Summary

Sondermann and colleagues have characterized FimX, a protein with degenerate GGDEF and EAL domains (Navarro et al., 2009). The study confirms the expected domain folds lacking conserved catalytic residues for c-di-GMP synthesis/degradation and also defines domain arrangements, providing insight to regulatory mechanisms.

Signaling via second messengers is a common signal transduction scheme exploited by both prokaryotes and eukaryotes for basic regulation of cellular processes and complex network signaling. The soluble cyclic dinucleotide bis-(3’-5’)-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) has emerged as a key bacterial second messenger that triggers the transition between motile and sessile lifestyles and regulates other cellular functions such as virulence and cell cycle progression (Hengge, 2009). In contrast to the rather simple and linear pathways involving the other bacterial second messengers, cAMP and ppGpp, c-di-GMP signaling appears to be more complex, often involving multiple c-di-GMP-metabolizing enzymes and receptors that connect distinct pathways. This is reflected in the large number and diverse organization of GGDEF and EAL or HD-GYP domains that catalyze synthesis and degradation of c-di-GMP molecules. In eubacteria, especially in proteobacteria, GGDEF and EAL domains are among the most abundant signal transduction domains (Galperin, 2005). In this issue of Structure, Navarro and colleagues report the first structural description of degenerate GGDEF and EAL domains in a protein that presumably functions as a target of c-di-GMP signaling (Navarro et al., 2009).

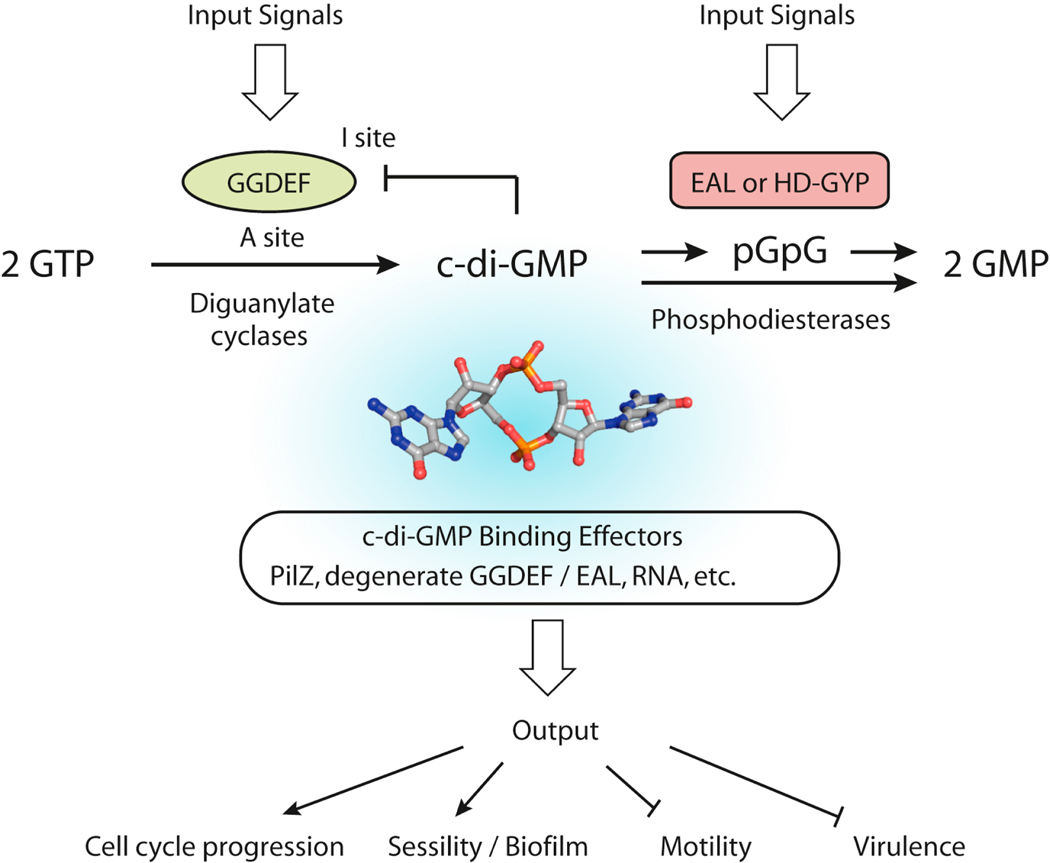

The GGDEF domain is named after the conserved sequence motif that is essential for the active site (A site) of diguanlyate cyclases (DGCs), which catalyze the synthesis of c-di-GMP from two molecules of GTP (Figure 1). These domains also contain a conserved secondary c-di-GMP-binding site (I site) for product inhibition of the DGC activity. The EAL domain is associated with the c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity that is responsible for the hydrolysis of c-di-GMP to the linear product pGpG. Further breakdown of pGpG to two GMPs is accomplished by nonspecific cellular PDEs. Both DGC and PDE activities can be regulated allosterically by a wide variety of signal input domains linked to the GGDEF and EAL domains. The temporal and spatial distribution of multiple DGCs and PDEs allow cells to respond and integrate different signals into the dynamic c-di-GMP levels, which are perceived by various c-di-GMP-binding effector proteins and RNA segments in specific riboswitches to elicit output responses.

Figure 1.

Basic Signaling Scheme of the Second Messenger c-di-GMP

In addition to the conventional GGDEF and EAL domains that contain the conserved residues for enzymatic activities, many degenerate GGDEF and EAL domains deviate from the consensus and appear to be enzymatically inactive but still involved in c-di-GMP signaling. It is believed that degenerate GGDEF and EAL domains function through direct macromolecular interactions and some of these catalytically inactive proteins still possess the capability of binding the substrates. Binding of GTP to A sites or c-di-GMP to I sites of degenerate GGDEF domains and c-di-GMP-binding to inactive EAL domains have been documented for allosteric control of adjacent domains (Christen et al., 2005; Duerig et al., 2009; Newell et al., 2009), further contributing to the diversity and complexity of c-di-GMP regulatory mechanisms.

Navarro and colleagues report crystal structures and spatial arrangements of degenerate GGDEF and EAL domains from FimX, a protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa that regulates twitching mobility and biofilm formation. FimX contains an N-terminal two-component receiver domain (REC), a PAS domain and degenerate GGDEF and EAL domains in tandem at the C-terminus. The full-length protein lacks both DGC and PDE activities but binds to c-di-GMP with a KD of 125 nM. With the degenerate GGDEF domain lacking the characteristic binding motifs at both the A and I sites, the high affinity c-di-GMP-binding site of FimX is found to localize to the EAL domain. Structures of both apo- and c-di-GMP-bound EAL domains indicate little conformational differences between the two. It is not surprising that an overall structure similar to the TIM-barrel fold of conventional EAL domains is maintained (Barends et al., 2009; Minasov et al., 2009), while crucial residues for metal ion coordination are absent at the catalytic site. Thus, FimX EAL lacks features that are essential for the two-metal assisted catalytic mechanism proposed for PDE activity. However, the residues important for c-di-GMP interactions are well conserved within the binding pocket, highlighting the sequence and molecular signatures for c-di-GMP binding in EAL domains, conventional or degenerate.

Other than the catalytic residues, the major difference between the conventional and the degenerate FimX EAL domains resides in the quaternary structures. Although it was initially shown that one enzymatically active EAL protein, YahA, exists primarily as a monomer (Schmidt et al., 2005), structures of all three characterized conventional EAL proteins, BlrP1, YkuI and tdEAL, display a similar dimer interface (Barends et al., 2009; Minasov et al., 2009). Moreover, a loop leading to the interface is crucial for both dimerization and proper positioning of the catalytic metal ions (Barends et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2009), offering an excellent target for allosteric control of the PDE activity. However, it remains to be seen whether the dimerization is universally required for all active EAL proteins. The degenerate EAL domain of FimX exists as a monomer in solution while the full-length FimX dimerizes via its N-terminal domains. Modeling with SAXS data is consistent with the N-terminal REC domains mediating dimerization with the EAL domains separated and located at distant ends of the extended structure. This arrangement is in stark contrast with the tight dimer interface observed in proteins with conventional, catalytically competent EAL domains.

Despite being monomeric in solution, FimXdual containing the GGDEF and EAL domains and apo-FimXEAL crystallize with a comparable dimer interface burying a large surface area. However, this interface is distinct from the one observed in recently reported conventional EAL structures. Interestingly, c-di-GMP binding and formation of this dimer appear to be mutually exclusive, owing to potential clashes between the nucleotide and the dimeric conformations. Therefore, Navarro et al. postulate that this interface might be used for interaction with other yet to be identified partners, possibly EAL-containing proteins. Binding of c-di-GMP could relieve the interaction, making either FimX or another EAL protein ready for subsequent functions. However, it is still not clear how the SAXS model of the full-length FimX dimer fits into this mechanism and whether the N-terminal REC and PAS domains play any role in the c-di-GMP-dependent regulation, as might be expected since dimerization via the REC domains has been shown to be important for regulation of enzyme activity in some GGDEF and EAL domains (Rao et al., 2009; Wassmann et al., 2007).

Multiplicity and diversity of GGDEF and EAL proteins greatly contribute to the complexity of c-di-GMP signaling. Many catalytically inactive degenerate domains are being recognized as essential components of c-di-GMP regulatory networks and continuing efforts have been made to identify the sequence signatures for binding, synthesis and degradation of c-di-GMP molecules. This study provides a first step in characterization of degenerate GGDEF and EAL proteins and allows postulation of mechanistic models for regulation. However, great caution should be taken in extrapolating the regulatory details of one protein to other members of the family. GGDEF and EAL domains have low sequence identity within their families and appear highly plastic in regards to protein-protein interactions. Similar to the versatile regulatory mechanisms that occur in the other major bacterial signaling strategy, two-component phosphotransfer systems (Gao and Stock, 2009), diverse regulation methods are expected in c-di-GMP signaling.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barends TR, Hartmann E, Griese JJ, Beitlich T, Kirienko NV, Ryjenkov DA, Reinstein J, Shoeman RL, Gomelsky M, Schlichting I. Nature. 2009;459:1015–1018. doi: 10.1038/nature07966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen M, Christen B, Folcher M, Schauerte A, Jenal U. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30829–30837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerig A, Abel S, Folcher M, Nicollier M, Schwede T, Amiot N, Giese B, Jenal U. Genes Dev. 2009;23:93–104. doi: 10.1101/gad.502409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R, Stock AM. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;63:133–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengge R. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minasov G, Padavattan S, Shuvalova L, Brunzelle JS, Miller DJ, Basle A, Massa C, Collart FR, Schirmer T, Anderson WF. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:13174–13184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808221200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro MVAS, De N, Bae N, Wang Q, Sondermann H. Structure. 2009;17:xxx–xxxx. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell PD, Monds RD, O'Toole GA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3461–3466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808933106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao F, Qi Y, Chong HS, Kotaka M, Li B, Li J, Lescar J, Tang K, Liang ZX. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:4722–4731. doi: 10.1128/JB.00327-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AJ, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:4774–4781. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4774-4781.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassmann P, Chan C, Paul R, Beck A, Heerklotz H, Jenal U, Schirmer T. Structure. 2007;15:915–927. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]