Abstract

Many proliferative, invasive, and immune tolerance mechanisms that support normal human pregnancy are also exploited by malignancies to establish a nutrient supply and evade or edit the host immune response. In addition to the shared capacity for invading through normal tissues, both cancer cells and cells of the developing placenta create a microenvironment supportive of both immunologic privilege and angiogenesis. Systemic alterations in immunity are also detectable, particularly with respect to a helper T cell type 2 polarization evident in advanced cancers and midtrimester pregnancy. This review summarizes the similarities between growth and immune privilege in cancer and pregnancy and identifies areas for further investigation. Our PubMed search strategy included combinations of terms such as immune tolerance, pregnancy, cancer, cytokines, angiogenesis, and invasion. We did not place any restrictions on publication dates. The knowledge gained from analyzing similarities and differences between the physiologic state of pregnancy and the pathologic state of cancer could lead to identification of new potential targets for cancer therapeutic agents.

CTL = CD8+ T cytotoxic lymphocyte; DC = dendritic cell; EVT = extravillous trophoblast; HLA = human leukocyte antigen; IL = interleukin; NK = natural killer; TH1 = helper T cell type 1; TH2 = helper T cell type 2; Treg = regulatory T cell; uNK = uterine NK

A substantial body of literature exists describing the mechanisms cancer cells use to escape apoptosis and migrate through normal structures while evading a host immune response. What is not well known, however, is how these complex and interrelated mechanisms are orchestrated, starting with modulation of the immune response within the tumor microenvironment and ending with migration and proliferation of cancer cells at distant sites. One potential model to further study how a single malignant cell could proliferate and then metastasize undetected within a host is that of normal human pregnancy, in which the developing placenta invades the uterus and a semiallogeneic fetus escapes rejection from the maternal immune system.1 A multitude of immunomodulatory properties of the fetomaternal interface (placenta) have evolved to allow the survival of the immunologically distinct fetus to parturition without an attack from the maternal immune system. The similarities between the mechanisms involved in fetomaternal and tumor-associated immunologic tolerance are intriguing and suggest a common pattern; however, neither system of immune evasion is perfect. A clear example of placental failure to protect the fetus against maternal immunity is that of Rh incompatibility. In multiparous women sensitized against fetal Rh antigens, re-exposure to fetal Rh antigens with subsequent pregnancy may lead to hemolytic disease of the newborn and fetal death.2 Such imperfections of shared mechanisms of immune tolerance between pregnancy and cancer suggest that cancer rejection via immunologic means may be possible, even considering the myriad mechanisms extending immunologic privilege to the fetus as well as cancer cells.

This review summarizes the parallels in proliferation, invasion, and immune privilege between cancer and pregnancy by first detailing shared characteristics of fetal-derived trophoblast cells of the placenta and tumor cells. It then describes the similarities between tolerogenic systems within the tumor microenvironment and the fetomaternal interface. Finally, it provides an overview of the evidence for systemic immune modulation in cancer and pregnancy and suggests the implications of these similarities in designing an integrated approach to cancer therapy. Our PubMed search strategy included combinations of terms such as immune tolerance, pregnancy, cancer, cytokines, angiogenesis, and invasion. We also searched for articles on cellular subsets, including natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells (DCs), regulatory T cells (Treg), and other lymphocyte populations with respect to their presence and function in pregnancy and cancer. We did not place any restrictions on publication dates. A better understanding of how the maternal immune system is altered during the normal processes of implantation, gestation, and labor may translate into individualized, novel therapies aimed at restoring immune competency in patients with advanced malignancies.

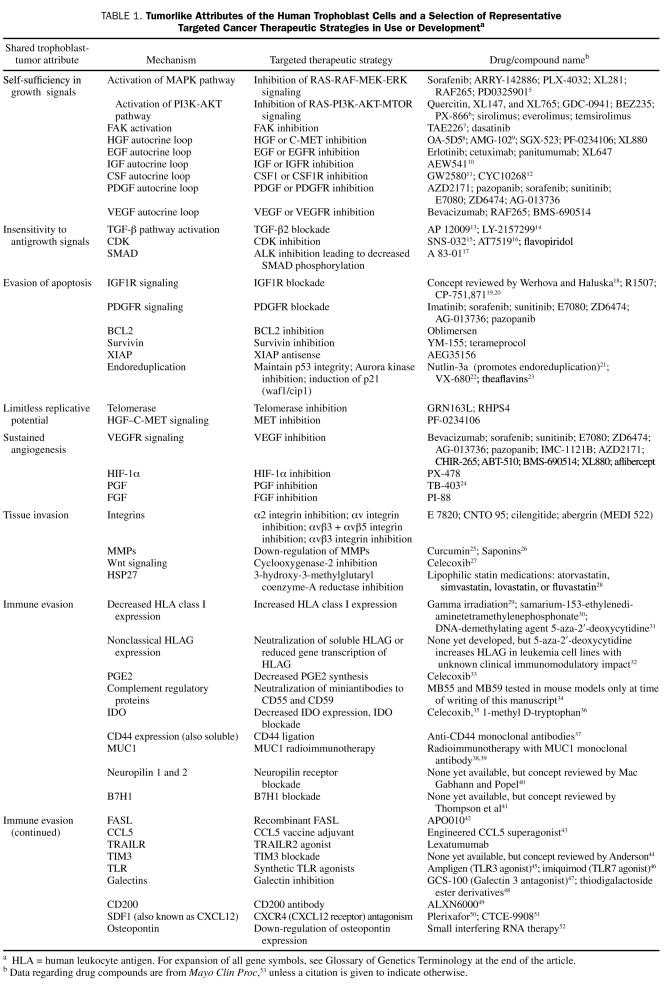

SHARED CHARACTERISTICS OF TROPHOBLAST CELLS AND TUMOR CELLS

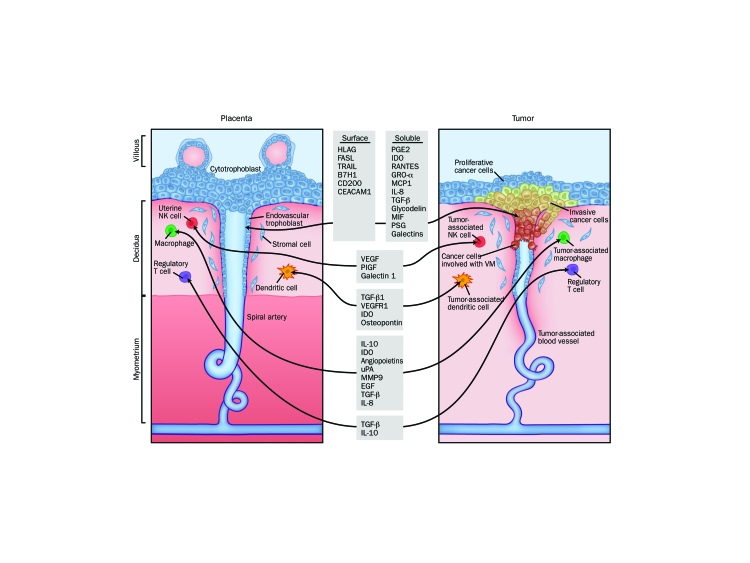

Five days after fertilization, the human zygote forms into a structure consisting of 2 primary cell lines: the inner cell mass (or embryoblast) and the trophoblast.3 Trophoblast cells constitute the outer layer of the blastocyst, rapidly proliferating and invading the maternal endometrial decidua around day 7. A monolayer of cytotrophoblast cells surrounds the embryonic disc as the embryo completely embeds beneath the uterine decidua. By day 9, cytotrophoblast cells have differentiated into 2 distinct cell types: the syncytiotrophoblast and the extravillous trophoblast (EVT). The multinucleated syncytiotrophoblast cells form the external layer and are terminally differentiated. These cells are involved in fetomaternal nutrient exchanges and endocrine functions (such as β-human chorionic gonadotropic production). In contrast, EVT cells have a proliferative and invasive phenotype, migrating through the syncytiotrophoblast into the uterine wall to anchor the placenta beginning around day 14 after implantation.4 These EVT cells display a phenotype strikingly similar to cancer cells with their capacity for proliferation, migration, and establishment of a blood supply, making them a compelling model for oncologic comparison (Figure). This review highlights several shared characteristics of trophoblast and tumor cells and discusses them in the context of existing or developmental targeted cancer therapeutics (Table 1).

FIGURE.

Similarities between the fetomaternal interface and tumor microenvironment. For expansion of all gene symbols, see Glossary of Genetics Terminology at the end of the article. HLA = human leukocyte antigen; IL = interleukin; VM = vasculogenic mimicry.

TABLE 1.

Tumorlike Attributes of the Human Trophoblast Cells and a Selection of Representative Targeted Cancer Therapeutic Strategies in Use or Developmenta

PROLIFERATION

Like tumor cells, trophoblast cells have a very high proliferative capacity and exhibit molecular characteristics found in rapidly dividing cancer cells.54 For example, increased telomerase activity, typically not observed to a substantial degree in normal somatic cells, is detectable in 85% of human cancers.55 In fact, the intracellular concentration of telomerase is exponentially related to the proliferative capacity of a cell.56 In human pregnancy, telomerase activity is highest during the first trimester and decreases with maturation of the placenta.57 Survivin, a protein that promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis, is overexpressed in many cancers58 and is also up-regulated by trophoblast cells.59 Inhibition of survivin by knockdown with small interfering RNA leads to a marked decrease in proliferation in trophoblast cell lines.60 A similar decrease in proliferation is seen with survivin in small interfering RNA treatment of prostate,61 glioma,62 non-Hodgkin lymphoma,63 cervical cancer cells, and breast cancer cells.64 Both survivin and telomerase levels are dramatically higher in hydatidiform moles than in normal placentas, providing insight into the potential involvement of these 2 different mechanisms in neoplastic transformation.59

Another pathway supportive of both trophoblast and cancer cell proliferation is the IGF pathway (for expansion of all gene symbols, see Glossary of Genetics Terminology at the end of the article). By binding to the IGF1R on cytotrophoblast cells, IGF stimulates proliferation through the MAPK pathway and survival via activation of the PI3K pathway.65 Normally, levels of IGF are tightly regulated by IGF-binding proteins and protease pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, a binding protein.66 Loss of binding protein regulation may contribute to the malignant phenotype.67 In cancer cells, the IGF1R pathway is not only mitogenic and antiapoptotic but is involved in protecting cancer cells from damaging effects of chemotherapy and radiation, potentially as a result of its effects on downstream signaling pathways.68 Additionally, the fetal form of the insulin receptor IR-A, which is highly expressed in fetal tissues and responsive to IGF2, is also a member of the IGF-signaling system.69 In many cancers, including those of the breast and ovary, dysregulation of this fetal form of the insulin receptor becomes the predominant isoform leading to IGF2-stimulated proliferation and survival.70,71

INVASION

The sine qua non of both a successful pregnancy and the growth of cancer is the establishment of a blood and nutrient supply, and invasion through normal tissues is required for this process. However, whereas cancer cells spread throughout the host and then engage in local proliferation, trophoblasts follow an organized pattern of differentiation from proliferation to invasion without distant metastasis.72 Some of the molecular switches involved in this differentiation pattern and their relevance for cancer therapeutic agents are discussed in the sections that follow.

As EVT cells migrate down the cytotrophoblast cell columns into the maternal decidua (Figure), they encircle and erode into the maternal spiral arteries and differentiate from a proliferative phenotype into an invasive phenotype.73 This differentiation occurs at about 10 to 12 weeks of gestation and is associated with opening of the intervillous space and exposure to maternal blood. Many parallels can be observed between invasive EVT cells and cancer cells. Some of these similarities are highlighted in the sections to follow; for a more in-depth discussion, readers should refer to excellent reviews by Soundararajan and Rao74 and Ferretti et al.75

Requirements for cellular invasion include changes in cell adhesion molecules, secretion of proteases, and availability of growth factors. An example of a cellular program used by both cancer cells76 and trophoblast cells77 to promote invasion is epithelial-mesenchymal transition, which results in loss of cell-to-cell contact inhibition. Associated with this program are changes in integrin expression and loss of E cadherin, allowing loss of polarity and enhanced motility.78,79 Both trophoblast and cancer cells secrete proteases to degrade extracellular matrix proteins required for dispersal through tissues. The cytoplasm of migratory EVT cells express HSP27, which is correlated with MMP2 activity.80 Basal HSP27 levels are unusually high in cancer cells, protecting them from apoptotic stimuli,81 and are associated with metastatic potential.82 Finally, growth factors such as epidermal growth factor stimulate motility of EVT cells through phosphorylation of p42 and p44 MAPKs and the PI3K-dependent proteins, AKT and p38.83 Epidermal growth factor is associated with tumor cell invasiveness through expression of MMPs.84

Switches involved in triggering trophoblast and cancer cell molecular programs for invasion are not completely understood. The Wnt pathway, a system highly conserved across species involved in cellular proliferation and motility, has recently been implicated in switching trophoblast cells from a proliferative to an invasive phenotype.85 Activation of the Wnt pathway is aberrant in many cancers, resulting in escape of β-catenin from proteosomal degradation, with subsequent β-catenin translocation into the cell nucleus and activation of multiple target genes.86 Although direct activation of β-catenin alone has shown no effect on motility of EVT cells, inhibition of the Wnt—β-catenin pathway can block blastocyst implantation.87 In EVT cells, activation of PAR1 (also known as the thrombin receptor) also stabilizes β-catenin and is associated with a proliferative and invasive capacity, whereas application of PAR1-silencing RNA inhibits EVT invasion.88 Consistent with the need for tight regulation of invasive trophoblast cells, PAR1 is expressed in EVT cells between the 7th and 10th gestational week but is abruptly shut off by the 12th week.89 Constitutive increased expression of PAR1 can be seen in cancer cells, especially in cells lacking normal p53 activity.90 In vitro assays have shown PAR1 antagonism to inhibit MMP1-induced endothelial cell activation in tumor—endothelial cell communication.91 Whether this system could successfully be targeted for cancer therapy is under investigation. Other signal transduction pathways common in both trophoblast and cancer cell invasion include the JAK-STAT pathway,92 FAKs, G proteins, Rho-associated kinase, MAPKs, PI3K, and SMAD family proteins.73 All of these pathways represent areas of current anticancer therapeutic development.

As EVTs acquire an invasive phenotype during placental development, they become polyploid (4N-8N) by switching from mitotic division to endoreduplication,93 a process in which G2 or M phase (4N) cells replicate DNA without undergoing mitosis. In trophoblast cell lines, polyploid trophoblast giant cells are relatively resistant to the DNA-damaging effects of radiation,94 illustrating a mechanism by which survival is promoted in invasive trophoblast cells. This process can also be observed in cancer cells treated with DNA-damaging agents. Endoreduplication can be induced in tumor cells on exposure to genotoxic agents such as paclitaxel95 and cisplatin; a nonproliferative, senescent state in a small population of cells is induced in the latter case. The polyploid tumor cells can undergo depolyploidization to form diploid, cisplatin-resistant escape cells.96 In cells with an impaired p53 system, treatment with the Aurora kinase inhibitor VX-680 leads to endoreduplication followed by apoptosis.22 However, in 2 wild-type p53 cancer cell lines, stabilization of p53 by Nutlin-3a, an inhibitor of the p53-binding protein MDM2, leads to initial endoreduplication followed by the emergence of stable radiation- and cisplatin-resistant tetraploid clones.21 A better understanding of the EVT endoreduplication process may lead to the development of targeted drugs to maintain tumor cell chemotherapeutic sensitivity.

VASCULOGENIC MIMICRY

As trophoblasts invade maternal spiral arteries, they further differentiate to display a vascular phenotype in a process termed vasculogenic mimicry, in which cells other than endothelial cells form vascular structures.97 Vasculogenic mimicry can also be observed in aggressive cancers, and the genes and signaling pathways involved with the process of vasculogenic mimicry may be shared between EVT and cancer cells.98 For example, the matrix glycoprotein—binding galectin 3 is highly expressed in EVT cells.99 Galectin-3 also appears to be a key factor in the development of an endothelial phenotype and the tube formation well described in aggressive melanomas.100 Galectin inhibitors are in preclinical testing as cancer therapeutic agents.101 Mig-7 was found in circulating tumor cells and tumor tissue (regardless of tissue of origin) from more than 200 patients with cancer; notably, it was absent from healthy controls.102 Mig-7 expression is associated with invasion and vasculogenic mimicry in cancer cells and also has recently been demonstrated in invasive embryonic cytotrophoblasts, peaking when EVT cells invade maternal decidua and remodel the vasculature during early placental development.103 This finding represents the only known expression of Mig-7 in noncancerous cells. Cancers with an endothelial phenotype have not been shown to be responsive to antiangiogenic therapies.104 Because cancer therapy aimed at proliferating cells is less likely to be effective in invading cells,105 galactin-3, Mig-7, and other pathways involved in vasculogenic mimicry may also be important targets for cancer therapy.

ANGIOGENESIS

Molecular circuits involved in neoangiogenesis separate from vasculogenic mimicry are also likely shared between EVT and tumor cells. Angiopoietins and VEGF family members are extremely important in both spiral artery remodeling in placentation106 and the growth of many tumor types.107 Inhibition of VEGF has become an important therapeutic strategy in many cancers, although resistance can develop,108 resulting from the induction of an angiogenic rescue program characterized by the up-regulation of multiple angiogenic genes in hypoxic tumor cells and supporting stroma.109,110 Another member of the VEGF family, PGF, is a part of the VEGF blockade—associated rescue program that is involved in the response to pathologic conditions, such as wounds, ischemia, inflammation, or cancer.111 Both VEGF and PGF are highly expressed in trophoblast cells.112 It is interesting that serum levels of PGF increase after treatment of patients with cancer with the anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody bevacizumab.113 Preclinical studies indicate that PGF blockade reduces neoangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis, hampers recruitment of intratumoral macrophages, and is not associated with the typical anti-VEGF adverse effects (thrombosis, hypertension, proteinuria, and microvascular pruning) in healthy mice.110

Also important for angiogenesis is the oxygen-sensitive MTOR pathway.114 Central to controlling trophoblast cell proliferation in response to nutrients and growth factors,115 MTOR is expressed on the transporting epithelium of intact human placenta.116 It is downstream of the PI3K/AKT pathway; controls cell cycle progression and cell size and mass; is involved in angiogenesis via the VEGF, IGF, and HIF-1α—signaling pathways; and is constitutively activated in many malignancies.114,117 The MTOR inhibitor everolimus has antiangiogenic properties.118 A better understanding of the PI3K/AKT/MTOR pathway and other molecular circuits used by trophoblast cells in proliferation, invasion, and endothelial interactions may lead to the development of targeted therapies for cancer.75 Overall, we are in our infancy of understanding the complexity, redundancy, and interrelatedness of these molecular pathways in both placentation and neoplasia.

IMMUNOLOGIC PROPERTIES OF THE FETOMATERNAL INTERFACE AND TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT

In addition to sharing many proliferative and invasive features, the cells of the trophoblast, like cancer cells, actively modulate the host immune response to develop and sustain a nutrient supply. Historically, the placenta was considered an inert, mechanical barrier protecting the semiallogeneic fetus from maternal immunologic attack.119 Current evidence, however, supports just the opposite—many maternal and placental immunomodulatory factors are required for adequate placental invasion. Around 40% of decidual cells are cells of the innate immune system (eg, NK cells, macrophages, and DCs), a substantial proportion considering that the uterus is a nonlymphoid organ.120 Likewise, although cancer previously has been considered immunologically invisible to the host, many recent studies support the notion that cancer cells actively engage immune cells; for example, the presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes has been well described in the literature.121 The main components of the maternal immune response at the fetomaternal interface and the similarities to the tumor microenvironment are discussed in the sections that follow.

The most abundant immune cell present at the fetomaternal interface is the uterine NK (uNK) cell, which constitutes approximately 70% of all immune cells found in this tissue.122 Uterine NK cells are thought to be recruited from peripheral blood when interleukin (IL)-15 is secreted by endometrial stromal cells.123 They are distinct from peripheral blood NK cells in that they do not express CD16, the FcRγIIIA receptor required for antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.120 The mechanisms associated with this loss of CD16 are unclear but may be related to high levels of TGF-β within the microenvironment.124 Also, in contrast to peripheral blood NK cells, uNK cells are more immunomodulatory than cytotoxic, secreting galectin 1 to induce tolerogenic DCs125 as well as angiogenic factors VEGF and PGF that are important for decidual remodeling.126 An improper balance of cytotoxic to regulatory NK cells could contribute to recurrent miscarriage and pre-eclampsia.127 Expression of IL-15 and NK cell infiltration have been reported in many different malignancies,128 including renal cell carcinoma,129 with variable prognostic implications. Recently, tumor-infiltrating CD16-NK cells have also been characterized and appear to behave similarly to uNK cells with respect to cytokine production and reduced cytotoxic activity.130 A closer look at factors that determine the balance of killer and regulatory NK cells during pregnancy may help identify mechanisms that shift immunity toward NK cytotoxic activity in patients with cancer.

Also infiltrating the decidua, albeit in smaller numbers than uNK cells, are macrophages, Treg, and DCs. Macrophages phagocytose apoptotic EVT cells and secrete IL-10 and IDO, contributing to the tolerogenic TH2 milieu.131 Gene expression profiling of decidual macrophages supports an immunosuppressive/anti-inflammatory phenotype with higher expression of CCL18, IGF1, IDO, neuropilin 1, and other genes associated with M2-polarized macrophages.132 Tumor-associated macrophages can be both inflammatory and immunosuppressive, and TH1/TH2 polarization is effected through the activation of NF-κB (also known as NFKB1).133 In fact, in vitro studies suggest that tumor-associated macrophages may be re-educated to display a classically activated rather than an M2 phenotype by inhibition of inhibitory kappa B kinase β, the major activator of NF-κB.134

Regulatory T cells are additional important mediators of tolerance in both pregnancy and cancer. Immunophenotypically, these cells express surface CD4, CD25, and FOXP3, and they expand in both decidua135 and peripheral blood136 during normal pregnancies. This expansion is antigen-specific and is induced by paternal/fetal alloantigens137 and not simply by hormonal changes in pregnancy.138 A decrease in this lymphocyte subset is associated with spontaneous abortion139 and pre-eclampsia.140 Regulatory T cells are also expanded in cancer and are implicated in impaired antitumor immunity,141 suppression of effector T lymphocyte proliferation,142 and increased tumor blood vessel density,143 suggesting an important link between immunity and angiogenesis. Regulatory T cells in patients with cancer also recognize tumor-specific antigens and proliferate in response to antigenic stimulation.144 Targeting the Treg population to boost antitumor immunity is under investigation with agents such as denileukin diftitox (IL2/diphtheria fusion protein) or LMB-2 (Fv fragment of CD25 antibody/Pseudomonas endotoxin A fusion protein) and CTLA-4 inhibitors.145,146 Some of the benefit of cytotoxic chemotherapy may be derived from concomitant impairment of the immunosuppressive Treg proliferation driven by the cancer.147

Antigen-presenting CD83+ DCs are involved in the maintenance of the TH2-predominant state in decidual tissues,148 as well as at other mucosal surfaces.149 However, the role of the DC is likely more complex than antigen presentation and secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines. Ablation of uterine DCs leads to decidualization failure and embryo resorption in mice; this occurs even with syngeneic pregnancy in mice in which alloantigens are absent.150 Dendritic cells also represent another link between immunity and angiogenesis, secreting soluble FLT1 (also known as VEGFR1) and TGF-β1 required for endothelial cell survival and vascular maturation. In the absence of DCs, angiogenesis is severely impaired. In cancer, DCs also play a role that is more than immunoregulatory through their production of potent angiogenic growth factors. Moreover, cancer cells can secrete substances that suppress maturation of DCs, including VEGF, TGF-β, hepatocyte growth factor, and osteopontin, thereby maintaining a proangiogenic, immature DC phenotype.151

Expression of certain cell surface molecules on both trophoblast and cancer cells can also confer immunologic protection. Among the most important of these molecules is the nonpolymorphic, highly conserved class I human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules such as HLAG152; in contrast, the highly diverse classical HLA class I proteins A, B, and C are essential in cell-mediated immune responses. In fact, in trophoblast cells, interferon-γ fails to stimulate classical HLA class I expression.153 A similar property of down-regulated or absent classical HLA class I expression can cloak cancer cells from the host's immune system.154 Cancer treatment modalities including gamma irradiation,29 radiopharmaceutical samarium-153-ethylenediaminetetramethylenephosphonate,30 and chemotherapeutic agents such as 5-fluorouracil155 and hypomethylating agents156 increase HLA class I expression.

Expression of HLAG on trophoblast cells and cancer cells has important immunomodulatory effects. In the placenta, HLAG expression is most evident on EVTs at the fetomaternal interface, with lower expression at the proliferative area of the villous column and increased expression with invasive, interstitial, and endovascular EVT cells.157 On the basis of sequence homologies, HLAG has been proposed as the ancestral MHC class I gene and has only a few known sequence variations in humans, in sharp contrast to the profound allelic diversity (measured in the hundreds of allelic variants) of classical MHC class I genes.158 Human leukocyte antigen-G interacts with NK cells via inhibitory receptors, such as CD94/NKG2A, ILT2, and killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor KIR2DL4.120 The role of HLAG is to suppress cytolytic killing by both NK and cytotoxic T cells, induce apoptosis of immune cells, regulate cytokine production in blood mononuclear cells, and reduce stimulatory capacity and impair maturation of DCs (reviewed in Hunt et al159). Within the tumor microenvironment, the generation of HLAG+—suppressive NK cells occurs by trogocytosis (ie, the rapid cell-to-cell contact-dependent transfer of membranes and associated molecules from one cell to another), leading to the inhibition of other HLAG+ (cross-inhibition) or HLAG- NK cells through HLAG and ILT2 cross-linking.160 Expression of HLAG is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders,161 melanoma,162 mesothelioma,163 breast carcinoma,163 ovarian carcinoma,164 renal cell carcinoma,165 squamous esophageal cancer,166 gastric carcinoma,167 cervical cancer,168 non—small cell lung cancer,169 bladder cancer,170 prostate cancer,171 endometrial cancer,172 colorectal cancer,173 and myeloid malignancies, including acute myeloid leukemia.174,175 However, relatively little is known about the regulation of the expression of this important immunomodulatory molecule.174 Regulation of HLAG expression may be at the epigenetic level, with transcription of HLAG being detectable in acute myeloid leukemia cell lines after treatment with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine.32 Some preliminary evidence also supports a micro-RNA regulatory mechanism.176 Clearly, HLAG represents an attractive target for immune-based cancer therapies given its preferential expression in many malignancies as well as limited expression in normal tissues.177 Targeting HLAG with a peptide-based vaccine strategy to develop a cytotoxic T-cell response against tumor cells bearing the molecule has proved feasible,178 although much work remains before other methods of HLAG inhibition could lead to restoration of antitumor immunity.

Other cell surface tolerance signals common between trophoblasts and cancer cells include CD200 (OX-2) and CEACAM-1. Trophoblast cells expressing CD200 can inhibit CD8+ T cytotoxic lymphocyte (CTL) generation and shift the cytokine balance toward TH2 in vitro.179 Expression of CD200 is a negative prognostic factor in patients with multiple myeloma180 and acute myeloid leukemia,181 and it has been shown to down-regulate TH1 cytokines in vitro in solid tumors, including melanomas, ovarian carcinomas, and renal cell carcinomas.182 As a potential cancer stem cell marker, CD200 may be a promising target for these cells that survive conventional chemotherapy.183 CEACAM-1 (CD66a), expressed on both trophoblasts and IL-2-activated decidual leukocytes, plays a role in inhibiting NK-mediated cytolysis.184 Colocalization of osteopontin on EVT cells is associated with an invasive phenotype important for successful placentation.185 CEACAM-1 expression in cancer is associated with increased angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer186; in melanoma, it has been shown to be predictive of the development of metastatic disease.187 Expression of other immunomodulatory molecules, including components of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway such as FAS, TNF superfamily receptors,188 TRAIL,189 and B7 family members such as B7H1 (or programmed death ligand 1, PDL-1),190 is also common between trophoblast and cancer cells (Table 1).

Chemokines and cytokines also play a role in promoting a tolerogenic environment in placentation and the tumor microenvironment. Implantation of the blastocyst occurs in a TH1-predominant (inflammatory) milieu, but the fetomaternal interface must transition to a TH2-polarized (immunologically tolerant) state for pregnancy to continue (for an excellent review, refer to van Mourik et al191). However, before implantation can occur, the endometrial lining must be receptive in the so-called window of implantation, in which many immunomodulatory genes are up-regulated monthly during the midsecretory phase of the menstrual cycle.191 Under the influence of progesterone, the endometrial epithelium up-regulates decay-accelerating factor and osteoponin expression, and the endometrial stroma increases IL-15 expression.192,193 Expression of complement regulatory proteins (eg, decay-accelerating factor) is a well-established immunomodulatory mechanism used by many cancers to escape complement-mediated cell death and evade an immune response by inhibiting T-cell proliferation.194 Osteopontin has TH1 cytokine functions and is chemotactic for macrophages, T cells, and DCs, the last of which it induces to secrete IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α).195,196 Osteopontin is overexpressed in many cancers and is associated with metastatic potential.197 Additionally, tissues that physiologically express high levels of osteopontin, such as bone, lung, and liver, may create a receptive microenvironment for metastasis via interaction with osteopontin receptor CD44 on the surface of cancer cells.198

RANTES (CCL5) is a chemokine produced by trophoblasts that may play a role in apoptosis of potentially harmful maternal CD3+ cells.199 Melanoma cells can induce tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to secrete RANTES and subsequently undergo apoptosis as another mechanism to evade an immune response.200 Trophoblast cells also secrete chemoattractant cytokines, such as GRO-α, MCP1, and IL-8, to actively recruit the CD14+ monocytes to the fetomaternal interface.201 GRO-α is an oncogenic and angiogenic cytokine driven by RAS, which is inappropriately activated in most cancers.202 Capable of inducing vascular permeability along with mononuclear cell recruitment, MCP1 is associated with angiogenesis and malignant pleural effusions.203 Inhibition of MCP1 can lead to reduced malignant angiogenesis and recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages in a mouse model of melanoma.204 Finally, the IL-8 pathway is well known to be a central immune and angiogenic factor within the tumor microenvironment and is important in stress-induced chemotherapeutic resistance.205

A tryptophan-catabolizing enzyme, IDO is important in promoting tolerance by inhibiting proliferation of lymphocytes both at the fetomaternal interface206 and tumor microenvironment.207 Tryptophan levels have been observed to decrease in pregnancy with a return to normal, nonpregnant levels in the puerperium,208 possibly a result of tryptophan degradation by IDO-expressing trophoblast cells. Expression of HLAG on DCs can be induced by IDO, indicating potential cooperation in immune suppression between these 2 molecules.209 Tumor-derived PGE2 secretion can increase IDO expression in local DCs.210 Antigen-expressing cells and IDO-expressing tumor cells might also contribute to local immunosuppression in tumor-draining lymph nodes.211 Pharmacologic inhibitors of IDO are under development and in early-stage clinical trials as anticancer agents.207 Induction of IDO can also be blocked in vitro by cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors.212 When murine breast cancer vaccine recipients received the oral cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor celecoxib, an increase in tumor-specific CTLs was observed.35

Trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling are tightly controlled processes, likely kept in check both by molecular programming of trophoblast cells and by paracrine immune factors.213 We have much to gain in terms of developing novel immunologic interventions for our patients with cancer by closely examining both the similarities and differences of the intimate cross-talk that occurs within the tumor and placental microenvironments.

EVIDENCE FOR SYSTEMIC IMMUNE MODULATION

Similar to the increasing antigenic burden of progressive cancer,214 fetal DNA can be found circulating in maternal blood by the second trimester in the height of the tolerogenic cytokine milieu.215 Although its immunologic consequences have not been fully elucidated, this circulating DNA likely contributes to tolerance and eventual exhaustion of antigen-specific CTLs. This phenomenon is well described for the human immunodeficiency virus, chronic infection with which leads to progressive HIV-specific T cell dysfunction.216 In addition to circulating nucleic acids, cellular fragments, known as microparticles or exosomes, can be detected in the peripheral blood of pregnant women in the third trimester.217 Trophoblast-derived microparticles are proinflammatory, activate the coagulation system, can cause endothelial dysfunction, and are circulating at higher levels in pre-eclamptic vs normal pregnancies.218 These microparticles are also involved in down-regulation of T-cell activity and deletion of activated T cells through interactions with FAS or TRAIL on the microparticle surface.219 A similar phenomenon of cancer cell-derived microparticles contributing to the hypercoagulable state and impaired antitumor immunity of patients with cancer has been described (reviewed in Amin et al220). Microparticles derived from melanoma cells have been shown to express HLAG, likely contributing to their immunomodulatory properties.221

Just as circulating tumor cells have been identified in patients with early-stage malignancies,222 intact trophoblast cells are also known to circulate in the maternal peripheral blood as early as the ninth week of pregnancy.223 These fetally derived cells can engraft in the mother irrespective of HLA disparity and establish a long-term microchimerism that persists for decades after parturition.224 Rates of fetal microchimerism are decreased in female patients with cancer (34%) compared with healthy controls (57%), and the immunomodulatory implications of this decrease are unclear.225 An increased number of fetal microchimeric cells in aggressive breast carcinoma226 and melanoma227 during pregnancy have been observed. Whether these cells were recruited to the tumor microenvironment by inflammation and behave as innocent bystanders or whether they participate in tumor progression by providing angiogenic or tolerogenic signals is unclear at this time.

Many additional immunomodulatory proteins are secreted by trophoblast cells and can be found circulating in maternal peripheral blood. Among these molecules, soluble HLAG may be the most extensively studied.228 Soluble HLAG impairs NK/DC cross-talk, promotes proinflammatory cytokine secretion from both uterine and peripheral blood mononuclear cells,229 and induces apoptosis of CD8+ cells through CD8 ligation230 and FAS-FASL interaction.231 Soluble HLAG has been well documented in malignancies,174 including acute leukemia,232 multiple myeloma,233 lymphoproliferative disorders,234 breast and ovarian carcinoma,163 renal cell carcinoma,165,235 lung cancer,236 gliomas,237 and melanoma.238 Cancer cells can also trigger monocytes to release HLAG, further down-regulating antitumor immunity.239 Whether HLAG can be targeted to break cancer-specific tolerance remains to be investigated.

A search for other immunomodulatory molecules from conditioned media of placental tissue has yielded interesting results. Surprisingly, no interleukins were identified by either proteomic analysis or sensitive radioimmunoassays; rather, in addition to pregnancy-associated hormones, substances including PSG1, glycodelin, TGF-β2, thrombospondin-1, PEDF, MIF, and galectin 1 were identified as important immunoregulators in pregnancy.240 Many of these substances have been identified in cancer as well. For example, PSGs may not be pregnancy specific at all. Pregnancy-specific glycoprotein 9 deregulation is an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis.241 Expressed frequently in lung carcinomas,169 PSG1 is associated with estrogen receptor negativity and a higher risk of death in early-stage breast cancer.242 Glycodelin may be involved in tumor angiogenesis by increasing VEGF release in many cell lines.243 An inhibitor of TGF-β2 (overexpressed in many cancers) is in phase 1/2 cancer clinical trials.13 Thrombospondin 1 is an endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor, although its expression in tumor stroma may render tumor cells insensitive to VEGF and help maintain tumor cell dormancy.244 Another endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor, PEDF, may have anti-invasive effects on tumor cells.245 MIF can stabilize HIF-1α, a factor central to cellular response to hypoxia.246 Galectin1 expression within tumors and the stromal tissues is positively correlated with cancer aggressiveness247 and a diminished T-cell response.248

Another soluble immunomodulator, soluble CD30, a member of the tumor necrosis superfamily of receptors and marker of TH2 polarization, is increased in women with normal pregnancies and reduced in those with preeclampsia and intrauterine growth retardation.249 In addition to being prognostic in patients with CD30+ classical Hodgkin lymphoma,250 soluble CD30 is a potential marker of chronic B cell hyperactivation and can predict those at risk of AIDS-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma.251 The identification of common immunomodulators helps expand the concept of tolerance in pregnancy and cancer beyond TH2 and toward a more complete understanding of chronic inflammation, angiogenesis, and immunologic privilege.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CANCER THERAPEUTICS

As a healthy pregnancy progresses toward parturition, several changes within the mother reflect a restoration of active, TH1-predominant immunity. Although Treg levels stay constant until the postpartum period,252 a gradual return of CD16+ NK cells is observed in late pregnancy.253 Suppressed earlier in pregnancy, circulating cytotoxic γδ-T cells increase with the onset of labor.254 Interleukin 2 levels decrease while granulocyte macrophage colony—stimulating factor and interferon-γ increase through the third trimester and even more markedly at the onset of labor.255 Increased expression of genes associated with acute inflammation and neutrophil and monocyte influx has been observed in human fetal membranes at parturition.256,257 Concomitant with an increase in the potent uterine contractile prostanoid PGF-2α, proinflammatory cytokines and MMPs prepare the uterus for labor.258 Markedly down-regulated at term compared with midgestation are genes involved in angiogenesis, such as angiopoietin 2.259 Taken together, these changes support a transition from a TH2 to a TH1 polarity during the third trimester.

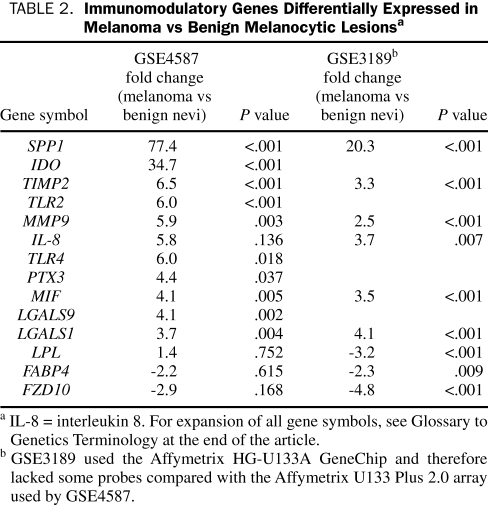

In contrast, patients with advanced malignancies continue to experience a progressive failure of antitumor immunity, which has been associated with a TH2-polarization and VEGF-driven chronic inflammation.260 We have identified the expression of immunomodulatory genes known to be supportive of pregnancy in our own patients with metastatic melanoma via gene-expression profiling (unpublished data). We have also verified that these immunomodulatory genes are differentially expressed in melanoma vs benign melanocytic nevi in 2 independent publically available datasets from the National Center for Biotechnology Information/GenBank GEO database: GSE4587,261 which was analyzed on the GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array platform (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), and GSE3189,262 which was analyzed on the GeneChip Human Genome U133 Array Set HG-U133A platform (Affymetrix). We selected approximately 70 immunomodulatory genes on the basis of our critical review of the obstetrics literature, log-transformed the raw data, and performed an analysis of variance on this gene set on Partek 6.4 software. A summary of results is listed in Table 2. Osteopontin and other important components of innate immunity such as TLR2 and TLR4 and PTX3 were significantly up-regulated in melanoma compared with benign nevi. Galectins 1 and 9 were also significantly up-regulated compared with nevi. Notably down-regulated in melanoma were genes known to be up-regulated in term placenta,259,263 including LPL, FABP4, and FZD10 (a Wnt receptor). Overall, this pattern is supportive of our theory that tumor cells use similar mechanisms of immune escape as those cells of the developing placenta, although these similarities have not yet been studied in a systematic fashion. Given what we have learned about the similarities between the placenta and tumor microenvironment, we plan to next comprehensively evaluate changes in systemic immune homeostasis in pregnancy vs cancer in order to prioritize potential therapeutic targets. In particular, identifying immunologic distinctions between pregnancy and cancer will be critical for this process.

TABLE 2.

Immunomodulatory Genes Differentially Expressed in Melanoma vs Benign Melanocytic Lesionsa

CONCLUSION

By comparing immunologic patterns throughout healthy pregnancies, and in particular the return to TH1-polarized immunity through the third trimester, with those patterns observed in advanced malignancies, we have an opportunity to learn potential mechanisms to overcome the burden of long-term antigenic exposure and immunologic exhaustion in patients with cancer. The challenge for investigators in this field will be to extend our observations beyond the TH1/TH2 paradigm in both pregnancy and cancer to a model that can both assess the status and guide treatment of malignancies in an individualized, rational, real-time manner. A critical need exists for the development of treatments aimed at all aspects of cancer: malignant proliferation, invasion, vasculogenic mimicry, angiogenesis, and immune privilege. Studying how all these aspects are orchestrated in the predictable, physiologic process of pregnancy can facilitate the search for novel cancer treatment strategies, from cytotoxic chemotherapy to biologic agents and immunologic adjuncts, in the often unpredictable and arduous fight against the pathologic process of cancer.

Supplementary Material

Glossary of Genetics Terminology

- AKT

v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog

- ALK

anaplastic lymphoma receptor tyrosine kinase

- BCL2

B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma 2

- CDK

cyclin dependent kinase

- CEACAM1

carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (biliary glycoprotein)

- CMET (also known as MET)

met proto-oncogene (hepatocyte growth factor) receptor

- CSF

colony-stimulating factor

- CSF1R

CSF type 1 receptor

- CXCR4

chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4

- EGF

epidermal growth factor (beta-urogastrone)

- ERK

extracellular signal—related kinase

- FABP4

fatty acid—binding protein 4

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- FAS

Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6)

- FASL

FAS ligand

- FCγIIIA

FC gamma receptor III A

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FLT1

fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 (vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor receptor)

- FOXP3

forkhead box P3

- FZD10

frizzled homolog 10

- GRO-α

growth-related oncogene α

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducible factor 1α

- HSP27

heat shock protein 27

- IDO

indoleamine 2, 3 dioxygenase

- IGF

insulinlike growth factor

- IGF1R

IGF type 1 receptor

- ILT2

Ig-like transcript 2

- JAK

janus kinase

- LGALS1

galactin 1

- LGALS9

galactin 9

- LPL

lipoprotein lipase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCP1

monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

- MEK (also known as MAP2K)

MAPK/ERK kinase

- MIF

macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- Mig-7

migration-induction protein 7

- MDM2

mouse double minute 2

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- MUC1

mucin 1

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- p38

tumor protein 38

- PAR1

protease activated receptor 1

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PDGFR

PDGF receptor

- PEDF

pigment epithelial—derived factor

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PGF

placental growth factor

- PI3K

phosphoinositide-3 kinase

- PSG1

pregnancy-specific glycoprotein 1

- PTX3

pentraxin 3

- RANTES (also known as CCL5)

regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted

- RAF

v-raf-1 murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1

- RAS

rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- SDF (also known as CXCL12)

stromal-derived factor 1

- SPP1

osteopontin

- STAT

signal transducers and activator of transcription

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TIM3 (also known as HAVCR2)

T cell immunoglobulin mucin 3

- TIMP2

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- TRAILR

TRAIL receptor

- uPA

urokinase plasminogen activator

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

VEGF receptor

- waf1/cip1 (also known as CDKN1A)

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A

- Wnt

wingless/T-cell factor

- XIAP

X-link inhibitor of apoptosis protein

Footnotes

A glossary of genetics terminology appears at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Medawar PB. Some immunological and endocrinological problems raised by the evolution of viviparty in vertebrates. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1953;7:320-338 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke CA. Immunology of pregnancy: significance of blood group incompatibility between mother and foetus. Proc R Soc Med. 1968;61(11, pt 2):1213-1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staun-Ram E, Shalev E. Human trophoblast function during the implantation process. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005October;3:56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lunghi L, Ferretti ME, Medici S, Biondi C, Vesce F. Control of human trophoblast function. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2007February8;5:6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fecher LA, Amaravadi RK, Flaherty KT. The MAPK pathway in melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20(2):183-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ihle NT, Powis G. Take your PIK: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors race through the clinic and toward cancer therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(1):1-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu TJ, LaFortune T, Honda T, et al. Inhibition of both focal adhesion kinase and insulin-like growth factor-I receptor kinase suppresses glioma proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(4):1357-1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martens T, Schmidt NO, Eckerich C, et al. A novel one-armed anti-c-Met antibody inhibits glioblastoma growth in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20, pt 1):6144-6152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jun HT, Sun J, Rex K, et al. AMG 102, a fully human anti-hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor neutralizing antibody, enhances the efficacy of temozolomide or docetaxel in U-87 MG cells and xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(22, pt 1):6735-6742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Echeverría C, Pearson MA, Marti A, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of NVP-AEW541-A novel, potent, and selective inhibitor of the IGF-IR kinase. Cancer Cell 2004;5(3):231-239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conway JG, McDonald B, Parham J, et al. Inhibition of colony-stimulating-factor-1 signaling in vivo with the orally bioavailable cFMS kinase inhibitor GW2580. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005November1;102(44):16078-16083 Epub 2005 Oct 25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irvine KM, Burns CJ, Wilks AF, Su S, Hume DA, Sweet MJ. A CSF-1 receptor kinase inhibitor targets effector functions and inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine production from murine macrophage populations. FASEB J. 2006September;20(11):1921-1923 Epub 2006 Jul 28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlingensiepen KH, Fischer-Blass B, Schmaus S, Ludwig S. Antisense therapeutics for tumor treatment: the TGF-beta2 inhibitor AP 12009 in clinical development against malignant tumors. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2008;177:137-150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yingling JM, Blanchard KL, Sawyer JS. Development of TGF-β signalling inhibitors for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(12):1011-1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen R, Wierda WG, Chubb S, et al. Mechanism of action of SNS-032, a novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2009May7;113(19):4637-4645 Epub 2009 Feb 20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Squires MS, Feltell RE, Wallis NG, et al. Biological characterization of AT7519, a small-molecule inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases, in human tumor cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009February;8(2):324-332 Epub 2009 Jan 27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tojo M, Hamashima Y, Hanyu A, et al. The ALK-5 inhibitor A-83-01 inhibits Smad signaling and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by transforming growth factor-β. Cancer Sci. 2005;96(11):791-800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weroha SJ, Haluska P. IGF-1 receptor inhibitors in clinical trials--early lessons. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2008December;13(4):471-483 Epub 2008 Nov 21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haluska P, Shaw HM, Batzel GN, et al. Phase I dose escalation study of the anti insulin-like growth factor-I receptor monoclonal antibody CP-751,871 in patients with refractory solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(19):5834-5840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lacy MQ, Alsina M, Fonseca R, et al. Phase I, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the anti-insulinlike growth factor type 1 Receptor monoclonal antibody CP-751,871 in patients with multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2008July;26(19):3196-3203 Epub 2008 May 12A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen H, Moran DM, Maki CG. Transient nutlin-3a treatment promotes endoreduplication and the generation of therapy-resistant tetraploid cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(20):8260-8268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gizatullin F, Yao Y, Kung V, Harding MW, Loda M, Shapiro GI. The Aurora kinase inhibitor VX-680 induces endoreduplication and apoptosis preferentially in cells with compromised p53-dependent postmitotic checkpoint function. Cancer Res. 2006;66(15):7668-7677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prasad S, Kaur J, Roy P, Kalra N, Shukla Y. Theaflavins induce G2/M arrest by modulating expression of p21waf1/cip1, cdc25C and cyclin B in human prostate carcinoma PC-3 cells. Life Sci. 2007October13;81(17-18):1323-1331 Epub 2007 Sep 15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phase I study on monoclonal antibody TB-403 directed against PlGF in patients with solid tumours ClinicalTrials.gov Web site. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00702494 First received June 19, 2008. Last updated September 5, 2008. Accessed June 17, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Yodkeeree S, Chaiwangyen W, Garbisa S, Limtrakul P. Curcumin, demethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin differentially inhibit cancer cell invasion through the down-regulation of MMPs and uPA. J Nutr Biochem. 2009February;20(2):87-95 Epub 2008 May 20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee KJ, Hwang SJ, Choi JH, Jeong HG. Saponins derived from the roots of Platycodon grandiflorum inhibit HT-1080 cell invasion and MMPs activities: regulation of NF-κB activation via ROS signal pathway. Cancer Lett. 2008September;268(2):233-243 Epub May 21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuynman JB, Vermeulen L, Boon EM, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition inhibits c-Met kinase activity and Wnt activity in colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(4):1213-1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karp I, Behlouli H, Lelorier J, Pilote L. Statins and cancer risk. Am J Med. 2008;121(4):302-309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiriva-Internati M, Grizzi F, Pinkston J, et al. Gamma-radiation upregulates MHC class I/II and ICAM-I molecules in multiple myeloma cell lines and primary tumors. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2006;42(3-4):89-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chakraborty M, Wansley EK, Carrasquillo JA, et al. The use of chelated radionuclide (samarium-153-ethylenediaminetetramethylenephosphonate) to modulate phenotype of tumor cells and enhance T cell-mediated killing. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(13):4241-4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adair SJ, Hogan KT. Treatment of ovarian cancer cell lines with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine upregulates the expression of cancer-testis antigens and class I major histocompatibility complex-encoded molecules. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009April;58(4):589-601 Epub 2008 Sep 13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poláková K, Bandzuchová E, Kuba D, Russ G. Demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine activates HLA-G expression in human leukemia cell lines. Leuk Res. 2009April;33(4):518-524 Epub 2008 Sep 26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zweifel BS, Davis TW, Ornberg RL, Masferrer JL. Direct evidence for a role of cyclooxygenase 2-derived prostaglandin E2 in human head and neck xenograft tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62(22):6706-6711 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macor P, Tripodo C, Zorzet S, et al. In vivo targeting of human neutralizing antibodies against CD55 and CD59 to lymphoma cells increases the antitumor activity of rituximab. Cancer Res. 2007;67(21):10556-10563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basu GD, Tinder TL, Bradley JM, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor enhances the efficacy of a breast cancer vaccine: role of IDO. J Immunol. 2006;177(4):2391-2402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jia L, Schweikart K, Tomaszewski J, et al. Toxicology and pharmacokinetics of 1-methyl-d-tryptophan: absence of toxicity due to saturating absorption. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008January;46(1):203-211 Epub 2007 Aug 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charrad RS, Li Y, Delpech B, et al. Ligation of the CD44 adhesion molecule reverses blockage of differentiation in human acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 1999;5(6):669-676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song EY, Qu CF, Rizvi SM, et al. Bismuth-213 radioimmunotherapy with C595 anti-MUC1 monoclonal antibody in an ovarian cancer ascites model. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008January;7(1):76-80 Epub 2007 Oct 8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richman CM, Denardo SJ, O'Donnell RT, et al. High-dose radioimmunotherapy combined with fixed, low-dose paclitaxel in metastatic prostate and breast cancer by using a MUC-1 monoclonal antibody, m170, linked to indium-111/yttrium-90 via a cathepsin cleavable linker with cyclosporine to prevent human anti-mouse antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(16):5920-5927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mac Gabhann F, Popel AS. Targeting neuropilin-1 to inhibit VEGF signaling in cancer: comparison of therapeutic approaches. PLOS Comput Biol. 2006December29;2(12):e180 Epub 2006 Nov 16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson RH, Dong H, Kwon ED. Implications of B7-H1 expression in clear cell carcinoma of the kidney for prognostication and therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007January;13(2, pt 2):709s-715s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verbrugge I, Wissink EH, Rooswinkel RW, et al. Combining radiotherapy with APO010 in cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2009March15;15(6):2031-2038 Epub 2009 Mar 10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorgham K, Abadie V, Iga M, Hartley O, Gorochov G, Combadière B. Engineered CCR5 superagonist chemokine as adjuvant in anti-tumor DNA vaccination. Vaccine 2008June19;26(26):3252-3260 Epub 2008 Apr 24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson DE. TIM-3 as a therapeutic target in human inflammatory diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2007;11(8):1005-1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Navabi H, Jasani B, Reece A, et al. A clinical grade poly I:C-analogue (Ampligen) promotes optimal DC maturation and Th1-type T cell responses of healthy donors and cancer patients in vitro. Vaccine 2009January1;27(1):107-115 Epub 2008 Oct 31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prins RM, Craft N, Bruhn KW, et al. The TLR-7 agonist, imiquimod, enhances dendritic cell survival and promotes tumor antigen-specific T cell priming: relation to central nervous system antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2006;176(1):157-164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chauhan D, Li G, Podar K, et al. A novel carbohydrate-based therapeutic GCS-100 overcomes bortezomib resistance and enhances dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(18):8350-8358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delaine T, Cumpstey I, Ingrassia L, et al. Galectin-inhibitory thiodigalactoside ester derivatives have antimigratory effects in cultured lung and prostate cancer cells. J Med Chem. 2008;51(24):8109-8114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kretz-Rommel A, Qin F, Dakappagari N, Cofiell R, Faas SJ, Bowdish KS. Blockade of CD200 in the presence or absence of antibody effector function: implications for anti-CD200 therapy. J Immunol. 2008;180(92):699-705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Clercq E. Potential clinical applications of the CXCR4 antagonist bicyclam AMD3100. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2005;5(9):805-824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richert MM, Vaidya KS, Mills CN, et al. Inhibition of CXCR4 by CTCE-9908 inhibits breast cancer metastasis to lung and bone. Oncol Rep. 2009;21(3):761-767 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gong M, Lu Z, Fang G, Bi J, Xue X. A small interfering RNA targeting osteopontin as gastric cancer therapeutics. Cancer Lett. 2008December8;272(1):148-159 Epub 2008 Aug 9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sekulic A, Haluska P, Jr, Miller AJ, et al. Melanoma Study Group of Mayo Clinic Cancer Center Malignant melanoma in the 21st century: the emerging molecular landscape. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(7):825-846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bulmer JN, Morrison L, Johnson PM. Expression of the proliferation markers Ki67 and transferrin receptor by human trophoblast populations. J Reprod Immunol. 1988;14(3):291-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, et al. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science 1994;266(5193):2011-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blagoev KB. Cell proliferation in the presence of telomerase. PLoS One 2009;4(2):e4622 Epub 2009 Feb 27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kyo S, Takakura M, Tanaka M, et al. Expression of telomerase activity in human chorion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241(2):498-503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li F, Ambrosini G, Chu EY, et al. Control of apoptosis and mitotic spindle checkpoint by survivin. Nature 1998;396(6711):580-584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lehner R, Bobak J, Kim NW, Shroyer AL, Shroyer KR. Localization of telomerase hTERT protein and survivin in placenta: relation to placental development and hydatidiform mole. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):965-970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fest S, Brachwitz N, Schumacher A, et al. Supporting the hypothesis of pregnancy as a tumor: survivin is upregulated in normal pregnant mice and participates in human trophoblast proliferation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59(1):75-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shen J, Liu J, Long Y, et al. Knockdown of survivin expression by siRNAs enhances chemosensitivity of prostate cancer cells and attenuates its tumorigenicity. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2009;41(3):223-230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhen HN, Li LW, Zhang W, et al. Short hairpin RNA targeting survivin inhibits growth and angiogenesis of glioma U251 cells. Int J Oncol. 2007;31(5):1111-1117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Congmin G, Mu Z, Yihui M, Hanliang L. Survivin--an attractive target for RNAi in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, Daudi cell line as a model. Leuk Lymphoma 2006;47(9):1941-1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li QX, Zhao J, Liu JY, et al. Survivin stable knockdown by siRNA inhibits tumor cell growth and angiogenesis in breast and cervical cancers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006July;5(7):860-866 Epub 2006 Jul 9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Forbes K, Westwood M, Baker PN, Aplin JD. Insulin-like growth factor I and II regulate the life cycle of trophoblast in the developing human placenta. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008June;294(6):C1313-C1322 Epub 2008 Apr 9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boldt HB, Conover CA. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A): a local regulator of IGF bioavailability through cleavage of IGFBPs. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2007February;17(1):10-18 Epub 2007 Jan 10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pollak M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia [published correction appears in Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(3):224] Nat Rev Cancer 2008;8(12):915-928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tao Y, Pinzi V, Bourhis J, Deutsch E. Mechanisms of disease: signaling of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor pathway--therapeutic perspectives in cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4(10):591-602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hill DJ, Petrik J, Arany E. Growth factors and the regulation of fetal growth. Diabetes Care 1998;21(suppl 2):B60-B69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Papa V, Pezzino V, Costantino A, et al. Elevated insulin receptor content in human breast cancer. J Clin Invest 1990;86(5):1503-1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kalli KR, Conover CA. The insulin-like growth factor/insulin system in epithelial ovarian cancer. Front BioSci. 2003May1;8:d714-d722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marco DE, Cannas SA, Montemurro MA, Hu B, Cheng SY. Comparable ecological dynamics underlie early cancer invasion and species dispersal, involving self-organizing processes. J Theor Biol. 2009January7;256(1):65-75 Epub 2008 Oct 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pollheimer J, Knöfler M. Signalling pathways regulating the invasive differentiation of human trophoblasts: a review. Placenta 2005;26(suppl A):S21-S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Soundararajan R, Rao AJ. Trophoblast ‘pseudo-tumorigenesis’: significance and contributory factors. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004March25;2:15 doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferretti C, Bruni L, Dangles-Marie V, Pecking AP, Bellet D. Molecular circuits shared by placental and cancer cells, and their implications in the proliferative, invasive and migratory capacities of trophoblasts. Hum Reprod Update 2007Mar–Apr;13(2):121-141 Epub 2006 Oct 26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang J, Weinberg RA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev Cell 2008;14(6):818-829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vicovac L, Aplin JD. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition during trophoblast differentiation. Acta Anat (Basel) 1996;156(3):202-216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Floridon C, Nielsen O, Holund B, et al. Localization of E-cadherin in villous, extravillous and vascular trophoblasts during intrauterine, ectopic and molar pregnancy. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6(10):943-950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Blechschmidt K, Mylonas I, Mayr D, et al. Expression of E-cadherin and its repressor snail in placental tissue of normal, preeclamptic and HELLP pregnancies. Virchows Arch. 2007;450(2):195-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matalon ST, Drucker L, Fishman A, Ornoy A, Lishner M. The role of heat shock protein 27 in extravillous trophoblast differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103(3):719-729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jäättelä M. Escaping cell death: survival proteins in cancer. Exp Cell Res. 1999;248(1):30-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ciocca DR, Calderwood SK. Heat shock proteins in cancer: diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, and treatment implications. Cell Stress Chaperones 2005;10(2):86-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.LaMarca HL, Dash PR, Vishnuthevan K, et al. Epidermal growth factor-stimulated extravillous cytotrophoblast motility is mediated by the activation of PI3-K, Akt and both p38 and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Hum Reprod. 2008August;23(8):1733-1741 Epub 2008 May 16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Binker MG, Binker-Cosen AA, Richards D, Oliver B, Cosen-Binker LI. EGF promotes invasion by PANC-1 cells through Rac1/ROS-dependent secretion and activation of MMP-2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009February6;379(2):445-450 Epub 2008 Dec 29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pollheimer J, Loregger T, Sonderegger S, et al. Activation of the canonical wingless/T-cell factor signaling pathway promotes invasive differentiation of human trophoblast. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(4):1134-1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Polakis P. The many ways of Wnt in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17(1):45-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xie H, Tranguch S, Jia X, et al. Inactivation of nuclear Wnt-β-catenin signaling limits blastocyst competency for implantation. Development 2008February;135(4):717-727 Epub 2008 Jan 16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grisaru-Granovsky S, Maoz M, Barzilay O, Yin YJ, Prus D, Bar-Shavit R. Protease activated receptor-1, PAR1, promotes placenta trophoblast invasion and β-catenin stabilization. J Cell Physiol. 2008;218(3):512-521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Even-Ram SC, Grisaru-Granovsky S, Pruss D, et al. The pattern of expression of protease-activated receptors (PARs) during early trophoblast development. J Pathol. 2003;200(1):47-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Salah Z, Haupt S, Maoz M, et al. p53 controls hPar1 function and expression. Oncogene 2008November;27(54):6866-6874 Epub 2008 Sep 29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Goerge T, Barg A, Schnaeker EM, et al. Tumor-derived matrix metalloproteinase-1 targets endothelial proteinase-activated receptor 1 promoting endothelial cell activation. Cancer Res. 2006;66(15):7766-7774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fitzgerald JS, Poehlmann TG, Schleussner E, Markert UR. Trophoblast invasion: the role of intracellular cytokine signalling via signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Hum Reprod Update 2008Jul–Aug;14(4):335-344 Epub 2008 Apr 17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zybina TG, Frank HG, Biesterfeld S, Kaufmann P. Genome multiplication of extravillous trophoblast cells in human placenta in the course of differentiation and invasion into endometrium and myometrium: II, Mechanisms of polyploidization. Tsitologiia 2004;46(7):640-648 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.MacAuley A, Cross JC, Werb Z. Reprogramming the cell cycle for endoreduplication in rodent trophoblast cells. Mol Biol Cell 1998;9(4):795-807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lanzi C, Cassinelli G, Cuccuru G, et al. Cell cycle checkpoint efficiency and cellular response to paclitaxel in prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2001;48(4):254-264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Puig PE, Guilly MN, Bouchot A, et al. Tumor cells can escape DNA-damaging cisplatin through DNA endoreduplication and reversible polyploidy. Cell Biol Int. 2008September;32(9):1031-1043 Epub 2008 May 2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhou Y, Fisher SJ, Janatpour M, et al. Human cytotrophoblasts adopt a vascular phenotype as they differentiate: a strategy for successful endovascular invasion? J Clin Invest 1997;99(9):2139-2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Robertson GP. Mig-7 linked to vasculogenic mimicry. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(5):1454-1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maquoi E, van den Brûle FA, Castronovo V, Foidart JM. Changes in the distribution pattern of galectin-1 and galectin-3 in human placenta correlates with the differentiation pathways of trophoblasts. Placenta 1997;18(5-6):433-439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mourad-Zeidan AA, Melnikova VO, Wang H, Raz A, Bar-Eli M. Expression profiling of Galectin-3-depleted melanoma cells reveals its major role in melanoma cell plasticity and vasculogenic mimicry. Am J Pathol. 2008December;173(6):1839-1852 Epub 2008 Nov 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Iurisci I, Cumashi A, Sherman AA, et al. Consorzio Interuniversitario Nazionale Per la Bio-Oncologia (Cinbo), Italy Synthetic inhibitors of galectin-1 and -3 selectively modulate homotypic cell aggregation and tumor cell apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(1):403-410 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Phillips TM, Lindsey JS. Carcinoma cell-specific Mig-7: a new potential marker for circulating and migrating cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2005;13(1):37-44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Petty AP, Garman KL, Winn VD, Spidel CM, Lindsey JS. Overexpression of carcinoma and embryonic cytotrophoblast cell-specific Mig-7 induces invasion and vessel-like structure formation. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(5):1763-1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.van der Schaft DW, Seftor RE, Seftor EA, et al. Effects of angiogenesis inhibitors on vascular network formation by human endothelial and melanoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(19):1473-1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Condeelis J, Singer RH, Segall JE. The great escape: when cancer cells hijack the genes for chemotaxis and motility [published online ahead of print July 5, 2005] Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005November;21:695-718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schiessl B, Innes BA, Bulmer JN, et al. Localization of angiogenic growth factors and their receptors in the human placental bed throughout normal human pregnancy. Placenta 2009January;30(1):79-87 Epub 2008 Nov 17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cao Y, Liu Q. Therapeutic targets of multiple angiogenic factors for the treatment of cancer and metastasis. Adv Cancer Res. 2007;97:203-224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jain RK, Duda DG, Clark JW, Loeffler JS. Lessons from phase III clinical trials on anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3(1s):24-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shojaei F, Ferrara N. Role of the microenvironment in tumor growth and in refractoriness/resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies. Drug Resist Updat 2008December;11(6):219-230 Epub 2008 Oct 23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fischer C, Jonckx B, Mazzone M, et al. Anti-PlGF inhibits growth of VEGF(R)-inhibitor-resistant tumors without affecting healthy vessels. Cell 2007;131(3):463-475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Loges S, Roncal C, Carmeliet P. Development of targeted angiogenic medicine. J Thromb Haemost. 2009January;7(1):21-33 Epub. 2008 Oct 25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shore VH, Wang TH, Wang CL, Torry RJ, Caudle MR, Torry DS. Vascular endothelial growth factor, placenta growth factor and their receptors in isolated human trophoblast. Placenta 1997;18(8):657-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Willett CG, Boucher Y, Duda DG, et al. Surrogate markers for antiangiogenic therapy and dose-limiting toxicities for bevacizumab with radiation and chemotherapy: continued experience of a phase I trial in rectal cancer patients [letter]. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):8136-8139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell 2007;12(1):9-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wen HY, Abbasi S, Kellems RE, Xia Y. mTOR: a placental growth signaling sensor. Placenta 2005;26(suppl A):S63-S69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Roos S, Jansson N, Palmberg I, Säljö K, Powell TL, Jansson T. Mammalian target of rapamycin in the human placenta regulates leucine transport and is down-regulated in restricted fetal growth. J Physiol. 2007July1;582(pt 1):449-459 Epub 2007 Apr 26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Abraham RT, Eng CH. Mammalian target of rapamycin as a therapeutic target in oncology. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2008;12(2):209-222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lane HA, Wood JM, McSheehy PM, et al. mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) has antiangiogenic/vascular properties distinct from a VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(5):1612-1622 Epub 2009 Feb 17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mor G. Pregnancy reconceived: what keeps a mother's immune system from treating her baby as foreign tissue? A new theory resolves the paradox. Natural History May1, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Moffett-King A. Natural killer cells and pregnancy [published correction appears in Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(12):975] Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(9):656-663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chiou SH, Sheu BC, Chang WC, Huang SC, Hong-Nerng H. Current concepts of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in human malignancies. J Reprod Immunol. 2005October;67(1-2):35-50 Epub 2005 Aug 18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Carlino C, Stabile H, Morrone S, et al. Recruitment of circulating NK cells through decidual tissues: a possible mechanism controlling NK cell accumulation in the uterus during early pregnancy. Blood 2008March15;111(6):3108-3115 Epub 2008 Jan 10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Verma S, Hiby SE, Loke YW, King A. Human decidual natural killer cells express the receptor for and respond to the cytokine interleukin 15. Biol Reprod. 2000;62(4):959-968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Keskin DB, Allan DS, Rybalov B, et al. TGFβ promotes conversion of CD16+ peripheral blood NK cells into CD16- NK cells with similarities to decidual NK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007February;104(9):3378-3383 Epub 2007 Feb 20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Koopman LA, Kopcow HD, Rybalov B, et al. Human decidual natural killer cells are a unique NK cell subset with immunomodulatory potential. J Exp Med. 2003;198(8):1201-1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, Hamani Y, et al. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat Med. 2006September;12(9):1065-1074 Epub 2006 Aug 6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Saito S, Nakashima A, Myojo-Higuma S, Shiozaki A. The balance between cytotoxic NK cells and regulatory NK cells in human pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2008January;77(1):14-22 Epub 2007 Jun 11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wald O, Weiss ID, Wald H, et al. IFN-γ acts on T cells to induce NK cell mobilization and accumulation in target organs. J Immunol. 2006;176(8):4716-4729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wittnebel S, Da Rocha S, Giron-Michel J, et al. Membrane-bound interleukin (IL)-15 on renal tumor cells rescues natural killer cells from IL-2 starvation-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2007;67(12):5594-5599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Carrega P, Morandi B, Costa R, et al. Natural killer cells infiltrating human nonsmall-cell lung cancer are enriched in CD56 bright CD16(-) cells and display an impaired capability to kill tumor cells. Cancer 2008;112(4):863-875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Abumaree MH, Stone PR, Chamley LW. The effects of apoptotic, deported human placental trophoblast on macrophages: possible consequences for pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2006;72(1-2):33-45 Epub 2006 Jul 14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Gustafsson C, Mjösberg J, Matussek A, et al. Gene expression profiling of human decidual macrophages: evidence for immunosuppressive phenotype. PLoS One 2008;3(4):e2078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hagemann T, Biswas SK, Lawrence T, Sica A, Lewis CE. Regulation of macrophage function in tumors: the multifaceted role of NF-κB. Blood 2009April2;113(14):3139-3146 Epub 2009 Jan 26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hagemann T, Lawrence T, McNeish I, et al. “Re-educating” tumor-associated macrophages by targeting NF-κB. J Exp Med. 2008June;205(6):1261-1268 Epub May 19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Heikkinen J, Möttönen M, Alanen A, Lassila O. Phenotypic characterization of regulatory T cells in the human decidua. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136(2):373-378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Somerset DA, Zheng Y, Kilby MD, Sansom DM, Drayson MT. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the immune suppressive CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T-cell subset. Immunology 2004;112(1):38-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]