Abstract

Objectives

The objectives of this study were to: 1) investigate the relationship between LUTS as defined by the American Urologic Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI) and the metabolic syndrome (MetS); and 2) determine the relationship between individual symptoms comprising the AUA-SI and MetS.

Methods

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey used a two-stage cluster design to recruit a random sample of 2,301 men age 30-79. Analyses were conducted on 1,899 men who provided blood samples. Urologic symptoms comprising the American Urological Association symptom index were included in the analysis. MetS was defined using a modification of the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III guidelines. The association between LUTS and MetS was assessed using odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals estimated using logistic regression models.

Results

Increased odds of MetS were observed among men with mild to severe symptoms (AUA-SI 2-35) compared to men with an AUA-SI score of 0 or 1 (multivariate Odds Ratio (OR)=1.68, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.21, 2.35). A statistically significant association was observed between MetS and voiding symptom score ≥5 (multivariate adjusted OR=1.73, 95%CI: 1.06, 2.80) but not for storage symptom score ≥4 (multivariate adjusted OR=0.94, 95%CI: 0.66, 1.33). Increased odds of MetS were observed even with mild symptoms, primarily for incomplete emptying, intermittency, and nocturia. These associations were observed primarily among younger men (age<60 years) and were null among older men (age≥60 years).

Conclusions

The observed association between urologic symptoms and MetS provides further evidence of common underlying factors between LUTS and chronic conditions outside the urinary tract.

Keywords: metabolic syndrome, lower urinary tract symptoms, epidemiology

Introduction

Increasing evidence from both clinical and epidemiologic studies showing associations between lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and major chronic illnesses, such as heart disease and diabetes, and related lifestyle factors have motivated interest in the contribution of factors outside the urinary tract to urologic symptoms - the so-called “beyond the bladder” hypothesis.1-4 However, few studies have investigated the possible association of LUTS with the metabolic syndrome (MetS), a constellation of cardiovascular risk factors thought to be linked by insulin resistance.

Associations between LUTS or benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and anthropometric measures and obesity has been reported previously,5-8 although findings are inconsistent.9, 10 LUTS have also been associated with components of MetS (hypertension2, 8 and fasting blood glucose7) and associated conditions (erectile dysfunction11) and lifestyle factors (physical activity10, 12-14, alcohol consumption13, 14, smoking13). An enlarged prostate is diagnosed more often among patients with type 2 diabetes, and has been associated with components of MetS.6, 7, 15, 16 Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) show a relationship between markers of MetS and LUTS defined as having three of four urinary symptoms (nocturia, incomplete bladder emptying, weak stream, and hesitancy).4 However, this study was restricted to men 60 years and older and included only 4 of the 7 urologic symptoms comprising the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI).

Using data from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey, the overall goal of the present study was to examine the relative risk of men having three or more components of MetS as a function of the presence and severity of LUTS. Specific objectives of this analysis were to: 1) investigate the association between LUTS as defined by the AUA-SI and MetS; and 2) determine the relationship between individual symptoms comprising the AUA-SI and MetS.

Methods

Overall Design

The BACH survey is a population-based epidemiologic survey of a broad range of urologic symptoms and risk factors in a randomly-selected sample. Detailed methods have been described elsewhere.17 Briefly, BACH used a two-stage stratified cluster sampling design to recruit approximately equal numbers of subjects according to age, gender, and race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, and White). The BACH sample was recruited from April 2002 through June 2005. Interviews were completed with 63.3% of eligible subjects, resulting in a total sample of 5,503 adults (2,301 men, 3,202 women) after written informed consent was obtained. Analyses were conducted on 1,899 men who provided blood samples. All protocols and informed consent procedures were approved by the New England Research Institutes’ Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

Data were obtained during a 2-hour in-person interview, conducted by a trained (bilingual) phlebotomist/interviewer in the subject's home. A random, not necessarily fasting, venous blood sample (20 ml) was obtained and height, weight, hip and waist circumference were measured along with self-reported information on medical history, major comorbidities, lifestyle and psychosocial factors, and symptoms of urologic conditions. Two blood pressure measurements were obtained 2 minutes apart and were averaged. Medication use in the past month was collected using a combination of drug inventory and self-report with a prompt by indication.

Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS)

LUTS were assessed using the American Urological Symptom Index (AUA-SI), a clinically validated measure of urological symptoms with a reliable Spanish version.18, 19 The AUA-SI was used both as a continuous variable and categorized into two groups as none or mild symptoms (AUA-SI<8) versus moderate or severe symptoms (AUA-SI≥8). As an increase in the prevalence of MetS was observed with mild LUTS (AUA-SI 2-7), the AUA-SI was also categorized as 0-1, 2-7, and 8-35. Symptoms were further categorized as voiding (incomplete emptying, weak stream, intermittency, straining) and storage (frequency, urgency, nocturia) symptoms. Voiding and storage symptom scores were dichotomized ≥5 vs. <5 for voiding and ≥4 vs. <4 for storage.2 Individual symptoms were first categorized as none, mild (rarely/a few times) and severe (fairly often/usually/almost always), then into two groups as severe vs. none/mild. Nocturia assessed as the number of time having to get up at night to urinate was first categorized as 0, 1, ≥2, then dichotomized as ≥2 vs. 0 or 1. Bother associated with urologic symptoms was assessed by a validated quality of life questionnaire for BPH.20 A bother score was obtained by summing the score from 7 questions (scores for answers to each of questions ranged from 0 [none of the time] to 4 [all of the time] on the interference of urinary symptoms with various activities.

Metabolic syndrome definition

The metabolic syndrome (MetS) was defined according to the ATP III guidelines (National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel ATP III).21 Available BACH data permits close adherence to the ATP III guidelines with the exception that available blood samples were usually non-fasting, impacting analyses of triglycerides and fasting glucose. In this analysis, MetS was defined, using a previously published modification of the ATP III guidelines,22 as the presence of three or more of the following: 1) waist circumference >102 cm; 2) systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg or antihypertensive medication use; 3) high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol <40 mg/dl or lipid medication use; 4) self-reported type 2 diabetes or elevated blood sugar or diabetes medication use; 5) triglycerides >150 mg/dl.

Covariates

Physical activity was measured using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) and was categorized as low (<100), medium (100-250), and high (>250).23 Alcohol consumption was defined as alcoholic drinks consumed per day: 0, <1, 1-2.9, ≥3 drinks per day. Never smokers were defined as having smoked less then 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and pack-years of smoking were calculated by multiplying the number of packs smoked per day by the number of years smoked. Pack-years were categorized as <10, 10-19, and 20 or more pack-years. The socioeconomic status (SES) index was calculated using a combination of education and household income.24 SES was categorized as low (lower 25% of the distribution of the SES index), middle (middle 50% of the distribution), and high (upper 25% of the distribution).

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were estimated using logistic regression methods to investigate the magnitude of the association between LUTS and MetS and adjust for potential confounders. A multiple imputation technique was used to obtain plausible variables for missing data.25 The proportion of participants with missing data was 0.6% for the AUA-SI, 0.7% for self-reported type 2 diabetes or elevated blood sugar, 0.5% for waist circumference, 1.1% for lifestyle variables (physical activity, alcohol consumption, pack-years of smoking), and 5.4% for the SES index. Overall, 7.5% participants had missing data on at least one of these variables. Twenty-five multiple imputations were performed separately by gender and race/ethnicity using all relevant variables. Observations were weighted inversely proportional to their probability of selection so that results would be generalizable to the city of Boston. Weights were post-stratified to the Boston population according to the 2000 Census. Analyses were conducted in version 9.1 of SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and version 9.0.1 of SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA).

Results

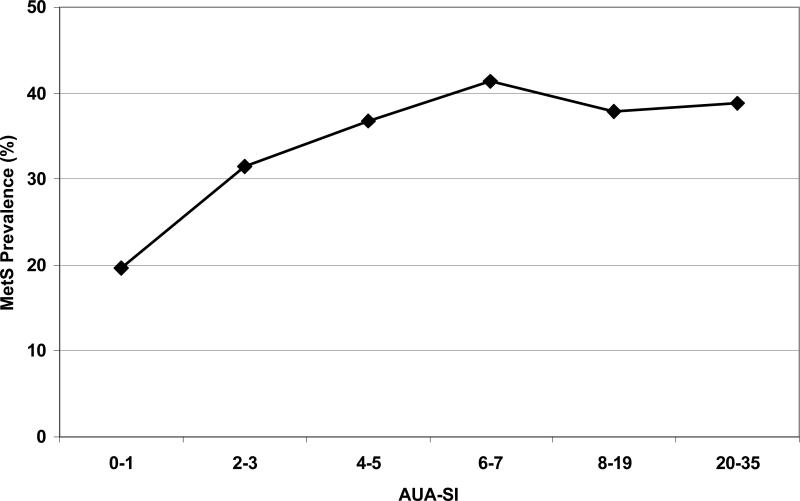

Overall prevalence of MetS was 29.0% (Table 1), comparable to rates of 29.3% and 30.6% in adults age ≥20 years from NHANES III and NHANES 1999-2000 respectively.26 Overall prevalence of moderate/severe LUTS (AUA-SI≥8) was 19.3% and age-specific rates were comparable to previously reported rates.27 Prevalence of both MetS and LUTS did not differ by race/ethnicity (data not shown). A trend in increasing prevalence of MetS with increasing AUA-SI scores was observed (Figure 1). Prevalence of MetS was lowest for men reporting either no symptoms or one symptom rarely at around 20% and increased with mild LUTS (AUA-SI 2-7) to about 40% with no further increase with moderate to severe LUTS (AUA-SI 8-35).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the analysis sample of 1,899 men who provided blood samples. Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey 2002-2005.

| Observed N (weighted %) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | 30-39 | 512 (37.2) |

| 40-49 | 554 (25.8) | |

| 50-59 | 436 (17.8) | |

| 60-69 | 260 (12.2) | |

| 70-79 | 137 (7.0) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | White | 710 (61.9) |

| Black | 538 (25.1) | |

| Hispanic | 651 (13.0) | |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | Low | 785 (23.9) |

| Middle | 787 (48.9) | |

| High | 327 (27.2) | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) kg/m2 | <25.0 | 495 (26.8) |

| 25.0-29.9 | 740 (39.5) | |

| ≥30 | 665 (33.7) | |

| Physical Activity (PASE) | Low (<100) | 534 (25.5) |

| Medium (100-250) | 900 (48.2) | |

| High (>250) | 465 (26.3) | |

| Alcohol consumption | None | 637 (28.8) |

| <1 drinks/day | 694 (40.2) | |

| 1-2.9 drinks/day | 362 (24.4) | |

| ≥3 drinks/day | 206 (9.2) | |

| Smoking Pack-years | Never | 815 (45.6) |

| <10 | 517 (26.5) | |

| 10-19 | 218 (11.5) | |

| 20+ | 349 (16.5) | |

| LUTS medication use | 49 (1.96) | |

| AUA-SI* | ≥8 | 368 (19.3) |

| Voiding score** | ≥5 | 238 (12.8) |

| Storage score** | ≥4 | 553 (28.9) |

| Metabolic syndrome components | ||

| Diabetes/elevated blood sugar/diabetes medication use | 284 (11.5) | |

| Hypertension*** | 1004 (46.8) | |

| HDL<40 mg/dl or lipid medication use | 777 (39.8) | |

| Triglycerides >150 mg/dl | 868 (42.0) | |

| Waist >102 cm | 623 (33.4) | |

| Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) | 613 (29.0) |

American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI)

Cutoff values from Joseph et al, AJE 2003, 157(10):906-14

Systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg or antihypertensive medication use

Figure 1.

Prevalence of MetS increases with increasing AUA-SI score in the mild symptoms range (AUA-SI scores of 2 to 7) and stabilizes with moderate (AUA-SI of 8 to 19) and severe symptoms (AUA-SI of 20 to 35). Overall trend test p-value = 0.003.

Similarly, the association between the AUA-SI and MetS (Table 2) is observed when comparing mild and moderate/severe symptoms to those with an AUA-SI of 0 or 1 (age-adjusted odds ratio (OR)=1.83, 95% confidence interval (CI):1.29, 2.60). This association is slightly attenuated in multivariate analyses but remained statistically significant (multivariate OR=1.68, 95%CI:1.21, 2.35). A statistically significant association was observed between MetS and voiding score (multivariate OR=1.73, 95%CI:1.06, 2.80) but not with storage score ≥4 (multivariate OR=0.94, 95%CI:0.66, 1.33). Using the AUA-SI, voiding, and storage scores as continuous variables, similar results were observed (data not shown).

Table 2.

Association of the metabolic syndrome (dependent variable) and LUTS (independent variable) assessed using the AUA Symptom Index (AUA-SI) and voiding (obstructive) and storage (irritative) scores. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

| Age-adjusted OR (95%CI) |

Multivariate* adjusted OR (95%CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUA-SI | <8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥8 | 1.28 (0.84, 1.95) | 1.14 (0.73, 1.78) | |||

| 0-1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 2-7 | 1.83 (1.23, 2.72) |

1.83† (1.29, 2.60) |

1.72 (1.10, 2.52) |

1.68† (1.21, 2.35) |

|

| |

≥8 |

1.85 (1.19, 2.86) |

1.59 (1.02, 2.48) |

||

| Voiding score** | <5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| |

≥5 |

1.82 (1.11, 3.01) |

|

1.73 (1.06, 2.80) |

|

| Storage score** | <4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| |

≥4 |

1.35 (0.96, 1.91) |

|

0.94 (0.66, 1.33) |

|

| Bother Score | Continuous | 1.06 (1.01, 1.12) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 1-8 | 0.86 (0.55, 1.36) | 0.84 (0.52, 1.34) | |||

| ≥9 | 2.95 (1.34, 6.59) | 2.39 (1.01, 5.67) | |||

Adjusted for age, race, SES, physical activity, alcohol consumption, pack-year of smoking, LUTS medications

Cutoff values from Joseph et al, AJE 2003, 157(10):906-14

OR for AUA-SI categories 2-7 and ≥8 combined

Table 3 presents the association of individual symptoms and MetS. MetS was associated with mild/severe incomplete emptying (multivariate OR=1.58, 95%CI:1.03, 2.44), intermittency (multivariate OR=1.57, 95%CI:1.06, 2.30), and nocturia (multivariate OR=1.69, 1.21, 2.36). Increased odds of MetS were observed for men reporting severe urgency (age-adjusted OR=1.92, 95%CI:1.14, 2.34). However, the magnitude of this association was attenuated and was statistically non-significant in multivariate analyses. No association was observed between MetS and either weak stream, straining, or frequency.

Table 3.

Association of the metabolic syndrome with individual urologic symptoms comprising the AUA symptom score. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Bold indicates statistical singificance.

| Age-adjusted OR (95%CI) |

Multivariate* adjusted OR (95%CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Emptying** | None/Mild | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Severe | 1.26 (0.37, 1.91) | 0.94 (0.66, 1.33) | |||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Mild | 1.51 (0.98, 2.33) | 1.49† (0.94, 2.37) |

1.69 (1.11, 2.58) |

1.58† (1.03, 2.44) |

|

| |

Severe |

1.43 (0.41, 4.97) |

1.18 (0.38, 3.70) |

||

| Intermittency** | None/Mild | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Severe | 1.63 (0.83, 3.20) | 1.47 (0.73, 2.97) | |||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Mild | 1.60 (0.98, 2.60) |

1.64† (1.10. 2.45) |

1.55 (0.95, 2.52) |

1.57† (1.06, 2.30) |

|

| |

Severe |

1.79 (0.92, 3.49) |

1.62 (0.82, 3.21) |

||

| Weak Stream** | None/Mild | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Severe | 0.80 (0.45, 1.41) | 0.74 (0.40, 1.38) | |||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Mild | 1.19 (0.82, 1.71) | 1.07† (076, 1.50) |

1.15 (0.77, 0.77) | 1.03† (0.70, 1.51) |

|

| |

Severe |

0.82 (0.46,1.47) |

0.76 (0.40, 1.44) |

||

| Straining** | None/Mild | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Severe | 1.82 (0.45, 7.82) | 1.58 (0.33, 7.51) | |||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Mild | 1.30 (0.77, 2.17) | 1.42† (0.81, 2.48) |

1.20 (0.69, 2.07) | 1.29† (0.72, 2.31) |

|

| |

Severe |

1.88 (0.44, 3.10) |

1.60 (0.34, 7.76) |

||

| Frequency** | None/Mild | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Severe | 0.76 (0.48, 1.21) | 0.76 (0.44, 1.17) | |||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Mild | 0.93 (0.64, 1.34) | 0.86† (0.61, 1.20) |

0.91 (0.60, 1.38) | 0.82† (0.56, 1.20) |

|

| |

Severe |

0.74 (0.45, 1.20) |

0.69 (0.40, 1.17) |

||

| Urgency** | None/Mild | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Severe | 1.92 (1.14, 2.34) | 1.63 (0.93, 2.85) | |||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Mild | 1.28 (0.76, 2.16) | 1.45† (0.95, 2.21) |

1.24 (0.71, 2.16) | 1.35† (0.86, 2.13) |

|

| |

Severe |

2.04 (1.20, 3.47) |

1.72 (0.97, 2.03) |

||

| Nocturia*** | 0-1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥2 | 1.63 (1.13,2.34) | 1.39 (0.96, 1.99) | |||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 1.70 (1.14, 2.53) | 1.88† (1.37, 2.58) | 1.62 (1.07, 2.44) | 1.69† (1.21, 2.36) | |

| ≥2 | 2.19 (1.52, 3.14) | 1.82 (1.26, 2.64) | |||

Adjusted for age, race, SES, physical activity, alcohol consumption, pack-year of smoking, LUTS medications

Symptoms categorized as: None (I do not have the symptom) Mild (rarely/a few times) Severe (fairly often/usually/almost always)

Number of times have to go to the bathroom at night after falling asleep

OR for categories mild and severe combined

Table 4 presents the association of urologic symptoms and individual components of MetS. Statistically significant associations between urologic symptoms and type 2 diabetes and/or elevated blood sugar were observed. The association with the other components were generally weak or null with the exception of the association of nocturia with increased odds of hypertension (adjusted OR=2.00, 95%CI:1.27, 3.14) and elevated triglycerides (adjusted OR=1.64, 95%CI:1.07, 2.51), and mild LUTS (AUA-SI 2-7) and mild incomplete emptying with waist circumference >102 cm. Previous analyses of BACH data have shown that the association of urologic symptom and measures of adiposity, including BMI and waist circumference, follow a U shape distribution in men, with higher prevalence of urologic symptoms with low or high BMI and waist circumference.28

Table 4.

Association of LUTS with components of the metabolic syndrome. Multivariate adjusted* odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Bold indicates statistical significance.

| T2DM/elevated blood sugar/diabetes medication use | Hypertension/Antihypertensive medication use | HDL<40 mg/dl / lipid medication use | Triglycerides >150 mg/dl | Waist >102cm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUA-SI | 0-1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2-7 | 1.95 (1.22, 3.12) | 1.28 (0.87, 1.88) | 1.38 (0.93, 2.06) | 1.39 (0.99, 1.95) | 1.44 (1.01, 2.07) | |

| 8-35 | 2.87 (1.56, 5.31) | 1.15 (0.73, 1.82) | 1.25 (0.79, 1.99) | 1.04 (0.65, 1.66) | 1.07 (0.66, 1.73) | |

| Voiding Score | <5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥5 | 1.93 (1.17, 3.18) | 0.71 (0.46, 1.09) | 1.44 (0.85, 2.44) | 0.82 ( 0.5, 1.35) | 1.39 (0.86, 2.25) | |

| Storage Score | <4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥4 | 1.58 (0.95, 2.64) | 1.04 (0.74, 1.47) | 0.86 (0.61, 1.22) | 0.8 (0.57, 1.13) | 0.75 (0.53, 1.05) | |

| Incomplete Emptying | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 1.81 (1.04, 3.15) | 1.04 (0.70, 1.53) | 1.25 (0.85, 1.84) | 0.98 (0.68, 1.41) | 1.70 (1.17, 2.47) | |

| Severe | 0.90 (0.40, 2.01) | 1.28 (0.37, 4.40) | 1.02 (0.39, 2.68) | 0.66 (0.21, 2.06) | 1.48 (0.58, 3.75) | |

| Intermittency | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 2.77 (1.51, 5.08) | 0.96 (0.63, 1.46) | 1.32 (0.85, 2.07) | 1.27 (0.84, 1.94) | 1.14 (0.73, 1.79) | |

| Severe | 2.06 (0.87, 4.86) | 1.05 (0.51, 2.17) | 1.30 (0.69, 2.44) | 0.65 (0.35, 1.21) | 1.43 (0.75, 2.75) | |

| Weak Stream | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 1.72 (1.04, 2.82) | 0.82 (0.55, 1.23) | 1.06 (0.68, 1.66) | 0.90 (0.59, 1.38) | 1.03 (0.64, 1.67) | |

| Severe | 1.25 (0.62, 2.53) | 0.53 (0.30, 0.94) | 0.73 (0.36, 1.47) | 0.54 (0.27, 1.05) | 0.65 (0.34, 1.24) | |

| Straining | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 1.95 (0.89, 4.25) | 1.18 (0.67, 2.09) | 1.02 (0.61, 1.68) | 0.89 (0.52, 1.51) | 1.50 (0.93, 2.42) | |

| Severe | 1.61 (0.71, 3.64) | 0.74 (0.34, 1.61) | 1.66 (0.39, 7.07) | 0.57 (0.17, 1.97) | 1.20 (0.34, 4.28) | |

| Frequency | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 1.89 (1.19, 3.01) | 0.85 (0.58, 1.22) | 1.14 (0.78, 1.67) | 1.00 (0.71, 1.43) | 0.68 (0.45,1.01) | |

| Severe | 1.73 (0.89, 3.37) | 0.93 (0.59, 1.45) | 0.63 (0.39, 1.00) | 0.66 (0.41, 1.06) | 0.67 (0.41, 1.08) | |

| Urgency | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 1.60 (0.73, 3.48) | 0.82 (0.51, 1.33) | 1.11 (0.69, 1.78) | 1.02 (0.64, 1.62) | 1.09 (0.66, 1.79) | |

| Severe | 2.78 (1.48, 5.23) | 1.23 (0.72, 2.07) | 1.00 (0.56, 1.77) | 0.84 (0.49, 1.44) | 1.52 (0.87, 2.63) | |

| Nocturia | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 1.67 (0.82, 3.39) | 1.24 (0.86, 1.79) | 1.31 (0.92, 1.87) | 1.46 (1.01, 2.13) | 1.33 (0.90, 1.96) | |

| ≥2 | 2.62 ( 1.4, 4.92) | 2.00 (1.27, 3.14) | 1.40 (0.93, 2.09) | 1.64 (1.07, 2.51) | 1.34 (0.90, 1.98) |

Adjusted for age, race, SES, physical activity, alcohol consumption, pack-year of smoking, LUTS medications

Analyses were stratified by age (<60 years and ≥60 years) to determine whether the association between LUTS and MetS was different among younger men compared to older men (Table 5). Although interaction terms between LUTS and age were statistically non-significant, an overall trend was seen towards stronger associations among younger men (age<60 years) while most of the associations observed were null among older men (age≥60 years). This effect was most notable for the overall AUA-SI and MetS association, and some individual symptoms such as incomplete emptying, intermittency, and nocturia. Few differences were observed in the patterns of association between LUTS and individual components of MetS among younger compared to older men (data not shown).

Table 5.

Association of the metabolic syndrome and LUTS stratified by age. Adjusted* odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Bold indicates a statistical significance.

| Age<60 (N=1502), Adjusted* OR (95%CI) |

Age≥60 (N=397), Adjusted* OR (95%CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUA-SI | 0-1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2-7 | 1.92 (1.29, 2.86) |

1.99† (1.39, 2.86) |

1.14 (0.55, 2.38) | 1.04† (0.51, 2.10) |

|

| |

≥8 |

2.21 (1.28, 3.82) |

0.92 (0.40, 2.13) |

||

| Voiding score | <5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| |

≥5 |

1.86 (0.96, 3.58) |

|

1.73 (0.87, 3.44) |

|

| Storage score | <4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| |

≥4 |

1.15 (0.75, 1.77) |

|

0.87 (0.44, 1.71) |

|

| Bother score | Continuous | 1.09 (1.01, 1.12) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.07) | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 1-8 | 0.89 (0.50, 1.61) | 0.86 (0.43, 1.71) | |||

| |

≥9 |

5.04 (1.48, 17.09) |

|

1.56 (0.72, 3.51) |

|

| Incomplete Emptying** | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 2.16 (1.35, 3.46) |

2.01† (1.26, 3.20) |

0.98 (0.50, 1.91) | 0.92† (0.49, 1.71) |

|

| |

Severe |

1.48 (0.38, 5.78) |

0.68 (0.22, 2.14) |

||

| Intermittency** | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 2.14 (1.20, 3.79) |

1.98† (1.22, 3.20) |

0.89 (0.45, 1.77) | 0.98† (0.53, 1.84) |

|

| |

Severe |

1.54 (0.70, 3.36) |

1.25 (0.43, 3.66) |

||

| Weak Stream** | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 1.45 (0.85, 2.48) | 1.28† (0.79, 2.08) |

1.22 (0.61, 2.44) | 1.03† (0.54, 1.95) |

|

| |

Severe |

0.88 (0.35, 2.24) |

0.73 (0.28, 1.91) |

||

| Straining** | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 1.53 (0.75, 3.13) | 1.65† (0.84, 3.23) |

0.94 (0.38, 2.33) | 1.02† (0.45, 2.33) |

|

| |

Severe |

2.02 (0.41, 9.98) |

1.63 (0.41, 6.54) |

||

| Frequency** | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 1.01 (0.66, 1.55) | 0.94† (0.63, 1.41) |

0.74 (0.38, 1.42) | 0.68† (0.37, 1.24) |

|

| |

Severe |

0.81 (0.43, 1.55) |

0.61 (0.26, 1.45) |

||

| Urgency** | None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 1.40 (0.70, 2.78) | 1.52† (0.85, 2.70) |

1.27 (0.62, 2.61) | 1.53† (0.85, 2.77) |

|

| |

Severe |

2.04 (0.90, 4.64) |

2.14 (0.96, 4.74) |

||

| Nocturia*** | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 2.15 (1.34, 3.43) | 2.24† (1.48, 3.39) | 0.68 (0.33, 1.39) | 0.80† (0.43, 1.50) | |

| ≥2 | 2.43 (1.46, 4.03) | 0.93 (0.46, 1.88) | |||

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, SES, physical activity, alcohol consumption, pack-years of smoking, LUTS medications

Symptoms categorized as: None (I do not have the symptom) Mild (rarely/a few times) Severe (fairly often/usually/almost always)

Number of times have to go to the bathroom at night after falling asleep

OR for AUA-SI categories 2-7 and ≥8 combined, or categories mild and severe combined

Discussion

Results from the BACH survey show that LUTS, assessed by the AUA-SI, are associated with MetS. Compared to men with no symptoms, increased odds of MetS for men with mild symptoms were comparable to the effect observed among men with moderate to severe symptoms. This pattern is also observed for individual symptoms associated with MetS, especially intermittency, incomplete emptying, and nocturia.These associations were stronger among younger men (age<60 year) compared to older men (age≥60 years). A statistically significant association was observed between MetS and the voiding symptom score but not with the storage symptom score.

Data from NHANES III have shown a statistically significant association between MetS and LUTS (OR = 1.82, 95%CI: 1.11, 2.94) among men 60 years and older, with LUTS defined as a report of three or four urologic symptoms.4 While results from the present study show a similar association of LUTS, assessed using the AUA-SI and MetS, the association in our study was seen primarily among younger men (age<60 years). Enlargement of the prostate has been proposed as a possible link between LUTS and MetS as cross-sectional data suggest an association between BPH and increased body size, as well as components of MetS such as low HDL and elevated fasting insulin or glucose.6, 7 In contrast, data from longitudinal epidemiologic studies have shown no association between anthropometric measurements, hypertension, or history of diabetes with development of clinical BPH.9, 10 In contrast, a longitudinal study of 250 patients with LUTS reported a correlation between an increase in prostate size and diabetes, hypertension, obesity, high insulin and low HDL levels.15 Although an association of LUTS and MetS was observed in the present study, the temporal sequence between LUTS and MetS cannot be established from analyses of cross-sectional data.

Possible pathophysiologic mechanisms at play to explain the relationship of voiding rather than storage symptoms with MetS include the influence of sustained hyperglycemia on the viability of parasympathetic neurons in the pelvic ganglion. Animal studies have shown that long term elevated serum glucose induces a neuronal apoptosis that favors parasympathetic neuron loss over sympathetic ones.29 Such an unbalanced loss of autonomic neurons might induce an oversupply of sympathetic tone over parasympathic efferent activity resulting in increased bladder neck obstruction and reduced bladder power which combined might produce an increase in obstructive symptoms as noted here. Increased glucose level are likely to be accompanied by hyperinsulinemia which results in an increase in IGF, a known prostatic mitogen and induces a reduction in proapoptotic cascades in the prostate.30 These changes should culminate in increased prostate growth and an increase in voiding symptoms, as noted in this report. The emerging role of PDE-5 inhibitors for the treatment of LUTS has recently revealed that NOS-NO/cGMP pathway may influence voiding symptoms via nitrinergic supply to the prostate or bladder, or by bladder perfusion induced compliance changes.31, 32 Such influences are likely to be impaired in obese men with MetS. Alternative hypotheses include pelvic atherosclerosis leading to chronic ischemia of the bladder, penis, and prostate, which may result in impairment of lower urinary tract function.33, 34

Although diabetes is the most common cause of peripheral neuropathy and is linked with several aspects of voiding dysfunction, even in overt diabetes the mechanism of voiding dysfunction in males is unknown. An emerging consensus of investigators suggest that diabetic-linked bladder neuropathy is principally a sensory defect resulting in a delayed desire to void due to the absence of urgency.35 Over time, this putative delay in desire results in a large bladder capacity, decreased detrusor contractility, impaired outflow and increased post void residual urine. An associated motor neuropathy, hypotonic bladder, has also been described. Despite these proposed mechanisms, involuntary bladder contractions and detrusor hyperreflexia is a major component of the voiding complaint.36, 37

These findings have important diagnostic and management implications. Patients who present with components of metabolic dysfunction should be routinely queried with respect to urologic function, particularly voiding symptoms such as intermittency, incomplete emptying, and nocturia, as well as their degree of associated bother. Sexual dysfunction symptoms, particularly erectile dysfunction, are similarly reported by the majority of men with MetS and should be routinely evaluated. The role of lifestyle changes, such as weight loss and increased physical activity, in the management of urologic symptoms in patients with MetS remains to be established. In addition to management of the components of metabolic dysfunction, first-line medications (e.g., alpha blockers, PDE-5 inhibitors) should be recommended when indicated for management of voiding and sexual dysfunction symptoms in these patients.

Several potential study limitations should be noted. As fasting blood samples were not obtained, available data permits close approximation, but not perfect adherence, to the ATP III guidelines for the definition of MetS.15,16 Despite this recognized limitation, our approach has scientific merit because 1) the ATP III components have always been suggested guidelines, not an immutable clinically validated definition; 2) there is continuing debate over which components of MetS should be included, removed, or added; 3) it is employed as a concept for purposes of epidemiological analysis rather that for clinical purposes. The benefits of using data from a large population-based sample outweigh the recognized limitation associated with the measurement of some components of MetS. The BACH study was limited geographically to the Boston area. However, comparison of sociodemographic and health-related variables from the BACH survey with other large regional (Boston Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)) and national (National Health Interview Survey, BRFSS, NHANES) surveys have shown that BACH estimates are comparable on health related variables. Strengths of the BACH study include a community-based random sample across a wide age range (30-79 years), inclusion of large numbers of minority participants representative of both the Black and Hispanic populations, and collection of a broad number of covariates on sociodemographic, lifestyle, and health factors that can be adjusted for in the analysis.

In summary, the results of this study demonstrate an association between urologic symptoms and MetS. Increased odds of MetS were observed even with mild symptoms, primarily for incomplete emptying, intermittency, and nocturia. These association were stronger among younger men (age<60 years) compared to older men (age≥65 years). Further research is needed to understand the common pathophysiology of LUTS and MetS, especially longitudinal studies to determine a temporal sequence and investigation of this association among women as a relationship between chronic illnesses and LUTS has been reported previously in both men and women.1 Additional studies are needed to explore the treatment impact and correlation of comorbid conditions and symptoms associated with the individual components of MetS.

Funding

The BACH survey is supported by DK 56842 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. Additional funding was provided from Pfizer, Inc. for analyses presented in this paper. Varant Kupelian, Raymond Rosen, Susan Hall, Carol L. Link, and John B. McKinlay are employees of NERI, who received funding from Pfizer in connection with the development of the manuscript. The Corresponding Author retains the right to provide a copy of the final manuscript to the NIH upon acceptance for publication, for public archiving in PubMed Central as soon as possible but no later than 12 months after publication.

References

- 1.Fitzgerald MP, Link CL, Litman HJ, Travison TG, McKinlay JB. Beyond the lower urinary tract: the association of urologic and sexual symptoms with common illnesses. Eur Urol. 2007;52:407. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joseph MA, Harlow SD, Wei JT, Sarma AV, Dunn RL, Taylor JM, et al. Risk factors for lower urinary tract symptoms in a population-based sample of African-American men. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:906. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michel MC, Mehlburger L, Schumacher H, Bressel HU, Goepel M. Effect of diabetes on lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2000;163:1725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rohrmann S, Smit E, Giovannucci E, Platz EA. Association between markers of the metabolic syndrome and lower urinary tract symptoms in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:310. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Chute CG, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, et al. Obesity and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:989. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammarsten J, Hogstedt B, Holthuis N, Mellstrom D. Components of the metabolic syndrome-risk factors for the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 1998;1:157. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsons JK, Carter HB, Partin AW, Windham BG, Metter EJ, Ferrucci L, et al. Metabolic factors associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2562. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohrmann S, Smit E, Giovannucci E, Platz EA. Associations of obesity with lower urinary tract symptoms and noncancer prostate surgery in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:390. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke JP, Rhodes T, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Roberts RO, Girman CJ, et al. Association of anthropometric measures with the presence and progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:41. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meigs JB, Mohr B, Barry MJ, Collins MM, McKinlay JB. Risk factors for clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia in a community-based population of healthy aging men. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:935. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen RC, Giuliano F, Carson CC. Sexual dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Eur Urol. 2005;47:824. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Platz EA, Kawachi I, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, et al. Physical activity and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2349. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.21.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Platz EA, Rimm EB, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, et al. Alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohrmann S, Crespo CJ, Weber JR, Smit E, Giovannucci E, Platz EA. Association of cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and physical activity with lower urinary tract symptoms in older American men: findings from the third National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey. BJU Int. 2005;96:77. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammarsten J, Hogstedt B. Clinical, anthropometric, metabolic and insulin profile of men with fast annual growth rates of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Blood Press. 1999;8:29. doi: 10.1080/080370599438365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammarsten J, Hogstedt B. Hyperinsulinaemia as a risk factor for developing benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2001;39:151. doi: 10.1159/000052430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52:389. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr., O'Leary MP, Bruskewitz RC, Holtgrewe HL, Mebust WK, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badia X, Garcia-Losa M, Dal-Re R, Carballido J, Serra M. Validation of a harmonized Spanish version of the IPSS: evidence of equivalence with the original American scale. International Prostate Symptom Score. Urology. 1998;52:614. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein RS, Deverka PA, Chute CG, Panser L, Oesterling JE, Lieber MM, et al. Validation of a new quality of life questionnaire for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1431. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kupelian V, Shabsigh R, Araujo AB, O'Donnell AB, McKinlay JB. Erectile dysfunction as a predictor of the metabolic syndrome in aging men: results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 2006;176:222. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green LW. Manual for scoring socioeconomic status for research on health behavior. Public Health Rep. 1970;85:815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schafer J. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman and Hall; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokdad AH. Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among u.s. Adults. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2444. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyle P, Robertson C, Mazzetta C, Keech M, Hobbs FD, Fourcade R, et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in men and women in four centres. The UrEpik study. BJU Int. 2003;92:409. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Link CL, McKinlay JB. Does america's expanding waistline increase the likelihood of urologic symptoms? Results from the boston area community health (BACH) study. Journal of Urology. 2008;179:141. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cellek S, Rodrigo J, Lobos E, Fernandez P, Serrano J, Moncada S. Selective nitrergic neurodegeneration in diabetes mellitus - a nitric oxide-dependent phenomenon. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1804. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasturi S, Russell S, McVary KT. Metabolic syndrome and lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr Urol Rep. 2006;7:288. doi: 10.1007/s11934-996-0008-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McVary KT, Monnig W, Camps JL, Young JM, Tseng L-J, van den Ende G. Sildenafil Citrate Improves Erectile Function and Urinary Symptoms in Men with Erectile Dysfunction and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Associated with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Randomized Double-Blind Trial. J Urol. 2007;177:1071. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McVary KT, Roehborn C, Kaminetsky J, Auerbach S, Wachs B, Young J, et al. Tadalafil Relieves Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS) Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH). J Urol. 2007;177:1401. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponholzer A, Madersbacher S. Lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile dysfunction; links for diagnosis, management and treatment. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19:544. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shenfeld OZ, Meir KS, Yutkin V, Gofrit ON, Landau EH, Pode D. Do atherosclerosis and chronic bladder ischemia really play a role in detrusor dysfunction of old age? Urology. 2005;65:181. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown JS, Wessells H, Chancellor MB, Howards SS, Stamm WE, Stapleton AE, et al. Urologic Complications of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:177. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Starer P, Libow L. Cystometric evaluation of bladder dysfunction in elderly diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueda T, Yoshimura N, Yoshida O. Diabetic cystopathy: relationship to autonomic neuropathy detected by sympathetic skin response. J Urol. 1997;157:580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]