Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To compare mortality, graft loss, and postoperative complications after liver transplant in older patients (≥70 years) with those in younger patients (<60 years).

PATIENTS AND METHODS: Outcomes for 42 patients aged 70 years or older who underwent liver transplant were compared with those of 42 matched controls younger than 60 years. All patients underwent transplants between March 19, 1998, and May 7, 2004. Information was collected on patient characteristics, comorbid conditions, laboratory results, donor and operative variables, medical and surgical complications, and mortality and graft loss.

RESULTS: Preoperative characteristics were similar across age groups, except for creatinine (P=.01) and serum albumin (P=.03) values, which were higher in older patients, and an earlier year of transplant in younger patients (P<.001). Intraoperatively, older patients required more erythrocyte transfusions (P=.04) and more intraoperative fluids (P=.001) than did younger patients. Postoperatively, bilirubin level (P=.007) and international normalized ratios (P=.01) were lower in older patients, whereas albumin level was higher (P<.001). The median follow-up was 5.1 years (range, 0.1-8.5 years). Compared with younger patients, older patients were not at an increased risk of death (relative risk, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.43-2.31; P>.99) or graft loss (relative risk, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 0.54-2.52; P=.70). The frequency of other complications did not differ significantly between age groups, although older patients had more cardiovascular complications.

CONCLUSION: Five-year mortality and graft loss in older recipients were comparable with those in younger recipients, suggesting that age alone should not exclude older patients from liver transplant.

At a median follow-up of 5 years, this study found that older patients were not at an increased risk of death or graft loss compared with younger patients. The frequency of other complications did not differ significantly between age groups, although older patients had more cardiovascular complications. These findings suggest that age alone should not exclude older patients from liver transplant.

CI = confidence interval; LT = liver transplant; MELD = model for end-stage liver disease; RR = relative risk

Improved patient and allograft survival after liver transplant (LT) reflects advances in surgical techniques, anesthesia, critical care, and infection control, as well as the development of targeted, potent immunosuppressants.1 This success has expanded the pool of transplant recipients to include persons previously considered ineligible because of advanced age and comorbid conditions. In addition, the relative percentage of people in older age groups is increasing more rapidly than that of the other groups in the population; by the year 2030, the percentage of the population aged 75 years and older is estimated to increase from 6% to 9% and will continue to increase to 12% by 2050. More people will reach older age in better health than in previous generations.2 Consequently, more elderly patients with liver failure might be considered candidates for LT. These developments will compound the relative shortage of donated organs and raise concern about the benefits of LT for older recipients. As decisions about organ allocation are made, they should be informed by outcomes data after LT.

Outcomes of LT in elderly patients vary.3-15 Most single-center case series for LT in recipients older than 60 years have reported overall success.3-8 Three centers reported no difference in morbidity or mortality among LT recipients older than 70 years.9-11 However, some studies have identified prolonged hospital stays and increased mortality after transplant in patients older than 60 years.12-16 One study that showed no difference in short-term outcome found lower 5-year survival rates in patients older than 60 years.17

Thus, the debate about the proper use of organs for LT based on age is ongoing.18-22 To address this issue in our transplant center, we compared graft loss and mortality after LT in patients aged 70 years or older with those in patients younger than 60 years. We also compared other postoperative complications, length of overall hospital stay, length of intensive care unit stay, and readmissions in these 2 groups of patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

In this matched-observational study, which was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, we retrospectively identified deceased donor LT recipients at our academic medical center between February 1, 1998, and May 31, 2004. Of 904 recipients identified, 42 underwent a first transplant at age 70 years or older. These LT recipients were matched 1:1 with LT recipients younger than 60 years by the cause of their end-stage liver disease, their calculated model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score (0-10, 11-20, 21-30, >30), and their sex. For each recipient aged 70 years or older, 1 recipient younger than 60 years was randomly selected from the group of all recipients younger than 60 years who satisfied the matching criteria for the given recipient older than 70 years. The final sample consists of 84 LT recipients who underwent transplant between March 19, 1998, and May 7, 2004. Older recipients underwent transplants a median of 1.5 years later (range, 3.3 years before to 4.1 years later) than their corresponding matched younger recipients; 24 (57%) of the matched pairs underwent transplants within 2 years of each other, and 32 (76%) underwent transplants within 3 years of each other. We excluded patients aged 60 to 69 years in an attempt to ensure that we were comparing 2 groups of distinct ages but that were similar otherwise. Preoperative and postoperative data on patients were abstracted from their medical records for comparison.

Regardless of the age of patients, standard criteria are maintained for all patients who undergo LT at our transplant center. To become transplant candidates, patients must have a diminished quality of life or a shortened life expectancy due to life-threatening complications or chronic, progressive liver disease for which no effective medical or surgical therapies are available other than LT. For proper selection and therapy, all potential transplant candidates undergo detailed physical, laboratory, social, and psychological evaluations. Tests are performed to confirm the diagnosis of end-stage liver disease, to rule out other potential treatment methods, to ensure adequate social support mechanisms, and to assess the candidate's ability to tolerate surgery. In our transplant center, all transplant candidates must meet the United Network for Organ Sharing medical indication for transplant; they must have a good social support system; they must have documented abstinence from alcohol, chemically dependent drugs, and tobacco; and they must have adequate financial resources, health care insurance with immunosuppressant coverage, or funds available to cover these expenses on an ongoing basis. Contraindications to LT include uncontrolled infection; advanced heart and lung disease in patients who are not candidates for multiorgan transplant; acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; severe neurologic dysfunction not correctable by LT; active alcohol and drug abuse; medical comorbid conditions deemed clinically important enough to diminish the likelihood of long-term posttransplant survival; and inability to comply with the complex medical regimen needed for posttransplant care (including psychiatric disease).

Our methods for evaluating cardiovascular comorbidity did not change during the study period. All transplant candidates underwent standard cardiovascular evaluation, including electrocardiograms and echocardiograms. Patients older than 50 years underwent stress testing with either dobutamine stress echocardiography or an adeno sine study; these patients also underwent colonoscopy. Any patient who had a positive test result for ischemic heart disease or pulmonary hypertension or who had a history of clinically important coronary artery disease underwent a cardiology or pulmonary consultation or both, with consideration for left or right heart catheterization or both.

Preoperative data were collected on the need for dialysis, lactulose, and diuretics and on the presence of encephalopathy, ascites, and other comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular accident, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. Donor age and patient laboratory values were recorded, including maximum international normalized ratio and creatinine, bilirubin, and minimum serum albumin levels.

Intraoperative data included donor characteristics, operative time, warm ischemic time, cold ischemic time, and fluid and blood product requirements.

Postoperative data were collected during follow-up of patients through May 2008 or until death to evaluate the following: (1) medical complications, (2) surgical complications, (3) rejection, (4) laboratory values, (5) hospital readmissions, (6) need for mechanical ventilation, and (7) graft loss and patient survival. Medical complications included neurologic complications (seizures, cerebrovascular accident, and encephalopathy), cardiac complications (cardiogenic shock, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmia requiring treatment), infectious complications (deep wound, catheter-related, peritonitis, cholangitis, and pneumonia), endocrine complications (diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia), renal failure, and cancer. Surgical complications included the need for immediate repeated surgery (bleeding and primary graft failure), bile leak or bile stricture, and vascular complications. Rejection was determined by biopsy. Laboratory values included maximum international normalized ratio, and levels of creatinine, bilirubin, and minimum serum albumin. Other complications included the number of hospital readmissions, the need for mechanical ventilation, graft loss, and patient survival.

Statistical Analyses

Preoperative baseline patient characteristics, intraoperative measures, and postoperative measures were compared between older patients (≥70 years) and younger patients (<60 years) with the McNemar test or the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative rates of mortality and graft loss after transplant. Associations of mortality and graft loss with patient age by group were investigated using single-variable Cox proportional hazards models stratified by matched pair. Although a rigorous multivariate analysis adjusting simultaneously for multiple possible confounding variables was not performed because of the relatively small number of patients who died or had graft loss, in an exploratory analysis we adjusted the Cox proportional hazards models individually for patients' baseline characteristics and comorbid conditions. Relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. Statistical significance was determined at the 5% level. Statistical analyses were performed using S-PLUS (version 8.0.1; Insightful Corp, Seattle, WA).

RESULTS

Preoperative Baseline Characteristics

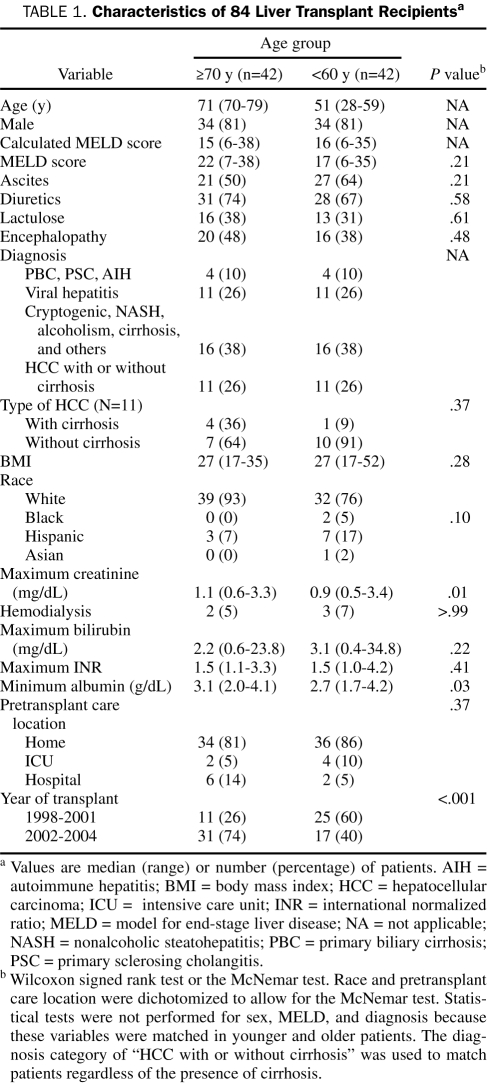

The demographic information and characteristics of patients by age group are summarized in Table 1. Characteristics of patients did not differ significantly between groups except for the maximum creatinine level, which was higher in older patients (P=.01), minimum serum albumin level, which was lower in younger patients (P=.03), and year of transplant, which was earlier in younger patients (P<.001).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 84 Liver Transplant Recipientsa

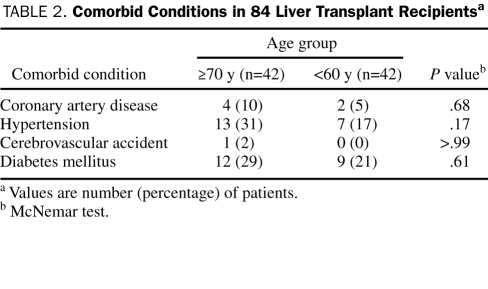

Baseline comorbid conditions were similar between the 2 groups (Table 2). The rate of hypertension was slightly higher in older patients but was not statistically significant.

TABLE 2.

Comorbid Conditions in 84 Liver Transplant Recipientsa

Intraoperative Variables

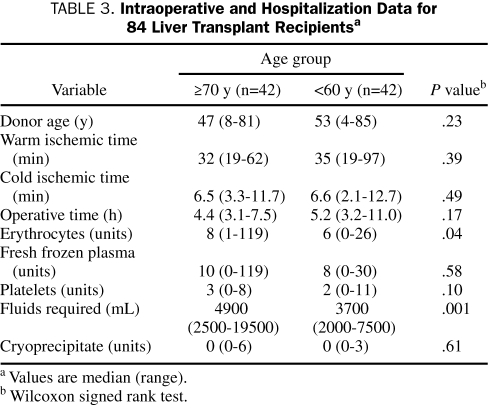

Intraoperative data are summarized in Table 3. Older patients required more erythrocyte transfusions (P=.04) and more intraoperative fluids (P=.001) than did younger patients. Additionally, older patients had a shorter operative time and younger donor age, although these variables were not significantly different than those of younger patients.

TABLE 3.

Intraoperative and Hospitalization Data for 84 Liver Transplant Recipientsa

Postoperative Variables and Outcome

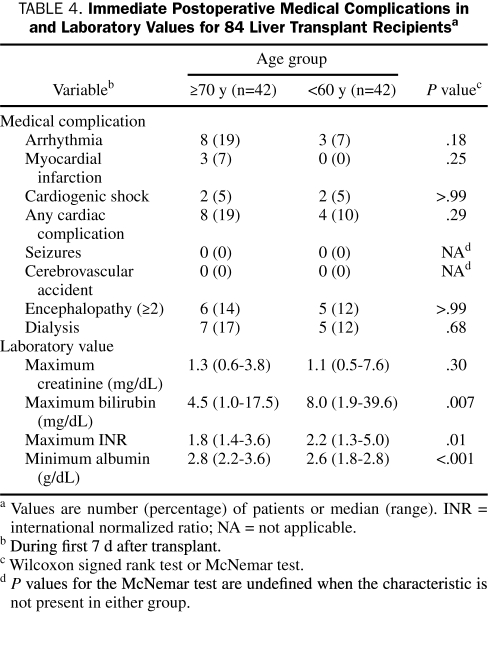

In the immediate postoperative period (ie, the first 7 days), cardiac arrhythmia and myocardial infarction occurred more frequently in older patients, but these differences were not statistically significant (Table 4). No statistically significant differences between younger and older patients were observed for other immediate medical complications. The maximum bilirubin level (P=.007) and the maximum international normalized ratio (P=.01) were lower in older patients, whereas the minimum albumin level was higher in these patients (P<.001) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Immediate Postoperative Medical Complications in and Laboratory Values for 84 Liver Transplant Recipientsa

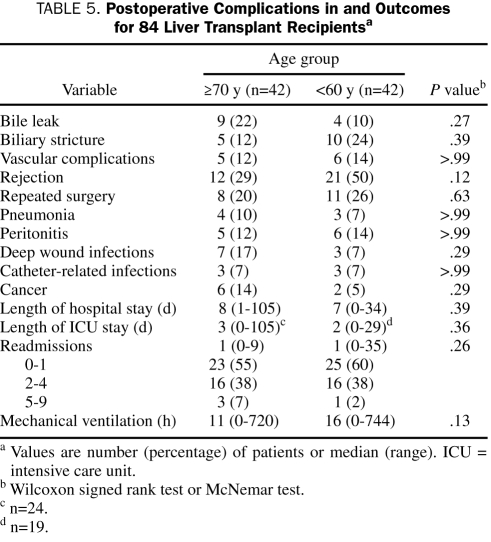

Postoperative complications that occurred more than 7 days after transplant are listed in Table 5. Although the differences were not statistically significant, older patients experienced less rejection and more frequent bile leaks, deep wound infections, and cancer. The occurrence of other complications was similar between groups. The length of hospital stay, length of intensive care unit stay, and number of readmissions were not significantly different between younger and older patients. After surgery, a total of 41 (18 [44%] older patients and 23 [56%] younger patients) did not require a stay in the intensive care unit and were instead transferred from the postanesthesia care area to the liver transplant ward.

TABLE 5.

Postoperative Complications in and Outcomes for 84 Liver Transplant Recipientsa

Mortality and Graft Loss

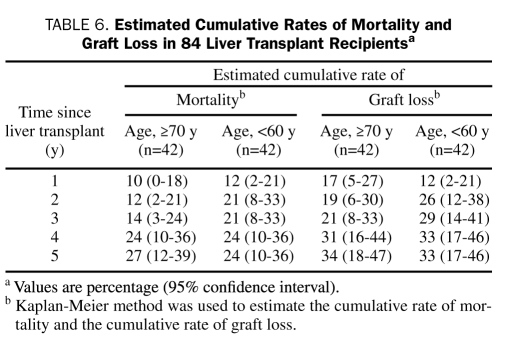

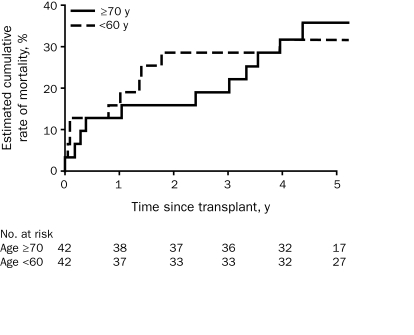

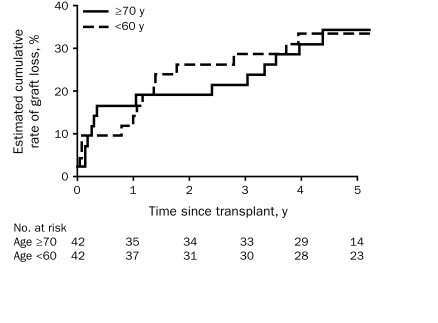

The median duration of follow-up for transplant recipients was 5.1 years (range, 0.1-8.5 years). Patients were followed up for at least 4 years. Of all 84 patients, 26 (31%) died (12 older patients and 14 younger patients). A total of 30 patients (36%) experienced graft loss (14 older patients and 16 younger patients). The estimated cumulative rates of death and graft loss at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years after transplant according to patient age group are listed in Table 6. These rates were similar for older and younger patients. Single-variable Cox proportional hazards analysis showed that the estimated risks of death (RR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.43-2.31; P>.99) and graft loss (RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.54-2.52; P=.70) were not significantly increased in older patients compared with those in younger patients. These findings were relatively consistent when adjusting Cox models individually for patient characteristics and comorbid conditions in an exploratory analysis, with estimated RRs ranging from 0.84 to 1.32 for death and from 0.88 to 1.46 for graft loss. The estimated cumulative mortality and graft loss within 5 years of liver transplant by age group are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

TABLE 6.

Estimated Cumulative Rates of Mortality and Graft Loss in 84 Liver Transplant Recipientsa

FIGURE 1.

Estimated cumulative rate of mortality after liver transplant, by patient age at time of transplant.

FIGURE 2.

Estimated cumulative rate of graft loss after liver transplant, by patient age at time of transplant.

DISCUSSION

The demand for liver transplant among elderly patients with liver disease is increasing. Data on comorbid conditions and clinical outcomes are essential to the development of good organ allocation policies. Two major concerns emerge with this group of patients: (1) whether they can undergo successful transplant without serious complications due to age and comorbid conditions and (2) whether they have survival rates equivalent to those of younger recipients.

The main finding of the current single-center study of LT recipients with a median follow-up of 5.1 years was that the risk of death or graft loss in patients aged 70 years or older was not noticeably increased compared with that in patients younger than 60 years, which suggests that older age (≥70 years) does not preclude LT. A potential concern in the elderly population is the risk of posttransplant cardiovascular complications, which were observed in 19% of our transplant recipients aged 70 years or older compared with 10% in those younger than 60 years. Although this difference was not statistically significant, it does suggest that studies with more patients and longer follow-up are needed to better define this risk.

The careful selection of LT candidates is a likely explanation for the good outcomes in elderly recipients reported herein and by others.3-9 However, younger patients were matched to older patients by calculated MELD score and cause of disease so that they would have similar risk profiles.22 The categories for which calculated MELD scores were matched (0-10, 11-20, 21-30, >30) may appear to be broad. However, although unplanned, this matching was actually consistent with ±3 matching for 29 (69%) of the matched pairs and consistent with ±5 matching for 36 (86%). In general, the median calculated MELD score was low for the entire group, with a value of 16. This was partially explained (data not shown) because there were 22 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who had a median calculated MELD score of 12 (range, 6-24), although the median calculated MELD score for the remaining 62 patients was still a relatively low 16 (range, 7-38).

Older patients had slightly higher preoperative albumin levels, which might indicate better nutritional status. Differences in donor-specific factors were not considered in this analysis.

Our data showed that older patients required more fluids intraoperatively, possibly because of decreased vascular tone and pronounced autonomic insufficiency to anesthetic agents. Nevertheless, this difference did not translate into increased morbidity or increased need for prolonged mechanical ventilation.

Older patients also had a lower incidence of rejection and a higher incidence of infection and cancer, which suggests a weaker immune system with advancing age. Similar findings have been reported in other studies.3,8,10 For example, Cross et al8 found that malignancy was the most frequent cause of death in patients older than 65 years. We suspect that the use of less intensive immunosuppression in older patients might result in fewer complications without compromising graft survival.

Older recipients have undergone more transplants in recent years than younger recipients, which raises the question of whether the observed acceptable outcomes of older recipients are the result of improved care over time. Specifically, 74% of older recipients underwent transplant after 2001 compared with 40% of younger recipients. However, despite this observed difference, in 33 (79%) of the 42 matched pairs the date of the transplant for older recipients was no more than 3 years after that for younger recipients and it was earlier in older recipients in 11 pairs (26%). Thus, although we acknowledge that younger recipients have an earlier date of transplant, we do not think that this difference between matched pairs is strong enough to translate into substantially improved care of older recipients, and it has little impact on the validity of our results.

The current study is limited by its retrospective nature, its focus on a single transplant center's experience, and the small number of older patients enrolled. Although we observed no noticeable increase in the risk of graft loss or death in these 42 older recipients, as evidenced by estimated RRs close to a value of 1, the comparatively small sample size resulted in a lack of precision in these estimates. Thus, on the basis of the upper boundaries of the 95% CIs for the RRs presented earlier, we cannot completely exclude the possibility of increased risk of graft loss or death in older recipients.

CONCLUSION

With a median follow-up of 5.1 years, mortality and graft loss in transplant recipients aged 70 years or older were similar to those in recipients younger than 60 years. No postoperative complications occurred significantly more often in older patients. These data favor the position that well-selected patients older than 70 years should not be excluded from consideration for LT on the basis of age alone.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to the memory of Carmen Barrero de Mattos.

REFERENCES

- 1.United Network for Organ Sharing www.unos.org/ UNOS Web site. Accessed August 27, 2009.

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau 2008 national population projections. www.census.gov/population/www/projections/2008projections.html. www.census.gov/population/www/projections/2008projections.html Accessed August 27, 2009.

- 3.Stieber AC, Gordon RD, Todo S, et al. Liver transplantation in patients over sixty years of age. Transplantation 1991;51(1):271-273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pirsch JD, Kalayoglu M, D'Alessandro AM, et al. Orthotopic liver transplantation in patients 60 years of age and older. Transplantation 1991;51(2):431-433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emre S, Mor E, Schwartz ME, et al. Liver transplantation in patients beyond age 60. Transplant Proc. 1993;25(1, pt 2):1075-1076 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheiner P, Emre S, Guy SR, Min A, Schwartz ME, Miller CM. The older liver transplant candidate: what are the limits? Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2(5) (suppl 1):9-11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filipponi F, Roncella M, Boggi U, et al. Liver transplantation in recipients over 60. Transplant Proc. 2001;33(1-2):1465-1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cross TJ, Antoniades CG, Muiesan P, et al. Liver transplantation in patients over 60 and 65 years: an evaluation of long-term outcomes and survival. Liver Transpl. 2007;13(10):1382-1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudich S, Busuttil R. Similar outcomes, morbidity, and mortality for orthotopic liver transplantation between the very elderly and the young. Transplant Proc. 1999;31(1-2):523-525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safdar K, Neff GW, Montalbano M, et al. Liver transplant for the septuagenarians: importance of patient selection. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(5):1445-1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipshutz GS, Hiatt J, Ghobrial RM, et al. Outcome of liver transplantation in septuagenarians: a single-center experience. Arch Surg. 2007;142(8):775-781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zetterman RK, Belle SH, Hoofnagle JH, et al. Age and liver transplantation: a report of the Liver Transplantation Database. Transplantation 1998;66(4):500-506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adam R, Cailliez V, Majno P, et al. Normalised intrinsic mortality risk in liver transplantation: European Liver Transplant Registry study [published correction appears in Lancet. 2001;367(9264):1296] Lancet 2000;356(9230):621-627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy MF, Somasundar PS, Jennings LW, et al. The elderly liver transplant recipient: a call for caution. Ann Surg. 2001;233(1):107-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia CE, Garcia RF, Mayer AD, Neuberger J. Liver transplantation in patients over sixty years of age. Transplantation 2001;72(4):679-684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrero JI, Lucena JF, Quiroga J, et al. Liver transplant recipients older than 60 years have lower survival and higher incidence of malignancy. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(11):1407-1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins BH, Pirsch JD, Becker YT, et al. Long-term results of liver transplantation in older patients 60 years of age and older. Transplantation 2000;70(5):780-783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuberger J, James O. Guidelines for selection of patients for liver transplantation in the era of donor-organ shortage. Lancet 1999;354(9190):1636-1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keswani RN, Ahmed A, Keeffe EB. Older age and liver transplantation: a review. Liver Transpl. 2004;10(8):957-967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galandiuk S, Sterioff S. The problems of organ donor shortage [editorial]. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(3):320-321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman RB, Jr, Wiesner RH, Harper A, et al. UNOS/OPTN Liver Disease Severity Score. UNOS/OPTN Liver and Intestine. UNOS/OPTN Pediatric Transplantation Committees The new liver allocation system: moving toward evidence-based transplantation policy. Liver Transpl. 2002;8(9):851-858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlitt HJ, Obed A. Should liver transplantation be excluded in elderly patients? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008May;5(5):242-243 Epub 2008 Mar 11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]