Abstract

This study evaluated whether there were increasing admissions for illicit drug abuse treatment among older persons from 1992 to 2005 in the United States and describes the characteristics, number, and type of substances most commonly abused in this population over this 14-year period. Analyses used public data files from the Treatment Episode Data Set, which tracks federally and state funded substance abuse treatment admissions. From 1992 to 2005, admissions for illicit drug abuse increased significantly; in 2005, 61% of admissions age 50 to 54 years old and 45% of admissions age 55 years and older reported some type of illicit drug abuse, most commonly heroin or cocaine abuse. Criminal justice referrals for drug abuse admissions have increased over time and daily substance use remains high. Efforts to determine best practices for prevention, identification, and treatment of illicit drug abuse in older persons are indicated.

Keywords: Substance abuse, age, treatment admissions, trends, geriatric

Substance abuse among persons age 60 years and older is considered an “invisible epidemic” by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Blow, 1998). Although alcohol abuse in this population has received attention and research interest, there is growing concern about illicit drug use among older persons, as the currently aging baby boomer cohort is both larger in number and has higher rates of illicit drug use than previous older cohorts. Based on data from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA), it was estimated the need for illicit drug abuse treatment for persons age 50 years and older would increase more than 5-fold between 1995 and 2020 (Gfroerer and Epstein, 1999). A more recent study based upon NHSDA data estimated that there would be 4.4 million persons age 50 years and older in need of substance abuse treatment in 2020, but these analyses did not differentiate between alcohol and nonalcohol drug abuse treatment (Gfroerer et al., 2003).

Defining “older” among illicit drug users is challenging. Certainly, 50 years old is not a chronologically “old” age, but it may be reasonable to consider this age old because people with a drug dependence diagnosis die on average 22.5 years earlier than those without the diagnosis (Neumark et al., 2000), and studies have shown that older drug dependent patients have higher rates of medical morbidity than younger drug dependent patients (De Alba et al., 2004; Firoz and Carlson, 2004; Lofwall et al., 2005). Older aged methadone maintenance patients also have more bodily pain, worse general health, and poorer physical and social functioning compared with age-and sex-matched populations norms (Lofwall et al., 2005), suggesting that the health status of a 50-year-old patient with a substance use disorder may be more similar to that of an individual in their 60s without such a disorder. This acceleration of medical morbidity in patients with substance use disorders may make older drug abusers a population with unique treatment needs.

Given the predictions of increased illicit drug abuse treatment need among older persons, the purpose of this study was to determine whether there is current evidence of increasing illicit drug abuse treatment admissions over time (1992–2005) among persons age 50 years and older. In addition, the number of substances, the specific types of substances abused, and the characteristics of older aged admissions by substance abuse type (i.e., alcohol abuse only, drug abuse only, or combined alcohol and drug abuse) were characterized. The same variables were evaluated for all age admissions so that it could be determined whether changes over time were specific to older aged admissions, or consistent with a broader effect that was not age specific.

METHODS

Treatment Episode Dataset

The treatment episode dataset (TEDS) system is collected and managed by the United States Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration Office of Applied Studies and the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) (US DHHS, 2007). It provides information on the demographic and substance use characteristics of admissions for people of all ages admitted to facilities that receive state or federal alcohol or drug treatment funding. TEDS does not include data from the Bureau of Prisons, Department of Defense, the Indian Health Service, or the Department of Veterans Administration. TEDS counts admissions, not individuals, such that if the same person was admitted to treatment multiple times in a year, each admission would be counted separately. Only one substance per admission can be reported as the primary substance of abuse, which is the substance causing problems that leads to the current treatment episode. Up to 2 additional current substances of abuse can be recorded for each admission so that polysubstance abuse can be tracked. There is no formal definition of abuse in TEDS (i.e., “abuse” in TEDS is not a DSM-IV diagnosis). The term abuse is used here as it is used in TEDS – that is, as an indicator of a problem in that class of substance that resulted in a treatment admission.

The TEDS tracks 18 substances/classes of substances: alcohol, cocaine (including crack), marijuana (including hashish), heroin, methadone, other opiates and synthetics (prescription opioids), PCP, hallucinogens, methamphetamine, other amphetamines, other stimulants, benzodiazepines, other tranquilizers, barbiturates, other sedatives or hypnotics, inhalants, over-the-counter medications, and other drugs (nicotine is not included). Data are available for 2 older age groups, those aged 50 to 54 and those age 55 years and older. This study was exempted from IRB approval by the Office of Research Integrity at the University of Kentucky.

Data Analyses

Four sets of analyses were completed for each older age group and for all ages for the years 1992–2005. The first 3 analyses included the proportion of admissions each year reporting: (1) 1, 2, or 3 substances of abuse, (2) alcohol abuse only, other drug (nonalcohol) abuse only, or both alcohol and drug abuse, and (3) primary abuse of each of the 18 classes of substances. Missing data (less than 3% per year within each age group for these analyses) were excluded from analyses.

The fourth set of analyses characterized alcohol abuse only, drug abuse only, and alcohol and drug abuse admissions among older age groups (age 50–54 and 55 years and older) and all age groups (99.6% are 12 years and older and this includes the older age groups) in 1992 and 2005. Characteristics evaluated included the proportion male, black, white, other race, having at least 12 years of education, unemployed, using primary substance of abuse daily, referred from criminal justice, self-referred, and referred from other source. Missing data were also excluded from these analyses. Less than 9% of data were missing within each age group in 1992 and 2005 for these variables, with the exception of employment (12% missing in 1992 for both older age groups) and frequency of primary abused substance (11% to 15% was missing for both older age groups and all ages in 1992).

Frequency/cross-tabulations and chi square statistics were generated using TEDS on-line data analysis system and TEDS concatenated 1992–2005 files (ICPSR 2184, 2185, 2186, 2187, 2651, 2802, 3024, 3314, 3672, 3884, 4022, 4257, 4431, 4626) that are available at http://webapp.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/SAMHDA/DAS3/0056.xml. The methods used to create this concatenated dataset are available through this website. Additional chi square analyses using SPSS version 13.0 were completed comparing 1992 to 2005 data to verify that there were significant increases or decreases between these 2 years. The number of admissions within each age group increased each year such that increases and decreases in percentages over time were not due to shrinking denominators or sample sizes. Given that the sample size was very large and multiple comparisons were made, chi square statistics were considered significant at the 0.0001 level to minimize the chance for type I errors and to minimize the reporting of trivial effects.

RESULTS

There were 1.55 million admissions in 1992 and 1.85 million in 2005 for all ages. In 1992, 3.1% (47,361) of admissions were of age 50 to 54 years old and 3.5% (55,344) were of age 55 years and older. In 2005, older aged admissions accounted for an increasing proportion of all TEDS admissions; 6.0% (108,453) were aged between 50 and 54 years old and 4.2% (75,899) were 55 years and older.

Number of Substances Abused

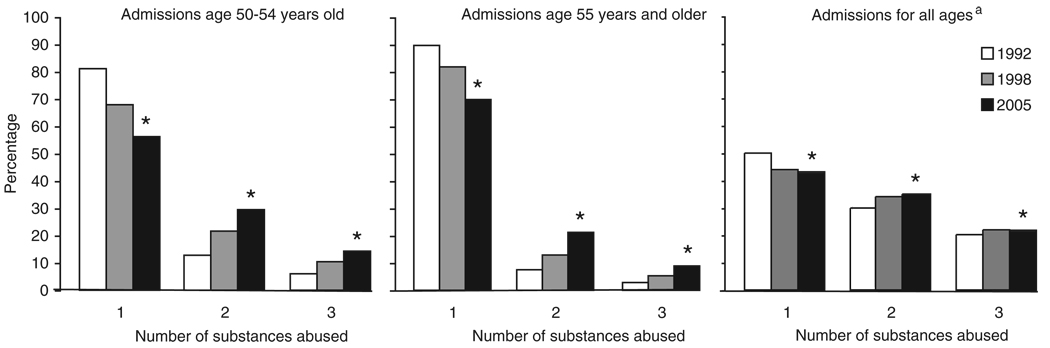

Figure 1 shows the percentage of admissions reporting current abuse of 1, 2, or 3 substances in 1992, 1998, and 2005 within each older age group (left and middle panel) and for all ages (right panel). These years were selected to show the steady and significant changes over time for the older age groups. For both older age groups, there was an increase in the percentage of admissions reporting polysubstance abuse (2 and 3 substances of abuse at the time of admission) and a corresponding decrease in the percentage of admissions reporting only a single substance of abuse from 1992 to 2005. Approximately 44% of admissions aged between 50 and 54 years old and 30% of admissions age 55 years and older reported polysubstance abuse in 2005 compared with 19% and 10%, respectively, in 1992. Although there also was an increase in polysubstance abuse among admissions of all ages, these increases were less dramatic compared with the older age groups.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of older and all aged admissions reporting current abuse of 1, 2, or 3 substances in 1992, 1998, and 2005. *Indicates significant increase or decrease compared with 1992 (p < 0.0001). aGreater than 99.6% of all age admissions are 12 years and older.

Alcohol Abuse, Drug Abuse, and Combined Alcohol and Drug Abuse

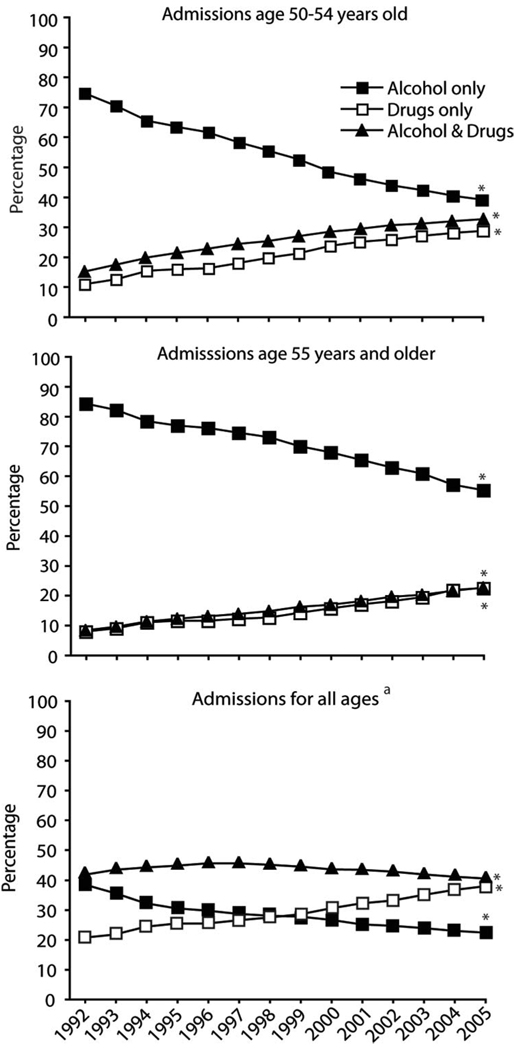

In Figure 2, the percentage of admissions from 1992 to 2005 reporting alcohol abuse only, drug abuse only, or alcohol and drug abuse among those aged between 50 and 54 years old (upper panel), 55 years and older (middle panel), and all ages (lower panel) are presented. In 1992, approximately 75% to 85% of admissions for both older age groups were for alcohol abuse only. Subsequently, there was a steady and significant decline in alcohol abuse only admissions for both older groups over time, such that in 2005, 61% of admissions aged between 50 and 54 years old and 45% of admissions age 55 years and older involved some form of drug abuse (e.g., drug abuse only or both alcohol and drug abuse). For all ages (lower panel), alcohol abuse only admissions decreased and drug abuse only admissions increased, which is similar to the trend over time for the older age groups. However, in contrast to the older age groups, admissions for combined alcohol and drug abuse remained fairly steady over time (41.4% in 1992 and 40.2% in 2005) and accounted for the majority of all aged admissions.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of older and all aged admissions reporting current alcohol abuse only, drug abuse only, or alcohol and drug abuse from 1992–2005. *Indicates significant increase or decrease compared with 1992 (p < 0.0001). aGreater than 99.6% of all age admissions are 12 years and older.

Primary Substance of Abuse

Table 1 shows the percentage of admissions within each older age group and among all ages by the primary substance of abuse (substance that is reported as the reason for admission) from 1992 to 2005. Alcohol, heroin, cocaine, prescription opioids, marijuana, and methamphetamine were the 6 most common primary substances of abuse for these 3 age categories. Alcohol abuse was the most common reason for admission in every year from 1992 to 2005 for all ages and both older age groups, although it declined significantly (>20%) over this period of time for these 3 age categories. The percentage of admissions for alcohol abuse was highest among those age 55 years and older, whereas the percentage of admissions for illicit drugs was consistently lowest in this age group.

TABLE 1.

Percentage of Admissions Age 50 to 54 Years Old, 55 Years and Older, and All Ages by Primary Substance Abused From 1992 to 2005a

| Primary Substance (%) | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | ||||||||||||||

| 50–54 years old | 84.2 | 81.5 | 77.3 | 76.2 | 75.3 | 72.7 | 70.2 | 67.9 | 64.7 | 63.0 | 61.0 | 59.2 | 58.2 | 57.2 |

| 55 years old and older | 89.4 | 87.9 | 85.3 | 84.3 | 83.9 | 82.7 | 81.9 | 79.7 | 77.9 | 76.0 | 74.5 | 72.7 | 70.9 | 69.0 |

| All ages | 61.0 | 58.5 | 54.4 | 52.4 | 52.0 | 50.7 | 49.8 | 49.1 | 47.4 | 45.5 | 44.3 | 42.8 | 41.4 | 40.4 |

| Heroin | ||||||||||||||

| 50 to 54 years old | 9.1 | 10.9 | 13.1 | 13.8 | 13.7 | 15.7 | 16.4 | 17.8 | 19.6 | 20.0 | 20.3 | 20.2 | 19.3 | 18.7b |

| 55 years old and older | 5.9 | 7.2 | 8.8 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 10.9 | 11.7 | 12.2 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 13.7 | 14.1 |

| All ages | 11.2 | 12.4 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 14.9 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 15.0 | 14.5 | 14.2c |

| Cocaine | ||||||||||||||

| 50–54 years old | 4.0 | 4.6 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 6.6 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 9.9 | 11.3 | 12.3 | 13.2 |

| 55 years old and older | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 8.5 |

| All ages | 17.9 | 17.9 | 18.3 | 17.0 | 16.5 | 15.1 | 15.3 | 14.4 | 13.9 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 14.0 | 14.2 | 14.3 |

| Prescription opioids | ||||||||||||||

| 50–54 years old | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| 55 years old and older | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.8 |

| All ages | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.6 |

| Marijuana | ||||||||||||||

| 50–54 years old | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.0 |

| 55 years old and older | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| All ages | 6.1 | 7.1 | 8.8 | 10.5 | 12.0 | 12.6 | 13.2 | 13.8 | 14.6 | 15.4 | 15.7 | 16.0 | 16.4 | 16.3 |

| Methamphetamine | ||||||||||||||

| 50–54 years old | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| 55 years old and older | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| All ages | 1.0 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 8.5 |

Prescription opioids exclude methadone. Greater than 99.6% of all age category is 12 years and older. Bolded values indicate significant (p < 0.0001) increase or decrease from 1992 within each age group.

Significant decrease compared to 2002.

Significant decrease compared to 2001.

Admissions for heroin, cocaine, prescription opioids, marijuana, and methamphetamine abuse treatment significantly increased from 1992 to 2005 for both older age groups and for all ages with the exception of admissions for cocaine abuse, which decreased significantly among all aged admissions. The increase in admissions for prescription opioid, marijuana, and methamphetamine abuse has not yet leveled off for all 3 age categories in contrast to admissions for heroin abuse. In the 50 to 54 year old age group, primary heroin abuse was at its nadir in 1995 (9.1%), peaked in 2002 (20.3%), and declined significantly in 2005 (18.7%). For all aged admissions, a similar pattern was evident; primary heroin abuse was at its nadir in 1995 (11.2%), peaked in 2001 (15.9%), and then declined significantly in 2005 (14.2%). Of the remaining 12 classes of abused substances not listed in the table, no class was identified as the primary drug of abuse in any year at a rate higher than 0.8%. Primary methadone abuse was less than 0.3% each year for both older age groups and among all aged admissions.

Characteristics of Alcohol Only, Drug Only, and Combined Alcohol and Drug Abuse Admissions

Table 2 shows the characteristics of substance abuse admission types (i.e., alcohol abuse only, drug abuse only, and combined alcohol and drug abuse) within each older age group and all ages in 1992 and 2005. For all age groups in both years, the majority of admissions have remained male (>60%). There has been either no significant change or a small decline (less than 5%) in the percentage of male admissions across all admission types and age groups, with the exception of alcohol (5.5% decrease) and drug abuse only (7% decrease) admissions among 50 to 54 year olds.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Alcohol Only, Drug Only, and Alcohol and Drug Admissions by Age (1992 and 2005)a

| Alcohol Only | Drugs Only | Alcohol and Drugs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) |

(%) |

(%) |

|||||

| Characteristic | Age (yrs) | 1992 | 2005 | 1992 | 2005 | 1992 | 2005 |

| Male | 50–54 old | 83.5 | 78.0 | 76.9 | 69.6 | 82.4 | 77.9 |

| 55 and older | 83.2 | 79.7 | 75.4 | 72.5 | 80.1 | 81.0 | |

| All ages | 78.8 | 74.9 | 62.8 | 61.5 | 71.5 | 70.7 | |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 50–54 | 70.6 | 75.4 | 37.8 | 46.8 | 47.9 | 48.5 |

| 55 and older | 74.8 | 75.4 | 40.7 | 45.8 | 53.7 | 46.7 | |

| All ages | 74.7 | 75.6 | 46.7 | 61.0 | 58.4 | 59.2 | |

| Black | 50–54 | 17.2 | 14.7 | 38.8 | 40.2 | 39.5 | 41.5 |

| 55 and older | 14.9 | 14.1 | 33.3 | 39.7 | 34.2 | 40.7 | |

| All ages | 14.7 | 12.6 | 36.5 | 24.1 | 32.3 | 27.3 | |

| Other | 50–54 | 12.2 | 9.9 | 23.4 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 10.0 |

| 55 and older | 10.3 | 10.5 | 26.0 | 14.5 | 12.1 | 12.6 | |

| All ages | 10.6 | 11.8 | 16.8 | 14.9 | 9.3 | 13.5 | |

| Education | |||||||

| ≥12 yrs | 50–54 | 60.6 | 78.5 | 59.2 | 70.8 | 57.4 | 71.3 |

| 55 and older | 55.9 | 73.8 | 54.0 | 67.1 | 56.3 | 68.5 | |

| All ages | 62.8 | 73.0 | 58.7 | 57.8 | 56.8 | 58.9 | |

| Unemployed | 50–54 | 23.1 | 31.1 | 25.9 | 30.9 | 26.4 | 28.3 |

| 55 and older | 14.8 | 20.7 | 18.2 | 24.4 | 20.5 | 21.4 | |

| All ages | 23.3 | 28.1 | 32.2 | 34.0 | 30.8 | 29.4 | |

| Daily substance use | 50–54 | 50.2 | 46.8 | 75.8 | 56.7 | 58.6 | 48.8 |

| 55 and older | 50.9 | 45.6 | 79.1 | 58.0 | 57.2 | 49.3 | |

| All ages | 34.8 | 33.9 | 58.4 | 46.8 | 41.4 | 38.2 | |

| Referral source | |||||||

| Criminal justice | 50–54 | 31.9 | 29.0 | 12.3 | 21.6 | 18.4 | 24.0 |

| 55 and older | 32.5 | 29.8 | 10.1 | 19.3 | 20.1 | 23.9 | |

| All ages | 42.8 | 41.6 | 22.6 | 32.8 | 29.7 | 37.0 | |

| Self-referred | 50–54 | 34.8 | 34.9 | 65.9 | 50.3 | 40.2 | 38.3 |

| 55 and older | 33.8 | 34.8 | 66.9 | 53.7 | 40.2 | 39.9 | |

| All ages | 29.4 | 28.4 | 50.8 | 38.2 | 34.0 | 30.7 | |

| Other | 50–54 | 33.3 | 36.1 | 21.8 | 28.1 | 41.4 | 37.7 |

| 55 and older | 33.7 | 35.4 | 23.0 | 27.0 | 39.7 | 36.2 | |

| All ages | 27.8 | 30.0 | 26.6 | 29.0 | 36.3 | 32.3 | |

Greater than 99.6% of all age category is 12 years and older. Other referral source includes employer/Employee Assistance Program, school, alcohol/drug abuse care provider, other health care provider, and other community referrals. Bolded values indicate significant (p < 0.0001) increase or decrease from 1992 within each age group and admission type.

Changes over time in race were most dramatic for drug abuse only admissions whereby the percentage white increased in all age categories such that drug abuse admissions were 46% to 47% white in the older age groups and 61% white in the all ages group in 2005. The percentage of drug abuse only admissions that were black in 2005 was 40% among the 2 older age groups and 24% among all ages, representing significant changes for the 55 year and older and all age group. The percentage of drug abuse only admissions that were other races (all minorities) decreased among all 3 age categories such that they accounted for only 13% to 15% of drug admissions in 2005. Alcohol abuse only admissions remained primarily white in 1992 (70%–75%) and 2005 (75%–76%) for all age categories. Changes in the percentage of white, black, and other race alcohol abuse only admissions were small (<5%) between 1992 and 2005 for all 3 age groups. Combined alcohol and drug abuse admissions among the older groups were primarily white (47%–49%) and black (41%–42%) in 2005, which was significantly different from 1992 only for those age 55 years and older. For all aged drug and alcohol admissions, there were small changes (5% or less) in race over time, but the majority remained white (approximately 60%) in 2005.

The percentage of admissions with at least 12 years of education increased by 10% to 28% across each substance abuse admission type for both older age groups such that more than two thirds had at least a high school education in 2005. For all ages, a similar 10% increase occurred for alcohol abuse only admissions; however, for drug abuse only and combined alcohol and drug abuse admissions, the percentage with at least a high school education changed by only 1% to 2%.

The percentage of alcohol or drug abuse only admissions that were unemployed significantly increased (between 2% and 8%) for all 3 age categories, whereas the percentage unemployed remained fairly steady for combined alcohol and drug abuse admissions. For all substance abuse types, the percent unemployed remained lowest among those 55 years and older (21%–24%). The percentage reporting daily substance use decreased among all ages and all substance admissions types and remained highest (57%–58%) within the 2 older groups for the drug abuse only admissions.

The most common referral sources for all 3 age groups were self-referrals and criminal justice referrals. For all 3 age groups, criminal justice referrals increased by more than 9% for drug abuse only admissions and 4% to 7% for combined alcohol and drug abuse admissions but decreased for alcohol abuse only admissions. Self-referrals changed most dramatically among drug abuse only admissions whereby there was a 12% drop for all age groups.

DISCUSSION

This study used the Treatment Episode Dataset to evaluate the characteristics including number and types of substances abused among admissions of persons age 50 and older over the interval 1992–2005. The results show admissions of older persons have grown such that in 2005, approximately 10% of all admissions were age 50 years and older. Although alcohol abuse continues to be the most common reason for substance abuse treatment admission among older persons, alcohol was not as commonly abused in 2005 compared with 1992, and it is no longer typically the sole substance of abuse. There is a growing proportion of older aged admissions reporting polysubstance and illicit drug abuse, particularly cocaine and heroin abuse. Although many of these changes also were present among admissions for all ages (e.g., an increase in polysubstance abuse), this changing profile of abused substances among admissions age 50 years and older has important clinical and public health implications.

Perhaps one of the most important findings based upon these data is that older people abuse illicit drugs. Previous beliefs that older persons aged out of using illicit drugs (Winick, 1962; Snow, 1973) are not supported by these data. There is growing evidence that aging is not always protective against drug use but rather that drug addiction is affected by many different factors (Anglin et al., 1986; Brecht et al., 1987) and is often a chronic, relapsing disorder (Haastrup and Jepsen, 1988; McLellan et al., 2000).

For instance, in a 33-year longitudinal study of 581 opioid addicts, among those who were between 50 and 60 years old, approximately one half continued to use opioids, and relapse among these older patients was not uncommon even after 15 years of abstinence (Hser et al., 2001). In another study, it was found that the mean age of persons reporting intravenous drug use in the past year increased from 21 to 36 years old between 1979 and 2002 (Armstrong, 2007), highlighting a shift in injection drug use to older aged persons. In addition, between 1991 and 2002, there has been a significant increase in past year marijuana use and marijuana use disorders among people age 45 to 64 years old (Compton et al., 2004). Thus, it is clear that use of drugs is not uncommon in older persons; however, it is not clear whether illicit drug use among older persons represents primarily a pattern of continued use through the adult years, a return to use after a period of abstinence, new-onset use, or some combination of all these patterns.

The reasons why there have been increases in illicit drug abuse treatment admissions among older persons are not clear, and the dataset was not created for this purpose. Nonetheless, the data presented demonstrate that the increases in drug abuse only admissions and decreases in alcohol only admissions also are present within all aged admissions, so these longitudinal changes over time may not be entirely specific to the older age groups. There were no changes in the coding or definition of alcohol and drug abuse in the TEDS over this 14-year period, so methodological changes are not likely to account for these findings. There were significant increases in criminal justice referrals for drug abuse only (9% increase) and combined alcohol and drug abuse (3%–5% increase) admissions for both older age groups (Table 2), whereas criminal justice referrals decreased for alcohol abuse only admissions. Thus, it is possible that the increasing involvement of criminal justice system, including drug courts, could explain some of the increases in drug abuse treatment among older aged admissions.

However, it is also possible that the results are due, at least in part, to cohort effects because more baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) have aged into these older age categories over 1992–2005. This generation has higher rates of lifetime illicit drug use, is larger in number than previous older cohorts, and is responsible for the predictions of increased illicit drug abuse treatment need among persons age 50 years and older (Gfroerer and Epstein, 1999) mentioned previously. This cohort effect would explain why the increases are more dramatic among the 50 to 54 year old admissions compared with admissions age 55 years and older, as the entire 50 to 54 age group consists only of baby boomers since 2004. If this is correct, illicit drug abuse admissions aged 55 years and older should continue to increase at least through the year 2019 (when all baby boomers are at least age 55 years old).

It is unlikely that the reasons for the increase in illicit drug abuse admissions among older aged persons are due to improved detection of drug problems among older persons by health care providers or increases in self-referral, as older persons are often not screened for substance use by health care providers (Reid et al. 1998; Spandorfer et al., 1999; Khan et al., 2002; Mallin et al., 2002), are less likely to report problematic substance use than younger persons (Nemes et al., 2004), and decreases (rather than increases) in self-referral occurred over time in this study (Table 2). Thus, older illicit drug users, particularly those that do not come into contact with the criminal justice system, may go undetected without specific targeted interventions to educate the public and physicians that are likely to interact with this population.

Between 1992 and 2005, the 2 most common illicit drugs associated with older adults entering treatment have consistently been heroin and cocaine. These 2 drugs have accounted for an increasing proportion of substance abuse admissions such that in 2005, 1 in 5.3 substance abuse admissions of age 50 to 54 years old were for primary heroin abuse and 1 in 7.6 were for primary cocaine abuse (Table 1). Treatment admissions for prescription opioids (excluding methadone), marijuana, and methamphetamine abuse were less common and together accounted for approximately 5% to 10% of older aged admissions in 2005. However, admissions related to abuse of these substances also increased over time and do not seem to be leveling off. Notably, primary methadone abuse was uncommon (<0.3%), despite concerns of its increasing diversion and abuse over the last several years (Cicero and Inciardi, 2005).

These results show increasing treatment need for illicit drug abuse among older patients presenting for substance abuse treatment. Clinical providers and researchers will need to determine if current substance abuse treatment practices, which are largely not age-specific (Schultz et al., 2003), are effective for older persons with illicit drug use problems, or whether older persons with illicit drug abuse and polysubstance abuse have distinct treatment needs. Recent studies have shown older individuals do as well or better than their younger counterparts in response to substance abuse treatment (Brennan et al., 2003; Lemke and Moos, 2003a; Lemke and Moos, 2003b; Firoz and Carlson, 2004; Satre et al., 2004; Lofwall et al., 2005). This does not exclude, however, the possibility that older persons may benefit from the development of age-specific illicit drug treatment services or respond better to different types of treatment modalities. Research with older alcoholic patients has shown higher rates of treatment retention when treatment occurs in a similarly aged peer group versus a mixed-age group (Kofoed et al., 1987), and higher rates of abstinence from alcohol are achieved when older persons are treated with cognitive behavioral therapy versus psychotherapy focused on either relationships or occupational roles (Rice et al., 1993).

There is evidence that medical morbidity is a distinguishing feature of older versus younger illicit drug users. When compared with younger patients with illicit drug use disorders, older patients have higher rates of hypertension, liver disease, bodily pain, and physical functioning (Firoz and Carlson, 2004; Lofwall et al., 2005), and this is true when they are also compared with older aged population norms (Lofwall et al., 2005). Such studies highlight the association of substance abuse with medical morbidity and mortality (Fingerhood et al., 1993; Moos et al., 1994; Hser et al., 2001).

The percentages of older aged alcohol only, drug only, and combined alcohol and drug abuse admissions reporting daily substance use (45%–58% in 2005; Table 2) has declined since 1992, but the percentages remain high (45%–58%). Thus, many admissions for drug and/or alcohol treatment that are older may be physically dependent. As increasing medical morbidity and older age have been associated with more severe and complicated alcohol withdrawal (Brower et al., 1994; Schuckit et al., 1995; Wojnar et al., 2001), re-evaluation of detoxification protocols and other treatment guidelines to ensure safe and effective treatment practices and outcomes for these older patients is recommended.

The increased medical morbidity of older substance users, combined with the fact that persons with substance abuse often lack primary care providers and have high rates of medical noncompliance (Umbricht-Schneiter et al., 1994), pose a formidable challenge to substance abuse treatment providers and medical providers attempting to find and engage drug using patients in substance abuse treatment. Developing effective linkages between substance abuse and primary care providers will be increasingly important as baby boomers continue to age.

There are limitations to the results presented here. TEDS counts admissions, not persons. Thus, it is unclear whether there is a smaller group of older persons repeatedly utilizing services or a larger group of older persons presenting at substance abuse treatment centers. TEDS also does not include all types of substance abuse treatment programs (e.g., it excludes the Department of Veterans Administration and nonpublicly funded treatment programs) so the profile of substances abused may not reflect all older-aged treatment populations. These are important limitations worthy of further clarification; however, the increased number of illicit drug abuse treatment admissions and changing profile of substances abused among aging persons undoubtedly will challenge sites of addiction care delivery.

In summary, there are increasing numbers and an increasing proportion of older substance abuse treatment admissions for illicit drug abuse among persons age 50 years and older. Furthermore, the aging of the baby boomer population suggests these increases in numbers will not abate in the coming years. Although aging is inevitable, drug use need not be. Given that drug use is associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and costs to both the individual and society, addressing this problem should occur before treatment demand overwhelms providers. Efforts to determine best practices for prevention, identification, and treatment of illicit and polysubstance abuse among older adults are now indicated.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse: T32 DA07209, K02 DA00332, K12 DA14040, and K24 DA023186.

Footnotes

Michelle R. Lofwall had full access to all of the data in the public domain of this study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- Anglin MD, Brecht ML, Woodward JA, Bonett DG. An empirical study of maturing out: Conditional factors. Int J Addict. 1986;21:233–246. doi: 10.3109/10826088609063452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GL. Injection drug users in the United States, 1979–2002: An aging population. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:166–173. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow FC. Treatment Improvement Protocol Series 26. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. Substance abuse amond older adults. SMA02-3688. [Google Scholar]

- Brecht ML, Anglin MD, Woodward JA, Bonett DG. Conditional factors of maturing out: Personal resources and preaddiction sociopathy. Int J Addict. 1987;22:55–69. doi: 10.3109/10826088709027413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PL, Nichol AC, Moos RH. Older and younger patients with substance use disorders: Outpatient mental health service use and functioning over a 12-month interval. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17:42–48. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower KJ, Mudd S, Blow FC, Young JP, Hill EM. Severity and treatment of alcohol withdrawal in elderly versus younger patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:196–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA. Diversion and abuse of methadone prescribed for pain management. JAMA. 2005;293:297–298. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD, Stinson FS. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Alba I, Samet JH, Saitz R. Burden of medical illness in drug- and alcohol-dependent persons without primary care. Am J Addict. 2004;13:33–45. doi: 10.1080/10550490490265307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerhood MI, Jasinski DR, Sullivan JT. Prevalence of hepatitis C in a chemically dependent population. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2025–2030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firoz S, Carlson G. Characteristics and treatment outcome of older methadone-maintenance patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:539–541. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.5.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfroerer J, Penne M, Pemberton M, Folsom R. Substance abuse treatment need among older adults in 2020: The impact of the aging baby-boom cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfroerer JC, Epstein JF. Marijuana initiates and their impact on future drug abuse treatment need. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haastrup S, Jepsen PW. Eleven year follow-up of 300 young opioid addicts. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;77:22–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb05071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, Anglin MD. A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:503–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N, Davis P, Wilkinson TJ, Sellman JD, Graham P. Drinking patterns among older people in the community: Hidden from medical attention? N Z Med J. 2002;115:72–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofoed LL, Tolson RL, Atkinson RM, Toth RL, Turner JA. Treatment compliance of older alcoholics: An elder-specific approach is superior to “mainstreaming.”. J Stud Alcohol. 1987;48:47–51. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke S, Moos RH. Outcomes at 1 and 5 years for older patients with alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003a;24:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke S, Moos RH. Treatment and outcomes of older patients with alcohol use disorders in community residential programs. J Stud Alcohol. 2003b;64:219–226. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofwall MR, Brooner RK, Bigelow GE, Kindbom K, Strain EC. Characteristics of older opioid maintenance patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallin R, Slott K, Tumblin M, Hunter M. Detection of substance use disorders in patients presenting with depression. Subst Abus. 2002;23:115–120. doi: 10.1080/08897070209511481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance and out-comes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Brennan PL, Mertens JR. Mortality rates and predictors of among late-middle-aged and older substance abuse patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemes S, Rao PA, Zeiler C, Munly K, Holtz KD, Hoffman J. Computerized screening of substance abuse problems in a primary care setting: Older vs. younger adults. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:627–642. doi: 10.1081/ada-200032312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark YD, Van Etten ML, Anthony JC. “Drug dependence” and death: Survival analysis of the Baltimore ECA sample from 1981 to 1995. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35:313–327. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MC, Tinetti ME, Brown CJ, Concato J. Physician awareness of alcohol use disorders among older patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:729–734. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C, Longabaugh R, Beattie M, Noel N. Age group differences in response to treatment for problematic alcohol use. Addiction. 1993;88:1369–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Mertens JR, Areán PA, Weisner C. Five-year alcohol and drug treatment outcomes of older adults versus middle-aged and younger adults in a managed care program. Addiction. 2004;99:1286–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Reich T, Hesselbrock VM, Bucholz KK. The histories of withdrawal convulsions and delirium tremens in 1648 alcohol dependent subjects. Addiction. 1995;90:1335–1347. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901013355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz SK, Arndt S, Liesveld J. Locations of facilities with special programs for older substance abuse clients in the US. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:839–843. doi: 10.1002/gps.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow M. Maturing out of narcotic addiction in New York city. Int J Addict. 1973;8:921–938. doi: 10.3109/10826087309033098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spandorfer JM, Israel Y, Turner BJ. Primary care physicians’ views on screening and management of alcohol abuse: Inconsistencies with national guidelines. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:899–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht-Schneiter A, Ginn DH. Providing medical care to methadone clinic patients: Referral vs. on-site care. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:207–210. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Dept of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Treatment Episode Dataset (TEDS), 1992–2005 Concatenated data [computer file] In: ICPSR, editor. Original data prepared by Synectics for Management Decisions, Incorporated. Ann Arbor (MI): Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [producer and distributor]; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Winick C. Maturing out of narcotic addiction. Bull Narc. 1962;14:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wojnar M, Wasilewski D, Zmigrodzka I, Grobel I. Age-related differences in the course of alcohol withdrawal in hospitalized patients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2001;36:577–583. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]