Abstract

This review focuses on two phenomena that are initiated during and after exposure to intermittent hypoxia. The two phenomena are referred to as long-term facilitation and progressive augmentation of respiratory motor output. Both phenomena are forms of respiratory plasticity. Long-term facilitation is characterized by a sustained elevation in respiratory activity after exposure to intermittent hypoxia. Progressive augmentation is characterized by a gradual increase in respiratory activity from the initial to the final hypoxic exposure. There is much speculation that long-term facilitation may have a significant role in individuals with sleep apnoea because this disorder is characterized by periods of upper airway collapse accompanied by intermittent hypoxia, one stimulus known to induce long-term facilitation. It has been suggested that activation of long-term facilitation may serve to mitigate apnoea by facilitating ventilation and, more importantly, upper airway muscle activity. We examine the less discussed but equally plausible situation that exposure to intermittent hypoxia might ultimately lead to the promotion of apnoea. There are at least two scenarios in which apnoea might be promoted following exposure to intermittent hypoxia. In both scenarios, long-term facilitation of upper airway muscle activity is initiated but ultimately rendered ineffective because of other physiological conditions. Thus, one of the primary goals of this review is to discuss, with support from basic and clinical studies, whether various forms of respiratory motor neuronal plasticity have a beneficial and/or a detrimental impact on breathing stability in individuals with sleep apnoea.

Introduction

This review focuses on two phenomena that are observed both during and following exposure to intermittent hypoxia (IH). In the context of this review, the literature cited is limited primarily but not exclusively to studies that have employed an IH protocol comprised of at least three episodes of hypoxia that are 5 min in duration or less. The two phenomena are referred to as long-term facilitation (LTF) and progressive augmentation (PA) of respiratory motor output. Both phenomena are forms of respiratory plasticity. The review is designed in part to highlight the mechanisms and factors that impact on the expression of LTF and PA. The reader will find that the review is organized on the basis of the two principal stimuli (i.e. acute and chronic intermittent hypoxia, AIH and CIH) known to induce LTF and PA. Additional subheadings have been added if a significant amount of information exists to warrant this addition. The reader should note that the review of the literature as it relates to LTF is not exhaustive because of space limitations and because many excellent reviews over the past few years have been published on this topic (e.g. Mitchell et al. 2001a; Mitchell & Johnson, 2003). We refer readers to these reviews if additional information is desired.

We have also allocated a significant portion of this review to examining the mystery surrounding the physiological role that LTF and PA of respiratory motor output might have in humans. There is much speculation that LTF may have a significant role in individuals with sleep apnoea because this disorder is characterized by periods of upper airway collapse accompanied by IH (Mahamed & Mitchell, 2007). It has been suggested that activation of LTF may serve to mitigate apnoea by facilitating minute ventilation and, more importantly, upper airway muscle activity (Mahamed & Mitchell, 2007). In this review, we examine the less discussed but equally plausible situation that exposure to IH might ultimately lead to the promotion of apnoea. There are at least two scenarios in which apnoea might be promoted following exposure to IH. In both scenarios, LTF of upper airway muscle activity (LTFua) is initiated but ultimately ineffective because of the presence of other physiological conditions. We discuss whether the presence of hypocapnia, possibly promoted by the manifestation of progressive augmentation, could diminish or eliminate the effectiveness of LTF in combating apnoea. Likewise, we discuss whether inhibition of hypoglossal motor neuronal activity and/or upper airway muscle fatigue ultimately renders LTF of hypoglossal motor neurons ineffective. Thus, one of the primary goals of this review is to discuss, with support from basic and clinical studies, whether various forms of respiratory motor neuronal plasticity have a beneficial and/or a detrimental impact on breathing stability in individuals with sleep apnoea.

Long-term facilitation

Acute intermittent hypoxia

Long-term facilitation is a form of neuronal plasticity characterized by a progressive increase in respiratory output during normoxic periods that separate hypoxic episodes and by a sustained elevation in respiratory activity for up to 90 min after exposure to AIH (e.g. 3–5 min episodes of hypoxia interspersed by normoxic recovery periods; Mitchell & Johnson, 2003). Although LTF can be induced by exposure to AIH (Millhorn et al. 1980a; Powell et al. 1998; Mitchell & Johnson, 2003; Mahamed & Mitchell, 2007), it is also evident after intermittent carotid sinus nerve stimulation (Millhorn et al. 1980a; Hayashi et al. 1993; Mateika & Fregosi, 1997), vagal nerve stimulation (Zhang et al. 2003) and brief episodes of simulated apnoea (Mahamed & Mitchell, 2008).

Ventilatory LTF (vLTF) or inspiratory nerve LTF (i.e. phrenic nerve and inspiratory intercostal nerve activity) has been observed in anaesthetized cats (Fregosi & Mitchell, 1994), rabbits (Sokolowska & Pokorski, 2006) and rats (Hayashi et al. 1993; Bach & Mitchell, 1996; Peng & Prabhakar, 2003). Likewise, vLTF has been observed in unanaesthetized rats (Olson, Jr. et al. 2001), mice (Terada et al. 2008), goats (Turner & Mitchell, 1997), ducks (Mitchell et al. 2001b), dogs (Cao et al. 1992) and humans (Babcock & Badr, 1998; Harris et al. 2006; Wadhwa et al. 2008). Long-term facilitation of genioglossus activity (LTFgg) or hypoglossal nerve activity (LTFhypoglossal) has been observed in rats (Fuller et al. 2001a; Behan et al. 2003; McKay et al. 2004; Fuller, 2005), cats (Mateika & Fregosi, 1997) and humans (Harris et al. 2006; Chowdhuri et al. 2008), while LTF of carotid sensory nerve activity (LTFcsn) has been recorded in rats and mice (Peng et al. 2003, 2006b). The LTFcsn differs in part from LTF of phrenic nerve activity (LTFphrenic) and LTFhypoglossal in that it is induced only following exposure to CIH (e.g. 15 s episodes, 9 episodes h−1, 8 h day−1 for 10 days; Peng et al. 2003). In contrast, LTFphrenic and LTFhypoglossal can be induced in naive rats not previously exposed to hypoxia (Mitchell et al. 2001a).

Age and LTF

Long-term facilitation can be initiated early in life as evinced by the existence of vLTF (Julien et al. 2008), LTFgg (McKay et al. 2004) and LTFphrenic (Berner et al. 2007) in neonatal (i.e. 3–10 days old) rats and mice. Nevertheless, once LTF is evident it begins to decline with age, particularly in male rats. Both LTFphrenic and LTFhypoglossal decrease with age in males, but the decrease is more prominent in hypoglossal versus phrenic nerve activity, leading to a complete absence of LTFhypoglossal in middle-aged male rats (13 months old; Zabka et al. 2001b). In contrast to males, LTFphrenic and LTFhypoglossal is greatest in middle-aged female rats when compared with young and geriatric female rats (Zabka et al. 2001a, 2003). Thus, LTFphrenic and LTFhypoglossal in female rats appears to be strongest at an age when the reproductive system reaches a stable plateau of circulating sex hormones (Zabka et al. 2001a, 2003).

Sex hormones and LTF

Decreased levels of testosterone with age and gonadectomy diminish both LTFphrenic and LTFhypoglossal in male rats (Zabka et al. 2001b, 2005). Conversely, both LTFphrenic and LTFhypoglossal are restored by testosterone replacement in gonadectomized male rats (Zabka et al. 2006). In females, LTF is modulated by the oestrous cycle (Zabka et al. 2001a). The most significant increase in LTF has been observed in middle-aged female rats during dioestrus (Zabka et al. 2001a). Also, the magnitude of both LTFphrenic and LTFhypoglossal is inversely related to the ratio of progesterone to oestrogen (Zabka et al. 2003). In humans, there is little evidence that sex hormones play a role in the manifestation of LTF, primarily because few studies have been completed in the area. Nevertheless, we found that LTF was not altered by 7–10 days of treatment with testosterone in healthy young women (Ahuja et al. 2007). Moreover, the manifestation of LTF was not different in healthy men compared with women studied in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (Wadhwa et al. 2008).

State of arousal and LTF

Mahamed & Mitchell (2007) hypothesized that arousal state may play a role in the manifestation of LTF, because vLTF is easier to elicit and more robust in anaesthetized or decerebrate animals compared with awake animals (Mitchell et al. 2001a). Arousal state might impact on the magnitude of LTF because serotonergic neurons (which are required for the initiation of LTF; see ‘Neuromodulation of LTF’) in the raphe nucleus discharge at significantly reduced rates during sleep compared with wakefulness, especially in the deeper stages of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (Heym et al. 1982; Veasey et al. 1995; Jacobs & Fornal, 1997; Jacobs et al. 2002). Consequently, raphe neuronal discharge (both the frequency and amplitude of discharge) is more likely to exhibit significant increases in response to IH because the resting discharge level is significantly less than maximal. This may not be the case during wakefulness, when resting discharge rates may be closer to maximal. Consequently, the expression of LTF may not be as clearly evident during wakefulness because the neurons responsible for initiating LTF are close to discharging at maximal levels even before exposure to IH. This suggestion is supported by findings of Nakamura and colleagues which showed that LTF is most easily induced during deep NREM sleep and is harder to elicit during light sleep or wakefulness in Lewis male rats (Nakamura et al. 2006). To date, no studies in humans have systematically examined whether differences in arousal state impact on the manifestation of LTF.

Carbon dioxide and LTF

Early on, investigators intuitively recognized that reductions in chemoreceptor feedback, as a consequence of hypocapnia, might restrain the manifestation of LTF. Consequently, the apnoeic threshold was determined, and carbon dioxide elevated and maintained above this threshold during and following exposure to IH to ensure the manifestation of LTF. The potential impact of carbon dioxide levels on LTF is supported by results obtained from unanaesthetized rats during wakefulness, which showed that the full expression of vLTF is prevented if accompanied by hypocapnia (Olson et al. 2001). Chemoreceptor feedback restraint of LTF might also explain the findings of McGuire et al. (2002b), who showed that exposure to episodes of 10 but not 8% hypoxia elicited vLTF in awake rats. Exposure to 8% hypoxia was accompanied by profound decreases in carbon dioxide, which led the authors to postulate that the absence of LTF was probably due to chemoreceptor feedback restraint (McGuire et al. 2002b). The level of carbon dioxide sustained during exposure to IH also impacts on the manifestation of LTF in humans during wakefulness. This suggestion is supported by our and other investigators' findings, which revealed that vLTF and LTFgg are not present when carbon dioxide is maintained at hypocapnic or normocapnic levels (McEvoy et al. 1996; Jordan et al. 2002; Mateika et al. 2004; Morelli et al. 2004; Khodadadeh et al. 2006; Diep et al. 2007) but are evident when carbon dioxide is sustained at levels slightly above resting values (Harris et al. 2006; Wadhwa et al. 2008). Moreover, the expression of LTF during sleep appears to be more consistently evident in the presence of normocapnia versus hypocapnia (Pierchala et al. 2008), although further studies designed to examine this issue systemically during sleep remain to be completed.

Chronic intermittent hypoxia

A number of studies have been completed in rats (Ling et al. 2001; O'Halloran et al. 2002; McGuire et al. 2003, 2004; Peng & Prabhakar, 2003; Zabka et al. 2003; McGuire & Ling, 2005), cats (Rey et al. 2004) and dogs (Katayama et al. 2007) to determine whether LTF is enhanced in response to CIH. The length of exposure to CIH has ranged from 4 days (Rey et al. 2004) to 5 weeks (O'Halloran et al. 2002), with animals exposed to IH for 8–12 h day−1 (Ling et al. 2001; McGuire et al. 2003, 2004; Peng & Prabhakar, 2003; Zabka et al. 2003; Rey et al. 2004; McGuire & Ling, 2005; Katayama et al. 2007). The duration of hypoxic episodes has ranged from 15 s (O'Halloran et al. 2002;Peng & Prabhakar, 2003; Katayama et al. 2007) to 5 min (Ling et al. 2001; McGuire et al. 2003, 2004; Zabka et al. 2003; McGuire & Ling, 2005), and the fractional concentration of inspired oxygen from ∼5 (O'Halloran et al. 2002; Peng & Prabhakar, 2003; Katayama et al. 2007) to 11% (Ling et al. 2001; McGuire et al. 2003, 2004; Zabka et al. 2003; Rey et al. 2004; McGuire & Ling, 2005). Despite these differences, the majority of published studies reported that vLTF (McGuire et al. 2003, 2004; McGuire & Ling, 2005), LTFphrenic (Ling et al. 2001; Peng & Prabhakar, 2003), LTFhypoglossal (Zabka et al. 2003) and LTFua (i.e. sternohyoid muscle; O'Halloran et al. 2002) following AIH was enhanced two- to threefold in animals pretreated with CIH or chronic intermittent asphyxia.

Although a number of studies have reported that treatment with CIH enhances LTF in adult animals, some studies have failed to demonstrate this event. The lack of vLTF (Rey et al. 2004; Katayama et al. 2007) or LTFhypoglossal (Veasey et al. 2004) in these studies is unrelated to the animal model employed (i.e. rats, cats and dogs) and the length of exposure to CIH (i.e. 4 days to 3 weeks). It is possible that LTF was initiated in these studies but that it was absent by the time data were collected (i.e. 12–24 h following exposure to the last bout of IH; Rey et al. 2004; Veasey et al. 2004; Katayama et al. 2007). However, this explanation is not supported by the findings of McGuire et al. (2003), who showed that minute ventilation remained above baseline levels in rats for at least 3 days before returning to baseline following 7 days of exposure to IH.

One other possibility is that CIH might mitigate or abolish LTF depending on pre-existing conditions. This possibility is supported by a single study in adult rats which demonstrated that exposure to hypoxic episodes of short duration for 12 h day−1 over a 3 week period did not result in LTFhypoglossal (Veasey et al. 2004). The absence of LTF was confirmed by demonstrating that baseline measures of hypoglossal nerve activity were identical following CIH and a sham protocol (Veasey et al. 2004). Based on the accumulation of isoprostanes in the dorsal medial medulla, Veasey et al. (2004) suggested that oxidative damage to this area of the medulla occurred as a consequence of exposure to IH, leading to the absence of LTF. The possibility that non-myogenic rather than myogenic mechanisms might ultimately be responsible for the abolition of LTFua under some circumstances is supported by the results of Ray et al. (2007), who reported that fatigability of the sternohyoid muscle was not altered by CIH.

One condition that might impact on the expression of LTF following exposure to CIH is age. The majority of published studies indicate that pretreatment with CIH enhances the expression of LTF in young, middle-aged and geriatric adult rats (Zabka et al. 2003). In contrast, a number of studies have shown that vLTF (Julien et al. 2008), LTFphrenic (Reeves et al. 2006) and LTFcsn (Pawar et al. 2008) was not evident in rats, whose age varied from 2–6 h (Pawar et al. 2008) to 10 days (Julien et al. 2008) and 2 months old (Reeves et al. 2006), following exposure to CIH. However, this latter finding is not universal, since exposure to CIH early in life enhanced the expression of vLTF (McGuire & Ling, 2005) in 1-month-old rats and LTFcsn (Pawar et al. 2008) in 2-month-old rats.

Collectively, the preponderance of evidence in the literature indicates that LTF following an acute exposure to IH is enhanced in adult animals pretreated with CIH. Conversely, CIH may mitigate or abolish LTF in neonates. However, since the findings in adults and neonates are not universal, additional studies are required to determine whether varying preparations, hypoxic exposure protocol and recording approaches might account for some of the reported discrepancies.

The enhancement of LTFphrenic and LTFhypoglossal following CIH is a consequence, at least in part, of a central neural mechanism which is likely to be the same mechanism responsible for LTF of respiratory motor activity following AIH. This suggestion is supported by experimental results which have demonstrated that phrenic nerve activity following stimulation of the carotid sinus nerve, which mimics hypoxic activation of the carotid body chemoreceptors while bypassing chemosensory transduction, is enhanced following exposure to 7 days of IH (Ling et al. 2001). This finding, however, does not preclude the possibility that LTFcsn occurs following CIH (Peng et al. 2003). Indeed, direct recordings of carotid sensory nerve activity have shown that despite the absence of sensory LTF following AIH, chronic exposure leads to a robust enhancement of carotid body activity in rats (Peng et al. 2003), cats (Rey et al. 2004) and mice (Peng et al. 2006b).

As demonstrated in other animals, the magnitude of vLTF might be greater in humans exposed previously to IH. Foster et al. (2005) exposed healthy humans to six 5 min episodes of hypoxia interspersed with 5 min normoxic recovery periods each day for 12 consecutive days. These investigators found that breathing frequency on days 8 and 10 was increased compared with day 1, although minute ventilation and tidal volume were not (Foster et al. 2005). The increase in baseline breathing frequency could be an indicator of LTF. However, the greatest magnitude of the phenomenon was probably not determined, given that measurements were obtained 24 h following each hypoxic exposure. We recently completed a study in which the magnitude of LTF was compared between individuals with mild-to-moderate sleep apnoea and control subjects who were matched for body mass index, race and age (Lee et al. 2008). The results revealed that the magnitude of LTF following AIH was significantly greater in the individuals with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) compared with control subjects. This difference could be the result of prior exposure to IH (i.e. CIH). Nevertheless, given the paucity of data in the human literature to support this contention, further studies are necessary to fully establish the impact of CIH on the magnitude of LTF.

Neuromodulation of LTF

Ventilatory LTF, LTFphrenic and LTFhypoglossal induced by a single exposure to IH (i.e. AIH) or CIH is dependent on serotonin (5-HT), because it is eliminated by 5-HT receptor antagonists such as methysergide (Millhorn et al. 1980b; Bach & Mitchell, 1996; McGuire et al. 2004; Ling, 2008). Ventilatory LTF and LTFphrenic are dependent on the activation of 5-HT2 receptors. Pretreatment of awake and anaesthetized rats with ketanserin (a 5-HT2 receptor antagonist) abolishes vLTF (McGuire et al. 2004) and LTFphrenic (Kinkead et al. 2001) completely following exposure to AIH, and partly eliminates CIH-enhanced vLTF and LTFphrenic (Ling et al. 2001; McGuire et al. 2004). Likewise, initiation of LTFcsn appears to be dependent on serotonin and the activation of 5-HT2 receptors, since LTFcsn was activated by intermittent application of serotonin and abolished by the application of ketanserin (Peng et al. 2006a). Although serotonin is required for initiating LTF, it does not have a role in maintaining LTF (Fuller et al. 2001b). Once serotonin binds to 5-HT2 receptors, it initiates a cascade of cellular events (see Fig. 2 of Mahamed & Mitchell, 2007, for details of cellular events), ultimately leading to the synthesis of new brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is responsible for the maintenance of LTF (Baker-Herman et al. 2004). In addition to serotonin and BDNF, the initiation and maintenance of LTFphrenic and vLTF after exposure to AIH or CIH also requires the activation of glutamatergic NMDA receptors. The LTFphrenic and vLTF induced by exposure to AIH were abolished following administration of the NMDA receptor antagonists MK-801 (McGuire et al. 2005) and 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (McGuire et al. 2008) in anaesthetized (McGuire et al. 2005) and awake rats (McGuire et al. 2008), respectively. Likewise, enhancement of vLTF following CIH was substantially decreased after administration of MK-801 (Ling, 2008).

Phrenic LTF, LTFhypoglossal and LTFcsn are not only initiated by excitatory echanisms but may be subject to inhibitory constraints. Suppression of protein phosphatases via the administration of okadaic acid induces LTFphrenic following exposure to sustained hypoxia, a stimulus that typically does not initiate LTF (Wilkerson et al. 2008). Given this finding, it is possible that suppression of protein phosphatases may occur typically during exposure to IH, and this inhibition might contribute to the manifestation of LTF. Recent findings indicate that the suppression of protein phosphatases via the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which typically accumulate during exposure to IH, may in part be responsible for the manifestation of LTFphrenic and LTFhypoglossal following exposure to AIH (Wilkerson et al. 2008) and for LTFcsn following CIH (Peng & Prabhakar, 2003).

Neuromodulation of LTF in humans is not well understood, since few studies have attempted to tackle this issue. We recently showed that vLTF was reduced in individuals with sleep apnoea that were administered an antioxidant cocktail prior to exposure to AIH (Lee et al. 2008). This finding suggests that the release of ROS may have a role in the induction and maintenance of LTF. However, additional studies are needed to determine the mechanisms responsible for modulating LTF in humans.

Progressive augmentation

Progressive augmentation is characterized by a gradual increase in the magnitude of the hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) from the initial to the final hypoxic episode of an IH protocol (Fig. 1; Powell et al. 1998). The increase in the HVR can be sustained for minutes to hours after exposure to IH (Mateika et al. 2004; Fuller, 2005). Although the carotid bodies probably contribute to PA, given their role in other time-dependent ventilatory responses to hypoxia (Powell et al. 1998), this form of plasticity (i.e. progressive augmentation) probably originates from a variety of sites within the respiratory system, including the phrenic motor neurons, respiratory premotor neurons (i.e. at the level of the medulla) and carotid bodies. The relative contribution from each site to PA in animals and humans has not been well differentiated to date and consequently the reader should be cognizant of this gap in the literature while reading the discussion below. Likewise, PA of upper airway muscle activity might reflect integration of both carotid body and hypoglossal motor neuronal plasticity.

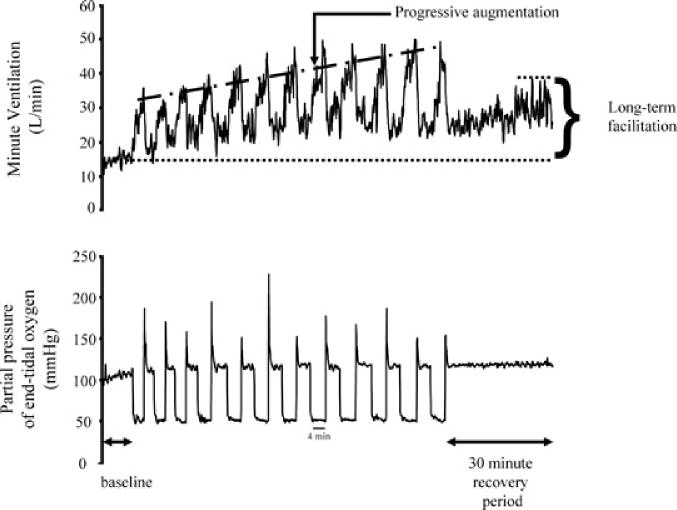

Figure 1. A recording of breath-by-breath minute ventilation values recorded from a human participant before, during and following exposure to 12 episodes of hypoxia.

Each hypoxic episode and subsequent recovery period was 4 min in duration with the exception of the last recovery period, which was 30 min in duration. Note that during exposure to intermittent hypoxia the ventilatory response to hypoxia gradually increased from the initial hypoxic episode to the final hypoxic episode. This phenomenon is referred to as progressive augmentation. Also note that during exposure to intermittent hypoxia minute ventilation gradually increased during the normoxic recovery periods so that it was substantially higher during the final recovery period compared with baseline. This phenomenon is referred to as long-term facilitation.

Independent of the site of plasticity, it should be recognized that measurement of the HVR is dependent on the choice of isocapnic partial pressure of carbon dioxide and the central ventilatory response to carbon dioxide. Although space limitations prevent a detailed explanation of this relationship, the reader is referred to Duffin's excellent review (Duffin, 2007) of this concept. The relationship between the HVR and carbon dioxide is important because, as shown in Fig. 2 (Duffin, 2007), PA of this response may be due to alterations in either the slope (i.e. sensitivity) or the threshold of the response to changes in both oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. The potential impact of altering the threshold or sensitivity on PA is mentioned at this point because altering one or both of these variables (i.e. threshold and sensitivity) impacts on breathing stability, which is the next major topic of discussion (see ‘Respiratory plasticity and sleep apnoea’). Thus, our discussion of PA will focus in part on these two variables as a prelude. Moreover, those factors that potentially impact on PA have been integrated into a discussion on the influence of AIH and CIH on PA.

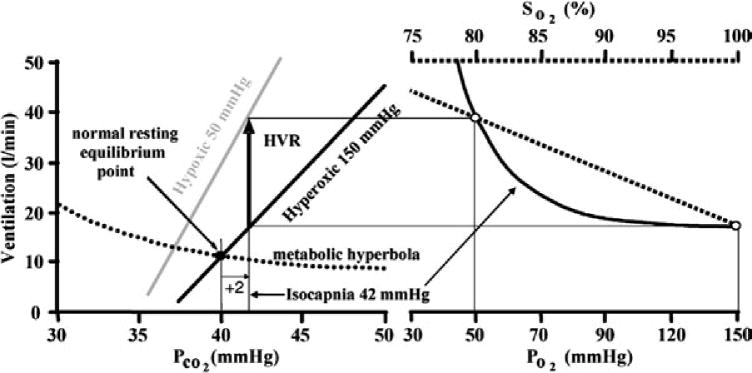

Figure 2. The measurement of the hypoxic ventilatory response is dependent on the level of carbon dioxide that is sustained throughout the intermittent hypoxia protocol.

At a chosen isocapnic partial pressure of carbon dioxide (set to 2 mmHg above resting in this example) the ventilation increase (thick black arrow) from the hyperoxic carbon dioxide response line (assumed to reflect the central chemoreflex response) to the hypoxic carbon dioxide response line (assumed to reflect the sum of central and peripheral chemoreflex responses) is the value measured for the hypoxic ventilatory response. Progressive increases in the hypoxic ventilatory response (progressive augmentation) during exposure to intermittent hypoxia may be the result of changes in either chemoreflex threshold or sensitivity. Note in the figure that increases in the hypoxic ventilatory response may be accomplished by changes in threshold or sensitivity (indicated by changes in slope of the line) but that at a given isocapnic partial pressure of carbon dioxide the mechanisms (change in slope or threshold) responsible for the hypoxic response are indistinguishable from one another. Definitions: PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PO2, partial pressure of oxygen; and SO2, arterial haemoglobin saturation with oxygen. Reproduced with permission from Duffin (2007).

Acute intermittent hypoxia

Progressive augmentation was first observed in inspiratory intercostal nerve activity in anaesthetized cats (Fregosi & Mitchell, 1994) during acute intermittent stimulation of the carotid sinus nerve and soon after in minute ventilation (or its components, tidal volume and breathing frequency) of awake ducks (Mitchell et al. 2001b) and goats (Turner & Mitchell, 1997). More recently, PA of minute ventilation of anaesthetized rabbits (Sokolowska & Pokorski, 2006), phrenic and hypoglossal nerve activity of anaesthetized rats (Fuller, 2005) and carotid sensory activity in an in vitro rat carotid body preparation (Cummings & Wilson, 2005) has been observed. In the study completed in anaesthetized rats it was shown that augmentation of the HVR persisted for 1 h following exposure to IH (Fuller, 2005). Although PA has been observed in a variety of species, there are some studies which have indicated that this phenomenon was absent during AIH. McGuire et al. (2002b) commented that the HVR during the initial and final hypoxic episodes of an acute exposure to IH was not different and consequently they averaged the responses measured during each episode (see Fig. 1 of McGuire et al. 2002b). Likewise, although Olson et al. (2001) did not specifically address the issue of PA in their study, the data presented showed that this phenomenon did not manifest itself in measures of minute ventilation (see Fig. 1 of Olson et al. 2001). In those studies in which PA was observed, it is unknown whether alterations in ventilatory sensitivity or threshold were responsible. Indeed, only one study addressed this issue, recently. Mahamed & Mitchell (2008) reported that the recruitment threshold for phrenic nerve activity was reduced following exposure to IH or intermittent apnoea.

The reasons for the presence of PA during acute exposure to IH in some studies completed in animals compared with others are presently unknown. Moreover, studies designed to systematically identify those factors that impact on PA have not been completed. Nonetheless, factors which impact on the manifestation and magnitude of LTF, such as intensity and duration of the hypoxic episodes and carbon dioxide levels, could account for the variation in the manifestation of PA. However, it is unlikely that hypoxic intensity alone impacts on the degree of PA, since McGuire et al. (2002b) showed that PA was not elicited despite employing three separate IH protocols of varying intensity (12 to 10 to 8%). This result is in contrast to the finding which showed that PA was elicited with a gas mixture containing 14% oxygen (Sokolowska & Pokorski, 2006). More likely, the lack of PA in some studies is linked to the level of carbon dioxide sustained during exposure to IH, as we clearly showed in humans (see two paragraphs below for a review of findings related to humans). In the study of McGuire et al. (2002b), arterial carbon dioxide levels were not constrained, so that increases in hypoxic intensity were associated with gradual reductions in carbon dioxide. Consequently, the most intense hypoxic stimulus was accompanied by a decrease in arterial carbon dioxide of 16 mmHg. Even under the mildest of conditions arterial carbon dioxide decreased by 8 mmHg. Given that the HVR is dependent on the choice of isocapnia, there is little doubt that this will impact on the presentation of PA. In all studies in which PA was evident, carbon dioxide was sustained at or slightly below baseline levels.

Additionally, it is likely that other factors influence the presentation of PA, such as age and sex. Indeed, although beyond the scope of this review, age and sex impact the respiratory motor response to a single bout of hypoxia (Behan & Wenninger, 2008). However, no studies have been designed to systemically examine whether these same factors influence the initiation and magnitude of PA. It is possible that some of these data might be gleaned from published studies which examined the impact of age, gonadectomy and the oestrous cycle on the magnitude of LTF. However, instead of focusing on PA, most studies published to date have reported on the impact of age and sex on the response to the initial hypoxic episode (Zabka et al. 2001a, 2003, 2005). The absence of data related to the expression of PA may be because this phenomenon did not present clearly; although in at least one study PA was evident in the raw data shown from one animal (see Fig. 1 of Zabka et al. 2003). In any event, further studies designed to examine the impact of age and sex on the expression of PA are necessary.

Early studies that were designed to detect PA of the HVR in humans during AIH were not successful. Studies completed in our laboratory and in other laboratories were unable to detect PA of minute ventilation and genioglossus muscle activity in healthy males and females and in individuals suffering from obstructive sleep apnoea (McEvoy et al. 1996; Jordan et al. 2002; Mateika et al. 2004; Khodadadeh et al. 2006; Harris et al. 2006). The lack of a progressive increase in minute ventilation or genioglossus muscle activity in humans was probably because carbon dioxide was sustained at or below baseline levels during exposure to IH (Mateika et al. 2004; Morelli et al. 2004; Khodadadeh et al. 2006). This suggestion is supported by our more recent findings, which revealed a progressive increase in minute ventilation and genioglossus muscle activity in healthy individuals who were exposed to IH when carbon dioxide was sustained slightly above baseline levels (Harris et al. 2006; Wadhwa et al. 2008).

The progressive increase in ventilation observed during exposure to AIH persists following exposure to the stimuli. Using a modified rebreathing method (Duffin & Mahamed, 2003) we showed that augmentation of the HVR was sustained 1–2 h following exposure to IH (Mateika et al. 2004). Moreover, we showed that this augmented response was a consequence of an increase in ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia and not the result of alterations in the threshold following exposure to IH (Mateika et al. 2004). In contrast, other studies reported that the ventilatory response to progressive hypoxia in the presence of sustained isocapnia (Foster et al. 2005) and hypocapnia (Leuenberger et al. 2007) was not enhanced after exposure to AIH. However, enhancement of the HVR may not have been evident in one study because measures were obtained 48 h following exposure to IH (see Fig. 3, day 3 of Foster et al. 2005), as part of a study investigating the impact of 12 days of chronic exposure to IH on the HVR. The lack of an enhanced HVR in the study of Leuenberger et al. (2007) was probably the result of accompanying hypocapnia. In support of this possibility, we found that the enhanced response to hypoxia 1–2 h following exposure to IH was not evident when carbon dioxide levels were below the ventilatory threshold (i.e. hypocapnia), but was clearly enhanced when carbon dioxide was 3–6 mmHg above the threshold (Mateika et al. 2004) in conditions of wakefulness.

Besides the potential impact of carbon dioxide on PA, we have also examined whether sex has a role in the development of PA. We recently showed that progressive augmentation is evident in both men and women and that the degree of augmentation was similar during exposure to IH (Wadhwa et al. 2008). In contrast, we showed that augmentation of the HVR was greater in men compared with women 1 h following exposure to IH (Morelli et al. 2004). This sex difference was related principally to an increase in ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia, since the threshold remained unchanged in both men and women following exposure to AIH (Morelli et al. 2004). Our results may suggest that the variable impact of IH on the HVR in the sexes is more clearly manifested many minutes to hours after exposure to hypoxia. Conversely, the differences may be simply related to the methods employed, since in one study the HVR during exposure to IH was measured at a single level of carbon dioxide (Wadhwa et al. 2008), while in the other study the HVR was measured in the presence of progressively increasing levels of carbon dioxide (Morelli et al. 2004).

Chronic intermittent hypoxia

Progressive augmentation of the HVR has also been examined while animals are exposed to IH over several days (see ‘Long-term facilitation: chronic intermittent hypoxia’ for details of typical CIH protocols). For the sake of clarity, it should be noted that day-to-day measures of PA of the hypoxic response (i.e. gradual increases in the HVR from the first to the last episode) are often not presented in the published literature. Rather, only the day-to-day response to the initial hypoxic episode is reported. Our assumption is that day-to-day enhancement of the response to the initial hypoxic episode reflects day-to-day enhancement of PA.

Some studies have indicated that exposure to CIH enhances the acute response to hypoxia. Ling et al. (2001) exposed rats to CIH and showed that the phrenic nerve response to acute hypoxia or carotid sinus nerve stimulation was enhanced. Likewise, Rey et al. (2004) and Prabhakar's group (Prabhakar et al. 2007; Pawar et al. 2008) reported that exposure to CIH enhanced both the HVR and the carotid body sensory nerve response to hypoxia in cats and rats, respectively. Prabhakar's group observed this phenomenon in both neonatal and adult rats (Prabhakar et al. 2007; Pawar et al. 2008). Interestingly, all studies completed to date reported that the enhanced response was evident during acute exposure to moderate or severe levels of hypoxaemia (e.g. 25–45 mmHg) but was not evident during exposure to mild hypoxaemia (Rey et al. 2004; Prabhakar et al. 2007; Pawar et al. 2008). Collectively, these findings suggest that PA is enhanced following exposure to CIH.

In contrast, there are studies which indicate that PA of the hypoxic hypoglossal and phrenic nerve response is not evident in rats following exposure to CIH. However, most of the evidence is indirect. Veasey et al. (2004) reported that hypoglossal nerve activity in response to various concentrations of serotonin and glutamate was reduced following exposure to CIH in rats (see Figs 1 and 2 of Veasey et al. 2004). Likewise, Ray et al. (2007) reported in a similar animal model that stimulation of the hypoglossal nerve elicited a smaller increase in maximal inspiratory airflow following CIH. One might anticipate that if PA of hypoglossal nerve activity existed following CIH then an increase in maximal inspiratory airflow and an enhanced response to serotonin/glutamate would be evident following exposure. A reduction in sternohyoid muscle activity in response to acute hypoxia following treatment with CIH is a further indication that PA of the hypoxic hypoglossal response is not a given following exposure to CIH (O'Halloran et al. 2002). Peng & Prabhakar (2003) also reported the absence of PA of phrenic nerve activity following CIH, although a raw figure (see Fig. 1 of Peng & Prabhakar, 2003) showed that a progressive increase in the magnitude of phrenic nerve activity occurred during successive hypoxic episodes in one animal following exposure to both AIH and CIH.

There are unequivocal data which indicate that exposure to a small number of episodes of IH of short duration, each day for 1 or 2 weeks, leads to enhancement of the HVR (Forster et al. 1971; Serebrovskaya et al. 1999; Lusina et al. 2006; Koehle et al. 2007) in humans. The length of the hypoxic episodes employed has been 5–7 min in duration separated by 4–10 min of normoxia (Serebrovskaya et al. 1999; Foster et al. 2005; Lusina et al. 2006; Koehle et al. 2007). The number of episodes that subjects were exposed to ranged from three to 12 episodes (Serebrovskaya et al. 1999; Koehle et al. 2007). The HVR following CIH has been reported to increase as much as 103% above baseline (Lusina et al. 2006). Only one study to date has attempted to examine whether changes in the HVR are a consequence of a change in threshold or sensitivity. Koehle et al. (2007) reported that reductions in the ventilatory threshold unaccompanied by alterations in ventilatory sensitivity were evident following exposure to 7 days of IH.

The results obtained from healthy humans exposed to CIH suggest that comparable findings might be observed in individuals with OSA, since exposure to CIH (i.e. weeks, months or years) is a hallmark of this disorder. However, evidence for this adaptation is equivocal. Previous investigations have reported that ventilatory sensitivity is decreased, increased or constant in individuals with OSA (Berthon-Jones & Sullivan, 1987; Tafil-Klawe et al. 1991; Lin, 1994; Verbraecken et al. 1995; Appelberg & Sundstrom, 1997; Narkiewicz et al. 1999; Osanai et al. 1999; Tun et al. 2000; Sin et al. 2000). Dissimilar experimental designs might have contributed in part to the divergent findings. Some studies did not recruit control subjects, while other studies did without matching for a variety of confounding factors that could influence the ventilatory response. Moreover, nearly all of the previously published studies recruited individuals with other known medical conditions that could have contributed to the observed responses. Nevertheless, we examined the ventilatory response to hypoxia in the presence of gradually increasing carbon dioxide levels in young individuals with never-before-treated OSA that were otherwise healthy and individually matched to control subjects for race, height, weight, gender and age (Mateika & Ellythy, 2003). We hypothesized that the ventilatory threshold and sensitivity would be increased in individuals with OSA because of their prior exposure to IH. Alterations of this type would tend to promote breathing instability (see ‘Respiratory plasticity and sleep apnoea: does exposure to intermittent hypoxia promote breathing instability?’ for further discussion). Our results showed that the ventilatory threshold was increased but that no difference in ventilatory sensitivity existed between OSA participants and a control group (Mateika & Ellythy, 2003). Interestingly, however, we found that a significant inverse correlation existed between the ventilatory response to hypoxia/hypercapnia and apnoea severity in individuals with OSA (Mateika & Ellythy, 2003). In other words, the ventilatory response to hypoxia/hypercapnia was enhanced in those individuals with mild apnoea while the response was depressed in those individuals with a more severe form of apnoea. Although based on a small sample, this finding suggests that exposure to CIH might have a differential effect on the ventilatory response to chemical stimuli (i.e. hypercapnia and hypoxia), initially causing an enhancement of the response but ultimately leading to depression of the response. If this is the case, enhancement of ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia might be particularly evident in young individuals who experience mild-to-moderate forms of apnoea. Conversely, the facilitatory impact of CIH may be least evident in individuals who are older and experience severe hypoxaemia throughout a given night. The possibility that the duration and intensity of exposure to IH might impact on the HVR is supported indirectly by studies that have examined the ventilatory response to hypoxia at high altitude. These studies showed that although exposure to continuous hypoxia initially leads to enhancement of the ventilatory response (Sato et al. 1994; Hupperets et al. 2004), eventually a reduction is observed (i.e. hypoxic desensitization; Weil, 1986, 1994; Powell et al. 1998).

Neuromodulatory mechanisms and progressive augmentation

Intermittent serotonin receptor activation that ultimately enhances glutamatergic synaptic currents could be responsible for the initiation of PA of the HVR. This mechanism is similar to that proposed for the initiation of LTF of spinal motoneurons (e.g. phrenic motoneurons) observed during exposure to AIH. However, Fregosi & Mitchell (1994) reported that PA of phrenic and internal intercostal nerve activity persisted throughout exposure to IH following administration of a serotonergic antagonist (i.e. methysergide), even though LTF of phrenic and internal intercostal nerve activity was not evident. Whether or not PA persists in the absence of LTF because the site of initiation differs or because different neuromodulators or receptors are involved in the activation of these two phenomena is not well established. Nonetheless, there is some evidence that serotonin plays a role in the manifestation of both phenomena. Peng et al. (2006a) revealed that intermittent application (i.e. 3 applications) of serotonin on ex vivo carotid bodies resulted in a progressive increase in sensory activity (see Fig. 1C of Peng et al. 2006a). Thus, PA of the hypoxic response during acute exposure to IH might originate in part from enhanced carotid sensory activity controlled partly by the neuromodulator serotonin.

Likewise, enhancement of the HVR and LTF of spinal motoneurons following exposure to CIH may both be impacted by serotonin. Ling et al. (2001) reported that enhancement of the hypoxic phrenic nerve response and LTFphrenic induced by exposure to CIH is abolished when animals are pretreated with the serotonergic antagonist methysergide. Moreover, these authors showed that the enhanced hypoxic phrenic nerve response following exposure to CIH was completely abolished after the application of ketanserin, which is a selective 5-HT2 antagonist (Ling et al. 2001). In contrast, LTF was not abolished completely by ketanserin application (Ling et al. 2001). These authors also revealed that the enhanced hypoxic phrenic nerve response was mediated in part by enhanced central neural integration of input from the carotid sinus nerve (Ling et al. 2001). Collectively, these findings suggest that the neuromodulator serotonin plays a role in augmenting the hypoxic phrenic nerve response and LTFphrenic following exposure to CIH. However, different receptor subtypes may be involved in the activation of PA and LTF. Likewise, the site within the central nervous system where the phenomena are initiated may differ. Phrenic LTF is induced at least in part by the actions of serotonin on spinal motoneurons, while augmentation of the HVR may occur at sites located in the medulla.

It is also possible that augmentation of the HVR is induced by enhanced carotid sensory activity, since this phenomenon occurs in animals pretreated with CIH. However, whether serotonin is a mediator of the increase in the hypoxic carotid sensory nerve response following pretreatment with CIH is presently unknown. On an acute time basis, Peng et al. (2006a) revealed that application of a 5-HT2 antagonist abolished LTFcsn. However, it did not impact on the hypoxic sensory response. Interestingly, Peng and colleagues did show that pretreatment with a superoxide dismutase mimetic abolished both the enhanced hypoxic carotid sensory nerve response (Peng & Prabhakar, 2004) and LTFcsn (Peng & Prabhakar, 2003) normally observed after CIH. Thus, although it is not well established that serotonin plays a role in enhancing the hypoxic carotid sensory nerve response and LTFcsn, ROS are implicated in the expression of both phenomena.

Respiratory plasticity and sleep apnoea

Sleep apnoea is characterized by episodes of breathing cessation accompanied by hypoxaemia and hypercapnia (White, 2005). Given the findings reviewed above, it is possible that IH experienced by individuals with sleep apnoea results in the manifestation of both PA and LTF at various sites within the respiratory system. If this is the case, it is of interest to speculate how these forms of plasticity might interact to promote or mitigate apnoea.

In our discussion below, references to plasticity are made primarily in the context of upper airway muscle and minute ventilation responses to IH. More specifically, we discuss the role of vLTF, as well as the role of PA of the HVR (in the context of changes in the ventilatory threshold and sensitivity) in promoting or mitigating apnoea. Mechanistically, we assume in our discussion that vLTF is due in part to LTFphrenic, but we cannot rule out the possibility that LTF of respiratory premotor neurons or LTFcsn are in part responsible. Likewise, we assume that alterations in the ventilatory threshold and/or sensitivity responsible for PA of the HVR may well be a manifestation of LTFcsn; however, we also recognize that other forms of plasticity (LTFphrenic or medullary respiratory motoneurons) are likely to contribute to alterations in the threshold and sensitivity of the HVR. Lastly, in the discussion below we acknowledge that changes in the ventilatory threshold and sensitivity to both hypoxia and hypercapnia have a role in PA of the HVR (see ‘Progressive augmentation’ for further discussion of this issue).

We present three scenarios that address the potential influence of IH on the severity of apnoea (Fig. 3). In comparing and contrasting the scenarios, we assume that all other variables (e.g. sleep stage, arousal threshold and anthropometric factors) that impact on apnoea severity remain constant across each of the models. The first scenario considers how upper airway muscle LTF, vLTF and the HVR (in the context of changes in the ventilatory threshold and sensitivity) interact in order to mitigate the severity of apnoea. This scenario focuses primarily on the importance of upper airway muscle plasticity in mitigating apnoea and the necessary alterations (or lack thereof) in vLTF and the ventilatory threshold and sensitivity to hypoxia required to ensure the effectiveness of upper airway muscle plasticity in mitigating apnoea (Fig. 3A). The second scenario examines the impact that vLTF and PA of the HVR have on apnoea severity and the manner in which these forms of plasticity might serve to diminish the role that LTFua has in mitigating the severity of apnoea (Fig. 3B). The third scenario considers the ‘perfect storm’ in which upper airway muscle function is diminished and is coupled to alterations in the ventilatory threshold and sensitivity to hypoxia that promote apnoea (Fig. 3C).

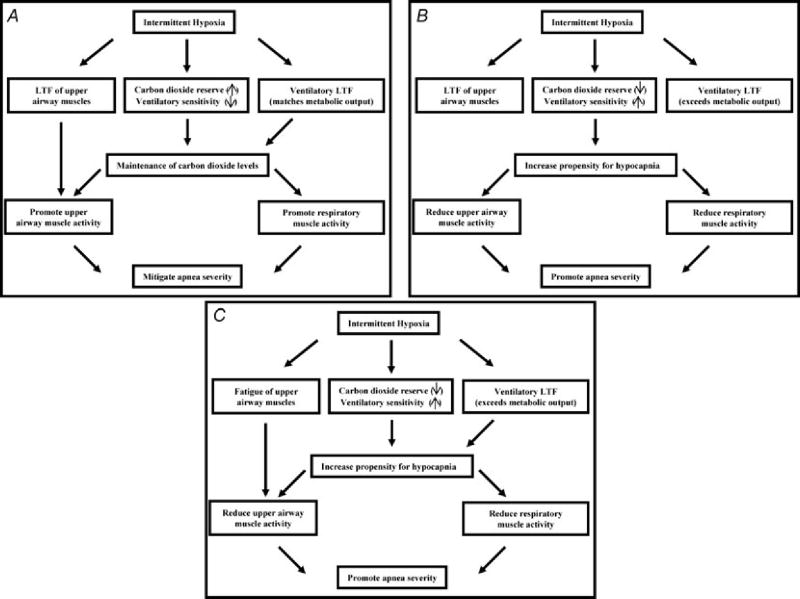

Figure 3. Three scenarios that address the potential influence of intermittent hypoxia on apnea severity.

A, the ideal scenario is presented in which exposure to intermittent hypoxia promotes breathing stability. In this scenario, exposure to intermittent hypoxia leads to long-term facilitation of upper airway muscle activity, promoting the maintenance of upper airway patency. Likewise, carbon dioxide reserve is unaltered or increased while ventilatory sensitivity is unaltered or reduced. These chemoreflex characteristics promote the maintenance of carbon dioxide levels, ensuring that hypocapnia does not develop, which could restrain the manifestation of LTF of upper airway muscle activity. Ultimately, this integrated response promotes breathing and potentially mitigates the severity of apnoea. B, a scenario in which long-term facilitation is induced in upper airway muscles following exposure to intermittent hypoxia but ultimately is ineffective in mitigating apnoea because decreases in carbon dioxide reserve and increases in chemoreflex sensitivity increase the propensity for developing hypocapnia. The induced hypocapnia restrains LTF of upper airway muscle activity and respiratory muscle activity, ultimately resulting in the promotion of apnoea. C, a scenario in which exposure to intermittent hypoxia leads to fatigue of the upper airway muscles and results in a decrease in the carbon dioxide reserve and increase in chemoreflex sensitivity, ultimately resulting in a worse case scenario that results in the promotion of apnoea.

Does exposure to intermittent hypoxia promote breathing stability? An examination of the roles that ventilatory and upper airway muscle plasticity have in mitigating apnoea

Based primarily on animal findings, it has been suggested that exposure to IH across a selected time period (i.e. a single night, days, months or years) could lead to vLTF and LTFua. The promotion of upper airway muscle activity would be of particular importance in individuals with OSA, since it could potentially eliminate or mitigate obstruction of the airway. However, if LTFua is to effectively mitigate apnoea, this requires that vLTF or changes in the ventilatory threshold or sensitivity to hypoxia (i.e. progressive augmentation) do not ultimately induce conditions that render LTFua ineffective in combating apnoea. There is evidence that the manifestation and/or magnitude of LTF might be dependent on carbon dioxide levels (see ‘Long-term facilitation: carbon dioxide and LTF’). Thus, in humans if vLTF is initiated and results in the development of hypocapnia, this might effectively abolish the manifestation of LTFua. Consequently, LTFua may have its greatest influence in the absence of vLTF or in conditions in which vLTF exists but carbon dioxide levels are maintained at or above baseline levels.

Likewise, as outlined below (see ‘Does exposure to intermittent hypoxia promote breathing instability?’ for further details), increases in the ventilatory threshold and sensitivity to hypoxia (i.e. PA of the HVR) could also lead to the induction of hypocapnia, rendering LTFua ineffective. Thus, LTFua would probably be most effective when the threshold and sensitivity of the response to hypoxia remain unchanged or are altered in a manner that promotes the maintenance of normocapnia. Decreases in ventilatory sensitivity and/or decreases in carbon dioxide levels that demarcate the ventilatory threshold relative to resting measures of carbon dioxide (i.e. increases in the carbon dioxide reserve) might lead to the maintenance of carbon dioxide levels (Fig. 4). However, there are few studies which have directly shown that exposure to IH decreases ventilatory sensitivity or the ventilatory threshold relative to the resting equilibrium point in humans. The exact opposite typically occurs when humans are acutely or chronically exposed to IH particularly when it comes to measures of ventilatory sensitivity (see ‘Progressive augmentation: acute and chronic intermittent hypoxia’). However, Katayama et al. (2007) recently reported in dogs that the carbon dioxide reserve (the difference between the carbon dioxide level that demarcates the ventilatory threshold and the resting equilibrium point) increases following 3 weeks of exposure to IH. This scenario coupled with LTFua would probably lead to the promotion of breathing stability.

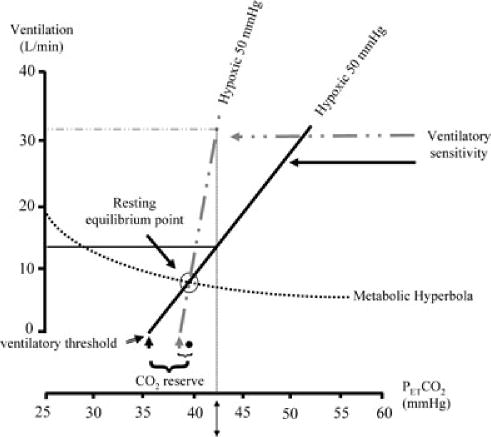

Figure 4. A schematic diagram showing how changes in the ventilatory threshold and sensitivity to hypoxia could lead to disproportionate increases in ventilation and promote the development of hypocapnia.

Note that the change in the ventilatory threshold from the black arrow to the continuous grey arrow significantly reduces the carbon dioxide reserve (i.e. the difference in the carbon dioxide value that demarcates the threshold and the resting equilibrium point (●). If the carbon dioxide reserve is significantly reduced, small reductions in carbon dioxide will result in a carbon dioxide level that is below resting values, leading to reductions in breathing or apnoea. Likewise, a disproportionately high ventilatory sensitivity (dashed grey line) to hypoxia/hypercapnia (in this example, the partial pressure of oxygen is 50 mmHg and the partial pressure of carbon dioxide is 43 mmHg, indicated by ↕) following an apnoea may ultimately result in reductions in carbon dioxide below resting values. Conversely, reductions in ventilatory sensitivity (continuous black line) and the ventilatory threshold (continuous black arrow) relative to the resting equilibrium point will tend to promote maintenance of carbon dioxide levels.

Figure 3A presents the ideal scenario in which exposure to IH ultimately leads to the mitigation of apnoeic events. In this scenario, LTFua is elicited by exposure to IH. Likewise, the exposure to IH results in a reduction in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide that demarcates the ventilatory threshold relative to baseline with no change or a reduction in ventilatory sensitivity. Consequently, the carbon dioxide reserve increases (i.e. the degree to which carbon dioxide must be reduced to induce an apnoea), and the lack of an increase in ventilatory sensitivity ensures that it is unlikely that carbon dioxide would be reduced sufficiently during sleep to induce hypocapnia, thereby ensuring the effectiveness of LTFua. Thus, LTFua coupled with an increase in the carbon dioxide reserve and a decrease (or no change) in ventilatory sensitivity would likely promote breathing stability over a given period of time. Experimental evidence suggests that LTFgg is initiated in humans following exposure to AIH (Harris et al. 2006; Chowdhuri et al. 2008). However, at the present time it is not well established whether LTFua occurs in the absence of vLTF or alterations in the ventilatory threshold or sensitivity to hypoxia/hypercapnia. Likewise, it is not established whether LTFua occurs concomitantly with increases in the carbon dioxide reserve and/or decreases in ventilatory sensitivity.

If LTFua does effectively mitigate apnoea, it might be anticipated that following exposure to IH, on a short-or long-term time basis, a reduction in the number or severity of apnoeic events might be evident. No study incorporating a well-controlled experimental design to address this issue in humans has been published to our knowledge, although we are presently addressing the relationship between IH and apnoea severity. Thus, evidence for the role of LTFua in mitigating apnoea is primarily indirect. Epidemiological studies have reported that the prevalence of sleep apnoea is greater in males compared with females and is greater in the elderly compared with younger individuals (Bixler et al. 2001). Based on these results, it would be anticipated that LTFua would be more prominent in females compared with males and more prominent in younger individuals compared with the elderly. Studies completed in animals appear to support this contention, in that LTF was reduced in elderly male and female rats compared with younger rats (Zabka et al. 2001a,b, 2003). Moreover, LTF was more prominent in middle-aged female rats (Zabka et al. 2001a) compared with male rats (Zabka et al. 2001b), although LTF was more prominent in young males (Zabka et al. 2001b) compared with females (Zabka et al. 2001a). Similar findings have not been established in humans, in part because few studies have examined this issue. One study did report that there was no correlation between LTFgg and age (Chowdhuri et al. 2008). However, the range of ages in the study was small and the overall focus of the study was unrelated to the relationship between age and LTFua, thus further investigations are required (Chowdhuri et al. 2008). Likewise, no differences in the development of vLTF have been observed in young males compared with females during wakefulness (Wadhwa et al. 2008). Nonetheless, additional studies are required to compliment the few studies completed to date.

Does exposure to intermittent hypoxia promote breathing instability? An examination of the roles that ventilatory and upper airway muscle plasticity have in promoting apnoea

If LTFua plays a predominant role in mitigating apnoea and the loss of LTFhypoglossal shown in middle-aged male rats (Zabka et al. 2001b) also occurs in humans, then one might anticipate that the vast majority of middle-aged men would suffer from sleep apnoea. This is not the case, however, since only 5% of middle-aged men develop OSA (Bixler et al. 2001; Behan et al. 2002). Thus, it is unlikely that the loss of LTFua is wholly responsible for the development of OSA in middle-aged men. Consequently, other mechanisms must be responsible (Behan et al. 2002).

Additionally, if one hypothesized that LTF serves to mitigate apnoea then it would be expected on a shorter time scale that the severity of apnoea would diminish throughout a given night, because exposure to IH over the night should theoretically lead to the manifestation of LTFua. However, clinical studies have shown that apnoea number (Fanfulla et al. 1997; Sforza et al. 1998) and duration (Charbonneau et al. 1994; Cala et al. 1996; Sforza et al. 1998) increases throughout the night independent of other factors that might be responsible for this phenomenon. This latter finding suggests that either LTFua is not initiated in individuals with sleep apnoea following exposure to IH or that it is initiated but at best is ineffective in mitigating apnoea. Whether or not LTFua is initiated and manifests itself in humans is likely to be dependent on a variety of factors, which have been reviewed above (see ‘Long-term facilitation: acute and chronic intermittent hypoxia’). Furthermore, whether LTFua once initiated is able to effectively mitigate apnoea is not well established. Thus, the scarce data that exist in the literature suggest that apnoea severity increases and that this increase might occur whether or not LTFua is initiated. Consequently, the initiation of other forms of plasticity that occur concurrently with the commencement of LTFua following exposure to IH might be responsible for the findings which have indicated that sleep apnoea severity increases throughout the night. These other processes might include vLTF and PA of the HVR. Both these phenomena could promote apnoea and breathing instability via the induction of hypocapnia (Fig. 4; Dempsey et al. 2004; Dempsey, 2005). Indeed, Terada et al. (2008) recently showed in mice that the severity of apnoea was not mitigated in the presence of vLTF.

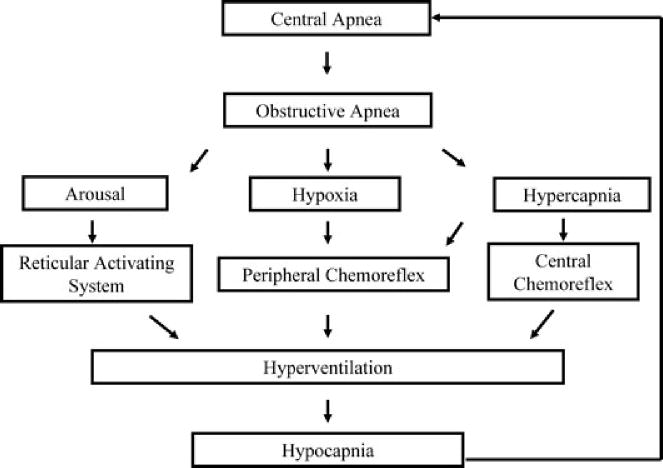

Hypocapnia might occur under normoxic conditions if vLTF results in minute ventilation exceeding metabolic output. The development of hypocapnia could lead to a reduction in the expression of LTFua. Likewise, and potentially more importantly, PA of the HVR induced by exposure to IH could lead to the development of hypocapnia immediately following the termination of an apnoea (Fig. 5). Following an apnoea, the peripheral chemoreflex and possibly the central chemoreflex is activated as a consequence of the hypoxia and hypercapnia developed during the apnoea. Increases in ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia might result in an inappropriate response to these chemical stimuli so that carbon dioxide levels decrease below the ventilatory threshold, resulting in a subsequent central apnoea. Likewise, if the ventilatory threshold is altered so that the carbon dioxide reserve is reduced then this alteration will increase the likelihood of hypocapnia. The induction of a central apnoea as a consequence of the hypocapnia might be followed by occlusion of the airway (Fig. 5), as shown in a variety of studies (Onal et al. 1986; Hudgel et al. 1987; Badr et al. 1995; Badr, 1996). This may occur in part because of a reduction in upper airway muscle activity as a consequence of the induction of hypocapnia (Badr, 1996; Badr et al. 1997). This possibility might ultimately explain the ineffectiveness of LTFua in mitigating apnoea following exposure to IH, since even if the phenomenon exists it may not manifest itself in the presence of severe hypocapnia (Fig. 3B).

Figure 5. A schematic diagram showing how hypocapnia leads to the promotion of apnoea.

Reductions in carbon dioxide lead to disfacilitation of central and peripheral chemoreceptors and ultimately respiratory neurons, resulting in an apnoea of central origin that may be followed by an obstructive event. Apnoea is accompanied by intermittent hypoxia and hypercapnia. In response to hypoxia and hypercapnia, the peripheral and central chemoreceptors are facilitated, resulting in an increase in ventilation. If the ventilatory response to the changes in chemical stimuli is disproportionately high, as would be the case if chemoreflex sensitivity is increased, a significant reduction in carbon dioxide would ensue. The reduction could result in below resting values, particularly if the carbon dioxide reserve is reduced, ultimately resulting in hypocapnia and the development of a subsequent apnoea.

There is a good deal of evidence to support the contention that ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia/hypercapnia is increased in humans in response to exposure to AIH and CIH (Serebrovskaya et al. 1999; Mateika et al. 2004; Khodadadeh et al. 2006; Lusina et al. 2006; Koehle et al. 2007). In contrast, the results regarding changes in ventilatory threshold are more equivocal, with decreases reported in animals after AIH and no alterations reported in humans. Nonetheless, the preponderance of evidence suggests that exposure to IH not only leads to the initiation of LTFua but also to vLTF and PA of the HVR. These latter alterations could potentially promote rather than mitigate apnoea. Thus, if the physiological consequences of vLTF or PA render LTFua ineffective, breathing instability might result.

Upper airway muscle dysfunction and the promotion of breathing instability

It is also important to recognize that exposure to IH and the subsequent initiation of LTF of upper airway motor neurons might not always translate into sustained increases in upper airway muscle activity and force production. It is probable that exposure to mild hypoxia, particularly over an acute period of time, initiates LTFhypoglossal and that this translates to sustained increases in genioglossus muscle activity (Harris et al. 2006) and force production in humans. Chronic exposure to mild hypoxia over a longer period of time might also induce a similar response, although this is not established in humans. However, exposure to severe levels of hypoxia over many hours, days, months or years is likely to impair hypoglossal motor neuronal and/or upper airway muscle function, resulting in the loss of capacity to develop the force necessary to overcome a resistive load applied to the upper airway. Whether the loss of muscle function is myogenic or non-myogenic in nature is not fully established. Studies in rats have shown that exposure to CIH initiated changes in both structure and function of the pharyngeal dilator muscles (geniohyoid and sternohyoid; Bradford et al. 2005). Specifically, CIH led to increased fatigability of pharyngeal dilator muscles (McGuire et al. 2002a; Bradford et al. 2005). In contrast, Ray et al. (2007) reported that fatigability of the sternohyoid muscle was not altered by CIH, indicating that non-myogenic rather than myogenic mechanisms might contribute at least in part to the absence of LTFhypoglossal and reduced muscle function following chronic exposure to severe levels of hypoxia. Independent of the site of impairment, reduced muscle function following long-term exposure to IH might ultimately occur as a consequence of the accumulation of ROS either at the level of the muscle (Bradford et al. 2005) or at the hypoglossal motor nucleus (Veasey et al. 2004). If upper airway dysfunction ensues (i.e. LTFhypoglossal or LTFua is not evident and/or overt upper airway muscle impairment is evident) following exposure to CIH, this could have a significant impact on the promotion of apnoea. This impairment of upper airway muscle function could ultimately overpower any influence that alterations in ventilatory sensitivity or threshold might have on the severity of apnoea. For example, we speculated above (see ‘Progressive augmentation: chronic intermittent hypoxia’) that exposure to severe hypoxia over a prolonged period of time might dampen ventilatory sensitivity, which could mitigate apnoea. However, in the presence of upper airway muscle fatigue, alterations in chemoreflex properties may have little impact. Likewise, the impact of upper airway muscle fatigue could be further pronounced if a simultaneous increase in ventilatory sensitivity and threshold (i.e. a reduction in the carbon dioxide reserve) was initiated by exposure to CIH (Fig. 3C).

Summary and conclusion

We have reviewed published work on two forms of respiratory plasticity, LTF and PA, which are initiated during and following exposure to IH. Moreover, we have reviewed a variety of factors, such as age, sex, arousal state and gas environment, that influence the manifestation of LTF and PA, making them complex phenomena to study. Although plenty of studies examining LTF in animals exist, fewer animal studies have focused on PA. Moreover, further studies are needed to examine these two phenomena in humans and the factors that influence these phenomena. Lastly, studies that begin to examine how various forms of plasticity interact and ultimately impact on breathing stability will bring us one step closer to understanding the impact that exposure to IH has on breathing in individuals with sleep apnoea.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01-HL-085537) and a Veteran Affairs Merit Award.

References

- Ahuja D, Mateika JH, Diamond MP, Badr S. Ventilatory sensitivity to carbon dioxide before and after episodic hypoxia in females treated with testosterone. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:1832–1838. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01178.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelberg J, Sundstrom G. Ventilatory response to CO2 in patients with snoring, obstructive hypopnoea and obstructive apnoea. Clin Physiol. 1997;17:497–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.1997.05353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock MA, Badr MS. Long-term facilitation of ventilation in humans during NREM sleep. Sleep. 1998;21:709–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach KB, Mitchell GS. Hypoxia-induced long-term facilitation of respiratory activity is serotonin dependent. Respir Physiol. 1996;104:251–260. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(96)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr MS. Effect of ventilatory drive on upper airway patency in humans during NREM sleep. Respir Physiol. 1996;103:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(95)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr MS, Kawak A, Skatrud JB, Morrell MJ, Zahn BR, Babcock MA. Effect of induced hypocapnic hypopnea on upper airway patency in humans during NREM sleep. Respir Physiol. 1997;110:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(97)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr MS, Toiber F, Skatrud JB, Dempsey J. Pharyngeal narrowing/occlusion during central sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:1806–1815. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.5.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman TL, Fuller DD, Bavis RW, Zabka AG, Golder FJ, Doperalski NJ, Johnson RA, Watters JJ, Mitchell GS. BDNF is necessary and sufficient for spinal respiratory plasticity following intermittent hypoxia. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:48–55. doi: 10.1038/nn1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behan M, Wenninger JM. Sex steroidal hormones and respiratory control. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.06.006. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behan M, Zabka AG, Mitchell GS. Age and gender effects on serotonin-dependent plasticity in respiratory motor control. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2002;131:65–77. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(02)00038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behan M, Zabka AG, Thomas CF, Mitchell GS. Sex steroid hormones and the neural control of breathing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;136:249–263. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berner J, Shvarev Y, Lagercrantz H, Bilkei-Gorzo A, Hokfelt T, Wickstrom R. Altered respiratory pattern and hypoxic response in transgenic newborn mice lacking the tachykinin–1 gene. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:552–559. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01389.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthon-Jones M, Sullivan CE. Time course of change in ventilatory response to CO2 with long-term CPAP therapy for obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:144–147. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, Ten Have T, Rein J, Vela-Bueno A, Kales A. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in women: effects of gender. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:608–613. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.9911064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford A, McGuire M, O'Halloran KD. Does episodic hypoxia affect upper airway dilator muscle function? Implications for the pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnoea. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;147:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cala SJ, Sliwinski P, Cosio MG, Kimoff RJ. Effect of topical upper airway anesthesia on apnea duration through the night in obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:2618–2626. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.6.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao KY, Zwillich CW, Berthon-Jones M, Sullivan CE. Increased normoxic ventilation induced by repetitive hypoxia in conscious dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:2083–2088. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau M, Marin JM, Olha A, Kimoff RJ, Levy RD, Cosio MG. Changes in obstructive sleep apnea characteristics through the night. Chest. 1994;106:1695–1701. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.6.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhuri S, Pierchala L, Aboubakr SE, Shkoukani M, Badr MS. Long-term facilitation of genioglossus activity is present in normal humans during NREM sleep. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;160:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KJ, Wilson RJ. Time-dependent modulation of carotid body afferent activity during and after intermittent hypoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1571–R1580. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00788.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA. Crossing the apnoeic threshold: causes and consequences. Exp Physiol. 2005;90:13–24. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.028985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Smith CA, Przybylowski T, Chenuel B, Xie A, Nakayama H, Skatrud JB. The ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 below eupnoea as a determinant of ventilatory stability in sleep. J Physiol. 2004;560:1–11. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep TT, Khan TR, Zhang R, Duffin J. Long-term facilitation of breathing is absent after episodes of hypercapnic hypoxia in awake humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;156:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffin J. Measuring the ventilatory response to hypoxia. J Physiol. 2007;584:285–293. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffin J, Mahamed S. Adaptation in the respiratory control system. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;81:765–773. doi: 10.1139/y03-049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanfulla F, Patruno V, Bruschi C, Rampulla C. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: is the “half-night polysomnography” an adequate method for evaluating sleep profile and respiratory events? Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1725–1729. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10081725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster HV, Dempsey JA, Birnbaum ML, Reddan WG, Thoden J, Grover RF, Rankin J. Effect of chronic exposure to hypoxia on ventilatory response to CO2 and hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1971;31:586–592. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.31.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster GE, McKenzie DC, Milsom WK, Sheel AW. Effects of two protocols of intermittent hypoxia on human ventilatory, cardiovascular and cerebral responses to hypoxia. J Physiol. 2005;567:689–699. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.091462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregosi RF, Mitchell GS. Long-term facilitation of inspiratory intercostal nerve activity following carotid sinus nerve stimulation in cats. J Physiol. 1994;477:469–479. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD. Episodic hypoxia induces long-term facilitation of neural drive to tongue protrudor and retractor muscles. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1761–1767. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01142.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Baker TL, Behan M, Mitchell GS. Expression of hypoglossal long-term facilitation differs between substrains of Sprague-Dawley rat. Physiol Genomics. 2001a;4:175–181. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.4.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Zabka AG, Baker TL, Mitchell GS. Phrenic long-term facilitation requires 5-HT receptor activation during but not following episodic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2001b;90:2001–2006. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris DP, Balasubramanian A, Badr MS, Mateika JH. Long-term facilitation of ventilation and genioglossus muscle activity is evident in the presence of elevated levels of carbon dioxide in awake humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R1111–R1119. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00896.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F, Coles SK, Bach KB, Mitchell GS, McCrimmon DR. Time-dependent phrenic nerve responses to carotid afferent activation: intact vs. decerebellate rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1993;265:R811–R819. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.4.R811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heym J, Steinfels GF, Jacobs BL. Activity of serotonin-containing neurons in the nucleus raphe pallidus of freely moving cats. Brain Res. 1982;251:259–276. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgel DW, Chapman KR, Faulks C, Hendricks C. Changes in inspiratory muscle electrical activity and upper airway resistance during periodic breathing induced by hypoxia during sleep. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:899–906. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.4.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupperets MD, Hopkins SR, Pronk MG, Tiemessen IJ, Garcia N, Wagner PD, Powell FL. Increased hypoxic ventilatory response during 8 weeks at 3800 m altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;142:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Fornal CA. Serotonin and motor activity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:820–825. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Martin-Cora FJ, Fornal CA. Activity of medullary serotonergic neurons in freely moving animals. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;40:45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan AS, Catcheside PG, O'Donoghue FJ, McEvoy RD. Long-term facilitation of ventilation is not present during wakefulness in healthy men or women. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:2129–2136. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00135.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien C, Bairam A, Joseph V. Chronic intermittent hypoxia reduces ventilatory long-term facilitation and enhances apnea frequency in newborn rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1356–R1366. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00884.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama K, Smith CA, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA. Chronic intermittent hypoxia increases the CO2 reserve in sleeping dogs. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1942–1949. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00735.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodadadeh B, Badr MS, Mateika JH. The ventilatory response to carbon dioxide and sustained hypoxia is enhanced after episodic hypoxia in OSA patients. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2006;150:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkead R, Bach KB, Johnson SM, Hodgeman BA, Mitchell GS. Plasticity in respiratory motor control: intermittent hypoxia and hypercapnia activate opposing serotonergic and noradrenergic modulatory systems. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2001;130:207–218. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehle MS, Sheel AW, Milsom WK, McKenzie DC. Two patterns of daily hypoxic exposure and their effects on measures of chemosensitivity in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1973–1978. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00545.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]