Abstract

3-Methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolines (3-methyl-THIQs) are potent inhibitors of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), but are not selective due to significant affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor. Fluorination of the methyl group lowers the pKa of the THIQ amine from 9.53 (CH3) to 7.88 (CH2F), 6.42 (CHF2), and 4.88 (CF3). This decrease in pKa results in a reduction in affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor. However, increased fluorination also results in a reduction in PNMT inhibitory potency, apparently due to steric and electrostatic factors. Biochemical evaluation of a series of 3-fluoromethyl-THIQs and 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs showed that the former were highly potent inhibitors of PNMT, but were often non-selective due to significant affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor, while the latter were devoid of α2-adrenoceptor affinity, but also lost potency at PNMT. 3-Difluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs have the proper balance of both steric and pKa properties and thus have enhanced selectivity versus the corresponding 3-fluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs and enhanced PNMT inhibitory potency versus the corresponding 3-trifluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs. Using the “Goldilocks Effect” analogy, the 3-fluoromethyl-THIQs are too potent (too hot) at the α2-adrenoceptor and the 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs are not potent enough (too cold) at PNMT, but the 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs are just right. They are both potent inhibitors of PNMT and highly selective due to low affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor. This seems to be the first successful use of the β-fluorination of aliphatic amines to impart selectivity to a pharmacological agent while maintaining potency at the site of interest.

Introduction

Aliphatic amines are one of the most common functional groups in bioactive molecules2 and are often crucial in the binding of these compounds by acting as a hydrogen bond donor or acceptor, or through electrostatic interactions when protonated. Fluorine can strongly influence the basicity of aliphatic amines. For example, the incorporation of a monofluoromethyl, difluoromethyl, or trifluoromethyl group at the 3-position of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ, 1) lowers the pKa of the amine by approximately 1.5 log units per fluorine (Table 1). The decrease in pKa associated with the β-fluorination of aliphatic amines has been shown to have a profound effect on their biological properties. Some examples include increased substrate activity for lung N-methyltransferase,3 decreased inhibition of mitochondrial monoamine oxidase,4 increased N-dealkylation by CYP1A25 and decreased aromatic hydroxylation by CYP2D66,7 of fluorinated propranolol analogs, increased oral bioavailability,8 and changes in tissue distrubution.4, 9

Table 1.

The Effect of Fluorine on the pKa of THIQ.

pKa values (± 0.02) were determined by potentiometric titration by pION, Inc., Cambridge, MA.

Ref. 44.

Since the steric and pKa changes caused by fluorination can simultaneously affect multiple biological properties, it is not uncommon to observe that the added benefits of fluorination are accompanied by negative effects. A decrease in pKa that leads to enhanced oral absorption or improved metabolic properties may also result in a decrease in potency.10 While there are examples of varying the extent of fluorination to find an optimal pKa at which pharmacokinetic properties are improved and potency is maintained,8 this approach has not been used to impart selectivity to a pharmacological agent while maintaining potency at the site of interest.7,11

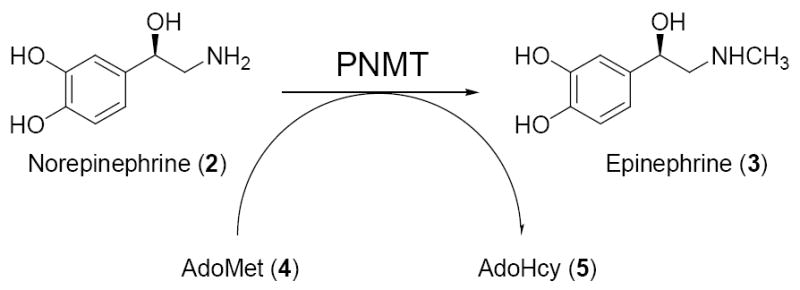

As one means of determining the function of epinephrine (3) in the CNS, our laboratory has targeted phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT; EC 2.1.1.28). This enzyme catalyzes the terminal step in the biosynthesis of epinephrine (3), in which an activated methyl group is transferred from S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet; 4) to the primary amine of norepinephrine (2) to form epinephrine (3) and the cofactor product S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (AdoHcy; 5).

The role of epinephrine (3) as a hormone in the periphery is well established. An acute stress response triggers the release of epinephrine (3) into the blood stream, which initiates the physiological changes associated with the “fight or flight syndrome”. In contrast to the vast understanding of the functions of epinephrine (3) in the periphery, its role in the CNS is much less clear. Significant levels of epinephrine (3) are present in the mammalian CNS,12-14 where it is postulated to act as a neurotransmitter. The most thoroughly studied physiological process to which epinephrine (3) in the CNS (central epinephrine) has been linked is the regulation of peripheral blood pressure. Administration of the PNMT inhibitor SK&F 6413915 (6, Table 2) to hypertensive rats resulted in a reduction in peripheral blood pressure.16 However, 6 also showed significant affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor.17 Thus, some of the decrease in peripheral blood pressure may be attributed to an α2-adrenergic effect rather than to decreases in central epinephrine concentrations.18-20 Selective inhibitors of PNMT would be useful pharmacological tools for clearly defining the connection between central epinephrine concentrations and peripheral blood pressure.

Table 2.

In Vitro Human PNMT (hPNMT) and α2-adrenoceptor Affinity of Some PNMT Inhibitors.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (μM) ± SEMa | ||||||

| Compd | R7 | R8 | R3 | hPNMT | α2b | Selectivity α2/hPNMT |

| 6c | Cl | Cl | H | 0.0031 ± 0.0006d | 0.021 ± 0.005 | 6.8 |

| 7e | Br | H | H | 0.056 ± 0.003f | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 4.1 |

| 8e | I | H | H | 0.093 ± 0.007g | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 2.4 |

| 9e | NO2 | H | H | 0.12 ± 0.01f | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 36 |

| 10g | SO2NH2 | H | H | 0.28 ± 0.02d | 100 ± 10 | 360 |

| 11ah | Br | H | CH2F | 0.023 ± 0.003f | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 280 |

| 11ci | Br | H | CF3 | 3.2 ± 0.3j | >1000 | >310 |

| 11df | Br | H | CH3 | 0.017 ± 0.005 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 65 |

THIQs having electron-withdrawing 7-substituents (either lipophilic or hydrophilic) are highly potent inhibitors of PNMT,21 and those with lipophilic electron-withdrawing 7-substituents, such as halides (7 and 8) are generally more potent than those having hydrophilic groups [9 and SK&F 2966122 (10)]. Unfortunately, THIQs bearing lipophilic electron-withdrawing 7-substituents also have significant affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor. Addition of a methyl (11d) or a fluoromethyl (11a) group to the 3-position of 7 provides a slight increase in PNMT inhibitory potency while decreasing affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor. While compounds 11d and 11a still have significant affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor, the 3-trifluoromethyl analog (11c) shows a dramatic reduction in α2-adrenoceptor affinity. Previous studies suggest that this is due to the large drop in pKa of the THIQ amine (pKa ≈ 5) making it mostly neutral at physiological pH. Unfortunately, 11c is not particularly potent at PNMT, showing a greater than 100-fold loss of potency versus 11d or 11a. This has been attributed to the increased steric bulk of the trifluoromethyl group.23,24

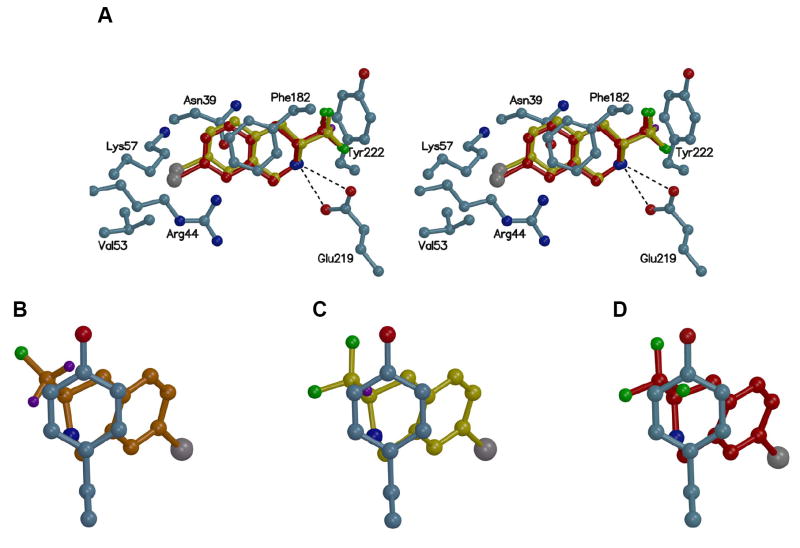

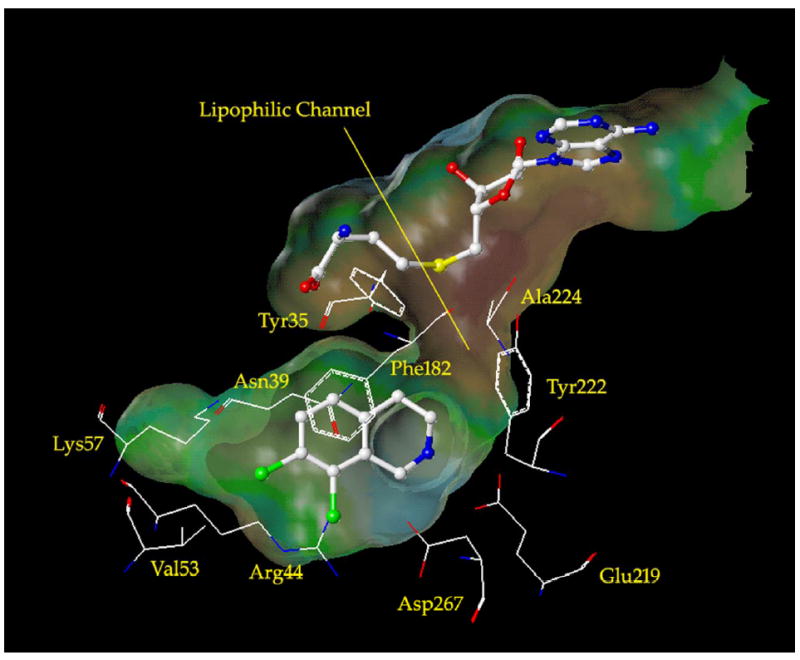

Analysis of the crystal structure of human PNMT (hPNMT) co-crystallized with inhibitors25-27 and substrates,28 coupled with site directed mutagenesis studies,27 has helped to identify the key amino acids at the hPNMT active site, some of which are shown in Figure 2. The aromatic rings of substrates or THIQ-type inhibitors are positioned between the side chains of Phe182 and Asn39. The β-hydroxyl of phenylethanolamine substrates or the amine of THIQ inhibitors interacts with Glu219 and Asp267. The substrate β-hydroxyl group interacts through hydrogen bonds, but it is currently unknown whether the THIQ amine interacts through hydrogen bonds in its neutral form or through an electrostatic interaction in its protonated form. We have co-crystallized hPNMT with inhibitors containing either a lipophilic (8)26 or hydrophilic (10)25 7-substituent. Lipophilic 7-subsituents interact with the side chains of Val53 and Arg44. Hydrophilic 7-substituents interact with Lys57 through hydrogen bonds.25 Examination of the hPNMT active site region surrounding the 3-position of co-crystallized THIQ inhibitors revealed the presence of a narrow lipophilic channel (Figure 2), which was consistent with THIQs having small 3-substituents (e.g., methyl, ethyl, or fluoromethyl) being more potent at PNMT than those having larger 3-substituents (e.g., isopropyl, butyl, pentyl, or trifluoromethyl). Docking studies with 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs showed that the trifluoromethyl group did not fit into the lipophilic channel due to negative steric interactions.24

Figure 2.

The active site of hPNMT co-crystallized with SK&F 64139 (6) and AdoHcy (5).27 A Connolly (solvent accessible) surface exposing 6 and 5 is also shown and indicates the presence of a lipophilic channel adjacent to the 3-position of 6. A lipophilic potential is mapped on the Connolly surface whereby the areas shown in green are neutral, blue are hydrophilic, and brown are lipophilic. Carbon is white, nitrogen is blue, oxygen is red, chlorine is green, and sulfur is yellow. Hydrogens are not shown for clarity.

We hypothesized that THIQs having a 3-substituent that (1) sufficiently lowers the pKa of the THIQ amine to diminish affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor, and (2) is small enough to maintain potency at PNMT would be an ideal inhibitor. We reasoned that 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs could meet these criteria because (1) the pKa of the THIQ amine is reduced below 6.5, and (2) docking studies indicated that the 3-difluoromethyl group would be able to fit into the lipophilic channel. Application of the “Goldilocks Effect”29 suggested that while the 3-fluoromethyl-THIQs were too potent (too hot) at the α2-adrenoceptor and the 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs were not potent enough (too cold) at PNMT, the 3-difluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs (11b–25b) would be just right—both highly potent at PNMT and highly selective due to low affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor.

Chemistry

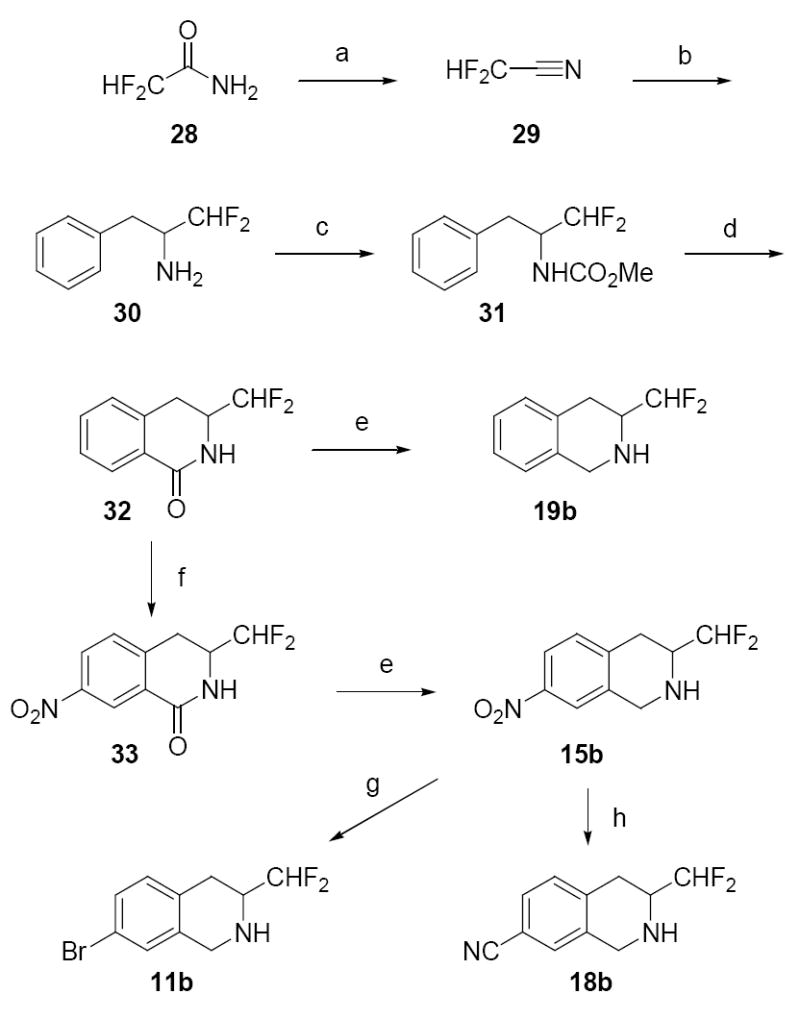

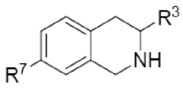

The synthesis of 3-difluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs 11b–25b and 7-(N-substituted aminosulfonyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs 14c, 17c, 23c, and 25c are shown in Schemes 1–4. While the synthesis of phenylpropylamine 30 has been reported previously (7 steps),30 a more direct route is reported here. Difluoroacetamide (28) was reacted in a P2O5 melt to form difluoroacetonitrile (29, Scheme 1).31 This highly volatile liquid was immediately reacted with benzylmagnesium chloride to form the iminium salt intermediate, which was then reduced in situ with NaBH4 to yield 30. Phenylpropylamine 30 was treated with methyl chloroformate in CH2Cl2 and pyridine to afford carbamate 31. Cyclization of 31 with polyphosphoric acid yielded lactam 32, the key intermediate in the synthesis of all of the 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs listed in Table 3. Reduction of 32 with diborane formed 3-difluoromethyl-THIQ (19b). Nitration of lactam 32 with sulfuric acid and potassium nitrate afforded the desired regioisomer, 33. Reduction of 33 with diborane yielded 15b, which was reduced to the aniline and converted to 11b via a Sandmeyer bromination reaction and to 18b by Greis cyanation.32

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) P2O5; (b) PhCH2MgCl, Et2O; then NaBH4, MeOH; (c) ClCO2Me, pyridine, CH2Cl2; (d) polyphosphoric acid; (e) BH3·THF; (f) H2SO4, KNO3; (g) H2, Pd/C, MeOH; then HBr, NaNO2, CuBr; (h) H2, Pd/C, MeOH; then HCl, NaNO2; then NaOH, KCN, NiSO4·6H2O, benzene.

Scheme 4.

Reagents and conditions: (a) amines, pyridine/CHCl3 or EtOAc/Na2CO3; (b) BH3·THF.

Table 3.

In Vitro Activities of 3-Mono-, Di-, and Trifluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs.

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R3= CH2F (a)a | R3= CHF2 (b)a | R3= CF3 (c)b | ||||||||

| Compd | R7 | PNMTc | α2c,d | Sele | PNMTc | α2c,d | Sele | PNMTc | α2c,d | Sele |

| 11a–c | Br | 0.023 | 6.4 | 280 | 0.094 | 230 | 2400 | 3.2 | >1000 | >310 |

| 12a–c | CF3 | 0.030 | 41 | 1400 | 0.067 | 190 | 2800 | 0.98 | >1000 | >1000 |

| 13a–c | I | 0.054 | 7.1 | 130 | 0.20 | >1000 | >5000 | 1.9 | >1000 | >530 |

| 14a–c | SO2NHCH2CF3 | 0.13 | 1200 | 9200 | 0.25 | >1000 | >4000 | 9.4 | >1000 | >110 |

| 15a–c | NO2 | 0.15 | 76 | 510 | 0.17 | >1000 | >5800 | 2.3 | 1400 | 610 |

| 16a–c | SO2NH2 | 0.15 | 680 | 4500 | 0.68 | >1000 | >1500 | 8.0 | >1000 | >125 |

| 17a–c | SO2NH(p-C6H4Cl) | 0.27 | 140 | 520 | 0.90 | >1000 | >1100 | 15 | >1000 | >67 |

| 18a–c | CN | 0.80 | 460 | 570 | 3.1 | >1000 | >320 | 21 | 2900 | 140 |

| 19a–c | H | 0.82 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 150 | 44 | 23 | 400 | 17 |

| 20a–c | SO2CH3 | 1.1 | 230 | 210 | 6.0 | 2500 | 420 | 41 | 3900 | 95 |

| 21a–c | SO2NHEt | 1.4 | 550 | 390 | 3.2 | >1000 | >310 | 60 | >1000 | >17 |

| 22a–c | SO2NHPr | 1.7 | 610 | 360 | 2.1 | >1000 | >480 | — | — | — |

| 23a–c | SO2NH(CH2)3OCH3 | 2.6 | 750 | 290 | 5.3 | >1000 | >190 | 13 | >1000 | >77 |

| 24a–c | SO2NHBu | 3.4 | 260 | 76 | 5.6 | >1000 | >180 | — | — | — |

| 25a–c | SO2NH(p-C6H4NO2) | 7.7 | >1000 | >130 | 37 | >1000 | >27 | 110 | >1000 | >9.1 |

Standard error of the mean was not greater than 10%.

In vitro activities for the inhibition of [3H]clonidine binding to the α2-adrenoceptor.

Selectivity α2 Ki /hPNMT Ki.

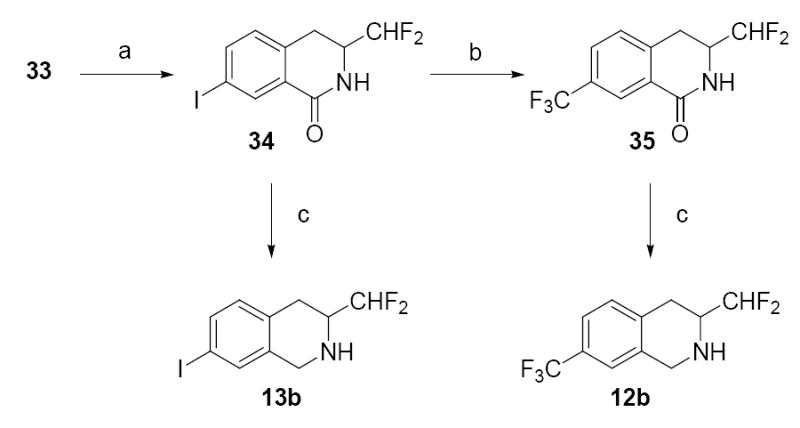

Lactam 33 was reduced to the aniline and then converted to lactam 34 via a Sandmeyer iodination reaction (Scheme 2).33 Treatment of 34 with FSO2CF2CO2CH3 and CuI in DMF yielded 35.34 Compounds 34 and 35 were reduced with diborane to yield THIQs 13b and 12b, respectively.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) H2, Pd/C, MeOH; then HCl, NaNO2, CuI, KI; (b) FSO2CF2CO2Me, CuI, DMF; (c) BH3·THF.

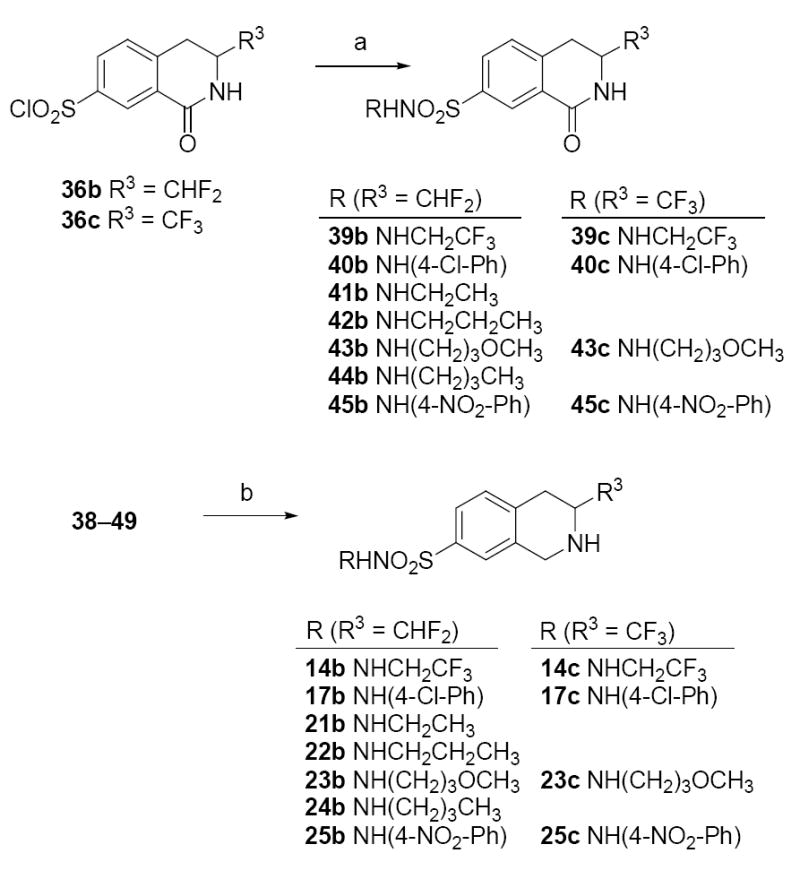

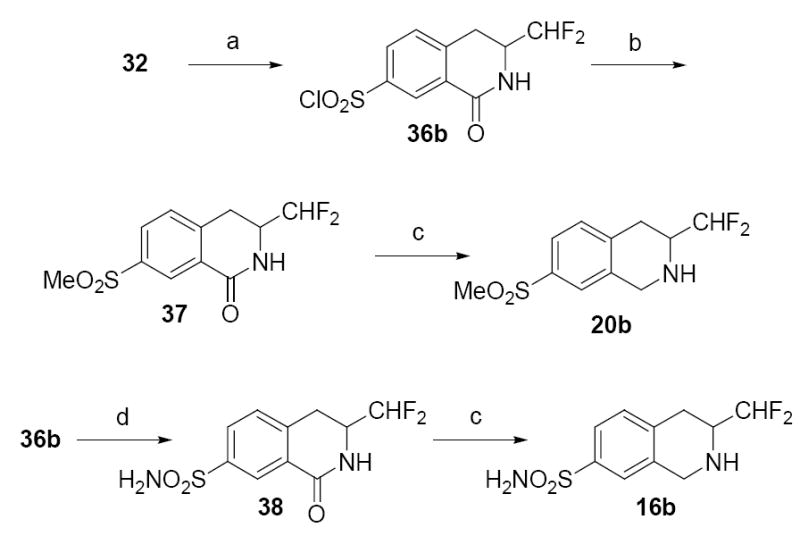

The sulfonyl chloride group was introduced exclusively to the 7-position by reacting lactam 32 with chlorosulfonic acid (Scheme 3). Compound 36b was then converted to the sulfonyl hydrazid, and reacted in situ with methyl iodide and sodium acetate in ethanol to form methyl sulfone 37,35 which was subsequently reduced with diborane to afford THIQ 20b. Sulfonyl chloride 36b was also treated with NH4OH in acetonitrile to produce aminosulfonyl 38, which was reduced with diborane to yield THIQ 16b.

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) ClSO3H; (b) NH2NH2, THF; then MeI, NaOAc, EtOH; (c) BH3·THF; (d) NH4OH, CH3CN.

Sulfonyl chloride 36b or 36c (which was prepared by previously described methods)23 was treated with the requisite amine in a either a solution of CHCl3 and pyridine for the synthesis of sulfonamides 39b, 40b, 45b, 39c, 40c, and 45c or a biphasic mixture of EtOAc and saturated sodium carbonate for the synthesis of sulfonamides 41b–44b and 43c (Scheme 4). These lactams were reduced with diborane to afford the corresponding 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs 14b, 17b, and 21b–25b and 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs 14c, 17c, 23c, and 25c.

Biochemistry

In the current study, human PNMT (hPNMT) with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag was expressed in E. coli.36, 37 The radiochemical assay conditions, previously reported for the bovine enzyme,38 were modified to account for the high binding affinity of some inhibitors.36,39 Inhibition constants were determined using four concentrations of phenylethanolamine as the variable substrate, and three concentrations of inhibitor.

α2-Adrenergic receptor binding assays were performed using cortex obtained from male Sprague Dawley rats.40 [3H]Clonidine was used as the radioligand to define the specific binding and phentolamine was used to define the nonspecific binding. Clonidine was used as the ligand to define α2-adrenergic binding affinity to simplify the comparison with previous results.

Results and Discussion

The biochemical data for the 3-difluoromethyl- (11b–25b) and the 3-trifluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs (14c, 17c, 23c, 25c) are shown in Table 3, along with previously reported data for selected 3-mono- and 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs. The pKa of the 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs (pKa ≈ 5.5–6.5)41 is lowered to a level at which affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor is drastically reduced. 7-Bromo-3-difluoromethyl-THIQ (11b) has 1000-fold less affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor than 7-bromo-THIQ (7, Table 2) and 35-fold less affinity than 7-bromo-3-fluoromethyl-THIQ (11a). Although the α2-adrenoceptor affinity of 7-bromo-3-difluoromethyl-THIQ (11b) is quite low, it does have greater, α2-adrenoceptor affinity than 7-bromo-3-trifluoromethyl-THIQ (11c, pKa ≈ 4.3)41 since a higher percentage of the former compound is protonated at physiological pH. This trend is consistent for all of the compounds in Table 3. At the α2-adrenoceptor, the rank order of affinity is CH2F > CHF2 > CF3.

At PNMT, previous studies have established that 3-fluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs are highly potent inhibitors,36, 42-44 while the corresponding 3-trifluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs are substantially, less potent.23, 24 The 3-difluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs were found to have PNMT inhibitory potencies that were quite similar to the corresponding 3-fluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs. This is especially evident for the most potent 3-fluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs (11a–17a), which have hPNMT Ki values of less than 300 nM. For these compounds, the corresponding 3-difluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs (11b–17b) have Ki values at PNMT ranging from statistically equipotent to 4-fold (average of 2.4-fold) less potent, whereas the corresponding 3-trifluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs (11c–17c) are between 15 and 140-fold (average of 58-fold) less potent. This data trend is consistent for all of the compounds in Table 3. At PNMT, the rank order of potency is CH2F ≈ CHF2 > CF3. The following sections analyze the data trends for the 3-mono-, di-, and trifluoromethyl-THIQs at the α2-adrenoceptor and PNMT.

α2-adrenoceptor

The 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs and 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs show a significant reduction in affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor relative to the corresponding 3-fluoromethyl-THIQs, indicating that either an increase in the size of the 3-substituent, a decrease in the pKa of the THIQ amine, or a combination of these factors is responsible for the reduction in α2-adrenoceptor affinity. In order to delineate between steric and pKa effects, the 7-bromo-THIQs (11a–c) and 7-nitro-THIQs (15a–c) were compared to 7-bromo- and 7-nitro-THIQs bearing increasingly larger alkyl groups on the 3-position (Table 4). Analysis of these data suggests that the steric bulk of the 3-substituent does not appear to significantly affect the affinity of THIQs for the α2-adrenoceptor. Despite considerable differences in the steric bulk of their 3-substituents [according to the Charton,45 Taft (Es),46 or Dubois (Es′)47 parameters], the 7-alkyl-3-bromo-THIQs (11d–f) and the 7-alkyl-3-nitro-THIQs (15d–f) have similar affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor.48 This evidence alone suggests that changes in steric bulk at the 3-position of THIQ are not affecting α2-adrenoceptor affinity. This is also supported by comparing the 3-fluoroalkyl-THIQs with the 3-alkyl-THIQs and is best illustrated by comparing the 3-isopropyl-THIQs (11f and 15f) and the 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs (11b and 15b). Isopropyl and difluoromethyl groups are geometrically similar, but the isopropyl group is considered to have steric bulk that is either approximately equal to or greater than that of the difluoromethyl group. If an increase in the steric bulk of the 3-substituent is the determining factor in lowering α2-adrenoceptor affinity, the 3-isopropyl analogs would be expected to have α2-adrenoceptor affinity that is either approximately equal to or less than that of the 3-difluoromethyl analogs. This is not the case. The 3-isopropyl-THIQs 11f and 15f have, respectively, 59 and > 28-fold more affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor than the 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs 11b and 15b. These data demonstrate that the reduced α2-adrenoceptor affinity of the 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs, and by extension the 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs, is likely a result of their reduced pKa values. It appears that the most pronounced reduction of α2-adrenoceptor affinity occurs somewhere between a pKa of approximately 8 and 6, the range between the 3-fluoromethyl-THIQs and the 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs.

Table 4.

In Vitro Activities of (±)-7-Nitro- and -7-Bromo-3-substituted-THIQs.

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (μM) ± SEMe | |||||||||

| Compd | R7 | R3 | Chartona | Es Taftb | Es′ Duboisc | pKad | PNMT | α2f | Selectivity α2/hPNMT |

| 11ag | Br | CH2F | 0.62 | −1.48 | 1.32 | 7.77 | 0.023h | 6.4 | 280 |

| 11b | Br | CHF2 | 0.68 | −1.91 | 1.44 | 6.12 | 0.094 | 230 | 2400 |

| 11ci | Br | CF3 | 0.91 | −2.40 | 1.90 | 4.33 | 3.2j | >1000 | >310 |

| 11dh | Br | CH3 | 0.52 | −1.24 | 1.12 | 9.29 | 0.017 | 1.1 | 65 |

| 11eh | Br | CH2CH3 | 0.56 | −1.31 | 1.20 | 9.44 | 0.48 | 1.2 | 2.5 |

| 11fh | Br | CH(CH3)2 | 0.76 | −1.71 | 1.43 | 9.59 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 0.89 |

|

| |||||||||

| 15ag | NO2 | CH2F | 0.62 | −1.48 | 1.32 | 7.45 | 0.15i | 76 | 510 |

| 15b | NO2 | CHF2 | 0.68 | −1.91 | 1.44 | 5.83 | 0.17 | >1000 | >5900 |

| 15ci | NO2 | CF3 | 0.91 | −2.40 | 1.90 | 4.06 | 2.3j | 1400 | 610 |

| 15dh | NO2 | CH3 | 0.52 | −1.24 | 1.12 | 8.95 | 0.072 | 31 | 430 |

| 15eh | NO2 | CH2CH3 | 0.56 | −1.31 | 1.20 | 9.11 | 0.49 | 28 | 57 |

| 15fh | NO2 | CH(CH3)2 | 0.76 | −1.71 | 1.43 | 9.27 | 4.6 | 36 | 7.9 |

Ref. 45.

Ref. 46.

Scaled to H = 0. Ref. 47.

pKa values were calculated using pKaPlugin from the JChem (version 3.1) software package (see ref. 41).

Standard error of the mean.

In vitro activities for the inhibition of [3H]clonidine binding to the α2-adrenoceptor

Ref. 44.

Ref. 48.

Ref. 23.

Ref. 24.

The α2-adrenonergic receptor data reported in this paper was obtained from the inhibition of [3H]clonidine binding to rat cortex α2-adrenoceptors. We recently evaluated a series of THIQs, which included 3-mono-, di- and trifluoromethyl-THIQs, for the inhibition of [3H]RX821002 binding to cloned human α2A-adrenergic receptors.49 The binding data for this series of THIQs showed good correlation (r2 = 0.90) between the inhibition of [3H]clonidine binding to rat cortex α2-adrenoceptors and the inhibition of [3H]RX821002 binding to cloned human α2A-adrenergic receptors. This correlation supports the use of structural models of the human α2A-adrenergic receptor to explain the α2-adrenoceptor data trends reported in this paper.

α2A-Adrenoceptors belong to the rhodopsin-like class of G-protein coupled receptors. Site directed mutagenesis studies and rhodopsin-based homology models have implicated an aspartate residue present in all G-protein coupled receptors as a key amino acid for ammonium ion binding.50,51 Numerous studies suggest that amine ligands for G-protein coupled receptors bind in their protonated form.50-52 Recent studies with the human HT1D receptor demonstrated that difluorination of amine ligands significantly lowers their binding affinity, apparently due to a reduction of protonated ligand at physiological pH.8 We expect that this same phenomenon is resulting in the low α2-adrenoceptor affinity of the 3-di- and 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs, which exist primarily in the neutral form at physiological pH. Mutagenesis studies52 and rhodopsin-based homology models53,54 of the human α2A-adrenoceptor predict that Asp113 provides an anchoring point for ligands containing a positively charged amine group. Structural models of the α2A-adrenoceptor predict that the positively charged amine of phenylethylamines and the positively charged nitrogen in the imidazoline ring of clonidine analogs interact electrostatically with Asp113.52 The low affinity of the 3-di- and 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs compared to 3-fluoromethyl- and 3-methyl-THIQs provides evidence that interaction between the protonated amine of THIQs and Asp113 is required for optimal α2A-adrenergic receptor affinity.

The binding of aliphatic amines that are primarily neutral at physiological pH to cationic ligand binding G-protein coupled receptors has not been thoroughly investigated. The results in this paper coupled with the previous study of fluorinated HT1D receptor ligands8 suggest that the fluorination of amine ligands for other G-protein coupled receptors may also result in reduced binding affinity. Since the key aspartate residue is highly conserved in all cationic ligand binding G-protein coupled receptors,50 lowering the pKa of amine ligands is likely to have a similar effect. Fluorination of amine ligands having undesired affinity for G-protein coupled receptors could be useful in the design of selective pharmacological agents.

PNMT

The rank order of PNMT inhibitory potency for the 3,7-disubstituted-THIQs in Table 3 is CH2F ≈ CHF2 > CF3. The 3-mono- and difluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs have similarly high inhibitory potency while the corresponding 3-trifluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs have drastically reduced inhibitory potency, which poses an interesting question. Why does a simple hydrogen to fluorine substitution result in only a slight change in going from the fluoromethyl series to the difluoromethyl, series, but has a profound effect when going from the difluoromethyl series to the trifluoromethyl series?

Structure-activity relationship studies on substituted benzylamines have found that electron-withdrawing aromatic substituents enhance PNMT inhibitory potency.55 The inverse relationship observed between the biochemical activity and the pKa of a series of benzylamines led to the hypothesis that the non-protonated form of benzylamine might be the active inhibitor species at PNMT.55 However, there were two obvious problems with this hypothesis. First, the strong correlation between the σ value of the aromatic substituent and the pKa of the benzylamines suggested that the electron-withdrawing substituents may facilitate the binding of benzylamines to PNMT not by lowering the pKa, but by promoting an interaction between an electron deficient aromatic ring and the PNMT active site. Analysis of the X-ray crystal structure of hPNMT co-crystallized with THIQ inhibitors (which are conformationally constrained benzylamines) indicates that a π stacking interaction between the aromatic ring of THIQs (and by extension benzylamines) and Phe182 may be source of the enhanced potency of inhibitors having electron-withdrawing aromatic substituents. Secondly, even in the most thorough study of substituted benzylamines, the pKa range was narrow and under the assay conditions (pH = 8.0) all of the compounds studied existed primarily as the protonated species.55

This study of 3-mono-, di- and trifluoromethyl-THIQs compares compounds having a broad range of pKa values significantly above and below the pH of the assay, and is thus superior for determining the ionization state in which these compounds bind. Compounds that are either protonated under the assay conditions, such as 3-methyl-THIQs 11d and 15d (Table 4), or are primarily neutral under the assay conditions, such as 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs 11b and 15b are highly potent inhibitors, indicating that THIQ inhibitors can bind to PNMT as either the protonated or neutral species. This is not inconsistent with the X-ray crystal structures of hPNMT that indicates that the THIQ amine could interact with Glu219 and Asp267 by either hydrogen bonding in its neutral form or through electrostatic interactions in its protonated form. The observed decrease in PNMT inhibitory potency of the 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs does not appear to be due to the fact that they are primarily neutral at physiological pH, since we do not observe a significant drop in the inhibitory potency of the 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs.

It is well established that an increase in steric bulk at the 3-position of THIQ results in a decrease in PNMT inhibitory potency,48 as illustrated by the biochemical results from a study of 7-bromo- and 7-nitro-THIQs having increasingly larger alkyl groups in the 3-position (Table 4, compounds 11d–f and 15d–f). However, when the 3-fluoroalkyl-7-substituted-THIQs (11a–c and 15a–c) are compared to the corresponding 3-alkyl-THIQs (11d–f and 15d–f), a correlation between the steric bulk of the 3-substituent [according to the Charton,45 Taft (Es),46 or Dubois (Es′)47 parameters] and PNMT inhibitory potency is not observed (Table 4).

Docking studies suggest that this is because these steric parameters measure size only, without taking the geometry of the group or the electrostatic properties of the 3-substituent into account. Analysis of 7-bromo-3-mono-, di-, and trifluoromethyl-THIQ (11a–c) docked into the active site of hPNMT (Figure 3) suggests that the interaction of the 3-substituents of 11a–c with Tyr222 dictates their relative potencies at hPNMT. The docking of 7-bromo-3-fluoromethyl-THIQ with hPNMT shows that the hydrogens on the fluoromethyl group are positioned in the face of Tyr222 while the fluorine is positioned away (Figure 3B). This result is supported by the co-crystallization of 14a and 17a with hPNMT, which show that the fluoromethyl groups of these compounds are positioned in the same manner as predicted by the docking study.56 A similar result is observed when 7-bromo-3-difluoromethyl-THIQ (11b) is docked into the active site of hPNMT (Figure 3C). The hydrogen of the difluoromethyl group is positioned in the face of Tyr222 while the two fluorines are positioned away.

Figure 3.

This figure shows 7-bromo-3-fluoromethyl-, difluoromethyl-, and trifluoromethyl-THIQ (11a–c) docked into the active site of hPNMT [from the hPNMT X-ray structure co-crystallized with AdoHcy (5) and SK&F 64139 (6)] and the amino acid residues that could interact with 11a–c. Nitrogen is blue, oxygen is red, bromine is gray, fluorine is green, carbons of amino acid side chains are cyan, carbons of 11a are orange, carbons of 11b are yellow, carbons of 11c are red, and hydrogens on the 3-substituents of 11a and 11b are purple. Other hydrogens are not shown for clarity. (A) This figure shows an overlay of 11b and 11c. 11a is not shown for clarity but the THIQ portion of 11a overlays almost identically with that of 11b. 11c is shifted approximately 0.3 Å away from Tyr222 relative to 11a and 11b.57 (B) This figure shows the interaction of 11a with Tyr222, the aromatic ring of which is shown in the plane of the paper. The hydrogens of the fluoromethyl group are positioned in the face of Tyr222 while the fluorine is moved away from Tyr222. (C) This figure shows the interaction of 11b with Tyr222, the aromatic ring of which is shown in the plane of the paper. The hydrogen of the difluoromethyl group is positioned in the face of Tyr222 while the two fluorine atoms are moved away from Tyr222. (D) This figure shows the interaction of 11c with Tyr 222, the aromatic ring of which is shown in the plane of the paper. One of the fluorine atoms is in the face of Tyr222.

When 7-bromo-3-trifluoromethyl-THIQ (11c) is docked into the active site of hPNMT, a negative steric interaction is observed between one of the fluorines and Tyr222 (Figure 3D), resulting in a translational shift of 11c in the binding pocket approximately 0.3 Å away from Tyr222,57 relative to 11a and 11b (Figure 3A). It is also likely that electrostatic repulsion between the partially negatively charged fluorine atom and the π cloud of Tyr222 is contributing to this move away from Tyr222. All of the X-ray crystal structures reported to date indicate that it is not energetically favorable for Tyr222 to change its position in order to avoid this negative interaction as its position in the active site is stabilized by a hydrogen bond with Tyr27 and hydrophobic interactions with Leu229 and Ala224.25-28 Docking studies of 3-mono-, di-, and trifluoromethyl-THIQs having various hydrophilic and lipophilic 7-substituents produced similar results to those obtained from the docking studies of the 7-bromo analogs in Figure 3. The 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs are shifted farther away from Tyr222 than the 3-mono- and difluoromethyl-THIQs. This is most likely preventing the THIQ amine of the 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs from making optimal interactions with Glu219. It is also possible that this shift in the active site could be preventing optimal π-stacking interactions between the aromatic ring of the 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs and Phe182. Clarification of this hypothesis awaits co-crystallization of 3-mono-, di-, and trifluoromethyl-THIQs having the same 7-substituent bound to hPNMT.

Conclusions

By varying the extent of fluorination on a series of highly potent, but nonselective 3-methyl-THIQ inhibitors of PNMT, we have dramatically increased their selectivity while maintaining their potency. This increase in selectivity (decrease in α2-adrenoceptor affinity) is apparently due to a decrease in the pKa of the THIQ amine resulting from β-fluorination and seems to be the first successful application of this approach for the design of selective pharmacological agents. Affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor is dependent on the extent of fluorination, thus the 3-difluoromethyl- and 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs have much less affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor than the 3-fluoromethyl-THIQs. However, increased fluorination also results in a reduction in PNMT inhibitory potency, apparently due to steric and electrostatic factors. 3-Difluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs have the proper balance of both steric and pKa properties and thus have enhanced selectivity versus the corresponding 3-fluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs and enhanced PNMT inhibitory potency versus the corresponding 3-trifluoromethyl-7-substituted-THIQs. The observed superiority of the 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs can be summed up with a simple porridge analogy from the fairytale Goldilocks and the Three Bears.29 While the 3-fluoromethyl-THIQs were too potent (too hot) at the α2-adrenoceptor and the 3-trifluoromethyl-THIQs were not potent enough (too cold) at PNMT, the 3-difluoromethyl-THIQs are just right. They are both highly potent at PNMT due to minimal negative steric interaction with Tyr222 and highly selective due to low affinity for the α2-adrenoceptor.

Experimental

All reagents and solvents were of reagent grade or were purified by standard methods before use. Melting points were determined in open capillary tubes on a Thomas-Hoover melting point apparatus calibrated with known compounds. Proton (1H NMR) and carbon (13C NMR) nuclear magnetic resonance spectra were taken on a Bruker DRX-400 or a Bruker AM-500 spectrophotometer. High resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained on a Ribermag R 10-10 mass spectrophotometer. Flash chromatography was performed using silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh) supplied by Universal Adsorbents, Atlanta, Georgia.

Anhydrous methanol and ethanol were used unless stated otherwise, and were prepared by distillation over magnesium. Other solvents were routinely distilled prior to use. Anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF) and diethyl ether (Et2O) were distilled from sodium-benzophenone ketyl. Hexanes refers to the mixture of hexane isomers (bp 40–70 °C) and brine refers to a saturated solution of NaCl. All reactions that required anhydrous conditions were performed under a positive nitrogen or argon flow, and all glassware was either oven-dried or flame-dried before use. [methyl-3H]AdoMet and [3H]clonidine were obtained from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA).

Radiochemical Assay of PNMT Inhibitors

A typical assay mixture consisted of 25 μL of 0.5 M phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 25 μL of 50 μM unlabeled AdoMet, 5 μL of [methyl-3H]AdoMet, containing approximately 3 × 105 dpm (specific activity approximately 15 Ci/mmol), 25 μL of substrate solution (phenylethanolamine), 25 μL of inhibitor solution, 25 μL of enzyme preparation (containing 30 ng hPNMT and 25 μg of bovine serum albumin), and sufficient water to achieve a final volume of 250 μL. After incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, the reaction mixture was quenched by addition of 250 μL of 0.5 M borate buffer (pH 10.0) and was extracted with 2 mL of toluene/isoamyl alcohol (7:3). A 1 mL portion of the organic layer was removed, transferred to a scintillation vial and diluted with cocktail for counting. The mode of inhibition was ascertained to be competitive in all cases reported in Tables 2-4 by examination of the correlation coefficients (r2) for the fit routines as calculated in the Enzyme Kinetics module (version 1.1) in SigmaPlot (version 7.0).32 While all Ki values reported were calculated using competitive kinetics, it should be noted that there was not always a great difference between the r2 values for the competitive model versus the non-competitive model. All assays were run in duplicate with 3 inhibitor concentrations over a 5-fold range. Ki values were determined by a hyperbolic fit of the data using the Single Substrate – Single Inhibitor routine in the Enzyme Kinetics module (version 1.1) in SigmaPlot (version 7.0). For inhibitors with apparent IC50 values less than 0.1 μM (as determined by a preliminary screen of the compounds to be assayed), the Enzyme Kinetics Tight Binding Inhibition routine was used to calculate the Ki values.

α2-adrenoceptor Radioligand Binding Assay

The radioligand receptor binding assay was performed according to the method of U’Prichard et al.29 Male Sprague-Dawley rats were decapitated, and the cortexes were dissected out and homogenized in 20 volumes (w/v) of ice-cold 50 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pH 7.7 at 25 °C). Homogenates were centrifuged thrice for 10 min at 50,000 × g with resuspension of the pellet in fresh buffer between spins. The final pellet was homogenized in 200 volumes (w/v) of ice-cold 50 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pH 7.7 at 25 °C). Incubation tubes containing [3H]clonidine (specific activity approximately 55 Ci/mmol, final concentration 2.0 nM), various concentrations of drugs and an aliquot of freshly resuspended tissue (800 μL) in a final volume of 1 mL were used. Tubes were incubated at 25 °C for 30 min and the incubation was terminated by rapid filtration under vacuum through GF/B glass fiber filters. The filters were rinsed with three 5 mL washes of ice-cold 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.7 at 25 °C). The filters were counted in vials containing premixed scintillation cocktail. Non-specific binding was defined as the concentration of bound ligand in the presence of 2 μM of phentolamine. All assays were run in quadruplicate with 5 inhibitor concentrations over a 16-fold range. IC50 values were determined by a log-probit analysis of the data and Ki values were determined by the equation Ki = IC50 / (1 + [Clonidine] / KD), as all Hill coefficients were approximately equal to 1.

Molecular Modeling

Connolly surfaces were generated in SYBYL® on a Silicon Graphics Octane workstation.58 Docking of the various inhibitors into the PNMT active site was performed using AutoDock 3.0.59 The default settings for AutoDock 3.0 were used. The compound to be docked was initially overlayed with the cocrystallized ligand SK&F 64139 (6) and minimized with the Tripos force field. The docking of inhibitors into the hPNMT active site was performed on the R-enantiomer as a previous study on 3-substituted-THIQs indicated that the R-enantiomer is preferred over the S-enantiomer in the hPNMT active site.60 Figure 3 was drawn with Molscript61 and Raster3D.62

(±)-Methyl N-(1-difluoro-3-phenyl-prop-2-yl) carbamate (31)

Difluoroacetonitrile (29) was prepared according to a procedure reported by Swarts.31 Difluoroacetamide (28, 2.30g, 24.2 mmol) and P2O5 (5.00 g, 17.6 mmol) were stirred to a homogeneous mixture in a 50 mL RB flask equipped with a short path distillation head. Et2O (5 mL) was placed in the collection flask, which was cooled to −78 °C. The product (29) boils at 22 °C, so a tygon tube was fitted to the end of the distillation head and connected to a pipet to bubble the product directly into the Et2O in the collection bulb. This solution of difluoroacetonitrile (29) in Et2O was diluted with additional Et2O (15 mL) and warmed to −40 °C. A solution of 1M benzylmagnesium chloride in Et2O (27.0 mL, 27.0 mmol) was added dropwise over 30 min. The solution was stirred for 30 min at −40 °C and then allowed to warm to −20 °C and stirring was continued for 1.5 h. A grey precipitate (iminium salt) formed and the reaction mixture was transferred to a solution of NaBH4 (1.51 g, 40.0 mmol) in MeOH (100 mL) and H2O (1 mL) at −20 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at −20 °C for 1 h and at 0 °C for an additional 1 h. 3N HCl (10 mL) was slowly added to the reaction mixture, which was then concentrated to approximately 20 mL. 3N HCl (30 mL) was added and the acidic aqueous mixture was washed with Et2O (2 × 100 mL). The aqueous solution was made basic with 4N NaOH and extracted with Et2O (4 × 75 mL). The combined organic extracts from the basic aqueous solution were washed with brine and dried over anhydrous K2CO3. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield crude 1,1-difluoro-3-phenyl-2-aminopropane (30) as a dark oily residue (1.12 g, 6.54 mmol.): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.4–7.28 (m, 5H), 5.71–5.41 (m, 1H), 3.35–3.15 (m, 1H), 3.00–2.59 (m, 2H). This crude product was dissolved in dry CH2Cl2 (25 mL) and pyridine (5 mL) and the solution was cooled to 0 °C. Methyl chloroformate (0.61 mL, 7.9 mmol) was added dropwise and the solution was stirred overnight at ambient temperature. Thin layer chromatography in hexanes/acetone (1:1), with visualization by ninhydrin staining, showed the presence of starting material so an additional aliquot of methyl chloroformate (0.40 mL, 5.2 mmol) was added and the reaction was stirred for 4 h at ambient temperature. Ice-cold water (25 mL) was added and the mixture was stirred for 30 min. The mixture was washed with 3N HCl (3 × 30 mL) and brine (30 mL). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield a yellow oil. The oil was purified by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (6:1) followed by recrystallization from EtOAc/hexanes to yield 31 as white crystals (1.26 g, 5.50 mmol, 23% from 28): mp 83–85 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.36–7.23 (m, 5H), 5.83 (t, J = 55.7 Hz, 1H), 4.84 (b, 1H), 4.26 (b, 1H), 3.65 (s, 3H), 3.05–2.82 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 156.9, 136.2, 129.5, 129.2, 127.5, 114.9 (t, J = 245 Hz), 54.2 (t, J = 45 Hz), 52.9, 34.4; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C11H14F2NO3 (MH+) 230.0993, obsd 230.0991.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (32)

Carbamate 31 (1.40 g, 6.11 mmol) was dissolved in polyphosphoric acid (PPA, 25 g) and heated to 120 °C. After stirring for 2 h, the reaction was poured onto ice water (100 mL) and stirred vigorously for 5 min. This aqueous mixture was extracted with EtOAc (4 × 50 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with water (50 mL) and brine (50 mL) and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed to yield an off-white solid, which was purified by flash chromatography eluting with EtOAc/hexanes (1:1) followed by recrystallization from hexanes to yield 32 as white crystals (840 mg, 4.26 mmol, 70%): mp 98–100 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.53–7.49 (m, 1H), 7.42–7.38 (m, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (b, 1H), 5.88–5.59 (m, 1H), 3.96 (b, 1H), 3.31–3.06 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.2, 135.9, 133.3, 128.5, 128.4, 128.1, 128.0, 115.3 (t, J = 245 Hz), 53.1 (t, J = 25 Hz), 27.5 (t, J = 2.4 Hz); HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C10H10F2NO (MH+) 198.0730, obsd 198.0759.

General Procedure for Lactam Reduction. Synthesis of 11b–25b, 14c, 17c, 23c, and 25c (Selected procedure for 19b)

Lactam 32 (130 mg, 0.66 mmol) was dissolved in THF (10 mL) and 1M BH3·THF (4.4 mL, 4.4 mmol) was added. The solution was heated to reflux for 4 h, cooled to ambient temperature, and MeOH (15 mL) was added dropwise. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and to the remaining residue a solution of MeOH (15 mL) and 6N HCl (15 mL) was added. The mixture was heated to reflux for 3 h and the MeOH was removed under reduced pressure. Water (25 mL) was added to the mixture, which was then made basic (pH ≈ 10) with 10% NaOH. The basic solution was extracted with CH2Cl2 (4 × 30 mL) and the combined organic extracts were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield the free amine, which often required purification by flash chromatography eluting with EtOAc/hexanes. The free amine was dissolved in CH2Cl2 or Et2O and dry HCl(g) or HBr(g) was bubbled through the solution to form the hydrochloride or hydrobromide salt, which was recrystallized from MeOH/CH2Cl2, EtOH/Et2O or EtOH/hexanes.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahyrdoisoquinoline hydrochloride (19b·HBr)

The hydrobromide salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 19b·HBr as white crystals (122 mg, 0.46 mmol, 70%). mp 242–244 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.37–7.29 (m, 4H), 6.51–6.29 (m, 1H), 4.59–4.49 (m, 1H), 4.22–4.11 (m, 2H), 3.34–3.18 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 129.4, 128.8, 128.1, 127.2, 127.1, 126.2, 113.6 (t, J = 244 Hz), 54.4 (t, J = 22 Hz), 44.9, 24.5 (t, J = 4.0 Hz); HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C10H12F2N (MH+) 184.0938, obsd 184.0931. Anal. (C10H12BrF2N) C, H, N.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-nitro-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (33)

Lactam 32 (560 mg, 2.84 mmol) was dissolved in concentrated H2SO4 (8 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. Potassium nitrate (314 mg, 3.12 mmol) was added in small portions to the solution, which was stirred overnight at ambient temperature. The mixture was poured slowly onto ice (50 g) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (4 × 40 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (3:1). Recrystallization from CHCl3/hexanes yielded 33 as light yellow crystals (520 mg, 2.15 mmol, 76%). mp 199–201 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.45 (b, 1H), 8.25–8.23 (m, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 5.92–5.69 (m, 1H), 3.96–3.88 (m, 1H), 3.34–3.15 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.8, 147.2, 143.2, 130.0, 129.1, 126.5, 122.5, 115.0 (t, J = 246 Hz), 51.5 (t, J = 24 Hz), 26.2; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C10H9F2N2O3 (MH+) 243.0581, obsd 243.0573.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (15b·HCl)

Compound 33 (490 mg, 2.02 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 15b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The crude amine was purified by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (1:1). The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 15b·HCl as white crystals (382 mg, 1.44 mmol, 72%): mp 102–104 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.44 (b, 1H), 8.28 (s, 1H), 8.16–8.14 (m, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.70–6.43 (m, 1H), 4.57–4.47 (m, 2H), 4.24–4.18 (m, 1H), 3.36–3.13 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 146.6, 138.8, 131.1, 130.8, 122.6, 122.3, 114.1 (t, J = 243 Hz), 52.8 (t, J = 24 Hz), 44.4, 24.8; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C10H11F2N2O2 (MH+) 229.0788, obsd 229.0781. Anal. (C10H11ClF2N2O2) C, H, N.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-bromo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (11b·HCl)

THIQ 15b·HCl (109 mg, 0.413 mmol) in dry EtOH (20 mL) was hydrogenated over 10% Pd/C (50 mg) for 2.5 h at 50 psi. The suspension was filtered through Celite and washed with EtOH. This solution was evaporated to dryness to yield the crude aniline, which was dissolved in a solution of 48% HBr (1.0 mL) and water (3.0 mL). A solution of sodium nitrite (32.0 mg, 0.464 mmol) and water (1 mL) was added dropwise to the HBr solution. After 30 min, excess HNO2 was destroyed by the addition of urea (25 mg). The diazonium salt solution was added to a mixture of copper(I) bromide (180 mg, 1.25 mmol), 48% HBr (2.5 mL) and water (5.0 mL). The reaction was warmed to 75–80 °C and was stirred for 1.5 h. The reaction was stirred overnight at ambient temperature and then cautiously made basic with a 50% NaOH. The formation of blue copper salts was observed at this time. Ethyl acetate (50 mL) was added and the resulting solution was filtered through Celite and washed with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL). The organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine and dried over anhydrous K2CO3. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield a dark oil which was purified by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (1:1). The free amine was dissolved in Et2O and dry HCl (g) was bubbled through the solution to form the hydrochloride salt, which was recrystallized from MeOH/Et2O to yield 11b·HCl as white crystals (86 mg, 0.29 mmol, 69%): mp 240–242 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.35 (b, 1H), 7.56 (s, 1H), 7.50–7.48 (m, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 6.68–6.40 (m, 1H), 4.42–4.32 (m, 2H), 4.17–4.09 (m, 1H), 3.14–2.96 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 131.6, 131.4, 130.8, 130.1, 129.6, 120.0, 114.2 (t, J = 243 Hz), 53.0 (t, J = 22 Hz), 44.1, 24.1; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C10H11BrF2N (MH+) 262.0043, obsd 262.0035. Anal. (C10H11BrClF2N) C, H, N.

(±)-3-Fluoromethyl-7-cyano-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrobromide (18b·HBr)

THIQ 15b·HCl (150 mg, 0.548 mmol) in dry EtOH (20 mL) was hydrogenated over 10% Pd/C (50 mg) for 2.5 h at 50 psi. The suspension was filtered through Celite and washed with EtOH. This solution was evaporated to dryness to yield the crude aniline, which was dissolved in a solution of concentrated HCl (1.6 mL) and water (2 mL) and cooled in an ice bath. A solution of sodium nitrite (41.5 mg, 0.601 mmol) in water (2 mL) was added dropwise. After 30 min, excess HNO2 was destroyed by the addition of urea (20 mg). In a separate flask, a solution of NaOH (66 mg) in water (1 mL) and KCN (179 mg) water (5 mL) was prepared. Benzene (5 mL) was added to the basic KCN solution and the suspension was cooled to 0 °C. A solution of Ni2SO4·6H2O (143 g, 0.55 mmol) and water (1.5 mL) was added to the basic KCN solution and the color of the solution changed to yellow-brown. The diazonium salt solution was added dropwise to this yellow-brown solution. Brisk evolution of N2 was observed and the reaction mixture was allowed to warm to ambient temperature over a period of 2 h. The mixture was warmed to 50 °C for 1 h, cooled to ambient temperature, made basic with 10% NaOH, and filtered through Celite. The Celite was washed with CH2Cl2 (2 × 100 mL). The organic phase was removed and the aqueous filtrate was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine and dried over anhydrous K2CO3. Removal of the solvent yielded a dark oil which was purified by flash chromatography eluting with EtOAc/hexane (5:1) to yield 18b as a pale brown solid. The free amine was dissolved in Et2O and dry HBr(g) was bubbled through the solution to form the hydrobromide salt, which was recrystallized from MeOH/Et2O to yield 18b·HBr as off-white crystals (31.1mg, 0.107 mmol, 20%) mp 246–248 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.76 (b, 1H), 7.83 (s, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.63–6.36 (m, 1H), 4.50–4.41 (m, 2H), 4.24–4.17 (m, 1H), 3.30–3.03 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 136.6, 131.4, 131.0, 130.6, 130.6, 118.8, 114.3 (t, J = 243 Hz), 53.0 (t, J = 23 Hz), 44.5, 25.1; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C11H11F2N2 (MH+) 209.0890, obsd 209.0875. Anal. (C11H11BrF2N2) C, H, N.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-iodo-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (34)

Lactam 33 (900 mg, 4.56 mmol) in dry MeOH (75 mL) was hydrogenated over 10% Pd/C (120 mg) for 3.5 h at 50 psi. The suspension was filtered through Celite and evaporated to dryness to yield the aniline intermediate as an oily residue. CH2Cl2 (50 mL) was added to the oily residue and a white precipitate formed. A solution of concentrated HCl (1.6 mL) and water (2 mL) was added, which dissolved the precipitate. This biphasic mixture was cooled to 0 °C and a solution of sodium nitrite (282 mg, 4.09 mmol) in water (3 mL) was added. After stirring for 15 min, excess HNO2 was destroyed by the addition of urea (20 mg). The diazonium salt solution was added in small portions to a vigorously stirred biphasic mixture of CH2Cl2 (25 mL), Ki (1.30 g, 29.0 mmol), CuI (50 mg, 0.26 mmol) and water (8 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at ambient temperature. The resulting brown suspension was diluted with CH2Cl2 (75 mL). The aqueous phase was removed and the organic phase washed with 10% Na2S2O3(aq) (3 × 40 mL). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (3:1) and recrystallized from CHCl3/hexanes to yield lactam 34 as a white solid (950 mg, 2.94 mmol, 65%) mp 144–146 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.44 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.85–7.83 (m, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.84–5.61 (m, 1H), 4.02–3.91 (m, 1H), 3.25–3.02 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 163.7, 141.6, 137.0, 134.6, 129.5, 129.3, 114.7 (t, J = 246 Hz), 92,4, 52.6 (t, J = 25 Hz), 26.9 (t, J = 2.8 Hz); HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C10H9F2N2O3 (MH+) 323.9697, obsd 323.9669.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-iodo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (13b·HCl)

Compound 34 (490 mg, 2.02 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 13b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The crude amine was purified by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (3:1). The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from MeOH/Et2O to yield 13b·HCl as white crystals (112 mg, 0.324 mmol, 89%): mp dec 282–284 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.32 (b, 1H), 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.67–6.39 (m, 1H), 4.39–4.29 (m, 2H), 4.16–4.07 (m, 1H), 3.11–2.95 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 136.5, 135.4, 131.6, 131.4, 130.4, 114.2 (t, J = 243 Hz), 92.7, 53.0 (t, J = 24 Hz), 43.8, 24.2; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C10H11F2IN (MH+) 309.9904, obsd 309.9901. Anal. (C10H11ClF2IN) C, H, N.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-trifluoromethyl-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (35)

To a solution of 34 (370 mg, 1.15 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) was added methyl 2,2-difluoro-2-(fluorosulfonyl) acetate (0.32 mL, 2.5 mmol) and CuI (252 mg, 1.32 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 5 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite, which was washed with CH2Cl2 (2 × 25 mL). The filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by flash chromatography eluting with CH2Cl2/Et2O (3:1) to give a mixture of 34 and 35. The mixture was separated by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (3:1) to yield 35 as a white solid (177 mg, 0.67 mmol 58%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.40 (s, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (b, 1H), 5.90–5.61 (m, 1H), 4.08–3.96 (m, 1H), 3.39–3.15 (m, 2H); HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C11H9F5NO (MH+) 266.0604, obsd 266.0598.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-trifluoromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (12b·HCl)

Compound 35 (490 mg, 2.02 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 12b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The crude amine was purified by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (3:1). The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from MeOH/Et2O to yield 13b·HCl as white crystals (125 mg, 0.435 mmol, 82%): mp 248–250 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.38 (b, 1H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.69–6.42 (m, 1H), 4.46 (s, 2H), 4.26–4.13 (m, 1H), 3.28–3.10 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 137.2, 136.2, 130.3, 129.1 (q, J = 32.4 Hz), 124.5 (q, J = 272 Hz), 123.6 (q, J = 3.6 Hz), 123.4 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 117.1 (t, J = 243 Hz), 55.3 (t, J = 23 Hz), 47.8, 27.7 (t, J = 3.7 Hz); HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C11H11F5N (MH+) 252.0812, obsd 252.0809. Anal. (C11H11ClF5N) C, H, N.

(±)-7-Chlorosulfonyl-3-difluoromethyl-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (36b)

Lactam 32 (1.00 g, 5.07 mmol) was treated with chlorosulfonic acid (10 mL) and heated to 50 °C for 16 h. The solution was cooled and carefully added via pipet onto ice (100 mL). A white precipitate formed. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield a light brown residue, which was purified by flash chromatography eluting with EtOAc to yield a white solid. Recrystallization from EtOAc/hexanes yielded 36b as white crystals (1.05 g, 3.55 mmol, 70%) mp 165–167 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3 δ 8.79 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.18–8.16 (m, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (b, 1H), 5.94–5.65 (m, 1H), 4.15–4.02 (m, 1H), 3.46–3.17 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.0, 144.5, 137.8, 129.6, 128.4, 127.7, 125.1, 115.2 (t, J = 245 Hz), 51.6 (t, J = 24 Hz), 26.2; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C10H9ClF2NO3S (MH+) 295.9960, obsd 295.9957.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-methylsulfonyl-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (37)

Sulfonyl chloride 36b (228 mg, 0.77 mmol) was dissolved in THF (10 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. Hydrazine (0.072 mL, 2.32 mmol) was added dropwise to the solution, which was stirred overnight at ambient temperature. The solution was cooled to 0 °C and a white precipitate (hydrazidosulfone) was collected by filtration. The precipitate was dissolved in EtOH (5 mL), then NaOAc (0.316 g, 3.85 mmol) and iodomethane (0.240 mL, 3.85 mmol) were added. The mixture was heated at reflux overnight. Water (30 mL) was added and the solution was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 40 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield a white solid, which was recrystallized from EtOAc/hexane to yield 37 as white needles (150 mg, 0.55 mmol, 71%) mp 215–217 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3 δ 8.68 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.12–8.10 (m, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.27 (b, 1H), 5.88–5.65 (m, 1H), 4.06–4.01 (m, 1H), 3.42–3.19 (m, 2H), 3.12 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 163.0, 141.0, 140.6, 131.1, 129.2, 128.9, 127.6, 114.5 (t, J = 246 Hz), 52.5 (t, J = 24 Hz), 44.2, 27.3; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C11H11F2NO3S (MH+) 276.0506, obsd 276.0492.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-methylsulfonyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (20b·HCl)

Compound 37 (150 mg, 0.55 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 20b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The crude amine was purified by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (3:2). The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 20b·HCl as white crystals (120 mg, 0.40 mmol, 74%): mp 243–245 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.32 (b, 1H), 7.92 (s, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.69–6.42 (m, 1H), 4.53–4.45 (m, 2H), 4.24–4.16 (m, 1H), 3.30–3.11 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 139.8, 136.8, 130.5, 130.5, 126.2, 125.8, 114.2 (t, J = 243 Hz), 52.9 (t, J = 23 Hz), 44.5, 43.9, 24.8; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C11H14F2NO2S (MH+) 262.0713, obsd 262.0695. Anal. (C11H14ClF2NO2S) C, H, N.

(±)-7-Aminosulfonyl-3-difluoromethyl-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (38)

Sulfonyl chloride 36b (200 mg, 0.68 mmol) was dissolved in acetonitrile (5 mL), concentrated ammonium hydroxide (5 mL) was added, and the reaction was stirred overnight at ambient temperature. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was partitioned between water (50 mL) and EtOAc (50 mL). The organic layer was removed and the aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (2 × 30 mL). The organic layers were pooled, washed with brine, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the resulting oil was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 38 as white crystals (180 mg, 0.65 mmol, 96%): mp 205–207 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.49 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.04–8.02 (m, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.01–5.78 (m, 1H), 4.88 (s, 1H), 4.06–4.00 (m, 1H), 3.46–3.20 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 164.5, 143.0, 140.6, 129.5, 128.6, 128.3, 124.8, 115.3 (t, J = 244 Hz), 51.5 (t, J = 24 Hz), 25.8 (t, J = 3.8 Hz); HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C10H11F2N2O3S (MH+) 277.0458, obsd 277.0456.

(±)-7-Aminosulfonyl-3-difluoromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (16b·HCl)

Compound 38 (150 mg, 0.55 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 16b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The crude amine was purified by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (3:2). The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 16b·HCl as white crystals (120 mg, 0.40 mmol, 74%): mp dec 239–242 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.30 (b, 1H), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (b, 2H), 6.67–6.45 (m, 1H), 4.47 (s, 2H), 4.24–4.14 (m, 1H), 3.32–3.09 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 143.1, 134.7, 130.0, 129.8, 125.1, 124.2, 114.2 (t, J = 243 Hz), 53.0 (t, J = 24 Hz), 44.5, 24.6; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C10H13F2N2O2S (MH+) 263.0666, obsd 263.0668. Anal. (C10H13ClF2N2O2S) C, H, N.

General Procedure for the Preparation of Compounds 39b, 40b, 45b, 39c, 40c, and 45c

Sulfonyl chloride 36b or 36c (between 0.25 and 1.0 mmol) was dissolved in CHCl3 (20 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. The requisite amine (3 equivalents) and pyridine (3 equivalents) were dissolved in CHCl3 (2 mL) and added dropwise to the sulfonyl chloride solution. The reaction was stirred for 12 h at ambient temperature and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was dissolved in EtOAc (50 mL) and this solution was washed with 3 N HCl (2 × 30 mL) and brine (30 mL), and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield the crude product, which was purified by flash chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (if required), followed by recrystallization from EtOAc/hexanes or EtOH/hexanes.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(N-2,2,2-trifluoroethylaminosulfonyl)-3,4,-dihydroisoquinolin-1(2H)-one (39b)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36b (170 mg, 0.58 mmol) was converted to 39b (140 mg, 0.39 mmol, 68%): mp 208–210 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.43 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.01–7.99 (m, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.02–5.79 (m, 1H), 4.07–4.00 (m, 1H), 3.67 (q, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 3.46–3.22 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 164.3, 141.4, 140.2, 130.1, 128.9, 128.6, 125.4, 124.0 (q, J = 278 Hz), 115.2 (t, J = 244 Hz), 51.5 (t, J = 24 Hz), 43.5 (q, J = 35 Hz), 25.8 (t, J = 3.9 Hz); HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C12H12F5N2O3S (MH+) 359.0489, obsd 359.0485.

(±)-7-(N-2,2,2-Trifluoroethylaminosulfonyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-3,4,-dihydroisoquinolin-1(2H)-one (39c)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36c (100 mg, 0.32 mmol) was converted to 39c (85 mg, 0.23 mmol, 71%): mp 203–205 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.60 (s, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.36 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (q, J = 8.0, 2H), 3.57–3.28 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 165.6, 142.2, 142.0, 131.8, 130.0, 129.9, 127.0, 126.8 (q, J = 281 Hz), 125.6 (q, J = 281 Hz), 55.1 (q, J = 33 Hz), 45.1 (q, J = 35 Hz), 27.1.

(±)-7-(N-4-Chlorophenylaminosulfonyl)-3-difluoromethyl-3,4,-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (40b)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36b (200 mg, 0.68 mmol) was converted to 40b (245 mg, 0.63 mmol, 94%): mp 191–193 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) 8.36 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.86–7.84 (m, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.24–7.22 (m, 2H), 7.11–7.09 (m, 2H), 5.98–5.75 (m, 1H), 4.04–3.96 (m, 1H), 3.40–3.16 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 164.2, 141.6, 138.7, 136.1, 130.4, 129.8, 128.8, 128.8, 128.4, 125.7, 122.2, 115.2 (t, J = 244 Hz), 51.4 (t, J = 24 Hz), 25.8 (t, J = 3.8 Hz).

(±)-7-(N-4-Chlorophenylaminosulfonyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-3,4,-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (40c)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36c (300 mg, 0.960 mmol) was converted to 40c (325 mg, 0.81 mmol, 84%): mp 230–232 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.68 (s, 1H), 8.34 (br s, 1H), 7.83–7.81 (m, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 7.09 (d, = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 7.03 (br s, 1H), 4.33–4.22 (m, 1H), 3.48–3.17 (m, 2H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.4, 140.3, 139.3, 135.4, 132.0, 131.5, 129.8, 128.7, 128.6, 127.6, 124.8 (q, J = 282 Hz), 123.7, 52.4 (q, J = 32 Hz), 26.8; HRMS (FAB+) calcd for C16H13ClF3N2O3S (MH+) 405.0288, obsd 405.0286.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(N-4-nitrophenylaminosulfonyl)-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (45b)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36b (175 mg, 0.59 mmol) was converted to 45b (135 mg, 0.34 mmol, 57%): mp dec 192–194 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) 8.45 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.16–8.13 (m, 2H), 8.03–8.01 (m, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.35–7.32 (m, 2H), 5.98–5.75 (m, 1H), 4.05–3.95 (m, 1H), 3.41–3.16 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ.164.1, 143.7, 143.4, 142.1, 138.7, 130.4, 129.0, 128.7, 125.7, 124.7, 118.2, 115.2 (t, J = 244 Hz), 51.4, 25.8; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C16H14F2N3O5S (MH+) 398.0622, obsd 398.0624.

(±)-7-(N-4-Nitrophenylaminosulfonyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-3,4,-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (45c)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36c (300 mg, 0.96 mmol) was converted to 45c (370 mg, 0.89 mmol, 93%): mp 118–120 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.44–7.65(m, 4H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (m, 2H), 4.36 (m, 1H), 3.60–3.25 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 164.2, 142.5, 141.9, 131.6, 131.0, 129.3, 129.0, 127.0, 126.8 (q, J = 281 Hz), 126.1, 125.2, 118.7, 51.0 (q, J = 31 Hz), 26.0; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C16H12F3N3O5S (MH+) 416.0528, obsd 416.0536.

General Procedure for the Preparation of Compounds 41b–44b and 43c

Sulfonyl chloride 36b or 36c (between 0.5 and 1.0 mmol) was dissolved in a biphasic mixture of EtOAc (15 mL) and saturated Na2CO3 (10 mL). The requisite amine (3 equivalents) was added to the reaction, and the mixture was stirred for 4 h. The organic phase was removed, washed with 3 N HCl (3 × 50 mL) and brine (30 mL), and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield the crude product, which was purified by flash chromatography (if required) eluting with hexanes/EtOAc, followed by recrystallization from EtOAc/hexanes or EtOH/hexanes.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(N-ethylaminosulfonyl)-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (41b)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36b (180 mg, 0.61 mmol) was converted to 41b (160 mg, 0.53 mmol, 86%): mp 199–201 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.42 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.99–7.97 (m, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.02–5.79 (m, 1H), 4.08–3.98 (m, 1H), 3.46–3.21 (m, 2H), 2.93 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.08 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 164.4, 141.0, 140.0, 130.3, 128.8, 128.5, 125.5, 115.2 (q, J = 244 Hz), 51.5 (t, J = 24 Hz), 37.5, 25.8 (t, J = 3.9 Hz), 13.8; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C12H15F2N2O3S (MH+) 305.0771, obsd 305.0753.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(N-propylaminosulfonyl)-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (42b)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36b (180 mg, 0.61 mmol) was converted to 42b (155 mg, 0.49 mmol, 80%): mp 197–199 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.42 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.99–7.97 (m, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.02–5.79 (m, 1H), 4.07–3.99 (m, 1H), 3.46–3.21 (m, 2H), 2.84 (m, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.52–1.45 (m, 2H), 0.88 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 164.5, 140.9, 140.1, 130.2, 128.8, 128.4, 125.5, 115.3 (q, J = 244 Hz), 51.5 (t, J = 24 Hz), 44.4, 25.8 (t, J = 3.8 Hz), 22.5, 9.9; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C13H17F2N2O3S (MH+) 319.0928, obsd 319.0931.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(N-3-methoxypropylaminosulfonyl)-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (43b)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36b (180 mg, 0.61 mmol) was converted to 43b (185 mg, 0.53 mmol, 87%): mp 143–145 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.42 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.99–7.97 (m, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.02–5.79 (m, 1H), 4.08–4.00 (m, 1H), 3.46–3.21 (m, 2H), 3.39 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.28, (s, 3H), 2.96 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.73–1.68 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 164.4, 141.0, 139.9, 130.3, 128.8, 128.5, 125.5, 115.2 (q, J = 244 Hz), 69.2, 57.3, 51.5 (t, J = 24 Hz), 46.6, 29.2, 25.8 (t, J = 3.8 Hz); HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C14H19F2N2O4S (MH+) 349.1033, obsd 349.1047.

(±)-7-(N-3-Methoxypropylaminosulfonyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-3,4,-dihydroisoquinolin-1(2H)-one (43c)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36c (320 mg, 1.02 mmol) was converted to 43c (345 mg, 0.94 mmol, 92%): mp 146–147 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.49 (s, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.48–4.37 (m, 1H), 3.63–3.38 (m, 2H), 3.39–3.36 (m, 2H), 3.27 (s, 3H), 2.95 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.73–1.67 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 164.1, 140.4, 140.1, 130.6, 128.6, 128.4, 125.6, 124.7 (q, J = 283 Hz), 69.2, 57.4, 51.0 (q, J = 31 Hz), 39.8, 29.3, 25.6; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C14H18F3N2O4S (MH+) 367.0939, obsd 367.0943.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(N-butylaminosulfonyl)-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1-(2H)-one (44b)

According to the above procedure, sulfonyl chloride 36b (180 mg, 0.61 mmol) was converted to 44b (190 mg, 0.57 mmol, 94%): mp 194–196 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.41 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.99–7.97 (m, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.02–5.79 (m, 1H), 4.07–3.99 (m, 1H), 3.46–3.21 (m, 2H), 2.88 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.45–1.41 (m, 2H) , 1.34–1.30 (m, 2H), 0.88 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 164.5, 141.0, 140.0, 130.3, 128.8, 128.4, 125.5, 115.3 (q, J = 244 Hz), 51.5 (t, J = 24 Hz), 42.3, 31.3, 25.8 (t, J = 3.8 Hz), 19.2, 12.4; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C14H19F2N2O3S (MH+) 333.1084, obsd 333.1086.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(N-2,2,2-trifluoroethylaminosulfonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (14b·HCl)

Compound 39b (150 mg, 0.55 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 14b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 14b·HCl as white crystals (120 mg, 0.40 mmol, 74%): mp 202–204 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.84 (s, 2H), 7.84–7.83 (m, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (b, 2H), 6.53–6.31 (m, 1H), 4.63 (s, 2H), 4.26–4.18 (m, 1H), 3.69 (q J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 3.42–3.23 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 140.3, 134.8, 129.9, 128.6, 126.0, 124.9, 124.0 (q, J = 278 Hz), 113.4 (t, J = 244 Hz), 53.9 (t, J = 23 Hz), 44.6, 43.5 (q J = 35 Hz), 24.6 (t, J = 4.0 Hz); HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C12H14F5N2O2S (MH+) 345.0696, obsd 345.0687. Anal. (C12H14ClF5N2O2S) C, H, N.

(±)-7-(N-2,2,2-Trifluoroethylaminosulfonyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (14c·HCl)

Compound 39c (310 mg, 0.83 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 14c according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/Et2O to yield 14c·HCl as white crystals (200 mg, 0.51 mmol, 61%): mp dec 230–232 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.80–7.77 (m, 2H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.72–4.60 (m, 1H), 4.63 (s, 2H), 3.61 (q, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 3.50–3.32 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 142.3, 135.6, 131.8, 130.1, 128.0, 126.7, 125.9 (q, J = 280 Hz), 125.2 (q, J = 280 Hz), 55.3 (q, J = 33 Hz), 46.8, 45.4 (q, J = 35 Hz), 26.3; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C12H13F6N2O2S (MH+) 363.0602, obsd 363.0602; Anal. (C12H13ClF6N2O2S) C, H, N.

(±)-7-(N-4-Chlorophenylaminosulfonyl)-3-difluoromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (17b·HCl)

Compound 40b (180 mg, 0.47 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 17b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 17b·HCl as white crystals (150 mg, 0.37 mmol, 79%): mp dec 250–252 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.76–7.74 (m, 2H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.23–7.21 (m, 2H), 7.12–7.10 (m, 2H), 6.48–6.26 (m, 1H), 4.54 (s, 2H), 4.19–4.09 (m, 1H), 3.36–3.16 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 138.7, 136.1, 135.1, 129.9, 129.6, 128.8, 126.4, 125.4, 121.9, 113.4 (t, J = 244 Hz), 53.9 (t, J = 22 Hz), 44.6, 24.6; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C16H16ClF2N2O2S (MH+) 373.0589, obsd 373.0574. Anal. (C16H16Cl2F2N2O2S) C, H, N.

(±)-7-(N-4-Chlorophenylaminosulfonyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (17c·HCl)

Compound 40c (325 mg, 0.804 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 17c according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/Et2O to yield 17c·HCl as white crystals (288 mg, 0.67 mmol, 84%): mp 162–165 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6 δ 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.72–4.61 (m, 1H), 4.47–4.39 (m, 2H), 3.49 (b, 3H), 3.34–3.13 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6 δ 138.4, 137.0, 135.7, 130.8, 130.4, 129.6, 128.5, 125.8, 125.4, 124.1 (q, J = 282 Hz), 121.8, 52.6 (q, J = 32 Hz), 44.9, 25.2; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C16H15ClF3N2O2S (MH+) 391.0495, obsd 391.0468; Anal. (C16H15Cl2F3N2O2S) C, H, N.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(N-4-nitrophenylaminosulfonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (25b·HCl)

Compound 45b (115 mg, 0.29 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 25b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 25b·HCl as white crystals (83 mg, 0.20 mmol, 68%): mp dec 250–252 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.14–8.11 (m, 2H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.88–7.86 (m, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.35–7.33 (m, 2H), 6.49–6.28 (m, 1H), 4.60 (s, 2H), 4.22–4.12 (m, 1H), 3.38–3.17 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 143.8, 143.3, 138.6, 135.6, 130.1, 128.9, 126.4, 125.5, 124.7, 118.1, 113.3 (t, J = 244 Hz), 53.9 (t, J = 23 Hz), 44.5, 24.5; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C16H16F2N3O4S (MH+) 384.0830, obsd 384.0837. Anal. (C16H16ClF2N3O4S) C, H, N.

(±)-7-(N-4-Nitrophenylaminosulfonyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (25c·HCl)

Compound 45c (350 mg, 0.85 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 25c according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/Et2O to yield 25c·HCl as white crystals (210 mg, 0.48 mmol, 57%): mp 235–236 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.14–8.12 (m, 2H), 7.93–7.88 (m, 2H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.35–7.33 (m, 2H), 4.67–4.61 (m, 3H), 3.50–3.28 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 143.8, 143.4, 138.8, 134.7, 130.2, 128.6, 126.6, 125.6, 124.7, 123.3 (q, J = 279 Hz), 118.2, 53.2 (q, J = 32 Hz), 45.0, 24.5; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C16H15F3N3O4S (MH+) 402.0735, obsd 402.0723; Anal. (C16H15ClF3N3O4S·EtOH) C, H, N.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(ethylaminosulfonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (21b·HCl)

Compound 41b (140 mg, 0.46 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 21b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 21b·HCl as white crystals (146 mg, 0.45 mmol, 97%): mp 198–200 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.66–6.44 (m, 1H), 4.52–4.45 (m, 2H), 4.25–4.14 (m, 1H), 3.26–3.10 (m, 2H), 2.81–2.76 (m, 2H), 1.00 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 139.6, 135.3, 130.3, 130.2, 125.8, 125.3, 114.2 (t, J = 243 Hz), 53.0 (t, J = 24 Hz), 44.5, 37.9, 24.7, 15.2; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C12H17F2N2O2S (MH+) 291.0979, obsd 291.0956. Anal. (C12H17ClF2N2O2S) C, H, N.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(propylaminosulfonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (22b·HCl)

Compound 42b (140 mg, 0.44 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 22b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 22b·HCl as white crystals (135 mg, 0.40 mmol, 90%): mp 186–188 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.70–7.68 (m, 1H), 7.66 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.65–6.42 (m, 1H), 4.52–4.45 (m, 2H), 4.25–4.13 (m, 1H), 3.27–3.08 (m, 2H), 2.72–2.68 (m, 2H), 1.43–1.36 (m, 2H), 0.81 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 139.7, 135.2, 130.3, 130.2, 125.8, 125.3, 114.2 (t, J = 243 Hz), 53.0 (t, J = 24 Hz), 44.7, 44.6, 24.7, 22.8, 11.5; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C13H19F2N2O2S (MH+) 305.1135, obsd 305.1137. Anal. (C13H19ClF2N2O2S) C, H, N.

(±)-3-Difluoromethyl-7-(N-3-methoxypropylaminosulfonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (23b·HCl)

Compound 43b (160 mg, 0.46 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 23b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 23b·HCl as white crystals (150 mg, 0.40 mmol, 88%): mp 160–162 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.70–7.67 (m, 2H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.65–6.43 (m, 1H), 4.52–4.45 (m, 2H), 4.25–4.14 (m, 1H), 3.29 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.27–3.09 (m, 2H), 3.17 (s, 3H), 2.80–2.78 (m, 2H), 1.64–1.59 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 139.5, 135.3, 130.3, 130.2, 125.8, 125.3, 114.2 (t, J = 243 Hz), 69.3, 58.3, 53.0 (t, J = 24 Hz), 44.6, 29.6, 24.7; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C14H21F2N2O3S (MH+) 335.1241, obsd 335.1245. Anal. (C14H21ClF2N2O3S) C, H, N.

(±)-7-(N-3-Methoxypropylaminosulfonyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (23c)

Compound 43c (400 mg, 1.09 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 23c according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The free amine was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 23 as white crystals (297 mg, 0.84 mmol, 77%): mp 95–96 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.65 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (s, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 4.15–4.06 (m, 2H), 3.73–3.64 (m, 1H), 3.39 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.28 (s, 3H), 3.14–2.94 (m, 2H), 2.91 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.72–1.66 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 138.4, 137.2, 136.1, 129.6, 125.9 (q, J = 279 Hz), 124.5, 124.2, 69.3, 57.3, 54.3 (q, J = 29), 46.3, 39.7, 29.3, 26.8; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C14H20F3N2O3S (MH+) 353.1147, obsd 353.1136; Anal. (C14H19F3N2O3S) C, H, N.

(±)-7-(N-Butylaminosulfonyl)-3-difluoromethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrochloride (24b·HCl)

Compound 44b (175 mg, 0.53 mmol) was reduced to THIQ 24b according to the general procedure for lactam reduction. The hydrochloride salt was recrystallized from EtOH/hexanes to yield 24b·HCl as white crystals (170 mg, 0.48 mmol, 91%): mp 206–208 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.70–7.68 (m, 1H), 7.65 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.64–6.42 (m, 1H), 4.52–4.45 (m, 2H), 4.25–4.14 (m, 1H), 3.26–3.10 (m, 2H), 2.75–2.71 (m, 2H), 1.40–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.29–1.21 (m, 2H), 0.82 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 139.6, 135.2, 130.3, 130.2, 125.7, 125.3, 114.2 (t, J = 243 Hz), 53.0 (t, J = 23 Hz), 44.6, 42.6, 31.5, 24.7, 19.6, 13.9; HRMS (FAB+) m/z calcd for C14H21F2N2O2S (MH+) 319.1292, obsd 319.1297. Anal. (C14H21ClF2N2O2S) C, H, N.

Supplementary Material

All elemental analyses (C, H, N) for assayed compounds are included. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Figure 1.