Abstract

Novel influenza A (H1N1) virus is the pathogen of recent global outbreaks of febrile respiratory infection. We herein report the imaging findings of pulmonary complication in two patients with novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. The first patient without secondary infection showed the ill-defined ground-glass opacity nodules and patch areas of ground-glass opacities. The second patient with secondary pneumococcal pneumonia showed areas of lobar consolidation in the right middle lobe and left lower lobe and ground-glass opacities.

Keywords: Influenza, human; Lung, infection; Lung, CT; Lung, radiography

From April 2009, outbreaks of novel influenza A (H1N1) virus occurred world-widely. It has some characteristics that may be differentiated from the seasonal influenza virus, such as involving younger patient. Clinical outcomes of this pathogen are reported as ranging from self-limited illness to respiratory failure or death (1-3). Although the chest radiographic findings of the novel influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia were described in a clinical report (2), the CT findings have not yet been described. Therefore, we report our experiences of two cases of novel influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia with chest CT findings.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

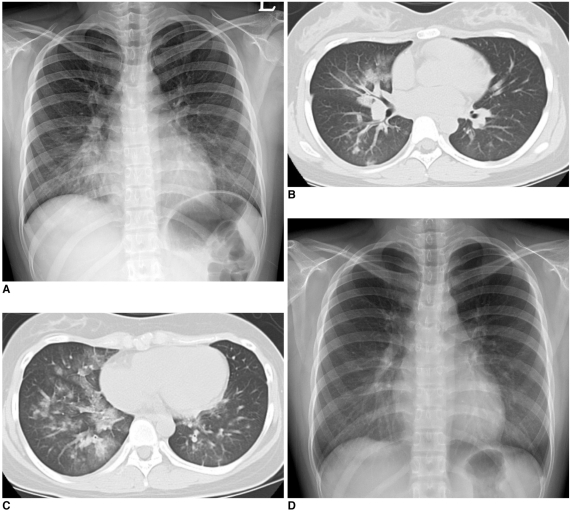

A 16-year-old girl presenting fever, cough and sore throat for one day was admitted to the emergency room of our institution. She had no history of recent travel abroad, and nobody was positive on novel influenza A (H1N1) among her family or classmates. On examination, the patient had an elevated temperature (39.0℃) and tachycardia (117/min). Chest auscultation revealed inspiratory crackles in right lower lung field. The results of initial laboratory evaluation were as follows; WBC count 6,900/mm3, neutrophil 91% and CRP 4.85 mg/dL. Initial chest radiograph (Fig. 1A) showed an ill-defined increased opacity in right lower lung zone. Real time reverse-transcriptase-polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) test revealed positive result for novel influenza A (H1N1). The blood culture or other examinations to detect the coinfected pathogens were all negative. Therefore, she was diagnosed to have novel influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia, and treated with oseltamivir phophate, levofloxacin and ceftriaxone. Three days later, because the chest radiograph showed aggravation in extent of pneumonia, high-resolution chest CT (HRCT) was performed and showed ill-defined ground-glass opacities with interlobular septal thickening and some ill-defined nodules in right middle and lower lobes (Fig. 1B, C). These findings of CT scans were consistent with the findings of viral pneumonia. After the continuation of medical treatment, the symptoms and infiltration on chest radiograph (Fig. 1D) improved.

Fig. 1.

16-year-old girl diagnosed as novel influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia without secondary infection.

A. Initial chest radiograph shows ill-defined increased opacity in right lower lung zone.

B, C. High-resolution chest CT scans show ill-defined ground-glass opacities with interlobular septal thickening and some ill-defined nodules in right middle and lower lobes.

D. Follow-up chest radiograph after medication shows improvement of infiltration in lung.

Case 2

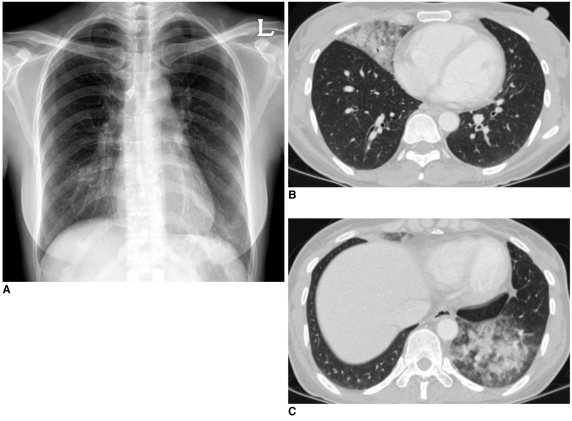

A 42-year-old woman was admitted to our emergency room for dyspnea and hemoptysis. Myalgia, cough and sore throat developed 6 days ago, and she was diagnosed to have an upper respiratory infection (URI) in primary clinic, and took medicine. However the symptoms persisted and dyspnea, hemoptysis and foul-ordered sputum developed newly. On admission, her body temperature was within normal range (36.7℃). The results of laboratory findings were as follows; WBC 6,800 /mm3, neutrophil 84% and CRP 0.11 mg/dL. Initial chest radiograph showed ill-defined infiltrates in both lower lung zones (Fig. 2A). On chest CT scans, lobar-distributed ill-defined consolidation and surrounding ground-glass opacities were noted in right middle lobe and left lower lobe (Fig. 2B, C). Real time RT-PCR was positive for novel influenza A (H1N1). The pneumococcal urine antigen assay was positive and gram-positive cocci were identified on sputum culture. Therefore, she was diagnosed to have a novel influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia with secondary pneumococcal pneumonia and treated with oseltamivir phosphate, levofloxacin and ceftriaxone. With five-day medication, symptoms improved and follow-up chest radiograph also showed improvement of infiltration in both lower lung zones.

Fig. 2.

42-year-old woman diagnosed as novel influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia with secondary pneumococcal pneumonia.

A. Initial chest radiograph shows ill-defined infiltrates in both lower lung zones.

B, C. Chest CT scans show lobar-distributed ill-defined consolidation and peripheral ground-glass opacities in right middle lobe and left lower lobe.

DISCUSSION

A new strain of triple-reassortant influenza A (H1N1) virus containing genes from swine, avian and human influenza viruses were identified in Mexico in April 2009, and then rapid spread of this pathogen has been observed over the world. According to the World Health Organization, pandemic influenza Phase 6 was declared on 11 June 2009, and over 296,471 cases were reported and at least 3,486 patients expired as related with this pathogen by 13 September 2009, (www.who.int/csr/don/2009_09_18). In Korea, more than 1,400 patients have been diagnosed including nine mortality cases by 21 September 2009 (www.cdc.go.kr).

During the early phase of this pandemic, there was a shift in the age distribution when compared with that of seasonal influenza virus. 87% of patients infected novel influenza A (H1N1) were between the ages of five and 50 years, and only 5% of patients were 51 years of age or older (1). This observation suggests that children and young adults may be more susceptible to novel influenza A (H1N1). The reason is proposed as a proportion of elderly people have some level of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies to the pandemic H1N1 virus (4). It is also possible that there is a case-ascertainment bias because more of the young people are tested as part of outbreaks in schools than elderly people (5).

The most common clinical manifestations of the novel influenza A (H1N1) are similar to the symptoms of seasonal influenza; fever (94%), cough (92%) and sore throat (66%), whereas diarrhea (25%) and vomiting (25%) are more common in the patients infected with the novel influenza A (H1N1) (1). The clinical outcomes are various from subclinical illness to severe outcomes such as respiratory failure and death, and are similar to that observed in cases with seasonal influenza viruses. The influenza virus infections may cause primary influenza viral pneumonia, lead to secondary bacterial pneumonia or exacerbate underlying chronic illness (6).

The chest radiographic findings described in a clinical report were bilateral patch alveolar opacities with basal lung predominance or interstitial opacities such as linear, reticular, or nodular shadows (2). However the CT findings have not yet been described, to the best of our knowledge. The common CT findings of viral pneumonia are known as poorly-defined air-space nodules and patchy areas of peribronchial ground-glass opacities and air-space consolidation. Rapid confluence of consolidation may occur in the progressive form of pneumonia. These findings are also common in the influenza virus pneumonia (7). The CT findings of first case, showing the ill-defined ground-glass opacity nodules and patch areas of ground-glass opacities, were thought to be typical pattern of viral pneumonia. On the other hand, the findings of second case, showing lobar-distributed consolidation and peripheral ground-glass opacities, were somewhat different from typical pattern of viral pneumonia and were thought to have combined component of bacterial lobar pneumonia.

In conclusion, we report two cases of novel influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia, focusing on radiologic findings including chest CT findings. The radiologists should be aware of the radiographic and CT findings of this viral infection so that the diagnosis of novel influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia should be considered promptly.

References

- 1.Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, Garten RJ, et al. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza a (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2605–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez-Padilla R, de la Rosa-Zamboni D, Ponce de Leon S, Hernandez M, Quinones-Falconi F, Bautista E, et al. Pneumonia and respiratory failure from swine-origin influenza a (H1N1) in Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:680–689. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowell G, Bertozzi SM, Colchero MA, Lopez-Gatell H, Alpuche-Aranda C, Hernandez M, et al. Severe respiratory disease concurrent with the circulation of H1N1 influenza. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:674–679. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hancock K, Veguilla V, Lu X, Zhong W, Butler EN, Sun H, et al. Cross-reactive antibody responses to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2009 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906453. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan H, Mosquera M, Nair H, France A. [ME1]Swine-origin influenza a (H1N1) virus infections in a school - New York City, April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:470–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiore AE, Shay DK, Broder K, Iskander JK, Uyeki TM, Mootrey G, et al. Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2008. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim EA, Lee KS, Primack SL, Yoon HK, Byun HS, Kim TS, et al. Viral pneumonias in adults: radiologic and pathologic findings. Radiographics. 2002;22:S137–S149. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.suppl_1.g02oc15s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]