Abstract

It is generally accepted that naturally existing functional domains can serve as building blocks for complex protein structures, and that novel functions can arise from assembly of different combinations of these functional domains. To inform our understanding of protein evolution and explore the modular nature of protein structure, two model enzymes were chosen for study, purT-encoded glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase (PurT) and purK-encoded N5-carboxylaminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase (PurK). Both enzymes are found in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway of Escherichia coli. In spite of their low sequence identity, PurT and PurK share significant similarity in terms of tertiary structure, active site organization, and reaction mechanism. Their characteristic three domain structures categorize both PurT and PurK as members of the ATP-grasp protein superfamily. In this study, we investigate the exchangeability of individual protein domains between these two enzymes and the in vivo and in vitro functional properties of the resulting hybrids. Six domain-swapped hybrids were unable to catalyze full wild-type reactions, but each hybrid protein could catalyze partial reactions. Notably, an additional loop replacement in one of the domain-swapped hybrid proteins was able to restore near wild-type PurK activity. Therefore, in this model system, domain-swapped proteins retained the ability to catalyze partial reactions, but further modifications were required to efficiently couple the reaction intermediates and achieve catalysis of the full reaction. Implications for understanding the role of domain swapping in protein evolution are discussed.

Keywords: protein evolution, de novo purine biosynthetic pathway, domain swapping

Introduction

Protein modules are stable structural units that either have an independent function or contribute to the function of the whole protein in cooperation with other protein modules. Modules can be defined on several different scales, ranging from linked enzymes down to small structural motifs. In eukaryotes, enzymes that catalyze consecutive reactions tend to form single, multidomain proteins, presumably to protect reactive intermediates and expedite substrate turnover. For example, GAR synthetase, GAR transformylase, and AIR synthetase catalyze the second, third, and fifth steps in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway, respectively.1 These enzymatic activities exist on separate proteins in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, but comprise a single trifunctional protein in human and chicken.2,3 In this example, each linked enzyme can be considered as an individual protein module. Other macromolecules such as collagen and titin obtain unique physical properties critical for their biological functions by forming covalently linked polymers of repetitive subunits4,5 and each of the tethered monomers can be defined as a protein module. On a scale smaller than these large multidomain protein complexes, protein modules can also be defined within individual proteins. The (β/α)8 barrel structure is the most versatile and most frequently encountered fold among enzymes. The unique barrel structure with eight successive strand-loop-helix motifs allows substitution of individual motifs within the barrel, even fragmentation into half barrels without the disruption of functional or structural integrity.6–9 Here, a segment as small as the strand-loop-helix motif can be considered a protein module.

Protein modules can also be considered as evolutionary units.10 It is generally believed that nature evolved novel protein functions through recombination of protein modules taken from a pre-existing repertoire, a process sometimes referred to as “domain shuffling.” Recombination followed by mutational drift can result in higher substrate specificities and enzyme activities in response to selective pressures. Identifying functional protein modules, understanding their reassembly, and determining what additional alterations are required to achieve novel functions will help us to further understand the mechanisms of protein evolution, and to formulate an efficient design methodology for the creation of new enzymes.11

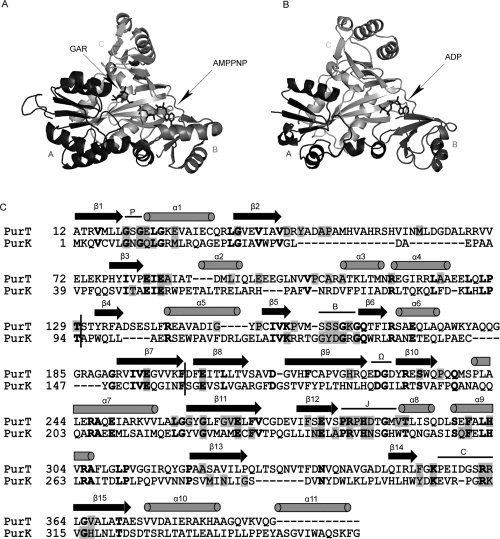

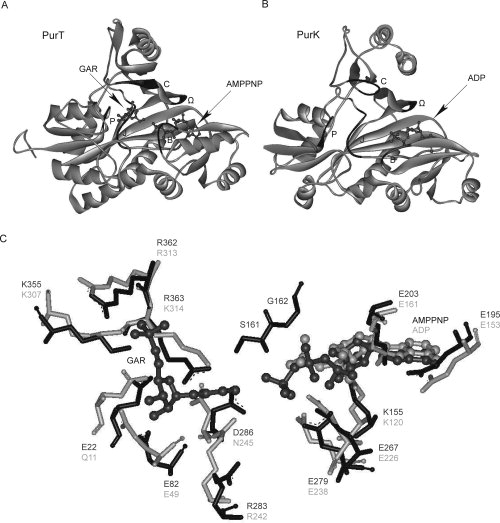

To experimentally investigate how domain swapping may contribute to protein evolution, we chose two enzymes in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway of Escherichia coli, glycinamide ribonucleotide (GAR) formyltransferase (PurT) and N5-carboxylaminoimidazole ribonucleotide (N5-CAIR) synthetase (PurK), as model enzymes. PurT catalyzes the formylation of GAR using ATP and formate, and PurK catalyzes the carboxylation of aminoimidazole ribonucleotide (AIR) to N5-CAIR using ATP and bicarbonate (see Fig. 1). Crystallographic studies and amino acid sequence analysis indicate that both PurT and PurK belong to a newly emerged superfamily of proteins that contain an ATP grasp fold.12 Other members of this protein superfamily include biotin carboxylase,13 carbamoyl phosphate synthetase,14 glutathione synthetase,15 succinyl-CoA synthetase,16 d-alanine:d-alanine ligase,17 and GAR synthetase (PurD), another enzyme in the purine biosynthetic pathway.18 The ATP-grasp proteins, including PurT and PurK, share a similar molecular architecture that consists of three motifs termed the A-, B-, and C-domains (see Fig. 2).20,21 These enzymes also share common features in their reaction mechanisms, notably including formation of reactive acyl phosphate intermediates.12 Despite the low amino acid sequence identity between PurT and PurK (27%), their three-dimensional structures are superimposable with a root-mean-square deviation of 1.1 Å over 177 structurally equivalent α-carbons.21 As shown in Figure 2(C), a majority of the conserved residues involved in substrate binding and/or catalysis are positioned on five structurally conserved loop regions, namely, the P-loop, B-loop, Ω-loop, J-loop, and C-loop. In both PurT and PurK, the residues on the B- and Ω-loop participate in binding ATP. In PurT, GAR is bound in a pocket formed by residues of the P-, J-, and C-loops. At the time this work was initiated, the structure of PurK was only determined in the presence of bound ADP or sulfate, but it is likely that the ribotide substrates for PurT and PurK (GAR and AIR, respectively) bind in similar manners [Fig. 3(C)]. The similarity between a sulfate-bound PurK structure with BC and CPS structures led to the speculation that the residues in the J-loop are involved in binding bicarbonate, formate and the acyl phosphate intermediates.20 The B-loop (also called the T-loop) is also proposed to participate in formate binding and sequestration of reaction intermediates.22

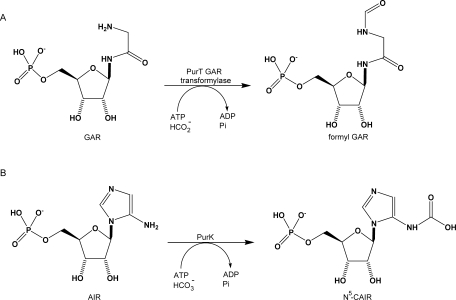

Figure 1.

Reactions catalyzed by PurT transformylase (A) and PurK (B). The common catalytic steps are the formation of an acyl phosphate intermediate upon ATP cleavage, followed by the nucleophilic attack on the carboxyl carbon of the intermediates by the amino nitrogen of the mononucleotides. The intermediates are formyl phosphate for PurT and carboxyl phosphate (or a CO2 breakdown product) for PurK, respectively.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional structures of PurT with GAR and 5′-adenylyl imidodiphosphate (AMPPNP) (A), PurK with ADP (B), and a structure-based sequence alignment (C). In (A) and (B), each enzyme is divided into three structural motifs, the A-, B-, and C-domains which are color-coded in black, dark gray, and gray, respectively. The stick representation of the substrates in complex with enzymes is displayed in dark gray. The representations were prepared with Weblab Viewer Pro 3.7 (Molecular Simulations Inc.). In (C), a structure-based alignment was prepared using CE (combinatorial extension of the optimal path).19 The arrows and cylinders represent the β-sheet and α-helix secondary structures, respectively. Conserved residues in each enzyme are masked in gray and identical residues between PurT and PurK are shown bold. The vertical black bars label the boundaries of the A-, B-, and C-domains. Additionally, five conserved loop regions, the P-loop, B-loop, Ω-loop, J-loop, and C-loop, are labeled.

Figure 3.

Overall architecture of the active sites in PurT (A), PurK (B), and residues within the PurT and PurK active sites (C). In (A) and (B), the B-loop, the Ω-loop, the P-loop, the J-loop, and the C-loop, are shown in black, with the backbones in gray. The GAR, AMPPNP, and ADP molecules are shown in ball-and-stick representation, and colored in dark gray. In (C), the residues involved in substrate binding and catalysis in the PurT (black) and PurK (gray) active sites are shown. Residues are numbered based on the Escherichia coli enzymes. Superpositioning of the PurT and PurK structures was done manually using Weblab Viewer Pro 3.7 (Molecular Simulations Inc.).

In addition to structural homology, PurT and PurK also share common features in their catalytic mechanisms: ATP cleavage, formation of acyl phosphate intermediates, and nucleophilic attack by the substrates' amino groups, all features also shared by other ATP-grasp enzymes. Isotope labeling, positional isotope exchange studies, and tests of chemical and kinetic competence are consistent with formyl phosphate serving as an intermediate in the PurT reaction.23,24 The observation of quantitative 18O transfer from [18O]-bicarbonate into [18O]-Pi by PurK in the presence of AIR and ATP led to the proposal that carboxyl phosphate is an intermediate in the PurK reaction.25 Carboxyl phosphate has not been successfully trapped, most likely due to the low stability of this compound in water (half life <70 ms).26 The structural and mechanistic similarities between PurT and PurK make them attractive model proteins for understanding how enzymatic functions might evolve through domain shuffling.

Our interest in PurT and PurK as a model system was also inspired by previous successful domain swapping between two other proteins in the purine biosynthetic pathway, PurN and PurU.27 PurN, an alternative GAR transformylase that operates by a different mechanism than PurT, catalyzes the transfer of a formyl group from N10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate to the free amino group of GAR to yield formyl-GAR and tetrahydrofolate. PurU, an N10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate hydrolase, hydrolyses N10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate to formate and tetrahydrofolate. Sequence analysis of E. coli purN and purU genes shows a significant amino acid identity (∼60%) in the C-terminal region, in which the N10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate binding pocket of PurN is situated.28,29 Two functional hybrid proteins with PurN activity were created with the C-terminal region of PurN replaced by various lengths of the C-terminal region of PurU,27 and the solubility and specific activity of these hybrids were further improved using a combinatorial mutagenesis approach.30

Herein, we sought to create rationally designed domain-swapped hybrid proteins using a different pair of homologous proteins selected from the purine biosynthetic pathway. Each individual A-, B-, and C-domain in PurT and PurK was substituted by its counterpart from the other protein in order to generate six hybrid proteins. These constructs are characterized by in vivo functional assays and in vitro steady-state kinetics. Although none of the hybrids can catalyze the full reactions seen with wild-type enzymes, they can catalyze partial reactions. Additional loop swapping modifications of the hybrid proteins successfully result in one construct that displays near wild-type PurK activity. Implications for understanding how enzymes may evolve by using domain shuffling are discussed.

Results and Discussion

In vivo activity of the hybrid proteins

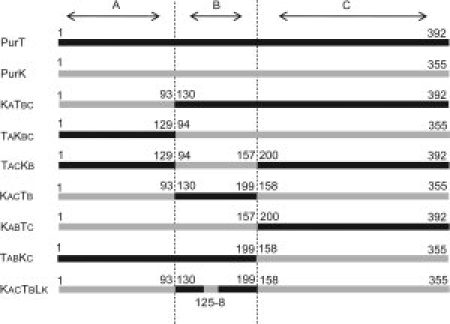

To swap each of the functional domains of PurK and PurT, six chimeric proteins, TAKBC (PurT 1-129 + PurK 94-355), KATBC (PurK 1-93 + PurT 130-392), KACTB (PurK 1-93 + PurT 130-199 + PurK 158-355), TACKB (PurT 1-129 + PurK 94-157 + PurT 200-392), TABKC (PurT 1-199 + PurK 158-355), and KABTC (PurK 1-157 + PurT 200-392), were generated on the basis of structural and sequence alignments between PurK and PurT (see Fig. 4). Each hybrid has one of the A-, B-, or C-domains replaced by the corresponding domain from the other protein.

Figure 4.

Schematic overview of hybrid enzyme composition. The sequences of the two parental genes, PurT and PurK, are depicted in black and gray, respectively. The boundary of each domain is marked by dotted lines. The numbers represent amino acid residue positions in each parental protein.

The functions of the hybrid proteins, as well as the two parental proteins, were initially tested by in vivo complementation in E. coli auxotrophic strains. TX680F′ was used to test for PurT activity,31 and CSH26 for PurK activity.32 With inactivated chromosomal copies of purT and purN, the TX680F′ strain has been shown to detect a GAR transformylase activity ten thousand times less active than wild-type enzyme.31 The limit of detection for the CSH26 strain has not been determined. When bearing plasmids encoding wild-type PurT or PurK enzymes, the TX680F′ and CSH26 strains, respectively, grew reproducibly on minimal medium after a 1 day incubation. In each case, complementation of each deficiency was specific as each wild-type enzyme was only able to support the growth of its respective auxotrophic strain. However, none of the six domain-swapped hybrid proteins described earlier was able to complement the growth of either auxotrophic strain, indicating that these hybrids are either nonfunctional, or that they have activities lower than the detection limit of the in vivo complementation assays.

To improve the in vivo complementation assays, several confounding variables were minimized. Previous results indicated that with low frequency (usually 1 in ∼105) some auxotrophic cells were able to bypass selective pressures and grow on minimal media by recovering their wild-type genes through recombination, a phenomena known as gene reversion. Recombination usually occurs between the inactive chromosomal copy and a gene fragment in the plasmid to provide a fully functional gene. To eliminate background growth caused by gene reversions, two new auxotrophic E. coli strains, PurT(−) and PurK(−), were generated by a complete deletion of the chromosomal purT and purK genes, respectively.33 Variability in protein expression was also considered. In many cases, poor protein expression and/or stability, rather than the lack of the sufficient catalytic activity, can cause a negative result during in vivo complementation assays. The situation is more problematic for hybrid proteins due to the unfavorable interactions likely formed at interfaces between domains derived from different parental proteins—these may lead to incorrect folding and aggregation. Here, hybrids were expressed with an N-terminal maltose binding protein fusion (MBP) and at lower incubation temperatures (25°C) to minimize inclusion body formation. The combination of lower temperatures and the use of N-terminal fusion proteins increased expression levels and solubility of hybrid proteins, as gauged by SDS-PAGE. Expression levels of all test proteins in the auxotrophic strains are in a similar range, also estimated by SDS PAGE. These improvements notwithstanding the six hybrid proteins described earlier do not complement either auxotrophic strain.

Structural and biochemical studies suggest that precise alignments of the three substrate binding pockets is critical for the PurT or PurK reactions to occur, partially due to the fact that the active site is situated at the center of the three domains' interfaces.20,21,23–25 Considering the low amino acid sequence identity (27%) between PurT and PurK, it is likely that unfavorable interactions made between regions in the hybrids that were derived from different parental proteins may disrupt the relative positioning of the three protein modules. Misalignment of the substrate binding pockets could subsequently lead to inefficient coupling of reaction intermediates and a loss of overall catalytic activity. Therefore, the ability of the hybrid proteins to catalyze partial reactions was investigated.

The ATPase activity of wild-type and hybrid proteins

The overall reactions catalyzed by wild-type PurT and PurK can be broken down into three partial reactions: an ATPase activity that cleaves ATP to ADP, a kinase activity that forms the acyl phosphate intermediates (formyl phosphate for PurT and carboxyl phosphate for PurK), and a transferase activity that catalyzes the attack of a mononucleotide on the reactive acyl phosphate intermediate (or, in the case of purK, possibly the CO2 breakdown product). In vivo studies indicate that all of the six hybrid proteins generated by rational domain swapping between PurT and PurK lack the capability to complement auxotrophic strains, which select for the full reaction. However, in vitro studies can reveal whether any of these hybrids can catalyze the ATPase or acyl phosphate-forming partial reactions.

Wild-type PurT and PurK and the six hybrid proteins were overexpressed as N-terminal MBP fusions and purified to homogeneity, as described in Materials and Methods. The kinetic properties of the wild-type enzymes (PurT and PurK) were studied in detail (Table I). With an N-terminal MBP fusion, PurT and PurK still display a dependence of their ATPase activity on the presence of ribonucleotides, GAR for PurT and AIR for PurK (Table II), which has been previously demonstrated using wild-type PurT and PurK constructs that lack the MBP fusion.24,34 However, the catalytic capabilities of both wild-type enzymes were significantly impaired by addition of the N-terminal MBP fusion (Table I). In the most severe case, the kcat value of PurT was lowered ∼19-fold when fused to MBP. Structural and biochemical studies show that wild-type PurT and PurK form homodimers in solution, with oligomerization mediated by the A- and C-domains.20,21,34 It is possible that the MBP domain could disrupt oligomerization and result in a decrease of catalytic activity.

Table I.

Summary of Kinetic Data for PurT, PurK, and the Hybrid Enzyme KABTC

| Enzyme | Km (GAR) (μM) | Km (AIR) (μM) | Km (ATP) (μM) | Km (HCO2−) (μM) | Km (HCO3−) (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (GAR) (μM−1 s−1) | kcat/Km (AIR) (μM−1 s−1) | kcat/Km (HCO2−) (μM−1 s−1) | kcat/Km (HCO3−) (μM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PurTa | 10.1 ± 0.5 | NDb | 45 ± 12 | 319 ± 15 | ND | 37.6 ± 0.8 | 38 | ND | 0.84 | 0.12 |

| PurTc | 36 ± 5 | ND | 85 ± 14 | 1700 ± 310 | ND | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.058 | ND | 0.025 | 1.2×10−3 |

| KABTCc | ND | ND | 1400 ± 300 | ND | ND | (9 ± 0.9)×10−3 | ND | ND | 6.4×10−6 | ND |

| PurKd | ND | 26 | 90 | ND | ND | 52 | ND | 2.0 | 0.58 | ND |

| PurKc | ND | 232 ± 20 | ND | ND | ND | 26.4 ± 1.5 | ND | 0.11 | ND | ND |

Table II.

ATPase Activity of Wild-Type and Hybrid Enzymes

| Specific activity (μmol/min/mg) for production of ADP in the presence of various substratesa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | ATP | ATP HCO3− | ATP AIR | ATP AIR HCO3− | ATP HCO2− | ATP GAR | ATP GAR HCO2− |

| PurT | 0.021 | 0.031 | 0.033 | 0.030 | 0.16 | 4.64 | 5.14 |

| PurK | 0.23 | 1.09 | 8.72 | 10.0 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.40 |

| KATBC | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.61 |

| TAKBC | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.67 |

| TACKB | 0.073 | 0.073 | 0.087 | 0.13 | 0.061 | 0.10 | 0.099 |

| KACTB | 0.028 | 0.026 | 0.053 | 0.077 | 0.022 | 0.033 | 0.037 |

| KABTC | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| TABKC | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.28 |

Specific activities were determined by measuring ATPase activities under saturating concentrations of each substrate. The standard error for each value is less than 20%.

For the two wild-type and six hybrid proteins, all which bear N-terminal MBP fusions, ATPase activities were determined using different combinations of substrates (Table II). Because of the limited availability of substrates, the KM and kcat values for ATPase activity of only one hybrid protein, KABTC, was determined (Table I). Although each of the six hybrids do not catalyze the full wild-type reaction, all hybrids do catalyze the ATPase partial reaction. The observation of ATPase activity in all six hybrid proteins strongly suggest that a functional hybrid ATP binding pocket can be constructed between B- and C-domains taken from different parental proteins. However, catalysis by the hybrid ATP binding pockets is severely impaired. When compared with wild-type enzymes, the ATPase activity of each hybrid protein is typically lower by one or two orders of magnitude. Additionally, the KM value for ATP is increased more than 15-fold in the KABTC hybrid.

The hybrid proteins with the highest ATPase activities, TAKBC and KATBC, only have swapped A-domains. Therefore, the ATP binding pocket in these hybrids is formed by B- and C-domains taken from the same parental protein, and likely form a near-native binding pocket. Hybrid proteins with swapped C-domains, TABKC and KABTC, have ATPase activities about 3–5 fold less active than TAKBC and KATBC, presumably because the ATP binding pocket is distorted due to an imperfect interface formed between the B- and C-domains taken from different parental proteins. Hybrids with the lowest ATPase activity, TACKB and KACTB, are ∼10–20 fold slower than TABKC and KABTC, and have the most potentially disruptive substitutions including a hybrid ATP binding pocket and the insertion of a foreign domain. Interestingly, the comparable ATPase activities exhibited by each pair of hybrid proteins suggest that a similar impact of each domain swap in PurT and PurK is made on the ATPase activity. Unlike wild-type enzymes, the hybrid proteins have lost the dependence of their ATPase activities on the presence of ribonucleotides, suggesting that the observed synergy between ATP and ribonucleotide binding pockets in wild-type proteins is now uncoupled in the hybrids (Table I).

Formation of acyl phosphate intermediates

Like reactions catalyzed by other ATP grasp proteins, the proposed PurT and PurK mechanisms involve formation of an acyl phosphate intermediate. Marolewski and coworkers have shown that during PurT catalysis, formyl phosphate is a chemically and kinetically competent intermediate.23 Notably, the generation of formyl phosphate was detected by using a PurT mutant with a single mutation, G162I. G162 is located on the B-loop (also called the T-loop) of PurT, which contains residues that interact with the phosphate groups of ATP. In wild-type PurT, the formyl phosphate intermediate is well protected in the active site. However, the G162I mutation is proposed to disrupt the B-loop structure and lead to dissociation of formyl phosphate into solution, enabling its detection. In addition to the biologically relevant transformation of GAR into formyl GAR, PurT can catalyze a related reaction. In the absence of GAR, PurT can catalyze the conversion of ATP and acetate to form acetyl phosphate. This observed reaction is also consistent with the proposal of an acyl phosphate reaction intermediate. In wild-type PurK, the proposed carboxyl phosphate reaction intermediate has not been trapped. This putative intermediate would be very reactive, and can break down to release Pi and CO2, which has also been suggested as the operative electrophile.

The capabilities of the wild-type and hybrid proteins to produce acetyl phosphate, formyl phosphate, and carboxyl phosphate were assayed by trapping of free acyl phosphates as hydroxamates, which can be visualized spectrophotometrically as described in the Materials and Methods section (Table III). Using this methodology, no evidence for carboxyl phosphate was observed, but this could be explained by the short lifetime of this reactive species. Wild-type PurK also does not produce detectable amounts of formyl phosphate or acetyl phosphate, but formate and acetate are not the natural substrates of this enzyme. Wild-type PurT, both with and without an N-terminal MBP fusion, is able to produce detectible levels of acetyl phosphate but not formyl phosphate. Presumably no formyl phosphate is trapped because this intermediate does not dissociate from the wild-type enzyme at appreciable levels.

Table III.

Production of Acyl Phosphates by Wild-Type and Hybrid Enzymes

| Specific activity (μmol/min/mg)×10−4 for production of acyl phosphates using various substratesa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Acetyl phosphate | Formyl phosphate | Carboxyl phosphate |

| PurTb | 4.4 × 103 | NAc | NA |

| PurTd | 715 | NDe | ND |

| PurKd | ND | ND | ND |

| KATBCd | 3.8 | 2.8 | ND |

| TAKBCd | 8.6 | 4.0 | ND |

| TACKBd | 11.1 | 1.7 | ND |

| KACTBd | 0.61 | 0.43 | ND |

| KABTCd | 10.7 | 7.7 | ND |

| TABKCd | 0.80 | 0.75 | ND |

Specific activities were determined under saturating concentrations of each substrate. The standard error is less than 10%.

Adapted from Ref.24.

NA not applicable.

Fusion protein with an N-terminal MBP domain.

ND not detected.

In contrast to the wild-type proteins, all hybrid proteins showed the ability to generate acetyl phosphate and formyl phosphate. Additionally, wild-type PurT and PurK proteins do not produce ADP in the absence of GAR or AIR, respectively, but the rates of acyl phosphate production by the hybrid proteins were not affected by the presence of either GAR or AIR. For each hybrid protein except TACKB, the catalytic activity for production of acetyl phosphate is in reasonable agreement with that for the production of formyl phosphate, suggesting no preference for formate or acetate as recipient. Compared to their ATPase activities, the hybrid proteins catalyze the production of acyl phosphate less efficiently, by two orders of magnitude. For wild-type PurT, the ratio of trapped acetyl phosphate to ADP was 0.70 ± 0.15.24 Because of a highly optimized architecture in the active site of the wild-type enzyme, the unaccounted for acetyl phosphate is likely hydrolyzed in solution or at the active site before being trapped. In the hybrid proteins, the ratio of trapped acetyl phosphate to ADP decreased to less than 0.01. Therefore, more than 99% of ATP was hydrolyzed and released into solution as ADP and Pi without being transferred to produce detectable acetyl or formyl phosphate. The significant drop in the efficiency of Pi transfer in the hybrid proteins is likely a result of incompatibilities in the swapped protein domains or other missing factors.

Generation of an active chimeric protein with PurK activity

Although the six hybrid proteins described earlier can all catalyze partial reactions, none can efficiently couple the reaction intermediates to achieve catalysis of the full reaction. Presumably, either misalignment of the swapped domains or other missing protein features leads to the inefficient coupling and prerelease of intermediates into solution. As reported previously, a single mutation in PurT, G162I, leads to reaction uncoupling similar to what is observed in these hybrid proteins. Mutation of this glycine to a bulky isoleucine residue greatly reduces the overall catalytic activity of PurT, increases the KM of formate, and allows “leaking” of the formyl phosphate intermediate into solution where it can be trapped.23 This amino acid position is located on the B-loop (also called the T-loop), and is where further efforts were directed to improve the domain-swapped hybrids.

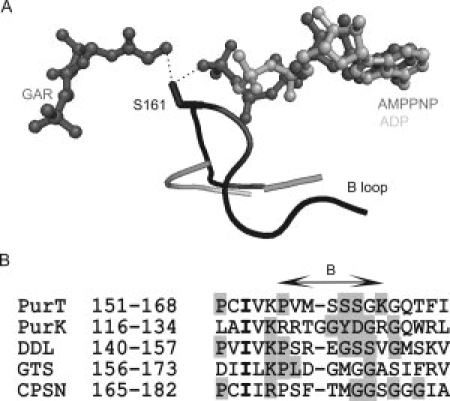

In ATP grasp proteins, the B-loop connects the second and third strands of the B-domain's β-sheet, and is disordered when a bound ligand is not present. The conformation of the B-loop is even dependent on the moiety occupying the γ-phosphate position of ATP analogs.22 The B-loop is located near the central interfaces of all three domains and likely helps to sequester reaction intermediates. Of the five loop regions constituting the active site in PurT, only the residues in the B-loop are involved in the binding of two substrates, ATP and GAR, as the hydroxyl group of Ser161 is in hydrogen bond distance to both the γ-phosphate of ATP and the amine group of GAR (see Fig. 5). Although the B-loop is not visible in the ADP-bound PurK structure (presumably due to the lack of a γ-phosphate group), this loop is believed to play a similar role in binding of ATP and AIR in PurK. In general, the sequence of B-loops are rich in glycine and serine, but the PurK sequence is atypical and bears conserved tyrosine and aspartate residues. In summary, because of the proximity of the B-loop to both substrate-binding sites, its proposed role in sequestering reactive intermediates and the sequence divergence in this loop between PurT and PurK enzymes, we focused on making further modifications to the B-loops in the partially functional domain-swapped hybrid proteins.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the B loop (also called the T-loop) in PurT and PurK structures (A), and the consensus sequences from five ATP grasp proteins (B). In (A), the B loop regions in PurT and PurK are colored in black and gray, respectively. The GAR, AMPPNP, and ADP molecules are shown in ball-and-stick representation, with GAR, AMPPNP colored in dark gray and ADP colored in gray. The residue S161 in PurT is depicted in stick representations, and the hydrogen bonds between its hydroxyl group and GAR and AMPPNP are shown as dotted lines. The B loop of PurK (gray) is partially disordered. Panel (B) shows structure-based alignment of the B-loop sequences from PurT, PurK, d-alanine:d-alanine ligase (DDL), glutathione synthetase (GTS), and carbamoyl phosphate synthetase (CPS N-domain). Conserved residues in each enzyme are masked in gray, and identical residues among all five sequences are shown bold.

To evaluate the potential of the B-loop to improve catalysis, six additional protein constructs were created and selected in vivo for PurT and PurK activities. In each protein, a small portion of the B-loop derived from PurT (S159, Ser160, and Ser161, abbreviated as LT) is replaced by the corresponding sequence in PurK (Gly125, Tyr126, Asp127, and Gly128, abbreviated as LK), and vice versa. This procedure generated six proteins, TACKBLT, KACTBLK, KABTCLT, TABKCLK, KABCLT, and TABCLK that are the counterparts of TACKB, KACTB, KABTC, TABKC, wild-type PurK, and wild-type PurT, respectively, but with swapped B-loops. This short amino acid stretch is smaller than can be defined as a protein module, but is within the scope of changes accessible by mutational drift.

Of the six loop-swapped proteins tested with both PurK(−) and PurT(−) auxotropic strains, one construct does enable cell survival. The domain- and loop-swapped hybrid protein KACTBLK can complement the PurK(−) auxotrophic strain, indicating that this hybrid can now catalyze the full reaction. Under selective conditions, cells expressing the KACTBLK hybrid grow at a rate comparable to cells expressing wild-type PurK. This contrasts with the TACKBLT hybrid, which does not confer survival to the PurT(−) auxotrophic strain. To investigate the properties of the active hybrid enzyme in more detail, wild-type PurK and KACTBLK were purified to homogeneity as C-terminal His-tagged constructs. Steady-state kinetic parameters of these two purified proteins were determined by following the production of ADP (Table IV). Compared to wild-type PurK, KACTBLK has a sevenfold decrease in the kcat, a sevenfold decrease in the KM for ATP, and a 6.4-fold decrease in KM for AIR. These changes are offsetting, so that the specificity constants (kcat/KM) for both ATP and AIR match those of wild-type PurK, within error. This striking result suggests that the only element in the B-domain that is unique for PurK catalysis is the swapped four amino acid sequence found in the B-loop. It is also notable that this small change allows the hybrid protein to regain the dependence of its ATPase activity on the presence of AIR, as seen with wild-type PurK.

Table IV.

Kinetic Parameters PurK and KACTBLKa

| Enzyme | kcat (s−1) | Km (ATP) (μM) | Km (AIR) (μM) | kcat/Km (AIR) (μM−1 s−1) | kcat/Km (ATP) (μM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PurK | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 48 ± 8.5 | 66 ± 16 | 0.089 | 0.12 |

| KACTBLK | 0.87 ± 0.02 | 6.8 ± 0.7 | 10.3 ± 1.2 | 0.084 | 0.13 |

Experimental procedures described in Materials and Methods.

During preparation of this manuscript, a publication by Thoden et al. reported the structures of E. coli PurK in complex with MgATP and with MgATP/Pi.35 In these two structures, the B-loop is observed to interact with the γ-phosphoryl group of ATP, or with Pi, respectively. Bound Pi is proposed to mimic the carboxy-phosphate intermediate, and is within hydrogen bonding distance of the backbone amide of Asp127, a residue located within the B-loop. Additionally, the side chain of Asp127, in conjunction with Lys314 (found in the C-domain), is proposed to activate the exocyclic amine of AIR for its attack. This recent work provides a possible mechanistic basis for understanding why swapping the B-loop is essential to recover PurK activity in the hybrid protein reported herein.

It is not entirely surprising that from all of the possible successful outcomes, swapping the B-domain and recovery of PurK activity was observed. In contrast to formylation of GAR, carboxylation of AIR can occur readily through a nonenzymic process, and growth of PurK auxotrophic strains can be rescued by growth in conditions that enrich CO2 concentrations.25,36 The B-domains of ATP grasp proteins are flexible domains that close down over the ATP substrate, and this flexibility could minimize unfavorable effects due to nonoptimized interactions between domains that have not coevolved. Also, carboxylation of AIR by either carboxyl phosphate or CO2 likely represents an easier task than formylation of GAR. Even if carboxyl phosphate is not stabilized in the hybrid, the resulting CO2 breakdown product could serve as an electrophile. Therefore, swapping the B-domains and recovery of PurK activity may represent the “lowest hurdle” to overcome in this model system.

There have been many other successful examples of engineering novel protein catalysts by modular domain swapping, most notably those including various enzymes fused to zinc-finger domains, or polyketide synthases and nonribosomal peptide synthases with deleted, swapped, or added modules (reviewed in Refs. 36 and 37). Unlike these examples where the binding and catalytic domains are somewhat distinct, domain swapping between PurT and PurK requires compatibility between all three modules to reconstitute functional binding and active sites. Therefore, achieving one active domain- and loop-swapped hybrid protein from only 14 rationally designed constructs is notable and is consistent with the proposal of domain swapping as a viable mechanism for protein evolution.

Materials and Methods

All restriction enzymes used were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA) unless otherwise indicated. DNA samples were purified using the QIAprep, as well as the QIAquick Gel and PCR purification kit (all from Qiagen, Valencia, CA), following the manufacturer's protocols.

Bacterial strains

The E. coli strains, DH-5α and BL21(DE3), were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and Novagen (Madison, WI), respectively. TX680F′ [ara Δ (gpt-rpo-lac) thi rbs-221 ilvB2102 ilvH1202 purN′-lacZ+Y+::KanRpurT] E. coli, a PurT auxotropic strain, is a gift from Dr. J.M. Smith.39 CSH26, purK [purK, zba::tn10] E. coli, a PurK auxotropic strain, was a gift from Dr. Gert Dandanell.32 The PurT(−) strain is E. coli K-12 MG1655 with chromosomal purN and purT deleted, and the PurK(−) strain is E. coli K-12 MG1655 with chromosomal purK deleted. Both PurT(−) and PurK(−) strains were constructed by a one-step knockout method like that described elsewhere.33

Construction of hybrid enzymes

All hybrid enzymes were constructed using the PCR overlapping extension method40 (see Fig. 4). For in vivo complementation assays, the wild-type genes encoding PurT and PurK genes and the hybrid gene fragments were cloned into pDIM-PGX vector using NdeI/SpeI sites.41 For protein expression and purification, the gene fragments encoding six chimeras (TAKBC, KATBC, TACKB, KACTB, TABKC, and KABTC), as well as the sequences encoding PurT and PurK, were amplified from pDIM vectors using the PCR, and subcloned into pMAL-c2x vectors (New England Biolabs, Beverly MA) between XmnI and SpeI sites. The gene fragments encoding wild-type PurK and KACTBLK were also subcloned into a pET22b expression vector (Navogen, Madison, WI) between NdeI and HindIII sites. All of the final products were confirmed by DNA sequencing of the inserts.

Screening of PurT and PurK activities by in vivo complementation

pDIM vectors encoding each of the hybrid and wild-type enzymes were transferred into auxotrophic E. coli strains. After each transformation and an initial ampicillin (100 mg/mL) selection on LB agar, three single colonies were randomly picked and streaked in an “X” pattern on LB ampicillin (100 mg/mL) agar to make a master printing plate. After incubation at 37°C overnight, the cells on master plates were replica printed onto selective plates (M9 salt, 0.2% glucose, 0.06% caseine, 2 μg/mL thiamine, 1.5% agar, 100 μg/mL ampicillin) with 0.3 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG). Functional complementation tests were conducted for up to 48 h at 30°C in TX680F′ and CSH26 strains and at 25°C in PurT(−) and PurK(−) strains. Colonies that grew on selective plates were restreaked on new selective plates to obtain single colonies, from which the plasmids were extracted, and retransformed into the respective auxotrophic strain, followed by the same selection procedure to affirm complementation. Plasmids were extracted from the first and second selections and the gene inserts were sequenced to confirm that there were no additional mutations.

Overexpression of hybrid enzymes and protein purification

N-terminal maltose-binding-protein (MBP) fusion proteins of PurT, PurK, and the six hybrid proteins were expressed using the pMAL-c2x derivative described earlier. To eliminate background contamination by native enzymes, the hybrid proteins KATBC, TACKB, KABTC, and wild-type PurT were expressed in the PurT(−) auxotrophic strain, while TAKBC, KACTB, TABKC, and wild-type PurK were expressed in the PurK(−) auxotrophic strain. The pET22b expression vectors containing sequences encoding wild-type PurK and KACTBLK were transformed into BL21 (DE3) E. coli for overexpression. In each case, a single colony was used to start an overnight culture, 1% of which was inoculated into fresh LB media (100 μg/mL ampicillin) and grown at 37°C to an OD600 of ∼0.5 before addition of 0.3 mM IPTG and cooling of the incubations to 18°C. After 8 h of induction at this lower temperature, cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −70°C.

Utilizing the specific binding of the N-terminal MBP domain, primary purification of the proteins overexpressed from the pMAL-c2x vector was performed on amylose resin, following the manufacture's instructions. Subsequent to elution from the amylose resin using Column Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA) with 10 mM maltose, the protein solution was loaded onto a Superose 12 gel filtration column (24 mL bed volume) pre-equilibrated in Buffer X (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl), and eluted using five bed volumes of Buffer X. Fractions containing hybrid proteins were identified by apparent size using SDS-PAGE, and pooled accordingly.

Proteins expressed from derivatives of the pET22b expression vector were purified using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, Valencia CA), following the manufacture's instructions. After removal of excessive imidazole by dialysis, the protein solutions were loaded onto a 5 mL HiTrap™ DEAE column (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) pre-equilibrated in Buffer X. During application of a linear salt gradient (0–1M NaCl), the desired proteins eluted at 0.3–0.4M NaCl. Fractions containing desired proteins were identified by apparent size using SDS-PAGE, and pooled accordingly.

Purified proteins (>95% homogeneous by SDS-PAGE) were concentrated using Centricon spin filters (MWCO 10 kDa, Amicon, Bedford, MA) and stored frozen at −70°C. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford analysis using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Measurement of ATP hydrolysis

Because the effect of HCO3− on ATP cleavage rates of hybrid proteins is investigated, excess HCO3− was removed from buffers as described elsewhere.34 The ATPase activity of each hybrid protein was measured by monitoring the production of ADP via the coupling reactions of pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase (PK/LDH), as previously described with some modifications.24 In a total volume of 100 μL, 100 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 20 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, 2 mM PEP, 0.2 mM NADH, and 10 units of PK/LDH were combined and allowed to incubate at 25°C. Reactions were initiated by addition of purified enzymes, and the absorbance decrease at 340 nm due to the consumption of NADH (ɛ = 6.22 mM−1 cm−1) was monitored on a Cary I UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Varian, Palo Alto CA). For wild-type PurT, PurK and the hybrid KABTC proteins, the kinetic parameters of ATP cleavage were determined in triplicate over a concentration range of 10–200 μM AIR, 5–100 μM GAR, 0.1–10 mM ATP, and 0.1–2 mM formate. By varying the concentration of one substrate at saturating concentrations of the other substrates, the Michaelis constants for each substrate were determined by fitting to a double reciprocal plot using the program KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software). For all other hybrid fusion proteins, the ATPase specific activity (μmol min−1 mg−1) was determined using the different substrates at their respective saturating concentrations (ATP, 5 mM; GAR, 100 μM; AIR, 260 μM; formate, 3 mM; HCO3−, 3 mM).

Detection of acyl phosphate

Free acyl phosphate was assayed by trapping as the hydroxamate derivative, using a previously described method.42 Briefly, in a total volume of 300 μL, 100 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 20 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, and saturating concentrations of substrates were combined and incubated at 25°C for 5 min. Reactions were initiated upon addition of purified enzymes. At various time points, aliquots of the incubating reaction were taken and mixed with an equal volume of a freshly made 1:1 (v/v) mixture of 3M hydroxylamine and 3M NaOH. Following a 10-min incubation with the alkaline hydroxylamine solution, 1 volume of 0.74M trichloroacetate (TCA) and 2 volumes of 0.22 mM FeCl3 in 0.5M HCl were added. The resulting derivatives are yellow in color and their absorbance at 490 nm is used for quantification in comparison to a succinohydroxyamate standard curve.

Kinetic assay for the PurK activity

The PurK activity of wild-type PurK and the hybrid KACTBLK protein, each bearing a C-terminal His tag, were measured by monitoring the production of ADP via the coupling reactions of pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase (PK/LDH), as described elsewhere with some modifications.25 Briefly, in a total volume of 100 μL, 100 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 20 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, 2 mM PEP, 0.2 mM NADH, and 10 units of PK/LDH were combined, and incubated at 25°C for 5 min. Reactions were initiated by the addition of purified enzymes, and the absorbance decrease at 340 nm due to the consumption of NADH (ɛ = 6.22 mM−1 cm−1) was monitored on a Cary I UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Varian). Kinetic parameters were determined in triplicate using a concentration range of 5–40 μM AIR, 5–100 μM ATP. By varying the concentration of one substrate at the saturating concentrations of the other substrates, the Michaelis constants for each substrate were determined by fitting to a double reciprocal plot using the program KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software).

Conclusions

In this study, we have investigated the modular nature of protein structure and function using PurT and PurK as a model system. Features of these results help to illuminate aspects of protein domain swapping that may occur during enzyme evolution. In this system, swapping one domain between two homologous three-domain proteins consistently resulted in less stable hybrid proteins that were unable to catalyze a full reaction. Presumably, the interface between the swapped domain and the rest of the hybrid is not well optimized. Despite these imperfections, each of the domain-swapped hybrids is able to catalyze partial reactions, suggesting that functional binding and catalytic sites are partially maintained. Additional minor modifications of the domain-swapped hybrids, here the substitution of a short loop region suspected to sequester reaction intermediates, are required to enhance coupling of the partial reactions to reconstitute a full reaction sufficient to impact cell survival. This study illustrates how a mechanistic understanding of intermediary hybrid proteins can improve the design and construction of a fully functional enzyme.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AIR

aminoimidazole ribonucleotide

- BC

biotin carboxylase

- CPS

carbamoyl phosphate synthetase

- GAR

glycinamide ribonucleotide

- N5-CAIR

N5-carboxylaminoimidazole ribonucleotide.

References

- 1.Aimi J, Qiu H, Williams J, Zalkin H, Dixon JE. De novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis: cloning of human and avian cDNAs encoding the trifunctional glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase-aminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase-glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase by functional complementation in E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6665–6672. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kan JL, Jannatipour M, Taylor SM, Moran RG. Mouse cDNAs encoding a trifunctional protein of de novo purine synthesis and a related single-domain glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase. Gene. 1993;137:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doolittle RF, Bork P. Evolutionarily mobile modules in proteins. Sci Am. 1993;269:50–56. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1093-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott KA, Steward A, Fowler SB, Clarke J. Tita multidomain protein that behaves as the sum of its parts. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:819–829. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mainfroid V, Goraj K, Rentier-Delrue F, Houbrechts A, Loiseau A, Gohimont AC, Noble ME, Borchert TV, Wierenga RK, Martial JA. Replacing the (beta alpha)-unit 8 of E. coli TIM with its chicken homologue leads to a stable and active hybrid enzyme. Protein Eng. 1993;6:893–900. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang D, Thoma R, Henn-Sax M, Sterner R, Wilmanns M. Structural evidence for evolution of the beta/alpha barrel scaffold by gene duplication and fusion. Science. 2000;289:1546–1550. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hocker B, Beismann-Driemeyer S, Hettwer S, Lustig A, Sterner R. Dissection of a (betaalpha)8-barrel enzyme into two folded halves. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:32–36. doi: 10.1038/83021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hocker B, Claren J, Sterner R. Mimicking enzyme evolution by generating new (betaalpha)8-barrels from (betaalpha)4-half-barrels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16448–16453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405832101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogel C, Bashton M, Kerrison ND, Chothia C, Teichmann SA. Structure, function and evolution of multidomain proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostermeier M, Benkovic SJ. Evolution of protein function by domain swapping. Adv Protein Chem. 2000;55:29–77. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(01)55002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galperin MY, Koonin EV. A diverse superfamily of enzymes with ATP-dependent carboxylate-amine/thiol ligase activity. Protein Sci. 1997;6:2639–2643. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waldrop GL, Rayment I, Holden HM. Three-dimensional structure of the biotin carboxylase subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10249–10256. doi: 10.1021/bi00200a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thoden JB, Holden HM, Wesenberg G, Raushel FM, Rayment I. Structure of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase: a journey of 96 A from substrate to product. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6305–6316. doi: 10.1021/bi970503q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaguchi H, Kato H, Hata Y, Nishioka T, Kimura A, Oda J, Katsube Y. Three-dimensional structure of the glutathione synthetase from Escherichia coli B at 2.0 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:1083–1100. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolodko WT, Fraser ME, James MN, Bridger WA. The crystal structure of succinyl-CoA synthetase from Escherichia coli at 2.5-A resolution. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10883–10890. doi: 10.2210/pdb1scu/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan C, Moews PC, Walsh CT, Knox JR. Vancomycin resistance: structure of d-alanine:d-alanine ligase at 2.3 A resolution. Science. 1994;266:439–443. doi: 10.1126/science.7939684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang W, Kappock TJ, Stubbe J, Ealick SE. X-ray crystal structure of glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15647–15662. doi: 10.1021/bi981405n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. Protein structure alignment by incremental combinatorial extension (CE) of the optimal path. Protein Eng. 1998;11:739–747. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.9.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thoden JB, Kappock TJ, Stubbe J, Holden HM. Three-dimensional structure of N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase: a member of the ATP grasp protein superfamily. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15480–15492. doi: 10.1021/bi991618s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thoden JB, Firestine SM, Nixon A, Benkovic SJ, Holden HM. Molecular structure of Escherichia coli PurT-encoded glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8791–8802. doi: 10.1021/bi000926j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thoden JB, Firestine SM, Benkovic SJ, Holden HM. PurT-encoded glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase: accomodation of adenosine nucleotide analogs within the active site. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23898–23908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marolewski AE, Mattia KM, Warren MS, Benkovic SJ. Formyl phosphate: a proposed intermediate in the reaction catalyzed by Escherichia coli PurT GAR transformylase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6709–6716. doi: 10.1021/bi962961p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marolewski A, Smith JM, Benkovic SJ. Cloning and characterization of a new purine biosynthetic enzyme: a non-folate glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase from E. coli. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2531–2537. doi: 10.1021/bi00175a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller EJ, Meyer E, Rudolph J, Davisson VJ, Stubbe J. N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide: evidence for a new intermediate and two new enzymatic activities in the de novo purine biosynthetic pathway of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2269–2278. doi: 10.1021/bi00174a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sauers CK, Jencks WP, Groh S. Alcohol-bicarbonate-water system. Structure-reactivity studies on the equilibriums for formation of alkyl monocarbonates and on the rates of their decomposition in aqueous alkali. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:5546–5553. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nixon AE, Warren MS, Benkovic SJ. Assembly of an active enzyme by the linkage of two protein modules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1069–1073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inglese J, Johnson DL, Shiau A, Smith JM, Benkovic SJ. Subcloning, characterization, and affinity labeling of Escherichia coli glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1436–1443. doi: 10.1021/bi00458a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein C, Chen P, Arevalo JH, Stura EA, Marolewski A, Warren MS, Benkovic SJ, Wilson IA. Towards structure-based drug design: crystal structure of a multisubstrate adduct complex of glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase at 1.96 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1995;249:153–175. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nixon AE, Benkovic SJ. Improvement in the efficiency of formyl transfer of a GAR transformylase hybrid enzyme. Protein Eng. 2000;13:323–327. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.5.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostermeier M, Shim JH, Benkovic SJ. A combinatorial approach to hybrid enzymes independent of DNA homology. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:1205–1209. doi: 10.1038/70754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorensen IS, Dandanell G. Identification and sequence analysis of Sulfolobus solfataricus purE and purK genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;154:173–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer E, Leonard NJ, Bhat B, Stubbe J, Smith JM. Purification and characterization of the purE, purK, and purC gene products: identification of a previously unrecognized energy requirement in the purine biosynthetic pathway. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5022–5032. doi: 10.1021/bi00136a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thoden JB, Holden HM, Firestine SM. Structural analysis of the active site geometry of N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13346–13353. doi: 10.1021/bi801734z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gots JS, Benson CE, Jochimson B, Koduri KR. Microbial models and regulatory elements in the control of purine metabolism. In: Elliott K, Fitzsimons DW, editors. Purine and pyrimidine metabolism. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1976. pp. 23–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lutz S, Benkovic SJ. Homology-independent protein engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2000;11:319–324. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mootz HD, Marahiel MR. Design and application of multimodular peptide synthetases. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(99)80062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nygaard P, Smith JM. Evidence for a novel glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3591–3597. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3591-3597.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lutz S, Ostermeier M, Benkovic SJ. Rapid generation of incremental truncation libraries for protein engineering using alpha-phosphothioate nucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(4):E16. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.4.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pechere JF, Capony JP. On the colorimetric determination of acyl phosphate. Anal Biochem. 1967;22:536–539. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kappock TJ, Ealick SE, Stubbe J. Modular evolution of the purine biosynthetic pathway. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4:567–572. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]