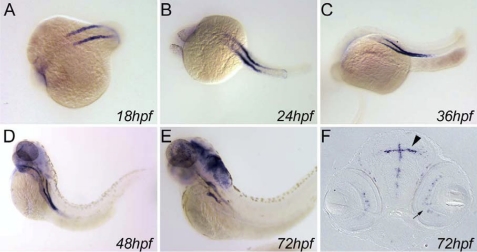

In situ hybridization showed expression of zNBCe1 in the pronephros, brain, and eye (Fig. 2). zNBCe1 transcript was expressed in the pronephros at 18–72 hpf, in the optic cups at 24–72 hpf, and in the brain by 72 hpf. As development progressed, expression in the pronephros intensified in the proximal tubule, while posterior/distal expression diminished. By 72 hpf expression was limited to the proximal tubule segment of the pronephric nephron. At the same stage, NBCe1 was also expressed in the ependymal cells lining the brain ventricles and the inner nuclear layer of the retina.

Fig. 2.

In situ localization of zNBCe1 mRNA in embryos. Whole mount in situ hybridization of NBCe1 showed expression in pronephric tubules, most anterior duct epithelial cells, and optic cup between 18 and 72 hpf (A–E). Note intensification of anterior duct and tubule expression while posterior expression diminished with increasing time postfertilization. E and F: cross sections through the head showed labeling in ependymal cells lining the brain ventricles (arrowhead) and the inner nuclear layer of the retina (arrow).

Zebrafish NBCe1 protein localization.

Since NBCe1 was cloned from zebrafish kidney yet encodes the B isoform (mammalian pancreatic not kidney isoform), we sought to determine its tissue distribution. To assess protein expression in zebrafish tissues, we labeled zebrafish embryos and adults with two NBCe1 antibodies against the NBCe1 COOH-terminus: one against a fusion protein (43) and one against Dace-NBCe1 (21). (Fig. 3). Both antibodies recognized zNBCe1 protein as expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Fig. 3, A–D).

NBCe1 protein was expressed in the zebrafish pronephros specifically at the basolateral membranes (Fig. 3, A and B). In the adult gill, NBCe1 stained intensely in a regularly spaced subpopulation of cells (Fig. 3, C and D). The NBCe1 antibody labeled the eye in several areas (Fig. 3, E and F). The corneal endothelial cells surrounding the lens, but not the lens, showed high immunoreactivity. Likewise, many cell layers in the retina were stained, most notably the inner plexiform layer and photoreceptor layer.

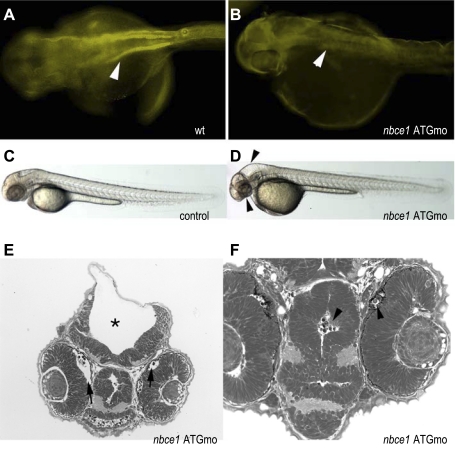

Effects of NBCe1 (Slc4a4) depletion on zebrafish embryonic development.

To identify roles of NBCe1 in zebrafish embryonic development, we depleted NBCe1 protein levels using a translation blocking morpholino (Fig. 4). NBCe1 protein depletion was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4, A and B). Depletion resulted in hydrocephalus, small eyes, retinal distention, and deposition of cell debris or other unknown particles in the brain ventricles and under the retinas compared with control (27).

Fig. 4.

NBCe1 morphants exhibit hydrocephalus and eye defects. A: whole mount immunocytochemistry with anti-NBCe1 highlights the anterior pronephric ducts in wild-type embryos, whereas expression is absent in NBCe1 morpholino-injected embryos (B) Control injected embryos (5-base mismatch MO) (C) are normal at 54 hpf, whereas NBCe1 morphants exhibit hydrocephalus and small eyes (D; arrows). Sections of morpholino injected embryos show extent of hydrocephalus (E, *) and also show distension beneath the forming photoreceptor cell layer (F, arrows in eye). Particulate deposition occurred in the brain ventricles and distended areas under the retinas.

Acid-base transport by zNBCe1.

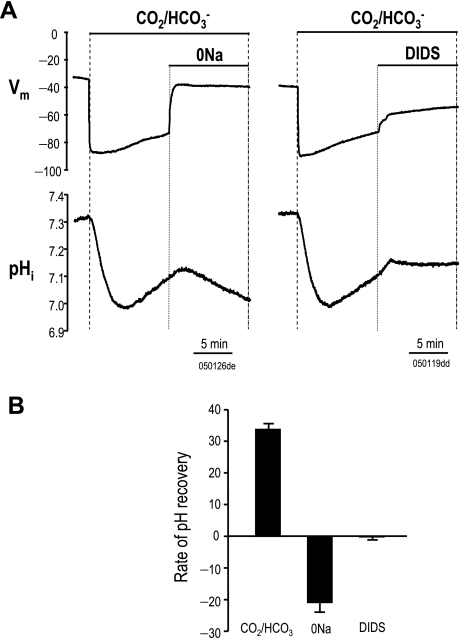

To functionally characterize zNBCe1, we injected Xenopus oocytes with cRNA and measured pHi and membrane voltage as has been done previously for other NBCe1 clones (38, 44). Addition of 5% CO2-33 mM HCO3− (pH 7.5) caused rapid membrane hyperpolarization and acidification (CO2 hydration and H+ release) followed by partial recovery (Fig. 5A). Removal of Na+ (0 Na) in the presence of CO2/HCO3− returned Vm to pre-CO2/HCO3− levels and cell acidified because HCO3− were cotransported away from the cell (reversed the recovery of pHi). Similarly, addition of 200 μM DIDS caused membrane depolarization and blocked pHi recovery. In CO2/HCO3−, the average dpHi/dt (pH/s × 10−5) was 33.7 ± 1.8 vs. −20.8 ± 3.2 with 0 Na+ or −0.2 ± 0.8 in the presence of DIDS (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Effects of 0 Na or DIDS on intracellular pH (pHi) and membrane potentia (Vm) in NBCe1 oocytes. Electrophysiological characterization of oocytes injected with zebrafish NBCe1. A: pHi and Vm changes elicited by CO2/HCO3− addition were blocked by Na removal or 200 μM DIDS. B: average rates of pH recovery (pH/s × 10−5) in CO2/HCO3−, 0 Na, and DIDS are shown. Solid horizontal lines indicate changes to bathing solutions. Dotted vertical lines show durations of bath changes. “050126de” and “050119dd” designate the specific cells from which data were obtained.

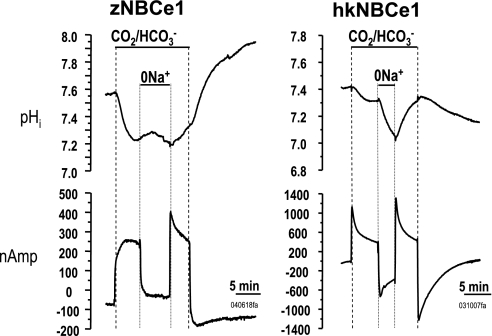

To determine the effect of membrane voltage on transport, we measured pHi and membrane current with membrane voltage clamped at −60 mV. Similar to nonvoltage-clamped conditions, addition of 5% CO2-33 mM HCO3− (pH 7.5) elicited a robust acidification and outward current (NaHCO3 influx) (Fig. 6, Table 1) as has been observed with other electrogenic NBCe clones (3, 12, 21, 37, 38). Similarly, Na+ removal in CO2/HCO3− lowered pHi and elicited an inward current.

Fig. 6.

NBCe1 effects on pHi and membrane current. Comparison of pHi and membrane currents in oocytes injected with zebrafish NBCe1 or human kidney NBCe1 (hkNBCe1). Zebrafish NBC had similar effects on pHi but smaller effects on membrane current than hkNBCe1. Experimental solution and text notations are the same as described for Fig. 5. Note that the y axies (measured current) is different for the zNBCe1 and hkNBCe1 data.

To compare properties of zNBCe1 with mammalian NBCe1, we measured pHi and current in oocytes injected with zNBCe1 or the human kidney NBCe1 (hkNBCe1, NBCe1-A). The resting pHi of zNBCe1 oocytes (7.57) was elevated with respect to both water controls (7.42) and hkNBCe1 oocytes (7.44) (Fig. 6, Table 1) (12). The magnitude of zNBCe1 current resulting from CO2/HCO3− addition was ∼25–50% lower than hkNBCe1 currents (782.3 ± 63.6 nA, n = 16, P < 0.01) (12). Furthermore, the HCO3−-elicited current displayed a rounded waveform and slower developing current rather than the spike and fast current decay of hkNBCe1. Similar experiments in unclamped oocytes showed the rate of acidification with CO2/HCO3− decreased with clamping (−285 vs. −357 × 10−5 pH/s) and the rate of acidification due to Na+ removal also increased (−67 vs. −40 × 10−5 pH/s) compare with the unclamped condition. ΔβNBCe1 also increased from 20 to 28 mM/pH unit with voltage clamping. However, zNBCe1 oocytes accumulated similar amounts of HCO3− (16.1 ± 1 mM, n = 16, P > 0.05) as hkNBCe1-clamped oocytes (12).

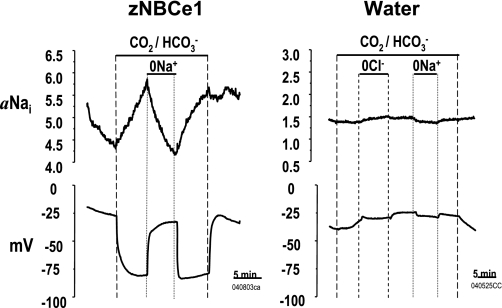

Na+ transport by zNBCe1.

To directly test the ability of zNBCe1 to transport Na+, we used Na+ microelectrodes to measure aNai (in mM) and Vm. Resting aNai was elevated in zNBCe1 oocytes by 0.5–1.0 mM (Table 2). Addition of CO2/HCO3− hyperpolarized zNBCe1 oocytes and further increased aNai (Fig. 7; Table 2). Bath Na+ removal returned aNai levels to pre-CO2/HCO3− levels. After 30 min in CO2/HCO3−, aNai was elevated in zNBCe1 oocytes (4.5 mM) versus water controls (3.0 mM) (Table 2).

Fig. 7.

Zebrafish NBCe1-mediated Na+ transport. Intracellular Na+ activity (aNai) in oocytes injected with zebrafish NBCe1 or water. In zNBCe1 oocytes only, Nai increased with CO2/HCO3− addition and Vm hyperpolarized. Na removal in the presence of CO2/HCO3− reversed these effects. aNai is expressed in mM. Experimental protocol and text notations are as described for Fig. 5.

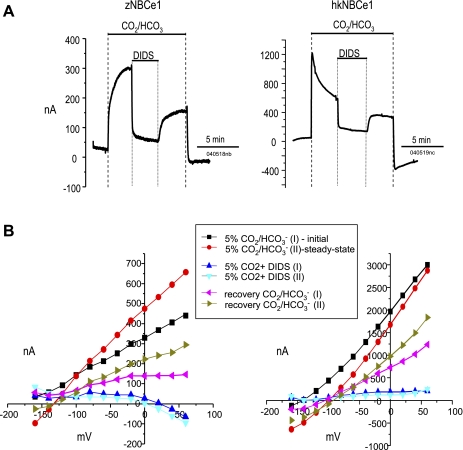

Zebrafish NBCe1 I-V relationship and inhibition.

We next evaluated the voltage dependence and inhibition of HCO3− elicited currents in zNBCe1-injected oocytes (Fig. 8). Like in hkNBCe1, HCO3−-elicited currents of zNBCe1 showed strong voltage dependence. The steady-state currents increased from the initial zNBCe1 currents as opposed to the relaxation of steady-state currents from the initial hkNBCe1 currents. This effect corresponded to the rounded waveform and slower developing current of zNBCe1. The reversal potential of zNBCe1 (−131.2 ± 3.4 mV, n = 6) was shifted negative compared with that of hkNBCe1 (−85.4 ± 4.4 mV, n = 6).

Fig. 8.

DIDS effect on NBCe1 current-voltage (I-V) relationship. Oocytes injected with zNBCe1 or hkNBCe1 and clamped at −60 mV. A: DIDS inhibition of the initial and steady-state CO2/HCO3− elicited currents are compared between hkNBCe1 and zebrafish NBCe1. Experimental protocol and text notations are as described for Fig. 5. Similar experiments were repeated at least 6 times. B: I-V relationships showing CO2/HCO3− elicited currents, DIDS inhibition, and recovery after DIDS removal. Voltage-step protocols were executed 30 s before solution changes and at the peak current after solution changes.

Addition of 200 μM DIDS immediately blocked ∼85% of the current elicited by CO2/HCO3− addition. The inhibition effects of DIDS on the HCO3− elicited currents were very similar for zNBCe1 and hkNBCe1. IDIDS of zNBCe1 showed slightly voltage dependent at the positive holding voltages, whereas IDIDS of hkNBCe1 was unaffected by voltage. In both cases the HCO3− elicited currents slowly and incompletely recovered after DIDS was removed.

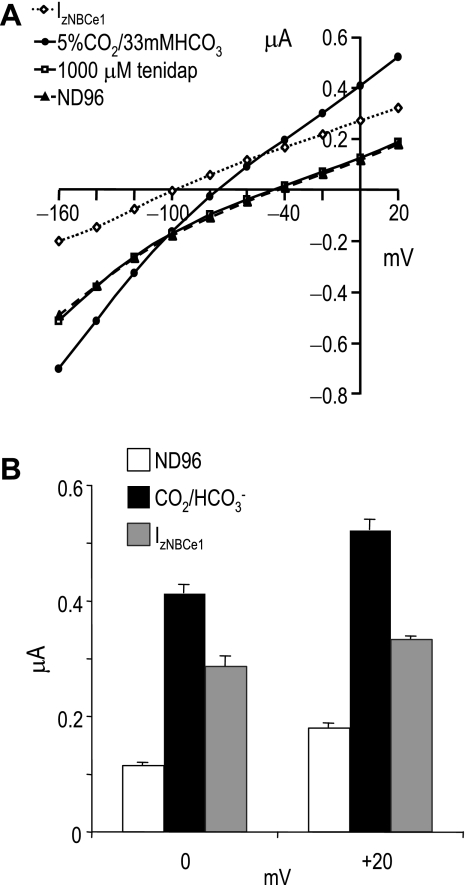

Addition of 1,000 μM tenidap (15, 28) blocked ∼100% of the current elicited by CO2/HCO3− (Fig. 9). The “pure INBCe1” is calculated as the difference between ICO2/HCO3− and Itenidap. This INBCe1 versus voltage yields a conductance of 3.0 ± 0.2 μS for zNBCe1. Removing tenidap from the solution returned the zNBCe1 I-V curve to almost the pre-CO2/HCO3− state (data not shown) as previously published for mammalian NBCe1 proteins (15, 28). These data demonstrated a mostly reversible binding of tenidap to zNBCe1 in contrast to DIDS (binding seems >95% reversible).

Fig. 9.

Tenidap effect on NBCe1 I-V relationship. A: I-V curves of oocytes injected with zebrafish NBCe1 in response to CO2/HCO3− addition and 1,000 μM tenidap. INBC = IHCO3−Itenidap. B: comparison of currents at 0 and +20 mV in response to CO2/HCO3− addition and 1,000 μM tenidap.

DISCUSSION

To explore the utility of the zebrafish model system for studies of NBCe1, we cloned and characterized zebrafish NBCe1 (zNBCe1) function at the molecular, tissue, and organism level. Morpholino and in situ data indicated that in zebrafish, as in mammals, the NBCe1 protein has roles in the eye, brain, kidney, and gill. Expression of zNBCe1 in Xenopus oocytes demonstrated that the molecular transport characteristics and inhibitor sensitivity of zNBCe1 are similar to that of mammalian NBCe1 orthologs.

Evolution of the slc4a4 gene.

The three mammalian isoforms of NBCe1 (A, B, and C) are generated from a single slc4a4 gene. The kidney form of NBCe1 (kNBCe1/NBCe1-A) arises from an alternative promoter in intron 3,4 (1). The second NBCe1 isoform (pNBCe1/NBCe1-B) replaces the first 41 amino acids of NBCe1-A with 85 amino acids at the NH2-terminus and is expressed in the pancreas (1), eye (35), heart (8), stomach (41), small intestine (2, 33), salivary glands (42), brain (3), and epididymis (25). A third NBCe1 isoform (rb2NBCe1/NBCe1-C) is expressed predominantly in brain, and is identical to NBCe1-B at the NH2-terminus but has a 97-bp deletion and frame shift at the 3′ end of the open reading frame (3). NBCe1-B and NBCe1-C isoforms have similar transport characteristics (29) but differ in magnitude from the kidney form NBCe1-A. Shirakabe and colleagues (46) found that coexpression of IP3 binding protein IRBIT with NBCe1-B activated this isoform to that of NBCe1-A.

Zebrafish NBCe1 is most similar to the mammalian NBCe1-B, the isoform with the longer NH2-terminus. This inference is indicated by both the zNBCe1 sequencing and RT-PCR results shown here (Fig. 1B). Attempts to PCR the complete putative NBCe1-A isoform from zebrafish kidney and other tissues failed. A more detailed analysis revealed that the genomic sequence in intron 3,4 of zebrafish slc4a4, which would be predicted to encode a NBCe1-A isoform, encodes a putative protein which is highly dissimilar to mammalian slc4a4, i.e., NBCe1-A. Moreover, there are no zebrafish ESTs corresponding to this putative zNBCe1-A, and this isoform has not to our knowledge been found in other teleosts (e.g., dace, trout, fugu, mefugu). We cannot, however, absolutely rule out the possibility that zNBCe1-A exists (as negative data do not constitute proof). The RT-PCR tissue results do indicate that the zNBCe1-B characterized in this paper is the dominant zNBCe1-isoform in all tissues where mammalian NBCe1-isoforms are found, including the kidney.

If the other NBCe1 isoforms are not present in teleosts, then unlike amphibians and mammals, zebrafish would appear to have only one NBCe1 isoform (NBCe1-B). Perhaps this means that the slc4a4 gene further evolved after the origin of teleosts to give rise to the “kidney” isoform (NBCe1-A) of amphibians and mammals and the “brain” isoform (NBCe1-C) present in mammals (1, 3). Zebrafish do apparently have at least one IRBIT-candidate (GenBank EST BI885096, 87% identical, 92% similar to mouse IRBIT), designated as a “putative adenosyl-homocysteinase.” Nevertheless, the the crucial phosphorylated serines in IRBIT required for activation (S68, S71, S74, S77) of Slc4a4-B (46) are not present in this zebrafish EST. There are additional zebrafish ESTs for “S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase-like 1,” but it is not clear whether any of these cDNA have these crucial serines or if they might similarly interact with zNBCe1-B. It is attractive to speculate that evolution of the non-IRBIT-regulated “kidney” isoform (NBCe1-A) present in amphibians and mammals coincides with life out of water and the need for urine concentration. If indeed zNBCe1-A is not made, we speculate that the ability to make a “NBCe1-A/non-IRBIT regulated Na+/nHCO3− cotransporter could be a critical adaptation aiding terrestrial survival by coupling water absorption to NaHCO3 absorption. This conjecture would require extensive study and genomic analysis of many teleost species (beyond this study) to begin addressing this evolutionary issue.

NBCe1 expression and tissue function.

Tissue expression and function of zebrafish NBCe1 is similar to that in other fish and mammals. The zebrafish NBCe1 transcript was detected in embryos in the retina, pronephros, gill, and brain ependymal cells lining the ventricles. The NBCe1 protein was detected in gill (likely Cl− cells as previously found in dace) (21), the retina in adults, and in the pronephros of embryos. NBCe1 expression in the gill, kidney, intestine, and liver has been described in freshwater fish such as dace and rainbow trout (21, 31, 32), in the gill of the marine fish, benthic eelpout (Zoarces viviparous) (10), and in the intestine of the euryhaline pufferfish mefugu (Takifugu obscurus) (26).

The gill is believed to possess a mechanism for preventing metabolic acidosis and alkalosis (9, 20, 21). By analogy with mammalian systems, NBCe1 in the fish kidney probably plays a role in tubular reabsorption of Na+ and HCO3−. It is highly likely that systemic acid-base balance is accomplished by the kidney and gills working together in fish. The follicular pattern of NBCe1 labeling in the zebrafish gill resembles that of NBCe1 labeling in gill of dace. In dace the NBCe1-positive cells expressed additional markers of chloride cells, implying that in zebrafish like dace, the NBCe1-positive cells in the gill are chloride cells (21). A function for NBCe1 in pH and osmotic homeostasis in zebrafish gill is consistent with observations in freshwater and saltwater fish in adaptation to increased water osmolarity and reduced pH (21, 26, 32).

NBCe1 expression in the brain and eye has been observed in the salamander, rat, mouse, and human (3, 4, 18, 34, 38). NBCe1 function in the eye is implied by particulate deposition behind the retinal pigmented epithelium observed in NBCe1 morphants (Fig. 4, E and F). In the normal zebrafish eye, zNBCe1 protein is observed in both the lens surface (Fig. 3I) as well as the retinal ganglion layer and photoreceptor layer (Fig. 3J). Similar placement of NBCe1 protein is reported in rat and humans eyes (4, 11, 12, 22, 23). Physiologically, NBCe1 function is critical for the human lens in that NBCe1 mutations cause cataracts (11, 12, 22, 23). Similarly, NBCe1 function is critical for either ocular fluid balance or retinal health because mutations in human NBCe1 (SLC4A4) are causative of glaucoma (11, 12, 22, 23). Interestingly, NBCe1 (SLC4A4) is one of the 8–10 genes that cause glaucoma (as reported by the NIH/NEI website).

The role of zNBCe1 in hydrocephalus (as a result of knockdown) is less clear. NBCe1 labeling in the zebrafish brain at 72 hpf was clearly in the ventricular zones of the central canal and midbrain ventricle (Fig. 2) as found in mammals, i.e., in the choroid plexus and in ependymal cells (3). This labeling may also include choroid plexus based on its temporal and spatial coincidence with choroid plexus development in zebrafish (16).

These data raise the possibility that NBCe1 might be involved in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) elaboration by the choroid plexus. However, this hypothesis does not seem to be supported by the NBCe1 knockout mice generated by Gary Shull's group (17) as there are no overt signs of hydrocephalus in Slc4a4-deficient mice. On the other hand, Slc4a10 in mice has been implicated in the elaboration of CSF (24). However, in this case, the Slc4a10 knockout mouse shows a reduction in the size of the brain ventricles, as opposed to the expansion we observed. Thus it seems unlikely that zNBCe1 loss of function would result in increased CSF secretion leading to hydrocephalus. Similarly, if NBCe1 is involved in CSF elaboration, we would also expect reduced ventricle size rather than hydrocephalus.

Alternatively, zNBCe1 may be involved in fluid absorption from the CSF to the brain parenchyma. This interpretation is supported by the observation that zNBCe1 expression is not restricted to the relatively small group of cells comprising the zebrafish choroid plexus in the fourth ventricle but rather is expressed broadly in all cells lining the brain ventricles (Fig. 2) (16). Little is known about how fluid and electrolytes are absorbed from CSF (6). Nonetheless, failure of fluid and electrolyte uptake into the brain parenchyma could conceivably result in fluid backup and swelling of the brain ventricles.

Another potential mechanism for hydrocephalus in zNBCe1 knockdown embryos might be that zNBCe1 is required for ionic regulation and cell survival in metabolically active cells of the brain ventricular lining (27). Cell death and deposition of debris in the ventricles could obstruct CSF efflux. Whereas we did observe debris in the brain ventricles, we did not observe significant cell death in brain parenchyma lining the ventricles, making this possibility less likely. The nature of precipitated material in the zebrafish ventricles has not been characterized and will require further study. Currently there is little known about the composition and physiology of teleost CSF. Future studies examining the secretion and uptake of CSF in the zebrafish brain could provide a useful model for this important process.

In zebrafish, NBCe1 mRNA expression in the pronephric ducts changed between 18 and 72 hpf, becoming more proximally restricted with time. This change may reflect regionalization into distinct tubule domains with maturation. The anatomy of the zebrafish pronephros is similar to the mammalian nephron with respect to proximal and distal tubule domains as indicated by expression of characteristic transport proteins (30, 49). Thus development of a more proximal-limited expression domain for NBCe1 in the zebrafish pronephros is consistent with the predominantly proximal expression of NBCe1 in the mammalian kidney (36). As with expression in dace gill, NBCe1 expression in the zebrafish gill is consistent with NBCe1 function that has been observed in freshwater and saltwater fish in adaptation to increased water osmolarity and decreased pH (21, 26, 32). NBCe1 is critical for systemic acid-base homeostasis. Patients with NBCe1 recessive mutations have a proximal renal tubular acidosis (pRTA) (11, 12, 22, 23) and NBCe1 knockout mice (17) demonstrate a severe metabolic acidosis.

Transport characteristics of zebrafish NBCe1.

Molecular transport properties of zebrafish NBCe1 are consistent with roles hypothesized above in acid-base and osmotic homeostasis. Like NBCe1 in other teleosts, amphibians, and mammals, zebrafish demonstrated cotransport of Na+ and HCO3−, sensitivity to the stilbene inhibitor DIDS and electrogenicity (26, 31, 38). Not only was the zebrafish NBCe1 sequence most similar to the mammalian pancreatic form, but also transport characteristics most closely resembled the mammalian pancreatic isoform of NBCe1 (NBCe1-B) (29). That is, both have a slow developing, rounded waveform and markedly smaller current elicited by CO2/HCO3−.

These initial studies characterizing zNBCe1 expression and function demonstrate striking similarities to comparable studies of mammals, including humans. These studies indicate the validity of utilizing the tremendous versatility of the zebrafish model system to advance our understanding of the physiology and pathophysiology of NBCe1.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

A zebrafish ion transport review highlighting NBCe1 was published by Hwang, PP (J Exp Biol 212: 1745–1752, 2009).

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-56218, DK-60845, and EY-017732 (to M. F. Romero), DK-30344 (to W. F. Boron), DK-070263 (to I. A. Drummond), Wadsworth Foundation New Investigator Award and American Heart Association (AHA) SDG 06-30137N (to C. R. Sussman), PKD foundation fellowship 38a2f (to J. Zhao), and AHA postdoctoral fellowships (to M.-H. Chang and J. Lu).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Shigehisa Hirose (Biological Sciences, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Yokohama 226-8501, Japan) for kindly providing Dace-NBCe1 antibody. We thank Montelle Sanders and Gerald Babcock for excellent technical support, and Zara Josephs for initial in situs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abuladze N, Song M, Pushkin A, Newman D, Lee I, Nicholas S, Kurtz I. Structural organization of the human NBC1 gene: kNBC1 is transcribed from an alternative promoter in intron 3. Gene 251: 109–122, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmann O, Rossmann H, Berger UV, Colledge WH, Ratcliff R, Evans MJ, Gregor M, Seidler U. cAMP-mediated regulation of murine intestinal/pancreatic Na+/HCO3−cotransporter subtype pNBC1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 284: G37–G45, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bevensee MO, Schmitt BM, Choi I, Romero MF, Boron WF. An electrogenic Na/HCO3 cotransporter (NBC) with a novel C terminus, cloned from rat brain. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278: C1200–C1211, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bok D, Schibler MJ, Pushkin A, Sassani P, Abuladze N, Naser Z, Kurtz I. Immunolocalization of electrogenic sodium-bicarbonate cotransporters pNBC1 and kNBC1 in the rat eye. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F920–F935, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boron WF, Boulpaep EL. Intracellular pH regulation in the renal proximal tubule of the salamander. Basolateral HCO3− transport. J Gen Physiol 81: 53–94, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulat M, Lupret V, Orehkovic D, Klarica M. Transventricular and transpial absorption of cerebrospinal fluid into cerebral microvessels. Collegium Antropologicum 32, >Suppl 1: 43–50, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang MH, DiPiero J, Sonnichsen FD, Romero MF. Entry to “HCO3− tunnel” revealed by SLC4A4 human mutation and structural model. J Biol Chem 283: 18402–18410, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi I, Romero MF, Khandoudi N, Bril A, Boron WF. Cloning and characterization of a human electrogenic Na+-HCO3− cotransporter isoform (hhNBC). Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 276: C576–C584, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claiborne JB, Edwards SL, and Morrison-Shetlar AI. Acid-base regulation in fishes: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Exp Zool 293: 302–319, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deigweiher K, Koschnick N, Portner HO, Lucassen M. Acclimation of ion regulatory capacities in gills of marine fish under environmental hypercapnia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1660–R1670, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demirci FY, Chang MH, Mah TS, Romero MF, Gorin MB. Proximal renal tubular acidosis and ocular pathology: a novel missense mutation in the gene (SLC4A4) for sodium bicarbonate cotransporter protein (NBCe1). Mol Vis 12: 324–330, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinour D, Chang MH, Satoh J, Smith BL, Angle N, Knecht A, Serban I, Holtzman EJ, Romero MF. A novel missense mutation in the sodium bicarbonate cotransporter (NBCe1/SLC4A4) causes proximal tubular acidosis and glaucoma through ion transport defects. J Biol Chem 279: 52238–52246, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drummond IA. Kidney development and disease in the zebrafish. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 299–304, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drummond IA, Majumdar A, Hentschel H, Elger M, Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, Neuhauss SC, Stemple DL, Zwartkruis F, Rangini Z, Driever W, Fishman MC. Early development of the zebrafish pronephros and analysis of mutations affecting pronephric function. Development 125: 4655–4667, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ducoudret O, Diakov A, Muller-Berger S, Romero MF, Fromter E. The renal Na-HCO3−cotransporter expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes: inhibition by tenidap and benzamil and effect of temperature on transport rate and stoichiometry. Pflügers Arch 442: 709–717, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Lecea M, Kondrychyn I, Fong SH, Ye ZR, Korzh V. In vivo analysis of choroid plexus morphogenesis in zebrafish. PloS one 3: e3090, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gawenis LR, Bradford EM, Prasad V, Lorenz JN, Simpson JE, Clarke LL, Woo AL, Grisham C, Sanford LP, Doetschman T, Miller ML, Shull GE. Colonic anion secretory defects and metabolic acidosis in mice lacking the NBC1 Na+/HCO3− cotransporter. J Biol Chem 282: 9042–9052, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giffard RG, Papadopoulos MC, van Hooft JA, Xu L, Giuffrida R, Monyer H. The electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter: developmental expression in rat brain and possible role in acid vulnerability. J Neurosci 20: 1001–1008, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goessling W, North TE, Zon LI. Ultrasound biomicroscopy permits in vivo characterization of zebrafish liver tumors. Nat Methods 4: 551–553, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goss GG, Laurent P, Perry SF. Evidence for a morphological component in acid-base regulation during environmental hypercapnia in the brown bullhead (Ictalurus nebulosus). Cell Tissue Res 268: 539–552, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirata T, Kaneko T, Ono T, Nakazato T, Furukawa N, Hasegawa S, Wakabayashi S, Shigekawa M, Chang MH, Romero MF, Hirose S. Mechanism of acid adaptation of a fish living in a pH 3.5 lake. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 284: R1199–R1212, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Igarashi T, Inatomi J, Sekine T, Seki G, Shimadzu M, Tozawa F, Takeshima Y, Takumi T, Takahashi T, Yoshikawa N, Nakamura H, Endou H. Novel nonsense mutation in the Na+/HCO3− cotransporter gene (SLC4A4) in a patient with permanent isolated proximal renal tubular acidosis and bilateral glaucoma. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 713–718, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Igarashi T, Sekine T, Inatomi J, Seki G. Unraveling the molecular pathogenesis of isolated proximal renal tubular acidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2171–2177, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs S, Ruusuvuori E, Sipila ST, Haapanen A, Damkier HH, Kurth I, Hentschke M, Schweizer M, Rudhard Y, Laatikainen LM, Tyynela J, Praetorius J, Voipio J, Hubner CA. Mice with targeted Slc4a10 gene disruption have small brain ventricles and show reduced neuronal excitability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 311–316, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen LJ, Schmitt BM, Berger UV, Nsumu NN, Boron WF, Hediger MA, Brown D, Breton S. Localization of sodium bicarbonate cotransporter (NBC) protein and messenger ribonucleic acid in rat epididymis. Biol Reprod 60: 573–579, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurita Y, Nakada T, Kato A, Doi H, Mistry AC, Chang MH, Romero MF, Hirose S. Identification of intestinal bicarbonate transporters involved in formation of carbonate precipitates to stimulate water absorption in marine teleost fish. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1402–R1412, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowery LA, Sive H. Initial formation of zebrafish brain ventricles occurs independently of circulation and requires the nagie oko and snakehead/atp1a1a.1 gene products. Development 132: 2057–2067, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu J, Boron WF. Reversible and irreversible interactions of DIDS with the human electrogenic Na/HCO3 cotransporter NBCe1-A: role of lysines in the KKMIK motif of TM5. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C1787–C1798, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McAlear SD, Liu X, Williams JB, McNicholas-Bevensee CM, Bevensee MO. Electrogenic Na/HCO3 cotransporter (NBCe1) variants expressed in Xenopus oocytes: functional comparison and roles of the amino and carboxy termini. J Gen Physiol 127: 639–658, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichane M, Van Campenhout C, Pendeville H, Voz ML, Bellefroid EJ. The Na+/PO4 cotransporter SLC20A1 gene labels distinct restricted subdomains of the developing pronephros in Xenopus and zebrafish embryos. Gene Expr Patterns 6: 667–672, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parks SK, Tresguerres M, Goss GG. Interactions between Na+ channels and Na+-HCO3− cotransporters in the freshwater fish gill MR cell: a model for transepithelial Na+ uptake. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C935–C944, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry SF, Furimsky M, Bayaa M, Georgalis T, Shahsavarani A, Nickerson JG, Moon TW. Integrated responses of Na+/HCO3− cotransporters and V-type H+-ATPases in the fish gill and kidney during respiratory acidosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1618: 175–184, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Praetorius J, Hager H, Nielsen S, Aalkjaer C, Friis UG, Ainsworth MA, Johansen T. Molecular and functional evidence for electrogenic and electroneutral Na+-HCO3− cotransporters in murine duodenum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G332–G343, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rickmann M, Orlowski B, Heupel K, Roussa E. Distinct expression and subcellular localization patterns of Na+/HCO3− cotransporter (Slc 4a4) variants NBCe1-A and NBCe1-B in mouse brain. Neuroscience 146: 1220–1231, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romero MF. The electrogenic Na+/HCO3− cotransporter, NBC. Jop 2: 182–191, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romero MF, Chang MH, Plata C, Zandi-Nejad K, Mercado A, Broumand V, Sussman CR, Mount DB. Physiology of electrogenic SLC26 paralogues. Novartis Found Symp 273: 126–138; discussion 138–147, 261–124, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romero MF, Fong P, Berger UV, Hediger MA, Boron WF. Cloning and functional expression of rNBC, an electrogenic Na+-HCO3− cotransporter from rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F425–F432, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romero MF, Hediger MA, Boulpaep EL, Boron WF. Expression cloning and characterization of a renal electrogenic Na+/HCO3− cotransporter. Nature 387: 409–413, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romero MF, Henry D, Nelson S, Harte PJ, Sciortino CM. Cloning and characterization of a Na+ driven anion exchanger (NDAE1): a new CNS bicarbonate transporter. J Biol Chem 275: 24552–24559, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roos A, Boron WF. Intracellular pH. Physiol Rev 61: 296–434, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rossmann H, Bachmann O, Vieillard-Baron D, Gregor M, Seidler U. Na+/HCO3− cotransport and expression of NBC1 and NBC2 in rabbit gastric parietal and mucous cells. Gastroenterology 116: 1389–1398, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roussa E, Romero MF, Schmitt BM, Boron WF, Alper SL, Thevenod F. Immunolocalization of anion exchanger AE2 and Na+-HCO3− cotransporter in rat parotid and submandibular glands. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 277: G1288–G1296, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmitt BM, Biemesderfer D, Romero MF, Boulpaep EL, Boron WF. Immunolocalization of the electrogenic Na+-HCO3− cotransporter in mammalian and amphibian kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F27–F38, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sciortino CM, Romero MF. Cation and voltage dependence of rat kidney electrogenic Na+-HCO3− cotransporter, rkNBC, expressed in oocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F611–F623, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sciortino CM, Shrode LD, Fletcher BR, Harte PJ, Romero MF. Localization of endogenous and recombinant Na+-driven anion exchanger protein NDAE1 from Drosophila melanogaster. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C449–C463, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shirakabe K, Priori G, Yamada H, Ando H, Horita S, Fujita T, Fujimoto I, Mizutani A, Seki G, Mikoshiba K. IRBIT, an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-binding protein, specifically binds to and activates pancreas-type Na+/HCO3− cotransporter 1 (pNBC1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 9542–9547, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thisse C, Thisse B. High resolution whole-mount in situ hybridization The Zebrafish Science Monitor: ZFIN; the Zebrafish International Resource Center, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403-5274; World Wide Web URL: http://zfinorg pp 8–9, 1998

- 48.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book (4th ed). Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wingert RA, Selleck R, Yu J, Song HD, Chen Z, Song A, Zhou Y, Thisse B, Thisse C, McMahon AP, Davidson AJ. The cdx genes and retinoic acid control the positioning and segmentation of the zebrafish pronephros. PLoS Genet 3: 1922–1938, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie Q, Welch R, Mercado A, Romero MF, Mount DB. Molecular characterization of the murine Slc26a6 anion exchanger: functional comparison with Slc26a1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F826–F838, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]