Abstract

The relation of α-synuclein (αS) aggregation to Parkinson's disease (PD) has long been recognized, but the mechanism of toxicity, the pathogenic species and its molecular properties are yet to be identified. To obtain insight into the function different aggregated αS species have in neurotoxicity in vivo, we generated αS variants by a structure-based rational design. Biophysical analysis revealed that the αS mutants have a reduced fibrillization propensity, but form increased amounts of soluble oligomers. To assess their biological response in vivo, we studied the effects of the biophysically defined pre-fibrillar αS mutants after expression in tissue culture cells, in mammalian neurons and in PD model organisms, such as Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. The results show a striking correlation between αS aggregates with impaired β-structure, neuronal toxicity and behavioural defects, and they establish a tight link between the biophysical properties of multimeric αS species and their in vivo function.

Keywords: neurodegeneration, oligomer, Parkinson's disease, structure, α-synuclein

Introduction

The pathological hallmark of Parkinson's disease (PD) and several other neurodegenerative disorders is the deposition of intracytoplasmic neuronal inclusions termed Lewy bodies (Goedert, 2001). The major components of Lewy bodies are amyloid fibrils of the protein α-synuclein (αS) (Spillantini et al, 1997). Mutations of αS associated with familial PD (A30P, A53T, E46K) have an increased aggregation propensity in vitro, in agreement with the aggregation of αS into fibrillar Lewy bodies in vivo (Conway et al, 2000; Greenbaum et al, 2005). To study the pathogenic events of PD, a wide range of model systems have thus been described that rely on overexpression of αS and range in complexity from in vitro, to yeast, cell culture, worm, fly, mouse and primate (Feany and Bender, 2000; Nass and Blakely, 2003; Outeiro and Lindquist, 2003; Meredith et al, 2008). In several of these model systems, the rate of fibril and inclusion body formation does not correlate with neurotoxicity (Outeiro and Lindquist, 2003; Chen and Feany, 2005; Volles and Lansbury, 2007). This lack of correlation forms the basis for the hypothesis that small oligomers, but not fibrils, are the most toxic species of αS (Lashuel and Lansbury, 2006). However, the functions of different aggregated αS species for neurotoxicity in vivo are still unclear (Cookson and van der Brug, 2008), as overexpression of wild type, genetic mutants, phosphorylation mimics and truncation mutants of αS result in various aggregate species in vivo and induce different degrees of toxicity in different PD model systems (Feany and Bender, 2000; Masliah et al, 2000; Outeiro and Lindquist, 2003; Chen and Feany, 2005; Periquet et al, 2007; Volles and Lansbury, 2007; Gorbatyuk et al, 2008). Moreover, structural data for aggregation intermediates of αS are highly limited because of their transient and heterogeneous nature (Lashuel and Lansbury, 2006).

To obtain insight into the structure of different aggregate species of αS and their toxicity in vivo we designed, based on the structural information of the monomeric and fibrillar state of αS, αS mutants with radically different aggregation properties. We then correlated their ability to form amyloid fibrils with the degree of neurotoxictiy in four established model systems for PD (human embryonic kidney cells (Opazo et al, 2008), C. elegans (Nass and Blakely, 2003), Drosophila (Feany and Bender, 2000) and mammalian neurons (Zhou et al, 2000)). The structural properties of the aggregates formed by the αS mutants were characterized at single-residue resolution by solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Results

Structure-based design mutants of αS delay fibril formation

We based our design on the conformational properties of the αS monomer in solution and on the topology of αS fibrils known from previous NMR measurements (Bertoncini et al, 2005; Heise et al, 2005; Vilar et al, 2008). The genetic mutation A30P is located in a region of αS that is statically disordered in amyloid fibrils (Heise et al, 2005). To interfere with aggregation, we moved the single proline mutation found in the genetic A30P mutant to a position that is part of the β-sheet rich core of αS fibrils (Figure 1A). We selected Ala 56 and Ala 76 that are characterized by relatively large residual dipolar coupling values in the soluble monomer, suggestive of a rigid nature (Bertoncini et al, 2005). The following αS variants were generated: A30P, A56P, A76P, A30P/A56P, A30P/A76P and A30P/A56P/A76P (TP αS).

Figure 1.

Structure-based design mutants impair fibrillation of αS. (A) Functional domains of αS. Familial mutants (black) and structure-based design mutants (red) are labelled along the sequence. Regions involved in β-sheet formation in the fibril (Heise et al, 2005) are marked (purple). (B) Fibril formation of wt αS (black), A56P αS (yellow) and TP αS (red) followed by Thioflavin T fluorescence (ThT). Data for A30P, A76P, A30PA56P, A30PA76P are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. (C) Consumption of monomeric wt αS (black), A53T αS (cyan), A30P αS (purple), A56P αS (yellow) and TP αS (red) monitored through 1D 1H NMR spectroscopy. Drop in signal intensity is due to the formation of higher molecular weight aggregates not detectable by solution-state NMR. Errors were estimated from three independent aggregation assays. (D) Fibril formation of wt αS (black), A30P (purple), A53T (blue), A56P αS (yellow) and TP αS (red, also shown in Inset a at a different scale) followed by ThT fluorescence emission intensity. Inset b shows ThT intensity values of all but TP variants, each of them normalized by the maximal value observed along their aggregation reaction.

In agreement with the known β-breaking propensity of proline residues, the proline mutations markedly slowed down fibril formation. Although 0.1 mM samples of wt and A30P αS formed fibrils after about 20–30 h, as probed by thioflavin T (ThioT) fluorescence, A56P, A30PA56P and A30PA76P αS had an approximately five time longer lag phase (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1). In addition, their fibril elongation rate was strongly reduced, suggesting a reduced cooperativity of the transition. TP αS did not show any fibrils even after two weeks of incubation (Figure 1B). A quantitative analysis of the NMR signal decay showed that after 50 h of incubation at 37°C and 0.1 mM protein concentration, the oligomeric intermediates constituted a 6% and 2% fraction of the protein mixture for A56P and TP αS, respectively. In the case of TP αS, the oligomeric fraction increased to 4% after 160 h (Figure 1C).

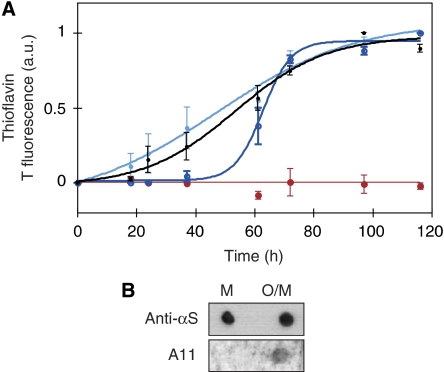

A mixture of oligomeric and monomeric TP αS, which was obtained after five days of aggregation of TP αS at 37°C and 0.2 mM protein concentration, was able to seed fibril formation of monomeric wt αS (Figure 2A). In contrast, addition of the same concentration of purely monomeric TP αS did not accelerate aggregation of wt αS. In addition, the mixture of oligomeric and monomeric TP αS was recognized by the conformation-specific antibody A11 (Figure 2B), which detects a variety of toxic amyloid oligomers (Kayed et al, 2003). It should be noted that the TP oligomers were not resistant to SDS (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Aggregates formed by TP αS seed aggregation of wt αS. (A) Pre-fibrillar aggregates of TP αS seed fibril formation of wt αS. In an equimolar mixture of pre-aggregated TP αS with monomeric wt αS the lag time of aggregation is decreased (light blue) when compared with wt monomer alone (black). In contrast, in an equimolar mixture of monomeric TP αS and monomeric wt protein the lag time is increased (dark blue). Aggregation behaviour of monomeric TP αS alone is shown in red. Error bars represent mean±s.d. of three to four independent experiments. (B) Recognition of a mixture of oligomers and monomers of TP αS (O/M) but not monomeric TP αS (M) on nitrocellulose membrane by the A11 antibody. Anti-αS antibody shows comparable attachment to both monomer and oligomer.

Increasing the concentration to 0.8 mM significantly accelerated the rate and amount of aggregation, and amyloid formation of all αS variants (Figure 1D). At 0.8-mM protein concentration, wt and A30P αS had a distinct lag phase of about 9–12 h, whereas ThT reactivity of A53T rose from the beginning (inset in Figure 1D). However, A56P started to form ThioT-positive fibrils after about 72 h and TP αS showed a clear but very slow rising ThioT signal only after about 5 days of incubation (Figure 1D). Surprisingly, the strongest ThioT signal after 5 days of incubation was observed for A30P αS, followed by wt and A53T αS. This is most probably caused by the very gel-like behaviour of the aggregated wt, A30P and in particular A53T αS samples that interfered with ThioT binding. The samples of A56P and TP αS were much more fluid, indicating that a smaller amount of fibrils was formed. In addition, A56P and TP αS had strongly reduced fibril elongation rates. Although for wt, A30P and A53T αS it took about 20 h to reach the saturating ThioT signal from end of the lag phase, this time was increased to about 60 h in case of A56P αS. With TP αS a saturating ThioT signal could not be reached within the experimental time, indicating that it has an extremely slow fibril elongation rate (Figure 1D).

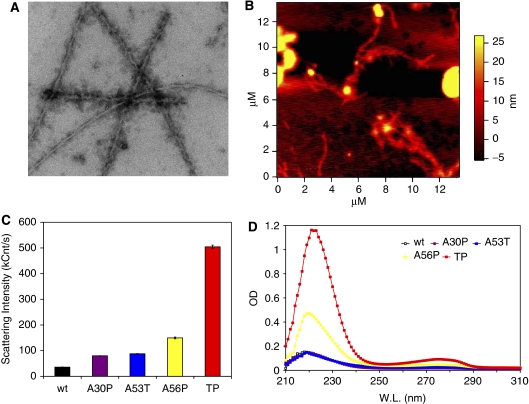

Electron microscopy of wt, A30P, A53T and A56P αS samples after 6 days of incubation (protein concentration of 0.8 mM) revealed a high number of fibrils of about 8 nm in diameter and various lengths but without clearly observable oligomeric species. In case of TP αS, the fibrils were significantly lower in number, longer and frequently associated with oligomers of various shapes and sizes (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure S2). Atomic force microscopy of the TP αS sample showed a similar picture, with the presence of fibrils of about 8 nm in diameter and oligomers of 20–100 nm in diameter (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Enhanced formation of soluble oligomers by αS variants. (A) Electron micrograph of TP αS solution in 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl (pH 7.4), 0.01% NaN3, incubated for 6 days at 37°C while being stirred at 200 r.p.m. The protein concentration was 0.8 mM, and the sample was diluted eightfold by buffer before EM imaging. (B) AFM image of TP αS solution. Conditions identical to (A). (C) Dynamic light scattering of αS variants, incubated for 11 days at the aggregation condition and then centrifuged briefly followed by the measurement of the supernatant. Data presented are average of three measurements, each consisting of 20 acquisitions of 20 s. (D) UV absorbance of the supernatant of aggregated αS variants after 11 days of incubation at the aggregation condition.

αS variants have an increased propensity to form oligomers

The aggregation process of the αS variants was further investigated by dynamic light scattering and electron microscopy. Dynamic light scattering revealed the formation of soluble oligomers with a hydrodynamic radius of approximately 80–180 nm after six hours of incubation in the aggregation assay using protein concentrations of 0.1 mM (Supplementary Figure S3). In the same assay, a heterogeneous distribution of larger species was observed through electron microscopy for all αS variants after 12 h of incubation (Supplementary Figure S3).

In addition, DLS was used to study the soluble oligomers of αS, which were formed after 11 days of incubation. At protein concentrations of 0.8 mM, fibrils were observed for all αS variants (see above and Figure 3A). The fibrillar material was separated from soluble oligomers by centrifugation at 14 000 g for 30 min and careful pipetting of the upper 50% of the supernatant. DLS measurements of the supernatant samples showed quite different scattering patterns for the different αS variants. The smallest scattering intensity was observed for wt αS (Figure 3C). A30P and A53T αS had very similar scattering intensities, which were slightly larger than those of wt αS, and for A56P αS the scattering intensity was further increased. The most marked increase, however, was seen for TP αS, for which the scattering intensity of the supernatant sample was an order of magnitude higher than in case of the wt protein (Figure 3C), and mostly caused by 140–170 nm oligomeric species. The UV absorbance spectrum of the supernatant showed a very similar trend for the αS variants (Figure 3D). The combined EM, AFM, DLS and UV data indicate that A56P and, in particular, TP αS have an impaired ability to form amyloid fibrils, but soluble oligomers accumulate in later stages of the aggregation.

Aggregates formed by αS variants have impaired β-structure

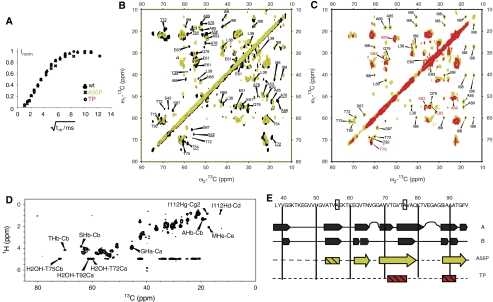

The late-stage aggregates of A56P and TP αS were characterized at single residue resolution through solid-state NMR (ssNMR) spectroscopy (Figure 4). For both A56P and TP αS, magnetization transfer from water to the protein proceeded at the same rate, suggesting that the relative water-accessible surface in these fibrils was similar to that of fibrils from wt protein (Figure 4A). Following a theoretical analysis, given in (Ader et al, 2009), and assuming a cylindrical (proto)fibril model, we estimated fibril diameters of about 60 Å for all three cases. However, cross peak signals in sequential (13C,13C) correlation experiments conducted on A56P αS were absent around the mutation site (e.g. Y39, S42, T54 and A56) but were identified for the other three β-strand segments previously detected for the wt, A30P and A53T protein (Heise et al, 2005, 2008; Zhou et al, 2006) (Figure 4B). In addition, we detected alterations in chemical shifts for several residues, including T75, Q79, I88 and E83, indicative of a perturbed β-strand structure. These findings point to a reduced β-sheet content in late-stage aggregates of A56P αS compared with wt, A30P and A53T αS. Concomitantly, we detected, in ssNMR experiments probing mobile A56P fibril segments, an enhanced contribution from residue types such as threonine, which are found in the residue stretch 22–93 (Figure 4D). For TP αS, a further significant reduction of cross-peak correlations was detected (Figure 4C) under experimental conditions comparable with A56P, consistent with structural alterations or increased dynamics/disorder in the last two β-strands (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

High-resolution solid-state NMR of late stage aggregates formed by αS variants. (A) Water accessibility of aggregates as probed by solid-state NMR. A 3-ms Gaussian pulse and a T2 filter containing two delays of 1 ms were used for selective water excitation (Ader et al, 2009). The cross polarization contact time was set to 700 μs. (B) Superposition of 2D 13C/13C correlation spectra of U-[13C,15N] A56P αS (yellow) and of wt αS (black). Correlations absent in the A56P mutant are underlined. Assignments correspond to values obtained for the A form of wt αS as reported in (Heise et al, 2005). (C) Superposition of 2D 13C/13C correlation spectra of U-[13C,15N] A56P αS (yellow) and of U-[13C,15N] TP αS (red). In (B) and (C), homonuclear mixing was achieved using a proton driven spin diffusion time of 20 ms (A56P) and 50 ms (TP), respectively. (D) 2D 1H/13C 1H-T2-filtered HETCOR spectrum of A56P αS. The spectrum was recorded at a magnetic field strength of 14 T, with a spinning speed of 8.33 kHz, at a sample temperature of 0°C. The T2 filter delay was 2 × 175 μs, the contact time was 3 ms. The spectrum was recorded without homonuclear decoupling during t1, 160 t1 increments and 128 scans per slice. (E) ssNMR-based secondary structure analysis for wt and mutant αS. Row 1 and 2 correspond to wt data reported previously (Heise et al, 2005). Hatched rectangles relate to protein regions in which β-strands are lost compared with wt αS or, in the case of TP, show strong dynamics/disorder. Arrows relate to β-strands that are preserved in A56P. Mutation sites are indicated by rectangular boxes, suggesting that A↔P mutation leads to partial (A56P) or almost complete (TP) suppression of β-strand formation in αS.

Membrane binding characteristics of αS variants

In aqueous solution, αS is predominantly unfolded but readily associates with small unilamellar vesicles (SUV) and micelles containing negatively charged lipids and detergents, respectively (George et al, 1995; Eliezer et al, 2001), supporting its association with presynaptic vesicles in vivo and rationalizing its localization primarily at axon termini (Iwai et al, 1995; Jensen et al, 1998). Liquid-state NMR and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy indicated that the point mutations did not markedly alter the structural properties of the protein as monomer in solution, or prohibit the formation of an α-helical conformation on the surface of SDS micelles (Supplementary Figures S4–S6). Next we quantified the amount of αS bound to SUVs, which were formed by a 1:1 mixture of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidyl choline (POPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidic acid (POPA). Gel filtration of αS-SUV mixtures (phospholipid to protein mass ratio of 250:1) revealed that more than 95% of wt and A53T αS are bound to SUVs when using Tris buffer (Table I and Supplementary Figure S7). In the case of A30P αS, only 70±3% of the total protein was bound to POPC–POPA SUVs, in agreement with its reduced affinity for membranes (Jensen et al, 1998). A value very similar to that observed for A30P was obtained for A56P αS. In addition, the affinity of TP αS was only very slightly reduced compared with A30P and A56P αS, with 66±3% of SUV-bound protein (Table I). When phosphate buffer was used instead of Tris, the overall amount of SUV-bound αS was reduced, but relative differences between different αS variants were very similar (A53≈wt>A56P≈A30P⩾TP) (Table I). In addition, the content of α-helix, which was detected by CD spectroscopy for the αS variants in the SUV-bound state, followed the amount of SUV-bound protein (wt≈A53>A56P≈A30P⩾TP) (Supplementary Figure S8 and Table S1).

Table 1.

Binding of αS variants to phospholipid vesicles

| Sample (POPC/POPA 1:1) | SUV binding (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer 1 | Buffer 2 | |

| WT | 95 | 60 |

| A30P | 70 | 44 |

| A53T | 98 | 70 |

| A56P | 72 | 50 |

| TP | 66 | 37 |

| Buffer 1 (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl) and buffer 2 (50 mM Na-phosphate (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl) were used for the experiments. On incubation with SUVs, the free protein peak decreased and the SUV peak increased indicating the interaction of the protein with the phospholipid vesicles. For quantification of bound αS, the peak volume (detected by UV at 280 nm) at the elution position of free synuclein was integrated and compared with the corresponding peak volume obtained in the absence of SUV. | ||

Structure-based design variants of αS impair aggregation in vivo

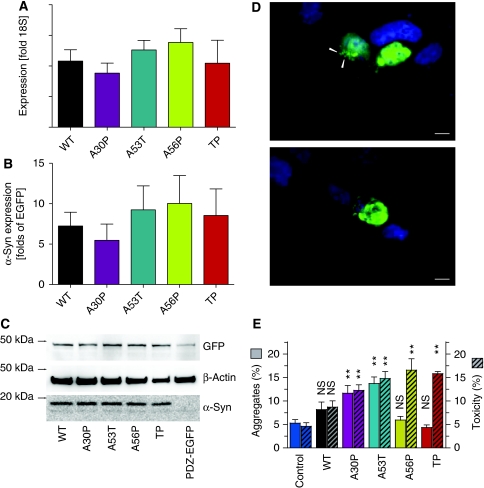

To test the in vivo aggregation properties of the αS variants, we expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells wt, A30P, A53T, A56P and TP αS labelled at the C-terminus with a six amino-acid PDZ-binding motif (Opazo et al, 2008). Equal expression levels of all αS variants were verified by quantitative PCR and western blot (Figure 5). A second, independent cassette expressed a fusion protein of EGFP and the corresponding PDZ domain (PDZ-EGFP), thus non-covalently labelling αS variants with EGFP. We classified cells based on their EGFP fluorescence to determine the frequency of cells with aggregates and the fraction of preapoptotic cells (see Materials and methods). Significantly more cells transfected with A30P or A53T αS formed aggregates (as visualized by EGFP fluorescence) as compared with cells expressing the control protein PDZ-EGFP alone (Figure 5E). In contrast, expression of the design mutants A56P and TP αS did not induce aggregates in more cells than background (EGFP-PDZ alone). Thus, A56P and TP αS fulfilled their design principle, that is, they show strongly impaired aggregation both in vitro and in living cells.

Figure 5.

Aggregate formation and toxicity in HEK293T cells. (A) RT–PCR quantification of αS mRNA extracted 24 h after transfection. Bars represent αS mRNA relative to the ribosomal 18S subunit mRNA. (mean±s.e.m., n=3 independent experiments, no significant difference between different αS variants) (B) Quantification of the western blot bands (exemplified in C) no significant difference between the different αS variants (mean±s.e.m., n=3 independent experiments). (C) Western blot of transfected (24 h) HEK293T cells. αS including the PDZ binding domain has a molecular weight close to 19 kDa, PDZ domain fused to EGFP has a predicted molecular weight of 46 kDa and β-actin is close to 42 kDa. (D) Representative images of aggregates (top panel, arrowheads) and pre-apoptotic cell (lower panel). Scale bar is 10 μm. (E) Cells with more than one aggregate (‘aggregates', left axis, clear bars) and pre-apoptotic cells (‘toxicity', right axis, hatched bars) were counted 24 h after transfection. Bars represent percentages of all EGFP-positive cells (mean±s.e.m., n=5 independent experiments). Significances are depicted with respect to Ctrl (PDZ-EGFP alone): NS, not significant; **P<0.01, One-way ANOVA and Dunnet's post hoc test.

In agreement with a previous study (Opazo et al, 2008), expression of the genetic mutants, A30P and A53T αS, resulted in more cells with aggregates and a higher fraction of preapototic cells than control. (Figure 5E). In contrast, expression of A56P and TP αS resulted in toxicity comparable with that observed for A53T αS, despite the observation that the occurrence of aggregates was at background levels (PDZ-EGFP alone). From the induction of toxicity, but not aggregates, by the design mutants, A56P and TP, αS we conclude that cellular toxicity in response to αS expression does not require the formation of visible αS aggregates, i.e. fibrils. However, differences in toxicity between A56P and TP αS that are related to aggregation cannot be revealed in this system, as already the single A56P mutation had a dominant effect on aggregation.

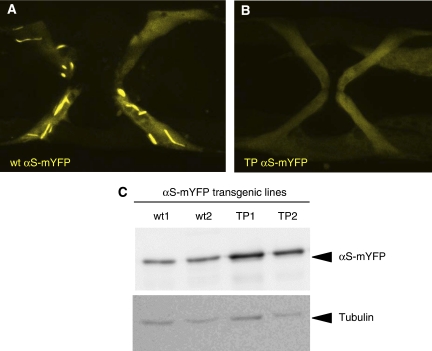

When expressed in muscle cells of C. elegans, wt αS had been shown to form aggregates in an age-dependent manner (Hamamichi et al, 2008; van Ham et al, 2008). To show that the TP variant of αS has a strongly impaired ability to form insoluble aggregates in vivo—as has been shown in vitro—we expressed wt and TP αS as a fusion to monomeric YFP in body wall and sex muscles of C. elegans, and followed its aggregation with time. As reported previously, aggregates of wt αS-mYFP are first detected in 6-day-old adult muscles and at day-10 large fibrillar aggregates were visible in most muscles (86% and 75% in 25 animals analysed in each of two independent stains, respectively) (Figure 6A). In contrast, at day six no TP αS-mYFP aggregates could be detected in any of the transgenic strains and even at day 10 only rare, small TP αS-mYFP aggregates were visible in a few muscle cells (4% and 8% in 26 animals analysed in each of two independent stains, respectively) (Figure 6B). The αS-mYFP expression levels were comparable as judged by western blot analysis and even slightly higher for the TP strains used (Figure 6C). Therefore, we conclude that, like in vitro, the TP mutations strongly impair fibril formation of αS in vivo.

Figure 6.

TP αS shows reduced aggregation propensity in C. elegans. Ten-day old vulva muscles are show from transgenic animals expressing either (A) wt αS or (B) TP αS fused to mYFP. Only wt αS-mYFP leads to extensive fibrillar aggregates, whereas TP αS-mYFP remains diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm. The width of the area shown in (A) is 80 microns. (C) The expression levels of the αS-mYFP fusion proteins are similar as shown by western blot using anti αS antibodies. Tubulin staining serves as a loading control.

Expression of pre-fibrillar αS mutants causes increased neurotoxicity in worms, flies and mammalian neurons

Next we overexpressed αS mutants in three established model systems for PD: mammalian neurons (Zhou et al, 2000), the nematode C. elegans (Nass and Blakely, 2003) and the fly Drosophila melanogaster (Feany and Bender, 2000). In Drosophila, the transgenes of the different αS variants were targeted to the same genomic location by using the φ-C31-based site-specific recombination system (Supplementary Figure S9) (Bischof et al, 2007). Expression levels of all aS variants in a specific model system were comparable (Figures 5, 6 and Supplementary Figure S10).

In rat primary cortical neurons transduced with adeno-associated-virus (AAV)(Kugler et al, 2007), expression of A53T, A56P and TP αS resulted in a lower mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity and a reduced number of surviving neurons than wt and A30P αS, and control neurons expressing EGFP (Figure 7A). Similarly, in primary midbrain cultures, the number of dopaminergic neurons was decreasing in the order EGFP≈wt≈A30P>A53T∼A56P>TP (Figure 7A). Immunohistochemical detection specifically of AAV-expressed human αS and variants showed identical subcellular distribution of all variants: the proteins were found to be evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm, and within neurites showed a granular staining pattern, according to a presumed localization on vesicular structures (Supplementary Figure S11).

Figure 7.

Neurotoxicity of structure-based design mutants of αS in mammalian neurons, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila. (A) Structure-based design variants in rat primary neurons. Left panel: WST assay of cortical neurons transduced by AAV-EGFP, AAV-αS-wt, AAV-αS-A30P, AAV-αS-A53T, AAV-αS-A56P and AAV-αS-TP, respectively. Mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity measured after transduction with respective αS mutants is shown as percentage of activity measured after AAV-EGFP transduction (n=30). Middle panel: Neuronal cell loss quantified by NeuN immunocytochemistry. Numbers of NeuN immunoreactive cells counted after transduction with respective αS mutants is shown as percentage of numbers counted after AAV-EGFP transduction (n=15). Right panel: Degeneration of dopaminergic midbrain neurons quantified by TH immunocytochemistry. Numbers of TH immunoreactive cells counted after transduction with respective αS mutants is shown as percentage of numbers counted after AAV-EGFP transduction (n=12). Data are shown as mean±s.e.m. In all cases, the significance was determined by one-way ANOVA analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's post hoc test *P<0.05; **P<0.01. (B) C. elegans expressing red fluorescent protein mCherry and wt αS (upper left panel) or TP αS (lower left panel) in the cephalic (CEP) and anterior deirid (ADE) dopaminergic neurons in the head. Right panel: degeneration of dendritic processes induced by expression of αS in dopaminergic neurons. Two independent transgenic lines are shown per αS variant and 78–80 animals we analysed per line. The error bar correspond to the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) and the significance values of the ANOVA test are indicated: *P<0.05; ***P<0.001. (C) Whole-mount immunostaining of fly brains. Images are maximum projections of several confocal sections in the z-plane. (D) Quantitative analysis of dopaminergic neuron numbers in the dorsomedial (DM) and dorsolateral (DL) cluster in brains of 2-day- (young) and 29-day-old (adult) flies. The error bars correspond to s.e.m. and the significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison post hoc test; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; NS P>0.05. Values represent mean±s.e.m. Asterisks indicate that the difference in dopaminergic neuron numbers was statistically significant. For 2-day-old flies, no statistically significant difference was observed in numbers of dopaminergic neurons. Expression levels of different aS variants were comparable (Supplementary Figures S9 and S10).

In C. elegans, the eight dopaminergic neurons are clearly visible and morphologically invariant from animal to animal, enabling reliable scoring of morphological defects (Nass and Blakely, 2003; Cooper et al, 2006). To assay αS induced neuronal toxicity, transgenic strains were generated expressing the different αS variants exclusively in dopaminergic neurons of C. elegans. As these neurons are dispensable and are not required for viability, their αS induced degeneration can be studied without affecting the animal's fitness. For each expressed αS variant, the morphology of dopaminergic neurons was analysed in the head of several independent transgenic strains. Two representative lines each are shown in Figure 7B. Transgenic strains overexpressing the genetic mutants A30P (45±5% and 42±4%) and A53T (36±6% and 48±5%) αS developed more neurite defects than control animals expressing wt αS (13±5% and 8±3%) consistent with previous results (Figure 7B) (Cooper et al, 2006; Kuwahara et al, 2006). More pronounced neurodegeneration, however, was observed for C. elegans strains expressing the designed αS variants A56P (63±3% and 68±3%) and TP (88±2% and 81±3%) (Figure 7B). The αS expression levels were similar in all strains studied as shown by western blot analysis using an αS-specific antibody (Supplementary Figure S10). However, the degeneration was not restricted to dopaminergic neurons. When αS was expressed under the control of a pan-neuronal promoter, degeneration of other neurons was visible leading to sick animals (data not shown).

To assess the impact of the αS variants on dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila, we immunostained whole-mount brains from flies at day 2 and 29 posteclosion using an antibody against tyrosine hydroxylase, which specifically identifies these neurons (Figure 7C). In young flies overexpressing wt, A53T, A56P and TP αS under control of the pan-neuronal driver elav-Gal4, the number of neurons in the dorsomedial (DM) and dorsolateral (DL) cluster of the brain was not altered when compared with the LacZ control (Figure 7D). At day 29, however, adult flies expressing A53T and A56P αS showed a marked loss of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive cells in both clusters (Figure 7D). An even more pronounced reduction in the number of dopaminergic neurons was observed in flies expressing TP αS, particularly in the DM cluster (Figure 7C and D). Taken together the data show that overexpression of αS variants, which delay fibril formation, but allow oligomer formation, causes increased neurotoxicity in three established model systems for PD: increasing impairment to form fibrils is consistently correlated with increasing neurodegeneration (wt∼A30P<A56P<TP). The genetic mutant A53T αS has a neurotoxicity comparable with that of A56P αS in the three model systems, but does not allow a conclusion about the importance of a certain aggregate species for neurotoxicity as A53T αS forms both oligomers and amyloid fibrils more rapidly.

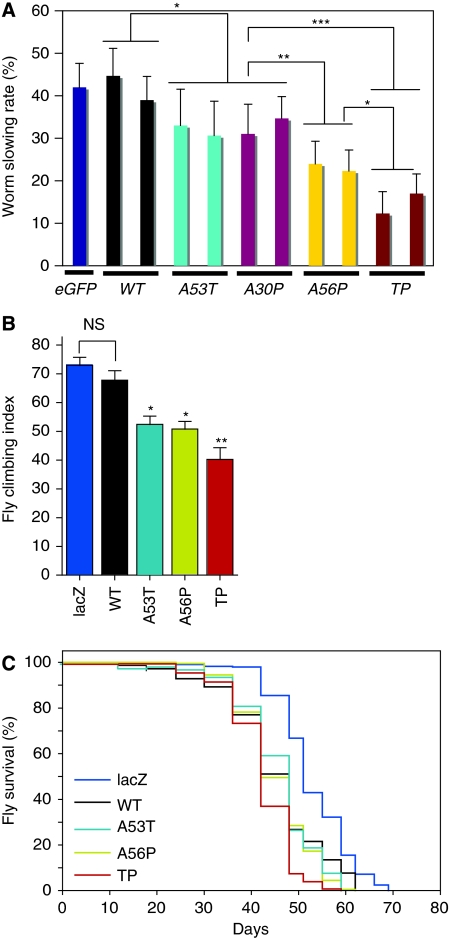

Expression of pre-fibrillar αS mutants impair dopamine-related behaviour in worms and flies

To explore whether the observed differences in αS aggregate formation and structure are relevant for the functioning of dopaminergic neurons in living organisms, we tested the impact of the structure-based design mutants of αS on dopamine-related behaviour (Feany and Bender, 2000; Lakso et al, 2003). In response to the presence of food, C. elegans worms slow down and reduce their area-restricted searching behaviour. This behaviour depends on dopaminergic neurotransmission and is absent when dopaminergic neurons are ablated or not functional. Transgenic worms expressing the A56P or TP αS variant in dopaminergic neurons are more impaired in this dopamine-dependent behaviour than worms expressing wt αS or the genetic variants (A30P and A53T) (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Structure-based design mutants of αS cause behavioural defects in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila. (A) ‘Basal slowing response' of C. elegans expressing different αS variants in dopaminergic neurons. For each αS variant expressed, at least, two independent transgenic lines were tested (n=40–50 animals per trail, 3 trails). The slowing rate corresponds to the average decrease in movement (body bends per min) for animals placed in food as compared with animals without food. Animals expressing only EGFP in dopaminergic neurons are shown as control. The error bar corresponds to s.e.m. and the significance values of the ANOVA test are indicated: *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. (B) Climbing assay on flies with corresponding genotypes. Climbing index, percentage of 25–30-day-old flies that could reach the top chamber in a fixed amount of time (n=35–50 for each group). (C) Survival curves of flies expressing different variants of αS and LacZ. A56P αS and TP αS curves are significantly different from wt αS (logrank test: P<0.0217 for wt αS versus A56P αS, and P<0.0001 for wt αS and TP αS. n=350–400 for each genotype).

In Drosophila using the pan-neuronal driver elav-Gal4, we assayed for motor defects using a climbing assay that addresses the combined geotactic and phototactic response of flies. The loss of the climbing response has been used to monitor aging-related changes in Drosophila (Ganetzky and Flanagan, 1978) and to reveal behavioural manifestations of nervous system dysfunction in αS transgenic flies (Feany and Bender, 2000). The climbing abilities of 25–30 day old flies expressing wt αS (or A30P αS according to initial tests) were comparable with those of the LacZ control flies (Figure 8B). In contrast, flies expressing the genetic mutant A53T αS, or the aggregation-impaired design mutant A56P αS showed a reduced climbing ability. In agreement with the lowest number of dopaminergic neurons (Figure 7D), adult flies expressing TP αS were most strongly impaired (Figure 8B). Moreover, flies expressing the structure-based αS variants (in particular TP αS) under the control of the ddc-GAL4 driver showed a reduced life span (Figure 8C).

Discussion

A better understanding of the relationship between the process of αS amyloid formation and disease progression in animal models for PD is essential for understanding the molecular basis of neurodegeneration and the development of effective therapeutic strategies to prevent and treat PD, and other synucleinopathies. We presented a structure-based rational design of αS mutants and their biophysical properties in vitro. The results establish that αS mutants that cause reduced fibrillization and β-structure formation, and lead to the formation of increased amounts of soluble oligomers can be predicted. We show that differences in the biophysical properties of these mutants translate into ‘predictable' changes in neuronal toxicity and behavioural defects in neuronal cell cultures and animal models of synucleinopathies. The structure-based design mutants provide unique tools to dissect the relative contribution of oligomers and fibrils to αS toxicity and establish the relationship between biophysical properties of multimeric αS species and their function in different in vivo models.

The rational design of the αS variants was based on the flexibility of the αS backbone in the monomeric state and the location of β-strands in amyloid fibrils (Bertoncini et al, 2005; Heise et al, 2005; Vilar et al, 2008). The genetic mutation A30P is located in a domain that is statically disordered and not a part of the core of amyloid fibrils of αS. We carried the alanine-to-proline replacement right into the centre of the β-strands of αS amyloid fibrils (Figure 1A). In agreement with the design principle, even the single point mutation, A56P, strongly reduced the aggregation of αS both in vitro (Figure 1) and in living cells (Figure 5). Assuming that only marked differences in the rate of aggregation in vitro can be reliably transferred to the in vivo situation, the A56P mutation was complemented by the triple proline A30P/A56P/A76P mutation, which shows impaired formation of insoluble aggregates in vitro (Figure 1) and in vivo (Figure 6). At the same time, however, both A56P and A30P/A56P/A76P αS variant showed a strongly increased propensity for forming soluble oligomers (Figure 3). In combination with wt αS, the two structure-based design mutants allowed a detailed study of the relationship between oligomerization, fibril formation and neurotoxicity in animal models for PD.

The genetic mutant A30P is often taken as support for the hypothesis that it is not the insoluble aggregates that comprise the most neurotoxic species, but rather soluble oligomers. This idea is based on the finding that under certain conditions A30P αS forms more protofibrils, but less fibrils, than wt αS (Conway et al, 2000). However, conflicting studies reported the aggregation rates of A30P αS as unchanged, increased or decreased (Narhi et al, 1999; Conway et al, 2000; Tabrizi et al, 2000; Hoyer et al, 2002). In addition, the genetic mutant E46K αS is less able to form preamyloid oligomers than wt αS (Fredenburg et al, 2007). The best support for an important role of aggregation intermediates of αS in PD comes from a study that investigated the effect of phosphorylation at S129 of αS in transgenic flies. Preventing phosphorylation by mutation of S129 into alanine reduced neurotoxicity, whereas increasing the number of large inclusion bodies (Chen and Feany, 2005). However, no differences in the fibrillization rates of wt, S129A and S129D αS were observed in the same study in vitro (Chen and Feany, 2005). Moreover, S129 is located in the highly acidic C-terminal domain of αS that remains highly flexible even in amyloid fibrils, making it difficult to understand the molecular mechanism of decreased neurotoxicity and increased inclusion body formation observed for S129A αS in transgenic flies. In another study in transgenic flies, C-terminally truncated αS (αS1−120) increased the number of αS immunoreactive insoluble inclusions, but enhanced neurotoxicity (Periquet et al, 2007), further highlighting the complex relationship between aggregation of αS and PD-related neurotoxicity.

HEK cells, rat primary neurons, C. elegans and Drosophila that overexpress αS are established models for PD (Feany and Bender, 2000; Zhou et al, 2000; Nass and Blakely, 2003; Opazo et al, 2008). Here we overexpressed the wt protein, the genetic mutants A30P and A53T and the two structure-based design mutants A56P and TP αS in all four of these model systems. The simultaneous use of four model systems was motivated by previous reports that overexpression of wt, genetic mutants and phosphorylation mimics of αS induced different degrees of toxicity in different PD model systems (Feany and Bender, 2000; Masliah et al, 2000; Outeiro and Lindquist, 2003; Chen and Feany, 2005; Periquet et al, 2007; Volles and Lansbury, 2007; Gorbatyuk et al, 2008). In contrast, expression of the structure-based design variants A56P and TP αS caused increased neurotoxicity in all four model systems: increasing the impairment to form fibrils was consistently correlated with increasing neurodegeneration (wt∼A30P<A56P<TP) (Figures 7 and 8). This provides strong evidence for the importance of soluble oligomers as the most toxic species in PD. In agreement with the importance of soluble oligomers for neurodegeneration, other studies have suggested that aggregation intermediates are the pathologically relevant species in Alzheimer and Huntington disease (Saudou et al, 1998; Lesne et al, 2006).

A mutational strategy as used in our study allows correlations between biophysical properties observed for the mutated proteins in vitro and functional deficits observed in vivo. In agreement with the design principle, the most marked effect observed for the structure-based design variants of αS was their impaired fibrillation but strongly enhanced formation of soluble oligomers (see below). At the same time, however, we cannot exclude that some other property of αS was changed that is important for neurotoxicity in vivo. This is even more difficult to evaluate as the physiological function of αS is—although several suggestions have been made—still unknown. To minimize this possibility, we carried out alanine-to-proline substitutions as found in the A30P genetic mutant of αS. Importantly, both genetic mutation, A30P, and design substitution, A56P, are located in the N-terminal domain of αS that converts into α-helical structure upon binding to model membranes (Eliezer et al, 2001). In agreement with this design principle, our studies showed that the A56P variant of αS has an affinity for phospholipid vesicles that is comparable and even slightly higher than A30P αS (Table I). Even for the triple-proline variant TP αS, an only slightly reduced vesicle-affinity (compared with A30P αS) was observed, suggesting that the αS variants are flexible enough to efficiently bind to phospholipid vesicles. Despite the very similar vesicle affinities, however, only the A56P and A30P/A56P/A76P variant of αS showed strongly increased neurotoxicity, consistent with their higher propensity to form soluble oligomers.

It is known that αS interacts with many proteins and possesses chaperone function (Ostrerova et al, 1999; Norris et al, 2004), and that mutations might influence these interactions. However, it is unlikely that such changes are responsible for the increased neurotoxicity observed for the A56P and A30P/A56P/A76P variant, as deletion of residues 71–82 of αS prevented toxicity in transgenic flies (Periquet et al, 2007): the 71–82 deletion mutant of αS completely abolished the formation of oligomers and fibrils in vitro and in vivo, indicating that monomeric αS is not toxic (Periquet et al, 2007).

The hallmark of amyloid fibrils is the formation of rigid β-structure (Sunde and Blake, 1997). Much less is known about the structure and dynamics of aggregation intermediates (Lashuel and Lansbury, 2006). Oligomeric species generated in vitro by a variety of proteins associated with neurodegenerative disease appear as spherical, annular, pore-like, tube-like and chain-like structures in electron micrographs (Lashuel and Lansbury, 2006). High-resolution structural data are, however, extremely limited because of the transient and heterogeneous nature of soluble oligomers. Even more, the relationship between structural properties of preamyloid oligomers and neurotoxicity is unknown. Solid-state NMR on an amyloid intermediate of the β-amyloid peptide involved in Alzheimer's disease indicated that late-stage aggregation intermediates and fibrils share a common parallel β-sheet structural motif (Chimon et al, 2007). Moreover, different fibril morphologies of β-amyloid peptide have been correlated with different toxicities in neuronal cell cultures (Petkova et al, 2005). Computational studies suggested that neurotoxicity might be related to the highest surface-to-volume ratio and exposure of hydrophobic residues in the aggregates (Cheon et al, 2007). Our solid-state NMR data of late-stage aggregates of A56P and TP αS showed that their morphology is similar to amyloid fibrils of wt αS, however, the molecular level structure is strongly changed. A markedly diminished β-sheet rich core was observed (Figure 4), which suggests that soluble oligomers formed by the structure-based design variants might also have a reduced ability to adopt β-structure. Importantly, neurotoxicity of variants of αS (wt∼A30P<A56P<TP αS) in the four model systems for PD was inversely correlated with the amount of β-structure detected in insoluble αS aggregates (wt∼A30P>A56P>TP αS) (Figures 5 and 7). Thus formation of rigid β-structure might not to be as important for neurotoxicity as previously thought.

In conclusion, our combined biophysical and in vivo data revealed a strong correlation between the enhanced formation of soluble oligomers and lack of β-sheet content in fibrils of αS variants, and neurotoxicity, the strength of PD-related behavioural effects and survival in four model systems for PD. This provides strong evidence that structurally less stable aggregation intermediates of αS are key players in the pathogenesis and progression of PD and other neurodegenerative disorders collectively referred to as synucleinopathies. The ability to engineer mutants that promote and stabilize specific toxic intermediates is essential not only for understanding the structural basis of αS toxicity, but also for developing diagnostic tools and imaging agents.

Materials and methods

Cloning, expression and purification of αS variants

pT7-7 plasmid encoding human wt αS was kindly provided by the Lansbury Laboratory, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA. A codon replacement was carried out for residue Y136 (TAC to TAT) for codon usage concerns (Masuda et al, 2006). Mutations were carried out by using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and verified by DNA sequencing. Protein expression and purification were carried out as previously described with minor changes (Hoyer et al, 2002).

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy

For solid-state NMR measurements, 200 μM 13C- and 15N-labelled A56P αS was incubated for two weeks, and 200 μM 13C- and 15N-labelled TP αS was incubated for four weeks at 37°C and 200 r.p.m. Subsequently, αS aggregates were recovered by centrifugation at 60 000 g for 2 h at 4°C (TLA.100, Beckman ultracentrifuge).

Two-dimensional NMR experiments were conducted on 14.1 T (1H resonance frequency: 600 MHz) and 18.8 T (1H resonance frequency: 800 MHz) NMR instruments (Bruker Biospin, Germany) equipped with 4-mm triple-resonance (1H, 13C, 15N) MAS probes. All experiments were carried out at probe temperatures of 0°C. MAS rates were set to values that facilitate sequential correlations at longer mixing times, that is, 9375 Hz at 600 MHz and 12500 Hz at 800 MHz (Seidel et al, 2004). Resonance assignments for A56P αS and a residue-specific analysis of β-strands in αS variants was based on sequential (13C–13C) correlation data obtained at mixing times of 150 ms (data not shown). High-power proton-decoupling using the sequence SPINAL64 (Fung et al, 2000) with r.f. amplitudes of 80–90 kHz was applied during evolution and detection periods.

Experiments with HEK293 cells

Cell culture and transfection. HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's MEM (PAN-Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany) with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Cells were transiently transfected using metafectene (Biontex Laboratories, Martinsried, Germany), following the manufacturer instructions.

Imaging. For imaging, cells were grown on poly-L-lysine (Sigma, Munich, Germany) coated glass coverslips and used 24 h after transfection. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides using mounting medium consisting of 24% w/v glycerol, 0.1 M Tris base (pH 8.5), 9.6% w/v Mowiol 4.88 (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) and 2.5% w/v DABCO (Sigma). Imaging at 24 h was carried out at room temperature using an inverted fluorescence microscope (DMI6000B, Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany) with a × 63 dry objective (HCX PL FLUOTAR, N.A. 0.7) and a Leica FX350 camera.

EGFP distribution patterns. To visualize αS variants in living cells, we have recently established and validated a method that labels αS variants with EGFP through the specific interaction between a PDZ binding motif and its PDZ domain (Opazo et al, 2008). The advantage of this method is that only a six-amino-acid PDZ-binding motif is added to the αS C-terminus and not the entire EGFP protein. In our hands, the appearance of cells transfected with the same construct varied greatly, making it difficult to determine a ‘typical' appearance and compare αS variants based on this. We therefore chose to manually classify cells into four broad groups: ‘homogenous', ‘with a single aggresome', ‘with many aggregates' or ‘preapoptotic', and compare the relative frequencies of these appearances. Using this approach, we have previously investigated the differences between wt, A30P, A53T, a C-terminally deleted αS, the effects of HSP70 co-expression, inhibition of proteasome, autophagy and lysosomal degradation (Opazo et al, 2008). Preapoptotic cells are characterized by rounding and contained large, amorphous aggregates of EGFP. Imaging showed that they had lost stress fibres and focal adhesions, but maintained membrane integrity. Time-lapse imaging showed that this appearance was followed by the formation of apoptotic bodies (Opazo et al, 2008). Cells ‘with a single aggresome' contained one clearly visible, round aggregate of EGFP but appeared otherwise healthy. Staining showed a basket of vimentin and γ-tubulin around the aggregate, characterizing it as an aggresome. Time-lapse imaging showed that small, peripheral aggregates were often transported towards the aggresome (Opazo et al, 2008).

For each αS variant, and for PDZ-EGFP alone (Ctrl.), 200–300 cells per coverslip from 4–5 independent experiments were classified manually. For statistical analysis, One-way ANOVA was carried out using GraphPad Prism 4.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). P-values were derived from Dunnett's post-tests. All comparisons were made against the control PDZ-EGFP alone. Bars depicted in the graphs represent mean±s.e.m.

C. elegans

Expression constructs. To express αS in dopaminergic neurons a 719-bp dat-1 promoter fragment was PCR amplified as described previously (Kuwahara et al, 2006) and cloned upstream of the start ATG of EGFP in the C. elegans expression vector pPD115.62 (myo-3::gfp; kindly provided by A. Fire), replacing the myo-3 promoter creating Pdat-1::gfp. Subsequently αS and its mutant variant were also PCR amplified and cloned as an NdeI/HindIII fragment into the Pdat-1::gfp vector replacing gfp. To create Pdat-1::mCherry, the gfp coding sequence of Pdat-1::gfp was exchanged with that of the red fluorescent protein variant mCherry. To analyse aggregation of αS-mYFP, citrine fusion proteins were specifically expressed in muscle cells under the control of the myo-3 promoter of pPD115.62. Wt and TP αS were PCR amplified without stop codon for C-terminal fusion and cloned along with mYFP citrine into pPD115.62 replacing GFP, resulting in Pmyo3::αS-YFP. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Transgenic animals C. elegans strains were cultured as described previously (Brenner, 1974) and kept at 20°C if not otherwise stated. To create transgenic animals expressing αS or its mutant forms in dopaminergic neurons the gonads of young adult wild-type N2 hermaphrodites were injected with a plasmid mix containing Pdat-1::α–syn (60 ng/μl) and Pdat-1::mCherry (40 ng/μl) as co-injection marker. The concentration of the αS expression constructs were chosen such that wild-type αS expression at this given concentration shows only a weak phenotype. The concentration of all other αS expression constructs was kept constant accordingly. To express mYFP citrine-tagged αS variants in body wall and sex muscles, a plasmid mix containing Pmyo3::αS-mYFP (40 ng/μl) and the co-injection markers pRF4 (rol-6(su1006sd); 40 ng/μl) and Pttx3::gfp (10 ng/μl) were injected. To allow comparable expression levels, the injection mix was always adjusted to a total DNA concentration of 100 ng/μl by adding pBlueScript SKII (Stratagene). Only transgenic lines showing highly uniform expression were selected and similar levels of αS expression were confirmed by RT–PCR and western blot. αS was detected using a polyclonal rabbit αS antibody (Anaspec). All blots were normalized against α-tubulin using monoclonal antibody 12G10 (DSHB).

To image αS-mYFP aggregation in muscle cells 10-day-old transgenic animals were anaesthetised and imaged using the UltraviewVOX spinning disk microscope (PerkinElmer). At least two independent strains per αS variant were imaged. Vulva muscles were scored positive if, at least, one fibrillar aggregate was visible.

Drosophila

Generation of transgenic flies. The site-specific recombination system based on φC31 integrase was used to generate transgenic flies (Bischof et al, 2007). The targeting constructs were prepared by cloning the cDNAs of αS variants into the GAL4-responsive pUAST expression vector containing the attachment site B (attB). The resulting plasmids were then injected into fly embryos, which were double homozygous for both attP (attachment site P) site and germ-line-specific φC31 integrase. The genomic location of the attP landing site used for integration was mapped to the cytological position 86Fb (ZH φX-86Fb line) and a GAL4-responsive lacZ-expressing line integrated into the same landing site was used for control experiments (Bischof et al, 2007). All the site-specific insertions were verified by single fly PCR using the primer pair: 5′-ACTGAAATCTGCCAAGAAGTA-3′ and 5′-GCAAGAAAGTATATCTCTATGACC3′.

Climbing assay. Flies expressing different αS variants were placed in an apparatus containing a bottom vial and an inverted upper vial. They were assayed for their ability to reach the upper vial from the bottom vial in 20 s. During the assay, to avoid photic effects from outside environment, both vials were encased in black boxes. As flies generally get attracted towards light, we have also provided a light source at the top of the upper vial with the help of two light emitting diodes. This type of set up provides a directionality and motivation for the flies to climb up.

Primary neuronal cultures. AAV-1/2 mosaic serotype viral vectors were prepared essentially as described previously (Kugler et al, 2007). Their genomes consisted of AAV-2 ITRs, human synapsin-1 gene promoter driving expression of αS variants, WPRE for enhanced mRNA stability and a bovine growth hormone polyadenylation site. Primary cortical and midbrain neurons were prepared from rat embryos at E18 or E16, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Online Material

Review Process File

Acknowledgments

We thank Min-Kyu Cho for useful discussions, Ulrike Schöll for primary neurons, Ellen Gerhard for help with HEK work and Monika Zebski for viral vector preparations and Christian Ader for advise regarding the analysis of the H2O-water ssNMR spectra. This study was supported by grants from the Max Planck Society and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (to CG); the BMBF (NGFN-Plus 01GS08190) to JBS, CG and MZ and through a DFG Heisenberg scholarship (ZW 71/2-1 and 3-1) to MZ. The CMPB groups were funded as part of the DFG excellence cluster CMPB (EXC171).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Ader C, Schneider R, Seidel K, Etzkorn M, Becker S, Baldus M (2009) Structural rearrangements of membrane proteins probed by water-edited solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 131: 170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoncini CW, Jung YS, Fernandez CO, Hoyer W, Griesinger C, Jovin TM, Zweckstetter M (2005) Release of long-range tertiary interactions potentiates aggregation of natively unstructured alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 1430–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof J, Maeda RK, Hediger M, Karch F, Basler K (2007) An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 3312–3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Feany MB (2005) Alpha-synuclein phosphorylation controls neurotoxicity and inclusion formation in a Drosophila model of Parkinson disease. Nat Neurosci 8: 657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon M, Chang I, Mohanty S, Luheshi LM, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M, Favrin G (2007) Structural reorganisation and potential toxicity of oligomeric species formed during the assembly of amyloid fibrils. PLoS Comput Biol 3: 1727–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimon S, Shaibat MA, Jones CR, Calero DC, Aizezi B, Ishii Y (2007) Evidence of fibril-like beta-sheet structures in a neurotoxic amyloid intermediate of Alzheimer′s beta-amyloid. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14: 1157–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KA, Lee SJ, Rochet JC, Ding TT, Williamson RE, Lansbury PT Jr (2000) Acceleration of oligomerization, not fibrillization, is a shared property of both alpha-synuclein mutations linked to early-onset Parkinson's disease: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 571–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson MR, van der Brug M (2008) Cell systems and the toxic mechanism(s) of alpha-synuclein. Exp Neurol 209: 5–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AA, Gitler AD, Cashikar A, Haynes CM, Hill KJ, Bhullar B, Liu K, Xu K, Strathearn KE, Liu F, Cao S, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Marsischky G, Kolodner RD, Labaer J, Rochet JC, Bonini NM, Lindquist S (2006) Alpha-synuclein blocks ER-Golgi traffic and Rab1 rescues neuron loss in Parkinson's models. Science 313: 324–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliezer D, Kutluay E, Bussell R Jr, Browne G (2001) Conformational properties of alpha-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J Mol Biol 307: 1061–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feany MB, Bender WW (2000) A Drosophila model of Parkinson′s disease. Nature 404: 394–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredenburg RA, Rospigliosi C, Meray RK, Kessler JC, Lashuel HA, Eliezer D, Lansbury PT Jr (2007) The impact of the E46K mutation on the properties of alpha-synuclein in its monomeric and oligomeric states. Biochemistry 46: 7107–7118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung BM, Khitrin AK, Ermolaev K (2000) An improved broadband decoupling sequence for liquid crystals and solids. J Magn Reson 142: 97–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganetzky B, Flanagan JR (1978) On the relationship between senescence and age-related changes in two wild-type strains of Drosophila melanogaster. Exp Gerontol 13: 189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George JM, Jin H, Woods WS, Clayton DF (1995) Characterization of a novel protein regulated during the critical period for song learning in the zebra finch. Neuron 15: 361–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M (2001) Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 492–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbatyuk OS, Li S, Sullivan LF, Chen W, Kondrikova G, Manfredsson FP, Mandel RJ, Muzyczka N (2008) The phosphorylation state of Ser-129 in human alpha-synuclein determines neurodegeneration in a rat model of Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 763–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum EA, Graves CL, Mishizen-Eberz AJ, Lupoli MA, Lynch DR, Englander SW, Axelsen PH, Giasson BI (2005) The E46K mutation in alpha-synuclein increases amyloid fibril formation. J Biol Chem 280: 7800–7807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamichi S, Rivas RN, Knight AL, Cao S, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA (2008) Hypothesis-based RNAi screening identifies neuroprotective genes in a Parkinson′s disease model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 728–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise H, Celej MS, Becker S, Riedel D, Pelah A, Kumar A, Jovin TM, Baldus M (2008) Solid-state NMR reveals structural differences between fibrils of wild-type and disease-related A53T mutant alpha-synuclein. J Mol Biol 380: 444–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise H, Hoyer W, Becker S, Andronesi OC, Riedel D, Baldus M (2005) Molecular-level secondary structure, polymorphism, and dynamics of full-length alpha-synuclein fibrils studied by solid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 15871–15876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer W, Antony T, Cherny D, Heim G, Jovin TM, Subramaniam V (2002) Dependence of alpha-synuclein aggregate morphology on solution conditions. J Mol Biol 322: 383–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai A, Masliah E, Yoshimoto M, Ge N, Flanagan L, de Silva HA, Kittel A, Saitoh T (1995) The precursor protein of non-A beta component of Alzheimer′s disease amyloid is a presynaptic protein of the central nervous system. Neuron 14: 467–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PH, Nielsen MS, Jakes R, Dotti CG, Goedert M (1998) Binding of alpha-synuclein to brain vesicles is abolished by familial Parkinson′s disease mutation. J Biol Chem 273: 26292–26294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG (2003) Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science 300: 486–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler S, Hahnewald R, Garrido M, Reiss J (2007) Long-term rescue of a lethal inherited disease by adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer in a mouse model of molybdenum-cofactor deficiency. Am J Hum Genet 80: 291–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara T, Koyama A, Gengyo-Ando K, Masuda M, Kowa H, Tsunoda M, Mitani S, Iwatsubo T (2006) Familial Parkinson mutant alpha-synuclein causes dopamine neuron dysfunction in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem 281: 334–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakso M, Vartiainen S, Moilanen AM, Sirvio J, Thomas JH, Nass R, Blakely RD, Wong G (2003) Dopaminergic neuronal loss and motor deficits in Caenorhabditis elegans overexpressing human alpha-synuclein. J Neurochem 86: 165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashuel HA, Lansbury PT Jr (2006) Are amyloid diseases caused by protein aggregates that mimic bacterial pore-forming toxins? Q Rev Biophys 39: 167–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH (2006) A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature 440: 352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Veinbergs I, Mallory M, Hashimoto M, Takeda A, Sagara Y, Sisk A, Mucke L (2000) Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science 287: 1265–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda M, Dohmae N, Nonaka T, Oikawa T, Hisanaga S, Goedert M, Hasegawa M (2006) Cysteine misincorporation in bacterially expressed human alpha-synuclein. FEBS Lett 580: 1775–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE, Sonsalla PK, Chesselet MF (2008) Animal models of Parkinson′s disease progression. Acta Neuropathol 115: 385–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narhi L, Wood SJ, Steavenson S, Jiang Y, Wu GM, Anafi D, Kaufman SA, Martin F, Sitney K, Denis P, Louis JC, Wypych J, Biere AL, Citron M (1999) Both familial Parkinson′s disease mutations accelerate alpha-synuclein aggregation. J Biol Chem 274: 9843–9846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nass R, Blakely RD (2003) The Caenorhabditis elegans dopaminergic system: opportunities for insights into dopamine transport and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 43: 521–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris EH, Giasson BI, Lee VM (2004) Alpha-synuclein: normal function and role in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Top Dev Biol 60: 17–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opazo F, Krenz A, Heermann S, Schulz JB, Falkenburger BH (2008) Accumulation and clearance of alpha-synuclein aggregates demonstrated by time-lapse imaging. J Neurochem 106: 529–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrerova N, Petrucelli L, Farrer M, Mehta N, Choi P, Hardy J, Wolozin B (1999) alpha-Synuclein shares physical and functional homology with 14-3-3 proteins. J Neurosci 19: 5782–5791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outeiro TF, Lindquist S (2003) Yeast cells provide insight into alpha-synuclein biology and pathobiology. Science 302: 1772–1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periquet M, Fulga T, Myllykangas L, Schlossmacher MG, Feany MB (2007) Aggregated alpha-synuclein mediates dopaminergic neurotoxicity in vivo. J Neurosci 27: 3338–3346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkova AT, Leapman RD, Guo Z, Yau WM, Mattson MP, Tycko R (2005) Self-propagating, molecular-level polymorphism in Alzheimer′s beta-amyloid fibrils. Science 307: 262–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudou F, Finkbeiner S, Devys D, Greenberg ME (1998) Huntingtin acts in the nucleus to induce apoptosis but death does not correlate with the formation of intranuclear inclusions. Cell 95: 55–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel K, Lange A, Becker S, Hughes CE, Heise H, Baldus M (2004) Protein solid-state NMR resonance assignments from (C-13, C-13) correlation spectroscopy. Phys Chem Chem Phys 6: 5090–5093 [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M (1997) Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388: 839–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunde M, Blake C (1997) The structure of amyloid fibrils by electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction. Adv Protein Chem 50: 123–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabrizi SJ, Orth M, Wilkinson JM, Taanman JW, Warner TT, Cooper JM, Schapira AH (2000) Expression of mutant alpha-synuclein causes increased susceptibility to dopamine toxicity. Hum Mol Genet 9: 2683–2689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ham TJ, Thijssen KL, Breitling R, Hofstra RM, Plasterk RH, Nollen EA (2008) C. elegans model identifies genetic modifiers of alpha-synuclein inclusion formation during aging. PLoS Genet 4: e1000027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilar M, Chou HT, Luhrs T, Maji SK, Riek-Loher D, Verel R, Manning G, Stahlberg H, Riek R (2008) The fold of alpha-synuclein fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 8637–8642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volles MJ, Lansbury PT Jr (2007) Relationships between the sequence of alpha-synuclein and its membrane affinity, fibrillization propensity, and yeast toxicity. J Mol Biol 366: 1510–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou DH, Kloepper KD, Winter KA, Rienstra CM (2006) Band-selective 13C homonuclear 3D spectroscopy for solid proteins at high field with rotor-synchronized soft pulses. J Biomol NMR 34: 245–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Hurlbert MS, Schaack J, Prasad KN, Freed CR (2000) Overexpression of human alpha-synuclein causes dopamine neuron death in rat primary culture and immortalized mesencephalon-derived cells. Brain Res 866: 33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Online Material

Review Process File