Summary

The two P-type lectins, the 46 kDa cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate (Man-6-P) receptor (CD-MPR) and the 300 kDa cation-independent Man-6-P receptor (CI-MPR), are the founding members of the growing family of mannose 6-phosphate receptor homology (MRH) proteins. A major cellular function of the MPRs is to transport Man-6-P-containing acid hydrolases from the Golgi to endosomal/lysosomal compartments. Recent advances in the structural analyses of both CD-MPR and CI-MPR have revealed the structural basis for phosphomannosyl recognition by these receptors and provided insights into how the receptors load and unload their cargo. A surprising finding is that the CD-MPR is dynamic, with at least two stable quaternary states, the open (ligand bound) and closed (ligand free) conformations, similar to those of hemoglobin. Ligand binding stabilizes the open conformation; changes in the pH of the environment at the cell surface and in endosomal compartments weaken the ligand-receptor interaction and/or weaken the electrostatic interactions at the subunit interface, resulting in the closed conformation.

Introduction

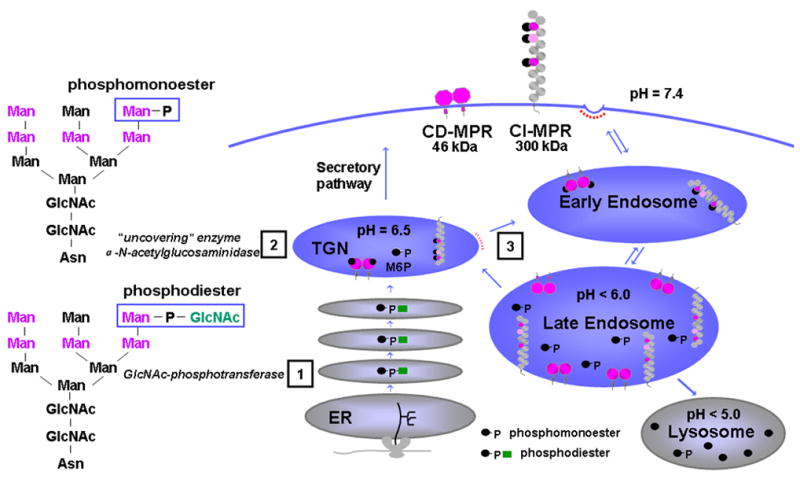

In eukaryotic cells, mannose 6-phosphate receptors (MPRs) mediate the delivery of ~60 different newly synthesized soluble acid hydrolases to the lysosome by binding to mannose 6-phosphate (Man-6-P) residues found on their N-linked oligosaccharides. Lysosomal enzymes become differentiated from other proteins in the secretory pathway by acquiring mannose 6-phosphate (Man-6-P) residues in a two step process: 1) The GlcNAc-phosphotransferase transfers N-acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate to one or two mannose residues on an N-glycan to yield a phosphodiester intermediate [1,2]. 2) α-N-acetylglucosaminidase removes the N-acetylglucosamine residue in the trans Golgi network (TGN) to generate the phosphomonoester, Man-6-P [3] (Figure 1). The resulting MPR/lysosomal enzyme complex is transported from the TGN to the late endosome where the low pH of the compartment induces the complex to dissociate. The released enzymes are packaged into lysosomes [4,5] and the receptors either return to the Golgi to repeat the process or move to the plasma membrane where they function to internalize exogenous ligands (Figure 1). The importance of this phosphomannosyl recognition system in the biogenesis of lysosomes is illustrated by the existence of over 40 different human lysosomal storage diseases that are estimated to affect 1 in 5,000 live births [6]. The discovery of the MPRs originated from studies centered on determining the molecular basis of a lysosomal storage disorder, mucolipidosis II (MLII; also referred to as “I-cell disease”). The pioneering work of Hickman and Neufeld [7] led to the finding that fibroblasts from MLII patients were capable of internalizing lysosomal enzymes secreted by normal cells, while in contrast, normal fibroblasts were unable to endocytose lysosomal enzymes secreted by MLII fibroblasts. Their hypothesis that lysosomal enzymes contained a recognition tag required for receptor-mediated uptake and transport to lysosomes was later confirmed upon the identification of the tag as Man-6-P [8–10]. I-cell disease is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a deficiency of GlcNAc-phosphotransferase activity (IUBMB accession number EC 2.7.8.17), which is the enzyme that generates the Man-6-P tag [11] (see Figure 1, Step 1).

Figure 1.

Lysosomal enzyme trafficking. Movements of lysosomal enzymes and MPRs between the various intracellular compartments and the cell surface are shown. Phosphorylation of mannose residues on N-linked oligosaccharides occurs in two steps (see text). The five potential sites of phosphorylation are indicated in pink letters. Lysosomal enzymes that acquire the Man-6-P tag in early Golgi compartments bind specifically to MPRs in the Golgi. The resulting receptor-lysosomal enzyme complex is transported from the trans Golgi network (TGN) to an early endosomal compartment (step 3) and to an acidified late endosomal compartment where the low pH of the compartment causes dissociation of the complex. Lysosomal enzymes that are not phosphorylated (•), contain a phosphomonoester (•-P), or contain a diester with N-acetyl glucosamine are shown (•-P- ). The dimeric CD-MPR is depicted as two pink balls and the CI-MPR is shown as 15 repeating balls. The three Man-6-P binding domains of the CI-MPR are depicted as pink balls.

). The dimeric CD-MPR is depicted as two pink balls and the CI-MPR is shown as 15 repeating balls. The three Man-6-P binding domains of the CI-MPR are depicted as pink balls.

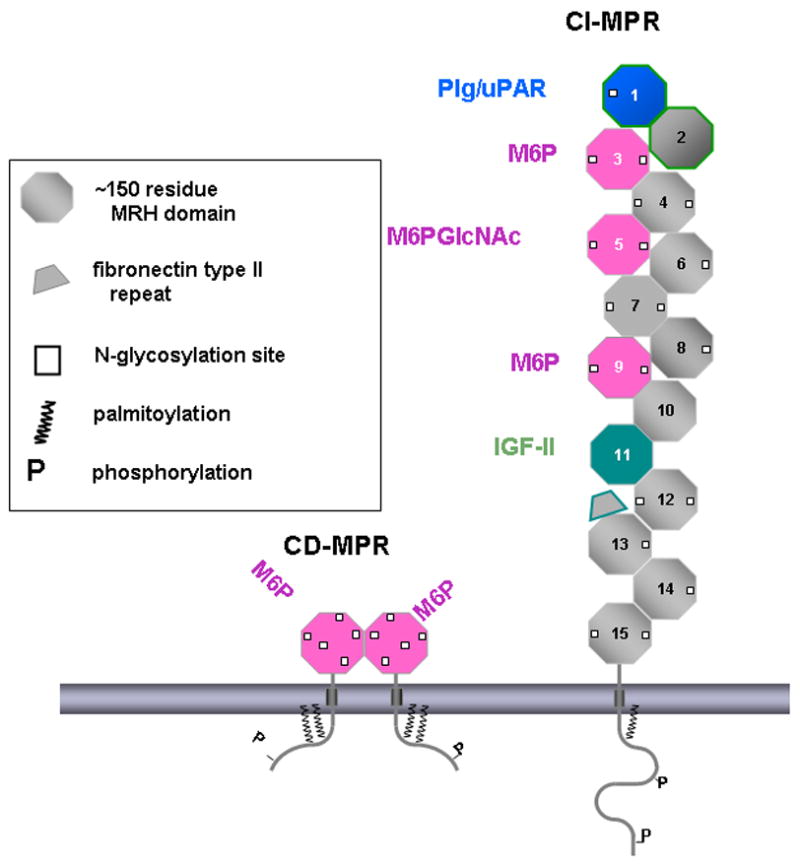

Two distinct MPRs, the 46 kDa cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (CD-MPR) and the ~300 kDa cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (CI-MPR) are the sole members of the P-type lectin family [12]. The CI-MPR is multifunctional in that it binds proteins bearing the Man-6-P recognition marker as well as the peptide hormone IGF-II (hence it is also called IGFIIR/CI-MPR) [13–15]. In addition to its intracellular role in lysosome biogenesis and regulation of circulating IGF-II levels, the CI-MPR has been implicated in many other cellular functions due to the fact that it binds to Man-6-P-containing proteins that are not lysosomal hydrolases. These include transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) precursor [16], the placental angiogenic hormone proliferin [17], the cytokine leukemia inhibitory factor [18], and the T-cell activation antigen CD26 [19], to name just a few. Functional roles of the cell surface CI-MPR in interactions with these non-lysosomal proteins include activation of TGF-β precursor and renin precursor [20] and clearance from the plasma in the case of leukemia inhibitory factor [21]. In addition to IGF-II, the CI-MPR has been shown to interact with a number of proteins that do not have phosphomannosyl residues. These include urokinase-type plasminogenactivator receptor (uPAR) [22], plasminogen [23], retinoic acid [24], and heparanase [25]. Residues essential for uPAR and plasminogen binding have been mapped to domain 1 [26] (Figure 2). However, the nature of their interactions is not clear.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the CD-MPR (left) and CI-MPR (right). The MPRs are transmembrane glycoproteins. Various post-translational modifications are indicated, including palmitoylation and phosphorylation. The CD-MPR is shown as a dimer with each subunit having one Man-6-P binding site. The 15 repeating domains of the CI-MPR are numbered sequentially from the N-terminus to C-terminus. Domains 3, 5, and 9 bind Man-6-P with domain 5 preferentially binding to phosphodiesters. Domain 1 is known to bind to urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) and plasminogen (Plg). Domain 11 binds IGF-II and Domain 13 has a fibronectin II insert.

In addition to the two MPRs, several proteins have been identified as containing mannose 6-phosphate receptor homology (MRH) domains [27], including erlectin (a luminal ER protein implicated in the regulation of glycoprotein trafficking) [28], the β-subunit of glucosidase II (also in ER), and GlcNAc-phosphotransferase γ-subunit (in Golgi), all of which are implicated in N-glycan recognition [29]. However, studies on their recognition of specific glycans are only beginning to emerge. Recently, human OS-9, which is involved in ER protein quality control, has been shown to interact with mannose-trimmed N-glycans [30]. However, studies will be needed to verify that the MRH domains of these proteins are structurally related to the MPRs.

This review will focus on recent structural studies of the CD-MPR and CI-MPR, with emphasis on how these receptors interact with phosphomannosyl residues. For other aspects of MPRs and related proteins, the reader is referred to articles by Ghosh et al.[31], Gary-Bobo, et al. [32], Dahms et al. [33], and Brown et al.[34].

Structures of the CD-MPR and CI-MPR

The MPRs are type 1 transmembrane glycoproteins (Figure 2). The CD-MPR forms a stable homodimer and the CI-MPR exists most likely as a dimer [35]. The bovine CD-MPR is composed of a 28-residue amino-terminal signal sequence, a 159-residue extracytosolic domain, a 25-residue transmembrane region, and a 67-residue carboxyl-terminal cytosolic domain. The six cysteine residues in the extracellular region of the CD-MPR form three disulfide linkages that play an important role in the folding of the molecule. The bovine CI-MPR contains a 44-residue signal sequence, a 2,269-residue extracytosolic region, a 23-residue transmembrane region, and a 163-residue cytosolic domain. The large extracytosolic region consists of 15 contiguous domains, each of which, when compared to CD-MPR and to each other, has a similar size and significant amino acid sequence identity (14–38 %) including cysteine distribution, strongly suggesting that they have similar tertiary structures. Indeed, the crystal structures of the extracytosolic domain of the CD-MPR and domains 1, 2, 3, 11, 12, 13, and 14 of the CI-MPR all have the same fold (Figure 3) [36–39] (see below).

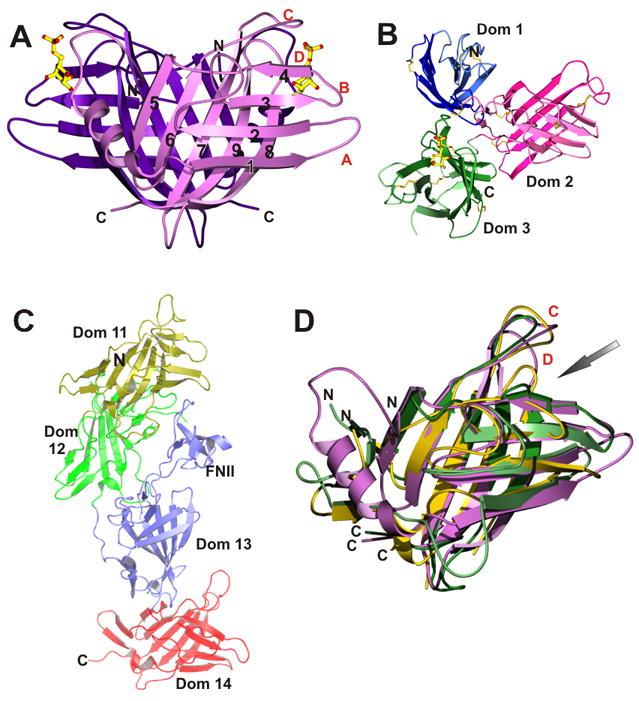

Figure 3.

A collage of structures of the CD-MPR and CI-MPR. A) Dimer of the CD-MPR. β-Strands are numbered from N- to C- terminus and loops between strands are labeled in alphabetic order. B) Structure of domains 1–3 of CI-MPR, with bound Man-6-P in domain 3. C) Structure of domains 11–14 of the CI-MPR. N- and C-termini are indicated. FNII denotes the fibronectin II insert in domain 13. D) Superposition of the structures of the CD-MPR (monomer, purple) and domains of 3 (green) and 11 (gold) of the CI-MPR, demonstrating that they all have a similar polypeptide fold. For clarity, the structures of domains 1, 2, 12, 13, and 14, whose structures have been determined to have the same fold, are not included in the overlay. The ligand binding site is indicated with an arrow.

The structure of the extracytosolic domain of the CD-MPR in complex with Man-6-P and Mn2+ was first determined over 10 years ago [40,41] and has established the overall polypeptide fold of each domain in the P-type lectin family (Figure 3A). The molecule was found to be a dimer, consistent with the predominant oligomeric form of the CD-MPR found in membranes. The overall fold of the CD-MPR monomer is that of a flattened β-barrel consisting of two antiparallel β-sheets, one with four β-strands and the other with five strands, with strand 9 interjecting between strands 7 and 8. The dimer interface is formed by two five-stranded β-sheets. The structure of domains 1-3 (the N-terminal 432 residues) of the CI-MPR has been determined in complex with Man-6-P [36,42], confirming that the overall fold of each domain in the CI-MPR is the same as that of the CD-MPR (Figure 3). While the CD-MPR forms a dimer, the N-terminal three domains of the CI-MPR exist as a monomer. The three domains of the CI-MPR form a compact tri-lobed disk and have considerable contact with one another (contact areas between domains range from 8 to 22 %). These extensive interactions suggest that the observed three-domain arrangement forms a structural unit within the entire CI-MPR molecule[36], and that the interactions of domain 3 with the loop between domains 1 and 2 are required for maintaining the architecture of its sugar binding site.

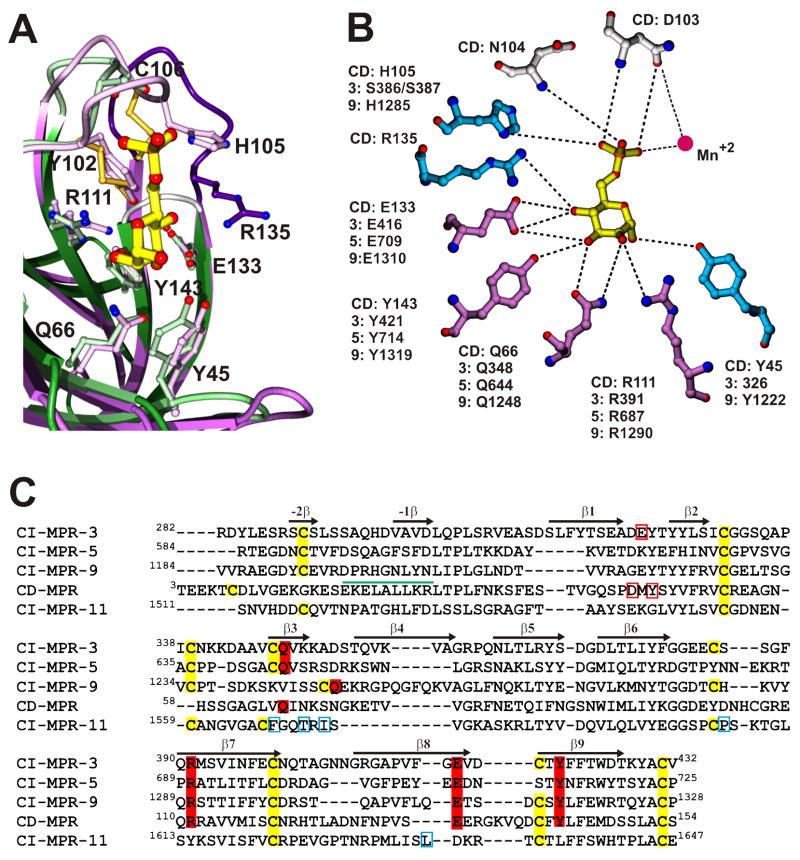

Comparison of Man-6-P binding pockets in the CD-MPR and CI-MPR

The Man-6-P binding site in the CD-MPR is located at the C-terminal opening of the β-barrel (Figures 3 and 4). One side of the binding pocket is walled off by two loops (loop C, residues G98 – R108; loop D, E134 – C141) and the other side is exposed to the solvent, to provide room for the rest of the ligand molecule. The pocket is lined with residues Y45, D103, N104, H105, R135, E133, Y143, Q66, and R111, the latter four of which are found to be essential for Man-6-P binding by mutagenesis studies of CD-MPR [43–45] and domains 3, 5, and 9 of the CI-MPR [46,47] (Figure 4B). These four signature residues in both the CD-MPR (E133, Y143, Q66, and R111) and domain 3 of CI-MPR (E416, Y421, Q348, and R391) are absolutely conserved (Figure 4C) and interact with the Man-6-P ligand in the same manner, strongly suggesting that the sugar-binding pockets in domains 5 and 9 are also very similar to those of CD-MPR and domain 3 of the CI-MPR (Figure 4A). Indeed, the Man-6-P binding pocket located in domain 3 is essentially the same as that of the CD-MPR, with one exception: the absence of Mn2+ which accounts for the metal independence of the CI-MPR. In addition, solution structures of domain 5, which preferentially binds phosphodiesters, with and without a phosphodiester ligand have been determined (L Olson, abstract 216 in Glycobiology 18, 993, 2008). Preliminary results indicate that the overall fold of the isolated domain 5 is similar to that of the other CI-MPR domains and CD-MPR, and mutagenesis studies have demonstrated the essential role of these four signature residues in the lectin activity of domain 5 [47]. It is interesting to note that the IGF-II binding pocket is located in the homologous position in domain 11 as the Man-6-P binding pocket in domain 3 [37] (Figure 3D).

Figure 4.

Conservation of the Man-6-P binding site and essential residues for carbohydrate binding. A) Superposition of the Man-6-P binding sites of the CD-MPR (purple) and domain 3 of the CI-MPR (green). The architecture of both binding pockets is essentially the same with the exception of loop D (dark blue, CD-MPR; grey, domain 3), which is shorter in domain 3. B) A schematic drawing showing interactions between Man-6-P and residues in the CD-MPR and their homologous residues in domains 3, 5, and 9 of the CI-MPR. Dotted lines indicate potential hydrogen bonds. Mutational studies have shown that the four residues shown in purple are essential for Man-6-P binding and that mutation of the residues shown in blue partially decreased Man-6-P binding affinity. The two residues in grey have not been tested. C) Sequence alignment of domains 3, 5, 9 and 11 of the CI-MPR and the extracytosolic domain of the CD-MPR. The conserved cysteines are highlighted in yellow and the four residues that are essential for Man-6-P binding are highlighted in red. Residues that are within hydrogen bonding distance of Man-6-P in the crystal structures of CD-MPR and domains 1–3 of the CI-MPR, but found to be not essential for Man-6-P binding are boxed in red. Secondary structural elements are indicated with arrows and the single α-helix found in the CD-MPR is indicated with a green cylinder. Residues involved in IGF-II binding in domain 11 of the CI-MPR are boxed in blue.

Inhibition studies using chemically synthesized oligomannosides or neoglycoproteins have shown that the presence of Man-6-P at a terminal position is the major determinant of receptor binding. Furthermore, linear glycans which contain a terminal Man-6-P linked α1,2 to the penultimate mannose were shown to be the most potent inhibitors [48,49]. Recent studies using a novel Phosphorylated Glycan Microarray demonstrate that the CD-MPR demonstrates a preference for glycans containing two phosphomonoesters, whereas the CI-MPR shows little difference in affinity toward glycans containing one or two phosphomonoesters (X Song et al., unpublished).

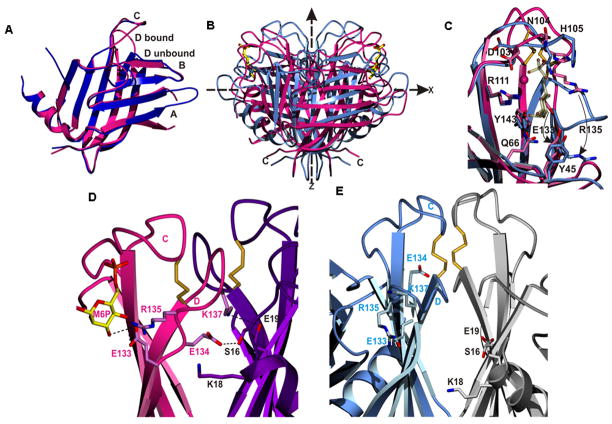

The CD-MPR is dynamic – comparison of the ligand-bound and ligand-free CD-MPR

The MPRs travel between various cellular compartments during the transportation of their ligand, from TGN (where they bind the ligand) to late endosomes (where they release the ligand). Unlike the CI-MPR, the CD-MPR does not bind ligands at the cell surface. It has been shown that this loading/unloading is facilitated by changes in the pH of each compartment [50]. In order to understand the mechanism of the pH dependence of the ligand binding/release, crystal structures of the CD-MPR have been obtained at various pHs and in the presence and absence of bound Man-6-P [51,52]. Unexpectedly, regardless of pH, the receptor molecule adopts two conformations: an “open” conformation found in all structures with bound Man-6-P and a “closed” conformation observed in all structures without bound ligand (Figure 5). There are three major structural differences between these two states. First, in the open state (i.e., the bound state), the two ligand-binding sites of the dimeric molecule are ~35Å apart, whereas in the closed (unliganded) state, they are ~26 Å apart. Second, the architecture of the ligand binding pocket in the closed form differs significantly from the open form (Figure 5B). When the ligand is bound, loop D (residues E134-C141) forms one wall of the binding pocket. When the ligand is absent, loop D folds into the binding pocket, occupying the same space where the sugar molecule binds and thereby keeps the position of the sugar-binding residues unchanged. Lastly, this loop D movement disrupts electrostatic interactions between the two subunits, releasing inter-subunit salt bridges, causing the two subunits to slide and twist at their interface which results in the “closed” form (Figures 5B and 5C). Thus, the movements involved in the bound-to-unbound transition of the CD-MPR are reminiscent of those in the oxy-to-deoxy transition of hemoglobin. However, whether the CD-MPR has ligand-binding cooperativity has not been studied. The overall movement of the bound-to-unbound transition can be described as a “scissoring and twisting” motion between the two subunits at the dimer interface. The implication of the existence of these two states is that the CD-MPR must be able to readily transition between these two conformations as it travels to the different cellular compartments, with the unique environment of each compartment (e.g., Golgi, cell surface, endosome) impacting the equilibrium between the two states.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the ligand-bound and ligand-free structures of CD-MPR. A) Superposition of the monomer structures of the bound (red) and unbound (blue) structures. Note the difference in the conformations of loop D. B) The dimer structures, with the same color scheme as in (A). The molecule is scissoring along its molecular two-fold axis (z-axis) and twisting along the x-axis. The ligand, Man-6-P, is shown with ball-and-sticks. C) Superposition of the ligand binding sites of the bound (red) and unbound (blue) structures. Loop D in the bound structure forms the side of the binding pocket, while in the unbound structure loop D folds down and occupies the Man-6-P binding site. Mn+2 ion in the bound state is denoted as a red ball. The movements of E133 and R135 are indicated (curved arrows). Inter-subunit interfaces are shown, including the N-terminus and loop D of the bound (panel D) and unbound (panel E) structures. Electrostatic interactions found between the two subunits in the bound structure are disrupted in the unbound structure, resulting in a weaker dimer interface.

Mechanisms of ligand binding and release by the CD-MPR

From the above structural studies, plausible mechanisms for the dissociation of lysosomal enzymes in the acidic endosome (pH, < 6.0) and at the cell surface (pH, 7.4) have been proposed [52]. The structure of the bound form of CD-MPR has three inter-subunit ion pairs that “tie” loop D of one subunit to the other subunit (K18 and E19 of one subunit to E134 and K138 of the other subunit, respectively) (Figure 5D). In the acidic environment of the endosome, the disruption of inter-subunit electrostatic interactions may trigger the ligand release by protonation of the carboxyl groups of the glutamates and aspartate (Figures 5D and 5E). In addition, E133, one of the essential residues for binding of Man-6-P, might also be protonated in the endosome and weaken its binding to Man-6-P, promoting release of the bound ligand (Figure 5D). On the other hand, at the cell surface, deprotonation of H105 and the phosphate moiety of Man-6-P (both of which interact with each other in the bound conformation) are most likely responsible for the release of the ligand (Figures 4 and 5C). To probe directly the role of the electrostatic interactions between the two subunits, specifically the salt-bridge between E19 and K137, a double mutant (E19Q/K137M) has been analyzed by surface plasmon resonance. The mutant CD-MPR lacking the inter-subunit salt bridge binds lysosomal enzymes with ~100-fold lower affinity, clearly demonstrating the critical role of the ionic interactions between the two subunits in stabilizing the bound conformer of the CD-MPR.

Conclusions

Although we have accumulated considerable knowledge on the MPRs regarding the structural basis for their phosphomannosyl recognition and the mechanisms of the cargo loading and unloading for the CD-MPR, there still remain many outstanding questions. It is interesting to note that all ligand binding sites of CI-MPR are located at odd-numbered domains, i.e., domains 3, 5, and 9 for Man-6-P binding and domain 11 for IGF-II, as well as domain 1 which is found to interact with plasminogen and uPAR. What are the roles of the remaining domains? Do even-numbered domains function only as spacers and/or support for the functional domains? What are the mechanisms of ligand binding and release for the CI-MPR, which must be very different from those of CD-MPR? Answers to these questions must await further biochemical and structural studies of the CI-MPR including fragments containing overlapping ranges of domains. It is also intriguing that the CI-MPR complements the two enzymes that make the phosphomannosyl tag by being able to bind to the products of both the first and the second enzymes of the two-step process. Is this purely for redundancy? Furthermore, the mechanisms that govern the MPRs’ trafficking to different subcellular compartments are not clearly known. MPRs are present in TGN, endosomes, and plasma membrane, but absent in lysosomes. They cycle constitutively between these compartments and this trafficking is directed by sorting signals that reside in the cytosolic tails of the receptors. Currently, only the structures of peptides (12 or 13 residues) that contain the di-leucine motif in the cytosolic tails of CD-MPR and CI-MPR, in complex with the VHS domain of human GGA (Golgi-localized, -γ-ear-containing, ADP-ribosylating-factor-binding) proteins are known [53,54]. Thus, in order to gain a clearer picture of the factors that regulate the interaction of the MPRs’ cytoplasmic region with numerous cytosolic adaptor proteins, further structural analyses are needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant DK42667 to N.M.D and J-J. P. Kim.

- MPR

mannose 6-phosphate receptor

- CD-MPR

cation-dependent MPR

- CI-MPR

cation-independent MPR

- Man-6-P

mannose 6-phosphate

- TGN

trans Golgi network

- MRH

MPR homology

- uPAR

urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

• Of special interest

•• Of outstanding interest

- 1•.Gelfman CM, Vogel P, Issa TM, Turner CA, Lee WS, Kornfeld S, Rice DS. Mice lacking alpha/beta subunits of GlcNAc-1-phosphotransferase exhibit growth retardation, retinal degeneration, and secretory cell lesions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:5221–5228. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0452. GlcNac-1 phosphotransferase catalyzes the first step of the two step process in the acquisition of mannose 6-phosphate on N-linked oligosaccharides of lysosomal enzymes. Mice deficient in the phosphotransferase gene exhibit severe retinal degeneration in addition to the features observed in patients with mucolipidosis II. Authors suggest a connection between retinal diseases and lysosomal storage disorders via GlcNac-phosphotransferase. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2•.Lee WS, Payne BJ, Gelfman CM, Vogel P, Kornfeld S. Murine UDP-GlcNAc:lysosomal enzyme N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase lacking the gamma-subunit retains substantial activity toward acid hydrolases. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27198–27203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704067200. Together with Ref. 1, this article characterizes the phosphotransferase. The paper shows that the α/βsubunits of the enzyme, in addition to their catalytic function, have some ability to recognize acid hydrolases as specific substrates. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varki A, Sherman W, Kornfeld S. Demonstration of the enzymatic mechanisms of alpha-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-1-phosphodiester N-acetylglucosaminidase (formerly called alpha-N-acetylglucosaminylphosphodiesterase) and lysosomal alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase. Archives of Biochemistry & Biophysics. 1983;222:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Borgne R, Hoflack B. Protein transport from the secretory to the endocytic pathway in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1404:195–209. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullins C, Bonifacino JS. The molecular machinery for lysosome biogenesis. Bioessays. 2001;23:333–343. doi: 10.1002/bies.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ. Lysosomal storage disorders: emerging therapeutic options require early diagnosis. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2003;162:S34–S37. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1348-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hickman S, Neufeld EF. A hypothesis for I-cell disease: defective hydrolases that do not enter lysosomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;49:992–999. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan A, Fischer D, Achord D, Sly W. Phosphohexosyl recognition is a general characteristic of pinocytosis of lysosomal glycosidases by human fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1977;60:1088–1093. doi: 10.1172/JCI108860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Distler J, Hieber V, Sahagian G, Schmickel R, Jourdian GW. Identification of mannose 6-phosphate in glycoproteins that inhibit the assimilation of beta-galactosidase by fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4235–4239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natowicz MR, Chi MM, Lowry OH, Sly WS. Enzymatic identification of mannose 6-phosphate on the recognition marker for receptor-mediated pinocytosis of beta-glucuronidase by human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4322–4326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reitman ML, Kornfeld S. Lysosomal enzyme targeting. N-Acetylglucosaminylphosphotransferase selectively phosphorylates native lysosomal enzymes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1981;256:11977–11980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drickamer K, Taylor ME. Biology of animal lectins. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:237–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacDonald RG, Pfeffer SR, Coussens L, Tepper MA, Brocklebank CM, Mole JE, Anderson JK, Chen E, Czech MP, Ullrich A. A single receptor binds both insulin-like growth factor II and mannose-6-phosphate. Science. 1988;239:1134–1137. doi: 10.1126/science.2964083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt B, Kiecke-Siemsen C, Waheed A, Braulke T, von Figura K. Localization of the insulin-like growth factor II binding site to amino acids 1508–1566 in repeat 11 of the mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:14975–14982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahms NM, Wick DA, Brzycki-Wessell MA. The bovine mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor. Localization of the insulin-like growth factor II binding site to domains 5–11. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:3802–3809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purchio AF, Cooper JA, Brunner AM, Lioubin MN, Gentry LE, Kovacina KS, Roth RA, Marquardt H. Identification of mannose 6-phosphate in two asparagine-linked sugar chains of recombinant transforming growth factor-beta 1 precursor. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:14211–14215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SJ, Nathans D. Proliferin secreted by cultured cells binds to mannose 6-phosphate receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:3521–3527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanchard F, Raher S, Duplomb L, Vusio P, Pitard V, Taupin JL, Moreau JF, Hoflack B, Minvielle S, Jacques Y, et al. The mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor is a nanomolar affinity receptor for glycosylated human leukemia inhibitory factor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20886–20893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikushima H, Munakata Y, Ishii T, Iwata S, Terashima M, Tanaka H, Schlossman SF, Morimoto C. Internalization of CD26 by mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor contributes to T cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8439–8444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Kesteren CA, Danser AH, Derkx FH, Dekkers DH, Lamers JM, Saxena PR, Schalekamp MA. Mannose 6-phosphate receptor-mediated internalization and activation of prorenin by cardiac cells. Hypertension. 1997;30:1389–1396. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanchard F, Duplomb L, Raher S, Vusio P, Hoflack B, Jacques Y, Godard A. Mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor mediates internalization and degradation of leukemia inhibitory factor but not signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24685–24693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nykjaer A, Christensen EI, Vorum H, Hager H, Petersen CM, Roigaard H, Min HY, Vilhardt F, Moller LB, Kornfeld S, et al. Mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor-II receptor targets the urokinase receptor to lysosomes via a novel binding interaction. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:815–828. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godar S, Horejsi V, Weidle UH, Binder BR, Hansmann C, Stockinger H. M6P/IGFII-receptor complexes urokinase receptor and plasminogen for activation of transforming growth factor-beta1. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1004–1013. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199903)29:03<1004::AID-IMMU1004>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang JX, Li Y, Leaf A. Mannose-6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor-II receptor is a receptor for retinoic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13671–13676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25•.Wood RJ, Hulett MD. Cell surface-expressed cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (CD222) binds enzymatically active heparanase independently of mannose 6-phosphate to promote extracellular matrix degradation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4165–4176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708723200. Purified platelet heparanase was shown to bind the human CI-MPR expressed on the surface of a transfected mouse L cell line, demonstrating that the CI-MPR is a cell surface receptor for heparanase and its binding to the receptor is independent of mannose 6-phospate binding. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leksa V, Godar S, Cebecauer M, Hilgert I, Breuss J, Weidle UH, Horejsi V, Binder BR, Stockinger H. The N terminus of mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor in regulation of fibrinolysis and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40575–40582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207979200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dodd RB, Drickamer K. Lectin-like proteins in model organisms: implications for evolution of carbohydrate-binding activity. Glycobiology. 2001;11:71R–79R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.5.71r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cruciat CM, Hassler C, Niehrs C. The MRH Protein Erlectin Is a Member of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Synexpression Group and Functions in N-Glycan Recognition. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:12986–12993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511872200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munro S. The MRH domain suggests a shared ancestry for the mannose 6-phosphate receptors and other N-glycan-recognising proteins. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R499–501. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30•.Hosokawa N, Kamiya Y, Kamiya D, Kato K, Nagata K. Human OS-9, a lectin required for glycoprotein ERAD, recognizes mannose-trimmed N-glycans. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809725200. A new member of the MRH family, human OS-9, has been studied for its carbohydrate specificity and the results suggest that human OS-9 specifically binds N-glycans that lack the terminal mannose from the C-branch. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31•.Ghosh P, Dahms NM, Kornfeld S. Mannose 6-phosphate receptors: new twists in the tale. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:202–213. doi: 10.1038/nrm1050. An older but still excellent review on the transport of acid hydrolases from the trans Golgi network to lysosomes in mammalian cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32••.Gary-Bobo M, Nirde P, Jeanjean A, Morere A, Garcia M. Mannose 6-phosphate receptor targeting and its applications in human diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2945–2953. doi: 10.2174/092986707782794005. This review focuses on the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor, highlighting the synthesis and potential use of high affinity mannose 6-phosphate analogues that can target this receptor. These analogues could be used for the delivery of specific compounds to lysosomes to be used in enzyme replacement therapies of lysosomal diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33••.Dahms NM, Olson LJ, Kim JJ. Strategies for carbohydrate recognition by the mannose 6-phosphate receptors. Glycobiology. 2008;18:664–678. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn061. This is a comprehensive review of the two mannose 6-phosphate receptors regarding their functions, structures, and their ligand specificities. The review also discusses evolutionary aspect of the receptors and other members of the MRH family. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34••.Brown J, Jones EY, Forbes BE. Interactions of IGF-II with the IGF2R/cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor mechanism and biological outcomes. Vitam Horm. 2009;80:699–719. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(08)00625-0. A review focused on molecular interactions between the IGF-IIR/CI-MPR and IGF-II and other ligands, highlighting the recent structural analyses of domains 11–14 with and without bound IGF-II. Also detailed discussion of the underlying mechanism of action of the IGF-IIR/CI-MPR is presented. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartman MA, Kreiling JL, Byrd JC, MacDonald RG. High-affinity ligand binding by wild-type/mutant heteromeric complexes of the mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor. Febs J. 2009;276:1915–1929. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olson LJ, Yammani RD, Dahms NM, Kim JJ. Structure of uPAR, plasminogen, and sugar-binding sites of the 300 kDa mannose 6-phosphate receptor. EMBO Journal. 2004;23:2019–2028. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37••.Brown J, Delaine C, Zaccheo OJ, Siebold C, Gilbert RJ, van Boxel G, Denley A, Wallace JC, Hassan AB, Forbes BE, et al. Structure and functional analysis of the IGF-II/IGF2R interaction. EMBO J. 2008;27:265–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601938. Crystal structures of IGF-IIR/cation-independent mannose6-phosphate receptor domains 11–12, 12-13-14, and domains 11-12-13/IGF-II complex are described. The structures reveal that each domain has the same polypeptide fold as that of domains 1-2-3 and extracytosolic domain of the cation-dependent receptor. The complex structure combined with mutagenesis analyses reveals the IFG-II binding hotspot on the receptor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uson I, Schmidt B, von Bulow R, Grimme S, von Figura K, Dauter M, Rajashankar KR, Dauter Z, Sheldrick GM. Locating the anomalous scatterer substructures in halide and sulfur phasing. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2003;59:57–66. doi: 10.1107/s090744490201884x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown J, Esnouf RM, Jones MA, Linnell J, Harlos K, Hassan AB, Jones EY. Structure of a functional IGF2R fragment determined from the anomalous scattering of sulfur. Embo J. 2002;21:1054–1062. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts DL, Weix DJ, Dahms NM, Kim J-JP. Molecular basis of lysosomal enzyme recognition: three-dimensional structure of the cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Cell. 1998;93:639–648. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olson LJ, Zhang J, Lee YC, Dahms NM, Kim J-JP. Structural basis for recognition of phosphorylated high mannose oligosaccharides by the cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:29889–29896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olson LJ, Dahms NM, Kim JJ. The N-terminal carbohydrate recognition site of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:34000–34009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wendland M, Waheed A, von Figura K, Pohlmann R. Mr 46,000 mannose 6-phosphate receptor. The role of histidine and arginine residues for binding of ligand. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:2917–2923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olson LJ, Hancock MK, Dix D, Kim J-JP, Dahms NM. Mutational analysis of the binding site residues of the bovine cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:36905–36911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.36905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun G, Zhao H, Kalyanaraman B, Dahms NM. Identification of residues essential for carbohydrate recognition and cation dependence of the 46-kDa mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Glycobiology. 2005;15:1136–1149. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hancock MK, Haskins DJ, Sun G, Dahms NM. Identification of residues essential for carbohydrate recognition by the insulin-like growth factor II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11255–11264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47•.Chavez CA, Bohnsack RN, Kudo M, Gotschall RR, Canfield WM, Dahms NM. Domain 5 of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor preferentially binds phosphodiesters (mannose 6-phosphate N-acetylglucosamine ester) Biochemistry. 2007;46:12604–12617. doi: 10.1021/bi7011806. Mutations of domain 5 of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor were studied by surface plasmon resonance analyses, demonstrating that domain 5 is unique among lectins due to its ability to bind phosphodiesters. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Distler JJ, Guo JF, Jourdian GW, Srivastava OP, Hindsgaul O. The binding specificity of high and low molecular weight phosphomannosyl receptors from bovine testes. Inhibition studies with chemically synthesized 6-O-phosphorylated oligomannosides. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:21687–21692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomoda H, Ohsumi Y, Ichikawa Y, Srivastava OP, Kishimoto Y, Lee YC. Binding specificity of D-mannose 6-phosphate receptor of rabbit alveolar macrophages. Carbohydrate Research. 1991;213:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90596-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imort M, Zuhlsdorf M, Feige U, Hasilik A, von Figura K. Biosynthesis and transport of lysosomal enzymes in human monocytes and macrophages. Effects of ammonium chloride, zymosan and tunicamycin. Biochemical Journal. 1983;214:671–678. doi: 10.1042/bj2140671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olson LJ, Zhang J, Dahms NM, Kim J-JP. Twists and turns of the CD-MPR: ligand-bound versus ligand-free receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10156–10161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52••.Olson LJ, Hindsgaul O, Dahms NM, Kim JJ. Structural Insights into the Mechanism of pH-dependent Ligand Binding and Release by the Cation-dependent Mannose 6-Phosphate Receptor. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10124–10134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708994200. Crystal structures of the cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate receptor at various pHs and with and without mannose 6-phosphate (ligand) were determined, demonstrating that the molecule is dynamic and is able to transition between two stable conformations. The paper presents detailed description of the mechanisms of ligand binding and release by the receptor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Misra S, Puertollano R, Kato Y, Bonifacino JS, Hurley JH. Structural basis for acidic-cluster-dileucine sorting-signal recognition by VHS domains. Nature. 2002;415:933–937. doi: 10.1038/415933a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shiba T, Takatsu H, Nogi T, Matsugaki N, Kawasaki M, Igarashi N, Suzuki M, Kato R, Earnest T, Nakayama K, et al. Structural basis for recognition of acidic-cluster dileucine sequence by GGA1. Nature. 2002;415:937–941. doi: 10.1038/415937a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]