Abstract

Purpose

The objectives of this study were to: 1) investigate the association between lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and chronic illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, and depression in men and women, and 2) to determine whether a dose-response relationship exists in the association between the severity and duration of urologic symptoms and major chronic illnesses.

Materials and Methods

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey used a multistage stratified design to recruit a random sample of 5,503 adults age 30-79. Urologic symptoms comprising the American Urological Association symptom index were included in the analysis.

Results

Statistically significant associations, consistent by gender, were observed between depression and all urologic symptoms. Nocturia of any degree of severity or duration was associated with heart disease among men and with diabetes among women. Among men, a dose-response relationship was observed in the association of symptom severity and/or duration of urinary intermittency and frequency with heart disease, and in the association of urinary urgency with diabetes. Among women, a history of heart disease was associated with weak stream and straining, while a history of hypertension was associated with urgency and weak stream.

Conclusions

Results indicate a dose-response relationship in the association of both severity and duration of urologic symptoms with major chronic illnesses. An association between urinary symptoms and depression was observed in both men and women. In contrast, the association between LUTS and heart disease, diabetes, or hypertension varied by gender, suggesting different mechanisms of association in men and women.

Keywords: lower urinary tract symptoms, heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, depression

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are common in both aging women and men and their prevalence increases with age.1 There is evidence from both clinical and epidemiological studies showing associations between LUTS and lifestyle risk factors and related comorbid conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and depression.2-6 Results of these studies support the hypothesis that factors outside the urinary tract contribute to urologic symptoms – the so-called “beyond the bladder” hypothesis.3 The contribution of individual symptoms, and potential dose effects of increasing number and/or severity of urologic symptoms has not been systematically investigated. Such a dose-response relationship between increased severity and duration of urologic symptoms and increased odds of comorbid conditions would provide additional evidence in support of the hypothesized link between LUTS and chronic illnesses.

Using data from the BACH survey, the purpose of this study was to investigate the association between chronic illnesses (including heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, and depression) and seven specific urologic symptoms (urgency, frequency, nocturia, incomplete emptying, straining, weak stream, intermittency), comprising the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI), in a representative, population-based sample of men and women. The objectives of this analysis were: 1) investigate the association between LUTS and chronic illnesses in age-appropriate samples of men and women, and 2) to determine whether a dose-response relationship exists in the association between severity and duration of urologic symptoms and chronic illnesses.

Materials and Methods

Overall Design

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey is a population-based epidemiologic survey of a broad range of urologic symptoms and risk factors among randomly selected men and women. Detailed methods have been described elsewhere.7 A multi-stage stratified design was used to recruit approximately equal numbers of subjects according to age (30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-79), gender, and race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, and White). The BACH sample was recruited from April 2002 through June 2005. Interviews were completed with 63.3% of eligible subjects, in a total sample of 5503 adults (2301 men, 3202 women, 1767 Black, 1877 Hispanic, 1859 White respondents). All protocols and informed consent procedures were approved by the New England Research Institutes Institutional Review Board.

Following written informed consent, data were obtained during a 2-hour in-person interview, conducted by a trained (bilingual) phlebotomist/interviewer. Height, weight, hip and waist circumference were measured along with self-reported information on medical and reproductive history, major comorbidities, lifestyle and psychosocial factors, and symptoms of urogynecological conditions.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)

LUTS were assessed using the American Urological Symptom Index (AUA-SI), a clinically validated measure of urological symptoms with a validated and reliable Spanish version.8, 9 The AUA-SI was categorized as 0-7 (none or mild symptoms), 8-19 (moderate symptoms) and 20-35 (severe) and also dichotomozied as <8 versus ≥8. Using a similar approach, frequency of report was used as an indicator of severity of individual symptoms and grouped into two categories, mild (symptom experienced rarely or sometimes) versus moderate or severe (symptom experienced fairly often, usually, or almost always) and compared to the no symptom group. Duration of each symptom was assessed as <3 months, 3 to 6 months, 6 to 12 months, 1 to 5 yrs, and 6+ years. For purposes of this analysis, duration was categorized as <1 year versus ≥1 year, with the no symptom group as the reference group.

Chronic illnesses

Four major comorbid conditions were considered in this analysis: heart disease, type 2 diabetes (T2DM), hypertension, and depression. The presence of comorbidities was defined as a yes response to “Have you ever been told by a health care provider that you have or had....”? Heart disease was defined by self-report of myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure, coronary artery bypass, or angioplasty stent. Participants reporting five or more depressive symptoms (out of 8) using the abbreviated Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression (CES-D) scale were considered to have clinically significant depression.10

Additional covariates

Age was categorized by decade: 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, and 70-79 years. Self reported race/ethnicity was defined as Black, Hispanic, or White. Body mass index (BMI) was categorized as <25, 25-29, and 30+ kg/m2. Physical activity was measured using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) and was categorized as low (<100), medium (100-250), and high (>250).11 Alcohol consumption was defined as alcoholic drinks consumed per day: 0, <1, 1-3, 3+ drinks per day. Smoking was defined as never smokers, former smokers, and current smoker. The socioeconomic status (SES) index was calculated using a combination of education and household income.12 SES was categorized as low (lower 25% of the distribution of the SES index), middle (middle 50% of the distribution), and high (upper 25% of the distribution).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted separately for men and women. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), estimated using multiple logistic regression, were used to assess the association of urologic symptoms and chronic illnesses. Initially, severity and duration of symptoms were combined into a five-level variable: no symptoms, mild symptoms with <1 year duration, mild symptoms with ≥1 year duration, severe symptoms with <1 year duration, and severe symptoms with ≥1 year duration. However, this approach was not feasible due to small cell sizes in the cross-tabulation of this five-level variable with chronic illnesses by gender. Therefore, results from separate models for severity (severe and mild symptoms compared to the no symptom group) and duration (<1 year and ≥1 year duration compared to the no symptom group) are presented, in addition to the subject group expected to be at highest risk, i.e. participants reporting severe symptoms for ≥1 year.

A multiple imputation technique was used to obtain plausible values for missing data.13 The proportion of participants with missing data was 0.6% (30 participants) for the AUA-SI, 1.1% (60 subjects) for comorbid conditions and depressive symptoms, 0.9% (37 subjects) for lifestyle variables, and 6.1% for SES, with a combined rate of 8.0% (442 participants) for missing at least one of these variable. Twenty-five multiple imputations were performed separately by gender and race/ethnicity using all relevant variables. To be representative of the city of Boston, observations were weighted inversely proportional to their probability of selection. Weights were post-stratified to the Boston population according to the 2000 census. Analyses were conducted in version 9.1 of SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and version 9.0.1 of SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA).

Results

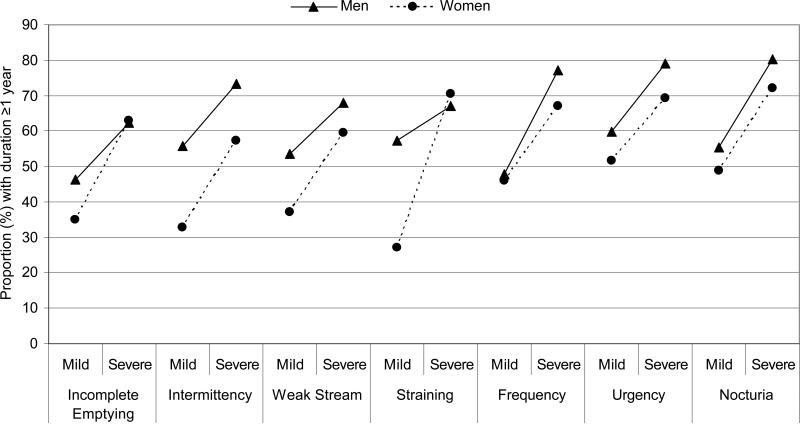

Characteristics of the 2,301 men and 3,202 women and prevalence of the four chronic illnesses are presented in Table 1. Prevalence of heart disease was slightly higher among men (10.2%) compared to women (7.9%) (χ2 p-value = 0.051), while the prevalence of T2DM and hypertension did not differ by gender. In contrast, the prevalence of depression was significantly higher among women (20.1%) compared to men (14.0%) (χ2 p-value for comparison by gender <0.001). Obesity (BMI≥30 kg/m2) was more common among women (38.1% versus 32.7%, χ2 p-value <0.001), while reports of any alcohol consumption were higher among men (72.5%) compared to women (58.3%) (χ2 p-value <0.001). A statistically significant, positive association was observed between severity and duration for all seven LUTS symptoms among both men and women (Figure 1). The proportion of men and women reporting symptom duration ≥1 year was consistenly higher among those with severe symptoms compared to those with mild symptoms.

Table1.

Characteristics of the analysis sample overall and by gender. N (weighted percentages)

| Overall | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 30-39 | 1407 (35.2) | 615 (37.2) | 792 (33.5) |

| 40-49 | 1498 (25.1) | 659 (25.8) | 839 (24.4) | |

| 50-59 | 1287 (18.1) | 510 (17.8) | 777 (18.4) | |

| 60-69 | 845 (13.3) | 329 (11.3) | 516 (15.1) | |

| 70-79 | 466 ( 8.2) | 188 ( 7.8) | 278 ( 8.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 1859 (59.2) | 835 (61.9) | 1024 (56.8) |

| Black | 1767 (27.6) | 700 (25.1) | 1067 (29.9) | |

| Hispanic | 1877 (13.2) | 766 (13.0) | 1111 (13.3) | |

| Socioeconomic Status (SES) | Low | 2568 (27.8) | 970 (24.3) | 1598 (31.0) |

| Middle | 2149 (47.0) | 953 (49.0) | 1197 (45.1) | |

| High | 786 (25.2) | 378 (26.7) | 408 (23.9) | |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | <25.0 | 1348 (30.1) | 595 (26.6) | 753 (33.3) |

| 25.0-29.9 | 1876 (34.3) | 904 (40.7) | 972 (28.6) | |

| ≥30 | 2277 (35.5) | 800 (32.7) | 1476 (38.1) | |

| Physical Activity (PASE) | Low (<100) | 1885 (27.3) | 694 (26.8) | 1191 (27.8) |

| Moderate (200-250) | 2645 (50.7) | 1069 (47.4) | 1576 (53.6) | |

| High(>250) | 971 (22.0) | 537 (25.8) | 434 (18.5) | |

| Smoking | Never | 2667 (47.8) | 963 (45.1) | 1703 (50.2) |

| Former | 1438 (27.9) | 662 (28.7) | 776 (27.2) | |

| Current | 1397 (24.3) | 675 (26.2) | 721 (22.6) | |

| Alcohol consumption (drinks per day) | None | 2460 (34.9) | 799 (27.5) | 1660 (41.7) |

| <1/day | 2024 (41.2) | 815 (38.9) | 1209 (43.2) | |

| 1-2.9/day | 701 (18.2) | 433 (24.0) | 268 (12.9) | |

| ≥3/day | 316 ( 5.7) | 252 ( 9.6) | 64 ( 2.2) | |

| Heart disease | 551 ( 9.0) | 248 (10.2) | 303 ( 7.9) | |

| Type 2 diabetes | 609 ( 7.9) | 247 ( 8.0) | 362 ( 7.8) | |

| Hypertension | 1860 (27.3) | 735 (26.2) | 1125 (28.3) | |

| Depression | 1221 (17.2) | 391 (14.0) | 830 (20.1) | |

| AUA-SI* | 0-7 (Mild) | 4383 (81.3) | 1860 (81.3) | 2523 (81.4) |

| 8-19 (Moderate) | 988 (17.1) | 395 (17.3) | 593 (16.8) | |

| 20-35 (Severe) | 132 ( 1.6) | 46 ( 1.4) | 86 ( 1.8) |

American Urological Association Symptom Index

Figure 1.

Symptom severity is associated with duration of symptoms among both men and women. The proportion reporting symptom duration of ≥1 year is significantly higher among those with severe symptoms compared to those with mild symptoms (all χ2 p-values <0.05 for comparison by symptom severity).

The relationship between LUTS, assessed by the AUA-SI, and chronic illnesses is presented in Table 2. A statistically significant association between LUTS and both heart disease and depression was consistent by gender with a trend in increasing ORs with increased severity of the AUA-SI. A similar trend was observed between the odds of diabetes and the AUA-SI among men but was not observed among women. While no association was observed between LUTS and hypertension in men, a significant trend in increased odds with higher AUA-SI was observed among women.

Table 2.

Association of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) with chronic illnesses by gender. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

| Men |

Women |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Illnesses | AUA-SI* | N cases (weighted %) | Adjusted**OR (95%CI) | N cases (weighted %) | Adjusted OR**(95%CI) | ||

| Heart | 0-7 (Mild) | 147 ( 7.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 185 (6.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Disease | 8-19 (Moderate) | 83 (19.7) | 1.74 (1.03, 2.96) | 1.80† (1.09, 2.96) | 92 (12.2) | 1.36 (0.85, 2.18) | 1.57† (1.02, 2.42) |

| 20-35 (Severe) | 18 (33.6) | 2.46 (1.04, 5.81) | 27 (35.4) | 3.48 (1.58, 7.68) | |||

| p-trend‡ | 0.011 | 0.007 | |||||

| Type 2 | 0-7 (Mild) | 163 (6.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 246 (6.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | 8-19 (Moderate) | 73 (6.1) | 1.92 (1.05, 3.52) | 2.00† (1.12, 3.56) | 97 (12.4) | 1.24 (0.80, 1.92) | 1.29† (0.85, 1.95) |

| 20-35 (Severe) | 12 (25.3) | 2.52 (0.73, 8.69) | 19 (22.5) | 1.64 (0.63, 4.31) | |||

| p-trend‡ | 0.016 | 0.189 | |||||

| Hypertension | 0-7 (Mild) | 537 (23.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 804 (25.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8-19 (Moderate) | 172 (38.7) | 1.32 (0.85, 2.06) | 1.30† (0.84, 2.00) | 270 (37.4) | 1.16 (0.81, 1.67) | 1.27† (0.91, 1.77) | |

| 20-35 (Severe) | 26 (48.6) | 1.16 (0.41, 3.26) | 51 (65.3) | 2.82 (1.39, 5.73) | |||

| p-trend‡ | 0.249 | 0.042 | |||||

| Depression | 0-7 (Mild) | 244 (10.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 566 (17.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8-19 (Moderate) | 124 (26.5) | 3.26 (2.09, 5.10) | 3.49† (2.29, 5.32) | 211 (30.4) | 1.92 (1.36, 2.71) | 2.11† (1.53, 2.90) | |

| 20-35 (Severe) | 23 (50.3) | 7.41 (2.54, 21.64) | 53 (59.5) | 4.52 (2.31, 8.86) | |||

| p-trend‡ | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

American Urological Association Symptom Index

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, BMI, physical activity, smoking alcohol consumption, comorbid conditions

OR for the 8-19 and 20-35 categories combined compared to the 0-7 category

p-value for trend across the 3 AUA-SI categories

The association observed between the AUA-SI and depression was confirmed when investigating each symptom individually (Table 3). A dose-response pattern of increased odds of depression with increased severity, but not duration, of each of the symptoms was consistent by gender. Although the magnitude of the ORs for severe symptoms were somewhat higher among men (ORs 2.3 to 7.3) compared to women (ORs 1.6 to 4.2), the associations were significant in both genders. In contrast, the pattern of associations between LUTS and heart disease, T2DM, and hypertension varied by gender (Table 4). Among men, nocturia of any degree of severity (mild or severe) or an increased duration of nocturia (≥1 year) were significantly associated with increased odds of heart disease. This pattern was especially evident in the highest risk group (severe symptoms for ≥1 year), with an almost two-fold increase in the odds of heart disease (OR=1.88, 95%CI: 1.00, 3.51). Increased odds of heart disease was also observed with increased severity and duration of urinary frequency (OR=2.15, 95%CI: 1.13, 4.12) and intermittency (OR=3.17. 95%CI: 1.31. 7.67). Among women, increased severity of weak stream or urgency were significantly associated with two- to three-fold increase increased odds of heart disease. While neither increased severity or duration of straining were significantly associated with heart disease individually, women reporting both of these symptoms were at three-fold increased odds of heart disease (OR=2.98, 95%CI: 1.23, 7.21).

Table 3.

Association of urologic symptoms and depression (depressive symptoms assessed by CES-D). Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, BMI, smoking alcohol consumption, physical activity, and prevalent comorbid conditions (heart disease, diabetes, hypertension) with the no symptom group as the reference category. Statistically significant ORs are in bold.

| No Symptom | Symptom Severity |

Symptom Duration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Mild* | Severe** | <1year | >1year | Severe >1 year | |

| Incomplete Emptying | 1.00 | 1.84 (1.23, 2.74) | 7.27 (3.58, 14.76) | 2.49 (1.50, 4.14) | 2.69 (1.47, 4.91) | 8.37 (3.40, 20.63) |

| Intermittency | 1.00 | 3.24 (1.85, 5.67) | 3.03 (1.60, 5.73) | 4.61 (2.65, 8.02) | 2.36 (1.36, 4.09) | 2.49 (1.17, 5.28) |

| Weak Stream | 1.00 | 2.08 (1.28, 3.38) | 2.81 (1.17, 6.72) | 3.31 (1.80, 6.10) | 1.61 (0.93, 2.78) | 1.44 (0.65, 3.19) |

| Straining | 1.00 | 1.82 (1.13, 2.92) | 7.21 (2.90, 17.97) | 3.65 (1.89, 7.04) | 2.06 (1.18, 3.6) | 3.71 (1.37, 10.05) |

| Frequency | 1.00 | 1.36 (0.82, 2.24) | 2.34 (1.36, 4.05) | 1.75 (1.00, 3.06) | 1.58 (0.94, 2.64) | 1.86 (1.04, 3.32) |

| Urgency | 1.00 | 1.34 (0.78, 2.29) | 2.73 (1.51, 4.92) | 1.95 (0.93, 4.10) | 1.52 (0.94, 2.45) | 2.88 (1.47, 5.66) |

| Nocturia | 1.00 | 2.49 (1.50, 4.14) | 2.69 (1.47, 4.91) | 2.48 (1.35, 4.54) | 2.68 (1.56, 4.59) | 4.19 (2.14, 8.21) |

|

Women | ||||||

| Incomplete Emptying | 1.00 | 1.62 (1.15, 2.29) | 1.85 (1.14, 2.99) | 1.72 (1.21, 2.44) | 1.60 (1.00, 2.56) | 1.53 (0.85, 2.76) |

| Intermittency | 1.00 | 1.56 (1.04, 2.35) | 1.91 (1.17, 3.11) | 1.45 (0.97, 2.15) | 2.03 (1.20, 3.46) | 1.71 (1.07, 2.75) |

| Weak Stream | 1.00 | 2.27 (1.45, 3.56) | 2.23 (1.29, 3.85) | 2.57 (1.57, 4.23) | 1.87 (1.12, 3.14) | 2.52 (1.29, 4.93) |

| Straining | 1.00 | 2.15 (1.26, 3.66) | 4.19 (2.05, 8.53) | 3.06 (1.72, 5.41) | 1.93 (1.10, 3.37) | 2.41 (1.11, 5.23) |

| Frequency | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.69, 1.33) | 1.57 (1.09, 2.28) | 1.49 (1.05, 2.10) | 0.97 (0.67, 1.41) | 1.17 (0.76, 1.79) |

| Urgency | 1.00 | 1.38 (0.93, 2.06) | 2.57 (1.63, 4.04) | 1.83 (1.16, 2.88) | 1.70 (1.15, 2.53) | 2.31 (1.45, 3.70) |

| Nocturia | 1.00 | 1.43 (1.02, 2.01) | 2.13 (1.37, 3.33) | 1.61 (1.10, 2.37) | 1.73 (1.20, 2.51) | 1.87 (1.14, 3.05) |

Mild = rarely/some of the time

Severe = often/most of the time/always

Table 4.

Urologic symptoms associated with self-reported heart disease*, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension. Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, BMI, smoking alcohol consumption, physical activity, and prevalent comorbid conditions with the no symptom group as the reference category. Statistically significant ORs are in bold.

| Urologic Symptom | No Symptom | Symptom Severity |

Symptom Duration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Illness | Mild** | Severe*** | <1year | ≥1year | Severe ≥1 year | ||

| Heart disease | Men | ||||||

| Intermittency | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.60, 1.80) | 2.43 (1.09, 5.44) | 1.29 (0.69, 2.43) | 1.44 (0.76, 2.72) | 3.17 (1.31, 7.67) | |

| Frequency | 1.00 | 1.40 (0.82, 2.39) | 1.75 (0.96, 3.18) | 1.20 (0.66, 2.20) | 1.79 (1.04, 3.11) | 2.15 (1.13, 4.12) | |

| Nocturia | 1.00 | 1.69 (1.03, 2.77) | 1.78 (1.02, 3.10) | 1.46 (0.79, 2.70) | 1.87 (1.14, 3.07) | 1.88 (1.00, 3.51) | |

| Women | |||||||

| Weak Stream | 1.00 | 1.11 (0.58, 2.11) | 2.72 (1.48, 5.00) | 1.86 (1.06, 3.26) | 1.20 (0.57, 2.54) | 2.36 (0.91, 6.11) | |

| Straining | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.50, 2.07) | 1.98 (0.77, 5.05) | 1.16 (0.53, 2.53) | 1.51 (0.68, 3.31) | 2.98 (1.23, 7.21) | |

| |

Urgency |

1.00 |

1.08 (0.65, 1.77) |

1.92 (1.14, 3.22) |

1.13 (0.64, 2.00) |

1.61 (0.99, 2.60) |

1.75 (0.97, 3.15) |

| Diabetes | Men | ||||||

| Intermittency | 1.00 | 3.20 (1.77, 5.78) | 1.78 (0.48, 6.59) | 2.17 (1.15, 4.12) | 3.12 (1.46, 6.65) | 2.55 (0.62, 10.56) | |

| Urgency | 1.00 | 1.50 (0.69, 3.29) | 2.45 (1.20, 5.00) | 1.49 (0.74, 3.00) | 2.04 (0.98, 4.28) | 2.40 (1.13, 5.09) | |

| Women | |||||||

| Intermittency | 1.00 | 1.70 (1.03, 2.80) | 1.59 (0.68, 3.70) | 1.39 (0.77, 2.48) | 2.17 (1.16, 4.05) | 1.05 (0.48, 2.29) | |

| |

Nocturia |

1.00 |

2.19 (1.35, 3.54) |

1.98 (1.12, 3.50) |

1.67 (1.02, 2.75) |

2.46 (1.51, 4.04) |

2.46 (1.34, 4.54) |

| Hypertension | Men | ||||||

| Nocturia | 1.00 | 1.34 (0.93, 1.92) | 1.76 (1.14, 2.71) | 1.72 (1.09, 2.71) | 1.36 (0.94, 1.96) | 1.54 (0.94, 2.51) | |

| Women | |||||||

| Weak Stream | 1.00 | 1.14 (0.78, 1.67) | 1.39 (0.79, 2.46) | 1.01 (0.67, 1.53) | 1.57 (0.98, 2.52) | 1.98 (1.12, 3.51) | |

| Straining | 1.00 | 1.44 (0.88, 2.37) | 1.97 (1.04, 3.74) | 1.46 (0.81, 2.64) | 1.73 (1.04, 2.88) | 1.83 (0.88, 3.80) | |

| Urgency | 1.00 | 1.34 (0.90, 2.00) | 1.57 (1.02, 2.41) | 1.37 (0.87, 2.18) | 1.45 (1.01, 2.07) | 1.99 (1.21, 3.27) | |

self-report of myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure, coronary artery bypass or angioplasty stent

Mild = rarely/some of the time

Severe = often/most of the time/always

Among men, a two-fold increase in the odds of T2DM was observed with increased severity or duration of urgency with a similar effect for men reporting severe symptoms for ≥1 year (OR=2.40, 95%CI: 1.13, 5.09). Mild intermittency of any duration was associated with a two- to three-fold increase in the odds of T2DM in men. Among women, nocturia of any degree of severity or duration was significantly associated with a two-fold increase in the odds of T2DM. Additionally, increased duration of intermittency was associated with a two-fold increase in the odds of T2DM in women.

Among men, increased odds of hypertension was observed with increased severity of nocturia (OR=1.76, 95%CI: 1.14, 2.71) but not with increased duration. Among women, an almost two-fold increase in the odds of hypertension was observed for symptoms of severe straining or increased duration of straining symptoms. In addition, increased odds of hypertension was observed among women with increased duration and severity of symptoms of weak stream (OR=1.98, 95%CI: 1.12, 3.51) or urgency (OR=1.99, 95%CI: 1.21, 3.27). Further adjustment for SES in all analyses did not alter observed results.

Discussion

Results from the BACH study show a dose-response pattern overall in the association between severity and duration of lower urinary tract symptoms and chronic illnesses. The association between LUTS and depression was significant in both men and women. In contrast, the pattern of associations of urologic symptoms with heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension varied by gender.

The association of LUTS with risk factors commonly linked to cardiovascular disease has been previously reported. Findings from the NHANES study have shown an inverse relationship between LUTS and increased physical activity, while a positive association was found with heavy smoking (≥50 pack-years) and markers of the metabolic syndrome.5, 14 In contrast, most studies report a weak or no association between LUTS and BMI.4, 5 Results from the Flint Men's Health Study (FMHS) have shown a relationship between LUTS and a history of diabetes as well as heart disease.4 Data from the Olmsted County Study (OCS) show that presence of diabetes in men is associated with progression of LUTS.2 The impact of LUTS on quality of life has been demonstrated,15 and an association of depressed mood and LUTS has been reported by the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS).6

Previous analyses of data from the BACH study have suggested that factors outside the urinary tract contribute to LUTS.3 Results from the present study provide further evidence supporting this hypothesis. Among the likely candidate mechanisms are down-regulation of nitric oxide synthase (NOS),16 autonomic dysregulation or increased adrenergic tone,17 or iatrogenic medication effects due to the use of multiple medications.18 With recent evidence suggesting a role for the L-arginine-nitric oxide (NO)-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathway in depression,19 the NO-cGMP interaction in endothelial cell dysfunction, erectile dysfunction, and depression has an internal consistency that makes this of particular interest as an explanatory mechanism. Potential explanations of the association of heart disease diabetes, or hypertension with a different set of urologic symptoms in men and women include the anatomical differences of the male and female urinary tracts which may result in different physiological responses to common neural (e.g., sympathetic hyperactivity) or vascular (e.g., endothelial dysfunction) correlates of comorbid conditions, and possibly gender differences in interpretation and response to some of the AUA-SI questions. Although the temporal sequence of causality or specific mechanisms of action cannot be assessed by means of cross-sectional data alone, the novel finding that increased severity and duration of urologic symptoms are indicative of increased odds of chronic illnesses supports the hypothesized association between LUTS and conditions outside the urinary tract.

Several potential limitations of this study should be noted. The BACH study is a cross-sectional survey and a temporal sequence between LUTS and onset of chronic illnesses cannot be established at present. Although history of chronic illnesses was assessed by self-report with the potential for reporting and/or recall bias, previous research has demonstrated the reliability and validity of self-report for heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension.20 Observed associations could be influenced by treatment history which has not been factored into this analysis. A full analysis of the influence of medication use on LUTS is beyond the scope of this paper and is the focus of a separate analysis. Strengths of the BACH study include a community-based random sample across a wide age range (30-79), inclusion of large numbers of minority participants representative of Black and Hispanic populations, and a wide range of covariates including sociodemographic, lifestyle, and health variables, which can be adjusted for in the analysis. The BACH study was limited geographically to the Boston area. However, comparison of sociodemographic and health-related variables from BACH with other large regional (Boston Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System) and national (National Health Interview Survey) surveys have shown that the BACH estimates are comparable to national trends on key health related variables.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this study indicate that severity and duration of urologic symptoms, among both men and women, are important factors in the association of these symptoms with major chronic illnesses. The association between urologic symptoms and the presence of clinically significant depression was evident in both men and women. Despite variations by gender in the association of specific urologic symptoms with heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension, the overall pattern observed was an increase in the magnitude of these associations with increased severity and duration of urologic symptoms. These finding provide further evidence of common underlying factors for urologic conditions, and chronic conditions including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and depression.

Funding

The BACH survey is supported by DK 56842 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Additional funding was provided from Pfizer, Inc. for analyses presented in this paper. Raymond Rosen, Varant Kupelian, Carol L. Link, and John B. McKinlay are employees of NERI, who received a grant from Pfizer in connection with the development of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. The Corresponding Author retains the right to provide a copy of the final manuscript to the NIH upon acceptance for publication, for public archiving in PubMed Central as soon as possible but no later than 12 months after publication.

References

- 1.Boyle P, Robertson C, Mazzetta C, Keech M, Hobbs FD, Fourcade R, et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in men and women in four centres. The UrEpik study. BJU Int. 2003;92:409. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke JP, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Roberts RO, Girman CJ, Lieber MM, et al. Diabetes and benign prostatic hyperplasia progression in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Urology. 2006;67:22. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald MP, Link CL, Litman HJ, Travison TG, McKinlay JB. Beyond the lower urinary tract: the association of urologic and sexual symptoms with common illnesses. Eur Urol. 2007;52:407. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joseph MA, Harlow SD, Wei JT, Sarma AV, Dunn RL, Taylor JM, et al. Risk factors for lower urinary tract symptoms in a population-based sample of African-American men. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:906. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rohrmann S, Smit E, Giovannucci E, Platz EA. Association between markers of the metabolic syndrome and lower urinary tract symptoms in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:310. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welch G, Weinger K, Barry MJ. Quality-of-life impact of lower urinary tract symptom severity: results from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Urology. 2002;59:245. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the Urologic Iceberg: Design and Implementation of The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr., O'Leary MP, Bruskewitz RC, Holtgrewe HL, Mebust WK, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badia X, Garcia-Losa M, Dal-Re R, Carballido J, Serra M. Validation of a harmonized Spanish version of the IPSS: evidence of equivalence with the original American scale. International Prostate Symptom Score. Urology. 1998;52:614. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11:139. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green LW. Manual for scoring socioeconomic status for research on health behavior. Public Health Rep. 1970;85:815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schafer J. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman and Hall; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohrmann S, Crespo CJ, Weber JR, Smit E, Giovannucci E, Platz EA. Association of cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and physical activity with lower urinary tract symptoms in older American men: findings from the third National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey. BJU Int. 2005;96:77. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robertson C, Link CL, Onel E, Mazzetta C, Keech M, Hobbs R, et al. The impact of lower urinary tract symptoms and comorbidities on quality of life: the BACH and UREPIK studies. BJU Int. 2007;99:347. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haab F. Discussion: nitric oxide and bladder overactivity. Urology. 2000;55:58. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzgerald MP, Mueller E. Physiology of the lower urinary tract. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;47:18. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200403000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelstein MM. Medical conditions, medications, and urinary incontinence. Analysis of a population-based survey. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almeida RC, Felisbino CS, Lopez MG, Rodrigues AL, Gabilan NH. Evidence for the involvement of L-arginine-nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathway in the antidepressant-like effect of memantine in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2006;168:318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]