Abstract

Head direction (HD) cells discharge as a function of the rat’s directional orientation with respect to its environment. Because animals with posterior parietal cortex (PPC) lesions exhibit spatial and navigational deficits, and the PPC is indirectly connected to areas containing HD cells, we determined the effects of bilateral PPC lesions on HD cells recorded in the anterodorsal thalamus. HD cells from lesioned animals had similar firing properties compared to controls and their preferred firing directions shifted a corresponding amount following rotation of the major visual landmark. Because animals were not exposed to the visual landmark until after surgical recovery, these results provide evidence that the PPC is not necessary for visual landmark control or the establishment of landmark stability. Further, cells from lesioned animals maintained a stable preferred firing direction when they foraged in the dark and were only slightly less stable than controls when they self-locomoted into a novel enclosure. These findings suggest that PPC does not play a major role in the use of landmark and self-movement cues in updating the HD cell signal, or in its generation.

Keywords: path-integration, vestibular, navigation, anterodorsal thalamic nucleus, spatial orientation

The posterior parietal cortex (PPC) is postulated to be involved in the orientation of the body in space and the representation of space around the body (Andersen, Snyder, Bradley, & Xing, 1997; Arbib, 1997; Colby & Goldberg, 1999; Corwin & Reep, 1998; McNaughton, Leonard, & Chen, 1989; Save & Poucet, 2000a). In accordance with findings in primates, rats with PPC lesions exhibit an array of spatial deficits including sensory neglect (King & Corwin, 1993), an inability to notice a change in the spatial relationship between objects in the environment (DeCoteau & Kesner, 1998), and deficits in tasks requiring the integration of visual cues and motor responses (Davis & McDaniel, 1993; DiMattia & Kesner, 1988; Kolb & Walkey, 1987). Electrophysiological studies of rat PPC have supported the view that this area has a role in directing spatial behavior, with cells showing modulation based on the movement state of the animal relative to a spatial task (Chen, Lin, Barnes, & McNaughton, 1994; Chen, Lin, Green, Barnes, & McNaughton, 1994; McNaughton, Mizumori, Barnes, Marquis, & Green, 1994; Nitz, 2006), and modulation based on the location of auditory targets relative to the animal (Nakamura, 1999).

Using the rodent model, investigators have identified three important classes of cells that are believed to be involved in navigation. Place cells, recorded primarily in the hippocampal formation, are preferentially active when the animal is within a specific area in an environment - referred to as the “place field” of the recorded cell (O’Keefe & Dostrovsky, 1971). Grid cells, found primarily in the dorsal caudal medial entorhinal cortex, discharge at multiple locations in an environment and these locations form a regular, repeating grid-like pattern (Hafting, Fyhn, Molden, Moser, & Moser, 2005). Head direction (HD) cells, found throughout the classic Papez circuit, become active when the animal orients its head in the “preferred direction” of the recorded cell, independent of its location and ongoing behavior (Taube, 1995; Taube, Muller, & Ranck, 1990a). All three cell types respond to visual landmark and self-movement (idiothetic) information, signals that are considered important for animal navigation (Gallistel, 1990; Muller & Kubie, 1987; Quirk, Muller, & Kubie, 1990; Taube & Burton, 1995; Taube, Muller, & Ranck, 1990b).

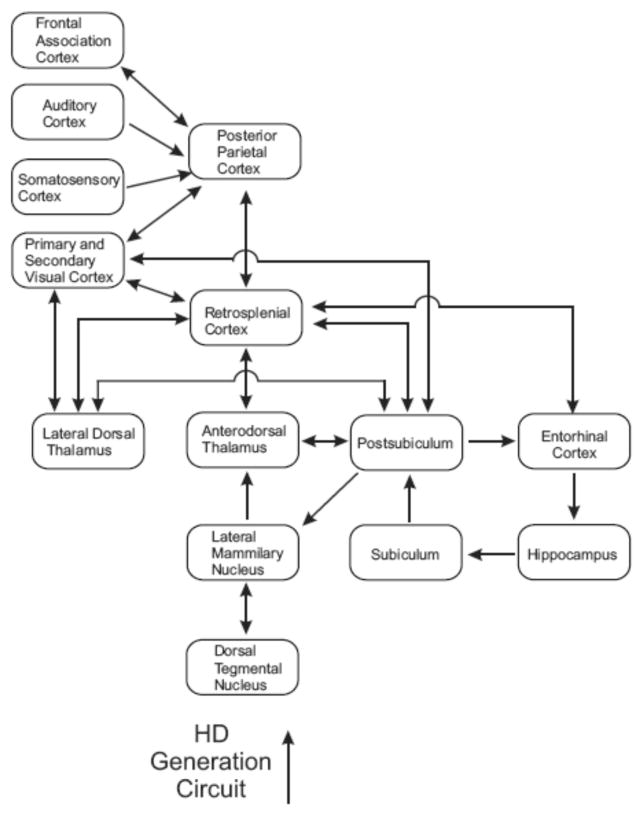

Connectivity studies have led many to suggest that PPC is ideally suited to provide convergence of motor and sensory information to navigational circuitry (Corwin & Reep, 1998; Save & Poucet, 2000a). Figure 1 presents a schematic diagram showing the major connections by which information could flow from PPC to limbic regions presumably involved in navigation and, in particular, the HD cell circuitry. Rat PPC shares connections with primary and secondary visual cortex (Kolb & Walkey, 1987; Miller & Vogt, 1984; Reep, Chandler, King, & Corwin, 1994), auditory cortex (Reep et al., 1994), somatosensory cortex (Kolb & Walkey, 1987; Reep et al., 1994) and prefrontal areas known to contain motor signals (Kolb & Walkey, 1987; Reep et al., 1994). PPC also shares reciprocal connections with retrosplenial cortex (Kolb & Walkey, 1987; Reep et al., 1994), which in turn projects to a number of limbic structures involved in navigation such as the entorhinal cortex (Wyss & Van Groen, 1992), postsubiculum (Vogt & Miller, 1983), and anterodorsal thalamus (ADN; Sripandkulchai & Wyss, 1986). Entorhinal cortex is the primary cortical input region of the hippocampal complex, and HD cells can be found in the retrosplenial cortex, anterodorsal thalamus, and post-subiculum (reviewed in Taube, 2007). In short, the pathways exist for PPC to serve as a multimodal association area by which cortically generated signals utilized during navigation reach limbic circuitry.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of connections between PPC, other cortical areas, and subcortical areas related to the HD circuit. Arrows represent direction of information flow between connected areas.

Given the close anatomical connections between PPC and navigational structures and electrophysiological findings that PPC cells are modulated by visual, idiothetic, and even HD information (Chen et al., 1994a, b; McNaughton et al., 1994), it is not surprising that investigators have proposed a major role for PPC in the networks mediating navigational behavior. Conceptualizations of navigational circuitry have assigned PPC the role of processing visual landmark information and the integration of self-movement and visuospatial cues (Arbib, 1997; McNaughton et al., 1996; Save & Poucet, 2000a; Taube, 1998). To test this hypothesis, we produced lesions of PPC using two commonly used coordinates for PPC. We then monitored HD cell activity in the ADN during three tasks, one assessing visual landmark control and the other two assessing idiothetic control. To determine whether the PPC contributed to the acquisition or selection of visual cues as landmarks, animals were not exposed to the testing environment and its salient visual cues until after the lesions were conducted. We found that PPC lesions did not disrupt generation of direction-specific firing in ADN HD cells or landmark control of HD cell preferred firing directions. In addition, PPC lesions led only to mild impairments in idiothetic control of HD cell activity.

Method

Subjects

There were 28 female Long-Evans rats that served as subjects. Weights ranged between 220 and 300 g at the start of the study. The animals were singly housed in clear plastic cages in a room maintained on a 12-hr light/12-hr dark cycle. A food-restricted diet was used to maintain the rats at approximately 85% of free feeding weight. Water was freely available in the home cage.

Surgical Procedures

Each animal received implantation of a recording electrode array to monitor neural activity during the behavioral task. Electrodes were constructed using methods described by Kubie (1984), and consisted of a bundle of 10 25 μm diameter nichrome wires that were insulated except at the tip. The wires were threaded through a stainless steel cannula that was moveable in the dorsal/ventral direction after being fixed to the skull using dental acrylic. Standard surgical procedures were followed for implantation of the recording electrodes (Taube, 1995). Briefly, animals were anesthetized with a ketamine-acepromazine-xylazine cocktail. After exposure of the skull, a hole was drilled and the electrode implanted just dorsal to the right ADN based on coordinates (1.5 mm posterior to bregma, 1.3 mm lateral to bregma and 3.7 mm below the cortical surface) provided by Paxinos and Watson (1998).

During this same surgery some animals (n = 15) received bilateral aspiration lesions of PPC. The rat parietal cortex is generally divided into three distinct areas—anterior, ventral, and posterior, and the posterior area can be further subdivided into three zones designated as dorsal, rostral, and caudal (Palomero-Gallagher & Zilles, 2004). Because definitive functions have not been ascribed to each of the three zones in PPC, we designed our experiments to lesion the entire PPC. For these animals, the skull was opened over the lesion sites, the dura-mater was cut, and a glass pipette attached to a suction source was used to aspirate brain tissue. Because there is disagreement in the literature as to the location of PPC, we utilized two different sized lesions. The primary disagreement has concerned the anterior-posterior (AP) placement of the area, with a few investigators delineating the area as a 4mm long strip beginning 0.5 mm anterior to bregma (DiMattia & Kesner, 1988), while others consider the boundaries as 2.0 to 6.0 mm posterior to Bregma (Save, Paz-Villagran, Alexinsky, & Poucet, 2005). Still other studies have placed the PPC somewhere in-between these two areas (Goodrich-Hunsaker, Hunsaker, & Kessner, 2005; Kolb & Walkey, 1987; Ward & Brown, 1997). Accordingly, animals within group PPC-Large (n = 5) were given large bilateral lesions intended to overlie all these areas utilized previously (AP: + 0.5 to −6.0 relative to Bregma, and medial-lateral (ML): ± 1.5 to 5.5 relative to midline). Group PPC-Small (n = 10) received smaller lesions intended to overlie the more posterior lesion coordinates that are commonly used (AP: −2.0 to −6.0 relative to bregma and ML: ± 1.5 to 5.5 relative to midline). For both lesion sizes, tissue was aspirated to a depth of approximately 1 mm. After aspirations, lesion sites were packed with sterile gel foam and the previously overlying skull pieces were cemented back in place using orthopedic cement. Animals were allowed at least 1 week of recovery before behavioral training. All procedures were conducted under an institutionally approved animal care and use protocol.

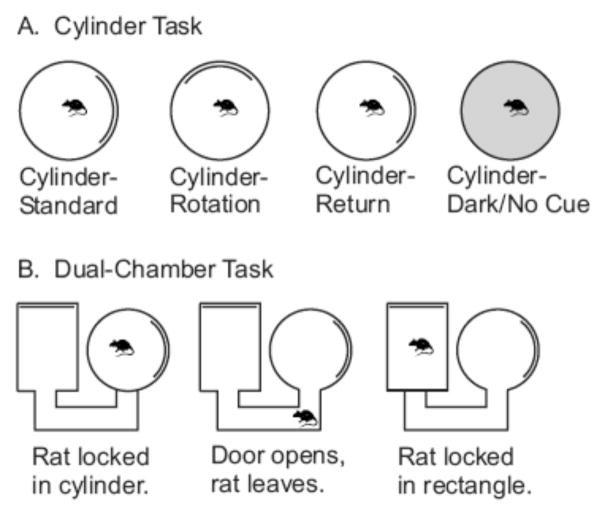

Apparatus

Two different enclosures were utilized during recordings. Both structures were painted gray and had floors of paper that were changed between sessions. A wooden cylinder (76 cm diameter, 51 cm high) was used when searching for cells and to assess landmark control of HD activity (Figure 2A). The wall of the cylinder was featureless except for a white card attached to the inside wall, which encompassed approximately 100° of arc, centered at the 0° position. A dual-chamber apparatus similar to that first used by Taube and Burton (1995) was used to assess idiothetic control of HD activity (Figure 2B). This enclosure included a cylinder similar to that described above with the exception of a section of wall that could be removed revealing a U-shaped passageway (15 cm wide, 147 cm total length) that ended in a rectangular enclosure 71 cm wide, 89 cm long). The walls of the rectangular compartment were featureless except for a cue card identical to that found in the cylinder attached to the wall opposite the entryway; thus this card was rotated 90° counterclockwise (CCW) with respect to the cue card in the cylindrical compartment (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Diagram of the Cylinder Task procedure. (B) Diagram of the Dual-Chamber Task procedure.

The room that housed the enclosures was dimly illuminated by four or eight lights symmetrically attached to the ceiling. Also mounted to the ceiling was a food pellet dispenser for motivating foraging behavior and a white noise generator to mask potential auditory cues. The enclosures were surrounded from floor to ceiling by a black curtain that eliminated exterior visual cues. The position and directional orientation of the rat was determined by an automated video tracking system (Ebtronics; Elmont, NY). This video tracking hardware provided x and y coordinates (256 × 256) of red and green light-emitting diodes secured 6 cm apart above the head and back of the animal, respectively.

Electrical signals recorded in the brain were passed through a field-effect transistor in a source-follower configuration. Signals were amplified by a factor of 10K to 50K, bandpass filtered (300–10,000 Hz, ≥3 dB/octave) and sent through a dual window discriminator (BAK Electronics) for spike discrimination. The firing rates of recorded cells and LED positions were saved onto a personal computer at a rate of 60 Hz. Data analysis was accomplished off-line using custom software (LabView, National Instruments, Austin, TX). The HD of the animal was determined by the relative position of the red and green LEDs.

Behavioral Tasks

Screening for HD cells began after surgical recovery. This involved examining the electrical signal on each of the 10 implanted wires while the animal foraged in the recording cylinder for food pellets. If no HD cells were detected, the electrode was advanced 25 to 50 μm and the animal was returned to its home cage. If a HD cell was identified, the animal was removed and the appropriate enclosure was prepared for data collection. Three different behavioral tasks were used in this study.

The first three cylinder sessions (the Cue Rotation series) assessed whether PPC lesions affected the stability of the HD signal and visual landmark control of HD activity. These sessions involved examining the directional activity of the HD cell while the animal foraged in the recording cylinder for 8 minutes. Figure 2A presents the procedure for these sessions. In the Cylinder-Standard session the cue card was placed at the 0° position. After this session, the visual landmark was rotated 90° in the CCW direction; this session was referred to as the Cylinder-Rotation session. Finally, in the Cylinder-Return session the cue card was returned to the 0° position. For each of these sessions the animal was given disorientation treatment before the recording session by placing it in a cardboard box and rotating it at approximately 0.5 Hz for approximately 60 seconds. Analysis of these sessions involved comparing the preferred directions of the recorded cells across the three sessions. To accomplish this analysis, we constructed a firing rate versus HD plot for each session by dividing the 360° directional range into 60 6° bins and then calculating the average firing rate for each bin. We then compared the plots from each session to determine how the position of the cue card affected the directional signal of recorded cells (see below).

We used two different tasks to assess whether PPC lesions affected idiothetic control of HD cell activity. Cylinder-Dark/No Cue sessions (Figure 2A) given to Control cells (n = 8) and PPC-Large cells (n = 11) after Cylinder-Return sessions, examined the stability of HD cells in the absence of visual landmarks. In these sessions the cue card was removed, the lights were extinguished, and the animal was allowed to forage for 24 minutes in the dark. The animal was not disoriented at the start of the session and the floor paper was not changed. The Dual-Chamber task involved the animal self-locomoting into a novel enclosure (Figure 2B). After disorientation treatment the animal was placed in the cylindrical compartment of the apparatus with the hidden door closed. After allowing the animal to forage for 16 minutes the door was opened and the animal was free to walk into the passageway and rectangular compartment. After the animal locomoted into the rectangular compartment the door was usually closed, trapping the animal inside, and the animal was allowed to forage for 16 minutes while the activity of the HD cell was monitored. In a few cases (n = 2 for Group PPC-Large, and n = 1 for Group Control) the door was left open and the animal was free to move between the enclosures of the apparatus. Unlike in the cylinder task, the Dual-Chamber sessions could be conducted only once per animal, since the task requires the rectangular compartment to be novel. Hence, only one HD cell recording session was collected per animal in this task.

Analysis of Cellular Data

Basic directional characteristics of the recorded cells were determined by examining cellular activity during the Cylinder-Standard session. Cells from lesioned and control animals were compared on measures of peak firing rate, background firing rate, signal-to-noise ratio, directional firing range, directional information content, and anticipatory time interval. The preferred direction was defined as the directional bin with the highest average firing rate. The peak firing rate was the average firing rate corresponding to the preferred direction. The background firing rate was the average firing rate of the three directional bins centered at 180° opposite the preferred direction. Signal-to-noise ratio was calculated as the peak firing rate divided by the background firing rate. The directional firing range was defined as the width at the base of the firing rate versus HD tuning curve (Taube et al., 1990a). Directional information content is a measure of how many bits of HD information is conveyed by each spike (Skaggs, McNaughton, Gothard, & Markus., 1993) and was calculated by the following formula: Directional Information Content = Σ pi (λi/λ) log2 (λi/λ), where pi is the probability that the head pointed in the ith directional bin, λi is the mean firing rate for bin i, and λ is the mean firing rate across all directional bins.

The anticipatory time interval (ATI) is a measure of the amount of time that cell firing best predicts where the animal will be pointing its head in the future. Previous work has estimated that the activity of ADN HD cells reflect HDs ~25 ms into the future better than current HDs (Blair & Sharp, 1995; Taube & Muller, 1998). Both sensory and motor inputs into the HD network have been postulated as a mechanism for this anticipatory activity (Bassett et al., 2005; Blair & Sharp, 1995; Taube & Muller, 1998). Because both types of signals may be found in PPC (reviewed above), it is possible that PPC may play a role in this phenomenon. Accordingly, we compared the ATI of Standard-Cylinder sessions in cells from control and PPC-lesioned animals using the methods of Blair and Sharp (1995). For this method, HD cell tuning functions were calculated for CW and CCW directions and the difference between the preferred firing directions for the two functions (separation angle) determined. Then the spike record was shifted forward and backward in time in steps of 16.67 ms (the maximum temporal resolution of the recording hardware) and the separation angle between the CW and CCW functions for head movements ≥90° computed for each shift. The spike series was shifted incrementally ±6 times (±100 ms) relative to the HD series, providing 13 values of CW-CCW separation angles. A scattergram was then constructed from the 13 CW-CCW separation angles and their corresponding time shift. The x-intercept of the best-fit line of this plot is referred to as the ATI and is equivalent to the amount of time that the spike series has to be shifted to achieve overlapping CW and CCW functions.

Circular statistics (Batschelet, 1981) were used to determine the stability of the directional signal in the cue rotation series, the cue removal sessions, and between the cylindrical and rectangular enclosures of the Dual-Chamber apparatus. Directional deviation scores across these conditions were calculated using a cross-correlation method (Taube & Burton, 1995). This approach involves shifting the firing rate/HD function of the first session in 6° increments while correlating this shifted function with the non-shifted function from the other session. The amount of shift required to produce the maximal Pearson r correlation between the two sessions is defined as the directional deviation score between the sessions. These scores were then subjected to Rayleigh tests (Batschelet, 1981) to determine if the scores were clustered randomly (as would be the case if the preferred directions were not controlled by landmark or idiothetic signals) or if the preferred directions tended to shift in the same direction and amount. The critical statistic of the Rayleigh test is the mean vector length, r, which varies between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating that the distribution of directions is more concentrated, (i.e., clustered nonrandomly; Batschelet, 1981). Also, calculated using these directional deviations was the mean vector angle, m, which estimates the mean angle of the sample (Batschelet, 1981).

Two inferential tests were utilized for between-groups comparisons of directional deviation scores produced during the cylinder and dual-chamber sessions. ANOVAs were used to determine if the absolute directional deviations between conditions were significantly different. The absolute values of the directional deviations were used because they could be either positive or negative depending on whether the deviations were CW or CCW from the expected value. We also utilized an F test of the concentration parameter of the directional deviation scores (Batschelet, 1981). This latter test determines if there is a difference among the groups in the concentration of directional scores around the mean value; an expected finding if lesioned animals show less coupling of preferred directions between multiple sessions of the cylinder task or between the two enclosures of the dual-chamber task.

Histology

At the completion of the experiments, animals were anesthetized deeply and a small anodal current (20 μA, 10 seconds) was passed through one electrode wire to later conduct a Prussian blue reaction. The animals were then perfused transcardially with saline followed by 10% formalin in saline. The brains were removed and placed in 10% formalin for at least 48 hours. The brains were then placed in a 10% formalin solution containing 2% potassium ferrocyanide for 24 hours and then reimmersed in 10% formalin (24 hours) before being placed in 20% sucrose for 24 hours. They were then frozen, sectioned (40 μm) in the coronal plane, stained with cresyl violet, and examined microscopically for localization of the recording and lesion sites. All recording electrodes were localized to the ADN.

Results

A total of 50 HD cells were recorded from the 28 animals, with 17, 14, and 19 cells recorded from PPC-Large, PPC-Small, and Control animals, respectively.

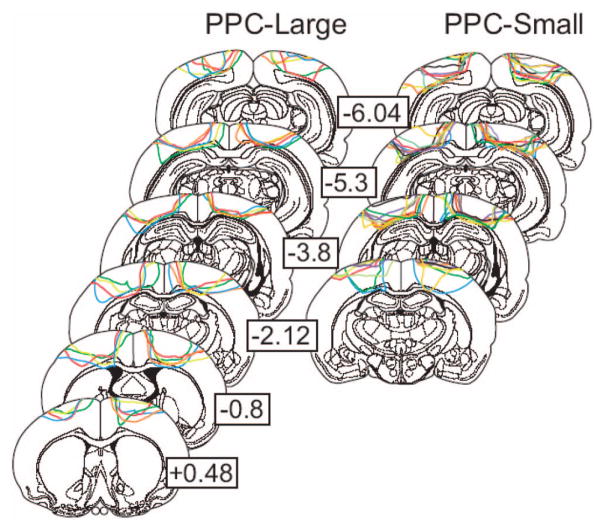

Lesion Data

Figure 3 shows the extent of lesions of PPC-Large and PPC-Small animals at select plates from Paxinos and Watson (1998). As is typical with aspiration lesions, deeper cortical tissue tended to be spared at the intended lesion borders. All animals showed at least partial damage to the external capsule below the targeted cortex. Some cingulum damage was found in all PPC-Large animals and five PPC-Small animals. Hippocampal damage down to the pyramidal layer of dorsal CA1 was observed in two PPC-Small animals. No other hippocampal damage was noted, and no damage was detected for deeper structures.

Figure 3.

Lesions for PPC-Large and PPC-Small animals at selected AP coordinates relative to Bregma. The lesion extent of each animal is represented by a different line color within each group. Because of damage caused during brain removal, histology could not be performed for one PPC-Large animal for the left side of plates +0.48 through 3.8, and for one PPC-Small animal for both sides of plate −2.12. Adapted from The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (4th ed.), G. Paxinos and C. Watson, 1998. Copyright 1998, with permission from Elsevier.

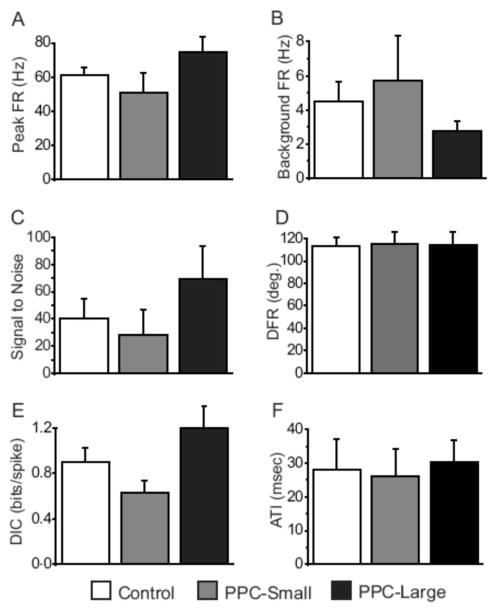

Basic Directional Characteristics

HD cell activity during the Cylinder-Standard sessions was used to determine the basic directionally dependent firing characteristics of cells from control and lesioned animals. Figure 4 presents average values for peak firing rate, background firing rate, signal-to-noise ratio, directional firing range, directional information content, and ATI for recorded cells. As the figure indicates, there were no obvious differences between lesioned animals and controls for these measures. Single factor ANOVAs found no effect of condition for any of these measures [Fs(2,33) = 1.81, 1.12, 1.06, 0.008, 2.81, and 0.06 for the six measures, ps > 0.05]. In summary, lesions of PPC failed to produce any significant effects on the basic directional-specific firing characteristics of HD cells in the ADN.

Figure 4.

Basic directional firing characteristics of HD cells in Control, PPC-Large, and PPC-Small animals. (A) Peak firing rate, (B) Background firing rate, (C) Signal-to-noise ratio, (D) Directional firing range (DFR), (E) Directional information content (DIC), (F) Anticipatory time interval (ATI). No significant differences existed between the groups for any of these measures.

Cylinder Sessions: Cue Rotation Series

All animals received their first exposure to the cylinder’s cue card during cell screening sessions, which began after the surgical lesions. Thus, the HD cells that we recorded had to assimilate the spatial information about the cue card without the PPC. Consequently, the amount of exposure each animal had to the cue card at the time of the recording session varied according to when the HD cells were encountered in our recordings. Because we often recorded multiple HD cells at different times from each animal in the cylinder task (average number of cells recorded per animal was 2.0; range = 1–5 cells), some cells were recorded after the animal had experienced many sessions in the cylinder. On average, the animals were exposed to the cue card for 15.6 ± 1.7 recording sessions (14.5 ± 1.5 days; ranges of 2–48 sessions and 2–41 days) before conducting the first cue rotation series for each cell. With a typical cell screening session lasting ~20 minutes, this means that the animals had been exposed to the cue card for 312 minutes, on average, at the time the cue rotation series were conducted.

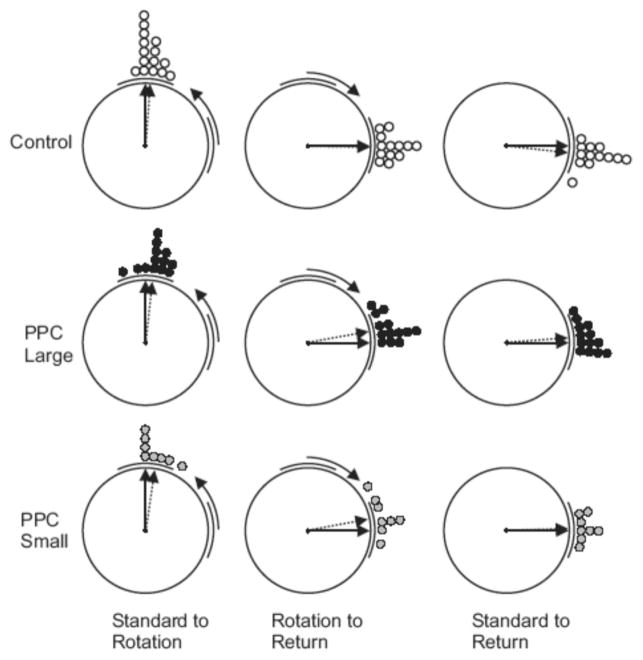

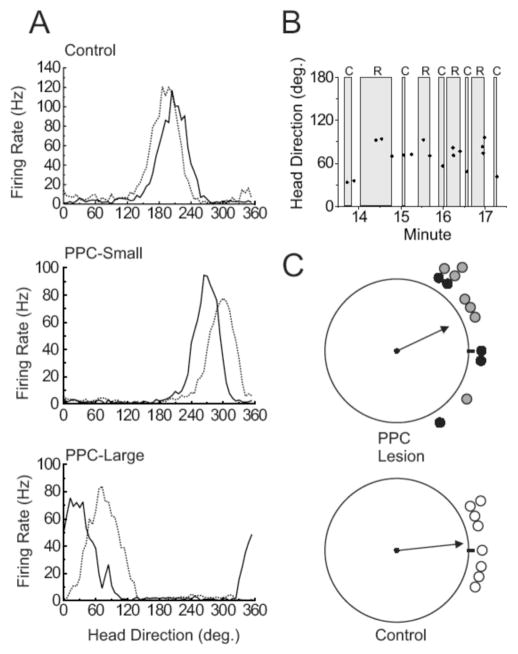

Figure 5 presents firing rate versus HD functions of representative cells from each of the three conditions recorded during the cue rotation series. As expected, cells from control animals showed reliable cue control of HD cell activity, with the preferred direction of recorded cells typically shifting in the same direction and amount as the cue rotation in the Cue Rotation sessions. Importantly, cells from both lesion groups also exhibited reliable cue control in these sessions. This result is also illustrated in the scatter diagrams of directional deviation scores between the different sessions shown in Figure 6. Specifically, during the transition between Standard and Rotation sessions, cells in all three groups showed reliable cue card control, with the preferred direction of most cells rotating in a similar direction and amount as the cue card. Rayleigh tests of deviation scores for these transitions were significantly distributed nonrandomly in all three conditions indicating that directional tuning was maintained across sessions [mean vector lengths (r) = 0.995, 0.987, and 0.984; mean vectors (m) = 86.0°, 84.0°, and 81.8° for Control, PPC-Large, and PPC-Small conditions, respectively; ps < 0.05]. A single factor ANOVA found no effect of lesion type on the absolute deviations from the expected preferred directions [F(2, 33) = 1.70, p >.05], with absolute directional deviations of 4.8 ± 1.5°, 9.7 ± 1.6°, and 8.3 ± 3.9° for Control, PPC-Large, and PPC-Small conditions, respectively. In addition, an F test of these data found no significant differences in the concentration parameter of these scores [F(12, 14) = 2.42, p >.05 for PPC-Large versus Control, and F(7, 14) = 3.09, p >.05, for PPC-Small versus Control].

Figure 5.

Representative firing rate/HD tuning curves for HD cells from Control, PPC-Large, and PPC-Small animals during the three sessions of the Cylinder Task. The solid line indicates the tuning curve during the Cylinder-Standard Task, the dotted line indicates the tuning curve during the Cylinder-Rotation Task, and the dashed line indicates the tuning curve during the Cylinder-Return Task.

Figure 6.

Scatter diagrams showing the amount of angular shift between Cylinder Task sessions for each experimental group. Each plot shows the angular shifts of preferred directions between pairs of sessions. The left column shows the amount of angular shift observed in the Cylinder-Rotation session relative to the Cylinder-Standard session. The middle column shows the amount of shift observed in the Cylinder-Return session relative to the Cylinder-Rotation session. The right column shows the amount of shift observed in the Cylinder-Return session relative to the Cylinder-Standard session. Each circle represents the amount of angular shift of the preferred direction of a single cell relative to the position of the cue card for the second session. The solid arrow denotes the expected mean vector angle if the angular shift is perfectly predicted by the cue card and the dotted arrow denotes the observed mean vector angle. The length of the dotted arrow denotes the mean vector length, with a length of 1.0 (no variability in shift scores) represented by a vector spanning the radius of the circle. Each plot uses Cartesian coordinates with 0° at the 3 o’clock position and increasing values proceeding in a CCW direction.

Similar findings occurred during transitions between the Rotation and Return sessions. Rayleigh tests indicated intact directional specificity between the Rotation and Return sessions for all three conditions (rs = 0.992, 0.987, and 0.971; ms = − 90.3°, −79.9°, and −79.5°, for Control, PPC-Large, and PPC-Small conditions, respectively; p <.05], and there were no differences in absolute shift deviation across the three lesion types [F(2, 31) = 2.08, p >.05; deviations of 5.5 ± 1.4°, 10.2 ± 2.8°, and 13.5 ± 4.2° respectively]. An F test of these data found no significant differences in the concentration parameter of the directional deviations between PPC-Large and control animals [F(12, 12) = 1.66, p >.05]. Interestingly, there was a significant increase in angular variance for cells from PC-Small animals compared with control [F(7, 12) = 3.75, p <.05]. Lastly, when the preferred directions of Standard sessions were compared to Return sessions, all three groups maintained directional specificity across the sessions (rs = 0.990, 0.967, and 0.991; ms = −6.4°, 4.1°, and 1.5° for Control, PPC-Large, and PPC-Small, respectively; p <.05), there were no group differences in absolute preferred directions across these sessions [F < 1; deviations of 7.4 ± 2.2°, 7.9 ± 2.0°, and 6.0 ± 2.0°, respectively], nor were there any significant differences in the concentration parameter between cells from lesioned animals and controls [F(12, 12) = 1.32, p >.05 for PPC-Large vs. control; F(12, 7) = 1.07, p >.05 for PPC-Small vs. control].

In summary, landmark control of HD activity in the cue rotation series appeared largely unaffected by PPC lesions. Although the observed absolute directional deviations between the first two transitions appeared somewhat larger for lesioned groups, this increase failed to reach significance by nearly every test and more importantly, these increases did not approach what would be expected if the visual landmark failed to control HD cell activity. These results indicate that despite lesions of the PPC, HD cells could acquire the necessary information about visual cues to enable them to become landmarks and control the preferred directions of HD cells.

Cue Removal Sessions in the Dark

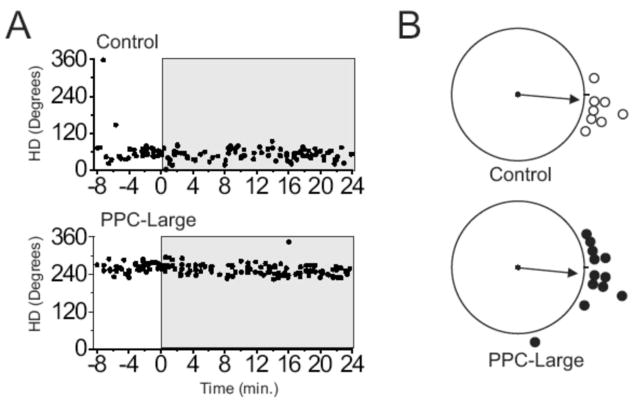

HD cells from both control and lesioned animals maintained stable directional correlates during the transition between Cylinder/Return sessions and Cylinder Dark/No Cue sessions, and this stable directional specificity typically remained during the entire 24 Minute Dark/No Cue sessions. Figure 7A demonstrates this stability in example cells from Control and PPC-Large conditions. In this figure, HD is indicated on the ordinate, while time is indicated on the abscissa with minutes −8 to 0 encompassing the Cylinder/Return session and Minutes 0 to 24 encompassing the Dark/No Cue session. The filled circles represent occasions in which the recorded cell fired at a rate equal or greater than 2 SDs above the mean firing rate, and for purposes of the figure are operationalized as instances of the animal facing the preferred direction of the cell. Using this type of analysis, cells that maintain stable directional correlates over time are readily detectable by showing instances of elevated cell activity clustered within a narrow range of HDs. To quantify this effect, we calculated the amount of shift between the 8-min Cylinder/Return session and the last 8 minutes of the Dark/No Cue session. Scatterplots of these directional deviation scores for the two conditions are shown in Figure 7B. Shifts were significantly nonrandomly distributed around the zero degree direction in both Control and PPC-Large animals [rs = 0.94 and 0.90, ms =−5.0° and −5.6°, for Control and PPC-Large conditions, respectively]. Mean absolute directional deviations between the light and dark sessions were 18 ± 4.4° for control animals and 19.1 ± 6.4° for PPC-Large conditions, a difference that failed to reach significance [F < 1]. Lastly, there was no difference in the concentration parameter of these scores [F(10, 7) = 1.5, p > .05]. This analysis showed that HD cells from lesioned animals were able to maintain a stable directional correlate even in the absence of visual landmarks.

Figure 7.

(A) Real-time plots of preferred directions of an example HD cell from a Control animal (top panel) and a PPC-Large animal (bottom panel) during Cylinder-Return and Cylinder-Dark/No-Cue sessions. HD is indicated on the ordinate while time is indicated on the abscissa. The gray region represents data from the Cylinder-Dark/No-Cue session. Filled circles represent occasions in which the recorded cell fired at a rate equal or greater than 2 SDs above the mean firing rate, and are operationalized as instances of the animal facing the preferred direction of the recorded cell. (B) Scatter diagrams showing the amount of angular shift between the Cylinder-Return session and the last 8 minutes of the Cylinder-Dark/No Cue sessions for each experimental group; 0° is located at the 3 o'clock position with increasing degree values proceeding in a CCW direction.

Dual-Chamber Sessions

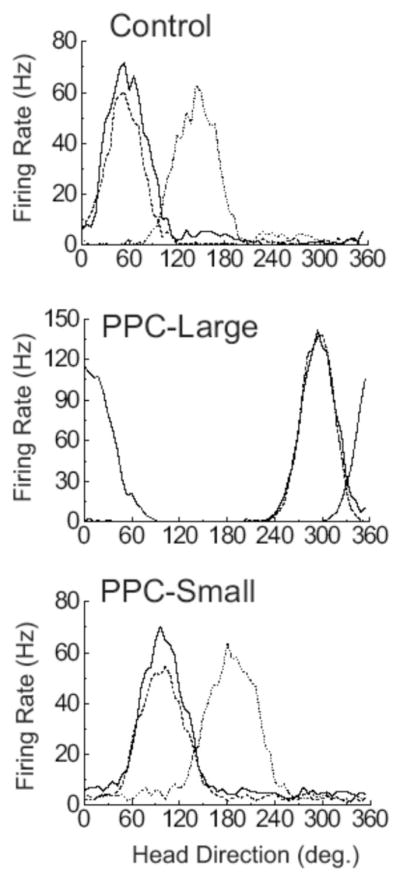

Representative firing rate versus HD functions from the three conditions during the Dual-Chamber sessions are shown in Figure 8A. Cells from control animals typically exhibited fairly stable preferred directions when the animal locomoted from the cylindrical enclosure to the rectangular enclosure. This finding is similar to that reported by Taube and Burton (1995), and indicates that HD cells in normal animals are able to utilize idiothetic cues to maintain a stable preferred firing direction during navigation into a novel environment. Compared to Controls, cells from both lesion conditions exhibited slightly less stable preferred firing directions when the animal made this transition. Although cells from Control animals showed an average absolute directional deviation of 19.5 ± 3.5° between the two enclosures, cells from PPC-Large and PPC-Small animals showed average absolute deviations of 36.0 ± 13.6° and 42.0 ± 5.2°, respectively. An ANOVA of these absolute deviations across the groups just missed significance [F(2, 17) = 3.12, p < .08)].

Figure 8.

A. Representative firing rate/HD tuning curves for HD cells from Control, PPC-Large, and PPC-Small animals during the Dual-Chamber Task. The solid line indicates the tuning curve while the animal was inside the cylindrical enclosure and the dotted line represents the tuning curve while the animal was inside the rectangular enclosure. (B) Real-time plots of preferred directions of a recorded cell as the animal moved between enclosures. HD is indicated on the ordinate, time is indicated on the abscissa. The filled circles represent occasions in which the recorded cell fired at a rate equal to or greater than 2 SDs above the mean firing rate. Filled regions indicate periods in which the animal was within the circular enclosure (C) or rectangular enclosure (R). (C) Scatter diagrams showing the amount of angular shift of preferred directions between the Dual-Chamber Cylindrical enclosure and Dual-Chamber Rectangular enclosure. Black-filled circles represent cells from PPC-Large animals, while gray-filled circles represent cells from PPC-Small animals. The solid arrows denote the mean vectors for the PPC-Lesion (small and large lesions combined) and Control groups; 0° is located at the 3 o'clock position with increasing degree values proceeding in a CCW direction.

In those PPC-lesioned animals that exhibited instability in the preferred direction between the cylinder and rectangle, the instability could be because of shifts occurring upon entry into the new environment or because of a slow drift occurring within that environment during a session. The former seemed to be the case— the large shifts occurred as the animal entered the rectangle. This result was also apparent in the two lesioned animals that were allowed to move repeatedly between the two enclosures. Figure 8B shows data from one of these cells in the same format as shown in Figure 7A. This cell clearly showed a 30° to 60° shift of preferred direction as the animal moved between the cylindrical (denoted by C) and rectangular (denoted by R) enclosures, and this shift was consistent across several excursions between the enclosures.

Because of the nature of the dual-chamber task (i.e., the rectangular enclosure is truly novel only once) we are only able to use one recording session from each animal, severely limiting our cell numbers for statistical analyses. Therefore, because the PPC-Large and PPC-Small groups failed to significantly differ from each other in this and all other analyses, we combined the two groups for the purposes of further statistical analyses. Figure 8C shows scatter diagrams of the directional deviations of each cell in lesioned animals (top panel) and control animals (bottom panel). A Rayleigh analysis found that cells from both groups showed non-random directional deviations (rs = 0.936 and 0.798, ms = 6.1° and 25.3° for Control and PPC animals, respectively). Although a single factor ANOVA using the absolute values of the directional deviations found that cells from lesioned animals showed greater deviations than cells from control animals [F(1, 18) = 6.14, p < .05; absolute deviations of 19.5° ± 3.5 and 39.5° ± 6.1 for Control and PPC animals, respectively], scores from lesioned animals failed to significantly differ from controls on the concentration parameter [F(11, 7) = 2.98, p > .05]; an unexpected outcome if animals were impaired at utilizing movement-related cues. Although directional deviation scores appeared less clustered around the zero deviation point (expected for perfect idiothetic control between the two enclosures) for the lesioned animals compared to the control animals, the most striking result from this diagram is how little the preferred firing directions shifted in the two lesion groups given the assumption that PPC is involved in processing movement-related information. Animals impaired at processing movement-related information would be expected to display a much larger deviation from zero, and possibly even a random distribution in the deviations from zero.

Previous studies have shown that the preferred firing directions of HD cells are sometimes skewed toward alignment with one of the four walls in a rectangular environment (Golob, Stackman, Wong, & Taube, 2001). Human studies have also reported a tendency for subjects to orient themselves along one of the major wall axes in a rectilinear environment (McNamara, Rump, & Werner, 2003). Thus, it is possible that if integration of idiothetic cues were impaired in lesioned animals, then any shift in the preferred firing direction in the rectangular chamber might become aligned with one of the four walls. We found no evidence for such an effect. To examine this possibility we divided the 360° range of directions into eight 45° pie-shaped slices, with four of these slices orienting toward a different side of the rectangular apparatus and the other four matched up to a different corner. We then looked at the preferred direction of cells in the rectangular apparatus. In the case of the large lesion group, three cells oriented toward a side and two oriented toward a corner. In the case of the small lesion group, two cells oriented toward a side and five cells toward a corner. This lesion distribution (5 vs. 7) was not different from the Control distribution (5 vs. 5), indicating there was no tendency for HD cells to align their preferred firing direction with the orientation of one of the four rectangular walls.

Discussion

The traditional view is that the dorsal visual stream emanating to the parietal cortex is important for processing the “where” aspects of visual information processing (e.g., Ungerleider & Mishkin, 1982) and many studies have supported the notion that the PPC is important in processing spatial information (Davis & McDaniel, 1993; DeCoteau & Kesner, 1998; DiMattia & Kesner, 1988; King & Corwin, 1993; Kolb & Walkey, 1987). Given that HD cells convey information about directional heading and spatial orientation it could be expected that parietal lesions would disrupt this spatial signal. However, our results showed that the HD cell signal remained intact after bilateral aspirations of the PPC. All measured properties that were used to characterize HD cell activity: peak and background firing rate, signal-to-noise ratio, directional firing range, directional information content, and anticipatory time intervals were similar between lesion and control animals. These findings strongly indicate that the PPC is not necessary for generating and maintaining direction-specific firing in the ADN. The fact that these basic firing characteristics of HD cells were unaffected is less surprising given other lesion studies have supported the view that the HD cell signal is generated subcortically, possibly in the connections between the dorsal tegmental nucleus and the lateral mammillary nuclei (Bassett et al., 2005; Blair & Sharp, 1998; for reviews see Sharp, Blair, & Cho, 2001; Taube, 2007), and the signal is then projected rostrally through connections with the ADN and other limbic system structures including the postsubiculum, retrosplenial cortex, and entorhinal cortex (see Figure 1). This circuit could then be influenced by PPC through its connections with retrosplenial cortex (Kolb & Walkey, 1987; Reep et al., 1994). The issue then arises what is the functional contribution of the PPC to spatial orientation in general, and to the HD cell signal more specifically?

PPC and Landmark Control of HD Cell Preferred Directions

Previous studies have found that animals are less able to navigate using visual landmarks after PPC lesions (Kolb & Walkey, 1987; Save & Poucet, 2000b), making our intact landmark control of HD cells after PPC lesions surprising. This lack of an effect is somewhat consistent with findings from hippocampal place cells in PPC lesioned animals (Save et al., 2005). In that study, 28 out of 36 place fields rotated near equal amounts when three objects placed in the arena were rotated out of view of the lesioned animal. Their findings differ from ours, however, in that all of our HD cells from lesioned animals rotated with the visual landmark. In addition, in the Save et al. (2005) study most of the place cells that had rotated with the landmarks reverted to their original (nonrotated) positions when the landmarks were removed in the presence of the lesioned animals. The authors concluded that the most likely explanation for this finding was that animals with PPC lesions showed a preference for the use of distal room cues for orientation relative to proximal cues. Many theories postulate that place cells and HD cells are interconnected elements of navigational circuitry (McNaughton et al., 1996; Sharp, 1999; Touretzky & Redish, 1996), and these cell types often respond similarly to manipulations (Knierim et al., 1995, 1998), making the difference between this place cell study and ours surprising. A likely explanation for this difference lies in the nature of the visual landmarks utilized in the present study and by Save et al. (2005). Our study used a white card attached to the wall of the enclosure as the visual landmark, whereas Save et al. (2005) used a trio of three-dimensional figures placed near the wall of the circular apparatus. Whereas there was no great difference in the distance of the landmarks relative to the animal, the three-dimensional characteristic of the landmarks utilized by Save et al. (2005) afforded the animal the chance to interact with the landmarks in a much more proximal way. Given previous findings that PPC lesions are more likely to impair navigation using proximal rather than distal landmarks (Save & Poucet, 2000b), and findings that when a conflict occurs between the location of proximal and distal cues some place cells are more controlled by proximal landmarks, others are more controlled by distal landmarks, while still others show remapping (Renaudineau, Poucet, & Save, 2007; Shapiro, Tanila, & Eichenbaum, 1997; Yoganarasimha, Yu, & Knierim, 2006), it is not surprising that PPC lesions affected proximal landmark control of some, but not all, place cells in the Save et al. (2005) study.

Several studies, however, have found that visual landmark control of HD cell functioning is controlled by the most distant landmark in the enclosure. For instance, Zugaro, Berthoz, and Wiener (2001) recorded HD cells while the animal foraged on a circular platform with three geometric figures spaced equally along the perimeter of the platform. When a wall was placed between the geometric figures and the edge of the platform (blocking the animal's view of the surrounding room), rotation of the figures caused an equal rotation of HD cell preferred direction. In contrast, when the wall was absent, making the most distant visual landmarks the features of the surrounding room, the position of the geometric figures was ineffective at controlling HD cell directionality. In addition, Yoganarasimha et al. (2006) showed that while within the same session some place cells were controlled by proximal landmarks and other place cells were controlled by distal landmarks, HD cells were nearly universally controlled by the distal landmarks. The authors suggested that proximal and distal information impinges on the place cell system via different routes, with proximal information arriving through pathways independent of the HD system. In summary, it is likely that while the HD system is preferentially controlled by the most distal visual landmarks, the place cell system is controlled by both proximal and distal landmarks. PPC, by virtue of its role as a convergence area of both motor and sensory information could play an important role in orientating to proximal landmarks with which the animal can intimately interact.

Our failure to observe decrements of cue card control in PPC-lesioned animals is evidence that substantial landmark information enters the HD circuitry via a route other than through PPC. A number of alternative routes exist (see Figure 1). For instance, cortically processed visual information could bypass PPC by way of inputs from primary and secondary visual cortex to retrosplenial cortex and postsubiculum (Vogt & Miller, 1983). In support of this possibility, animals with retrosplenial lesions show a variety of visuospatial deficits (Vann & Aggleton, 2005; Whishaw, Maaswinkel, Gonzalez, & Kolb, 2001) and there is preliminary evidence for the instability in the preferred direction of HD cells after retrosplenial lesions (Bassett & Taube, 1999). Additionally, previous studies have suggested that the postsubiculum is instrumental for processing information concerning visual landmarks, as lesions of the postsubiculum led to unequal shifts in ADN HD cell preferred directions (Goodridge & Taube, 1997) and in place fields of hippocampal place cells after rotation of the prominent visual landmark in cue rotation experiments (Calton et al., 2003). Another source of visual input is the tectocortical pathway, through which most retinal ganglion cells project (Linden & Perry, 1983). In this pathway, visual inputs could arrive via connections between superior colliculus, pretectal areas, and thalamic nuclei; most notably the lateral dorsal thalamus (Thompson & Robertson, 1987), an area also containing HD cells (Mizumori & Williams, 1993). Lesions of the superior colliculus result in deficits of orientation and navigation (Dean & Key, 1981; Dean & Redgrave, 1984; Lines & Milner, 1985), and rat superior collicular neurons have been shown to possess visually dependent movement related activity during a navigational task (Cooper, Miya, & Mizumori, 1998). However, the finding that lesions of the lateral dorsal thalamus do not disrupt cue control in HD cells (Golob, Wolk, & Taube, 1998) discounts the likelihood that the tectocortical pathway is important.

Selection ofVisual Cues as Landmarks

Our failure to observe a deficit in cue card control after PPC lesions is also evidence that intact PPC functioning is not necessary for a new landmark cue to gain control over the directional specificity of the HD network. McNaughton, Chen, and Markus (1991) suggested that for a landmark to provide a useful signal for navigational circuitry, an association must be made between the stable landmark and a preexisting directional reference, likely idiothetic in nature. Furthermore, a number of studies have shown that the ability of a landmark to control HD cell and place cell activity can be modified by experience (Goodridge, Dudchenko, Worboys, Golob, & Taube, 1998; Knierim et al., 1995, 1998). The convergence of sensory and motor signals in PPC, and the close anatomical connections between PPC and navigational circuitry, provides a possible role for the PPC in this form of learning (McNaughton et al., 1989, 1996; Save & Poucet, 2000a). Our animals received their lesions before exposure to the recording enclosure, and yet HD cells were still accurately controlled by the position of the salient visual landmark in the apparatus, providing strong evidence that PPC does not play a crucial role in the ability of a visual cue to become selected as a stable directional reference for the HD system. This finding suggests that the ventral visual pathways through the inferior temporal and perirhinal cortices (Miller & Vogt, 1984) may be instrumental in the selection and acquisition of appropriate visual landmarks. Consistent with this view, studies in rats that have lesioned portions of the perirhinal cortex that are referred to as postrhinal cortex (Burwell & Amaral, 1998a, b), have found deficits in visual spatial tasks (Aggleton, Keen, Warburton, & Bussey, 1997; Liu & Bilkey, 2002; Winters, Forwood, Cowell, Saksida, & Bussey, 2004). Alternatively, as mentioned above visual landmark acquisition may emerge through direct projections from visual cortex to the retrosplenial cortex and postsubiculum (Vogt & Miller, 1983).

PPC and Path Integration

Two forms of navigation have been described based on the types of guidance cues utilized. In the case of landmark navigation, the animal is guided by the location of familiar landmarks in the environment and knowledge of the position of those landmarks relative to the destination. Alternatively, path-integration involves the use of idiothetic signals generated during movement (e.g., vestibular, proprioceptive, or efferent copy signals) to localize position and guide future movement (Mittelstaedt & Mittelstaedt, 1980). HD cells respond to both types of navigational cues, providing support for the view that the HD network is an important component to the navigational system. Our finding that visual landmarks exerted normal control over the preferred firing direction of HD cells from PPC lesioned animals suggests that the PPC is not necessary for accurate use of visual landmarks by the HD system.

The Cylinder-Dark/No Cue and Dual-Chamber tasks assessed whether PPC-lesions affected the use of idiothetic cues by the HD cell network. Cells from lesioned animals were largely unaffected by the removal of the visual landmarks in the Cylinder-Dark/No Cue task, demonstrating that these cells were able to use nonvisual information to maintain an accurate directional signal. On the other hand, HD cells and place cells have been shown to respond partly to nonvisual cues (presumably olfactory in nature) after the elimination of visual landmarks (Goodridge et al., 1998; Save, Nerad, & Poucet, 2000) so it is possible that these Dark-No Cue sessions did not force the animal to rely on path-integration. The dual-chamber task provided a more complete assessment of the ability of HD cells to use idiothetic cues after PPC lesions.

Our results from the dual-chamber task show that HD cells in PPC-lesioned animals can maintain a relatively stable preferred firing direction as the animal moves between a familiar and novel environment. One interpretation of this finding is that this task requires the use of idiothetic cues and that PPC lesioned animals remain capable of processing these cues over time and integrating them with their current orientation. This possibility may not be surprising since there are appropriate idiothetic signals available in many of the subcortical areas involved in generating and processing the HD cell signal (reviewed by Taube, 2007). Alternatively, the maintenance of a stable preferred direction in the dual chamber task may arise because of mechanisms other than processing idiothetic cues. For example, it is possible that the preferred directions are maintained through a series of associative processes that, through the use of geometric cues across the different environments, can link the preferred direction between the cylinder and the rectangle chambers. Further experiments that use more circuitous and lengthy routes, which more rigorously test path integration mechanisms, will be necessary before firmly concluding that the PPC is not involved in mechanisms of path integration.

Although the dual-chamber task is relatively simple, maintaining a stable preferred firing direction for a HD cell on the task has been sufficiently sensitive to various manipulations. For example, lesions of the hippocampus have been shown to impair the ability of HD cells to maintain a stable preferred direction in this task (Golob & Taube, 1999). Similarly, depriving the animal of normal volitional motor cues during the task (i.e., proprioception and motor efference copy) also impairs the ability of HD cells to maintain a stable preferred direction in this task (Stackman, Golob, Bassett, & Taube, 2003). Thus, the absence of a major impairment in this task after PPC lesions is consistent with the view that the PPC is not needed to process and update idiothetic cues for HD cell activity. Our results in the no cue card dark sessions are also consistent with this view, because the preferred firing directions in the lesioned animals were relatively stable throughout these sessions.

Our findings that PPC lesions only mildly impaired the ability of HD cells to use idiothetic cues to maintain a stable preferred direction are similar to results reported by Golob and Taube (1999) who, using the same task, lesioned cortical areas overlying the dorsal hippocampus as a control for collateral damage which occurred when lesioning the hippocampus. Our PPC lesions included most of the areas lesioned by Golob and Taube, including portions of Oc1 and Oc2, but also included more lateral areas that are considered PPC; thereby making these lesions more complete PPC lesions. Shifts in the preferred direction were relatively mild for both studies and suggests that it is unlikely that these cortical areas, including PPC, play a major role in the ability of HD cells to use idiothetic cues in maintaining a stable preferred direction. One explanation for these results is that large areas of retrosplenial cortex were spared in both studies, and previous experiments have shown that animals with retrosplenial cortex lesions are impaired in tasks that emphasize the use of idiothetic cues (Cooper, Manka, & Mizumori, 2001; Cooper & Mizumori, 1999; Whishaw et al., 2001).

A number of investigators, however, have found that PPC lesions cause deficits in path integration (Commins, Gemmell, Anderson, Gigg, & O'Mara, 1999; Save & Moghaddam, 1996). For instance, using the table-top homing task Save et al. (2001) found that animals with PPC lesions were less likely to take a direct route when returning to the nest from a foraging excursion. Further, Rogers and Kesner (2006) recently reported that parietal lesioned animals show deficits in both acquisition and retention of a spatial task when required to use idiothetic cues in a modified Hebb-Williams maze. Our findings, however, support the view that parietal cortex contributes some other aspect to path integration processes. Keeping track of ones path through an environment may involve a number of different processes and brain areas. It is possible that the processing of idiothetic cues used to update the perceived directional heading occurs elsewhere in the brain, but then is integrated with other spatial information in the parietal cortex about location, reference frames, or the order of navigational epochs along a route (Nitz, 2006). Frohardt, Bassett and Taube (2006) found that lesions of the dorsal tegmental nucleus, an area known to be important for generating the directional signal (Bassett, Tullman, & Taube, 2006), severely impaired performance in a spatial task requiring path integration. Our findings along with other findings demonstrating path-integration deficits after PPC lesions could be explained if other HD cell pathways to the cortex (dorsal tegmental nucleus → lateral mammillary nuclei → ADN → postsubiculum → entorhinal cortex; Sharp et al., 2001; Taube & Bassett, 2003) enabled normal updating of the directional signal, but then this information was unable to be integrated with spatial information in the PPC.

Several other brain areas are thought to be important for path integration. The nature of the grid cell correlate in entorhinal cortex makes this signal an ideal candidate for processes involved with updating an animal’s path through the environment (Hafting et al., 2005; McNaughton, Battaglia, Jensen, Moser, & Moser, 2006). It would be interesting to determine whether lesions of the PPC interfere with the grid cell correlate. However, because the entorhinal cortex receives a significant portion of its afferent information from the ADN → postsubiculum pathway, the function of which appears relatively intact after PPC lesions, we would postulate that HD and grid cells in the entorhinal cortex would be similarly unaffected by PPC lesions in terms of landmark control and spatial updating. Finally, the hippocampus may also be involved in processing path integration information (Maaswinkel et al., 1999; McNaughton et al., 1996; cf., Alyan & McNaughton, 1999). As with lesions of PPC, hippocampal lesions do not disrupt HD cell responses or landmark control of their preferred firing directions (Golob & Taube, 1997), but they do, however, impair the ability to maintain a stable preferred firing direction when animals move to a novel environment in the dual-chamber foraging task (Golob & Taube, 1999).

In summary, the PPC does not appear to be important for either landmark control or integrating idiothetic cues for “normal” HD cell responses. Because numerous studies have indicated an important role for PPC in spatial information processing, the PPC is likely involved in processing other types or aspects of spatial information that are not critical for normal HD cell function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through the NASA Cooperative Agreement NCC9-58 with the National Space Biomedical Research Institute and National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH48924 and MH01286 to J.S. Taube and MH06258 to J.L. Calton. A preliminary report of this research was presented at the 31st annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience held in San Diego, CA in 2001.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey L. Calton, Department of Psychology, California State University–Sacramento and Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Dartmouth College

Carol S. Turner, Department of Psychology, California State University–Sacramento

De-Laine M. Cyrenne, Department of Psychology, California State University–Sacramento

Brian R. Lee, Department of Psychology, California State University–Sacramento

Jeffrey S. Taube, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Dartmouth College

References

- Aggleton JP, Keen S, Warburton EC, Bussey TJ. Extensive cytotoxic lesions involving both the rhinal cortices and area TE impair recognition but spare spatial alternation in the rat. Brain Research Bulletin. 1997;43:279–287. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(97)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alyan S, McNaughton BL. Hippocampectomized rats are capable of homing by path integration. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1999;113:19–31. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RA, Snyder LH, Bradley DC, Xing J. Multimodal representation of space in the posterior parietal cortex and its use in planning movements. Annual Reviews of Neuroscience. 1997;20:303–330. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbib MA. From visual affordances in monkey parietal cortex to hippocampo-parietal interactions underlying rat navigation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B Biological Sciences. 1997;352:1429–1436. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett JP, Taube JS. Retrosplenial cortex lesions disrupt stability of head direction cell activity. Society of Neuroscience Abstracts. 1999;25:1383. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett JP, Tullman ML, Taube JS. Lesions of the tegmento-mammillary circuit in the head direction system disrupts the head direction signal in the anterior thalamus. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;27:7564–7577. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0268-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett JP, Zugaro MB, Muir GM, Golob EJ, Muller RU, Taube JS. Passive movements of the head do not abolish anticipatory firing properties of head direction cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2005;93:1304–1316. doi: 10.1152/jn.00490.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batschelet E. Circular statistics in biology. New York: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Blair HT, Sharp PE. Anticipatory head direction signals in anterior thalamus: Evidence for a thalamocortical circuit that integrates angular head motion to compute head direction. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:6260–6270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06260.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RD, Amaral DA. Perirhinal and postrhinal cortices of the rat: Interconnectivity and connections with the entorhinal cortex. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1998a;391:293–321. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980216)391:3<293::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RD, Amaral DA. Cortical afferents of the perirhinal, postrhinal, and entorhinal cortices of the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1998b;398:179–205. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980824)398:2<179::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calton JL, Stackman RW, Goodridge JP, Archey WB, Dudchenko PA, Taube JS. Hippocampal place cell instability following lesions of the head direction cell network. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:9719–9731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-30-09719.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LL, Lin LH, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Head-direction cells in the rat posterior cortex: I. Anatomical distribution and behavioral modulation. Experimental Brain Research. 1994a;101:8–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00243212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LL, Lin LH, Green EJ, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Head-direction cells in the rat posterior cortex: II. Contributions of visual and idiothetic information to the directional firing. Experimental Brain Research. 1994b;101:24–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00243213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby CL, Goldberg ME. Space and attention in parietal cortex. Annual Reviews of Neuroscience. 1999;22:319–349. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commins S, Gemmell C, Anderson M, Gigg J, O’Mara SM. Disorientation combined with bilateral parietal cortex lesions causes path integration deficits in the water maze. Behavioral Brain Research. 1999;104:197–200. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BG, Manka TF, Mizumori SJY. Finding your way in the dark: The retrosplenial cortex contributes to spatial memory and navigation without visual cues. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2001;115:1012–1028. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.5.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BG, Miya DY, Mizumori SJY. Superior colliculus and active navigation: Role of visual and nonvisual cues in controlling cellular representations of space. Hippocampus. 1998;8:340–372. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:4<340::AID-HIPO4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BG, Mizumori SJY. Retrosplenial cortex inactivation selectively impairs navigation in darkness. Neuroreport. 1999;10:625– 630. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199902250-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin JV, Reep RL. Rodent posterior parietal cortex as a component of a cortical network mediating directed spatial attention. Psychobiology. 1998;26:87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Davis BK, McDaniel WF. Visual memory and visual spatial functions in the rat following parietal and temporal cortex injuries. Physiology and Behavior. 1993;53:145–151. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P, Key C. Spatial deficits on radial maze after large tectal lesions in rats: Possible role of impaired scanning. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1981;32:170–190. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(81)90447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P, Redgrave P. The superior colliculus and visual neglect in rat and hamster. I. Behavioural evidence. Brain Research. 1984;320:129–141. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(84)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoteau WE, Kesner RP. Effects of hippocampal and parietal cortex lesions on the processing of multiple-object scenes. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1998;112:68–82. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMattia BV, Kesner RP. Role of the posterior parietal association cortex in the processing of spatial event information. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1988;102:397–403. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohardt RJ, Bassett JP, Taube JS. Path integration and lesions within the head direction cell circuit: Comparison between the roles of the anterodorsal thalamus and dorsal tegmental nucleus. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;120:135–149. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR. The organization of learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Golob EJ, Stackman RW, Wong AC, Taube JS. On the behavioral significance of head direction cells: Neural and behavioral dynamics during spatial memory tasks. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2001;115:285–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golob EJ, Taube JS. Head direction cells and episodic spatial information in rats without a hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 1997;94:7645–7650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golob EJ, Taube JS. Head direction cells in rats with hippocampal or overlying neocortical lesions: Evidence for impaired angular path integration. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:7198–7211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-07198.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golob EJ, Wolk DA, Taube JS. Recordings of postsubicular head direction cells following lesions of the lateral dorsal thalamic nucleus. Brain Research. 1998;780:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich-Hunsaker NJ, Hunsaker MR, Kessner RP. Dissociating the role of the parietal cortex and dorsal hippocampus for spatial information processing. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119:1307– 1315. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.5.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge JP, Dudchenko PA, Worboys KA, Golob EJ, Taube JS. Cue control and head direction cells. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1998;112:749–761. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge JP, Taube JS. Interaction between postsubiculum and anterior thalamus in the generation of head direction cell activity. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:9315–9330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09315.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafting T, Fyhn M, Molden S, Moser MB, Moser EI. Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex. Nature. 2005;436:801–806. doi: 10.1038/nature03721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King VR, Corwin JV. Comparisons of hemi-inattention produced by unilateral lesions of the posterior parietal cortex or medial agranular prefrontal cortex in rats: Neglect, extinction, and the role of stimulus distance. Behavioral Brain Research. 1993;54:117–131. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knierim JJ, Kudrimoti HS, McNaughton BL. Place cells, head direction cells, and the learning of landmark stability. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:1648–1659. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01648.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knierim JJ, Kudrimoti HS, McNaughton BL. Interactions between idiothetic cues and external landmarks in the control of place cells and head direction cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:425–446. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B, Walkey J. Behavioral and anatomical studies of the posterior parietal cortex in the rat. Behavioral Brain Research. 1987;23:127–145. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(87)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubie JL. A driveable bundle of microwires for collecting single-unit data from freely-moving rats. Physiology and Behavior. 1984;32:115–118. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden R, Perry VH. Massive retinotectal projection in rats. Brain Research. 1983;272:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lines CR, Milner AD. A deficit in ambient visual guidance following superior colliculus lesions in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1985;99:707–716. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.99.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Bilkey DK. The effects of NMDA lesions centered on the postrhinal cortex on spatial memory tasks in the rat. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;116:860–873. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.5.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maaswinkel H, Jarrard LE, Whishaw IQ. Hippocampectomized rats are impaired in homing by path integration. Hippocampus. 1999;9:553–561. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:5<553::AID-HIPO9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara TP, Rump B, Werner S. Egocentric and geocentric frames of reference in memory of large-scale space. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2003;10:589–595. doi: 10.3758/bf03196519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Gerrard JL, Gothard K, Jung MW, Knierim JJ, et al. Deciphering the hippocampal polyglot: The hippocampus as a path integration system. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1996;199:173–185. doi: 10.1242/jeb.199.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Battaglia FP, Jensen O, Moser EI, Moser MB. Path integration and the neural basis of the ‘cognitive map’. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:663–678. doi: 10.1038/nrn1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Chen LL, Markus EJ. “Dead reckoning”, landmark learning, and the sense of direction: A neurophysiological and computational hypothesis. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1991;3:190–202. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1991.3.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Leonard B, Chen L. Cortical-hippocampal interactions and cognitive mapping: A hypothesis based on reintegration of the parietal and inferotemporal pathways for visual processing. Psychobiology. 1989;17:230–235. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Mizumori SJY, Barnes CA, Marquis JLM, Green EJ. Cortical representation of motion during unrestrained spatial navigation in the rat. Cerebral Cortex. 1994;4:7–39. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Vogt BA. Direct connections of rat visual cortex with sensory, motor, and association cortices. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1984;226:184–202. doi: 10.1002/cne.902260204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelstaedt ML, Mittelstaedt H. Homing by path integration in a mammal. Naturwissenschaften. 1980;67:566–567. [Google Scholar]

- Mizumori SJ, Williams JD. Directionally selective mnemonic properties of neurons in the lateral dosal nucleus of the thalamus of rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:4015–4028. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-04015.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RU, Kubie JL. The effects of changes in the environment on the spatial firing properties of hippocampal complex-spike cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1987;7:1951–1968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-01951.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K. Auditory spatial discriminatory and mnemonic neurons in rat posterior parietal cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82:2503–2517. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitz DA. Tracking route progression in the posterior parietal cortex. Neuron. 2006;49:747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J, Dostrovsky J. The hippocampus as a spatial map: Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Research. 1971;34:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomero-Gallagher N, Zilles K. Isocortex. In: Paxinos G, editor. The rat nervous system. 2. New York: Academic Press; 2004. pp. 729–757. [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 4. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Muller RU, Kubie JL. The firing of hippocampal place cells in the dark depends on the rat’s recent experience. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:2008–2017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-06-02008.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reep RL, Chandler HC, King V, Corwin JV. Rat posterior parietal cortex: Topography of corticocortical and thalamic connections. Experimental Brain Research. 1994;100:67–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00227280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaudineau S, Poucet B, Save E. Flexible use of proximal objects and distal cues by hippocampal place cells. Hippocampus. 2007;17:381–385. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JL, Kesner RP. Lesions of the dorsal hippocampus or parietal cortex differentially affect spatial information processing. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;120:852–860. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.4.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save E, Guazzelli A, Poucet B. Dissociation of the effects of bilateral lesions of the dorsal hippocampus and parietal cortex on path integration in the rat. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2001;115:1212–1223. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.6.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save E, Moghaddam M. Effects of lesions of the associative parietal cortex on the acquisition and use of spatial memory in egocentric and allocentric navigation tasks in the rat. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1996;110:74–85. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save E, Nerad L, Poucet B. Contribution of multiple sensory information to place field stability in hippocampal place cells. Hippocampus. 2000;10:64–76. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<64::AID-HIPO7>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save E, Paz-Villagran V, Alexinsky T, Poucet B. Functional interaction between the associative parietal cortex and hippocampal place cell firing in the rat. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;21:522–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save E, Poucet B. Hippocampal-parietal cortical interactions in spatial cognition. Hippocampus. 2000a;10:491–499. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4<491::AID-HIPO16>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save E, Poucet B. Involvement of the hippocampus and associative parietal cortex in the use of proximal and distal landmarks for navigation. Behavioral Brain Research. 2000b;109:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro ML, Tanila H, Eichenbaum H. Cues that hippocampal place cells encode: Dynamic and hierarchical representation of local and distal stimuli. Hippocampus. 1997;7:624–642. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1997)7:6<624::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PE. Complimentary roles for hippocampal versus subicular/entorhinal place cells in coding place, context, and events. Hippocampus. 1999;9:432–443. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:4<432::AID-HIPO9>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PE, Blair HT, Cho J. The anatomical and computational basis of the rat head-direction cell signal. Trends in Neuroscience. 2001;24:289–294. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL, Gothard KM, Markus EJ. An information-theoretic approach to deciphering the hippocampal code. In: Hanson SJ, Cowan JD, Giles CL, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 5. San Mateo, CA: Morgan Kaufmann; 1993. pp. 1030–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Sripanidkulchai K, Wyss JM. Thalamic projections to retrosplenial cortex in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1986;254:143–165. doi: 10.1002/cne.902540202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackman RW, Golob EJ, Bassett JP, Taube JS. Passive transport disrupts directional path integration by rat head direction cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003;90:2862–2874. doi: 10.1152/jn.00346.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]