Abstract

Gynecomastia, defined as benign proliferation of male breast glandular tissue, is usually caused by increased estrogen activity, decreased testosterone activity, or the use of numerous medications. Although a fairly common presentation in the primary care setting and mostly of benign etiology, it can cause patients considerable anxiety. The initial step is to rule out pseudogynecomastia by careful history taking and physical examination. A stepwise approach that includes imaging and laboratory testing to exclude neoplasms and endocrinopathies may facilitate cost-effective diagnosis. If results of all studies are normal, idiopathic gynecomastia is diagnosed. The evidence in this area is mainly of observational nature and lower quality.

Gynecomastia is defined as benign proliferation of male breast glandular tissue.1 Asymptomatic gynecomastia is very common and has a trimodal age distribution, occurring in neonatal, pubertal, and elderly males. The prevalence of asymptomatic gynecomastia is 60% to 90% in neonates, 50% to 60% in adolescents, and up to 70% in men aged 50 to 69 years.2-5 Prevalence of symptomatic gynecomastia is markedly lower. A screening for gynecomastia in 214 hospitalized adult men aged 27 to 92 years revealed that 65% had gynecomastia, defined in this study as nodule size greater than 2 cm; however, none of them were symptomatic.3 Variation in reported prevalence across studies is attributed to variations in the size of the palpable breast tissue used to define gynecomastia and to population characteristics such as age and setting of treatment (primary care vs referral clinics). The evaluation and management perspectives presented in this article do not pertain to physiologic neonatal and adolescent cases but rather to symptomatic adults who are concerned and seek evaluation and treatment.

Although breast cancer is rare in men, those with gynecomastia often become anxious and seek medical attention, making this presentation fairly common in primary care settings. Diagnostic evaluation of these cases can be costly and involves laboratory and radiographic testing; therefore, a diagnostic algorithm that facilitates step-by-step evaluation may be cost-effective and reduce the associated patient anxiety. This article describes the pathophysiology and common mechanisms and causes of benign gynecomastia and introduces a diagnostic algorithm to facilitate evaluation and management of symptomatic cases that present in primary care settings.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The imbalance between estrogen action relative to androgen action at the breast tissue level appears to be the main etiology of gynecomastia.6 Elevated serum estrogen levels may be a result of estrogen-secreting neoplasms or their precursors (eg, Leydig or Sertoli cell tumors, human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG]—producing tumors, and adrenocortical tumors) but more commonly are caused by increased extragonadal conversion of androgens to estrogens by tissue aromatase (as occurs in obesity). Levels of free serum testosterone are decreased in patients with gonadal failure, which can be primary (Klinefelter syndrome, mumps orchitis, castration) or secondary (hypothalamic and pituitary disease). Androgen resistance syndromes due to impaired activity of enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of testosterone can also be associated with gynecomastia.7

The balance between free testosterone and estrogen is also affected by serum levels of sex hormone—binding globulin, which is the proposed mechanism of gynecomastia in certain conditions, such as hyperthyroidism, chronic liver disease, and the use of some medications such as spironolactone.1 Receptors of androgens can also have genetic defects or become blocked by certain medications (eg, bicalutamide, used in the treatment of prostate cancer), and the receptors of estrogens can be activated by certain medications or environmental exposures.1 Of note, patients with pubertal gynecomastia have normal levels of serum estradiol, testosterone, and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate and a normal estrogen-testosterone ratio. However, free testosterone levels in these patients are lower than those of controls without gynecomastia.8

Eventually, the exposure to the hormonal imbalance leads to proliferation of glandular tissues, ie, ductal hyperplasia.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIAGNOSIS

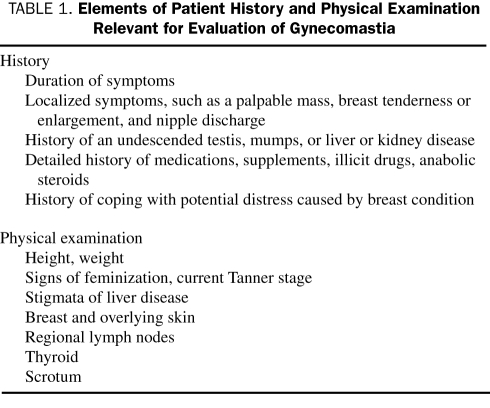

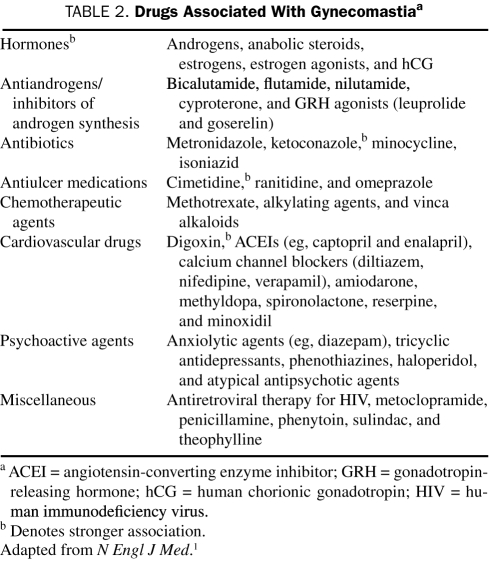

Careful history taking and physical examination (the relevant elements of which are presented in Table 1) often reveal that patients actually are presenting with pseudogynecomastia, which means accumulation of subareolar fat without real proliferation of glandular tissue. Examination of these patients reveals diffuse breast enlargement without a subareolar palpable nodule. These patients do not need additional work-up and only require reassurance. Gynecomastia is usually bilateral,3,9 but patients may present with asymmetrical or unilateral findings. Palpation usually demonstrates a palpable, tender, firm, mobile, disclike mound of tissues1,4 that is not as hard as breast cancer and is located centrally under the nipple-areolar complex. When palpable masses are unilateral, hard, fixed, peripheral to the nipple, and associated with nipple discharge, skin changes, or lymphadenopathy, breast cancer should be suspected and thorough evaluation is recommended. Anthropometric measurements (eg, body mass index) may also be helpful because obesity can be associated with increased peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogens and is associated with a higher prevalence of gynecomastia.3,10 The presence of varicoceles has also been strongly associated with gynecomastia.9 A family history of gynecomastia has been elicited in 58% of patients with persistent pubertal gynecomastia. History may also reveal a clear and temporal association with a causative drug and obviate the need for extensive and costly evaluation. If the association with a drug is unclear, then evaluation is recommended. Table 2 depicts the numerous medications that have been associated with gynecomastia. It has also been associated with the use of alcohol and illicit drugs, such as marijuana, heroin, methadone, and amphetamines.4 Several herbal supplements, particularly those containing phytoestrogen, may also cause gynecomastia.12

TABLE 1.

Elements of Patient History and Physical Examination Relevant for Evaluation of Gynecomastia

TABLE 2.

Drugs Associated With Gynecomastiaa

In one case series, history and physical examination detected a predisposing medical condition or causative medication in 83% of cases of gynecomastia.13 All breast cancer cases in that series presented with a dominant mass on clinical examination or other signs suggestive of malignancy.

Diagnostic Approach

After initial history and examination exclude pseudogynecomastia and other obvious explanatory conditions, mammography can differentiate true gynecomastia from a mass that requires tissue sampling to exclude malignancy. Mammography was found to be fairly accurate in distinguishing between malignant and benign male breast diseases and can substantially reduce the need for biopsies. The sensitivity and specificity of mammography for benign and malignant breast conditions exceed 90%; however, the positive predictive value for malignant conditions is low (55%) because of the low prevalence of malignancy in patients presenting with gynecomastia.14 Imaging of the scrotum is only recommended if palpable masses are present.

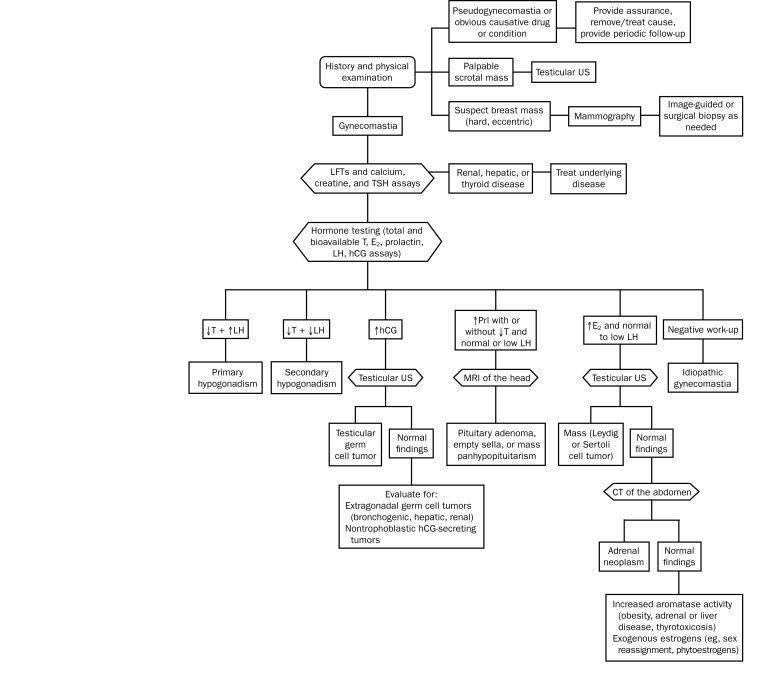

Laboratory investigations are pursued in cases of true gynecomastia without clear explanation. Liver, kidney, and thyroid function tests exclude the respective medical conditions. Hormonal testing measures levels of total and bioavailable testosterone, estradiol, prolactin, luteinizing hormone, and hCG, and its findings can direct toward pituitary, gonadal, and extragonadal endocrinopathies and neoplasms as seen in the stepwise algorithm depicted in the Figure. If all testing is unrevealing, idiopathic gynecomastia is diagnosed.

FIGURE.

Diagnostic algorithm for gynecomastia. CT = computed tomography; E2 = estradiol; hCG = human chorionic gonadotropin; LFT = liver function test; LH = luteinizing hormone; Prl = prolactin; T = testosterone; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone; US = ultrasonography. Adapted from N Engl J Med.11

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a palpable breast mass in a male patient includes pseudogynecomastia, gynecomastia, breast cancer, and numerous other benign conditions. A review of all mammographic findings for men for a period of 5 years at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, FL, revealed a 1% rate of malignancy. Most cases were due to benign causes; of these, gynecomastia represented 62%, with other causes including lipomas, dermoid cysts, sebaceous cysts, lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, ductal ectasia, hematomas, and fat necrosis.13 In contrast, the differential diagnosis of gynecomastia per se, as demonstrated in a series of young adult patients with gynecomastia aged 19 through 29 years, includes idiopathic gynecomastia (58%), hypogonadism (25%), hyperprolactinemia (9%), chronic liver disease (4%), and drug-induced gynecomastia (4%).10 The frequency distribution of these etiologies is imprecise because of the small number of cases reported in the literature and may vary widely across publications and practice settings.

MANAGEMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Overall, gynecomastia is a benign condition and is usually self-limited. Over time, fibrotic tissue replaces symptomatic proliferation of glandular tissue and tenderness resolves. If the appropriate work-up does not reveal considerable underlying pathology, reassurance and periodic follow-up are recommended. Although evidence is lacking to support a recommendation for follow-up intervals, 6 months seems reasonable. Causative medications should be withdrawn or the underlying causative medical conditions (eg, hyperthyroidism) should be addressed. Most cases of pubertal gynecomastia usually resolve in less than a year.8 If gynecomastia persists and is associated with pain or psychological distress and if the patient wishes to pursue treatment, pharmacological and surgical options are available. Pharmacotherapy is likely beneficial if implemented early before fibrous tissue replaces glandular tissue, whereas surgery can be performed at any time.

Pharmacotherapy

Several pharmacological agents have been used to manipulate the hormonal imbalances thought to cause gynecomastia. However, the studies that evaluated their efficacy were in general small and uncontrolled, making inference challenging.

Estrogen receptor modifiers appear to be fairly safe and beneficial. Alagaratnam15 treated 61 Chinese men with tamoxifen for a median of 2 months with 36 months of follow-up, demonstrating an 84% rate of complete regression of breast swelling. Lawrence et al16 used a 3- to 9-month course of estrogen receptor modifiers (tamoxifen or raloxifene) to treat 38 consecutive patients with persistent pubertal gynecomastia and demonstrated a mean reduction in breast nodule diameter of 2.1 cm with no serious adverse effects. Similar results were reported in another case series of 37 patients who used tamoxifen; reductions in pain and nodule size were seen in all patients without long-term adverse effects.17

Dihydrotestosterone, danazol, clomiphene, and aromatase inhibitors such as testolactone and anastrozole may also have benefit but are less commonly studied and used.4 Overall, the use of all these drugs is supported by a very low quality of evidence, and the uncertainty about the balance of their benefits and harms should be highlighted to candidate patients.

Surgical Correction

Surgery is the criterion standard treatment for gynecomastia. The most commonly used technique is subcutaneous mastectomy that involves the direct resection of the glandular tissue using a periareolar or transareolar approach with or without associated liposuction. Liposuction alone may be sufficient if breast enlargement is purely due to excess fatty tissue without substantial glandular hypertrophy.18 Skin resection is needed for more advanced cases.

In general, surgical treatment produces good cosmesis and is well tolerated. Newer, less invasive techniques that require minimal surgical incision have recently emerged and may offer faster recovery and lower rates of local complications.18-20 Histologic analysis is recommended in true gynecomastia corrections because unexpected histologic findings such as spindle-cell hemangioendothelioma and papilloma may occur in 3% of cases.21

Patients with gynecomastia have a favorable prognosis. These patients present with 2 main concerns: ruling out breast cancer and cosmetic correction. The first concern is adequately addressed by following the appropriate diagnostic evaluation. Breast cancer is rare in males, representing less than 1% of all cases of breast cancer; only 1% of mammograms in men reveal breast cancer.13 Therefore, the decision to treat and the choice of treatment should be based on the degree to which this condition has affected the quality of life and mental health of patients and on their desire for cosmetic correction. The body of research supporting the diagnostic approach and treatment strategies for gynecomastia consists of expert opinion, case series, and observational studies; hence, the evidence is considered to be of low to very low quality. By acknowledging this low quality of evidence when discussing testing and treatment options with patients, physicians allow room in the process of decision making for consideration of other factors, such as resources, availability of services, and patients' values and preferences.22

CONCLUSION

The evaluation of gynecomastias can be complex. A step-wise approach that starts with careful history taking and physical examination may obviate the need for extensive work-up. Subsequent selective imaging and laboratory testing help exclude possible neoplasms and endocrinopathies. The etiology is usually benign.

Supplementary Material

On completion of this article, you should be able to: (1) recognize the different mechanisms and causative medications and conditions associated with gynecomastia, (2) demonstrate the ability to conduct a stepwise diagnostic approach to evaluate and diagnose most cases of gynecomastia, and (3) identify the available treatments for gynecomastia and assist patients in the process of decision making about treatment.

CME Questions About Gynecomastia

-

Which one of the following statements best describes a typical presentation of gynecomastia?

Unilateral peripheral mass

Painless bilateral hard and fixed masses

A mass associated with nipple discharge

Bilateral painful masses in an anxious adolescent

Bilateral masses with minimal axillary lymphadenopathy

-

Which one of the following statements best describes the recommendations for gynecomastia evaluation?

Diagnostic work-up for gynecomastia is recommended if initial history and findings on examination do not reveal an obvious cause

Any case of gynecomastia requires laboratory tests and imaging to rule out endocrinopathies and malignancies

A disclike mound of tissue just beneath the nipple-areolar complex is a feature of malignancy

Breast pain is a sign of malignancy

Mammography is recommended to rule out pseudogynecomastia

-

Which one of the following statements best describes the interpretation of laboratory results in patients with gynecomastia?

Elevated luteinizing hormone and low testosterone levels suggest secondary hypogonadism

Elevated levels of prolactin are common in gynecomastia and do not require additional evaluation

Elevated levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and normal findings on testicular ultrasonography indicate the need for evaluation for extragonadal hCG-secreting tumors

Elevated estradiol levels with normal findings on testicular ultrasonography do not require additional work-up

If results on all laboratory testing are normal, pseudogynecomastia is diagnosed

-

Which one of the following statements best describes the available pharmacological agents for gynecomastia?

Randomized trials have shown estrogen receptor modifiers to be safe and effective

Tamoxifen is effective but produces serious adverse effects

Tamoxifen treatment reduces the future risk of developing breast cancer

Pharmacotherapy is most effective when instituted early

Tamoxifen reduces breast size but is unlikely to resolve breast pain

-

Which one of the following statements best describes the surgical options available to treat gynecomastia?

Surgical therapy for gynecomastia is the criterion standard for treatment of patients interested in cosmesis

Liposuction is very effective for most cases of gynecomastia

Mastectomy with axillary dissection is the treatment of choice for gynecomastia

The newer endoscopic approach is only appropriate when the breast is enlarged primarily as a result of fat accumulation

Resection of glandular tissue is always recommended because of the increased risk of neoplastic transformation of benign gynecomastia

This activity was designated for 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s).™

Because the Concise Review for Clinicians contributions are now a CME activity, the answers to the questions will no longer be published in the print journal. For CME credit and the answers, see the link on our Web site at mayoclinicproceedings.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1229-1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Georgiadis E, Papandreou L, Evangelopoulou C, et al. Incidence of gynaecomastia in 954 young males and its relationship to somatometric parameters. Ann Hum Biol. 1994;21(6):579-587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niewoehner CB, Nuttal FQ. Gynecomastia in a hospitalized male population. Am J Med. 1984;77(4):633-638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordt CA, DiVasta AD. Gynecomastia in adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20(4):375-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKiernan JF, Hull D. Breast development in the newborn. Arch Dis Child 1981;56(7):525-529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braunstein GD. Aromatase and gynecomastia. Endocr Relat Cancer 1999;6(2):315-324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathur R, Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia: pathomechanisms and treatment strategies. Horm Res. 1997;48(3):95-102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biro FM, Lucky AW, Huster GA, Morrison JA. Hormonal studies and physical maturation in adolescent gynecomastia. J Pediatr. 1990;116(3):450-455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumanov P, Deepinder F, Robeva R, Tomova A, Li J, Agarwal A. Relationship of adolescent gynecomastia with varicocele and somatometric parameters: a cross-sectional study in 6200 healthy boys. J Adolesc Health 2007;41(2):126-131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ersöz H, Onde ME, Terekeci H, Kurtoglu S, Tor H. Causes of gynaecomastia in young adult males and factors associated with idiopathic gynaecomastia. Int J Androl. 2002;25(5):312-316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(7):490-495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braunstein GD. Environmental gynecomastia [editorial]. Endocr Pract. 2008;14(4):409-410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hines SL, Tan WW, Yasrebi M, DePeri ER, Perez EA. The role of mammography in male patients with breast symptoms. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(3):297-300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans GF, Anthony T, Turnage RH, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of mammography in the evaluation of male breast disease [published correction appears in Am J Surg. 2001;181(6):579] Am J Surg. 2001;181:96-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alagaratnam TT. Idiopathic gynecomastia treated with tamoxifen: a preliminary report. Clin Ther. 1987;9(5):483-487 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence SE, Faught KA, Vethamuthu J, Lawson ML. Beneficial effects of raloxifene and tamoxifen in the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia. J Pediatr. 2004;145(1):71-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derman O, Kanbur NO, Kutluk T. Tamoxifen treatment for pubertal gynecomastia. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2003;15(4):359-363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courtiss EH. Gynecomastia: analysis of 159 patients and current recommendations for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79(5):740-753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prado AC, Castillo PF. Minimal surgical access to treat gynecomastia with the use of a power-assisted arthroscopic-endoscopic cartilage shaver. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(3):939-942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu J, Huang J. Surgical management of gynecomastia under endoscope. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Techniq A. 2008;18(3):433-437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Handschin AE, Bietry D, Hüsler R, Banic A, Constantinescu M. Surgical management of gynecomastia—a 10-year analysis. World J Surg. 2008;32(1):38-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swiglo BA, Murad MH, Schünemann HJ, et al. A case for clarity, consistency, and helpfulness: state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines in endocrinology using the grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008March;93(3):666-673 Epub 2008 Jan 2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.