Abstract

Background

The association between New York Heart Association (NYHA) class and outcomes in heart failure patients with preserved systolic function is not well known.

Methods

We performed a retrospective follow-up study of 988 heart failure patients with ejection fraction >45% who participated in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial. Using Cox proportion hazard models we estimated risks for all-cause mortality, heart failure mortality, all-cause hospitalization and hospitalization due to worsening heart failure during a median follow up of 38.5 months.

Results

Patients had a median age of 68 years, 41.2% were female, and 13.9% nonwhites. Overall, 23.4% of patients died, and 19.9% were hospitalized due to worsening heart failure. Proportion of patients with NYHA classes I, II, III and IV were respectively 19.9%, 58.0%, 20.9% and 1.2%, and respectively 14.7%, 21.1%, 35.9% and 58.3% died from all causes (p for trend <0.001). Respective rates for heart failure-related hospitalizations were 14.2%, 17.1%, 32.5% and 33.3% (p for trend <0.001). Compared with NYHA class I patients, adjusted hazard ratios {HR}for all-cause mortality for class II, III and IV patients respectively were 1.54 (95% confidence intervals {CI}=1.02-2.32; p=0.042), 2.56 (95%CI=1.64-24.01; p<0.001) and 8.46 (95%CI=3.57-20.03; p<0.001). Respective adjusted HR (95% CI) for hospitalization due to heart failure for class II, III, and IV patients were 1.16 (0.76-1.77; p=0.502), 2.27 (1.45-3.56; p<0.001) and 3.71 (1.25-11.02; p=018). NYHA classes II-IV were also associated with higher risk of all-cause hospitalization.

Conclusion

Higher NYHA classes were associated with poorer outcomes in heart failure patients with preserved systolic function.

Keywords: heart failure, preserved systolic function, NYHA class, outcomes

The association between higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classes and poorer outcomes in heart failure patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction is widely recognized.1-5 However, the association between NYHA functional class and outcomes in heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function is not known. The objective of this study was to determine if higher NYHA classes were associated with poorer outcomes in ambulatory chronic heart failure patients with preserved systolic function.

METHODS

In the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial, 7,788 ambulatory chronic heart failure patients with normal sinus rhythm from 302 clinical centers in the United States (186 centers) and Canada (116 centers) were randomized to receive digoxin or placebo to determine the effects of digoxin on mortality and hospitalization.6, 7 The main trial consisted of 6,800 patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤45 %. In the ancillary DIG trial, 988 heart failure patients with LVEF >45% (preserved systolic function or “probable” diastolic heart failure)8 were recruited, who are the subject of the current analysis.

Participants were recruited during a 31.5-month period between January 1991 and August 1993. Heart failure was diagnosed based on current or past clinical symptoms or signs or radiographic evidence of pulmonary congestion. Left ventricular systolic function was evaluated by two-dimensional echocardiography, radionuclide ventriculography or contrast left ventriculography. NYHA class was determined at baseline by the participating investigators. Patients were recruited irrespective of their heart failure etiology or NYHA functional class. Patients with non-sinus rhythm were excluded, and all patients were encouraged to be on angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.6, 9

Patients in the ancillary DIG trials were followed for a median of 38.5 months, with a range from 0.3 to 58.8 months. The primary outcome of the DIG trial was all-cause mortality, which is also the primary outcome for this analysis. In addition, we studied various pre-specified secondary outcomes, including mortality due to worsening heart failure, hospitalizations due to all causes, and those due to worsening heart failure. Vital status of all patients was collected up to December 31, 1995. Vital status of 97 (1.2% of the total 7788 patients) remained unknown.7

We compared baseline characteristics between NYHA class I-II and III-IV patients using Pearson Chi-square tests and Mann-Whitney tests when appropriate. Because of the small proportion of patients in NYHA class IV, for comparison of baseline characteristics (Table 1), we combined class III and IV patients into one group. The normality of distribution of data for continuous variables was tested using One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test. Values of continuous and categorical variables are respectively expressed as median and number (percentage). Chronic kidney disease was defined as glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/1.73 m2 as calculated by the Dietary Modification of Renal Disease formula.10 We then compared bivariate survival curves for all-cause mortality, mortality due to worsening heart failure, all-cause hospitalization, and hospitalization due to worsening heart failure among all 4 NYHA classes using Kaplan-Meier estimates and tested statistical significance using log-rank test. Next, we used multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analysis to determine the association between NYHA class and all-cause mortality, mortality due to worsening heart failure, all-cause hospitalization and hospitalization due to worsening heart failure. We examined the assumption of proportional hazards by checking survival curves of individual covariates on a log-minus-log scale. Dummy variables for NYHA classes II to IV were used as a dependent predictor variable in the model (NYHA class I was used as the reference category). We forced age (years), sex (female=1), and race (non-white=1) into the model. Other covariates were entered into the model in a forward stepwise fashion and included body mass index as kilograms weight per meter of height squared, duration of heart failure in months, etiology of heart failure, comorbidities viz., myocardial infarction, current angina, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease, medications viz., digoxin use before trial entry and by randomization, ACE inhibitors, non-potassium sparing diuretics, and potassium supplements, heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, symptoms and signs of heart failure within one month before randomization viz., dyspnea at rest and on exertion, jugular venous distension, third heart sound, pulmonary râles, lower extremity edema, pulmonary congestion, cardiothoracic ratio of 0.5 or greater by chest x-ray, serum creatinine and potassium levels, and LVEF.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics in patients with New York Heart Association class III-IV versus I-II in heart failure patients with left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 45%

| NYHA Class I-II | NYHA Class III-IV | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 770 (77.9%) | N = 218(22.1%) | ||

| Age (years), median | 67 | 71 | <0.001 |

| Female | 297 (38.6%) | 110 (50.5%) | 0.002 |

| Non-white | 113 (14.7%) | 24 (11.0%) | 0.184 |

| Body mass index (kilogram/meter squared), median | 27.5 | 28.5 | 0.049 |

| Duration of heart failure (months), median | 17 | 12 | 0.007 |

| Primary cause of heart failure | |||

| Ischemic | 440 (57.1%) | 117 (53.7%) | |

| Hypertensive | 165 (21.4%) | 57 (26.1%) | |

| Valvular | 59 (7.7%) | 13 (6.0%) | |

| Idiopathic | 78 (10.1%) | 26 (11.9%) | 0.219 |

| Alcoholic | 13 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Others | 15 (1.9%) | 5 (2.3%) | |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 382 (49.6%) | 107 (49.1%) | 0.939 |

| Current angina pectoris | 207 (26.9%) | 87 (39.9%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 457 (59.4%) | 133 (61.1%) | 0.696 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 216 (28.1%) | 69 (31.7%) | 0.310 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 365 (47.4%) | 128 (58.7%) | 0.004 |

| Medications | |||

| Pre-trial digoxin use | 274 (35.6%) | 74 (33.9%) | 0.688 |

| Digoxin by randomization | 386 (50.1%) | 106 (48.6%) | 0.702 |

| ACE inhibitors | 662 (86.0%) | 190 (87.2%) | 0.739 |

| Non-potassium sparing diuretics | 561 (72.9%) | 190 (87.2%) | <0.001 |

| Potassium sparing diuretics | 60 (7.8%) | 19 (8.7%) | 0.672 |

| Potassium supplement | 205 (26.6%) | 64 (29.4%) | 0.438 |

| Symptoms and signs of heart failure (within one month before randomization) | |||

| Dyspnea at rest | 109 (14.2%) | 90 (41.3%) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea on exertion | 511 (66.4%) | 211 (96.8%) | <0.001 |

| Jugular venous distension | 49 (6.4%) | 32 (14.7%) | <0.001 |

| Third heart sound | 70 (9.1%) | 33 (15.1%) | 0.012 |

| Pulmonary râles | 104 (13.5%) | 51 (23.4%) | 0.001 |

| Lower extremity edema | 176 (22.9%) | 97 (44.5%) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (beats/minute), median | 76 | 76 | 0.435 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg), median | |||

| Systolic | 136 | 140 | 0.657 |

| Diastolic | 80 | 78 | 0.254 |

| Chest radiograph findings (within one month before randomization) | |||

| Pulmonary congestion | 61 (7.9%) | 40 (18.3%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio greater than 0.5 | 360 (46.8%) | 136 (62.4%) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory data, median | |||

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.20 | 1.21 | 0.028 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.40 | 4.30 | 0.489 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%), median | 53 | 55 | 0.020 |

We then performed a subgroup analysis to compare the association between NYHA classes III-IV and all-cause mortality by age (<75 versus ≥75 years), sex, race (nonwhite versus white), heart failure etiology (ischemic versus others), and LVEF (45-54% versus ≥55%). We tested for the presence of interactions between NYHA class (III-IV) and each of the above subgroups using the Mantel–Haenszel test.. We also tested for interactions for each subgroup using Cox proportional-hazards models. For example, to test interaction between NYHA class and sex on death, we entered the main effect term for female sex, the main effect term for NYHA class III-IV and the interaction terms for female sex and NYHA class III-IV. All statistical tests were done using SPSS for Windows (Release 12.02), and two-tailed 95% confidence levels; a p <0.05 was required to reject the null hypothesis.

RESULTS

Patients had a median age of 68 years, 41.2% were female, and 13.9% were nonwhites. The proportions of patients in NYHA classes I, II, III and IV were respectively 19.8%, 58.1%, 20.9% and 1.2%. Table 1 compares baseline characteristics of heart failure patients in NYHA classes III-IV with those in NYHA classes I-II. Patients in NYHA classes III-IV were more likely to be older, female, have shorter duration of heart failure, current angina, chronic kidney disease, elevated jugular venous pressure, third heart sound, lower extremity edema, pulmonary congestion, and higher ejection fraction, and to be treated with diuretics.

Mortality

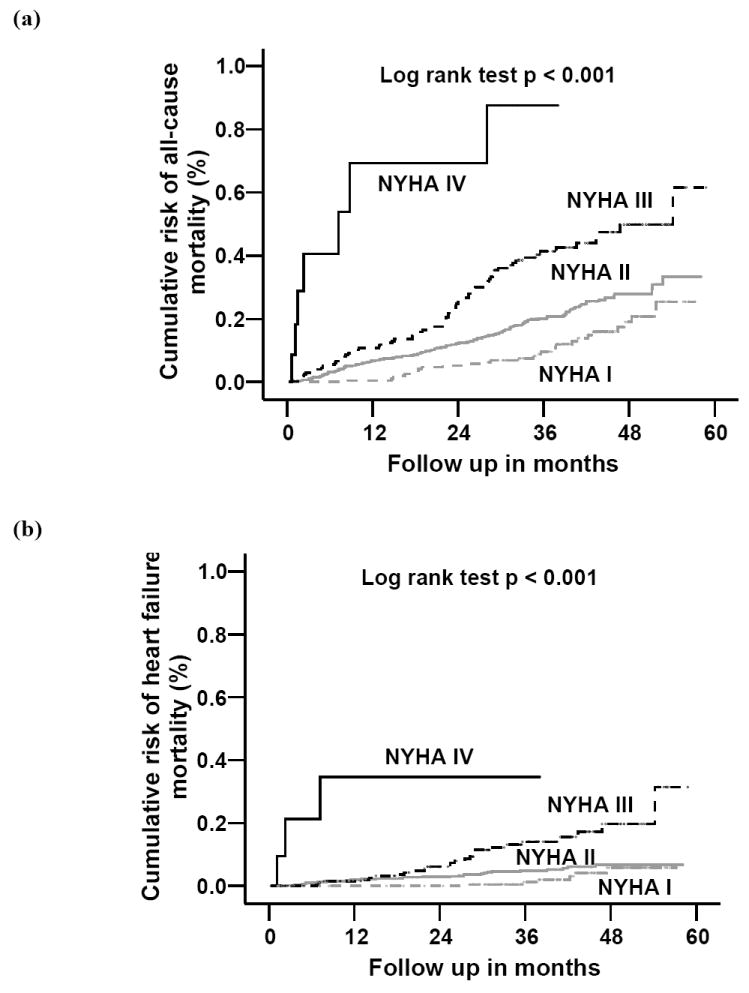

Overall, 231 patients (23.4%) died and 64 (6.5%) died from heart failure during the median follow up of 38.5 months. The proportions of patients with NYHA classes I, II, III, and IV symptoms who died from all causes during the study were respectively 14.3%, 21.3%, 35.9% and 58.3% (p for trend <0.001). Compared with a 19.5% incidence of death in patients with NYHA classes I and II, 37.2% of those in classes III and IV died (p <0.001). The proportions of patients with NYHA classes I, II, III, and IV who died from worsening heart failure were respectively 3.1%, 5.1%, 12.6% and 25.0% (p for trend <0.001). Compared with the 4.5% of NYHA class I-II patients who died from worsening heart failure, 13.3% of class III-IV patients died from this cause (p <0.001). Figures 1 (a) and 1 (b) respectively demonstrate the Kaplan-Meier plots for all-cause mortality and heart failure mortality for all four NYHA classes.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots for cumulative probability of (a) all-cause mortality and (b) heart failure mortality by New York Heart Association functional class

Table 2 displays the effect of NYHA class and other variables on all-cause mortality. Compared to patients with NYHA class I symptoms, the risk of death from all causes was about ten times greater (unadjusted hazards ratio {HR} = 9.69; 95% confidence interval {CI} = 4.22 –22.26) for patients with NYHA class IV symptoms. After adjustment for covariates in the multivariable model, presence of NYHA class IV symptoms was associated with over eight times greater risk of death (adjusted HR = 8.46; 95% CI = 3.57 – 20.03) (Table 2). Respective unadjusted HR (95%CI) for all-cause death for NYHA class III and II patients were 3.08 (2.00 –4.77) and 1.64 (1.09 – 2.48). Adjustment for other covariates did not alter these associations: adjusted HR (95% CI) for NYHA III and II respectively 2.56 (1.64 – 4.01) and 1.54 (1.02 – 2.32) (Table 2). When we restricted our analysis to the subset with LVEF greater than 55%, we found similar results (data not shown). Other covariates significantly associated with increased risk of all-cause death were age, presence of diabetes and chronic kidney disease, use of non-potassium sparing diuretics, and cardiothoracic ratio 0.5 or higher. Female sex and body mass index were negatively associated with risk of death.

TABLE 2.

Adjusted* hazard ratios for all-cause mortality in heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular function

| Hazard ratio | 95% confidence intervals | P value | |

| Age (years) | 1.03 | 1.01 - 1.04 | 0.001 |

| Female sex | 0.66 | 0.50 – 0.87 | 0.003 |

| Nonwhite race | 1.21 | 0.82 - 1.78 | 0.343 |

| NYHA class II | 1.54 | 1.02 – 2.32 | 0.042 |

| NYHA class III | 2.56 | 1.64 – 4.01 | <0.001 |

| NYHA class IV | 8.46 | 3.57– 20.03 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kilogram/meter squared) | 0.96 | 0.94 – 0.99 | 0.002 |

| Diabetes | 1.60 | 1.21 – 2.11 | 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2.00 | 1.49 – 2.68 | <0.001 |

| Use of non-potassium-sparing diuretics | 1.48 | 1.02 – 2.13 | 0.038 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio > 0.5 | 1.42 | 1.08 – 1.87 | 0.013 |

Adjusted for duration and etiology of heart failure, myocardial infarction, current angina, hypertension, use of ACE inhibitors, digoxin, potassium sparing diuretics, and potassium supplements, use of digoxin before trial and by randomization, dyspnea at rest and on exertion, heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, jugular venous distension, third heart sound, pulmonary râles, lower extremity edema, pulmonary congestion by chest x-ray, serum potassium level, and left ventricular ejection fraction.

Compared to patients with NYHA class I symptoms, the risk of death due to heart failure was about twenty times greater (unadjusted HR = 20.03; 95% CI = 4.93 – 81.33) for patients with NYHA class IV symptoms, which was somewhat lowered after adjustment for other covariates (adjusted HR = 16.94; 95% CI = 3.97 – 72.26). Respective unadjusted and adjusted HR (95% CI) for death due to heart failure for NYHA class III patients were 5.16 (2.12 – 12.54). and 3.75 (1.52 – 9.23). NYHA class II symptoms, on the other hand, was associated with a non-significant 84% increase in the risk of death from heart failure (unadjusted HR = 1.84; 95%CI = 0.77 – 4.44). The association remained unchanged after adjustment for covariates.

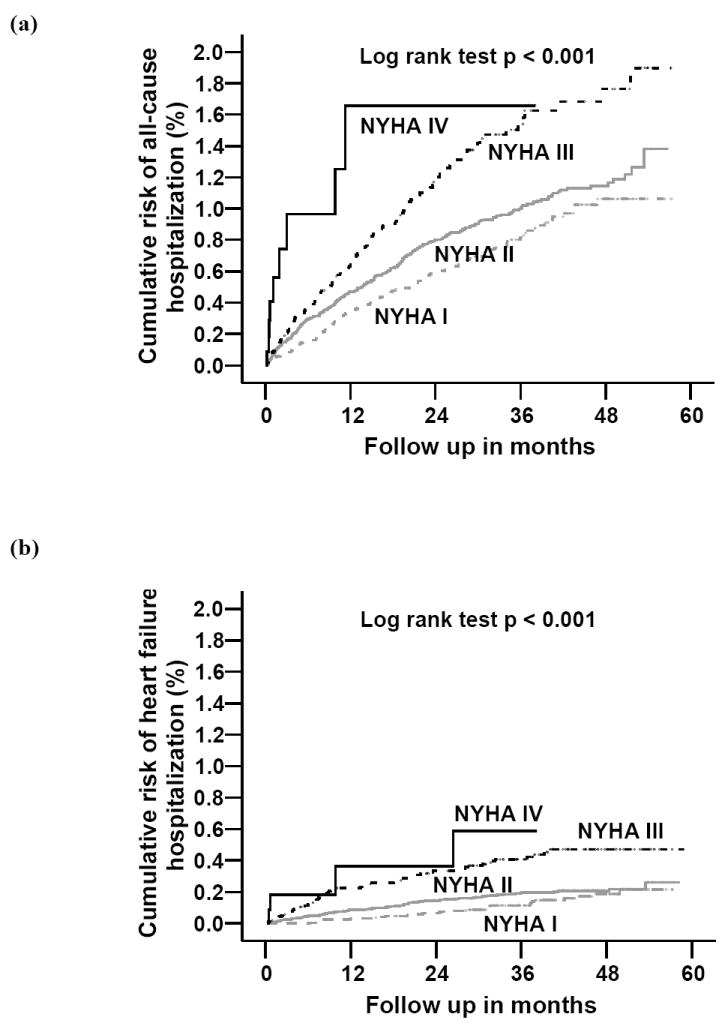

Hospitalization

Overall, 662 (67%) were hospitalized and 197 (19.9%) were hospitalized due to heart failure. The proportions of patients with NYHA class I, II, III, IV who were hospitalized due to all causes during the study were respectively 60.7%, 65.2%, 77.7%, and 75.0% (p for trend <0.001). The proportions of patients in NYHA classes I, II, III, and IV who were hospitalized due to worsening heart failure during the study were respectively 14.3%, 17.1%, 32.5% and 33.3% (p for trend <0.001). Figures 2 (a) and 2 (b) demonstrate respectively the Kaplan-Meier plots for all-cause hospitalization and hospitalization due to worsening heart failure for patients in all 4 NYHA classes.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots for cumulative probability of (a) all-cause hospitalization and (b) hospitalization due to worsening heart failure by New York Heart Association functional class

Compared to patients with NYHA class I symptoms, the risk of hospitalization from all causes was about three times greater (unadjusted HR = 3.33; 95% CI = 1.69 – 6.56) for patients with NYHA class IV symptoms. The association remained unchanged after multivariable adjustment (adjusted HR = 3.40; 95% CI = 1.69 – 6.84) (Table 3). NYHA class III patients had a significant 85% increased risk of all-cause hospitalization (unadjusted HR = 1.85 95% CI = 1.46 – 2.35), the magnitude of which was somewhat diminished after multivariable adjustment (adjusted HR = 1.72; 95% CI = 1.33 – 2.18) (Table 3). NYHA class II symptom was associated with a significant 25% increased risk of all-cause hospitalization (unadjusted HR = 1.25; 95%CI = 1.02 – 1.54). The association remained borderline significant after multivariable adjustment (adjusted HR = 1.23; 95% CI = 1.00 – 1.52) (Table 3). When we restricted our analysis to the subset with LVEF greater than 55%, we found similar results (data not shown). Other covariates significantly associated with increased risk of all-cause hospitalization were age, diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted* hazard ratios for all-cause hospitalization in heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular function

| Hazard ratio | 95% confidence intervals | P value | |

| Age (years) | 1.00 | 0.99 – 1.01 | 0.655 |

| Female sex | 0.87 | 0.73 – 1.02 | 0.091 |

| Nonwhite race | 0.94 | 0.75 – 1.18 | 0.596 |

| NYHA class II | 1.23 | 1.00 – 1.52 | 0.052 |

| NYHA class III | 1.71 | 1.33 – 2.18 | <0.001 |

| NYHA class IV | 3.40 | 1.69 – 6.84 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.31 | 1.10 – 1.54 | 0.002 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.24 | 1.05 – 1.46 | 0.012 |

| Use of non-potassium-sparing diuretics | 1.26 | 1.03 – 1.54 | 0.025 |

| Use of potassium-sparing diuretics | 0.72 | 0.53 – 0.99 | 0.043 |

| Ejection fraction | 1.02 | 1.01 – 1.03 | 0.002 |

Adjusted for body mass index, duration and etiology of heart failure, myocardial infarction, current angina, hypertension, use of ACE inhibitors, digoxin, and potassium supplements, use of digoxin before trial and by randomization, dyspnea at rest and on exertion, heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, jugular venous distension, third heart sound, pulmonary râles, lower extremity edema, pulmonary congestion and cardiothoracic ratio> 0.5 by chest x-ray, and serum potassium level.

NYHA IV patients had about five times higher risk of hospitalization due to worsening heart failure versus those with NYHA class I (unadjusted HR = 5.40; 95% CI = 1.89 – 15.41). Multivariable adjustment lowered the risk somewhat (adjusted HR = 3.71; 95% CI = 1.25 –11.02) (Table 4). Respective unadjusted HR (95% CI) for hospitalization due to heart failure for NYHA class III and II patients were 3.01 (1.94 – 4.69) and 1.34 (0.88 – 2.03). After multivariable adjustment, the HR for NYHA III symptoms remained significant (2.27; 95% CI 1.45 – 3.56) (Table 4). However, the association between class II symptoms and heart failure hospitalization lost its significance (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Adjusted* hazard ratios for hospitalization due to worsening heart failure in heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular function

| Hazard ratio | 95% confidence intervals | P value | |

| Age (years) | 1.01 | 1.00 - 1.03 | 0.118 |

| Female | 1.25 | 0.93 – 1.68 | 0.138 |

| Nonwhite | 1.35 | 0.91 – 2.01 | 0.140 |

| NYHA class II | 1.16 | 0.76 – 1.77 | 0.502 |

| NYHA class III | 2.27 | 1.45 – 3.56 | <0.001 |

| NYHA class IV | 3.71 | 1.25 – 11.02 | 0.018 |

| Diabetes | 1.77 | 1.32 – 2.36 | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.61 | 1.18 – 2.20 | 0.003 |

| Use of digoxin before trial | 1.43 | 1.07 – 1.91 | 0.016 |

| Heart rate (beats/ minute) | 1.02 | 1.01 – 1.03 | 0.001 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio >0.5 | 1.92 | 1.41 – 2.61 | <0.001 |

Adjusted for body mass index, duration and etiology of heart failure, myocardial infarction, current angina, hypertension, use of ACE inhibitors, digoxin, potassium sparing diuretics, and potassium supplements, use of digoxin by randomization, dyspnea at rest and on exertion, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, jugular venous distension, third heart sound, pulmonary râles, lower extremity edema, pulmonary congestion by chest x-ray, serum potassium level, and left ventricular ejection fraction.

Subgroup Analysis

Table 5 shows that the associations between higher NYHA classes and all-cause mortality were observed in various subgroups of patients, based on age, sex, race, heart failure etiology, and LVEF, although not all reached statistical significance.

TABLE 5.

Effect of New York Heart Association functional class on all-cause mortality in subgroups of heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular function

| NYHA class I-II | NYHA class III-IV | Adjusted* hazard ratio(95% confidence interval) | |

| No. of deaths / total no. | |||

| Age (year) | |||

| ≥75 | 43 / 153 (28.1%) | 37 / 78 (47.4%) | 2.52 (1.52 – 4.09) |

| <75 | 107 / 617 (17.3%) | 44 / 140 (31.4%) | 1.67 (1.15 – 2.42) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 55 / 297 (18.5%) | 43 / 110 (39.1%) | 2.25 (1.49 – 3.41) |

| Male | 95 / 473 (20.1%) | 38 / 108 (35.2%) | 1.68 (1.14 – 2.48) |

| Race | |||

| Non-white | 21 / 113 (18.6%) | 10 / 24 (41.7%) | 1.82 (0.82 – 4.05) |

| White | 129 / 657 (19.6%) | 71 / 194 (36.6%) | 1.57 (1.15 – 2.14) |

| Heart failure etiology | |||

| Ischemic | 84 / 440 (19.1%) | 43 / 117 (36.8%) | 1.94 (1.31 – 2.86) |

| Non-ischemic | 66 / 330 (20.0%) | 38 / 101 (37.6%) | 1.93 (1.28 – 2.90) |

| Ejection fraction | |||

| 45-54% | 84/441 (19.0%) | 44/108 (40.7%) | 2.13 (1.44 – 3.14) |

| >55% | 66/329 (20.1%) | 37/110 (33.6%) | 1.48 (0.97 – 2.26) |

Covariates used in the multivariable model are the same as those reported in Table 2. Hazard ratio represents that of classes III and IV relative to classes I and II.

DISCUSSION

The results from the current analysis of the DIG dataset demonstrate that higher NYHA classes were associated with higher mortality and hospitalization among a wide spectrum of ambulatory chronic heart failure patients with preserved systolic function. These findings are important as NYHA functional classification is a simple tool for risk stratification in clinical practice and can be used to help tailor management of heart failure patients with preserved systolic function.

Compared with NYHA class I and II heart failure patients with a normal ejection fraction, those in NYHA classes III and IV were more likely to be older, women, have shorter duration of heart failure, and have current angina pectoris and chronic kidney disease. They were also more likely to be on diuretics, have a third heart sound, elevated jugular venous pressure, pulmonary râles, lower extremity edema, pulmonary congestion on chest x-ray and a higher LVEF. The higher all-cause mortality observed for patients in higher NYHA classes might in part be due to older age and presence of chronic kidney disease. However, after adjustment for those and other covariates, higher NYHA class was independently associated with poor outcomes in this group of ambulatory chronic heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function.

A strong association between NYHA class and outcomes in patients with systolic heart failure has been consistently reported in the literature.1-5, 11 However, less is known about the relationship between NYHA functional class and outcomes in ambulatory heart failure patients with preserved systolic function. As the current report was being peer-reviewed, Jones et al. reported that among heart failure patients from the DIG study with preserved systolic function, presence of NYHA classes III and IV was a strong predictor of all-cause mortality.12 In this analysis, we have examined the relationship between NYHA class and various adverse outcomes in ambulatory heart failure patients with preserved systolic function. Our results demonstrate a dose-response relationship between NYHA classes and heart failure mortality, all-cause hospitalizations and heart failure hospitalizations as well as confirming the relationship with all-cause mortality. These findings are important as NYHA class is a useful prognostic tool in patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function is especially common among community dwelling elderly heart failure patients.13-17

We also noted that age, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, use of non-potassium-sparing diuretics, and increased cardiothoracic ratio were associated with poor prognosis, as has been found in patients with systolic heart failure. As observed in the DIG ancillary study, use of digoxin was not associated with mortality or all cause hospitalization. However, use of digoxin was associated with an 18% reduction in risk for hospitalization due to worsening heart failure that bordered on significance (adjusted HR=0.82; 95% CI=0.62-1.09). Among participants in the DIG trial with LVEF ≤45%, use of digoxin was associated with a significant 28% reduction in risk of heart failure related hospitalization.6

Some limitations of the current analysis should be recognized. First is the retrospective nature of our study. To be consistent with the DIG trial design, we defined preserved systolic function based on a LVEF cut off of 45%, which might have included patients with mild systolic dysfunction. However, a subgroup analysis based on an ejection fraction cut off of 55% demonstrated similar results. In the DIG trial, NYHA functional class was ascertained at baseline. It is possible that many patients with higher NYHA classes moved to lower classes, and vice versa during the follow up. However, such misclassification was very likely random and thus might have actually underestimated the associations between NYHA class and adverse outcomes observed here. Finally, patients with atrial fibrillation were excluded from the DIG trial, and as such, the results of this study may not be generalizable to these patients.

In conclusion, strong and graded associations exist between NYHA functional class and mortality and hospitalization in community dwelling chronic heart failure patients with preserved systolic function. The results of ongoing and future studies examining the effect of pharmacological therapy with ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers, and aldosterone antagonists, and interventions such as aggressive treatment of depression and other risk factors, and rehabilitation therapies in these patients are eagerly awaited. Whether improvement in functional class would improve outcomes also remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) study was conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) Investigators. This manuscript has been reviewed by NHLBI for scientific content and consistency of data interpretation with previous The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) publications and significant comments have been incorporated prior to submission for publication.

Funding/Support: Dr. Ahmed is supported by a National Institutes of Health Mentored Patient- Oriented Research Career Development Award 1-K23-AG19211-01

References

- 1.Scrutinio D, Lagioia R, Ricci A, Clemente M, Boni L, Rizzon P. Prediction of mortality in mild to moderately symptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction. The role of the New York Heart Association classification, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, two-dimensional echocardiography and Holter monitoring. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:1089–95. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madsen BK, Hansen JF, Stokholm KH, Brons J, Husum D, Mortensen LS. Chronic congestive heart failure. Description and survival of 190 consecutive patients with a diagnosis of chronic congestive heart failure based on clinical signs and symptoms. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:303–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muntwyler J, Abetel G, Gruner C, Follath F. One-year mortality among unselected outpatients with heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1861–6. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2002.3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horwich TB, Fonarow GC, Hamilton MA, MacLellan WR, Borenstein J. Anemia is associated with worse symptoms, greater impairment in functional capacity and a significant increase in mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1780–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouvy ML, Heerdink ER, Leufkens HG, Hoes AW. Predicting mortality in patients with heart failure: a pragmatic approach. Heart. 2003;89:605–9. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.6.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:525–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins JF, Howell CL, Horney RA. Determination of vital status at the end of the DIG trial. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:726–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasan RS, Levy D. Defining diastolic heart failure: a call for standardized diagnostic criteria. Circulation. 2000;101:2118–21. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.17.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins JF, Egan D, Yusuf S, Garg R, Williford WO, Geller N. Overview of the DIG trial. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:269S–276S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, Kuchibhatla M, Gaulden LH, Cuffe MS, et al. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1849–56. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones RC, Francis GS, Lauer MS. Predictors of mortality in patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1025–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Evans JC, Reiss CK, Levy D. Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence and mortality in a population-based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1948–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senni M, Tribouilloy CM, Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Evans JM, Bailey KR, et al. Congestive heart failure in the community: a study of all incident cases in Olmsted County, Minnesota, in 1991. Circulation. 1998;98:2282–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottdiener JS, McClelland RL, Marshall R, Shemanski L, Furberg CD, Kitzman DW, et al. Outcome of congestive heart failure in elderly persons: influence of left ventricular systolic function. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:631–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-8-200210150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronow WS, Ahn C, Kronzon I. Comparison of incidences of congestive heart failure in older African-Americans, Hispanics, and whites. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:611–2. A9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed A, Roseman JM, Duxbury AS, Allman RM, DeLong JF. Correlates and outcomes of preserved left ventricular systolic function among older adults hospitalized with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2002;144:365–72. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.124058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]