Abstract

This PDF receipt will only be used as the basis for generating PubMed Central (PMC) documents. PMC documents will be made available for review after conversion (approx. 2-3 weeks time). Any corrections that need to be made will be done at that time. No materials will be released to PMC without the approval of an author. Only the PMC documents will appear on PubMed Central -- this PDF Receipt will not appear on PubMed Central.

Students who are not motivated and do not try to do well are unlikely to achieve at a level consistent with their abilities. This research assessed the relationships over time between school engagement and parenting practices and peer affiliation among 6th–9th graders using latent growth models (LGM). Participants included 2,453 students recruited from 7 public middle schools who were assessed 5 times between fall of 6th and 9th grades as part of a program evaluation study. During this period school engagement and adjustment declined somewhat, while substance use, conduct problems, and problem behaving friends increased, and authoritative parenting practices declined. The significant, positive over-time associations between school engagement and parent involvement, expectations, and monitoring were fully mediated by growth in problem behaving friends. School adjustment mediated the relationship between school engagement and parent expectations. These findings suggest that authoritative parenting practices may foster school engagement directly and also indirectly by discouraging affiliation with problem behaving friends and facilitating school adjustment.

Keywords: school commitment, social influence, latent growth modeling

INTRODUCTION

Declines in achievement motivation and performance during early adolescence (Anderman, Maehr, & Midgley, 1999; Spera, 2005) are notable concerns of parents, teachers, and policy makers. Theory (Hawkins & Weiss, 1985; Deci & Ryan, 2000) and research have emphasized the links between students’ school engagement, motivation, adjustment, achievement, and behavior (Andrews & Duncan, 1997; Aunola, Stattin, and Nurmi, 2000; Barber & Olger, 2004). Students who want to do well and are reasonably well adjusted to school are likely to try hard and perform well academically relative to their abilities (Roeser & Eccles, 1998; Chen, 2005) and less likely to drop out or engage in anti-social behavior (Andrews & Duncan, 1997; Bryant, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 2003; McNeeley, Nonnemaker, & Blum, 2002; Resnick, Harris, & Blum, 1993; Simons-Morton, Crump, Haynie, Saylor, 1999; Steinberg & Avenevoli, 1998) than children who are unmotivated or disengaged from school. Therefore, improving school engagement may increase academic performance and reduce behavioral problems. Unfortunately, school engagement appears to decline in early adolescence along with achievement (Anderman et al., 1999). Because school engagement may be malleable, it is important to identify factors associated with it (Fredricks, Blumenfield, & Paris, 2004). Substantial research has documented the importance of classroom and school environment (Eccles, Flanagan, Lord, & Midgeley, 1996; Fredricks et al., 2004), but few studies have examined the importance of social influences on school engagement among early adolescents, although both peers and parents are important influences on many aspects of adolescent behavior (Simons-Morton & Haynie, 2002).

School Engagement

Early adolescents must deal with school transitions at an age when they may also be experiencing rapid physical, social, and cognitive development (Barber & Olsen, 2004). Effort is one important aspect of student achievement (Anderman, et al., 1999). However, the poor fit between the middle school environment, characterized by an emphasis on rules, control, and discipline, and early adolescents’ development stage, including their need to experiment with and assert their individuality, can undermine a student’s positive orientation to school (Eccles, Flanagan, Lord, & Midgeley, 1996). Early adolescence is also a period of transition in social influence, where peer influences tend to increase and parenting influences on behavior tend to decline in importance (Simons-Morton & Haynie, 2002). Like all self-directed behavior, the motivation to do well in school is complicated (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Walls & Little, 2005).

School engagement is a term that researchers have operationally defined in various ways in an effort to assess the extent to which school children are involved, connected, and committed to school and motivated to learn and achieve (Jimerson, Campos, & Greif, 2003; Skinner, Pappas, & Davis, 2005; Gonzalez-DeHass, Willems, & Holbein, 2005). School engagement is often measured as one aspect of school bonding (Jimerson et al, 2003). School engagement may have motivational, behavioral, emotional, and/or cognitive dimensions (Jimerson et al., 2003; Sinclair; Fredericks et al., 2004). The motivational dimension of engagement includes the desire to do well. The behavioral dimension of school engagement includes effort, attendance, attention in class, and participation in class and school activities. The emotional dimension of engagement includes students’ feelings about the school, teachers, and peers. The cognitive dimension includes students” perceptions and beliefs related to school and self, including self-efficacy, motivation, and aspirations. In general, aspects of school engagement are thought to be responsive to contextual and environmental factors, including school climate, classroom environments, and social relations with teachers and peers (Fredricks et al., 2004; Sirin & Rogers-Sirin, 2004; Chen, 2005). School connectedness (Resnick et al., 1993), school climate (Aunola, Stattin, & Nurmi, 2000; Barber & Olsen, 2004; Eccles et al., 1996) and school adjustment (Glasgow, Dornbush, Troyer, Steinberg, & Ritter, 1997; Simons-Morton & Crump, 2003) have been shown to be associated with various dimensions of school engagement. Peer and parent relations and behavior may also have important effects on school engagement.

Parenting

The authoritative parenting paradigm, introduced by Baumrind (1991) and elaborated upon by Darling & Steinberg (1993) and Maccoby & Martin (1994), suggests that the most effective pattern of parenting adolescents is one that is both demanding and responsive. Theoretically, by establishing and confirming high expectations, monitoring behavior, and remaining highly involved and supportive parents can continue to influence adolescent behavior throughout adolescence, despite increasing independence and competition from peers and other influences. Authoritative parenting practices appear to protect adolescents from early initiation of problem behavior (Baumrind, 1991; Steinberg, 2001; Simons-Morton & Haynie, 2002) and facilitate the development of social competence, school adjustment, and performance outcomes (Baumrind, 1991; Glassgow et al., 1997; Simons-Morton & Crump, 2003; Paulson, 1994; Steinberg, Lamborn, Darling, Mounts, & Dornbusch, 1994; Wentzel, 1998). For example, Steinberg et al., (1994) assessed a large sample of 14–18 year-olds twice one year apart and found that three measures of authoritative parenting practices were positively associated with school engagement and achievement and that parental involvement was more effective in promoting school success within the context of authoritative parenting. Parent involvement has been linked to middle school students’ engagement (Finn, 1993), educational aspirations (Rumberger, 1995), and achievement (Paulson, 1994), while parental control and demands were positively associated with classroom conduct and attentiveness (de Bruyn, Dekovic, & Meijnen, 2003). Unfortunately, parent involvement tends to decline during middle school (Simons-Morton & Crump, 2003; Spera, 2005).

Peers

Close correspondence between adolescent and peer behavior has commonly been observed with respect to substance use (Bray, Adams, Getz, & McQueen, 2003) and anti-social behavior (Dishion, Capaldi, Spraklen, & Li, 1995; Kiesner & Kerr, 2004). Not having friends during adolescence (Wentzel et al., 2004) and lack of peer support (Chen, 2005) are associated with poor school adjustment and motivation, while having friends at school is associated with greater involvement in school activities (Berndt & Keefe, 1995). Moreover, the characteristics of friends may also influence adolescent motivation and behavior (Berndt, 1999). Typically, adolescents make friends with those with whom they have frequent contact and share similar attitudes and interests and also develop attitudes and interests similar to their friends (Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Hartup & Stevens, 1997; Urberg, Degirmencioglu, & Pilgrim, 1997). There is limited evidence that peer groups influence adolescents’ enjoyment of school and academic performance (Berndt, 1999; Hartup & Stevens, 1997; Ryan, 2001; Steinberg, Dornbusch, & Brown, 1992). In a rare network analysis, Ryan (2001) found that peer group context predicted seventh graders’ enjoyment of school and achievement. Logically, associating with friends with positive attitudes toward school would encourage school engagement, while associating with problem behaving friends may discourage school engagement. However, no studies could be located that show a relationship between adolescent school engagement and problem behaving friends.

Study Purpose

The purpose of the study was to examine direct and indirect effects of authoritative parenting practices on aspects of school engagement and identify possible mediators of the relationship between authoritative parenting practices and school engagement. The data were from a randomized trial that evaluated the efficacy of a program designed to prevent adolescent substance use and conduct problems through social skills and problem solving training. The Going Places program included a 6th-8th classroom curriculum augmented by school-wide media and parent materials. Treatment group differences were found for smoking progression, outcome expectations for smoking, and friends who smoke (Simons-Morton, Haynie, Saylor, Crump, & Chen, 2004). In previous analyses of data from this study, school adjustment and parent involvement assessed at the beginning of 6th grade were found to be associated with school engagement at the end of 6th grade (Simons-Morton & Crump, 2003) and school engagement assessed at the beginning of 6th grade was negatively associated with initiation of alcohol use at the end of 6th grade (Simons-Morton, 2004). Other analyses of these data found that negative associations between authoritative parenting practices and smoking and drinking progression was mediated by growth in problem behaving friends (Simons-Morton, Chen, Abroms, & Haynie, 2004; Simons-Morton & Chen, 2005). The current research employs latent growth modeling of the over-time associations from 6th to 9th grade between school engagement, problem behaving friends, and authoritative parenting practices.

METHOD

Design and Study Participants

The research was conducted in the 7 middle schools of one middle income Maryland school district with a sizable population of low-income families (24% of students were enrolled in the national free or reduced-price school lunch program) as part of a program evaluation study. Schools were randomized, 3 to the treatment and 4 to the comparison control condition. Starting with the 1996 school year, two successive cohorts of 6th graders were recruited and surveyed in the fall and spring of the 6th grade (F6 and S6, respectively), the spring of the 7th grade (S7), the fall of the 8th grade (F8), and the fall of the 9th grade (F9).

The population of interest included 2969 students (72% white, 18% black, and 10% other) eligible to participate in the Time 1 assessment, of whom 2651 (87.8%) provided consent while in the 6th grade. Of these, 9 became ineligible during the study by failing a grade and 110 were newly classified as special education, leaving a sample of 2532, 79 of whom moved out of the school district or missed multiple assessments, leaving a final sample of 2453. Compared with the final sample, study participants lost to follow up were significantly more likely to be black, and to live with only one parent.

Questionnaires were administered by trained proctors, two in each intact class. As required by the school district, teachers remained in the classroom, but were not involved in the conduct of the survey. To protect confidentiality, students completed and turned in a cover page that included name, survey identification number, birth date, and homeroom teacher’s name that was kept separate from the questionnaires. The actual questionnaires had only a numerical identifier matching the one on the cover page. Study procedures were approved by the NICHD Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The survey instrument assessed background factors such as sex and race. Socioeconomic status was assessed by asking students if they were eligible for the free or reduced school lunch program (Hickman, Greenwood, & Miller, 1995), which in our sample was significantly associated with being in a single parent family and having less educated mothers. The survey also assessed school engagement, school adjustment, parenting practices, substance use, conduct problems, and the number friends who engage in problem behaving. Preliminary investigator-developed indices were subjected to factor analyses with a promax rotation to simplify interpretation of the factor structure. Analyses either confirmed that the structure of the data was consistent with the intended subscale structure or the composition of the subscales was revised to fit the empirical findings. Items were eliminated if they were associated with multiple factors (factor loadings approximately equal in magnitude) or not adequately associated with any factor (factor loading ≤.50) (Simons-Morton, Crump, Haynie, Saylor, Eitel, & Yu, 1999). Descriptions of the final scales follow, including the internal consistency alpha coefficients averaged over the 5 assessments.

School Engagement

There are no standard measures of school engagement, a concept that has multiple dimensions (Jimerson et al, 2003). We developed a measure of school engagement that included two items that assessed motivation to do well and one item that assessed effort. The items included the following: “I want to do well at this school,” “I take school seriously”, and “I pay attention in class”. Response options were strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree (Alpha = .81). The measure is similar to others commonly used to assess motivational aspects of school engagement (Connell, Spencer & Aber, 1994; Finn & Rock, 1997; Jessor, Turbin, & Costa, 1998; Wentzel et al., 2004). This measures of school engagement assessed at the beginning of the 6th grade was significantly associated with self reported grades in 7th (r = 0.24), 8th (r = 0.22), and 9th grade (r = 0.21), providing evidence of predictive validity.

School Adjustment

Adolescent school adjustment was assessed with a scale that consisted of 11 items from Harter (1982). Pilot testing determined that many students did not understand the original Harter response options, which we modified and pilot tested. Ultimately, we retained the original Harter items but simplified the response format so that students were asked how they were doing at school relative to other students (response options were much harder, a little harder, a little easier, much easier than other kids) on their school work, getting homework done on time, following rules, staying out of trouble, making friends, getting along with classmates and teachers (alpha = .87).

Achievement

Students were asked to indicate their grades on their latest end of term report card for their four core subjects (math, science, language arts, and social studies). Academic achievement is the average score of Math, Science, Language Arts and Social Sciences (A = 5, B = 4, C = 3, D = 2 and E = 1. For a sample of 68 sixth grade students, self-reported grades were found to be consistent with school records (kappa = .79).

Substance Use

Adolescent substance use was assessed by standard questions (Johnston, O’Malley, & Backman, 2002) that asked how many times in the past 12 months and in the past 30 days have you smoked a cigarette and/or drank alcohol. Non-overlapping categories of use were assigned to the adolescent’s smoking and drinking in the past 30 days, with a range for each substance of 0–4, as follows: 0 = no use; 1 = 1–2 times; 2 = 3–9 times; 3 = 10–19 and 4 = 20 times or more. The substance use score was the average of use categories for smoking and drinking (range = 0 to 4).

Conduct Problems (CP)

Adolescent CP was assessed by an index of items asking how often in the past year the youth had been in a physical fight, been in a physical fight in which someone got hurt, bullied or picked on someone younger or weaker, carried a weapon, stole something from a person or store, or marked something with graffiti (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Each item was rated on a 4 point scale with 0 = Zero, 1 = one to two times, 2 = three to five times, and 3 = six or more times in the past 12 months. Reponses were summed across the items to create the index (range = 0–18; alpha = .77).

Peer Influences

Peer influence was assessed by asking how many of the youth’s five closest friends participate in each of the following behaviors: drinking alcohol, bullying, being disrespectful to teachers, fighting, cheating, lying to parents, and marking property with graffiti (range = 0–35; alpha = .84).

Parent involvement included six items adapted from Hetherington, Clingempeel, Anderson, Deal, Stanley-Hagan, Hollier, & Linder, 1992) that focused on how much the parent knows (almost nothing, a little, a lot) about the teen’s friends, activities, interests, health habits, free time, and school (range = 6–18; alpha = .81).

Parental monitoring, included four commonly used items (Dishion & McMahon, 1998) that asked, “My parent …” “would find out if I misbehaved at school; checks up to see if I have done what they told me; expects me to work hard at school; and believes in having rules and sticking to them” (strongly agree, disagree, agree, or strongly disagree) (range = 4–16; alpha = .68).

Parental expectations included six investigator-developed items that asked how upset would your parent or guardian be if they found out that you …”smoked cigarettes, drank alcohol, were sent to the office for misbehavior, did poorly on a test, were disrespectful to at teacher, or got into a physical fight at school” (not at all, a little, somewhat, extremely) (range = 6–18; alpha = .82).

Analysis

Analyses were conducted on a sample that combined the treatment and control groups. The Going Places intervention was effective in preventing smoking progression, reducing outcome expectations for smoking, and reducing growth in friends who smoke, but did not have a significant effect on school engagement (Simons-Morton et al., 2004). Combining both groups in the analysis substantially increased statistical power and more fully represented the natural history of school engagement. Latent Growth Curve (LGC) analysis (Curran, 2000; Muthen & Cirram. 1997) was used to assess the interrelations between trajectories of school engagement, the number of problem behaving friends, and parenting behaviors over time. Because participants were from different schools, we tested the school effect at baseline by conducting an ANOVA comparing school engagement at 6th grade fall across the 7 schools and found no significant difference, with [F (6, 2198) = 1.62, p = 0.14]. Therefore, school was not included in subsequent analyses.

Mplus software (Muthen & Muthen, 2004, version 3) was used to estimate the LGC models. Conditional LGC models were used to evaluate the effect of demographic variables, including gender, SES, and race, and the intervention as time-invariant covariates on the growth factor. A significant path coefficient from a covariate leading to the latent intercept indicates that this covariate is associated with individual differences at baseline. A significant covariate to the slope reveals an association between this covariate and individual differences in the rate of change over time.

The parallel process methodology recommended in Muthen & Curren (1997, p.379) was used to evaluate the association of growth factors of school engagement, peer affiliation and, separately, parenting practices. The overall fit indices for evaluating LGC models included Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI ≥ 0.9 are generally considered acceptable and RMSEA <0.05 is regarded as good and <0.08 is acceptable (McDonald & Ho, 2002). Missing values were estimated within the model using the Maximum Likelihood method offered by MPlus version 3 based on the assumption of missing at random (MAR) allowing inclusion in the analyses of most participants.

RESULTS

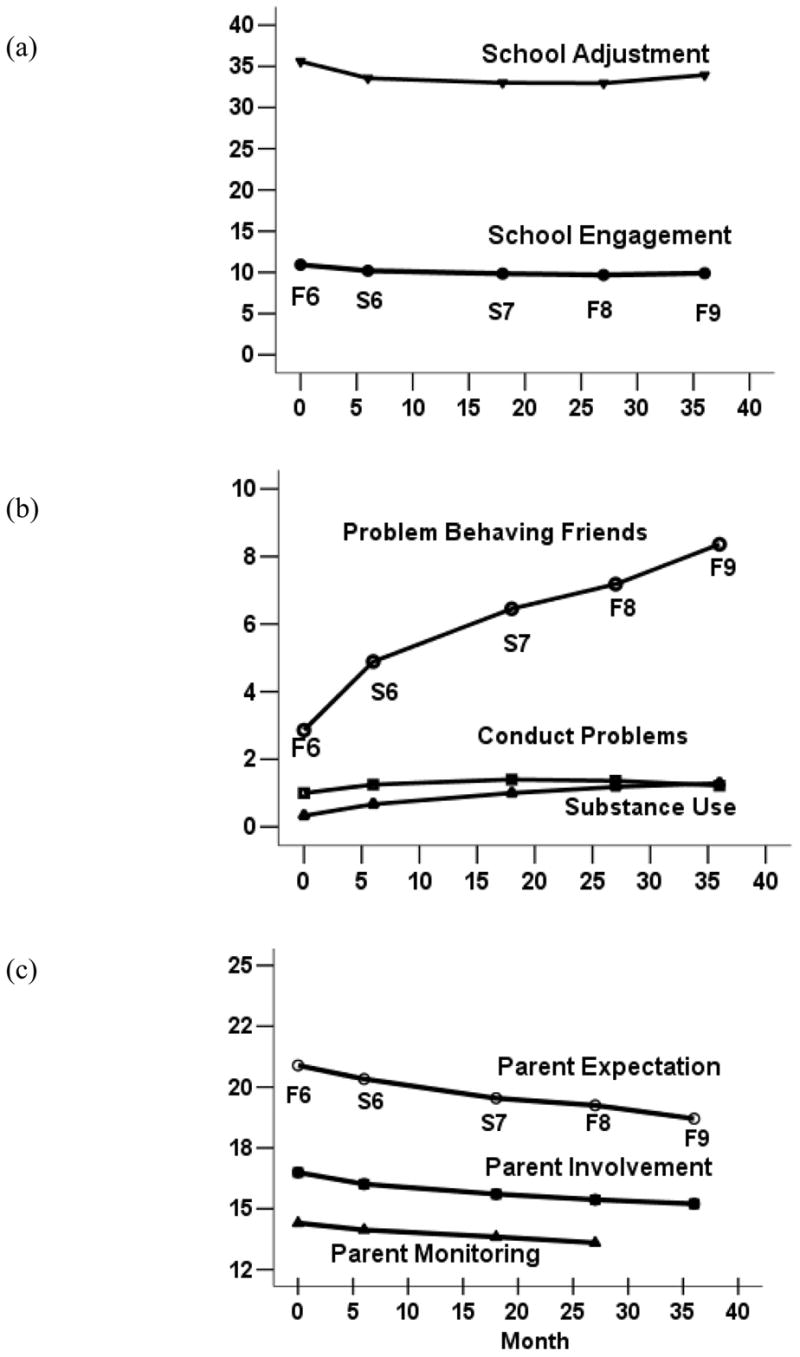

Our measure of school engagement correlated significantly over time from F6 (Fall of sixth) to F9 (Fall of 9th) with r = .44 at S6, r = .35 at S7, r = .31 at F8, and r = .26 at F9. Cross-sectional correlations between School Engagement and School Adjustment were r = .33 at F6 and .51 to .52 at S6 to F9). The correlation between School Engagement at F6 and School Adjustment at F9 was .28. Similarly, School Engagement and GPA were significantly correlated cross-sectionally at F6-F9 (r = .24 -.36), and prospectively, with r = .24 between School Engagement at F6 and GPA at F9. Line graphs showing the trajectory of adolescent school engagement, parenting practices, school adjustment, and PBF from the beginning of 6th to the beginning of 9th grade are shown in Figures 1a-c. Average school engagement and school adjustment declined modestly from the beginning of 6th grade to the 8th grade, and then increased somewhat in the 9th grade; substance use, conduct problems, and problem behaving friends increased; and Parental Involvement, Parental Monitoring, and Parent Expectations declined over time.

Figure 1.

Line Graphs for School Engagement, School Adjustment (a), PBF, CP, Substance Use (b), and Parenting Variables (c) (N = 2,453)

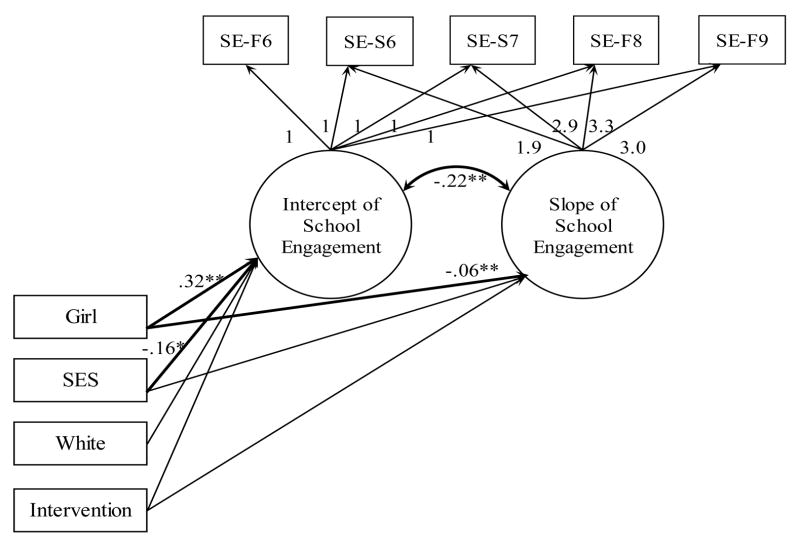

Figure 2 presents a conditional Linear LGC model with Gender, SES, Race, and intervention effect as covariates for the intercept and the slope of School Engagement trajectory. Gender was significantly associated with both intercept and slope, indicating that girls had relatively higher School Engagement at the beginning of 6th grade, which declined at a slightly faster rate than boys. School engagement was relatively higher among whites than non-whites at Time 1. The negative link between intercept and slope shows that School Engagement declined more among adolescents with higher initial School Engagement. The residual variances of the intercept and the slope significantly differed from zero (0.83 and 0.12, respectively), indicating that after controlling for the covariates, there were still significant individual differences in the School Engagement at the beginning of the 6th grade and in the rate of change over time. Model fit was good, with CFI=0.97, TLI = 0.96, and RMSEA = 0.042.

Figure 2.

Conditional LGM for Adolescents School Engagement from 6th Grade Fall to 9th Grade Fall (N = 2,453)

Note: CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.042. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. SE: School Engagement

School Engagement, School Adjustment, and Problem Behaving Friends

Parallel processing LGC model were estimated for the examination of cross-sectional and dynamic relations between adolescent school engagement and time varying variables of school adjustment, problem behaving friends (PBF), conduct problems (CP), and substance use, with gender, SES, race and intervention effect as covariates leading to the growth factors of both trajectories, shown in Table 1. The measures of model fit were good with all CFIs and TLIs ≥ 0.95 and RMSEAs ≤ 0.44. The intercepts and slopes of school adjustment and school engagement were positively associated, although the intercepts were negatively associated with the slopes, due to regression to the mean. The intercept and slope of school engagement was negatively associated with the intercepts and slopes of PBF, CP and substance use, respectively, indicating negative relations at the baseline and in the change over time.

Table 1.

LGM Parallel Process Model Evaluating the Relationships between School Engagement, School Adjustment, and Problem Behaving Friends, Conduct Problems, and Substance Use from 6th Grade to 9th Grade (N = 2,453)

| Time-Varying Variables | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | intercept with SE intercept | intercept to SE slope | SE intercept to slope | slope with SE slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School Adjustment | .98 | .97 | .037 | .56** | −.29** | −.25** | .37** |

| Problem Behaving Friends | .97 | .96 | .040 | −.47** | .15** | −.03 | −.45** |

| Conduct Problem | .98 | .97 | .034 | −.49** | .19** | .21** | −.25** |

| Substance Use | .97 | .95 | .044 | −.37** | .11* | −.07 | −.40** |

Note: SE: School Engagement

Coefficients adjusted for sex, SES, race, and treatment condition; standardized

p<0.01

School Engagement and Authoritative Parenting Practices

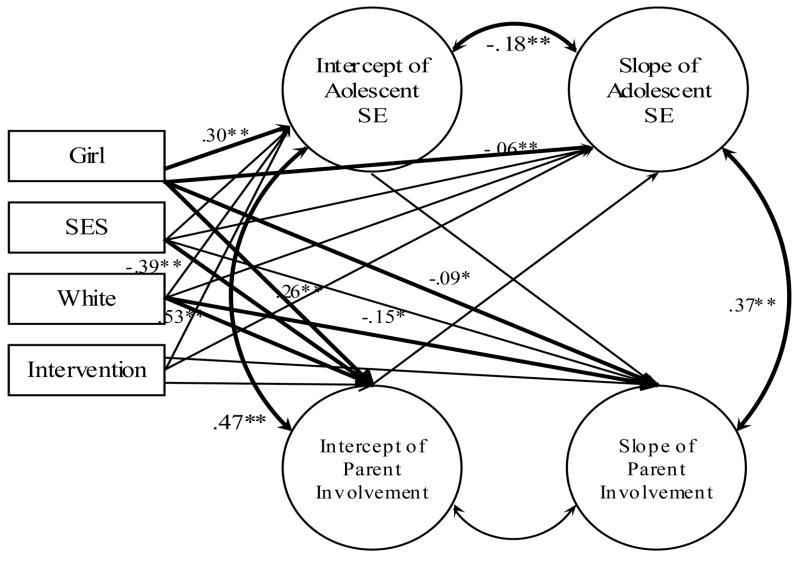

A parallel processing LGC model estimated the examination of cross-sectional and dynamic relations between adolescent School Engagement and authoritative parenting behaviors (see Table 2), with gender, SES, race, and intervention effect as covariates with paths leading to the growth factors of both trajectories. The models fit well with CFI ≥ 0.93, TLI ≥ 0.90, and RMSEA ≤ 0.05. In each model the intercepts and slopes were positively associated. Figure 3 shows the specific relationships for Parent Involvement. Gender is positively associated with the intercepts of School Engagement and Parent Involvement and negatively associated with the slopes of School Engagement and Parent Involvement, indicating that relative to boys, girls reported higher School Engagement and Parent Involvement at the beginning of 6th grade, but experienced relatively greater declines over time. SES was negatively association with the intercept (path coefficient = −.39), indicating that relative to higher SES youth, lower SES youth had lower Parent Involvement at the beginning of the study. Relative to other races, whites had higher Parent Involvement at the beginning of the study (path coefficient = .53), but with greater decline over time (path coefficient = −.15). The relationship between the two intercepts was positive (.47), indicating that higher Parent Involvement was associated with lower School Engagement at the beginning of 6th grade. The two slopes were positively associated (.37), indicating that the increase in Parent Involvement is associated with an increase in School Engagement over time. The paths from the intercept of School Engagement to the slope of Parent Involvement and the intercept of Parental Involvement to the slope of School Engagement were not significant, indicating a lack of prediction.

Table 2.

LGM Parallel Process Model Evaluating the Relationships between Parenting Behaviors and School Engagement from 6th Grade Fall to 9th Grade Fall (N = 2,453)

| Parenting Behavior | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | parent intercept with SE intercept | parent intercept to SE Slope | SE intercept to parent slope | parent slope With SE slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement | .96 | .95 | .04 | .47** | .08 | −.01 | .37** |

| Expectations | .97 | .95 | .04 | .36** | .01 | .01 | .45** |

| Monitoring | .98 | .97 | .03 | .60** | −.09 | −.09 | .49** |

Note: Coefficients adjusted for sex, SES, race, treatment condition; standardized SE: School Engagement

p <.05

p < 0.01

Figure 3.

LGM Analyses of the Parallel Process Relationships of Changes in Adolescent School Engagement and Parent Involvement from 6th Grade Fall to 9th Grade (N = 2,453)

Notes: CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.043. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; SE: School Engagement.

Intercepts assessed at F6; Slopes comprised of assessments at F6, S6, S7, S8, F9. Coefficients connecting slopes and intercepts are standardized that can range from −1.0 to 1.0.

Mediating Effects

Following the methodology recommended by Cheong, MacKinnnon & Khoo (2003), LGC models evaluating the mediating effects of School Adjustment and Problem Behaving Friends on the relationship between Parent Involvement and School Engagement was conducted. Essentially, for mediation to occur there must be a significant association between the mediator and the independent and dependent variables that reduces the relationship between the independent and dependent variable (Cheon, MacKinnon & Khoo, 2003). In latent growth modeling, this requires comparing in the same model (1) the relationships between the intercept of the independent variable (e.g. parenting behavior) and the slope of the dependent variable (e.g., school engagement); (2) the relationship between the slopes of the independent and dependent variables; and (3) the relationships between the slopes of the mediator and both the independent and dependent variables. The models fit the data well. As shown in Tables 3A, for parent involvement and parent monitoring school engagement was significantly associated with both school engagement and the parent variable, in each case reducing the relationship between he parent variable and school engagement to non-significant, consistent with full mediation. For parent expectations there was no evidence of mediation.

Table 3A.

LGM Evaluating School Adjustment as a Mediator of the Effects of Parent Behaviors on School Engagement from 6th Grade Fall to 9th Grade (N = 2,453)

| Parenting Behavior | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | parent slope to SE slope | parent slope to SA slope | SA slope To SE slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement | .92 | .89 | .061 | .10 | .67** | .55** |

| Expectations | .93 | .91 | .057 | .26** | .51** | .50** |

| Monitoring | .93 | .90 | .058 | .05 | .65** | .62** |

Note: SE: School Engagement; SA: School Adjustment

Standardized coefficients are shown.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

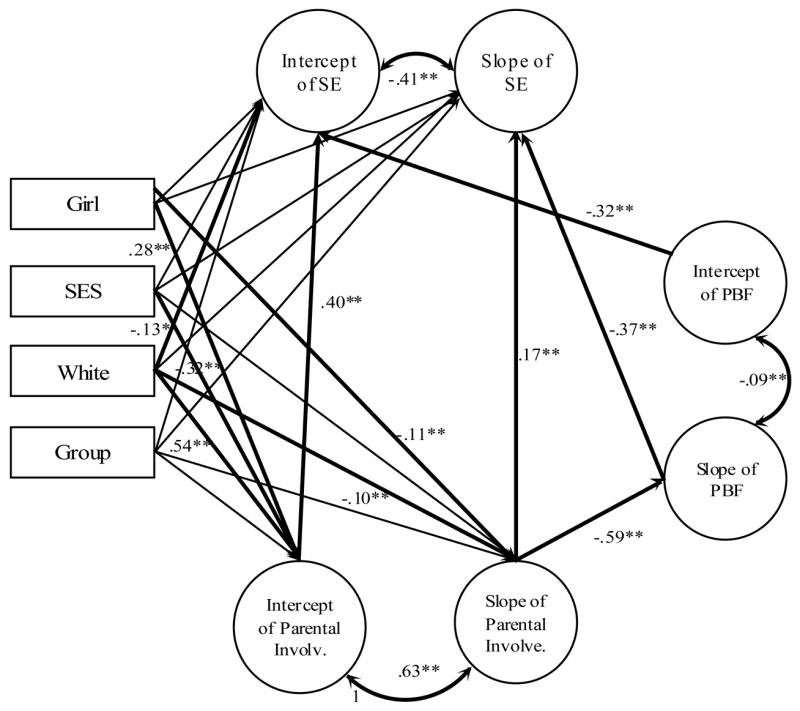

Shown in Table 3B are the findings from LGC models showing that the effects of Parent Expectations, Parent Monitoring, and Parent Involvement on School Engagement were partially mediated by Problem Behaving Friends. In each case both the direct relationship of the parent variable with school engagement remained significant and negative, while problem behaving friends was also significant related to both the parent variables and school engagement. This finding indicates partial mediation of the relationships between parenting behaviors and school engagement by problem behaving friends. The combination of the effect of the direct relationship between parent behavior and school engagement and the indirect relationship between problem behaving friends and school engagement were greater than effects of individual The partial mediation by PBF of the relationship between School Engagement and Parent Involvement is illustrated in Figure 4. The path coefficient from the slope of parent involvement to the slope of School Engagement (0.17, p < 0.05) shows a significant direct effect. The slope of Parent Involvement was negatively associated (−.59) with the slope of Problem Behaving Friends, which was negatively associated with the slope of School Engagement (−.37), representing an indirect effect on School Engagement through the slope of Problem Behaving Friends of −.37 × −.59 = .96. The significant direct and indirect effects indicate that Problem Behaving Friends partially mediated the relationship between Parent Involvement and School Engagement over time.

Table 3B.

LGM Evaluating Problem Behaving Friends as a Mediator of the Effects of Parent Behaviors on Adolescent School Engagement from 6th Grade Fall to 9th Grade (N = 2,453)

| Parenting Behavior | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | parent slope to SE slope | parent slope to PBF slope | PBF slope To SE slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement | .93 | .91 | .05 | .17** | −.37** | −.59** |

| Expectations | .93 | .90 | .06 | .23** | −.36** | −.64** |

| Monitoring | .95 | .92 | .05 | .13* | −.42** | −.57** |

Note: SE: School Engagement; PBF: Problem Behaving Friends

Standardized coefficients are shown.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Figure 4.

Latent Growth Curve Analyses of Problem Behaving Friends as a Mediator for the Effect of Parental Involvement on Adolescent School Engagement from 6th Grade Fall to 9th Grade Fall (N = 2,453)

Notes: CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.054; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0,01; SE: School Engagement; Involv.: Parent Involvement; PBF: Problem Behaving Friends Intercepts assessed at F6; Slopes comprised of assessments at F6, S6, S7, S8, F9. Coefficients connecting slopes and intercepts are standardized that can range from −1.0 to 1.0.

DISCUSSION

This study examined relationships over time between authoritative parenting practices, school engagement, school adjustment, and conduct problems, substance use, and problem behaving friends. The positive relationship over time between school engagement and school adjustment is consistent with findings in other research (Glasgow et al, 1997; Wentzel et al., 2004) and suggests that students who are better adjusted to school may be more inclined to engage in greater effort, or possibly that those who try hard in school are better adjusted. The negative relationships over time between school engagement and conduct problems, substance use, and problem behaving friends are consistent with the findings of Bray et al. (2003) for substance use, Dishion et al. (1995) and Kiesner & Kerr (2004) for anti-social behavior. The findings suggest that antisocial behavior is inconsistent with school engagement. The negative relationship over time between school engagement and problem behaving friends is consistent with Berndt (1999). The behavior of close peers has long been known to be associated with adolescent behavior as adolescents are both shaped by the behavior and attitudes of their friends and develop friendships with adolescents who share their interests and values (Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Wentzel et al., 2004). It makes sense that having friends who engage in problem behavior would discourage school engagement, although this has not frequently been demonstrated.

The most important findings are the positive relationships over time between authoritative parenting practices and school engagement. While other studies have identified significant relationships between various parenting practices and school engagement, adjustment, and achievement (Baumrind, 1991; Glassgow et al., 1997; Spira, 2004; Wentzel, 1998), this is one of the first reports using LGC analyses to show positive relationships over time. In the only other study using similar LGC methods, Chen (2005) found that the relationships between academic support from teachers, parents, and peers and academic achievement among Hong Kong adolescents was moderated by school engagement. The findings of the current study are particularly strong because similar patterns of positive relationships with school engagement were found for three measures of authoritative parenting. The relationships between authoritative parenting practices and school engagement were fully mediated by school adjustment and partially mediated by problem behaving friends. The data are consistent with the conclusion that authoritative parenting practices provide both direct and indirect effects on school engagement, with important indirect effects coming from positive effects of parental expectations on school adjustment and negative effects of authoritative parenting practices on the growth over time in problem behaving friends.

Many benefits of authoritative parenting practices on adolescent development have been identified (Steinberg, 2001). Various authoritative parenting practices have been shown to protect against substance use (Steinberg et al., 1994) and conduct problems (Dishion & McMahon, 1998), and to promote school adjustment and achievement (Baumrind, 1991; Glassgow et al., 1997; Gonzalez-DeHass et al., 2005). Consistent with theory (Baumrind, 1991; Steinberg, 2001; Darling & Steinberg, 1994), authoritative parenting practices provide a range of positive effects on adolescent development and behavior. Despite increases in peer influence and independence from family the positive influence of authoritative parenting practices remains substantial during adolescence. The current study adds to the literature in two ways. First, it shows that each of the authoritative parenting practices measured acted in similar manner, providing direct effects on school engagement. Second, the data indicate that authoritative parenting may encourage school engagement by fostering school adjustment and discouraging the development of problem behaving friends. Other research has shown that authoritative parenting practices protect adolescents against deviant behavior by discouraging the adoption of problem behaving friends. Previous analyses of data from this study indicated that authoritative parenting practices protected against substance use program directly and indirectly by discouraging growth in problem behaving friends (Simons-Morton et al., 2004; Simons-Morton & Chen, 2005). This is the first study to show such a relationship with school engagement. However, it is not clear the extent to which parents actively attempt to influences adolescent friendship development. Probably, authoritative parents both foster the development of acceptable and prosocial friends and discourage the adoption of unacceptable and anti-social friends.

School engagement is an emerging concept of substantial complexity that has been measured in a variety of ways (Jimerson et al, 2003). A limitation of the present study is that the measure of school engagement for this study included only three items addressing only two of the dimensions of engagement, effort and motivation to do well in school. While limited, we found evidence of the validity of this measure in its significant association with GPA. However, future research should address measures of multiple dimensions of school engagement. The study is limited in other ways. Notably, some unmeasured other variables may be involved in the relationship between parenting practices and school engagement. For example, we did not assess values related to school, school climate, academic goal orientation, expectations for success, or specific aspects of academic effort, all of which could be important. Also, it is not clear how association with problem behaving friends may discourage school engagement over time and no attempt was made to sort out the independent effects of problem behaving friends from adolescent conduct problems and substance use, which are known to be associated in complex ways (Ennett & Bowman, 1994).

It can be difficult for parents to remain involved in the lives of their early adolescent children, given the complexity of modern life, the nature of early adolescent development, and the impersonal environments of many modern middle schools. However, by overcoming these obstacles, parents may facilitate their children’s school adjustment and engagement. Parents are challenged to find ways to remain actively involved in the lives of their early adolescent children and reminded that peers are an important source of influence on adolescent behavior and parents can exercise some influence on the development of adolescent friendships.

References

- Anderman EM, Maehr ML, Midgley C. Declining motivation after the transition to middle school: schools can make a difference. Journal of Research and Development in Education. 1999;32:131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Duncan SC. Examining the reciprocal relation between academic motivation and substance use: effects of family relationships, self-esteem, and general deviance. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;20:523–549. doi: 10.1023/a:1025514423975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aunola K, Stattin H, Nurmi JE. Adolescents’ achievement strategies, school adjustment, and externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JA. Assessing transitions to middle and high school. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2003;19:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11:56–95. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Friends’ influence on students’ adjustment to school. Educational Psychologist. 1999;34:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Keefe K. Friends’ influence on adolescents’ adjustment to school. Child Development. 1995;66:1312–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray JH, Adams GJ, Getz JG, McQueen A. Individuation, peers, and adolescent alcohol use: A latent growth analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:553–564. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant A, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. How academic achievement, attitudes, and behaviors relate to the course of substance use during adolescence: A 6-year, multi-wave national longitudinal study. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:361–397. [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJL. Relation of academic support from parents, teachers, and peers to Hong Kong adolescents’ academic achievement: the mediating role of academic engagement. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs. 2005;131:77–127. doi: 10.3200/MONO.131.2.77-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong LW, MacKinnon D, Khoo ST. A latent growth modeling approach to mediation analysis. In: Collins L, Sayer A, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 390–392. [Google Scholar]

- Connell JP, Spencer MB, Aber JL. Educational risk and resilience in African-American youth: Context, self, action, and outcomes in school. Child Development. 1994;65:493–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ. A latent curve framework for the study of developmental trajectories in adolescent substance use. In: Rose J, Chassin L, Presson C, Sherman S, editors. Multivariate applications in substance use research: new methods for new questions. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruyn EH, Dekovic M, Meijnen GW. Parenting, goal orientation, classroom behavior, and school success in early adolescence. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:393–412. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry. 2000;11:227–268. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi D, Spracklen KM, Li F. Peer ecology of male adolescent drug use. Developmental Psychopathology. 1995;7:803–824. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RH. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: a conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Flanagan CA, Lord S, Midgley C. Schools, families, and early adolescents: what are we doing wrong and what can we do instead? Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1996;1:267–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity: The case of adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:653–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn JD. School engagement and students at risk. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Finn JD, Rock DA. Academic success among students at risk for school failure. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1997;82:221–261. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research. 2004;74:59–109. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow KL, Dornbush SM, Troyer L, Steinberg L, Ritter PL. Parenting styles, adolescents’ attributions, and educational outcomes in nine heterogeneous high schools. Child Development. 1997;68:507–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-DeHass AR, Willems PP, Holbein MFD. Examining the relationship between parental involvement and student motivation. Educational Psychology Review. 2005;17:99–123. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WE, Stevens N. Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Weis JG. The social development model: an integrated approach to delinquency prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1985;6:73–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01325432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG, Anderson ER, et al. Coping with marital transition. Monograph of the Society for Research on Child Development. 1992;57:2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hichman CW, Greenwood G, Miller MD. High school parent involvement: Relationships with achievement, grade level, SES, and gender. Journal of Research & Development in Education. 1995;28:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Tuirbin MS, Costa FM. Protective factors in adolescent health behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:788–800. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.3.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimerson SR, Campos E, Greif JL. Toward an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. The California School Psychologist. 2003;8:7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Secondary school students. Vol. 1. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2002. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2001. (NIH Publication No. 02–5106) [Google Scholar]

- Kiesner J, Kerr M. Families, peers, and contexts as multiple determinants of adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:493–495. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In: Wiley J, editor. Socialization, personality, and social development. New York: Wiley; 1994. pp. 2–101. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, Ho M. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analysis. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely CA, Nonnemaker JM, Blum RW. Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of School Health. 2002;72:138–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Curran PJ. General longitudinal modeling of individual differences in experimental designs: a latent variable framework for analysis and power estimation. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:371–402. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson SE. Relations of parenting style and parental involvement with ninth-grade students’achievement. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1994;14:250–267. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Harris LJ, Blum RW. The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 1993;29:S3–S9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb02257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW, Eccles JS. Adolescents’ perceptions of middle school: relation to longitudinal changes in academic and psychological adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1998;8:123–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rumberger RW. Dropping out of middle school: A multilevel analysis of students and schools. American Educational Research Journal. 1995;32:583–625. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AM. The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescent motivation and achievement. Child Development. 2001;72:1135–1150. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG. Prospective association of peer influence, school engagement, alcohol expectancies, and parent expectations with drinking initiation among sixth graders. Addictive Behavior. 2004;29:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Chen R. Latent growth curve analyses of parent influences on drinking progression among early adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:5–13. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Chen R, Abroms L, Haynie D. Latent growth curve analyses of peer and parent influences on smoking stage progression among early adolescents. Health Psychology. 2004;23:612–621. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Crump AD. The association of parental involvement and social competence with school adjustment and engagement among sixth graders. Journal of School Health. 2003;73:121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb03586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Crump AD, Haynie DL, Saylor KE, Eitel P, Yu K. Psychosocial, school, and parent factors associated with recent smoking among early adolescent boys and girls. Preventive Medicine. 1999;28:138–148. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Crump AD, Saylor K, Haynie D. Student-school bonding and adolescent problem behavior. Health Education Research. 1999;14:99–107. doi: 10.1093/her/14.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Haynie DL. Application of authoritative parenting to adolescent health behavior. In: DiClemente R, Crosby R, Kegler M, editors. Emerging theories and models in health promotion research and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2002. pp. 100–125. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Haynie D, Saylor K, Crump AD, Chen R. The effects of the Going Places Program on early adolescent substance use and anti-social behavior. Prevention Science. 2004;5:101–111. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirin SR, Rogers-Sirin L. Exploring school engagement of middle-class African-American adolescents. Youth and Society. 2004;35:323–340. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner CH, Pappas DN, Davis KA. Enhancing academic engagement: providing opportunities for responding and influencing students to choose to respond. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42:389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Spera C. A review of the relationship among parenting practices, parenting styles, and adolescent school achievement. Educational Psychology Review. 2005;17:125–146. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Avenevoli S. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1998. Disengagement from School and Problem Behavior in Adolescence: A Developmental-contextual Analysis of the Influences of Family and Part-time Work; pp. 392–424. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Dornbusch SM, Brown BB. Ethnic differences in adolescent achievement: An ecological perspective. American Psychologist. 1992;47:723–729. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.6.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Darling N, Mounts NS, Dornbusch SM. Over-time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent and neglectful families. Child Development. 1994;65:754–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Degirmencioglu SM, Tolson JM, Holliday-Sher K. Developmental Psychology. 1995;33:834–844. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls TA, Little TD. Relations among personal agency, motivation, and school adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2005;97:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1998;90:202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR, Barry CM, Caldwell KA. Friendships in middle school: Influences on motivation and school adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2004;96:195–203. [Google Scholar]