Abstract

Background

Cardiac repolarization, the process by which cardiomyocytes return to their resting potential after each beat, is a highly regulated process that is critical for heart rhythm stability. Perturbations of cardiac repolarization increase the risk for life-threatening arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. While genetic studies of familial long QT syndromes have uncovered several key genes in cardiac repolarization, the major heritable contribution to this trait remains unexplained. Identification of additional genes may lead to a better understanding of the underlying biology, aid in identification of patients at risk for sudden death, and potentially enable new treatments for susceptible individuals.

Methods and Results

We extended and refined a zebrafish model of cardiac repolarization by using fluorescent reporters of transmembrane potential. We then conducted a drug-sensitized genetic screen in zebrafish, identifying 15 genes, including GINS3, that affect cardiac repolarization. Testing these genes for human relevance in two concurrently completed genome wide association studies revealed that the human GINS3 ortholog is located in the 16q21 locus which is strongly associated with QT interval.

Conclusions

This sensitized zebrafish screen identified 15 novel myocardial repolarization genes. Among these genes is GINS3, the human ortholog of which is a major locus in two concurrent human genome wide association studies of QT interval. These results reveal a novel network of genes that regulate cardiac repolarization.

Keywords: Genes, Action Potential, Electrophysiology, Ion Channels

Introduction

The electrocardiographic QT interval duration is a predictor of mortality in familial long QT (LQT) syndromes1, as well as in a wide range of acquired heart diseases2,3. QT prolongation by drugs can also lead to fatal arrhythmias and has been a major cause of the withdrawal of medications from the market in the last decade4. Virtually all drugs that cause this adverse effect inhibit the rapid component of the delayed rectifier current, IKr5.

The QT interval is a summation of individual cellular action potential (AP) durations (APD) and is known to depend on the function of multiple ion channels and their accessory proteins. Much of our current understanding of cardiac repolarization comes from the study of familial long QT (LQT) syndromes6,7. These disorders are marked by abnormal cardiac repolarization and a high incidence of sudden death8. While the majority of LQT disorders result from mutation of ion channel genes, there is increasing recognition of the role of non-ion channel mechanisms such as ankyrin B9, and the caveolar scaffolding protein caveolin 310.

The zebrafish has been shown to recapitulate much of the complexity of higher vertebrates11, yet still retains the potential for exploring integrative physiology on a genomic scale12,13. Here, we studied cardiac repolarization as a complex trait using a functional screen to identify novel genetic determinants.

Methods

Aquaculture

All experiments were performed in Tuebingen AB zebrafish raised at 28C and maintained using standard methods. Embryos were staged according to morphological criteria (somite number) and by timing in hours post fertilization (hpf).

Voltage mapping

Individual hearts were isolated by microdissection in modified Tyrodes solution (136 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.3 mM NaH2PO4, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1mM MgCl2, 5mM glucose, 10mM HEPES, 2% BSA) these solutions are based on measurements from zebrafish serum14 and also previous studies of zebrafish cardiac physiology15,16. Dofetilide (a gift from Pfizer, Groton, CT) was added where indicated from a 25mg/ml stock in DMSO for 30 minutes prior to imaging. Cardiac motion was arrested by use of the myofibrillar ATPase inhibitor 2, 3-butanedione monoxime (Sigma) at 15–17mM. Hearts were stained with a 7μM solution di-4-ANEPPS (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon) for 10 minutes immediately prior to imaging. The preparations were placed in a custom pacing and imaging chamber and voltage mapping of cardiac electrical activity was performed using this chamber and a CCD camera (CardioCCD-SMQ, RedShirt Imaging, Decatur, GA) mounted on a Nikon TE2000 inverted microscope. The hearts were field paced at 60 min−1 (Grass S48K Stimulator, West Warwick, RI) unless otherwise indicated. Samples were illuminated using a 120W metal-halide Exfo X-Cite 120 lamp with a 480nm/40 excitation filter and the fluorescence image filtered through a 535nm/50 emission filter. Data were acquired at a frame rate of 125Hz. Subsequent analyses were performed using Cardioplex Software, including exponential subtraction of baseline photobleaching. Measurements of action potential durations were taken as the average of three or more successive beats for each sample. To improve signal to noise ratio in 48hpf hearts, signal averaging of 5 successive action potentials was performed using Clampfit (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale CA). Action potential duration was calculated at 90% repolarization (APD90).

Repolarization screen

The methods for the generation of the insertional mutant library and identification of the mutated genes have been reported previously17. Embryos were obtained from the natural spawning of heterozygous carriers, setup in pair-wise crosses. Embryos were collected, exposed to 12uM dofetilide at 36hpf and 20 mutant embryos from each clutch scored for heart rate effects and the presence or absence of 2:1 AV block at 48hpf as previously described13. In wild-type embryos this dose of dofetilide results in 2:1 AV block in 100% of fish due to marked prolongation of ventricular refractory periods (Figure 1b). Mutants with abnormal cardiac responses to dofetilide were confirmed on at least two occasions in multiple clutches.

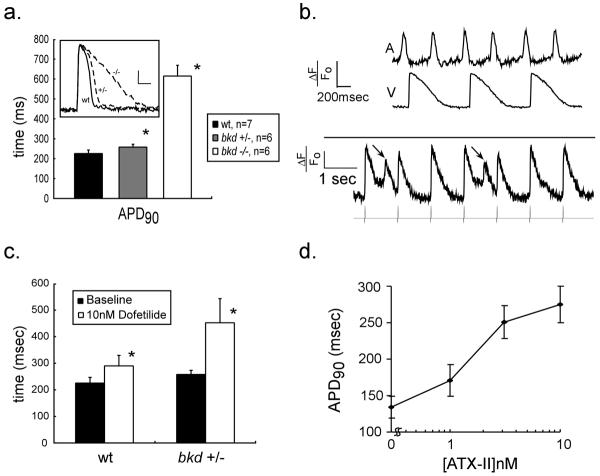

Figure 1. Parallels between zebrafish and human cardiac repolarization.

(1a) Ventricular action potential durations (APD) in wildtype (wt) and breakdance heterozygotes (+/−) and homozygotes (−/−) at 6 days post fertilization. * denotes p<0.05. (Inset) Typical ventricular action potentials are displayed for wildtype (wt), breakdance heterozygote (+/−) and homozygote (−/−) embryos. The heterozygote action potential is subtly prolonged, while the homozygote recording shows marked action potential prolongation. Vertical calibration bar denotes 20% ΔF/F0, horizontal bar denotes 100ms. (1b) Upper panel: simultaneous atrial and ventricular voltage recordings from a breakdance (−/−) heart showing the mechanism of 2:1 atrioventricular block: action potentials are so prolonged in the ventricle that alternate atrial impulses encroach on the refractory plateau of the previous ventricular repolarization. Lower panel: Early afterdepolarizations (EADs) (arrows) observed in breakdance (−/−) embryos during ventricular pacing; the pacing train is shown below the action potential recording. EADs appear as spontaneous depolarizations occurring before repolarization is complete and prior to the subsequent paced beat. (1c) Heterozygote breakdance embryos display increased sensitivity to IKr block (10nM dofetilide). (1d) Ventricular action potentials prolong in a dose-dependent fashion with ATX-II. Hearts were paced at 120bpm in ATX-II experiments. All values are expressed as mean +/− S.D.

Zebrafish Nitric Oxide Synthase 1 Adaptor Protein identification

The zebrafish nitric oxide synthase 1 adaptor protein (NOS1AP) gene was identified by homology search of the Ensembl database using the human NOS1AP peptide sequence as a query. The strongest homology was found to be a predicted gene on linkage group 6 that encodes a putative 506 amino acid protein bearing 71% identity and 80% similarity to the human sequence.

Morpholino knockdown

Morpholinos (Gene-Tools, LLC, Philomath OR) were resuspended in sterile water to a concentration of 1 mM and diluted to 10–100 uM with 1X Danieau's [58 mM NaCl, 0.7 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.6 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.5 mM Hepes, pH 7.6]. The morpholinos were injected at the single cell stage in a volume of approximately 5 nl. Morpholino sequences were as follows; NOS1AP 1 exon donor 5′-AATAAATTCACGTTACCTTTGCTTC-3′, NOS1AP ATG 5′-TTGTACTTTGTTTTTGCAGGCATGG-3′, Mismatch Control 5′-AAaAAATTgACcTTACgTTTGgTTC – 3′, GINS3 exon 2 donor Morpholino 5′-TACGACTACTCAAGGCTCACCTGGA – 3′. The effects of morpholinos on mRNA levels were assayed using quantitative real-time RT-PCR from injected embryos with beta-actin as a control.

Analysis of association data from the Genome Wide Association Studies consortia QT-Genetics (QTGEN) and QT-Sudden Cardiac Death (QTSCD)

Human orthologs of the 15 zebrafish repolarization genes were identified in the current human NCBI genome assembly. Surrounding genomic regions (± 150Mb) from the start and stop codons were annotated (a total of 5.0 Gb of genomic sequence). The single most significant SNP at each locus was identified in the QTSCD GWAS and reported. For the GINS3 locus, the most significant SNP in both QTSCD and QTGEN datasets was meta-analyzed, and the resulting best p-value reported. QT association results from all SNPs at all loci tested (4171 SNPs) were used to generate a quantile-quantile plot of observed vs. expected signals. This procedure was repeated excluding the GINS3 locus to detect additional associations.

Network annotation

The putative orthologs of each zebrafish repolarization gene in yeast, C. elegans, Drosophila, mouse and human were identified through reciprocal best match BLAST searches. Databases of genetic or physical interactions (Biomolecular Object Network Databank (BOND, http://bond.unleashedinformatics.com; Wormbase release WS160, http://www.wormbase.org; Gene Orienteer v1.6, http://www.geneorienteer.org/index.php) were searched to identify pathway members. (see Supplemental data Table 2) and a simple network diagram constructed. Pairwise genetic interactions between orthologs in multiple species were denoted using a single line. Physical interactions between orthologs were signified using a heavy line.

Results

The zebrafish models multiple aspects of human repolarization

While previous work has demonstrated parallels between zebrafish and human cardiac electrophysiology15,18,19, there is still no simple method for recording QT interval, or its cellular correlate, action potential duration (APD) in embryonic zebrafish. We therefore developed optical voltage mapping for high-resolution electrophysiologic analysis of the zebrafish heart (Supplemental Figure 1).

We initially recorded cardiac action potentials in the zebrafish mutant breakdance which carries a mutation in KCNH2 11,20, the major subunit responsible for IKr, and a known QT interval modifier21–23. Homozygous breakdance embryos display striking increases in APD compared to wild-type siblings (615 ± 66msec vs 225 ± 21msec, p=1.2 × 10−8) (Figure 1a). There was also evidence of action potential “triangulation,” a hallmark of arrhythmic risk characterized by replacement of the plateau phase of the action potential with slow, linear repolarization (Figure 1a). We also observed spontaneous early afterdepolarizations, the triggers of torsade de pointes (Figure 1b) in the bkd −/− zebrafish hearts.7. Optically measured action potential durations correlate well with previously reported intracellular recordings from wildtype zebrafish ventricular myocytes15.

We verified the predicted heightened sensitivity of heterozygote breakdance mutants to IKr block4. At baseline, breakdance heterozygotes display minimal APD prolongation (258 ± 16msec vs. 226 ± 21msec, p=1.0 × 10−4), but exposure to the potent and specific IKr blocker dofetilide at 10 nM (similar to circulating plasma levels of the drug in clinical use) prolonged their action potentials by 194 ± 92 msec (+75%), compared to an increase of 64 ± 45msec (+28%) in wild type (Figure 1c).

Treatment of zebrafish with sea anemone toxin (ATX-II), a toxin that interferes with sodium channel inactivation24 resulted in a dose-dependent increase in the APD, extending the parallels with human QT interval to include the LQT3 syndrome (Figure 1d).

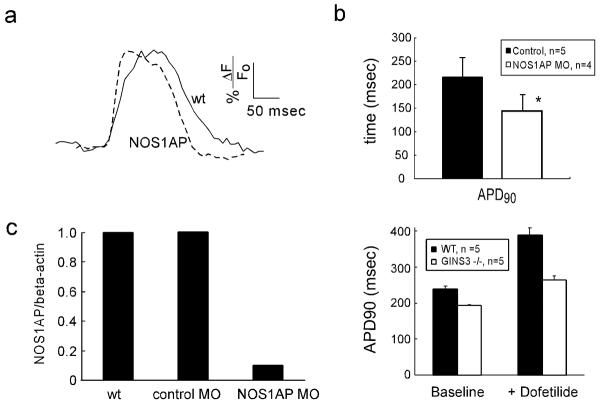

Variation at a locus in the Nitric Oxide Synthase 1 Adaptor Protein (NOS1AP) gene has been associated with QT interval variation in humans25. Morpholino knockdown of zebrafish NOS1AP shortened ventricular action potentials compared to wild type (142 ± 34msec vs 238 ± 41msec, p=0.001) (Figure 2a and 2b), and caused a reproducible increase in the upstroke slope of the action potential. Morpholino injection resulted in loss of >90% of processed NOS1AP message (Figure 2c). Results were confirmed with a second non-overlapping morpholino (APD = 194ms ± 27, p=0.03 vs wild-type), while a 5-basepair mismatch control morpholino did not alter APD or NOS1AP mRNA levels (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Genetic Modifiers of Repolarization.

(2a) Representative voltage recordings from wild type and NOS1AP morphant hearts are shown. (2b) Action potentials are shortened in NOS1AP morphant hearts compared to mismatch morpholino injected controls. (2c) NOS1AP morpholino injection results in specific knockdown of processed NOS1AP mRNA. qPCR results are displayed in arbitrary units normalized to beta-actin levels. (2d) Ventricular action potentials are shortened in GINS3 homozygous mutants, both at baseline and after treatment with 20nM dofetilide, hearts are paced at 90ppm. All values are expressed as mean +/− S.D (* denotes p<0.05).

Phenotype driven screen for repolarization modifiers

To discover additional genetic determinants of cardiac repolarization, we conducted a screen of 294 zebrafish insertional mutants originally selected based on early recessive morphologic phenotypes 17. Because homeostatic mechanisms can mask important genetic effects, we used dofetilide to sensitize the screen. All fish were exposed to a dose of dofetilide (12uM) that causes uniform 2:1 atrioventricular (AV) block in wildtype embryos. This phenotype is reminiscent of 2:1 AV block observed in profound cases of pediatric long QT syndrome26–28. Resistance was defined as failure to develop 2:1 AV block, while sensitized embryos displayed higher grade or complete AV block. Thirteen resistant and two sensitized mutants were identified and confirmed in multiple clutches (Table 1). Of the original 294 mutants tested, 128 (44%) display clear morphologic cardiac defects, while the remaining 166 do not. Of the 15 drug response mutants we identified, 8 had morphologic defects, while the remaining 7 did not. In each instance the drug response effects co-segregated with known mutant phenotypes, and were confirmed with multiple alleles when available (Table 1). Non-specific effects of viral insertion were excluded by the absence of any effect on drug response in the majority of mutant lines. Among the drug-resistant mutants was an allele of a cerebral cavernous malformation gene CCM2, known in the zebrafish as valentine (vtn). Valentine has been previously implicated in the regulation of cardiomyocyte function and vascular morphogenesis during development.29 Optical mapping demonstrated abnormally short action potentials in vtn homozygotes (Supplemental Figure 2). The phenotypes were replicated in independent ethyl-nitrosourea (ENU) induced mutant alleles of vtn, and in known mutant lines in two other genes in this pathway: heart of glass (heg) and santa (san), (Supplemental data Table 1).29,30

Table 1.

Insertional mutants demonstrating abnormal dofetilide responses

| Gene | Allele | Genome ID | Response | Cardiac Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cdca8l | hi1780a | NM_1007456 | Resistant | None |

| NUF2 | hi2769 | BC050181 | Resistant | Mild bradycardia |

| Protein kinase C, iota | hi3208 | AF390109 | Resistant | A and V dilatation |

| Casein kinase I, alpha 1 | hi1002 | AY099516 | Resistant | Mild A and V dilatation |

| hi2069 | Resistant | Minimal bradycardia | ||

| Cerebral cavernous malformation 2 (Valentine) | hi296a | AY648715 | Resistant | A and V dilatation |

| Establishment of cohesion 1 | hi2865 | AY648804 | Resistant | Small ventricle |

| Poly(A) binding protein, cytoplasmic 1 | hi3202b | BC047811 | Resistant | A dilatation |

| Surfeit 6 | hi1769 | AY648750 | Sensitized | Pericardial edema |

| Small ventricle | ||||

| GINS complex subunit 3 | hi1241 | AY648732 | Resistant | None |

| Replication protein A1 | hi2618 | AY648787 | Resistant | Generalized necrosis |

| Suppressor of Ty 6 homolog | hi1621 | NM_145118 | Resistant | Mild A and V dilatation |

| hi2505b | Resistant | |||

| Survivin | hi1326 | AY057057 | Resistant | Slowly progressive |

| hi2111 | Resistant | necrosis | ||

| hi3018 | Resistant | |||

| Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein D1 | hi601 | AF506225 | Resistant | Slowly progressive necrosis |

| Nucleolar protein 5A | hi3101 | AY648814 | Resistant | Mild contractile failure |

| Tryptophan rich basic protein | Hi1482 | AY648739 | Sensitized | Baseline bradycardia |

| Wild-type | NA | N/A | N/A | |

All fish were exposed to a dose of dofetilide (12uM) which results in uniform AV block in wild-type embryos. Resistance was defined as failure to develop 2:1 AV block, while sensitized embryos displayed higher grade AV block or ventricular standstill (complete AV block). All findings were significant at p<0.001 when compared with wild type siblings. A = atrial, V = ventricular.

In silico analysis reveals a network of repolarization genes

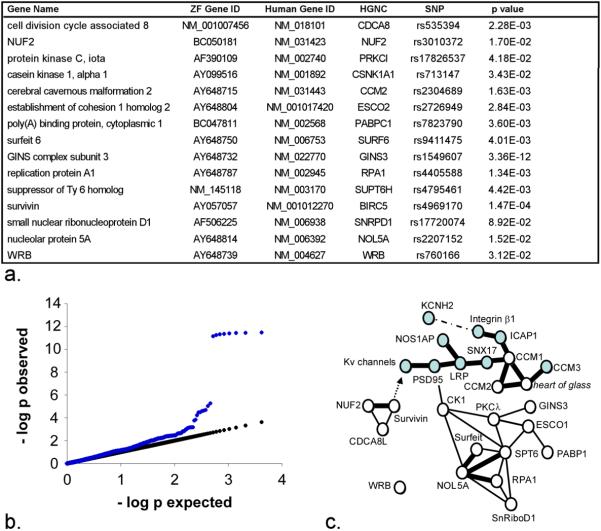

In order to better understand potential relationships between these 15 genes we systematically evaluated potential pair-wise interactions between the genes we identified and known repolarization genes, including NOS1AP, using public databases of experimental genetic and physical interactions. Pair-wise interactions between gene orthologs in yeast, C. elegans, Drosophila, mouse and human were identified and used to construct a network diagram with genetic interaction indicated by a solid line, and physical interactions indicated by a bold line (Figure 3c). These analyses suggest a network of transmembrane and cytoplasmic proteins that modulate ion channel function, perhaps through interactions with integrin pathways (Supplemental Data Table 2).

Figure 3. Tests of 15 genes discovered in zebrafish reveals role in human QT interval duration.

(3a) Table of human orthologs of zebrafish repolarization genes with gene ID number and HGNC name. The SNPs column lists the SNP with strongest evidence for QT interval association in the QTSCD GWAS along with the resulting unadjusted p values. (3b) Quantile-quantile plot of observed versus expected p values. Observed p-values from the QTSCD GWAS, in blue, from tests of all SNPs lying within 150kb of the human orthologs of zebrafish repolarization genes are plotted against p values that would be anticipated by chance alone. Departures from the linear, expected p values (black line) are due to markers with a signal for genetic association. (3c) Interactions between known repolarization genes (blue symbols) and the genes identified in the current study are depicted. Single lines indicate genetic interactions supported by data from multiple model organisms. Bold lines show direct physical interactions. A dashed line represents a physical interaction that may not be direct. The arrow represents a downstream regulatory effect, the mechanism of which is unknown. Supporting data are summarized in Supplemental Table 2.

Testing zebrafish repolarization genes in human cohorts

Two large GWAS of the human QT interval, a quantitative measure of cardiac repolarization, have been completed in 13,685 subjects in the QTGEN consortium31 and in 15,854 individuals in the QTSCD consortium.32 We identified human orthologs of the 15 zebrafish repolarization genes and searched for association signals with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within 150kb of each gene (Figure 3a). In both GWAS, highly significant association was found in an interval including the GINS3 gene (p = 3×10−15 (QTGEN), p = 2×10−12 (QTSCD), meta-analysis p = 3×10−25). To aid determination of the significance of these associations, we generated a quantile-quantile plot (Figure 3b) that demonstrates deviation of the observed p-values from those expected by chance alone. No other significant associations were detected (Figure 3a), as demonstrated by a quantile-quantile plot excluding SNPs from the 16q21 locus (Supplemental Figure 3).

Given the finding that GINS3 lies within a human locus associated with variation in the QT interval, we tested GINS3 mutants for differences in action potential duration. Optical mapping in GINS3 −/− embryos revealed shorter ventricular action potential durations compared to wild type controls (193 +/− 2 msec vs. 238 +/− 8 msec, respectively, p = 3.5 × 10−5, N = 5 embryos). In the presence of 20nM dofetilide, both GINS3 −/− and wild type embryos showed prolongation of APD90 (264 +/− 12 vs. 389 +/− 20 msec, p = 0.016, Figure 2d). Morpholino knockdown of GINS3 phenocopied the failure to develop 2:1 AV block upon dofetilide challenge (12uM) in three separate trials with 38 of 38 wild type controls exhibiting 2:1 AV block while 33 of 43 GINS3 knockdown embryos did not (p< 10−4, Fisher's exact test) (Supplemental Figure 4a). RT-PCR confirmed exclusion of exon 2 in morpholino injected embryos (Supplemental Figure 4b and c). GINS3 mutants and morphants display no other cardiac phenotype.

Discussion

Voltage mapping enabled high-resolution measurement of zebrafish cardiac repolarization and demonstrated the accurate modeling of drug-induced QT prolongation, as well as two genetic LQT syndromes. These results suggest that the zebrafish, in contrast to other genetically tractable organisms, may prove to be a faithful model of human cardiac repolarization.

A fundamental limitation of genetic association studies is that they can neither conclusively identify the causative gene, nor can they assess the relationship between levels of gene expression and the observed phenotype. In the zebrafish, loss of NOS1AP expression leads to APD shortening. Interestingly, APD shortening was the observed phenotype of NOS1AP overexpression in guinea pig myocytes33. These differing results may reflect the fact that both loss and overexpression of adaptor proteins can cause misregulation of functional complexes, or may simply be due to differences in the model systems.

Our phenotype-driven screen identified 15 genes that regulate cardiac repolarization. The high percentage of positive results, fifteen of 294 mutants tested, may reflect a large proportion of cardiac phenotypes collected in the original insertional mutant screen. Cardiac phenotypes have historically had a high prevalence in morphologic screens11,34, and repolarization abnormalities are known to accompany many disorders of cardiac form and function7,35. However, only half of the repolarization mutants we identified displayed structural cardiac defects, and in particular, GINS3 mutants exhibited no other morphologic or other functional defects. In addition, many mutants with severe functional cardiac defects failed to display any altered response to dofetilide. One hundred and twenty eight mutants with morphologic cardiac defects were included in this screen, of which 8 (6.25%) had repolarization phenotypes.

Interestingly, the majority of mutants identified were resistant to dofetilide. There are a number of biases in our screen, chief among them that we studied only recessive alleles. The use of an IKr inhibitor in this screen may have resulted in an inherent bias toward the identification of dofetilide resistant mutations that could result from defects which increase repolarizing currents or decrease depolarizing currents. Additionally, the zebrafish appear to undergo a developmental transition at approximately 40 hours to an IKr sensitive state36. Prior to this point, the heart rhythm is insensitive to IKr block15,18,20. It is possible that some of the genes identified in this screen play a role in the transition to a dofetilide-sensitive state perhaps through the coordinate regulation of ion channel expression including IKr channel subunits.

The statistical evidence of association of the human 16q21 locus with QT interval in two independent GWAS is highly compelling. The causal gene, or genes, at this locus is not known, but several candidates exist including CNOT1, SETD6, NDRG4, and GINS3. Our data suggest that, despite the 127Kb between GINS3 and the most strongly associated polymorphism, GINS3 is likely the responsible gene. Such remote cis effects have been established for loci identified in GWAS of other human traits37. Alternatively, multiple genes may play a role at a given locus. The conserved synteny between GINS3 and NDRG4 in humans and zebrafish raises the possibility of more complex mechanisms. Indeed, NDRG4 knockdown in the zebrafish has been reported to cause a cardiac phenotype, although repolarization has not yet been studied38. The zebrafish may prove a useful model to explore potential gene-gene interactions as well as the underlying biologic mechanisms.

There are several limitations to note in this study. For instance, only one human ortholog of a zebrafish repolarization gene was found to be associated with QT interval. There are several potential explanations for this. First, there simply may not be common functional polymorphism present in the human genes to allow their identification – this is especially true of the genes that caused morphologic cardiac defects, for which there may be selective pressures against functional variants. In addition, effect sizes from variation in these genes may simply be too small to detect by GWAS. Of note, our study tested myocardial repolarization in the setting of pharmacologic IKr blockade, an approach that may identify genes with little or no effect on human resting QT interval. It will be interesting to see if the remaining zebrafish genes show association with QT interval in larger GWAS meta-analyses or from collections of patients taking IKr blocking drugs. Additionally, the possibility exists that some of the genes we have identified may be important in a developmental context but not in adult human repolarization. There is still a considerable amount of work to be done in order to understand the mechanisms by which each of the genes we have identified affect cardiac repolarization.

The explosion of GWAS results in the last few years has led to speculation about efficient methods to study the biology underlying novel associations. We believe that models such as the zebrafish, where faithful phenotypes can be demonstrated, may afford an opportunity not only for `functional fine mapping' but also for the systematic exploration of gene-gene, gene-environment and gene-drug interactions necessary for personalized medicine to become a reality.

The electrocardiographic QT interval duration is a predictor of mortality in rare familial long QT syndromes, but also in a wide range of acquired heart diseases. QT prolongation can also occur as an unintended drug side effect where it can lead to fatal arrhythmias. This drug side effect has been a major cause of the withdrawal of medications from the market in the last decade. Recent studies in large human cohorts have suggested that there are many genes that regulate the human QT interval, or cardiac repolarization. We and others have shown that cardiac repolarization in the zebrafish bears remarkable similarities to human physiology. We have developed techniques to study cardiac electrophysiology in the zebrafish and performed a genetic screen to aid in the discovery of new genes for repolarization. Using this approach we confirmed that the recently identified NOS1AP gene regulates cardiac electrophysiologic function and went on to perform a drug-sensitized screen for genes affecting repolarization. The results have revealed a network of 15 genes which modulate the response to the QT prolonging drug dofetilide. One of the genes in this network, GINS3, was also recently found in independent human studies to be associated with QT variation. The identification of these genes may lead to a better understanding of the underlying biology, aid in identification of patients at risk for sudden death, and potentially enable new treatments for susceptible individuals.”

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Christopher Newton-Cheh, MD MPH for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding Sources This work was supported by research grants from the NIH: HL65962 (to Drs. Roden, MacRae and Milan), GM075946 (to Drs. MacRae, Peterson, Rosenbaum and Milan) HL76361 (to Dr. Milan) and RR012589-6 (to Dr. Amsterdam). The SardiNIA study was supported by the National Institute of Aging contract N01-AG-1-2109 to the SardiNIA (“ProgeNIA”) team. SK is supported by a grant from the Fondation Leducq and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the context of the German National Genome Research Network (NGFN)(01GS0838).

Footnotes

Disclosures None.

References

- 1.Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Grillo M, Bloise R, Ronchetti E, Moncalvo C, Tulipani C, Veia A, Bottelli G, Nastoli J. Association of long QT syndrome loci and cardiac events among patients treated with beta-blockers. Jama. 2004;292:1341–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siscovick DS, Raghunathan TE, Rautaharju P, Psaty BM, Cobb LA, Wagner EH. Clinically silent electrocardiographic abnormalities and risk of primary cardiac arrest among hypertensive patients. Circulation. 1996;94:1329–33. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooksby P, Batin PD, Nolan J, Lindsay SJ, Andrews R, Mullen M, Baig W, Flapan AD, Prescott RJ, Neilson JM, Cowley AJ, Fox KA. The relationship between QT intervals and mortality in ambulant patients with chronic heart failure. The united kingdom heart failure evaluation and assessment of risk trial (UK-HEART) Eur Heart J. 1999;20:1335–41. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roden DM. Drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1013–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilke RA, Lin DW, Roden DM, Watkins PB, Flockhart D, Zineh I, Giacomini KM, Krauss RM. Identifying genetic risk factors for serious adverse drug reactions: current progress and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:904–16. doi: 10.1038/nrd2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating MT, Sanguinetti MC. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. Cell. 2001;104:569–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nerbonne JM, Kass RS. Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1205–53. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent GM. Hypothesis for the molecular physiology of the Romano-Ward long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:500–3. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohler PJ, Schott JJ, Gramolini AO, Dilly KW, Guatimosim S, duBell WH, Song LS, Haurogne K, Kyndt F, Ali ME, Rogers TB, Lederer WJ, Escande D, Le Marec H, Bennett V. Ankyrin-B mutation causes type 4 long-QT cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Nature. 2003;421:634–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vatta M, Ackerman MJ, Ye B, Makielski JC, Ughanze EE, Taylor EW, Tester DJ, Balijepalli RC, Foell JD, Li Z, Kamp TJ, Towbin JA. Mutant caveolin-3 induces persistent late sodium current and is associated with long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2006;114:2104–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen JN, Haffter P, Odenthal J, Vogelsang E, Brand M, van Eeden FJ, Furutani-Seiki M, Granato M, Hammerschmidt M, Heisenberg CP, Jiang YJ, Kane DA, Kelsh RN, Mullins MC, Nusslein-Volhard C. Mutations affecting the cardiovascular system and other internal organs in zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:293–302. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briggs JP. The zebrafish: a new model organism for integrative physiology. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R3–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00589.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burns CG, Milan DJ, Grande EJ, Rottbauer W, MacRae CA, Fishman MC. High-throughput assay for small molecules that modulate zebrafish embryonic heart rate. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:263–4. doi: 10.1038/nchembio732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boisen AM, Amstrup J, Novak I, Grosell M. Sodium and chloride transport in soft water and hard water acclimated zebrafish (Danio rerio) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1618:207–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnaout R, Ferrer T, Huisken J, Spitzer K, Stainier DY, Tristani-Firouzi M, Chi NC. Zebrafish model for human long QT syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11316–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702724104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sedmera D, Reckova M, deAlmeida A, Sedmerova M, Biermann M, Volejnik J, Sarre A, Raddatz E, McCarthy RA, Gourdie RG, Thompson RP. Functional and morphological evidence for a ventricular conduction system in zebrafish and Xenopus hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1152–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00870.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amsterdam A, Nissen RM, Sun Z, Swindell EC, Farrington S, Hopkins N. Identification of 315 genes essential for early zebrafish development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12792–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403929101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milan DJ, Peterson TA, Ruskin JN, Peterson RT, MacRae CA. Drugs that induce repolarization abnormalities cause bradycardia in zebrafish. Circulation. 2003;107:1355–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061912.88753.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassel D, Scholz EP, Trano N, Friedrich O, Just S, Meder B, Weiss DL, Zitron E, Marquart S, Vogel B, Karle CA, Seemann G, Fishman MC, Katus HA, Rottbauer W. Deficient Zebrafish Ether-a-Go-Go-Related Gene Channel Gating Causes Short-QT Syndrome in Zebrafish Reggae Mutants. Circulation. 2008 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.752220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langheinrich U, Vacun G, Wagner T. Zebrafish embryos express an orthologue of HERG and are sensitive toward a range of QT-prolonging drugs inducing severe arrhythmia. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;193:370–82. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bezzina CR, Verkerk AO, Busjahn A, Jeron A, Erdmann J, Koopmann TT, Bhuiyan ZA, Wilders R, Mannens MM, Tan HL, Luft FC, Schunkert H, Wilde AA. A common polymorphism in KCNH2 (HERG) hastens cardiac repolarization. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59:27–36. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeufer A, Jalilzadeh S, Perz S, Mueller JC, Hinterseer M, Illig T, Akyol M, Huth C, Schopfer-Wendels A, Kuch B, Steinbeck G, Holle R, Nabauer M, Wichmann HE, Meitinger T, Kaab S. Common variants in myocardial ion channel genes modify the QT interval in the general population: results from the KORA study. Circ Res. 2005;96:693–701. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000161077.53751.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newton-Cheh C, Guo CY, Larson MG, Musone SL, Surti A, Camargo AL, Drake JA, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, D'Agostino RB, Sr., Hirschhorn JN, O'Donnell CJ. Common genetic variation in KCNH2 is associated with QT interval duration: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116:1128–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.710780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catterall WA, Beress L. Sea anemone toxin and scorpion toxin share a common receptor site associated with the action potential sodium ionophore. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:7393–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arking DE, Pfeufer A, Post W, Kao WH, Newton-Cheh C, Ikeda M, West K, Kashuk C, Akyol M, Perz S, Jalilzadeh S, Illig T, Gieger C, Guo CY, Larson MG, Wichmann HE, Marban E, O'Donnell CJ, Hirschhorn JN, Kaab S, Spooner PM, Meitinger T, Chakravarti A. A common genetic variant in the NOS1 regulator NOS1AP modulates cardiac repolarization. Nat Genet. 2006;38:644–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lupoglazoff JM, Denjoy I, Villain E, Fressart V, Simon F, Bozio A, Berthet M, Benammar N, Hainque B, Guicheney P. Long QT syndrome in neonates: conduction disorders associated with HERG mutations and sinus bradycardia with KCNQ1 mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:826–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trippel DL, Parsons MK, Gillette PC. Infants with long-QT syndrome and 2:1 atrioventricular block. Am Heart J. 1995;130:1130–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott WA, Dick M., 2nd Two:one atrioventricular block in infants with congenital long QT syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:1409–10. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mably JD, Chuang LP, Serluca FC, Mohideen MA, Chen JN, Fishman MC. santa and valentine pattern concentric growth of cardiac myocardium in the zebrafish. Development. 2006;133:3139–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.02469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mably JD, Mohideen MA, Burns CG, Chen JN, Fishman MC. heart of glass regulates the concentric growth of the heart in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2138–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newton-Cheh C, Eijgelsheim M, Rice KM, de Bakker PI, Yin X, Estrada K, Bis JC, Marciante K, Rivadeneira F, Noseworthy PA, Sotoodehnia N, Smith NL, Rotter JI, Kors JA, Witteman JC, Hofman A, Heckbert SR, O'Donnell CJ, Uitterlinden AG, Psaty BM, Lumley T, Larson MG, Stricker BH. Common variants at ten loci influence QT interval duration in the QTGEN Study. Nat Genet. 2009;41:399–406. doi: 10.1038/ng.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfeufer A, Sanna S, Arking DE, Muller M, Gateva V, Fuchsberger C, Ehret GB, Orru M, Pattaro C, Kottgen A, Perz S, Usala G, Barbalic M, Li M, Putz B, Scuteri A, Prineas RJ, Sinner MF, Gieger C, Najjar SS, Kao WH, Muhleisen TW, Dei M, Happle C, Mohlenkamp S, Crisponi L, Erbel R, Jockel KH, Naitza S, Steinbeck G, Marroni F, Hicks AA, Lakatta E, Muller-Myhsok B, Pramstaller PP, Wichmann HE, Schlessinger D, Boerwinkle E, Meitinger T, Uda M, Coresh J, Kaab S, Abecasis GR, Chakravarti A. Common variants at ten loci modulate the QT interval duration in the QTSCD Study. Nat Genet. 2009;41:407–14. doi: 10.1038/ng.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang KC, Barth AS, Sasano T, Kizana E, Kashiwakura Y, Zhang Y, Foster DB, Marban E. CAPON modulates cardiac repolarization via neuronal nitric oxide synthase signaling in the heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4477–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709118105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullins MC, Hammerschmidt M, Haffter P, Nusslein-Volhard C. Large-scale mutagenesis in the zebrafish: in search of genes controlling development in a vertebrate. Curr Biol. 1994;4:189–202. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin AB, Garson A, Jr., Perry JC. Prolonged QT interval in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy in children. Am Heart J. 1994;127:64–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milan DJ, Giokas AC, Serluca FC, Peterson RT, MacRae CA. Notch1b and neuregulin are required for specification of central cardiac conduction tissue. Development. 2006;133:1125–32. doi: 10.1242/dev.02279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, Zhu J, Lum PY, Yang X, Pinto S, MacNeil DJ, Zhang C, Lamb J, Edwards S, Sieberts SK, Leonardson A, Castellini LW, Wang S, Champy MF, Zhang B, Emilsson V, Doss S, Ghazalpour A, Horvath S, Drake TA, Lusis AJ, Schadt EE. Variations in DNA elucidate molecular networks that cause disease. Nature. 2008;452:429–35. doi: 10.1038/nature06757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qu X, Jia H, Garrity DM, Tompkins K, Batts L, Appel B, Zhong TP, Baldwin HS. Ndrg4 is required for normal myocyte proliferation during early cardiac development in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2008;317:486–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.