Abstract

Objective To evaluate the effectiveness of 15 minutes of immobilisation versus immediate mobilisation after intrauterine insemination.

Design Randomised controlled trial.

Setting One academic teaching hospital and six non-academic teaching hospitals.

Participants Women having intrauterine insemination for unexplained, cervical factor, or male subfertility.

Interventions 15 minutes of immobilisation or immediate mobilisation after insemination.

Main outcome measure Ongoing pregnancy per couple.

Results 391 couples were randomised; 199 couples were allocated to 15 minutes of immobilisation after intrauterine insemination, and 192 couples were allocated to immediate mobilisation (control). The ongoing pregnancy rate per couple was significantly higher in the immobilisation group than in the control group: 27% (n=54) versus 18% (34); relative risk 1.5, 95% confidence interval 1.1 to 2.2 (crude difference in ongoing pregnancy rates: 9.4%, 1.2% to 17%). Live birth rates were 27% (53) in the immobilisation group and 17% (32) in the control group: relative risk 1.6, 1.1 to 2.4 (crude difference for live birth rates: 10%, 1.8% to 18%). In the immobilisation group, the ongoing pregnancy rates in the first, second, and third treatment cycles were 10%, 10%, and 7%. The corresponding rates in the mobilisation group were 7%, 5%, and 5%.

Conclusion In treatment with intrauterine insemination, 15 minutes’ immobilisation after insemination is an effective modification. Immobilisation for 15 minutes should be offered to all women treated with intrauterine insemination.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN53294431.

Introduction

Intrauterine insemination with or without ovarian hyperstimulation is probably the most frequently applied fertility treatment in the world. One of the questions that has remained unresolved is whether pregnancy rates are positively influenced by immobilisation after insemination.

Several studies have investigated sperm migration and survival in the female genital tract. Spermatozoa may reach the fallopian tube—the site of fertilisation—within two to 10 minutes.1 2 3 4 These data suggest that sperm migration to the site of fertilisation is independent of the position of the woman directly after intrauterine insemination.

In 2000, however, Saleh et al reported that if a woman remained in a supine position for 10 minutes after intrauterine insemination, the pregnancy rates increased significantly compared with immediate mobilisation (13% v 4% per cycle).5 Unfortunately, this randomised controlled trial was rather small and unbalanced, as 40 couples were compared with 55 couples. Also, the outcome of pregnancy was not defined. As the subject has not been studied since then, we assessed the effectiveness of immobilisation after intrauterine insemination in a large multicentre randomised clinical trial.

Methods

Subfertile women between 18 and 43 years of age with an indication for treatment with intrauterine insemination were eligible for the trial. Couples using donor semen (fresh or cryopreserved) could also be included in the trial. We made no restrictions with regard to the use and type of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation during treatment cycles.

All couples had been investigated for infertility according to the guidelines of the Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.6 This included a medical history, cycle monitoring, semen analysis, postcoital test, and assessment of tubal patency. The woman’s age, duration of subfertility, and whether subfertility was primary or secondary were documented. We defined duration of subfertility as the time from when the couple started actively trying to conceive to the time of start of treatment. If the couple had a previous pregnancy that had not resulted in a live birth, we defined duration of subfertility as the time from the first day of the pregnancy to the time of start of treatment. We defined primary subfertility as the absence of pregnancy in the current relationship.

If cryopreserved donor sperm was used, we defined subfertility as at least 12 cycles of unsuccessful intracervical insemination before intrauterine insemination. Ovulation was confirmed by basal body temperature curve, midluteal serum progesterone, or sonographic monitoring of the cycle. We included anovulatory women in the trial only after ovulation had been induced for at least six to 12 months without conception or if a male factor was also present, as in these instances an indication for intrauterine insemination existed.

At least one well timed postcoital test was done (except in couples using cryopreserved donor sperm) during the basic assessment of fertility. The test was planned according to the basal body temperature curve or findings of ultrasonography. A cervical factor was diagnosed if no progressive spermatozoa were seen in five high power fields at 400 times magnification and the total motile sperm count was less than 10×106 spermatozoa/ml. Tubal pathology was assessed by a chlamydia antibody test, a hysterosalpingogram, or laparoscopy. In the case of a positive chlamydia antibody test, the tubal status was subsequently evaluated with a hysterosalpingogram or laparoscopy; in women with a negative chlamydia antibody test, tubal pathology was considered to be absent. Patients had to have at least one patent tube to be eligible for the study. We defined male subfertility as total motile sperm count less than 10×106 spermatozoa/ml and unexplained subfertility as total motile sperm count more than 10×106 spermatozoa/ml and exclusion of a cervical factor.

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation, semen preparation, and insemination regimens were done according to hospital specific protocols. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation was done with clomiphene citrate 50-150 mg on days five to nine of the cycle or subcutaneous injections of recombinant or urinary follicle stimulating hormone daily (Gonal F, Serono Benelux, The Hague, Netherlands; Puregon, Organon, Oss, Netherlands; or Menopur, Ferring, Hoofddorp, Netherlands). Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation was primarily done with recombinant follicle stimulating hormone in all clinics but one, where clomiphene citrate was used as a first line treatment. Ovulation was induced with 5000 IU or 10 000 IU of human chorionic gonadotrophin (Pregnyl, Organon), and women were inseminated 36-40 hours later. If more than three dominant follicles (>16 mm) were present, the treatment cycle was cancelled. Semen samples were processed within one hour of ejaculation by density gradient centrifugation followed by washing with culture medium. The volume of semen that was inseminated varied between 0.2 ml and 1.0 ml.

Patients were asked to participate before start of the first intrauterine insemination cycle. After giving written informed consent, the couples were randomly assigned to have three cycles of intrauterine insemination followed by 15 minutes of immobilisation (intervention group) or three cycles of intrauterine insemination with immediate mobilisation (control group). We randomised the couples before the first insemination, by using a web based computer program with a stratification procedure for age (18-34 years and 35-43 years) and centre. Women were inseminated in the lithotomy position in a Trendelenburg tilt. Depending on their allocation, women remained in the supine position for 15 minutes (timed by an alarm clock) or were mobilised immediately.

The primary outcome measure was the occurrence of an ongoing, viable intrauterine pregnancy (within four months after randomisation), defined as fetal heart beat seen by transvaginal ultrasonography at 12 weeks’ gestation. Secondary outcomes included live birth, biochemical pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and miscarriage. Pregnancy was determined by a qualitative urine test for β human chorionic gonadotrophin if no menstruation occurred 14 days after insemination.

Assuming an ongoing pregnancy rate of 10% per cycle in the mobilisation group, we believed that an increase in the ongoing pregnancy rate from 10% to 14% per cycle would be relevant. This corresponds to a 12% difference after three cycles. As expecting that 15 minutes of immobilisation would perform worse than immediate mobilisation would not be logical, we used one sided statistical tests. Using an α error of 0.05 and a β error of 0.20, and assuming a dropout rate of 10%, we needed 185 couples in each arm.

We calculated the rates of ongoing pregnancy per couple in each group and the corresponding relative risk with 95% confidence intervals. We used a two tailed Fisher’s exact test to test for significance. We did stratified analyses for different subgroups and used Kaplan-Meier analysis to calculate time to pregnancy. We initially analysed data according to the intention to treat principle and followed this with a per protocol analysis.

Results

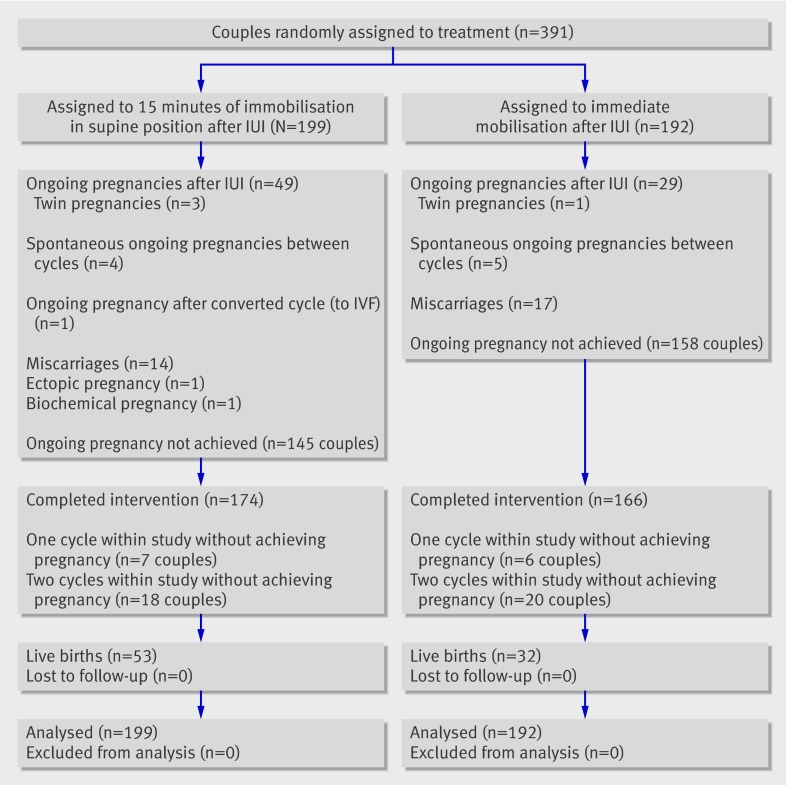

Between September 2005 and October 2007, we randomly assigned 391 couples to immobilisation in a supine position for 15 minutes (199 couples; intervention group) or immediate mobilisation (192 couples; control group). Figure 1 shows the trial profile. The baseline characteristics were comparable in the two groups; very small differences existed only in distribution of diagnoses and use of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (table).

Fig 1 Trial profile. Couples who completed the intervention were those who had three cycles of intrauterine insemination (IUI) within four months or achieved pregnancy. IVF=in vitro fertilisation

Baseline characteristics. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | 15 minutes of immobilisation (n=199) | Immediate mobilisation (n=192) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) woman’s age (years) | 33.9 (3.8) | 33.3 (3.9) |

| Mean (SD) duration of subfertility (years) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.7 (2.5) |

| Primary subfertility | 145 (73) | 148 (77) |

| Cause of subfertility: | ||

| Cervical factor | 45 (23) | 47 (24) |

| Male factor* | 20 (10) | 22 (11) |

| Unexplained | 101 (51) | 86 (45) |

| Anovulation | 5 (3) | 8 (4) |

| One sided tubal pathology | 11 (5) | 11 (6) |

| More than one diagnosis | 17 (9) | 18 (9) |

| Use of donor semen | 2 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Use of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation: | 118 (59) | 124 (65) |

| Clomiphene citrate | 26 (13) | 25 (13) |

| Recombinant FSH | 91 (46) | 99 (52) |

| GnRH | 1 (<1) | 0 |

FSH=follicle stimulation hormone; GnRH=gonadotrophin releasing hormone.

*Total motile sperm count less than 10×106/ml.

The ongoing pregnancy rate per couple was significantly higher in the immobilisation group than in the control group: 27% (54/199) versus 18% (34/192); relative risk 1.5, 95% confidence interval 1.1 to 2.2; P=0.03. The crude difference in ongoing pregnancy rates was 9.4% (95% confidence interval 1.2% to 17%). Live birth rates were 27% (53/199) in the immobilisation group and 17% (32/192) in the mobilisation group (relative risk 1.6, 1.1 to 2.4; P=0.02). The crude difference in live birth rates was 10% (1.8% to 18%).

During the study, nine spontaneous pregnancies occurred between treatment cycles: four in the immobilisation group (one after the first cycle, three after the second cycle) and five in the mobilisation group (two after the first cycle, three after the second cycle) (fig 1). One treatment cycle in the immobilisation group was converted to in vitro fertilisation because of ovarian hyper-response, and this cycle resulted in an ongoing pregnancy.

In the per protocol analysis, we excluded these 10 ongoing pregnancies that did not result from intrauterine insemination. Again, the ongoing pregnancy rate in the immobilisation group was significantly higher: 25% (49/199) versus 15% (29/192); relative risk 1.6, 1.1 to 2.5; P=0.01.

One patient was randomised twice in the study: the first time she was allocated to immediate mobilisation. An ongoing pregnancy occurred but was terminated at 20 weeks’ gestation because of multiple congenital abnormalities. The second time, the patient was randomised to immobilisation. Again an ongoing pregnancy occurred; this time it resulted in a live birth.

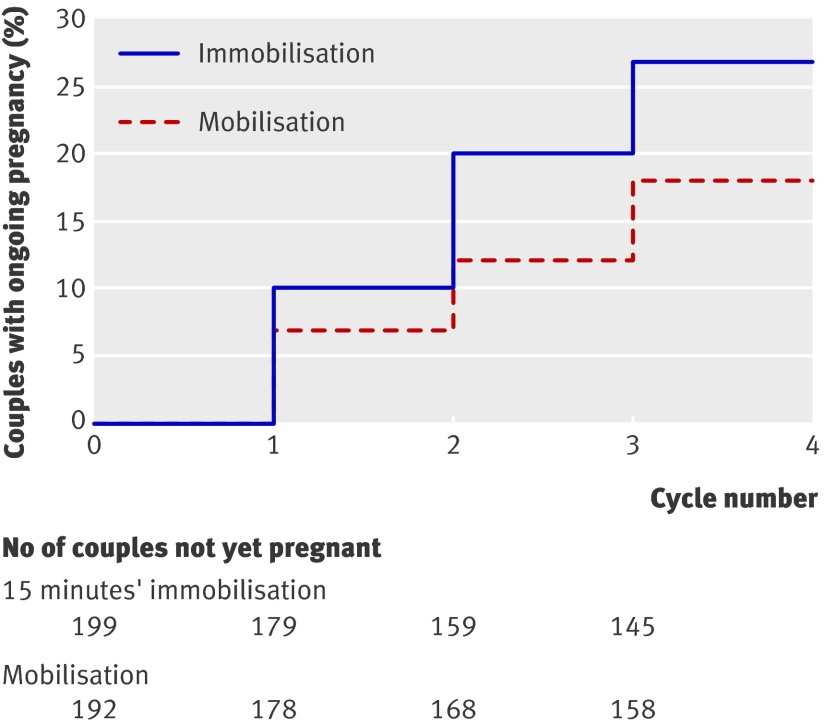

The Kaplan-Meier curve in figure 2 shows time to ongoing pregnancy. We found a significant difference in time to pregnancy in favour of immobilisation (log rank test, P=0.026). The mean number of cycles per couple during the study was 2.4 in the immobilisation group and 2.5 in the control group. In the immobilisation group, ongoing pregnancy rates in the first, second, and third cycles were 10%, 10%, and 7%. The corresponding rates in the immediate mobilisation group were 7%, 5%, and 5%.

Fig 2 Kaplan-Meier curve of time to ongoing pregnancy

In the immobilisation group, 25 (13%) patients did not complete three cycles or achieve pregnancy within the study period compared with 26 (14%) in the mobilisation group (fig 1). Reasons for not completing three cycles were delay by the patient between cycles, burden of the treatment, or doctor’s advice to stop intrauterine insemination treatment.

Discussion

In this large randomised controlled trial, we found that 15 minutes of immobilisation after intrauterine insemination significantly increased ongoing pregnancy rates. Although the difference in ongoing pregnancy rate per couple was somewhat lower than assumed in the power analysis (9.5% observed versus 12% expected), we consider this difference to be clinically relevant, especially as 15 minutes of immobilisation is a simple intervention with low additional costs. Although immobilisation takes more time and occupies more space in busy rooms, the intervention will be economic in the long run, as pregnant patients will not return in subsequent cycles.

The mechanism of the effect of immobilisation after insemination is unclear. After coitus, spermatozoa enter the cervix through the cervical mucus into the uterus, leaving the seminal plasma behind in the vagina. In intrauterine insemination, spermatozoa are inseminated in a small volume of fluid directly into the uterus. As a consequence, immediate mobilisation might cause leakage of this volume together with spermatozoa out of the uterus; alternatively, movement of processed sperm to and up the fallopian tubes may take longer than after intercourse.7

Small differences in treatment protocols among participating centres existed in this multicentre study, such as inseminated volume of semen and type of hyperstimulation. However, randomisation generated an equal distribution of the couples over the two treatment groups. Also, as heterogeneity in treatment protocols is likely among different fertility clinics, our findings represent daily practice and are therefore more generalisable to other populations.

Protocol violation in the control group was unlikely, as the woman was immediately mobilised with the physician in the room. In most centres, this was the standard approach before start of the study. In the immobilisation group, prolongation of the period of immobilisation at the initiative of the patient may have occurred in some cases.

Conclusion

We found a clinically relevant and statistically significant improvement in ongoing pregnancy rates after 15 minutes of immobilisation, confirming the results of a previous study.5 As immobilisation is easily done and carries very little cost, we suggest incorporating immobilisation as a standard procedure in intrauterine insemination treatment.

What is already known on this topic

Intrauterine insemination with or without ovarian hyperstimulation is the most frequently applied fertility treatment in the world

Spermatozoa may reach the fallopian tube—the site of fertilisation—as soon as two minutes after insemination

What this study adds

Fifteen minutes of immobilisation after intrauterine insemination significantly improves ongoing pregnancy rates compared with immediate mobilisation

This work was presented as an oral presentation at the 24th Annual Meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology 2008, in Barcelona, Spain.

Contributors: BWJM and FvdV designed the study. IMC promoted it, coordinated this randomised controlled trial, collected the data, and sought ethical approval. PAF, PM, TC, HJHMVD, MHG, MHM, and CAHJ included couples and collected data. IMC did the analysis, under the supervision of BWJM. All authors helped to prepare the final report. IMC, BWJM, and PvdV are the guarantors.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The institutional review board of the Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, approved study protocol. Local permission was obtained in each of the seven participating hospitals. All participants gave written informed consent.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b4080

References

- 1.Hafez ES. In vivo and in vitro sperm penetration in cervical mucus. Acta Eur Fertil 1979;10(2):41-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Settlage DS, Motoshima M, Tredway DR. Sperm transport from the external cervical os to the fallopian tubes in women: a time and quantitation study. Fertil Steril 1973;24:655-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kissler S, Siebzehnruebl E, Kohl J, Mueller A, Hamscho N, Gaetje R, et al. Uterine contractility and directed sperm transport assessed by hysterosalpingoscintigraphy (HSSG) and intrauterine pressure (IUP) measurement. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2004;83:369-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunz G, Beil D, Deininger H, Wildt L, LeyendeckerG. The dynamics of rapid sperm transport through the female genital tract: evidence from vaginal sonography of uterine peristalsis and hysterosalpingoscintigraphy. Hum Reprod 1996;11:627-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saleh A, Tan SL, Biljan MM, Tulandi T. A randomized study of the effect of 10 minutes of bed rest after intrauterine insemination. Fertil Steril 2000;74:509-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Guideline—basic fertility work-up. NVOG-guideline nr 1, 2004 (available at www.nvog.nl).

- 7.Suarez SS, Pacey AA. Sperm transport in the female reproductive tract. Hum Reprod Update 2006;12:23-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]