Abstract

This study investigates the association between cigarette use and current mood/anxiety disorders among pregnant opioid-dependent patients. Pregnant methadone-maintained women (N = 122) completed the Addiction Severity Index and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Participants were categorized based on past 30 days cigarette use: no (n = 15) and any smoking (n = 107); this latter group was then subdivided into light (one to ten cigarettes/day; n = 55), and heavy smokers (11+ cigarettes/day; n = 52). Any smoking was significantly associated with any current mood/anxiety disorder (p < 0.001), any current mood disorder (p = 0.007), and any current anxiety disorder (p < 0.001). No significant association was found between specific level of cigarette use and mood/anxiety disorders. This association between smoking and psychiatric disorders has implications for the mental and physical health of methadone-maintained women and their children, and may contribute to the understanding of the physiological mechanisms underlying smoking and nicotine dependence.

Introduction

Maternal smoking is the leading modifiable risk factor for pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality in the United States and other developed countries.1,2 The adverse effects of smoking during pregnancy include an increased risk of miscarriage and stillbirth, placental abnormalities, pre-term birth and low birth weight leading to increased perinatal morbidity.3,4 Children of mothers who smoke during pregnancy are at increased risk of neonatal mortality, including sudden infant death syndrome.5,6 Women who quit smoking before or during pregnancy can substantially reduce these risks to themselves and their infants.

In response to public education and public health campaigns, the prevalence of smoking during pregnancy in the US declined from 34% in 1965 to 22–23% in the late 1990s.2 However, there has been no change in smoking prevalence during pregnancy in the US since 1998 with approximately 75–80% of women who smoke cigarettes prior to pregnancy continuing to do so during pregnancy.7–9 Presence of psychiatric illness, including other substance use disorders, is a risk factor for continued smoking during pregnancy, along with other risk factors shared by both nicotine and other substance dependence disorders such as young age, low income, being without a partner, social disadvantage, high parity, heavy cigarette use, and receiving Medicaid-funded maternity care.10–20 Because further efforts are needed to increase smoking cessation rates among pregnant smokers, examining the association between psychiatric illness and cigarette smoking during pregnancy continues to be relevant in the development of novel treatment strategies and improved quit rates in this population.

In contrast to pregnant women in general, very little is known about smoking and smoking cessation behaviors of pregnant women dependent on other substances. Smoking rates among individuals being treated for other substance use disorders, especially those being treated with methadone for opiate dependence, are known to be exceptionally high with some studies suggesting rates in excess of 90%.21,22 Approximately 86% of pregnant methadone-maintained patients smoke cigarettes (with one study noting depressive symptoms in 40% of participants).23 Despite multiple studies suggesting that smoking may be more harmful to the developing fetus than use of other illicit drugs (eg, cocaine, marijuana and opioids), and that the combination of smoking and drug use is associated with worse birth outcomes than smoking alone, the additional health burden of cigarette smoking during pregnancy is often underestimated.24–28

Interventions to help pregnant substance-dependent women quit smoking can pose a particular clinical challenge because of their limited resources, complex psychosocial situations and often high level of nicotine dependence.29 While a critical need exists to develop efficacious treatments for these women, it is important to first understand whether co-morbid conditions that are associated with continued smoking in the general population of pregnant women (eg, psychiatric disorders) have a similar relationship to smoking in women who are pregnant and dependent on other drugs. The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between cigarette smoking during pregnancy and psychiatric illness in a population of pregnant substance dependent patients. Specifically, this study examined the association between different levels of cigarette use and specific current mood/anxiety disorders among pregnant methadone-maintained patients.

Methods

Participants

Between June 2000 and September 2002, 222 pregnant women were admitted to the Johns Hopkins Center for Addiction and Pregnancy (CAP) and signed written informed consent to participate in a larger behavioral study comparing schedules of positive reinforcement to promote cocaine and illicit opiate abstinence. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and the primary outcomes for this study have not yet been published. Participants who tested positive for pregnancy, had evidence of illicit substance use at treatment admission, were methadone-maintained and completed the study's assessment battery are reported here (N = 122). The assessment battery was completed during an initial seven-day residential stay at the program, and included the Addiction Severity Index-5.0 (ASI-5)30 and the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I).31 Excluded were pilot participants (n = 15), those who were not maintained on methadone (n = 14), and those who did not complete the initial assessment battery (n = 71).

Setting

CAP is a comprehensive service program for substance-dependent pregnant women. Women entering the program typically complete an initial seven-day residential stay, then progress to outpatient treatment, comprised of group and individual drug-counseling sessions, as has been described in more detail previously.32,33

Assessment Battery

Addiction Severity Index (ASI)

Participants were administered the ASI-5.0, a semi-structured interview assessing lifetime and pre-treatment psychosocial functioning in seven domains: medical, employment, drug, alcohol, legal, family/social and psychiatric.30,34–36 The ASI has high test-retest reliability and validity.37 ASI interviewer training included a standardized didactic discussion of the instrument, observation of videotapes provided by the test makers, observed actual interviews administered by an expert interviewer, and administration of participant interviews under the observation of the expert interviewer. Ongoing inter-rater reliability assessments during the study were conducted and all interviewers maintained severity ratings within a three-point range of each other.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I)

Participants also completed the SCID-I, a semi-structured interview administered to assess for current and lifetime Axis I diagnoses. The SCID-I has been used extensively in many studies, with a variety of patient populations, clinical and nonclinical settings, and in different countries. Inter-rater reliability has been good and the test-retest reliabilities are above 0.6.31 Interviewer training for the SCID included a didactic review of DSM-IV criteria for Axis I disorders, a standardized review of the SCID-I instrument, observation of videotapes provided by the test makers, and coding and concordance with taped “gold standard” diagnostic interviews until the interviewer was 100% in agreement with the expert interview.

Procedures

For the present study, all participants met diagnostic criteria for opioid dependence based on results from the Substance Use Disorders module of the SCID. These opioid-dependent patients were first divided into two groups based on their past 30 days of cigarette use as reported on the intake ASI: no smoking (0 cigarettes/day; n = 15) and any smoking (1+ cigarettes/day; n = 107). Participants in the any cigarette use group were then divided into two subgroups: light smoking (one to ten cigarettes/day; n = 55) and heavy smoking (11+ cigarettes/day; n = 52), in order to test for possible associations between the level of cigarette use and psychiatric disorders. Prevalence of current mood and anxiety disorders, based on results from the SCID, was compared between the no and any cigarette use groups; and also compared between the no, light and heavy cigarette use groups.

Data Analysis

SPSS 16.0 software package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago: Illinois) was used for statistical analyses. Chi-square tests and ANOVA's with Tukey posthoc tests were used to analyze demographic and diagnostic data by smoking status and by level of cigarette use (no, light, heavy). The standard alpha of .05 was used.

Results

Results first present the demographic characteristics of the total sample and no, any, light and heavy cigarette use groups. Next, current heroin, cocaine, alcohol, and cigarette use of the total sample and no, any, light and heavy cigarette use groups are described. Then, the rates of SCID-I current mood and anxiety disorders of the total sample and no, any, light and heavy cigarette use groups are presented.

One hundred and twenty two women were included in this study. (Sample sizes for age, estimated gestational age [EGA], and marital status were 121, 115, and 114 respectively, due to missing values). The treatment entry demographic characteristics of the total sample and women with no, any, light and heavy cigarette use are shown in Table 1. (The any use group is the combination of the light and heavy use groups.) Racial minority was defined as African Americans and other minorities and the participants were predominately non-Caucasian, in their late twenties to early thirties, and had never graduated from high school and never married. Significant differences were found between the demographic variables of education and race for the no versus any, and the no versus light versus heavy cigarette use groups. However, no other significant differences were found between the remaining demographic variables and the no versus any, and the no versus light versus heavy cigarette use groups. It is important to note that the number of participants in the no use group was relatively small.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and background characteristics of pregnant methadone-maintained patients categorized by level of cigarette use (N = 122)

| Total sample | Cigarette use | Analyses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No use (N) | Any use (A) | Light use (L) | Heavy use (H) | N vs. A | N vs. L vs. H | ||

| Age, mean years (SD) | 30.1 (5.2) | 31.9 (3.7) | 29.9 (5.3) | 30.6 (4.9) | 29.1 (5.7) | T 120 = 2.10 p = 0.150 | F(2,119) = 2.17 p = 0.119 |

| Estimated gestational age, mean weeks (SD) | 15.7 (7.0) | 15.8 (7.4) | 15.7 (7.0) | 14.5 (6.2) | 16.9 (7.6) | T 111 < 0.01; p = 0.962 | F(2,115) = 1.59; p = 0.209 |

| Education, mean years completed (SD) | 11.1 (1.6) | 11.7 (1.1) | 11.0 (1.6) | 11.5 (1.2) | 10.5 (1.8) | T 119 = 2.58 p = 0.111 | F(2,118) = 7.22 p < 0.001 N,L > H |

| Never married, percent | 73 | 67 | 74 | 80 | 69 | χ2(1) = 0.39 p = 0.533 | χ2(2) = 2.01 p = 0.365 |

| Racial minority, percent | 78 | 87 | 76 | 91 | 61 | χ2(1) = 0.80 p = 0.372 | χ2(2) = 14.65 p < 0.001 N,L > H |

| Drug use, mean days past 30 before treatment entry (SD) | |||||||

| Heroin | 25.7 (9.0) | 24.5 (11.2) | 25.8 (8.7) | 24.6 (10.2) | 27.1 (6.7) | T 120 = 0.27 p = 0.606 | F(2,119) = 1.18 p = 0.311 |

| Cocaine | 12.7 (12.1) | 8.0 (11.9) | 13.3 (12.0) | 12.3 (11.9) | 14.4 (12.2) | T 120 = 2.58 p = 0.111 | F(2,119) = 1.73 p = 0.181 |

| Alcohol | 4.7 (9.3) | 3.8 (7.8) | 4.7 (9.3) | 4.5 (9.0) | 5.4 (10.0) | T 120 = 0.16 p = 0.694 | F(2,119) = 0.27 p = 0.763 |

| Any drug use past 30 days before treatment entry, percent | |||||||

| Heroin | 93 | 87 | 94 | 93 | 96 | χ2(2) = 1.28 p = 0.258 | χ2(2) = 1.79 p = 0.408 |

| Cocaine | 75 | 60 | 77 | 76 | 77 | χ2(2) = 1.92 p = 0.166 | χ2(2) = 1.93 p = 0.382 |

| Alcohol | 44 | 47 | 44 | 44 | 44 | χ2(2) = 0.04 p = 0.841 | χ2(2) = 0.04 p = 0.978 |

| Mean (SD) number cigarettes smoked per day, past 30 days before treatment entry | 13.9 (13.5) | 0.0 (0.0) | 15.9 (12.9) | 7.3 (2.6) | 24.9 (13.4) | T 120 = 22.45 p < 0.001 | F(2,119) = 72.96 p < 0.001 N < L < H |

The mean days of heroin, cocaine and alcohol use reported at treatment entry for the total sample and women with no, any, light and heavy cigarette use are shown in Table 1. In the 30 days prior to admission, 113 patients (93%) had used heroin, 92 (75%) had used cocaine, and 68 (56%) had used alcohol at least one day by self-report (those who had not used heroin in the 30 days prior to admission were dependent on non-heroin opioids, including methadone). There was no significant difference between any of these substance use variables for the no versus any, and the no versus light versus heavy cigarette use groups.

In the 30 days prior to admission, 107 (88%) of the women had smoked at least one cigarette. The mean number of cigarettes smoked in the 30 days prior to treatment entry of the total sample and women with no, any, light and heavy cigarette use are shown in Table 1.

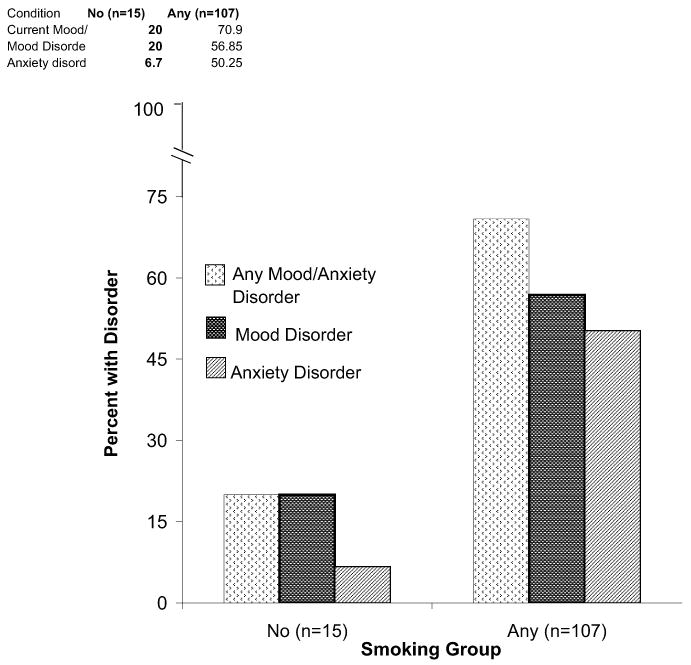

Methadone-maintained pregnant women who reported any level of cigarette use during pregnancy were significantly more likely to meet criteria for any current mood/anxiety disorder (p < 0.001), any current mood disorder (p = 0.007), and any current anxiety disorder (p < 0.001) compared with those who did not (Figure 1). Both light and heavy smokers were significantly more likely to meet criteria for major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder specifically compared with non-smokers. (These two variables did not have any significant post hoc tests, which was an expected result given the more conservative nature of post hoc tests compared to the main analysis.)

FIGURE 1.

Rates of current mood/anxiety disorders in no and any cigarette use groups

No significant association was found between the specific level of cigarette use (ie, light vs. heavy) and any current mood/anxiety disorders. The SCID-I current mood/anxiety disorders of the total sample and of any, no, light and heavy cigarette use groups are shown in Table 2. Given the small group size for the non-smokers, a sample power analysis (comparing the association between any cigarette use and any current mood/anxiety disorder diagnosis) was performed and found a large effect size of (d = 0.7941). In light of the imbalance between group size for the smokers and non-smokers, non-parametric and correlational analyses were also performed. Findings from analyses using KruskalWallis tests were consistent with results from parametric analyses. Analyses using smoking status (as a dichotomized measure of smoking) yielded more robust results compared to correlations using the number of cigarettes per day (as a continuous measure of smoking).

TABLE 2.

Rates of current mood/anxiety disorders among pregnant methadone-maintained patients

| Current Diagnosis (percent) |

Total sample N = 122 |

Cigarette use | Analyses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No use (N) n = 15 |

Any use (A) n = 107 |

Light use (L) n = 55 |

Heavy use (H) n = 52 |

N vs. A | N vs. L vs. H | ||

| Any mood or anxiety disorder | 64.8 | 20.0 | 71.0 | 76.4 | 65.4 | χ2(1) = 15.01 p < 0.001 | χ2(2) = 16.42; p < 0.001 N < L,H |

| Any mood disorder | 52.5 | 20.0 | 57.0 | 61.8 | 51.9 | χ2(1) = 7.23 p = 0.007 | χ2(2) = 8.28 p = 0.016 |

| Major depressive disorder | 44.3 | 13.3 | 48.6 | 52.7 | 44.2 | χ2(1) = 6.63 p = 0.010 | χ2(2) = 7.41 p = 0.025 |

| Substance-induced mood disorder | 12.3 | 0.0 | 14.0 | 12.7 | 15.4 | χ2(1) = 2.40 p = 0.122 | χ2(2) = 2.57 p = 0.276 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 45.1 | 6.7 | 50.5 | 58.2 | 42.3 | χ2(1) = 10.19 p < 0.001 | χ2(2) = 12.92 p = 0.002 N < H |

| Specific phobia | 16.4 | 0.0 | 18.7 | 21.8 | 15.4 | χ2(1) = 3.35 p = 0.067 | χ2(2) = 4.16 p = 0.125 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 36.7 | 7.1 | 40.6 | 44.4 | 36.5 | χ2(1) = 5.95 p = 0.015 | χ2(2) = 6.66 p = 0.036 |

Discussion

This study examined the associations between smoking, substance use, and common psychiatric disorders in pregnant women with opioid dependence. The two major findings of this study are that methadone-maintained pregnant women who smoke are significantly more likely to meet criteria for current mood/anxiety disorders than those who do not smoke and that the association of cigarette use and these disorders is not affected by smoking severity. The findings are consistent with results from other studies that have examined similar associations for pregnant women, but extend these earlier reports by looking at opioid-dependent women and by examining whether these associations are affected by level of cigarette use. While in some ways this may be a specialized population of pregnant women, it is important and valuable to study this group as they represent high cost patients with a very high prevalence of cigarette use that has not been well characterized to date.

The present study found that 88% of these pregnant opioid-dependent patients were actively using cigarettes and tended to be in their late twenties to early thirties, unmarried, and with lower levels of education, results similar to those of other studies of both pregnant smokers dependent on other substances as well as smokers in general (Table 1).23,38–42 However, despite these similarities to other study populations, the present sample had higher rates of current mood and/or anxiety disorders among smokers when compared to rates of past-year mood and/or anxiety disorders in a general population of pregnant smokers.13 Thus the association between cigarette smoking and mood and anxiety disorders during pregnancy found in the current study may not be simply explained by this being a group of pregnant women. Rather, the presence of opioid dependence in these pregnant women may increase the likelihood of having a mood or anxiety disorder and being a smoker. Whether opioid dependence separately increases the risk of a mood and anxiety disorder, and the risk of smoking, or if the association of smoking and mood/anxiety disorders is linked in some way, could not be determined in this study. It would be interesting to determine if and how these three conditions (opioid dependence, smoking, a psychiatric disorder) mediate each other.

In examining the differences in smoking between participants who reported no smoking and any level of smoking, those with any cigarette use were significantly more likely to currently have any mood/anxiety disorder, any mood disorder, any anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Table 2). Smoking status may serve as a proxy for co-occurring psychiatric illnesses in this patient population. Pregnant women entering substance abuse treatment who are found to smoke should be rapidly evaluated for the presence of a co-occurring psychiatric illness, regardless of their level of cigarette use, consistent with previous data linking major depressive disorder to cigarette use during pregnancy.13,43–45

In the present study, any cigarette use was dichotomized into light versus heavy use. The determination of this split was based upon the median number of cigarettes used by the smokers, so as to produce approximately equal groups. Previous studies of mood/anxiety disorders and cigarette use during pregnancy have not explored the association between psychiatric illness and the level of cigarette use. Interestingly, for participants with any cigarette use, the specific level of use (light vs. heavy) was not significantly associated with current mood/anxiety disorder. Assessing a larger number of smokers with a greater range of daily cigarette use might detect different vulnerabilities for mood/anxiety disorders as a function of amount of smoking. Alternately, other measures of the level of nicotine dependence might reveal a relationship between degree of smoking and psychiatric disorders. However, it is also possible that any smoking increases the observed risk, with no differentiation by level of use or degree of dependence.

The profile of non-opioid substance use at treatment entry did not differ between the women who smoked during pregnancy and those who did not in this study (Table 1). The majority of both groups had used cocaine and alcohol on at least one day in the 30 days prior to treatment entry, which is consistent with previous reports of poly-substance use in populations of opioid-dependent pregnant women.46,47 To our knowledge, no previous study has looked at the pattern of poly-substance use among opioid-dependent women as a function of smoking or not smoking during pregnancy and this represents a unique area for further investigation.

Given the previously described adverse health outcomes of prenatal smoking, the importance of addressing cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence in this vulnerable population of substance-dependent patients cannot be ignored. Although studies have shown that smoking cessation treatment for general pregnant populations and pregnant substance-dependent populations can be challenging,48–51 certain intervention programs have been able to make progress in both of these populations.52–54 The present data suggest the need for intervention programs specifically designed for the pregnant, substance-dependent patient population, and especially those who have a co-occurring mood or anxiety disorders. These findings suggest the need for testing in pregnant substance-dependent and general pregnant populations of those smoking cessation interventions that have been proven efficacious for both mood disorders and nicotine dependence in non-pregnant populations.

There are several limitations to this study that should be noted. First, because the data are cross-sectional, it is impossible to assess the mechanism of the association between cigarette use and psychiatric co-occurring illness. Future studies should prospectively examine the associations observed in this study between smokers and non-smokers and light versus heavy smokers over the course of pregnancy and following delivery. Examinations of this type would be helpful toward understanding the mechanism(s) of the link between opioid dependence, smoking during pregnancy and mood and anxiety disorders. Improved knowledge in this area would facilitate developing specific methods of treatment and prevention. Second, the study relied upon self-reported cigarette use without biologic confirmation of nicotine use (eg, serum or urine cotinine, exhaled carbon monoxide), so the results may be vulnerable to bias in reporting (which can be especially true among pregnant women who may underreport cigarette use due to social stigma).55 Third, different results for psychiatric diagnoses might have been obtained if assessments had been conducted later in treatment, as psychiatric symptoms early in treatment often resolve with treatment stabilization.56,57 Fourth, the sample sizes of the groups are modest, and unequal group sizes impact the efficiency of a design, limiting the power to detect differences. Regression analyses to validate the independent association between cigarette use and mood/anxiety disorders were not able to be performed due to the small sample size.

The conclusions from the present analyses are reinforced by several notable features of this study. First, the fact that smoking status and severity were examined adds to the unique contribution and extension of the research area of perinatal addiction and co-morbid psychiatric illnesses. Though other studies have examined smoking or psychiatric co-morbidity in either general pregnant patients or substance use disordered patients;11,13,58–60 this is the first study to compare current psychiatric co-morbidity in pregnant drug dependent patients differing in smoking status and severity. Second, the study was conducted within a single clinic site, reducing potential confounds inherent in comparisons across settings or locations. Third, assessment staff administering standardized interviews were trained and supervised by the same clinicians, ensuring reliable assessments over time.

Conclusions

Among pregnant methadone-maintained women significant associations exist between current mood/anxiety disorders and any level of cigarette use. These results support those from a general population of men and women60 as well as a general pregnant population.13 Previous studies show that mood/anxiety disorders are associated with less successful quit attempts,61 so treatment of these psychiatric disorders in this population, in conjunction with treatment for nicotine and other substance use disorders, may be indicated.60 Although conventional wisdom has been to limit smoking cessation treatment to behavioral, rather than pharmacologic interventions during pregnancy due to unclear risk to the fetus of antidepressants and other psychopharmacologic agents,13,62 this recommendation is being challenged as more safety data regarding the use of these medications during pregnancy is being published and more potentially efficacious medication treatments are being developed. Future study should focus on novel pharmacologic and behavioral efforts to intervene in prenatal smoking in substance abuse treatment settings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants DA12403 (Dr. Jones) and DA023186 (Dr. Strain) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, Md.

The authors thank Lawrence Mayer for editorial assistance, Linda Felch for statistical analyses, and the patients and staff members at CAP.

Footnotes

Portions of these data were presented at the 2008 Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco scientific meeting, Portland, Oregon, February 27-March 1, 2008

References

- 1.Floyd RL, Rimer BK, Giovino GA, Mullen PD, Sullivan SE. A review of smoking in pregnancy: Effects on pregnancy outcomes and cessation efforts. Annu Rev Public Health. 1993;14:379–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.14.050193.002115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. Women and smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benowitz N, Dempsey D. Pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation during pregnancy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6 2:S189–202. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dempsey DA, Benowitz NL. Risks and benefits of nicotine to aid smoking cessation in pregnancy. Drug Saf. 2001;24:277–322. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell EA, Ford RP, Stewart AW, et al. Smoking and the sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics. 1993;91:893–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollack HA. Sudden infant death syndrome, maternal smoking during pregnancy, and the cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation intervention. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:432–436. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Reducing tobacco use: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fingerhut LA, Kleinman JC, Kendrick JS. Smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:541–544. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brosky G. Why do pregnant women smoke and can we help them quit? CMAJ. 1995;152:163–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flick LH, Cook CA, Homan SM, McSweeney M, Campbell C, Parnell L. Persistent tobacco use during pregnancy and the likelihood of psychiatric disorders. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1799–1807. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frost FJ, Cawthon ML, Tollestrup K, Kenny FW, Schrager LS, Nordlund DJ. Smoking prevalence during pregnancy for women who are and women who are not medicaid-funded. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodwin RD, Keyes K, Simuro N. Mental disorders and nicotine dependence among pregnant women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:875–883. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000255979.62280.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham H. Gender and class as dimensions of smoking behaviour in Britain: Insights from a survey of mothers. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:691–698. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham H, Der G. Patterns and predictors of tobacco consumption among women. Health Educ Res. 1999;14:611–618. doi: 10.1093/her/14.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahn RS, Certain L, Whitaker RC. A reexamination of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1801–1808. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris M, Maconochie N, Doyle P. Does gravidity influence smoking behaviour in pregnancy? A comparison of multigravid and primigravid women. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21:201–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tappin DM, Ford RP, Nelson KP, Wild CJ. Prevalence of smoking in early pregnancy by census area: Measured by anonymous cotinine testing of residual antenatal blood samples. N Z Med J. 1996;109:101–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ventura SJ, Hamilton BE, Mathews TJ, Chandra A. Trends and variations in smoking during pregnancy and low birth weight: Evidence from the birth certificate, 1990–2000. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1176–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wakefield M, Gillies P, Graham H, Madeley R, Symonds M. Characteristics associated with smoking cessation during pregnancy among working class women. Addiction. 1993;88:1423–1430. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clarke JG, Stein MD, McGarry KA, Gogineni A. Interest in smoking cessation among injection drug users. Am J Addict. 2001;10:159–166. doi: 10.1080/105504901750227804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clemmey P, Brooner R, Chutuape MA, Kidorf M, Stitzer M. Smoking habits and attitudes in a methadone maintenance treatment population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haug NA, Stitzer ML, Svikis DS. Smoking during pregnancy and intention to quit: A profile of methadone-maintained women. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:333–339. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cotton P. Smoking cigarettes may do developing fetus more harm than ingesting cocaine, some experts say. JAMA. 1994;271:576–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobson JL, Jacobson SW, Sokol RJ, Martier SS, Ager JW, Shankaran S. Effects of alcohol use, smoking, and illicit drug use on fetal growth in black infants. J Pediatr. 1994;124:757–764. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennare R, Heard A, Chan A. Substance use during pregnancy: Risk factors and obstetric and perinatal outcomes in south Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;45:220–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slotkin TA. Fetal nicotine or cocaine exposure: Which one is worse? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:931–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yawn BP, Thompson LR, Lupo VR, Googins MK, Yawn RA. Prenatal drug use in Minneapolis-St Paul, Minn. A 4-year trend. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:520–527. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.6.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiClemente CC, Dolan-Mullen P, Windsor RA. The process of pregnancy smoking cessation: Implications for interventions. Tob Control. 2009;9 3:III16–21. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. New York, NY: State Psychiatric Institute: Biometrics Research; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansson LM, Svikis D, Lee J, Paluzzi P, Rutigliano P, Hackerman F. Pregnancy and addiction. A comprehensive care model. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1996;13:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jansson LM, Svikis DS, Velez M, Fitzgerald E, Jones HE. The impact of managed care on drug-dependent pregnant and postpartum women and their children. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42:961–974. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD. Concurrent validity of the addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;171:606–610. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al. New data from the addiction severity index. reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLellan AT, Cacciola J, Alterman AI, Rikoon SH, Carise D. The addiction severity index at 25: Origins, contributions and transitions. Am J Addict. 2006;15:113–124. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaltenbach K, Berghella V, Finnegan L. Opioid dependence during pregnancy. Effects and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1998;25:139–151. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kissin WB, Svikis DS, Moylan P, Haug NA, Stitzer ML. Identifying pregnant women at risk for early attrition from substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luty J, Nikolaou V, Bearn J. Is opiate detoxification unsafe in pregnancy? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24:363–367. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miles DR, Kulstad JL, Haller DL. Severity of substance abuse and psychiatric problems among perinatal drug-dependent women. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34:339–346. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Women and smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borrelli B, Bock B, King T, Pinto B, Marcus BH. The impact of depression on smoking cessation in women. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12:378–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:216–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270028003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodwin R, Hamilton SP. Cigarette smoking and panic: The role of neuroticism. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1208–1213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones HE, Haug NA, Stitzer ML, Svikis DS. Improving treatment outcomes for pregnant drug-dependent women using low-magnitude voucher incentives. Addict Behav. 2000;25:263–267. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuczkowski KM. The effects of drug abuse on pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:578–585. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3282f1bf17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ershoff DH, Quinn VP, Boyd NR, Stern J, Gregory M, Wirtschafter D. The Kaiser Permanente prenatal smoking-cessation trial: When more isn't better, what is enough? Am J Prev Med. 1999;17:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ershoff D, Ashford TH, Goldenberg R. Helping pregnant women quit smoking: An overview. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6 2:S101–105. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melvin C, Gaffney C. Treating nicotine use and dependence of pregnant and parenting smokers: An update. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6 2:S107–124. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richter KP, Hamilton AK, Hall S, Catley D, Cox LS, Grobe J. Patterns of smoking and methadone dose in drug treatment patients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:144–153. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coleman T. Recommendations for the use of pharmacological smoking cessation strategies in pregnant women. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:983–993. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721120-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heil SH, Higgins ST, Bernstein IM, et al. Effects of voucher-based incentives on abstinence from cigarette smoking and fetal growth among pregnant women. Addiction. 2008;103:1009–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waller CS, Zollinger TW, Saywell RW, Jr, Kubisty KD. The Indiana prenatal substance use prevention program: Its impact on smoking cessation among high-risk pregnant women. Indiana Med. 1996;89:184–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boyd NR, Windsor RA, Perkins LL, Lowe JB. Quality of measurement of smoking status by self-report and saliva cotinine among pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 1998;2:77–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1022936705438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strain EC, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. Early treatment time course of depressive symptoms in opiate addicts. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179:215–221. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verheul R, Kranzler HR, Poling J, Tennen H, Ball S, Rounsaville BJ. Axis I and Axis II disorders in alcoholics and drug addicts: Fact or artifact? J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:101–110. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blalock JA, Robinson JD, Wetter DW, Cinciripini PM. Relationship of DSM-IV-based depressive disorders to smoking cessation and smoking reduction in pregnant smokers. Am J Addict. 2006;15:268–277. doi: 10.1080/10550490600754309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fitzsimons HE, Tuten M, Vaidya V, Jones HE. Mood disorders affect drug treatment success of drug-dependent pregnant women. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Brown RA. Nonclinical panic attack history and smoking cessation: An initial examination. Addict Behav. 2004;29:825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peters MJ, Morgan LC. The pharmacotherapy of smoking cessation. Med J Aust. 2002;176:486–490. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]