Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To examine clinical characteristics, laboratory features, and outcomes of patients with lupus-like syndrome attributable to anti—tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) therapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: We performed a retrospective review of patients with lupus-like syndrome attributable to anti—TNF-α therapy at Mayo Clinic's site in Rochester, MN, between July 1, 2000, and June 30, 2008.

RESULTS: Of 14 patients (mean age at disease onset, 46.2 years), 12 (86%) were female. Ten patients (71%) had Crohn disease, and 4 (29%) had rheumatoid arthritis. Thirteen patients (93%) originally were treated with infliximab, and 1 (7%) was treated with adalimumab. A lupus-ike syndrome occurred after a mean treatment duration of 16.2 months. Features of lupus included presence of antinuclear antibodies (14 patients [100%]), arthritis (13 patients [93%]), anti—double-stranded-DNA antibodies (10 patients [71%]), cutaneous findings (malar rash, discoid rash, or photosensitivity, 4 patients [29%]), serositis (4 patients [29%]), hematologic abnormalities (4 patients [29%]), oral ulcers (4 patients [29%]), and lupus anticoagulant (1 patient [7%]). No patient had renal or neurologic abnormalities. All patients improved after stopping anti—TNF-α therapy (mean time to improvement, 2.9 months). Four (80%) of 5 patients tolerated an alternative TNF-α inhibitor (adalimumab, 3 patients; etanercept, 1 patient) without recurrence of lupus-like syndrome.

CONCLUSION: Compared with previous studies, cutaneous findings were less frequent and arthritis was more frequent in our cohort of patients. Some patients were able to tolerate an alternative TNF-α inhibitor without recurrence of lupus-like syndrome.

The authors compared clinical characteristics, laboratory features, and outcomes of patients with lupus-like syndrome attributable to anti—tumor necrosis factor α therapy and noted that, compared with previous studies, cutaneous findings were less frequent and arthritis was more frequent in their patients. Some patients were able to tolerate an alternative anti—tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor without recurrent lupus-like syndrome.

ACR = American Congress of Rheumatology; ANA = antinuclear antibodies; DILE = drug-induced lupus erythematosus; dsDNA = double-stranded DNA; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor α

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors are commonly used to treat inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn disease. Despite the frequent induction of autoantibody production in patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors,1-12 development of lupus-like syndrome is uncommon, with a prevalence of 0.5% to 1% in treated patients.1 Affected patients often have cutaneous findings (major organ involvement is rare), and improvement almost always occurs after discontinuation of anti—TNF-α therapy.1,13 We retrospectively examined the clinical characteristics, laboratory features, and outcomes of patients with lupus-like syndrome attributable to anti—TNF-α therapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Patients were treated at Mayo Clinic's site in Rochester, MN, from July 1, 2000, through June 30, 2008. Those who denied research authorization were excluded from the study.

We used the institutional medical index and text retrieval system to identify patients who were diagnosed as having systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) induced by anti—TNF-α therapy. We searched coded medical index data for patients with a diagnosis of SLE (or a diagnosis that contained the term lupus) who also had anti—TNF-α therapy described in the medical record (either within medication data or diagnosis information). We then searched the text retrieval system to identify patients who had a clinical note containing both lupus and anti—TNF-α therapy (specific agents or generalized terminology).

We examined medical records to abstract the following information: patient characteristics; disease requiring anti—TNF-α therapy; type of anti—TNF-α agent used; clinical and immunologic features suggestive of SLE; laboratory test results before, during, and after anti—TNF-α therapy; systemic therapies (eg, immunosuppressive agents); and outcome after discontinuation of medication that induced lupus-like syndrome (with or without new anti—TNF-α therapy).

Definition of Lupus-Like Syndrome Attributable to Anti—TNF-α Treatment

Because specific criteria for the diagnosis of drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE) have not been established,14-17 we considered the diagnosis in cases that showed all the following: (1) a temporal relationship between clinical manifestations and anti—TNF-α therapy; (2) at least 1 serologic American Congress of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria of SLE18 (eg, antinuclear antibodies [ANAs], anti—double-stranded-DNA [anti-dsDNA] anti bodies); and (3) at least 1 nonserologic ACR criteria (eg, arthritis, serositis, hematologic disorder, malar rash). Per the convention of De Bandt et al,15

musculoskeletal symptoms were taken into account only if they reappeared with other lupus symptoms in a patient in whom they had previously disappeared while receiving anti-TNF therapy, and isolated positive results for ANAs or anti-dsDNA antibodies were not considered for diagnosis, given their high frequency in patients receiving this therapy.

Patients who did not meet the aforementioned criteria were excluded from analysis.

Autoantibody Detection Assays

Antinuclear antibodies were detected with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (positive values defined as ≥1.0 U). Anti-dsDNA antibodies were detected with a multiplex flow immunoassay (positive values defined as ≥25 IU before 2008, ≥10 IU since 2008).

RESULTS

The combined searches of the institutional medical index and text retrieval system yielded 121 patients, of whom only 14 were shown to have a diagnosis of SLE induced by anti—TNF-α therapy after detailed chart review and exclusion of patients who did not meet our study's definitional criteria for diagnosis. Characteristics of these 14 patients are shown in Table 1. Mean duration of disease before initiation of anti—TNF-α therapy was 13.5 years (range, 1-35 years). Patients were treated with systemic anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive agents (mean, 3.9 agents; range, 1-7 agents) before starting treatment with the anti—TNF-α agent that led to lupus-like syndrome. Two patients (both had rheumatoid arthritis) were positive for ANA and anti-dsDNA antibodies before starting anti—TNF-α therapy, but they had no clinical characteristics or other ACR criteria of SLE that would suggest a connective tissue disease with overlapping features (subsequent follow-up of these patients showed no recurrence of SLE after cessation of anti—TNF-α therapy). No patient had received other medications known to cause lupus.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Clinical Manifestations and Laboratory Featuresa

Anti—TNF-α Therapy and Features of Lupus-Like Syndrome

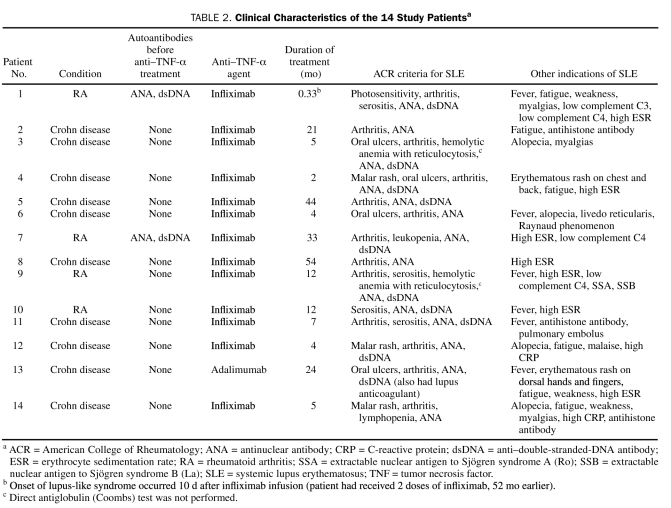

Features of lupus-like syndrome (including ACR criteria) are detailed in Tables 1 and 2. Arthritis was the first sign to develop in 10 patients (71%); other presenting signs included serositis (2 patients [14%]), leukopenia (1 patient [7%]), and cutaneous findings (1 patient [7%]). The most debilitating sign was arthritis (13 patients [93%]); patients had new onset or abrupt worsening of arthritis while the underlying disease process (Crohn disease or rheumatoid arthritis) was quiescent or well controlled. Given the predominance of noncutaneous findings, skin biopsy was performed for only 1 patient (7%). Biopsy findings were nondiagnostic after routine microscopy and direct immunofluorescence microscopy.

TABLE 2.

Clinical Characteristics of the 14 Study Patientsa

Treatment of Lupus-Like Syndrome

Mean duration of lupus-like syndrome (from time of onset to diagnosis) was 3.2 months (range, 1 day to 8 months), and anti—TNF-α treatment was discontinued at the time of diagnosis. Thirteen patients (93%) had been concomitantly treated with 1 or more systemic agents during anti—TNF-α treatment (prednisone, 8 patients [57%]; methotrexate, 7 patients [50%]; azathioprine, 4 patients [29%]); these systemic agents were continued for the underlying disease (Crohn disease, rheumatoid arthritis) when lupus-like syndrome was diagnosed. Two patients (14%) required hospitalization (mean duration, 4 days), and 1 patient (7%) received methotrexate (12.5 mg, administered subcutaneously, once per week) for 3 months for treatment of the lupus-like syndrome. Ten patients (71%) had either brief treatment with corticosteroids (maximum daily prednisone dose, 60 mg, tapered to 0 mg) or transient increase in the baseline prednisone dose that was tapered back to baseline levels during the subsequent weeks to months (maximum taper period, 5.5 months). Follow-up data were available for 13 patients (93%); after diagnosis, all had improvement of lupus manifestations within several months after stopping treatment with the anti—TNF-α agent (mean, 2.9 months; range, 1-6 months).

Immunologic Profile After Discontinuation of Anti—TNF-α Therapy

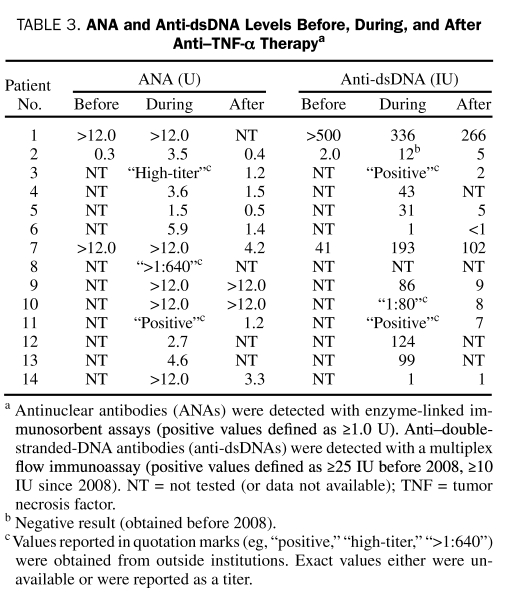

Levels of ANA were reassessed for 10 patients (71%); for 2 patients (20%), ANA returned to normal values 4 and 21 months after lupus-like syndrome was diagnosed. Five patients (50%) had a marked decrease in ANA (1.5-12 months after the initial positive findings), and 1 patient (10%) had a slightly decreased ANA (this patient had evidence of ANA before treatment with the anti—TNF-α agent). Values of ANA remained the same for 2 patients (20%) (3 and 16.5 months after stopping anti—TNF-α therapy; of note, anti-dsDNA antibodies returned to normal values in both patients within 4.5 months). Anti-dsDNA antibodies were reassessed in 7 (70%) of the 10 patients with positive values; of these, 5 patients (71%) had normal values (4-21 months after the initial positive results). Two patients (29%) (both were positive for anti-dsDNA antibodies before treatment with the anti—TNF-α agent) had decreased but still higher than normal levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies. Antihistone antibody levels were reassessed in 2 (67%) of 3 patients; for 1 patient, the level was normal 2 months later, and the other patient had a decreased level 3 months later. The ANA and anti-dsDNA antibody levels for individual patients before, during, and after anti—TNF-α therapy are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

ANA and Anti-dsDNA Levels Before, During, and After Anti—TNF-α Therapya

Follow-up

The mean follow-up after diagnosis was 35.5 months (range, 3-100 months); 8 patients (57%) had at least 24 months of follow-up. No patient had recurrent disease after anti—TNF-α treatment was discontinued. One patient died of pancreatic cancer 4 years after the diagnosis of lupus-like syndrome.

Use of Additional Anti—TNF-α Agents After Lupus-Like Syndrome

Five patients (36%) received treatment with a different anti—TNF-α agent after lupus-like syndrome was diagnosed; 4 of the 5 patients had no adverse effects with the second treatment. At the last follow-up, patients No. 3 and No. 8 (patient-specific data are in Table 2) had tolerated adalimumab for 6 months (38 months after infliximab was stopped) and 42 months (2 months after infliximab was stopped), respectively. Patient No. 9 was treated with etanercept for 41 months (19 months after infliximab was stopped). Patient No. 1 tolerated an 8-month course of treatment with adalimumab (2.5 months after infliximab was stopped); this patient also did well with 2 years of etanercept therapy and 8 months of adalimumab that was administered 1 to 2 years before treatment with infliximab that led to lupus-like syndrome.

Although patient No. 2 tolerated 2 months of etanercept immediately after discontinuation of infliximab, symptoms and signs of lupus-like syndrome reemerged when the patient restarted infliximab therapy 4 months later for a 9-month duration (arthritis recurred despite pretreatment with intravenous corticosteroids before each infliximab infusion). Similarly, adalimumab (initiated 30 months after the initial episode of infliximab-induced lupus-like syndrome) caused fever, malaise, elevated ANA levels, and elevated extractable nuclear antigen antibodies after 18 months of treatment. Of note, patient No. 13 was treated with infliximab on 2 occasions before adalimumab-induced lupus-like syndrome developed (3 infusions, 5 years before adalimumab therapy, did not result in adverse effects; 1 infusion, 2 years before initiation of adalimumab, caused a hypersensitivity reaction with generalized edema and transient vision loss).

DISCUSSION

In the current study of 14 patients who had lupus-like syndrome attributable to treatment with anti—TNF-α agents, characteristics (eg, sex and age at onset) were similar to those reported previously.13 Lupus-like syndrome induced by anti—TNF-α therapy is rare: only 92 cases have been reported through 2006.13 The prevalence in patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors is estimated to be between 0.5% and 1%,1 although a French study described a lower rate of 0.19% with infliximab.15 Other studies have reported prevalence rates from 0.1% to 0.6% for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and up to 1.6% for patients with Crohn disease.3 A study that reviewed 500 patients with Crohn disease who were treated with infliximab showed that only 3 patients had DILE.19 The design of the current study precluded an estimate of the prevalence of lupus-like syndrome induced by anti—TNF-α therapy for several reasons. Given the tertiary nature of Mayo Clinic, some referral bias was likely present. Additionally, it was not possible to determine how many patients were exposed to anti—TNF-α therapy during the study period because many patients did not fill their prescriptions at the Mayo Clinic pharmacy, and follow-up data were not always available.

Furthermore, this was not a population-based study. Most patients from previous reports had rheumatoid arthritis, whereas 10 of our 14 patients had Crohn disease. We are unaware of appreciable differences in the patient population or the use of anti—TNF-α therapy at Mayo Clinic compared with that of the institutions described in previous re ports; although we cannot completely explain this discrepancy, bias introduced during the case ascertainment process may be partly responsible. Infliximab (40 patients [44%]) and etanercept (37 patients [40%]) were the causative agents for most of the previously reported patients; in contrast, 13 of our 14 patients were treated with infliximab. Nevertheless, we similarly observed high rates of positivity for ANA (14 patients) and anti-dsDNA antibodies (10 patients).

Cutaneous involvement was relatively infrequent in our cohort of 14 patients when compared with previous reports. Only 4 patients had cutaneous features consistent with ACR criteria (malar rash, discoid rash, or photosensitivity) compared with 62 (67%) of the 92 cases reported previously.13 Two additional patients in our series had cutaneous findings that were nonspecific for SLE (livedo reticularis and erythema of the dorsal hands and fingers); in total, only 6 of our 14 patients had cutaneous involvement. Data from a French survey15 showed frequent cutaneous involvement for patients with lupus-like syndrome induced by anti—TNF-α therapy; of 22 patients (12 [55%] with ≥4 ACR criteria and 10 [45%] with 3 ACR criteria), 16 (73%) met at least 1 ACR cutaneous criteria for SLE. Previous authors have compared DILE to idiopathic SLE and reported that malar rash, discoid rash, and photosensitivity are rare in DILE.14,16 From a cutaneous standpoint, patients in the current study had findings that were more consistent with traditional findings of DILE, rather than the more recently described cutaneous findings that occurred in approximately two-thirds of patients with lupus-like syndrome attributable to anti—TNF-α agents.13

Arthritis, present in 13 of our patients, was the most common and most debilitating feature; patients had tenderness, swelling, or effusion, rather than arthralgias without evidence of arthritis. In their review of 92 previously reported cases, Ramos-Casals et al13 found that arthritis was much less frequent (22/72 patients [31%] with detailed clinical data available). De Bandt et al15 noted arthritis in 6 (50%) of the 12 patients in their study who had at least 4 of the ACR criteria for SLE. Previous authors have commented on factors that confound the diagnosis of lupus-like syndrome attributable to therapy with TNF inhibitors: (1) patients often have baseline arthritis (caused by rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn disease); (2) patients often receive concomitant methotrexate therapy, which can cause hematologic abnormalities; and (3) patients with rheumatoid arthritis may have a preexisting syndrome with symptoms that overlap with those of SLE.2,3 Arthritis was considered relevant in our series only if it was new onset or was an abrupt worsening in the context of other lupus criteria; furthermore, we considered arthritis only if it occurred when the underlying disease process was quiescent or well-controlled with anti—TNF-α therapy. Twelve of our patients also were seen by rheumatologists, who judged their features to be compatible with lupus-like syndrome attributable to anti—TNF-α treatment.

Overall, patients in the current study had mild disease that improved after anti—TNF-α therapy was discontinued. Mild hematologic abnormalities were present in 4 patients, and 3 patients had received methotrexate concurrently with the anti—TNF-α treatment; hematologic parameters also improved after cessation of anti—TNF-α therapy. No patient had serious internal organ involvement such as renal or neurologic abnormalities; likewise, such serious events were infrequent in previously reported cases.13

The high frequency of autoantibody induction, including ANA and anti-dsDNA antibodies, in patients treated with anti—TNF-α agents is well documented.1-12 Infliximab can lead to induction of ANA in 63.8% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and 49.1% of patients with Crohn disease; it further can induce production of anti-dsDNA antibodies in 13% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and 21.5% of patients with Crohn disease.5 When considering all anti—TNF-α agents, the prevalence of ANA induction ranges from 23% to 57%, and the prevalence of anti-dsDNA antibody induction is from 9% to 33%.3 Despite frequent induction of autoantibodies, development of lupus-like syndrome with anti—TNF-α agents is rare.

Some patients with lupus-like symptoms after treatment with TNF-α inhibitors do not fulfill the ACR criteria for SLE,2 as highlighted by our study that showed 9 of 14 patients fulfilled at least 4 SLE criteria compared with 37 (51%) of 72 previously reported cases with detailed available clinical data.13 As previously mentioned, 2 patients in the current study had ANA and anti-dsDNA antibodies before beginning anti—TNF-α therapy. Of the 22 patients reported by De Bandt et al,15 4 (18%) had ANA before starting anti—TNF-α therapy, and 1 (5%) of the 4 also was positive for anti-dsDNA antibodies. In their analysis of 92 previously reported cases, Ramos-Casals et al13 showed that if patients with preexisting SLE criteria were excluded, only 35% of patients (25/72 cases with detailed clinical data, rather than 51% [37/72 cases]) had at least 4 SLE criteria. Some authors contend that the ACR criteria were developed primarily for classification in clinical studies, rather than for establishment of the SLE diagnosis in a given patient.20 Patients with DILE may present with clinically important lupus-like syndromes without fulfilling at least 4 ACR criteria.21

An important question is whether patients with TNF-inhibitor—associated lupus-like syndrome can safely receive an alternative anti—TNF-α agent. Reports regarding this issue are scarce, but one author described 4 patients who were challenged with the same or different agents and had no recurrence of lupus symptoms (3 received etanercept [rechallenge] and 1 received adalimumab).4 In our study, 4 of 5 patients tolerated an alternative TNF inhibitor (adalimumab for 3 patients, etanercept for 1) without recurrence of lupus-like syndrome after discontinuation of infliximab. Nevertheless, these findings should be interpreted cautiously, given the small number of patients who were rechallenged.

The current study is limited because of its retrospective design. Ascertainment bias in the case selection process can occur in retrospective studies, resulting in a study cohort that does not represent the general population. Potential sources of ascertainment bias in our study may include health care access bias (ie, when patients seen at an institution do not adequately represent the cases seen in the general community) and referral bias attributable to the complexity of health problems for which patients often are referred to Mayo Clinic.22 Furthermore, like all previous retrospective studies on this subject, it is influenced by the confounding factors described earlier for correctly diagnosing lupus-like syndrome attributable to TNF inhibitor use (eg, baseline arthritis caused by the underlying condition being treated, concomitant methotrexate therapy, preexisting connective tissue disease with overlapping features). We excluded patients from analysis whose diagnoses were questionable because of these confounding factors.

CONCLUSION

Patients with lupus-like syndrome attributable to TNF inhibitor therapy generally presented with mild findings (no severe involvement of internal organs) that improved after discontinuation of therapy. Compared with previous studies, cutaneous findings occurred less frequently and arthritis more frequently in our cohort of patients. Tolerance of an alternative anti—TNF-α agent without recurrence of lupus-like syndrome, which was possible for several of our patients, deserves further exploration.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The results of this study were presented at the Annual Meeting of the North American Rheumatologic Dermatology Society (NARDS); October 17, 2009; which occurs during the Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology/Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals (ACR/ARHP); October 16-21, 2009; Philadelphia, PA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aringer M, Smolen JS. The role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(1):202 Epub 2008 Jan 23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Rycke L, Baeten D, Kruithof E, Van den Bosch F, Veys EM, De Keyser F. The effect of TNFalpha blockade on the antinuclear antibody profile in patients with chronic arthritis: biological and clinical implications. Lupus 2005;14(12):931-937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mongey AB, Hess EV. Drug insight: autoimmune effects of medications: what's new? Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4(3):136-144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cush JJ. Unusual toxicities with TNF inhibition: heart failure and drug-induced lupus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22(5)(suppl 35):S141-S147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atzeni F, Turiel M, Capsoni F, Doria A, Meroni P, Sarzi-Puttini P. Autoimmunity and anti-TNF-α agents. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1051:559-569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Bandt M. Lessons for lupus from tumour necrosis factor blockade. Lupus 2006;15(11):762-767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caramaschi P, Biasi D, Colombatti M, et al. Anti-TNFα therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Rheumatol Int. 2006January;26(3):209-214 Epub 2004 Dec 31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferraro-Peyret C, Coury F, Tebib JG, Bienvenu J, Fabien N. Infliximab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis-induced specific antinuclear and antiphospholipid autoantibodies without autoimmune clinical manifestations: a two-year prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(6):R535-R543 Epub 2004 Sep 23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poulalhon N, Begon E, Lebbé C, et al. A follow-up study in 28 patients treated with infliximab for severe recalcitrant psoriasis: evidence for efficacy and high incidence of biological autoimmunity. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(2):329-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callen JP. Complications and adverse reactions in the use of newer biologic agents. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26(1):6-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheinfeld N. A comprehensive review and evaluation of the side effects of the tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab. J Dermatolog Treat 2004;15(5):280-294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebwohl M, Bagel J, Gelfand JM, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: monitoring and vaccinations in patients treated with biologics for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008January;58(1):94-105 Epub 2007 Nov 5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Muñoz S, et al. Autoimmune diseases induced by TNF-targeted therapies: analysis of 233 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86(4):242-251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F, Capsoni F, Lubrano E, Doria A. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus [published retraction appears in Autoimmunity. 2008;41(3):241] Autoimmunity 2005;38(7):507-518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Bandt M, Sibilia J, Le Loët X, et al. Club Rhumatismes et Inflammation Systemic lupus erythematosus induced by anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy: a French national survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(3):R545-R551 Epub 2005 Mar 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasoo S. Drug-induced lupus: an update. Lupus 2006;15(11):757-761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benucci M, Li Gobbi F, Fossi F, Manfredi M, Del Rosso A. Drug-induced lupus after treatment with infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2005;11(1):47-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus [letter]. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Jr, Tremaine WJ, et al. The safety profile of infliximab in patients with Crohn's disease: the Mayo Clinic experience in 500 patients. Gastroenterology 2004;126(1):19-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costner MI, Sontheimer RD, Provost TT. Lupus erythematosus. In: Sontheimer RD, Provost TT, eds. Cutaneous Manifestations of Rheumatic Diseases Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:15-64 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page AV, Liles WC. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced lupus-like syndrome presenting as fever of unknown origin in a liver transplant recipient: case report and concise review of the literature. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(5):1768-1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delgado-Rodríguez M, Llorca J. Bias. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58(8):635-641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.