SUMMARY

Poor protein solubility is a common problem in high resolution structural studies, formulation of protein pharmaceuticals, and biochemical characterization of proteins. One popular strategy to improve protein solubility is to use site-directed mutagenesis to make hydrophobic to hydrophilic mutations on the protein surface. However, a systematic investigation of the relative contributions of all twenty amino acids to protein solubility has not been done. Here, twenty variants at the completely solvent-exposed position 76 of Ribonuclease (RNase) Sa are made to compare the contributions of each amino acid. Stability measurements were also made for these variants, which occur at the i+1 position of a type II β-turn. Solubility measurements in ammonium sulfate solutions were made at high positive net charge, low net charge, and high negative net charge. Surprisingly, there was a wide range of contributions to protein solubility even among the hydrophilic amino acids. The results suggest that aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and serine contribute significantly more favorably than the other hydrophilic amino acids especially at high net charge. Therefore, to increase protein solubility, asparagine, glutamine, or threonine should be replaced with aspartic acid, glutamic acid or serine.

Keywords: protein solubility, amino acid hydrophobicity, amino acid hydration, halophilic adaptation, β-turn stability

Introduction

Protein solubility is a concern in every biochemical experiment. Protein solubility varies widely, ranging from almost complete insolubility to values of several hundreds of milligrams per milliliter. In fortunate cases, the protein of interest is sufficiently soluble for experiments, but often this is not the case. Also, low protein solubility is a factor in several types of disease. Therefore, methods that can be used to increase protein solubility are of great interest for high resolution structural studies1; 2, crystallization of membrane proteins3–8, pharmaceutical applications9–11, and treatment of human disease12–16. Protein solubility as a thermodynamic parameter is defined as the concentration of soluble protein that is in equilibrium with a crystalline solid phase under given conditions of pH, temperature, buffer concentration, and various additives1. Ionic strength, ionic composition, pH, and temperature are extrinsic factors that influence protein solubility. Here, we investigate the intrinsic determinants of protein solubility by studying how an amino acid on the surface of a folded protein influences solubility. Several studies have succeeded in using site-directed mutagenesis of surface residues to enhance protein solubility17–22, but a systematic study comparing the contribution of all twenty amino acids to protein solubility has not been published. Furthermore, several reviews have noted a lack of experimentally based, general rules for increasing protein solubility using site-directed mutagenesis2; 17; 23–26.

The number of proteins and biochemical systems identified and waiting to be characterized is increasing rapidly as the number of whole genome sequences increases. However, biochemical studies to characterize these new proteins, such as quantitative binding assays and high-resolution structural studies1; 2; 27; 28, are often hampered by low protein solubility. Up to 80% of nonmembrane proteins that have been identified so far are unsuitable for structural studies due to low solubility29–31. Similar problems related to poor protein solubility occur in the pharmaceutical industry where it has been estimated that more than 90% of all potential protein pharmaceuticals are unsuitable for preclinical or clinical development due to low solubility32. For example, human leptin is a protein therapeutic that is susceptible to aggregation – especially at high dosages in physiological conditions11. The crystal structure of this protein was determined only after introduction of a mutation (W100E) that increased the solubility of the protein33. The solubility of human leptin was successfully increased for its formulation as a protein therapeutic through several hydrophobic to hydrophilic mutations11. These mutations were chosen based on comparison to the more soluble murine leptin homolog.

We stress that the strategy for increasing protein solubility presented here may not apply to solubility problems involving inclusion body formation. For example, several studies have investigated problems related to poor protein solubility during overexpression of recombinant proteins in E. coli34; 35. In these cases, inclusion body formation is observed and protein yield is often low. Our results will not necessarily apply to solubility problems like these. This is because these problems are more related to low protein stability34, and hence low solubility of partially or completely unfolded protein as opposed to low solubility of the folded protein. Therefore, protein solubility problems during overexpression might be solved using approaches to increase protein stability as opposed to using the information in this study. Here, we suggest ways to alleviate poor solubility of folded proteins.

Making hydrophobic to hydrophilic mutations is the general approach to alleviate solubility problems encountered in high-resolution structural studies, biochemical characterization studies, and formulation of protein therapeutics. However, a systematic comparison of the contribution of all twenty amino acids is lacking. Furthermore, hydrophobic residues are usually targeted for replacement, but such residues are not often found on the protein surface. We have used Ribonuclease (RNase) Sa, a small enzyme with 96 amino acid residues and one disulfide bond, and measured solubility in ammonium sulfate solutions for 20 variants at position 76 of the protein (Figure 1). Ammonium sulfate is one of the most commonly used precipitating agents for protein crystallography36. Measurements at high positive net charge, low net charge, and high negative net charge have also been made. A threonine residue is located at position 76 of wild-type RNase Sa, and it is 2.5% hyperexposed to solvent compared to a model Ala-X-Ala peptide as determined by the program pfis37. Therefore, every amino acid introduced at position 76 is probably completely solvent exposed, thereby allowing comparison of the contributions to protein solubility of the entire side-chains of all twenty amino acids. Our results suggest that aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and serine, contribute most favorably to protein solubility. The results also suggest that they contribute significantly more favorably than other hydrophilic amino acids such as asparagine, glutamine, and threonine. These residues are probably better targets for replacement as they are found on the protein surface more often than hydrophobic residues38. Furthermore, the results suggest that the contribution of lysine and arginine to protein solubility is complex and depends dramatically on the net charge of the protein. Hopefully, this work will provide valuable insight for increasing protein solubility to enhance the crystallizability of proteins, to improve bioavailability of protein pharmaceuticals, and to allow biochemical characterization of poorly soluble proteins.

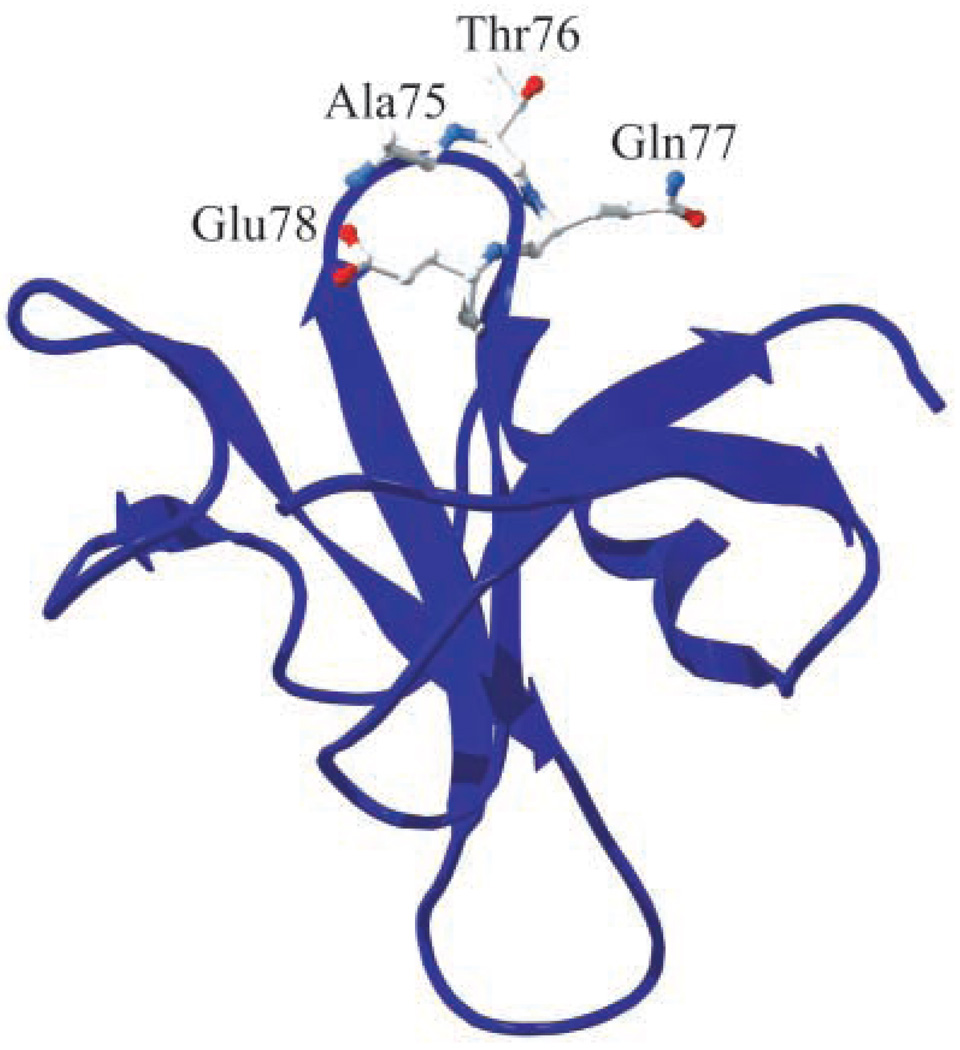

Figure 1.

Position 76 in RNase Sa and neighboring turn residues (Ala75, Gln77, and Glu78). The side chain of Thr76 is 2.5% hyper-exposed to solvent as determined by pfis37. The figure was generated using the Swiss-Pdb Viewer program66.

Results and Discussion

Determination of the stability of Thr76 variants at pH 7

To verify that none of the mutations at position 76 significantly destabilized RNase Sa, thermodynamic stability data were obtained for each variant. The thermodynamic parameters from thermal denaturation experiments for the Thr76 variants are shown in Table 1. Several variants (T76P, T76Y, T76F, T76W, T76A, T76H, T76D, and T76E) are more stable than the wild-type protein, while none of them are significantly less stable than wild-type. T76G is the only variant with decreased stability, but the mutation only destabilizes the protein by 0.3 kcal/mol.

Table 1.

Parameters characterizing the thermal unfolding of RNase Sa and Thr76 variants in 30 mM Mops (pH 7.0)

| Protein | ΔHma | ΔSmb | ΔTmc | ΔTmd | ΔΔG°e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 91 | 284 | 47.8 | ||

| T76P | 95 | 293 | 51.4 | 3.6 | 1.0 |

| T76Y | 97 | 299 | 50.8 | 3.0 | 0.9 |

| T76F | 95 | 293 | 50.6 | 2.8 | 0.8 |

| T76W | 93 | 288 | 50.1 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| T76A | 95 | 295 | 49.4 | 1.6 | 0.5 |

| T76H | 93 | 288 | 49.4 | 1.6 | 0.5 |

| T76E | 93 | 289 | 49.1 | 1.3 | 0.4 |

| T76D | 93 | 289 | 49.1 | 1.3 | 0.4 |

| T76K | 93 | 289 | 49.0 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| T76L | 94 | 292 | 48.8 | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| T76Q | 94 | 292 | 48.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| T76S | 92 | 286 | 48.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| T76R | 94 | 292 | 48.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| T76M | 91 | 283 | 48.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| T76N | 89 | 277 | 48.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| T76V | 93 | 289 | 48.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| T76I | 92 | 286 | 48.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| T76C | 64 | 199 | 47.7 | −0.1 | 0.0 |

| T76G | 88 | 275 | 46.9 | −0.9 | −0.3 |

ΔHm, enthalpy of unfolding at Tm (in kcal mol−1). The error is ± 5 kcal mol−1.

ΔSm = ΔHm/Tm (in cal mol−1 K−1). The error is ± 15 cal mol−1 K−1.

Tm = T (in °C), where ΔG° = 0. The error is ± 0.3 °C.

ΔTm = Tm(mutant) - Tm(wild-type) (in °C).

ΔΔG° = 0.284 (ΔSm for wild-type in kcal mol−1 K−1) * ΔTm. The error is ± 0.2 kcal mol−1.

Position 76 is the i+1 position of a type II β-turn. Recently, Guruprasad and Rajkumar did an extensive survey of turns in 426 proteins from the protein data bank39. For the i+1 position of type II turns, they found that alanine, glutamic acid, lysine, and proline are the amino acids that occupy this position most often39. Since T76P was the variant with the highest stability, it seems that proline might be preferred because it confers conformational stability to the turn due to favorable backbone torsion angles. For example, the ϕ angle of a proline residue is restricted to −60° due to the delta carbon being covalently bound to the amide nitrogen of the residue. Therefore, proline probably assumes the −60° ϕ angle that is required at the i+1 position of a type II β-turn with a reduced entropic cost relative to other more intrinsically flexible amino acids (see the Hutchinson and Thornton study40 for the ϕ, ψ angles of various turn types and positions). As for alanine, glutamic acid, and lysine, they might be found at this position often39, but our results suggest that they contribute only marginally to conformational stability (Table 1).

Surprisingly, the aromatic variants (tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan) had high stabilities similar to the proline variant despite the fact that aromatic residues are not highly preferred in the i+1 position of a type II β-turn39. Gibbs et. al41 investigated the role of amino acid substitutions in type II’ β-turns. Type II’ β-turns are mirror images of type II β-turns. Their results showed that an aromatic ring at the i+1 position of a type II’ β-turn provided stabilizing interactions for the turn. Furthermore, there is an aromatic residue at the i+1 position of another type II β-turn in RNase Sa (Tyr49). Tyr49 seems to provide stabilizing interactions at this position as a Y49N mutation causes a decrease in stability of 1 kcal/mol (ST, unpublished data). These results as well as the results of Gibbs et al.41 suggest that side chains with aromatic rings can provide stabilizing interactions at the i+1 position of a type II turn.

Effect of ammonium sulfate on RNase Sa stability

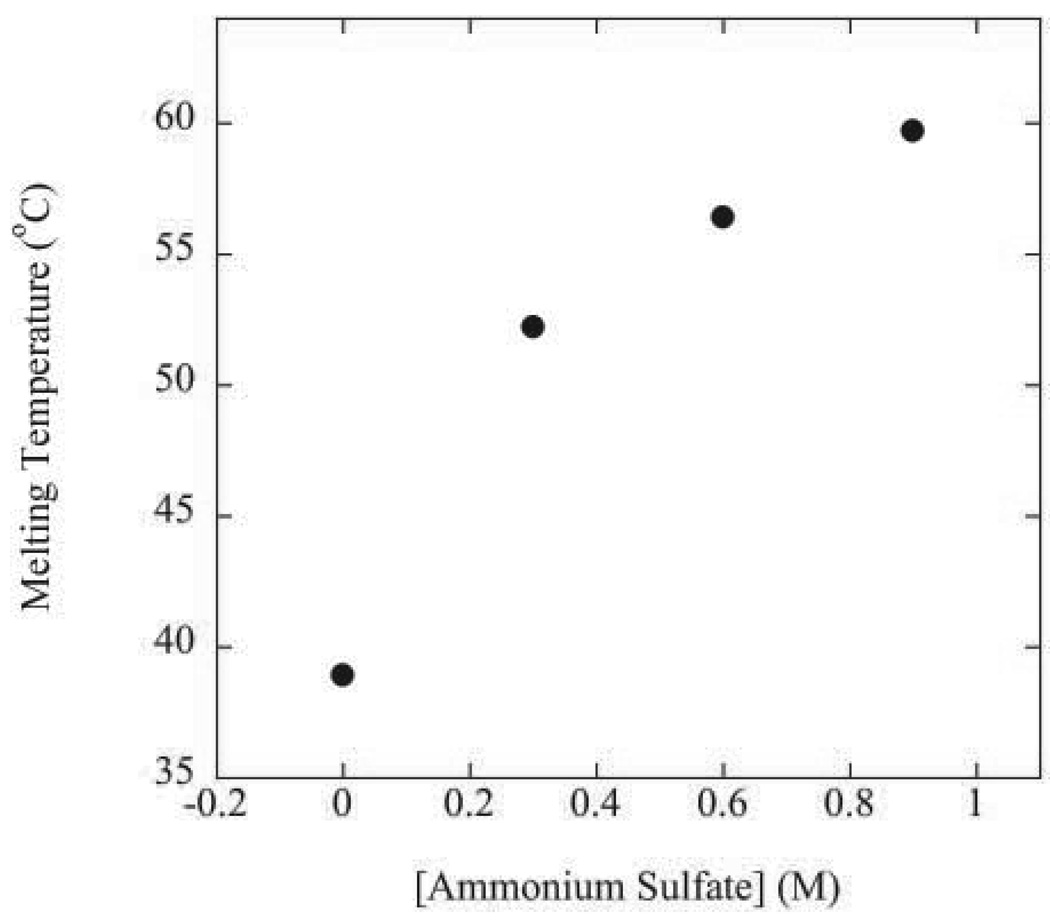

The solubility measurements were obtained in ammonium sulfate solutions. Sulfate salts increase the stability of proteins. This is presumably because sulfate anions strongly salt-out the hydrophobic groups in the protein while weakly salting-in peptide groups in the protein (see Baldwin42 and references therein). The salting-out of interior hydrophobic groups causes a strengthening of intramolecular hydrophobic interactions which increases protein stability. To measure the effect of ammonium sulfate on RNase Sa stability, thermal denaturations were performed up to 0.9 M ammonium sulfate for the T76D variant at pH 9.0. The T76D variant was used to avoid aggregation of the denatured state in ammonium sulfate solutions. The melting temperature of T76D Sa as a function of ammonium sulfate concentration at pH 9.0 is shown in Figure 2. The melting temperature of the enzyme increases as the ammonium sulfate concentration increases from 0 to 0.9 M. Thermal denaturation experiments could not be done at ammonium sulfate concentrations higher than 0.9 M due to excessive aggregation of the denatured state, but the stability of the protein is expected to increase further at higher ammonium sulfate concentrations given the mechanism by which sulfate salts stabilize proteins42. Given that all variants retain enzymatic activity, that none of the variants at position 76 are significantly destabilizing (Table 1), and that the protein is more stable at the other pH values (3, 4.25, and 7)43 used for the solubility experiments than pH 9.0, these results suggest that RNase Sa and all of the variants at position 76 are fully folded under the conditions of all of the solubility experiments.

Figure 2.

Effect of ammonium sulfate concentration on the melting temperature of T76D Sa in 50 mM diglycine buffer at pH 9.0.

Effect of initial protein concentration on solubility values

For the solubility measurements, the concentration of soluble protein was measured after precipitation with ammonium sulfate. Therefore, the initial concentration had to be higher than the solubility value. Since, the precipitate in these experiments was an amorphous solid phase as opposed to a crystalline solid phase, we had to ensure that the solubility values did not depend on the initial protein concentration44; 45. To verify this, measurements were made on samples that differed only in the initial protein concentration (Table 2). For example, in 1.75 M ammonium sulfate, a 5 mg/ml solution of RNase Sa and a 20 mg/ml solution of RNase Sa result in the same concentration of soluble protein (~1.3 mg/ml). This was also verified for measurements at other ammonium sulfate concentrations (Table 2). For all of the following solubility measurements, the initial concentrations range from 10 to 20 mg/ml above the solubility value to avoid dependence of the solubility values on initial protein concentration.

Table 2.

Dependence of solubility values on initial protein concentration for RNase Sa

| [A.S.] (M) | Solubility (mg/ml)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial [protein] (mg/ml) | ||

| 1.45 | 5 | 4.1 |

| 20 | 4.2 | |

| 1.6 | 5 | 2.3 |

| 20 | 2.4 | |

| 1.75 | 5 | 1.2 |

| 20 | 1.3 |

Measured in 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.25 at 25°C. The error is ±10%.

Salting-out solubility curve for RNase Sa

Solubility curves as a function of ammonium sulfate concentration were obtained for each variant. Solubility curves as a function of ionic strength were reported by Green46. Initially, as the ionic strength increases, protein solubility increases. This is generally called the salting-in region. Then, the solubility reaches a maximum, and protein solubility decreases as the ionic strength increases (salting-out region). In the salting-out region, the precipitation is reversible, and the protein structure is not expected to be affected47.

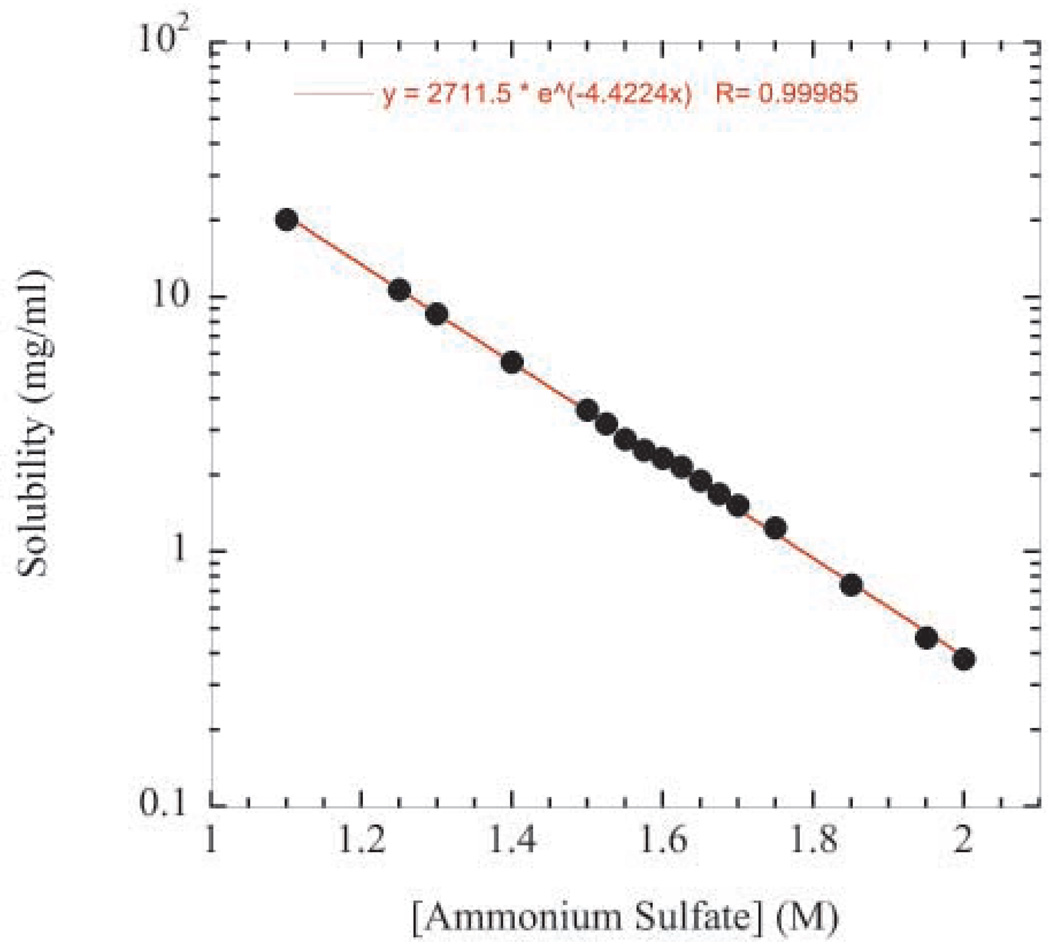

A typical salting-out solubility curve for RNase Sa from 1.1 to 2.0 M ammonium sulfate is shown in Figure 3. As expected for protein salting-out behavior48, the logarithm of solubility decreases linearly with increasing ammonium sulfate concentration. This suggests that our experimental approach and the behavior of the system are reliable. The RNase Sa solubility values range from ~20 mg/ml at 1.1 M ammonium sulfate to ~0.4 mg/ml at 2.0 M ammonium sulfate. The data also suggest that the precipitated protein solution comes to equilibrium quickly. For example, the protein samples with ammonium sulfate concentrations of 1.5 M and greater were allowed to equilibrate for 1 day before determining the solubility values while the samples with ammonium sulfate concentrations below 1.4 M were only allowed to equilibrate for 1 minute. However, both sets of solubility values fall on the same line suggesting that all samples have come to equilibrium within one minute. Similarly, Feher and Kam49 reported that amorphous lysozyme solutions generated by salting-out at high salt concentration also came to equilibrium within one minute.

Figure 3.

RNase Sa solubility as a function of ammonium sulfate concentration in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 4.25.

Amino acid solubility scale at low negative net charge

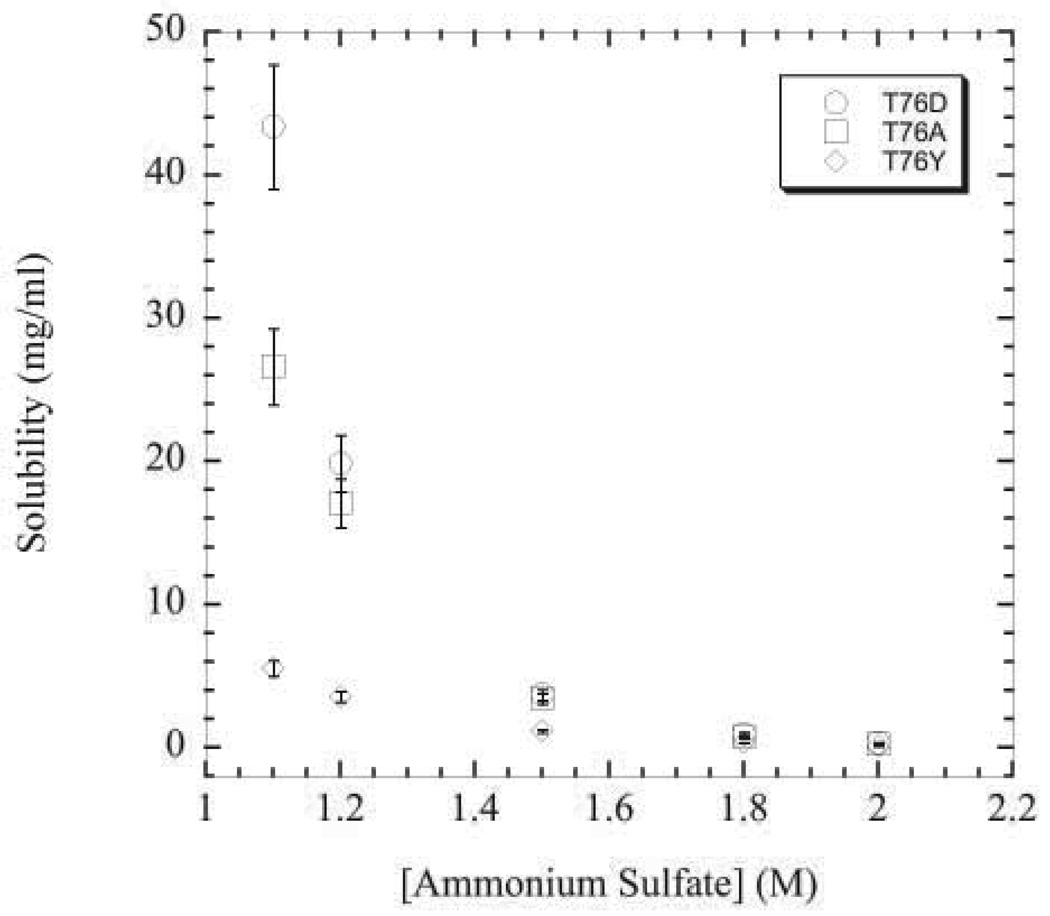

Solubility curves for twenty RNase Sa variants at position 76 were measured at pH 4.25. At this pH, the protein bears a slight negative net charge (about −1) considering that the experimentally determined pI is 3.5 for RNase Sa50. Typical solubility curves for the aspartic acid, alanine, and tyrosine variants are shown in Figure 4. The differences between the variants is magnified as the ammonium sulfate concentration decreases from 2.0 to 1.1 M. Hence, solubility values at 1.1 M ammonium sulfate were used to compare the contribution of each amino acid to protein solubility (Table 3). To gauge the favorable or unfavorable contribution of each amino acid, the solubility value of the alanine variant is considered as the reference. Those variants with solubility values higher than the alanine variant contribute favorably to protein solubility, while variants with lower solubility values contribute unfavorably to protein solubility under the given conditions.

Figure 4.

Solubility curves as a function of ammonium sulfate concentration at pH 4.25 for the aspartic acid (circles), alanine (squares), and tyrosine (diamonds) variants.

Table 3.

RNase Sa solubility values near pI (pH 4.25) in 1.1 M ammonium sulfate at 25°C

| Amino acid at position 76 | Solubility (mg/ml)a |

|---|---|

| Asp | 43 |

| Arg | 42 |

| Glu | 42 |

| Ser | 39 |

| Lys | 31 |

| Gly | 27 |

| Ala | 27 |

| His | 24 |

| Asn | 21 |

| Thr | 20 |

| Gln | 20 |

| Pro | 15 |

| Cys | 12 |

| Met | 11 |

| Val | 10 |

| Leu | 9.3 |

| Ile | 8.2 |

| Tyr | 5.6 |

| Phe | 4.4 |

| Trp | 3.6 |

The error in these measurements is ± 10%.

The results in Table 3 suggest that aspartic acid contributes most favorably to protein solubility while tryptophan contributes the most unfavorably. It was interesting to see dramatic differences in solubility at 1.1 M ammonium sulfate for variants of RNase Sa differing only at position 76. In moderate ammonium sulfate concentrations at low negative net charge (pH 4.25), the following is observed: First, the charged amino acids all display favorable contributions to protein solubility relative to alanine. Second, of the non-ionizable, polar amino acids (serine, threonine, asparagine, and glutamine), only serine contributes favorably to protein solubility. Finally, for the aliphatic side chains, solubility decreases with increasing number of carbon atoms. This is expected and agrees with the work of Nandi and Robinson51 who reported that the solubility at a given salt concentration of a blocked amino acid decreased as the number of side chain carbon groups increased.

Surprisingly, hydrophilic amino acids such as threonine, asparagine, and glutamine contributed unfavorably to protein solubility compared to alanine (Table 3). In the case of asparagine and glutamine, these data suggest that amide groups contribute unfavorably to protein solubility in ammonium sulfate. This is in agreement with the results of Schrier and Schrier52 who measured salting-out constants for methylene, methyl, and amide groups in various salts. The salting-out constants for the methylene and methyl groups were positive as expected. However, in sodium sulfate the salting-out constant for an amide group was also positive, while it was negative in all other salts tested. On the other hand, it was interesting that even in other salts, the amide group salting-out constant only slightly outweighed the salting-out constant of two methylene groups as would be applicable in the case of glutamine. This suggests that, even though the unfavorable contribution of asparagine and glutamine observed here might be an artifact due to the use of ammonium sulfate as the precipitating agent, asparagine and glutamine would only be slightly favorable for solubility compared to alanine in other types of ionic solutions. In other words, there are hydrophilic residues other than threonine, asparagine, or glutamine that contribute much more favorably to protein solubility (Table 3).

Contribution of several polar amino acids to solubility at high negative net charge

The solubilities of the variants with hydrophilic amino acids ranged from 20 mg/ml for T76Q to 43 mg/ml for T76D at low net charge (Table 3). To determine if this range depends on net charge, the solubility values were also determined at pH 7.0 where the net charge of the protein is about −5 (compared to a net charge of about −1 at pH 4.25). Again, solubility values for the variants were compared at 1.1 M ammonium sulfate. Table 4 compares solubility values at pH 4.25 and pH 7.0. As expected due to higher net charge, solubility values at pH 7 were in general higher than those at pH 4.25. However, it was surprising that the solubility of some variants increased dramatically more than others. For example, the solubility of the aspartic acid and serine variants increased over three-fold, whereas the arginine and lysine variants only increased 1.2-fold and 2-fold, respectively (Table 4). Furthermore, lysine and arginine were found to contribute unfavorably to protein solubility under these conditions compared to alanine.

Table 4.

Solubility values for low negative net charge (pH 4.25) and high negative net charge (pH 7.0) in 50 mM buffer and 1.1 M ammonium sulfate at 25°C

| Amino acid at position 76 | Solubility (mg/ml) |

Znet (pH 7.0)c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH 4.25a | pH 7.0b | ||

| Asp | 43 | 160 | −6 |

| Arg | 42 | 50 | −4 |

| Ser | 39 | 130 | −5 |

| Lys | 31 | 60 | −4 |

| Ala | 27 | 92 | −5 |

| Thr | 20 | 41 | −5 |

50 mM sodium acetate buffer

50 mM Mops buffer

Calculated using native state pK values reported in Laurents et al.72

Why do lysine and arginine contribute favorably at low net charge and unfavorably at high net negative charge? One could argue that lysine and arginine appear to contribute unfavorably at pH 7.0 due to the lower net charge (Znet) on these variants compared to the aspartic acid and alanine variants (see Table 4). This argument will be addressed in the next section. We think that lysine and arginine do contribute unfavorably at pH 7.0, and that the contribution involves a balance between the charge on a particular residue, the net charge, and the water-binding ability of the amino acid. The hydration of amino and guanidino groups is poor (see Collins53 and references therein). In fact, the guanidinium cation has been found to possibly be the most weakly hydrated cation ever observed54; 55. Furthermore, the rest of the lysine and arginine side chains are hydrophobic methylene groups. Therefore, considering hydration, it makes sense that lysine and arginine should contribute unfavorably to protein solubility. However, it seems that any kind of charge on a residue at low net charge reduces self-association of the protein molecules. Therefore, the charge on the amino and guanidino groups probably results in a favorable contribution for lysine and arginine, respectively, at pH 4.25. The favorable contribution of the positive charge of lysine at low net charge can be seen considering the solubility value of the lysine variant is ~20 mg/ml higher than that of the methionine variant at pH 4.25 (Table 3). On the other hand, when the net charge of the protein is high, the favorable contribution of the charge on a particular residue may become masked by the higher global net charge. The poor hydration then becomes more important resulting in the unfavorable contribution of lysine and arginine to protein solubility at pH 7.0.

The results at high negative net charge also show that the range of solubility values between the variants with hydrophilic amino acids increases at higher net charge. For example, the difference between threonine and aspartic acid becomes more pronounced as the net charge on the protein increases. At low net charge, the difference in contribution between threonine and aspartic acid is about 23 mg/ml (Table 3). At high negative net charge, this difference increases to about 120 mg/ml (Table 4). The serine variant solubility value also increased significantly relative to threonine. Given the similar solubility values for the asparagine, glutamine, and threonine variants at pH 4.25, aspartic acid and serine are expected to have much higher solubility values (i.e. >100 mg/ml) than asparagine and glutamine at high net charge as well.

Contribution of the aspartic acid, alanine, and lysine variants at high positive net charge

To investigate the balance between contributing factors of residue charge, net charge, and hydration at high positive net charge, we analyzed solubility data in a variant of RNase Sa called 3K43. Compared to RNase Sa (pI ~3.5), the pI is ~6.5 in the 3K variant43. Hence, the 3K variant allows analysis of solubility data at higher positive net charge than in the wild-type protein. The data at high positive net charge for the aspartic acid, lysine, and alanine variants at position 76 are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of the contribution of aspartic acid, alanine, and lysine to solubility at high positive net charge in the 3K Sa variant in 1.1 M ammonium sulfate at 25°C

From these data, the following is observed: The solubility of the alanine variant does not change in going from pH 4.25 to pH 3 despite an increase in net charge from about 3 to about 6 (Table 5). This is probably due to the counterbalance between protonation of the surface carboxyl groups of the protein, which would decrease solubility, and the increase in net charge, which would increase solubility. Also, in agreement with hydration data from Kuntz56 which showed that a protonated aspartic acid binds three times less water than that of the ionized form, we observe a dramatic decrease in the solubility of the T76D(3K) variant under conditions (pH 3) where the side chain is expected to be protonated compared to the solubility value for the T76D(3K) variant at pH 4.25 where the side chain is expected to be mostly ionized (52 vs. 180 mg/ml, respectively). Surprisingly, this dramatic decrease is observed despite a significant increase in net charge of the variant between pH 4.25 and pH 3 (Table 5). Even so, the contribution of the protonated aspartic acid is significantly more favorable than that of lysine (Table 5). Also, the contribution of lysine remains favorable compared to alanine even at a net charge of about 6, but the magnitude of the favorable contribution decreases as net charge increases. For example, the lysine variant is about 17 mg/ml more soluble than the alanine variant at pH 4.25, but only 6 mg/ml more soluble than the alanine variant at pH 3 where the net charge on the protein is higher (Table 5). These data at pH 4.25 and pH 3 seem to support the hypothesis about the relationship between residue charge, net charge, and hydration mentioned above (i.e. the favorable contribution of the positive charge on the lysine gradually becomes overshadowed by the overall net charge, and the poor hydration of the lysine becomes more important). In contrast to the data at high negative net charge showing that lysine makes an unfavorable contribution to solubility, the contribution of lysine remains favorable compared to alanine even at a positive net charge of about 6 (Table 5). This suggests that the positive charge on lysine provides a stronger favorable contribution to solubility when there is an excess of positive charge on the protein compared to when there is an excess of negative charge. Also, one could argue that lysine and arginine contribute unfavorably at high negative net charge because the net charge of these variants is lower than the alanine and aspartic acid variants (Table 4). However, the T76D(3K) variant is still dramatically more soluble than the T76K(3K) variant at pH 4.25 despite the fact that the lysine variant has a higher net charge than the aspartic acid variant (Table 5). The data in Table 5 lend further support to the superior contribution of acidic residues to protein solubility compared to the contribution of lysine and arginine residues. These data also demonstrate the complexity of the amino acid contribution to protein solubility with most of the complexity being due to contributions of the ionizable amino acids. The contributions of the ionizable amino acids can vary widely depending on the net charge of the protein.

Proteins from halophilic organisms show an increased amount of acidic residues accompanied by a decreased amount of lysine residues

Halophilic organisms are capable of living in environments containing 2.5–5.2 M NaCl57. Studies of the properties of proteins from these organisms that allow them to adapt to these conditions should prove useful for the engineering of proteins to function in other dehydrating conditions (i.e. organic solvents) that are used in industrial processes57. The main finding of such studies are that the surfaces of proteins from halophiles contain an excess of acidic residues presumably due to their superior water-binding abilities56 which would help prevent poor protein solubility in such highly dehydrating conditions58–60. Other studies have also observed a concomitant reduction in lysine content in proteins from halophiles61; 62. Our results here show directly that acidic residues are far better than other residues for protein solubility in high salt concentrations, especially at high negative net charge (Table 4), while lysine is unfavorable for protein solubility under these conditions.

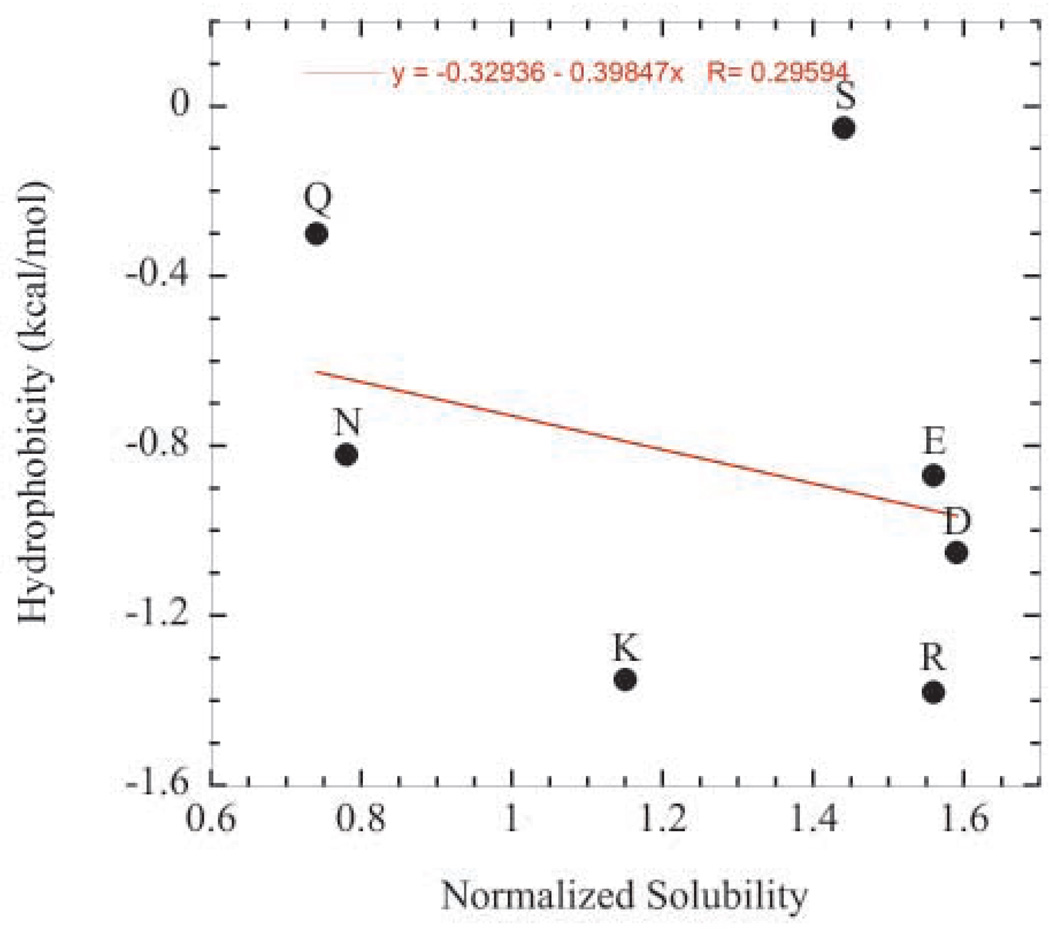

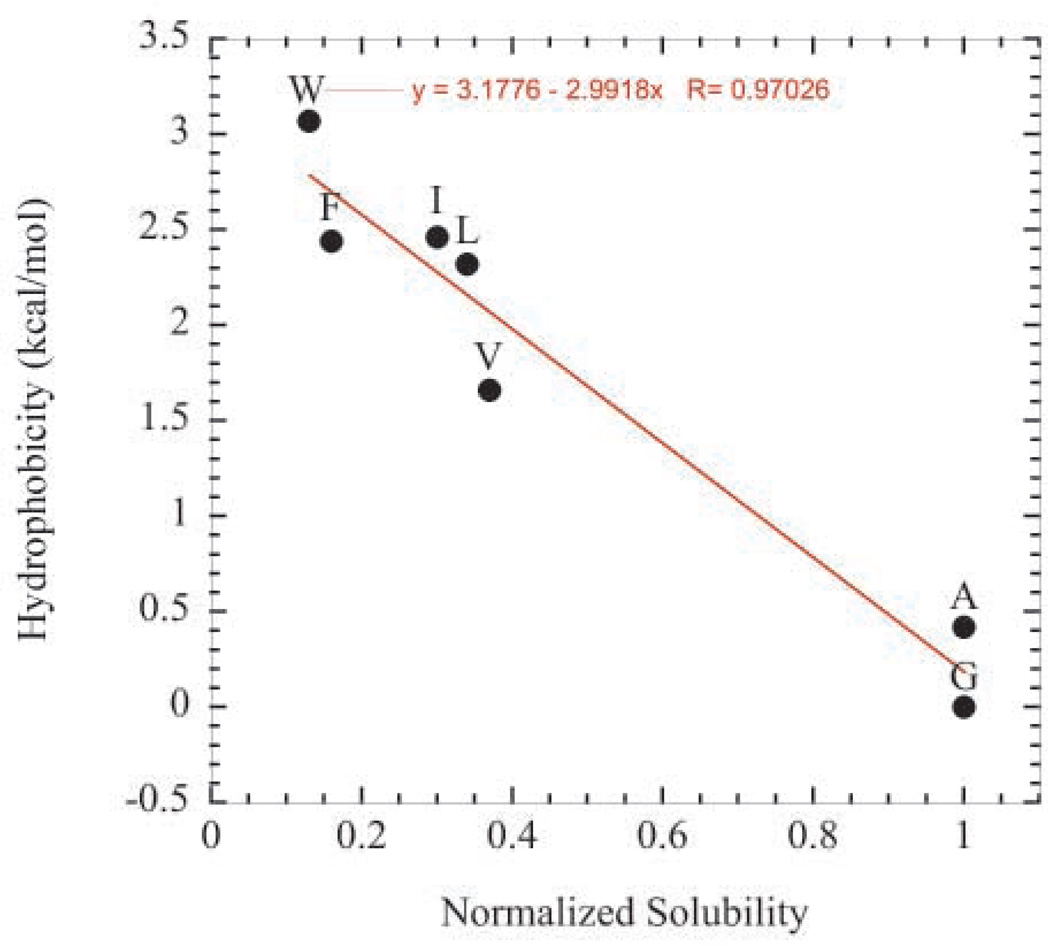

Correlation between amino acid contribution to protein solubility in ammonium sulfate and amino acid hydrophobicity

Unexpectedly, hydrophobicity did not correlate well with the contribution to solubility for several polar amino acids. For example, Figure 5a shows hydrophobicity values as reported by Fauchere and Pliska63 plotted against solubility values of the polar variants at pH 4.25. The solubility values were normalized to the solubility value of the glycine variant. As seen in the plot, the correlation is poor. On the other hand, hydrophobicity and solubility were found to correlate very well for the hydrophobic variants (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Hydrophobicity values as reported by Fauchere and Pliska63 plotted against normalized pH 4.25 solubility values. Solubility values were normalized to the solubility value of the glycine variant. (a) Correlation for the hydrophilic variants. (b) Correlation for hydrophobic variants.

Amino acid contribution to protein solubility in aqueous buffer alone

These results are applicable to increasing protein solubility in ammonium sulfate for enhancement of protein crystallization, but how would these results in ammonium sulfate compare to results in simple buffer solutions alone (i.e. for protein pharmaceutical and general biochemical characterization applications)? For example, would hydrophilic amino acids such as glutamine and arginine still contribute unfavorably in buffer alone? We note that the unfavorable contributions of these amino acids are probably exaggerated in ammonium sulfate, but there is evidence in the literature that seems to suggest that these residues would not contribute favorably in buffer alone either. For example, Davidson and Sauer64 constructed folded proteins that mainly contained random combinations only glutamine, leucine, and arginine. The three QLR proteins they characterized contained roughly 45% glutamine, 45% leucine, and 10% arginine. Despite containing essentially 55% hydrophilic residues, these folded QLR proteins were not soluble in aqueous buffers and had to have some guanidine hydrochloride present to be soluble. In contrast, Doi et. al65 constructed random sequence proteins consisting of alanine, glycine, valine, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid residues. The eight proteins they characterized contained an average of 17% valine and 29% alanine for an average total of about 46% hydrophobic residues as opposed to an average of only 23% acidic residues (i.e. aspartic acid and glutamic acid combined). Despite having a much higher percentage of hydrophobic residues than acidic residues, these VADEG proteins possessed “remarkably high solubility65”. Furthermore, a double mutant (N48E, N130D) vastly increased the solubility of S1 dihydrofolate reductase18. The results from these three studies suggest that acidic residues contribute more favorably to protein solubility than other polar amino acids such as asparagine, glutamine and arginine and therefore, based on our results, lysine and threonine as well – even in aqueous buffers alone.

Results for position 76 apply elsewhere in RNase Sa

Two other single mutants (Q32D and Q77D) were made in RNase Sa to determine if significant increases in solubility could be achieved by substituting glutamine for aspartic acid. These mutations were modeled using Swiss-PDBViewer66 and the percent burial of the carboxyl oxygens were calculated using pfis37 (Table 7). Substitution of these glutamines with glutamic acid would have allowed the carboxyl oxygens to be more exposed to solvent. Nevertheless, significant increases in solubility were observed in these two variants (Table 7). The Q32D mutation resulted in an increase of about 20 mg/ml and the Q77D mutation resulted in an increase of about 14 mg/ml. These values were obtained using the same conditions used in Table 3. The higher increase in the Q32D variant makes sense considering that the carboxyl oxygens are predicted to be more solvent exposed than those in the Q77D variant on average (64% and 70% buried, respectively). Since glutamine, asparagine, and threonine residues contribute similarly to protein solubility (Table 3), the results for the Q32D and Q77D variants suggest that mutating solvent exposed asparagines, glutamines, and threonines to acidic residues should be a generally applicable strategy to increase protein solubility.

Strategy for increasing protein solubility in the absence of structural information

Which residues should be targeted for replacement in cases where protein structure is not known? Given the results in this paper, asparagine, glutamine, and threonine residues would be good targets for two reasons. First, these residues don’t appear to contribute significantly favorably to protein solubility in ammonium sulfate solutions or even in buffer alone18; 64. Second, these polar residues are, in general, more likely to be solvent exposed than traditionally targeted hydrophobic residues. For example, Lesser and Rose67 analyzed structures of sixty-one proteins to determine how much area each residue buries upon folding compared to a Gly-X-Gly standard state. According to their analysis, traditionally targeted hydrophobic residues have, on average, 14% of their surface exposed in folded proteins. On the other hand, the polar residues that we recommend targeting (asparagine, glutamine, and threonine) have, on average, 39% of their surface exposed in folded proteins. Therefore, they are almost three-fold more exposed than traditionally targeted hydrophobic residues. Furthermore, only one out of twenty traditionally targeted hydrophobic residues in RNase Sa is more than 50% exposed, whereas eleven out of twenty of the polar residues recommended for targeting are more than 50% exposed. Hence, if the structure of RNase Sa were not known, one would be ten times more likely to be successful at targeting a surface exposed asparagine, glutamine, or threonine that targeting hydrophobic residues such as valine, leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan. Therefore, in cases where the protein structure is not known, replacement of asparagine, glutamine, or threonine residues with acidic residues or serine should yield significant increases in protein solubility.

Conclusions

Aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and serine appear to contribute dramatically more favorably to protein solubility than the other amino acids, especially at high net charge. We also observe the following: First, the favorable contribution to solubility of lysine and arginine is diminished as net charge of the protein increases and even becomes unfavorable at high negative net charge. Second, protonated acidic residues contribute much less favorably than ionized acidic residues, but still seem to contribute more favorably than any other residue for solubility. Third, we observed that the difference in contributions between aspartic acid (as well as glutamic acid and serine) and the other hydrophilic amino acids gets larger as the net charge of the protein increases (Table 4). Lastly, the contribution of polar amino acids to protein solubility appears to be mainly determined by their water-binding ability (i.e. hydration) rather than their hydrophobicity. For example, the amino and guanidino groups of lysine and arginine residues bind water less strongly than water binds itself (see Collins53 and references therein). Accordingly, we found them to have only a small favorable or unfavorable contribution to protein solubility at high positive or high negative net charge, respectively despite the fact that they are highly hydrophilic residues63 (Table 6). On the other hand, the results of Kuntz56 and Cacace et al.68 suggest that the carboxyl groups of the acidic residues bind water much better than the side chain groups on other amino acids (see Collins53 as well). Accordingly, we observe that they contribute most favorably to protein solubility. Serine appears to be the only other residue that contributes highly favorably to solubility. Our strategy will hopefully lead to more successful attempts at increasing protein solubility for applications in protein crystallography, the protein pharmaceutical industry, and general biochemical characterization.

Table 6.

Characteristics and solubility values for the Q32D and Q77D RNase Sa variants

| Residue | Atom | Burial (%)a | Solubility (mg/ml)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gln32 | OE1 | 16 | 20 |

| NE2 | 43 | ||

| Asp32 | OD1 | 32 | 40 |

| OD2 | 95 | ||

| Gln77 | OE1 | 48 | 20 |

| NE2 | 26 | ||

| Asp77 | OD1 | 80 | 34 |

| OD2 | 59 |

Values calculated using pfis37

Values at 1.1 M ammonium sulfate in 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.25 at 25°C

Materials and Methods

Preparation of mutant plasmids and proteins

Primers were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies at www.idtdna.com. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from Stratagene. Mini-preps of the mutant plasmids were performed using the QIAprep® Spin Miniprep Kit from Qiagen. Sequencing of the mutant plasmids was done at the Gene Technologies Laboratory, Department of Biology, Texas A&M University. All proteins were expressed and purified as described previously50.

Thermal denaturation experiments

The following buffers at 30 mM concentrations were used: pH 4.25, acetate and pH 7.0, Mops. Thermal denaturation experiments were done using an AVIV Circular Dichroism Spectrometer Model 62DS as previously described37; 69. The data were analyzed using KaleidaGraph version 3.6.4 (Synergy Software). The analysis of thermal denaturation curves has been previously described70.

Solubility measurements

All measurements were performed at room temperature (25°C). Three solutions were prepared: 50 mM buffer, 3.0 M ammonium sulfate in 50 mM buffer, and a protein stock solution in 50 mM buffer (see figures and tables for specific buffers used). These three solutions were then mixed together in a 0.2 ml PCR tube for a final sample volume of 15 µl with the desired ammonium sulfate and protein concentrations. For example, to obtain a solubility value for RNase Sa at 1.1 M ammonium sulfate, given a protein stock of 100 mg/ml, one would mix 3.5 µl buffer, 5.5 µl 3.0 M ammonium sulfate, and 6 µl 100 mg/ml protein stock. This would give an initial protein concentration of 40 mg/ml, and RNase Sa would typically salt-out leaving ~20 mg/ml concentration of soluble protein in the tube. Initial protein concentrations ranged from 5 to 20 mg/ml above the expected solubility value. The sample was allowed to equilibrate for >1 minute which is adequate for amorphous salting-out processes as shown by Feher and Kam49 and as explained in the results and discussion section (Figure 3). After equilibration, the sample was transferred to 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes and centrifuged for 1 minute at 16000 RCF. The spectrophotometer was blanked with 495 µl of a 1.1 M ammonium sulfate solution. After centrifugation, 5 µl of the sample was added to the 495 µl blanking solution and mixed to generate a 100-fold dilution. For solubility values at ammonium sulfate concentrations >1.5 M, 65 µl samples were used instead of 15 µl samples and 10-fold dilutions were used instead of 100-fold dilutions for the absorbance measurements. The measurements were replicated three times, and the error from these replications was ±10%, which is typical for good solubility data71. In most cases the error was less than 10%.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Katherine Ridinger, Katherine Schmalzer, Ryan Kramer and Joseph Mire for help with protein expression and purification.

This work has been funded by National Institutes of Health Grant T32 GM065088 (to S.T.), grants GM-37039 and GM-52483 from the National Institutes of Health (USA), and grants BE-1060 and BE-1281 from the Robert A. Welch Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ries-Kautt M, Ducruix A. Inferences drawn from physicochemical studies of crystallogenesis and precrystalline state. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:23–59. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76049-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagby S, Tong KI, Ikura M. Optimization of protein solubility and stability for protein nuclear magnetic resonance. Methods Enzymol. 2001;339:20–41. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)39307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank S, Kammerer RA, Hellstern S, Pegoraro S, Stetefeld J, Lustig A, Moroder L, Engel J. Toward a high-resolution structure of phospholamban: design of soluble transmembrane domain mutants. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6825–6831. doi: 10.1021/bi0000972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li H, Cocco MJ, Steitz TA, Engelman DM. Conversion of phospholamban into a soluble pentameric helical bundle. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6636–6645. doi: 10.1021/bi0026573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slovic AM, Summa CM, Lear JD, DeGrado WF. Computational design of a water-soluble analog of phospholamban. Protein Sci. 2003;12:337–348. doi: 10.1110/ps.0226603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slovic AM, Kono H, Lear JD, Saven JG, DeGrado WF. Computational design of water-soluble analogues of the potassium channel KcsA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1828–1833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306417101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitra K, Steitz TA, Engelman DM. Rational design of'water-soluble' bacteriorhodopsin variants. Protein Eng. 2002;15:485–492. doi: 10.1093/protein/15.6.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roosild TP, Choe S. Redesigning an integral membrane K+ channel into a soluble protein. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2005;18:79–84. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzi010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler SB, Poon S, Muff R, Chiti F, Dobson CM, Zurdo J. Rational design of aggregation-resistant bioactive peptides. Re-engineering human calcitonin. 2005 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501215102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricci MS, Brems DN. Common structural stability properties of 4-helical bundle cytokines: possible physiological and pharmaceutical consequences. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:3901–3911. doi: 10.2174/1381612043382611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ricci MS, Pallito MM, Narhi LO, Boone T, Brems DN. Mutational approach to improve physical stability of protein therapeutics susceptible to aggregation. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brouet JC, Clauvel JP, Danon F, Klein M, Seligmann M. Biologic and clinical significance of cryoglobulins. A report of 86 cases. Am J Med. 1974;57:775–788. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickerson RE, Geis I. Hemoglobin: Structure, Function, Evolution, and Pathology. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings; 1983. pp. 125–158. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunn HF, Forget BG. Hemoglobin: Molecular, Genetic and Clinical Aspects. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1986. pp. 381–594. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans P, Wyatt K, Wistow GJ, Bateman OA, Wallace BA, Slingsby C. The P23T Cataract Mutation Causes Loss of Solubility of Folded gammaD-Crystallin. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pande A, Annunziata O, Asherie N, Ogun O, Benedek GB, Pande J. Decrease in Protein Solubility and Cataract Formation Caused by the Pro23 to Thr Mutation in Human gammaD-Crystallin. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2491–2500. doi: 10.1021/bi0479611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosavi LK, Peng ZY. Structure-based substitutions for increased solubility of a designed protein. Protein Eng. 2003;16:739–745. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dale GE, Broger C, Langen H, D'Arcy A, Stuber D. Improving protein solubility through rationally designed amino acid replacements: solubilization of the trimethoprim-resistant type S1 dihydrofolate reductase. Protein Eng. 1994;7:933–939. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malissard M, Berger EG. Improving solubility of catalytic domain of human beta-1,4-galactosyltransferase 1 through rationally designed amino acid replacements. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:4352–4358. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avramopoulou V, Mamalaki A, Tzartos SJ. Soluble, oligomeric, and ligand-binding extracellular domain of the human alpha7 acetylcholine receptor expressed in yeast: replacement of the hydrophobic cysteine loop by the hydrophilic loop of the ACh-binding protein enhances protein solubility. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38287–38293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park JH, Batt CA. Restoration of a defective Lactococcus lactis xylose isomerase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4318–4325. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4318-4325.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das D, Georgiadis MM. A directed approach to improving the solubility of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1936–1941. doi: 10.1110/ps.16301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schein CH. Solubility and secretability. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1993;4:456–461. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(93)90012-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Middaugh C, Volkin D. Protein Solubility. In: Ahern T, Manning MC, editors. Stability of Protein Pharmaceuticals, Pt. A. New York: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tayyab S, Qamar S, Islam M. Protein Solubility: an old issue gaining momentum. Medical Science Research. 1993;21:805–809. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito T, Wagner G. Using codon optimization, chaperone co-expression, and rational mutagenesis for production and NMR assignments of human eIF2 alpha. J Biomol NMR. 2004;28:357–367. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000015405.62261.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McElroy HE, Sisson GW, Schoettlin WE, Aust RM, Villafranca JE. Studies on engineering crystallizability by mutation of surface residues of human thymidylate synthase. Journal of Crystal Growth. 1992;122:265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkins TM, Hickman AB, Dyda F, Ghirlando R, Davies DR, Craigie R. Catalytic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase: identification of a soluble mutant by systematic replacement of hydrophobic residues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6057–6061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christendat D, Yee A, Dharamsi A, Kluger Y, Savchenko A, Cort JR, Booth V, Mackereth CD, Saridakis V, Ekiel I, Kozlov G, Maxwell KL, Wu N, McIntosh LP, Gehring K, Kennedy MA, Davidson AR, Pai EF, Gerstein M, Edwards AM, Arrowsmith CH. Structural proteomics of an archaeon. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:903–909. doi: 10.1038/82823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yee A, Chang X, Pineda-Lucena A, Wu B, Semesi A, Le B, Ramelot T, Lee GM, Bhattacharyya S, Gutierrez P, Denisov A, Lee CH, Cort JR, Kozlov G, Liao J, Finak G, Chen L, Wishart D, Lee W, McIntosh LP, Gehring K, Kennedy MA, Edwards AM, Arrowsmith CH. An NMR approach to structural proteomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1825–1830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042684599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yee A, Pardee K, Christendat D, Savchenko A, Edwards AM, Arrowsmith CH. Structural proteomics: toward high-throughput structural biology as a tool in functional genomics. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:183–189. doi: 10.1021/ar010126g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caldwell GW, Ritchie DM, Masucci JA, Hageman W, Yan Z. The new pre-preclinical paradigm: compound optimization in early and late phase drug discovery. Curr Top Med Chem. 2001;1:353–366. doi: 10.2174/1568026013394949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang F, Basinski MB, Beals JM, Briggs SL, Churgay LM, Clawson DK, DiMarchi RD, Furman TC, Hale JE, Hsiung HM, Schoner BE, Smith DP, Zhang XY, Wery JP, Schevitz RW. Crystal structure of the obese protein leptin-E100. Nature. 1997;387:206–209. doi: 10.1038/387206a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkinson DL, Harrison RG. Predicting the solubility of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. Biotechnology (N Y) 1991;9:443–448. doi: 10.1038/nbt0591-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Idicula-Thomas S, Balaji PV. Understanding the relationship between the primary structure of proteins and its propensity to be soluble on overexpression in Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 2005;14:582–592. doi: 10.1110/ps.041009005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hennessy D, Buchanan B, Subramanian D, Wilkosz PA, Rosenberg JM. Statistical methods for the objective design of screening procedures for macromolecular crystallization. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56(Pt 7):817–827. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900004261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hebert EJ, Giletto A, Sevcik J, Urbanikova L, Wilson KS, Dauter Z, Pace CN. Contribution of a conserved asparagine to the conformational stability of ribonucleases Sa, Ba, and T1. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16192–16200. doi: 10.1021/bi9815243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rose GD, Geselowitz AR, Lesser GJ, Lee RH, Zehfus MH. Hydrophobicity of amino acid residues in globular proteins. Science. 1985;229:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.4023714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guruprasad K, Rajkumar S. Beta-and gamma-turns in proteins revisited: a new set of amino acid turn-type dependent positional preferences and potentials. Journal of biosciences. 2000;25:143–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hutchinson EG, Thornton JM. A revised set of potentials for beta-turn formation in proteins. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society. 1994;3:2207–2216. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibbs AC, Bjorndahl TC, Hodges RS, Wishart DS. Probing the structural determinants of type II' beta-turn formation in peptides and proteins. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:1203–1213. doi: 10.1021/ja011005e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baldwin RL. How Hofmeister ion interactions affect protein stability. Biophys J. 1996;71:2056–2063. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79404-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaw KL, Grimsley GR, Yakovlev GI, Makarov AA, Pace CN. The effect of net charge on the solubility, activity, and stability of ribonuclease Sa. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1206–1215. doi: 10.1110/ps.440101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shih Y, Prausnitz J, Blanch H. Some characteristics of protein precipitation by salts. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1992;40:1155–1162. doi: 10.1002/bit.260401004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leavis PC, Rothstein F. The solubility of fibrinogen in dilute salt solutions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1974;161:671–682. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(74)90353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green AA. Studies in the physical chemistry of the proteins. VIII. The solubility of hemoglobin in concentrated salt solutions. A study of the salting-out of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1931;93:495–516. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schein CH. Solubility as a function of protein structure and solvent components. Biotechnology (N Y) 1990;8:308–317. doi: 10.1038/nbt0490-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Setchenow M. Action de l'acide carbonique sur les solutions des sels a acides forts. Etude absortiometrique. Ann Chim Phys. 1892;25:226–270. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feher G, Kam Z. Nucleation and growth of protein crystals: general principles and assays. Methods Enzymol. 1985;114:77–112. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(85)14006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hebert EJ, Grimsley GR, Hartley RW, Horn G, Schell D, Garcia S, Both V, Sevcik J, Pace CN. Purification of ribonucleases Sa, Sa2, and Sa3 after expression in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 1997;11:162–168. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nandi PK, Robinson DR. The effects of salts on the free energies of nonpolar groups in model peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:1308–1315. doi: 10.1021/ja00759a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schrier EE, Schrier EB. The salting-out behavior of amides and its relation to the denaturation of proteins by salts. J Phys Chem. 1967;71:1851–1860. doi: 10.1021/j100865a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collins KD. Charge density-dependent strength of hydration and biological structure. Biophys J. 1997;72:65–76. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78647-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mason PE, Neilson GW, Dempsey CE, Barnes AC, Cruickshank JM. The hydration structure of guanidinium and thiocyanate ions: implications for protein stability in aqueous solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4557–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0735920100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mason PE, Neilson GW, Enderby JE, Saboungi ML, Dempsey CE, MacKerell AD, Jr, Brady JW. The structure of aqueous guanidinium chloride solutions. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11462–11470. doi: 10.1021/ja040034x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuntz ID. Hydration of macromolecules. III. Hydration of polypeptides. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:514–516. doi: 10.1021/ja00731a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamekura M. Diversity of extremely halophilic bacteria. Extremophiles. 1998;2:289–295. doi: 10.1007/s007920050071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dym O, Mevarech M, Sussman JL. Structural features that stabilize halophilic malate dehydrogenase from an archaebacterium. Science. 1995;267:1344–1346. doi: 10.1126/science.267.5202.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frolow F, Harel M, Sussman JL, Mevarech M, Shoham M. Insights into protein adaptation to a saturated salt environment from the crystal structure of a halophilic 2Fe-2S ferredoxin. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:452–458. doi: 10.1038/nsb0596-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fukuchi S, Yoshimune K, Wakayama M, Moriguchi M, Nishikawa K. Unique amino acid composition of proteins in halophilic bacteria. J Mol Biol. 2003;327:347–357. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kennedy SP, Ng WV, Salzberg SL, Hood L, DasSarma S. Understanding the adaptation of Halobacterium species NRC-1 to its extreme environment through computational analysis of its genome sequence. Genome Res. 2001;11:1641–1650. doi: 10.1101/gr.190201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Britton KL, Baker PJ, Fisher M, Ruzheinikov S, Gilmour DJ, Bonete MJ, Ferrer J, Pire C, Esclapez J, Rice DW. Analysis of protein solvent interactions in glucose dehydrogenase from the extreme halophile Haloferax mediterranei. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4846–4851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508854103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fauchere JL, Pliska V. Hydrophobicity parameters of amino-acid side-chains from the partitioning of N-acetyl-amino-acid amides. Eur J Med Chem. 1983;18:369–375. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davidson AR, Sauer RT. Folded proteins occur frequently in libraries of random amino acid sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:2146–2150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Doi N, Kakukawa K, Oishi Y, Yanagawa H. High solubility of random-sequence proteins consisting of five kinds of primitive amino acids. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2005;18:279–284. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lesser GJ, Rose GD. Hydrophobicity of amino acid subgroups in proteins. Proteins. 1990;8:6–13. doi: 10.1002/prot.340080104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cacace MG, Santin M, Sada A. Behaviour of amino acids in gel permeation chromatography. Correlation with the effect of Hofmeister solutes on the conformational stability of macromolecules. Journal of Chromatography. 1990;510:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pace CN, Hebert EJ, Shaw KL, Schell D, Both V, Krajcikova D, Sevcik J, Wilson KS, Dauter Z, Hartley RW, Grimsley GR. Conformational stability and thermodynamics of folding of ribonucleases Sa, Sa2 and Sa3. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:271–286. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pace CN, Scholtz JM. Measuring the conformational stability of a protein. In: Creighton TE, editor. Protein structure: A practical approach. Oxford: IRL Press; 1997. pp. 299–321. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guilloteau J, Ries-Kautt M, Ducruix AF. Variation of lysozyme solubility as a function of temperature in the presence of organic and inorganic salts. Journal of Crystal Growth. 1992;122:223–230. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Laurents DV, Huyghues-Despointes BM, Bruix M, Thurlkill RL, Schell D, Newsom S, Grimsley GR, Shaw KL, Trevino S, Rico M, Briggs JM, Antosiewicz JM, Scholtz JM, Pace CN. Charge-charge interactions are key determinants of the pK values of ionizable groups in ribonuclease Sa (pI=3.5) and a basic variant (pI=10.2) J Mol Biol. 2003;325:1077–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thurlkill RL, Grimsley GR, Scholtz JM, Pace CN. pK values of the ionizable groups of proteins. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1214–1218. doi: 10.1110/ps.051840806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]