Abstract

The critical processes of mitochondrial fission and fusion are regulated by members of the dynamin family of GTPases. Imbalances in mitochondrial fission and fusion contribute to neuronal cell death. For example, increased fission mediated by the dynamin-related GTPase, Drp1, or decreased fusion resulting from inactivating mutations in the OPA1 GTPase, cause neuronal apoptosis and/or neurodegeneration. Recent studies indicate that post-translational processing regulates OPA1 function in non-neuronal cells and moreover, aberrant processing of OPA1 is induced during apoptosis. To date, the post-translational processing of OPA1 during neuronal apoptosis has not been examined. Here, we show that cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) or neuroblastoma cells exposed to pro-apoptotic stressors display a novel N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 which is blocked by either pan-caspase or caspase-8 selective inhibitors. OPA1 cleavage occurs concurrently with mitochondrial fragmentation and cytochrome c release in CGNs deprived of depolarizing potassium (5K condition). Although a caspase-8 selective inhibitor prevents both 5K-induced OPA1 cleavage and mitochondrial fragmentation, recombinant caspase-8 fails to cleave OPA1 in vitro. In marked contrast, either caspase-8 or caspase-3 stimulates OPA1 cleavage in digitonin-permeabilized rat brain mitochondria, suggesting that OPA1 is cleaved by an intermembrane space protease which is regulated by active caspases. Finally, the N-terminal truncation of OPA1 induced during neuronal apoptosis removes an essential residue (K301) within the GTPase domain. These data are the first to demonstrate OPA1 cleavage during neuronal apoptosis and they implicate caspases as indirect regulators of OPA1 processing in degenerating neurons.

Keywords: Optic atrophy type 1 (OPA1), Dynamin GTPase, Mitochondrial fusion, Apoptosis, Caspase, Cerebellar granule neuron

1. Introduction

Normal mitochondrial function supports cell survival by generating ATP and sequestering pro-apoptotic proteins like cytochrome c. Conversely, impaired mitochondrial function initiates cell death via depletion of ATP, generation of reactive oxygen species, and release of pro-apoptotic molecules (Lang-Rollin et al., 2003; Polster and Fiskum, 2004). Numerous studies have provided compelling evidence that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a causative role in neurodegeneration (reviewed by Lin and Beal, 2006). Thus, elucidation of the molecular pathways that regulate mitochondrial structure and function in neurons is highly relevant to the discovery of novel therapeutic agents to combat neurodegenerative diseases.

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles whose structure and function are intimately connected. Recurrent membrane fission and fusion events are required to maintain diverse functions including electron transport, sequestration of pro-apoptotic mediators, and transmission of mitochondrial DNA during mitosis (Scott et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2005). Mitochondrial fission and fusion are regulated by dynamin family GTPases. In mammalian cells, the dynamin-related protein, Drp1, interacts with hFis1 to promote fission (Smirnova et al., 2001; Yoon et al., 2003). Mitochondrial fusion is driven by an interaction between OPA1 GTPase and the mitofusins, Mfn1/2 (Cipolat et al., 2004). Shifts in the balance of fission and fusion events contribute to mitochondrial depolarization, localization of pro-apoptotic Bax to mitochondria, and consequent release of cytochrome c in both non-neuronal cells and neurons (Frank et al., 2001; Yuan et al., 2006). In particular, inactivation or deletion of the fission proteins, Drp1 or hFis1, protects both non-neuronal cells and neurons from a variety of mitochondrial insults (Frank et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2004; Barsoum et al., 2006). Conversely, small interfering RNA-induced down-regulation of the fusion proteins, OPA1 or Mfn1, is sufficient to cause cytochrome c release and apoptosis (Olichon et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004; Sugioka et al., 2004).

The above findings indicate that loss of OPA1 function is an adequate stimulus to induce mitochondrial apoptosis. Furthermore, OPA1 can be released from mitochondria with cytochrome c, and loss of OPA1 from the intermembrane space (IMS) disrupts cristae architecture, enhances mitochondrial fragmentation, depolarizes the outer membrane, and diminishes cellular respiration (Olichon et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2005; Arnoult et al., 2005). In the context of neurodegenerative disease, loss-of-function mutations in OPA1 associated with mitochondrial dysfunction are causative in autosomal dominant optic atrophy, a disorder characterized by retinal ganglion cell degeneration, optic nerve atrophy and childhood blindness (Alexander et al., 2000; Delettre et al., 2000; Olichon et al., 2007).

In addition to down-regulation or mutations of OPA1 which compromise its GTPase function, post-translational processing of OPA1 has recently been shown to critically regulate its activity in non-neuronal cells. For instance, the integral inner mitochondrial membrane protease, presenilin-associated rhomboid-like (PARL), promotes the processing of OPA1 to a soluble IMS (long) form that protects mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from apoptosis principally by maintaining cristae architecture (Cipolat et al., 2006; Frezza et al., 2006). Conversely, the matrix m-AAA metalloprotease, paraplegin, has been suggested to cleave OPA1 to a fusion-incompetent (short) form in response to mitochondrial depolarization or pro-apoptotic stimuli in HeLa cells (Ishihara et al., 2006). However, the precise roles of PARL and paraplegin in OPA1 regulation are presently unclear since MEFs deficient in both of these proteases still show normal OPA1 processing (Duvezin-Caubet et al., 2007). Moreover, the aforementioned long and short forms of OPA1 appear to complement one another in regards to their mitochondrial fusion activities (Song et al., 2007). Finally, additional proteases (eg., the i-AAA protease, Yme1) have also recently been shown to cleave OPA1 in MEFs and HeLa cells, further indicating that the post-translational processing of OPA1 is very complex (Song et al., 2007; Griparic et al., 2007).

In contrast to the multitude of studies that have examined OPA1 processing in non-neuronal cells, post-translational processing of OPA1 has scarcely been investigated in neurons and not at all during neuronal apoptosis. Here, we describe a novel N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 in neurons undergoing apoptosis. Our findings suggest that caspases indirectly regulate the proteolysis and consequent inactivation of OPA1, which likely contributes to mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction during neuronal apoptosis and perhaps neurodegeneration.

2. Results

OPA1 is cleaved at its N-terminus and the cleavage product is partially released from mitochondria in CGNs undergoing apoptosis

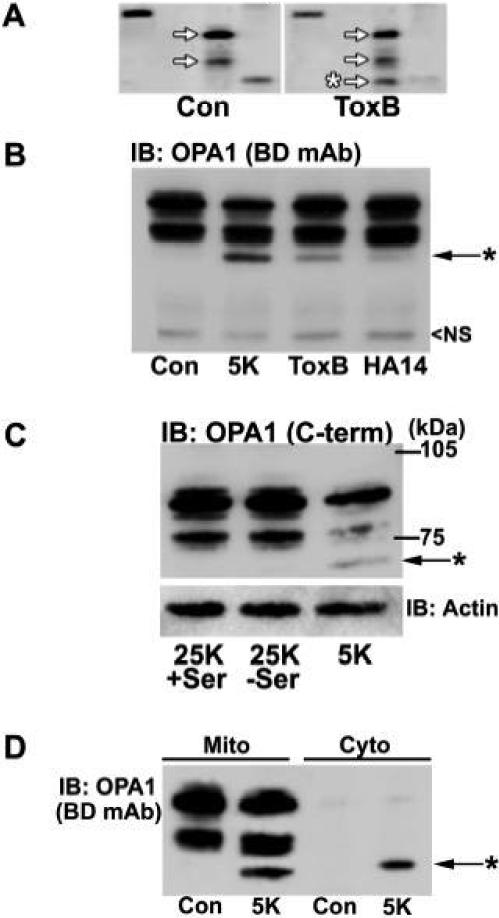

We have previously shown that C. difficile toxin B (ToxB) induces mitochondrial apoptosis in primary CGNs by inhibiting Rho family GTPases and in particular Rac (Linseman et al., 2001; Le et al., 2005; Loucks et al., 2006). In a high throughput immunoblotting screen (BD PowerBlot™) comparing lysates from control and ToxB-treated CGNs, we identified a prominent cleavage product of OPA1 following ToxB exposure (Fig. 1A, asterisk). OPA1 was observed primarily as a doublet in control conditions and was cleaved to yield a lower MW fragment after ToxB treatment. We also observed a similar cleavage of OPA1 with additional stimuli that induce mitochondrial apoptosis in CGNs (Fig. 1B, asterisk), including the removal of depolarizing potassium and serum [5K condition] (Linseman et al., 2002) or exposure to a small molecule Bcl-2 inhibitor, HA14-1 (Zimmermann et al., 2005; 2007). Because the monoclonal antibody used in Figs. 1A and 1B detects a region of OPA1 that is not in proximity to either the N- or C-terminus, we next examined OPA1 cleavage with a polyclonal antibody directed against the C-terminal 14 residues (Zhu et al., 2003). The cleavage product of OPA1 was readily detected by the C-terminal antibody in CGNs incubated in 5K conditions, indicating that the cleavage of OPA1 occurs at the N-terminus (Fig. 1C, asterisk). Moreover, in comparison to the 5K condition, removal of serum alone was insufficient to cause OPA1 cleavage in CGNs (Fig. 1C, 25K−Ser condition). Finally, full-length OPA1 was previously shown to be released from mitochondria with cytochrome c in HeLa cells exposed to staurosporine [STS] (Arnoult et al., 2005). However, in CGNs incubated in 5K for 24 h, full-length OPA1 was retained within the mitochondria while a small fraction of the cleavage product was released into the cytosol (Fig. 1D, asterisk). Appearance of the OPA1 cleavage product in the cytosolic fraction of 5K-treated CGNs was not due to contamination of the cytosolic fraction with mitochondria since no full-length OPA1 was detected in the cytosolic fraction of any treatment condition. Further studies indicated that this partial release of the OPA1 cleavage product from mitochondria occurred only late in CGN apoptosis (see Fig. 5A).

Fig. 1. Pro-apoptotic stimuli induce a unique N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 in CGNs.

A) CGNs were incubated for 24 h in medium containing 25 mM KCl and serum (Con) ± C. difficile toxin B (ToxB; 40 ng/ml). As seen in a portion of the PowerBlot™, in Con, OPA1 appeared as a doublet (see arrows). ToxB induced cleavage of OPA1 to produce a lower MW fragment (asterisk). Other bands are distinct proteins that were probed for in the PowerBlot™. B) CGNs were incubated for 24 h in either Con medium, lacking serum and containing only 5 mM KCl (5K), or containing either ToxB (2 ng/ml) or HA14-1 (HA14; 15 μM). After incubation, a monoclonal antibody to residues 708-830 of OPA1 (BD mAb) was used for immunoblotting (IB). *denotes cleavage product. NS=non-specific band that indicates equal loading. C) CGNs were incubated for 24 h in either Con medium (25K+Ser), lacking serum only (25K−Ser), or 5K medium. OPA1 cleavage was assessed with a polyclonal antibody against the C-terminal 14 amino acids, residues 947-960 (C-term). *denotes cleavage product. The blot was then stripped and reprobed for actin as a loading control. D) CGNs were incubated in Con or 5K medium for 24 h, then fractionated into mitochondrial (Mito) and cytosolic (Cyto) subcellular fractions as described in Methods. The monoclonal OPA1 antibody was used for western blotting. *denotes cleavage product.

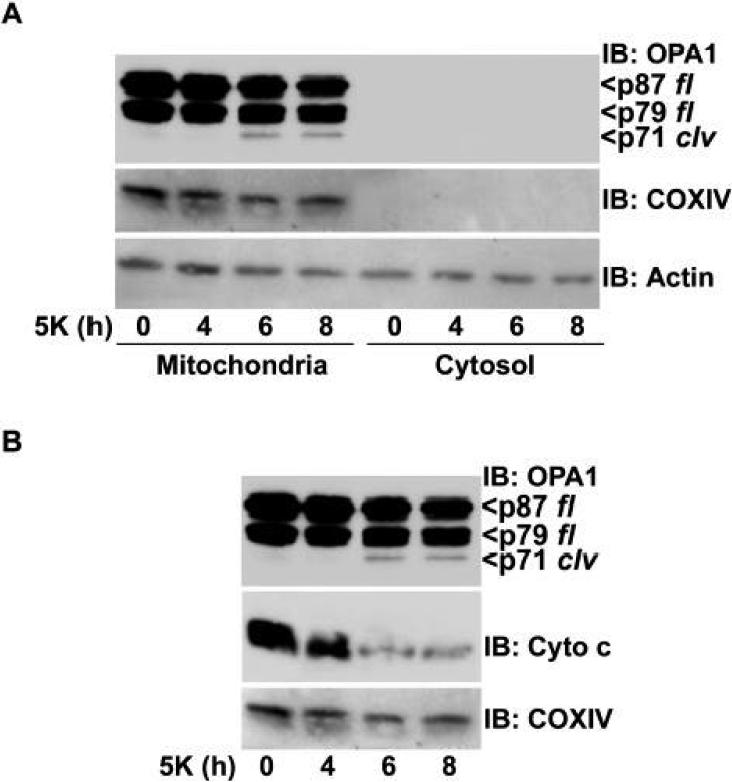

Fig. 5. OPA1 cleavage induced by 5K treatment occurs within mitochondria and is coincident with maximal release of cytochrome c.

A) CGNs were incubated in either Con medium (time 0) or for various times in 5K medium. Following incubation, CGNs were fractionated into mitochondrial and cytosolic subcellular fractions as described in Methods. OPA1 cleavage was assessed by immunoblotting (IB) with a monoclonal antibody. p87 fl and p79 fl indicate the full length OPA1 doublet. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product. The blot was then sequentially reprobed for COXIV and actin. B) CGNs were treated as described above and mitochondrial fractions were sequentially probed for OPA1, cytochrome c (Cyto c) and COXIV.

OPA1 cleavage induced by pro-apoptotic stressors is attenuated by caspase inhibitors

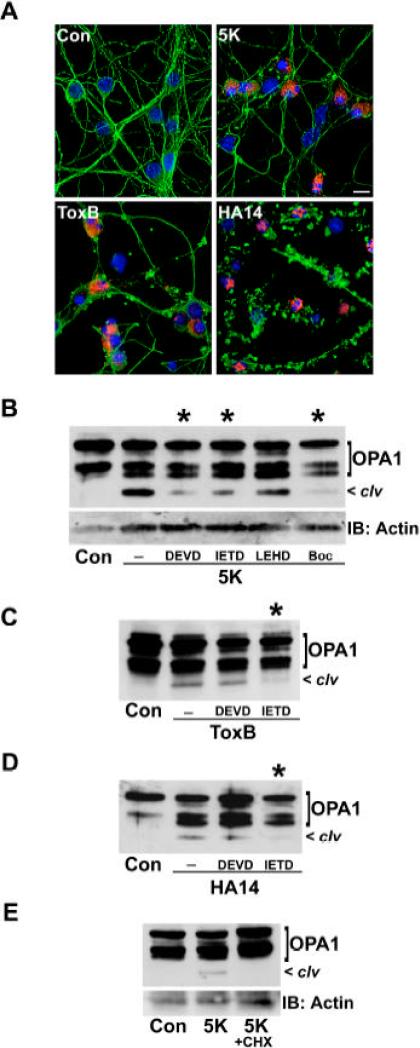

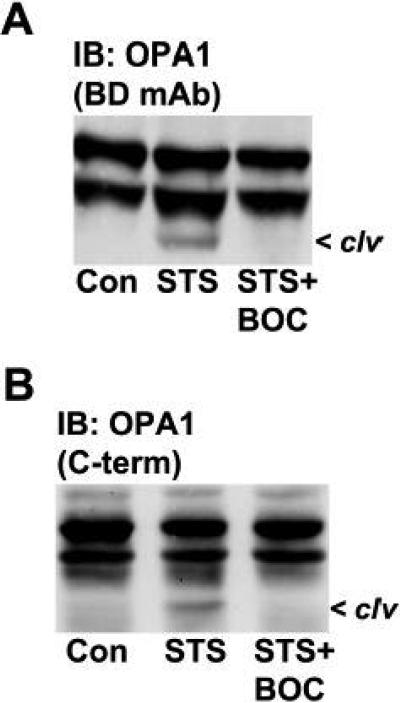

CGNs incubated in 5K medium or in the presence of either ToxB or HA14-1 undergo apoptosis as evidenced by nuclear condensation or fragmentation and activation of the executioner caspase-3 (Fig. 2A). In addition, each of these stimuli elicit apoptosis principally through the mitochondrial pathway because they induce cytochrome c release and activate the initiator caspase-9 (Linseman et al., 2002; Le et al., 2005; Zimmermann et al., 2005). To determine if the cleavage of OPA1 elicited by these pro-apoptotic stressors showed a dependence on caspase activity, CGNs were co-incubated with either selective or broad spectrum caspase inhibitors. Although the overall profile of caspase inhibitor effects varied between stimuli, substantial reductions in OPA1 cleavage were consistently observed with a selective caspase-8 inhibitor, IETD (Fig. 2B-D). This was not the case for the selective caspase-9 inhibitor (LEHD) for example, which actually enhanced OPA1 cleavage induced by the Bcl-2 inhibitor, HA14-1 (data not shown). Moreover, although the selective caspase-3 inhibitor (DEVD) markedly reduced OPA1 cleavage in 5K-treated CGNs (Fig. 2B), it had essentially no effect on OPA1 cleavage induced by either ToxB or HA14-1 (Fig. 2C, D). Finally, in CGNs incubated in 5K medium, not only did the pan-caspase inhibitor, BOC, significantly diminish OPA1 cleavage (Fig. 2B), but so did an inhibitor of protein synthesis (cycloheximide) which has previously been shown to prevent caspase activation in CGNs (Schulz et al., 1996) [Fig. 2E]. To establish that the caspase-dependence of OPA1 cleavage observed in CGNs was not cell type-specific, we examined the cleavage of OPA1 in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells treated with STS ± BOC. STS induced N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 in neuroblastoma cells which was indistinguishable from that observed in CGNs undergoing apoptosis, as evidenced by detection of the cleavage product with both monoclonal (Fig. 3A) and C-terminal polyclonal (Fig. 3B) antibodies. Furthermore, the STS-induced cleavage of OPA1 was effectively prevented by co-incubation with BOC. Thus, OPA1 cleavage induced during neuronal apoptosis occurs via a caspase-regulated pathway.

Fig. 2. Caspase inhibitors and protein synthesis inhibitors diminish OPA1 cleavage in neurons exposed to apoptotic stressors.

A) CGNs were incubated for 24 h in Con medium alone, with 2 ng/ml ToxB, with 15 μM HA14, or in 5K medium. CGNs were immunostained for β-tubulin (green) and active caspase-3 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. B-D) CGNs were incubated for 24 h in either Con medium or 5K (B), ToxB (C), or HA14 (D) conditions ± either selective caspase inhibitors (DEVD, IETD, LEHD, each at 100 μM) or the pan-caspase inhibitor, BOC (20 μM). E) CGNs were incubated for 24 h in either Con medium or 5K medium ± cycloheximide (CHX, 10 μg/ml). OPA1 cleavage was assessed by western blotting with a monoclonal antibody. *marks lanes where OPA1 cleavage was substantially reduced. Brackets indicate full length OPA1. clv denotes cleavage product. The OPA1 blots in (B) and (E) were stripped and reprobed for actin as a loading control.

Fig. 3. The caspase-dependent N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 occurs in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells exposed to staurosporine.

A,B) SH-SY5Y cells were incubated for 24 h in either the absence (Con) or presence of staurosporine (STS, 1 μM) ± BOC. OPA1 cleavage (clv) was detected by immunoblotting (IB) with either a monoclonal antibody (BD mAb) to residues 708-830 (A) or a polyclonal antibody (C-term) to the C-terminal 14 amino acids (B).

OPA1 cleavage, mitochondrial fragmentation, and cytochrome c release occur concomitantly in CGNs exposed to 5K

Based on resolving the full length and cleaved forms of OPA1 by SDS-PAGE, we approximated the MW of each of the three major bands of OPA1. The prominent doublet of OPA1 that we observed under control conditions corresponds to the full length (fl) protein and runs at ~87 kDa and ~79 kDa (Fig. 4A, p87 fl and p79 fl), while the cleavage (clv) fragment is estimated to be ~71 kDa (Fig. 4A, p71 clv). The substantial decrease in MW suggests that the truncated fragment of OPA1 likely lacks a significant portion of the N-terminus, perhaps including some of the GTPase domain of the protein (see last section of Results for further details). Consequently, in CGNs undergoing apoptosis, the N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 is predicted to form a truncated fragment with significantly compromised GTPase function. Therefore, we investigated if the 5K-induced cleavage of OPA1 was associated with enhanced fragmentation of mitochondria or release of cytochrome c.

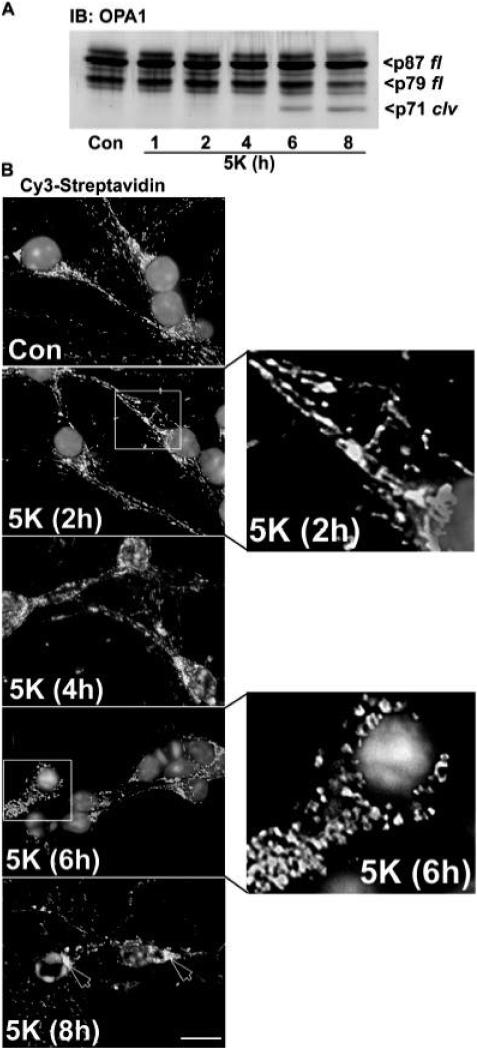

Fig. 4. Removal of depolarizing potassium induces cleavage of OPA1 that coincides with fragmentation of mitochondria in CGNs.

A) CGNs were incubated in either Con medium or for various times in 5K medium. OPA1 cleavage was assessed by immunoblotting (IB) with a monoclonal antibody. p87 fl and p79 fl indicate the full length OPA1 doublet. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product. B) CGNs from the same preparation as in (A) were incubated in Con or 5K conditions for up to 8 h. Cells were then fixed and stained with Cy3-streptavidin (to label mitochondria) and DAPI (to label nuclei). Mitochondrial rounding and fragmentation were evident by 6 h and perinuclear aggregation of mitochondria was apparent at 8 h (see arrowheads). Insets: CGNs incubated for either 2 h or 6 h in 5K (demarcated by the boxes) were enlarged 275% to show detailed mitochondrial structure. Scale bar, 10 μM.

First, we compared the kinetics of OPA1 cleavage to the appearance of fragmented mitochondria in CGNs incubated in 5K conditions. OPA1 cleavage was detectable by western blotting after 6 h of 5K exposure (Fig. 4A). Similarly, mitochondria visualized by Cy3-streptavidin staining showed a predominantly rounded and fragmented morphology after 6 h of 5K treatment as compared to control mitochondria which were mostly tubular in structure (Fig. 4B; also see enlargement of 2 h vs. 6 h in 5K).

Next, we compared the time frame of OPA1 cleavage to the release of cytochrome c in 5K-treated CGNs. Again, OPA1 cleavage was detected after 6 h of 5K treatment (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the OPA1 cleavage product was only observed in the mitochondrial fraction after 6 to 8 h of 5K treatment, demonstrating that OPA1 is processed within the IMS and the cleavage product is only released into the cytosol late in CGN apoptosis (eg., after 24 h of 5K; see Fig. 1D). In comparison to OPA1 cleavage, cytochrome c was partially released from mitochondria after 4 h of 5K exposure which was prior to the generation of any detectable OPA1 cleavage product (Fig. 5B). However, a marked increase in cytochrome c release was observed after 6 to 8 h of 5K coincident with the cleavage of OPA1 (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that a small readily releasable pool of cytochrome c can be released independently of OPA1 cleavage. Following this, a secondary pool of cytochrome c is released from mitochondria in conjunction with OPA1 processing, suggesting that loss of OPA1 function may contribute to a maximal release of cytochrome c by leading to disruption of the cristae architecture (Frezza et al., 2006).

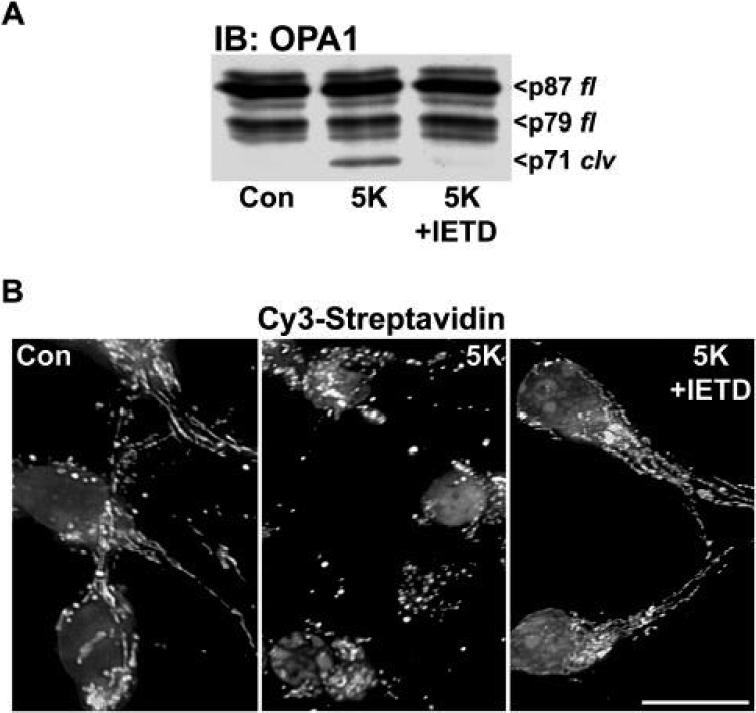

Finally, in addition to the temporal correlation between OPA1 cleavage and mitochondrial fragmentation, both events were substantially attenuated by inclusion of the selective caspase-8 inhibitor, IETD, during the 5K incubation (Figs. 6A, B). Collectively, these data suggest that OPA1 cleavage and consequent loss of its fusion GTPase function may contribute to an enhanced fragmentation of mitochondria and maximal cytochrome c release in CGNs undergoing apoptosis.

Fig. 6. The caspase-8 inhibitor, IETD, blocks 5K-induced OPA1 cleavage and concurrent mitochondrial fragmentation.

A) CGNs were incubated for 6 h in either Con or 5K medium ± a selective caspase-8 inhibitor (IETD, 100 μM). OPA1 cleavage was detected with a monoclonal antibody. p87 fl and p79 fl indicate the full length OPA1 doublet. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product. B) CGNs from the same preparation as in (A) were incubated exactly as described above, then stained with Cy3-streptavidin (to label mitochondria) and DAPI (to label nuclei). Scale bar, 10 μM.

Potential role of caspase-8 in OPA1 cleavage

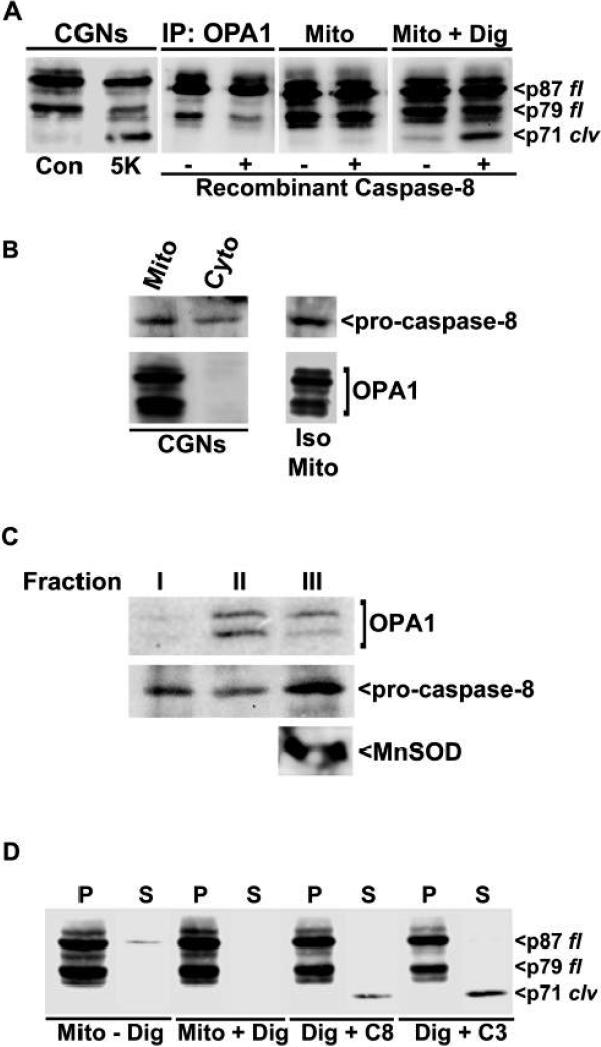

As described above, we found that the selective caspase-8 inhibitor, IETD, significantly diminishes OPA1 cleavage induced by diverse pro-apoptotic stimuli in CGNs (see Fig. 2B-D and Fig. 6A). However, the specificities of peptide-based caspase inhibitors like IETD are often disputed; therefore, we next examined if active recombinant caspase-8 could directly cleave OPA1 in vitro. OPA1 was immunoprecipitated from control CGN lysates and incubated in the absence or presence of recombinant caspase-8. Under these in vitro conditions, recombinant caspase-8 was unable to cleave OPA1 (Fig. 7A, second panel). Using PeptideCutter software (ExPASy (Expert Protein Analysis System) proteomics server of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics), we observed that the OPA1 sequence does not contain any consensus cleavage sites for caspases-1 through -10, further suggesting that caspase-8 may not directly cleave OPA1. Therefore, we examined the potential of recombinant caspase-8 to stimulate OPA1 processing in isolated rat brain mitochondria which should contain both endogenous OPA1 and the putative OPA1 protease. Predictably, incubation of intact mitochondria with recombinant caspase-8 did not result in any visible cleavage of OPA1, probably because the caspase could not enter the intact organelles (Fig. 7A, third panel). In contrast, permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane with digitonin yielded a slight increase in OPA1 cleavage which was markedly enhanced by the addition of recombinant caspase-8 (Fig. 7A, last panel). These results suggest that when active caspase-8 gains entry into mitochondria it has the potential to activate an IMS protease which then cleaves OPA1. Consistent with this possibility, we observed pro-caspase-8 immunoreactivity in mitochondrial fractions of CGNs, as well as in lysates obtained from isolated rat brain mitochondria (Fig. 7B). In addition, upon subfractionation of rat brain mitochondria we observed co-localization of pro-caspase-8 and OPA1 (Fig. 7C). OPA1 was detected principally in the mitochondrial subfractions containing soluble intermembrane space proteins (Fig. 7C, fraction II) and matrix/inner membrane proteins (Fig. 7C, fraction III); the latter fraction was identified by presence of the matrix marker protein, MnSOD. Pro-caspase-8 was distributed throughout each of the isolated mitochondrial subfractions. Finally, we found that in addition to caspase-8, incubation of digitonin-permeabilized rat brain mitochondria with recombinant caspase-3 similarly induced the processing of OPA1 to generate an identically sized fragment (Fig. 7D). Moreover, this fragment was released from the permeabilized mitochondria into the supernatant indicating that it was indeed a soluble form of OPA1. Given the lack of any consensus caspase cleavage sites within the OPA1 N-terminus, and the extremely low probability that these two caspases would cleave OPA1 at exactly the same site to generate identical products, we hypothesize that caspase-3 is activating the pro-caspase-8 present in isolated mitochondria (see Fig. 7B, C). In turn, caspase-8 then activates an IMS protease that ultimately cleaves OPA1 to produce a soluble fragment.

Fig. 7. OPA1 cleavage occurs downstream of caspase-8 or -3 activation.

A) CGNs were incubated in either Con or 5K medium. After lysis, aliquots of Con lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with a monoclonal OPA1 antibody, as described in Methods. Alternatively, isolated mitochondria (Mito) from whole rat brain were pre-incubated for 25 min on ice in MIB alone or containing digitonin (Mito + Dig). Immunoprecipitated OPA1, intact Mitos, or digitonin-permeabilized Mitos were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C ± recombinant caspase-8 (10 U/μl). OPA1 cleavage was assayed with a monoclonal antibody. p87 fl and p79 fl indicate the full length OPA1 doublet. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product. B) Healthy CGNs were fractionated into mitochondrial (Mito) and cytosolic (Cyto) subcellular fractions as described in Methods. Mitochondria were also isolated from whole rat brain (Iso Mito). CGN subcellular fractions and Iso Mito were immunoblotted for pro-caspase-8 and OPA1. Bracket indicates full length OPA1. C) Mitochondria isolated from whole rat brain were subjected to subfractionation as described in Experimental Procedures. After subfractionation, proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and membranes were sequentially probed for OPA1, pro-caspase-8, and MnSOD. The latter mitochondrial matrix marker protein was only detected in subfraction III. D) Isolated rat brain mitochondria (+/− digitonin permeabilization) were incubated with either recombinant caspase-8 (C8) or caspase-3 (C3), as described in (A). Following incubation, the mitochondrial pellets (P) were separated from the supernatants (S) by centrifugation and immunoblotted for OPA1.

N-terminal truncation of OPA1 removes the critical residue, K301, within the GTPase domain

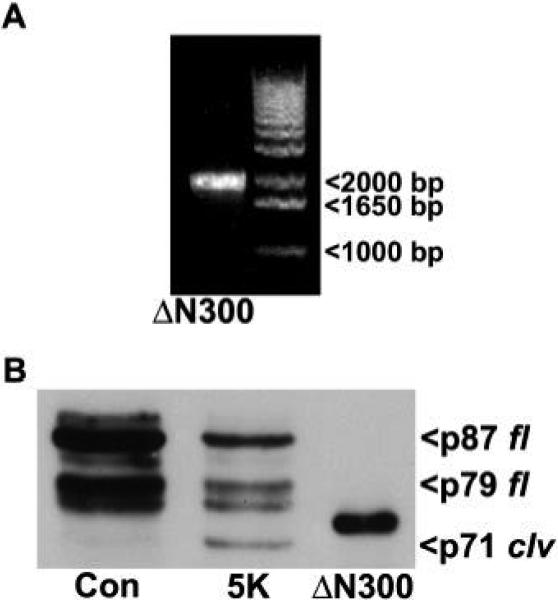

As stated above, we predict that the N-terminal cleavage of OPA1 observed in CGNs undergoing apoptosis yields a truncated fragment with significantly compromised GTPase function. Previous studies have shown that mutation of the critical K301 residue of OPA1 to an alanine causes an essentially complete loss of OPA1 GTPase function (Griparic et al., 2004; Griparic and Van der Bliek, 2005). To determine if the novel cleavage event we identified in CGNs undergoing apoptosis results in loss of this key lysine residue, we generated an N-terminal deletion mutant of OPA1 lacking the first 300 amino acids (ΔN300). As expected, the deletion mutant PCR product was ~2000 bp long (Fig. 8A) and the deletion was confirmed by sequence analysis. When compared with the endogenous OPA1 cleavage product observed in CGNs treated with 5K (p71 clv), the ΔN300 mutant displayed a substantially slower electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 8B). This result indicates that considerably more than the first 300 amino acids are cleaved off to form the endogenous N-terminal truncated OPA1 fragment which, as a result, migrates faster by SDS-PAGE than the ΔN300 mutant. Thus, the cleavage fragment of OPA1 lacks the essential residue, K301, thereby disrupting its GTPase activity. Therefore, this novel cleavage event produces a GTPase-deficient form of OPA1 which likely contributes to mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction during neuronal apoptosis.

Fig. 8. The OPA1 cleavage fragment lacks a critical lysine residue within the GTPase domain.

A) An N-terminal deletion mutant of OPA1 lacking the first 300 amino acids (ΔN300) was generated by PCR, then analyzed on a 1% agarose gel by SYBR Green staining as described in Methods. The size of the ΔN300 mutant PCR product was approximately 2000 bp. Sample is loaded in the left lane, a standard marker is loaded in the right lane. B) The PCR product of the ΔN300 mutant was purified and ligated into a pQE-30UA vector. Then, E. coli were transformed and stimulated with IPTG to produce the ΔN300 OPA1 protein as described in Methods. CGNs were incubated in either Con or 5K medium for 16 h. The ΔN300 OPA1 protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE alongside CGN lysates for a comparison of molecular weights. ΔN300 displays a substantially higher MW than the 5K-induced cleavage fragment of OPA1 indicating that the cleavage fragment is truncated well beyond the critical lysine, K301, which is required for OPA1 GTPase activity. OPA1 was detected with a monoclonal antibody. p87 fl and p79 fl indicate the full length OPA1 doublet. p71 clv denotes the cleavage product.

3. Discussion

Forced down-regulation of OPA1 by small interfering RNA is sufficient to induce cytochrome c release and apoptosis in non-neuronal cells (Olichon et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004). Furthermore, loss-of-function mutations in OPA1 underlie retinal ganglion cell death in dominant optic atrophy (Alexander et al., 2000; Delettre et al., 2000; Olichon et al., 2007). Despite the obvious relationship between OPA1 function and cell survival, regulation of OPA1 has not previously been examined during neuronal apoptosis. Several reports have recently implicated post-translational processing of OPA1 in the regulation of its activity in non-neuronal cells. Specifically, the rhomboid protease, PARL, has been shown to process OPA1 to a soluble IMS protein (Cipolat et al., 2006). This latter cleavage event appears to facilitate both OPA1 fusion activity and its ability to maintain cristae architecture (Frezza et al., 2006). On the other hand, in response to mitochondrial depolarization or apoptosis, the matrix m-AAA protease, paraplegin, has been reported to cleave OPA1 to a potentially fusion-deficient form (Ishihara et al., 2006). However, a very recent study demonstrated that cells deficient in both PARL and paraplegin show normal processing of OPA1, clearly indicating that OPA1 is a substrate for additional proteases (Duvezin-Caubet et al., 2007). One such protease may be the i-AAA protease, Yme1, which has recently been identified by two groups to cleave OPA1 in either HeLa cells or MEFs (Song et al., 2007; Griparic et al., 2007). In the present study, we have identified a novel proteolytic cleavage of the OPA1 GTPase in neurons undergoing apoptosis. The OPA1 cleavage product that we identify here is distinct from any of the previously identified forms described above. It is unique in at least three ways: 1) it has a lower MW (~71 kDa) than any OPA1 cleavage product previously described, 2) its formation is efficiently blocked by caspase inhibitors, and 3) it is partially released into the cytosol, albeit only late in neuronal apoptosis.

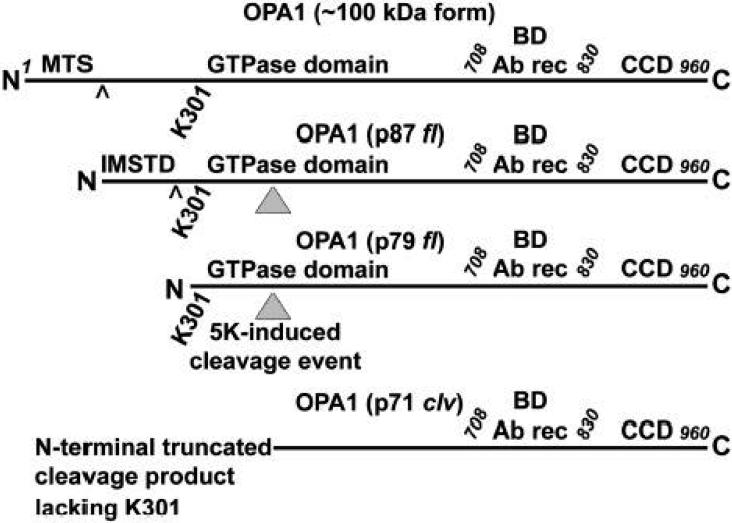

In Fig. 9, we show a proposed schematic of OPA1 processing based on our data and those previously published by several groups. Unprocessed OPA1 is a 960 amino acid protein with a MW of ~100 kDa. Removal of the mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) by a mitochondrial processing peptidase [predicted downstream of R101 (Misaka et al., 2002)] forms an ~90 kDa fl protein which we observe as an ~87 kDa band. Subsequent cleavage of an IMS targeting domain [IMSTD; predicted downstream of R258 (Misaka et al., 2002)] produces an ~80 kDa fl OPA1 protein which we see as an ~79 kDa band. This latter form of OPA1 has been suggested to be soluble within the IMS and may be generated by the actions of rhomboid proteases such as PARL (Cipolat et al., 2006). Induction of apoptosis (eg., by 5K in CGNs) results in further processing of OPA1 to remove ~8 kDa from the N-terminus. This novel cleavage event produces an ~70 kDa cleavage (clv) product which we detect as an ~71 kDa fragment. This latter fragment of OPA1 is distinct from that produced by m-AAA proteases, such as paraplegin, which reportedly form a higher MW cleavage product that is completely blocked by the metalloprotease inhibitor, o-phenanthroline, but is unaffected by the pan-caspase inhibitor, zVAD (Ishihara et al., 2006). In contrast, addition of o-phenanthroline to permeabilized rat brain mitochondria treated with recombinant caspase-8 had only a minor effect on OPA1 cleavage to the p71 fragment (data not shown). Moreover, either the pan-caspase inhibitor, BOC, or an inhibitor of protein synthesis (cycloheximide), which has previously been shown to prevent caspase activation in CGNs (Schulz et al., 1996), completely blocked OPA1 cleavage to the p71 fragment induced by 5K in CGNs (see Fig. 2B and 2E, respectively). These differences further demonstrate that the p71 fragment of OPA1 observed in CGNs undergoing apoptosis is generated by a novel cleavage event.

Fig. 9. Schematic of OPA1 processing.

See Discussion for details. MTS, mitochondrial targeting sequence; BD Ab rec, BD monoclonal antibody recognition site; CCD, coiled-coil domain; fl, full length; IMSTD, intermembrane space targeting domain; (^), indicates processing site; (gray triangle), indicates 5K-induced cleavage; clv, cleavage product.

Investigation into the mechanism of OPA1 cleavage in neurons undergoing apoptosis revealed that a caspase-8 selective inhibitor, IETD, largely prevented OPA1 cleavage. However, recombinant caspase-8 did not directly cleave OPA1 in vitro, but it instead stimulated OPA1 cleavage in digitonin-permeabilized rat brain mitochondria. Both pro- and active forms of caspase-8 have been shown to localize to mitochondria, although their precise distributions within this organelle are controversial. For example, Chandra et al. (2004) described caspase-8 localization as predominantly restricted to the outer membrane, while Qin et al. (2001) reported that pro-caspase-8 distribution included the IMS, inner membrane and matrix. In agreement with these studies, we detected pro-caspase-8 in both mitochondrial fractions of CGNs and in lysates of isolated rat brain mitochondria. Moreover, pro-caspase-8 was distributed throughout multiple subfractions of rat brain mitochondria and its localization significantly overlapped with OPA1 in two of these subfractions. Based on our findings, we propose that apoptotic stimuli first induce a mitochondrial caspase (eg., caspase-8). This may occur via caspase-3-dependent processing and activation of caspase-8 since recombinant caspase-3 or -8 each induced the formation of an identically sized fragment of OPA1 in permeabilized rat brain mitochondria. The activated mitochondrial caspase (perhaps caspase-8) then subsequently activates an IMS protease that is ultimately responsible for cleaving OPA1 to generate the p71 fragment. The N-terminal cleavage of OPA1, and consequent loss of its GTPase function, then contributes to the progression of mitochondrial fragmentation, disruption of the cristae and associated release of cytochrome c, and eventual neuronal death by apoptosis.

We postulate that the N-terminal truncation of OPA1 would have adverse effects on mitochondrial structure and function via multiple pathways. First, removal of K301 due to proteolytic cleavage of the N-terminus would result in a significant loss of intrinsic GTPase function (Griparic et al., 2004; Griparic and Van der Bliek, 2005). Next, the N-terminal truncated fragment of OPA1 retains its C-terminal coiled-coil domain (CCD). This protein:protein interaction domain may allow the GTPase-deficient cleavage product to form unproductive oligomers with other intact OPA1 molecules or with its pro-fusion partners within mitochondria (eg., Mfn1/2), thus acting in a dominant-negative manner to inhibit fusion. In this context, it is interesting to note that a recent study found that down-regulation of the mitofusin, Mfn2, induced apoptosis in CGNs, while overexpression of constitutively-active Mfn2 diminished 5K-induced CGN apoptosis (Jahani-Asl et al., 2007). These latter findings further support the hypothesis that sustaining mitochondrial fusion activity is essential for neuronal survival. Finally, some of the N-terminal truncated fragment of OPA1 is released into the cytosol, albeit late in neuronal apoptosis. Nonetheless, the release of this OPA1 fragment suggests the potential for a gain-of-function effect following its possible interaction with cytosolic proteins via the CCD. Collectively, the above scenarios indicate that generation of the N-terminal truncated fragment of OPA1 during neuronal apoptosis may contribute significantly to mitochondrial dysfunction during neurodegeneration.

In summary, we show that apoptotic stressors induce a novel N-terminal cleavage of the mitochondrial fusion GTPase, OPA1, in primary CGNs and in neuroblastoma cells. This cleavage event removes an essential lysine residue, K301, resulting in the formation of a GTPase-deficient fragment of OPA1. The cleavage of OPA1 in CGNs subjected to 5K (ie., removal of the depolarization stimulus) occurs in conjunction with mitochondrial fragmentation and both events are blocked by a selective caspase-8 inhibitor. In addition, OPA1 cleavage is associated temporally with a secondary but significant release of cytochrome c from mitochondria. Finally, the OPA1 cleavage event is replicated in digitonin-permeabilized rat brain mitochondria by incubation with recombinant active caspase-8 or caspase-3. These data are the first to show OPA1 cleavage in neurons undergoing apoptosis and identify caspases as indirect regulators of OPA1 processing in degenerating neurons.

4. Experimental Procedures

Reagents

Clostridium difficile toxin B (ToxB) was provided by Dr. Klaus Aktories and Dr. Torsten Giesemann (Albert-Ludwigs-Universitat Freiburg, Germany). The high-throughput immunoblotting screen (BD PowerBlot™) was done by BD Pharmingen (Palo Alto, CA, USA) and the monoclonal antibody to OPA1 (residues 708-830) was from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA). Polyclonal antibody to the C-terminus of OPA1 (residues 947-960) was prepared as described by Zhu et al. (2003). Selective inhibitors of caspase-3 (zDEVD-FMK), caspase-8 (zIETD-FMK) and caspase-9 (zLEHD-FMK), staurosporine, recombinant caspase-8 and caspase-3, cycloheximide and digitonin were from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA). Protein A/G-agarose was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The pancaspase inhibitor, Boc-D(OMe)-FMK, and HA14-1 were from Alexis/Axxora (San Diego, CA, USA). Polyclonal antibody to pro-caspase-8 was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies and reagents for enhanced chemiluminescence were from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Polyclonal antibody to active caspase-3 and JM109 competent cells were from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Cy3-streptavidin, 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and monoclonal β-tubulin antibody were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cy3- and FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence were from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). SYBR Green nucleic acid gel stain and PCR primers were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Plasmids

The sequence of OPA1 was the human OPA1 splice variant number 1 (accession # NM_015560). To generate an OPA1 construct with a C-terminal myc-tag, a Kozak consensus sequence followed by the full OPA1 sequence with the stop codon removed was cloned into the SmaI and BglII sites of the vector pGW1, and the C-terminal myc tag was cloned into the BglII and EcoRI sites followed immediately by a stop codon.

Cell culture

Primary cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) were isolated from 7-day-old Sprague-Dawley rat pups as described previously (Loucks et al., 2006). Isolated neurons were plated on poly-L-lysine-coated dishes in basal modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 25 mM KCl, 2 mM L-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cytosine arabinoside (10 μM) was added 24 h after plating to inhibit growth of non-neuronal cells. Experiments were performed after 6-7 DIV. SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were obtained from Dr. Stephen Fisher (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. SH-SY5Y cells were plated at ~10% confluency and differentiated by adding 100 μM retinoic acid every other day for 5 days.

Cell lysis and immunoblotting

After treatment as described in the Results, cells were lysed according to a previously published method (Loucks et al., 2006). Subcellular fractions were obtained using a mitochondrial/cytosol fractionation kit (Alexis/Axxora). For immunoprecipitation, lysates were incubated with 2 μg monoclonal OPA1 antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation for 4 h with 50 μl protein A/G-agarose and subsequent washing three times with lysis buffer. Whole cell lysates, subcellular fractions, or OPA1 immune complexes were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfatepolyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 7.5% polyacrylamide gels. Resolved proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Amersham) and processed for immunoblot analysis, as previously described (Loucks et al., 2006). In general, western blots shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Immunocytochemistry

CGNs were plated on polyethyleneimine-coated glass coverslips. After treatment as described in the Results, cells were fixed and processed for immunocytochemistry, as previously described (Loucks et al., 2006). For Cy3-streptavidin labeling of mitochondria, CGNs were fixed, permeabilized and then incubated with Cy3-streptavidin (1:200) and DAPI for 1 h. Fluorescent images were captured using 63X or 100X oil immersion objectives on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope. Images shown are representative of at least four fields per condition from at least three independent experiments.

Mitochondrial isolation and subfractionation from whole rat brain

Rat brain mitochondria were isolated by a previously published method (Liang and Patel, 2004). Briefly, whole brains were harvested from 7-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats in ice-cold mitochondrial isolation buffer (MIB) containing 0.064 M sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, and 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Brains were dounce homogenized and intact mitochondria were isolated by Percoll gradient centrifugation. The final mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in 150 μl MIB per brain. Subfractionation of isolated rat brain mitochondria was carried out essentially as described by Bakin and Jung (2004), and was based on the original protocol developed by Greenawalt (1974).

OPA1 cleavage assay with recombinant caspases

OPA1 immune complexes obtained from CGN lysates were resuspended in MIB (containing dithiothreitol at 1 mM) and incubated ± recombinant caspase-8 (10 U/μl) at 37°C for 1 h. In some experiments, isolated rat brain mitochondria were incubated with recombinant caspase-8 or -3 either directly or after permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane by pre-incubation with digitonin (0.4 mg/ml) for 25 min on ice. Following caspase treatment, immune complexes or isolated mitochondria were immunoblotted for OPA1.

N-terminal truncation of OPA1

To form an N-terminal truncation mutant of OPA1, primers were designed corresponding to nucleotides 956-982 (beginning at K301; 5’-AAgACTAgTgTgTTggAAATgATTgCC-3’) and nucleotides 2909-2935 (ending at the C-terminal residue 960; 5’-TTTCTCCTgATgA AgAgCTTCAATgAA-3). Using the AccuPrime Taq DNA polymerase system (Invitrogen), PCR was performed on the pGW1-OPA1 plasmid to form an OPA1 truncation mutant lacking the N-terminal 300 amino acids and the C-terminal myc tag. Cycling parameters were an initial 2 min at 94°C, then 30 cycles of 94°C for 20 sec, 57.5°C for 20 sec, and 68°C for 2 min. The resultant truncated OPA1 PCR product was visualized by UV on a 1% agarose gel with SYBR Green and confirmed by sequence analysis (Barbara Davis DNA sequencing core, UCHSC, Denver, CO, USA). The PCR product was purified using a Qiagen gel extraction kit and ligated into the QE-30UA vector (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). JM109 E. coli cells were transformed and stimulated with IPTG to produce the N-terminal truncated OPA1 mutant. The mutant was then resolved on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel alongside CGN lysates (25K, 5K conditions) to compare molecular weights.

Acknowledgements

Supported by a Merit Review grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs (to D.A.L.) and an AREA grant from the National Institutes of Health (to J.L.B.). We thank Dr. Klaus Aktories and Dr. Torsten Giesemann for C. difficile toxin B and Dr. Stephen Fisher for SH-SY5Y cells. We acknowledge Shoshona Le, Angela Zimmermann, and Ingrid Anderson for technical assistance.

Abbreviations used

- CGN

cerebellar granule neuron

- CHX

cycloheximide

- Drp1

dynamin-related protein-1

- ExPASy

Expert Protein Analysis System

- IMS

intermembrane space

- IMSTD

intermembrane space targeting domain

- MIB

mitochondrial isolation buffer

- MTS

mitochondrial targeting sequence

- PARL

presenilin-associated rhomboid-like

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- STS

staurosporine

- ToxB

Clostridium difficile toxin B

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexander C, Votruba M, Pesch UE, Thiselton DL, Mayer S, Moore A, Rodriguez M, Kellner U, Leo-Kottler B, Auburger G, Bhattacharya SS, Wissinger B. OPA1, encoding a dynamin-related GTPase, is mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy linked to chromosome 3q28. Nat Genet. 2000;26:211–215. doi: 10.1038/79944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnoult D, Grodet A, Lee YJ, Estaquier J, Blackstone C. Release of OPA1 during apoptosis participates in the rapid and complete release of cytochrome c and subsequent mitochondrial fragmentation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35742–35750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505970200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakin RE, Jung MO. Cytoplasmic sequestration of HDAC7 from mitochondrial and nuclear compartments upon initiation of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51218–51225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsoum MJ, Yuan H, Gerencser AA, Liot G, Kushnareva Y, Graber S, Kovacs I, Lee WD, Waggoner J, Cui J, White AD, Bossy B, Martinou JC, Youle RJ, Lipton SA, Ellisman MH, Perkins GA, Bossy-Wetzel E. Nitric oxide-induced mitochondrial fission is regulated by dynamin-related GTPases in neurons. Embo J. 2006;25:3900–3911. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra D, Choy G, Deng X, Bhatia B, Daniel P, Tang DG. Association of active caspase 8 with the mitochondrial membrane during apoptosis: potential roles in cleaving BAP31 and caspase 3 and mediating mitochondrion-endoplasmic reticulum cross talk in etoposide-induced cell death. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6592–6607. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6592-6607.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chomyn A, Chan DC. Disruption of fusion results in mitochondrial heterogeneity and dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26185–26192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Dal Zilio B, Scorrano L. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15927–15932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407043101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolat S, Rudka T, Hartmann D, Costa V, Serneels L, Craessaerts K, Metzger K, Frezza C, Annaert W, D'Adamio L, Derks C, Dejaegere T, Pellegrini L, D'Hooge R, Scorrano L, De Strooper B. Mitochondrial rhomboid PARL regulates cytochrome c release during apoptosis via OPA1-dependent cristae remodeling. Cell. 2006;126:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delettre C, Lenaers G, Griffoin JM, Gigarel N, Lorenzo C, Belenguer P, Pelloquin L, Grosgeorge J, Turc-Carel C, Perret E, Astarie-Dequeker C, Lasquellec L, Arnaud B, Ducommun B, Kaplan J, Hamel CP. Nuclear gene OPA1, encoding a mitochondrial dynamin-related protein, is mutated in dominant optic atrophy. Nat Genet. 2000;26:207–210. doi: 10.1038/79936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvezin-Caubet S, Koppen M, Wagener J, Zick M, Israel L, Bernacchia A, Jagasia R, Rugarli EI, Imhof A, Neupert W, Langer T, Reichert AS. OPA1 processing reconstituted in yeast depends on the subunit composition of the m-AAA protease in mitochondria. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3582–3590. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S, Gaume B, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Leitner WW, Robert EG, Catez F, Smith CL, Youle RJ. The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2001;1:515–525. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezza C, Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Micaroni M, Beznoussenko GV, Rudka T, Bartoli D, Polishuck RS, Danial NN, De Strooper B, Scorrano L. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell. 2006;126:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenawalt JW. The isolation of outer and inner mitochondrial membranes. Methods Enzymol. 1974;31:310–323. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)31033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griparic L, Kanazawa T, van der Bliek AM. Regulation of the mitochondrial dynamin-like protein Opa1 by proteolytic cleavage. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:757–764. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griparic L, van der Bliek AM. Assay and properties of the mitochondrial dynamin related protein Opa1. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:620–631. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griparic L, van der Wel NN, Orozco IJ, Peters PJ, van der Bliek AM. Loss of the intermembrane space protein Mgm1/OPA1 induces swelling and localized constrictions along the lengths of mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18792–18798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400920200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara N, Fujita Y, Oka T, Mihara K. Regulation of mitochondrial morphology through proteolytic cleavage of OPA1. Embo J. 2006;25:2966–2977. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahani-Asl A, Cheung EC, Neuspiel M, MacLaurin JG, Fortin A, Park DS, McBride HM, Slack RS. Mitofusin 2 protects cerebellar granule neurons against injury-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23788–23798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703812200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang-Rollin IC, Rideout HJ, Noticewala M, Stefanis L. Mechanisms of caspase-independent neuronal death: energy depletion and free radical generation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11015–11025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11015.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le SS, Loucks FA, Udo H, Richardson-Burns S, Phelps RA, Bouchard RJ, Barth H, Aktories K, Tyler KL, Kandel ER, Heidenreich KA, Linseman DA. Inhibition of Rac GTPase triggers a c-Jun- and Bim-dependent mitochondrial apoptotic cascade in cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1025–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Jeong SY, Karbowski M, Smith CL, Youle RJ. Roles of the mammalian mitochondrial fission and fusion mediators Fis1, Drp1, and Opa1 in apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5001–5011. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang LP, Patel M. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and increased seizure susceptibility in Sod2(-/+) mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:542–554. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linseman DA, Laessig T, Meintzer MK, McClure M, Barth H, Aktories K, Heidenreich KA. An essential role for Rac/Cdc42 GTPases in cerebellar granule neuron survival. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39123–39131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linseman DA, Phelps RA, Bouchard RJ, Le SS, Laessig TA, McClure ML, Heidenreich KA. Insulin-like growth factor-I blocks Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death (Bim) induction and intrinsic death signaling in cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9287–9297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09287.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loucks FA, Le SS, Zimmermann AK, Ryan KR, Barth H, Aktories K, Linseman DA. Rho family GTPase inhibition reveals opposing effects of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase and Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling cascades on neuronal survival. J Neurochem. 2006;97:957–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misaka T, Miyashita T, Kubo Y. Primary structure of a dynamin-related mouse mitochondrial GTPase and its distribution in brain, subcellular localization, and effect on mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15834–15842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olichon A, Baricault L, Gas N, Guillou E, Valette A, Belenguer P, Lenaers G. Loss of OPA1 perturbates the mitochondrial inner membrane structure and integrity, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7743–7746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olichon A, Landes T, Arnaune-Pelloquin L, Emorine LJ, Mils V, Guichet A, Delettre C, Hamel C, Amati-Bonneau P, Bonneau D, Reynier P, Lenaers G, Belenguer P. Effects of OPA1 mutations on mitochondrial morphology and apoptosis: relevance to ADOA pathogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:423–430. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polster BM, Fiskum G. Mitochondrial mechanisms of neural cell apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1281–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin ZH, Wang Y, Kikly KK, Sapp E, Kegel KB, Aronin N, DiFiglia M. Pro-caspase-8 is predominantly localized in mitochondria and released into cytoplasm upon apoptotic stimulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8079–8086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz JB, Weller M, Klockgether T. Potassium deprivation-induced apoptosis of cerebellar granule neurons: a sequential requirement for new mRNA and protein synthesis, ICE-like protease activity, and reactive oxygen species. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4696–4706. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-15-04696.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SV, Cassidy-Stone A, Meeusen SL, Nunnari J. Staying in aerobic shape: how the structural integrity of mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA is maintained. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:482–488. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova E, Griparic L, Shurland DL, van der Bliek AM. Dynamin-related protein Drp1 is required for mitochondrial division in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2245–2256. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z, Chen H, Fiket M, Alexander C, Chan DC. OPA1 processing controls mitochondrial fusion and is regulated by mRNA splicing, membrane potential, and Yme1L. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:749–755. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugioka R, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y. Fzo1, a protein involved in mitochondrial fusion, inhibits apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52726–52734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408910200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y, Krueger EW, Oswald BJ, McNiven MA. The mitochondrial protein hFis1 regulates mitochondrial fission in mammalian cells through an interaction with the dynamin-like protein DLP1. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5409–5420. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5409-5420.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H, Gerencser AA, Liot G, Lipton SA, Ellisman M, Perkins GA, Bossy-Wetzel E. Mitochondrial fission is an upstream and required event for bax foci formation in response to nitric oxide in cortical neurons. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:462–471. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu PP, Patterson A, Lavoie B, Stadler J, Shoeb M, Patel R, Blackstone C. Cellular localization, oligomerization, and membrane association of the hereditary spastic paraplegia 3A (SPG3A) protein atlastin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49063–49071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann AK, Loucks FA, Le SS, Butts BD, Florez-McClure ML, Bouchard RJ, Heidenreich KA, Linseman DA. Distinct mechanisms of neuronal apoptosis are triggered by antagonism of Bcl-2/Bcl-x(L) versus induction of the BH3-only protein Bim. J Neurochem. 2005;94:22–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann AK, Loucks FA, Schroeder EK, Bouchard RJ, Tyler KL, Linseman DA. Glutathione binding to the Bcl-2 homology-3 domain groove: a molecular basis for Bcl-2 antioxidant function at mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29296–29304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702853200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]