Abstract

Sufficient folate supplementation is essential for a multitude of biological processes and diverse organ systems. At least five distinct inherited disorders of folate transport and metabolism are presently known, all of which cause systemic folate deficiency. We identified an inherited brain-specific folate transport defect that is caused by mutations in the folate receptor 1 (FOLR1) gene coding for folate receptor alpha (FRα). Three patients carrying FOLR1 mutations developed progressive movement disturbance, psychomotor decline, and epilepsy and showed severely reduced folate concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated profound hypomyelination, and MR-based in vivo metabolite analysis indicated a combined depletion of white-matter choline and inositol. Retroviral transfection of patient cells with either FRα or FRβ could rescue folate binding. Furthermore, CSF folate concentrations, as well as glial choline and inositol depletion, were restored by folinic acid therapy and preceded clinical improvements. Our studies not only characterize a previously unknown and treatable disorder of early childhood, but also provide new insights into the folate metabolic pathways involved in postnatal myelination and brain development.

Introduction

Folates are essential cofactors for one-carbon methyl transfer reactions and are crucial for a variety of biological processes, such as synthesis and repair of DNA,1–3 regulation of gene expression,4,5 and synthesis of amino acids and neurotransmitters.6,7 Folate deficiency is one of the major dietary health problems worldwide.8 Humans require 400–600 μg of dietary folate per day, and children and adolescents are the population at the greatest risk of suffering nutritional folate deficiency. Dietary folate is taken up in the gut, metabolized in the liver to 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate (MTHF), then distributed by the bloodstream. Cellular uptake of MTHF is mediated by the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT; SLC46A1 [MIM ∗611672]), the reduced folate carrier (RFC; SLC19A1 [MIM ∗600424]), and by two GPI-anchored receptors, folate receptor alpha (FRα [MIM ∗136430]) and beta (FRβ [MIM ∗136425]).9 FRα is distributed mainly at epithelial cells, such as choroid plexus, lung, thyroid, and renal tubular cells, whereas FRβ is located mainly within mesenchymal derived cells, such as red blood cells. Both are high-affinity receptors that function at the physiological nanomolar range of extracellular folate concentrations. RFC is ubiquitously distributed and represents a low-affinity folate-transporting system with bidirectional transport across membranes.10 PCFT is highly expressed in the small intestine, where folates are absorbed at low pH in the microclimate of the intestinal epithelium. However, PCFT is also expressed in many other tissues, including the brain, where it might export folates from acidified endosomes after FRα-mediated endocytosis.11 At least five distinct inherited disorders of folate transport and metabolism are presently known, all of which lead to generalized folate deficiency.12–17 Besides these inherited disorders, an autoimmune folate deficiency with a variable clinical phenotype has also been described.18

To our knowledge, we describe here the first inherited disorder of brain-specific folate deficiency. Loss-of-function mutations in the FOLR1 gene (MIM ∗136430) coding for the FRα predominantly impairs cerebral folate transport. This autosomal-recessive disorder manifests in late infancy with severe developmental regression, movement disturbances, epilepsy, and leukodystrophy. Folinic acid therapy can reverse the clinical symptoms and improve brain abnormalities and function.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Two siblings of healthy, unrelated German parents, patients 1 and 2, had an uneventful medical history and were found to be compound heterozygous for two nonsense mutations in the FOLR1 gene coding for FRα. At the time of diagnosis, at the age of 3 years and 19 months, the older boy was severely handicapped, wheel-chair bound, and suffered from therapy-resistant epileptic seizures. Oral folinic acid treatment was started. Since then, the frequency and severity of epileptic seizures have declined and the boy has started to walk with support. His sister, younger by two years, was treated with folinic acid directly after the onset of her first motor symptoms, at the age of 2 years and 3 months. She completely recovered and has not developed clinical symptoms since then. Patient 3, carrying a homozygous duplication in the FOLR1 gene, is the daughter of healthy parents who originate from a small Italian village. At the age of 5 years, she was severely handicapped, mentally retarded, and suffered from frequent epileptic seizures, at which point she was diagnosed as having cerebral folate transport deficiency and folate treatment was started. Her clinical condition has also slowly improved since then. The institutional ethics committee approved the described investigations, and the parents gave informed consent before each examination.

Measurements of Cerebrospinal Fluid Metabolites

MTHF in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was measured with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), with fluorimetric detection essentially as described before.19 In all three patients, analysis of CSF disclosed a very low MTHF concentration of below 5 nmol/L. The MTHF concentration in CSF increased during folinic acid treatment. In patient 1, it was 1.4 nmol/L before the start of therapy and 41 nmol/L on treatment with 5 mg folinic acid/kg/day. On 3.5 mg folinic acid/kg/day, CSF folate was 53 nmol/L in patient 2 at the age of 2.5 yrs. Reference values for CSF folate in the age group of 2–5 years amount to: median 74 nmol/L, range min–max 43–159, in 35 controls.19 Normal concentrations were found in CSF for total protein, glucose, amino acids, and the neurotransmitter metabolites HVA, MHPG 5HIAA, and methylmalonic acid before the start of therapy. Myo-inositol in CSF was determined with gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) essentially as according to Jansen.20 Before the start of therapy, in patient 1 myo-inositol in CSF amounted to 160 μmol/L, whereas a concentration of 143 μmol/L was found on treatment of 5 mg folinic acid/kg/day (range in ten age-matched disease-affected controls not on folate or folinic acid therapy: 117–252; age range 0.8–5.5 years). In patient 2, the CSF myo-inositol was normal under folinic acid supplementation (238 μmol/L).

DNA Sequencing

For amplification and sequencing of genomic DNA fragments of FRα, the primer combinations hFOLR1gDNA6206F (5′-GGGCTGGGGAATCAAGGACTAAGAGG-3′) and hFOLR1gDNA6611R (5′-CCAGCAACTCAGCCCCGAATAGAACT-3′) for exon 3 and hFOLR1gDNA6863F (5′-AATTTGGAGTTGTAGGGCTGGCAGAC-3′) and hFOLR1gDNA7404R (5′-GGGAATTGGAAAACAAAACAGTCACG-3′) for exon 5 were used. The BigDye Terminator Kit was used for semiautomated sequencing, in accordance with the recommendations of the manufacturer (Perking Elmer Applied Biosystems).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from patient fibroblasts and lymphocytes with the RNeasy Kit as described by the manufacturer (QIAGEN). For cDNA synthesis, the Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) was used. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used for analysis of the mRNA abundance of FRα and FRβ in cultured fibroblasts and leukozytes from patients and controls, respectively, and in CHO-K1 cells stably expressing wild-type (WT) or mutant FRα. Total mRNA was prepared and reverse transcription was done with the use of a cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). Specific primer pairs are given in Table S1 (available online) and were used with 2 μl of cDNA. PCR amplification was carried out with 37 cycles and 59°C annealing temperature. RT-PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and compared against GAPDH.

Folate Binding

Patient fibroblasts or stably transfected CHO-K1 cells in 6-well plates were washed with acid buffer, equilibrated to neutral HEPES buffer, then exposed to 5 nmol/L [3H]folate or 5 nmol/L [3H]folate + 110 nmol/L methotrexate for 15 min. [3H]folate bound to the cell surface was released with acid buffer and measured on a liquid scintillation counter. Specific folate binding was calculated from the difference between [3H]folate bound in the presence and absence of 500 nmol/L nonlabeled folate. [3′,5′,7′,9-3H]Folate was obtained from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA, USA). Patient fibroblasts or stably transfected CHO-K1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates 24 hr before the binding assay. Cells were washed with ice-cold acid buffer (10 mmol/L NaAc, 150 mmol/L NaCl [pH 3.5]). After a washing step with ice-cold HEPES-buffered saline (HBS) (20 mmol/L HEPES, 140 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 2 mmol/L MgCl2, 5 mmol/L glucose [pH 7.4]), cells were exposed to 5 nmol/L [3H]folate or 5 nmol/L [3H]folate + 110 nmol/L methotrexate for 15 min in ice-cold HBS. At this concentration, methotrexate selectively inhibits folate binding to the RFC but does not affect FRα-related binding. Also, at neutral pH, folate does not bind to the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT). Cells were then washed three times with [3H]folate-free HBS. [3H]folate bound to the cell surface was released with acid buffer (1 mL) and measured on a liquid scintillation spectrometer. Specific folate binding was calculated from the difference between [3H]folate bound in the presence and absence of 500 nmol/L nonlabeled folate. The adherent cells were subsequently lysed, and protein was determined with the use of the BCA Protein Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). All experiments were repeated at least three times and gave very similar results.

Retrovirus Infection

Human FRα and FRβ cDNA were introduced into the vector pLNCX2 (Clontech). The plasmids were transfected into the packaging cells, Retro Pack PT67 (Clontech), and the culture supernatant was filtered and added onto the patient fibroblasts. Folate binding studies were carried out as described above.

Expression of WT and Mutant FRα in CHO-K1 Cells

FRα cDNA was cloned into the expression vector pcDNA3.1(-) (Invitrogen). Mutant FRα[p.K44_P49 dup] was obtained by primerless PCR.21 Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were either transiently or stably transfected with WT and mutant FRα and then assayed for folate-binding capacity either directly or after 14 days of selection with G418. The folate-binding assay was performed as described above.

Immunoblot Analysis of FRα Expression

Stable CHO-K1 clones expressing WT or mutant FRα were collected in CellLytic M Cell Lysis Reagent (Sigma), and lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE (12% gel) under nonreducing conditions and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed with a monoclonal anti-human FRα antibody (Mov18, ALEXIS Biochemicals).

Immunofluorescent Microscopy

CHO-K1 cells stably expressing WT or mutant FRα were permeabilized and blocked with 5 mg/ml saponin in PBS for 1 hr at room temperature and subsequently incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-human FRα (Mov18, 1:100 dilution) and rabbit polyclonal anti-calreticulin (1:50 dilution) in PBS containing 1 mg/ml saponin. After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 546 for 1 hr in the dark. Coverslips were mounted and viewed with a Leica NTSC laser confocal microscope in sequential scan mode. At least 50 cells per coverslip were examined under the microscope, and representative cells were photographed.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed with either a 1.5 Tesla or a 3 Tesla scanner. The two siblings, patients 1 and 2, underwent localized proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) studies at 3 Tesla (Magnetom Trio, Siemens Healthcare) before and after the onset of folinic acid treatment. Fully relaxed MR spectra were acquired with the use of the STEAM sequence as described previously.22 Metabolites, quantified by LCModel23 and compared to age-matched controls, include the neuroaxonal marker N-acetylaspartate and N-acetylaspartylglutamate (tNAA), creatine and phosphocreatine (tCr) as compounds linked to energy metabolism, choline-containing compounds (Cho) involved in membrane turnover, and the glial marker myo-inositol (Ins).24 The third patient had already received folate therapy when we included her in the study and therefore no proton MRS was performed.

Real-Time PCR for Quantification of Human Folate Transporter Expressions

For real-time PCR analysis, human cDNA was purchased from BioChain (Hayward, CA). Real-time PCR was used for verifying the expression levels of FRα, FRβ, FRγ, RFC, and PCFT in different tissues with the use of the iQ SYBR Green fluorescent intercalation dye (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). For each gene, primer pairs were designed (Table S1), covering exon boundaries so that amplification of genomic DNA was avoided. The PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 15 μl, with the use of 7,5 μl of iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), 3 pmol of each primer, and 0,25 ng of cDNA. Before amplification, an initial denaturation step at 98°C was performed, ensuring activation of the polymerase and complete denaturation of the cDNA. All PCR reactions were performed with 40 cycles and 59°C annealing temperature for FRα, FRβ, FRγ, and RFC or 63°C for PCFT. Amplified products underwent melting curve analysis after the last cycle for specifying the integrity of amplification. All runs included a negative cDNA control consisting of PCR-grade water, and each sample was measured in triplicate. The mRNA values were expressed relative to the housekeeping gene GAPDH and calculated as n-fold expression relative to that.

Results

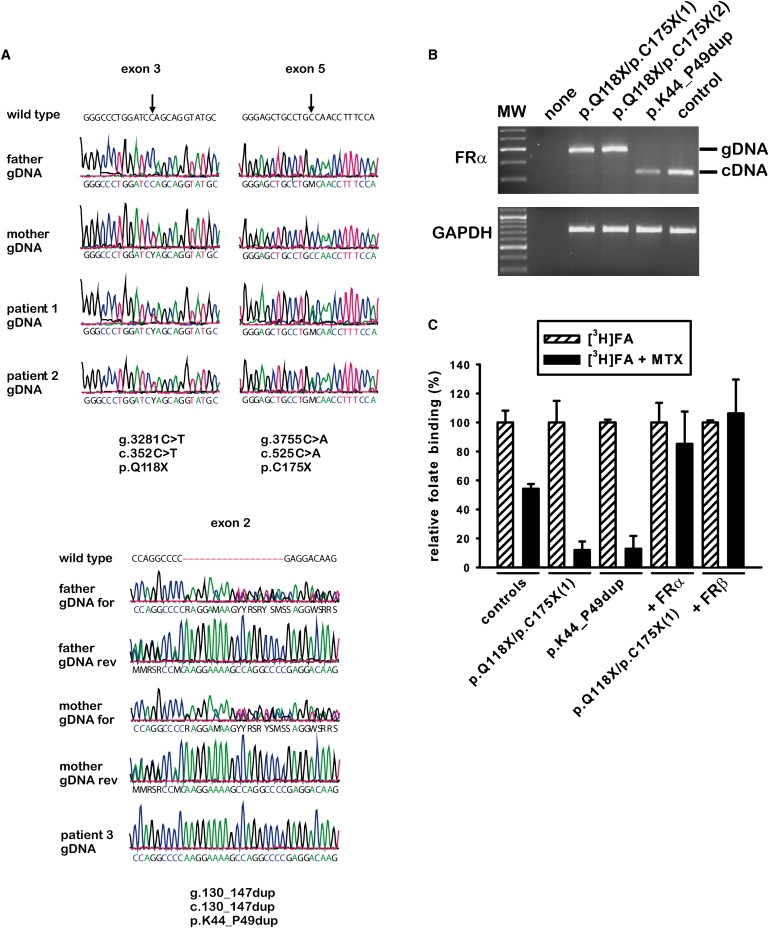

We have screened 12 patients with low MTHF concentrations in the CSF and normal MTHF blood levels for folate transporter defects and found three children with pathogenic mutations in the FOLR1 gene. All three children experienced the onset of symptoms beyond the second year of life. Analysis of genomic DNA from two siblings (patients 1 and 2) revealed two compound-heterozygous nonsense mutations, p.Q118X and p.C175X, in FOLR1 (Figure 1A). In a third patient (patient 3), we identified a homozygous in-frame duplication, p.K44_P49dup, in FOLR1. All three FOLR1 mutations have been deposited to the NCBI dbSNP (see Web Resources). Semiquantitative PCR analysis on patient cDNA showed an apparently normal transcript length in the case of the duplication but no transcript for the nonsense mutations (Figure 1B). Binding studies demonstrated a loss of FR-specific folate binding to patient fibroblasts (Figure 1C). Folate binding could be rescued by retroviral transfection of fibroblasts with WT FRα. Interestingly, introduction of WT FRβ that is not expressed in fibroblasts could also restore FR-specific binding in patient fibroblasts. No pathogenic mutations were detected in the genes coding for other folate transporters, and the presence of autoantibodies against the folate receptors in serum was excluded. DNA analyses of 105 controls (210 alleles) revealed none of the three mutations in the FOLR1 gene (data not shown).

Figure 1.

FOLR1 Mutations Cause Deficient Folate Binding to FRα

Sequencing of the FOLR1 gene coding for FRα disclosed two nonsense mutations, p.Q118X and p.C175X, in patient 1 and his younger sister, patient 2 (A). Compound heterozygosity was proven by the presence of both mutant alleles in either the maternal or the paternal DNA. Analysis of genomic DNA (and cDNA, not shown) of patient 3 revealed a homozygous duplication, p.K44_P49dup, in the FOLR1 gene, which caused an insertion of the amino acid sequence “KEKPGP” without change of the reading frame. Sequencing of the parents' DNA showed that the father and mother are heterozygous carriers of the duplication p.K44_P49dup. Semiquantitative RT-PCR with cDNA from all three patients (B) showed an almost normal transcript size for patient 3 carrying the duplication p.K44_P49dup but hardly any transcript for the two siblings with the nonsense mutations. Instead, the amplified fragment size corresponds to the product of the contaminating genomic DNA, suggesting that the two premature termination codons lead to premature mRNA decay. Specific binding of [3H]folate to patient fibroblasts was determined in the presence or absence of 110 nmol/L methotrexate (C). At this concentration, methotrexate selectively inhibits folate binding to the reduced folate carrier (RFC) but does not affect FRα-related binding. Patient fibroblasts showed almost complete loss of methotrexate-independent folate binding (shown in fibroblasts of patients 1 and 3). Retroviral introduction of WT FRα or FRβ into patient fibroblasts (shown only for patient 1) restored and overcompensated methotrexate-independent folate binding. Note that FRβ is not naturally expressed in human fibroblasts and that neutral pH assay conditions exclude PCFT-related binding.

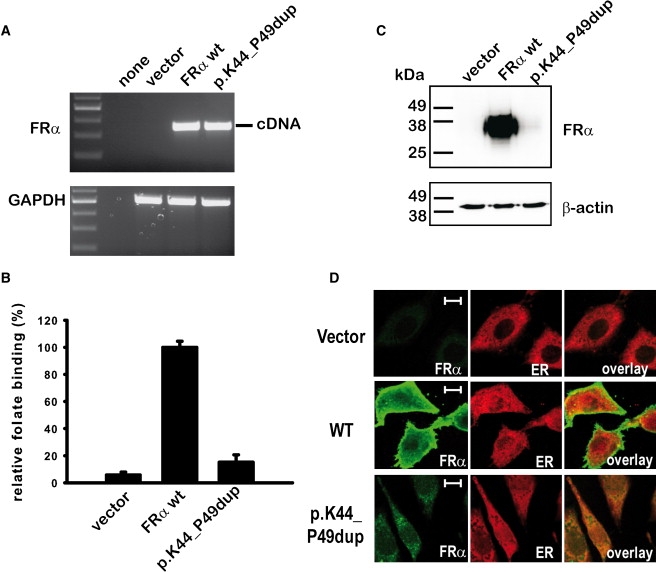

Duplication p.K44_P49dup in the FOLR1 gene leads to an almost complete loss of FRα function. We disclosed the molecular mechanism of reduced folate binding by heterologous expression of WT and p.K44_P49dup FRα in CHO cells (Figures 2A–2D). Although WT and mutant transcripts were similar in intensity, transfection of WT FRα resulted in a 20-fold increase of folate binding but p.K44_P49dup FRα in only a 3-fold increase. Immunoblot analysis revealed that expression of mutant FRα was severely reduced in comparison to WT FRα (Figure 2C). In addition, most of mutant FRα was not localized at the plasma membrane but mistargeted to intracellular compartments when investigated by immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Mutant FRα Containing the KEKPGP Duplication is Instable and Mistargeted

Heterologous stable protein expression of the duplication mutant p.K44_P49dup in CHO-K1 cells demonstrated only a minor increase in folate binding and small amounts of protein expression for the duplication mutant when compared to WT FRα, albeit both transcripts were similar in intensity (A–C). In confocal immunofluorescence microscopy, mutant protein with the duplication p.K44_P49dup was not detected at the cell membrane but mistargeted to intracellular compartments that partially colocalize with the ER marker calreticulin (D). Hence, this mutation is likely to cause major misfolding and subsequent premature degradation of the mutant protein. The length of the displayed white bar corresponds to 20 μm.

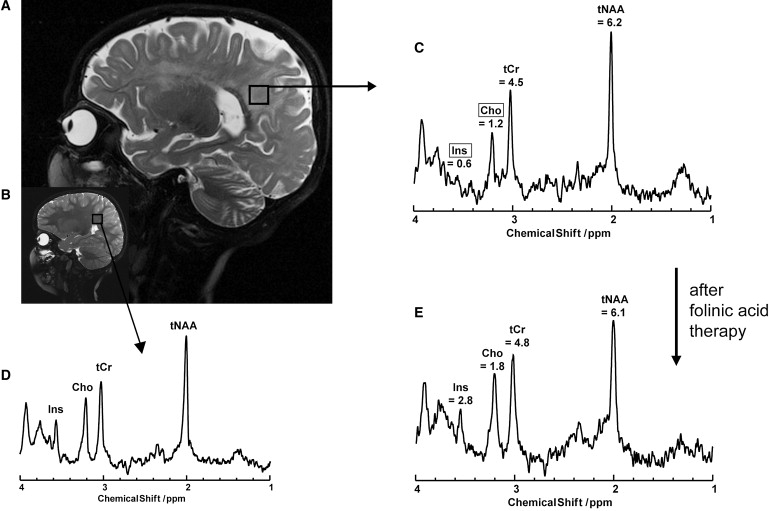

In case of patients 1 and 3, therapy with folinic acid, a 5-formyl derivative of tetrahydrofolate, was delayed by several years after the onset of the first clinical symptoms, at a time when both already had serious motor dysfunction, developmental regression, and epileptic seizures. Brain MRI showed a severely disturbed myelination affecting the periventricular and the subcortical white matter when compared to age-matched controls (Figures 3A–3C). In contrast, patient 2, the younger sister of patient 1, was treated with folinic acid when the first signs of movement disturbances appeared. She demonstrated similar but milder MR abnormalities. In all three patients, analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) disclosed very low MTHF concentrations but gave normal concentrations for total protein, glucose, amino acids, neurotransmitters, and myo-inositol. MTHF, cobalamin, and amino acid concentrations in plasma and MTHF concentration in erythrocytes showed no abnormalities (for details, see Measurements of Cerebrospinal Fluid Metabolites). In vivo proton MRS revealed abnormal concentrations of brain metabolites and, most strikingly, reduced choline and inositol peaks in the parieto-occipital white matter (Figure 3D). In the gray matter, choline and myo-inositol content were within the lower normal range, and the N-acetylaspartate signal was slightly decreased (Figure S1, available online). Supplementation with folinic acid led to clinical improvement in patients 1 and 3 but resulted in immediate complete recovery in patient 2. After 6 months of treatment, the white-matter choline and inositol signals were normalized (Figure 3E) and the first signs of remyelination were visible on brain MRI.

Figure 3.

Brain Imaging in Patients with Cerebral Folate Transport Deficiency

Sagittal T2-weighted MRI of patient 1 at the age of 4 years (A) reveals severely impaired myelination of the white matter and brain atrophy when compared to an age-matched control (B). Brain metabolites were determined by in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS); here is shown the spectrum for a volume of interest (black square in A) in the parieto-occipital white matter. Patient 1 shows strongly decreased signals for choline and myo-inositol in the parieto-occipital white matter (C) in comparison to an age-mached control (D). Six months after the beginning of folinic acid therapy choline and myo-inositol signals are normalized (E). Abbreviations correspond to the following information: Ins, myo-inositol; Cho, choline and other trimethylamine metabolites; tCr, creatine and phosphocreatine; tNAA, N-acetylaspartate and N-acetylaspartylglutamate. Absolute metabolite concentrations are displayed in (C) and (E) and given in mM. Cho and Ins are framed, indicating that both concentrations were below the normal range. Normal values in the parieto-occipital white matter for children at the age of 2–5 years are the following (given in mM): tNAA = 7.2 ± 0.7; tCr = 5.0 ± 0.4; Cho = 1.9 ± 0.2; Ins 3.7 ± 0.6.

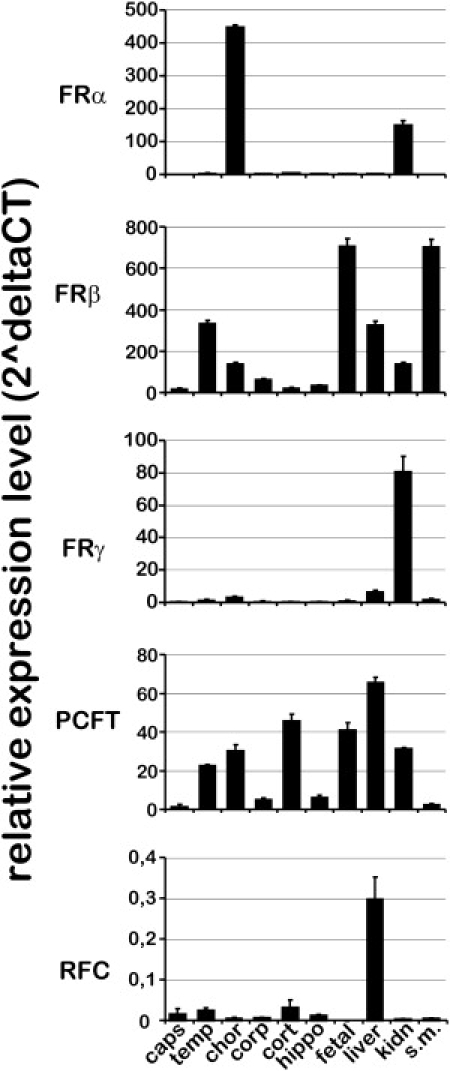

To assess the relative contribution of different folate transporters in the human brain and major organs, we compared the tissue-specific mRNA expression of FRα, FRβ, FRγ (MIM ∗602469), PCFT, and RFC (Figure 4). In the choroid plexus, FRα is highly expressed and highest among all folate transporters. In contrast, FRβ and PCFT expressions are lower in the choroid plexus but significantly higher in other brain regions in comparison to FRα expression. No significant FRγ or RFC expression is detected in the choroid plexus. Thus, we conclude that FRα is the major human folate transporter across the blood-CSF barrier and is most crucial for cerebral folate supply. Interestingly, FRβ expression is particularly high in the human fetal brain and seems to be the predominant folate transporter during prenatal brain development.

Figure 4.

Tissue-Specific mRNA Expression of Known Folate Transporters

Equal amounts of human cDNAs (from BioChain) were used for comparison of the tissue-specific expression of FRα, FRβ, FRγ, RFC, and PCFT by real-time PCR. The mRNA values were calculated as n-fold expression relative to the expression of FRα of capsula interna with the use of the formula 2̂ΔCT.37 The house keeping gene GAPDH was used as an internal reference for comparison of the expression of different folate transporters for one specific tissue. The abbreviations used indicate the following human brain regions: caps, capsula interna; temp, temporal lobe; chor, choroid plexus; corp, corpus callosum; cort, cerebral cortex; hippo, hippocampus; fetal, fetal brain. In addition, mRNA expression for the following human tissues were determined: liver, kidney (kidn), and skeletal muscle (s.m.). FRα expression is highest in the choroid plexus and significant in kidney. In contrast, FRβ is detectable in various human brain tissues but highly expressed in the fetal brain and smooth muscles. FRγ expression is low in the human brain, and the function of FRγ is presently unclear. The PCFT is ubiquitously expressed in the human brain and in other tissues and is thought to function in concert with FRα and FRβ. The RFC is relatively low expressed in human brain tissues but detectable in the highest amount in liver tissue. The heights of the solid bars correspond to the mean values and the slim error bars to the standard deviations.

Discussion

The expression of different folate-transporting proteins is tissue specific and developmentally regulated. Our results are consistent with previous investigations that found the largest amounts of human FRα in the choroid plexus, substantial amounts in the lung, thyroid, and kidney, but no FRα expression in the intestine, heart, pancreas, thymus, cerebrum, cerebellum, spinal cord, spleen, liver, or muscle.10 Recent studies on folate uptake by rat choroid plexus epithelial cells suggest that FRα-mediated endocytosis may function in tandem with PCFT-mediated export.11,25 Thus, folates (MTHF) might be endocytosed at the basolateral plasma side of the choroid plexus, taken over by the PCFT in acidified endosomes, and finally exocytosed at the apical CSF side of the choroid plexus. Other models suggesting that the RFC functions in tandem with FRα are not supported by our results. However, mRNA expression is not strictly correlated with protein expression; hence, our results might not reflect the exact amount of expressed folate transporters. Furthermore, transport capacity and kinetics of different folate transporters vary significantly and depend on the extracellular folate concentration. Lastly, the metabolic and subcellular route of internalized folates is determined by the type of folate-transporting proteins involved and might result in transcytosis of monoglutamyl folate or subcellular accumulation of polyglutamyl folate metabolites that cannot cross cell membranes.26

In generalized folate deficiency caused by hereditary folate malabsorption (MIM #229050)17 or severe dietary folate deficiency, hematological and neurological symptoms develop within the first months of life and may lead to death in infancy when untreated. In contrast, our patients developed symptoms beyond the second year of life, suggesting that alternative, FRα-independent routes of cerebral folate delivery must exist during fetal brain development and in the first two years of life. One plausible hypothesis relates to the high expression of FRβ in the fetal brain, which may initially compensate for the loss of FRα function. It is intriguing that we found an age-dependent drop in FRβ expression in leukocytes when comparing mRNA transcripts from different individuals 2 years of age and older (Figure S2). We could also show that FRβ is upregulated in the human fetal brain, but we were unable to acquire adequate human material to demonstrate the potential postnatal downregulation of FRβ expression in the choroid plexus. The high homology (70% amino acid identity) between FRα and FRβ suggests that both function in tandem with PCFT and that the high postnatal FRβ expression results in the delayed onset of symptoms in patients with FRα defects. In addition, our results suggest that FRβ might be important for folate transport within the brain. In the corresponding mouse models, folr1−/− embryos show severe morphogenetic abnormalities and die in utero. In contrast, folr2 nullizygous embryos develop normally, have no inherent structural defects or pathologies, and are able to reproduce successfully.27 Thus, the biological roles of the murine and human folate receptors seem to differ from each other.

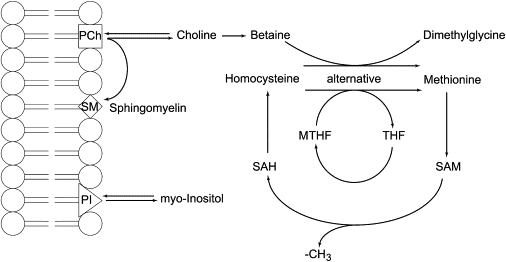

In this inherited disease of cerebral folate transport deficiency, the deficit of glial choline and myo-inositol detected by in vivo MR spectroscopy prior to folinic acid therapy represents a pathognomonic metabolic pattern. The deficit of choline and inositol is consistent with the disturbed myelination found in our patients. A disturbed synthesis of myelin lipids can experimentally be induced in six-week-old rats by dietary folate deficiency.28 Other inherited disorders of folate metabolism, most commonly methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR [MIM #236250]) deficiency, are also associated with disturbed myelination and clinical symptoms such as severe psychomotor retardation and epilepsy.29 Studies on mthfr−/− mice revealed that folate deficiency results in increased choline consumption via oxidation to betaine to maintain sufficient supply of the methyldonor S-adenosyl-methionine, and choline oxidase activity is maintained in the brain even under conditions of choline deprivation.30 The shortfall of choline leads to a lack of phosphatidylcholine31 and other membrane phospholipids, such as sphingomyelin (Figure 5). Phosphatidylcholine, sphingomyelin, and other methylated phospholipids determine important membrane characteristics and are the major components of myelin (11.2% phosphatidylcholine, 7.9% sphingomyelin32). The lack of methylated membrane phospholipids ultimately results in disturbed myelin formation and stability. It also has a potential influence on other membrane phospholipids, such as phosphatidylinositol, which is a major source of intracellular myo-inositol. Intracellular myo-inositol is derived from recycling in the phosphatidylinositol cycle (Figure 5), synthesized de novo from glucose-6-phosphate, or taken up from extracellular fluid.33 There is experimental evidence for two distinct intracellular myo-inositol pools that show different efflux kinetics and tissue distribution.34,35 One myo-inositol pool, with fast kinetics, is thought to be associated with the gray matter and primarily responds to the changes of plasma osmolyte concentrations, whereas the other pool, with slow kinetics, might be related to the membrane-associated myo-inositol fraction within the white matter. Furthermore, studies with dietary supplementation of myo-inositol showed a 2.5-fold higher increase in myo-inositol signal in gray matter than in white matter of the brain when measured by in vivo MR spectroscopy.36 On the basis of these experimental data, we hypothesize that the disturbed myelin formation in cerebral folate transport deficiency preferentially affects the membrane-associated myo-inositol compartment with slow kinetics and white-matter choline but does not affect gray-matter choline and myo-inositol. Future studies will be necessary to prove this hypothesis and further elucidate the interaction of different brain metabolites in myelin formation.

Figure 5.

Brain-Specific Biochemical Pathways Connecting Folate and Choline Metabolism

During the conversion of S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) to S-adenosyl-homocysteine (SAH), a methyl group (-CH3) is released. This conversion is the key methyl donor for most methylation reactions. SAM is regenerated by the methylation of homocysteine to methionine. This reaction is mediated mainly by the methyl-tetrahydrofolate (MTHF) to tetrahydrofolate (THF) conversion. Alternatively, the conversion of choline to dimethylglycine can deliver the required methyl group to regenerate SAM. In the case of folate deficiency, SAM is regenerated mainly by the choline-oxidation pathway, leading to a secondary choline deficiency. At equilibrium, more than 90% of the cellular choline and myo-inositol are anchored in membranes in the form of phosphatidylcholine (PCh) and phosphatidylinositol (PI). However, choline and inositol can be released from their membrane anchor and supplied to the cytoplasmic compartment. Thus, choline deficiency can result in reduced membrane content of phosphtidylcholine (PCh) and might also influence the amount of other phospholipids, such as phosphatidylinositol (PI). During brain development, in particular during myelin formation, the choline demand for the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine (PCh) and sphingomyelin (SM) is very high, and choline deficiency ultimately results in disturbed myelination that may affect the amount and composition of myelin. Note that only free, non-membrane-bound choline (and other trimethylamine compounds, such as phosphocholine and glycerophosphocholine) and free myo-inositol can be detected by proton MRS (Figures 3C–3E).

The discovery of this brain-specific folate transport defect, which we believe has not been previously reported, gives new insight into the brain-specific function of folate and allows the distinction to its noncerebral functions that are present in systemic folate deficiency.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Data include two figures and one table and can be found with this article online at http://www.cell.com/AJHG.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

NCBI dbSNP, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the determination of anti-folate receptor antibodies by Vincent Ramaekers and the expert advice by Nenad Blau. We thank the pediatricians who, in addition to us, cared for the three patients: namely, Harald Bode, Holger Cario, Jonas Kreth, and Julia Busse. We are grateful to Kathrin Schreiber, Tanja Wilke, Nicole Holstein, Fokje Zijlstra, and Ben Geurtz for their technical assistance and to Sabine Weller for critical review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Blount B.C., Mack M.M., Wehr C.M., MacGregor J.T., Hiatt R.A., Wang G., Wickramasinghe S.N., Everson R.B., Ames B.N. Folate deficiency causes uracil misincorporation into human DNA and chromosome breakage: implications for cancer and neuronal damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:3290–3295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kronenberg G., Harms C., Sobol R.W., Cardozo-Pelaez F., Linhart H., Winter B., Balkaya M., Gertz K., Gay S.B., Cox D. Folate deficiency induces neurodegeneration and brain dysfunction in mice lacking uracil DNA glycosylase. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7219–7230. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0940-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linhart H.G., Troen A., Bell G.W., Cantu E., Chao W.H., Moran E., Steine E., He T., Jaenisch R. Folate deficiency induces genomic uracil misincorporation and hypomethylation but does not increase DNA point mutations. Gastroenterology. 2008;136:227–235. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.016. Published online October 9, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghoshal K., Li X., Datta J., Bai S., Pogribny I., Pogribny M., Huang Y., Young D., Jacob S.T. A folate- and methyl-deficient diet alters the expression of DNA methyltransferases and methyl CpG binding proteins involved in epigenetic gene silencing in livers of F344 rats. J. Nutr. 2006;136:1522–1527. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pogribny I.P., Karpf A.R., James S.R., Melnyk S., Han T., Tryndyak V.P. Epigenetic alterations in the brains of Fisher 344 rats induced by long-term administration of folate/methyl-deficient diet. Brain Res. 2008;1237:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fournier I., Ploye F., Cottet-Emard J.M., Brun J., Claustrat B. Folate deficiency alters melatonin secretion in rats. J. Nutr. 2002;132:2781–2784. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.9.2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinohara Y., Hasegawa H., Ogawa K., Tagoku K., Hashimoto T. Distinct effects of folate and choline deficiency on plasma kinetics of methionine and homocysteine in rats. Metabolism. 2006;55:899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLean E., de Benoist B., Allen L.H. Review of the magnitude of folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies worldwide. Food Nutr. Bull. 2008;29:S38–S51. doi: 10.1177/15648265080292S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matherly L.H., Goldman D.I. Membrane transport of folates. Vitam. Horm. 2003;66:403–456. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(03)01012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weitman S.D., Lark R.H., Coney L.R., Fort D.W., Frasca V., Zurawski V.R., Kamen B.A. Distribution of the folate receptor GP38 in normal and malignant cell lines and tissues. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3396–3401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao R., Min S.H., Wang Y., Campanella E., Low P.S., Goldman I.D. A role for the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT-SLC46A1) in folate receptor-mediated endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:4267–4274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807665200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyette P., Sumner J.S., Milos R., Duncan A.M., Rosenblatt D.S., Matthews R.G., Rozen R. Human methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase: isolation of cDNA mapping and mutation identification. Nat. Genet. 1994;7:551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenblatt D., Fenton W.A. Inherited disorders of folate and cobalamin transport and metabolism. In: Scriver C.R., Beaudet A.L., Sly W.S., Valle D., editors. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. pp. 3897–3933. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leclerc D., Wilson A., Dumas R., Gafuik C., Song D., Watkins D., Heng H.H., Rommens J.M., Scherer S.W., Rosenblatt D.S., Gravel R.A. Cloning and mapping of a cDNA for methionine synthase reductase, a flavoprotein defective in patients with homocystinuria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:3059–3064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leclerc D., Campeau E., Goyette P., Adjalla C.E., Christensen B., Ross M., Eydoux P., Rosenblatt D.S., Rozen R., Gravel R.A. Human methionine synthase: cDNA cloning and identification of mutations in patients of the cblG complementation group of folate/cobalamin disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996;5:1867–1874. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.12.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilton J.F., Christensen K.E., Watkins D., Raby B.A., Renaud Y., de la Luna S., Estivill X., MacKenzie R.E., Hudson T.J., Rosenblatt D.S. The molecular basis of glutamate formiminotransferase deficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2003;22:67–73. doi: 10.1002/humu.10236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu A., Jansen M., Sakaris A., Min S.H., Chattopadhyay S., Tsai E., Sandoval C., Zhao R., Akabas M.H., Goldman I.D. Identification of an intestinal folate transporter and the molecular basis for hereditary folate malabsorption. Cell. 2006;127:917–928. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramaekers V.T., Rothenberg S.P., Sequeira J.M., Opladen T., Blau N., Quadros E.V., Selhub J. Autoantibodies to folate receptors in the cerebral folate deficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1985–1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verbeek M.M., Blom A.M., Wevers R.A., Lagerwerf A.J., van de Geer J., Willemsen M.A. Technical and biochemical factors affecting cerebrospinal fluid 5-MTHF, biopterin and neopterin concentrations. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008;95:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jansen G., Muskiet F.A., Schierbeek H., Berger R., van der Slik W. Capillary gas chromatographic profiling of urinary, plasma and erythrocyte sugars and polyols as their trimethylsilyl derivatives, preceded by a simple and rapid prepurification method. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1986;157:277–293. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(86)90303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ling M.M., Robinson B.H. Approaches to DNA mutagenesis: an overview. Anal. Biochem. 1997;254:157–178. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frahm J., Bruhn H., Gyngell M.L., Merboldt K.D., Hanicke W., Sauter R. Localized high-resolution proton NMR spectroscopy using stimulated echoes: initial applications to human brain in vivo. Magn. Reson. Med. 1989;9:79–93. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910090110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Provencher S.W. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn. Reson. Med. 1993;30:672–679. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frahm J., Hanefeld F. Localized proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of cerebral metabolites. Neuropediatrics. 1996;27:64–69. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wollack J.B., Makori B., Ahlawat S., Koneru R., Picinich S.C., Smith A., Goldman I.D., Qiu A., Cole P.D., Glod J., Kamen B. Characterization of folate uptake by choroid plexus epithelial cells in a rat primary culture model. J. Neurochem. 2008;104:1494–1503. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowler B. Genetic defects of folate and cobalamin metabolism. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1998;157(Suppl 2):S60–S66. doi: 10.1007/pl00014306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piedrahita J.A., Oetama B., Bennett G.D., van Waes J., Kamen B.A., Richardson J., Lacey S.W., Anderson R.G., Finnell R.H. Mice lacking the folic acid-binding protein Folbp1 are defective in early embryonic development. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:228–232. doi: 10.1038/13861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirono H., Wada Y. Effects of dietary folate deficiency on developmental increase of myelin lipids in rat brain. J. Nutr. 1978;108:766–772. doi: 10.1093/jn/108.5.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beckman D.R., Hoganson G., Berlow S., Gilbert E.F. Pathological findings in 5,10-methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. Birth Defects Orig. Artic. Ser. 1987;23:47–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Z., Agellon L.B., Vance D.E. Choline redistribution during adaptation to choline deprivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:10283–10289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwahn B.C., Chen Z., Laryea M.D., Wendel U., Lussier-Cacan S., Genest J., Mar M.H., Zeisel S.H., Castro C., Garrow T., Rozen R. Homocysteine-betaine interactions in a murine model of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. FASEB J. 2003;17:512–514. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0456fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deber C.M., Reynolds S.J. Central nervous system myelin: structure, function, and pathology. Clin. Biochem. 1991;24:113–134. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(91)90421-A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bersudsky Y., Shaldubina A., Agam G., Berry G.T., Belmaker R.H. Homozygote inositol transporter knockout mice show a lithium-like phenotype. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:453–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bersudsky Y., Kaplan Z., Shapiro Y., Agam G., Kofman O., Belmaker R.H. Behavioral evidence for the existence of two pools of cellular inositol. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1994;4:463–467. doi: 10.1016/0924-977x(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolfson M., Bersudsky Y., Hertz E., Berkin V., Zinger E., Hertz L. A model of inositol compartmentation in astrocytes based upon efflux kinetics and slow inositol depletion after uptake inhibition. Neurochem. Res. 2000;25:977–982. doi: 10.1023/a:1007556509371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore C.M., Breeze J.L., Kukes T.J., Rose S.L., Dager S.R., Cohen B.M., Renshaw P.F. Effects of myo-inositol ingestion on human brain myo-inositol levels: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging study. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;45:1197–1202. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubista M., Andrade J.M., Bengtsson M., Forootan A., Jonak J., Lind K., Sindelka R., Sjoback R., Sjogreen B., Strombom L. The real-time polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Aspects Med. 2006;27:95–125. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.